Abstract

Electrocatalysts for oxidation and reduction reactions are crucial for sustainable energy production and carbon reduction. While precious metal catalysts exhibit superior activity, reducing reliance on them is necessary for large‐scale applications. To address this, transition metal‐based catalysts are studied with strategies to enhance catalytic performance. One promising strategy is heterostructures, which integrate multiple materials to harness synergistic effects. Developing efficient heterostructured electrocatalysts requires understanding their intricate characteristics, which poses challenges. While in situ and operando spectroscopy provides insights, computational materials science is essential for capturing reaction mechanisms, analyzing the origins at the atomic scale, and efficiently exploring innovative heterostructures. Despite growing recognition of computational materials science, standardized criteria for these systems remain lacking. This review consolidates case studies to propose approaches for modeling and analyzing heterostructures. It categorizes heterostructure types into vertical, semivertical, and lateral, defines their characteristics, and propose insights into minimizing or exploiting strain effects from lattice mismatches. Furthermore, it summarizes computational analyses of heterostructure stability and activity across reactions, including oxygen evolution, hydrogen evolution, oxygen reduction, carbon dioxide reduction, nitrogen reduction, and urea oxidation. This review provides an overview to refine heterostructure designs and establish a framework for systematic modeling and analysis to develop efficient electrocatalysts.

Keywords: activities, computational materials sciences, density functional theories, electrocatalysts, heterostructures, modeling, stabilities

This review systematically explores computational approaches for modeling and analyzing heterostructures. From a computational materials science perspective, it provides insights into determining heterostructure design types, optimizing lattice strain, and analyzing structural and electronic properties through case studies. Applications of heterostructured electrocatalysts and machine learning methods are discussed, contributing to the designing of heterostructure materials for sustainable energy systems.

1. Introduction

Electrocatalysis is essential for advancing sustainable energy production and efficient carbon reduction technology.[ 1 ] Efforts to enhance catalytic efficiency are imperative across various electrochemical oxidation and reduction reactions. Notably, electrocatalysts play a pivotal role in water splitting, an ecofriendly method for hydrogen production without carbon emissions, which involves the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode. Meanwhile, enhancing the catalytic efficiency of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) at the cathode is significant for improving the performance of fuel cells and metal–air batteries. In carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR), advanced electrocatalysts are instrumental in reducing greenhouse gases while yielding high‐value products. The effective nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR) and urea oxidation reaction (UOR) offer promising avenues for next‐generation sustainable energy, with potential benefits including increased ammonia production and improved fertilizer availability.[ 2 ] For the industrial commercialization of these electrochemical reactions, a wide range of electrocatalysts have been explored. Platinum group metal catalysts are known to exhibit excellent performance in various electrochemical reactions. However, their high cost and limited availability necessitate alternatives for large‐scale applications. Consequently, alternative electrocatalysts, including transition metal (TM) oxides, nitrides, carbides, sulfides, and phosphides, as well as carbon‐based materials such as graphene, graphite with heteroatom doping, and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), have been used in electrochemical reactions.[ 3 ] Despite the potential of these alternatives, significant opportunities for the improvement in catalytic activity and durability still exist. In addition to exploring new material groups, several strategies aimed at enhancing the intrinsic properties of catalysts have been proposed. These include nanostructure engineering, vacancy engineering, phase engineering, interface engineering, structure integration, doping, and strain effects.[ 4 ] The adoption of these approaches has demonstrated that cost‐effective TM‐based electrocatalysts can achieve or even surpass the performance of precious metal catalysts. This offers a promising strategy for reducing costs without compromising efficiency.

