Abstract

To explore the role and underlying mechanisms of Piezo1 in sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction (SIMD). A SIMD model was established in mice via intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection. Cardiac function, histology, Piezo1 protein expression, and cardiac troponin T (cTnT) were assessed. Piezo1’s role in SIMD was investigated using the agonist Yoda1, inhibitor GsMTx-4, and cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 knockout (Piezo1ΔCM) mice. Dual Specificity Phosphatase 3 (DUSP3) protein levels were also assessed to explore potential mechanisms. SIMD mice exhibited significantly impaired cardiac function, along with increased Piezo1 protein and cTnT levels. Piezo1 activation improved cardiac function and reduced tissue damage, while inhibition worsened SIMD. Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibited more severe cardiac dysfunction and injury, especially with LPS treatment. DUSP3 protein levels were significantly elevated in Piezo1ΔCM and LPS-treated hearts. Piezo1 exerted a protective role in SIMD, potentially through the modulation of DUSP3.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-00829-2.

Keywords: Piezo1, Sepsis, SIMD, DUSP3

Subject terms: Physiology, Cardiology

Introduction

Sepsis, a life-threatening condition characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection, poses a major global health burden, with an estimated 31.5 million cases annually and mortality rates reaching 26%1–4. Among its severe complications, sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction (SIMD) significantly contributes to sepsis-related mortality5. Although excessive inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction have been implicated in SIMD pathogenesis, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive6,7.

Piezo1 channel, a mechanosensitive ion channel, plays a critical role in various physiological processes across diverse cell types and tissues8–10. Within the cardiovascular system, Piezo1 is essential for mechanical signal transduction and myocardial contractile function. Mounting evidence suggests that Piezo1 mutations or aberrant expression can disrupt myocardial mechanical conduction, potentially leading to systolic dysfunction, arrhythmias, and maladaptive remodeling11–14.

Recent investigations have highlighted Piezo1’s potential role in sepsis pathophysiology15. During sepsis, the dysregulated immune response triggers a cascade of inflammatory mediators, resulting in systemic inflammation and organ dysfunction16,17. Furthermore, Piezo1 activation may modulate this excessive inflammatory response by regulating the production and release of inflammatory factors18–20. Additionally, Piezo1 contributes to cardiac remodeling: it regulates calmodulin expression through a positive feedback mechanism, driving pathological cardiac hypertrophy21,22. In ischemic heart disease, Piezo1 regulates Ca2+ production and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling in cardiomyocytes, enabling cardiac adaptation to pathological mechanical loads13. Despite these advances, the specific role of Piezo1 in SIMD remains poorly understood.

This study aims to elucidate Piezo1’s involvement in SIMD pathogenesis and explore its potential underlying mechanisms. By investigating Piezo1’s function in this context, we seek to uncover novel insights into sepsis-related cardiac dysfunction and potentially identify therapeutic targets for this challenging clinical condition.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatments

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Animal Care and Use and adhered to the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1985). All methods that were mentioned were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. C57BL/6 N female mice (10 weeks old) were obtained from Vital River Laboratory (Beijing, China), while age-matched Piezo1ΔCM and Piezo1flox/flox female mice were procured from Cyagen Biosciences, Inc (Jiangsu, China). Animals were housed under standard conditions (22 °C ± 2 °C, 60% humidity, 12-hour light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water.

Following a two weeks acclimatization period, C57BL/6 N mice were randomly assigned to four groups: Control (CTR), LPS, Piezo1 agonist, and Piezo1 inhibitor. The Piezo1 agonist Yoda1 (HY-18723, MedChemExpress, USA) and inhibitor GsMTx-4 (HY-P1410, MedChemExpress, USA) were administered via single intraperitoneal injections 1 h prior to LPS injection, at doses of 500 µg/kg23 and 1.5 mg/kg24, respectively. Vehicle controls were treated with an equivalent volume of DMSO diluted in saline to ensure consistency across experimental conditions. To further elucidate Piezo1’s role, cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 knockout mice (Piezo1ΔCM) were divided into four groups: Piezo1flox/flox, Piezo1flox/flox + LPS, Piezo1ΔCM, and Piezo1ΔCM + LPS. SIMD was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (15 mg/kg; L8880, Solarbio, Beijing, China)25,26. Control animals received an equivalent volume of normal saline. Echocardiography was performed 12 h post-injection. All animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), followed by blood and tissue collection. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 min and stored at − 80 °C. Heart tissues were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde or snap-frozen at − 80 °C.

