Abstract

Background

Hymenolepis nana is a worldwide intestinal tapeworm parasite that mainly infects children due to a lack of awareness and hygiene. Recently, Praziquantel (PZQ), the drug of choice for treating hymenolepiasis, has shown serious side effects. This study aimed to evaluate histological changes in the ileum of the small intestine caused by hymenolepiasis in an experimental animal model and to assess the efficacy of pumpkin seeds extract (PSE) in eliminating the parasite at different periods compared to medicinal treatment with PZQ drug. In addition, we investigated the morphological alterations in adult dwarf tapeworms after treatment with pumpkin seed extract.

Methods

The histological examination of the small intestine was conducted among four experimental mice groups: normal non-infected control group, infected untreated group, infected and PZQ treated group, and the fourth group was infected and treated with PSE.The morphological investigations were performed on mice from the infected untreated group and those from the infected and treated with pumpkin seed extract group.

Results

Treatment with PSE showed a noticeable preservation of the normal structure of villi and crypts with a normal thickness of the muscle layer. In addition, there was a marked decrease in the number of mononuclear leukocytes and goblet cells. This effect was observed to be duration dependent. The size of the mature segment in the untreated control group ranged from 342.85 to 415.38 μm, and 14.28–26.92 μm in length and width, respectively. The gravid segments revealed a uterus with eggs subjugating the entire area in the segment, with size ranges from 373.33 to 576.92 μm in length and 46.66–76.92 μm in width. The treated group with PSE showed mature segments with size ranged from 261.53 to 346.42 μm in length and 7.69–21.42 μm in width, while the gravid segments ranged from 30.76 to 50 μm and 414.28–492.30 μm, in width and length, respectively. The treatment with pumpkin seed extract tenanted the worm growth through an apparent reduction in the sizes of proglottids, deformity of the lateral margins and gonads, loss of internal structure, and reduction of egg production.

Conclusion

The results of this study clearly reveal the efficacy of pumpkin seeds on H. nana infection, a promising, safe, inexpensive natural alternative anthelmintic therapy, with more superior and significant results in improving and protecting mucosal integrity in comparison to PZQ.

Keywords: Hymenolepis nana, Pumpkin seeds extract, Praziquantel, Small intestine, Ileum, Histological changes, Morphology alterations

Introduction

Hymenolepis nana, or dwarf tapeworm parasite, is frequently reported in children due to lack of hygiene, malnutrition, and awareness [1, 2]. Recent studies considered H. nana as the most common prevalent neglected intestinal cestode in humans and animals [3–10].

In nature, rodents, including mice and rats, are the main final hosts. The life cycle of this miniature tapeworm in humans consists of both direct and indirect life cycles. In the direct life cycle, the parasite does not require an intermediate host to form the infective stage, and the egg is directly infective. Ingested eggs hatch in the intestine and produce oncospheres that invade the intestinal mucosa and become cysticercoids, which come back to the lumen and mature as adult worms. The released eggs can cause external autoinfection or infect other hosts. Some eggs can develop into cysticercoids and cause internal autoinfection. These developmental processes are likely to cause a high burden of worms, allowing infection to persist for years [3, 8, 11]. On the other hand, the intermediate hosts are essential in the indirect life cycle to form the infective cysticercoid. Insects such as flour beetles and fleas serve as intermediate hosts that ingest the parasite eggs to hatch and release oncospheres, which penetrate the insect gut wall and develop into cysticercoids. After ingestion of the insect by a definitive host, each cysticercoid protrudes a scolex that attaches to the intestinal wall of the host [8, 11].

The treatment protocol for H. nana infection includes Praziquantel (PZQ) and Niclosamide [12]. However, some studies reported mutagenic and carcinogenic potential adverse effects of PZQ administration to treat H. nana infection, instigating researchers to use alternative treatment approaches to decrease side effects and improve therapeutic safety [13]. During the last decades, the therapeutic use of plants and herbs as an alternative natural and safe medicine was extensively studied [14].

Phytochemical profile has shown that pumpkin seeds are a rich natural source of phytosterols, peptides, proteins, minerals, polyunsaturated fatty acids, antioxidant compounds, carotenoids, tocopherols, sterols, p-aminobenzoic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid, polysaccharides, squalene, cucurbitosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, cardiac glycosides, steroids and numerous phenolic compounds. These components are attributed to providing many health benefits [15–19].

Ethnopharmacological studies have shown that pumpkin seeds are used in many countries, mainly in China, Mexico, Egypt, Europe, Central and North America, Hungary, Slovenia, Spain, and various Asian, African, and European countries, to treat a variety of diseases [15, 19]. The seeds have been traditionally used as anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, antidiabetic, antioxidant, antihypertensive, anticarcinogenic, antipyretic, analgesic, wound healer, immunomodulator, dewormer, and to treat complaints of several organs such as stomach, liver, lungs, spleen, prostate, kidney and bladder [15, 18–20].

The active ingredient in pumpkin seeds against tapeworms is cucurbitin, which preserves a special non-proteic amino acid (3-amino-3-carboxypyrrolidine), which is the most effective chemical for paralyzing the worm’s muscles until it detaches from the host’s intestinal mucosa, leading to its expulsion from the digestive tract [21–27]. A recent study investigated the efficacy of different extracts of pumpkin seeds (by ethanol, hot water, or cold water) against Heligmosoides bakeri and found that all these types of extract contain fatty acids, amino acids, and protoberberine alkaloids, including berberine and palmatine [28]. It was reported that these protoberberine alkaloids exhibit antileishmaniasis [29], antimalarial effect [30], toxoplasmosis inhibitory [31], and anti-schistosomiasis [32]. A previous study reported that the anthelmintic effect of pumpkin seeds is related to the secondary metabolites, mainly the alkaloids [33]. The therapeutic effect of the combined extract from pumpkin seeds and areca nuts proved to eliminate beef and pork tapeworms [34]. Recently, an in vitro study has shown that pumpkin seeds induced tegumental damage and microsatellite instability to the immature and adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni [35].

