Abstract

Cyclic AMP is a versatile signaling molecule utilized throughout the eukaryotic domain. A frequent use is to activate protein kinase A (PKA), a serine/threonine kinase that drives many physiological responses. Spatiotemporal organization of PKA occurs though association with A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses trace the evolution of PKA regulatory (R) and catalytic (C) subunits and AKAPs from the emergence of metazoans. AKAPs that preferentially associate with the type I (RI) or type II (RII) regulatory subunits diverged at the advent of the vertebrate clade. Type I PKA anchoring proteins including smAKAP contain an FA motif at positions 1 and 2 of their amphipathic binding helices. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching measurements indicate smAKAP preferentially associates with RI (T 1/2. 4.37 ± 1.2 s; n = 3) as compared to RII (T 1/2. 2.19 ± 0.5 s; n = 3). Parallel studies measured AKAP79 recovery half times of 8.74 ± 0.3 s (n = 3) for RI and 14.42 ± 2.1 s (n = 3) and for RII, respectively. Introduction of FA and AF motifs at either ends of the AKAP79 helix biases the full-length anchoring protein toward type I PKA signaling to reduce corticosterone release from adrenal cells by 61.5 ± 0.8% (n = 3). Conversely, substitution of the YA motif at the beginning of the smAKAP helix for a pair of leucine's abrogates RI anchoring. Thus, AKAPs have evolved from the base of the metazoan clade into specialized type I and type II PKA anchoring proteins.

Keywords: signal transduction, protein kinase A, AKAP, evolution, amphipathic helix

The nucleotide 3′,5′-cyclic AMP (cAMP) is a versatile molecule utilized throughout the archaebacteria, eubacteria, plant, and animal kingdoms (1, 2). In animals, cAMP is often utilized as a second messenger to relay information to effector proteins embedded in membranes or enzymes located deep inside the cell (3). Binding of cAMP to regulatory subunits of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) triggers the phosphorylation of substrates to potentiate hormone action (4), exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (Epac) regulate small GTPases (5), transcription factors such as the cAMP receptor protein drive certain gene reprogramming paradigms (6), and cAMP binding to ion channels directly modulates their conductance (7). Arguably the most common use of cAMP is to activate PKA (1). This family of serine/threonine protein kinases exist as tetrameric holoenzymes (8). A regulatory subunit dimer maintains two bound catalytic subunits (PKAc) in an autoinhibited state (9). Recruitment of cAMP to binding sites on regulatory subunits relieves autoinhibition of the kinase allowing the phosphorylation of target substrates (10). Three genes encode the PKAc α, β, and γ isoforms whereas four genes encode the type I regulatory (RI α and RI β) and type II regulatory (RII α and RII β) subunits (11). These gene products are assembled into type I or type II PKA holoenzymes that exhibit different sensitivities to cAMP and subcellular locations (12).

Spatiotemporal organization of cAMP signaling offers an efficient mechanism that directs PKA phosphorylation to precise locations within the cell. These signaling events occur within the confines of highly organized signaling nanodomains (13). Recently three independent areas of research have converged to inform a new appreciation of how precise local signaling can be (14). First, advanced optical mapping techniques defined local cAMP environments that are formed by buffered diffusion of the second messenger (15, 16). These “Receptor-associated independent cAMP nanodomains” not only sustain local cAMP synthesis but limit where localized signaling is operational. Second, G protein-coupled receptor signal transduction is now recognized to occur at subcellular compartments that are distinct from the plasma membrane (17). This generates discrete intracellular sites of cAMP synthesis to further propagate local signaling. Third, structural analyses of intact PKA–AKAP complexes reveal that anchored holoenzymes exist as a montage of flexible tripartite configurations (10). For example, type II PKA holoenzyme–AKAP18γ complexes are bestowed with a 200 to 400 Å range of motion. These refined parameters of cAMP action not only emphasize the value of three dimensional intracellular signaling but stress the important role that AKAPs play in determining where and when PKA acts inside the cell (14).

To date, in the order of 60 AKAP genes are encoded by the human genome, many of which comprise of differentially spliced and differentially localized anchoring protein families (12, 13, 18, 19). The physiological importance of AKAPs have been demonstrated in a range of cellular and pathological contexts (3, 20). Anchored signaling events have been implicated in the rapid modulation of ion channels, control of glucose homeostasis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis (21, 22, 23). Thus anchored PKA events determine the specificity of these second messenger signaling responses.

PKA anchoring proceeds through modular protein–protein interactions (24). An emblematic feature of AKAPs is a 14 to 18 amino acid segment that folds to form an amphipathic helix (25). This region binds with high affinity to a docking and dimerization domain formed by the first 45 to 50 residues of the type I or type II regulatory subunits of PKA. Biochemical, structural, and cell-based studies show that this high affinity protein–protein interaction is the principal mode of PKA anchoring (26). Moreover, peptide antagonists are effective reagents that are used to disrupt the PKA–AKAP interface. Ht 31, AKAP-is, and RIAD peptides have proven to be useful tools to establish the physiological role of type I and type II PKA anchoring in a range of cellular contexts (27, 28, 29). Structural elucidation of docking and dimerization domains reveals subtle but significant differences in the organization of the RI/AKAP and RII/AKAP binding interfaces (30, 31). The first 50 residues of each RI protomer form a tightly packed helical structure that is stabilized by interchain disulfide bonds. This conserved domain creates a binding groove that accepts an amphipathic helix on the AKAP with intermediate binding affinities (32). Conversely, the more malleable D/D domain of RII adopts a conventional four-helix bundle-like configuration that bonds AKAPs with low nanomolar binding affinities (30). These findings argue that cryptic side chain determinants reside within AKAP helices that favor the anchoring of type I or type II PKA.

In this report, we trace the evolution of PKA subunits and AKAPs from their origins at the emergence of metazoans. We also note a rapid expansion of this scaffolding protein class at the advent of the vertebrate clade. Biophysical, biochemical, and functional studies define conserved side chain determinants for type I PKA anchoring that reside at both ends of AKAP anchoring helices. Functional studies show that introduction of these RI anchoring determinants is sufficient to switch the isotype selectivity of a canonical RII-binding protein to accommodate an association of type I PKA holoenzymes.

Results

PKA subunit and AKAP co-evolution

Informatic analyses suggest that the evolutionary path of AKAPs occurred after the existence of PKA catalytic and regulatory subunits. While invertebrate animals, including the Tunicates and lancelets, encode a single PKAc subunit gene, the PRKACA and PRKACB genes rose from a gene duplication event in early vertebrates (Fig. 1; (33)). In contrast, the PRKACG gene is intronless, only appears in primates, and seems to be retrotransposon-derived (Fig. 1; (34)).

Figure 1.

AKAP and PKA evolutionary history. A cladogram displays the emergence of AKAPs and PKA subunits throughout Metazoan evolution. Clade names indicate the origin of a protein, as well as numbers in parentheses denoting the number of proteins to emerge in this clade. PKAc subunits (green dots), RI subunits (gold dots), RI subunits (silver dots), AKAPs (magentadots). Inset 1: smAKAP helix (magenta) docked to RIα D/D (tan). Inset 2: AKAP79 helix (magenta) docked to RIIα D/D (gray).

Evolution of the regulatory subunits (RIα and RIIα) has followed a more circuitous path. These genes arose from an early event where a primordial four helix-like bundle called the docking and dimerization (D/D) domain (Fig. 1). This region became fused to cyclic nucleotide-binding domains analogous to the bacterial catabolite transcriptional activator gene (35, 36). Structural studies show clear differences between the homodimerizing D/D domains of RIα and RIIα (Fig. 1, insets). In RIα, a stable helical cluster at the N terminus of each RIα protomer forms a proteinase-resistant dimer held together by intersubunit disulfide bonds ((9, 31) Fig. 1 inset 1). In contrast, the more flexible D/D domain of RII adopts a conventional four-helix bundle-like configuration that lacks flanking helices ((30, 36), Fig. 1, inset 2). Phylogenetic projections presented in Fig. 1 depict the PRKAR1 and PRKARII genes as appearing around the same time as the duplication of Cα and Cβ genes at the metazoan last common ancestor (Fig. 1).

Twenty-three AKAPs were arranged on a cladogram of metazoan classes according to each protein's last common ancestor (Fig. 1). Last common ancestors were calculated by detecting the nearest node on the metazoan tree which would explain a protein's distribution in extant species collected by protein BLAST searches (37). Three primordial AKAPs emerged at this point: OPA1, dAKAP2, and AKAP28 (Fig. 1). These are the only AKAPs present in the sponge class Porifera (Fig. S1). OPA1 anchors PKA to the outer mitochondrial membrane, AKAP28 is a stabilizing architectural element of motile cilia, whereas the biological role of dAKAP2 is more varied (38, 39, 40, 41, 42).

The appearance of dAKAP1 and Merlin was coincident with the advent of ParaHox genes, which dictate the development of more complex anatomy. Merlin connects PKA to the cytoskeleton whereas dAKAP1 resides at the outer mitochondrial membrane and regulates translation (43, 44). Hence, AKAP targeting of PKA is unique to animals (45). Tracing the appearance of AKAPs through the metazoan clade reveals an increase in anchoring proteins as the biological complexity of animal cells expanded.

The principal explosion in AKAP complexity occurs at the base of the vertebrate lineage (Fig. 1). Fourteen AKAPs originate here, including dual-helix AKAPs (SKIP and AKAP220). At this point, we see the emergence of type I R subunit selective AKAPs (GPR161 and smAKAP). This burst in AKAPs is consistent with their role in spatially targeting PKA holoenzymes upon development of nervous systems and the increased complexity of multicellular organisms (46, 47). These events are concomitant with the appearance of the RIβ and RIIβ isoforms (Fig. 1).

