Abstract

Electrochemical surface plasmon resonance (ESPR) based biosensors play significant role in cancer detection due to its ability for real-time analysis and rapid detection. Herein, ESPR based biosensor was designed employing three different coupling strategies for the detection of cancer biomarker α-fetoprotein (AFP), a liver cancer biomarker. AFP antibody was immobilized on gold coated glass sensor disk using three different coupling strategies viz. (i) 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide / N-hydroxy succinamide (EDC/NHS), (ii) ethylene diamine/ glutaraldehyde (EDA/GA) and (iii) polyaniline/glutaraldehyde (PANI/GA) strategies. Among the three coupling strategies, immobilization via EDA/GA strategy afforded highest sensitivity (28°/(ng/ml)) with reasonable linear range (0.5-3 ng/ml) and whereas EDC/NHS strategy afforded wide linear range (5–70 ng/ml) with reasonable sensitivity (2.12°/(ng/ml). Immobilization efficiency and interaction steps involved in the sensor construction were investigated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. The sensor constructed using EDC/NHS strategy was validated by quantifying AFP in human blood serum samples, where the results are consistent with the values determined using ELISA. This fundamental study can help the researcher to choose the relevant coupling strategy for achieving desired sensor characteristics in clinical analysis of cancer biomarkers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-99351-8.

Keywords: Surface plasmon resonance, Electrochemical impedance, Biosensor, Biomarker, Cancer detection

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Cancer, Biomarkers, Chemistry, Materials science

Introduction

Recent tremendous technology development has changed the life style of common people which also endows sophisticated development in healthcare and biomedical area. In the biomedical area, the technological advancement shapes and nurtures cancer research in terms of early diagnosis and effective therapy. Diagnosing cancer at early stage helps in effective treatment with minimum economic burden, which affords the best survival rate of patient1. Cancer biomarker detection looks for protein, nucleic acid, gene, metabolites, cells that are associated to cancer and plays a significant role in early cancer diagnosis. Detection and quantification of cancer biomarker alerts the presence of cancer and its extent in the human body2. Biosensing strategy that detects and quantifies protein based cancer biomarkers with high accuracy, sensitivity and selectivity relies mainly antigen antibody binding. A wide variety of detection strategies like electrochemical, photoelectrochemical, electrochemiluminescent, chemiluminescence, radioimmuno, enzyme-linked immunosorption asssays, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy have been developed for the quantification of cancer biomarkers3. Among these techniques, SPR, an optical label-free detection technique for sensing biomolecular interactions4, has gathered considerable attention since 1983 when devising for gas and biosensing applications5. Since then it is widely used in the biomedical field for the detection of bacteria, virus and cancer biomarkers. SPR senses minute refractive index changes caused by the biomolecular interactions such as antigen-antibody binding on the gold coated glass surface which also enables the determination of specificity, affinity and rates of association and dissociation of interacting biomolecules4. There have been numerous efforts endeavored for the development of SPR sensing in clinical analysis6. SPR sensing has been used for the detection of protein associated with breast (Mucin 1) and ovarian cancer (CA125 antigen)7,8 and also widely used for common diseases like TB9 and dengue10. It has been reported that, this optical technique is widely being used in the detection of cancer biomarkers like AFP, CEA and PSA11,12. SPR based biosensor is also used to detect the over-expression of ErbB2 in breast cancer cell lines (SK-BR-3, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-436) using gold nanoparticles based probe13. To improve the sensitivity aptamer based signal amplification strategy had been employed for fiber optic SPR based sensing14. This simple optical principle can take advantage of making miniaturized device for making portable point-of-care testing facilities15. Integrating electrochemical monitoring with SPR based biosensing system improves the reliability of the sensing device and paves way for cost-effective diagnosis. In one of our previous studies liver cancer biomarker AFP was determined by electrochemical method in human blood serum and the immobilization efficiency of sensing platform was elaborated by SPR measurements16.

In the any biosensing system, immobilized antibody needs proper orientation and conformation for effective binding of particular antigen during sensing application. The coupling strategy followed for the immobilization of antibody on sensor surface plays a significant role in orienting and conformation of antibody to retain its activity which consequently determines the performance of a biosensor17. Recently, Tvorynska et al. investigated laccase biosensor with three coupling strategy for enzyme immobilization in sensing platform. It was observed that the immobilization of laccase covalently on the sensing surface via glutaraldehyde coupling afforded best sensor performance including low detection limit and long term stability to biosensor18. Recently, Meng et al. discussed about density and orientation of the bio-receptor for nucleic acid based biosensor which directly depends on the immobilization strategy adopted for the sensor construction19. Here, electrochemical SPR biosensor was constructed via three different coupling strategies to immobilize AFP antibody (AFPAb) on the sensor surface to evaluate the best performance of the biosensor for AFP detection. Gold coated sensor surface was modified by self-assembled monolayer of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid to get –COOH terminated sensor disc. AFP antibody was immobilized on the –COOH terminated sensor surface using three different coupling strategies as follows (i) 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide / N-hydroxy succinamide (EDC/NHS), (ii) ethylene diamine/ glutaraldehyde (EDA/GA) and (iii) polyaniline/glutaraldehyde (PANI/GA) chemistries. Present work elucidates the coupling chemistry based sensing performance of the ESPR based AFP biosensor. Analytical characteristics like linear range and sensitivity were investigated for sensors constructed using different coupling chemistry. To emphasize the feasibility of using proposed sensor in clinical application, system exhibiting best response was used to estimate the concentration of AFP in real blood samples and the values were compared with conventional ELISA approach. Feasibility of using electrochemical detection along with SPR based sensing is also demonstrated herein using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Immobilization and interaction steps were carried out and monitored by electrochemical SPR instrument. Then, best response system was used to detect the AFP in the human serum samples. Further the results were compared with conventional ELISA analysis.

