Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether enema is associated with nervous system injury caused by diquat poisoning using a population-based case-control analysis. Medical records of patients with acute diquat poisoning admitted to the hospital from January 2018 to January 2024 were retrospectively collected. Central nervous system injury symptoms following diquat poisoning defined the case group, while the control group were matched 1:2 on population-based without nervous system injury in diquat poisoning patients. Conditional logistic regression models were used for analysis. We identified 101 diquat poisoning patients with nervous system injury and selected 202 diquat poisoning patients without nervous system injury. Diquat poisoning patients performed 2 and ≧ 3 enemas had ORs of nervous system injury of 3.084 (95% CI 1.230, 7.734) and 4.693 (95% CI 1.408, 15.645) compared with diquat poisoning patients with no enema, respectively. Further analyses were performed in various age subgroups. The ORs of conducting 2 and ≧ 3 enemas were dramatically higher among case group than control group in subgroup aged ≧ 60 years old (OR 10.184, 14.982 respectively). We concluded that enema may be associated with an increased risk of nervous system injury caused by DQ poisoning, particularly among the elderly.

Keywords: Enema, Nervous systems injury, Diquat poisoning, Population-based, Microbiota-brain-gut axis

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Neurology, Risk factors

Introduction

The prohibition of paraquat manufacturing in China has led to the widespread utilization of diquat (DQ) in agriculture due to its potent herbicidal properties, resulting in an escalation in diquat poisoning cases1,2. DQ is recognized as a potent toxin that can cause extensive damage to various tissues and organs in the body, with the digestive tract and kidneys being the most frequently affected, followed by the lungs and livers3,4. It is crucial to highlight that DQ also induces toxic effects on the central nervous systems, manifesting in clinical symptoms such as dizziness, drowsiness, seizures, unconsciousness, convulsions and disorientation5,6. The presence of central nervous system damage often indicates a more severe condition with a poorer prognosis7,8. While existing research on DQ poisoning primarily focuses on the main target organs like the kidneys, liver, and digestive tract, studies on central nervous system injury are relatively scarce. Currently, there are no established biomarkers for assessing the occurrence of nervous systems injury caused by DQ poisoning.

Enema has been suggested as an efficacious therapeutic approach for acute poisoning, aiming to eradicate or diminish the absorption of toxic substances from the gastrointestinal tract7. Nonetheless, in clinical observations, it has been noted that certain DQ poisoning patients who have sustained nervous system injury have a history of undergoing multiple enemas procedures. Patients who undergo excessive enemas or have compromised health are susceptible to dysbiosis of the gut microbiota post-enema. Grounded in the brain-gut axis theory, an increasing body of research is concentrating on the correlation between dysbiosis of the gut microbiota and neurological system impairment9–11. The correlation between enema treatments and DQ-induced neurotoxicity has not been documented in the current medical literature.

This research intended to investigate the correlation between enema and nervous system injury caused by DQ poisoning utilizing population stratification techniques. Considering the influence of age on neurodegenerative conditions, we conducted a more detailed analysis of the correlation between enema administration and nervous system damage across various age demographics.

Methods and measurement

The following clinical parameters were extracted from the hospital Health Information System (HIS) electronic medical records: age, gender, educational background, Body Mass Index (BMI), medical history, the incidence of gastric lavage and hematodialysis procedures, initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at admission, plasma DQ concentration, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Serum Creatinine (Scr), Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB), Troponin I (TnI), Lactic Acid (Lac), and the frequency of enema administration. All laboratory tests were ordered and blood samples taken within 24 h of admission. Upon the patient’s admission to the emergency department, communicate to the patient or their legal guardian the indications and potential complications associated with enema therapy. Following the acquisition of informed consent documentation, proceed with the administration of the medicated enema. Insert a lubricated anal catheter or silicone tube through the anal orifice into the rectum to an approximate depth of 15 cm. Subsequently, attach an infusion set or syringe to administer the enema solution slowly into the rectal cavity. The enema solution should be maintained at a temperature of approximately 38 °C, and the infusion pressure must be kept low to prevent damage to the intestinal mucosa. After administration, retain the enema solution for a designated period to enhance toxin dissolution and elimination. Utilizing a high-volume enema technique, continue to irrigate the intestinal tract with the enema solution until the effluent appears clear. This study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Nanjing University School of Medicine affiliated Jinling Hospital. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or guardians gave informed consent to the study.