After the onset of vertebrates, fewer AKAPs emerged. The tetrapod linage saw the debut of AKAP4 which synchronizes sperm flagella action and AKAP79/150, a membrane proximal scaffolding protein that coordinates the phosphorylation of hippocampal AMPA receptors in long term potentiation (Fig. 1, red text). The amniote lineage expanded on the organization of sperm flagella with AKAP3, sharing a preference of anchoring type I PKA with AKAP4. Around this time, other specialized RI-anchoring proteins appeared including mitochondrial SKIP and the membrane-tethered smAKAP (Fig. 1, red text). The phylogenetic data in Figure 1 indicate that early AKAPs appeared after the formation of the alpha isoforms of their R subunit–binding partners and the advent of PKAcα and PKAcβ. A major expansion of the AKAP class occurred in vertebrates.

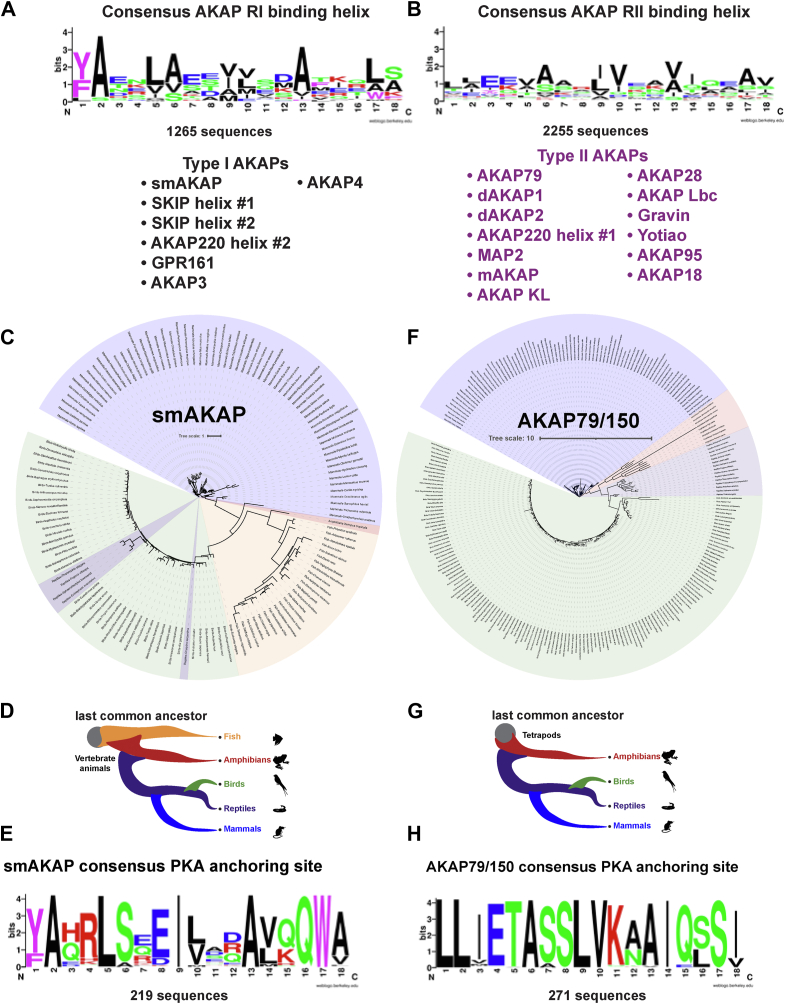

Deriving consensus RI and RII anchoring motifs

The defining feature of AKAPs is a 14 to 18 residue region that folds into an amphipathic helix (25, 27, 30). This structural motif snugly fits into a cleft on the D/D domains of R subunits (12). We reasoned that computational alignment of AKAP helices might uncover amino acid determinants for R subunit isotype selectivity. Orthologs of seven AKAPs which anchor type I PKA (1265 sequences, Figs. 2A and S2) and 13 AKAPs which prefer type II PKA (2255 sequences, Figs. 2B and S2) were aligned with the MUSCLE algorithm (48). Sequence conservation logos highlight regions of homology (49). Side chain conservation was more pronounced on the hydrophobic faces of each helix (residues 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, and 17). This surface directly interfaces with D/D domains (50). There is less conservation on polar face of the amphipathic helixes (51). Strikingly, type I AKAPs exhibit high conservation at the amino terminus of the binding helix. A phenyl group (F or Y) at position 1 is strongly favored and an almost invariant alanine occupies position 2 (Fig. 2A). This “FA motif” is ubiquitous among type I selective AKAPs across the metazoan clade (Fig. S2). Hydrophobic side chains are also favored at positions 17 and 18, although the stringency of conservation is less (Fig. 2A). In contrast, there was more degeneracy across the consensus RII binding motif, although the hydrophobic core of the amphipathic helix was conserved (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Type I and II AKAPs.A, consensus logos of 1265 type I AKAP helices, revealing a conserved FA motif (97.7% conservation with F/Y). The AKAPs used are listed below. B, consensus logos of 2255 type II AKAP helices. C, phylogenetic tree of smAKAP orthologs. D, cladogram showing the smAKAP distribution among vertebrates. E, consensus logo of 219 smAKAP ortholog helices. F, phylogenetic tree of AKAP79/150 orthologs. G, cladogram of AKAP79/150 distribution across tetrapods. H, consensus logo of 271 AKAP79/150 ortholog helices.

Phylogenetic analysis of smAKAP: a representative type I anchoring protein

Biochemical studies indicate that smAKAP is a prototypic type I PKA anchoring protein (52, 53, 54). A phylogenetic tree was generated from a BLAST search yielding 219 high quality orthologs of smAKAP (Fig. 2C). Sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm, and phylogenetic representation was generated using IQ-TREE on the CIPRES gateway with 2000 bootstraps (55, 56). Mammalian (blue), amphibian (red), fish (orange), and bird (green) smAKAP orthologs segregate into distinct lineages (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, reptiles (purple) are divided into two groups that reside within the bird cluster (Fig. 2C). These are the paired reptilian orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia (snakes and lizards) and the lone Testudines order (turtles and tortoises).

This information allowed us to derive a cladogram that reveals the smAKAP origin at the base of the vertebrate lineage (Fig. 2D). A consensus smAKAP helix motif from 219 sequences indicates the chemical properties of conserved side chains (Fig. 2E). Although early positions in the RI-binding site are invariant, it is pertinent to note that the nature of individual hydrophobic and hydrophilic side chains vary within the core of the helix (Fig. 2E).

Phylogenetic analysis of AKAP79: a representative type II anchoring protein

The AKAP79 family of anchoring proteins are emblematic type II PKA anchoring proteins (25, 57, 58). A phylogenetic tree was generated with 271 high quality AKAP79/150 orthologs (Fig. 2, F–H). Interestingly, AKAP79 is absent in fish (Fig. 2G). Mammals (blue) and birds (green) display the highest diversity due to the sporadic insertion of repeat sequences (Fig. 2F). A cladogram illustrates the origin of AKAP79/150 at the tetrapod lineage (Fig. 2G). The conservation logo for the AKAP79 helix reveals a higher degree of conservation with 11 out of 18 positions being invariant (Figs. 2H and S3). Data in Figure 2 indicates that RI and RII recognize different anchoring determinants.

Photobleaching measurements of R subunits

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) measures the diffusion and interactive properties of proteins in the membranes of living cells (59). We performed total internal reflected fluorescence (TIRF) photobleaching experiments to measure exchange of PKA subunits from prototypic RI and RII selective anchoring proteins (Fig. 3A). This approach provides a more sensitive and dynamic appraisal of R subunit AKAP interactions than standard biochemical methods. As a prelude to these studies, RI-iRFP and RII-iRFP were photobleached in the absence of AKAPs (Fig. 3B). These data show that free RI and RII diffuse at similar rates. The time to 50% fluorescence recovery for RIα is 1.54 ± 0.6 (n = 3 experiments of 50 cells, Fig. 3C) seconds. Similarly, the recovery half-time of RIIα is 2.66 ± 0.6 s (n = 3 experiments of 50 cells, Fig. 3C). Rate constant for RIα is 0.96 ± 0.04 s−1 and for RIIα is 0.95 ± 0.01 s−1 respectively (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

FRAP analysis of smAKAP and AKAP79.A, schematic of the TIRF-FRAP paradigm (left) and a representative recovery graph (right). Tighter AKAP-binding results in a slower recovery of the photobleached R subunits. B, representative FRAP recovery curves of free R subunits RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver), displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Mean ± SD recovery half-times included. C, recovery half times of free RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). D, recovery rate constants of free RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). Means ± SD (n = 3) Student's t test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005. E, time course of photobleaching of smAKAP-bound RIα (top) and RIIα (bottom) over 3 s. F, representative FRAP recovery curves of smAKAP-bound R subunits RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver) displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Mean ± SD recovery half-times included. G, time course of photobleaching of AKAP79-bound RIα (top) and RIIα (bottom) over 7 s. H, representative FRAP recovery curves of AKAP79-bound R subunits RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver) displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Mean ± SD recovery half-time values included. I, recovery half-time of smAKAP (left) and AKAP79 (right) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). J, recovery rate constants of smAKAP (left) and AKAP79 (right) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). Means ± SD (n = 3). Student's t test: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005.

smAKAP prefers RI

Next, we compared the diffusion properties in the presence of smAKAP. Representative photobleaching images at 1 s intervals show a faster recovery of RII bleach spots than RI bleach spots (Fig. 3E). A recovery curve consisting of combined FRAP time courses (50 cells) reveals the slower recovery of RI in the presence of smAKAP (Fig. 3F). Quantifying three individual experiments measures a mean RIα recovery half-time of 4.39 ± 1.2 s for smAKAP (Fig. 3I, left, gold). In contrast, the mean recovery halftime for RII is 2.19 ± 0.5 s (Fig. 3I, left, silver). The rate constant for smAKAP for RIα is 0.12 ± 0.05 s−1 (Fig. 3J, left, gold). The rate constant for RIIα is 0.18 ± 0.06 s−1 (Fig. 3I, left, silver). Thus, smAKAP displays a preference for interaction with RIα in living cells.

