Abstract

Liver disease (LD) is complex pathological condition that has emerged as a major threat to human health and the quality of life. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of LD have not yet been fully elucidated. Recently, a large amount of evidence has shown that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) play important roles in diverse biological processes in the liver. The dysregulation of lncRNAs in the liver, for example, can affect tumor proliferation, migration, and invasion, contribute to hepatic metabolism disorder of lipid and glucose, and shape of hepatic tumoral microenvironment. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the functional roles of lncRNAs in LD pathogenesis may provide new perspectives for the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic tools. In the present review, we summarize the current findings on the relationship between lncRNAs and LD, including the modes of action of lncRNAs, the biological significance of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of LD, especially in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as well as in some non-neoplastic disorders, and the potential use of lncRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for LD.

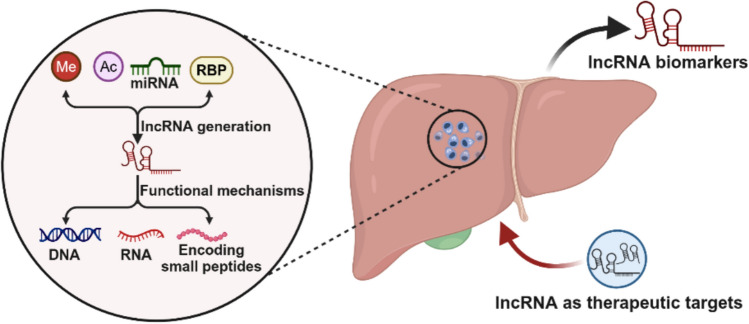

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Long noncoding RNA, Liver disease, Molecular mechanism, Diagnostic biomarker, Therapeutic target

Introduction

Liver disease (LD) causes over two million deaths annually and accounts for approximately 4% of all deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Importantly, the global burden of LD is projected to continue to increase in the future, because of the aging population and a rise in the incidence of metabolic risk factors [3, 4]. Over the past few decades, an extensive number of research has shed light on the epidemiological and toxicological/mechanistic characteristics of LD [5]. Importantly, these studies have indeed improved the prevention, monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment of LD to a certain extent [6, 7]. Unfortunately, owing to the lack of early detection and effective treatment, patients with LD always typically present advanced diseases, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), putting their life in a precarious situation [8, 9]. Hence, there is a more compelling need for high-fidelity early detection and risk prediction approaches for LD [10, 11].

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), a diverse class of RNA transcripts with lengths ranging from 200 bp to 100 kbp and lacking the significant open reading frames, are typically characterized by low expression levels, moderate sequence conservation, and high tissue specificity in humans [12, 13]. Although some people still believe that lncRNAs represent transcriptional “noise” caused by the leakage in the transcription machinery, lncRNAs play an important role in many life processes that cannot be ignored [14, 15]. In particular, lncRNAs have been used as a starting point to decipher the pathogenesis of diseases and establish new diagnostic and therapeutic targets in cancers, metabolic syndromes, and neurodegenerative diseases [16, 17]. One case in point is that lncRNA PCA3 has been successfully approved as an auxiliary biomarker for prostate cancer molecular diagnosis in the European Union, Canada, and the USA because of its important regulatory role in the tumor progression [18]. In the liver, the dysregulations of lncRNAs were reported to contribute to liver lipid metabolism disorder, induce macrophage and hepatic stellate cell activation, promote angiogenesis, and shape the hepatic tumor microenvironment [19, 20], which provides a new perspective for us to understand the pathogenesis of LD, and to find its medical targets or therapies for the prevention or treatment.

In this study, we highlight a few lncRNAs that are closely related to LD, by serially describing the causal effects of these dysregulated lncRNAs, introducing their modes of action, assessing their importance in liver pathology, and highlighting the potential use of these lncRNAs as targets for the diagnosis and treatment of LD.

Aberrant regulation patterns of lncRNA expression in LD

Large-scale sequencing investigations in recent years have shown distinct lncRNA expression profiles in LD, compared to the physiological state of the liver [21, 22]. In addition, the biogenesis process of lncRNAs is mostly under the control of cell type- and stage-specific stimuli. Therefore, understanding the biogenesis of lncRNAs in LD is beneficial not only for distinguishing them from other types of RNA, but also for deciphering their functional significance. LncRNAs are ubiquitously interspersed in the genome with various possible locations, such as enhancers, promoters, and intergenic regions. Although mechanisms of lncRNAs biogenesis have not been completely uncovered, the majority of lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from genomic loci with chromatin states similar to those of protein-coding transcripts (mRNAs). Therefore, events that regulate mRNA biogenesis may also affect the biogenesis of lncRNAs. In this section, we list the primary events that are closely related to the biogenesis of lncRNAs during LD (Fig. 1).

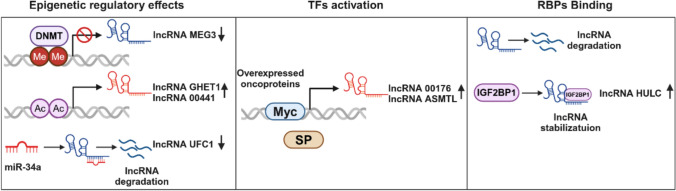

Fig. 1.

Aberrant regulation patterns of lncRNA expression in LD. Epigenetics, TFs, and RBPs binding are major events closely related to lncRNAs biogenesis during LD

Epigenetic regulatory effects

Epigenetics is the regulatory mechanism that alters gene expression without changing the original DNA. During LD progression, abnormal epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and ncRNAs, are universally identified at lncRNA genes [23]. Making it not surprising that altered epigenetic marks lead to lncRNA dysregulation. For instance, dysregulated enzyme activity is one of characteristic in the setting of LD. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) serve as susceptible enzymes in response to LD. It has been reported that the high levels of DNMTs in HCC could mediate hypermethylation of the promoter region of lncRNA MEG3, leading to the lncRNA downregulation [24]. Differently, some gene expressions are upregulated under the regulatory role of histone acetylation. Indeed, the role of histone acetylation in lncRNA expression has long been clarified. Bioinformatic analysis based on the GENCODE consortium has showed that active histone markers, such as H3K9ac and H3K27ac, were significantly enriched in the promoter regions of lncRNAs, thus promoting a series of lncRNA expression, including the upregulated lncRNA GHET1 [25] and linc00441 [26] in HCC.

Notably, abnormal DNA methylation and histone modifications are due to changes in related enzymes on the one hand; on the other side, they are caused by changes in liver substrates. It is worth mentioning that the liver is a key organ for maintaining systemic metabolic homeostasis. Many active small-molecule compounds derived from liver metabolism can be used as epigenetic substrates. For example, SAM is mainly synthesized in the liver and is a key single carbon donor in almost all biological methylation reactions. Additionally, Acetyl-CoA derived from glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism is an essential substrate for acetylation of histone residues. Currently, it does not directly connect metabolic changes to lncRNA biogenesis, but the role of metabolic drivers in gene expressions is undeniable.

Interestingly, there is a large degree of inter-regulation between ncRNAs in LD. NcRNAs are diverse and include, in addition to lncRNAs, microRNA (miRNA), PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA), and tRNA-derived small RNA (tsRNA) [27]. Among them, the relationship between lncRNAs and miRNAs has been extensively studied. Precisely, many lncRNAs act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) to bind to miRNAs, thereby interfering with their regulatory function in target proteins and RNA metabolism. We will discuss this interaction in more detail in the section of modes of lncRNAs action. Here, we focus on the response of miRNAs to lncRNAs. It has been shown that miRNAs can directly bind to lncRNA and then shorten its half-life, for example, the regulation of lncRNA-UFC1 by the miR-34a in HCC [28]. However, additional factors are sometimes required to assist miRNAs, such as miR-29 blocking DNMTs to rescue the expression of lncRNA MEG3 [29]. Regardless of the mode of action, however, these results reflect the importance of ncRNAs in the human body.

