Abstract

Background

Studies have found a higher risk of comorbid anxiety and depression among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) compared with healthy individuals. If left untreated, comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with IBD can lead to poorer health outcomes and an increased healthcare utilization. The goal of this work was to develop a consensus statement to begin to address patient and provider needs and responsibilities related to screening and treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms among patients with IBD.

Methods

A literature scan was conducted to gather evidence-based background information and recommendations on the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with IBD. This was followed by the engagement of a panel of IBD and mental health experts and patient advocates using a modified Delphi process to synthesize the literature and distill the information into a core set of statements to support provider actions and care delivery.

Results

Six statements were distilled from the literature and consensus process that link to the general management, screening, and treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with IBD.

Conclusions

Mental healthcare and support for IBD patients is critical; the statements included in this article represent practical considerations for IBD healthcare professionals in addressing key issues on provider awareness, knowledge and behaviors, screening and treatment resources, and patient education.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, IBD, anxiety, depression, screening, treatment

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Key Messages.

What is already known?

People with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are more likely to experience symptoms of anxiety and depression than similar healthy individuals and need support to manage those symptoms as a part of routine IBD care.

What is new here?

This article draws from the literature, provider, and patient experiences to communicate 6 practical consensus statements to support IBD professionals and patients around screening and treatment of anxiety and depression symptoms.

How can this study help patient care?

This study seeks to raise IBD healthcare provider awareness of and resources for practical strategies they can adopt to improve patient care delivery around anxiety and depression.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, are chronic immune-mediated diseases that cause inflammation throughout the gastrointestinal tract.1 Nearly 1 in 100 Americans are diagnosed IBD.2

Although IBD is a gastrointestinal disease, it can have a profound impact on a patient’s emotional health. Studies have found a higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, among patients with IBD. Compared with similar healthy individuals, patients with IBD were found to have 3 to 5 times higher risk of developing anxiety disorders and 2 to 4 times higher risk of developing depression disorders in their lifetime.3,4 These psychiatric comorbidities can have significant implications for IBD patients, with evidence supporting an association between psychiatric state and IBD disease course, such as patients with more depressive symptoms presenting with greater inflammation due to stressors.5 Depressive symptoms are also associated with IBD relapse and shorter periods of remission.6 Evidence suggests that this may be due to the impact of psychological stress on neuroenteric pathways.7

Research also indicates a bidirectional relationship between IBD disease status and psychiatric comorbidities.8-10 Patients with depressive symptoms are at an increased risk of having and developing gastrointestinal disorders. Furthermore, there is evidence of an association between depressive state and subsequent deterioration in disease course of Crohn’s disease.1 This bidirectional relationship is worth exploring through the lens of a healthcare provider, as there may be an intersection between screening and treatment practices for IBD patients and patients with anxiety and depression. It is suggested that patients with IBD should be monitored for psychological well-being.11

Exploring the screening and treatment practices currently available and commonly practiced is important due to the impact psychiatric comorbidities may have on IBD care. IBD is among the costliest chronic conditions, particularly among patients with both IBD and mental health diseases.12 If left untreated, comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with IBD can lead to poorer health outcomes and increased healthcare utilization.13 Addressing anxiety and depression were identified as 2 potential areas of focus to prevent hospital readmission in patients with IBD.14 The integration of psychological support into routine IBD care was found to be important to holistic patient care of this population. Additionally, patients offered this care were found to be receptive to it, and the health outcomes were found to be positive.15

The goal of this work was to develop a consensus statement to begin to address patient and provider needs related to screening and treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms among patients with IBD. This was accomplished via a literature scan to gather evidence-based background information and recommendations, followed by the engagement of a panel of IBD and mental health experts using a modified Delphi process16 to synthesize the literature and distill the information into a core set of statements to support provider actions and care delivery.

Methods

Literature Scan

We conducted a literature scan using multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, and APA PsycInfo, to identify articles published between 2012 and 2023. In addition, a hand search of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation’s Crohn’s & Colitis 360 online journal was conducted. Search terms included “Crohn’s,” “Colitis,” “inflammatory bowel disease,” “ulcerative colitis,” “depression,” “depressive disorder,” “anxiety,” “mental health,” “mental disorder,” “psychiatric illness,” “psychological wellbeing,” “systematic review,” “meta-analysis,” “randomized control trial,” “screening,” “diagnosis,” and “therapies.” These terms were used to generate an initial list of publications to be searched.