AKAP79 prefers RII

Photobleaching experiments with AKAP79 demonstrate greater retention of type II PKA. This anchoring protein has less membrane mobility, so images were collected at 1, 5, and 7 s following photobleaching (Fig. 3G). Representative recovery curves for AKAP79 exchange (n = 50 cells) reveal a preference for RII (Fig. 3H). Quantification of three individual experiments calculated an RI recovery half-time of 8.74 ± 0.3 s (Fig. 3I, right, gold). In contrast, the recovery half-time for RII is considerably longer at 14.4 ± 2.1 s (Fig. 3I, right, silver). Rate constants of 0.079 ± 0.003 s−1 and 0.049 ± 0.007 s−1 were calculated for RIα and RIIα exchange with AKAP79, respectively (Fig. 3J, right). These parameters provide quantitative evidence that AKAP79 exhibits selectivity for type II PKA (21, 27).

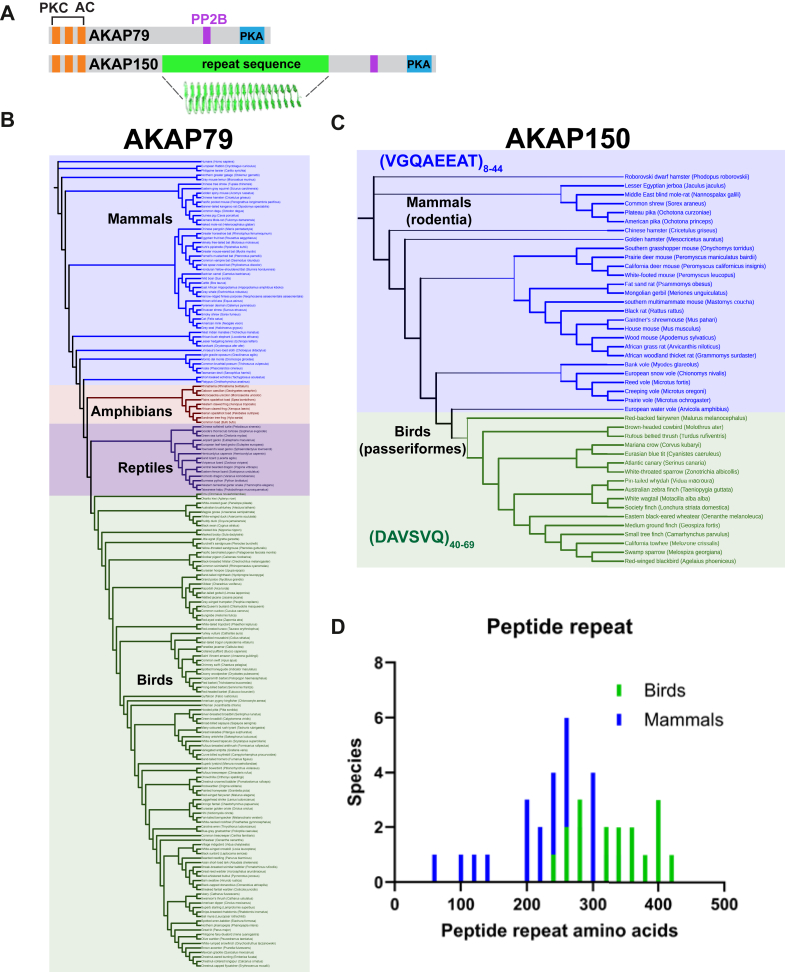

AKAP150 repeat sequences alter anchored holoenzyme topology

AKAP79 and AKAP150 are products of the AKAP5 gene (Fig. 4A; (60)). These anchoring proteins compartmentalize a variety of second messenger regulated enzymes including PKA, the phosphatase PP2B various PKC isoforms, and adenylyl cyclases (Fig. 4A; (60)). Early studies recognized a repeat sequence in murine AKAP150 that was not present in human AKAP79 (61, 62, 63). Both anchoring proteins contain an invariant PKA anchoring helix and conserved calcineurin/PP2B-binding domains (64, 65). Three conserved polybasic regions anchor adenylyl cyclases and PKC and assist in plasma membrane tethering via palmitoyl groups (66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71). AKAP150 family members are classified by an amino acid repeat sequence that is predicted to form a beta solenoid linker (Figs. 4A and S4).

Figure 4.

AKAP79/150 repeat analysis.A, diagram of domains on AKAP79 and AKAP150. Individual enzyme binding regions (adenylyl cyclase, AC), (PKC), (protein phosphatase, PP2B), (protein kinase A, PKA) are indicated. Anchoring domains are conserved, but AKAP150 contains a unique a beta-helical peptide repeat. B, cladogram of AKAP79-containing species present in all tetrapod classes. C, cladogram of AKAP150-containing species. AKAP150 restricted to the Passerine bird order and the rodent mammal order, with distinct repeat sequences: VGQAEEAT for rodents and DAVSVQ for birds. Repeat number varies by species. D, histogram of the repeat lengths (amino acids) for both passerine (green) and rodent (blue) forms, with passerine repeats being longer due to containing more repeating units.

Cladograms of AKAP79 and AKAP150 exhibit distinct patterns of species distribution (Fig. 4, B and C). AKAP79 is present in all classes of tetrapod: amphibians (orange), reptiles (purple), birds (green), and mammals (blue, Fig. 4, B and C). AKAP150 resides in 27 rodent species and 17 species of passerine birds (Fig. 4C). Remarkably, rodent AKAP150 repeat sequences differ in amino acid composition and length from passerine forms (Fig. 4, C and D). Rodents harbor an octapeptide VGQAEEAT sequence that repeats imperfectly 8 to 44 times (median 32; Fig. 4, C and D, blue). Passerine birds encode a DAVSVQ hexapeptide repeat between 40 and 69 times (median 57; Fig. 4, C and D, green). The median length for rodents is 256 amino acids (Fig. 4D, blue) as compared to 342 amino acids for birds (Fig. 4D, green). These data raise an interesting conundrum. Do AKAP150 repeat sequences alter recruitment of binding partners or allosterically impact scaffolded enzyme activities?

AKAP150 alters the topology of the anchored PKA holoenzyme

Despite their divergence, the rodent and passerine AKAP150 repeat units fold into a beta solenoid composed of parallel beta sheets as predicted by AlphaFold 3 (72). Rodent repeats have a wider region of beta strand (Fig. S4) These substructures confer stability and rigidity by forming a planar network of hydrogen bonded and extended polypeptide strands (73). Molecular modeling of anchored PKA holoenzymes in similar orientations infer structural differences between AKAP79 and AKAP150, which manifest changes in the range of motion of their anchored PKA holoenzymes (Fig. 5, A and B). AKAP79 adopts a tightly packed configuration where all five protein members of the macromolecular complex are compressed (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the beta solenoid repeat of AKAP150 separates the flanking R-C dimers to induce a more extended configuration of the anchored PKA holoenzyme (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

AKAP79/AKAP150 PKA binding analysis.A, Alphafold 3 model of AKAP79 bound to the type II PKA holoenzyme, demonstrating the close positioning of regulatory subunits. B, AKAP150 modeled with type II PKA holoenzyme. The octapeptide repeat helix wedges between the two regulatory subunits, creating an extended conformation. C and D, representative FRAP recovery curves of AKAP79 (C) and AKAP150 (D) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver), displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Mean ± SD recovery half time values included. E, recovery half times of AKAP79 (left) and AKAP150 (right) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). F, recovery rate constants of AKAP79 (left) and AKAP150 (right) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). Means ± SD (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test: ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.00, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

To test this postulate human AKAP79 and rat AKAP150, binding to R subunits was measured by FRAP (Fig. 5, C–F). The RII half-times for AKAP79 is 14.42 ± 2.1 s but it decreases to 12.26 ± 0.9 s in the presence of AKAP150 (Fig. 5, C–E silver). As expected, AKAP79 and AKAP150 recovery rates for RII were comparable at 0.049 ± 0.007 s−1 and 0.057 ± 0.004 s−1, respectively (Fig. 5, C, D, and F, silver).

Measuring rates of photorecovery serve as indices for altered membrane mobility and steric hinderance. AKAP79's recovery rate of 0.079 ± 0.003 s−1 for RIα is lower than AKAP150's rate of 0.11 ± 0.01 s−1 (Fig. 5, C, D and F, silver gold). This indicates that AKAP150 binds RI more poorly than AKAP79. This is perhaps more evident when we compare rate constants showing that RI (gold) is more readily released from AKAP150 than from the more compact AKAP79 ortholog (Fig. 5, E and F, gold). This is the first evidence that the extended beta solenoid linkers in AKAP150 subtly impact PKA anchoring. Also, our data offer the first evidence of slight physiochemical differences between the AKAP79 and AKAP150 signaling scaffolds.