Considering that this study was a case-control study and the exposure factor under investigation was a categorical variable, the formula for calculating the sample size of the control group: Ncontrol = (n + 1)*P1(1 − P1)*(Uα + Uβ)2/(P1 − P2)2. (n is the ratio of control group to case group; P1 was exposure ratio of control group, P2 was exposure ratio of case group; Uα is the critical value of the standard normal distribution, corresponding to the studied powe; Uβ is the critical value of the standard normal distribution, corresponding to the confidence level.)

Statistical analysis

Upon the completion of data acquisition, we initiated an initial data cleansing process, which encompassed the elimination of redundant records, the imputation of missing values (employing methods such as mean or median imputation), and the identification and treatment of outliers. The distribution patterns of continuous variables were determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Continuous variables adhering to a normal distribution were represented as Mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD), whereas those following a non-normal distribution were denoted as Median (interquartile range, Median [IQR]). Categorical variables were depicted as frequencies (percentages). For the comparative analysis of continuous variables between two groups, the independent samples t-test was utilized if the data demonstrated normality and homogeneity of variances. Conversely, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for data that did not meet normal distribution criteria. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, based on their frequencies or percentages. We performed conditional logistic regression analysis to compute the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for the association between enemas and DQ nervous system injury. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (version 24).

Results

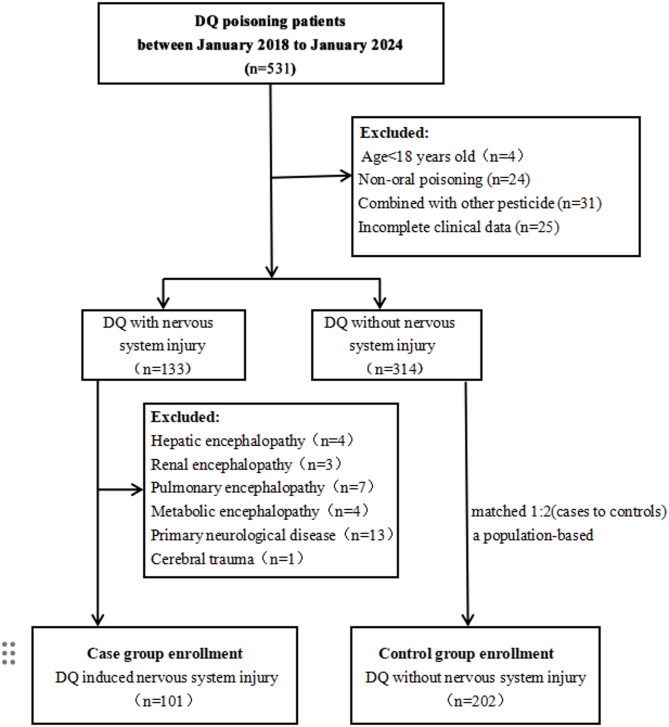

A cohort of 101 patients with nervous system injury caused by DQ poisoning were identified as the case group, accompanied by 202 DQ poisoning patients without nervous system impairment matched with age interval as control group. The cases and controls screening process was shown in Fig. 1. Of the 303 sample subjects, the median age was 55.0 years(Interquartile Range [IQR] 42.0, 69.0). The median ages for the case group and the control group were 55.0 years (IQR 42.5, 69.5) and 54.0 years (IQR 42.0, 69.3), respectively. Owing to the stratification of all age subgroups, there was no statistically significant difference in the aggregate age and the age distribution of each subgroup between the two cohorts. Table 1 presents the baseline characters and medical co-morbidities between case and control group. There was no significant difference in gender (P = 0.181), education (P = 0.480), BMI (P = 0.549), hypertension (P = 0.337), diabetes mellitus (P = 0.167), chronic heart disease (P = 0.555), hematodialysis (P = 0.467), gastric lavage (P = 0.724), initial GCS (P = 0.097) between these two groups.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting the methodology for case-control selection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the cases group and controls group.

