Abstract

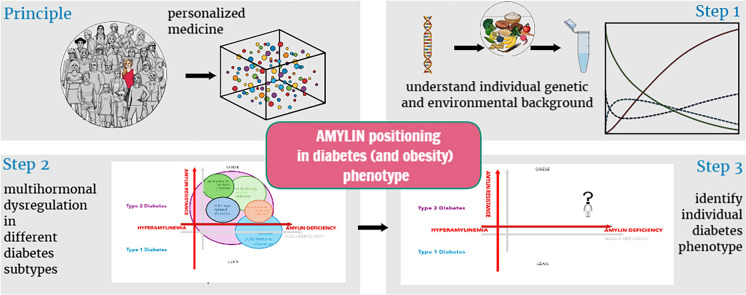

Precision diabetology is increasingly becoming diabetes phenotype-driven, whereby the specific hormonal imbalances involved are taken into consideration. Concomitantly, body weight-favorable therapeutic approaches are being dictated by the obesity pandemic, which extends to all diabetes subpopulations. Amylin, an anorexic neuroendocrine hormone co-secreted with insulin, is deficient in individuals with diabetes and plays an important role in postprandial glucose homeostasis, with additional potential cardiovascular and neuroprotective functions. Its actions include suppressing glucagon secretion, delaying gastric emptying, increasing energy expenditure and promoting satiety. While amylin holds promise as a therapeutic agent, its translation into clinical practice is hampered by complex receptor biology, the limitations of animal models, its amyloidogenic properties and pharmacokinetic challenges. In individuals with advanced β-cell dysfunction, supplementing insulin therapy with pramlintide, the first and currently only approved injectable short-acting selective analog of amylin, has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing both postprandial and overall glycemic control in both type 2 diabetes (T2D) and type 1 diabetes (T1D) without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia or weight gain. Current research focuses on several key strategies, from enhancing amylin stability by attaching polyethylene glycol or carbohydrate molecules to amylin, to developing oral amylin formulations to improve patients’ convenience, as well as developing various combination therapies to enhance weight loss and glucose regulation by targeting multiple receptors in metabolic pathways. The novel synergistically acting glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist combined with the amylin agonist, CagriSema, shows promising results in both glucose regulation and weight management. As such, amylin agonists (combined with other members of the incretin class) could represent the elusive drug candidate to address the multi-hormonal dysregulations of diabetes subtypes and qualify as a precision medicine approach that surpasses the long overdue division into T1DM and T2DM. Further development of amylin-based therapies or delivery systems is crucial to fully unlock the therapeutic potential of this intriguing hormone.

Graphical abstract available for this article.

Keywords: Adjunct non-insulin-based therapies, Amylin, Amylin receptor agonists, Cagrisema, Incretin, Obesity, Postprandial hyperglycemia, Pramlintide, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Plain Language Summary

Diabetes is a chronic disease with many faces, and persons affected by diabetes are continuously confronted with challenges, with injecting insulin and fighting obesity being the most recent. Current research is focused on designing drug candidates that would simultaneously address different mechanisms of high glucose in an individual and contribute to satiation, body weight control and patient convenience. Amylin is a hormone that is, similar to insulin, secreted by the pancreas. Its clinical use is currently limited to a single product, known as pramlintide, which is approved as an adjunct therapy in persons with insulin-treated diabetes. While the use of amylin is efficient, patients have to inject it with each meal and in a separate injection from insulin. Consequently, improving amylin-based medicines focuses on enabling longer action, resulting in weekly use, possibly even oral use and, most importantly, combining the functions of more than one hormone known for being involved in glucose control and the promotion of satiety. Similarly to other medicines primarily used in persons with diabetes, amylin-based medicines might eventually be used to address different diseases of the metabolic spectrum, namely obesity and its complications.

Graphical Abstract

Key Summary Points

| The precision medicine approach requires personalized tailoring of treatment of an individual’s metabolic disturbances associated with diabetes and concurrent tackling of associated obesity. |

| Amylin receptors are complex structures present in the brain regions involved in satiety regulation and reward pathways; it is also found in the liver, gastric fundus, duodenum, kidney and bone, among others. |

| Amylin’s glucagon-static action reduces postprandial hyperglycemia. |

| Amylin plays an anorectic role and benefits energy metabolism, opening exciting possibilities for its use in addressing obesity and its complications or comorbidities. |

| Formulation of a perfect amylin-based drug is challenging, with current efforts focused on enhancing pharmacokinetics and improving patients’ convenience. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.28625306.

Introduction

Diabetes care is evolving towards the personalized medicine approach, moving beyond the basic assumption that diabetes is solely a consequence of β-cell dysfunction in a single hormone, insulin [1–4]. Glucose levels in healthy individuals are maintained by a complex interplay of various hormones, including insulin, glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, catecholamines, incretins, and amylin [5–7]. Achieving optimal long-term glycemic control as well as reducing the risk of cardiovascular (CV), neurodegenerative diseases, and mortality continues to be a challenge for a significant portion of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and type 1 diabetes (T1DM) worldwide [8–14]. This challenge is partly due to the increasing obesity prevalence and its impact on T2DM as well as T1DM pathophysiology and prognosis [15–21].

Obesity and T2DM are both characterized by insulin resistance (IR), proinflammatory cytokines, mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress as well as dysfunctional fatty acid metabolism [22]. The increasing prevalence of obesity in T1DM is concurrently a consequence of a combination of variables, including genetic susceptibility to insulin resistance, the influence of an obesogenic environment, a sedentary lifestyle, as well as the impact of numerous biological, psychological and social stressors [18, 23]. Additionally, obesity and IR both contribute to β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis, mechanistically explained by glucotoxicity and increased immunogenicity (the accelerator hypothesis) or by β-cell exhaustion due to increased metabolic demand (the overload hypothesis) [23]. In addition to IR and β-cell dysfunction, obesity in T1DM is concomitantly associated with chronic inflammation, central adiposity and dyslipidemia [18]. To advance personalized treatment strategies, it is critical to improve current understanding of the overlapping pathophysiology as well as the heterogeneity of obesity and diabetes, including their multi-hormonal dysregulation and inter-individual differences [24, 25]. The identification of dysregulated incretin secretion and action in both obesity and diabetes led to the revolutionary discovery of incretin-based drugs, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (RAs) and dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs [24–28].

Amylin, a neuroendocrine anorexigenic polypeptide hormone, with its multi-faceted effects in glucose regulation, weight management and potential CV and neuroprotective functions, represents an attractive new therapeutic target, albeit not without challenges and limitations [29]. The comprehensive review presented here explores the multi-faceted aspects of amylin, encompassing its diverse physiological functions, receptor interactions and challenges in clinical translation. It focuses on amylin’s well-known impact on glucose and weight control. We also present an in-depth analysis of promising treatment approaches. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Amylin

Introduction to Amylin and its Functions

Amylin, a neuroendocrine hormone encoded on human chromosome 12 (p12.1), is produced and stored in the pancreatic β-cells, alongside insulin [29–32]. Amylin is co-secreted with insulin in response to nutrient stimuli, such as glucose, arginine and fatty acids. Similarly to insulin, amylin has similar secretion patterns with low fasting levels and marked increases following meals [29, 30]. Insulin-to-amylin co-secretion has a molar ratio that is consistently maintained at approximately 10:1 to 100:1 [29, 30, 33]. While predominantly produced and secreted by the pancreas, amylin is additionally synthesized in lower quantities within enteroendocrine cells, pulmonary tissue and the central nervous system (CNS) [29]. Amylin metabolizes through a combination of renal excretion and proteolytic degradation [29]. The circulating half-life of endogenous amylin is short, with human studies indicating a half-life of < 20 min [29].

