Abstract

Background

The AEGIS-II (ApoA-I Event Reducing in Ischemic Syndromes-II; NCT03473223) trial evaluated CSL112, a human plasma-derived apolipoprotein A-I therapy, for reducing cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Given CSL112’s potential anti-inflammatory properties, we conducted an exploratory post hoc analysis to determine if its efficacy is influenced by baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a marker of systemic inflammation, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association of baseline NLR and cardiovascular events and explore whether NLR and LDL-C modify CSL112’s efficacy in post-AMI patients.

Methods

A total of 18,219 participants with AMI, multivessel coronary artery disease, and additional cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to 4 weekly infusions of 6 g CSL112 or placebo. The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE]). Cox proportional hazards models evaluated risk by dichotomized baseline NLR (>median vs ≤median). Treatment interactions with NLR and LDL-C (≥100 vs <100 mg/dL) were assessed.

Results

Among 15,966 participants, those with baseline NLR >median (>3.3) had a significantly greater risk of MACE at 90 days (HR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.21-1.63), persisting at 180 and 365 days. CSL112 reduced MACE at 90 days among participants with elevated NLR and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.42-0.93), with sustained benefits at 180 and 365 days. Significant interactions were observed between treatment and NLR (Pinteraction = 0.010) and among treatment, NLR, and LDL-C at 180 days (Pinteraction = 0.029).

Conclusions

Baseline elevated NLR predicts MACE in post-AMI patients, and CSL112 showed an associated reduction in MACE in patients with elevated NLR and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL.

Key words: apolipoprotein A-I, CSL112, inflammation, MACE, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

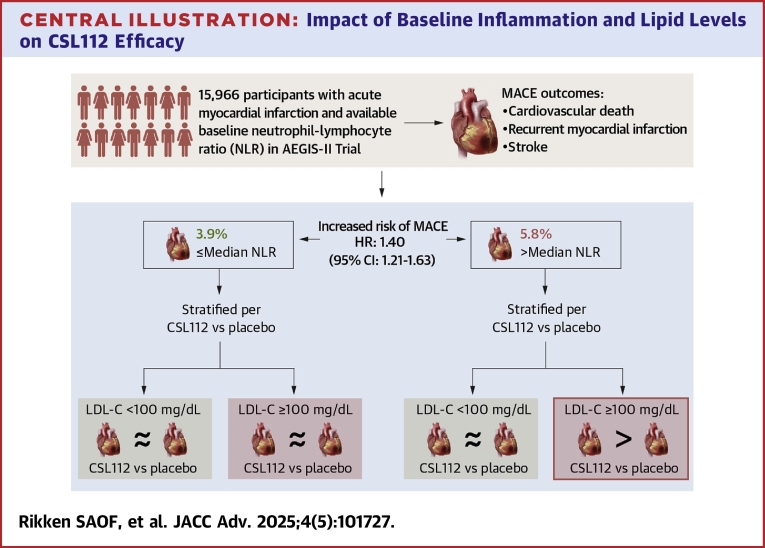

Central Illustration

Despite modern guideline-directed medical therapy, patients who survive an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remain at high risk for recurrent cardiovascular events, particularly in the first 90 days following the index event.1, 2, 3 Recurrent events link to persistent thrombin generation, residual inflammation, and elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, which together contribute to atherosclerotic plaque instability, thrombosis, and myocardial damage.4,5 Inflammation in the early post-AMI period, in part driven by neutrophils, promotes oxidative damage, endothelial dysfunction, and plaque rupture.6,7 In contrast, some lymphocytes, particularly regulatory T-cells, can mute inflammation and facilitate tissue repair.8

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which reflects the balance between pro-inflammatory and reparative processes, has emerged as an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Elevated NLR is associated with increased mortality and recurrent ischemic events following AMI.9 Given the interplay between systemic inflammation and lipid burden in driving recurrent events, targeting both pathways may be a promising therapeutic strategy. Recent evidence emphasizes the synergistic impact of impaired high-density lipoprotein (HDL) functionality, specifically cholesterol efflux capacity, and elevated interleukin-1β (IL)-1β in increasing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.10

Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), the primary structural protein of HDL, is essential for initiating reverse cholesterol transport; however, its function may be compromised post-AMI.11 CSL112, a human plasma-derived apoA-I infusion therapy, enhances cholesterol efflux capacity and has demonstrated potential in reducing neutrophil recruitment post-AMI.12, 13, 14, 15 In the AEGIS-II (ApoA-I Event Reducing in Ischemic Syndromes-II) trial, weekly administration of 6 g CSL112 for 4 weeks post-AMI did not result in a statistically significant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke at 90 days compared to placebo.16 Nonetheless, exploratory analyses suggested that participants with elevated baseline LDL-C (≥100 mg/dL) derived benefit from CSL112, with a reduction in MACE at 90, 180, and 365 days.17 However, this effect was absent in patients with baseline LDL-C <100 mg/dL, indicating potentially greater efficacy in those with a higher lipid burden.17

Given the dual roles of systemic inflammation and elevated LDL-C in driving recurrent cardiovascular events, this study aimed to assess the association between baseline NLR and cardiovascular outcomes, as well as to investigate whether CSL112 efficacy is modulated by the interaction between elevated NLR and LDL-C levels in post-AMI patients.

Methods

Study design and patients

The AEGIS-II trial design and primary outcomes have been reported.16,18 Eligible adults (≥18 years of age) with type 1 MI, multivessel coronary disease, and at least 2 additional cardiovascular risk factors (eg, age ≥65 years, prior MI, diabetes, or peripheral artery disease) were included. Key exclusion criteria comprised significant hepatobiliary disease, hemodynamic instability, left ventricular ejection fraction <30%, estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, or planned postrandomization coronary bypass surgery.