Echocardiography assessment

Transthoracic M-mode echocardiograms were performed using a Vevo 2100 ultrasound device (Visual Sonics Inc., Toronto, Canada) 12 h post-LPS administration. Prior to imaging, mice were anesthetized via inhalation of isoflurane in oxygen at a flow rate of 1 L/min. For induction, 3% isoflurane was used to ensure consistent and humane anesthesia, followed by a reduction to 1% isoflurane for maintenance during the imaging procedure. Anesthesia depth was monitored by assessing respiratory rate and pedal withdrawal reflex, with the isoflurane concentration adjusted as necessary to maintain stable physiological conditions. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF%) and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS%) were measured over three consecutive cardiac cycles, and the mean values were recorded.

Histological analysis

Left ventricular tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned to 4 μm thickness. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Stained sections were examined under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse CI, Tokyo, Japan).

Plasma cTnT measurement

Plasma cardiac troponin T (cTnT) levels were quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (KE1753, ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company, US) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

Left ventricular tissue lysates were prepared in cold radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer, centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min, and protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (P0012, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Proteins (100 µg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidenefluoro membranes (Merck Millipore, Co Cork, Ireland). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against Piezo1 (1:500, 15939-1-AP, proteintech, Illinois, USA), DUSP3 (1:1000, 28284-1-AP, proteintech, Illinois, USA), Beta-tubulin (1:1000, WL01931, Wanleibio, Shenyang, China) and GAPDH (1:10000, ET1601-1, Huabio, Hangzhou, China). After incubation with goat anti-rabbit II antibody (1:5000, 5220 -0336, Seracare, Massachusetts, USA) at room temperature for 1 h, protein bands were visualized using a ChemiDoc XRS + system (Bio-Rad, California, USA), and quantified using Image J software.

PCR genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted using a Genomic DNA extraction kit (9765, Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan) and amplified by PCR. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 130 V for 30 min and visualized under ultraviolet light.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, while multiple group comparisons employed one-way ANOVA followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Piezo1 was upregulated in SIMD mice

To investigate Piezo1’ role in SIMD, we established a mouse model of sepsis using LPS administration. Echocardiographic analysis revealed significant reductions in LVEF% and LVFS% in LPS-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 1A–C), indicating impaired cardiac function. Additionally, LPS-treated mice exhibited significantly lower heart rates compared to controls (Fig. 1D). Plasma cTnT levels, a marker of myocardial injury, were markedly elevated in the LPS group (Fig. 1E). Histological examination of heart tissue using HE staining demonstrated normal morphology in controls, while LPS-treated mice exhibited characteristic features of acute myocardial injury and inflammation, including tissue edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, and nuclear swelling (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Piezo1 was upregulated in SIMD mice. A mouse model of sepsis was induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (15 mg/kg). (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images 12 h post-LPS administration. Scale bar = 100 ms/2 mm. (B-C) Quantitative analysis of LVEF% and LVFS%. (D) Quantitative analysis of Heart rate. (E) Plasma cardiac cTnT levels. Beta-tubulin served as a loading control. (F) Representative HE stained heart sections. Scale bar = 50 μm. (G) Western blot analysis of Piezo1 expression in mouse heart tissue. Beta-tubulin served as a loading control. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Blots are representative of n = 6 biological replicates.

Notably, Piezo1 protein levels were significantly increased in heart tissue following LPS administration (Fig. 1G). These findings suggested that Piezo1 upregulation might contribute to the pathogenesis of SIMD.

