Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To develop the first core Critical Care Data Dictionary (C2D2) with common data elements (CDEs) to characterize critical illness and injuries.

DESIGN:

Group consensus process using modified Delphi approach.

SETTING:

Electronic surveys and in-person meetings.

SUBJECTS:

A multidisciplinary workgroup of clinicians and researchers with expertise in the care of the critically ill and injured.

INTERVENTIONS:

The Delphi process was divided into domain and CDE portions with each composed of two item generation rounds and one item reduction/refinement rounds. Two in-person meetings augmented this process to facilitate review and consideration of the domains and by panel members. The final set of domains and CDEs was then reviewed by the group to meet the competing criteria of utility and feasibility, resulting in the core dataset.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

The 23-member Delphi panel was provided 1833 candidate variables for potential dataset inclusion. The final dataset includes 226 patient-level CDCs in nine domains, which include anthropometrics and demographics (8), chronic comorbid illnesses (18), advanced directives (1), ICU diagnoses (61), diagnostic tests (42), interventions (27), medications (38), objective assessments (26), and hospital course and outcomes (5). Upon final review, 91% of the panel endorsed the CDCs as meeting criteria for a minimum viable data dictionary. Data elements cross the lifespan of neonate through adult patients.

CONCLUSIONS:

The resulting C2D2 provides a foundation to facilitate rapid collection, analyses, and dissemination of information necessary for research, quality improvement, and clinical practice to optimize critical care outcomes. Further work is needed to validate the effectiveness of the dataset in a variety of critical care settings.

Keywords: adult, common data elements, intensive care, neonates, pediatric, standard definitions

KEY POINTS.

Question: What domains and common data elements should be included in a core Critical Care Data Dictionary?

Findings: Using a modified Delphi process, a 23-member panel developed the first core Critical Care Data Dictionary to characterize critical illness and injury. The data dictionary includes nine domains and 226 common data elements, which can be applied to neonatal through adult patients.

Meaning: The dataset is intended to provide a foundation for the rapid collection, analysis, and dissemination of information necessary for research, quality improvement, and clinical practice to optimize critical care outcomes.

In the United States, critical care healthcare costs have been estimated to be 13% of hospital expenditures and have increased by 92% with a total cost of $108 billion U.S. dollars over a 10-year period (2000–2010) (1). Mortality rates exceed those of all other hospital care areas with one in five deaths occurring in the critical care setting (2). Strategies to improve patient outcomes and contain costs lie in identifying critical care research priorities, conducting innovative research, and translating evidence into practice. Accomplishing these goals depends upon robust data aggregation, analysis, and reporting (3).

The current state of critical care data infrastructure faces multiple limitations. Highly customizable electronic health record (EHR) platforms (e.g., Epic, Cerner, Meditech) promote fit-for-purpose interfaces for clinical practice, but also drive heterogeneity in data structure, limiting data usability for multi-institution clinical research (4–6). Harmonizing data from multiple sources is time-intensive and costly, and secondary sources (e.g., registries and repositories) often have limited interoperability and reusability (7, 8). These realities hampered the COVID-19 response by hindering the ability to rapidly establish the large-scale databases necessary to generate clinical knowledge (e.g., risk factors, symptom progression, pathophysiology, effective therapies, outcomes) within and across patient populations (9–11). Left unaddressed, these limitations will undoubtedly present challenges in future pandemics.

To address these limitations, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) launched a workgroup within the Discovery Oversight Committee to identify gaps in critical care research and the strategies necessary to address those gaps. In 2022, Discovery, the Critical Care Research Network, developed a robust 5-year research agenda, which included the creation of the Discovery Data Science Campaign (DSC) (12). Within its large-scale data harmonization and data sharing initiative, the DSC recognized the need to develop a Critical Care Data Dictionary (C2D2) with standardized common data elements (CDEs) to facilitate the development of a robust data infrastructure, support, and perform pilot projects, implement the C2D2, and evaluate usability and efficacy. This article describes the results of a modified Delphi process used to develop the data dictionary with CDEs.