Experimental

Materials

Gold sensor disk was purchased from SPR Instruments, The Netherlands. 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid, ethylene diamine, glutaraldehyde, 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethyl aminopropyl] carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS), ethanol amine, aniline, ammonium persulfate, bovine serum albumin, di-Sodium hydrogen phosphate, Sodium dihydrogen phosphate were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Merck) and used as received. Monoclonal AFP antibody (AFPAb) was purchased from Bioss USA and AFP antigen was purchased from Bio-Rad USA. Phosphate buffer solution (PBS), pH 7.4 was prepared by mixing the stock solutions of dibasic and monobasic sodium phosphate and used as the electrolyte during electrochemical characterizations. Deionized water was obtained using a Millipore Ultrapure water purification system.

ESPR measurement

SPR analyser ‘Autolab Twingle’ (SPR instruments, The Netherlands) having two channels with an automatic flow injection system, was used for SPR measurements. One channel was used to analyze samples while other one was used as a reference. The instrument was equipped with a glass hemi cylinder prism (BK 7, n = 1.518) as a Kretschmann attenuated total reflection coupler. A Ge–As diode laser was used to produce monochromatic light (wavelength 670 nm) as the light source and the dynamic range of SPR is 4000 m°. Instrument was integrated with electrochemical workstation (Autolab, The Netherlands) with BNC connector to record SPR signal in GPES software. A conventional three electrode set up was fabricated in the SPR instrument for in situ deposition of polyaniline (PANI) on the Au coated sensor disk using cyclic voltammetry. Au sensor disk, Pt wire and Ag/AgCl electrode was used as working electrode, counter electrode and reference electrode respectively. The electrochemical impedance measurements were performed in PBS (pH 7.4) with the frequencies ranging from 1 MHz to 0.5 Hz at a constant potential of 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A constant temperature of 25 °C was maintained in the system using a Julabo water bath. In situ PANI deposition and its EIS was monitored and recorded by SPR instrument (Fig S1).

Construction of biosensor for AFP detection

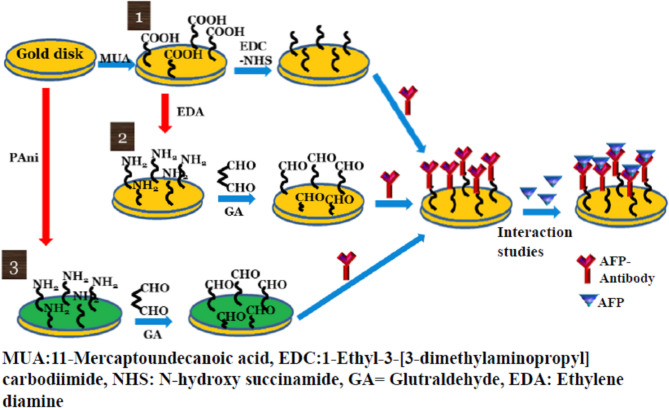

Initially, carboxylic acid terminated sensor disk was prepared by treating sensor disk with 1 mM MUA in isopropyl alcohol at room temperature. Modified sensor disk was washed with IPA, distilled water and dried with N2. Following this treatment, different immobilization strategies (Fig. 1) and interaction/detection studies were carried out in SPR analyser.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of various immobilization strategies employed for the immobilization of AFPAb: (1) EDC/NHS, (2) EDA/GA and (3) PANI/GA chemistries.

Immobilization of AFPAb using three different strategies

AFPAb was immobilized on the –COOH terminated sensor disk via EDC (400 mM) and NHS (100 mM) treatment followed by blocking of unreacted ester groups by 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride (EA). In the case of immobilization via EDA/GA Chemistry the –COOH terminated sensor disk was treated with 1 M ethylene diamine (EDA) to get amine functionalized sensor disk which was then treated with 1% glutaraldehyde (GA) to form aldehyde functionalized sensor disk. The AFPAb is then covalently coupled with the aldehyde modified sensor disk. The unreacted aldehyde groups were deactivated using 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride solution (pH 8.5) for 5 min. In the case of immobilization via PANI/GA Chemistry, electrochemically deposited PANI was covalently coupled with AFPAb via GA.

