Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance continues to be a prevailing threat to human health worldwide, largely due to the arsenal of resistance mechanisms bacteria have evolved over years of exposure to traditional antibiotics. As an approach to devising therapeutics that can overcome this resistance, we hypothesized that peptides consisting of single transmembrane (TM) segments of membrane proteins may permeabilize bacterial membranes and thereby facilitate access of antimicrobials to their cytoplasmic targets. Using peptides derived from a natural TM helix from the AcrB component of the AcrAB-TolC efflux protein, we found that AcrB TM8 (wild type sequence: KKKK–FL(Abu)LAALYESWSI–NH2) and a “scrambled” analog of identical composition, charge, and overall hydrophobicity (TM8-S: KKKK–FSLEALW(Abu)ISAYL–NH2) (Abu = α-aminobutyric acid), resensitize Escherichia coli to sublethal doses of the antibiotics cloxacillin and nalidixic acid. These peptides induce 50–100% reduction of cell growth compared to bacteria treated with either peptide or antibiotic alone. The molecular basis for peptide-based permeabilization of the bacterial outer and inner membranes that contributes to the observed antibiotic potentiation was studied through several in vitro liposome-based assays and in vivo fluorescence-based assays. The overall results suggest that membrane proteins harbor a wealth of peptide sequences that may function as effective membrane-active peptides for the targeting of difficult-to-treat Gram-negative bacterial infections, and as such, provide valuable guidelines for the design of membrane-active peptides with synergistic antibacterial and antibiotic potentiation activity.

Introduction

Bacteria are constantly evolving new ways to overcome the use of antibiotics to the serious detriment of global health. In fact, it has been estimated that upward of 10 million deaths per year and more than $100 trillion in GDP loss could be attributed to the impact of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) within the next 30 years.1 In the global pursuit to develop new strategies to overcome this growing issue, the use of membrane-active peptides has been noted among the list of “antibiotic resistance breakers”.2 While there is often overlap in the mechanisms by which membrane-active peptides exert their activity against bacteria, they generally function to (1) directly permeabilize the bacterial membrane, classified as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs); (2) pass through the membrane to deliver conjugated antibacterial cargo into the bacterial cell, classified as cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs); or (3) embed within the membrane to target protein–protein interactions, classified as transmembrane peptides (TMs).3−5 Regardless of classification, these peptides tend to be relatively short (fewer than 100 amino acids for AMPs and fewer than 30 amino acids for CPPs) and cationic (typically in the +4 to +6 range), directing their activity preferentially toward the negatively charged bacterial membrane.3,6

Bacteria can be differentiated as Gram-negative or Gram-positive based on the composition and structure of their cell envelope. Gram-positive bacteria possess a single cell membrane surrounded by a thick layer of peptidoglycan, while Gram-negative bacteria possess both an outer and inner membrane separated by a thin layer of peptidoglycan.7 In addition to acting as a physical barrier to the use of antimicrobials, roughly 75% of the outer membrane is covered with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), rendering Gram-negative bacterial infections some of the most difficult to treat.8,9 Since the primary target of membrane-active peptides is often the bacterial inner membrane, these peptides must first permeate the outer membrane to then carry out their designed activity. This permeation is typically achieved by binding to LPS, replacing the divalent cations that stabilize the outer membrane, variously in a permeabilizing or nonpermeabilizing manner, to allow peptide access to the periplasm.10−12

We have previously demonstrated that the transmembrane segments of small multidrug resistance proteins can function as inhibitors of their natural oligomerization motif.13,14 In further work, we designed a membrane-active peptide using the natural sequence of transmembrane helix 8 (TM8) from the AcrB component of the AcrAB-TolC resistance-nodulation-division protein from Escherichia coli that efficiently prevented the efflux activity of the protein.15 In the present work, we sought to examine the mechanism by which this peptide permeates the bacterial outer membrane and then associates with the inner membrane to potentiate the effects of traditional antibiotics, with the goal of developing a promising therapeutic for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative infections. We identify primary sequence modifications that contribute to the ability of a compositionally scrambled peptide to effectively traverse the outer membrane to exert direct antibacterial activity, demonstrating that simply reorganizing an amino acid sequence can introduce serious consequences on peptide activity.