In our previous study, compared to PZQ, we evaluated the efficiency of the natural pumpkin seeds extract (PSE) on the burden and length of H. nana adult worm, and on egg production and viability [36]. Our present study aimed to investigate the histological changes in the small intestine ileum of mice experimentally infected with H. nana, after treatment with pumpkin seed extract compared with PZQ at different periods. In addition, we examined the effect of pumpkin seed extract on the morphology of the adult worms at different sampling times during the treatment.

Materials and Methods

The experimental study on animals was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the regulations of King Fahd Medical Research Center, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Experimental Animals

The study was conducted on healthy laboratory-bred Swiss albino female mice of 6-8-weeks, and weighing 25–35 gm. All animals were maintained in well-controlled conditions of ventilation, light, and temperature.

To ensure that the animals were free of any enteroparasites, feces were examined microscopically, as previously described, using wet and iodine smears, formol-ether sedimentation method and modified Kinyoun’s staining [37–39].

Eighty mice were divided into four groups (20 in each group). Group A, normal uninfected control, while each mouse in Groups B, C and D was infected orally using a stomach tube, with approximately 1500 H. nana eggs dispensed in 0.2 ml PBS, as described previously [36]. The infection was confirmed by detection of eggs in stool samples using light microscopic examination.

Fifteen days post-infection (15 dpi), Group B was left untreated, while Group C was treated with an oral dose of PZQ of 25 mg/kg, and Group D with PSE of 500 mg/kg for 13 days [21, 36, 40].

Pumpkin Seed Extract Preparation

As previously described [36], the seeds were mechanically ground, and then 50 g were boiled in 500 ml of distilled water for 45 min and allowed to settle. Several layers of cheesecloth were used to filter the mixture twice, then the filtrate was centrifuged at 750 g for 10 min, filtered, and allowed to evaporate. The solid extract was stored at 4 °C for later use.

Adult Worms Collection and Staining

On different four dpi (16, 18, 21, 22, 26 or 29), five mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and then euthanized by manual cervical dislocation (Group A: dpi 18, 22, 26 and 29; Group B: dpi 18, 22, 26 and 29; Group C: dpi 16, 18 and 21; Group D: dpi 18, 22, 26 and 29 ). The small intestine of each mouse was collected and soaked in normal saline for 30–45 min to release the adult worms, which were then kept for 3 h at 4ºC. Each adult worm was sandwiched between two glass slides, placed in formalin aceto-alcohol fixative for 24 h, then washed with tap water and stained overnight using alum carmine. Slides were washed with tap water repetitively, then placed in 30% and 50% ethanol, respectively. The slides were then incubated in an acidified alcohol solution until the surface of the worms became clear, while the internal organs still retained the stain. The slides were dipped in 70% ethanol, then dehydrated in ascending concentrations (80%, 90%, 95%, 100%, and 100%), for 30 min each, followed 2 times in xylene for 15 min each. Finally, each adult worm was mounted in Canada balsam, covered and examined by light microscopy.

Intestinal Section Preparation and Staining

The ileum was cut out from each collected small intestine, carefully washed from the inside with physiological solution, and then fixed with 10% formalin for sectioning. The fixed samples were washed with tap water and then dehydrated with ascending concentrations of ethanol (50%, 70%, 90% and 100%) [41]. A mixture of xylene and ethyl alcohol was used to clear the samples, then they were passed through a mixture of xylene and paraffin wax at 55 °C. The microtome was adjusted to cut the paraffin wax blocks at 5 μm thickness. Each section was dewaxed and rehydrated in xylene and graded alcohol, respectively, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin for 2–3 min each. Excess of each stain was removed by rinsing in running tap water. Subsequently, each section was dehydrated, cleared, and mounted in DPX. Pathological changes in all stained slides were observed by an independent pathologist using a standard light microscope.

Results

The present study evaluated the histological changes occurring in the small intestine (ileum) of mice experimentally infected with H. nana and assessed the efficacy of PSE on suppressing the infection and maintaining the integrity of the intestinal structure compared to treatment with PZQ. In addition, we examined the effect of PSE on the morphology of the adult worms at different sampling times during the treatment.

On 15 dpi, infection of all mice in the infected groups (B, C and D) was confirmed by microscopic examination of stool. Similarly, the normal control group (A) was confirmed to be not infected.

Histological Observations of Normal Control Group (A)

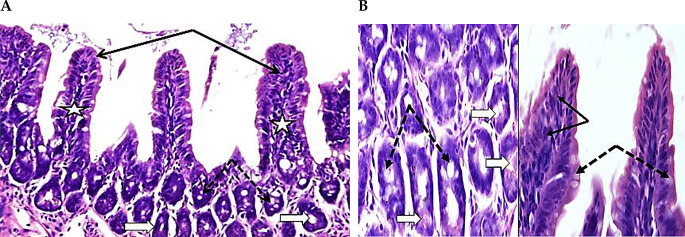

As shown in Figs. 1A and B, the ileum revealed a few mononuclear leukocytes in thin cylindrical villi covered with columnar epithelium with a core of thin connective tissue, and a few goblet cells. Similarly, goblet cells were observed in the intestinal crypts, in addition to a few Paneth’s cells.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of ileum sections from Group A (stained with H&E). A (400X) and B (1000X) show intact villi with columnar covering epithelium (thin black arrows), crypts and villi revealed the presence of a few goblet cells (dotted arrows), villi cores are thin and have few mononuclear leukocytes cells (white stars), crypts with a few Paneth’s cells containing apical granules (thick white arrows), and few goblet cells (dotted arrows)