Transcription factors (TFs) activation

TFs can coordinate gene expression by recognizing and binding to specific nucleic acid sequences that regulate gene expression. Currently, methods for how TFs identify and bind to such sequences in vitro or in vivo have been extensively described [30]. Nonetheless, studies exploring TFs that are related to the expression of lncRNAs in human LD are still at a relatively nascent stage. Only partial oncogenic TFs/cofactors have been unequivocally reported. Myc is an enhanced oncogenic signaling molecule; and in HCC, the expressions of linc00176 [31] and ASMTL-AS1 [32] have been clearly demonstrated to be transcribed by Myc. In addition, SP is another universal TFs involved in regulating HULC expression [33]. Intriguingly, HULC has also been reported to be modulated by phosphorylated CREB [34], indicating that TFs can modulate lncRNA expression in a synergistic manner.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs)

RBPs are a robust family consisting of more than 2000 proteins that potently and ubiquitously regulate transcripts throughout their life cycle. Not surprisingly, RBPs are involved in the regulation of lncRNAs expression. Existing evidence shows that RBPs can alter the fate and function of lncRNAs by regulating their stability, transport, and transcription [35]. In particular, some RBPs have two sides properties. For example, insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1), as an adaptor protein in HCC, is able to specifically bind and recruit lncRNA HULC to the deadenylase, thereby initiating HULC degradation [36]. While overexpression of IGF2BP1 is found to increase the half-life and steady-state levels of linc01138 in HCC cells [37], indicating that IGF2BP1 also has a pro-stabilizing effect. Additionally, in recent years, with the surge in epigenetic research, RNA posttranscriptional modifications have been gradually recognized. m6A is the most common modification of lncRNAs. Studies have shown that m6A readers can act as RBPs to recognize and target m6A-modified lncRNAs; and then regulate lncRNA degradation and transcription [38, 39]. This undoubtedly extends the function of RBPs in regulating lncRNAs expression.

Modes of action of lncRNAs

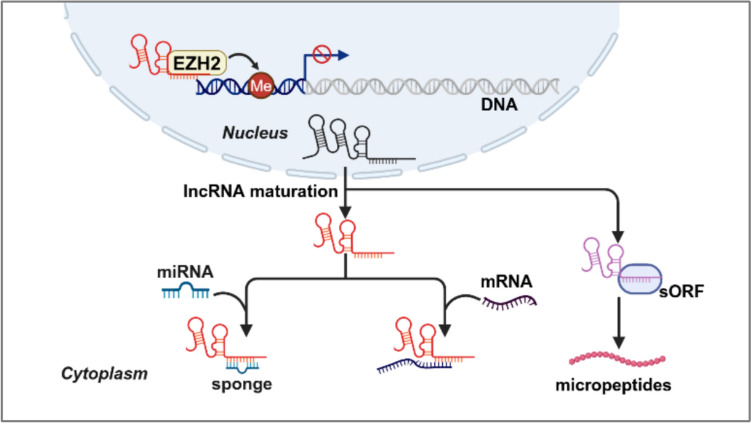

Interest in lncRNAs has rapidly grown as sequencing technologies have progressed and diffused. However, the number of lncRNAs with detailed descriptions is only negligible compared to the number discovered. Generally, lncRNAs regulate gene expression by interacting with DNA, RNA, and proteins. Furthermore, lncRNAs have recently been shown to directly interact with signaling receptors or ribosomes to encode proteins. Either way, the functions of lncRNAs are tightly correlated with their subcellular localization. Therefore, determining the localization pattern of lncRNAs will not only help to address basic scientific questions about lncRNAs functions, but also help to decide on appropriate methods to manipulate them, whether for basic research or for clinical purposes. Here, we summarize the current knowledge of lncRNAs subcellular localization, and propose emerging themes, including the localization of lncRNAs to organelles or macromolecular structures and the involvement of lncRNAs in the encoding of small peptides (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Action modes of nuclear and cytoplasmic lncRNAs. LncRNAs in the nuclear can affect gene transcriptional programs through chromatin remodeling, while lncRNAs in the cytoplasm can regulate the stability and translation of mRNA, act as a "sponge" molecule to recruit miRNA, and even encode some peptides

LncRNAs in the nucleus versus the cytoplasm

The first one to be characterized is lncRNAs located in the nucleus. Compared to protein-coding genes, lncRNAs are particularly enriched in the nucleus rather than in the cytoplasm due to their special structures, such as inefficient splicing, polyadenylation, and harboring cis elements [40]. An early microarray-based screen using polyadenylated RNAs revealed three abundant lncRNA transcripts in nuclear, namely XIST, NEAT1, and MALAT1; and all of which have been reported to be involved in a variety of liver disease processes, including HCC, cirrhosis, NAFLD, and ALD [23, 41, 42]. In the nucleus, the canonical roles of lncRNAs are to mediate transcriptional programs through chromatin remodeling and interactions, as well as construct spatial organization via scaffolding [43]. Among them, it is worth mentioning that lncRNA-DNA hybrids in the nucleus have been shown to accelerate transcriptional induction, thus facilitating organisms to adapt to the environmental stimuli. For example, lncRNA TUG1 can bind to the promoter region of the PGC-1α gene to enhance its promoter activity, thereby upregulating PGC-1α and improving PGC-1α mediated-mitochondrial bioenergetics in a murine model of diabetic nephropathy [44, 45]. Furthermore, studies have shown that epigenetic modifications can affect lncRNAs expressions, and vice-versa. Such as, lncRNAs ANRIL [46] is reported to recruit EZH2 to induce H3K27me3 modification at the KLF2 promoter region, thus repressing KLF2 transcription and inhibiting its mediated cell growth in HCC.

Different from the nucleus, lncRNAs in the cytoplasm have been reported to modulate mRNA stability, translation, and posttranslational modification, or to act as “sponge” molecules to recruit miRNAs for a series of functions. Here, we mainly introduce the role of "sponge" molecules, as it is involved in almost all cellular processes mediated by lncRNAs [47, 48]. For example, in HCC, the upregulated lncRNA SNHG7 promotes HCC development by regulating FOXK2 through sponging miR-122-5p [49]. Additionally, compared to the adjacent non-tumor tissues, the lncRNA CDKN2BAS was remarkably elevated in metastatic HCC tissues. Mechanistically, CDKN2BAS can adsorb miR-153-5p through sponges and then increase the expression of the miR-153-5p target gene ARHGAP18, which plays a role in promoting tumor occurrence and metastasis. Thus, the CDKN2BAS/miR-153-5p/ARHGAP18 signaling axis may provide new clues for understanding the molecular mechanism of HCC progression [50].

LncRNAs in organelles and lncRNAs encoding small peptides

Notably, more and more researchers are turning to the study of the lncRNAs localization in specific organelles and macromolecular structures. For example, a recent study revealed that the differentiation of thermogenic adipocytes leads to the upregulation of the lncRNA-LINC00473. Interestingly, LINC00473 is usually localized in the nucleus at basal state. Once differentiated, LINC00473 shuttles to the cytoplasm and finally localizes to the interface of lipid droplet-mitochondria, where it exists in multimeric complexes with mitochondrial and lipid droplet proteins and regulates lipolysis and mitochondrial function [51]. Additionally, using APEX-RIP, a method that combines engineered ascorbate peroxidase-catalyzed proximity biotinylation of endogenous proteins and RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), reveals a small group of 28 lncRNAs in ER lumen [52]. Compare with the traditional distribution in the nucleus or the cytoplasm, the discovery of lncRNAs subcellular localization will be of great significance for the metabolic organ liver.

Biochemically, lncRNAs are indistinguishable from mRNAs except that they lack protein-coding reading frames. However, deep RNA sequencing has recently revealed that certain lncRNAs have short open reading frames (sORFs); and a considerable number of reports have revealed the existence of stable, functional small peptides (also known as micropeptides), translated from lncRNAs sORFs. For instance, a conserved 99-amino acid microprotein KRASIM, which is encoded by lncRNA NCBP2-AS2, was identified through ribosome profiling [53]. KRASIM overexpression could inhibit the activity of the extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK) signaling pathway by interacting with KRAS protein, which ultimately leads to the suppression of growth and proliferation of HCC cells. Conversely, another small endogenous peptide termed as SMIM30 encoded by linc00998 was found to promote HCC development via activating MAPK signaling pathway [54]. Though the functional mechanisms of lncRNA-encoded small peptides have not been elucidated, probably due to the difficulties in detecting or characterizing such molecules, there is no denying that the small peptides will catch increasing attention in the future.

Functional lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of LD

The pathophysiological process of LD is complex. This section will take HCC, a typical liver disease with a high mortality rate, and NAFLD, a newly emerging liver metabolic disease, as examples to emphasize the pathophysiological role of lncRNA in the development of LD (Table 1).

Table 1.