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to CSL112 (6 g) or placebo, with 4 weekly intravenous infusions administered within 30 days of randomization. Follow-up visits occurred on days 29, 60, and 90, and then every 90 days until day 365. The primary endpoint was time to the first occurrence of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (MACE) through 90 days, and secondary outcomes including MACE assessment at 180 and 365 days. All events were adjudicated by an independent clinical events committee blinded to treatment. The study complied with regulatory and ethics board standards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

The present analysis evaluated: 1) the association between baseline NLR and MACE, defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke; and 2) the effect of CSL112 in reducing MACE by baseline NLR and LDL-C levels.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median (Q1-Q3), and categorical variables as count (%). Normality was assessed using visual inspection of histograms and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Efficacy analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat population. Baseline NLR was calculated as the ratio of absolute neutrophil to lymphocyte counts on the day of randomization, prior to the administration of the study drug, to reflect pretreatment inflammatory status. Participants without available NLR data were excluded. A histogram of baseline NLR was generated to illustrate its distribution and provide context for subgroup analyses. Associations between continuous NLR, NLR quartiles, and >median NLR values with MACE were analyzed using Cox proportional-hazards models, and cumulative incidence rates for MACE were estimated for NLR quartiles and dichotomized NLR (>median vs ≤median) at 90, 180, and 365 days.

For the primary analysis, NLR was dichotomized at the median (>median vs ≤median), and Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate causal-specific HRs with 95% CIs for MACE. Prespecified covariates included treatment assignment, geographic region, index AMI type, MI management, age, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, history of MI, and an interaction term for index AMI type and index AMI management. A sensitivity analysis accounting for baseline differences between >median NLR vs ≤median NLR was also performed.

To assess whether the efficacy of CSL112 was modified by NLR levels, treatment-by-NLR interaction terms were included in the models. NLR was also analyzed as a continuous variable using restricted cubic spline models, with knots set at the 20th, 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles. Additionally, NLR quartiles were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models to estimate HRs for CSL112 vs placebo within each quartile.

A secondary stratified analysis (n = 15,250) evaluated the impact of LDL-C on CSL112 efficacy, using an LDL-C threshold of 100 mg/dL. Interaction terms between treatment, NLR, and LDL-C were included to explore effect modification in participants by NLR status (>median vs ≤median) and LDL-C levels (≥100 mg/dL vs <100 mg/dL), adjusting for all covariates used in the primary analysis. Two-sided P values were reported, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

In this study, we analyzed time-to-event outcomes using the Cox model, as prespecified in our Statistical Analysis Plan. While the Fine-Gray model is commonly employed for competing risk analyses to estimate the subdistribution hazard and cumulative incidence function, our primary objective was to evaluate the cause-specific hazard of the event of interest. The Cox proportional hazards model was chosen to assess the treatment effect on the occurrence of the event while accounting for censoring and competing events as noninformative censoring. Consistent with the cause-specific hazard framework employed in the Cox model, Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to describe the time-to-event patterns for the outcome of interest. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining plots of the log(-log[survival]) vs log(time) for the treatment effect. The assumption was considered satisfied if the curves were approximately parallel and did not cross, indicating consistent HRs over time.

The analyses presented here were post hoc, exploratory in nature, and aimed at hypothesis generation; therefore, no adjustments were made for multiplicity. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Overview

Between March 2018 and November 2022, a total of 18,219 participants at 886 sites in 49 countries were randomized and included in the intention-to-treat analysis. A total of 9,112 participants were randomized to CSL112 and 9,107 to placebo.16 The majority of participants completed all 4 infusions of the study drug (89.8% in the CSL112 group and 90.0% in the placebo group). The ascertainment of the primary endpoint was complete for 99.4% of potential participant-years of follow-up, with vital status confirmed for 99.5% of participants. Only one participant in each treatment group was lost to follow-up.

After excluding participants without data on absolute neutrophil count or absolute lymphocyte count, 15,966 participants (87.6%) were included in the primary analysis (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the 2 groups (>median vs ≤median). The median age of participants was 67.0 years (Q1-Q3: 59.0-72.0 years), and 74.4% (11,886 participants) were male. The NLR was non-normally distributed at baseline, and the median value was 3.3 (Q1-Q3: 2.5–4.4) (Supplemental Figure 1), which was similar between participants randomized to CSL112 and those randomized to placebo (3.2 [Q1-Q3: 2.4-4.4] vs 3.3 [Q1-Q3: 2.5-4.4], P = 0.95). Participants with baseline NLR >median were more likely to be older, male, not current smokers, presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, with baseline lower triglycerides and LDL-C levels (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Study Populations

This flowchart depicts the selection process of the study population. LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein; NLR = neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients at Randomization

| NLR >Median |

NLR ≤Median |

P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 7,983) |

CSL112 6 g (n = 3,967) |

Placebo (n = 4,016) |

Total (N = 7,983) |

CSL112 6 g (n = 3,994) |

Placebo (n = 3,989) | ||

| Age, y | 68.0 (61.0-74.0) | 68.0 (61.0-74.0) | 68.0 (61.0-74.0) | 65.0 (57.0-71.0) | 65.0 (58.0-71.0) | 68.0 (61.0-74.0) | <0.001 |

| Age ≥65 y | 5,232 (65.5%) | 2,605 (65.7%) | 2,627 (65.4%) | 4,227 (53.0%) | 2,133 (53.4%) | 2,627 (65.4%) | <0.001 |

| Male | 6,178 (77.4%) | 3,095 (78.0%) | 3,083 (76.8%) | 5,708 (71.5%) | 2,876 (72.0%) | 3,083 (76.8%) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||

| White | 6,854 (85.9%) | 3,440 (86.7%) | 3,414 (85.0%) | 6,767 (84.8%) | 3,384 (84.7%) | 3,414 (85.0%) | |

| Asian | 677 (8.5%) | 312 (7.9%) | 365 (9.1%) | 714 (8.9%) | 366 (9.2%) | 365 (9.1%) | |

| Black/African American | 105 (1.3%) | 51 (1.3%) | 54 (1.3%) | 183 (2.3%) | 88 (2.2%) | 54 (1.3%) | |

| Other/multiracial | 308 (3.9%) | 143 (3.6%) | 165 (4.1%) | 287 (3.6%) | 139 (3.5%) | 165 (4.1%) | |

| Missing | 39 (0.5%) | 21 (0.5%) | 18 (0.4%) | 32 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) | 18 (0.4%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.52 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1,044 (13.1%) | 504 (12.7%) | 540 (13.4%) | 1,107 (13.9%) | 540 (13.5%) | 540 (13.4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 6,833 (85.6%) | 3,406 (85.9%) | 3,427 (85.3%) | 6,770 (84.8%) | 3,400 (85.1%) | 3,427 (85.3%) | |