Introducing RI-binding determinants into AKAP79

Informatic analyses in Figures 2A and S2 show that type I AKAP helices contain an FA motif at positions 1 and 2. We tested if this 96% conserved motif augments RI binding. Three helix mutants in AKAP79 were created: (i) introduction of the FA motif at residues 1 and 2; (ii) a palindromic AF motif at positions 17 and 18, and (iii) a quadruple mutant with FA and AF at opposite ends of the helix. A rational for this latter construct was provided by evidence that bulky aromatic residues occupy this site in type I preferring AKAPs (Fig. S2). Each AKAP79 form was tagged with GFP. GFP immune complexes were isolated from HEK293T cells. Cofractionation of R subunits was assessed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6A). AKAP79FAAF was the only variant to pull down RI (Fig. 6A, top panel, lane 4). Quantification by densitometry of data from three independent experiments confirmed a 3.55-fold enhancement of RI over controls (Fig. 6B). Antibody compatibility issues resulted in the detection of IgG heavy chain that migrates just above the RI subunit (Fig. 6A, top panel).

Figure 6.

AKAP79 PKA preference switch.A, full-length GFP-tagged AKAP79WT, AKAP79FA, AKAP79AF, and AKAP79FAAF mutants were immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells, and RI and RII coprecipitation was analyzed via immunoblot. Antibody incompatibility caused the detection of an IgG band above the RI bands (top panel). Only AKAP79FAAF precipitates RI. Both AKAP79FA and AKAP79FAAF show reduced RII binding. B, quantification of RI pulldown bands, normalized to background. AKAP79FAAF has a band intensity 3.55 times higher than the other mutants. C, quantification of RII pulldown by AKAP mutants. Data are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test: ∗p < 0.05. N-terminal helices contribute to reduced RII binding. D and E, ΔG contributions of AKAP helical amino acids from molecular dynamics (MD) experiments. Residues colored on a gradient from blue (more negative ΔG; stronger binding) to magenta (more positive ΔG; weaker binding). AKAP79FAAF shows a switch in preference from RIIα to RIα. F and G, representative FRAP recovery curves of AKAP79WT (F) and AKAP79FAAF (G) bound RIα (gold) and RIIα (silver). FRAP curves displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Mean ± SD recovery half-time values included. H and I, recovery half-times from three replicate FRAP experiments. H, RIα recovery half times from AKAP79WT (tan) and AKAP79FAAF (brown). I, RIIα recovery half times from AKAP79WT (gray) and AKAP79FAAF (slate). J and K, recovery rate constants from three replicate FRAP experiments. J, RIα rate constants from AKAP79WT (tan) and AKAP79FAAF (brown). K, RIIα rate constants from AKAP79WT (gray) and AKAP79FAAF (slate). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Student's t test: ∗∗∗p < 0.0005, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Individual side chain substitutions at either end of the AKAP79 helix decreased RII binding (Fig. 6A upper-mid panel, lanes 2–4). Densitometric analyses from three experiments confirmed that the FA and FAAF mutants decrease RII binding by 45% and the AF mutant by 22% as compared to WT AKAP79 (Fig. 6C). Control blots of cell lysates confirmed equivalent expression of endogenous R subunits and AKAP79-GFP (Fig. 6A, input panels). Ponceau staining served as loading controls (Fig. 6A, input panels). These biochemical studies indicate that AKAP79FAAF gains a binding preference toward type I regulatory subunits.

Next, we used molecular dynamics to evaluate the contribution of individual side chains in the AKAP79 and AKAP79FAAF helices (Fig. 6, D and E). Protein–protein interactions were modeled using the Amber22 molecular dynamics suite to measure the contribution of each amino acid to the total binding energy using simulations by Sander and free energy analysis with MMPBSA (74, 75, 76). Contributions of individual amino acids to the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG) are color coded. (Blue depicts increased binding; magenta denotes reduced binding; Fig. 6D). For AKAP79 binding to RIIα, leucine-2, leucine-9, and valine-10 provide the largest contributions (Fig. 6D, right). Hydrophobic side chains at positions 13 and14 bond with the central core of the RII docking domain (Fig. 6D, right).

AKAP79 interaction with RIα proceeds through a different subset of contacts. Isoleucine-18 interfaces with extra helical segments that flank the RI docking surface (Fig. 6D, left). Remarkably, leucine-9 and alanine-13 are negative RI-binding determinants (Fig. 6D).

AKAP79FAAF displays a distinctive pattern of binding (Fig. 6E). The FA dimer and its palindromic AF pair alter the overall conformation of the amphipathic helix (Fig. 6E, left panel). This promotes slight changes in the orientation of isoleucine-3, valine-10, isoleucine-14, and phenylalanine-18 (Fig. 6E, left panel). Hence, structural alterations at four turns of the helix favor interaction with the D/D domain of RIα. These topological changes act synergistically to bias the AKAP79FAAF helix toward type I PKA anchoring.

FRAP was used to test this postulate (Fig. 6, F and G). AKAP79FAAF demonstrates an RIα preference, with a recovery half-time of 20.5 ± 2.0 (n = 3) seconds (Fig. 6G, gold & 6H, brown). This value is more than double WT AKAP79's half-time of 8.74 ± 0.34 s (Fig. 6F, gold, 6H tan). Conversely, the AKAP79FAAF mutant is less able to bind RII with a recovery half-time of 11.4 ± 2.0 s as compared to 14.4 ± 2.1 s for WT AKAP79 (Fig. 6, F and G, sliver, and I). Rate constants compare the recovery independent of the mobile fraction (Fig. 6, J and K). The mean RIα rate constant for AKAP79FAAF is 0.034 ± 0.003 s−1 as compared to 0.079 ± 0.003 s−1 for AKAP79 (Fig. 6J). Rate constants of 0.062 ± 0.01 s−1 and 0.049 ± 0.007 s−1 were measured for RII interaction with AKAP79FAAF and the WT anchoring protein (Fig. 6K). These biophysical results argue that the AKAP79FAAF helix switches PKA regulatory subunit binding preference toward RI.

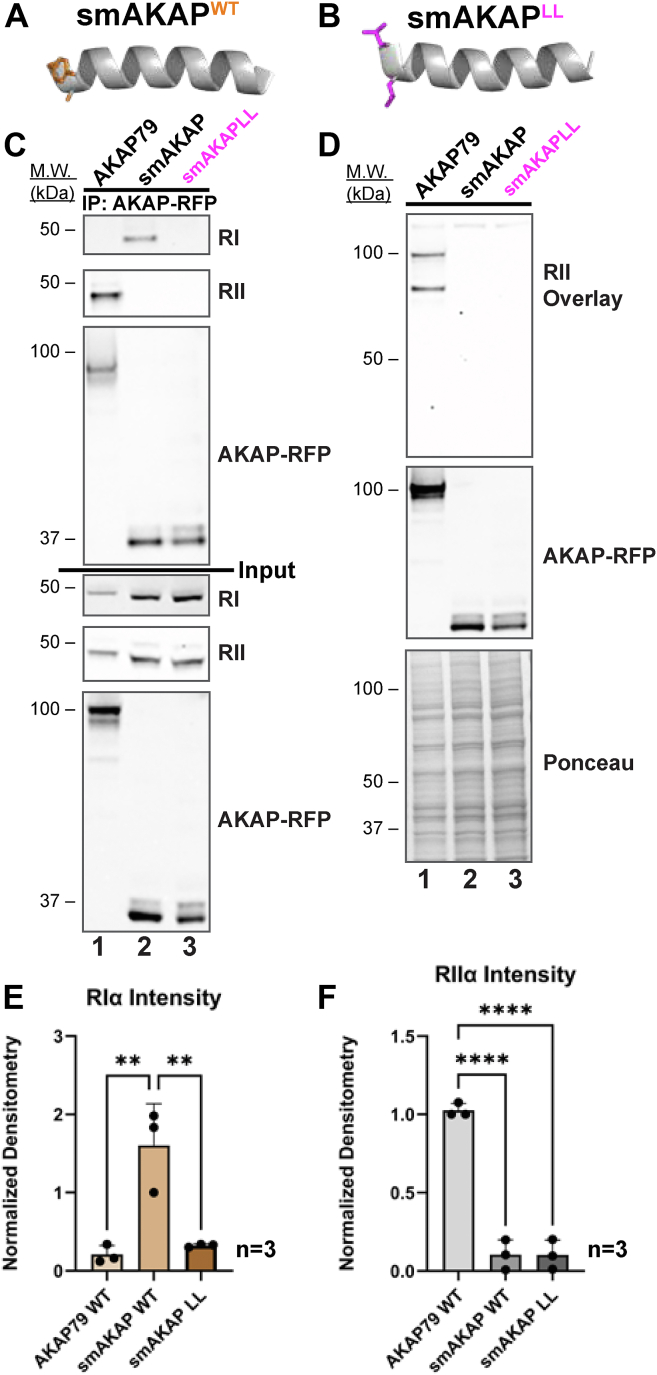

Removal of the FA motif abolishes smAKAP interaction with RI

Reciprocal studies show that replacement of the FA motif in smAKAP alters RI interaction. These studies were conducted in two ways. First, mRFP-tagged versions of smAKAP, smAKAPLL, and AKAP79 were expressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. 7, A and B). RFP immune complexes were probed for coprecipitation of R subunits using antibodies selective for RI or RII (Fig. 7C). Immunoblot data presented in Figure 7C top panel shows that RIα only coprecipitates with native smAKAP (lane 2). Importantly, RIα is refractory to interaction with the smAKAP-YA61LL mutant (lane 3). Conversely, RIIα only coprecipitates with AKAP79 (Fig. 7C, top mid panel, lane 1). These experiments show that loss of the YA motif in smAKAP abolishes interaction with RI. Immunoblot detection of each protein confirmed equivalent expression of each component in cell lysates (Fig. 7C, bottom panels). Second, control RII overlay experiments show that both smAKAP forms are unable to interact with RII (Fig. 7D, top panel, lanes 2 & 3). Detection of AKAP79 by RII overlay served as a positive control (Fig. 7D, top panel, lane 1). Immunoblot staining of AKAP-mRFP forms show equivalent expression of each component, and Ponceau staining detected proteins in cell lysates (Fig. 7D, lower panels). Quantification of three independent experiments was conducted by densitometry (Fig. 7, E and F). Collectively, these findings show that the YA motif is a key determinant for smAKAP interaction with RIα. Furthermore, replacement of this motif with the corresponding sequence on AKAP79 is not sufficient to switch smAKAP-binding preference toward the type II PKA.