LncRNAs involved in the pathogenesis of liver diseases

| LncRNA | Feature | Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| LncRNA involved in HCC | ||

| Oncogenic lncRNAs | ||

| HULC | Up | miR-372/ PKA; miR-200a-3p/ZEB1 |

| lncRNA SNHG1 | Up | p53 |

| TUC338 | Up | PCNA |

| MALAT1 | Up | miR-3064-5p/FOXA1/CD24/Src |

| HOTAIR | Up | miR-23b-3p/ E-cadherin |

| Tumor-suppressive lncRNAs | ||

| MEG3 | Down | p53 |

| lincRNA P21 | Down | p53 |

| lncRNA AOC4P | Down | EMT |

| LncRNA involved in NAFLD | ||

| lncRNA uc.372 | Up | miR-195/miR-466-ACC, FAS, SCD1, and CD36 |

| lncRNA HR1 | Down | repressing SREBP-1c promoter activity |

| Gm15622 | Up | miR-742-3p/SREBP-1c |

| MALAT1 | Up | stabilizing nuclear SREBP-1c protein |

| ARSR | Up | PI3K/Akt/SREBP-1c |

| lncRNA SRA | Up | insulin-like growth factor-1 and Akt |

| lncRNA HC | Down | miR-130b-3p/PPARγ |

| lncRNA LSTR | Up | TDP-43/FXR/apoC2 |

| LncRNA H19 | Down | p53/FoxO1 |

HCC

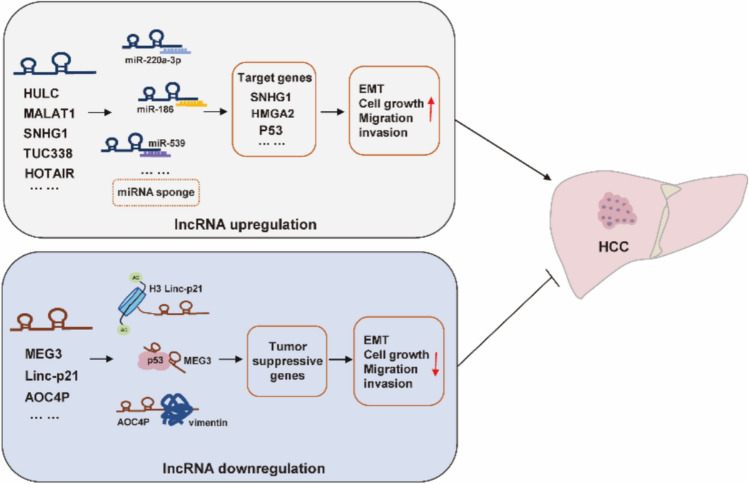

According to the latest cancer statistics, liver cancer has become the seventh most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. There are two main types of primary liver cancers: HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, of which HCC constitutes nearly 90% of all primary liver cancer cases [55]. Current conventional treatment for HCC includes hepatectomy, ablation, and liver transplantation; however, their performance remains far from satisfactory. Recently, several dysregulated lncRNAs have been considered as potential oncogenic and tumor-suppressive factors in HCC, which is consistent with the notion that complicated genetic and epigenetic changes contribute to carcinogenesis. In particular, some HCC-related lncRNAs exist in body fluids and are easy to detect and analyze. For example, lncRNA-WRAP53 obtained from the serum has become an independent prognostic marker for predicting the high recurrence rate of HCC patients. These important roles and unique properties of lncRNAs indicate that they have potential clinical value in the diagnosis and treatment of HCC. In this section, we list some lncRNAs closely related to HCC and discuss their roles (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal expression of lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Several dysregulated lncRNAs have been considered as potential oncogenic or tumor-suppressive factors in HCC, respectively

In addition, chemotherapy is a widely used and effective clinical approach for cancer treatment. Commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs for HCC include 5-fluorouracil (FU), cisplatin (CDDP), oxaliplatin, adriamycin, sorafenib, etc. [56]. Despite these drugs are effective, there are still many challenges related to drug resistance during long-term use. Increasing evidence indicates that lncRNAs represent novel targets for the treatment of HCC resistance [56]. Therefore, we also outlined some molecular mechanisms related to lncRNA and chemotherapy resistance.

Oncogenic and tumor-suppressive lncRNAs

HCC is initiated by the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and the activation of oncogenes, and then expands through the abnormal activation of molecules in multiple signal transduction pathways that control cell proliferation, migration, invasion, autophagy, apoptosis. Therefore, in presenting the function of lncRNAs in HCC, we emphasize how these functions are achieved through oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways.

Regarding oncogenic lncRNAs, the first oncogenic lncRNA reported in human HCC is lncRNA HULC, which is not only upregulated in the liver of HCC, but also has highly specificity for human HCC [57]. A number of studies have confirmed that HULC knockdown in HCC cell lines significantly represses cell proliferation and further impairs HCC cell invasion and migration [34]. Mechanistically, HULC has been mainly studied as miRNA "sponges." For example, lncRNA HULC RNA contains one conserved target site of miR-372. Therefore, HULC can reduce the expression and activity of miR-372, and sequester miR-372 from its target genes by this putative binding site in cells [58]. Additionally, HULC has been reported to accelerate the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells through the miR-200a-3p/ZEB1 signaling pathway [59].

In parallel, data from public microarray data and a cohort study showed that lncRNA SNHG1 was increased in HCC tissues, which was associated with TNM stage but not with tumor size or tumor subtype [60, 61]. In HepG2, upregulated SNHG1 promotes HCC cell proliferation, invasion, and migration; meanwhile, functional assays have shown that SNHG1 may be involved in the negative regulation of miR-195 or pivotal genes in TP53 signaling pathway [62]. TUC338, an ultra-conserved and liver-specific lncRNA with a length of 590 bp, was strikingly increased in HCC cell lines compared with normal human hepatocytes [63]. Studies have shown that silencing of TUC338 inhibits the proliferation of HCC cells. Considering its liver-specific expression characteristics, TUC338 has the potential to be a therapeutic target for HCC.

LncRNA MALAT1, also known as nuclear-enriched transcript 2 (NEAT2), has been reported to be upregulated in human HCCs. Studies have shown that MALAT1 plays an important role in HCC progression and may serve as a novel biomarker for predicting tumor recurrence after liver transplantation. For example, SRSF1 induction and mTOR activation are essential for MALAT1 induced transformation, and Zhang et al. reported that the activated lncRNA MALAT1 can act as a ceRNA to sponge miR-3064-5p, which then targets the FOXA1/CD24/Src pathway to exert antiangiogenic effects in HCC [64]. Moreover, lncRNA HOTAIR is another important molecule in HCC, and its elevated level is often associated with poor prognosis of HCC. Studies have shown that overexpression of HOTAIR could induce epithelial–mesenchymal transitions by downregulating E-cadherin in liver cancer stem cells or by sponging miR-23b-3p in HCC cells [65]. Concomitantly, HOTAIR has also been reported to mediate autophagy in HCC cells together with the autophagy-related factors ATG3 and ATG7 [66].

As for tumor-suppressive lncRNAs, these lncRNAs generally exhibit low expression patterns in HCC, but once inactivated, they rapidly promote HCC progression. For instance, low levels of lncRNA MEG3 have been proved to be a primary feature of many human cancers, including HCC [29]. Mechanistic studies have revealed that the antitumor effect of MEG3 in HCC cells might result from the activation of the classical tumor suppressor protein p53. Another tumor suppressor lncRNA associated with p53 is lincRNA P21, whose levels in hepatocytes and serum are negatively correlated with liver health [67]. It has been reported that knockdown of P21 increases the proliferation ability of HCC cells, whereas P21 overexpression is able to represses hepatic cell proliferation and affect cell apoptosis [68]. The lncRNA AOC4P is a tumor suppressor lncRNA that was recently discovered through microarray analysis of HCC samples and normal adjacent tissues [69]. Both in vitro and in vivo assays have confirmed that AOC4P can suppress HCC cells proliferation and metastasis by enhancing vimentin degradation and suppressing EMT, respectively.

Interestingly, some lncRNAs may play dual roles as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors at different stages of HCC progression [70]. For example, lncRNA H19, an endogenous noncoding single-stranded RNA, functions as an oncogene and a tumor-suppressive lncRNA in the development and progression of HCC. H19 is upregulated as a precursor of miR-675, and miR-675 downregulates the expression of the tumor suppressor gene RB, thereby playing an oncogenic role. In contrast, knockdown of H19 in HCC can promote tumorigenesis or tumor enlargement, suggesting that H19 acts as a tumor suppressor gene in tumors. Together, these results indicate complex mechanisms underlying lncRNAs governing HCC.

LncRNAs in chemotherapy resistance

LncRNA drug resistance has been extensively studied, while the mechanisms by which lncRNAs influence the occurrence of anticancer drug resistance in malignant tumors are intricate and uncertain. For example, LINC01134 is highly expressed in HCC owing to histone demethylation of its promoter by histone demethyltransfer-modifying enzyme (LSD1). It can positively regulate p62 by enhancing the enrichment of SP1 at the p62 promoter, thereby activating the p62-mediated antioxidative stress response pathway. Therefore, LINC01134 is reported to be involved in oxaliplatin resistance in HCC through the LSD1/LINC01134/SP1/p62 axis [71]. In addition, evidence from clinical data suggests that the knockout of NIFK-AS1 sensitizes HCC cells to sorafenib by affecting cancer cell growth and metastasis, indicating that low levels of NIFK-AS1 may be a predictor of the benefit of sorafenib in individualized therapy for HCC [72]. In HCC cells and tissues, lncRNA GAS5 and PTEN expression was significantly decreased, whereas miR-21 expression was significantly increased. GAS5 regulates PTEN expression by sponging miR-21, which affects proliferation and increases resistance of HCC cells to doxorubicin [73]. LncRNA MALAT1, which is highly expressed in HCC, can positively regulate β-catenin, dysregulate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, and consequently attenuates HCC tumorsphere formation efficiency [74].