| Variable | Case group (n = 101) |

Control group (n = 202) |

z/x2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), n (%) | – | 1 | ||

| 18–44 | 30 (29.7%) | 60 (29.7%) | ||

| 45–59 | 35 (34.7%) | 70 (34.7%) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 36 (35.6%) | 72 (35.6%) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 1.788 | 0.181 | ||

| Male | 44 (43.6%) | 72 (35.6%) | ||

| Female | 57 (56.4%) | 130 (64.4%) | ||

| Education, n (%) | 0.499 | 0.480 | ||

| No bachelor degree | 73 (72.3%) | 138 (68.3%) | ||

| Bachelor degree | 28 (27.7%) | 64 (31.7%) | ||

| BMI | 23.0 (19.0, 26.0) | 22.0 (19.0, 25.2) | − 0.599 | 0.549 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 16 (15.8%) | 24 (11.9%) | 0.922 | 0.337 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 13 (12.9%) | 16 (7.9%) | 1.907 | 0.167 |

| Chronic heart disease, n (%) | 7 (6.9%) | 18 (8.9%) | 0.349 | 0.555 |

| Hematodialysis, n (%) | 0.530 | 0.467 | ||

| Yes | 86 (85.1%) | 178 (88.1%) | ||

| No | 15 (14.9%) | 24 (11.9%) | ||

| Gastric lavage, n (%) | 0.125 | 0.724 | ||

| Yes | 96 (95.0%) | 190 (94.1%) | ||

| No | 5 (5.0%) | 12 (5.9%) | ||

| Initial GCS | 13.0 (11.0, 14.0) | 12.0 (11.0, 14.0) | − 1.658 | 0.097 |

BMI, Body Mass Index, Initial GCS, Initial Glasgow Coma Scale.

The laboratory tests of patients between case and control group were presented in Table 2. The concentrations of plasma DQ (P < 0.001), NLR (P < 0.001), Scr (P = 0.022), and Lac (P < 0.001) were significantly elevated in the case group compared to the control group. There were no significant differences in other parameters such as AST (P = 0.842), ALT (P = 0.114), BUN (P = 0.413), TnI (P = 0.055) and CK-MB (P = 0.899).

Table 2.

Laboratory tests of patients in the cases group and controls group.

| Variable | Case group (n = 101) |

Control group (n = 202) |

z | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma DQ concentration (mg/L) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.2) | 2.9 (2.3, 3.5) | − 3.750 | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 22.9 (15.6, 23.1) | 20.2 (18.8, 30.8) | − 4.930 | < 0.001 |

| Scr (umol/L) | 138.8 (89.6, 183.5 ) | 112.7 (89.2, 164.3 ) | − 2.295 | 0.022 |

| Bun (mmol/L) | 9.0 (7.9, 11.3) | 9.2 (7.9, 11.1) | − 0.819 | 0.413 |

| AST (U/L) | 41.0 (31.5, 49.5) | 40.0 (34.0, 47.0) | − 0.199 | 0.842 |

| ALT (U/L) | 39.0 (29.0, 46.0) | 36.0(29.0, 43.0) | − 1.579 | 0.114 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 27.0 (23.0, 33.0) | 28.0 (20.0, 34.0) | − 0.127 | 0.899 |

| TnI (ng/ml) | 0.01(0.01, 0.03) | 0.01(0.01, 0.02) | − 1.919 | 0.055 |

| Lac (mmol/L) | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (3.0, 4.0) | − 5.602 | < 0.001 |

NLR, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio; Scr, Serum creatinine; BUN, Blood Urea Nitrogen; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; CK-MB, Creatine kinase-MB; TnI, Troponin I; Lac, Lactic acid.