Among these various strategies, heterostructure catalysts, also referred to as heterogeneous structures, which combine multiple materials to significantly enhance performance, have garnered particular attention. Catalysts composed of a single material often face a trade‐off between activity and durability.[ 5 ] To address this, the heterostructure approach has been applied, wherein multiple materials are integrated to complement each other's limitations.[ 6 ] For example, when a metal and a semiconductor form a heterojunction, a built‐in electric field is established due to differences in work function and electronic band structure between the two materials. This electric field can induce a Mott–Schottky heterojunction, enhancing electron transfer efficiency and catalytic activity.[ 7 ] Additionally, phase engineering, which employs both long‐range disordered amorphous and conductive crystalline phases, has been reported to improve catalyst activity and stability.[ 8 ] Low‐dimensional materials based heterostructures are also of great interest due to their tunable electronic properties, though challenges remain in developing controllable synthesis methods. Theoretical calculations and in situ characterizations have been utilized to better understand these heterostructure catalysts.[ 9 ] Furthermore, surface reconstruction during electrochemical reactions can transform precatalysts into layered double hydroxides (LDH) or oxyhydroxides, forming protective layers that prevent dissolution and provide active sites. These heterostructures function as multifunctional catalysts, improving electrochemical oxidation and reduction reactions by leveraging the advantages of diverse materials.[ 10 ] Finally, integrating catalysts with distinct roles is a viable strategy. For instance, in alkaline HER, both water splitting capability and efficient hydrogen adsorption are necessary, as protons are sourced from water. To meet these requirements, an integration of metal oxides, which facilitate water splitting, and zero‐valent metals, which provide active sites for hydrogen adsorption, can be employed.[ 11 ] These approaches not only enable bifunctional capabilities, allowing a single catalyst to be effective across a range of reactions or at both the anode and cathode, but also harness the synergistic effects at the material interfaces, thereby overcoming the limitations of individual components. Additionally, fast electron transfer kinetics associated with heterostructure catalysts can enhance their durability. This improvement derived from the heterostructure catalysts can lead to more efficient and long‐lasting performance during electrochemical reactions.[ 12 ]

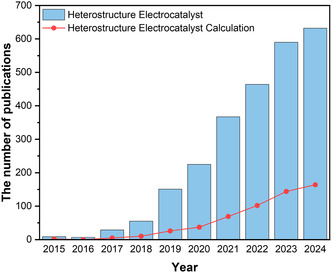

To further enhance the potential of heterostructured catalysts, it is imperative to thoroughly understand their characteristics and identify the key factors influencing their catalytic performance. Characterization techniques such as transition electron microscopy (TEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), X‐ray diffraction, UV–vis spectroscopy, and X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provide critical insights into the structural, optical, and electronic features of these catalysts. These techniques facilitate assertions regarding their composition, surface facets, oxidation states, and morphological characteristics. Furthermore, heterostructures exhibit complex systems where multiple materials interact simultaneously, making in situ and operando spectroscopy essential for observing real‐time characteristics.[ 13 ] For example, in situ microscopy, including AFM, TEM, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), can characterize mechanical properties and deformation process, even for materials with small size and thickness.[ 14 ] In situ Raman spectroscopy enables monitoring of reaction intermediates and structural changes in real time.[ 15 ] Additionally, operando X‐ray absorption spectroscopy elucidates oxidation states and local bonding configuration on an elemental basis.[ 13 ] Despite advancements in these characterization methods, directly capturing reaction mechanisms at the atomic level remains a challenge. Specifically, it is difficult to observe electron transfer and charge distribution at interfaces, particularly during rapid electrochemical reactions or complex multistep processes. Relying solely on experimental observations can be limiting, particularly in the study of complex heterostructured electrocatalysts with numerous variables. Therefore, a collaborative approach that integrates experimental methods with computational materials science is necessary. Computational materials science has emerged as a crucial methodology, offering insights that experiments alone cannot achieve. It complements experimental challenges and suggests novel catalysts that have yet to be revealed. In line with this, research combining experimental methods with computational analysis on heterostructured catalysts has become increasingly prevalent.[ 16 ] Advances in computing power have made it feasible to implement methodologies such as density functional theory (DFT), molecular dynamics (MD), and machine learning (ML). Especially, computational materials science plays a vital role by enabling the identification of active sites and mechanisms at the atomic level, thus determining the key factors that drive the progress of electrocatalysts. DFT allows for the analysis of charge transfer and electron localization function (ELF) at heterointerfaces, providing insights into electron distribution tendencies. It can also analyze work function differences that affect the directions of electron transfer and the formation of Schottky barrier. MD can examine time‐dependent interactions between molecules and the catalyst on a larger scale, offering information such as diffusion coefficient and ionic conductivity. ML is particularly advantageous for a broad exploration of diverse material groups by considering various factors. For instance, in 2D material heterostructures, it can consider variables such as rotation angles between stacking layers, interlayer spacing, and bandgap differences.[ 16 ] These methods facilitate a comprehensive analysis and suggest optimal combinations that would be challenging to achieve through experiments. Therefore, the collaboration between computational and experimental approaches has become indispensable in the research of heterostructured electrocatalysts. Computational materials scientists can reveal the underlying properties of experimentally synthesized heterostructures and propose new designs that can be validated by experimentalists. Such collaborations will expedite the development of high‐performance heterostructured electrocatalysts. The increasing number of publications on “Heterostructure Electrocatalyst” and “Heterostructure Electrocatalyst Calculation” during the last 10 years (from 2015 to 2024) demonstrates the noticeable interest and research activity in these topics (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