METHODS

Design

The Delphi method is a proven strategy for addressing crucial clinical inquiries lacking strong evidence (13–15). Specifically applied in healthcare, it harnesses expert opinions through iterative rounds of consensus and voting (16, 17). A “modified” Delphi enhances this process by integrating other strategies (e.g., in person meetings) to foster interactive discussions and accommodate new evidence, while maintaining the strengths of the traditional Delphi process (18).

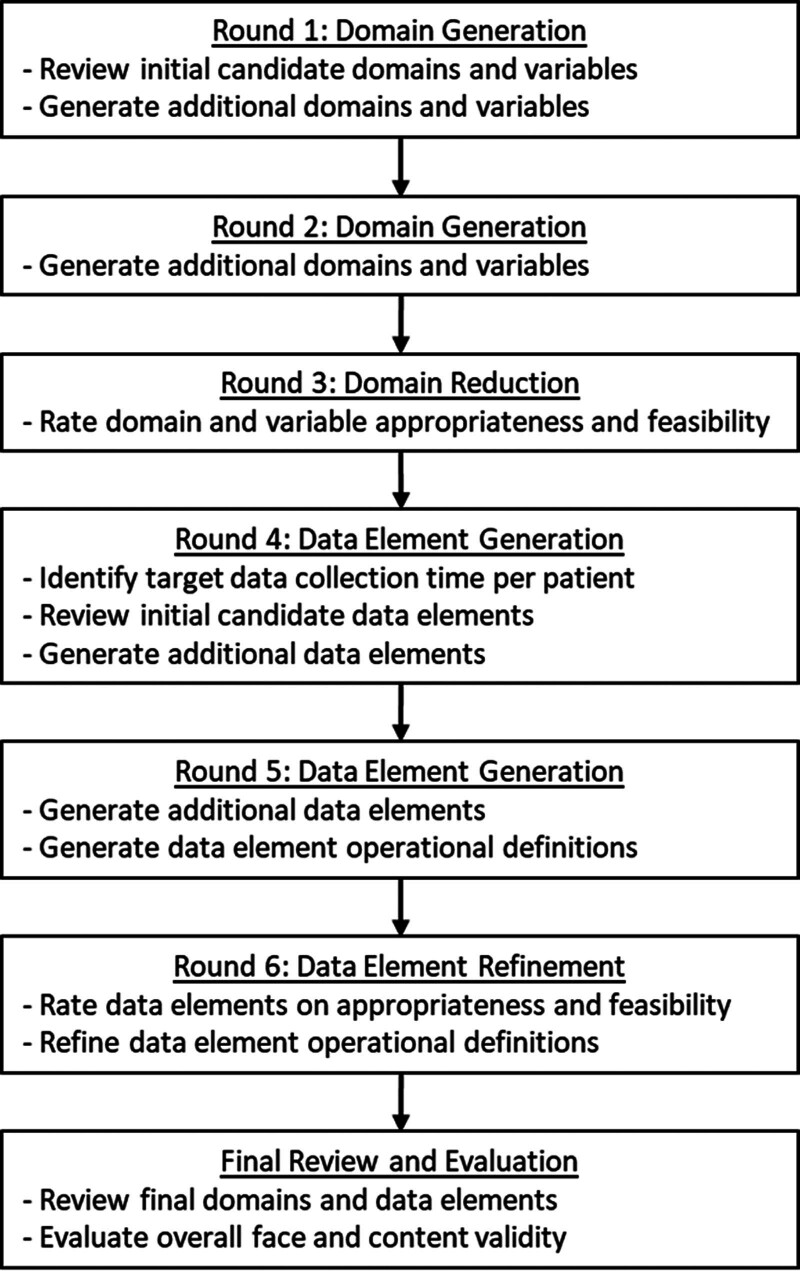

We divided our consensus process into domain (i.e., high level category) and data element (i.e., specific measure), portions with each portion composed of two item generation rounds and one item reduction/refinement round (Fig. 1). Delphi rounds leveraged online surveys (Welphi.com, Lisbon, Portugal) to facilitate asynchronous participation, regardless of location. Members were requested to complete surveys within 2 weeks of receipt, receiving reminders 1 week after the initial distribution to encourage full participation across all rounds. The traditional Delphi process was augmented by two in-person meetings to facilitate review and consideration of the domains and data elements by panel members. The Delphi process was classified as nonhuman subjects research by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of consensus process.

