Abstract

Macrolide resistance is the ability of bacteria to survive the effects of macrolide antibiotics, which include drugs such as erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. Efforts to combat resistance mechanisms like this frequently involve the discovery and development of new antibiotics or therapeutic strategies capable of overcoming these modifications and restoring the efficacy of current antibiotics. In this study, we explored natural products against enzymes of macrolide resistance Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I (mphA or ErmE), Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II (mphB), Tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, Erythromycin esterase EreC, and rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) by molecular modelling techniques. The standard precision protocol of the Glide tool was utilized to dock a library of 1,400 natural product compounds from the LOTUS database against various enzymes associated with macrolide resistance. The docking results were assessed using the glide score, and the top ten compounds that were docked to each receptor were selected. Additionally, these selected compounds underwent ADMET analysis, suggesting their potential for therapeutic development. Among the selected compounds, LTS0271681 showed the highest binding affinity against ErmAM, LTS0263188 showed highest binding affinity against Tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, LTS0024216 showed the highest binding affinity against mphA, LTS0110759 showed the highest binding affinity against mphB, and LTS0100971 showed the highest binding affinity against EreC. The study incorporated molecular dynamic simulations and MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations to enhance the docking experiments. The results indicate that these compounds could potentially serve as inhibitors of macrolide resistance. However, while computational validations were part of this research, additional in-vitro studies are necessary to develop these potential inhibitors into therapeutic drugs.

Keywords: Macrolide resistance, Virtual screening, ADMET, Molecular docking, MD simulation

Subject terms: Biophysics, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery

Introduction

Macrolides are a class of antibiotics with a distinctive structure distinguished by a macrocyclic lactone ring, which gives them their name. Macrolide antibiotics are macrocyclic lactones having a 12–16 carbon lactone ring that are attached to a number of amino groups and/or neutral sugars. These antibiotics are frequently used to treat a wide variety of bacterial infections, including skin infections, respiratory tract infections, and several sexually transmitted diseases. Erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin are a few well-known macrolide antibiotics1,2.

While macrolides have been quite efficient in treating bacterial infections, the advent of antibiotic resistance has called into question their clinical value. Bacteria have evolved several resistance mechanisms against macrolides. Among the resistance mechanisms include efflux pumps, ribosomal modifications, enzymatic degradation, changes in the ribosomal target site, and others. These mechanisms have the potential to render antibiotics ineffective and contribute to the evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains3,4.

Statistical analysis of macrolide resistance reveals significant differences between gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Gram-positive species, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, have historically been more resistant to macrolides due to the prevalence of mechanisms such as enzymatic inactivation (e.g., esterases) and target site modifications (e.g., rRNA methyltransferases). However, increasing rates of macrolide resistance have been observed in Gram-negative bacteria, particularly in clinically relevant pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae species, which can be attributed to resistance gene acquisition via horizontal gene transfer and efflux pump overexpression. Although there has historically been a correlation between higher rates of macrolide resistance in Gram-positive bacteria and resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria, surveillance and customized treatment approaches are crucial in addressing resistance trends in both bacterial groups5–7. Researchers are always attempting to understand the mechanisms of resistance and devise strategies to overcome it.

Researchers can create a repertoire of inhibitors that work through various mechanisms by targeting multiple enzymes involved in macrolide resistance. This strategy reduces the likelihood of resistance development while increasing the chances of success in overcoming resistance in a variety of bacterial strains. Each enzyme provides macrolide resistance through different mechanisms. Investigating multiple resistance mechanisms provides a comprehensive understanding of how bacteria avoid macrolide antibiotics8–10. Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I (also known as mphA or ErmE) and Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II (also known as mphB) are enzymes that play an important role in imparting resistance to macrolide antibiotics in bacteria. Both are found in Gram-negative bacteria, particularly those of the Enterobacteriaceae family. mphA confers resistance to macrolide antibiotics by phosphorylating the 2’-OH group of macrolides, preventing them from binding to the bacterial ribosome and inhibiting the synthesis of proteins. Like Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I, mphB confers resistance to macrolide antibiotics by phosphorylating macrolides’ 2’-OH group, rendering them inactive. However, with the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and horizontal gene transfer, the distinctions between resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria can sometimes blur, and genes such as mphA or mphB can occasionally be found in Gram-positive species through genetic exchange. The advent and abundance of enzymes such as Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I and macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II contribute to the broader challenge of antibiotic resistance9,11.

A tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump is a combination of three proteins that actively pump macrolide antibiotics out of bacterial cells, contributing to antibiotic resistance. These efflux pumps have been extensively studied in Gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae species such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The macrolide-specific efflux pump is composed of three major components: Inner Membrane Transporter (MacA or MacB); Periplasmic Adapter Protein (MacA or MacB): and Outer Membrane Channel (MacA or MacB). The combined activity of these three proteins generates a mechanism for macrolide antibiotics to be easily taken from the bacterial cell, lowering the concentration of the antibiotic, and thus decreasing its capacity to suppress bacterial growth. This efflux pump-mediated resistance is one method by which bacteria might gain resistance to antibiotics such as macrolides12–14.

The Esterase EreC, also known as erythromycin esterase, is primarily found in Gram-positive bacteria. It is found in many Staphylococcus species, including Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. EreC confers resistance to macrolide antibiotics, such as erythromycin, by hydrolyzing the antibiotic’s lactone ring, deactivating its antimicrobial activity15.

rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) is a bacterial enzyme that belongs to the methyltransferase family. ErmAM and other rRNA methyltransferases have been extensively studied in Gram-positive bacteria, particularly those from the genera Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Enterococcus. While rRNA methyltransferases are most commonly found in Gram-positive bacteria, they have also been reported in Gram-negative bacteria. This enzyme is essential for bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin (MLS) antibiotics. These antibiotics target the bacterial ribosome, which is responsible for protein synthesis. Understanding the structure, function, and mechanism of enzymes such as ErmAM is critical in the ongoing fight against antibiotic resistance16.

Natural products, which are compounds derived from plants, microorganisms, or other natural sources, have shown potential in inhibiting these resistance mechanisms. While natural products have the potential to target macrolide resistance pathways, research in this field is continuing, and not all natural products will be beneficial. Furthermore, the development of new antibiotics and resistance-fighting tactics should be conducted concurrently with the exploration of natural compounds17,18.

Despite the availability of several in-vitro drug development approaches for screening numerous components against a pre-identified target, the process remains costly and time-consuming. Thus, molecular docking is an alternative technique that presents every possible ligand site before choosing the best one. Molecular docking is a computational technique used to aid in the prediction and conformation of a receptor-ligand complex, where the ligand is a small molecule, and the receptor is a nucleic acid or protein. This docking approach has the potential to generate several ligand binding sites in the receptor binding compartment19–21. The dynamics, stability, and binding affinity of protein-ligand interactions can be studied using MD simulation and MMGBSA analysis of docked complexes. They aid in the refinement of docking predictions, the ranking of ligand candidates, the direction of future optimization efforts, and the expansion of our understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind protein-ligand binding22. Thus, the purpose of this study is to use molecular docking, ADMET, and molecular dynamics simulation analyses to explore natural products against enzymes of macrolides resistance.

Methodology

Ligand preparation

The natural compounds obtained from LOTUS database were processed using the LigPrep program in Schrödinger’s Maestro23. The LOTUS initiative is designed to be an open and comprehensive repository for natural product structures and occurrence data. According to Rutz et al. (2021) in The LOTUS Initiative for Open Natural Products Research: Knowledge Management through Wikidata, LOTUS provides rigorously curated data, integrating information from various sources and making it accessible via Wikidata40. OPLS_2005 force field was used to optimize the geometry of the ligands, ensuring they achieved energetically favorable conformations24. Energy minimization was applied to remove any unfavorable interactions or strained geometries.

Molecular docking and ADMET analysis

The goal of this study is to elucidate the virtual screening of the natural products against different enzymes of macrolide resistance and find the most suitable hits that can be pushed towards the wet lab studies to inhibit macrolide resistance. The proteins used in this study were Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I (PDB ID: 5IGH, resolution: 1.55 Å, Method: X-ray diffraction)25, Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II (PDB ID: 5IGU, resolution: 2.10 Å, Method: X-ray diffraction)25, tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump (PDB ID: 3FPP, resolution: 2.99 Å, Method: X-ray diffraction)26, Erythromycin esterase EreC (PDB ID: 6XCQ, resolution: 2.0 Å, Method: X-ray diffraction)27, and rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) (PDB ID: 1YUB, Method: NMR)28. The proteins were prepared for the docking using Protein Preparation Wizard29. During receptor preparation, several stages were done including the generation of disulfide bonds, assignment of zero-order metal bonds, and addition of hydrogens. The additional ligands and crystal water were also removed. In the optimization step, the pKa values of ionizable group were optimized at pH 7.0 utilizing the PROPKA program30. Grid box dimensions for PBD:5IGH were X = 16.77, Y = 39.58, and Z = 36.61, for PBD:5IGU were X = 45.36, 24.72, Y = 24.72, and Z = 29.85, for PBD:3FPP were X= -51.8, Y = 23.5, and Z = 18.88, for PDB:6XQC were X = 40.8, Y = 24.86, Z = 31.89, and for PDB:1YUB grid dimensions were set to X = = 13.73, Y = 6.46, Z = 5.33. The size of Grid box was 10 Å for all receptors. Finally, the OPLS_2005 forcefield was used for energy minimization. Following protein preparation, 3D grids were constructed at predicted binding sites. The binding sites were predicted by SiteMap tool in all receptors31. The prepared natural compounds were docked to the protein using SP mode of glide32. Further, the ADMET profiles and physicochemical properties of the docked compounds were analyzed by QikProp tool33.