Interaction of AFPAb modified sensor disk with AFP

Interaction between AFP and AFPAb was simultaneously studied by SPR method and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). In SPR studies, prior to the interaction studies, the AFPAb modified surface was stabilized with PBS to obtain a stable baseline. 50 µl of AFP at six different dilutions (ng/ml) were added in to the flow cell. After antibody-antigen interaction, dissociation was carried out by PBS followed by regeneration of sensor disk by 0.1 M HCl and the stabilization of sensor disk using PBS. The specificity of sensor was carried out using BSA as interference. Electrochemical impedance studies were carried out during the immobilization of AFPAb and the interaction of various concentrations of AFP.

Blood serum sample analysis: sample preparation

Blood serum was isolated from blood samples following established standard operating procedure. Blood sample was drawn into a vial and allowed to coagulate for 30 min. The coagulated component was subsequently removed through centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant serum was transferred into vials and preserved at − 20 °C. For the purposes of electrochemical analysis and ELISA, undiluted serum was utilized.

Results and discussions

Immobilization of AFPAb on sensor disk using various strategies

Generally biomolecules like antibody or enzyme are immobilized on matrix via physical or covalent methods. Leaching of the biomolecules from the matrix impedes the utilization of former methods whereas later can overcome this issue20. Hence covalent modification was used for the Ab immobilization using EDC/NHS, EDA/GA and PANI/GA chemistries21–24. The effect of employing various strategies for antibody immobilization in SPR system was monitored by SPR shift and ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. In first strategy, EDC/NHS reacted with terminal carboxyl groups of MUA to form a reactive succinimide ester which then reacted to amino group of AFPAb25. However, in the case of EDA/GA and PANI/GA strategy, the -CHO group of GA reacted with amine groups of AFPAb via imine bonding. During every step of modification of sensor disk, an ATR-FTIR spectrum was recorded, to confirm the modifications on the sensor disk (Figs S2 and S3). As a representative, ATR-FTIR spectra of sequentially modified sensor disk with MUA, EDA, GA, AFPAb modifications are shown in Fig S2. When Au sensor disk was modified with MUA, absorption peak of carbonyl group at around 1660 cm− 1 was observed, revealing the presence of carboxylic acid on the sensor surface25. After sequential modification with EDA, peaks for C-N stretching of amine and C = O stretching of amide was observed at 1082 cm− 1 and 1720 cm− 1 respectively which authenticates the formation of amide and amine group on the sensor disk. Furthermore, after treating modified sensor disk with GA, a broad absorption peak at 1665 cm− 1 was observed which could be attributed to combined effects of carbonyl group of GA and oxime group which formed during the reaction between –NH2 of EDA and –CHO of GA. Finally, after treating sensor disk with AFPAb, the emergence of two bands at 1657 and 1556 cm− 1, which are characteristic of amide I and amide II bonds was observed, implying the conjugation of AFPAb on the sensor disk26. SPR measurement was carried out before and after immobilization of antibody on the sensor disk. The overall SPR angle shift for EDA/GA strategy (Fig. 2a) was found to be significantly high (650 m°) as compared to SPR shift for EDC/NHS (442 m°) and PANI/GA (119 m°) strategy (Fig. 2b and c respectively).

Fig. 2.

(a) SPR sensogram recorded during immobilization of AFPAb using EDA/GA chemistry. (1) EDA coupling, (2) GA crosslinking, (3) Immobilization of AFPAb, (4) EA blocking and (5) Regeneration of sensor disk. (b) SPR sensogram recorded during immobilization of AFPAb using EDC/NHS chemistry. (1) EDC/NHS interaction, (2) Immobilization of AFPAb, (3) EA blocking and (4) Regeneration of sensor disk. (c) SPR sensogram recorded during immobilization of AFPAb on PANI modified sensor disk. (1) GA crosslinking, (2) Immobilization of AFPAb, (3) EA blocking and (4) Regeneration of sensor disk.

Stability of the antibody on the sensor disc is an important parameter to ensure reproducibility of the sensor. Hence, before the antigen interaction studies, the antibody immobilized sensor films were stabilized with buffer solution for 15 runs. In the case of sensor disc modified using EDC/NHS and EDA/GA chemistries, a stable SPR signal is obtained even after several rounds of buffer wash (Fig S4), indicating that the antibody binding on the sensor disc is highly stable. From these values EDA/GA strategy was found to give highest antibody immobilization density as compared to other strategies. Hence, reproducibility, real sample analysis and electrochemical studies were performed in EDA/GA system.