Panel Participants

SCCM sought participants for a multidisciplinary panel comprising clinicians and investigators with extensive experience in acute and critical care across all age groups (Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H679). Leadership also sought to include a broad range of nonclinical expertise, including basic science, clinical research, data science, informatics, and quality improvement. Experts were initially selected based on clinical or technical expertise to create a critical mass of greater than 20 for the modified Delphi process, with interest to include experts who had neonatal, pediatric, and adult clinical expertise, in addition to technical industry experts. There was also an emphasis to ensure gender balance and actively promote the inclusion of underrepresented minorities across all groups. All participants completed conflict of interest documentation, which was confirmed at each Delphi interval.

Framework

Participants were guided by a framework (Table 1) throughout the process, outlining the concept, purpose, and operational characteristics of the common dataset. The dataset’s aim is to capture essential information about critical care patients upon their presentation to the ICU (e.g., age, diagnosis) and their clinical care details (e.g., medications, interventions, diagnostic tests), with outcomes assessed at facility discharge. Due to the varied resources available across critical care locations, the panel sought to design the initial dataset to enable manual data capture while also ensuring compatibility with automated extraction from an EHR. Furthermore, the panel sought to leverage prior work by incorporating existing composite disease severity scores and other data tools where feasible.

TABLE 1.

Framework for Core Dataset and Data Attributes

| Strategy |

| Support use across the human lifespan including neonatal, pediatric, and adult populations |

| Support use across the spectrum of clinical illness and injuries experienced by critically ill patients |

| Purpose |

| Capture information to determine adequacy and value of resource utilization |

| Provide information on patient outcomes across time |

| Characteristics |

| Feasible across all critical care settings |

| Extensible to provide project-specific information |

| Facilitate manual and electronic data abstraction |

| Real-time capture of information across spectrum of care |

| Data attribute: Four tiers of item categorization |

| Domain—high level categories of data (e.g., clinical assessment) |

| Subdomain—smaller group of variables within a domain (e.g., blood pressure) |

| Concept—specific measurement (e.g., MAP) |

| Common data element—concept with defined framework for collection including temporality and plausibility rules (e.g., lowest MAP in first 24 hr of ICU admission measured by cuff) |

MAP = mean arterial pressure.

Additionally, the workgroup conceptualized four tiers of item categorization: 1) “domain,” high level categories of variables (e.g., vital signs); 2) “subdomain,” smaller group of variables within a domain (e.g., blood pressure); 3) “concept,” specific measurements or variables (e.g., mean arterial pressure [MAP]); and 4) “CDEs,” with defined framework for collection, including temporality and plausibility rules (e.g., lowest MAP in first 24 hr of ICU admission, measured by arterial line).

Domain Focus (Rounds 1–3)

After agreeing to participate, panel members suggested data dictionaries that addressed relevant clinical and research activities. Biostatisticians combined these into an initial dataset, forming the basis for the Delphi study to identify critical care CDEs. Workgroup members with specific data science expertise then categorized these initial concepts into domains and subdomains, which provided the infrastructure for the initial dataset.

A virtual introductory meeting was held where the panel discussed the overarching framework, received an overview of the process, and reviewed the initial dataset for clarity regarding the next steps. During round 1, the panel received the initial dataset and were instructed to propose additional domains and associated subdomains. These additions were aggregated anonymously into a revised dataset, which was subsequently circulated among the group for round 2 of evaluation, where panelists were able to propose additional domains, subdomains, and concepts.

In round 3, panel members considered the significance and feasibility of each proposed domain and subdomain. Members then rated each domain and subdomain on a scale of 1–9 (1–3 being not important to the core dataset; 4–6 important but not critical; 7–9 critically important). Domains and subdomains rated as “critically important” by greater than 80% of the panel were advanced to be represented in the final dataset.

Data Element Phase (Rounds 4–6)

The remaining rounds of the modified Delphi focused on generating and refining specific concepts. An in-person meeting was conducted to review the defined domains with associated subdomains and concepts extracted from the foundational data dictionaries in the context of the overarching framework. The panel was organized into multidisciplinary, domain-specific breakout groups to construct a list of candidate CDEs with associated operational definitions.