Figure 7.

The amino terminal aromatic motif is necessary for smAKAP interaction with RI.A and B, models depicting the anchoring helix of smAKAP WT (orange side chains) and the smAKAPLL mutant (magenta side chains). Full-length mRFP-tagged AKAP79, smAKAP, and smAKAPLL were immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells. C, coprecipitation of RI (top) or RII (upper) was analyzed by immunoblot. Only smAKAP precipitates with RI. Neither smAKAP or the LL mutant interact with RII. Coprecipitation of RII with WT AKAP79 served as a loading control. Molecular weight markers and loading controls are indicated. D, full-length mRFP-tagged AKAP79, smAKAP, and smAKAPLL were immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells. Top: interaction with RII was assessed by RII overlay. Mid: immunoblot detection of AKAP-RFP confirmed equivalent levels of each anchoring protein. bottom: ponceau staining demonstrated protein expression of cell lysates. Molecular markers are indicated. E and F, quantification of (E) RI coprecipitation and (F) RII overlay with AKAP variants from three independent experiments. Data are shown as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test: ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Functional analyses of AKAP79FAAF action

Adrenal Cushing's syndrome is a disease of cortisol hypersecretion often caused by somatic mutations in the PKA catalytic subunit (77, 78). Cushing's mutations prevent incorporation of PKAc into AKAP signaling islands (79, 80). To test the consequences of biased RI signaling in a physiological context, we monitored the ability AKAP79FAAF to impact stress hormone release from adrenal cells (Fig. 8A). PKAc-W196G is a recently identified Cushing's kinase that preferentially associates with RI (81). Hence, PKAcW196G is favorably recruited to type I AKAP signaling islands (81). We reasoned that expression of AKAP79FAAF should sequester type I holoenzymes away from mitochondrial PKA substrates that drive stress hormone biosynthesis (Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

Rescue of Cushing's syndrome by AKAP79FAAF. A, model depicting how AKAP79FAAF restores corticosterone release in Cushing's syndrome. PKAcW196G is displaced from type II PKA holoenzymes, such as those bound by AKAP79WT (orange). Mislocalized PKAc drives ectopic phosphorylation of mitochondrial substrates. Membrane relocalization of the type I holoenzyme subunit by AKAP79FAAF (magenta) separates the mutant C subunit from the mitochondria, reducing corticosterone release. B, normalized corticosterone levels measured from ATC7L PKAcW196G cells stably expressing either AKAP79WT (orange) or AKAP79FAAF (magenta). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Student's t test: ∗∗p < 0.005.

ATC7L mouse adrenal cells infected with bicistronic lentiviral vectors expressing PKAcW196G/BFP tonically produce corticosterone (the murine cortisol analog) (81). These cell lines were co-infected with lentiviral vectors encoding either AKAP79WT/GFP or AKAP79FAAF/GFP. Populations of double fluorescent cells were sorted via FACs. Corticosterone levels were measured by ELISA assay and normalized to total protein content. These hormone measurements revealed that AKAP79FAAF reduced corticosterone levels by 61.5 ± 0.8% (n = 3) as compared to the WT anchoring protein (Fig. 8B). Thus, introduction of AKAP79FAAF helix in the context of the full-length anchoring protein is sufficient to promote type I PKA signaling inside cells.

Discussion

This report charts the emergence of AKAPs and amino acid determinants that confer anchoring selectivity toward the type I or type II PKA holoenzymes. Phylogenetic analyses presented in Figure 1 indicate that the first AKAPs appear around the advent of the RI⍺ and RII⍺ subunits. Hence the formation of primordial R/AKAP interfaces paved the way for compartmentalization of the catalytic subunits of the kinase (1). The ancestral anchoring proteins OPA1, dAKAP2, and AKAP28 are present in Porifera. These sea sponges are sessile filter feeders bound to the seabed (82). They lack nervous systems, have an extremely simple cellular organization, but contain mitochondria and primary cilia (83). Hence mitochondrial tethering of PKA may be the seminal signaling roles for OPA1 and dAKAP2. In contrast, the principal function of AKAP28 in simple organisms is less clear. This anchoring protein gained biological roles during metazoan development as mammalian AKAP28 orthologs fulfill dual signaling and architectural roles in motile cilia and flagella. This is because AKAP28 is equally adept at interfacing with the R subunits of PKA and other classes of D/D domain–containing proteins (41, 84). This latter cohort of “R1D2 and R2D2” proteins include ROPN1L, SPA17, and CAYBR. They utilize the AKAP–D/D interface to build structural integrity into motile cilia and coordinate flagellar motility (41, 84). Circumstantial support for the broader architectural role of AKAP28 comes from sequence alignment data presented in Fig. S1. This anchoring helix is noticeably less conserved as compared to OPA1 and dAKAP2. This may allow AKAP28 to accommodate its broader repertoire of D/D domain protein-binding partners.

The explosion of AKAPs in the vertebrate clade highlighted in Figure 1 coincides with the increasing complexity of cellular processes. Interestingly, this is not an example of divergent evolution, as AKAPs do not originate from a single ancestral gene. Rather the parallel appearance of fourteen AKAPs at the base of the vertebrate clade argues that introduction of the PKA anchoring helix was an advantageous feature to enhance partitioning of cAMP signaling (1). Accordingly, anchoring proteins that coordinate PKA signaling at plasma membranes (AKAP18), mitochondria (SKIP), cytoskeleton (ERM proteins), perinuclear membranes (mAKAP), centrosomes (Yotiao/AKAP350), and vesicles (AKAP220) emerged simultaneously (Fig. 1). A later development was the appearance of RIβ and RIIβ isoforms. These regulatory subunits are enriched in the central nervous system and organize complex behaviors such as excitatory synaptic transmission and molecular elements of learning and memory (60, 85, 86). Anchoring proteins such as MAP2 and AKAP79 appeared to accommodate these neuronal roles. These AKAPs cluster groups of second messenger kinases and phosphatases to sustain bidirectional regulation of key phosphorylation events in synaptic dendrites and axons (21). Another feature of the AKAP expansion is the use of alternative splicing to generate differentially compartmentalized AKAP families. The mammalian AKAP2 and AKAP7 genes encode families of anchoring proteins called AKAP-KL and AKAP18, respectively. While AKAP-KL family members exhibit tissue-specific expression, the AKAP18 isoforms utilize different targeting motifs to sequester short and long isoforms at the plasma membrane, sarcolemma, and nucleus (18, 87). These adaptations expand the organellar scope and multiplicity of compartmentalized PKA action (3). Another notable development was the emergence of the type I PKA selective anchoring proteins SKIP, GRP161, and smAKAP (Fig. 1). These anchoring proteins appeared simultaneously with type II selective MAP2 and AKAP-lbc, followed by the later arrival of AKAP79/150. Hence local PKA isotype selective signaling had diverged by the appearance of mammals. One advantage may be to exploit the fourfold greater sensitivity for cAMP of RI as compared to RII. Consequently, type I PKA responses would be prolonged within AKAP signaling islands maintained by SKIP, GRP161, and smAKAP (88).

Systematic investigation of the smAKAP and AKAP79 helices was performed on these prototypic type I and type II selective anchoring proteins. Both anchoring proteins are amenable to the use of TIRF microscopy as an analytical tool to track protein dynamics at the plasma membrane that is more sensitive than most biochemical approaches (89). As anticipated, FRAP measurements presented in Figure 3 F and H indicate that smAKAP and AKAP79 exhibit clear preferences for their favored R subunit–binding partner. Phylogenetic analyses presented in Figure 4 prompted additional FRAP studies to compare the dynamics of AKAP79 and AKAP150 orthologs. These latter experiments investigate a long recognized genetic curiosity. Certain rodent and bird AKAP5 gene products encode proteins of differing molecular weights that correspond to AKAP79 and AKAP150 (57, 90). The larger size of AKAP150 is provided by repeat sequences that are predicted to form a parallel beta solenoid linker (91). Remarkably, the length, sequence, and number of repeats is different in the passerine bird and rodent AKAP150 orthologs (Fig. 4D). AlphaFold 3 models further predict distinct beta solenoid configurations in AKAP150's of bird and rodent origin (Fig. S4-Supplement 1). The bird “hexapeptide” (DAVSVQ) may function as a dodecapeptide repeat that adopts an oval shaped “O-type” conformation where the upper and lower faces of the beta solenoid are joined by linker amino acids. Conversely, the rodent octapeptide (VGQAEEAT) repeat assumes a triangular “T-type” helix, with a 4-amino acid beta sheet and a 4-residue linker per face of the triangle. Modeling studies presented in Figure 5 suggest that the positioning of the beta solenoid in AKAP150 limits the flexibility of the anchored PKA holoenzyme to extend the distance between PKAc subunits. This elongated topology remains within the 200 to 400 Å range of motion calculated for active and intact PKA holoenzymes (10, 92). Structural and functional studies will be necessary to confirm or refute this intriguing postulate.