Detection of AFP on AFPAb immobilized sensor disk using SPR based biosensor

The response of SPR biosensor towards AFP in real time using label free approach was studied. The association of antibody-antigen (Ab-Ag) is the first phase in a biomolecular interaction in the SPR based biosensor. Binding occurs when Ag and Ab collide due to diffusion, and when the collision has the correct orientation and enough energy. During the association of AFP with the AFPAb immobilized on sensor disk an increase in the SPR signal was observed and the difference in SPR angle between before and after interaction is denoted as Δ SPR which gives an estimate about the sensitivity of the biosensors towards AFP27,28. Since the AFP is continuously added and removed from the channel by sample flow, the situation is steady state after the binding of AFP-AFPAb occurs. After steady state, the dissociation of AFP from the sensor disk was achieved by continuous flow of PBS buffer. When the AFP in the flow over the surface of the sensor disc is replaced by the PBS, the free concentration of the AFP suddenly drops to zero and the complex will start to dissociate. In the dissociation step, a considerable decrease in SPR signal was observed. After the dissociation phase, the surface of biosensor was regenerated for studying interaction with new concentration of AFP. One of the crucial steps to consider is the regeneration phase, or more precisely, the regeneration solution, as it highly affects the sensitivity of the immunosensor. To regenerate the sensor disc the bound AFP must be removed using 0.1 M HCl solution, without causing irreversible damage to the immobilized AFPAb. This dilute acidic solution partially unfolds the proteins and brings them apart at this condition. Furthermore, at this condition proteins in AFP get positively charged resulting in the repulsion in binding sites which makes them further separated.

The interaction of different concentrations of AFP with sensor surface was carried out for all the three AFPAb modified biosensors. The sensor modified by EDA/GA chemistry gave the highest response on interaction with the same concentration of AFP, indicating an efficient immobilization of AFPAb on the sensor surface (Fig. 3a). Among the three coupling strategies studied, the EDC/NHS and EDA/GA strategies provided high immobilization efficiency whereas immobilization of AFPAb on PANI surface was significantly less. Antigen response to all the strategies is provided in the Fig. 3. As seen in the Fig. 3c, antigen response to PANI- AFPAb film was significantly less as compared to other two strategies. The nature of interaction curve in the case of PANI/GA strategy is a straight line with positive slope (Fig. S5), and it does not show characteristics of a typical antigen-antibody binding curve. This could be because PANI has high absorbance around 670 nm, which is the wavelength of the laser light used for SPR measurements. Though the PANI film was stabilized with PBS before the interaction studies, the change in optical characteristics (absorbance/ refractive index) of PANI with addition of aliquots of AFP antigen seem to masks the subtle changes arising from the antigen-antibody interaction. PANI is known to change its color/absorbance with change in conditions like the pH or degree of doping. A comparison of the SPR measurements recorded during buffer stabilization step for the three types of sensor films clearly indicate that the PANI/GA sensor film exhibits significant shift in the SPR angle with subsequent buffer wash steps (Fig S4a, b, c). Since the typical binding curves were not observed in the case of PANI/GA strategy, the EDC/NHS and EDA/GA strategies were selected for the further detailed binding studies.

Fig. 3.

The AFP interaction sensogram for (a) EDA/GA chemistry, (b) EDC/NHS chemistry and (c) PANI chemistries for AFP concentration of 10 ng/ml.

A response curve of angle shift (∆ SPR) vs. AFP concentration was plotted based on the interaction studies and the best response for AFP sensing was obtained with the biosensor, constructed using EDA/GA chemistry. SPR response increased linearly with the concertation of AFP (Fig. 4a). Sensor displayed excellent sensitivity (28 m°/ (ng/mL) with linear range of 0.5-3 ng/mL (Fig. 4b) and low limit of detection of 5 pg/mL.

Fig. 4.

(a) The sensogram for interaction of various concentrations of AFP with AFPAb bounded sensor prepared by EDA/GA Chemistry. (b) Plot for SPR angle shift vs. AFP concentration; Inset: Linear regression analysis of the response at low AFP concentration.

In the case of EDC/NHS coupling (Fig. 5), sensor displayed wide linear range (5–70 ng/mL) and one order less sensitive (2.12 m°/(ng/mL)) than EDA/GA strategy.

Fig. 5.

(a) The sensogram for interaction of various concentrations of AFP with AFPAb bounded sensor prepared by EDC/NHS chemistry. (b) Plot for SPR angle shift vs. AFP concentration; Inset: Linear regression analysis of the response at low AFP concentration.