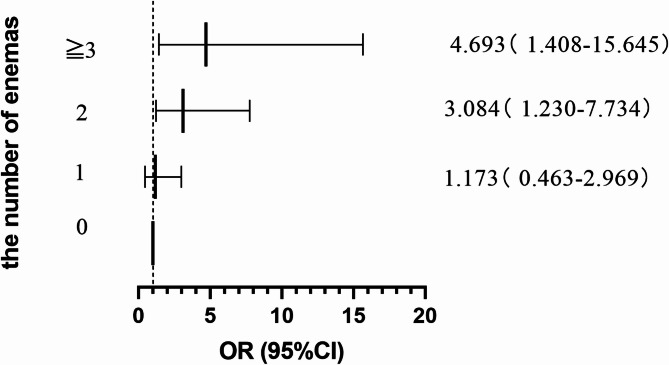

Table 3; Fig. 2 showed the number of enemas in case group and control group. In DQ poisoning patients, those undergoing enemas with frequencies of 2 and ≧ 3 exhibited ORs for nervous system injury of 3.120 (95% CI 1.402, 6.943) and 6.900 (95% CI 2.610, 18.242) respectively, compared to those without enemas. Following adjustments for plasma DQ concentration, NLR, Scr, and Lac, the ORs for nervous system injury remained significantly elevated at 3.084 (95% CI 1.230, 7.734) for patients with 2 enemas and 4.693 (95% CI 1.408, 15.645) for those with ≧ 3 enemas, in comparison to patients who did not receive enemas. No substantial differentiation was detected between cases and controls in patients administered a single enema treatment (P = 0.737).

Table 3.

Odds ratios of patients with different numbers of enemas in the cases group and controls group.

| Number of enemas | Case group (n = 101) |

Control group (n = 202) |

Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 (9.9%) | 39 (19.3%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| 1 | 24 (23.8%) | 95 (47.1%) | 0.985 (0.431–2.252) | 1.173 (0.463–2.969) | 0.737 |

| 2 | 44 (43.6%) | 55 (27.2%) | 3.120 (1.402–6.943) | 3.084 (1.230–7.734) | 0.016 |

| ≧ 3 | 23 (22.7%) | 13 (6.4%) | 6.900 (2.610-18.242) | 4.693 (1.408–15.645) | 0.012 |

OR, odds ratio.

*Adjustments are made for patients’ DQ plasma concentration, NLR, Scr, Lac.

**Adjusted OR.

Fig. 2.

ORs for nervous system injury caused by DQ according to the number of enemas.

Table 4 illustrated the impact of various enemas times on DQ induced nervous system injury across different age subgroups. Among individuals aged 18–44, the ORs for nervous system injury associated with 1, 2, and ≧ 3 enemas demonstrate no statistically significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). Among subgroup aged 45 to 59, the administration of 2 and ≧ 3 enemas were correlated with crude ORs of 5.667 (95%CI 1.384, 23.198) and 9.067 (95% CI 1.724, 47.675) for nervous system injury. However, after adjustments for plasma DQ concentration, NLR, Scr, and Lac, the administration of two enemas did not show a significant increase in risk of nervous system injury, while receiving ≧ 3 enemas was associated with an increased risk of DQ poisoning brain injury, with adjusted OR 12.952 (95% CI 1.368, 122.620). In the patient subgroup aged over 60, those subjected to 2 and ≧ 3 enemas showed ORs for nervous system injury of 10.182 (95% CI 1.465, 70.328) and 14.983 (95% CI 1.765, 127.160) respectively, in comparison to individuals who did not receive enema treatment after adjusting for plasma DQ concentration, NLR, Scr, and Lac.

Table 4.

Prevalence and ORs of enemas for nervous system injury caused by DQ in the age subgroup analysis.

| Number of enemas in age subgroup |

Case group (n = 101) |

Control group (n = 202) |

Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–44 (years ) |

Subgroup (n = 30) |

Subgroup (n = 60) |

|||

| 0 | 4 (13.3%) | 6 (10.0%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| 1 | 8 (26.7%) | 27 (45.0%) | 0.444(0.100-1.974) | 0.565 (0.094–3.376) | 0.531 |

| 2 | 11 (36.7%) | 23 (38.3%) | 0.717(0.167–3.073) | 0.689 (0.122–3.904) | 0.674 |

| ≧ 3 | 7 (23.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | 2.625(0.450–15.310) | 2.903 (0.353–23.892) | 0.322 |

| 45–59 (years) |

Subgroup (n = 35) |

Subgroup (n = 70) |

|||

| 0 | 3 (8.5%) | 17 (24.3%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| 1 | 8 (22.9%) | 32 (45.7%) |