MD simulation

The complexes was analyzed for protein confirmation and ligand stability by running a simulation of 200 ns by using Desmond34. The systems were solvated by placing them in an orthorhombic box of 10 Å, filled with TIP3P water model35. To replicate physiological conditions, counter ions were added for neutralization, and 0.15 M NaCl salt was incorporated. The temperature and pressure of the system was set to 300 K and 1 atm respectively by using NPT ensemble. After a relaxation phase, the production run was started to record the trajectories after 50 ps time interval. The simulation interaction diagram module of Desmond was used to analyze the trajectories. The MM-GBSA approach was used to assess the best-docked conformation’s total binding free energy in order to calculate its strength and stability.

Results

Molecular docking and ADMET analysis

Macrolide antibiotics have long been used to treat bacterial infections, although resistance has hampered their effectiveness. In a novel strategy to address the growing concern of antibiotic resistance, researchers are using computational approaches to uncover natural compounds capable of tackling several pathways of macrolide resistance36. The purpose of this work is to elucidate the virtual screening of natural products against different enzymes of macrolide resistance and find the most relevant hits. The LOTUS database provided the natural product structures. Crystal structures of 1YUB, 3FPP, 5IGH, 5IGU, and 6XCQ were found using the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

While databases such as ZINC, PubChem, and NPASS are valuable for large-scale compound collections, LOTUS specifically emphasizes the accurate annotation of natural products. Its focus on the chemical diversity found in nature and on rigorous curation methods means that the compounds retrieved are less likely to include synthetic or redundant entries. The natural compounds were docked against different enzymes of macrolide resistance using the standard precision protocol of the Glide tool. The docking results were assessed using the Glide score, and the top 10 compounds that docked with each receptor were selected (Table 1). Two control compounds, 12-membered (Methymycin) and 15‐membered (Azithromycin) were also docked to the receptors. In rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) docking analysis, the controls showed binding affinities in the range of -4.87 to -3.52, while the selected natural products showed affinities in the range of -9.39 to -8.71 kcal/mol. For tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, the docking scores of controls were in the range of -3.78 to -3.02 and the docking scores of selected products were − 6.28 to -5.74 kcal/mol. In the case of Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I protein, the hits showed the binding affinities ranging from − 8.18 to -6.76 which were better than the controls binding affinities. Similarly, hits showed better affinities against the Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II and Erythromycin esterase EreC than the controls. Additionally, physicochemical and ADMET profiles of the selected natural compounds were predicted which showed one or two violations of rule of 5. However, the other properties met the threshold values in the following manner: “QPlogHERG” (less than − 5) indicating a low propensity for hERG channel inhibition. This is crucial for minimizing potential cardiotoxic effects in subsequent in vivo studies. “QPlogPo/w” (between − 2.0 and 6.5) suggest that the compounds possess balanced lipophilicity. This is important for membrane permeability and oral bioavailability, as overly lipophilic compounds may have solubility issues, while highly hydrophilic compounds may exhibit poor cell penetration. “QPPCaco” (poor if less than 25 and great if more than 500), The QPPCaco values indicate that the majority of compounds have moderate to high permeability across intestinal epithelial cells. This supports the likelihood of efficient gastrointestinal absorption, a desirable characteristic for orally administered agents. “QPlogKhsa” (between − 1.5 and 1.5) and “QPlogBB” (between − 3.0 and 1.2) suggest a balanced distribution between blood and brain compartments, which is significant for avoiding unwanted central nervous system effects. Meanwhile, QPlogKhsa values within the acceptable range imply favorable serum albumin binding, ensuring an adequate free drug fraction in plasma. (Table 2).

Table 1.

The selected natural compounds and their Docking scores against each enzyme.

| No. | Compounds | SMILES | Glide Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) (1YUB) | |||

| 1 | LTS0271681 | CC(= O)OC[C@@H]1O[C@@H](c2c(O)cc(O)c3c(= O)cc(-c4ccc(O)cc4)oc23)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]1O | -9.394 |

| 2 | LTS0185946 | COc1cc(-c2oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c(= O)c2OC2OC(COC(C) = O)C(O)C(O)C2O)ccc1O | -9.218 |

| 3 | LTS0008706 | CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](c2c(O)cc(O)c3c(= O)cc(-c4ccc(O)c(O)c4)oc23)[C@H](OC(C) = O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -9.192 |

| 4 | LTS0029004 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OCC1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)c(O)c2)C(O)C(O)[C@@H]1O | -9.074 |

| 5 | LTS0236079 | CC(= O)OC[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2c(-c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c2 = O)[C@H](O)[C@H]1O | -9.063 |

| 6 | LTS0150761 | C[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2c(-c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c2 = O)[C@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]1OC(= O)CC(= O)O | -9.05 |

| 7 | LTS0092860 | O = C(O)/C = C\c1ccc(O[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(= O)c3cc(O)c(O)c(O)c3)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]2O)cc1 | -8.951 |

| 8 | LTS0261418 | CC1CCC(C(COC2OC(COC(= O)C = Cc3ccccc3)C(O)C(O)C2O)C(= O)O)C1C(= O)O | -8.885 |

| 9 | LTS0044200 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OCC1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)cc2)C(O)C(O)[C@@H]1O | -8.752 |

| 10 | LTS0242752 | CC(= O)OC[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2c(-c3ccc(O)cc3)oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c2 = O)[C@H](O)[C@H]1O | -8.718 |

| 11 | *Methymycin | CCC1C(C = CC(= O)C(CC(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2C(C(CC(O2)C)N(C)C)O)C)C)(C)O | -4.872 |

| 12 | *Azithromycin | CCC1C(C(C(N(CC(CC(C(C(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2CC(C(C(O2)C)O)(C)OC)C)OC3C(C(CC(O3)C)N(C)C)O)(C)O)C)C)C)O)(C)O | -3.526 |

| Tripartite Macrolide-specific Efflux Pump (3FPP) | |||

| 1 | LTS0263188 | O = C(OC[C@@]1(O)CO[C@@H](O[C@H]2[C@H](Oc3ccc(CO)cc3)O[C@H](CO)[C@H](O)[C@@H]2O)[C@@H]1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -6.28 |

| 2 | LTS0044020 | C[C@H]1OC(= O)C[C@@H]2 C(C(= O)O) = CO[C@@H](O[C@@H]3O[C@H](COC(= O)/C = C/c4ccc(O)cc4)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]3O)[C@@H]21 | -6.119 |

| 3 | LTS0138804 | O = C1C = CC(O)(CCOC2OC(COC(= O)CC3(O)C = CC(= O)C = C3)C(O)C(O)C2O)C = C1 | -6.071 |

| 4 | LTS0151403 | CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)cc(O)c2C(= O)CCc2ccc(O)cc2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@H]1O | -6.046 |

| 5 | LTS0165780 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)cc3oc(-c4ccc(O)cc4)cc(= O)c23)[C@@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -5.999 |

| 6 | LTS0196533 | COc1cc(-c2oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c(= O)c2O[C@H]2O[C@@H](COC(C) = O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]2O)ccc1O | -5.929 |

| 7 | LTS0155227 | O = C(OCC1(O)COC(OC2C(Oc3ccc(O)cc3)OC(CO)C(O)C2O)C1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -5.845 |

| 8 | LTS0090062 | COc1cc(O[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(= O)CC(= O)O)[C@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@@H]2O)c2c(= O)cc(-c3ccc(O)cc3)oc2c1 | -5.782 |

| 9 | LTS0153718 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)cc3oc(-c4ccc(O)c(O)c4)cc(= O)c23)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -5.758 |

| 10 | LTS0150030 | O = C(OCC1OC(OC2C(O)C(CO) = C(CO)C2CCO)C(O)C(O)C1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -5.745 |

| 11 | *Methymycin | CCC1C(C = CC(= O)C(CC(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2C(C(CC(O2)C)N(C)C)O)C)C)(C)O | -3.781 |

| 12 | *Azithromycin | CCC1C(C(C(N(CC(CC(C(C(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2CC(C(C(O2)C)O)(C)OC)C)OC3C(C(CC(O3)C)N(C)C)O)(C)O)C)C)C)O)(C)O | -3.02 |

| Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I (5IGH) | |||

| 1 | LTS0024216 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)cc2)[C@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -8.186 |

| 2 | LTS0142659 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)c(O)c2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -7.468 |

| 3 | LTS0257496 | O = C(O)CCC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)cc2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -7.122 |

| 4 | LTS0178696 | C[C@H]1CC[C@H]([C@@H](CO[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(= O)/C = C/c3ccccc3)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]2O)C(= O)O)[C@H]1 C(= O)O | -7.102 |

| 5 | LTS0261807 | C[C@H]1CC[C@H]([C@@H](CO[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(= O)/C = C\c3ccccc3)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]2O)C(= O)O)[C@H]1 C(= O)O | -6.989 |

| 6 | LTS0186341 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)c(O)c2)[C@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -6.911 |

| 7 | LTS0015626 | COc1cc(-c2[o+]c3cc(O)cc(O)c3cc2O[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(C) = O)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]2O)cc(O)c1O | -6.889 |

| 8 | LTS0074794 | O = C(O[C@H]1[C@H](Oc2cc(O)cc(/C = C/c3ccc(O)cc3)c2)O[C@H](CO)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -6.856 |

| 9 | LTS0033334 | CC(= O)CCc1ccc(O)c(O[C@@H]2O[C@H](COC(= O)/C = C/c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]2O)c1 | -6.783 |

| 10 | LTS0069049 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)cc2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -6.76 |

| 11 | *Azithromycin | CCC1C(C = CC(= O)C(CC(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2C(C(CC(O2)C)N(C)C)O)C)C)(C)O | -6.808 |

| 12 | *Methymycin | CCC1C(C(C(N(CC(CC(C(C(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2CC(C(C(O2)C)O)(C)OC)C)OC3C(C(CC(O3)C)N(C)C)O)(C)O)C)C)C)O)(C)O | -4.451 |

| Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II (5IGU) | |||

| 1 | LTS0110759 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3oc(-c4ccccc4)cc(= O)c3c(O)c2O)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -7.914 |