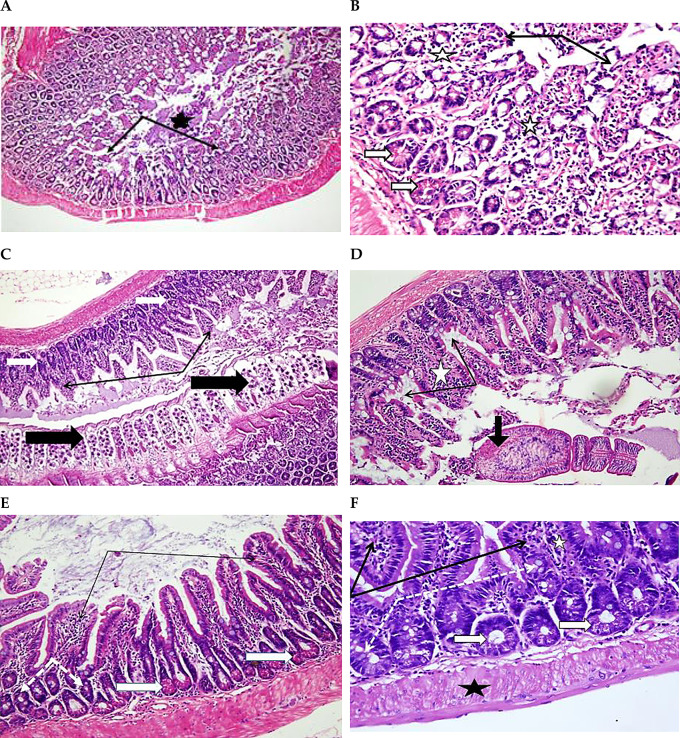

Histological Observations of Infected Group (B)

Figures 2A and B, demonstrate adult dwarf tapeworms within the intestinal lumen with edematous modifications of the villi and marked destruction. Peyer’s patches cells protruded into the lumen through the damaged mucosa. Higher resolutions of the swollen damaged villi showed widening of the connective tissue core, with infiltration of mononuclear leukocyte, presence of Paneth’s cells, and reactive goblets.

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of ileum sections from Group B (stained with H&E). At 18 dpi, A (100X) and B (200X), show part of H. nana worm (thick black arrow) within the lumen. Desquamations and villus surface epithelium loss (thin black arrows). Cells of Peyer’s patches are extruded through damaged mucosa to the lumen (white star in A). Swollen villi with mononuclear leukocyte infiltrate (white stars in B), augmented crypt goblet cells (dotted white arrows in B) and projecting Paneth’s cells with acidophilic granules (white arrows in B). At 22 dpi, C (100X), D (X400), and E (X200), show presence of worms within the lumen (thick black arrows). Damage of villus surface and increase in core mononuclear cells (thin black arrows in C and E). D shows reactive Paneth’s cells (thick white arrows), increased goblet cells (thin black arrows), and swollen core of villi with increased mononuclear leukocyte (white stars). E shows numerous goblet cells (dotted black arrows), and hypertrophy of muscle layer (black star). At 26 dpi, F (400X) shows an increase in reactive goblet and Paneth’s cells in crypts (thick black arrows), and focal destruction of intestinal villi (thin black arrows). At 26 dpi G (200X) shows immature worms (thick black arrows), dark stained region covering epithelium villi indicating degenerative changes (thin black arrows), and with reactive prominent Paneth’s cells (thick white arrows). At 29 dpi H (X200), shows the marked destruction of apical parts of villi (thin black arrows) and reactive Paneth’s cells in intestinal crypts (thick white arrows)

Progressive damage to the intestinal mucosa and increased mucous secretion were observed on 22, 26 and 29 dpi in all samples of the non-treated group. In some samples, mature adult worms with focal hypertrophy of the muscle layer near the area of attachment to intestinal crypts were observed (Figs. 2C-H).

Histological Observations of Group (C)

The efficacy of PZQ treatment in eliminating worms was duration dependent, as no mature worms were detected after one day of treatment (16 dpi). As shown in Fig. 3A, the integrity of the normal mucosal surface was not completely maintained. In addition, mild apoptotic and degenerative alterations were prevalent in some crypts and villi.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of ileum sections from Group C (stained with H&E). At 16 dpi, A (X200) shows intact villi with some dark stained regions in both villi and crypts indicating mild degenerative (thin black arrows). At 18 dpi, B (X200) shows a few villi with focal degeneration and desquamation of covering epithelium (thin black arrows). Desquamated cells and increased mucous content in the lumen (black stars). Some crypts showed dark stained apoptotic changes (thick white arrows). At 21 dpi, C (X100), and D (X200), show intact villi (thin black arrows), and mucous secretion in the lumen (black star)

Three days after treatment (18 dpi), no worms were detected, most villi appeared intact, and few villi detected with mild apical degeneration and desquamated cells mixed with mucous secretions. Figure 3B revealed some crypts with dark apoptotic alterations. Similar observations were noticeable on 21 dpi, as shown in Figs. 3C and D.

Histological Observations of Group (D)

The results evidently presented the duration-dependent efficacy of pumpkin seeds in eradication of H. nana infection. Although the efficacy of PSE was relatively lower than that of PZQ, it showed better and more significant results in improving and protecting the integrity of the mucosa compared to PZQ.