Studies were selected for inclusion if they discussed practical applications of screening, diagnosis, and treatment approaches for patients diagnosed with IBD alongside symptomatic or comorbid anxiety and/or depression. Only studies reported in the English language and conducted in countries designated as very highly developed per the United Nations Human Development Index were included.17,18 Research including psychiatric illnesses other than anxiety or depression were excluded, as they were considered separate entities from the priority area of focus.

Two reviewers (N.R.V. and E.C.) independently screened the complete list of publications between 2012 and August 2023. The resulting titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion into the review against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third reviewer was used to resolve any discrepancies by discussion. The original articles were retrieved for retained abstracts, and full-text reviews of the articles were conducted to further assess eligibility. Relevant data from the final list of included research articles were extracted into an article summary matrix, including study design, population size and characteristics, and key factors related to the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with IBD.

Elicitation Process

A panel of 9 experts in IBD-related care was engaged to review the literature scan and provide input as a part of the elicitation process. Panelist backgrounds included IBD healthcare clinicians, mental health professionals with expertise in working with patients with IBD, and IBD patient advocates. The goal of the panel was to synthesize relevant information from the literature as well as patient and provider experiences to develop a set of statements to help IBD healthcare professionals navigate patients’ needs related to anxiety and depression. Panelists were engaged in a modified Delphi process that included a review of background materials identified through the literature scan, followed by 2 virtual meetings and 3 asynchronous sessions of panel review and comment. The modified Delphi process was selected because it allowed for input from a wide variety of experts, much of the input could be collected anonymously to encourage honest dialogue and feedback, and while it was a more lengthy process, it included multiple opportunities to revisit decisions made at each step to ensure that there was broad agreement on the final statements. Engagement was conducted using a combination of the XLeap virtual engagement system and Zoom. XLeap allows for real-time and asynchronous engagement during the elicitation process in which panelists can see and respond to feedback from other members.

Materials were created to synthesize the key findings from the literature scan, including recommendations from study authors and a compilation of depression and anxiety screening and treatment approaches. These materials were shared with panel members in advance of the first virtual meeting. The 5-step modified Delphi process is described subsequently and in Figure 1. The first virtual meeting was used to gather input on key considerations in developing the consensus statements, including the role of IBD healthcare professionals in providing screening and treatment to patients around anxiety and depression, and key issues related to screening and treatment of anxiety and depression in individuals with IBD. Feedback was obtained from 8 of the 9 panel members at this meeting, and this feedback was used to develop an initial set of draft consensus statements that were shared with panelists for asynchronous review and scoring via XLeap. During the second round, all 9 panelists submitted qualitative feedback and reflected on draft language for the consensus statements. The third round consisted of panelist review and feedback via XLeap on the language for the updated consensus statements that incorporated the feedback provided during the prior round. All 9 panelists provided qualitative feedback on the language of the statements and conducted a rank-order exercise to prioritize statements within the 3 categories of general management, screening, and treatment. Panelists were also encouraged to provide qualitative feedback on their ratings. The mean score and normalized standard deviation for each statement were calculated using XLeap.19 The normalized standard deviation is an indication of consensus within the group in which below 0.2 indicates general to strong consensus in the group and above 0.3 indicates strong dissent. Two initial draft statements obtained a normalized standard deviation of 0.32, the only statements above the 0.3 threshold for consensus. In these cases, qualitative feedback was used to clarify the statements and, in both cases, these statements were combined with other statements as the primary concern was duplication of other statements. The study team utilized the qualitative feedback and the ratings to create a final set of statements for panel review. The fourth round brought participants together through a virtual meeting to reflect on the previous comments, review feedback, and finalize language for the consensus statements. The final round was conducted asynchronously, and all 9 participants provided feedback on the final statements and input on the final screening tools and treatment approaches to be highlighted.

Figure 1.