NAFLD

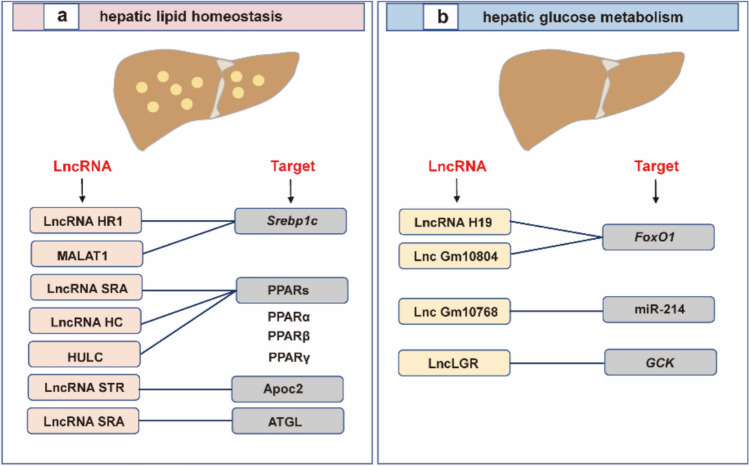

NAFLD is an emerging type of chronic liver diseases characterized by excessive accumulation of hepatic fat in the absence of other competing fatty liver disease etiologies, e.g., alcohol, drugs, and virus. The natural history of NAFLD is complex and usually encompasses steatosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC. Unfortunately, no clinical drug has been approved for the treatment of NAFLD. Imbalances in glucose and lipid metabolism homeostasis are at the heart of NAFLD. Therefore, dissection of the complex pathways or mechanisms of glucose and lipid metabolism is of great significance for the health of patients with diagnosed and potential NAFLD. Here, based on the basic physiological mechanisms of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism, we summarized the latest findings of lncRNAs in the complex research field of NAFLD (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

LncRNAs in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. The current knowledge about the effect of lncRNAs on (a) lipid homeostasis and (b) glucose metabolism

LncRNAs and hepatic lipid homeostasis

Hepatic lipid metabolism is a complex biochemical process involving fatty acid uptake, de novo fatty acid synthesis (also known as de novo lipid synthesis), fatty acid oxidation, hepatic lipid export, lipid droplet formation, and catabolism. However, a large proportion of lncRNA research and development focuses on fatty acid uptake, de novo fatty acid synthesis, and hepatic lipid export. Given that the hallmark of NAFLD is abnormal accumulation of hepatic neutral lipid-triglycerides (TGs) in the liver, and fatty acids are indispensable for the biosynthesis of TGs, it is understandable to explore the effect of lncRNA on fatty acids. For fatty acid uptake, non-esterified fatty acids that are elevated in the serum of NAFLD patients enter hepatocytes through hepatic fatty acid transporters. Although CD36/FAT does not play a major role in fatty acid transport in the normal liver, CD36/FAT is highly inducible and can cause hepatic steatosis under pathological conditions, such as a high-fat diet and excessive alcohol consumption. Studies have shown that lncRNA uc.372 is involved in fatty acid uptake via CD36/FAT [75].

In addition to fatty acid uptake, lncRNA uc.372 has been reported to be involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis by regulating other lipid regulatory factors such as ACC, FASN, and SCD1. Indeed, lncRNAs modulate many transcription factors and enzymes involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway. Srebp1c has been identified as a master transcription factor that promotes the expression of key factors in lipogenesis, including ACC, FAS, SCD1, and HMGCR. Emerging evidence suggested that Srebp1c is a pivotal target of lncRNAs involved in lipid synthesis [76]. For example, the overexpression of lncRNA HR1, a novel human-specific lncRNA, inhibits lipid accumulation in hepatic cells and transgenic mouse models by targeting and repressing Srebp1c promoter activity [76]. While several lncRNAs, including lncRNA H19, Gm15622 [77], MALAT1 [78], and ARSR [79], have been found to stimulate Srebp1c expression to increase hepatic lipid accumulation, indicating that they may be new therapeutic targets against NAFLD. In addition to Srebp1c, partial lncRNAs have also been reported to control lipid synthesis by targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). The lncRNA SRA is the first identified lncRNA to play a potential role in adipogenesis via modulating PPARγ [80], although the mechanism is not yet clear. Additionally, Lan et al. [81] reported that the reduction of lncRNA HC in rats significantly induced PPARγ production by modulating miR-130b-3p, thus leading to increases in hepatic TG levels.

Furthermore, the destruction of intracellular lipid clearance is another important way to worsen liver steatosis. Generally, lipid clearance pathways involve lipid decomposition, fatty acid oxidation, and lipid transport. Recent enrichment analysis of lncRNAs in key metabolic organs has identified that lncRNA LSTR is a liver-specific lncRNA whose expression varies with changes in energy levels or metabolic state [82]. Notably, a decrease in plasma TGs was detected in LSTR knockdown mice, which was probably due to the decreased LSTR altering bile acid composition, resulting in the activation of Apoc2, an important molecule involved in lipid transport. In addition, the lncRNA SRA mentioned earlier not only plays a role in lipogenesis but also inhibits adipose triglyceride lipase ATGL by inhibiting its promoter activity, thus reducing FFA oxidation and promoting hepatic steatosis [83].

LncRNAs and hepatic glucose metabolism

Deregulation of glucose metabolism is another potential manifestation of NAFLD. Despite the infant phase, emerging studies have shown that dysregulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis may be associated with lncRNA-mediated changes in gluconeogenic gene expression. In severe patients, reduction of lncRNA H19 in vivo impairs liver tissue tolerance to glucose, insulin, and pyruvate. Mechanistically, this phenomenon may be related to the impaired insulin signaling and the increased nuclear localization of FOXO1 mediated by H19 [84]. Similar to lncRNA H19, the downregulation of lncRNA MEG3 also mediates the decrease in the expression of FOXO1 and its downstream targets Pck1 and G6pase, thereby improving glucose and insulin tolerance in liver tissue [85]. Although there are other lncRNAs involved in hepatic glucose metabolism, such as Gm10804 [86] and SHGL [87], the precise mechanism of their activation remains unclear.

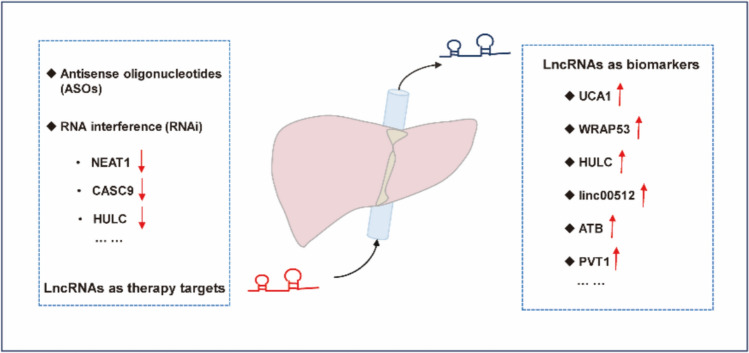

LncRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of liver diseases. However, this diagnostic method carries the risk of bleeding, abdominal visceral penetration, pneumothorax, and even death [88]. Therefore, obtaining noninvasive biomarkers for early stage of LD is of great significance for preventing LD progression. In this regard, lncRNAs in body fluid (circulating lncRNAs) seem to be considered as an alternative diagnostic tool, because they are abundant, noninvasive, and stable in clinical samples. To date, one of the most influential studies in the field of circulating lncRNA diagnostic applications is the successful approval of urine lncRNA PCA3 as a PCa diagnostic biomarker by the FDA [18], which further enables us to realize the great potential of lncRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for LD.

Indeed, associations between circulating lncRNAs expression levels and LD, mainly in HCC, have been evaluated in multiple investigations (Tables 2 and 3). For instance, overexpression of serum HULC was able to discriminate HCC patients from healthy controls (AUC 0.78) [89]. Meanwhile, the plasma UCA1 level could distinguish early stage of HCC with a sensitivity of 93.1% and a specificity of 88.6%, and these values are superior to those of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), the most widely used blood biomarker for HCC in clinical practice (79.3% sensitivity and 82.8% specificity) [90]. More interestingly, a recent study showed that the level of serum extracellular vesicle (EV)-derived linc00853 was upregulated in both AFP-positive and AFP-negative early stage of HCC patients [91], indicating that linc00853 may partially compensate for the diagnostic results of AFP in early stage of HCC.