After three days of treatment (18 dpi), worms were observed in some samples with slight improvement in the histology of the intestinal mucosa, as the intestinal crypts looked normal, and villi showed the presence of mononuclear leukocytes (Figs. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Photomicrographs of ileum sections from Group D (stained with H&E). At 18 dpi, A (X100) and B (X400), show mild improvement of intestinal mucosa histology. Villi still with atrophy and desquamation of apical epithelium (thin black arrows), mucous secretion in the lumen (black star), mononuclear leukocyte cells in the villus core (white star), and crypt showed reactive Paneth’s cells (thick white arrows). At 22 dpi, C (X100) shows adult worms (thick black arrows), less changes in villi (thin black arrows) and crypts (thick white arrows). D (at 22 dpi, X200) shows some inflammatory changes in villus core (white star), focal loss of covering epithelium (thin black arrows), and a worm with swollen scolex and degenerated suckers (thick black arrows). E (at 26 dpi, X200) shows normal villi with few mononuclear leukocytes and intact covering epithelium (thin black arrows), few reactive goblet cells (dotted arrows) and Paneth’s cells (thick white arrows). At 29 dpi F (X400) shows marked maintaining of normal structure of villi (thin black arrows) and crypts (thick white arrow), decrease in mononuclear leukocytes (white star) and goblet cells (dotted arrows), with normal thickness of muscle layer (black star)

After 7 days of treatment (22 dpi), the normal structure of the intestinal villi and crypts was markedly preserved with a decrease in the infiltrate of mononuclear leukocytes into the villi. Some samples indicated the presence of worms (Figs. 4C and D).

After 11 days, the administration of the PSE (26 dpi) presented marked normal villi and crypts structure. Reactive goblet and Paneth’s cells were still observed in some samples (Fig. 4E).

Significant preservation of the normal structure of the intestinal villi and crypts, and a decrease in the number of goblet cells and mononuclear leukocytes were observed after treatment for 13 days (29 dpi). In addition, the muscle layer thickness was normal, and no worms were detected (Fig. 4F).

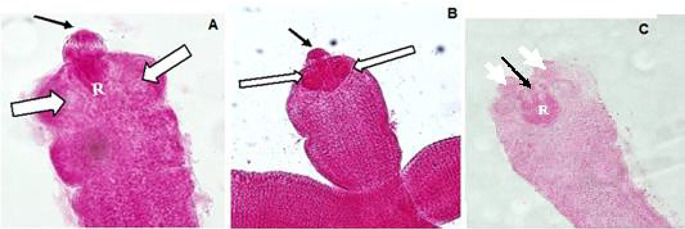

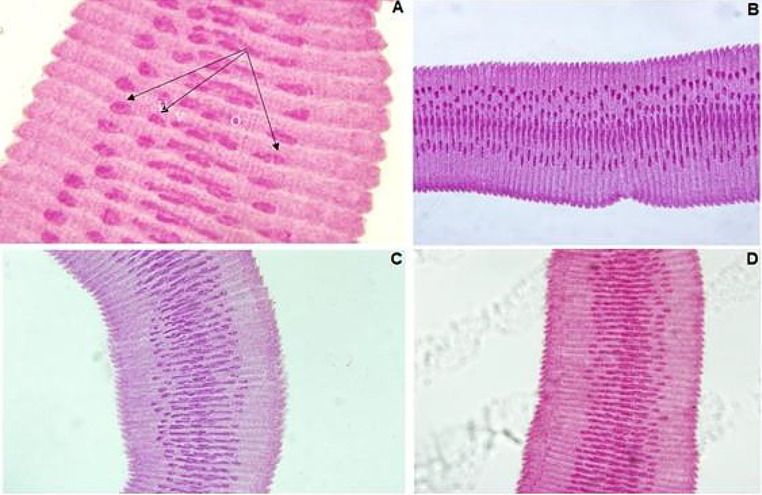

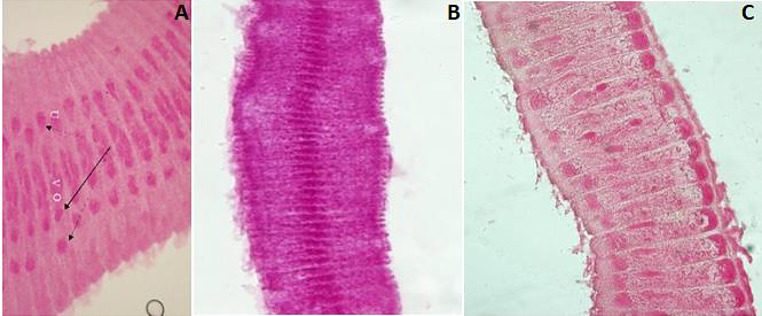

Morphological Features of Adult H. nana in Group (B)

The mature adult worm presented scolex, and mature, immature and gravid proglottids (Figs. 5, 6 and 7). The scolex revealed suckers, and armed rostellum with a single circle of hooks. The mature segments were longer than broader (342.85–415.38 μm in length and 14.28–26.92 μm in width), with detectable uterus, testes, vitelline gland, and ovary. On the other hand, gravid segments were broader than longer (373.33–576.92 μm in length and 46.66–76.92 μm in width), with the uterus full of eggs subjugating the entire segment.

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of H. nana scoleces of adult worms isolated from group B stained with Carmine. A (at 18 dpi, X400), B (at 22 dpi, X200) and C (at 29 dpi, X200) show the scolex (thin black arrow), suckers (white arrows) and rostellar sack (R)

Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs of mature segments of H. nana isolated from group B stained with Carmine. A (at 18 dpi, X200), B (at 22 dpi, X100), C (at 26 dpi, X100), and D (at 29 dpi, X100) show the segments are broader than longer with formation of the internal organs, and the three testes (thin black arrows)

Fig. 7.