Results

Peptide Design and Therapeutic Characterization

Peptides used in this work were derived from the TM segment of the essential TM8 helix that participates in AcrB stabilization. Similar to another set of peptides derived from AcrB, these peptides were synthesized with an additional lysine tag to improve the solubility and specificity of peptide activity for bacterial membranes.15 Likewise, the natural sequence of TM8 was systematically reorganized in conjunction with the design of these previously published peptides to minimize the essential interaction motif of AcrB, thereby producing a control peptide for comparison to the natural TM8 peptide.5,15 Interestingly, we found that although TM8 (natural TM8 sequence) and TM8-S (scrambled version of TM8) have the exact same composition, charge and overall hydrophobicity, TM8-S exhibits a substantially lower MIC against both E. coli K12 and Bacillus subtilis (Table 1). Despite the increased antibacterial activity of TM8-S, it nevertheless exhibits significantly less hemolytic activity, improving its therapeutic potential as an antibacterial (Table 1).

Table 1. Peptide Sequences Used in the Present Work.

| MIC90 (μM)a |

TIb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peptide | sequencec | MHC (μM)d | E. coli K12 | B. subtilis | E. coli K12 | B. subtilis |

| TM8 | KKKK-FL(Abu)LAALYESWSI-NH2 | 6.3 ± 0.0 | >50.0 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | <0.1 | 1.9 |

| TM8-S | KKKK-FSLEALW(Abu)ISAYL-NH2 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 15.9 | 100 |

| Melittin | GIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQ-NH2 | 4.7 ± 3.1 | ||||

MIC is the minimum inhibitory concentration that resulted in >90% reduction in growth. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

TI is the therapeutic index, calculated as the MHC-to-MIC ratio.

Sequence of TM8 is based on the helical segment of TM8 from the membrane-spanning AcrB subunit of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump. TM8-S contains the same amino acid composition as TM8 but with the sequence scrambled. NH2, amidated C-terminus; Abu, α-aminobutyric acid.

MHC is the minimum hemolytic concentration that resulted in >10% hemolysis of human red blood cells. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Peptide-Induced Bacterial Resensitization

Considering our goal was to develop a membrane-active peptide potentiator to improve the activity of existing antimicrobials against Gram-negative bacterial pathogens, we undertook standard resensitization assays with E. coli K12. When sublethal concentrations of the TM8 peptide were combined with sublethal concentrations of the antibiotics cloxacillin and nalidixic acid, we observed significant resensitization (Figure 1). While TM8-S was generally less effective as an adjuvant than TM8—likely due to its natural antibacterial activity—TM8 was able to completely abolish bacterial growth when combined with cloxacillin (Figure 1A). In addition, while we observed ∼10% reduction in bacterial growth due to the presence of the peptide alone, cloxacillin alone resulted in virtually no reduction in growth, indicating the combination of peptide and cloxacillin is not simply an “additive” effect of the individual treatments.

Figure 1.

Resensitization of E. coli to sublethal doses of antibiotics. E. coli K12 were treated with (A) 50 μg/mL cloxacillin (CLOX) or (B) 0.5 μg/mL nalidixic acid (NAL), alone or in combination with 8 μM TM8 or 2 μM TM8-S. Peptide alone is represented by dark blue bars; antibiotic alone is represented by light blue dashed bars; the combination of both is represented by orange checkered bars. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h and the OD600 was measured to determine cell growth. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent trials. Two-way ANOVA was used to measure significance, confirmed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant).

Peptides Bind LPS with Strong Affinity

To elucidate the mechanism by which these peptides are exerting their antibiotic potentiation effects, we utilized a series of live bacterial and model membrane assays. It is well-established that the first step in peptide penetration of the bacterial cell envelope is to bind to and penetrate the bacterial outer membrane, which is composed largely of lipopolysaccharide (LPS).9 It is the negatively charged lipid A component of LPS that lends itself to a likely charge-based interaction with cationic peptides. To determine if the present peptides bind to LPS, we utilized the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay, which detects the presence of free endotoxin (LPS) in a sample.16 When incubated with the respective peptides, we observed that both peptides display a significant neutralizing effect on LPS in comparison to the DMSO control, with TM8 displaying upward of 90% binding, while TM8-S displays ∼82% binding (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Peptide binding to LPS. Eight μM of each peptide was incubated with E. coli (O111:B4) LPS and quantified with the LAL assay. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation. Experiments were performed in triplicate on two independent days. One-way ANOVA was used to measure significance, confirmed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant).