The number of publications on the topics of “Heterostructure Electrocatalyst” and “Heterostructure Electrocatalyst Calculation” from 2015 to 2024. The data for this graph were sourced from the Web of Science on January 1, 2025.

Despite the myriad benefits of computational methods in exploring complex material systems and optimizing the catalytic performance, these methods face certain limitations. Constructing the precise heterostructure is significant in the computational approaches, yet it often relies on the researcher's individual judgment and becomes challenging due to the consideration of various variables. The absence of standardized protocols for computational analysis further complicates the process. As a result, the unique challenges in constructing heterostructured electrocatalysts necessitate systematic approaches. For example, discerning the appropriate heterostructure type depends on accurately pinpointing the active sites within the surface model of heterostructures. Implementing appropriate lattice strain is important, as the combination of materials with different lattice constants can affect the catalysts’ characteristics.[ 17 ] It is also crucial to implement moderate mismatch levels that minimize lattice strain to ensure synthesizability and prevent the distortion of material properties. Furthermore, it is pivotal to carefully evaluate the stability of heterostructures and consider the phase changes and defect formation during electrochemical reactions, as these factors significantly impact the catalytic performance of heterostructures. [9c] Given these complexities, a systematic approach is necessary to effectively model heterostructured electrocatalysts. Although there have been review articles on specific material groups, electrochemical reactions, experimental methods, and general computational methods for electrocatalysts, comprehensive reviews on practical computational methodologies for heterostructured electrocatalysts are not sufficient. This review aims to categorize the heterostructure types and present the systematic evaluation approaches of stability and activity, thus facilitating the integration of computational methodologies into heterostructure systems. Furthermore, we will introduce the extensive applications of heterostructures across various electrochemical reactions, including OER, HER, ORR, CO2RR, NRR, and UOR by focusing on the activity descriptors. Through an examination of current computational research, this review endeavors to advance the modeling and analysis of heterostructured electrocatalysts.