Amylin is a 37-amino acid peptide that was first discovered in the late 1980s, by Cooper and colleagues, as being a major component of amyloid deposits in pancreatic islets. These amyloid deposits are often found in T2DM and contribute to the progressive loss of pancreatic β-cells [30, 34, 35]. As amylin was observed to have the proclivity to form amyloid fibrils in the pancreatic islets, it became known as islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) [30, 36, 37]. The fibrillating amyloid deposits that contribute to β-cell death, considered a hallmark of T2DM, became one of the two main focuses of amylin research. This focus on amylin as the β-cell assassin could lead to new targeted therapeutic strategies for islet amyloidosis in T2DM [29, 30].

Later in the 1990s, the second and now prevalent research focus was placed on amylin, since it was found to be involved in the regulation of key metabolic functions, such as glucose and energy metabolism, gastric emptying and satiety induction [38, 39].

The Complex Structure of Amylin Receptors

Amylin functions as both a hormone and a neuropeptide, exerting its biological effects by activating amylin receptors (AMYRs) [33, 40–43]. AMYRs are complex structures belonging to the family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) [40]. Each receptor is composed of the calcitonin (CT) receptor (CTR), which is a classic GPCR, combined with one of three receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs), AMY1R, AMY2R and AMY3R [29, 33, 40, 44]. The pairing of the CTR with different RAMPs generates distinct AMYR subtypes with different pharmacological profiles and signaling properties [33, 44, 45]. The close relationship between AMYRs and CTRs complicates the understanding of their contributions to different physiological processes [33, 40, 43, 44]. AMYRs are widely distributed across the CNS and peripheral tissues [46] and are found in regions involved in satiety regulation and reward pathways, including the hypothalamus and distinct nuclei within the dorsal-vagal complex in the hindbrain, such as the area postrema (AP), nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve [46, 47]. Additionally, AMYRs are found in areas connected to cognition, such as the hippocampus and cortex [46, 48]. Beyond the CNS, AMYRs are present in multiple peripheral tissues, including the lung, spleen, liver, gastric fundus, duodenum, jejunum, kidney, testes and bone [46].

Amylin in Glucose Regulation

The Physiological Role of Amylin in Glucose Regulation

Under physiological conditions, there is an increase in insulin, amylin and incretin secretion following caloric intake [49]. Insulin increases glucose consumption in the peripheral tissues, insulin and amylin suppress glucagon secretion and hepatic glucose production, while amylin and incretins delay gastric emptying [49].

Amylin plays a critical role in regulating postprandial glucose [29]. While supraphysiological insulin concentrations can achieve glucagon suppression, amylin potently suppresses meal-induced glucagon secretion at physiologically relevant concentrations [29]. By inhibiting glucagon secretion postprandially, amylin suppresses glucagon-stimulated hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, thereby reducing postprandial endogenous glucose production or glucose spikes [50, 51]. This glucagon-static action seems to be centrally mediated and is attenuated during low glucose values, ensuring proper contra-regulatory glucagon response in case of hypoglycemia [29, 32].

Through its direct action on AMYRs in the AP, amylin correspondingly slows gastric emptying, which delays the inflow of nutrients into the small intestine and slows the absorption of glucose into the circulation [32, 51, 52]. Additionally, gastric-wall distension generates an anorectic signal transmitted to the nucleus of the solitary tract via gastric vagal and splanchnic afferents, which impacts glucose homeostasis [38]. Since this anorectic action depends on the glycemic state, it is reversed during hypoglycemia [32, 53].

The Pathophysiological Role of Amylin in Diabetes

Individuals with T1DM experience an absolute deficiency of both insulin and amylin; similarly, those with T2DM exhibit a relative deficiency of both hormones, including a diminished response to food intake [29, 30, 32, 54]. Subjects with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) exhibit various genetic mutations; for example, individuals with a mutation in the hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-4 alpha gene (MODY1) are characterized by diminished insulin and glucagon secretory responses [55, 56]. Furthermore, the HNF-4 alpha mutation in MODY1 confers a generalized defect in islet cell function involving α- and β-cell impairment with proportional deficits in insulin and amylin secretion [55, 56]. In diabetes, decreased insulin signaling to the α-cells leads to high glucagon secretion, while amylin and GLP-1 deficiency results in an acceleration of gastric emptying and glucose absorption in parallel with secondary postprandial glucose peaks [32, 49, 57]. Replicating the precise and dynamic insulin secretion patterns of healthy individuals, particularly in the postprandial period, remains elusive as subcutaneous insulin delivery fails to achieve the hepatic insulin concentrations necessary for the effective suppression of endogenous glucose production [1, 58–60]. Furthermore, attempts to mitigate postprandial hyperglycemia by increasing insulin doses can lead to peripheral hyperinsulinemia, increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and potentially contributing to weight gain [1, 58–60]. Dysregulation of glucagon secretion, a hallmark of both T1DM and T2DM, further complicates glycemic control as postprandial hyperglucagonemia exacerbates hepatic glucose output, counteracting the effects of exogenous insulin [1, 58–60]. Finally, the accelerated rate of gastric emptying, which is a critical determinant of postprandial glucose excursions, can overwhelm the capacity of exogenous insulin to manage the rapid influx of glucose into the circulation [61, 62].

Figure 1 presents insulin and amylin dysregulation in different subtypes of diabetes.

Fig. 1.

Position of amylin in diabetes: multi-hormonal dysregulation in different subtypes of diabetes, informing personalized therapeutic avenues according to diabetes phenotype. Achieving near-normoglycemia warrants a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay of amylin deficiency, insulin deficiency or resistance and glucagon suppression. Personalized therapeutic approaches must address broader hormonal and gastrointestinal dysregulation characteristic of glucoregulation and accompanying metabolic disorders, namely obesity

Amylin in Weight Management

The Physiological Role of Amylin in Weight Regulation

Amylin is physiologically involved in the control of eating, energy expenditure and body weight [29]. It plays a key role in regulating satiety as it affects both the homeostatic and hedonic aspects of eating [63]. Amylin primarily binds to receptors in the AP, initiating signals that are relayed to the NTS and lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBN) [47, 64]. These signals are further transmitted to the amygdala, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and various hypothalamic nuclei, all of which are areas with critical roles in the regulation of energy metabolism [47, 64]. Additionally, amylin binds to receptors in the arcuate nucleus, possibly activating the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons which have a key role in satiety induction and reduction of food intake [47]. Amylin promotes meal-ending satiation and dose-dependently reduces meal size and length, which leads to a decrease in overall caloric intake [38, 51, 65, 66]. Amylin similarly modulates impulsive food-directed behavior and decreases the consumption of palatable food by affecting the activity of the mesocorticolimbic pathway [67, 68]. Via enhanced gastric distension amylin stimulates the perception of fullness, promoting earlier meal termination [69, 70].

In addition to being an acute satiation signal, amylin is considered to be an adiposity signal involved in the homeostatic regulation of body weight [29, 71]. Adiposity signals are secreted by the adipose tissue (leptin) or the pancreas (insulin and amylin) in proportion to body adiposity to enhance satiety signals, reduce energy intake and regulate body weight via central mechanisms [29, 54, 71]. Consistent with the role of adiposity signal, chronic central and peripheral amylin administration reduces weight gain and adiposity regardless of initial body weight, and the use of AMYR antagonists increases body adiposity [29, 54, 71].