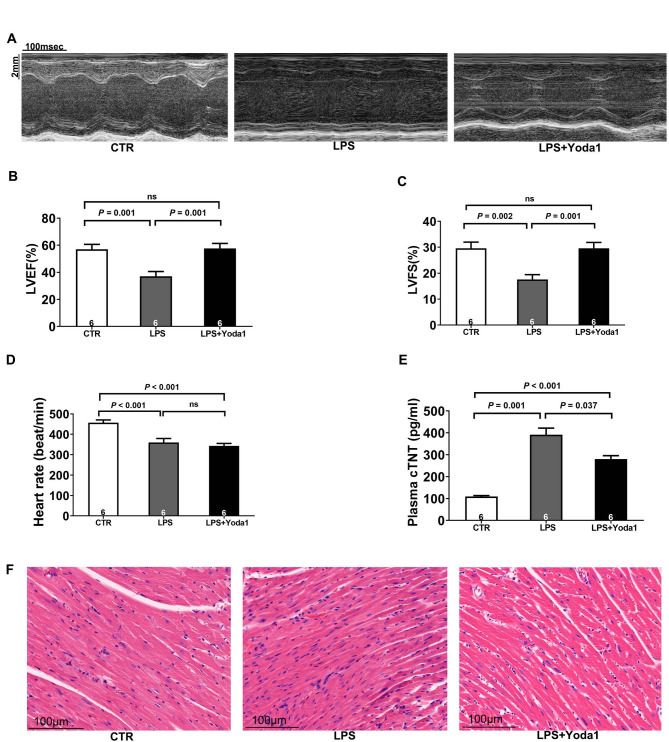

Piezo1 agonist Yoda1 ameliorated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice

To investigate the therapeutic potential of Yoda1 in SIMD, we evaluated its effects in a mouse model of sepsis induced by LPS administration. Echocardiographic analysis showed that LVEF% and LVFS% were significantly higher in the LPS + Yoda1 group compared to the LPS group (Fig. 2A–C), indicating that Yoda1, a Piezo1 agonist, improved cardiac function in SIMD mice. However, both the LPS and LPS + Yoda1 groups exhibited significantly lower heart rates than the control group (Fig. 2D), suggesting that while Yoda1 enhanced cardiac performance, it did not counteract the LPS-induced reduction in heart rate. Further supporting these functional improvements, plasma cTnT levels were significantly decreased in the LPS + Yoda1 group compared to the LPS group (Fig. 2E). Additionally, histological examination revealed that Yoda1 treatment attenuated myocardial injury in the LPS + Yoda1 group, with reduced tissue damage, inflammatory cell infiltration, and cellular degeneration compared to the LPS group (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Piezo1 agonist Yoda1 ameliorated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice. Mice were pretreated with Yoda1 1 h before LPS (15 mg/kg) administration (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images 12 h post-LPS injection. Scale bar = 100 ms/2 mm. (B-C) Quantitative analysis of LVEF% and LVFS%. (D) Quantitative analysis of Heart rate. (E) Plasma cTnT levels. (F) Representative HE stained heart sections. Scale bar = 50 μm. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Piezo1 inhibitor GsMTx-4 aggravated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice

To assess the impact of GsMTx-4 in SIMD, we utilized a mouse model of sepsis induced by LPS administration. Echocardiographic analysis revealed that both LVEF% and LVFS% were significantly reduced in the LPS + GsMTx-4 group compared to the LPS group (Fig. 3A–C), indicating further deterioration of cardiac function in mice treated with GsMTx-4, a Piezo1 inhibitor. Both the LPS and LPS + GsMTx-4 groups exhibited significantly reduced heart rates compared to the control group (Fig. 3D), suggesting that LPS induces bradycardia, an effect not worsened by GsMTx-4. Additionally, plasma cTnT levels were significantly elevated in the LPS + GsMTx-4 group compared to the LPS group (Fig. 3E). Histological analysis showed more pronounced myocardial injury in the LPS + GsMTx-4 group, with extensive tissue damage, increased inflammatory cell infiltration, and severe cellular degeneration compared to the LPS group (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Piezo1 inhibitor GsMTx-4 aggravated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice. Mice were pretreated with GsMTx-4 1 h before LPS administration (15 mg/kg). (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images 12 h post-LPS injection. Scale bar = 100 ms/2 mm. (B-C) Quantitative analysis of LVEF% and LVFS%. (D) Quantitative analysis of Heart rate. (G) Plasma cTnT levels. (F) Representative HE stained heart sections. Scale bar = 50 μm. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 deficiency exacerbated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice

To further elucidate the role of Piezo1 in SIMD, we employed Piezo1ΔCM mice. Knockout efficiency was verified by PCR-genotyping assay (Fig. 4F; see Supplementary Materials Fig. 1 and Table 1 for detailed knockout method and primer sequences). Echocardiographic analysis revealed that Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibited decreased LVEF% and LVFS% at baseline compared to Piezo1flox/flox controls. Following LPS administration, both Piezo1flox/flox and Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibited further reductions in LVEF% and LVFS% (Fig. 4A–C). Additionally, LPS treatment significantly reduced heart rates in both genotypes compared to their respective untreated controls (Fig. 4D). However, no significant difference in baseline heart rates was observed between Piezo1flox/flox and Piezo1ΔCM mice, indicating that cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 deletion did not affect resting heart rate. Histological examination showed that Piezo1ΔCM mice displayed features of acute myocardial injury and inflammation after LPS treatment compared to Piezo1flox/flox controls (Fig. 4G). Consistent with these findings, plasma cTnT levels were significantly elevated in Piezo1ΔCM mice compared to Piezo1flox/flox controls (Fig. 4E), underscoring greater cardiac damage in the absence of cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1. Immunoblotting revealed upregulation of DUSP3, a downstream target of Piezo1, in both Piezo1ΔCM and Piezo1flox/flox + LPS compared to Piezo1flox/flox controls (Fig. 4H). These findings suggested that cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of Piezo1 exacerbated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD, highlighting the protective role of Piezo1 in maintaining cardiac function during sepsis. The upregulation of DUSP3 in Piezo1flox/flox + LPS, Piezo1ΔCM and Piezo1ΔCM + LPS groups suggested a potential mechanistic link between Piezo1 and DUSP3 in the context of SIMD.

Fig. 4.

Cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 deficiency exacerbated cardiac dysfunction in SIMD mice. Both Piezo1ΔCM and Piezo1flox/flox mice were subjected to LPS (15 mg/kg) injection. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images 12 h post-LPS administration. Scale bar = 100 ms/2 mm. (B-C) Quantitative analysis of LVEF% and LVFS%. (D) Quantitative analysis of Heart rate. (E) Plasma cTnT levels. (F) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products for Piezo1 genotyping. (G) Representative HE stained heart sections. Scale bar = 50 μm. (H) Western blot analysis of DUSP3 in mouse heart tissue. GAPDH served as a loading control. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. S denoted mice was treated with normal saline. LPS denoted mice was treated with LPS. ns stood for no statistical difference between the two groups. Blots are representative of n = 6 biological replicates.

Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the role of Piezo1 in SIMD and its underlying mechanisms. Our findings suggested that: (1) myocardial Piezo1 expression was upregulated following LPS administration; (2) cardiomyocyte-specific Piezo1 depletion exacerbated myocardial dysfunction; and (3) Piezo1 might exert protective effects through upregulation of DUSP3 in SIMD.

Sepsis, characterized as a systemic inflammatory response syndrome triggered by infection, frequently led to multiple organ dysfunction and remained a leading cause of mortality in critically ill patients. While cardiac involvement was common, the precise mechanisms underlying myocardial dysfunction in sepsis remained elusive, potentially involving myocardial damage, sympathetic activation, mitochondria, and calcium imbalance22,27,28. Among these factors, disruption of calcium homeostasis had emerged as a crucial pathophysiological basis for SIMD29. Piezo1, a mechanosensitive ion channel, could initiate downstream calcium signaling pathways and modulate cell function30, suggesting a potential role in SIMD. Our study demonstrated elevated Piezo1 levels in the murine heart following LPS treatment. Moreover, Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibited decreased myocardial function and more severe histological damage compared to controls, suggesting that Piezo1 might be integral to maintaining myocardial function during sepsis.

Previous research has shown that Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibited normal cardiac function at 8 weeks of age, but developed significant LVEF% decline by 18 weeks21. Our findings aligned with these observations, though we detected a decline in cardiac function decline in Piezo1ΔCM mice at an earlier age of 10 weeks. This discrepancy might be attributed to differences in gene knockout strategies; our study employed the Myh6-Cre system, while the previous study utilized the MLC2v-Cre system. The choice of promoter and the timing of Cre expression could influence the onset and severity of phenotypes in conditional knockout models31. Despite this variation in age of onset, both studies underscored the critical role of Piezo1 in maintaining normal cardiac function, with our findings further supporting the notion that Piezo1 deficiency could lead to impaired cardiac performance.

Several studies have implicated Piezo1 in regulating cardiac remodeling through its effects on calcium homeostasis. Piezo1 channels could sense mechanical stimuli within cardiomyocytes, such as tension changes during contraction and relaxation. These mechanical stimuli activated Piezo1, triggering downstream calcium signaling pathways and influencing cardiomyocyte contractility16. In SIMD, impaired cardiomyocyte contractility might be linked to Piezo1 channel dysfunction. Additionally, Piezo1 might directly contribute to the intricate regulation of calcium homeostasis within cardiomyocytes, serving as a protective mechanism against calcium overload and cellular injury21. By precisely modulating calcium influx and efflux, Piezo1 helped maintain intracellular calcium levels within a physiological range, preserving cardiomyocyte integrity and function21. The dual roles of Piezo1 as a mechanical sensor and calcium homeostasis regulator highlighted its importance in safeguarding cardiac health and preventing adverse remodeling. Notably, our results demonstrated that modulating Piezo1 activity through Yoda1 or GsMTx-4 significantly impacted cardiac function in SIMD mice, suggesting that these effects might stem from the precise regulation of Piezo1-mediated fluctuations in Ca2+ influx18.