| 2 | LTS0146815 | O = C(OCC1OC(Oc2cc(O)cc(O)c2C(= O)c2ccc(O)cc2)C(O)C(O)C1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -7.661 |

| 3 | LTS0021802 | O = C(OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](O[C@H]2CCC(= O)c3ccc(O)cc32)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O)c1cc(O)c(O)c(O)c1 | -7.655 |

| 4 | LTS0108229 | O = C(OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)cc(O)c2C(= O)c2ccc(O)cc2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -7.588 |

| 5 | LTS0001939 | CC1(O)C(O)CC2C(C(= O)O) = COC(OC3OC(COC(= O)C = Cc4ccc(O)cc4)C(O)C(O)C3O)C21 | -7.483 |

| 6 | LTS0150761 | C[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2c(-c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c2 = O)[C@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]1OC(= O)CC(= O)O | -7.331 |

| 7 | LTS0044200 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OCC1O[C@@H](Oc2cc3c(O)cc(O)cc3[o+]c2-c2ccc(O)cc2)C(O)C(O)[C@@H]1O | -7.26 |

| 8 | LTS0088373 | O = C1C = C2CC[C@H](O[C@@H]3O[C@H](COC(= O)c4cc(O)c(O)c(O)c4)[C@@H](O)[C@H](O)[C@H]3O)C[C@@H]2O1 | -7.253 |

| 9 | LTS0121375 | CC[C@H](C)C(= O)OC[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)c3c(= O)cc(-c4ccc(O)c(O)c4)oc3c2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -7.205 |

| 10 | LTS0012870 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OCC1OC(Oc2cc(O)c3c(= O)cc(-c4ccc(O)cc4)oc3c2)C(O)C(O)C1O | -7.157 |

| 11 | *Azithromycin | CCC1C(C = CC(= O)C(CC(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2C(C(CC(O2)C)N(C)C)O)C)C)(C)O | -5.897 |

| 12 | *Methymycin | CCC1C(C(C(N(CC(CC(C(C(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2CC(C(C(O2)C)O)(C)OC)C)OC3C(C(CC(O3)C)N(C)C)O)(C)O)C)C)C)O)(C)O | -5.371 |

| Erythromycin esterase EreC (6XCQ) | |||

| 1 | LTS0100971 | CC(= O)OCC1OC(Oc2ccc(C(= O)C = Cc3ccc(O)c(O)c3)c(O)c2O)C(O)C(O)C1O | -6.703 |

| 2 | LTS0145586 | CC(= O)OCC1OC(Oc2ccc(C(= O)C = Cc3ccc(O)c(O)c3)c(O)c2O)C(O)C(OC(C) = O)C1O | -6.473 |

| 3 | LTS0057711 | CC(= O)OC[C@@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2ccc(C(= O)/C = C/c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)c(O)c2O)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1OC(C) = O | -6.437 |

| 4 | LTS0022136 | O = C(C = Cc1ccc(O)cc1)OCC1OC(Oc2cc(O)cc(C = Cc3ccc(O)cc3)c2)C(O)C(O)C1O | -6.36 |

| 5 | LTS0266290 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)c3c(= O)cc(-c4ccc(O)c(O)c4)oc3c2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -6.313 |

| 6 | LTS0083700 | CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@H](Oc2c(-c3ccc(O)c(O)c3)oc3cc(O)cc(O)c3c2 = O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1OC(C) = O | -6.284 |

| 7 | LTS0057914 | CC(= O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](c2c(O)cc3oc(-c4ccc(O)c(O)c4)cc(= O)c3c2O)[C@H](OC(C) = O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -6.198 |

| 8 | LTS0163007 | O = C(/C = C/c1ccc(O)cc1)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](OOCCc2ccc(O)c(O)c2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O | -6.122 |

| 9 | LTS0068514 | O = C(OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](Oc2cc(O)cc(/C = C/c3ccc(O)cc3)c2)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O)c1ccc(O)cc1 | -6.119 |

| 10 | LTS0211996 | O = C(O)CC(= O)OCC1OC(Oc2ccc3c(= O)c(-c4ccc(O)cc4)coc3c2)C(O)C(O)C1O | -6.102 |

| 11 | *Azithromycin | CCC1C(C = CC(= O)C(CC(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2C(C(CC(O2)C)N(C)C)O)C)C)(C)O | -5.676 |

| 12 | *Methymycin | CCC1C(C(C(N(CC(CC(C(C(C(C(C(= O)O1)C)OC2CC(C(C(O2)C)O)(C)OC)C)OC3C(C(CC(O3)C)N(C)C)O)(C)O)C)C)C)O)(C)O | -3.583 |

*Control.

Table 2.

The ADMET profiles of the selected natural compounds predicted by QikProp.

| Compounds | MW | HBD | HBA | QPlogPo/w | QPlogHERG | QPPCaco | QPlogBB | QPlogKhsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) | ||||||||