In addition to a reduction in energy intake, amylin has favorable actions on energy expenditure [72]. Preclinical studies show that amylin increases energy expenditure independently of the AP, possibly by increasing the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, particularly in the efferents that regulate brown adipose tissue [64, 73, 74].

The Pathophysiological Role of Amylin in Obesity

Plasma amylin levels in individuals with obesity are elevated compared to those in lean controls [29], in both diet-induced and genetic obesity [75, 76]. However, despite increased amylin levels in obesity, amylin sensitivity is not reduced as exogenous administration of amylin leads to reduced appetite in individuals with obesity [29, 45]. Preclinical as well as clinical studies have demonstrated that the coadministration of amylin with leptin increases leptin sensitivity in obesity [77]. Furthermore, obesity is characterized by IR, accelerated gastric emptying, elevated plasma glucagon and blunted or even reversed meal-induced glucagon suppression [78, 79], all of which can be influenced by amylin.

Amylin-induced weight loss presents with certain differences compared to calorie restriction-induced weight loss [80]. Amylin-induced energy intake reduction and weight loss lead to a reduction in fat mass with relative preservation of lean mass, resulting in an improved fat-to-lean mass ratio, while calorie restriction-induced weight loss results in reductions in both fat and lean mass [80]. Lastly, both central and peripheral administration of amylin increases energy expenditure or prevents the compensatory decrease in energy expenditure expected after calorie reduction-induced weight loss [72].

Beyond Glucose Regulation and Weight Management: Amylin’s Broader Action

Amylin has been implicated in blood pressure regulation, with contradictory results from preclinical and clinical studies [29, 81]. It affects the CV system, mostly by activating calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptors within the vasculature. In rodents, amylin was found to induce potent vasodilation with a decrease in blood pressure; however, in humans this activation of CGRP receptors would require supratherapeutic doses of amylin analogs [29]. Results from other studies suggest that amylin activates the renin-angiotensin system and increases plasma renin activity, potentially contributing to hypertension [29, 81]. Amylin has also been shown to impair endothelium-dependent relaxation responses in rat blood vessels, indicating a possible mechanism for amylin-induced hypertension through endothelial dysfunction [82]. While short-term amylin infusion may not alter blood pressure in humans, long-term effects and interactions with other regulatory systems remain unclear [29, 81, 82]. No data are available on the contribution of the potential indirect effect of amylin on blood pressure via weight reduction.

Amylin also appears to play a role in lipid metabolism by potentially modulating chylomicron uptake [83]. This effect may be mediated through direct regulation of lipoprotein receptors or indirectly via modulation of insulin activity [83]. Amylin’s actions on muscle include opposing glycogen synthesis and activating glycogenolysis and glycolysis, which may indirectly affect liver metabolism [29, 84]. Amylin is a modulator of bone remodeling as rodent studies show that it inhibits bone resorption [85–87], and may additionally stimulate bone formation [86, 87].

Amylin has been implicated in neurocognition [48]. Plasma amylin levels are reduced in patients with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, and treatment with human amylin or its synthetic analog pramlintide has been shown to reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, reduce Aβ plaque burden, modulate tau phosphorylation and improve cognitive function in animal models with Alzheimer’s disease [48, 88–91]. Additionally, preclinical studies have associated amylin agonism with antidepressant, anxiolytic and cognitive-enhancing properties [92]. Lastly, amylin seems to be involved in nociception modulation and pain signaling, as exogenous amylin has been shown to alleviate nociceptive behavior when administered before noxious stimuli [93–95].

Figure 2 illustrates the organ-specific actions of amylin.

Fig. 2.

Organ-specific physiological actions of amylin. Amylin, a neuroendocrine hormone that is co-secreted with insulin, plays a role in glucose regulation, with further potential cardiovascular and neuroprotective functions in addition to a well-characterized influence on appetite and weight control. ↑ increase, ↓ decrease, CNS central nervous system

Advancements, Challenges and Future Directions in Amylin-Based Therapies

As amylin plays a critical role in glucose regulation and energy balance, it is a promising target for therapeutic intervention. However, the clinical application of native amylin is limited by its short half-life, structural instability, and propensity to form amyloid aggregates [29, 33, 96, 97]. To address these challenges, several synthetic amylin analogs have been developed [47, 98] by employing different alterations of the amylin molecule, ranging from enhancing amylin stability and developing oral amylin formulations to the development of various combination therapies to enhance weight loss and glucose regulation through targeting multiple receptors in metabolic pathways [29, 33, 96, 97]. While using amylin analogs with extended half-life and non-aggregating properties showed promising results in animal models, applying these findings to human clinical trials has proven difficult [98]. Furthermore, the ability of amylin receptors to interact with other peptides, such as CT and CGRP, adds another layer of complexity to their signaling and functional roles [29, 30, 33]. Selective AMYR agonists and dual AMYR/CTR agonists (DACRAs) are being developed. However, it is unclear whether DACRAs based on amylin-template peptides versus CA-template peptides activate target receptors by similar or distinct molecular mechanisms [29, 30, 33]. This understanding has significant implications for the design and development of future DACRAs with tailored activity profiles [98].

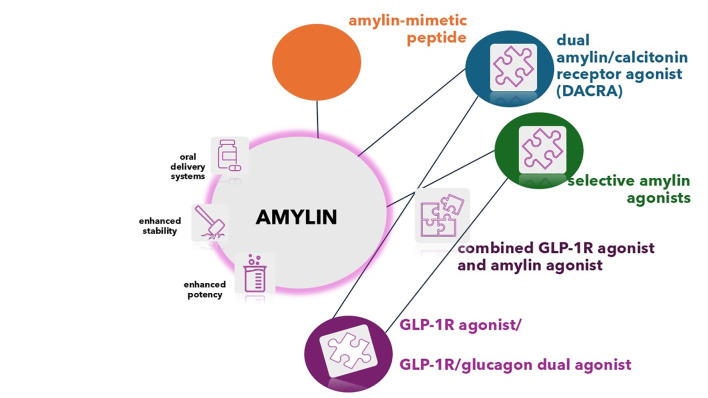

Figure 3 summarizes present and novel approaches to amylin therapy development.

Fig. 3.

Amylin-based therapies—present and future. Diverse strategies are being pursued to deliver enhanced stability, potency and patient convenience, resulting in oral or weekly subcutaneous formulations. While amylin is the core molecule of interest, synthetic peptides—amylin mimetics are represented by the currently approved amylin receptor agonist (RA) pramlintide. Selective amylin agonists are designed to provide for a longer duration of action and less frequent dosing. Similarly, the non-selective receptor agonists termed dual amylin/calcitonin receptor agonists (DACRAs) achieve their long-acting dual activity through conformational flexibility. Furthermore, cagrilintide, a nonselective agonist of the entire calcitonin receptor family, exhibits a distinct pharmacological profile compared to that of other DACRAs, while being administered once weekly. The combination of amylin RA with other incretin-based agents, such as the GLP-1/glucagon dual RA is also being investigated, with the aim to achieve enhanced weight loss and end-organ protection via triple mechanism effect. GLP-1R Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor

Current research focuses on several key strategies exemplified by enhancing amylin stability by attaching polyethylene glycol or carbohydrate molecules to amylin [29, 33, 96], developing oral amylin formulations [60, 99] or even developing inhibitors of amylin aggregation to prevent islet amyloid formation [100]. The most frequently employed principle is the development of various multi-receptor agonists that are designed to enhance weight loss and glucose regulation by targeting different receptors and metabolic pathways, as exemplified by CagriSema, which has progressed the furthest in phase 3 clinical trials [29, 33, 96, 97]. Since similarities in the peptide sequences of incretin class members (GLP-1, GIP and glucagon) enable the development of unimolecular multi-receptor activating agonists, various pharmaceutical companies are bustling with double- or triple-incretin combinations in their respectively therapeutic pipelines [24–28]. There is mounting evidence that early intervention with incretin-based therapy across the wide array of cardio-renal-hepatic-metabolic diseases yields improvements in cardio-metabolic health, which is anticipated to translate into reduced morbidity and mortality from these conditions, as well as in complications like obesity-related malignancies and neurocognitive disorders [24–28]. Such a multi-hormonal and simultaneously personalized approach to hyperglycemia, whether it is T1DM, T2DM or MODY, when accompanied by obesity opens the window of opportunity to position the amylin RA early in the therapeutic process, addressing key aspects in diabesity or double diabetes.