Recent studies have reported a robust association between DUSP3 and sepsis, with DUSP3 inhibition effectively protecting female mice from sepsis and septic shock32,33. In our investigation, we observed upregulation of DUSP3 expression across Piezo1flox/flox + LPS, Piezo1ΔCM and Piezo1ΔCM + LPS groups, suggesting a potential mechanistic link between Piezo1 and DUSP3 in SIMD. However, the precise molecular mechanism by which Piezo1 regulated DUSP3 remained unclear. Specifically, our experiments did not determine whether Piezo1 directly interacts with DUSP3 or indirectly modulates DUSP3 activity through a mediating mechanism. Based on recent studies, we propose a hypothesis that Piezo1 may act as a mechanoreceptor, transducing signals from extracellular matrix stiffness to activate histone methyltransferases. This activation could increase H3K36me2 deposition, potentially enhancing RNA polymerase II accessibility at the DUSP3 locus and thereby boosting its transcriptional efficiency34. Nevertheless, this hypothesis requires experimental validation.

While our study provided new insights into the protective role of Piezo1 in SIMD and its potential mechanism through DUSP3 regulation, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, the molecular mechanisms underlying the directly or indirectly regulatory effects of Piezo1 on the DUSP3 protein expression are not comprehensively addressed in present study, which not only constitutes the principal limitation of this work but also defines the foremost research priority for our subsequent investigations. Secondly, it is important to note that our study exclusively used female mice, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to male animals. In future experiments, we plan to investigate whether Piezo1ΔCM mice exhibit sex-specific differences in the regulation of DUSP3 protein. Thirdly, the underlying cause for increased Piezo1 protein expression in cardiac tissue following LPS stimulation required further investigation. These aspects necessitated additional exploration to fully delineate the signaling pathways involved. Our current experiments served as an initial step in understanding this complex relationship, and further studies are essential to unravel the intricate mechanisms at play. It was important to note that sepsis and myocardial dysfunction involved multiple factors and complex signaling cascades. Future research should adopt a more comprehensive approach, considering the interplay of various factors to provide a more holistic understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying SIMD. Finally, although our findings highlighted Piezo1 as a potential therapeutic target for SIMD, it was crucial to emphasize that Piezo1-based therapies required extensive preclinical and clinical development to establish their safety profile and efficacy. Further investigations should focus on translating these findings into clinically viable treatment strategies, taking into account potential off-target effects and long-term consequences of Piezo1 modulation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed that Piezo1 exerted a cardioprotective effect in SIMD, potentially through the upregulation of DUSP3.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Project of Hebei Natural Science Foundation (No. H2021206205), the S&T Program of Hebei (No.22377728D) and the Program for Excellent Talents in Clinical Medicine of Hebei Province (No. ZF2023148). We sincerely thank Professor Xu Teng for his English language editing expertise, which significantly enhanced the manuscript’s clarity and readability.

Author contributions

Bing Xiao contributed to the research design. Angwei Gong, Jing Dai and Yan Zhao contributed to data collection, data processing and graphing. Haijuan Hu, Chengjian Guan, Hangtian Yu and Sheng Jin contributed data proofreading and analysis. Angwei Gong contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Xiao Bing and Yuming Wu contributed to review and to edit. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

ARRIVE guidelines statement

The study was designed and conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Angwei Gong and Jing Dai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuming Wu, Email: wuym@hebmu.edu.cn.