2. Construction of Heterostructure for Computational Modeling

2.1. Heterostructure Modeling Types

Heterostructures are formed by combining two materials with different compositions and lattice constants. These structures can be categorized either by their stacking direction into vertical and lateral heterostructures or by their bonding type into van der Waals (vdW) and covalent heterostructures.[ 18 ] Additionally, heterostructures can be classified based on the materials’ dimensionality—ranging from 0D, 1D, 2D, to 3D.[ 9 , 19 ] Moreover, they can be further differentiated by their phase and electrical properties, such as amorphous–crystalline and metal–semiconductor heterostructures.[ 8 , 20 ] Therefore, the classification of heterostructures can be diverse, considering factors like stacking methods, bonding types, material dimensions, and materials’ properties. On the other hand, in computational modeling, it is required to consider not only these categories but also the distinct factor inherent to computational materials science. Periodic boundary condition enables the efficient simulation of catalyst within a unit cell by repeating models to represent a large and infinite system. However, due to the intrinsic nature of this system, computational models do not directly correspond to experimental morphologies or structures in a single and definite way. Heterostructures can be constructed in a variety of ways with the periodic system. This flexibility allows researchers to select the most suitable model structure based on the specific characteristics, especially the target active sites. Therefore, computational materials scientists should carefully consider the construction factors from multiple perspectives. For a systematic approach in computational materials science, we refined the existing heterostructure types by considering the stacking direction and the degree of interaction at the interfaces, whether fully or partially interacting (Graphical Abstract). We specifically focused on the periodic unit cell system, where one material's structure is optimized to match the lattice constant of another. In addition, computational modeling requires a vacuum to analyze adsorption energy and activation barriers on the surface, as it prevents interactions between unit cells along a specific axis, which is essential for understanding catalytic activity. Without a vacuum, distinguishing vertical and lateral heterostructures becomes more complicated. Therefore, to focus on surface reaction mechanisms, we restricted our categorization to systems with a vacuum. With these frameworks, we introduced three computational heterostructure model types: vertical, semivertical, and lateral. These classifications are formulated to provide a comprehensive basis for modeling heterostructures. The characteristics of these three heterostructure types have been summarized to provide insights into selecting the most appropriate model.

2.1.1. Vertical Heterostructure

Constructing vertical heterostructure involves stacking materials vertically, enabling the entire surface of materials to interact with each other. In this configuration, each material is periodically repeated along two axes, forming distinct layers. A defining feature of vertical heterostructure is that one material completely covers the surface of another. This structure type is widely used due to its ability to facilitate full interlayer interactions between the materials.

In the vertical heterostructure modeling, the active sites are generally located in the overlying materials. This modeling approach is effective for analyzing catalysts with well‐defined active sites. This concept can be utilized to investigate the synergistic effects between materials at the exposed surface. To begin with, this structure can be used to study how conductive materials enhance the electrical conductivity of 2D materials. Back et al. harnessed the high stability of hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) as an ORR catalyst and sought to improve its conductivity by forming heterostructures with metals. They constructed vertical heterostructures using DFT, focusing on hBN to thoroughly elucidate how its electronic structure and catalytic activity were altered by the influence of the metal supports and the vacancy formation.[ 21 ] This strategy has been widely reported for studying the influence of metal supports on hBN in ORR and HER, utilizing vertical heterostructures.[ 22 ] This approach demonstrates the effectiveness of vertical heterostructure in providing a detailed analysis of active sites within the overlying layer. Another example involves the vertical heterostructures to analyze the increase in conductivity of TM dichalcogenides (TMDs), which are widely used in electrocatalysts due to their electronic tunability. When MoSe2 was supported on La1–x Sr x CoO3–δ (LSC), the vertical heterostructure modeling effectively exhibited that the phase transition from the 2H phase to the more conductive 1T phase was facilitated, allowing for better OER and HER activity (Figure 2a).[ 23 ] This demonstrates that vertical heterostructure efficiently revealed electronic properties and analyzed the ease of phase transitions at the overlying active sites.