Table 2.

LncRNAs as diagnosis biomarkers in liver diseases

| LncRNA | Feature | Cases | Control | Control condition | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | Up | 90 | 77 | HL | 0.78 | ||

| Linc00974 | Up | 150 | 150 | pre- and postoperative | 51.1 | 95.6 | 0.733 |

| UCA1 | Up | 82 | 44 | HL | 92.7 | 82.1 | 0.861 |

| Up | 82 | 34 | CHC | 61 | 71 | 0.728 | |

| Up | 34 | 44 | HL | 76.5 | 64.5 | 0.728 | |

| Up | 70 | 38 | HL | 91.4 | 88.6 | 0.91 | |

| Up | 70 | 32 | CHC | 71.4 | 87.5 | 0.838 | |

| Up | 32 | 38 | HL | 68.8 | 67.4 | 0.76 | |

| WRAP53 | Up | 82 | 44 | HL | 85.4 | 82.1 | 0.896 |

| Up | 82 | 34 | CHC | 85.4 | 71 | 0.787 | |

| Up | 34 | 44 | HL | 82.4 | 91 | 0.876 | |

| LINC01225 | Up | 66 | 70 | HL | 76.1 | 44.3 | 0.886 |

| DANCR | Up | 52 | 43 | HL/CHB/cirrhosis | 83.8 | 72.7 | 0.868 |

| Up | 52 | 29 | CHB | 80.8 | 84.3 | 0.864 | |

| JPX | Down | 42 | 68 | HL | 100 | 52.4 | 0.814 |

| MALAT1 | Up | 88 | 28 | hepatic disease | 51.1 | 89.3 | 0.66 |

| SPRY4‑IT1 | Up | 145 | 63 | HL | 87.3 | 50 | 0.702 |

| ENSG00000258332.1 | Up | 60 | 96 | CHB | 71.6 | 83.4 | 0.719 |

| LINC00635 | Up | 60 | 96 | CHB | 76.2 | 77.7 | 0.75 |

| LRB1 | Up | 326 | 73 | HL | 92.4 | 71.9 | 0.892 |

| D16366 | Down | 58 | 85 | HL | 65.5 | 84.6 | 0.752 |

| NONHSAT053785 | Up | 112 | 195 | CHB and HL | 73.2 | 74.4 | 0.801 |

Table 3.

LncRNAs combined with other markers for liver disease diagnosis

| LncRNA | Feature | Cases | Control | Control condition | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC and lnc00152 | Up | 90 | 77 | HL | 0.89 | ||

| Linc00974 and KRT19 | Up | 150 | 150 | pre- and postoperative | 58.9 | 92.2 | 0.764 |

| RP11–160H22.5, XLOC_014172, and LOC149086 | Up | 217 | 250 | HL | 85 | 85 | 0.896 |

| UCA1, WRAP53 and AFP | Up | 82 | 78 | HL and CHC | 100 | 62.8 | |

| JUN, and UCA1 | Up | 64 | 38 | HL | 100 | 80 | |

| AFP and JPX | Up | 42 | 68 | HL | 97.1 | 72.2 | 0.905 |

| uc002mbe.2 and PVT1 | Up | 71 | 64 | HL | 60.6 | 90.6 | 0.764 |

| ENSG00000258332.1 and LINC00635 and AFP | Up | 60 | 96 | CHB | 83.6 | 87.7 | 0.894 |

| LRB1, AFP and DCP | Up | 326 | 73 | HL | 86.3 | 87.6 | 0.971 |

| ENSG00000248932.1, ENST00000440688.1 and ENST00000457302.2, and AFP | Up | 200 | 400 | HL and CHC | 0.90 |

Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that certain candidate lncRNAs can appear simultaneously in different disease etiologies, leading to reduced reliability. In response to this problem, multiple studies have attempted to integrate lncRNAs and other biomarkers to construct predictive models, and some progress has been made. For instance, the combination of serum lncRNAs UCA1 and WRAP53 with AFP increases the sensitivity to 100% in the diagnosis of HCC [92]. The diagnostic value for HCC was much higher in the combination of two upregulated serum lncRNAs PVT1, uc002mbe.2, and AFP than that of AFP alone [93]. In addition, there are still some issues that cannot be solved for the time being. For example, (1) although lncRNAs are more stable than mRNAs, it is easily affected by sampling time, storage conditions, and detection methods during detection. (2) Due to differences in individual genetic background (such as SNP), epigenetic modifications (such as methylation), and disease subtypes, the expression pattern of lncRNA varies. (3) There are a large number of lncRNAs, but the functions of more than 90% of lncRNAs have not been fully resolved. Therefore, there is still a long way to go before lncRNA can be used as a biomarker in clinical practice.

LncRNAs as potential therapeutic targets

Since the discovery of lncRNAs, researchers have been looking forward to utilizing this new type of molecule to break the deadlock in the clinical treatment of many diseases, including liver disease. In particular, the prevalence of RNA-based therapeutic technologies in recent years has provided tremendous opportunities for lncRNA therapy. LncRNA-based therapies usually select specific lncRNAs as novel druggable targets and then reduce their transcript levels or attenuate their molecular functions. In this section, our aim is to show the currently applied therapeutic strategies for regulating expression levels of lncRNAs in LD (Fig. 5 and Table 4).

Fig. 5.

LncRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in the liver. Circulating lncRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in liver disease because they are abundant, noninvasive, and are stable in clinical samples. Till now, RNA-based therapies usually select specific lncRNAs as novel druggable targets, and then reduce their transcript levels or attenuate their molecular functions

Table 4.

Comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of siRNA and ASO

| Item | siRNA | ASO |

|---|---|---|

| State | dsRNA | Single-stranded DNA or RNA |

| Target location | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm and Nucleus |

| Mechanism of action | RNA degradation | RNA degradation, and Splicing regulation, steric hindrance |

| Advantages |

High silencing efficiency; High specificity; A single dose can maintain the effect in cells for several weeks |

Flexible mechanism of action; Diverse chemical modifications; Some ASOs can be delivered to targets without complex carriers |

| Disadvantages | The double-stranded structure is negatively charged and needs to rely on a carrier to penetrate the cell membrane; Immunogenicity risk; Difficult to effectively target RNA in the nucleus |

High risk of off-target effects, Poor stability; High doses may cause cytotoxicity; Immunogenicity risk |

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting lncRNA

SiRNAs are short (20–25 nucleotides) double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) that must be loaded into other proteins to form an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and then mediate RNA silencing. Several studies have explored the potential of siRNA in regulating the expression of lncRNAs for the purpose of treating LD. LncRNA HULC can be functioned as a ceRNA to mediate EMT in cytoplasm; and silencing HULC by siRNA effectively inhibits the invasion and migration of HCC cells [94]. Besides, knockdown of NEAT1 [95] and CASC9 [96] by siRNA inhibited the proliferation of HCC cells and stopped cell cycle progression. Notably, recent studies have indicated that another important aspect of siRNA-targeting lncRNAs for HCC treatment is to reduce treatment resistance. Sorafenib is the first‑line treatment for advanced HCC. Xu et al. reported that siRNA suppression of H19 sensitizes HCC cells to sorafenib in vitro, thus achieving greater treatment efficacy [97]. Tang et al. also obtained similar results by using siRNA-targeting lncRNA HOTAIR [98]. These results suggest that the combined use of siRNA and small-molecule anticancer drugs may provide a new direction for the development of future tumor treatment.

In addition to chemoresistance, lncRNAs have also been shown to be involved in radiation resistance in HCC. For example, lnc TP73-AS1 is a highly expressed lncRNA in radioresistant tumor tissues, and a recent study silencing lncRNA TP73-AS1 by siRNA showed increased radiosensitivity in HCC treatment [99]. Research on radioresistance is a very meaningful aspect of lncRNAs in clinical trials, which may provide us with a new perspective on the interaction between lncRNAs and DNA, and it deserves further study.

Of course, siRNAs have also shown favorable treatment effects against other liver diseases by targeting lncRNAs. For example, Song et al. knocked down lncRNA AK012226 with siRNA, thereby inhibiting lipid accumulation and delaying NAFLD progression in mice [100]. In another study, siRNA-targeting AK139328 was applied to attenuate ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse liver [101]. These results further indicate that siRNA targeting and silencing of critical lncRNAs appear to be particularly promising for liver disease treatment.