Bing Xiao, Email: xiaobing@hebmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Huang, M., Cai, S. & Su, J. The pathogenesis of Sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 5376 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Font, M. D., Thyagarajan, B. & Khanna, A. K. Sepsis and septic shock—basics of diagnosis, pathophysiology and clinical decision making. Med. Clin. N. Am.104, 573–585 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, D. et al. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: mechanisms, diagnosis and current treatment options. Military Med. Res.9, 56 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleischmann, C. et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of Hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med.193, 259–272 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakobsson, G. et al. Therapeutic S100A8/A9 Blockade inhibits myocardial and systemic inflammation and mitigates sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. Crit. Care. (Lond., Engl.)27, 374 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou, R. et al. DNA-PKcs promotes sepsis-induced multiple organ failure by triggering mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Adv. Res.41, 39–48 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakihana, Y., Ito, T., Nakahara, M., Yamaguchi, K. & Yasuda, T. Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction: pathophysiology and management. J. Intensive Care. 4, 22 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang, X. et al. Structure, kinetic properties and biological function of mechanosensitive piezo channels. Cell. Biosci.11, 13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saotome, K. et al. Structure of the mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1. Nature554, 481–486 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinge, S. et al. Emerging Piezo1 signaling in inflammation and atherosclerosis; a potential therapeutic target. Int. J. Biol. Sci.18, 923–941 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai, A. et al. Mechanosensing by Piezo1 and its implications for physiology and various pathologies. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc.97, 604–614 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang, Y. et al. Piezo1-Mediated mechanotransduction promotes cardiac hypertrophy by impairing calcium homeostasis to activate Calpain/Calcineurin signaling. Hypertens. (Dallas Tex. : 1979)78, 647–660 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang, J. et al. Stretch-activated channel Piezo1 is up-regulated in failure heart and cardiomyocyte stimulated by AngII. Am. J. Transl Res.9, 2945–2955 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolland, L. et al. Prolonged Piezo1 activation induces cardiac arrhythmia. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 6720 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu, H. et al. Dexamethasone upregulates macrophage PIEZO1 via SGK1, suppressing inflammation and increasing ROS and apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol.222, 116065 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotts, J. E., Michael, A. & Matthay Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.).353, i1585 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Faix, J. D. Biomarkers of sepsis. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci.50, 23–36 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velasco-Estevez, M., Rolle, S. O., Mampay, M., Dev, K. K. & Sheridan, G. K. Piezo1 regulates calcium oscillations and cytokine release from astrocytes. Glia68, 145–160 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, Y. et al. Immunoregulatory role of the mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 in inflammation and Cancer. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 28, 213 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, H. et al. Piezo1 channels as force sensors in mechanical force-related chronic inflammation. Front. Immunol.13, 816149 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang, F. et al. The mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel mediates heart mechano-chemo transduction. Nat. Commun.12, 869 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan, X., Liu, R., Xi, Y. & Tian, Z. The mechanisms of exercise improving cardiovascular function by stimulating Piezo1 and TRP ion channels: a systemic review. Mol. Cell. Biochem.10.1007/s11010-024-05000-5 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Q. et al. Piezo1 alleviates acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by activating Nrf2 and reducing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.652, 88–94 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ihara, T. et al. Different effects of GsMTx4 on nocturia associated with the circadian clock and Piezo1 expression in mice. Life Sci.278, 119555 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertani, B. & Ruiz, N. Function and Biogenesis of Lipopolysaccharides. EcoSal Plus8, ESP-0001-2018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Shvilkina, T. & Shapiro, N. Sepsis-Induced myocardial dysfunction: heterogeneity of functional effects and clinical significance. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10, 1200441 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonucci, E. et al. Myocardial depression in sepsis: from pathogenesis to clinical manifestations and treatment. J. Crit. Care. 29, 500–511 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuji, N. et al. BAM15 treats mouse sepsis and kidney injury, linking mortality, mitochondrial DNA, tubule damage, and neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig.133, e152401 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan, Z., Niu, L., Wang, S., Gao, C. & Pan, S. Intestinal Piezo1 aggravates intestinal barrier dysfunction during sepsis by mediating Ca2+ influx. J. Transl. Med.22, 332 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atcha, H. et al. Mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1 modulates macrophage polarization and stiffness sensing. Nat. Commun.12, 3256 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le, Y. & Sauer, B. Conditional gene knockout using Cre recombinase. Mol. Biotechnol.17, 269–275 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao, Y., Yu, W. & Cai, H. Dehydroandrographolide facilitates M2 macrophage polarization by downregulating DUSP3 to inhibit sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Immun. Inflamm. Dis.12, e1249 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandereyken, M. M. et al. Dual-Specificity phosphatase 3 deletion protects female, but not male, mice from Endotoxemia-Induced and Polymicrobial-Induced septic shock. J. Immunol.199, 2515–2527 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal, S., Kabeer, S. W., Sharma, S. & Tikoo, K. l-Methionine potentiates anticancer activity of Sorafenib by epigenetically altering DUSP3/ERK pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol.38, e23663 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.