1.417 (0.332–6.048) |

1.803 (0.284–11.433) | 0.532 |

| 2 | 16 (45.7%) | 16(22.9%) |

5.667 (1.384–23.198) |

4.849 (0.822–28.599) | 0.081 |

| ≧ 3 | 8 (22.9%) | 5 (7.1%) |

9.067 (1.724–47.675) |

12.952 (1.368–122.620) | 0.026 |

| ≥ 60 (years) |

Subgroup (n = 36) |

Subgroup (n = 72) |

|||

| 0 | 3 (8.3%) | 16 (22.2%) | 1 | 1 | - |

| 1 | 8 (22.2%) | 36 (50.0%) | 1.185 (0.278–5.061) | 0.961 (0.143–6.481) | 0.967 |

| 2 | 17 (47.3%) | 16 (22.2%) | 5.667 (1.384–23.198) | 10.184 (1.475–70.328) | 0.019 |

| ≧ 3 | 8 (22.2%) | 4 (5.6%) | 10.607 (1.909–59.615) | 14.982 (1.765–127.160) | 0.013 |

*Adjustments are made for patients’ DQ plasma concentration, NLR, Scr, Lac.

**Adjusted OR.

Discussion

This is the first epidemiological study conducted assessing the association between enema and DQ-induced nervous system injury. To control for the confounding variable of age, we employed age group matching. Our investigation revealed that DQ poisoning patients who underwent 2 and ≥ 3 enemas exhibited a 3.084-fold and 4.643-fold elevated risk of nervous system injury, respectively, after adjustments for DQ plasma concentration, NLR, Scr, and Lac. The results underscore that the administration of 2 or more enemas could potentially heighten the risk of nervous system injury caused by DQ poisoning. While diquat is not inherently a neurotoxin, it has the potential to induce elevated oxidative stress within cerebral tissues12. Research on the impact of DQ poisoning on nervous system damage is sparse, with most existing studies being conducted on animal models. These research indicated that DQ exposure in mice causes oxidative stress, resulting in the degeneration of dopamine neurons, reduced dopamine uptake capacity, and neuroinflammation in the hippocampus6,13. Nevertheless, MR imaging analyses of DQ poisoning revealed that dopaminergic nuclei were unaffected, a finding that contradicted outcomes observed in preclinical animal studies14. The exact mechanism by which DQ poisoning leads to nervous system injury remains unknown.

Enema therapy, a prevalent intervention for acute toxicological emergencies, entails the administration of a fluid into the colon to facilitate the expulsion of unabsorbed toxins. Nonetheless, excessive or recurrent enemas may deplete beneficial microbiota from the gastrointestinal tract, while concurrently introducing pathogenic microorganisms, thereby disrupting the gut microbiome. Disruption of the gut microbiome not only impairs gastrointestinal function but also has the potential to affect the central nervous system through the gut-brain axis. The microbiota-brain-gut axis constitutes an intricate neuroendocrine-immune circuit linking the central nervous system to the gastrointestinal tract. This axis encompasses not only neurochemical signaling but also the interplay of endocrine responses and immunological mediators15,16. Disruption of the gut microbiota can impair the synthesis and equilibrium of neuroactive compounds, potentially leading to dysregulation of the neurotransmitter system and consequent exacerbation or onset of neurological disorders. In addition, the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can compromise intestinal permeability by disrupting the integrity of the intestinal barrier, thereby permitting the translocation of deleterious substances and bacterial endotoxins into the systemic circulation, which can exacerbate neuroinflammatory responses17. However, it remains to be elucidated whether enema influence the nervous system injury after DQ poisoning via the “microbiota-brain-gut axis”, necessitating validation through future clinical and foundational research.