Despite the promising prospects, there are still some problems. For example, there are currently no candidate lncRNAs suitable for designing for clinical studies, including the above-mentioned ones. This may be due to a lack of experimental data on the specific role of lncRNAs in the development of liver disease. Additionally, the therapeutic effect depends largely on whether the siRNA can be successfully delivered to the liver. Some key issues in siRNA design, including the stability of siRNA and its unintended off-target effects, have not yet been resolved. At the same time, when siRNA is delivered into cells, it may activate innate immune receptors such as TLR3, triggering a validation response. Therefore, repurposing drugs and providing vitamin D variants as preventive agents with immunomodulatory effects during siRNA delivery may have a positive impact on HCC [102].

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting lncRNA

ASOs are synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides with lengths between 8 and 50 nucleotides. Similar to siRNAs, ASOs have shown great therapeutic effects in liver disease. For example, Fu et al. reported that silencing linc00210 mediated by ASOs effectively disrupted the self-renewal and invasion ability of HCC cells [103]. In addition, Wang et al. observed significant antitumorigenic effects in humanized HCC models by interfering with the expression of lncRNA HAND2-AS1 using ASOs [104]. Currently, ASO strategies are not popular for inhibiting lncRNAs. Considering its higher specificity and fewer off-target effects compared to siRNA, it is reasonable to speculate that the rapid growth of interest in lncRNA biology and technological breakthroughs will accelerate its entry into the clinical field.

Recommendation and future perspectives

Currently, our understanding of the regulatory roles of lncRNAs in liver diseases has only touched the tip of the iceberg, compared to their roles in modulating protein-coding genes, and further in-depth research is needed in many areas in the future. For example, lncRNAs with function annotation only account for a small part of the total number, and the biological functions of most lncRNAs remain unknown. Therefore, in addition to continuing to explore the functions of lncRNA using laboratory methods, methods such as software development are also needed to predict their unknown functions. In addition, the expression levels of lncRNAs are correlated with disease state, but how to detect the expression changes of lncRNAs in real time are also a problem we need to consider. Overall, only a few lncRNAs (such as lncRNA PCA3) have passed FDA certification so far, and most studies remain in the retrospective cohort stage. Therefore, we urgently need to conduct multicenter prospective validation to promote the clinical transformation barriers of lncRNA.

Conclusion

Emerging evidence has demonstrated the importance of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of various liver diseases including HCC and NAFLD. We reviewed recent findings on the dysregulated lncRNAs involved in liver diseases, including the aberrant regulation patterns of lncRNA expression, the modes of action of lncRNAs, and the biological significance of lncRNAs. We also list some lncRNAs with potential for clinical practice. Despite the comprehensiveness, the details of many lncRNAs mechanisms of action have not been fully discussed due to insufficient experimental validation. In addition, recent studies have shown that lncRNA structure can also affect its function, but we do not cover this in this article. In summary, despite the many challenges currently faced, the significance and value of lncRNAs in disease cannot be ignored. Through in-depth study of the function and mechanism of lncRNA, it is expected to reveal more mysteries of life activities, and provide new ideas and methods for disease treatment and drug development.

Abbreviations

- ACC

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ASOs

Antisense oligonucleotides

- ceRNAs

Competitive endogenous RNAs

- DNMTs

DNA methyltransferases

- dsRNAs

Double-stranded RNAs

- EMT

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

- FASN

Fatty acid biosynthetic enzyme

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- LD

Liver disease

- LncRNAs

Long noncoding RNAs

- m6A

N6-methyladenosine

- Myc

MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- ncRNA

Noncoding RNAs

- lincRNAs

Intergenic long noncoding RNAs

- lncRNAs

Long noncoding RNAs

- RBPs

RNA-binding proteins

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- smORFS

Small open reading frames

- Srebp1c

Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c

- SP

Sp1 transcription factor

- TFs

Transcription factors

- TG

Triglyceride

Author contributions

Xiaoying Li participated in study design. Ningning Chen and Xiaoying Li wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Data visualization was performed by Yunxia Li and Ningning Chen. Funding was done by Xiaoying Li.

Funding

This study was supported and funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant Numbers ZR2022MH235).