In the following sections we detail the evolution of amylin-based therapies, outlining their key properties, strengths, limitations and clinical significance.

Pramlintide

Pramlintide (Pramlintide acetate; Symlin), a non-aggregating amylin analog, is a chimeric peptide composed of the human amylin primary sequence with three proline substitutions from the rat amylin primary sequence, thereby functioning as a selective amylin RA [33]. With a half-life of 20–45 min, it requires subcutaneous (SC) administration with every meal. Administration of pramlintide in patients with obesity has produced sustained reductions in overall daily caloric intake, individual meal sizes and the frequency of binge eating episodes [101]. In one study, pramlintide use in conjunction with lifestyle intervention over a study period of 12 months resulted in placebo-corrected weight loss of up to 7.9% or 6.1 ± 2.1 kg when the participants received a dose of 120 mcg 3 times a day (t.i.d.) and of 7.2 ± 2.3 kg when the dose was 360 mcg 2 times a day (b.i.d.) [102]. Pramlintide is the first synthetic amylin analog approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for both T1DM and T2DM that requires treatment with mealtime insulin [103]. Pramlintide lowers postprandial glucose with minimal effects on fasting glucose, providing a glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction of 0.2–0.4% in T1DM and 0.4–0.6% in T1DM [103]. In contrast to insulin, which is commonly titrated to achieve desired clinical outcomes, pramlintide is typically administered using a fixed, mealtime-only dosing regimen [104]. However, in contrast to insulin, which needs a neutral pH environment, pramlintide, in order to maintain solubility, needs to be formulated at an acidic pH of 4; this pH incompatibility presents a significant obstacle to combining pramlintide with insulin [105]. Consequently, patients are required to administer two injections before meals, which can hinder patient’s treatment adherence [105]. Stanford University researchers have developed a novel approach to combining insulin (Insulin Lispro) and pramlintide (Symlin) into a single injection by designing a polyethylene glycol-based molecular wrapper to encapsulate and protect both the insulin and pramlintide molecules; this system has demonstrated efficacy in animal models [106]. Pramlintide can be included as an adjunctive drug within artificial pancreas systems for T1DM and dual-hormone closed-loop systems incorporating pramlintide alongside insulin, or in conjunction with glucagon, with the aim to closely replicate endogenous pancreatic hormonal secretion; this approach may optimize glycemic control by attenuating postprandial glucose as well as reducing the risk of exercise-induced hypoglycemia [107]. Short randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in persons with T1DM have shown that insulin-and-pramlintide dual-hormone closed-loop systems achieved a time in range > 70% [108–110].

Davalintide (AC2307)

Davalintide (AC2307) is a second-generation amylin-mimetic peptide intended for SC use. It has demonstrated enhanced pharmacological efficacy compared to native amylin for reducing food intake and body weight in rodents [111]. As davalintide is a chimera of the primary sequences of rat amylin and salmon CT [33], it binds to the AMYR, CTR and CT-gene-related receptors and exhibits a longer duration of action [111], qualifying as a non-selective amylin RA, related to, but distinct from DACRAs. The use of davalintide in preclinical studies showed dose-dependent, durable and fat-specific weight loss with a maintained metabolic rate [111]. However, despite an extended half-life and promising weight loss seen in preclinical studies, davalintinde failed to surpass pramlintide in clinical trials [40], and research and development on this peptide has been discontinued.

Cagrilintide (AM833)

Cagrilintide is a long-acting amylin analog designed for once-weekly (OW) SC administration (based on the structure of natural amylin), developed by Novo Nordisk [112]. Cagrilintide efficacy for weight management in overweight and obesity was analyzed in phase 2 randomized, multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding clinical trial [113]. In this trial, treatment with cagrilintide resulted in significant weight loss compared to placebo, with greater reductions observed at all used cagrilintide doses (0.3–4.5 mg; 6.0–10.8% weight loss) compared to placebo (3.0% weight loss [3.3 kg]; estimated treatment difference [ETD] range 3.0–7.8%; p < 0.001) [113]. Furthermore, cagrilintide at a dose of 4.5 mg OW SC resulted in superior weight loss compared to liraglutide 3 mg daily [113]. Treatment with cagrilintide exhibited a favorable safety profile, with gastrointestinal disturbances and injection-site reactions being the most frequent adverse events [113].

Long-Acting Amylin Agonist AZD6234

AZD6234 is a novel long-acting selective AMY3R agonist developed by AstraZeneca for SC administration, and is currently in phase 2 testing [114]. Preliminary results indicate that AZD6234 demonstrates promising efficacy for body fat-selective weight loss [115]. The combination of AZD6234 with other incretin-based agents, such as the GLP-1/glucagon dual agonist AZD9550, is also being investigated in a phase 1 trial, with the planning for a phase 2 trial underway. The aims of these trials is to achieve fat-selective weight loss, improved body composition and end-organ protection via a triple mechanism effect in people living with obesity [114].

Petrelintide (ZP8396)

Petrelintide (ZP8396) is a novel SC-administered, long-acting amylin analog, developed by Zealand Pharma (Søborg, Denmark), a peptide drug discovery and development company, which is currently in early-stage clinical trials (phase 1 clinical trials: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT05511025, NCT05096598 and NCT05613387) [116]. Petrelintide, in which acylation has been used to achieve a longer half-life, has chemical and physical stability at neutral pH, which minimizes fibril formation and allows co-formulation with other peptides [116]. Petrelintide exhibits a potent balanced agonistic effect on both the AMYR and CTR—which precludes this molecule from being included in the DACRA class [116]. The phase 1b, 16-week, multiple-dose ascending trial (NCT05613387) showed a mean body weight reduction of 4.8%, 8.6% and 8.3% at OW doses of up to 2.4 mg, 4.8 mg and 9.0 mg, respectively [116]. Petrelintide treatment was well-tolerated with no severe adverse events. In late 2024, Zealand Pharma initiated a phase 2b randomized dose-finding obesity and T2DM + obesity clinical trial (ZUPREME-1 and ZUPREME-2) which will evaluate petrelintide’s efficacy and safety in individuals with obesity in a larger population (N = 480) [116]. The company announced that it plans to initiate a phase 1 combination trial with GLP-1 RA in 2025 [116].

Long-Acting Amylin Agonist GUB014295

Gubra A/S (Hørsholm, Denmark), a biotech company specialized in pre-clinical contract research, initiated a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT06144684) to investigate the safety, tolerability and pharmacological properties of GUB014295 (GUBamy), a long-acting OW SC amylin agonist, in healthy volunteers [117]. GUB014295 is an RA that activates amylin and CTR, thereby being classified as a DACRA [117]. The company states that interim results from the ongoing phase 1b study assessing multiple ascending doses of GUBamy are expected during the first half of 2025 [117].