Bioinformatic and biophysical data presented in Figures 2 and 5 highlight the conservation of FA or YA dipeptides at positions 1 and 2 in AKAP helices as determinants for RI anchoring. This is perhaps most evident in the alignment of six consensus RI anchoring logos presented in Fig. S2-Supplement 1. This shows that this dipeptide is almost invariant in orthologs of the RI selective anchoring proteins smAKAP, SKIP, and AKAP3 (93, 94). The aromatic side chains phenylalanine or tyrosine are equally tolerated at position 1 with alanine being almost invariant at the second position. Interestingly, the synthetic RI selective anchoring disruptor peptide RIAD contains a YA motif albeit in the second turn of the amphipathic helix (12, 29, 95). Structural modeling indicates that the FA motif interfaces with short flanking helixes that are unique to the docking and dimerization domain of RI. Tandem type I PKA selective helices have been identified in the mitochondrial anchoring protein SKIP (Fig. 2 and Supplements 1 and 2 (93)). Further evidence to support the importance of the FA motif as an RI anchoring determinant is provided by data in Figure 7 showing thar replacement of this dipeptide with a corresponding region in AKAP79 abolishes interaction with RIα. The FA motif is also conserved in the distal PKA anchoring helix (residues 1633–1646) of AKAP220 (96, 97). This region exhibits selectivity for RI whereas the proximal site on AKAP220 (residues 610–623) only anchors type II PKA (96). Thus, AKAP220 and SKIP represent a unique class of anchoring proteins that sequester multiple PKA holoenzymes to amplify cAMP responses at vesicles and mitochondria, respectively.

Amalgamated sequence alignments of AKAP helices from recognized RI and RII anchoring proteins presented in Figure 2 and 2B emphasize different regions of conservation. Although hydrophobic pairs are conserved in both consensus logos, alignments of type I selective AKAPs presented in Figure 2 and Fig. S2-Supplement 1 identify another conserved hydrophobic pair at the opposite end of anchoring helix. This is particularly evident in smAKAP where the WA/V pair at positions 17 and 18 of the helix is invariant across 219 orthologs (Fig. 2E). Molecular dynamic simulations presented in Figure 5E suggest that RI binding to FA motifs contact the flanking helices of RI. The analogous WA/V pair may contribute to similar contacts. These residues help to guide the positioning of side chain determinants dispersed along the hydrophobic face of the AKAP amphipathic helix. Such an induced realignment enhances preferential association of type I AKAPs with the more rigid and disulfide bonded core of the RIα D/D domain. Another intriguing prospect is that hydrophobic pairs at either end of the AKAP helix may form a palindromic binding surface. These determinants can interface with the symmetric RI D/D domain in either a forward or backward orientation. This concept is supported by recent evidence that the PKA-binding helix in MAP2 can complex with the R subunits in either an N to C or C to N orientation (98). Also, residues proximal to the anchoring helix may further contribute to R subunit interactions. For example, hydrophilic anchor points outside the core AKAP18–RIIα interface contribute to PKA anchoring whereas a nonnatural linear segment of a peptide that disrupts the AKAP function of PI 3 kinase g is being developed as a therapeutic for cystic fibrosis (99, 100). These latter examples suggest possible variation as to how AKAPs utilize their anchoring helices to bind R subunits.

Hypercortisolism is a pathological consequence of somatic mutations in PKAc that drive adrenal Cushing's syndrome (77). We took advantage of PKAcW196G, a Cushing's kinase that only associates with RI to test the functionality of recruitment into type I AKAP signaling islands (81). Data presented in Figure 8 shows that introduction of FA and AF pairs at opposite ends of the AKAP79 helix not only switches binding preference toward RIα but reduces stress hormone production in adrenal cells expressing PKAcW196G. These cell-based studies illustrate how modification of only a few side chains have profound effects on PKA subtype–binding preference in the context of a full-length anchoring protein. This may be particularly important for type I AKAPs as accumulating evidence indicates that RIα is elevated in certain endocrine disorders, heart disease, and cancers (101, 102, 103, 104). A logical next step is to test if PKA association with type I AKAPs is strengthened under pathological conditions to create venues for aberrant cAMP signaling.

Experimental procedures

Evolutionary analysis of AKAPs

AKAP and PKA orthologs were acquired through clustered NCBI BLAST searches on the human isoform of each protein. Nonmetazoan orthologs were acquired in tandem with nonclustered BLAST searches excluding the metazoan taxa. The search size limit was set to 1000 sequences to ensure coverage of orthologs. The raw sequences from the blast search were then curated by removing any sequences labeled “hypothetical,” “low quality,” “predicted,” or sequences attributed to different proteins than the target of the search. Finally, the presence of a D/D domain for PKA regulatory subunits and the amphipathic helix for AKAPs was determined, and proteins lacking either motif were excluded.

The collections of protein orthologs were aligned in Mega11 using the MUSCLE algorithm or CLUSTALω (the alignment with the fewest gaps was used). Aligned sequences were then fed into the phylogenic tree generating tool IQTREE on the CIPRES gateway for the construction of maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees. Trees were visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life server.

Cladograms were generated by including nodes which contain high-quality orthologs of examined proteins. These were placed on a tree which traces the evolutionary relationships between metazoans. The last common ancestors are represented by the root point.

Selected protein-interaction domains on AKAPs were isolated to make conservation logos of the amino acids contained in each motif using the program Weblogo. Larger letters represent greater degrees of conservation.

FRAP experiments

WT U2OS cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum on 35 mm glass bottom culture dishes (Mattek) at a starting density of 100,000 cells/dish. Cells were cotransfected with an iRFP-tagged regulatory subunit (RIα or RIIα) and an mRFP-tagged AKAP 48 h before imaging using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus) in Opti-MEM (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions. Media was replaced with HBSS media prior to imaging. Imaging was performed on a Deltavision OMX using a 60× TIRF objective lens and immersion oil with a refractive index of 1.522.

FRAP experiments were conducted on the Cy5 channel, with an excitation wavelength of 640 nm, an exposure time of 21 ms, and a transmittance (%T) of 80% in TIRF mode. FRAP videos had a frame rate of 500 ms and a duration of 45 s. Photobleaching on spot mode occurred 2 after 2 baseline frames and lasted for one frame. The photobleach duration was 50 ms at 80% power. Ninety one frames in total were collected. FRAP videos were not deconvolved or in any other way processed prior to analysis and quantification.

FRAP video analysis

Bleach spots, whole cell area, and background were measured in ImageJ (FIJI) with a 2.022 micron diameter circle on each frame of the video. These were collected into 50 sets of measurements per experiment. These sets were uploaded to the EasyFRAP server, which performed background normalization, background photobleaching correction, and normalization of the curves (“double normalization”). The points of each FRAP recovery curve (n = 50) were then displayed in GraphPad Prism. Analysis of each curve was performed by deleting the prebleach points and performing a one phase association curve-fit equation . The rate constants (s-1) and recovery half-times were collected in bar graphs to compare differences in AKAP anchoring of regulatory subunits.

Protein modeling

Predictive protein models were generated using the Alphafold3 server (Google DeepMind). Representative models were chosen based on agreement of the five models provided, as well as agreement with known elements of protein structure (when available). Models were colored and positioned using Pymol 3.1 (Schrödinger).

Molecular dynamics

To assess mutations that would confer RI affinity to AKAP79, we performed molecular dynamics simulations using Amber23 on AKAP–D/D domain complexes. The solution NMR structure of AKAP79 bound to the Rattus norvegicus RIIα D/D domain [PDB: 2H9R] and the co-crystal structure of human smAKAP bound to the Bos taurus RIα D/D domain [PDB:5HVZ] were the starting structures for mutant generation. The crystal structures were first processed using the module pdb4amber, which removes water, ions, and hydrogens from the PDB structures, and designates cysteines that form disulfide bridges. Mutagenesis on the AKAP helices was performed using the program scwrl4. AKAP79 and RI mutants were created with emphasis on keeping the hydrophobic anchor points aligned with corresponding positions of the smAKAP helix. Both WT and mutant structures were then parameterized using the LEAP module of Amber, using the protein force field ff19sb and the water force field “optimal” three-charge, four-point rigid water model (OPC). Protein negative charges were neutralized with sodium ions, then solvated in a 12.0 Å octahedral solvent box; then both sodium and chloride ions were added to achieve a physiological salt concentration of 150 mM.

MD simulations were performed using the Amber module pmemd. The proteins were equilibrated by running two minimization runs, first with no bond restraints and then with restraints on hydrogen bonds. Each minimization starts with the steepest descent method and for 1000 cycles and then switches to conjugate gradient descent. Step size after both minimizations is 2 femtoseconds. Heating occurred over 50 ps from 0 K to 300 K using Langevin dynamics and H-bond restraints. Pressure was raised to 1 bar over 50 ps using the Berendsen barostat while maintaining temperature at 300 K with H-bond restraints. Equilibration occurred over 500 ps with no restraints on H-bonds, at 300K and 1 bar. The output files were processed in cpptraj to assess total energy, density, temperature, and backbone RMSD.