| LTS0271681 | 474.42 | 5 | 12 | -0.169 | -5.617 | 4.947 | -3.437 | -0.49 |

| LTS0185946 | 520.446 | 5 | 14 | 0.097 | -6.141 | 5.542 | -3.94 | -0.589 |

| LTS0008706 | 532.457 | 5 | 13 | -0.092 | -5.658 | 2.723 | -3.967 | -0.444 |

| LTS0029004 | 535.41 | 8 | 13 | -2.88 | -6.738 | 4.645 | -4.494 | -0.534 |

| LTS0236079 | 476.393 | 5 | 12 | -0.088 | -5.708 | 3.093 | -3.868 | -0.496 |

| LTS0150761 | 534.429 | 5 | 13 | 0.023 | -3.87 | 0.128 | -4.779 | -0.642 |

| LTS0092860 | 478.409 | 7 | 13 | -0.656 | -3.992 | 0.239 | -4.79 | -1.051 |

| LTS0261418 | 508.521 | 5 | 14 | 1.084 | -1.611 | 0.669 | -3.416 | -1.054 |

| LTS0044200 | 519.43 | 7 | 13 | -2.34 | -2.492 | 2.224 | -5.479 | -0.131 |

| LTS0242752 | 460.393 | 4 | 11 | 0.429 | -5.903 | 5.467 | -3.583 | -0.368 |

| Tripartite Macrolide-specific Efflux Pump | ||||||||

| LTS0263188 | 538.504 | 7 | 17 | -1.041 | -7.037 | 3.092 | -4.889 | -1.223 |

| LTS0044020 | 536.488 | 5 | 17 | -0.573 | -4.466 | 0.802 | -4.296 | -1.234 |

| LTS0138804 | 466.441 | 4 | 15 | -0.343 | -5.233 | 19.241 | -2.938 | -0.961 |

| LTS0151403 | 478.452 | 5 | 12 | 0.171 | -6.498 | 3.673 | -4.496 | -0.655 |

| LTS0165780 | 518.43 | 5 | 14 | -0.146 | -4.341 | 0.349 | -4.462 | -0.874 |

| LTS0196533 | 520.446 | 5 | 14 | 0.072 | -5.501 | 12.209 | -3.218 | -0.635 |

| LTS0155227 | 524.477 | 7 | 16 | -0.672 | -6.486 | 9.499 | -3.834 | -1.093 |

| LTS0090062 | 532.457 | 4 | 14 | 0.665 | -4.306 | 1.097 | -3.92 | -0.748 |

| LTS0153718 | 534.429 | 6 | 15 | -0.892 | -4.456 | 0.074 | -5.543 | -0.997 |

| LTS0150030 | 486.472 | 8 | 18 | -2.006 | -4.754 | 3.832 | -3.87 | -1.29 |

| Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I | ||||||||

| LTS0024216 | 519.43 | 8 | 13 | -2.41 | -3.992 | 0.239 | -4.79 | -1.051 |

| LTS0142659 | 535.43 | 8 | 14 | -3.17 | -6.738 | 4.645 | -4.494 | -0.534 |

| LTS0257496 | 533.46 | 7 | 13 | -1.50 | -5.658 | 2.723 | -3.967 | -0.444 |

| LTS0178696 | 508.521 | 5 | 14 | 1.268 | -2.014 | 0.459 | -3.716 | -0.978 |

| LTS0261807 | 508.521 | 5 | 14 | 1.628 | -1.978 | 1.104 | -3.264 | -0.945 |

| LTS0186341 | 535.43 | 8 | 14 | -2.75 | -3.978 | 3.134 | -3.638 | -1.744 |

| LTS0015626 | 521.45 | 7 | 13 | -4.23 | -4.978 | 10.131 | -4.534 | -0.858 |

| LTS0074794 | 510.496 | 6 | 11 | 1.704 | -7.62 | 11.581 | -3.859 | -0.295 |

| LTS0033334 | 504.49 | 6 | 13 | -0.047 | -6.439 | 1.562 | -5.007 | -0.705 |

| LTS0069049 | 519.43 | 7 | 13 | -3.03 | -4.467 | 2.614 | -6.103 | -1.811 |

| Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II | ||||||||

| LTS0110759 | 518.43 | 4 | 13 | 0.416 | -4.407 | 0.401 | -4.443 | -0.715 |

| LTS0146815 | 528.468 | 6 | 13 | 0.283 | -6.88 | 3.45 | -4.356 | -0.63 |

| LTS0021802 | 492.435 | 7 | 15 | -1.604 | -5.169 | 1.394 | -4.176 | -0.927 |

| LTS0108229 | 528.468 | 6 | 13 | 0.195 | -6.52 | 2.29 | -4.388 | -0.583 |

| LTS0001939 | 538.504 | 7 | 17 | -0.686 | -4.275 | 0.623 | -4.495 | -1.221 |

| LTS0150761 | 534.429 | 5 | 13 | 0.163 | -3.947 | 0.242 | -4.505 | -0.671 |

| LTS0044200 | 519.43 | 7 | 13 | -2.34 | -3.627 | 0.345 | -3.465 | -1.374 |

| LTS0088373 | 468.413 | 6 | 15 | -1.906 | -4.52 | 2.266 | -3.713 | -1.002 |

| LTS0121375 | 532.5 | 5 | 13 | 0.652 | -5.219 | 6.358 | -3.471 | -0.358 |

| LTS0012870 | 518.43 | 4 | 13 | 0.529 | -4.271 | 0.594 | -4.161 | -0.709 |

| Erythromycin esterase EreC | ||||||||

| LTS0100971 | 492.435 | 6 | 13 | -0.58 | -6.305 | 1.256 | -5.028 | -0.82 |

| LTS0145586 | 534.473 | 5 | 13 | 0.143 | -6.587 | 1.156 | -5.322 | -0.587 |

| LTS0057711 | 534.473 | 5 | 13 | -0.019 | -6.207 | 0.915 | -5.134 | -0.591 |

| LTS0022136 | 536.534 | 6 | 11 | 1.03 | -5.301 | 5.182 | -3.61 | -0.35 |

| LTS0266290 | 534.429 | 5 | 14 | -0.513 | -4.618 | 0.054 | -5.814 | -0.855 |

| LTS0083700 | 518.43 | 4 | 12 | 0.566 | -5.598 | 4.003 | -3.725 | -0.307 |

| LTS0057914 | 532.457 | 5 | 13 | -0.054 | -5.859 | 1.864 | -4.202 | -0.403 |

| LTS0163007 | 478.452 | 6 | 14 | -0.206 | -7.036 | 5.815 | -4.483 | -0.977 |

| LTS0068514 | 510.496 | 6 | 11 | 1.341 | -7.25 | 7.494 | -4.011 | -0.349 |

| LTS0211996 | 502.431 | 4 | 13 | 0.568 | -4.792 | 1.116 | -4.048 | -0.816 |

| *Methymycin | 469.617 | 2 | 11 | 2.41 | -5 | 279.42 | -0.358 | 0.106 |

| *Azithromycin | 748.993 | 5 | 20 | 3.7 | -5.231 | 43.821 | -0.451 | -0.066 |

Molecular docking and Simulation analyses

The molecular docking interactions between natural product compounds and protein targets encompassing 1YUB, 3FPP, 5IGH, 5IGU and 6XCQ were analyzed by using Discovery studio. Based on the glide scores, LTS0271681, LTS0263188, LTS0024216, LTS0110759, and LTS0100971 were selected against the 1YUB, 3FPP, 5IGH, 5IGU and 6XCQ respectively to further investigation by MD simulation.

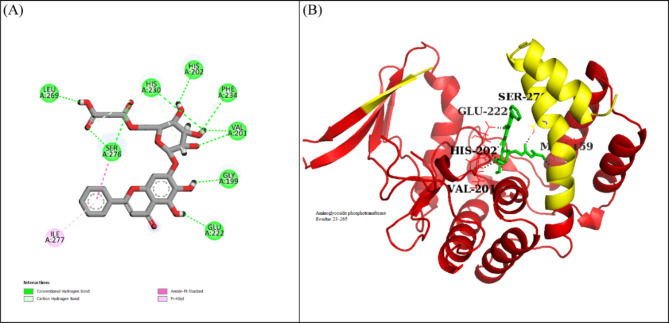

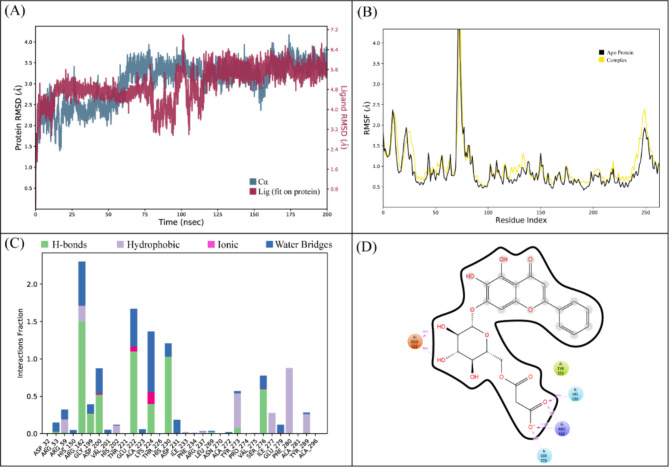

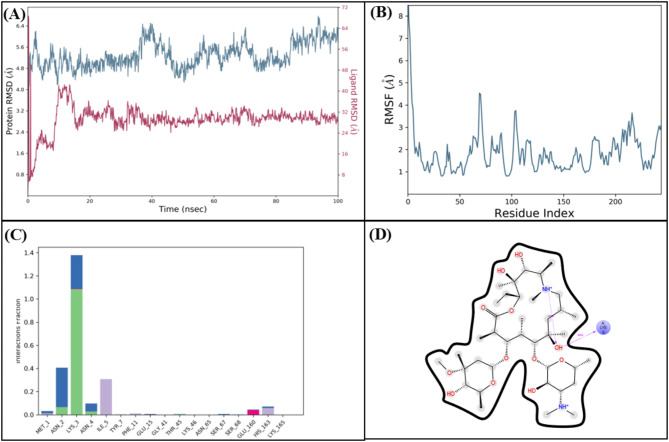

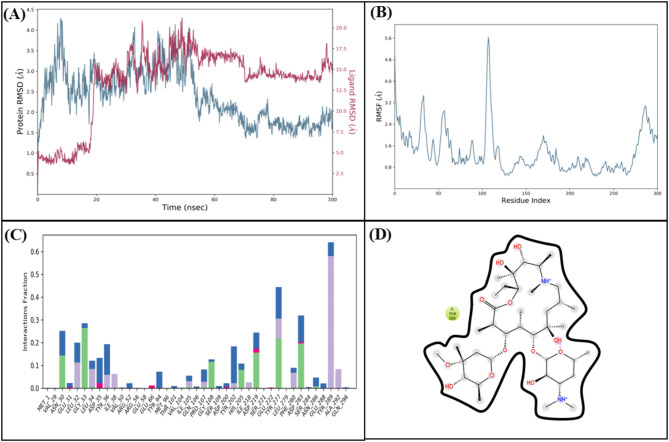

rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM)

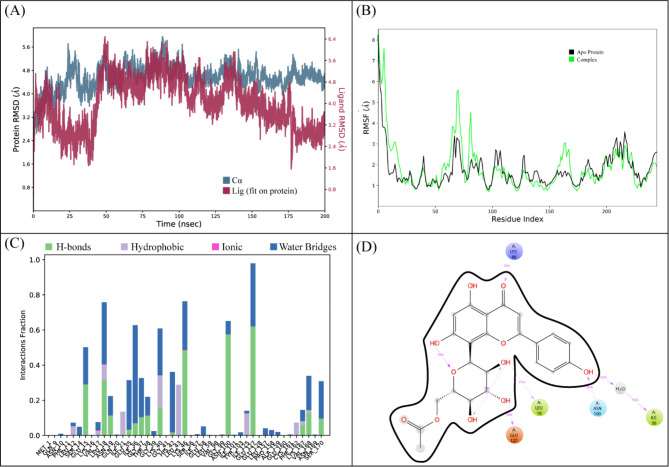

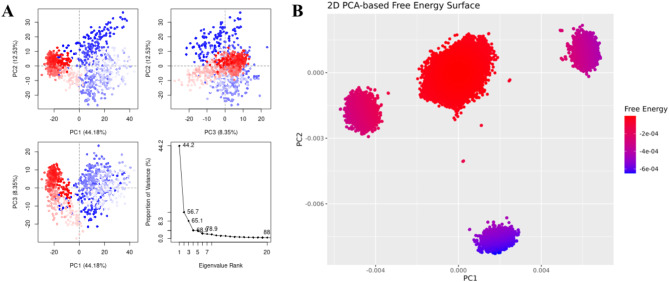

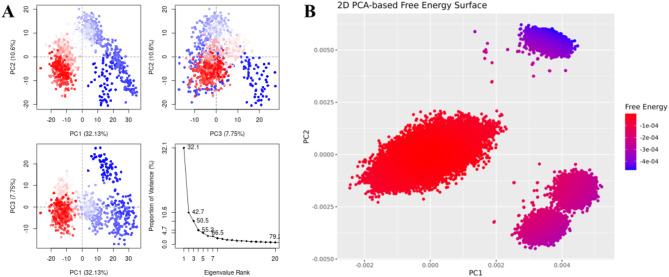

The highest binding affinity among all the natural compounds against rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) was shown by LTS0271681. The molecular interactions were analyzed, and it was observed that the compound made six hydrogen bonds with Gln35, Thr38, Lys40, Ser14, Asn100, and Glu127. It also made three hydrophobic interactions as shown in Fig. 1A. The compound was bound with the residues of Ribosomal RNA adenine methylase transferase domain (Fig. 1B). The root mean square deviation of the Cα atoms was measured to evaluate the structural changes of the complex by running a 200 ns simulation37,38. The C-alpha atoms of the protein consistently exhibited RMSD values between approximately 4 and 4.8 Å during the simulation, while the RMSD of the ligand closely aligned with that of the protein atoms, suggesting that the complex remained stable (Fig. 2A). RMSF values were calculated to investigate the protein residues dynamics upon interacting with the ligands39. The RMSF plots revealed that most of the residues did not show many fluctuations during simulation as the RMSF values were lower than 2 Å, throughout the simulation indicating that the ligand did not exert the fluctuations in the protein. In contrast, the residues in the loop regions showed high fluctuations, reaching around 6 Å, suggesting increased flexibility in these regions (Fig. 2B). The interactions of key residues during the simulation were observed being hydrogen bonding, water bridges, ionic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions. The interactions with key residues that were consistent from docking to simulations were GLU127, LEU18, ASN100 shown in Fig. 2D and other interactions are given in Fig. 2C. While Glu127 showed maximum interactions in all residues which were observed in 59% of the snapshots likely interfering with the methyl transfer reaction by preventing proper substrate stabilization. (Fig. 2D). Additionally, the binding free energy of the complex was assessed using the prime-MMGBSA module. This binding free energy comprised the sum of Van der Waals, Coulomb, solvation, and covalent energies. Specifically, the contributions were as follows: Van der Waals energy was − 39.29 kcal/mol, solvation energy was 38.22 kcal/mol, covalent energy was 4.42 kcal/mol, and Coulombic energy was − 46.87 kcal/mol. Consequently, the total binding free energy of the complex amounted to -71.16 kcal/mol as shown in Fig. 3. The principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to calculate the variance percentage in protein clusters. The dominant movement was observed in the first five eigenvectors that showed eigenvalues 26.9, 18.2, 13.2, 8.3, and 5.3 respectively. The total variation was 77.9%. The highest variation was observed in PC1 which recorded 26.87% fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 4A). Similarly, PCA based 2D energy surface was generated to calculate the configuration with stable thermodynamic values. The energy surface calculated the fluctuation direction of energy in two PCs (PC1 and PC2) for carbon alpha atoms. Most of the cluster were found in the local minima well (purple color) which indicated the stable transition of one configuration to another (Fig. 4B). Such stability in binding conformations is critical for the consistent inhibitory activity of a drug. Together, these energetic and dynamic profiles provide a mechanistic foundation for further optimization of these natural compounds, suggesting that targeted modifications could enhance both their binding affinity and pharmacokinetic properties, ultimately accelerating the development of effective inhibitors against macrolide resistance.