Combinations of Treatment Methods

As GLP-1 RA and amylin analog-induced weight loss arise from both distinct and overlapping mechanisms, the combination of GLP-1 RA and amylin RA has been shown to produce a synergistic effect [118]. Of note, similarly to combination therapy formulations with insulin, amylin RA needs to exhibit greater stability at pH 7.4 in order to provide the conditions to co-formulate with GLP-1 analogs [33, 41]. In the case of KBP-089, a dual amylin and CTR agonist, the additivity of DACRAs and GLP-1 RA in improved insulin sensitivity and body weight reduction was demonstrated in the rat–animal model [119, 120].

CagriSema

The combination of OW SC GLP-1 RA semaglutide and non-selective amylin RA cagrilintide (AM833) has been shown to demonstrate an additive effect on glucose regulation and weight loss as both GLP-1 RA and amylin analogs act on glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying and mediate weight loss by acting through both distinct and overlapping neural satiety and reward pathways [47, 121]. This novel dual-agonist approach surpassed the efficacy of monotherapy while maintaining a favorable cost–benefit and safety profile [122].

In a phase 1b placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, participants with overweight or obesity received OW SC cagrilintide at various doses or placebo, in conjunction with semaglutide 2.4 mg over 20 weeks [123]. Semaglutide combined with cagrilintide (1.2 mg and 2.4 mg) resulted in significantly greater weight loss (15.7% and 17.1%, respectively) at week 20 compared to semaglutide combined with placebo (9.8%) [123]. Gastrointestinal events and injection-site reactions were the most commonly reported adverse effects [123].

A phase 2 clinical trial investigated the safety and efficacy of a fixed-dose combination of cagrilintide 2.4 mg and semaglutide 2.4 mg (CagriSema; Novo Nordisk A/G, Bagsværd, Denmark), administered OW SC over 32 weeks, in 92 overweight individuals with T2DM [124]. This study compared the safety and efficacy of this cagrilintide/semaglutide combination to those of its individual components. Treatment with CagriSema 2.4 mg OW SC resulted in an average 15.6% reduction in body weight, which was superior to the weight loss observed with cagrilintide 2.4 mg (8.1%) alone or semaglutide 2.4 mg (5.1%) alone [124]. Moreover, after 32 weeks of treatment, CagriSema demonstrated a numerically greater improvement in glycemic control, achieving a 2.2%-point reduction in HbA1c levels, compared to 0.9%-points with cagrilintide and 1.8%-points with semaglutide monotherapy [124]. Time in range (TIR) increased from 56.9% at baseline to 88.9%, 76.2% and 71.7% with CagriSema, semaglutide and cagrilintide, respectively [124]. Additionally, CagriSema treatment resulted in a reduction of systolic blood pressure by 13 mmHg [124]. CagriSema was generally well-tolerated, with mild to moderate gastrointestinal adverse events, primarily nausea and vomiting [124].

REDEFINE is a phase 3 clinical program that will evaluate the efficacy and safety of CagriSema in patients with overweight or obesity using CagriSema for a period of 68 weeks in a larger patient population. REDEFINE-1 (NCT05567796) is the first phase 3 clinical trial from this program to be completed [125]. REDEFINE-1 evaluated the efficacy and safety of CagriSema (2.4/2.4 mg) in patients with overweight or obesity with one or more comorbidities and without T2DM. The trial lasted 68 weeks and included 3417 individuals who were randomized to either CagriSema, its individual components or placebo [125]. The results showed that patients with a mean baseline body weight of 106.9 kg who were treated with CagriSema (2.4/2.4 mg) achieved 22.7% weight loss after 68 weeks, compared to 11.8% of those treated with cagrilintide 2.4 mg monotherapy and 16.1% of those treated with semaglutide 2.4 mg monotherapy, and to 2.3% of those receiving only the placebo [125]. Additionally, a weight loss of more than 25% was achieved in 40.4% of patients receiving CagriSema, compared to 16.2% of patients receiving semaglutide 2.4 mg, 6% of patients receiving cagrilintide 2.4 mg and 0.9% of patients receiving placebo. Of interest, in the study design, the company states that included individuals had a flexible dosing protocol [125], which could have accounted for not meeting the desired ≥ 25% body weight reduction target. Treatment was generally well tolerated and safe; the drug was discontinued in 3.6% of the persons in the CagriSema arm compared to 1.3% in the comparators' arms, and observed gastrointestinal adverse events per patient per year were 2.8 with CagriSema versus 2.6 with semaglutide 2.4 mg monotherapy [125].

The REDEFINE-2 clinical trial (NCT05394519) will evaluate the safety and efficacy of CagriSema over 68 weeks in 1200 adults with T2DM and overweight or obesity. The CV safety of OW CagriSema in 7000 patients with overweight or obesity and established CV disease will be evaluated in the REDEFINE-3 clinical trial (NCT05669755). Lastly, the REDEFINE-4 clinical trial (NCT06131437) will evaluate the efficacy and safety of CagriSema compared to tirzepatide over 72 weeks in 800 adults with obesity [125].

Amycretin (NNC0487-0111)

Novo Nordisk is currently conducting phase 1 clinical trials (NCT05369390, NCT06049329 and NCT06064006) to evaluate amycretin (NNC0487-0111), an oral and/or SC formulation combining GLP-1 RA and amylin peptides [126]. Preliminary findings from the NCT05369390 trial suggest that oral amycretin may offer superior efficacy compared to OW semaglutide for the treatment of obesity [127]. Data indicate that participants receiving oral amycretin achieved an average weight loss of 13.1% after 12 weeks, which is substantially greater than the 1.1% weight loss observed in the placebo group [128]. This result surpasses the 6% weight loss seen in semaglutide over a similar time frame [127]. In late January 2025, according to an announcement by the company, the SC formulation of amycretin achieved promising results in chronic weight management. In the phase 1b/2a clinical trial with amycretin, an unimolecular GLP-1, and amylin RA intended for OW SC use, the 125 individuals with overweight or obesity included in the study achieved an estimated body weight loss of 9.7% on 1.25 mg (20 weeks), 16.2% on 5 mg (28 weeks) and 22.0% on 20 mg following 36 weeks of treatment [127].

Figure 4 provides an overview of amylin-based therapies in the therapeutic pipeline.

Fig. 4.

Amylin-based therapies in the pipeline. Pramlintide (trade name Symlin [pramlintide acetate]) injection is approved as an adjunct treatment in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who use mealtime insulin and have not achieved desired glycemic control despite optimal insulin therapy. Further product candidates (amylin receptor agonists in development) are listed according to their corresponding status in Clinical Trials databases and companies’ pipelines. GLP-1 Glucagon-like peptide-1