Output coordinate files from the equilibration were used to perform production runs on pmemd. Four identical unrestrained MD production simulations were performed sequentially for 8 ns with a step size of 2 fs, using the pressure and temperature conditions as the equilibration run with trajectories being sampled every 10 ps. Simulations were combined, and trajectories were processed using MMPBSA.py using Poisson Boltzmann models to measure the binding free energy of the complex and then to break down the energetic contribution of individual amino acids. In Pymol 3.1 (Schrödinger), the per-residue binding energy of each AKAP helix amino acid was normalized to highlight the influence of each sidechain and mapped onto a gradient of blue to magenta (with blue representing a more negative ΔG and magenta a more positive ΔG) and used to color the individual amino acids of the AKAP helix according to binding free energy.

Generation of AKAP79 mutants

The AKAP79 FA, AF, FAAF mutants were generated from a human 10xHIS-AKAP79-EGFP N1 construct cloned in with HindIII (NEB) and AgeI (NEB) followed by site-directed Phusion mutagenesis with the following primers (FA mutant forward primer- AATATGAAACATTCGCAATTGAAACAGCCTCTTCTCTAG, reverse primer- GTTCTGAAGTTCTATCCTCAAAACCATTATCATTAG, AF mutant forward primer- GTTAATGAAATGGCCTCTGATGATAATAAAATAAAC, reverse primer- CAGCTGTTCAAATGCCAACTGAATAG, and FAAF mutant forward primer- CGTTATCCTCGAACTGCTGCATAGACTGAGC, reverse primer- CAGCTGTTCAAATGCCAACTGAATAG). PCR was run for 25 cycles using Phusion Plus Green master mix at a TM of 60 °C (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 1.6 ng of template DNA and 0.4 μl of 10 μM forward and reverse primers each. Methylated parent plasmid DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme DPNI (NEB) for 1 h at 37 °C, then linear DNA was phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) for 30 min at 37 °C and ligated with T4 ligase (NEB) before transformation into GC10 chemically competent cells (Genessee Scientific). mRFP and iRFP fusion plasmids were simultaneously generated through restriction cloning of the AKAPs into the mRFP and iRFP backbones using AgeI (NEB) and HindIII (NEB).

Cell culture and generation of lentiviral lines

U2OS cells were maintained in culture using DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For FRAP experiments, U2OS cells were transiently cotransfected with fluorescently tagged AKAP and R subunit constructs using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus) in Opti-MEM (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions.

WT and FAAF AKAP79 N1 constructs were used to generate AKAP79WT/FAAF pSMAL lentiviral plasmids using Gateway cloning (Invitrogen) in STBL3 cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viral particles were produced in HEK293T cells via cotransfection of the pSMAL constructs, PMD2.G, and psPAX2 (gifts from Didier Trono; Addgene plasmid #12259 [RRID:Addgene_12259] and plasmid #12260 [RRID:Addgene_12260]) with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Viral particles were collected and spin concentrated using PEG-IT (System Biosciences). ATC7L PKACW196G pSMALB cells were transduced with 10, 50, 200, and 500 μl concentrated viral particles using 1 μg/μl polybrene (Santa Cruz). Green fluorescence was monitored on a Keyence BZ800 microscope, and the 500 μl virus condition cells were chosen due to robust expression. The cells were then sorted on a BD FACS ARIA III for expression of both BFP (PKACW196G) and GFP (AKAP79WT/FAAF). Cells were treated with 1 nM ACTH (Sigma-Aldrich) in dimethyl sulfoxide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) after sorting to promote even expression of corticosterone biosynthesis proteins. ATC7L cell lines were maintained in culture using DMEM/F12 (Cytiva) with 1× ITS supplement (Sigma Aldrich), 2 mM l-glutamine (Cytiva), 5% horse serum (Life Technologies), and 5% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Immunoprecipitations

Cell lysates were prepared from HEK293 cells transfected with 1 μg of AKAP79WT/FA/AF/FAAF-EGFP N1 using HSEF lysis buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), 150 mM NaCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 mM NaF (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 mM tris (pH 7.5 at 4 °C) (Thermo Fisher scientific) along with 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μM leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM benzamidine (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were incubated for 10 min on ice and then spun at 15,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured by BCA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and lysates were diluted to 1 mg/ml using lysis buffer. Samples (500 μl) were precleared by rotating with 20 μl of protein G agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (50% in lysis buffer) for 1 h at 4 °C. Supernatants were then incubated with 1 μg of goat anti-GFP antibody (Rockland) for 16 h. Thirty microliters of protein G agarose (50% in lysis buffer) was then added, and samples were returned to rotation for 1 h. Beads were washed with HSEF lysis buffer, centrifuged for 1 min at 6000g and 4 °C three times, and the buffer was aspirated with a 27-gauge needle before resuspending in 1 × lithium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (3% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), final) and heating at 85 °C for 10 min. IP lanes were paired with input conditions made from the same lysate, with the volume adjusted to load 30 μg of protein per condition and heated alongside IP samples. Samples were run on Bolt 4 to 12% Bis-Tris Plus gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose for immunoblotting and probed with α-PKA RIα rabbit (Cell Signaling), α-PKA RIIα mouse (BD), or α-GFP rabbit (Life Technologies) primary antibodies. Detection was achieved with HRP-conjugated mouse and rabbit secondary antibodies (GE Life Sciences), followed by treatment with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaging on an iBright FL1000 gel imaging system (Invitrogen). Densitometry was performed using NIH ImageJ (FIJI) software. Band intensity was normalized to total protein loading via ponceau stain. Figures are representatives of three experimental replicates.

Corticosterone measurements

Cells were washed in PBS (Cytiva) and the media was replaced with DMEM/F12 (no supplements) (Cytiva) 24 h before harvest. Media samples were snap-frozen prior to analysis. Cells were lysed in HSEF lysis buffer and protein levels were measured via BCA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Media samples were diluted and subjected to measurement using Corticosterone ELISA kits (Cayman). The absorbance of three replicates per sample was measured using a plate reader. Data was fit to a standard curve. Measurements were completed in three separate biological replicates. Measurements were first normalized to protein concentration and then to the control for each replicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism using either two-tailed Student's t-tests (for comparisons of two groups) or one-way ANOVAs with Tukey's multiple comparison test (for comparisons of more than two groups). The number of measurements (n) is provided on representative FRAP timecourses and number of independent experiments (n) is provided on graphs of combined data.

Sample size and replicates

The sample size was not experimentally determined. For photobleaching experiments (Figs. 3, 5, and 6), n = 50 measurements were conducted across n ≥ 3 independent experiments. For both the immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6) and corticosterone (Fig. 7) experiments, n = 3 separate experiments were conducted.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this manuscript.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Nelson for administrative support.

Author contributions

J. I. F., K. H. C., M. K., B. J. O., K. A. F., and J. D. S. writing–review and editing; J. I. F. and J. D. S. writing–original draft; J. I. F., M. K., B. J. O., and J. D. S. visualization; J. I. F., M. K., K. A. F., and J. D. S. validation; J. I. F. software; J. I. F., K. A. F., and J. D. S. resources; J. I. F., M. K., and J. D. S. project administration; J. I. F., K. H. C., M. K., and B. J. O. methodology; J. I. F., K. H. C., M. K., B. J. O., and J. D. S. investigation; J. I. F., K. H. C., M. K., B. J. O., and J. D. S. formal analysis; J. I. F., K. H. C., M. K., B. J. O., and J. D. S. data curation; J. I. F., K. H. C., B. J. O., M. K., and J. D. S. conceptualization; J. D. S. supervision; J. I. F., K. A. F., and J. D. S. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

J. F. is supported by DK141129 and NS111573. K. C. by metabolic training grant 2T32DK007247-46 and J. D. S. is supported by NIH grants DK119192 and CA279997. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Wolfgang Peti