| Not reported | 102 (1.3%) | 55 (1.4%) | 47 (1.2%) | 103 (1.3%) | 54 (1.4%) | 47 (1.2%) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | 2 (0.0%) | 3 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | |

| Geographic region | <0.001 | ||||||

| Central and Eastern Europe | 2,561 (32.1%) | 1,304 (32.9%) | 1,257 (31.3%) | 3,293 (41.3%) | 1,610 (40.3%) | 1,257 (31.3%) | |

| Western Europe | 2,426 (30.4%) | 1,198 (30.2%) | 1,228 (30.6%) | 2,013 (25.2%) | 1,033 (25.9%) | 1,228 (30.6%) | |

| Latin America | 898 (11.2%) | 447 (11.3%) | 451 (11.2%) | 983 (12.3%) | 479 (12.0%) | 451 (11.2%) | |

| Asia Pacific | 829 (10.4%) | 399 (10.1%) | 430 (10.7%) | 810 (10.1%) | 418 (10.5%) | 430 (10.7%) | |

| North America | 1,269 (15.9%) | 619 (15.6%) | 650 (16.2%) | 884 (11.1%) | 454 (11.4%) | 650 (16.2%) | |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2) | 28.1 (25.3-31.5) | 28.3 (25.4-31.6) | 28.1 (25.3-31.5) | 28.5 (25.7-32.0) | 28.7 (25.7-31.9) | 28.1 (25.3-31.5) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 1,809 (22.7%) | 882 (22.2%) | 927 (23.1%) | 2,385 (29.9%) | 1,187 (29.7%) | 927 (23.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5,318 (66.6%) | 2,664 (67.2%) | 2,654 (66.1%) | 5,531 (69.3%) | 2,761 (69.1%) | 2,654 (66.1%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1,025 (12.8%) | 484 (12.2%) | 541 (13.5%) | 1,002 (12.6%) | 515 (12.9%) | 541 (13.5%) | 0.58 |

| Prior MI | 2,831 (35.5%) | 1,386 (34.9%) | 1,445 (36.0%) | 3,014 (37.8%) | 1,555 (38.9%) | 1,445 (36.0%) | <0.003 |

| Prior PCI | 3,026 (37.9%) | 1,504 (37.9%) | 1,522 (37.9%) | 3,092 (38.7%) | 1,587 (39.7%) | 1,522 (37.9%) | <0.28 |

| Heart failure | 772 (9.7%) | 387 (9.8%) | 385 (9.6%) | 860 (10.8%) | 396 (9.9%) | 385 (9.6%) | 0.022 |

| Ischemic stroke | 450 (5.6%) | 210 (5.3%) | 240 (6.0%) | 385 (4.8%) | 190 (4.8%) | 240 (6.0%) | 0.021 |

| Hypertension | 6,348 (79.5%) | 3,172 (80.0%) | 3,176 (79.1%) | 6,305 (79.0%) | 3,166 (79.3%) | 3,176 (79.1%) | 0.40 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 5,115 (64.1%) | 2,521 (63.5%) | 2,594 (64.6%) | 5,169 (64.8%) | 2,647 (66.3%) | 2,594 (64.6%) | 0.37 |

| Index MI type: STEMI | 4,164 (52.2%) | 2,038 (51.4%) | 2,126 (52.9%) | 3,950 (49.5%) | 1,981 (49.6%) | 2,126 (52.9%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiography for index MI | 7,846 (98.3%) | 3,896 (98.2%) | 3,950 (98.4%) | 7,698 (96.4%) | 3,846 (96.3%) | 3,950 (98.4%) | <0.001 |

| PCI for index MI | 7,214 (90.4%) | 3,593 (90.6%) | 3,621 (90.2%) | 6,909 (86.5%) | 3,450 (86.4%) | 3,621 (90.2%) | <0.001 |

| Staged PCI for index MI | 1,230 (15.4%) | 590 (14.9%) | 640 (15.9%) | 1,133 (14.2%) | 587 (14.7%) | 640 (15.9%) | 0.031 |

| Aspirin at randomization | 7,428 (93.0%) | 3,698 (93.2%) | 3,730 (92.9%) | 7,443 (93.2%) | 3,725 (93.3%) | 3,718 (93.2%) | 0.64 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor at randomization | 7,473 (93.6%) | 3,700 (93.3%) | 3,773 (93.9%) | 7,483 (93.7%) | 3,755 (94.0%) | 3,728 (93.5%) | 0.75 |

| High-intensity statin at randomization | 6,064 (76.0%) | 3,017 (76.1%) | 3,047 (75.9%) | 6,156 (77.1%) | 3,062 (76.7%) | 3,094 (77.6%) | 0.085 |

| Nonstatin lipid-lowering drugs at randomization | 986 (12.4%) | 480 (12.1%) | 506 (12.6%) | 973 (12.2%) | 496 (12.4%) | 477 (12.0%) | 0.75 |

| Total cholesterol at baseline (mg/dL) | 154.7 (129.2-186.0) | 155.1 (129.5-186.0) | 154.7 (129.2-185.6) | 164.0 (137.3-195.7) | 164.2 (136.5-195.7) | 164.0 (138.1-196.1) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol at baseline (mg/dL) | 80.8 (59.2-107.9) | 80.8 (59.2-107.9) | 80.8 (59.2-107.5) | 86.6 (64.6-114.1) | 85.8 (64.2-114.1) | 87.0 (65.0-114.1) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol at baseline (mg/dL) | 39.8 (34.0-47.2) | 39.8 (33.6-47.2) | 40.2 (34.0-47.6) | 39.1 (33.3-46.4) | 39.1 (32.9-46.0) | 39.1 (33.3-46.4) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides at baseline (mg/dL) | 145.3 (110.7-194.9) | 146.1 (110.7-196.6) | 143.5 (110.7-193.1) | 163.0 (124.0-225.0) | 163.9 (124.0-225.9) | 162.1 (124.0-224.1) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio at baseline (mg/dL) | 4.4 (3.7-5.6) | 4.4 (3.7-5.6) | 4.4 (3.7-5.6) | 2.5 (2.0-2.8) | 2.5 (2.0-2.9) | 2.5 (2.0-2.8) | <0.001 |

Values are median (Q1-Q3) or n (%). The P value is based on Wilcoxon rank sum nonparametric or chi-squared test for the comparison between total columns for NLR ≤median compared with NLR >median. To convert the values for HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586. To convert the values for triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129.

HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; MI = myocardial infarction; NLR = neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; Q1-Q3 = 25th-75th percentiles; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Association of NLR with mace

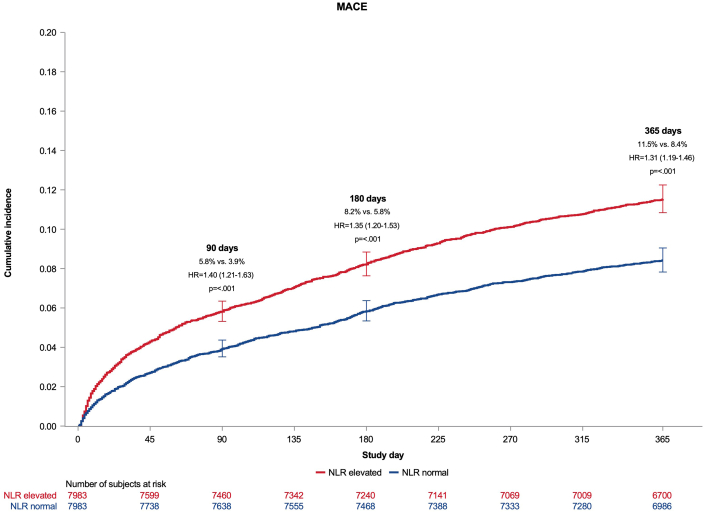

At 90 days, participants with baseline NLR >median were at higher risk for MACE compared to those with NLR ≤ median (HR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.21-1.63; P < 0.001, Figure 2). This increased risk remained significant at 180 days (HR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.20-1.53; P < 0.001) and at 365 days (HR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.19-1.46; P < 0.001). A sensitivity analysis adjusting for all baseline differences between the >median and ≤median groups yielded results consistent with the prespecified covariate-adjusted analysis: HR: 1.41 (95% CI: 1.22-1.63; P < 0.001) at 90 days; HR: 1.36 (95% CI: 1.20-1.53; P < 0.001) at 180 days; and HR: 1.32 (95% CI: 1.20-1.47) at 365 days.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events by Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

Cumulative incidence of the time to first occurrence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (MACE) through 90, 180, and 365 days among patients with a higher NLR (>median) vs lower (≤median) at baseline. MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; other abbreviation as in Figure 1.

When NLR was evaluated per quartile, the cumulative incidence of MACE increased across NLR quartiles (Supplemental Figure 2). The HR for MACE in the 4th quartile vs the 1st quartile was 1.8 (95% CI: 1.50-2.25; P < 0.001) at 90 days (Supplemental Table 1). At 180 days, the HR for the highest vs lowest quartile was 1.73 (95% CI: 1.46-2.05; P < 0.001), and at 365 days, it was 1.58 (95% CI: 1.38-1.83; P < 0.001).

Continuous analysis revealed that a per-unit increase in NLR was associated with a 7.3% higher risk of MACE at 90 days (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.04-1.10; P < 0.001), a 6.6% higher risk at 180 days (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.04-1.09; P < 0.001), and a 6.6% higher risk at 365 days (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.05-1.09; P < 0.001).