Fig. 1.

(A) The interactions of ligand with rRNA methyltransferase protein. Hydrogen bonds (green), Hydrophobic (magenta). (B) The representation of ligand binding to the domain of protein.

Fig. 2.

(A) The RMSD plot of the rRNA methyltransferase complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 3.

The binding free energy values exhibited by the energy components.

Fig. 4.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B)2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

Tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump

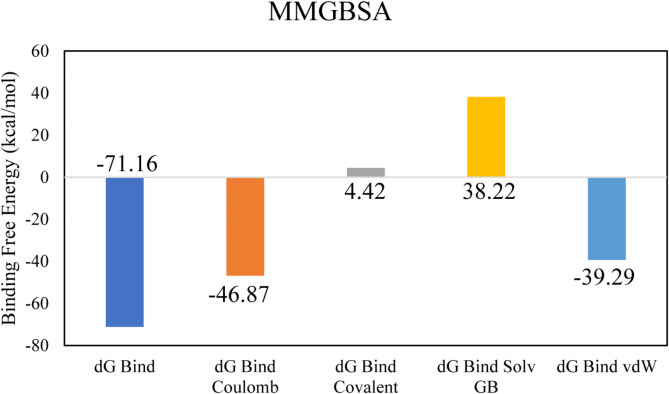

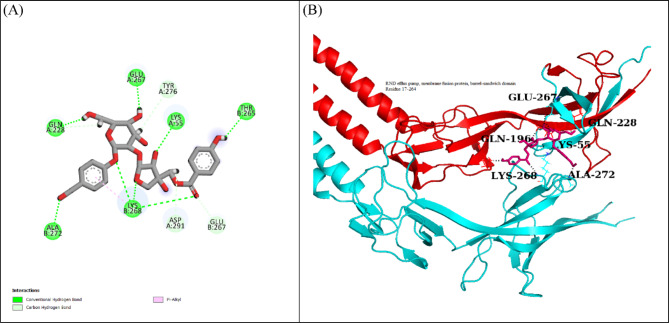

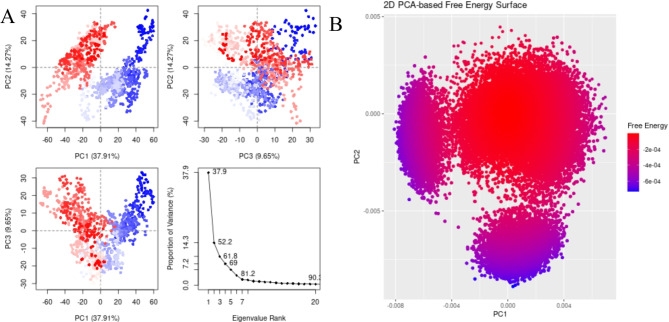

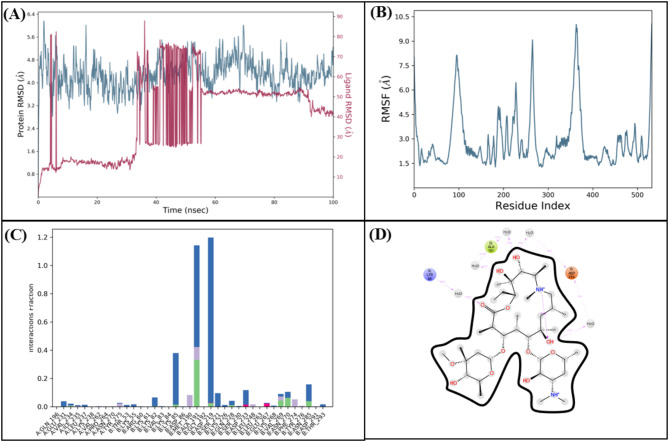

The docking analysis of the Tripartite Macrolide-specific Efflux Pump protein indicated that LTS0263188 exhibited the highest binding affinity among the ligands evaluated, leading to its selection for further molecular interaction and stability analysis. The molecular interactions showed that LTS0263188 made hydrogen bonds with six residues Lys55, Glu267, Gln228, Ala272, Lys268, and Thr265. It also made one hydrophobic interaction with Lys268 as shown in Fig. 5A. The compound was bound with the residues of RND efflux pump, barrel sandwich domain (Fig. 5B). The RMSD of the C-alpha atoms of the protein remained within the range of approximately 3.2 to 4 Å after reaching equilibrium at 50 ns, while the RMSD of the ligand closely aligned with that of the protein atoms, indicating the stability of the complex with minimum fluctuations (Fig. 6A). The RMSF analysis demonstrated that most residues remained stable and compact throughout the simulation, apart from two loop regions, which exhibited fluctuations of approximately 5 Å and 9 Å, respectively (Fig. 6B). In the protein-ligand contact analysis, the residues participating in hydrogen bonding were identified as Gln228, Asp291, Glu231, Asp271, and Ile273. Notably, Glu231 also played a role in ionic interactions (Fig. 6C). Among these interacting residues, Glu231 demonstrated the strongest binding affinity, with interactions occurring in 76% of the total frames, on the other hand ASP291’s interaction was consistent from docking to simulation (Fig. 6D). The strong and frequent interactions observed between LTS0263188 and these residues suggest that the compound obstructs the conformational changes required for efficient efflux, thus helping to restore macrolide activity. The calculation of binding free energy revealed that the total binding free energy of the complex was − 51.37 kcal/mol, while additional energy components are illustrated in Fig. 7. The PCA analysis showed the dominant movement in the first five eigenvectors as follows 37.9, 14.3, 9.6, 7.2, and 12.2 respectively. The total variation was 81.2%. The highest variation was observed in PC1 which recorded 37.91% fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 8A). The PCA results, showing that most conformational variance is captured in a few principal components with a deep local energy minimum, confirm that LTS0263188 maintains a stable binding conformation throughout the simulation. This consistent binding stability is critical for drug design, as it suggests that the compound is likely to retain its inhibitory pose under physiological conditions, thereby enhancing its potential as a robust therapeutic agent (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 5.

(A) The interactions of ligand with Tripartite Macrolide-specific Efflux Pump protein. Hydrogen bonds (green), Hydrophobic (magenta). (B) The representation of ligand binding to the domain of protein.

Fig. 6.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Tripartite Macrolide-specific Efflux Pump complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 7.

The binding free energy values exhibited by the energy components.