Modified Delphi process,

Results

Literature Scan

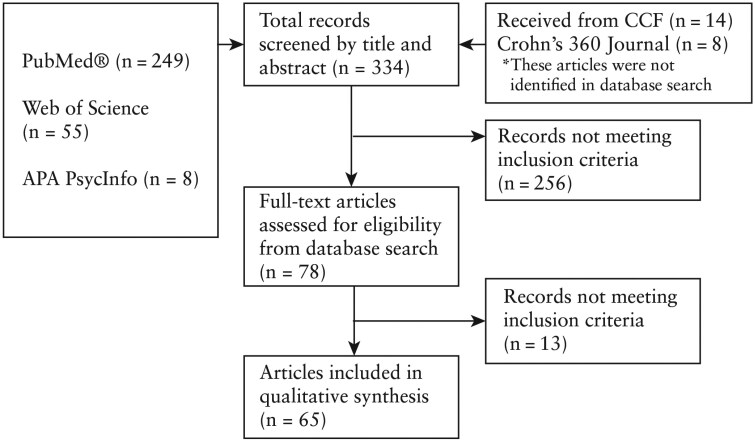

The electronic search identified 334 potentially eligible studies for screening after the addition of the manual searches (Figure 2). Seventy-eight articles were considered for full evaluation. Sixty-five articles met the inclusion criteria for data extraction. Forty-eight studies included factors relating to screening, 10 studies included factors relating to diagnosis, and 54 studies included factors relating to treatment.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for article search, screening, retrieval, and review. CCF, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation.

Multiple studies included more than 1 category among screening, diagnosis, and treatment factors. Four additional approaches as part of the provision of care were identified and included.

Consensus Statements

Using input from the literature scan and their own expertise and experience, the expert panel developed 6 consensus statements (Table 1) that serve to provide IBD healthcare professionals with evidence-based suggestions for working with patients who may need additional resources or treatment for depression, anxiety, or both. Although these statements provide a starting point for IBD healthcare professionals to work with their patients, they are not intended to be an exhaustive set of recommendations for every scenario. Additional discussion is needed within individual IBD care teams to identify best practices specific to their teams, resources, context, and patients.

Table 1.

Final consensus statements

| Statement |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Consensus Statement 1. Initiate and maintain conversations regarding mental and emotional well-being with patients to provide information and support regarding the bidirectional relationship between and co-occurrence of anxiety and depression and IBD disease course.

Panel members sought to emphasize the importance of IBD healthcare professionals normalizing patient-provider conversations surrounding mental health and emotional well-being, considering the bidirectional effects between anxiety and depression symptoms and the course of IBD. Anxiety and depression may increase the risk for development of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis by driving inflammation and exacerbating IBD disease symptoms, as well as by increasing the likelihood of recurrence; simultaneously, the onset of depression can affect one’s quality of life, self-management behaviors, and adherence to treatment.10,20,21 Thus, IBD healthcare professionals are strongly encouraged to raise these issues, using patient-friendly language to explain the connection between IBD disease activity and anxiety and depression to reduce mental health-related stigma, for instance, “It is normal to feel sad and anxious as you live with inflammatory bowel disease” to initiate a more detailed discussion. Subsequently, IBD healthcare professionals can encourage and facilitate patient referrals when psychological intervention or treatment is needed.21

Consensus Statement 2. Routinely screen all IBD patients for mental and emotional well-being, including symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Screening for anxiety and depression—through informal discussions and/or validated formal screening questionnaires—should be conducted as part of routine care for IBD patients, as psychological symptoms are often present throughout the disease course in IBD patients.22 Only an IBD care team clinician (eg, physician, advanced practice provider, dietitian, psychologist, social worker) should conduct screening. Initiating brief conversations at every appointment as a part of the review of symptoms may help normalize conversations surrounding mental health; asking a simple, open-ended question such as, “How have you been coping/managing lately?” may help start the discussion. It is suggested that formal screening tools should be administered at least annually or as clinically indicated—these can be administered by office staff or any member of the IBD care team, but results should be reviewed with the patient by their primary IBD healthcare professional. This is recommended in the event that screening suggests that a patient is experiencing extreme anxiety or depression or in cases in which suicidality is indicated.