In order to elucidate the correlation between enema and neurotoxicity induced by DQ poisoning, we implemented a stratified population-based case-control study categorized by age groups. Utilizing univariate analysis, we identified significant statistical disparities between the case and control group concerning plasma DQ levels, NLR, Lac, Scr, and the frequency of enema administration (specifically, twice, or three or more times). To further elucidate the association between enema frequency and DQ-induced neurotoxicity, we conducted a multivariate analysis incorporating plasma DQ concentration, NLR, Lac, and Scr as covariates. The conclusive findings demonstrated that undergoing 2 and ≥ 3 enemas increased the risk of DQ-related nervous system injury, with ORs 3.084(95%CI 1.230, 7.734) and 4.693(95%CI 1.408, 15.645) respectively. To further validate our findings, we performed analyses among subgroups of different age ranges further. Subgroup analysis revealed that the administration of enemas exerts a more pronounced effect on geriatric patients relative to their younger counterparts. Within the subgroup of individuals aged 18 to 44, the prevalence of enemas was not associated with an elevated risk of DQ-induced nervous system injury. In the 45–59 age subgroup, following adjustments for multiple statistically significant variables identified through univariate analyses, plasma DQ concentration, NLR, Lac, and Scr, it was found that receiving ≧ 3 enemas singularly increased the risk of nervous system injury caused by DQ poisoning. Conversely, in the subgroup aged 60 and older, the administration of both 2 and ≧ 3 enemas were correlated with an increased risk of DQ-induced brain injury, even after controlling for statistically significant variables determined by univariate analysis. The data indicated that the susceptibility to DQ-induced nervous system injury after enemas escalates with advancing age, particularly among the geriatric demographic. Senescence is correlated with the deterioration of various physiological systems, including cerebrovascular integrity, intestinal mucosal defenses, immunological responses, and central nervous system functionality18. Furthermore, age-associated modifications in the central nervous system, such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and other metabolic disorders, may exacerbate the prevalence of encephalopathy following enema administration in elderly individuals. Furthermore, Changes in gut microbiota in older patients may also be an important reason. The precise pathobiological processes facilitating this association remain enigmatic and necessitate extensive scientific investigation.

In conclusion, our findings indicated that enema may be associated with an increased risk of nervous system injury in DQ poisoning, particularly in patients aged over 60. Considering that enemas are among the therapeutic interventions for alleviating DQ toxicity, yet they may increase the risk of neurotoxicity caused by DQ, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis of the therapeutic efficacy against the potential neurotoxic hazards before integrating this approach into clinical guidelines.

Limitations: The principal and perhaps most vital constraint of any retrospective investigation pertains to the likelihood of selection bias. In our research, we grappled with the phenomenon universally termed Berkson’s bias, emerging when the choice of case studies and controls is swayed by their hospital admission status, contrarily to the condition under scrutiny. This bias is notably pervasive in single-center researches where the chosen sample might not be an accurate reflection of the wider demographic. Another limitation inherent to our study design was the small sample size utilized in subgroup analyses. Subgroup analyses can provide valuable insights, especially when exploring specific characteristics that may modify treatment effects or outcomes. However, when the sample sizes for these subgroups are small, the results become less reliable and more susceptible to variability. Potential confounders, including patients’ baseline health conditions, the procedural timing (specifically, the administration of an enema), and the severity of DQ toxicity, could significantly influence the study’s results. In order to substantiate the observed phenomena and elucidate the precise associations between enema and nervous system injury caused by DQ in this context, it is imperative to undertake additional prospective investigations, characterized by rigorously defined parameters and substantially larger, more representative cohorts.

Methods

Selection of cases and controls

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients presenting with acute DQ poisoning who were admitted to the Emergency Medicine Department at Jinling Hospital, affiliated with Nanjing University School of Medicine, from January 2018 to January 2024. The inclusion criteria for the control group were patients diagnosed with DQ poisoning through blood or urine toxicity testing, and who displayed no signs of nervous system injury post-toxic exposure. The exclusion criteria for the control group encompass several important factors to ensure the validity of the study. Firstly, individuals under the age of 18 years will be excluded, as adult physiology and responses to poisoning differ significantly from that of minors. Additionally, patients involving non-oral poisoning will not be considered, focusing solely on those who have ingested the toxin orally. Participants who concurrently exhibit signs of other pesticide poisoning, confirmed through blood or urine tests, will also be excluded to avoid confounding variables that could impact the study’s outcomes. Furthermore, any subjects with incomplete clinical data related to DQ poisoning will be eliminated from the control group. The criteria for including participants in the case group (DQ nervous system injury group) were the patients presented with typical symptoms of neurologic (dizziness, drowsiness, convulsions, coma, excitement, irritability and disorientation) and imaging evidence of nervous system lesions (axonal degeneration of nervous system and pontine myelinolysis) following DQ poisoning19,20. The exclusion criteria for the case group, in addition to the control group criteria, include patients who had a pre-existing history of neurological deficits or the manifestation of neurological symptoms prior to hospital admission, encompassing hepatic encephalopathy, renal encephalopathy, pulmonary encephalopathy, metabolic encephalopathy, primary neurological disorders, and cerebral trauma. By applying these inclusion and exclusion criteria, we conducted a screening of 101 cases with different age levels. To mitigate the confounding influence of age on the study outcomes, we implemented an age-stratified matching protocol with a 1:2 ratio (cases to controls). The age categories were delineated as 18–44 years (young adults), 45–59 years (middle-aged adults), and 60 years and above (older adults).