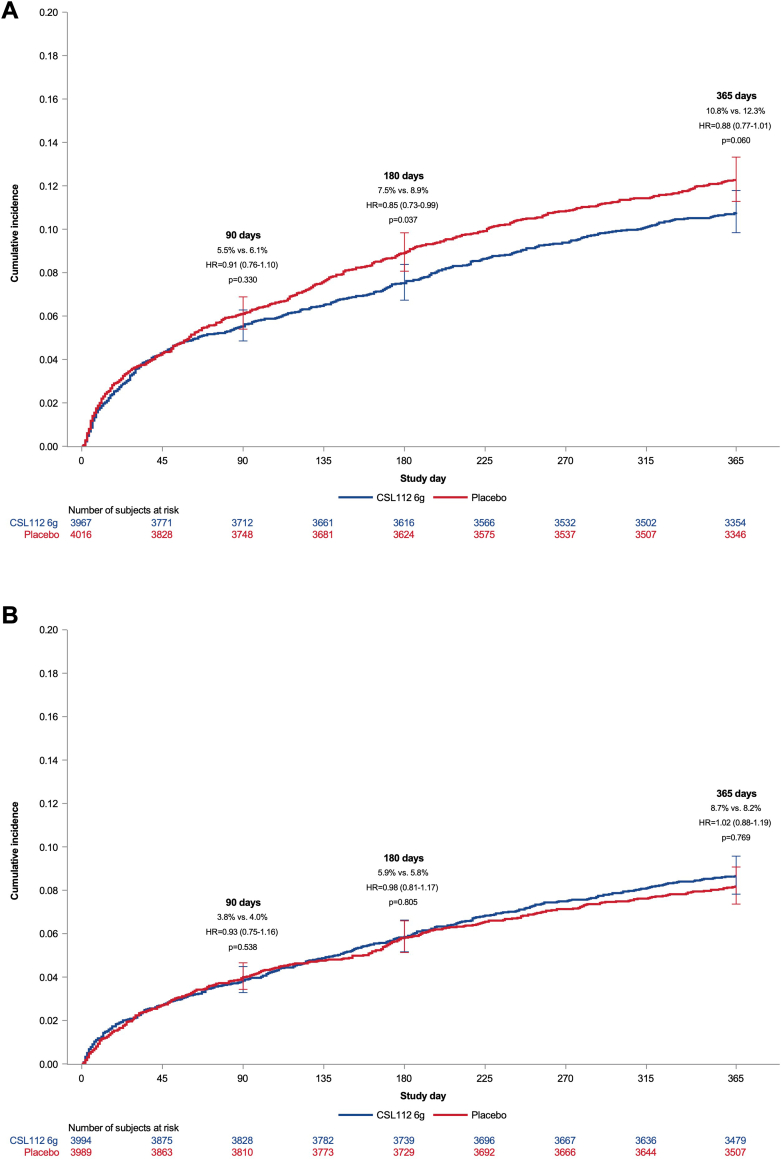

Effect of CSL112 on mace by NLR subgroups

Among participants with NLR > median, CSL112 did not show a reduction in MACE at 90 days compared to placebo (HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.76-1.10; P = 0.33) (Figure 3). However, at 180 days, CSL112 treatment resulted in a statistically significant reduction in MACE compared to placebo (HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.73-0.99; P = 0.037) (Table 2), driven primarily by a reduction in MIs. By 365 days, the incidence of MACE in the CSL112 group was lower compared to placebo, though the difference was not statistically significant (HR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.77-1.01; P = 0.060). No significant treatment effect of CSL112 was observed at any time point in participants with NLR values ≤ median. The P values for treatment-by-NLR interaction were 0.19 at 90 days, 0.010 at 180 days, and 0.060 at 365 days.

Figure 3.

Cumulative Incidence of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events by Treatment and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

Cumulative incidence of the time to first occurrence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (MACE) through 90, 180, and 365 days among patients with (A) (>median NLR) for CSL112 vs placebo and (B) (≤median NLR) treated for CSL112 vs placebo. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events by NLR Subgroup

| Endpoint | Time Point | NLR ≤Median (N = 7,983) |

NLR >Median (N = 7,983) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSL112 6 g (n = 3,994) |

Placebo (n = 3,989) |

HR (95% CI) | P Value | CSL112 6 g (n = 3,967) |

Placebo (n = 4,016) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Composite of MI, stroke, or CV death | Through 90 d | 153 | 159 | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) | 0.54 | 218 | 244 | 0.91 (0.76-1.10) | 0.33 |

| Through 180 d | 233 | 231 | 0.98 (0.81-1.17) | 0.81 | 296 | 356 | 0.85 (0.73-0.99) | 0.037 | |

| Through 365 d | 344 | 324 | 1.02 (0.88-1.19) | 0.77 | 423 | 489 | 0.88 (0.77-1.01) | 0.060 | |

| CV death or MI | Through 90 d | 138 | 146 | 0.91 (0.72-1.15) | 0.45 | 201 | 221 | 0.93 (0.77-1.13) | 0.46 |

| Through 180 d | 208 | 209 | 0.96 (0.79-1.17) | 0.69 | 272 | 327 | 0.85 (0.72-1.00) | 0.047 | |

| Through 365 d | 311 | 292 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | 0.77 | 386 | 453 | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) | 0.043 | |

| CV death | Through 90 d | 18 | 32 | 0.55 (0.31-0.98) | 0.043 | 69 | 73 | 0.96 (0.69-1.33) | 0.79 |

| Through 180 d | 38 | 44 | 0.83 (0.54-1.28) | 0.40 | 88 | 95 | 0.94 (0.70-1.25) | 0.66 | |

| Through 365 d | 66 | 70 | 0.89 (0.64-1.25) | 0.51 | 127 | 134 | 0.96 (0.76-1.23) | 0.76 | |

| MI | Through 90 d | 124 | 125 | 0.96 (0.75-1.23) | 0.74 | 148 | 170 | 0.89 (0.72-1.12) | 0.32 |

| Through 180 d | 182 | 178 | 0.99 (0.80-1.22) | 0.91 | 208 | 264 | 0.81 (0.67-0.97) | 0.022 | |

| Through 365 d | 265 | 245 | 1.04 (0.87-1.24) | 0.65 | 300 | 362 | 0.85 (0.73-0.99) | 0.035 | |

| Stroke | Through 90 d | 17 | 14 | 1.18 (0.58-2.39) | 0.65 | 25 | 29 | 0.88 (0.52-1.51) | 0.65 |

| Through 180 d | 30 | 25 | 1.16 (0.68-1.97) | 0.59 | 34 | 39 | 0.90 (0.57-1.42) | 0.64 | |

| Through 365 d | 42 | 41 | 0.98 (0.64-1.51) | 0.92 | 50 | 56 | 0.92 (0.63-1.35) | 0.67 | |

Event counts for major adverse cardiovascular events are presented for each subgroup.

CV = cardiovascular; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Quartile analysis showed no significant treatment effect of CSL112 on MACE across any NLR quartile (Supplemental Figure 3). Similarly, restricted cubic spline analysis demonstrated no statistically significant effect of CSL112 on MACE at 90 or 365 days across the NLR spectrum (Supplemental Figure 4). At 180 days, a potential benefit of CSL112 in patients with higher NLR values was observed but the HR was not statistically significant.

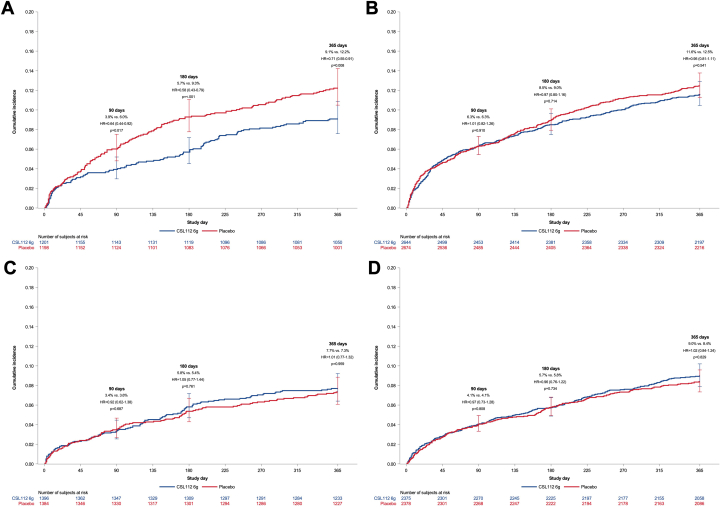

CSL112 efficacy by combined NLR and LDL-C subgroups

In participants with both NLR >median and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL (n = 15,250), CSL112 treatment was associated with a reduced MACE incidence at all follow-up time points: 90 days (HR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.44-0.92; P = 0.017), 180 days (HR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.42-0.80; P < 0.001), and 365 days (HR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.53-0.91; P = 0.008) (Figure 4). Conversely, CSL112 showed no significant differences in MACE rates among participants with either NLR >median with LDL-C <100 mg/dL, nor any difference in those with NLR ≤median regardless of LDL-C levels. The P values for the three-way interaction of treatment, NLR, and LDL-C, at the 3 follow-up time points (90, 180, and 365 days) were 0.21, 0.029, and 0.21, respectively.