Fig. 8.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

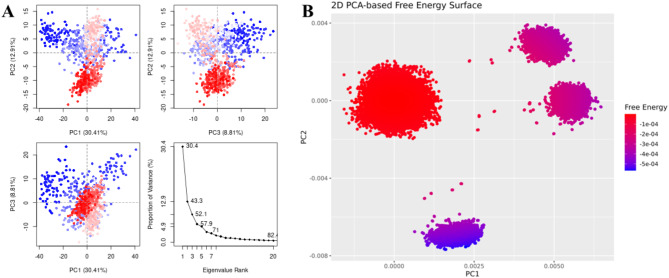

Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I

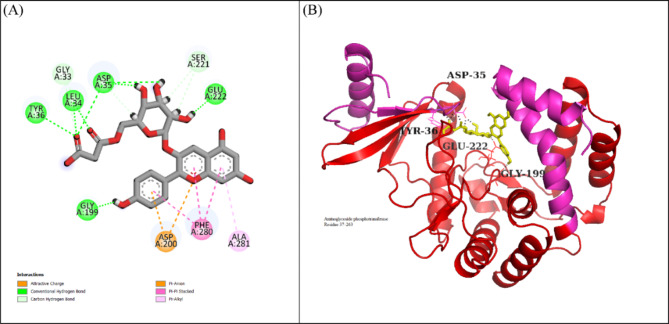

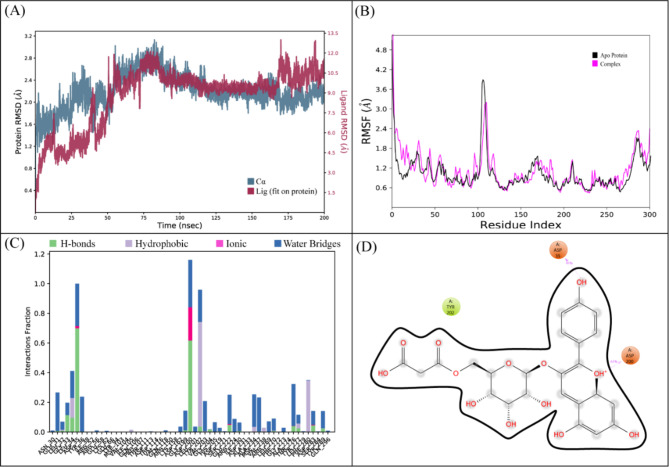

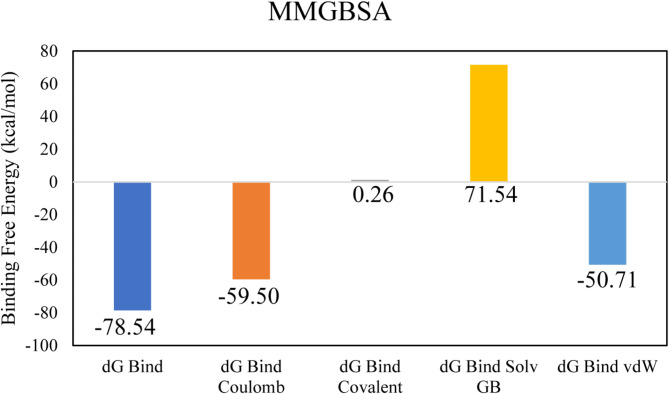

LTS0024216 showed the highest binding affinity against Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I protein. The molecular interactions showed that LTS0024216 made five hydrogen bonds with Tyr36, Leu34, Asp35, Gly199, and Glu222, and two hydrophobic interactions with Phe280 and Ala281, and one pi-cation interaction with Asp200 as shown in Fig. 9A. The compound was bound with the residues of Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain (Fig. 9B). The RMSD of C-alpha atoms of protein gradually increased to ~ 2.8 Å at 75 ns and then gradually decreased to 2.4 Å at 100 ns and then maintained this range till the end of simulation. The RMSD of ligand was aligned with the RMSD of protein atoms indicating the stability of the complex (Fig. 10A). The RMSF analysis showed that that the residues remained compact during the simulation except for a loop region whose value reached ~ 3 Å (Fig. 10B). In protein-ligand contact analysis, the residues involved in hydrogen bonding were Gly33, Leu34, Asp35, Asp200, Thr276, and Tyr289. Asp35 and Asp200 were also involved in ionic interactions during the simulation (Fig. 10C). Among the interacting residues, Asp200 displayed the strongest binding affinity, with interactions noted in 61% of the total frames, on the other hand ASP200 and ASP35 were key residues which showed consistency from docking to simulation (Fig. 10D). LTS0024216’s consistent binding to Asp200 indicates that it likely competes with the natural substrate, thereby blocking the phosphorylation process that inactivates macrolide antibiotics. The binding free energy calculation indicated that the total binding free energy of the complex was − 78.54 kcal/mol, and additional energy components are presented in Fig. 11. The PCA analysis showed the dominant movement in the first five eigenvectors as follows 45, 13, 5.5, 4.4, and 10.8 respectively. The total variation was 78.6%. The highest variation was observed in PC1 which recorded 44.98% fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 12A). The PCA results, with most of the conformational variance confined to a few principal components and deep local energy minima observed in the 2D energy surface, indicate that LTS0024216 adopts a highly stable binding conformation. This stability is a critical attribute in drug design, as it suggests that the compound can reliably maintain its inhibitory pose within the active site under dynamic physiological conditions (Fig. 12B).

Fig. 9.

(A) The interactions of LTS0024216 with Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I protein. Hydrogen bonds (green), hydrophobic interactions (magenta). (B) The representation of ligand binding to the domain of protein.

Fig. 10.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 11.

The binding free energy values exhibited by the energy components.

Fig. 12.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

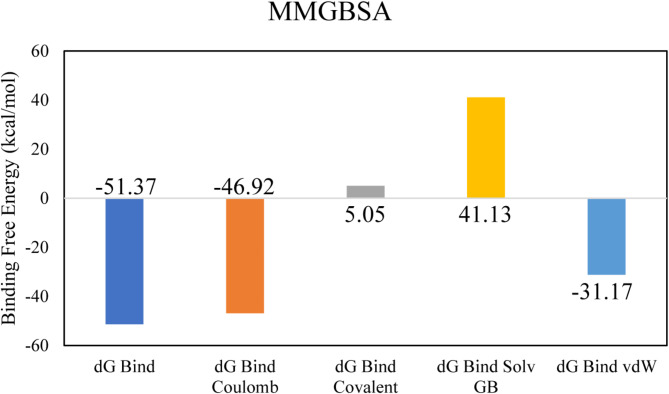

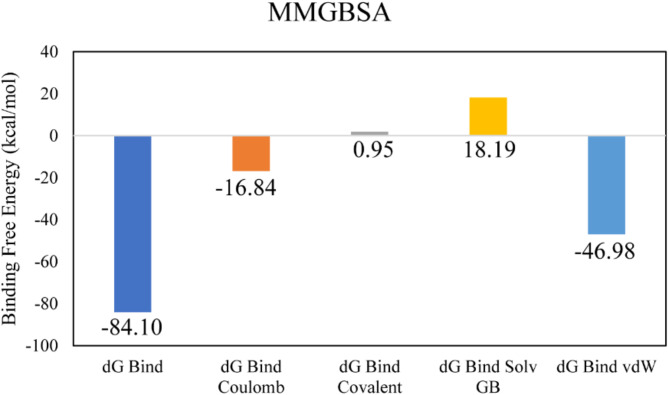

Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II

In the docking studies of Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II protein, LTS0110759 showed the highest binding affinity among the selected ligands. The molecular interactions showed that LTS0110759 made eight hydrogen bonds with Glu222, Gly199, Val201, Phe234, His202, His230, Ser276, and Leu269. It was involved in hydrophobic interactions with Ser276 and Ile277 as shown in Fig. 13A. The compound was bound with the residues of Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain (Fig. 13B). The RMSD of C-alpha atoms of protein maintained a range of ~ 2.5 Å till 50 ns and then gradually increased to 3.5 Å and then maintained this range till the end of simulation. The RMSD of ligand was aligned with the RMSD of protein atoms, which indicates that the complex attained stability (Fig. 14A). The RMSF analysis showed that that the residues remained compact during the simulation except for loop regions of the protein whose value reached ~ 5.6 Å (Fig. 14B). In protein-ligand contact analysis, the residues involved in hydrogen bonding were Arg162, Gly199, Asp200, Glu222, Lys224, His230, Tye273, and Ser276. Glu222 and Lys224 also made ionic interactions (Fig. 14C). Among the interacting residues, His230 demonstrated the greatest binding affinity, with interactions occurring in 95% of the total frames suggesting that it competes with the natural substrate for binding at the active site and disrupts the phosphorylation mechanism, on the other hand consistent key residues interaction from docking to simulation were GLU222, HIS230, SER276 which are important as these interactions are all forming hydrogen bonding (Fig. 14D). The binding free energy calculation revealed that the total binding free energy of the complex was − 84.10 kcal/mol, and the other energy components are illustrated in Fig. 15. The PCA analysis showed the dominant movement in the first five eigenvectors as follows 24.6, 11.5, 9.6, 7.9, and 5.1 respectively. The total variation was 69%. The highest variation was observed in PC1 which recorded 24.55% fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 16A). The PCA analysis indicates that the complex predominantly adopts a stable binding conformation, with PC1 capturing 24.55% of the total motion and the 2D energy surface revealing well-defined local minima. This stability is crucial for drug design, as it suggests that LTS0110759 is likely to maintain a consistent inhibitory pose within the active site under physiological conditions (Fig. 16B).

Fig. 13.

(A) The molecular interactions of LTS0110759 against Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II protein. (B) The representation of ligand binding to the domain of protein.

Fig. 14.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 15.

The binding free energy values exhibited by the energy components.