Conclusions

Amylin, a neuroendocrine hormone co-secreted with insulin, is deficient in individuals with diabetes and plays an important role in postprandial glucose homeostasis by suppressing glucagon secretion and delaying gastric emptying. Amylin’s anorexic role is mediated by affecting both the homeostatic and hedonic aspects of eating. The novel synergistically acting GLP-1 RA + amylin RA formulation, CagriSema, shows promising results in both glucose control and chronic weight management. As such, the AMYR agonists (combined with other incretin class members) could represent the elusive drug candidate to address the multi-hormonal dysregulations of diabetes subtypes and qualify as a precision medicine approach that surpasses the long overdue division into T1DM and T2DM. Overcoming the complex receptor biology and pharmacokinetic challenges through further research and the development of novel amylin RA or delivery systems is crucial to fully unlocking the therapeutic potential of this intriguing hormone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Emir Muzurović, Mojca Jensterle and Špela Volčanšek. Writing–original draft preparation: Špela Volčanšek and Andrijana Koceva. Writing–review, and editing: Mojca Jensterle, Špela Volčanšek, Andrijana Koceva, Emir Muzurović and Andrej Janež. Visualization: Špela Volčanšek. Supervision: Emir Muzurović, Mojca Jensterle and Andrej Janež.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors have given lectures, received honoraria and research support and participated in conferences, advisory boards and clinical trials sponsored by many pharmaceutical companies. However, no pharmaceutical company played any role in the scientific content of the present article, which has been written independently and reflects only the opinions of the authors, without no imput from the pharmaceutical industry. The following conflict of interests are reported. Špela Volčanšek has received lecture honoraria from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Abbott, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. Andrijana Koceva reports receiving lecture honoraria from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic and Pfizer. Mojca Jensterle has received lecture honoraria from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, Novartis and Sanofi, and is an advisory board member of Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Amgen and Pfizer. Andrej Janež has served as a consultant and is on Speakers Bureaus for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Abbott, Novo Nordisk, Novartis and Swixx. Emir Muzurović has given lectures and participated in conferences and advisory boards sponsored by several pharmaceutical companies, including Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Medtronic and Servier.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Abel ED, Gloyn AL, Evans-Molina C, et al. Diabetes mellitus-progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic. Cell. 2024;187:3789–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redondo MJ, Hagopian WA, Oram R, et al. The clinical consequences of heterogeneity within and between different diabetes types. Diabetologia. 2020;63:2040–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie RD, Ma RCW, Franks PW, Nadeau KJ, Pearson ER, Redondo MJ. Understanding diabetes heterogeneity: key steps towards precision medicine in diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:848–60. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(23)00159-6/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Stidsen JV, Henriksen JE, Olsen MH.., et al. Pathophysiology-based phenotyping in type 2 diabetes: a clinical classification tool. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34:e3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker DJ, Holst JJ. The expanding incretin universe: from basic biology to clinical translation. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1765–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathieu C, Ahmadzai I. Incretins beyond type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1809–19. 10.1007/s00125-023-05980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aberer F, Pieber TR, Eckstein ML, Sourij H, Moser O. Glucose-lowering therapy beyond insulin in type 1 diabetes: a narrative review on existing evidence from randomized controlled trials and clinical perspective. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1180. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/14/6/1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Anson M, Zhao SS, Austin P, Ibarburu GH, Malik RA, Alam U. SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA therapy in type 1 diabetes and reno-vascular outcomes: a real-world study. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1869–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. Type 1 diabetes estimates in children and adults. https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/t1d-index-2022/. Accessed

- 10.Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A, et al. The management of Type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2021;44:2589–625. 10.2337/dci21-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong B, Kong G, Shankar K, et al. The global syndemic of metabolic diseases in the young adult population: a consortium of trends and projections from the Global Burden of Disease 2000–2019. Metabolism. 2023;141: 155402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fährmann ER, Adkins L, Loader CJ, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and coronary artery calcification during the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications (DCCT/EDIC) study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107:280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lind M, Svensson A-M, Kosiborod M, et al. Glycemic control and excess mortality in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1972–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coles B, Zaccardi F, Hvid C, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Cardiovascular events and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes and multimorbidity: a real-world study of patients followed for up to 19 years. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kueh MTW, Chew NWS, Al-Ozairi E, le Roux CW. The emergence of obesity in type 1 diabetes. Int J Obes. 2005;2024(48):289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:288–98. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-019-0176-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ansari S, Haboubi H, Haboubi N. Adult obesity complications: challenges and clinical impact. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018820934955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilarrasa N, San Jose P, Rubio MÁ, Lecube A. Obesity in patients with type 1 diabetes: links, risks and management challenges. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2021;14:2807–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeby M, Lane K. Treating obesity in type 1 diabetes mellitus—review of efficacy and safety. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2024;31:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janez A, Muzurovic E, Stoian AP, et al. Translating results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists into clinical practice: recommendations from a Eastern and Southern Europe diabetes expert group. Int J Cardiol. 2022;365:8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janez A, Muzurovic E, Bogdanski P, et al. Modern management of cardiometabolic continuum: from overweight/obesity to prediabetes/type 2 diabetes mellitus. Recommendations from the Eastern and Southern Europe diabetes and obesity expert group. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15:1865–92. 10.1007/s13300-024-01615-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckel RH, Kahn SE, Ferrannini E, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: what can be unified and what needs to be individualized? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1654–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielka W, Przezak A, Molęda P, Pius-Sadowska E, Machaliński B. Double diabetes—when type 1 diabetes meets type 2 diabetes: definition, pathogenesis and recognition. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan Q, Akindehin SE, Orsso CE, et al. Recent advances in incretin-based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13: 838410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chia CW, Egan JM. Incretins in obesity and diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1461:104–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muzurović EM, Volčanšek Š, Tomšić KZ, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide/glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of obesity/metabolic syndrome, prediabetes/diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-current evidence. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2022;27:10742484221146372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutgesell RM, Nogueiras R, Tschöp MH, Müller TD. Dual and triple incretin-based co-agonists: novel therapeutics for obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2024;15:1069–84. 10.1007/s13300-024-01566-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensterle M, Rizzo M, Janež A. Semaglutide in obesity: unmet needs in men. Diabetes Ther. 2023;14:461–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay DL, Chen S, Lutz TA, Parkes DG, Roth JD. Amylin: pharmacology, physiology, and clinical potential. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:564–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutz TA. Creating the amylin story. Appetite. 2022;172:105965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz TA. The interaction of amylin with other hormones in the control of eating. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hieronymus L, Griffin S. Role of amylin in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41:47S-56S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bower RL, Hay DL. Amylin structure–function relationships and receptor pharmacology: implications for amylin mimetic drug development. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:1883. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4882495/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Cooper GJ, Willis AC, Clark A, Turner RC, Sim RB, Reid KB. Purification and characterization of a peptide from amyloid-rich pancreases of type 2 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8628–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark A, Lewis CE, Willis AC, Cooper GJS, Morris JF, Reid KBM, et al. Islet amyloid formed from diabetes-associated peptide may be pathogenic in type-2 diabetes. Lancet. 1987;330:231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai Z, Ben-Younis A, Vlachaki A, Raleigh D, Thalassinos K. Understanding the structural dynamics of human islet amyloid polypeptide: advancements in and applications of ion-mobility mass spectrometry. Biophys Chem. 2024;312:107285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, Ridgway Z, Cao P, Ruzsicska B, Raleigh DP. Analysis of the ability of pramlintide to inhibit amyloid formation by human islet amyloid polypeptide reveals a balance between optimal recognition and reduced amyloidogenicity. Biochemistry. 2015;54:6704–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lutz TA. Control of energy homeostasis by amylin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1947–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong MF, King P, Macdonald IA, et al. Infusion of pramlintide, a human amylin analogue, delays gastric emptying in men with IDDM. Diabetologia. 1997;40:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao J, Belousoff MJ, Liang Y-L, et al. A structural basis for amylin receptor phenotype. Science. 2022;375: eabm9609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hay DL, Garelja ML, Poyner DR, Walker CS. Update on the pharmacology of calcitonin/CGRP family of peptides: IUPHAR review 25. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsen AT, Mohamed KE, Sonne N, Bredtoft E, Andersen F, Karsdal MA, et al. Does receptor balance matter?—Comparing the efficacies of the dual amylin and calcitonin receptor agonists cagrilintide and KBP-336 on metabolic parameters in preclinical models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156: 113842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coester B, Koester-Hegmann C, Lutz TA, Le Foll C. Amylin/calcitonin receptor-mediated signaling in POMC neurons influences energy balance and locomotor activity in chow-fed male mice. Diabetes. 2020;69:1110–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hay DL, Pioszak AA. RAMPs (Receptor-Activity Modifying Proteins): new insights and roles. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;56:469. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5559101/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Eržen S, Tonin G, Jurišić Eržen D, Klen J. Amylin, another important neuroendocrine hormone for the treatment of diabesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garelja ML, Hay D, Poyner DR, Walker CS. Calcitonin receptors in GtoPdb v.2023.1. IUPHARBPS guide to pharmacology CITE. 2023. http://journals.ed.ac.uk/gtopdb-cite/article/view/8664. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 47.Dehestani B, Stratford NR, Roux CWL. Amylin as a future obesity treatment. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021;30:320–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grizzanti J, Corrigan R, Casadesus G. Neuroprotective effects of amylin analogues on Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and cognition. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chwalba A, Dudek A, Otto-Buczkowska E. Role of amylin in glucose homeostasis. Austin Diabetes Res. 2019;4(1): 1021.