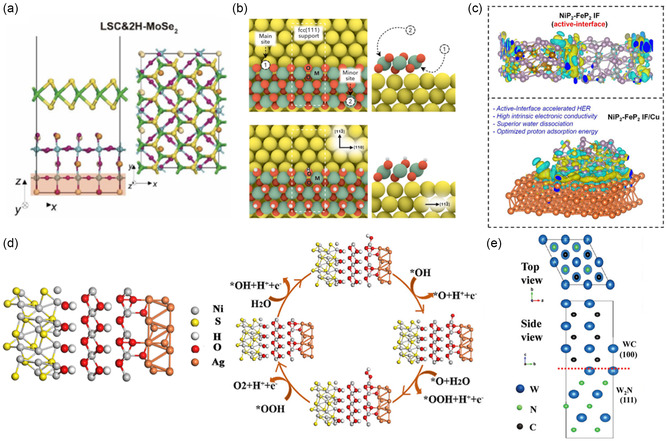

Figure 2.

a) Vertical heterostructure modeling of 2H‐MoSe2/La0.5Sr0.5CoO3−δ (LSC). Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 23 ] b) Semivertical heterostructure modeling of nanoribbon of MOOH on noble metal (M = Ni, Fe, Co, Mn; noble metal = Pt, Ag, Au). Reproduced with permission.[ 34 ] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. c) Combination of lateral heterostructure and semivertical modeling of NiP2‐FeP2/Cu. Reproduced with permission.[ 42 ] Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. d) Lateral heterostructure modeling of NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2. Reproduced with permission.[ 45 ] Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. e) Lattice mismatch minimization for epitaxial growth of WC/W2N. Reproduced with permission.[ 55 ] Copyright 2019, WILEY‐VCH GmbH.

Beyond these examples, vertical heterostructures have been widely applied to core–shell, encapsulated, and multimaterial catalysts, effectively elucidating how changes in active sites influence catalytic performance. Seenivasan et al. proposed a catalyst composed of a NiCo2S4 core and NiS nanoshell. The interaction between NiCo2S4 and NiS not only increased the number of active sites but also constructed a rough surface. This study effectively analyzed the OER and HER mechanisms by considering NiS as the active site. By modeling the deformation and interaction of these catalysts, this study provided notable insights into the role of NiS as the active site.[ 24 ] In addition, a catalyst, synthesized through a two‐step hydrothermal reaction, formed a CoOOH nanosheet on Ni2P. The vertical stacking of two materials, with CoOOH considered as the active site, facilitated the analysis of OER mechanism.[ 25 ] Furthermore, a strategy involving a TM phosphide encapsulated by N‐doped carbon was utilized to enhance alkaline HER activity. Vertical heterostructures were employed to explain the improved activity of MoP. Calculations confirmed that especially pyridinic N, compared to pyrrolic and graphitic N, played a critical role in water dissociation and hydrogen adsorption.[ 26 ] Finally, the synergistic effects of cobalt's different oxidation states were demonstrated when cobalt oxide was present in two phases supported by carbon. By comparing Co3O4/CoO/C with Co3O4/C and calculating ORR mechanism specifically at the active site of Co3O4, the researchers effectively leveraged vertical heterostructure in a multilayer configuration.[ 27 ] These findings highlight the versatility of vertical heterostructure construction in capturing full material interactions and uncovering the distinct characteristics of overlying active sites across diverse electrocatalyst morphologies.

Furthermore, vertical heterostructure is valuable in studying surface‐reconstructed electrocatalysts, particularly those with activated LDH or oxyhydroxides as active sites. When precatalysts are exposed to high‐pH alkaline electrolytes, they undergo surface reconstruction into (oxy)hydroxides.[ 28 ] For example, FeNi alloy and FeNi oxyhydroxide vertical heterostructure were constructed to investigate the surface reconstruction of Fe0.4Ni0.6 alloys, comparing the OER activity of Ni/NiOOH and explaining the role of Fe incorporation.[ 29 ] Another study utilized vertical heterostructures to examine the OER activity of surface reconstructed catalysts in Ni3N/Ni core with an ultrathin Ni3N shell. This study focused on NiOOH as the active sites in the vertical heterostructures of Ni@NiOOH and Ni3N@NiOOH.[ 30 ] Similarly, research was conducted on the core–shell‐like structure formed by the surface reconstruction of NiCoMoN during electrochemical reaction. By comparing the OER activity of isolated NiCoOOH with that of the NiCoOOH/NiCoMoN vertical heterostructure, the superior OER activity of the heterostructure was demonstrated through DFT calculations. In this study, the vertical heterostructure effectively explained how the catalytic activity changes depending on the presence of the nitride, with NiCoOOH serving as the active site.[ 31 ] This approach enables detailed comparisons of catalytic activity and reaction mechanisms in the (oxy)hydroxide phases. Vertical heterostructure effectively investigates the synergistic effects between supporting precatalysts and activated (oxy)hydroxides, facilitating in‐depth analysis of the covering material.