In round 4, the members were asked to identify the target data collection time per patient, review the initial candidate CDEs, and propose additional CDEs with associated operational definitions. The additional CDEs were aggregated and circulated to the panel for additional CDE proposals during round 5.

Round 6 began with an in-person meeting at SCCM Congress, where the panel reviewed and refined CDE operational definitions. Specifically, experts reviewed the data dictionary to determine whether existing CDEs were sufficient for each severity score or if additional concepts and CDEs were needed. The updated data dictionary was disseminated to panel members, who rated elements on importance and feasibility. Panelists were also given the option to further refine CDE operational definitions.

The final core dataset was reviewed by the panel for content clarity, construct validity, feasibility, and overall alignment with the project objective. Panelists voted electronically on final agreement of the resulting data dictionary with selected CDEs. An a priori consensus threshold of greater than 80% endorsement was set to complete the consensus process and finalize the dataset.

RESULTS

Participants

Of the 23 panel members, 91% work at academic medical centers, 9% work for government agencies, 4% are a part of nonprofit organizations, and 4% are employed in industry (Table 2). The panel included a broad range of educational backgrounds, including but not limited to master’s or PhD trained researchers (74%), physicians (57%), nurses (13%), and pharmacists (13%). The majority (87%) of the group had clinical expertise in critical care, with eight other clinical specialties (e.g., neonatal, pediatric, anesthesiology, emergency medicine). Panelists contributed a broad range of nonclinical expertise including clinical research (61%), data science (61%), quality improvement (48%), and clinical informatics (35%).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Workgroup (n = 23)

| Participant | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Employment type | |

| Academic medicine | 21 (91) |

| Other nonprofit | 2 (9) |

| Government | 1 (4) |

| Industry | 1 (4) |

| Education | |

| Research (MA, MS, PhD) | 17 (74) |

| Physician (MD, DO) | 13 (57) |

| Nursing (RN, NP) | 3 (13) |

| Pharmacy (PharmD) | 3 (13) |

| Respiratory therapy (RT) | 2 (9) |

| Physical therapy (DPT) | 1 (5) |

| Clinical specialty | |

| Critical care medicine | 20 (87) |

| Pediatrics | 4 (17) |

| Anesthesiology | 2 (9) |

| Emergency medicine | 2 (9) |

| Pulmonology | 2 (9) |

| Internal medicine | 1 (5) |

| Neonatology | 1 (5) |

| Neurology | 1 (5) |

| Surgery | 1 (5) |

| Other expertise | |

| Clinical research | 14 (61) |

| Data science | 14 (61) |

| Quality improvement | 11 (48) |

| Clinical informatics | 8 (35) |

| Translational science | 7 (30) |

| Implementation science | 5 (22) |

| Clinical trialist | 4 (17) |

| Bench science | 3 (14) |

| Telehealth | 2 (9) |

DO = Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine, DPT = Doctor of Physical Therapy, MA = Master of Arts, MD = Medical Doctor, MS = Master of Science, NP = Nurse Practitioner, PharmD = Doctor of Pharmacy, PhD = Doctor of Philosophy, RN = Registered Nurse, RT = Respiratory Therapist.

Percentages exceed 100%.

Delphi Rounds

Initially, five existing data dictionaries were reviewed as prior work, with two being eliminated due to overlap or narrow focus (4, 19). Three data dictionaries from SCCM-sponsored studies—the Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study COVID-19 Registry (VIRUS), Severe Acute Respiratory Infection Preparedness (SARI-PREP), and International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC)—were retained and compiled into an initial pre-Delphi dataset, with 19 domains and 125 subdomains (Table 3) (20–22). After the first two rounds of domain generation, the dataset had increased to 20 domains, including 191 subdomains. After round 3 of the consensus process (item reduction), the panel identified nine domains and 36 subdomains as critically important to a minimal viable core dataset, and these were retained to inform the subsequent phases.

TABLE 3.