Supporting information

References

- 1.Turnham R.E., Scott J.D. Protein kinase A catalytic subunit isoform PRKACA; History, function and physiology. Gene. 2016;577:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco E., Fortunato S., Viggiano L., de Pinto M.C. Cyclic AMP: a polyhedral signalling molecule in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4862. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langeberg L.K., Scott J.D. Signalling scaffolds and local organization of cellular behaviour. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:232–244. doi: 10.1038/nrm3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krebs E.G., Blumenthal D.K., Edelman A.M., Hales C.N. In: Mechanisms of Receptor Regulation. Crooke S.T., Poste G., editors. Plenum; New York: 1985. The functions of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase; pp. 324–367. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos J.L. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:733–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs Erin L., Brutinel Evan D., Jones Adriana K., Fulcher Nanette B., Urbanowski Mark L., Yahr Timothy L., et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa vfr regulator controls global virulence factor expression through cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:3553–3564. doi: 10.1128/JB.00363-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng X., Fu Z., Su D., Zhang Y., Li M., Pan Y., et al. Mechanism of ligand activation of a eukaryotic cyclic nucleotide−gated channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:625–634. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0433-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong W., Scott J.D. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:959–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor S.S., Ilouz R., Zhang P., Kornev A.P. Assembly of allosteric macromolecular switches: lessons from PKA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:646–658. doi: 10.1038/nrm3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith F.D., Esseltine J.L., Nygren P.J., Veesler D., Byrne D.P., Vonderach M., et al. Local protein kinase A action proceeds through intact holoenzymes. Science. 2017;356:1288–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skalhegg B.S., Tasken K. Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Differential expression,regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front. Biosci. 2000;5:D678–D693. doi: 10.2741/skalhegg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omar M.H., Scott J.D. AKAP signaling islands: venues for precision pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;41:933–946. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaccolo M., Kovanich D. Nanodomain cAMP signalling in cardiac pathophysiology: potential for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. Physiol. Rev. 2024;105:541–591. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bock A., Irannejad R., Scott J.D. cAMP signaling: a remarkably regional affair. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024;49:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2024.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anton S.E., Kayser C., Maiellaro I., Nemec K., Moller J., Koschinski A., et al. Receptor-associated independent cAMP nanodomains mediate spatiotemporal specificity of GPCR signaling. Cell. 2022;185:1130–1142.e1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bock A., Annibale P., Konrad C., Hannawacker A., Anton S.E., Maiellaro I., et al. Optical mapping of cAMP signaling at the nanometer scale. Cell. 2021;184:2793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irannejad R., Tsvetanova N.G., Lobingier B.T., von Zastrow M. Effects of endocytosis on receptor-mediated signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;35:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith F.D., Omar M.H., Nygren P.J., Soughayer J., Hoshi N., Lau H.-T., et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms alter kinase anchoring and the subcellular targeting of A-kinase anchoring proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E11465–E11474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816614115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadana R., Dessauer C.W. Physiological roles for G protein-regulated adenylyl cyclase isoforms: insights from knockout and overexpression studies. Neurosignals. 2009;17:5–22. doi: 10.1159/000166277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tasken K., Aandahl E.M. Localized effects of cAMP mediated by distinct routes of protein kinase A. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:137–167. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser I.D., Scott J.D. Modulation of ion channels: a "current" view of AKAPs. Neuron. 1999;23:423–426. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80795-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lester L.B., Langeberg L.K., Scott J.D. Anchoring of protein kinase A facilitates hormone-mediated insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:14942–14947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshi N., Langeberg L.K., Scott J.D. Distinct enzyme combinations in AKAP signalling complexes permit functional diversity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ncb1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott J.D., Pawson T. Cell signaling in space and time: where proteins come together and when they're apart. Science. 2009;326:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1175668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr D.W., Stofko-Hahn R.E., Fraser I.D., Bishop S.M., Acott T.S., Brennan R.G., et al. Interaction of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase with RII-anchoring proteins occurs through an amphipathic helix binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14188–14192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newlon M.G., Roy M., Morikis D., Hausken Z.E., Coghlan V., Scott J.D., et al. The molecular basis for protein kinase A anchoring revealed by solution NMR. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:222–227. doi: 10.1038/6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr D.W., Hausken Z.E., Fraser I.D., Stofko-Hahn R.E., Scott J.D. Association of the type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase with a human thyroid RII-anchoring protein. Cloning and characterization of the RII-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13376–13382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alto N.M., Soderling S.H., Hoshi N., Langeberg L.K., Fayos R., Jennings P.A., et al. Bioinformatic design of A-kinase anchoring protein-in silico: a potent and selective peptide antagonist of type II protein kinase A anchoring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:4445–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson C.R., Lygren B., Berge T., Hoshi N., Wong W., Tasken K., et al. Delineation of type I protein kinase A-selective signaling events using an RI anchoring disruptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21535–21545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold M.G., Lygren B., Dokurno P., Hoshi N., McConnachie G., Tasken K., et al. Molecular basis of AKAP specificity for PKA regulatory subunits. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.León D.A., Herberg F.W., Banky P., Taylor S.S. A stable α-helical domain at the N terminus of the RIα subunits of cAMP-dependent protein kinase is a novel dimerization/docking motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28431–28437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banky P., Roy M., Newlon M.G., Morikis D., Haste N.M., Taylor S.S., et al. Related protein-protein interaction modules present drastically different surface topographies despite a conserved helical platform. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Søberg K., Moen L.V., Skålhegg B.S., Laerdahl J.K. Evolution of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) catalytic subunit isoforms. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinton N., Haugen T.B., Ørstavik S., Skålhegg B.S., Hansson V., Jahnsen T., et al. The gene encoding the Cγ catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase is a transcribed retroposon. Genomics. 1998;49:290–297. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toda T., Cameron S., Sass P., Zoller M., Scott J.D., McMullen B., et al. Cloning and characterization of BCY1, a locus encoding a regulatory subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 1987;7:1371–1377. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahlin H.R., Zheng N., Scott J.D. Beyond PKA: evolutionary and structural insights that define a docking and dimerization domain superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nei M., Kumar S. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2000. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogne M., Chu D.T., Küntziger T.M., Mylonakou M.N., Collas P., Tasken K. OPA1-anchored PKA phosphorylates perilipin 1 on S522 and S497 in adipocytes differentiated from human adipose stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2018;29:1487–1501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-09-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tingley W.G., Pawlikowska L., Zaroff J.G., Kim T., Nguyen T., Young S.G., et al. Gene-trapped mouse embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes and human genetics implicate AKAP10 in heart rhythm regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pidoux G., Witczak O., Jarnæss E., Myrvold L., Urlaub H., Stokka A.J., et al. Optic atrophy 1 is an A-kinase anchoring protein on lipid droplets that mediates adrenergic control of lipolysis. EMBO J. 2011;30:4371–4386. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kultgen P.L., Byrd S.K., Ostrowski L.E., Milgram S.L. Characterization of an A-kinase anchoring protein in human ciliary axonemes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:4156–4166. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCartney S., Little B.M., Langeberg L.K., Scott J.D. Cloning and characterization of A-kinase anchor protein 100 (AKAP100): a protein that targets a-kinase to the sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9327–9333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grönholm M., Vossebein L., Carlson C.R., Kuja-Panula J., Teesalu T., Alfthan K., et al. Merlin links to the cAMP neuronal signaling pathway by anchoring the RIβ subunit of protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41167–41172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabrovsek L., Collins K.B., Aggarwal S., Saunders L.M., Lau H.-T., Suh D., et al. A-kinase-anchoring protein 1 (dAKAP1)-based signaling complexes coordinate local protein synthesis at the mitochondrial surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:10749–10765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng M., Aye T.T., Snel B., van Breukelen B., Scholten A., Heck A.J.R. Spatial organization in protein kinase A signaling emerged at the base of animal evolution. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:2976–2987. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilouz R., Lev-Ram V., Bushong E.A., Stiles T.L., Friedmann-Morvinski D., Douglas C., et al. Isoform-specific subcellular localization and function of protein kinase A identified by mosaic imaging of mouse brain. eLife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.17681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilouz R., Bubis J., Wu J., Yim Y.Y., Deal M.S., Kornev A.P., et al. Localization and quaternary structure of the PKA RIβ holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:12443–12448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209538109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Götz F., Roske Y., Schulz M.S., Autenrieth K., Bertinetti D., Faelber K., et al. AKAP18:PKA-RIIα structure reveals crucial anchor points for recognition of regulatory subunits of PKA. Biochem. J. 2016;473:1881–1894. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gold M.G., Fowler D.M., Means C.K., Pawson C.T., Stephany J.J., Langeberg L.K., et al. Engineering A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP)-selective regulatory subunits of protein kinase A (PKA) through structure-based phage selection. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:17111–17121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burgers P.P., Bruystens J., Burnley R.J., Nikolaev V.O., Keshwani M., Wu J., et al. Structure of smAKAP and its regulation by PKA-mediated phosphorylation. FEBS J. 2016;283:2132–2148. doi: 10.1111/febs.13726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burgers P.P., Ma Y., Margarucci L., Mackey M., van der Heyden M.A., Ellisman M., et al. A small novel A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) that localizes specifically protein kinase A-regulatory subunit I (PKA-RI) to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:43789–43797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burgers P.P., van der Heyden M.A., Kok B., Heck A.J., Scholten A. A systematic evaluation of protein kinase A-A-kinase anchoring protein interaction motifs. Biochemistry. 2015;54:11–21. doi: 10.1021/bi500721a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minh B.Q., Schmidt H.A., Chernomor O., Schrempf D., Woodhams M.D., von Haeseler A., et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kozlov A.M., Darriba D., Flouri T., Morel B., Stamatakis A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bregman D.B., Bhattacharyya N., Rubin C.S. High affinity binding protein for the regulatory subunit of cAMP- dependent protein kinase II-B. Cloning, characterization, and expression of cDNAs for rat brain P150. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4648–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nygren P.J., Mehta S., Schweppe D.K., Langeberg L.K., Whiting J.L., Weisbrod C.R., et al. Intrinsic disorder within AKAP79 fine-tunes anchored phosphatase activity toward substrates and drug sensitivity. Elife. 2017;6:e30872. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giakoumakis N.N., Rapsomaniki M.A., Lygerou Z. In: Light Microscopy: Methods and Protocols. Markaki Y., Harz H., editors. Springer; New York, NY: 2017. Analysis of protein kinetics using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) pp. 243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tunquist B.J., Hoshi N., Guire E.S., Zhang F., Mullendorff K., Langeberg L.K., et al. Loss of AKAP150 perturbs distinct neuronal processes in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:12557–12562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805922105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bregman D.B., Bhattacharyya N., Rubin C.S. High affinity binding protein for the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase II-B: cloning, characterization, and expression of cDNAs for rat brain P150. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4648–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarkar D., Erlichman J., Rubin C.S. Identification of a calmodulin-binding protein that co-purifies with the regulatory subunit of brain protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:9840–9846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carr D.W., Stofko-Hahn R.E., Fraser I.D., Cone R.D., Scott J.D. Localization of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase to the postsynaptic densities by A-kinase anchoring proteins. Characterization of AKAP 79. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16816–16823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]