To extend accessibility to diverse populations, healthcare professionals should consider administering screenings tools that are available for both English- and non–English-speaking patients. Table 2 provides a list of screening tools that were reported to be commonly used by IBD clinicians and mental health professionals. Regardless of screening method, healthcare professionals should always aim to provide culturally sensitive care and use inclusive language during screening to maintain a safe and supportive environment for patients.

Table 2.

Screening tools

| Screening tool name | Key characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age (y) | Cost per test | Who can administer the tool? | Delivery in person or online | Time to administer screener (min) | Other languages available (besides English) | |

| Both anxiety and depression | ||||||

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)23,24 | Adult and pediatric patients | Free (by paper in English) | Self-report | Both | ~3 | Spanish |

| Depression | ||||||

| Beck Depression Inventory25,26 | 13-80 | >$100 | Self-administered or administered verbally by a trained administrator | Both | 5 | Spanish |

| Child Depression Inventory27,28 | 7-17 | >$300 | Self-report | Both | 5-15 | Spanish |

| Moods and Feelings Questionnaire29–31 | 6-19 | Free | Formal training is not required to administer | In person | 10 | Over 10 languages |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2 and PHQ-9)32–34 | 12 and older | Free | Self-administered or clinician-administered | Both | 2-5 | Over 20 languages |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory35,36 | 17-80 | >$100 | Self-administered or administered verbally by a trained administrator | Both | 5-10 | Spanish |

| General Anxiety Disorder-7 32,37,38 | 12 and older | Free | Self-administered or clinician administered | Both | 2-5 | Over 10 languages |

Screening results should be evaluated in real time by a professional. Some tools may include sensitive questions, such as those assessing suicidality (eg, Beck Depression Inventory, Child Depression Inventory, PHQ-2, PHQ-9); these questions should only be administered by a trained professional and interpreted immediately, or omitted if a professional is unable to promptly review and provide support.

Abbreviation: PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Consensus Statement 3. Seek out educational opportunities and training on how to effectively respond to patients who disclose or screen positive for anxiety and depression symptoms, including suicidal ideation.

IBD professionals should explore learning opportunities to address the gap in physician awareness and training with regard to managing IBD patients with comorbid anxiety and depression.39 For example, staff training on mental health management for all members of the IBD care team helps ensure successful anxiety and depression screening implementation, so that each provider understands their role in the process, practices the necessary skills, and feels more confident in conducting screening and follow-up. If screening indicates anxiety or depression symptoms are present, IBD healthcare professionals should be prepared to provide resources to patients that offer guidance on how to find and access additional mental health support and care, possible treatment options, and resources that can be accessed in their community. These resources should be readily available to ensure that patients can receive prompt access to services and timely care.40,41 The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation website (https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/science-and-professionals/education-resources) is a starting point that provides healthcare professionals with a variety of educational modules, resources, and training.42 In the event of a positive patient screening result for suicide risk, healthcare professionals should be prepared to follow up immediately and provide appropriate care. Thus, providers are strongly encouraged to participate in suicide prevention trainings to ensure that they are equipped with the necessary skills to provide support.

Consensus Statement 4. Demonstrate competence in having an informed conversation with patients regarding various evidence-based treatment approaches for anxiety and depression and the effects of these treatment approaches when offering resources and referrals.

There are a wide variety of treatment approaches available to patients dealing with anxiety and depression. Although IBD healthcare professionals are not expected to manage the anxiety and depression of their patients, they are strongly encouraged to develop and demonstrate competence of these treatment approaches so that they are prepared to have an informed conversation with their patients when needed. Treatments range from self-care practices and strategies to reduce stress to psychosocial interventions with trained therapists and psychopharmacological interventions. Table 3 provides examples of these treatment approaches as a starting point for familiarization. Self-administered interventions, for example, are those that can be recommended or provided by any member of the IBD care team and may be effective if a patient is experiencing mild anxiety or depressive symptoms. They can also be combined with other treatments for more severe anxiety and depression. Psychosocial approaches are provided by trained mental health professionals and can often be delivered in person or through virtual/telehealth meetings. Both modalities can also be paired with psychopharmacological approaches. Because patient preferences for treatment are critical to treatment adherence, IBD healthcare professionals are encouraged to become familiar with various treatment approaches so that the provider and patient can work collaboratively to find the appropriate patient supports. IBD healthcare professionals should also be knowledgeable of the effects of certain treatment approaches when offering resources or referrals. For example, it is important to inform patients that corticosteroid use may contribute to psychological morbidity when offering this class of medications to reduce inflammation.50

Table 3.