Peptides Adopt Mixed Secondary Structure in LPS Micelles

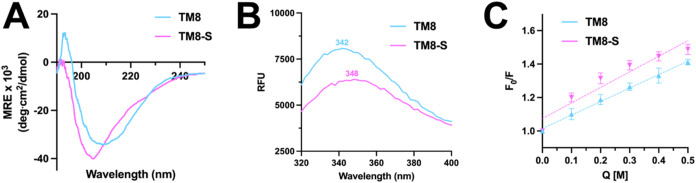

To further explore the peptides’ association with the outer membrane, we performed circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy in the presence of LPS, which spontaneously forms micelles in aqueous solution and has previously been used as a basic model for the bacterial outer membrane.17,18 Despite their sequence similarities, the peptides adopt very different secondary structures, with the TM8 peptide displaying a spectrum indicative of β-sheet formation, while TM8-S displays a mix of random coil and a-helical character (Figure 3A). As the peptides each contain a single internal tryptophan (Trp) residue, we then used the natural fluorescence as a marker for the polarity of the environment. We found that TM8-S displays little-to-no blue shift at 348 nm, suggesting its preference for the aqueous milieu, while TM8 displays a slight blue shift at 342 nm, potentially due to β-sheet-associated aggregation (Figure 3B). Finally, we used acrylamide—a quencher of Trp fluorescence—to assess the depth to which each of the peptides associates within the LPS micelle.19 Consistent with its lack of blue shift observed previously, TM8-S is more quenched in comparison to TM8, as indicated by the higher Stern–Volmer slope (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Peptide interaction with LPS micelles. Twenty μM of each peptide were reconstituted into LPS micelles to assess (A) secondary structure via circular dichroism, (B) tryptophan fluorescence, and (C) accessibility to acrylamide (Q) quenching. Numbers above/below the fluorescence spectra represent the wavelength of maximum fluorescence. Data are presented as mean of three independent trials. Stern–Volmer plots of tryptophan fluorescence quenching are presented as mean and standard deviation of three independent trials. Dashed lines represent a simple linear regression.

Peptide-Induced Outer Membrane Permeabilization

Having confirmed that the present peptides have strong affinity for LPS, we undertook to assess the consequence of that binding in a live bacteria model. We utilized hexidium iodide (HI) to measure outer membrane permeabilization, as the nucleic acid-binding dye is impermeant to Gram-negative bacteria when the outer membrane is intact.20 In comparison to untreated E. coli K12, the addition of DMSO induces no change in relative fluorescence units (RFU), while the positive control EDTA induces an immediate and sustained RFU increase (Figure 4). Addition of each peptide induces minor outer membrane permeabilization, only reaching a maximum of about 50% of that of EDTA after 2 h (Figure 4). Melittin—included as an AMP control for comparison—reaches levels of permeabilization close to that of EDTA, but with a more sporadic change in RFU, potentially due to its concentration being above the MIC (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Peptide-induced outer membrane permeabilization. E. coli K12 were incubated with 10 μg/mL hexidium iodide for 15 min before being treated with 8 μM of each peptide or 50 mM of EDTA. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) were measured immediately for up to 2 h. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation of three independent trials.

Peptides Induce Bacterial Membrane Permeabilization and Depolarization

Upon permeating the bacterial outer membrane, the peptides can associate with the bacterial inner membrane, which we’ve previously shown to be a primary site of action for another set of AcrB-derived peptides.5 To assess the effects of peptide association with the bacterial inner membrane in a live bacterial model, we utilized a combination of SYTOX Green- and DiOC2(3)-based assays, which harness fluorescent dyes to monitor membrane permeabilization and depolarization in real time, respectively.21,22 With a lag time of only a few minutes between peptide addition and fluorescence monitoring, we found that in comparison to untreated E. coli K12, the peptides induce immediate membrane permeabilization that is sustained over the course of the hour (Figure 5A). Similarly, this membrane permeabilization resulted in immediate dissipation of the proton motive force (Figure 5B). From these experiments, TM8 appears to maximally depolarize and permeabilize the membrane within 15 min, while TM8-S-induced depolarization occurs slightly faster, plateauing within just 5 min (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Peptide-induced inner membrane permeabilization and depolarization. E. coli K12 were incubated with (A) 5 μM SYTOX for 30 min or (B) 30 μM DiOC2(3) for 5 min before being treated with 8 μM of each peptide. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) were measured immediately and for up to 1 h. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation of three independent trials.