Domain and Subdomain Results After the First Three Modified Delphi Rounds

| Level | No. of Domains | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (Round 0) | Item Generation (After Round 2) | Item Reduction (After Round 3) | ||

| Domain | 19 | 20 | 9 | Diagnoses, outcomes |

| Subdomain | 125 | 191 | 36 | Weight, blood pressure |

At the beginning of round 4, most of the group (57%) agreed that 10–30 minutes was the ideal time to manually collect basic patient-level data. The remaining (43%) of the group voted that more than 30 minutes was an ideal collection time. CDE generation and refinement in rounds 4–6 increased the total number of CDEs in the core data set from 104 to 226 (Table 4). Most CDEs were included in the diagnoses, diagnostic tests, and medication domains of the final dataset (61, 42, and 38, respectively). Several CDEs were added within a single concept due to different required assessment times (e.g., first 4 hr vs. first 24 hr) or different desired values (e.g., highest and lowest oxygen saturation within the first 24 hr of ICU admission). Upon final review, the a priori consensus threshold of greater than 80% was met with a final vote of 91% (n = 21) yes; 4.3% (n = 1) no; and 4.3% (n = 1) missing.

TABLE 4.

Common Data Element Results After the Second Three Modified Delphi Rounds

| Domain | No. of Common Data Elements | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | ||

| Advanced directives | 5 | 1 | Last code status at 24 hr in ICU |

| Anthropometrics and demographics | 10 | 8 | Age, sex, first documented weight |

| Chronic comorbid illnesses | 20 | 18 | Mild liver disease, dementia |

| Diagnoses | 3 | 61 | Asthma, necrotizing enterocolitis, trauma |

| Diagnostic tests | 25 | 42 | Platelet count (low), WBC count (high) |

| Interventions | 3 | 27 | Any invasive mechanical ventilation |

| Medications | 21 | 38 | Vancomycin, epinephrine infusion (maximum) |

| Objective assessments | 10 | 26 | Mean arterial blood pressure (low) |

| Outcomes and hospital course | 7 | 5 | Hospital discharge disposition |

| Total | 104 | 226 | |

Final Core Dataset

Overall, the final core dataset included nine domains and 226 CDEs, reflecting the spectrum of clinical illness and injuries experienced by critically ill patients across the human lifespan. The dataset includes a range of individual CDEs important to general critical care populations (e.g., invasive mechanical ventilation support duration, gastrointestinal bleeding) and those more focused on specific ICU patient populations (e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis). Furthermore, the inclusion of select social determinants of health elements (e.g., area deprivation index) enables the evaluation of social factors on a broad range of critical illness and injury (23–25).

Beyond the individual elements, the C2D2 supports multiple disease severity scores: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II (26, 27), APACHE III (28), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (29), Medication Regimen Complexity-ICU (30, 31) scoring tool, pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) (32–34), neonatal SOFA (35), Pediatric Risk of Mortality III (36, 37), Pediatric Index of Mortality 3 (38–40), and SOFA (41–44). The majority of CDEs (181 [80%]) contributed to at least one disease severity score (Supplementary Table 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H679). The full data dictionary is available in an online spreadsheet (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H703).

DISCUSSION

We report the development of a core clinical dataset that provides a standard foundation and template for use in critical care research and quality improvement: the C2D2. The use of a standardized consensus approach, based on the Delphi process, allowed the assembled multidisciplinary workgroup to reach a consensus on the most important information to collect to provide a better understanding of the patient-level data, although still meeting the goal of feasibility for the critical care space. The C2D2 includes elements that characterize disease phenotypes and severity of illness. The dataset is designed to be applicable across the entire patient-care spectrum, including the neonatal, pediatric, and adult populations, in both the academic and community hospital settings. The dataset also provides insights into critical care diagnostics and treatments employed. Finally, the dataset fosters the evaluation of resource matching, critical infrastructure, and operational performance.

Our project highlights the potential synergies achievable by integrating the C2D2 core dataset with data modernization techniques. The incorporation of advanced data collection, management, and analysis methods is poised to amplify the scope and depth of information captured in critical care environments. By coupling these strategies with the stringent definitions established for CDEs, our approach enhances the opportunity to leverage large multisite data capture and data translation, a foundational goal of SCCM’s Discovery Research Network. We also expect that C2D2 can be coupled with other data collection tools for quality improvement, such as the new SCCM Center of Excellence Program reporting standard, to benchmark ICU Liberation Bundle performance. Additionally, C2D2 facilitates the exploration of therapeutics and the formulation of hypotheses under research emergency conditions (such as pandemics) and across diverse domains, including neonatology and pediatrics (S. F. Heavner, unpublished observations, 2025).