Figure 4.

Cumulative Incidence of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events by Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

Cumulative incidence of the time to first occurrence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (MACE) through 90, 180, and 365 days among patients with (A) a higher NLR (>median) and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL at baseline and (B) higher NLR (>median) and LDL-C <100 mg/dL and (C) a lower NLR (≤median) and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL at baseline and (D) lower NLR (≤median) and LDL-C <100 mg/dL. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Safety outcomes

Adverse event rates were comparable between CSL112 and placebo groups across all NLR subgroups, and no new safety concerns were identified in this analysis.

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of the AEGIS-II trial underscores the prognostic significance of baseline NLR in patients with acute MI, with elevated NLR (>median) predicting a higher incidence of MACE at 90, 180, and 365 days post-AMI. Second, our findings suggest that, while CSL112 did not significantly reduce MACE in the overall AEGIS-II population, a potential reduction in MACE at 180 days was observed in participants with elevated NLR, highlighting the possibility for CSL112 as a time-sensitive therapeutic intervention for this high-risk subgroup. Notably, patients with both elevated NLR and LDL-C (≥100 mg/dL) demonstrated consistent reductions in MACE at 90, 180, and 365 days, suggesting that the combined presence of systemic inflammation and elevated lipid burden may identify a subgroup of patients likely to benefit from CSL112 therapy.

The association between elevated NLR and MACE aligns with current evidence implicating inflammation in post-AMI cardiovascular events.9,19 Elevated NLR reflects a state of heightened neutrophil-mediated inflammation, which can augment local oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and plaque instability, all of which contribute to recurrent ischemic events.6,7 Conversely, lymphocytes—particularly regulatory and T helper 2 T-cells—can facilitate the resolution of inflammation, promoting tissue repair post-MI.8 Therefore, an elevated NLR suggests a disproportionate inflammatory response, which could be an important mediator of recurrent cardiovascular events. Moreover, elevated LDL-C contributes to plaque vulnerability and activates lipid-driven inflammatory pathways, which, when combined with an elevated NLR, results in a particularly high-risk profile.

Our observation that CSL112 was most effective in participants with both elevated NLR and elevated LDL-C provides mechanistic insights into its dual action on inflammation and cholesterol metabolism. Recent research has highlighted how HDL functionality, particularly cholesterol efflux capacity, influences residual cardiovascular risk post-MI. Patients with both low cholesterol efflux capacity and elevated IL-1β levels are at increased risk for recurrent events, underscoring a high-risk profile characterized by HDL dysfunction and systemic inflammation.10 Given that CSL112 enhances cholesterol efflux, the observed benefit among patients with elevated NLR and LDL-C in our cohort may reflect similar underlying HDL dysfunction, reinforcing CSL112’s role in patients with high inflammatory and lipid burden.

CSL112 may attenuate neutrophil-driven inflammation by reducing cholesterol content within atherosclerotic plaques and modulating lipid-driven inflammatory pathways.20 Enhanced cholesterol efflux can inhibit neutrophil migration and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell proliferation, thereby potentially mitigating inflammation.21 Importantly, in a phase 2 study, CSL112 has been shown to attenuate the post-AMI elevation in NLR.21 This effect was driven primarily by a decrease in neutrophil counts, supporting the hypothesis that CSL112 mitigates neutrophil-driven inflammation.12 Early reductions in neutrophil counts may reflect a tempered acute inflammatory response, and hence more quiescent vulnerable plaques during the critical post-AMI period. Furthermore, in vitro studies demonstrated the ability of CSL112 particles to reduce acute inflammation in macrophages by inhibiting IL-1ß secretion.10

Our findings align with prior research demonstrating the interplay between inflammation and lipid levels in cardiovascular outcomes,22 emphasizing that combined biomarkers such as LDL-C and NLR may better identify high-risk patients. While therapies like canakinumab targeting the IL-1β innate immunity pathway showed benefits in reducing cardiovascular events independent of lipid levels, CSL112 primarily exerts its effects through enhanced cholesterol efflux.13,16,23 The observed benefit in patients with both elevated LDL-C and NLR suggests CSL112's potential as a targeted therapy for those with combined lipid and inflammatory risk, distinct from inflammation-focused interventions.

This analysis has several limitations. First, as a post hoc analysis, these findings should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating. The lack of randomization by NLR or LDL-C subgroup limits causal inferences, and further prospective studies are needed to validate these observations. Second, the absence of serial NLR measurements limits our understanding of the dynamic nature of inflammation in response to CSL112 treatment. Serial monitoring of NLR could provide deeper insights into the temporal relationship between inflammation resolution and cardiovascular risk reduction. Nevertheless, baseline NLR remains a well-validated and practical marker of inflammation, consistently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes.9 Third, while we focused on NLR and LDL-C, other important biomarkers reflective of systemic inflammation (eg, IL-1β, IL-6, C-reactive protein) were not assessed in this trial.24,25 Of note, a recent publication analyzing >2,000 AMI patients submitted to primary PCI and followed for 1-year post-AMI found a significant and independent association between IL-1β and MACE, which was not observed for high-sensitive C-reactive protein.10 Lastly, this study used Kaplan-Meier estimates to illustrate time-to-event patterns; however, these estimates do not account for the influence of competing risks, such as all-cause mortality. While this approach aligns with our cause-specific hazard analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model, it may overestimate the cumulative incidence of the event of interest. The Fine-Gray method, which models the subdistribution hazard, could have provided more direct insights into the cumulative incidence of the event in the presence of competing risks. Future studies may consider incorporating the Fine-Gray approach to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of competing risks on event occurrence.