Peptide Sampling of the Lipid Bilayer May Discern Differences in Activity

To further explore any differences in the peptides’ ability to associate with the bacterial inner membrane, we incubated them with large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of 3:1 POPE/POPG, a standard phospholipid mixture that mimics the bacterial inner membrane.23 Both TM8 and TM8-S adopt α-helical character in the presence of these LUVs (Figure 6A). To assess the depth of peptide penetration, we supplemented this lipid mixture with increasing amounts of the dibrominated lipid PC-Br(11,12) which contains bromine atoms in positions 11 and 12 of the hydrophobic tail.24 We observed that the TM8-S peptide can penetrate the bilayer more deeply than TM8, as indicated by the higher slope of quenching by TM8-S (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Peptide interaction with the bacterial inner membrane mimetic. (A) 20 μM of each peptide was added to LUV’s composed of 3:1 POPE/POPG at a peptide-to-lipid ratio of 62.5 and circular dichroism was used to assess secondary structure. (B) 10 μM of each peptide was added to LUV’s of the same composition and at the same ratio, but also containing PC-Br(11,12) at the indicated percentage. Stern–Volmer plots of tryptophan quenching were generated. Dashed lines represent a simple linear regression of the data. WMF represents wavelength of maximum fluorescence.

Discussion

Gram-negative species of bacteria represent seven of the 11 top antibiotic-resistant threats on the World Health Organization priority pathogen list as of 2024.25 Here, we have identified two membrane-active peptides–one with the natural sequence of TM8 from the E. coli efflux protein AcrB and the other a scrambled version thereof—whose properties provide support for the idea that transmembrane helical segments of natural membrane proteins embody a wealth of potential sequences for the design of effective membrane-active peptides to combat MDR bacteria. Both peptides effectively potentiated the effects of existing antibiotics—nalidixic acid and cloxacillin—introducing up to complete elimination of cell growth compared to bacteria treated with either peptide or antibiotic alone (Figure 1). As well, reorganizing the amino acids within the natural TM8 helix introduced significant antibacterial activity, while simultaneously minimizing hemolysis.

Despite the TM8 peptide displaying the stronger ability to bind to and neutralize free LPS, this binding only translated to minor increases in permeabilization of the bacterial outer membrane (Figures 2 and 4). Since the LAL endotoxin kit used to quantify LPS binding utilizes LPS derived from the O111:B4 E. coli strain, we decided to use the same LPS for our binding assays and membrane mimetic work. For the remainder of our experiments, we worked with the K12 E. coli strain, which expresses an LPS that is deficient in the O-antigen typically found in LPS harvested from other Gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli O111:B4.26 However, we anticipate that these peptides bind to the lipid A and core portion of the LPS molecule—due to the presence of conserved negative charges—providing confidence that the observed LPS binding is representative of peptide activity in the presence of E. coli K12 as well.

Considering that TM8 displays β-sheet character in the presence of LPS micelles, we suggest the minimal blue shift in Trp fluorescence and lack of quenching by acrylamide may be due to aggregation (Figure 3). It has been previously demonstrated that strong LPS binding in an aggregated state effectively reduces the ability of a peptide to permeate the outer membrane, which may thus be the case for TM8.27 TM8-S on the other hand adopts partial helical character, while also remaining accessible for quenching, suggesting it may have an ideal affinity for LPS such that it can effectively bind to the bacterial outer membrane, but not so strongly that it remains isolated to it (Figure 3). This hypothesis holds up when one compares the relative MICs of these peptides against Gram-negative to Gram-positive bacteria, which possess only a cytoplasmic lipid bilayer. We found roughly a 6-fold decrease in MIC for TM8-S when incubated with the Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis, versus E. coli K12 (Table 1). In comparison, TM8 displays more than a 15-fold reduction in MIC against B. subtilis, suggesting that the peptide is losing a substantial amount of activity against Gram-negative bacteria due to the presence of the outer membrane (Table 1). Of course, both peptides display a much lower respective MIC against the Gram-positive bacteria, as both the cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-positive bacteria and the inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria contain anionic lipids that promote favorable electrostatic interactions with the peptides.28