In vertical heterostructures, it is also possible for both the overlayer and the underlying material to serve as active sites in the opposite direction for catalytic reactions, especially when dealing with 2D materials or thin films. This is feasible because, in computational simulations, the bottom layers of the underlying material, especially for thick layers like 3D materials, are typically fixed to represent bulk properties, but the thin or 2D layers are generally fully relaxed to accurately capture surface or interface behaviors. As a result, vertical heterostructures involving only such 2D materials allow both components to act as active sites in the opposite direction. For instance, a 2D–2D heterointerface using Pt nanodendrite and NiFe LDH was examined for a HER catalyst. Pt contributed to hydrogen adsorption, while NiFe LDH facilitated water dissociation. The vertical heterostructure of 2D Pt(110) and NiFe LDH(001) revealed the electron depletion in NiFe LDH compared to its isolation model, making it more favorable for water and OH adsorption. At the same time, Pt in the heterostructure exhibited stronger dissociated water adsorption energy, indicating that the formation of the heterostructure with NiFe LDH enhanced its water dissociation ability. This example highlights the use of vertical heterostructure design to explore adsorptions at the outer surfaces of both materials, confirming that both can function as active sites.[ 32 ] Additionally, a self‐assembled double‐heterojunction electrocatalyst of NiS2/Ni3C@C was analyzed by separating it into two vertical heterostructures: Ni3C/C and NiS2/Ni3C. The Ni3C/C interface exhibited efficient charge and mass transfer abilities through electronic structure analysis. To further analyze HER activity, NiS2/Ni3C was compared to individual NiS2 and Ni3C, with the adsorption site located at the interspace between two materials. This demonstrates that vertical heterostructure can effectively differentiate and analyze interfacial regions that significantly influence catalytic activity, while also considering adsorption sites at the interspace.[ 33 ] Hence, these instances illustrate that vertical heterostructures can also efficiently utilize both overlayer and underlying materials as active sites, depending on the specific materials and research objectives.

2.1.2. Semivertical Heterostructure

Semivertical heterostructure refers to a structure where two materials are vertically stacked, but one material partially covers the other. This strategic overlap ensures that the surfaces of both materials remain exposed in the same direction. Unlike the vertical heterostructure, in a semivertical heterostructure, the covering material is periodically repeated along only one axis, allowing both overlayer and underlying materials to remain accessible at the surface. This type facilitates the investigation of catalytic properties of each material while enabling in‐depth examinations of the direct interactions at their interface.

Semivertical heterostructure is useful for analyzing the edge sites of the covering material, which can serve as potent active sites. For example, Back et al. modeled nanoribbons of TM‐based oxides and oxyhydroxides on noble metals to improve the stability and ORR activity during electrochemical reactions (Figure 2b). TM oxides and oxyhydroxides of Co, Fe, Mn, and Ni were established with a single layer, while Ag, Au, and Pt served as support metals. Through semivertical heterostructure, the edge sites of these oxyhydroxides and oxides were exposed, allowing adsorbates to interact with both the supporting metals and the covering oxides. They distinguished between the main sites at the interface of the support and nanoribbons and the minor sites at the edge sites of the nanoribbons.[ 34 ] Likewise, Wen et al. employed this heterostructure type for the Schottky heterojunction formed by nanosheet NiS and NiFe hydroxide. They constructed the heterostructure with NiFe LDH covering O‐doped NiS and conducted OER mechanism calculations at the edge sites of the LDH. This approach efficiently helped to study the edge sites of hydroxide in semivertical heterostructure electrocatalysts.[ 35 ] Therefore, under periodic boundary conditions, semivertical heterostructure can be employed to model catalysts where the edge sites of the covering material are exposed by optimizing its periodicity along one axis.