Conclusions

This post hoc analysis reinforces baseline NLR as a prognostic marker readily accessible from routine clinical testing in AMI patients, with elevated NLR associated with increased MACE risk across 90, 180, and 365 days. CSL112 showed MACE reduction at 180 days in post-MI patients with baseline elevated NLR and demonstrated reduced cardiovascular events at all time points among those with both elevated NLR and LDL-C levels (Central Illustration). These results suggest that post-AMI patients with heightened inflammatory and lipid risk may benefit most from CSL112, warranting further prospective studies to validate these findings.

Central Illustration.

Impact of Baseline Inflammation and Lipid Levels on CSL112 Efficacy

MACE incidence by baseline NLR (>median vs ≤median) in AEGIS-II trial. The figure shows that increased baseline NLR predicts MACE in post-AMI patients and that CSL112 may reduce MACE in patients with high NLR and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL, but not other subgroups. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Funding support and author disclosures

This study was funded by CSL Behring. Dr Rikken has received speaking honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Gibson has received research funding from CSL Behring, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Corporation, and SCAD Alliance; has provided consulting services for Angel/Avertix Medical Corporation, AstraZeneca, Bayer Corporation, Beren Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Clinical Research Institute, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, CeleCor Therapeutics, CSL Behring, DCRI, Esperion, EXCITE International (for which no compensation was received), Fortress Biotech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, MashUp MD, MD Magazine, Microport, MJHealth, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, PHRI, PLxPharma, SCAI, Solstice Health/New Amsterdam Pharma, Somahlution/Marizyme, Vectura, WebMD, and Women as One; holds equity in nference, Dyad Medical, Absolutys, and Fortress Biotech; and has received royalties as a contributor to UpToDate. Dr Bahit has received modest honorarium from MSD, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Anthos Therapeutics. Dr Duffy is an employee of CSL Behring. Dr Chi has received research grant support paid to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School from Bayer, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and CSL Behring. Dr Korjian has received research grant support paid to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School from CSL Behring. Dr White has received grant support to institution from Sanofi, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Omthera Pharmaceuticals, American Regent, Eisai Inc, DalCor Pharma UK Inc, CSL Behring, NHI, Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd, Esperion Therapeutics Inc, and National Institutes of Health; has received fees for serving on Steering Committees of the ODYSSEY trial from Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, the ISCHEMIA and the MINT studies from the National Institutes of Health, the STRENGTH trial from Omthera Pharmaceuticals, the HEART-FID study from American Regent, the DAL-GENE study from DalCor Pharma UK Inc, the AEGIS-II study from CSL Behring, the SCORED trial and the SOLOIST-WHF trial from Sanofi Australia Pty Ltd, and the CLEAR OUTCOMES study from Esperion Therapeutics. Dr Anschuetz has received a salary as an employee of CSL Behring. Dr Kingwell is an employee and shareholder of CSL Ltd. Dr Nicolau has received a scholarship from the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) #303448/2021-0; has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Dalcor, Esperion, Ionis, Janssen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Vifor; and has received consulting fees from Libbs. Dr Lopes has received grant support from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi; has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk; and has participated in educational activities for Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. Dr Lewis has received consulting fees from Janssen R&D and Idorsia. Dr Vinereanu has received research grants from CSL Behring, Bayer, Novartis, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Novartis, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr ten Berg has received institutional research grants from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, and ZonMw and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CeleCor Therapeutics, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Goodman has received research grant support (eg, steering committee or data and safety monitoring committee) and/or speaker/consulting honoraria (eg, advisory boards) from Alnylam, Amgen, Anthos Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, CYTE Ltd, Daiichi Sankyo/American Regent, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, JAMP Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk A/C, Pendopharm/Pharmascience, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Tolmar Pharmaceuticals, Valeo Pharma; has received salary support/honoraria from the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Canadian Heart Research Centre and MD Primer, Canadian VIGOUR Centre, Cleveland Clinic Coordinating Centre for Clinical Research, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Jewish General Hospital\CIUSSS Centre-Ouest-de-l'Ile-de-Montreal, New York University Clinical Coordinating Centre, PERFUSE Research Institute, Peter Munk Cardiac Centre Clinical Trials and Translation Unit, Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research, and TIMI Study Group (Brigham Health). Dr Bode has received research support from CSL Behring. Dr Steg has received research grants from Amarin and Sano; has served on clinical trials (steering committee, clinical events committee, data and safety monitoring board [DSMB]) for Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Idorsia, Janssen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sano; has served as a consultant or speaker for Amarin, Amgen, BMS, and Novo Nordisk; and is Senior Associate Editor at Circulation. Dr Libby has served on a scientific advisory board for Amgen, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Caristo, CSL Behring, DalCor, Dewpoint, Euclid Bioimaging, Xbiotech, Olatec, Medimmune, PlaqueTec, Polygon Therapeutics, TenSixteen Bio, and Soley Therapeutics; and has been a consultant for Amgen, Baim Institute Beren, Esperion, Genentech, Kancera, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Sanofi-Regeneron. Dr Bainey has received research support from CSL Behring. Dr van ‘t Hof received a consultancy fee from CeleCor as well as unrestricted grants from Boehringer and Abbott Vascular. Dr Ridker has received institutional research grant support from Kowa, Novartis, Amarin, Pfizer, Esperion, Novo Nordisk, and the NHLBI; has served as a consultant to numerous companies including Novartis, Flame, Agepha, Ardelyx, Arrowhead, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Janssen, Civi Biopharm, GlaxoSmithKline, SOCAR, Novo Nordisk, Health Outlook, Montai Health, Eli Lilly, New Amsterdam, Boehringer Ingelheim, RTI, Zomagen, Cytokinetics, Horizon Therapeutics, and Cardio Therapeutics; holds minority shareholder equity positions in Uppton, Bitteroot Bio, and Angiowave; and has received compensation for service on the Peter Munk Advisory Board (University of Toronto), the Leducq Foundation (Paris, FR), and the Baim Institute (Boston, Massachusetts). Dr Mahaffey has received grants from AHA, Apple Inc, Bayer, California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, CSL Behring, Eidos, Ferring, Gilead, Google (Verily), Idorsia, Johnson & Johnson, Luitpold, Novartis, PAC-12, Precordior, Sanifit; has received consulting fees from applied Therapeutics, Bayer, BMS, BridgeBio, CSL Behring, Elsevier, Fosun Pharma, Human, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, Myokardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Phasebio, Portola, Quidel, and