Photomicrographs of gravid segments of H. nana isolated from group B stained with Carmine (X100). A (at dpi18), B (at dpi 22), C (at dpi 26), and D (at dpi 29), show each segment is wider than longer, with the uterus full of eggs

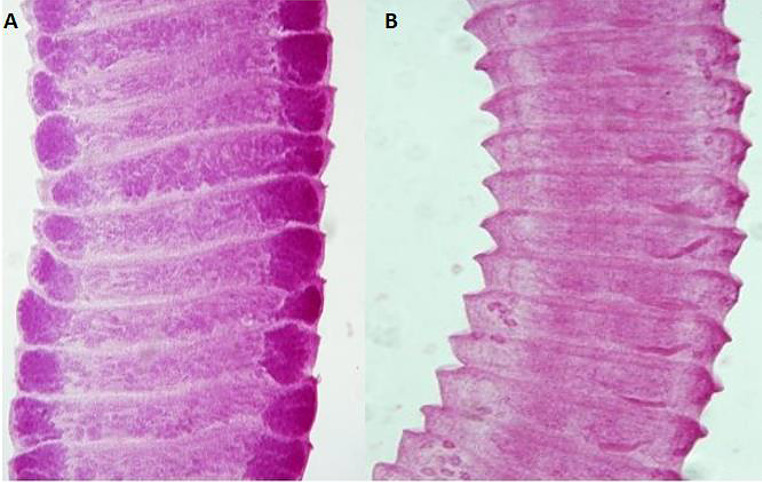

Morphological Alteration of Adult H. nana in Treated Group (D)

The morphological changes because of PSE administration in adult worms of H. nana demonstrated an observable reduction in the sizes of the gravid and mature proglottids. The mature segment size ranged between 261.53 and 346.42 μm and 7.69–21.42 μm, while in gravid segments ranged between 414.28 and 492.30 μm and 30.76–50 μm in length and width, respectively for each. Furthermore, mature segments suffered from loss of internal structure, marginal portion deformity, and blebbing degeneration of the gonads (Fig. 8). Some gravid segments showed a low number of eggs, while other segments revealed the complete absence of eggs. Furthermore, some samples showed malformation and ruptured gravid segments (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Photomicrographs of mature segments of H. nana isolated from group D stained with Carmine. A (at 18 dpi, X200) and B (at day 22 dpi, X100), show deformity of the lateral margins in segments, the three testes (thin black arrows), uterus (U), ovary (O), and vitelline gland. In addition, C (at 26 dpi, X100) shows degeneration and loss of some internal organs

Fig. 9.

Photomicrographs of gravid segments of H. nana isolated from group D stained with Carmine (X100). A (at 22 dpi) shows a decrease in the number of eggs, while B (at 26 dpi) shows some segments completely empty of eggs

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to evaluate ileum histological alterations in mice experimentally infected with H. nana after treatment with C. pepo seeds compared to PZQ. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of PSE on the morphology of the adult dwarf tapeworms.

In agreement with our previous observation [36], the results demonstrated significant efficacy of pumpkin seeds in eliminating H. nana infection. Though the efficacy of PSE was found slightly less than PZQ. Nevertheless, the extract revealed superior and significantly profound results in improving and protecting mucosal integrity compared to PZQ. H. nana, being a more common tapeworm among rodents and humans, presence in the intestine leads to anemia through reduced absorption of folic acid and vitamin B12 [42, 43].

The investigation for a safe alternative treatment is necessary to minimize the hepatotoxic, genotoxic, and carcinogenic side effects of chemotherapy, as well as the relative resistance to chemotherapy and the potential tendency for autoinfection by the tapeworm [44]. A previous study indicated that the average LD50 of PSE in the experimental mice is higher than 5000 mg/kg [45]. Another study reported that long-term feeding of PSE to rats and swine revealed no effect on normal serum chemistry (glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase, glucose, uric acid, urea, protein, creatinine, lactic dehydrogenase, glutamate pyruvate transaminase), blood counts, and urine chemistry (sodium, potassium, protein, creatinine, urea, uric acid) [46]. Cucurbita seeds are known to be a natural source of antiparasitic medicinal properties and antimicrobial effects [34, 47].

Based on previous studies, we administered C. pepo seeds extract at a dose of 500 mg/kg [21, 40]. An in vivo study was conducted on Wister rats to examine the impact of C. pepo seeds extract in colon cancer induced through 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and reported induction of apoptosis in cells at 200 mg/kg dose extract [48]. Another study reported the blockade of “human hepatocarcinoma- HepG2” and “colon carcinoma-CT26” tumor cell lines proliferation with the administration of pumpkin seeds hydro-alcoholic extracts [49]. Another therapeutic effect of taking pumpkin seed extracts at an oral dose of 400 mg/kg was studied to significantly reduce ulcerative lesions in the gastrointestinal tract [50].

The ileum histological features in control Group (A) showed normal mucosa, submucosa, muscle layer and outer serosa, as previously described [51], while the untreated infected Group (B) revealed the presence of the parasite, damaged mucosa, desquamated damaged villus epithelium with increased mucous. Consistent with clinic-pathological and patho-morphological studies on hymenolepiasis model, we observed focal hypertrophy of muscle layer, goblet and Paneth’s cells, predominantly where worms were attached to intestinal crypts [52, 53]. Treatment with PZQ in Group (C) revealed intact villi, light mucous secretion in the lumen, decrease in lymphocytic infiltration, and reservation of the normal musculosa thickness with dark apoptotic changes in some crypts. Our results were in partial agreement with a study on Fibricola seoulensis parasite [54]. Treatment with C. pepo seeds extract in Group (D) demonstrated restoration of intestinal tissue, and the normal thickness of the mucosa villi compared with untreated infected Group (B). Similar observations have been reported by a previous study using Carica papaya extract [51].