The development of C2D2 marks a pivotal starting point in ensuring consistency, interoperability, and clarity in data management across various critical care systems and studies (S. F. Heavner, unpublished observations, 2025). It addresses crucial aspects by clearly defining each data element using standardized terminology, thereby eliminating ambiguity in interpretation. C2D2 assigns unique identifiers to facilitate efficient tracking and referencing across different systems, accompanied by clear descriptions of each CDE’s purpose and relevance. Furthermore, it specifies the data type and format for consistent representation and handling, supporting enforced consistency in data entry, analysis, integrity, and coherence (45, 46).

A strategic imperative is to ensure easy access to C2D2 for all stakeholders while offering comprehensive documentation to aid users in understanding and correctly applying the data elements. One proposed method is using a cloud-based data collection platform as part of SCCM’s datahub initiative. Additionally, this initiative lays the groundwork for aligning C2D2 with relevant metadata standards, such as those established by the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (47), Health Level Seven International, and Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, to improve interoperability and streamline data sharing across systems and studies (48, 49). By tackling these factors, C2D2 can initiate the advancement of consistency, interoperability, and efficiency in data management and analysis processes.

Limitations to this work warrant consideration and future investigation. First, it is essential to acknowledge that the use of the C2D2 core dataset in our study has not been formally validated. While our findings demonstrate its potential benefits, further feasibility assessments across diverse settings are imperative. For instance, the charge from the SCCM DSC specifically includes testing C2D2 in a SCCM Discovery-sponsored study. This DSC pilot study will be multicentered and yield not only important scientific findings related to its study questions but also C2D2 usability and feasibility information to help drive revisions to the data dictionary for use both in the United States and internationally.

Second, despite the advancements made in this study, it is essential to acknowledge that our work is not exhaustive. We recognize that further enhancements and expansions are both warranted and welcomed. To address this, we have initiated the establishment of additional data cassettes that will augment the core dataset in future iterations, including expanded neonatal and pediatric CDEs. Additionally, the standardized taxonomy of patient-level data in the C2D2 can facilitate linking to broader structural/organizational characteristics (e.g., workforce, facilities, costs) captured in U.S. and international databases (e.g., American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] Hospital Provider Cost Report, World Health Organization). These forthcoming additions will ensure the continued international relevance and utility of the dataset in evolving critical care landscapes.

In conclusion, our study provides a testable C2D2 core dataset, the use of which is aimed to improve patient outcomes, develop innovative treatments, implement new research findings, inform quality improvements, and identify critical care research priorities. Planned initiatives will next focus on validating C2D2, along with integrating data modernization techniques, and expanding the dataset to accommodate emerging needs. By addressing these considerations, we can foster a robust and comprehensive framework for data-driven decision-making and innovation in critical care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the contributions of the Discovery Oversight Committee in their review of this article.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Supported, in part, by grant from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Discovery Science Campaign.

Drs. Murphy’s and Sikora’s institutions received funding from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Dr. Murphy’s institution received funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Cruz-Cano’s institution received funding from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). Dr. Kamaleswaran’s institution received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Kamaleswaran, Sikora, Tanner, and Wong received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Badawi received funding from Ceiba Healthcare and CLEW Medical. Dr. Khanna received funding from Medtronic, Edwards Life Sciences, Philips Research North America, GE Healthcare, Retia Medical, Caretaker Medical, BrainX, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Department of Defense, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Rincon received funding from Blue Cirrus Consulting, Baxter Health Consulting, Viven Health, Phillips Health, Hospital Insurance Forum, and Illinois Health and Hospital Association. Drs. Wong, Zimmerman, and Cobb received funding from the SCCM. Dr. Wong received funding from Ataia Medical. Dr. Wynn received funding from Sobi. Dr. Zhang received support for article research from the SCCM. Dr. Zimmerman’s institution received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Immunexpress. Drs. Zimmerman and Reuter-Rice received funding from Elsevier Publishing. Dr. Cobb received funding from Giblib, Akido Labs, and Bauhealth. Dr. Reuter-Rice’s institution received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; she received funding from Delphi. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

This article has an accompanying editorial.