Sample treatment approaches

| Sample treatment approaches | Brief description/reason for inclusion | Provision by IBD professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Self-administered interventions | ||

| Diaphragmatic breathing | IBD professionals are able to recommend and provide instruction on this intervention. | |

| Yoga |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend and provide resources on this intervention. |

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend and provide resources on this intervention. |

| Psychosocial interventions | ||

| CBT | IBD professionals are able to recommend this intervention but should refer to a mental health professional for its provision. | |

| Primary and secondary control enhancement therapy |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend this intervention but should refer to a mental health professional for its provision. |

| Behavioral activation therapy |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend this intervention but should refer to a mental health professional for its provision. |

| Pharmacological interventions | ||

| ADM |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend and provide this intervention but may also wish to engage a psychiatrist. |

| Anti-TNF-α therapy |

|

IBD professionals are able to recommend and provide this intervention. |

Abbreviations: ADM, antidepressant medication; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Consensus Statement 5. Identify, maintain, and share a list or database of resources (eg, mental health providers, websites, apps) that patients can access to manage and treat their anxiety and depression symptoms.

IBD healthcare professionals are strongly encouraged to develop and maintain a list of mental health resources that can be provided to patients with depression and anxiety symptoms or diagnosis. Every community or practice will not have access to the same resources. Thus, it may be important not only to identify local resources, but other resources that may be available through telehealth, websites, or apps. For example, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Depression and Anxiety webpage (www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/mental-health/depression-anxiety) provides patients with information, resources, and references51 on these important issues. When possible, IBD professionals should seek to develop or participate in a multidisciplinary team comprising providers focusing on the medical management of IBD activity and those focusing on the treatment of anxiety and depression symptoms (eg, psychologists, social workers). Involvement in a multidisciplinary team can facilitate the development and maintenance of a resource database and serve to establish a referral network in which patients can access additional mental health resources.

Consensus Statement 6. Encourage patients to pursue evidence-based treatment approaches for symptoms of their anxiety and depression.

The literature is clear that many patients with IBD have a higher risk of experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression3,4 and will need support to normalize and manage those symptoms. IBD healthcare professionals play a critical role in providing both support and resources for these patients. Because of the stigma that often exists around mental health,52 patients may need encouragement to pursue evidence-based treatments for their anxiety and depression. Establishing a process to link patients to appropriate referrals and resources is critical. Unfortunately, delays between screening and treatment may occur due to several factors, including limited availability of mental health resources in a community, long wait times to access a mental health provider, patient insurance coverage and approvals, or patient ability to travel to another provider. In these situations, it is important for IBD healthcare professionals to make patients aware of mental health resources available to them. While awaiting professional mental healthcare, patients can also be instructed on how to implement some of the self-administered interventions and how to access psychosocial care through apps and telehealth resources. IBD professionals are also encouraged to familiarize themselves with 1 or 2 antidepressant medications. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants are well established in the treatment of anxiety and depression, though limited studies have been conducted on IBD patients.53 In certain cases, the IBD healthcare professionals who are properly trained on these medications may want to prescribe and manage these medications for their patients.

Discussion

Mental healthcare and support for IBD patients is critical. The statements included in this article represent a small set of practical considerations for IBD healthcare professionals. The statements address key issues around provider awareness, knowledge and behaviors, screening and treatment resources, and patient education. These statements are not intended to be comprehensive guidance, but rather are intended to be a summary of important issues providers need to consider as they provide patient care. Although many of these statements are supported by strong evidence within the IBD literature, some are supported by broader healthcare delivery best practices, such as using screening tools in languages other than English for patient comfort as needed, using patient-friendly and inclusive language when discussing mental health and IBD co-occurrence, and considering patient preferences when discussing treatment options. We chose to retain these important considerations because, although they may not be explicitly discussed within the current IBD literature, a strong evidence base does exist within broader best practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation National Scientific Advisory Committee Consensus Task Force for developing a consensus statement process for the National Scientific Advisory Committee to follow, as well as for identifying anxiety and depression as a priority focus area.