Excellent sensitivity of the EDA/GA based sensor can be attributed to the proper orientation of AFPAb on the sensor disk which facilitated the binding of AFP on sensor surface. In this chemistry, amine group of AFPAb binds to the carbonyl group present on the surface of gold disk, while in EDC/NHS chemistry binding of AFPAb takes place via its amine group with the reactive ester group present on gold disk. This difference in binding groups seems to play a major role on the performance of biosensor. The density of AFPAb immobilization on the sensor disc is comparatively higher and properly oriented when EDA/GA chemistry was followed for immobilization. This could avoid the leaching off of AFPAb from the sensor surface while maintaining their active conformational changes for binding. However, when EDC/NHS chemistry was followed for immobilization, the immobilization density was slightly less. This could eventually stimulate conformational changes in the AFPAb indicating lesser sensitivity towards AFP binding. The values of sensitivity, linear range and detection limit for the sensor disk prepared by different chemistries are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative performance of biosensors designed with different strategies for AFP sensing.

| Strategy | Sensitivity [m°/(ng/mL)] | Linear range | Limit of detection [pg/mL] | Ka [(Ms)−1] | Kd [s−1] | KA [M−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDA/GA | 28 | 0.5-3 | 5.4 | 2.3 × 106 | 8 × 10−3 | 2.9 × 108 |

| EDC/NHS | 2.12 | 5–70 | 39 | 1 × 106 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 6.6 × 107 |

Researchers have used signal amplification probes like Au nanoparticles in SPR biosensor for cancer biomarker detection. However, in the present work, label-free biosensor was constructed and the LOD obtained for proposed biosensor is better (5.4 pg/ml) than signal amplification strategy. Li et al. used Au nanoparticles for signal amplification for the detection of CEA by SPR biosensor with LOD of 1000 pg/mL29. Wang et al. followed dual amplification strategy using Au NPs and quantum dots for the sensitive detection of AFP, carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin fragment 21 − 1 which afforded LOD of 100 pg/mL11. Su et al. investigated different coupling strategy by using different protein for immobilizating CEA antibody to detect CEA in blood serum where sensor afforded LOD of 6200 pg/mL30. LOD values of the present work in better than most of the label-free and signal amplification reports. Comparison table with analytical performance of different SPR based sensor is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison table of analytical performances of SPR biosensor for cancer biomarker detection.

| S. No. | Amplification probe | Biomarker | LOD | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Au NPs | CEA | 1000 pg/mL | 29 |

| 2 | Au NPs and quantum dots | CEA | 100 pg/mL | 11 |

| 3 | – | CEA | 6200 pg/mL | 30 |

| 4 | Anti-CEA monoclonal antibody | CEA | 3000 pg/mL | 31 |

| 5 | Bio-functionalized Au NPs | CEA | 100 pg/mL | 32 |

| 6 | Au NPs | ErbB2 | 180 pg/mL | 13 |

| 7 | HRP conjugated Antibody | AFP | 1500 pg/mL | 33 |

| 8 | Fe3O4@Au composite | AFP | 650 pg/mL | 34 |

| 9 | Fe3O4@TiO2 | PD-L1 + exosomes | 31.9 particles/mL | 35 |

| 10 | AuNPs with Multicomponent Nucleic Acid enzymes | miRNA-4739 | 7 pM | 36 |

| 11 | ployA-DNA/ miRNA/AuNPs | miRNA21, miRNA124 and miRNA143 | 0.0063 pM, 0.0053 pM and 0.0046 pM | 37 |

| 12 | Label-free | AFP | 5.4 pg/mL | Present work |

Kinetic study

The kinetic data calculations were performed using Kinetic Evaluation software (version 5.4, KE instruments). AFP binding curves were fitted using simple 1:1 monophasic interaction equations. By fitting the binding curves with 1:1 binding model, the association constant (Ka) and dissociation constant (Kd) were calculated. The ratio of association and dissociation constant was used to calculate affinity constant (KA). The KA for binding of AFP to AFPAb bound sensor disk prepared using EDA/GA chemistry was higher by an order of magnitude than EDC/NHS modified sensor disk (Table 1). The better affinity of anti AFP present on the surface of EDA/GA modified sensor disk indicates that the AFP binding sites are properly oriented on the surface using this immobilization chemistry. The KA value obtained for EDA/GA chemistry was similar to the value reported Liang et al.35.

Cross-reactivity

The cross-reactivity study of the AFPAb bound sensor disks was carried out using BSA was shown in Fig. 6 (EDA/GA chemistry) and Fig S6 (EDC/NHS and PANI/GA). A slight increase (16%) in SPR signal is observed upon addition of BSA aliquot at a concentration 50 times higher than that of AFP. Thus the sensor displayed a very good specificity for binding of AFP.

Fig. 6.

Specificity study for AFPAb modified SPR sensor disk (EDA/GA Chemistry) for AFP sensing. Study was carried out by injection of various concentrations of BSA (a) 20 ng/mL (b) 100 ng/mL and (c) 5 ng/mL AFP.

Reproducibility and real sample analysis

In order to assess reproducibility, four distinct sensors were constructed, and serum samples were analyzed to determine the concentration of AFP. Subsequently, the same serum samples underwent testing using the conventional ELISA method for AFP concentration. The detection of AFP in serum samples was performed using four sensor disks modified through EDA/GA chemistry, and the results were compared with those obtained from enzyme-linked immunoassays. As indicated in Table 3, no significant differences were observed between the two methodologies. Therefore, the modification strategy developed is both reproducible and reliable, demonstrating its potential utility for the determination of AFP in biological samples within clinical settings.