Contributor Information

Wesley Anderson, Email: wanderson@c-path.org.

Smith H. Heavner, Email: sheavner@c-path.org.

Tamara Al-Hakim, Email: tal-hakim@sccm.org.

Raul Cruz-Cano, Email: raulcruz@iu.edu.

Krzysztof Laudanski, Email: Laudanski.Krzysztof@mayo.edu.

Rishikesan Kamaleswaran, Email: r.kamaleswaran@duke.edu.

Omar Badawi, Email: obadawi@gmail.com.

Heidi Engel, Email: Heidi.engel@ucsf.edu.

Jocelyn Grunwell, Email: jgrunwe@emory.edu.

Vitaly Herasevich, Email: vitaly@mayo.edu.

Ashish K. Khanna, Email: akhanna@wakehealth.edu.

Keith Lamb, Email: lambrrt@gmail.com.

Robert MacLaren, Email: rstevens@jhmi.edu.

Teresa Rincon, Email: teresa.rincon@blue-cirrus.com.

Lazaro Sanchez-Pinto, Email: lsanchezpinto@luriechildrens.org.

Andrea N. Sikora, Email: sikora@uga.edu.

Robert D. Stevens, Email: rstevens@jhmi.edu.

Donna Tanner, Email: tannerd2@ccf.org.

William Teeter, Email: William.Teeter@som.umaryland.edu.

An-Kwok Ian Wong, Email: med@aiwong.com.

James L. Wynn, Email: james.wynn@peds.ufl.edu.

Xiaohan T. Zhang, Email: xzhan161@jhmi.edu.

Jerry J. Zimmerman, Email: jerry.zimmerman@seattlechildrens.org.

Vishakha Kumar, Email: vkumar@sccm.org.