Author contributions

XX and SNN: conceived the study, designed the study, and final approval of the manuscript. SNN and CBH: obtained research funding. ZRS and JKM: study literature search, collect the clinical data and manuscript editing.

Funding

The study was supported by Major project of Scientific Research Program for Colleges and Universities of Anhui Provincial Education Department (Grant Number: 2022AH040168); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant Number: BK20211136).

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Nanjing University School of Medicine affiliated Jinling Hospital(Grant ID: 2023DZKY-035). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or guardians gave informed consent to the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhaorui Sun, Email: sunzhr84@163.com.

Shinan Nie, Email: shn_nie@sina.com.

References

- 1.China MoAaRAotPsRo. The No.1745 Bulletin of the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, and General Administration of Quality Supervision (Inspection and Quarantine of the People‘s Republic of China, 2016).

- 2.Zhu, Q. et al. Evaluation of Lac and NGAL on the condition and prognosis of patients with Diquat poisoning. Prehosp. Disast. Med.38(5), 564–569 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng, D. H. et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of acute kidney injury caused by Diquat poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila)61(9), 705–708 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He, C. et al. Prognosis prediction of procalcitonin within 24 h for acute Diquat poisoning. BMC Emerg. Med.24(1), 61 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu g,Jian, T. et al. Acute Diquat poisoning resulting in toxic encephalopathy: A report of three cases. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila)60(5), 647–650 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou, J. N. & Lu, Y. Q. Lethal Diquat poisoning manifests as acute central nervous system injury and circulatory failure: a retrospective cohort study of 50 cases. EClinicalMedicine52, 101609 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magalhães, N., Carvalho, F. & Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. Human and experimental toxicology of Diquat poisoning: Toxicokinetics, mechanisms of toxicity, clinical features, and treatment. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.37(11), 1131–1160 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xing, J. et al. Lethal Diquat poisoning manifesting as central Pontine myelinolysis and acute kidney injury: A case report and literature review. J. Int. Med. Res.48(7), 0300060520943824 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baj, A. et al. Glutamatergic signaling along the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20(6), 1482 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin, C. R. et al. The brain-gut-microbiome axis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.6(2), 133–148 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomaa, E. Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek113(12), 2019–2040 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Koksel, Y. & Mckinney, A. M. Potential reversible and recognizable acute encephalopathic syndromes disease categorization and MRI appearances. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.41(8), 1328–1338 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi, C. et al. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying astrocyte-microglia crosstalk in hippocampal neuroinflammation induced by acute Diquat exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int.31(10), 15746–15758 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao, X. et al. MR study on white matter injury in patients with acute Diquat poisoning. Neurotoxicology106, 37–45 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, Q. & Xia, J. Influence of the gut Microbiome on inflammatory and immune response after stroke. Neurol. Sci.42(12), 4937–4951 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, S. Microglial activation after ischaemic stroke. Stroke Vasc. Neurol.4(2), 71–74 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dlugosz, A. et al. Increased serum levels of lipopolysaccharide and antiflagellin antibodies in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil.27(12), 1747–1754 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippert, K. et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with glucose metabolism disorders and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. Benef. Microbes84(4), 545–556 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh, M., Murthy, V. & Ramassamy, C. Neuroprotective mechanisms of the standardized extract of bacopa Monniera in a Paraquat/diquat mediated acute toxicity. Neurochem. Int.62(5), 530–539 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonneh-Barkay, D., Langston, W. J. & Di Monte, D. A. Toxicity of redox cycling pesticides in primary mesencephalic cultures. Antioxid. Redox Signal.7(5–6), 649–653 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.