Table 3.

Comparison of SPR and ELISA technique for detection of AFP in human serum.

| ELISA (ng/ml) | ESPR (ng/ml) | % error | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum 1 | 10.74 | 9.8 | 8.7 |

| Serum 2 | 30 | 31.7 | 5.7 |

| Serum 3 | 30 | 29.7 | 1 |

| Serum 4 | 24.5 | 23.1 | 5.7 |

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic investigation

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful tool for detection of biomolecular interaction. Moreover, it is simple, highly sensitive and serves as an elegant way to interface biorecognition process and signal transduction. It is based on measuring the electrical current response to an AC potential applied between electrodes and is extremely sensitive for detection of biomolecular adsorption taking place on the electrode surface38. ESPR is a powerful tool to simultaneously study the SPR and electrochemical signals in real time. Inorder to study the binding of the antigen to the immobilized antibody by EIS under the same conditions as that of SPR technique, the EIS measurements were performed without using any redox probe. Hence, the EIS signal is associated with the non-Faradaic currents at the electrode-electrolyte interface. These currents are caused due to movement of electrolyte ions, reorientation of solvent dipoles, adsorption/ desorption of biomolecules, etc. The interface between the metal electrode and electrolyte with an adsorbed biomolecular layer can be considered as three physical regions: bulk solution, double layer and molecular layer39. The net impedance signal arises due to contribution from (a) the uncompensated solution resistance (Rs), (b) the electric double layer at the electrode/electrolyte interface and (c) the resistance and capacitance of the biomolecular layer.

In the present study, the change in impedance due to biomolecular binding interaction was studied under potentiostatic conditions. The impedance spectra were recorded over a frequency range of 0.5 Hz to 1 MHz after each stage of sensor disc modification. The Nyquist plot for bare gold sensor disc, MUA modified disc, AFPAb immobilized disc and after AFP binding is depicted in Fig. 7. Since the change in double layer capacitance due to biomolecular adsorption and binding are expected to be prominent in low frequency region, the values of real and imaginary components of the impedance at a frequency of 1.1 kHz were plotted for different stages of sensor disc modification (Fig. 8). The total impedance of the sensor as a whole was considered and no equivalent circuit has been used to model the system for simplicity. The resistance and capacitance values are correlated to the real and imaginary part of the impedance respectively.

Fig. 7.

Nyquist plots of AFP interaction studies done AFPAb modified gold sensor disk using EDC/NHS chemistry.

Fig. 8.

Real and imaginary components of impedance (recorded at frequency of 1.1 kHz) at different stages of modification of sensor disk such as (a) bare gold disk, on (b) MUA SAM immobilization, (c) AFPAb immobilization and (d–i) binding with AFP of different concentrations.

As it can be seen from the Fig. 8, modification of the gold disc with SAM of MUA lead to a decrease in the capacitance by 2.5 times. It is well reported that long-chain alkane thiols like MUA form highly ordered defect-free monolayers, which act as a barrier for electron transfer and movement of ions towards the electrode. Souto et al. have reported an 8-fold lowering of the capacitance of gold electrode on deposition of MUA SAM. As far as the resistance is concerned, there is a small increase in the resistance of the electrode on deposition of SAM, which indicates that the SAM could be porous and not densely packed. On immobilization of the AFPAb, there is a large decrease in capacitance and an increase in resistance, thus confirming the binding of the antibody to the SAM40. The adsorption of biomolecules is known to influence the capacitance of the double layer to varying degrees39. Both decreases and increases in capacitance have been reported in literature. The change in capacitance is attributed to the change in thickness, conformational changes, and interpenetration of biomolecules into the dielectric layer. The decrease in capacitance after immobilization of AFPAb can be attributed to the increase in thickness of the double layer due to antibody binding. On binding of the AFP to AFPAb, a small increase in the capacitance is observed. With increase in the AFP concentration, the capacitance further increases. This could be due to interpenetration of AFP molecules into the SAM- AFPAb dielectric layer resulting in change in the effective dielectric constant of the layer. A large drop in resistance was observed on binding with AFP however, the variation in resistance with increasing concentration of AFP is marginal. The increase in surface conductivity on binding of AFP is similar to that reported in literature of hybridization of DNA39. Similar trend of impedance variation was observed throughout the range of low frequencies. Thus the impedance studies helped in tracing the binding of AFP to AFPAb immobilized surface along with the SPR signal.