J. Perren Cobb, Email: jpcobb@med.usc.edu.

Karin E. Reuter-Rice, Email: karin.reuter-rice@duke.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halpern NA, Goldman DA, Tan KS, et al. : Trends in critical care beds and use among population groups and Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries in the United States: 2000-2010. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:1490–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. ; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-Of-Life Peer Group: Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:638–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutschman CS, Ahrens T, Cairns CB, et al. ; Critical Care Societies Collaborative USCIITG Task Force on Critical Care Research: Multisociety task force for critical care research: Key issues and recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heavner SF, Anderson W, Kashyap R, et al. : A path to real-world evidence in critical care using open-source data harmonization tools. Crit Care Explor. 2023; 5:e0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinglas VD, Cherukuri SPS, Needham DM: Core outcomes sets for studies evaluating critical illness and patient recovery. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020; 26:489–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leese P, Anand A, Girvin A, et al. : Clinical encounter heterogeneity and methods for resolving in networked EHR data: A study from N3C and RECOVER programs. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023; 30:1125–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohane IS, Aronow BJ, Avillach P, et al. ; Consortium for clinical characterization of COVID-19 by EHR (4CE): What every reader should know about studies using electronic health record data but may be afraid to ask. J Med Internet Res. 2021; 23:e22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, et al. : The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016; 3:160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walkey AJ, Sheldrick RC, Kashyap R, et al. : Guiding principles for the conduct of observational critical care research for coronavirus disease 2019 pandemics and beyond: The Society of Critical Care Medicine Discovery Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study Registry. Crit Care Med. 2020; 48:e1038–e1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, et al. ; N3C Consortium: The national COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): Rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021; 28:427–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Reilly-Shah VN, Gentry KR, Van Cleve W, et al. : The COVID-19 pandemic highlights shortcomings in US health care informatics infrastructure: A call to action. Anesth Analg. 2020; 131:340–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Society of Critical Care Medicine: Five Years of Discovery, the Critical Care Research Network. Available at: https://www.sccm.org/blog/five-years-of-discovery,-the-critical-care-research-network. Accessed January 28, 2025 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holey EA, Feeley JL, Dixon J, et al. : An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007; 7:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell C: The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003; 41:376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. : Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998; 2:1–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shang Z: Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023; 102:e32829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graefe A, Armstrong JS: Comparing face-to-face meetings, nominal groups, Delphi and prediction markets on an estimation task. Int J Forecast. 2011; 27:183–195 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khodyakov D, Grant S, Kroger J, et al. : Disciplinary trends in the use of the Delphi method: A bibliometric analysis. PLoS One. 2023; 18:e0289009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashmi ZG, Kaji AH, Nathens AB: Practical guide to surgical data sets: National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB). JAMA Surg. 2018; 153:852–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walkey AJ, Kumar VK, Harhay MO, et al. : The Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study (VIRUS): An international registry of coronavirus 2019-related critical illness. Crit Care Explor. 2020; 2:e0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postelnicu R, Srivastava A, Bhatraju PK, et al. : Severe acute respiratory infection-preparedness: Protocol for a multicenter prospective cohort study of viral respiratory infections. Crit Care Explor. 2022; 4:e0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. ; ISARIC4C investigators: Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with Covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020; 369:m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh GK, Siahpush M: Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980-2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006; 35:969–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. : Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161:765–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lusk JB, Blass B, Mahoney H, et al. : Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, healthcare access, and 30-day mortality and readmission after sepsis or critical illness: Findings from a nationwide study. Crit Care. 2023; 27:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. : APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985; 13:818–829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salluh JI, Soares M: ICU severity of illness scores: APACHE, SAPS and MPM. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014; 20:557–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. : The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991; 100:1619–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. : A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newsome AS, Smith SE, Olney WJ, et al. : Multicenter validation of a novel medication-regimen complexity scoring tool. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020; 77:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azimi H, Johnson L, Loudermilk C, et al. : Medication Regimen Complexity (MRC-ICU) for in-hospital mortality prediction in COVID-19 patients. Hosp Pharm. 2023; 58:564–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balamuth F, Scott HF, Weiss SL, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) PED Screen and PECARN Registry Study Groups: Validation of the pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score and evaluation of third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock definitions in the pediatric emergency department. JAMA Pediatr. 2022; 176:672–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matics TJ, Sanchez-Pinto LN: Adaptation and validation of a pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score and evaluation of the Sepsis-3 definitions in critically ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017; 171:e172352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baloch SH, Shaikh I, Gowa MA, et al. : Comparison of pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment and pediatric risk of mortality III score as mortality prediction in pediatric intensive care unit. Cureus. 2022; 14:e21055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wynn JL, Mayampurath A, Carey K, et al. : Multicenter validation of the neonatal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for prognosis in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2021; 236:297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE: The Pediatric Risk of Mortality III-Acute Physiology Score (PRISM III-APS): A method of assessing physiologic instability for pediatric intensive care unit patients. J Pediatr. 1997; 131:575–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur A, Kaur G, Dhir SK, et al. : Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score—predictor of mortality and hospital stay in pediatric intensive care unit. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020; 13:146–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shann F, Pearson G, Slater A, et al. : Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM): A mortality prediction model for children in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1997; 23:201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G; Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) Study Group: PIM2: A revised version of the Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29:278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, et al. ; ANZICS Paediatric Study Group and the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network: Paediatric Index of Mortality 3: An updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013; 14:673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. : The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996; 22:707–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soo A, Zuege DJ, Fick GH, et al. : Describing organ dysfunction in the intensive care unit: A cohort study of 20,000 patients. Crit Care. 2019; 23:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashyap R, Sherani KM, Dutt T, et al. : Current utility of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score: A literature review and future directions. Open Respir Med J. 2021; 15:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandharipande PP, Shintani AK, Hagerman HE, et al. : Derivation and validation of Spo2/Fio2 ratio to impute for Pao2/Fio2 ratio in the respiratory component of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:1317–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez Bernaldo de Quiros F, Otero C, Luna D: Terminology services: Standard terminologies to control health vocabulary. Yearb Med Inform. 2018; 27:227–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gliklich RE, Leavy MB, Dreyer NA: Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Fourth Edition. Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Facile R, Muhlbradt EE, Gong M, et al. : Use of Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) standards for real-world data: Expert perspectives from a qualitative Delphi survey. JMIR Med Inform. 2022; 10:e30363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canham S, Ohmann C: A metadata schema for data objects in clinical research. Trials. 2016; 17:557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duda SN, Kennedy N, Conway D, et al. : HL7 FHIR-based tools and initiatives to support clinical research: A scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022; 29:1642–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.