Fig. 16.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

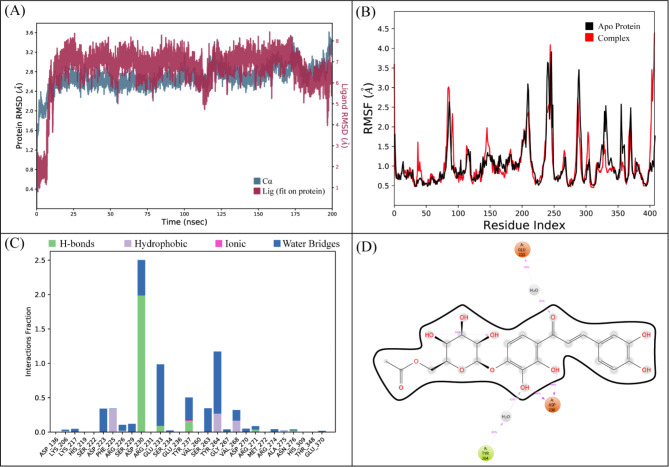

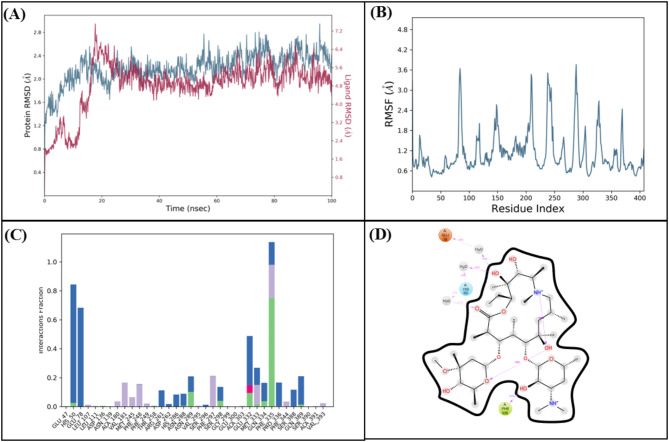

Erythromycin esterase erec

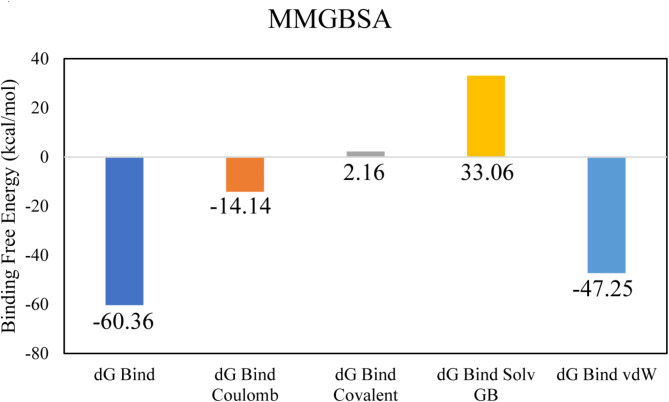

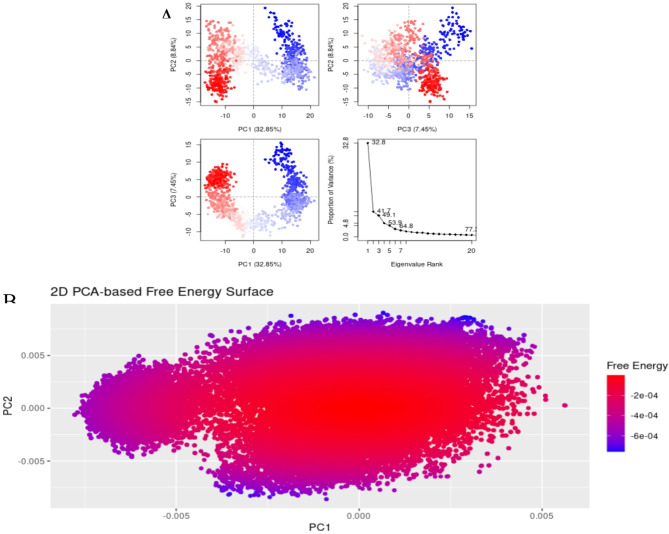

The molecular interactions of LTS0100971 were analyzed against Erythromycin esterase EreC, and it was observed that it made four hydrogen bonds with Lys206, Asp230, Asn276, and Arg271. It also made two hydrophobic interactions and one pi-cation interaction as shown in Fig. 17A. The compound was bound with the residues of binding pocket (Fig. 17B). The RMSD of C-alpha atoms of protein maintained a range of 2.8–3.2 Å throughout the simulation and the ligand was fitted on the protein RMSD values indicating the stability of the complex (Fig. 18A). The RMSF analysis showed that the residues remained compact during the simulation except for the loop regions (Fig. 18B). In protein-ligand contact analysis, the residues involved in hydrogen bonding were Asp230, Glu233, and Tyr237. The residues Glu233, and Tyr237 were also involved in ionic interactions (Fig. 18C). Among the interacting residues, Asp230 displayed the strongest binding affinity, with interactions recorded in 99% of the total frames, on the other hand GLU233 and ASP230 were consistent through docking to simulations involved in hydrogen bonding (Fig. 18D). The strong, persistent interaction of LTS0100971 with Asp230 likely prevents the hydrolytic cleavage of the antibiotic’s lactone ring, thereby inhibiting the enzyme’s function. The binding free energy calculation indicated that the total binding free energy of the complex was − 60.36 kcal/mol, while additional energy components are presented in Fig. 19. The PCA analysis showed the dominant movement in the first five eigenvectors as follows 32.8, 9.9, 7.4, 4.8, and 10.9 respectively. The total variation was 64.8%. The highest variation was observed in PC1 which recorded 32.85% fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 20A). These PCA results, with PC1 capturing 32.85% of the total motion and the 2D energy surface revealing well-defined local minima, indicate that LTS0100971 forms a highly stable complex with EreC. Such conformational stability is a key parameter in drug design, as it suggests that the compound will consistently maintain its inhibitory binding mode under physiological conditions (Fig. 20B).

Fig. 17.

(A) The molecular interactions of LTS0100971 against Erythromycin esterase EreC protein. (B) The representation of ligand binding to the protein pocket.

Fig. 18.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Erythromycin esterase EreC complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 19.

The binding free energy values exhibited by the energy components.

Fig. 20.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

According to the MMGBSA analysis and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the compounds demonstrated stability as effective inhibitors within the protein binding pocket. Consequently, the novel drug targets identified in this study could significantly impact the therapeutic sector by aiding in the discovery of inhibitors and the development of new drug formulations aimed at combating macrolide resistance. However, further experimental research is necessary to validate these drug targets.

Molecular dynamic simulations for control Azithromycin

The molecular interactions of Azithromycin control were analyzed against rRNA methyltransferase, and it was observed that it made only 1 hydrogen bond with Lys3. It also made 1 hydrophobic interaction with Ile5 unlike the top compounds reported against rRNA methyltransferase in this study (Fig. 21C). The compound was bound with the residues of binding pocket (Fig. 21B). The RMSD of C-alpha atoms of protein fluctuated up to 15ns but after that roughly maintained a range of 2.1–3.3 Å throughout the simulation and the ligand was fitted on the protein RMSD values indicating the stability of the complex (Fig. 21A). The RMSF analysis showed that the residues showed fluctuations during the simulation except for the loop regions (Fig. 21B). Among the interacting residues, only Lys3 (Fig. 21D) displayed the strongest binding affinity, with interactions recorded in 99% of the total frames, on the other hand Ile5 was consistent through docking to simulations involved in hydrophobic interaction (Fig. 18D). The PCA analysis of the control azithromycin-rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) complex reveals significant fluctuations, particularly in PC1, which accounts for the highest variance (36.11%) (Fig. 21A). The 2D PCA-based free energy surface indicates multiple distinct local minima, suggesting heterogeneous conformational transitions rather than a well-defined stable binding mode. The presence of high-energy states (red regions) further implies a less stable interaction between azithromycin and ErmAM. These findings suggest that the control complex lacks a strong and stable binding conformation, reinforcing the need for alternative ligands with improved binding stability and energetics (Fig. 22A-B).

Fig. 21.

(A) The RMSD plot of the rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 22.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

The molecular interactions of Azithromycin control were analyzed against tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, and it was observed that it made only 1 hydrogen bond with Lys55 (Fig. 23D). It also made 1 hydrophobic interaction with Ala191 unlike the top compounds reported against rRNA methyltransferase in this study (Fig. 23C). The compound was bound with the residues of binding pocket (Fig. 23B). The RMSD of C-alpha atoms of protein shows relatively larger fluctuations up to 55ns but after that roughly maintained a range of 4 Å throughout the simulation and the ligand was fitted on the protein RMSD values indicating the stability of the complex (Fig. 23A). The RMSF analysis showed that the residues showed very large fluctuations during the simulation except for the loop regions (Fig. 23B). Among the interacting residues, only ASP219 displayed the strongest binding affinity, with interactions recorded in 99% of the total frames (Fig. 18D). The PCA analysis of the azithromycin-tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump complex shows a markedly different dynamic profile compared to the control. PC1 dominates the variance (77.1%) (Fig. 24A), suggesting a highly constrained motion along a single principal direction. The 2D PCA-based free energy surface (Fig. 24B) reveals a more compact distribution of low-energy states, indicating a relatively stable binding mode. However, the presence of multiple distinct free energy basins suggests that azithromycin undergoes significant conformational transitions, potentially related to its interaction with the efflux pump’s functional states.

Fig. 23.

(A) The RMSD plot of the tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 24.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

The RMSD trajectory (Fig. 25A) shows extensive fluctuations throughout the simulation, indicating that the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I complex fails to settle into a stable conformation. Likewise, the RMSF plot (Fig. 25B) highlights elevated residue mobility in regions critical for binding, suggesting the ligand does not effectively stabilize the active site. The interaction frequency analysis (Fig. 25C) is diffuse, reflecting inconsistent or transient contacts rather than persistent, high-affinity binding. Finally, the 2D schematic (Fig. 25D) reinforces the impression that azithromycin’s interactions are sporadic at best, underscoring the inferior performance of this control complex relative to the more stable and robust binding profiles observed for our top‐ranked inhibitors. The PCA results for the azithromycin control complex show considerable scatter in the conformational space, with PC1 capturing a high percentage (44.19%) of the variance yet failing to converge into a well-defined cluster. This dispersion, combined with multiple energy basins on the 2D free energy surface, indicates that the control system undergoes extensive, unrestrained fluctuations rather than settling into a stable binding conformation. Such a fragmented distribution suggests that azithromycin does not reliably engage the active site under these simulation conditions, pointing to lower efficacy compared to the more focused, stable binding modes observed for our top‐ranked inhibitors (Fig. 26A and B).

Fig. 25.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 26.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

The RMSD trajectory (Fig. 27A) shows fluctuations from start to 20ns and then tries to be stable but somewhere major and minor fluctuations can still be observed indicating that azithromycin isn’t being finding it’s stable conformation throughout the simulation, indicating that the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I complex fails to settle into a stable conformation. RMSF plot (Fig. 27B) highlights elevated residue mobility in regions critical for binding, suggesting the ligand does not effectively stabilize the active site. About the ligand-protein interactions, it was observed that azithromycin form very less interaction with the protein Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II and in a sporadic manner, percentage of interactions is very low with the receptor unlike the reported top inhibitors in the study (Fig. 27C), only Ile103 shows the highest percentage fraction of interaction with the receptor. Moreover, Phe33 and Ala 33 are forming hydrophobic bonds in the complex as shown in Fig. 27D, no hydrogen bond is being formed in the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II complex. The PCA results for the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II complex reveal a broad spread of conformations, with PC1 (40.74%) (Fig. 28A) failing to converge into a singular, stable cluster. On the 2D free energy surface (Figure B), multiple scattered basins indicate that the system transitions among several ephemeral states rather than forming a single, well-defined binding pose. This suggests that azithromycin does not robustly occupy the active site, contrasting sharply with the more stable binding landscapes observed for our top-ranked inhibitors (Fig. 28B).