- 50.Gedulin BR, Rink TJ, Young AA. Dose-response for glucagonostatic effect of amylin in rats. Metabolism. 1997;46:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyle CN, Zheng Y, Lutz TA. Mediators of amylin action in metabolic control. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young AA, Gedulin BR, Rink TJ. Preliminary report Dose-responses for the slowing of gastric emptying in a rodent model by glucagon-like peptide (7–36)NH2, amylin, cholecystokinin, and other possible regulators of nutrient uptake. Metabolism. 1996;45:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gedulin BR, Young AA. Hypoglycemia overrides amylin-mediated regulation of gastric emptying in rats. Diabetes. 1998;47:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lutz TA. Amylinergic control of food intake. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ilag LL, Tabaei BP, Herman WH, et al. Reduced pancreatic polypeptide response to hypoglycemia and amylin response to arginine in subjects with a mutation in the HNF-4alpha/MODY1 gene. Diabetes. 2000;49:961–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zečević K, Volčanšek Š, Katsiki N, et al. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)—in search of ideal diagnostic criteria and precise treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;85:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young A. Inhibition of glucagon secretion. Adv Pharmacol. 2005;52:151–71. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1054358905520088. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Fineman M, Weyer C, Maggs DG, Strobel S, Kolterman OG. The human amylin analog, pramlintide, reduces postprandial hyperglucagonemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34:504–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fineman MS, Koda JE, Shen LZ, Strobel SA, Maggs DG, Weyer C, et al. The human amylin analog, pramlintide, corrects postprandial hyperglucagonemia in patients with type 1 diabetes. Metabolism. 2002;51:636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gogineni P, Melson E, Papamargaritis D, Davies M. Oral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and combinations of entero-pancreatic hormones as treatments for adults with type 2 diabetes: where are we now? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2024;25:801–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goyal RK. Gastric emptying abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1742–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jalleh RJ, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Marathe CS, Wu T, Horowitz M. Normal and disordered gastric emptying in diabetes: recent insights into (patho)physiology, management and impact on glycaemic control. Diabetologia. 2022;65:1981–93. 10.1007/s00125-022-05796-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyle CN, Lutz TA, Le Foll C. Amylin—Its role in the homeostatic and hedonic control of eating and recent developments of amylin analogs to treat obesity. Mol Metab. 2018;8:203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zakariassen HL, John LM, Lutz TA. Central control of energy balance by amylin and calcitonin receptor agonists and their potential for treatment of metabolic diseases. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;127:163–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lutz TA. The role of amylin in the control of energy homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lutz T. Amylin decreases meal size in rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;58:1197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geisler CE, Décarie-Spain L, Loh MK, et al. Amylin modulates a ventral tegmental area–to–medial prefrontal cortex circuit to suppress food intake and impulsive food-directed behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;95:938–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nashawi H, Gustafson TJ, Mietlicki-Baase EG. Palatable food access impacts expression of amylin receptor components in the mesocorticolimbic system. Exp Physiol. 2020;105:1012–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang G-J, Tomasi D, Backus W, Wang R, Telang F, Geliebter A, et al. Gastric distention activates satiety circuitry in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1824–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reda TK, Geliebter A, Pi-Sunyer FX. Amylin, food intake, and obesity. Obes Res. 2002;10:1087–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wielinga PY, Löwenstein C, Muff S, Munz M, Woods SC, Lutz TA. Central amylin acts as an adiposity signal to control body weight and energy expenditure. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osaka T, Tsukamoto A, Koyama Y, Inoue S. Central and peripheral administration of amylin induces energy expenditure in anesthetized rats. Peptides. 2008;29:1028–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fernandes-Santos C, Zhang Z, Morgan DA, Guo D-F, Russo AF, Rahmouni K. Amylin acts in the central nervous system to increase sympathetic nerve activity. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2481–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hropot T, Herman R, Janez A, Lezaic L, Jensterle M. Brown adipose tissue: a new potential target for glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in the treatment of obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:8592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pieber TR, Roitelman J, Lee Y, Luskey KL, Stein DT. Direct plasma radioimmunoassay for rat amylin-(1–37): concentrations with acquired and genetic obesity. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:E156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lutz TA. Effects of amylin on eating and adiposity. In: Joost H-G, editor. Appetite control. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. p. 231–50. 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_10. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roth JD, Roland BL, Cole RL, et al. Leptin responsiveness restored by amylin agonism in diet-induced obesity: evidence from nonclinical and clinical studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stern JH, Smith GI, Chen S, Unger RH, Klein S, Scherer PE. Obesity dysregulates fasting-induced changes in glucagon secretion. J Endocrinol. 2019;243:149–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lu C-X, An X-X, Yu Y, Jiao L-R, Canarutto D, Li G-F, et al. Pooled analysis of gastric emptying in patients with obesity: implications for oral absorption projection. Clin Ther. 2021;43:1768–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roth JD, Hughes H, Kendall E, Baron AD, Anderson CM. Antiobesity effects of the beta-cell hormone amylin in diet-induced obese rats: effects on food intake, body weight, composition, energy expenditure, and gene expression. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5855–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wookey PJ, Cooper ME. Amylin: physiological roles in the kidney and a hypothesis for its role in hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Novials A, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Chico A, El Assar M, Casas S, Gomis R. Amylin and hypertension: association of an amylin-G132A gene mutation and hypertension in humans and amylin-induced endothelium dysfunction in rats. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reinehr T, de Sousa G, Niklowitz P, Roth CL. Amylin and its relation to insulin and lipids in obese children before and after weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:2006–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mathiesen DS, Lund A, Vilsbøll T, Knop FK, Bagger JI. Amylin and calcitonin: potential therapeutic strategies to reduce body weight and liver fat. Front Endocrinol. 2021. 10.3389/fendo.2020.617400/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dacquin R, Davey RA, Laplace C, et al. Amylin inhibits bone resorption while the calcitonin receptor controls bone formation in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Horcajada-Molteni M-N, Chanteranne B, Lebecque P, et al. Amylin and bone metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:958–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gutiérrez-Rojas I, Lozano D, Nuche-Berenguer B, et al. Amylin exerts osteogenic actions with different efficacy depending on the diabetic status. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;365:309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu H, Xue X, Wang E, et al. Amylin receptor ligands reduce the pathological cascade of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2017;119:170–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu H, Wang X, Wallack M, et al. Intraperitoneal injection of the pancreatic peptide amylin potently reduces behavioral impairment and brain amyloid pathology in murine models of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:252–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang E, Zhu H, Wang X, et al. Amylin treatment reduces neuroinflammation and ameliorates abnormal patterns of gene expression in the cerebral cortex of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56:47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Adler BL, Yarchoan M, Hwang HM, et al. Neuroprotective effects of the amylin analogue pramlintide on Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and cognition. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Laugero KD, Tryon M, Mack C, et al. Peripherally administered amylin inhibits stress-like behaviors and enhances cognitive performance. Physiol Behav. 2022;244:113668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Potes CS, Pestana AC, Pontes M, Caramelo AS, Neto FL. Amylin modulates the formalin-induced tonic pain behaviours in rats. Eur J Pain. 2016;20:1741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang X, Yang J, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Amylin suppresses acetic acid-induced visceral pain and spinal c-fos expression in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2010;165:1429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rees TA, Tasma Z, Garelja ML, O’Carroll SJ, Walker CS, Hay DL. Calcitonin receptor, calcitonin gene-related peptide and amylin distribution in C1/2 dorsal root ganglia. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mathiesen DS, Lund A, Holst JJ, Knop FK, Lutz TA, Bagger JI. Therapy of endocrine disease: amylin and calcitonin—physiology and pharmacology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;186:R93-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Angelidi AM, Belanger MJ, Kokkinos A, Koliaki CC, Mantzoros CS. Novel noninvasive approaches to the treatment of obesity: from pharmacotherapy to gene therapy. Endocr Rev. 2022;43:507–57. 10.1210/endrev/bnab034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rubinić I, Kurtov M, Likić R. Novel pharmaceuticals in appetite regulation: exploring emerging gut peptides and their pharmacological prospects. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024;12:e1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Andreassen KV, Feigh M, Hjuler ST, Gydesen S, Henriksen JE, Beck-Nielsen H, et al. A novel oral dual amylin and calcitonin receptor agonist (KBP-042) exerts antiobesity and antidiabetic effects in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307:E24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bennett RG, Duckworth WC, Hamel FG. Degradation of amylin by insulin-degrading enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Smith SR, Blundell JE, Burns C, Ellero C, Schroeder BE, Kesty NC, et al. Pramlintide treatment reduces 24-h caloric intake and meal sizes and improves control of eating in obese subjects: a 6-wk translational research study. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E620-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith SR, Aronne LJ, Burns CM, Kesty NC, Halseth AE, Weyer C. Sustained weight loss following 12-month pramlintide treatment as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention in obesity. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1816–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ryan G, Jobe L, Briscoe T. Review of pramlintide as adjunctive therapy in treatment of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2008;2:203-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Heptulla RA, Rodriguez LM, Mason KJ, Haymond MW. Twenty-four-hour simultaneous subcutaneous Basal-bolus administration of insulin and amylin in adolescents with type 1 diabetes decreases postprandial hyperglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1608–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Haidar A, Tsoukas MA, Bernier-Twardy S, et al. A novel dual-hormone insulin-and-pramlintide artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:597–606. 10.2337/dc19-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Idris I. Novel development of a co-formulation of insulin and amylin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;1:e00015. 10.1002/2.00015. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kadiyala N, Hovorka R, Boughton CK. Closed-loop systems: recent advancements and lived experiences. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2024;21:927–41. 10.1080/17434440.2024.2406901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tsoukas MA, Majdpour D, Yale J-F, et al. A fully artificial pancreas versus a hybrid artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes: a single-centre, open-label, randomised controlled, crossover, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3:e723–32. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landig/article/PIIS2589-7500(21)00139-4/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Majdpour D, Tsoukas MA, Yale J-F, El Fathi A, Rutkowski J, Rene J, et al. Fully automated artificial pancreas for adults with type 1 diabetes using multiple hormones: exploratory experiments. Can J Diabetes. 2021;45:734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ratner RE, Dickey R, Fineman M, et al. Amylin replacement with pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycaemic and weight control in Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year, randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2004;21:1204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mack CM, Soares CJ, Wilson JK, Athanacio JR, Turek VF, Trevaskis JL, et al. Davalintide (AC2307), a novel amylin-mimetic peptide: enhanced pharmacological properties over native amylin to reduce food intake and body weight. Int J Obes. 2005;2010(34):385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fletcher MM, Keov P, Truong TT, Mennen G, Hick CA, Zhao P, et al. AM833 is a novel agonist of calcitonin family G protein-coupled receptors: pharmacological comparison with six selective and nonselective agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2021;377:417–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lau DCW, Erichsen L, Francisco AM, Satylganova A, le Roux CW, McGowan B, et al. Once-weekly cagrilintide for weight management in people with overweight and obesity: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active-controlled, dose-finding phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:2160–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.AstraZeneca. Our pipeline. https://www.astrazeneca.com/our-therapy-areas/pipeline.html. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 115.Mather K, et al. Long acting amylin receptor agonist, AZD6234, shows advantages over GLP-1 receptor agonist activation for leptin re-sensitization in a diet-induced obese (DIO) rat model. In: ObesityWeek 2024, 2–6 November 2024, San Antonio. Poster 576.