Conclusion

ESPR is a versatile technique enabling simultaneous investigation of biomolecular interaction by electrochemical and SPR techniques. The present work focused on studying the real time binding of antigen to the antibody immobilized sensor surface. Three different antibody coupling chemistries, i.e., EDC/NHS, EDA/GA and PANI/GA chemistry, were compared to arrive at the best sensor design. The highest sensitivity for AFP detection was obtained with EDA/GA chemistry, which was followed by EDC/NHS chemistry. The KA value for AFP obtained with biosensor based on EDA/GA chemistry was higher by an order of magnitude than biosensor fabricated using EDC/NHS chemistry. Also, the biosensor did not give any significant response due to non- specific binding. Since the binding of antigen to antibody does not give any direct amperometric response, ESI was used to evaluate the sensor. Alternately, the antigen can be tagged with a redox probe or an enzyme like HRP (coupled with a mediator) to obtain amperometic response, which can be measured by DPV or SWV. Thus, the immobilization strategy employed during the designing of immunosensor plays a very important role in modulating its sensitivity. Hence, sensor evaluation strategies demonstrated herein can be exploited to achieve a biosensor with optimum performance.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

BT: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. ACA and PK: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. SNS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Formal analysis, review & editing.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this manuscript and its Supplementary Information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Crosby, D. et al. Early detection of cancer. Science375, eaay9040. 10.1126/science.aay9040 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar, S. & Singh, R. Recent optical sensing technologies for the detection of various biomolecules: review. Opt. Laser Technol.134, 106620. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2020.106620 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun, X. et al. Material-enhanced biosensors for cancer biomarkers detection. Microchem J.194, 109298. 10.1016/j.microc.2023.109298 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquardini, L. et al. Immuno-SPR biosensor for the detection of Brucella abortus. Sci. Rep.13, 22832. 10.1038/s41598-023-50344-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liedberg, B., Nylander, C. & Lunström, I. Surface plasmon resonance for gas detection and biosensing. Sens. Actuators. 4, 299–304. 10.1016/0250-6874(83)85036-7 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu, Q., Wu, W., Chen, F. & Ren, P. Highly sensitive and selective surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1 protein. Analyst147, 2809–2818. 10.1039/D2AN00426G (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, R. et al. Fiber SPR biosensor sensitized by MOFs for MUC1 protein detection. Talanta258, 124467. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.110783 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahbazlou, S. V., Vandghanooni, S., Dabirmanesh, B., Eskandani, M. & Hasannia, S. Biotinylated aptamer-based SPR biosensor for detection of CA125 antigen. Microchem J.194, 109276. 10.1016/j.microc.2023.109276 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daher, M. G. et al. Optical biosensor based on surface plasmonresonance nanostructure for the detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria with ultra-high efficiency and detection accuracy. Plasmonics18, 2195–2204. 10.1007/s11468-023-01938-2 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gahlaut, S. K., Pathak, A., Gupta, B. D. & Singh, J. P. Portable fiber-optic SPR platform for the detection of NS1-antigen for dengue diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron.196, 113720. 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113720 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, H., Wang, X., Wang, J., Fu, W. & Yao, C. A SPR biosensor based on signal amplification using antibody-QD conjugates for quantitative determination of multiple tumor markers. Sci. Rep.6, 33140. 10.1038/srep33140 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ertürk, G., Özen, H., Tümer, M. A., Mattiasson, B. & Denizli, A. Microcontact imprinting based surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor for real-time and ultrasensitive detection of prostate specific antigen (PSA) from clinical samples. Sens. Actuators B: Chem.224, 823–832. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.10.093 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eletxigerra, U. et al. Surface plasmon resonance immunosensor for ErbB2 breast cancer biomarker determination in human serum and Raw cancer cell lysates. Anal. Chim. Acta. 905, 156–162. 10.1016/j.aca.2015.12.020 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillen, A. et al. Integrated signal amplification on a fiber optic SPR sensor using duplexed aptamers. ACS Sens.8, 811–821. 10.1021/acssensors.2c02388 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, Q. et al. Smartphone surface plasmon resonance imaging for the simultaneous and sensitive detection of acute kidney injury biomarkers with noninvasive Urinalysis. Lab. Chip. 22, 4941–4949. 10.1039/D2LC00417H (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ChellachamyAnbalagan, A. & Sawant, S. N. Carboxylic acid–tethered polyaniline as a generic immobilization matrix for electrochemical bioassays. Microchim Acta. 188, 403. 10.1007/s00604-021-05059-7 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vashist, S. K., Dixit, C. K., MacCraith, B. D. & O’Kennedy, R. Effect of antibody immobilization strategies on the analytical performance of a surface plasmon resonance-based immunoassay. Analyst136, 4431–4436. 10.1039/c1an15325k (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tvorynska, S., Barek, J. & Josypcuk, B. Influence of different covalent immobilization protocols on electroanalytical performance of laccase-based biosensors. Bioelectrochemistry148, 108223. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2022.108223 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng, X., O’Hare, D. & Ladame, S. Surface immobilization strategies for the development of electrochemical nucleic acid sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron.237, 115440. 10.1016/j.bios.2023.115440 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong, L. S., Khan, F. & Micklefield, J. Selective covalent protein immobilization: strategies and applications. Chem. Rev.109, 4025–4053. 10.1021/cr8004668 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anbalagan, A. C. & Sawant, S. N. Redox-labelled detection probe enabled immunoassay for simultaneous detection of multiple cancer biomarkers. Microchim Acta. 190, 86. 10.1007/s00604-023-05663-9 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korram, J., Anbalagan, A. C., Banerjee, A. & Sawant, S. N. Bio-conjugated carbon Dots for the bimodal detection of prostate cancer biomarkers via sandwich fluorescence and electrochemical immunoassays. J. Mater. Chem. B. 12, 742–751. 10.1039/d3tb02090h (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anbalagan, A. C., Korram, J., Doble, M. & Sawant, S. N. Bio-functionalized carbon Dots for signaling immuno-reaction of carcinoembryonic antigen in an electrochemical biosensor for cancer biomarker detection. Discover Nano. 19, 37. 10.1186/s11671-024-03980-3 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anbalagan, A. C. et al. Carbon Dots functionalized polyaniline as efficient sensing platform for cancer biomarker detection. Diam. Relat. Mater.147, 111276. 10.1016/j.diamond.2024.111276 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandiyaraj, K., Elkaffas, R. A., Mohideen, M. I. H. & Eissa, S. Graphene oxide/Cu–MOF-based electrochemical immunosensor for the simultaneous detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila antigens in water. Sci. Rep.14, 17172. 10.1038/s41598-024-68231-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagireddi, S., Katiyar, V. & &Uppaluri, R. Pd(II) adsorption characteristics of glutaraldehyde cross-linked Chitosan copolymer resin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.94, 72–84. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.088 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro, J. A., Sales, M. G. F. & Pereira, C. M. Electrochemistry combined-surface plasmon resonance biosensors: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem.157, 116766. 10.1016/j.trac.2022.116766 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, Q. et al. Research advances on surface plasmon resonance biosensors. Nanoscale14, 564–591. 10.1039/D1NR05400G (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, R. et al. Sensitive detection of carcinoembryonic antigen using surface plasmon resonance biosensor with gold nanoparticles signal amplification. Talanta140, 143–149. 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.03.041 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su, F. et al. Detection of carcinoembryonic antigens using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Sensors8, 4282–4295. 10.3390/s8074282 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altintas, Z., Uludag, Y., Gurbuz, Y. & Tothill, I. E. Surface plasmon resonance based immunosensor for the detection of the cancer biomarker carcinoembryonic antigen. Talanta86, 377–383. 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.09.031 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Špringer, T. & Homola, J. Biofunctionalized gold nanoparticles for SPR-biosensor-based detection of CEA in blood plasma. Anal. Bioanal Chem.404, 2869–2875. 10.1007/s00216-012-6308-9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ucci, S., Cicatiello, P., Spaziani, S. & Cusano, A. Development of custom surface plasmonresonance Au biosensor for liver cancer biomarker detection. Results Opt.5, 100193. 10.1016/j.rio.2021.100193 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang, R. P., Yao, G. H., Fan, L. X. & Qiu, J. D. Magnetic Fe3O4@Au composite-enhanced surface plasmon resonance for ultrasensitive detection of magnetic nanoparticle-enriched α-fetoprotein. Anal. Chim. Acta. 737, 22–28. 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.043 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, H. et al. Construction of a sensitive SWCNTs integrated SPR biosensor for detecting PD-L1 + exosomes based on Fe3O4@TiO2 specific enrichment and signal amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron.262, 116527. 10.1016/j.bios.2024.116527 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larraga-Urdaz, A. L., Moreira-Álvarez, B., Encinar, J. R., Costa-Fernández, J. M. & Fernández-Sánchez, M. L. A plasmonic MNAzyme signal amplification strategy for quantification of miRNA-4739 breast cancer biomarker. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1285, 341999. 10.1016/j.aca.2023.341999 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, Y. et al. SPRi/SERS dual-mode biosensor based on ployA-DNA/ MiRNA/AuNPs-enhanced probe sandwich structure for the detection of multiple MiRNA biomarkers. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.308, 123664. 10.1016/j.saa.2023.123664 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polonschii, C. et al. Complementarity of EIS and SPR to reveal specific and nonspecific binding when interrogating a model bioaffinity sensor; perspective offered by plasmonic based EIS. Anal. Chem.86, 8553–8562. 10.1021/ac501348n (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ihalainen, P. et al. An impedimetric study of DNA hybridization on paper-supported inkjet-printed gold electrodes. Nanotechnology25 (094009). 10.1088/0957-4484/25/9/094009 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Souto, D. E. P. et al. Development of a label-free immunosensor based on surface plasmon resonance technique for the detection of anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies in canine serum. Biosens. Bioelectron.46, 22–29. 10.1016/j.bios.2013.01.067 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this manuscript and its Supplementary Information files.