Fig. 27.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 28.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B)2DPCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

The RMSD trajectory (Fig. 29A) shows fluctuations from start to 18ns and then tries to be stable but somewhere major and minor fluctuations can still be observed in between 2.0 and 2.4 Å indicating that azithromycin isn’t being finding it’s stable conformation throughout the simulation, indicating that the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type I complex fails to settle into a stable conformation. RMSF plot (Fig. 29B) highlights elevated residue mobility in regions critical for binding, suggesting the ligand does not effectively stabilize the active site. The interaction frequency analysis (Fig. 29C) is diffuse, reflecting inconsistent or transient contacts rather than persistent, high-affinity binding, only Phe335 shows the highest percentage fraction of interaction with the receptor forming a hydrophobic interaction. Moreover, His50 and Glu78 are forming hydrophobic bonds in the complex as shown in Fig. 29D, no hydrogen bond is being formed in the azithromycin–Macrolide 2’-phosphotransferase type II complex. The PCA data for the azithromycin–Erythromycin esterase (EreC) complex display a widely dispersed conformational landscape, with PC1 (32.19%) (Fig. 30A) not converging into a single dominant cluster. The 2D free energy surface (Figure B) exhibits several scattered minima, suggesting the complex transitions among multiple transient states rather than settling into a stable binding pose. Such diffuse clustering implies weaker or inconsistent engagement of azithromycin with EreC, especially when contrasted with the more cohesive, stable binding profiles observed for our lead inhibitors (Fig. 30B).

Fig. 29.

(A) The RMSD plot of the Erythromycin esterase EreC complex. (B) The residual fluctuation analysis. (C) The protein-ligand interactions. (D) Percentage of interactions observed in snapshots.

Fig. 30.

(A) The principal component analysis, indicating the fluctuations in different hyperspaces. (B) 2D-PCA based free energy surface of the complex calculated during simulation.

Our MD simulation results, characterized by stable protein and ligand RMSD values, low RMSF in key binding regions, and persistent hydrogen bond networks, are consistent with previously reported studies comparing ligand-bound and apo forms. For instance, prior work40,41 has shown that ligand binding significantly reduces conformational fluctuations and reinforces the stability of the active site. Although direct comparison with the apo form was not feasible for all targets due to structural data limitations, the observed stability in our molecule-bound complexes suggests that the binding of our candidate inhibitors likely induces similar stabilization effects, reinforcing their potential for effective inhibition. Future studies will aim to include a more direct comparative analysis with available apo or reference complexes to further substantiate these findings.

Conclusion

The rising prevalence of macrolide resistance necessitates novel approaches to combating this issue. In recent years, computational approaches combined with natural product exploration have shown promise for the discovery of novel antimicrobial agents. The current study aimed to conduct molecular docking and virtual screening of natural products targeting macrolide resistance proteins ErmAM, Tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, mphA, mphB, and EreC, to design therapeutic interventions. The docking experiments were also corroborated by molecular dynamics simulations and the MM-GBSA binding free energy. Our molecular docking and MD simulation results show that five natural compounds, LTS0271681, LTS0263188, LTS0024216, LTS0110759 and LTS0100971, have the potential to act as inhibitors against ErmAM, Tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump, mphA, mphB, and EreC, respectively. However, computer validations were provided here, and further in-vitro and in-vivo study is required to turn these potential inhibitors into clinical drugs.

Acknowledgements

Authors extend their appreciation to researchers supporting project Number (RSPD2025R885) at King Saud University Riyadh Saudi Arabia for supporting this research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.A; Methodology, B.A; Supervision, A.A; Writing – original draft, R.A and B.A; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bryskier, A., Bergogne-Berezin, E. & Macrolides Antimicrob. Agents: Antibacterials Antifungals, 475–526 (2005).

- 2.Blondeau, J. M., DeCarolis, E., Metzler, K. L. & Hansen, G. T. The macrolides. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 11, 189–215 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fyfe, C., Grossman, T. H., Kerstein, K. & Sutcliffe, J. Resistance to macrolide antibiotics in public health pathogens. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med.6, 10 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lonks, J. R. What is the clinical impact of macrolide resistance? Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep.6, 7–12 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenyon, C., Manoharan-Basil, S. S. & Van Dijck, C. Is there a resistance threshold for macrolide consumption? Positive evidence from an ecological analysis of resistance data from Streptococcus pneumoniae, Treponema pallidum, and Mycoplasma genitalium. Microb. Drug Resist.27, 1079–1086 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes, C. et al. Macrolide resistance mechanisms in enterobacteriaceae: focus on Azithromycin. Crit. Rev. Microbiol.43, 1–30 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund, D. et al. Large-scale characterization of the macrolide resistome reveals high diversity and several new pathogen-associated genes. Microb. Genomics8, 000770 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Čižman, M., Pokorn, M., Seme, K., Oražem, A. & Paragi, M. The relationship between trends in macrolide use and resistance to macrolides of common respiratory pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.47, 475–477 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golkar, T., Zieliński, M. & Berghuis, A. M. Look and outlook on enzyme-mediated macrolide resistance. Frontiers in microbiology 9, (2018). (1942). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Pavlova, A., Parks, J. M., Oyelere, A. K. & Gumbart, J. C. Vol. 90 641–652 (2017). (Wiley Online Library.

- 11.Taniguchi, K. et al. Identification of functional amino acids in the macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase II. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.43, 2063–2065 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yum, S. et al. Crystal structure of the periplasmic component of a tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump. J. Mol. Biol.387, 1286–1297 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuberger, A., Du, D. & Luisi, B. F. Structure and mechanism of bacterial tripartite efflux pumps. Res. Microbiol.169, 401–413 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick, A. W. et al. Structure of the MacAB–TolC ABC-type tripartite multidrug efflux pump. Nat. Microbiol.2, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zieliński, M., Park, J., Sleno, B. & Berghuis, A. M. Structural and functional insights into esterase-mediated macrolide resistance. Nat. Commun.12, 1732 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stsiapanava, A. & Selmer, M. Crystal structure of ErmE-23S rRNA methyltransferase in macrolide resistance. Sci. Rep.9, 14607 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossiter, S. E., Fletcher, M. H. & Wuest, W. M. Natural products as platforms to overcome antibiotic resistance. Chem. Rev.117, 12415–12474 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinos, G. P. The macrolide antibiotic renaissance. Br. J. Pharmacol.174, 2967–2983 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan, J., Fu, A. & Zhang, L. Progress in molecular Docking. Quant. Biology. 7, 83–89 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanzione, F., Giangreco, I. & Cole, J. C. Use of molecular Docking computational tools in drug discovery. Prog. Med. Chem.60, 273–343 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sethi, A., Joshi, K., Sasikala, K. & Alvala, M. Molecular Docking in modern drug discovery: principles and recent applications. Drug Discovery development-new Adv.2, 1–21 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollingsworth, S. A. & Dror, R. O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron99, 1129–1143 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LigPrep & (Schrödinger LLC, (2018).

- 24.Shivakumar, D. et al. Improving the prediction of absolute solvation free energies using the next generation OPLS force field. J. Chem.The. Comp.8, 2553–2558 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Fong, D. H., Burk, D. L., Blanchet, J., Yan, A. Y. & Berghuis, A. M. J. S. Structural basis for kinase-mediated macrolide antibiotic resistance. 25, 750–761. e755 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Yum, S. et al. Crystal structure of the periplasmic component of a tripartite macrolide-specific efflux pump. J. Mol. Bio387, 1286–1297 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zieliński, M., Park, J., Sleno, B. & Berghuis, A. M. J. N. C. Structural and functional insights into esterase-mediated macrolide resistance. Nat. Com.12, 1732 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Yu, L. et al. Solution structure of an rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) that confers macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin antibiotic resistance. Nat. Str. Bio.4, 483–489 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Schrödinger, L. J. S. S. & Schrödinger LLC; New York, NY: 2, 2017 – 2011 (2017). (2017).

- 30.Kim, M. O., Nichols, S. E., Wang, Y. & McCammon, J. A. J. J. o. c.-a. m. d. Effects of histidine protonation and rotameric states on virtual screening of M. tuberculosis RmlC. 27, 235–246 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ibitoye, O., Ibrahim, M. A., Soliman, M. E., J. J. o., R. & Transduction, S. Exploring the composition of protein-ligand binding sites for cancerous inhibitor of PP2A (CIP2A) by inhibitor guided binding analysis: paving a new way for the discovery of drug candidates against triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). J. Rec. & Trans.43, 133–143 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Friesner, R. A. et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate Docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of Docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem.47, 1739–1749 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Mali, S. N., Chaudhari, H. K. & J. O., P. S. J. Computational studies on imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine-3-carboxamide analogues as antimycobacterial agents: Common pharmacophore generation, atom-based 3D-QSAR, molecular dynamics simulation, QikProp, molecular docking and prime MMGBSA approaches. 5 (2018).

- 34.Bowers, K. J. et al. in Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing. 84-es.

- 35.Price, D. J. & Brooks, C. L III. A modified TIP3P water P.tential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phy.121, 10096–10103 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Jednačak, T., Mikulandra, I. & Novak, P. Advanced methods for studying structure and interactions of macrolide antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 7799 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sargsyan, K., Grauffel, C. & Lim, C. How molecular size impacts RMSD applications in molecular dynamics simulations. 13, 1518–1524 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Dhankhar, P. et al. Computational guided identification of novel potent inhibitors of N-terminal domain of nucleocapsid protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J. BioMol. Str. & Dyn.40, 4084–4099 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Martínez, L. J. P. O. Automatic identification O. mobile and rigid substructures in molecular dynamics simulations and fractional structural fluctuation analysis. Plos One10, e0119264 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Rutz, A. et al. The LOTUS initiative for open knowledge management in natural products research. eLife11, e70780 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalal, V. et al. Structure-Based identification of potential drugs against FmtA of Staphylococcus aureus: virtual screening, molecular dynamics, MM‐GBSA, and QM/MM. Protein J.40, 148–165 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumari, R. et al. Structural-based virtual screening and identification of novel potent antimicrobial compounds against YsxC of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Mol. Struct.1255, 132476 (2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.