In comparison to another set of peptides derived from the AcrB efflux pump, the peptides in this work induce a much more rapid increase and plateau in fluorescence in both the membrane permeabilization and depolarization assays (Figure 5).5 This time-based activity closely resembles the activity of the pore-forming peptide melittin, which has been shown to induce rapid, transient permeabilization of the inner membrane.5,29,30 Pore formation of this type is induced by peptides that adsorb to the lipid bilayer in a surface-bound state, applying pressure across the bilayer that is relieved by pore formation and distribution of the peptide between inner and outer leaflets. These pores rapidly dissolve, allowing the membrane to reseal, resulting in the plateau of fluorescence over time.29 This model of membrane activity for the peptides in this work is also supported by the experiments with dibrominated lipids, as neither peptide was able to penetrate as deeply into the bilayer as peptides in previous work that are longer and more hydrophobic in nature (Figure 6B).5 Regardless of the exact mechanism of potential pore formation, it is clear that disruption of both outer and inner membrane integrity is a key factor in the antibiotic potentiating activity of these peptides. By increasing membrane permeability and therefore access of traditional antibiotics to the cell interior, these peptides amplify the natural antibacterial activity of both cloxacillin and nalidixic acid in the presence of bacteria.

Outside of the peptides’ ability to penetrate the bacterial cell envelope, their ability to effectively bind LPS also introduces an immunomodulatory discussion. It is well-documented that several AMPs can bind and neutralize LPS, thereby limiting the pro-inflammatory endotoxin response of the immune system.31 For example, the human AMP, LL-37, has been shown to reduce LPS-induced expression of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), as well as secretion of TNF-α from macrophages.32 Thus, with each of our peptides displaying strong LPS binding, there is a high potential for that to translate into the same anti-inflammatory activity of LL-37.

Conclusions

We have shown that natural TM domains from membrane proteins can function as adjuvants in concert with existing antibiotics to inhibit bacterial growth. As well, it is not just sequence composition that determines peptide activity, as the reorganization of the sequence can improve or hinder the designed activity. While a synergistic combination of bacterial outer and inner membrane permeabilization is the de facto driving mechanism through which these peptides exert their potentiating activity, it remains to be determined whether discrete peptide-antibiotic interactions mediate these events. Our overall results provide a route for furthering the understanding and the utility of membrane-active peptides as therapeutics for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial pathogens.

Methods

Peptide Quantification and Storage

Peptides used in this work were purchased from Biosynth (Lelystad, NL, Louisville, KY, Gardner, MA) with >90% purity. Peptides were received as a lyophilized powder before being solubilized and quantified in either 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol or 50% acetonitrile using the absorption at 280 nm in a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette and an Ultrospec 3000 UV/vis spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech). Melittin peptide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Peptides were aliquoted and lyophilized for storage at −20 °C. All peptides were solubilized in DMSO for experimental use.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assays

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as previously described.14 Briefly, peptides were serially diluted in 96-well plates (Corning, ref 2598) from a maximum of 50 μM. Overnight bacterial cultures in Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) were added at 50,000 CFU/well and incubated for 20 h at 37 °C. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured to determine cell growth. MIC was considered the peptide concentration resulting in >90% reduction in growth.