Contributor Information

Laurie Hinnant, Health Practice Area, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Nicholas Rios Villacorta, Health Practice Area, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Eliza Chen, Health Practice Area, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Donna Bacchus, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX, USA.

Jennifer Dotson, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, The Research Institute, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA; Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA.

Ruby Greywoode, Division of Gastroenterology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, USA.

Laurie Keefer, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Stephen Lupe, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Leah Maggs, Patient Advocate, Seattle, WA, USA.

Garrett Meek, Patient Advocate, Boulder, CO, USA.

Eva Szigethy, Pediatric Psychiatry, Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH, USA; Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Kathryn Tomasino, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Orna G Ehrlich, National Headquarters, Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Sylvia Ehle, National Headquarters, Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Ethical Considerations

We wish to emphasize the importance of continuous professional development, education, and training for IBD professionals around patient mental health, especially on how to support patients who may disclose suicidal ideation as a result of a mental health screening process.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation under a contract to RTI International (0282201.354).

Conflict of Interest

L.K. has served as a consultant to Pfizer; has served as a scientific advisor to Trellus Health and Coprata Health; and is co-founder and equity owner of Trellus Health. S.L. has served as a scientific advisor for Ayble Health and Boomerang Health; and as a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. All additional authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Alexakis C, Kumar S, Saxena S, Pollok R.. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the impact of a depressive state on disease course in adult inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(3):225-235. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/apt.14171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis JD, Parlett LE, Jonsson Funk ML, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and racial and ethnic distribution of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1197-1205.e2. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Irving P, Barrett K, Nijher M, de Lusignan S.. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in people with inflammatory bowel disease and associated healthcare use: population-based cohort study. Evid Based Ment Health. 2021;24(3):102-109. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1136/ebmental-2020-300223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu S, Chen Y, Chen Y, Wang C.. Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12(Oct):714057. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Hwang BS, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK.. Depressive symptoms enhance stress-induced inflammatory responses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31(Jul):172-176. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel J-B, von Känel R; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):829-835.e1. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS.. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54(10):1481-1491. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1136/gut.2005.064261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fairbrass KM, Lovatt J, Barberio B, Yuan Y, Gracie DJ, Ford AC.. Bidirectional brain-gut axis effects influence mood and prognosis in IBD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71(9):1773-1780. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keefer L, Kane SV.. Considering the bidirectional pathways between depression and IBD: recommendations for comprehensive IBD care. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;13(3):164-169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nikolova VL, Pelton L, Moulton CD, et al. The prevalence and incidence of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease in depression and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2022;84(3):313-324. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gracie DJ, Guthrie EA, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC.. Bi-directionality of brain-gut interactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1635-1646.e3. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szigethy E, Murphy SM, Ehrlich OG, et al. Mental health costs of inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(1):40-48. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ibd/izaa030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill E, Nguyen NH, Qian AS, et al. Impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders on healthcare utilization in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationally representative cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(9):4373-4381. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10620-022-07505-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnes EL, Kochar B, Long MD, et al. Modifiable risk factors for hospital readmission among patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a nationwide database. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(6):875-881. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lores T, Goess C, Mikocka-Walus A, et al. Integrated psychological care is needed, welcomed and effective in ambulatory inflammatory bowel disease management: evaluation of a new initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(7):819-827. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linstone HA, Turoff M, eds. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Advanced Book Program; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Insights. UNDP Human Development Reports. Accessed December 15, 2023. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks [Google Scholar]

- 18. United Nations Development Programme. Data and statistics readers guide. UNDP Human Development Reports. Accessed December 15, 2023. https://hdr.undp.org/reports-and-publications/2020-human-development-report/data-readers-guide#:~:text=The%20cutoff-points%20are%20HDI%20of%20less%20than%200.550,0.800%20or%20greater%20for%20very%20high%20human%20development [Google Scholar]