Compared to PZQ, and in support of our previous study [36], the current study indicates that pumpkin seed extract is a promising, cheap, natural alternative anthelmintic therapy, more effective and superior in protecting and improving the mucosal integrity. The extract maintained the normal structure of the villi and crypts with normal thickness of the muscle layer and decreased the number of mononuclear leukocyte and goblet cells.

The results of our study showed morphological changes in the infected control group with mature segments being longer than broader, while the gravid segments were broader than longer. The treatment group with PSE showed clear morphological changes of the adult H. nana including a reduction in the size of the gravid and mature proglottids. In addition, fragmented adult worms presented quick loss of movability. The mature segments’ marginal portion demonstrated a loss or deformed internal structures. The gravid segments showed compromised egg production or empty uterus. This evidenced that the PSE tenanted the growth of the parasite adult worms. A previous study reported that the length of H. nana was affected by treatment with Commiphora molmol extract [55]. Another study using C. pepo seeds extract for treatment of Heligmosomoides bakeri reported anthelmintic effect on hatching of the eggs, development of larvae, and motility of adult worms [28].

In agreement with previous observations by Sanad and Al-Furaeihi [56], adult worms of all infected control groups in our study revealed normal width, length, and shape. The mature segments were wider than lengthier, comprehending the uterus, testes, ovary, and vitelline glands. On the other hand, the uterus of the gravid segments was full of eggs. Normal globular scoleces, each with an armed rostellum of a single circle of hooks and four suckers were also observed. There was no major noticeable shift in the scolex of the treated group, although a few gaping holes were noted.

In agreement with our previous observations [36], the current study supports the recommendation for the use of pumpkin seeds as a safe, cost-effective, and natural alternative therapy for infection with H. nana.

To overcome the limitations of our study, further research is needed on the immunological markers, the mechanism of active components of pumpkin seeds, and anti-parasitic efficiency using different concentrations. In addition, scanning and transmission electron microscopy can be used for further details of the worms’ surface morphology and inner structure.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very thankful to all the associated personnel for their beneficial help and cooperation.

Author Contributions

M.H.W. supervised the study and critically reviewed the manuscript; M.H.W. and A.O.A. prepared the design of the study and drafted the manuscript; all authors performed interpretation of data, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted after approval (FAMS-EC2018-009) from the Research and Ethics Committee in the Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goudarzi F, Mohtasebi S, Teimouri A, Yimam Y, Heydarian P, Salehi Sangani G, Abbaszadeh Afshar MJ (2021) A systematic review and meta-analysis of Hymenolepis nana in human and rodent hosts in Iran: A remaining public health concern. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 74:101580. 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badry EM, Hussien AA, Mohammed ES, Mubarak AG (2023) Prevalence of Hymenolepis nana infection in Aswan Governorate and associated risk factors assessment. SVU-Int J Vet Sci 6:55–69. 10.21608/SVU.2023.191180.1256 [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC: Hymenolepiasis (2024) Accessed: August 10, 2024: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/hymenolepiasis

- 4.Cabada MM, Morales ML, Lopez M, Reynolds ST, Vilchez EC, Lescano AG, Gotuzzo E, Garcia HH, White CA Jr (2016) Hymenolepis nana impact among children in the highlands of Cusco, Peru: an emerging neglected parasite infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 95:1031. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solorzano-Alava LF, Sanchez-Amador FI, Sanchez-Giler S, Pizarro VJ (2021)R. rattus and R. norvegicus, as reservoirs of zoonotic endoparasites in Ecuador. Rev MVZ Córdoba. 26(3):e1260. 10.21897/rmvz.1260