Minimum Hemolytic Concentration (MHC) Assays

Hemolysis assays were performed as previously described.33 Briefly, human red blood cell samples were drawn from a consenting donor and stored for a maximum of 3 days at 4 °C. For each experiment, red blood cells were collected through centrifugation at 1000 RCF for 5 min, washed with PBS three times, and resuspended in PBS at a 4% ratio. 100 μL of red blood cells were added to 96-well plates (Corning, ref 2598) containing DMSO, 1% Triton, or peptides serially diluted from a maximum of 100 μM. After a 1-h incubation at 37 °C, the plates were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected to measure the absorbance at 540 nm. Data were normalized to cells alone (0% lysis) and 1% Triton (100% lysis) using the formula

| 1 |

Resensitization Assays

Peptide adjuvant activity was determined using resensitization assays described previously.14 Briefly, overnight bacterial cultures in MHB were plated at 50,000 CFU/well with (1) a sublethal dose of peptide, (2) a sublethal dose of antimicrobial or (3) a combination of both. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 20 h before measuring the OD600 to determine cell growth. Fold reduction was calculated using eq 2 below, where %Cell Growthpep or anti is the bacterial cell growth after treatment with either the peptide or the antimicrobial alone and %Cell Growthcombined is the bacterial cell growth after the combined peptide and antimicrobial treatment

| 2 |

Liposome Preparation

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUV’s) were prepared as previously described.5 Briefly, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (POPG) (Avanti Polar Lipids) were mixed at 3:1 in chloroform and dried. To assess peptide penetration, 1-palmitoyl-2-(11,12-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC-Br(11,12), Avanti Polar Lipids) was substituted for POPE. Lipid mixtures were washed with water and lyophilized to a powder. To form LUV’s, lipid mixtures were resuspended in buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7), freeze–thawed 5 times (dry ice to 50 °C) and extruded through 0.2 μm Whatman Nuclepore polycarbonate membrane filter (Cytiva) at least 15 times with a mini-extruder.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of peptides were recorded between 190 and 250 nm on a Jasco J-1500 CD spectropolarimeter using a 0.1 cm path length quartz cuvette, scanning at 50 nm/s with three accumulations. Peptide spectra were acquired in 1 mg/mL LPS or 3:1 POPE/POPG, in buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7), at a constant peptide concentration of 20 μM. Data are presented from 200 to 250 nm for ease of visualization. Raw millidegree (mdeg) spectra were background subtracted and converted to mean residue ellipticity (MRE) using eq 3 below, where c is the concentration in μM, l is the path length in cm, and n is the number of residues.

| 3 |

Tryptophan Fluorescence and Quenching

Tryptophan fluorescence for peptide samples in 1 mg/mL LPS or 3:1 POPE/POPG, in buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7), were measured on a Photon Technology International fluorimeter using a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. Tryptophan fluorescence was excited at 280 nm with a 2 nm slit width and emission was recorded every 2 nm from 310 to 400 nm with a 5 nm slit width. Data are presented from 320 to 400 nm for ease of visualization and the average of three independent trials are presented. To assess peptide insertion, dibrominated lipids were included at increasing percentage of total lipid or acrylamide was added to samples in 0.1 M increments and the area under the curve were used to generate Stern–Volmer of quenching (F0/F) against quencher concentration.

Inner Membrane Permeabilization Assay

Overnight cultures of E. coli K12 grown in Mueller-Hinton broth were resuspended to an OD600 of 0.2 in M9 minimal media or 70% isopropanol. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to achieve viable and permeabilized cells before resuspending in fresh media. Cultures were incubated with 5 μM SYTOX Green Nucleic Acid Stain (Invitrogen) for 30 min in the dark before being added to opaque 96-well plates (Corning, ref 3650) containing 8 μM of peptide. Fluorescence was measured every 5 min for 1 h using a SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 523 nm. Fluorescence was normalized to the isopropanol-treated cells (100% permeabilization) and the mean and standard deviation of three independent trials are presented.

Inner Membrane Depolarization Assay

Overnight cultures of E. coli K12 grown in Mueller-Hinton broth were resuspended to an OD600 of 0.4 in M9 minimal media. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before the addition of 10 mM EDTA. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min prior to centrifugation and resuspension in fresh M9 minimal media. Cultures were then incubated with 30 μM 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2(3), Invitrogen) for 5 min in the dark before being added to opaque 96-well plates (Corning, ref 3650) containing 8 μM of peptide or 20 μM of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazine (CCCP). Fluorescence was measured every 2.5 min for 1 h using a SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 450 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm. Fluorescence was normalized to dye only (max fluorescence) and the mean and standard deviation of three independent trials are presented.