- 19. XLeap Handbook for Hosts. Organizational XLeap Center. Accessed on August 30, 2023. https://www.xleap.net/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/Handbook_XLeap_Hosts.pdf#nameddest=invite&pagemode=bookmarks [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fairbrass KM, Lovatt J, Barberio B, Yuan Y, Gracie DJ, Ford AC.. Bidirectional brain-gut axis effects influence mood and prognosis in IBD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71(9):1773-1780. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keefer L. Screening for depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;17(12):588-591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC.. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(5):359-370. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. HealthMeasures. Intro to PROMIS. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kadri O, Jildeh TR, Meldau JE, et al. How long does it take for patients to complete PROMIS scores?: an assessment of PROMIS CAT questionnaires administered at an ambulatory sports medicine clinic. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(8):232596711879118. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1177/2325967118791180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J.. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-571. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK.. Beck Depression Inventory. Pearson Assessments; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995-998. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4089116/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kovacs M. CDI 2: Children’s Depression Inventory 2. Multi-Health Systems (MHS). Accessed January 24, 2024. https://storefront.mhs.com/collections/cdi-2 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Messer SC, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents: factor composition and structure across development. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5(4):251-262. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duke Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences. Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). Duke University School of Medicine. .Accessed January 24, 2024. https://psychiatry.duke.edu/research/research-programs-areas/assessment-intervention/developmental-epidemiology-instruments-0 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rhew IC, Simpson K, Tracy M, et al. Criterion validity of the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire and one- and two-item depression screens in young adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2010;4(1):8. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1753-2000-4-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfizer. Screener Overview. Patient Health Questionnaire Screeners. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marvin K, Korner-Bitensky N, eds. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Stroke Engine. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://strokengine.ca/en/assessments/patient-health-questionnaire-phq-9/ [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA.. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893-897. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beck AT, Steer RA.. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. Psychological Corporation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B.. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bear HA, Moon Z, Wasil A, Ahuvia I, Edbrooke-Childs J, Wolpert M.. Development and validation of the illness perceptions questionnaire for youth anxiety and depression (IPQ-Anxiety and IPQ-Depression). Couns Psychol Q. Published online July 11, 2023. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1080/09515070.2023.2232320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bannaga AS, Selinger CP.. Inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety: links, risks, and challenges faced. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:111-117. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.2147/CEG.S57982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dubinsky MC, Dotan I, Rubin DT, et al. Burden of comorbid anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(9):985-997. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1080/17474124.2021.1911644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mackner LM, Whitaker BN, Maddux MH, et al. Depression screening in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease clinics: recommendations and a toolkit for implementation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(1):42-47. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Clinician Education. Accessed December 14, 2023, https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/science-and-professionals/education-resources [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hopper SI, Murray SL, Ferrara LR, Singleton JK.. Effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing for reducing physiological and psychological stress in adults: a quantitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(9):1855-1876. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilke E, Reindl W, Thomann PA, Ebert MP, Wuestenberg T, Thomann AK.. Effects of yoga in inflammatory bowel diseases and on frequent IBD-associated extraintestinal symptoms like fatigue and depression. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;45:101465. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, Mikocka-Walus A, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC.. Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(3):189-199. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30206-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hunt MG, Loftus P, Accardo M, Keenan M, Cohen L, Osterman MT.. Self-help cognitive behavioral therapy improves health-related quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease patients: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2020;27(3):467-479. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10880-019-09621-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Richards DA, Ekers D, McMillan D, et al. Cost and outcome of behavioural activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10047):871-880. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anxiety & Depression Association of America. Clinical Practice Review for GAD. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://adaa.org/resources-professionals/practice-guidelines-gad [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moulton CD, Pavlidis P, Norton C, et al. Depressive symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammation? Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;197(3):308-318. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/cei.13276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brooks AJ, Rowse G, Ryder A, Peach EJ, Corfe BM, Lobo AJ.. Systematic Review: psychological morbidity in young people with inflammatory bowel disease – risk factors and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(1):3-15. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/apt.13645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Depression and Anxiety. Accessed November 29, 2023. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/mental-health/depression-anxiety [Google Scholar]

- 52. Office of the Surgeon General. Mental health: a report of the surgeon general: executive summary. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service. Accessed January 29, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-LPS56921 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mikocka-Walus A, Ford AC, Drossman DA.. Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(3):184-192. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41575-019-0259-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]