- 6.Rahman HU, Khan W, Mehmood SA, Ahmed S, Yasmin S, Ahmad W, Haq ZU, Shah MIA, Khan R, Ahmad U, Khan AA, De Los Ríos Escalante P (2021) Prevalence of cestodes infection among school children of urban parts of Lower Dir district, Pakistan. Braz J Biol 82:e242205. 10.1590/1519-6984.242205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Mekhlafi HM (2020) The neglected cestode infection: epidemiology of Hymenolepis nana infection among children in rural Yemen. Helminthologia 57:293–305. 10.2478/helm-2020-0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coello Peralta RD, Salazar Mazamba ML, Pazmiño Gómez BJ, Cushicóndor Collaguazo DM, Gómez Landires EA, Ramallo G (2023) Hymenolepiasis caused by Hymenolepis nana in humans and natural infection in rodents in a marginal urban sector of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Am J Case Rep 24:e939476. 10.12659/AJCR.939476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang D, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Liu A (2017) Prevalence of Hymenolepis nana and H. diminuta from brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Heilongjiang Province, China. Korean J Parasitol 55:351–355. 10.3347/kjp.2017.55.3.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson RC (2015) Neglected zoonotic helminths: Hymenolepis nana, Echinococcus canadensis and Ancylostoma ceylanicum. Clin Microbiol Infect. 21:426– 432. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito A (2015) Basic and applied problems in developmental biology and immunobiology of cestode infections: Hymenolepis, Taenia and Echinococcus. Parasite Immunol 37:53–69. 10.1111/pim.12167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beshay EVN (2018) Therapeutic efficacy of Artemisia absinthium against Hymenolepis nana: in vitro and in vivo studies in comparison with the anthelmintic praziquantel. J Helminthol 92:298–308. 10.1017/S0022149X17000529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abd El-Hack ME, Alagawany M, Farag MR, Tiwari R, Karthik K, Dhama K (2016) Nutritional, healthical and therapeutic efficacy of black cumin (Nigella sativa) in animals, poultry and humans. Int Res J Pharma 12:232–248. 10.3923/ijp.2016.232.248 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafarian A, Zolfaghari B, Parnianifard M (2012) Effects of methanolic, chloroform, and ethylacetate extracts of the Cucurbita pepo L. on the delay type hypersensitivity and antibody production. Res Pharma Sci 7:217–224. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3523413/pdf/JRPS-7-217.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez R (2016) Review of Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin) its phytochemistry and pharmacology. Med Chem 6:12–21. 10.4172/2161-0444.1000316 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh A, Kumar V (2022) Nutritional, phytochemical, and antimicrobial attributes of seeds and kernels of different pumpkin cultivars. Food Front 3:182–193. 10.1002/fft2.117 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Šamec D, Loizzo MR, Gortzi O, Çankaya İT, Tundis R, Suntar İ, Shirooie S, Zengin G, Devkota HP, Reboredo-Rodríguez P, Hassan STS, Manayi A, Kashani HRK, Nabavi SM (2022) The potential of pumpkin seed oil as a functional food-A comprehensive review of chemical composition, health benefits, and safety. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 21:4422–4446. 10.1111/1541-4337.13013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batool M, Ranjha MMAN, Roobab U, Manzoor MF, Farooq U, Nadeem HR, Nadeem M, Kanwal R, AbdElgawad H, Al Jaouni SK, Selim S, Ibrahim SA (2022) Nutritional value, phytochemical potential, and therapeutic benefits of pumpkin (Cucurbita sp). Plants 11:1394. 10.3390/plants11111394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mwangi JW, Kiragu D, Chaka B (2024) Phytochemical screening, FTIR and GCMS analysis of Cucurbita pepo seeds cultivated in Kiambu County, Kenya. Heliyon 10:e30237. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gavril Rațu RN, Stoica F, Lipșa FD, Constantin OE, Stănciuc N, Aprodu I, Râpeanu G (2024) Pumpkin and pumpkin by-products: A comprehensive overview of phytochemicals, extraction, health benefits, and food applications. Foods 13:2694. 10.3390/foods13172694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou Shady OM, Basyoni MMA, Mahdy OA, Bocktor NZ (2014) The effect of praziquantel and Carica papaya seeds on Hymenolepis nana infection in mice using scanning electron microscope. Parasitol Res 113:2827–2836. 10.1007/s00436-014-3943-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waller PJ, Bernes G, Thamsborg SM, Sukura A, Richter SH, Ingebrigtsen K, Hoglund J (2001) Plants as de-worming agents of livestock in the nordic countries: historical perspective, popular beliefs and prospects for the future. Acta Vet Scand 42:31–44. 10.1186/1751-0147-42-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magi E, Talvik H, Jarvis T (2005) In vivo studies of the effect of medicinal herbs on the pig nodular worm (Oesophagostomum spp). Helminthologia 42:67–69. https://pau.saske.sk/ext/helminthologia/2005_2/Magi67.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Rahman MK (2006) Effect of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo L.) diets on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): chemical and morphometric evaluation in rats. World J Chem 1:33–40. https://silvershell.com.tr/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ref.-58.-Abdel-Rahman-2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.François G, Nathalie B, Jean-Pierre V, Daniel P, Didier M (2006) Effect of roasting on tocopherols of gourd seeds (Cucurbita pepo). Grasas Aceites. 57:409– 14. https://grasasyaceites.revistas.csic.es/index.php/grasasyaceites/article/view/67/64