- 116.Zealand Pharma. Petrelintide. https://www.zealandpharma.com/pipeline/petrelintide/. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 117.Axelsen M, Sidhu S. A study in healthy male volunteers to look at the safety and tolerability of the new test medicine GUB014295 and how it is taken up by the body when given as a single dose by injection. https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN85112396. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 118.Melson E, Ashraf U, Papamargaritis D, Davies MJ. What is the pipeline for future medications for obesity? Int J Obes (Lond). 2024. 10.1038/s41366-024-01473-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Larsen AT, Gydesen S, Sonne N, Karsdal MA, Henriksen K. The dual amylin and calcitonin receptor agonist KBP-089 and the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide act complimentarily on body weight reduction and metabolic profile. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Larsen AT, Melander SA, Sonne N, et al. Dual amylin and calcitonin receptor agonist treatment improves insulin sensitivity and increases muscle-specific glucose uptake independent of weight loss. Biomed Pharmacother Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164: 114969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jorsal T, Rungby J, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T. GLP-1 and amylin in the treatment of obesity. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Becerril S, Frühbeck G. Cagrilintide plus semaglutide for obesity management. Lancet. 2021;397:1687–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Enebo LB, Berthelsen KK, Kankam M, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2·4 mg for weight management: a randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1736–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Frias JP, Deenadayalan S, Erichsen L, et al. Efficacy and safety of co-administered once-weekly cagrilintide 2·4 mg with once-weekly semaglutide 2·4 mg in type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2023;402:720–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Novo Nordisk A/S. CagriSema demonstrates superior weight loss in adults with obesity or overweight in the REDEFINE 1 trial. https://www.novonordisk.com/news-and-media/news-and-ir-materials/news-details.html?id=915082. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 126.Novo Nordisk Global. R&D pipeline. https://www.novonordisk.com/content/nncorp/global/en/science-and-technology/r-d-pipeline.html. Accessed 3 Mar 2025.

- 127.Gasiorek A, Heydorn A, Kirkeby K, et al. Safety, tolerability and weight reduction findings of oral amycretin: a novel amylin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor co-agonist, in a first-in-human study. 2024. https://www.easd.org/media-centre/home.html#!resources/b-safety-tolerability-and-weight-reduction-findings-of-oral-amycretin-a-novel-amylin-and-glucagon-like-peptide-1-receptor-co-agonist-in-a-first-in-human-study-b. Accessed

- 128.Healthline. In early study, people on weight loss pill lost 13% of their body weight. 2024. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health-news/in-early-study-people-on-weight-loss-pill-lost-13-of-their-body-weight. Accessed 8 Dec 2024.