Lipopolysaccharide Binding Assay

Peptide binding to LPS was quantified using the chromogenic limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) kit per manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, 1.0 EU/mL E. coli (O111:B4) LPS was reconstituted in Endotoxin Free Water (EFW) provided and combined with 8 μM peptide samples also prepared in EFW. LAL reagent was added to each well and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 9 min. Chromogenic substrate was then added and incubated for an additional 6 min before the reaction was stopped by the addition of 25% acetic acid. Absorbance at 405 nm (OD405) was used as a measure of free LPS in the sample. Sample data was blank subtracted (EFW alone) and LPS binding was calculated per eq 4

| 4 |

Outer Membrane Permeabilization Assay

Overnight cultures of E. coli K12 grown in Mueller-Hinton broth were resuspended to an OD600 of 0.2 in M9 minimal media. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to the addition of 10 μg/mL Hexidium Iodide (Invitrogen). Cultures were incubated in the dark for an additional 15 min before being added to opaque 96-well plates (Corning, ref 3650) containing 8 μM of peptide or 50 mM of EDTA. Fluorescence was measured every 3 min for 2 h using a SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 518 nm and an emission wavelength of 600 nm. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent trials every 15 min for ease of visualization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the team at the Structural and Biophysical Core Facility at The Hospital for Sick Children for their ongoing assistance with equipment.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMR

antimicrobial resistance

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

- CPPs

cell-penetrating peptides

- TMs

transmembrane peptides

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- SMR

small multidrug resistance

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- LUVs

large unilamellar vesicles

- LAL

Limulus amebocyte lysate

- HI

hexidium iodide

- CD

circular dichroism

This work was supported by grants to C.M.D. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR project grant no. 376666) and from Cystic Fibrosis Canada.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- O’Neill J.Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. In Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; Wellcome Trust, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laws M.; Shaaban A.; Rahman K. M. Antibiotic Resistance Breakers: Current Approaches and Future Directions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 43, 490–516. 10.1093/femsre/fuz014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci F. G.; Akbulut B. S.; Ozkirimli E. Membrane Active Peptides and Their Biophysical Characterization. Biomolecules 2018, 8 (3), 77 10.3390/BIOM8030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. J.; Johnson T. S.; Deber C. M. Transmembrane Peptide Effects on Bacterial Membrane Integrity and Organization. Biophys. J. 2022, 121 (17), 3253–3262. 10.1016/j.bpj.2022.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. S.; Bourdine A. A.; Deber C. M. Hydrophobic Moment Drives Penetration of Bacterial Membranes by Transmembrane Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299 (11), 105266 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shagaghi N.; Palombo E. A.; Clayton A. H. A.; Bhave M. Antimicrobial Peptides: Biochemical Determinants of Activity and Biophysical Techniques of Elucidating Their Functionality. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34 (4), 62 10.1007/s11274-018-2444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhavy T. J.; Kahne D.; Walker S. The Bacterial Cell Envelope. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2 (5), a000414 10.1101/CSHPERSPECT.A000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcour A. H. Outer Membrane Permeability and Antibiotic Resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2009, 1794, 808–816. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G.; Raina S. Regulated Control of the Assembly and Diversity of LPS by Noncoding SRNAs. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 153561 10.1155/2015/153561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaara M. Agents That Increase the Permeability of the Outer Membrane. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56 (3), 395–411. 10.1128/mr.56.3.395-411.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephani J. C.; Gerhards L.; Khairalla B.; Solov’yov I. A.; Brand I. How Do Antimicrobial Peptides Interact with the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria? Role of Lipopolysaccharides in Peptide Binding, Anchoring, and Penetration. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10 (2), 763–778. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.3c00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P.; Ayappa K. G. A Molecular Dynamics Study of Antimicrobial Peptide Interactions with the Lipopolysaccharides of the Outer Bacterial Membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 2022, 255 (6), 665–675. 10.1007/s00232-022-00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen B. E.; Deber C. M. Drug Efflux by a Small Multidrug Resistance Protein Is Inhibited by a Transmembrane Peptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56 (7), 3911–3916. 10.1128/AAC.00158-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. J.; Stone T. A.; Deber C. M. Peptide-Based Efflux Pump Inhibitors of the Small Multidrug Resistance Protein from Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63 (9), e00730-19 10.1128/AAC.00730-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesin J. A.; Stone T. A.; Mitchell C. J.; Reading E.; Deber C. M. Peptide-Based Approach to Inhibition of the Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pump AcrB. Biochemistry 2020, 59 (41), 3973–3981. 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torcato I. M.; Huang Y. H.; Franquelim H. G.; Gaspar D.; Craik D. J.; Castanho M. A. R. B.; Henriques S. T. Design and Characterization of Novel Antimicrobial Peptides, R-BP100 and RW-BP100, with Activity against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2013, 1828 (3), 944–955. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos N. C.; Silva A. C.; Castanho M. A. R. B.; Martins-Silva J.; Saldanha C. Evaluation of Lipopolysaccharide Aggregation by Light Scattering Spectroscopy. Chembiochem 2003, 4 (1), 96–100. 10.1002/cbic.200390020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S.; Deber C. M. Interaction of Designed Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides with the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14 (1), 1894 10.1038/s41598-024-51716-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strambini G. B.; Gonnelli M. Fluorescence Quenching of Buried Trp Residues by Acrylamide Does Not Require Penetration of the Protein Fold. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114 (2), 1089–1093. 10.1021/jp909567q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason D. J.; Shanmuganathan S.; Mortimer F. C.; Gant V. A. A Fluorescent Gram Stain for Flow Cytometry and Epifluorescence Microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64 (7), 2681–2685. 10.1128/AEM.64.7.2681-2685.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth B. L.; Poot M.; Yue S. T.; Millard P. J. Bacterial Viability and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing with SYTOX Green Nucleic Acid Stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2421–2431. 10.1128/aem.63.6.2421-2431.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson M. A.; Siegele D. A.; Lockless S. W. Use of a Fluorescence-Based Assay To Measure Escherichia Coli Membrane Potential Changes in High Throughput. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00910-20 10.1128/AAC.00910-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn K.; Róg T.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M. Phosphatidylethanolamine-Phosphatidylglycerol Bilayer as a Model of the Inner Bacterial Membrane. Biophys. J. 2005, 88 (2), 1091–1103. 10.1529/biophysj.104.048835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolen E. J.; Holloway P. W. Quenching of Tryptophan Fluorescence by Brominated Phospholipid. Biochemistry 1990, 29 (41), 9638–9643. 10.1021/bi00493a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization W. H.WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461.