- 26.Ayaz E, Gokbulut C, Coskun H, Türker A, Özsoy Ş, Ceylan K (2015) Evaluation of the anthelmintic activity of pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita maxima) in mice naturally infected with Aspiculuris tetraptera. J Pharmacogn Phytother 7:189–193. 10.5897/JPP2015.0341 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acorda J, Mangubat I, Ysabela E, Divina B (2019) Evaluation of the in vivo efficacy of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) seeds against gastrointestinal helminths of chickens. Turkish J Vet Anim Sci 43:206–211. 10.3906/vet-1807-39 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grzybek M, Kukula-Koch W, Strachecka A, Jaworska A, Phiri AM, Paleolog J (2016) Evaluation of anthelmintic activity and composition of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seed extracts-in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Molecu Sci 17:1456. 10.3390/ijms17091456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vennerstrom JL, Lovelace JK, Wait VB, Hanson WL, Klayman DL (1990) Berberine derivatives as antileishmanial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:918–921. 10.1128/AAC.34.5.918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Da-Cunha EV, Fechinei IM, Guedes DN, Barbosa-Filho JM, Da Silva MS (2005) Protoberberine alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem Biol 62:1–75. 10.1016/s1099-4831(05)62001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krivogorsky B, Pernat JA, Douglas KA, Czerniecki NJ, Grundt P (2012) Structure-activity studies of some berberine analogs as inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondii. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22:2980–2982. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dkhil MA (2014) Role of berberine in ameliorating Schistosoma mansoni-induced hepatic injury in mice. Biol Res 47:1–7. 10.1186/0717-6287-47-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapaat A, Satrija F, Mahsol H, Ahmad AH (2012) Anthelmintic activity of papaya seeds on Hymenolepis diminuta infections in rats. Trop Biomed 29:508–512. https://www.msptm.org/files/508_-_512_Sapaat_A.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li T, Ito A, Chen X, Long C, Okamoto M, Raoul F, Giraudoux P, Yanagida T, Nakao M, Sako Y, Xiao N, Craig PS (2012) Usefulness of pumpkin seeds combined with areca nut extract in community-based treatment of human taeniasis in Northwest Sichuan Province, China. Acta Trop 124:152–157. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ammar AI, Afifi AF, Essa A, Galal-Khallaf A, Mokhtar MM, Shehab-Eldeen S, Rady AA (2020) Cucurbita pepo seed oil induces microsatellite instability and tegumental damage to Schistosoma mansoni immature and adult worms in vitro. Infect Drug Resist 13:3469–3484. 10.2147/IDR.S265699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alhawiti AO, Toulah FH, Wakid MH (2019) Anthelmintic potential of Cucurbita pepo seeds on Hymenolepis nana. Acta Parasitol. 64:276– 281 10.2478/s11686-019-00033-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia LS, Arrowood M, Kokoskin E, Paltridge GP, Pillai DR, Procop GW (2017) Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: laboratory diagnosis of parasites from the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Microbiol Rev 31:e00025–e00017. 10.1128/CMR.00025-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH (2022) Molecular, microscopic, and immunochromatographic detection of enteroparasitic infections in hemodialysis patients and related risk factors. Foodborne Pathog Dis 19:830–838. 10.1089/fpd.2022.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Refai MF, Wakid MH (2024) Prevalence of intestinal parasites and comparison of detection techniques for soil-transmitted helminths among newly arrived expatriate labors in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 12:e16820. 10.7717/peerj.16820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AL-Bayati NY, AL-Aubaidi IK, AL-Haidari SHJ (2009) Anticestodal activity of the crude aqueous extract of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo) against the dwarf tapeworm (Hymenolepis nana) in mice. Ibn Al-Haitham J Pure App Sci 22:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suvarna SK, Layton C, Bancroft JD (2018) Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques, 8th edn. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spinicci M, Macchioni F, Gabrielli S, Rojo D, Gamboa H, Villagrán AL (2018) Hymenolepis nana- an emerging intestinal parasite associated with anemia in school children from the Bolivian Chaco. Am J Trop Med Hyg 99:1598–1601. 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wasihun AG, Teferi M, Negash L, Marugán J, Yemane D, McGuigan KG (2020) Intestinal parasitosis, anaemia and risk factors among pre-school children in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 20:379. 10.1186/s12879-020-05101-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Omar A, Elmesallamy GE, Eassa S (2005) Comparative study of the hepatotoxic, genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of praziquantel distocide and the natural myrrh extract Mirazid on adult male albino rats. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 35:313–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cruz RCB, Meurer CD, Silva EJ, Schaefer C, Santos ARS, Bella Cruz A (2006) Cechinel Filho V. Toxicity evaluation of Cucurbita maxima seed extract in mice. Pharma Bio 44:301–303. 10.1080/13880200600715886 [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Queiroz-Neto A, Mataqueiro MI, Santana AE, Alessi AC (1994) Toxicologic evaluation of acute and subacute oral administration of Cucurbita maxima seed extracts to rats and swine. J Ethnopharmacol 43:45–51. 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90115-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel S (2013) Pumpkin (Cucurbita sp.) seeds as nutraceutic: a review on status quo and scopes. Med J Nutr Metab 6:183–189. 10.1007/s12349-013-0131-5 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chari KY, Polu PR, Shenoy RR (2018) An appraisal of pumpkin seed extract in 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon cancer in Wistar rats. J Toxicol 2018:6086490. 10.1155/2018/6086490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shokrzadeh M, Azadbakht M, Ahangar N, Hashemi A (2010) Cytotoxicity of hydro-alcoholic extracts of Cucurbita pepo and Solanum nigrum on HepG2 and CT26 cancer cell lines. Pharmacogn Mag 6:176. 10.4103/0973-1296.66931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gad KY, Kholief TES, Barakat H, El-Masry S (2019) Evaluation of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) pulp and seeds extracts on gastrointestinal ulcers induced by indomethacin in rats. J Sci Res 36:184–200. 10.21608/JSRS.2019.34277

- 51.Mohammed ST, Sulaima NM (2014) Antihemintic and hematological changes of natural plant Carica papaya seed extract against gastrointestinal nematode Hymenolepis nana. J Biol Agric Healthc 4:8–13. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JBAH/article/view/10974/11275 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Movsesyan S, Jivanyan K, Chubaryan F, Malczewski A (2008) Experimental hymenolepiasis of rats: preliminary data on histopathological changes of visceral organs. Acta Parasitol 53:193–196. 10.2478/s11686-008-0023-x [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goswami R, Singh SM, Kataria M, Somvanshi R (2011) Clinicopathological studies on spontaneous Hymenolepis diminuta infection in wild and laboratory rats. Braz J Vet Pathol. 4:103– 111. https://bjvp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/DOWNLOAD-FULL-ARTICLE-19-20881_2011_7_11_53_13.pdf

- 54.Lee SH, Kim BI, Hong ST, Sohn WM (1989) Observation of mucosal pathology after praziquantel treatment in experimental Fibricola seoulensis infection in rats. Korean J Parasitol 27:35–40. 10.3347/kjp.1989.27.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bayoumy A, Abou El-Nour B, Ali EA (2015) Comparative parasitological study on treatment of Hymenolepis nana among immunocompetent and immunocompromised infected mice. Glob Vet 15:414–422 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanad MM, Al-Furaeihi LM (2006) Effect of some immunomodulators on the host-parasite system in experimental Hymenolepiasis nana. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 36:65–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.