Data availability

Data sharing was not applicable to this article because no new data were created or analyzed in this study. No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhong Q, Zhou R, Huang YN, Huang RD, Li FR, Chen HW, et al. Frailty and risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and other chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2025;82(3):427–37. 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali NA, Hamdy NM, Gibriel AA, El Mesallamy HO. Investigation of the relationship between CTLA4 and the tumor suppressor RASSF1A and the possible mediating role of STAT4 in a cohort of Egyptian patients infected with hepatitis C virus with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Virol. 2021;166(6):1643–51. 10.1007/s00705-021-04981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):516–37. 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abaza T, El-Aziz MKA, Daniel KA, Karousi P, Papatsirou M, Fahmy SA, et al. Emerging Role of Circular RNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:22. 10.3390/ijms242216484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Xiao J, Wang F, Yuan Y, Gao J, Xiao L, Yan C, et al. Epidemiology of liver diseases: global disease burden and forecasted research trends. Sci China Life Sci. 2025;68(2):541–57. 10.1007/s11427-024-2722-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youssef SS, Hamdy NM. SOCS1 and pattern recognition receptors: TLR9 and RIG-I; novel haplotype associations in Egyptian fibrotic/cirrhotic patients with HCV genotype 4. Adv Virol. 2017;162(11):3347–54. 10.1007/s00705-017-3498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Mesallamy HO, Hamdy NM, Rizk HH, El-Zayadi AR. Apelin serum level in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011: 703031. 10.1155/2011/703031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge WJ, Huang H, Wang T, Zeng WH, Guo M, Ren CR, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;248: 154604. 10.1016/j.prp.2023.154604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginès P, Krag A, Abraldes JG, Solà E, Fabrellas N, Kamath PS. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1359–76. 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammad R, Eldosoky MA, Elmadbouly AA, Aglan RB, AbdelHamid SG, Zaky S, et al. Monocytes subsets altered distribution and dysregulated plasma hsa-miR-21-5p and hsa-miR-155-5p in HCV-linked liver cirrhosis progression to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(17):15349–64. 10.1007/s00432-023-05313-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammad R, Aglan RB, Mohammed SA, Awad EA, Elsaid MA, Bedair HM, et al. Cytotoxic T Cell Expression of Leukocyte-Associated Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor-1 (LAIR-1) in Viral Hepatitis C-Mediated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20). 10.3390/ijms232012541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Herman AB, Tsitsipatis D, Gorospe M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol Cell. 2022;82(12):2252–66. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridges MC, Daulagala AC, Kourtidis A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. J Cell Biol. 2021;220(2). 10.1083/jcb.202009045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Erber J, Herndler-Brandstetter D. Regulation of T cell differentiation and function by long noncoding RNAs in homeostasis and cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1181499. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1181499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiStefano JK, Gerhard GS. Long Noncoding RNAs and Human Liver Disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2022;17:1–21. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-042320-115255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Zhang X, Chen W, Hu X, Li J, Liu C. Regulatory roles of long noncoding RNAs implicated in cancer hallmarks. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(4):906–16. 10.1002/ijc.32277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilieva M, Uchida S. Perspectives of LncRNAs for therapy. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2022;38(6):915–7. 10.1007/s10565-022-09779-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemos AEG, Matos ADR, Ferreira LB, Gimba ERP. The long non-coding RNA PCA3: an update of its functions and clinical applications as a biomarker in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2019;10(61):6589–603. 10.18632/oncotarget.27284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudriashov V, Sufianov A, Mashkin A, Beilerli A, Ilyasova T, Liang Y, et al. The role of long non-coding RNAs in carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the liver. Non-coding RNA research. 2023;8(3):294–301. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2023.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarandi PK, Ghiasi M, Heiat M. The role and function of lncRNA in ageing-associated liver diseases. RNA Biol. 2025;22(1):1–8. 10.1080/15476286.2024.2440678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Z, Peng B, Liang Q, Chen X, Cai Y, Zeng S, et al. Construction of a Ferroptosis-Related Nine-lncRNA Signature for Predicting Prognosis and Immune Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 719175. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.719175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Han S, Zeng Z, Zheng H, Li Y, Wang F, et al. Decreased lncRNA HNF4A-AS1 facilitates resistance to sorafenib-induced ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma by reprogramming lipid metabolism. Theranostics. 2024;14(18):7088–110. 10.7150/thno.99197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Z, Zhou JK, Peng Y, He W, Huang C. The role of long noncoding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):77. 10.1186/s12943-020-01188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin HP, Rea M, Wang Z, Yang C. Down-regulation of lncRNA MEG3 promotes chronic low dose cadmium exposure-induced cell transformation and cancer stem cell-like property. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2021;430: 115724. 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding G, Li W, Liu J, Zeng Y, Mao C, Kang Y, et al. LncRNA GHET1 activated by H3K27 acetylation promotes cell tumorigenesis through regulating ATF1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:326–31. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Xie Y, Xu X, Yin Y, Jiang R, Deng L, et al. Bidirectional transcription of Linc00441 and RB1 via H3K27 modification-dependent way promotes hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(3): e2675. 10.1038/cddis.2017.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Gewely MR. Dysregulation of Regulatory ncRNAs and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25(1). 10.3390/ijms25010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Xie R, Wang M, Zhou W, Wang D, Yuan Y, Shi H, et al. Long Non-Coding RNA (LncRNA) UFC1/miR-34a Contributes to Proliferation and Migration in Breast Cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7149–57. 10.12659/msm.917562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo J, Zhang N, Liu G, Zhang A, Liu X, Zheng J. Upregulated expression of long non-coding RNA MEG3 serves as a prognostic biomarker in severe pneumonia children and its regulatory mechanism. Bioengineered. 2021;12(1):7120–31. 10.1080/21655979.2021.1979351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oksuz O, Henninger JE, Warneford-Thomson R, Zheng MM, Erb H, Vancura A, et al. Transcription factors interact with RNA to regulate genes. Mol Cell. 2023;83(14):2449-63.e13. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran DDH, Kessler C, Niehus SE, Mahnkopf M, Koch A, Tamura T. Myc target gene, long intergenic noncoding RNA, Linc00176 in hepatocellular carcinoma regulates cell cycle and cell survival by titrating tumor suppressor microRNAs. Oncogene. 2018;37(1):75–85. 10.1038/onc.2017.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma D, Gao X, Liu Z, Lu X, Ju H, Zhang N. Exosome-transferred long non-coding RNA ASMTL-AS1 contributes to malignant phenotypes in residual hepatocellular carcinoma after insufficient radiofrequency ablation. Cell Prolif. 2020;53(9): e12795. 10.1111/cpr.12795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gandhy SU, Imanirad P, Jin UH, Nair V, Hedrick E, Cheng Y, et al. Specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors and metformin regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA HULC. Oncotarget. 2015;6(28):26359–72. 10.18632/oncotarget.4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghafouri-Fard S, Esmaeili M, Taheri M, Samsami M. Highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC): An update on its role in carcinogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9071–9. 10.1002/jcp.29765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao ZT, Yang YM, Sun MM, He Y, Liao L, Chen KS, et al. New insights into the interplay between long non-coding RNAs and RNA-binding proteins in cancer. Cancer communications (London, England). 2022;42(2):117–40. 10.1002/cac2.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hämmerle M, Gutschner T, Uckelmann H, Ozgur S, Fiskin E, Gross M, et al. Posttranscriptional destabilization of the liver-specific long noncoding RNA HULC by the IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1). Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1703–12. 10.1002/hep.26537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z, Zhang J, Liu X, Li S, Wang Q, Di C, et al. The LINC01138 drives malignancies via activating arginine methyltransferase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1572. 10.1038/s41467-018-04006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang H, Weng H, Chen J. m(6)A Modification in Coding and Non-coding RNAs: Roles and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(3):270–88. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patil DP, Pickering BF, Jaffrey SR. Reading m(6)A in the Transcriptome: m(6)A-Binding Proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28(2):113–27. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao RW, Wang Y, Chen LL. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(5):542–51. 10.1038/s41556-019-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Mauro S, Scamporrino A, Filippello A, Di Pino A, Scicali R, Malaguarnera R, et al. Clinical and Molecular Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Staging of NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21). 10.3390/ijms222111905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Han S, Zhang T, Kusumanchi P, Huda N, Jiang Y, Yang Z, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in liver diseases: Focusing on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol-related liver disease, and cholestatic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26(4):705–14. 10.3350/cmh.2020.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melé M, Rinn JL. “Cat’s Cradling” the 3D Genome by the Act of LncRNA Transcription. Mol Cell. 2016;62(5):657–64. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long J, Badal SS, Ye Z, Wang Y, Ayanga BA, Galvan DL, et al. Long noncoding RNA Tug1 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Investig. 2016;126(11):4205–18. 10.1172/jci87927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chédin F. Nascent Connections: R-Loops and Chromatin Patterning. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2016;32(12):828–38. 10.1016/j.tig.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang MD, Chen WM, Qi FZ, Xia R, Sun M, Xu TP, et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and regulates cell apoptosis by epigenetic silencing of KLF2. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:50. 10.1186/s13045-015-0146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkatesh J, Wasson MD, Brown JM, Fernando W, Marcato P. LncRNA-miRNA axes in breast cancer: Novel points of interaction for strategic attack. Cancer Lett. 2021;509:81–8. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Xu T, Liu L, Zhang W, Zhao C, Li S, et al. LMSM: A modular approach for identifying lncRNA related miRNA sponge modules in breast cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020;16(4): e1007851. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Z, Gao J, Huang S. LncRNA SNHG7 Promotes the HCC Progression Through miR-122-5p/FOXK2 Axis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(3):925–35. 10.1007/s10620-021-06918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Huang X, Wang W, Xie H, Li J, Hu Z, et al. LncRNA CDKN2BAS predicts poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes metastasis via the miR-153-5p/ARHGAP18 signaling axis. Aging. 2018;10(11):3371–81. 10.18632/aging.101645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran KV, Brown EL, DeSouza T, Jespersen NZ, Nandrup-Bus C, Yang Q, et al. Human thermogenic adipocyte regulation by the long noncoding RNA LINC00473. Nat Metab. 2020;2(5):397–412. 10.1038/s42255-020-0205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaewsapsak P, Shechner DM, Mallard W, Rinn JL, Ting AY. Live-cell mapping of organelle-associated RNAs via proximity biotinylation combined with protein-RNA crosslinking. eLife. 2017;6. 10.7554/eLife.29224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Xu W, Deng B, Lin P, Liu C, Li B, Huang Q, et al. Ribosome profiling analysis identified a KRAS-interacting microprotein that represses oncogenic signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(4):529–42. 10.1007/s11427-019-9580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pang Y, Liu Z, Han H, Wang B, Li W, Mao C, et al. Peptide SMIM30 promotes HCC development by inducing SRC/YES1 membrane anchoring and MAPK pathway activation. J Hepatol. 2020;73(5):1155–69. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng J, Wang S, Xia L, Sun Z, Chan KM, Bernards R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signaling pathways and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):35. 10.1038/s41392-024-02075-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan D, Chen Y, Li X, Li J, Zhao Y, Shen J, et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Potential Biomarkers and Targets for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Therapy and Diagnosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(1):220–35. 10.7150/ijbs.50730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He J, Yang T, He W, Jiang S, Zhong D, Xu Z, et al. Liver X receptor inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via regulating HULC/miR-134-5p/FOXM1 axis. Cell Signal. 2020;74: 109720. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shaker O, Mahfouz H, Salama A, Medhat E. Long Non-Coding HULC and miRNA-372 as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Reports of biochemistry & molecular biology. 2020;9(2):230–40. 10.29252/rbmb.9.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, Moustafa T, Stradner M, Strohmaier HM, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):330–42. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao S, Xu X, Wang Y, Zhang W, Wang X. Diagnostic utility of plasma lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(3):3305–13. 10.3892/mmr.2018.9336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou L, Zhang Q, Cheng J, Shen X, Li J, Chen M, et al. LncRNA SNHG1 upregulates FANCD2 and G6PD to suppress ferroptosis by sponging miR-199a-5p/3p in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug discoveries & therapeutics. 2023;17(4):248–56. 10.5582/ddt.2023.01035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang M, Wang W, Li T, Yu X, Zhu Y, Ding F, et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 predicts a poor prognosis and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;80:73–9. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wen HJ, Walsh MP, Yan IK, Takahashi K, Fields A, Patel T. Functional Modulation of Gene Expression by Ultraconserved Long Non-coding RNA TUC338 during Growth of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. iScience. 2018;2:210–20. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Zhang P, Ha M, Li L, Huang X, Liu C. MicroRNA-3064-5p sponged by MALAT1 suppresses angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting the FOXA1/CD24/Src pathway. Faseb j. 2020;34(1):66–81. 10.1096/fj.201901834R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang T, He X, Chen A, Tan K, Du X. Retraction notice to “LncRNA HOTAIR contributes to the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma by enhancing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via sponging miR-23b-3p from ZEB1” [Gene 670 (2018) 114–122]. Gene. 2022;810: 146065. 10.1016/j.gene.2021.146065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang L, Zhang X, Li H, Liu J. The long noncoding RNA HOTAIR activates autophagy by upregulating ATG3 and ATG7 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol BioSyst. 2016;12(8):2605–12. 10.1039/c6mb00114a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang N, Fu Y, Zhang H, Sima H, Zhu N, Yang G. LincRNA-p21 activates endoplasmic reticulum stress and inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(29):28151–63. 10.18632/oncotarget.4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng J, Dong P, Mao Y, Chen S, Wu X, Li G, et al. lincRNA-p21 inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis via p21. FEBS J. 2015;282(24):4810–21. 10.1111/febs.13544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang TH, Lin YS, Chen Y, Yeh CT, Huang YL, Hsieh TH, et al. Long non-coding RNA AOC4P suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by enhancing vimentin degradation and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):23342–57. 10.18632/oncotarget.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshimizu T, Miroglio A, Ripoche MA, Gabory A, Vernucci M, Riccio A, et al. The H19 locus acts in vivo as a tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(34):12417–22. 10.1073/pnas.0801540105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma L, Xu A, Kang L, Cong R, Fan Z, Zhu X, et al. LSD1-Demethylated LINC01134 Confers Oxaliplatin Resistance Through SP1-Induced p62 Transcription in HCC. Hepatology. 2021;74(6):3213–34. 10.1002/hep.32079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen YT, Xiang D, Zhao XY, Chu XY. Upregulation of lncRNA NIFK-AS1 in hepatocellular carcinoma by m(6)A methylation promotes disease progression and sorafenib resistance. Hum Cell. 2021;34(6):1800–11. 10.1007/s13577-021-00587-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang C, Ke S, Li M, Lin C, Liu X, Pan Q. Downregulation of LncRNA GAS5 promotes liver cancer proliferation and drug resistance by decreasing PTEN expression. Molecular genetics and genomics : MGG. 2020;295(1):251–60. 10.1007/s00438-019-01620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cao Y, Zhang F, Wang H, Bi C, Cui J, Liu F, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 mediates doxorubicin resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating miR-3129-5p/Nova1 axis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(1):279–92. 10.1007/s11010-020-03904-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guo J, Fang W, Sun L, Lu Y, Dou L, Huang X, et al. Ultraconserved element uc.372 drives hepatic lipid accumulation by suppressing miR-195/miR4668 maturation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):612. 10.1038/s41467-018-03072-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Li D, Cheng M, Niu Y, Chi X, Liu X, Fan J, et al. Identification of a novel human long non-coding RNA that regulates hepatic lipid metabolism by inhibiting SREBP-1c. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13(3):349–57. 10.7150/ijbs.16635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma M, Duan R, Shen L, Liu M, Ji Y, Zhou H, et al. The lncRNA Gm15622 stimulates SREBP-1c expression and hepatic lipid accumulation by sponging the miR-742-3p in mice. J Lipid Res. 2020;61(7):1052–64. 10.1194/jlr.RA120000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yan C, Chen J, Chen N. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance by increasing nuclear SREBP-1c protein stability. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22640. 10.1038/srep22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang M, Chi X, Qu N, Wang C. Long noncoding RNA lncARSR promotes hepatic lipogenesis via Akt/SREBP-1c pathway and contributes to the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;499(1):66–70. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu S, Xu R, Gerin I, Cawthorn WP, Macdougald OA, Chen XW, et al. SRA regulates adipogenesis by modulating p38/JNK phosphorylation and stimulating insulin receptor gene expression and downstream signaling. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4): e95416. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lan X, Wu L, Wu N, Chen Q, Li Y, Du X, et al. Long Noncoding RNA lnc-HC Regulates PPAR gamma-Mediated Hepatic Lipid Metabolism through miR-130b-3p. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids. 2019;18:954–65. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li P, Ruan X, Yang L, Kiesewetter K, Zhao Y, Luo H, et al. A liver-enriched long non-coding RNA, lncLSTR, regulates systemic lipid metabolism in mice. Cell Metab. 2015;21(3):455–67. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen G, Yu D, Nian X, Liu J, Koenig RJ, Xu B, et al. LncRNA SRA promotes hepatic steatosis through repressing the expression of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL). Sci Rep. 2016;6:35531. 10.1038/srep35531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Goyal N, Tiwary S, Kesharwani D, Datta M. Long non-coding RNA H19 inhibition promotes hyperglycemia in mice by upregulating hepatic FoxO1 levels and promoting gluconeogenesis. J Mol Med (Berl). 2019;97(1):115–26. 10.1007/s00109-018-1718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu X, Wu YB, Zhou J, Kang DM. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 promotes hepatic insulin resistance via increasing FoxO1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469(2):319–25. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li T, Huang X, Yue Z, Meng L, Hu Y. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA Gm10804 suppresses disorders of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Biochem Funct. 2020;38(7):839–46. 10.1002/cbf.3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang J, Yang W, Chen Z, Chen J, Meng Y, Feng B, et al. Long Noncoding RNA lncSHGL Recruits hnRNPA1 to Suppress Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Lipogenesis. Diabetes. 2018;67(4):581–93. 10.2337/db17-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharpton SR, Schnabl B, Knight R, Loomba R. Current Concepts, Opportunities, and Challenges of Gut Microbiome-Based Personalized Medicine in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2020. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li J, Wang X, Tang J, Jiang R, Zhang W, Ji J, et al. HULC and Linc00152 Act as Novel Biomarkers in Predicting Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2015;37(2):687–96. 10.1159/000430387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El-Tawdi AH, Matboli M, El-Nakeep S, Azazy AE, Abdel-Rahman O. Association of long noncoding RNA and c-JUN expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10(7):869–77. 10.1080/17474124.2016.1193003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim SS, Baek GO, Ahn HR, Sung S, Seo CW, Cho HJ, et al. Serum small extracellular vesicle-derived LINC00853 as a novel diagnostic marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(10):2646–59. 10.1002/1878-0261.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kamel MM, Matboli M, Sallam M, Montasser IF, Saad AS, El-Tawdi AHF. Investigation of long noncoding RNAs expression profile as potential serum biomarkers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res. 2016;168:134–45. 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu J, Han J, Zhang J, Li G, Liu H, Cui X, et al. The long noncoding RNAs PVT1 and uc002mbe.2 in sera provide a new supplementary method for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. Medicine. 2016;95(31):e4436. 10.1097/md.0000000000004436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Zhang H, Li S, Xu H, Sun L, Zhu Z, Yao Z. Interference of miR-107 with Atg12 is inhibited by HULC to promote metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. MedComm (2020). 2020;1(2):165–77. 10.1002/mco2.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Ling ZA, Xiong DD, Meng RM, Cen JM, Zhao N, Chen G, et al. LncRNA NEAT1 Promotes Deterioration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on In Vitro Experiments, Data Mining, and RT-qPCR Analysis. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2018;48(2):540–55. 10.1159/000491811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Klingenberg M, Groß M, Goyal A, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Miersch T, Ernst AS, et al. The Long Noncoding RNA Cancer Susceptibility 9 and RNA Binding Protein Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein L Form a Complex and Coregulate Genes Linked to AKT Signaling. Hepatology. 2018;68(5):1817–32. 10.1002/hep.30102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu Y, Liu Y, Li Z, Li H, Li X, Yan L, et al. Long non-coding RNA H19 is involved in sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma by upregulating miR-675. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(1):165–73. 10.3892/or.2020.7608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tang X, Zhang W, Ye Y, Li H, Cheng L, Zhang M, et al. LncRNA HOTAIR Contributes to Sorafenib Resistance through Suppressing miR-217 in Hepatic Carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:9515071. 10.1155/2020/9515071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Statement of Retraction. Down-regulated lncRNA TP73-AS1 reduces radioresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma via the PTEN/Akt signaling pathway. Cell Cycle. 2023;22(14–16):1802. 10.1080/15384101.2023.2211863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen X, Xu Y, Zhao D, Chen T, Gu C, Yu G, et al. LncRNA-AK012226 Is Involved in Fat Accumulation in db/db Mice Fatty Liver and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Cell Model. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:888. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen Z, Jia S, Li D, Cai J, Tu J, Geng B, et al. Silencing of long noncoding RNA AK139328 attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse livers. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11): e80817. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen YC, Chiang YF, Lin YJ, Huang KC, Chen HY, Hamdy NM, et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2023;15(13). 10.3390/nu15132830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Fu X, Zhu X, Qin F, Zhang Y, Lin J, Ding Y, et al. Retraction Note to: Linc00210 drives Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation and liver tumor progression through CTNNBIP1-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):161. 10.1186/s12943-022-01633-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Y, Zhu P, Luo J, Wang J, Liu Z, Wu W, et al. LncRNA HAND2-AS1 promotes liver cancer stem cell self-renewal via BMP signaling. Embo j. 2019;38(17): e101110. 10.15252/embj.2018101110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing was not applicable to this article because no new data were created or analyzed in this study. No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.