Theravance; has received payment or honoraria from CSL Behring; and has stock or stock options in Human, Medeloop, Precordior, and Regencor. Dr Nicholls has received research support from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Anthera, CSL Behring, Cerenis, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Resverlogix, Novartis, InfraReDx, and Sanofi-Regeneron; and has been a consultant for Amgen, Akcea, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Kowa, Merck, Takeda, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Novo Nordisk, CSL Sequiris, and Vaxxinity. Dr Mehran has received institutional research payments from Abbott, Affluent Medical, Alleviant Medical, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BAIM, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, CardiaWave, CERC, Chiesi, Concept Medical, Daiichi Sankyo, Duke, Faraday, Idorsia, Janssen, MedAlliance, Medscape, Mediasphere, Medtelligence, Medtronic, Novartis, OrbusNeich, Pi-Cardia, Protembis, RM Global Bioaccess Fund Management, and Sanofi; has received personal fees from Affluent Medical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi USA, Cordis, Daiichi Sankyo, Esperion Science/Innovative Biopharma, Gaffney Events, Educational Trust, Global Clinical Trial Partners, Ltd, IQVIA, Medscape/WebMD Global, Novo Nordisk, PeerView Institute for Medical Education, TERUMO Europe N.V., and Radcliffe; has held equity <1% in Elixir Medical, Stel, ControlRad (spouse); has received an honorarium from AMA; is associate editor of JAMA Cardiology; and is a BOT Member, SC Member CTR Program of ACC. Dr Harrington has research relationships with Baim Institute, CSL, Janssen, NHLBI, PCORI, and DCRI; has consulting relationships with Atropos Health, Bitterroot Bio, BMS, BridgeBio, Element Science, Edwards Lifesciences, Foresite Labs, and Medscape/WebMD; and serves on boards of directors for the American Heart Association, College of the Holy Cross, and Cytokinetics. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For a supplemental table and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Steen D.L., Khan I., Andrade K., Koumas A., Giugliano R.P. Event rates and risk factors for recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality in a contemporary post acute coronary syndrome population representing 239 234 patients during 2005 to 2018 in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(9) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawton J.S., Tamis-Holland J.E., Bangalore S., et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne R.A., Rossello X., Coughlan J.J., et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(38):3720–3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libby P., Ridker P.M., Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahit M.C., Gibson C.M. Thrombin as target for prevention of recurrent events after acute coronary syndromes. Thromb Res. 2024;235:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2024.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puhl S.-L., Steffens S. Neutrophils in post-myocardial infarction inflammation: damage vs. Resolution? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:25. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matter M.A., Paneni F., Libby P., et al. Inflammation in acute myocardial infarction: the good, the bad and the ugly. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(2):89–103. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weirather J., Hofmann U.D.W., Beyersdorf N., et al. Foxp3 + CD4 + T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circ Res. 2014;115(1):55–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamstein N.H., MacFadyen J.G., Rose L.M., et al. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and incident atherosclerotic events: analyses from five contemporary randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(9):896–903. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silvain J., Materne C., Zeitouni M., et al. Defective biological activities of high-density lipoprotein identify patients at highest risk of recurrent cardiovascular event. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024 doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soares A.A.S., Tavoni T.M., de Faria E.C., Remalay A.T., Maranhão R.C., Sposito A.C. HDL acceptor capacities for cholesterol efflux from macrophages and lipid transfer are both acutely reduced after myocardial infarction. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;478:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingwell B.A., Duffy D., Clementi R., Velkoska E., Feaster J., Gibson C.M. CSL112 (apolipoprotein A-I [human]) reduces the elevation in neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio induced by acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(9):1–3. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.033541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gille A., Easton R., D’Andrea D., Wright S.D., Shear C.L. CSL112 enhances biomarkers of reverse cholesterol transport after single and multiple infusions in healthy subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(9):2106–2114. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michael Gibson C., Korjian S., Tricoci P., et al. Safety and tolerability of CSL112, a reconstituted, infusible, plasma-derived apolipoprotein A-I, after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2016;134(24):1918–1930. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson C.M., Kazmi S.H.A., Korjian S., et al. CSL112 (apolipoprotein A-I [human]) strongly enhances plasma apoa-I and cholesterol efflux capacity in post-acute myocardial infarction patients: a PK/PD Substudy of the AEGIS-I trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2022;27 doi: 10.1177/10742484221121507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson C.M., Duffy D., Korjian S., et al. Apolipoprotein A1 infusions and cardiovascular outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(17):1560–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2400969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson C.M., Duffy D., Bahit M.C., et al. Apolipoprotein A-I infusions and cardiovascular outcomes in acute myocardial infarction according to baseline LDL-cholesterol levels: the AEGIS-II trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:5023–5038. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson C.M., Kastelein J.J.P., Phillips A.T., et al. Rationale and design of ApoA-I Event Reducing in Ischemic Syndromes II (AEGIS-II): a phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study to investigate the efficacy and safety of CSL112 in subjects after acute myocardi. Am Heart J. 2021;231:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen C., Cong B.L., Wang M., et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of myocardial damage and cardiac dysfunction in acute coronary syndrome patients. Integr Med Res. 2018;7(2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong P., Cui Z.-Y., Huang X.-F., Zhang D.-D., Guo R.-J., Han M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):131. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westerterp M., Gourion-Arsiquaud S., Murphy A.J., et al. Regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell mobilization by cholesterol efflux pathways. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(2):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker P.M., Danielson E., Fonseca F.A.H., et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridker P.M., Everett B.M., Thuren T., et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridker P.M., Libby P., MacFadyen J.G., et al. Modulation of the interleukin-6 signalling pathway and incidence rates of atherosclerotic events and all-cause mortality: analyses from the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39(38):3499–3507. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridker P.M., Bhatt D.L., Pradhan A.D., Glynn R.J., MacFadyen J.G., Nissen S.E. Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.