- Stevenson G.; Neal B.; Liu D.; Hobbs M.; Packer N. H.; Batley M.; Redmond J. W.; Lindquist L.; Reeves P. Structure of the O Antigen of Escherichia Coli K-12 and the Sequence of Its Rfb Gene Cluster. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176 (13), 4144–4156. 10.1128/jb.176.13.4144-4156.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papo N.; Shai Y. A Molecular Mechanism for Lipopolysaccharide Protection of Gram-Negative Bacteria from Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (11), 10378–10387. 10.1074/jbc.M412865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig J. Thermodynamics of Lipid–Peptide Interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2004, 1666 (1–2), 40–50. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmschneider J. P.; Ulmschneider M. B. Melittin Can Permeabilize Membranes via Large Transient Pores. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 7281 10.1038/s41467-024-51691-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimley W. C.; Hristova K. The Mechanism of Membrane Permeabilization by Peptides: Still an Enigma. Aust. J. Chem. 2020, 73 (3), 96–103. 10.1071/CH19449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld Y.; Shai Y. Lipopolysaccharide (Endotoxin)-Host Defense Antibacterial Peptides Interactions: Role in Bacterial Resistance and Prevention of Sepsis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2006, 1758 (9), 1513–1522. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld Y.; Papo N.; Shai Y. Endotoxin (Lipopolysaccharide) Neutralization by Innate Immunity Host-Defense Peptides: Peptide Properties and Plausible Modes of Action. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (3), 1636–1643. 10.1074/JBC.M504327200/ASSET/A2553D51-B33D-4C04-8B00-F09D23FABCAE/MAIN.ASSETS/GR7.JPG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S.; Stone T. A.; Deber C. M. Uncoupling Amphipathicity and Hydrophobicity: Role of Charge Clustering in Membrane Interactions of Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Biochemistry 2021, 60 (34), 2586–2592. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]