Another important approach with semivertical heterostructure is the investigation of interfaces where both materials form direct bonds. A noticeable feature of semivertical heterostructure is their ability to calculate reaction mechanisms at these interfaces with direct bonds, providing insights into how both materials contribute to catalytic activity. For example, Kavinkumar et al. proposed a W2N3/Fe2N system for water electrolysis, using semivertical heterostructure to form a conductive interface between coral‐like 3D Fe2N and 2D W2N3 nanosheets. They calculated the water splitting kinetics, highlighting enhanced HER activity of the semivertical heterostructure compared to individual Fe2N.[ 36 ] Furthermore, a combination of semivertical heterostructure and a unique strategy was applied to simulate and analyze strong electronic coupling in an alkaline HER catalyst. By partially placing a NiHO layer on Ni2P(111), You et al. investigated the interaction at various adsorption sites, including the edge sites of NiHO, the NiHO/Ni2P interface, and the surface of Ni2P. Additionally, to investigate the effect of a more negative charge on the catalytic performance of Ni2P, they substituted part of the Ni2P layer with NiHO. This unique approach led to increased electron accumulation on Ni2P, and DFT calculations revealed that the negatively charged phosphide significantly enhanced HER activity. They illustrated their novel approach to introducing negative charge.[ 37 ] In addition to this example, Zhai et al. used semivertical heterostructure and atom replacement to explore the synergy between bimetallic oxide and sulfide. They established a Ni3S2/MoS2 semivertical heterostructure where a 2D nanosheet formed an interface with a 1D nanorod. To simulate oxides, they substituted sulfur atom at the interface of MoS2 edge and Ni3S2 surface with oxygen atom and created a NiMoOx/NiMoS catalyst. This structure showed the thermoneutral hydrogen adsorption energy and a lower OER overpotential compared to the Ni3S2/MoS2 system. They suggested that the combination of Ni and Mo in this heterostructure enhanced bifunctional catalytic activity.[ 38 ] Similarly, Chen et al. applied semivertical heterostructure to model a heterostructure composed of tungsten (W) nanoparticles and WO2 nanorods, another example of a system incorporating 1D material. High‐magnification SEM and energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy confirmed the 1D nanorod structure. In this system, WO2 acted as a Lewis acid, facilitating water adsorption, dissociation, and proton storage, while W served as a Brønsted acid site for proton desorption. Constructing the semivertical heterostructure suggested the synergistic effects of W and WO2 on water dissociation and hydrogen adsorption/desorption at their interface in an alkaline environment.[ 39 ] This approach is particularly useful for elucidating the distinct roles of each material by highlighting their contributions within the heterostructure. By optimizing the heterostructure with diverse strategies and periodicity along a single axis, utilizing semivertical heterostructure facilitates catalyst investigation by identifying the active sites where both materials bond and distinguishing the role of each material.

2.1.3. Lateral Heterostructure

Lateral heterostructure involves the horizontal stacking of materials, creating laterally repeated structures. Similar to the semivertical heterostructure, both materials’ surfaces remain exposed, allowing active sites to be accessible. The primary distinction between lateral and semivertical heterostructure lies in the orientation of the stacking, which affects the nature of the material interactions. Unlike semivertical heterostructure, where interactions may be confined to specific regions of overlying materials, lateral heterostructure design ensures that materials interact fully along their interfaces. This is particularly advantageous in systems where materials have comparable thickness, whether in 2D or 3D configurations. Furthermore, when periodic boundary conditions are applied to lateral heterostructures, they allow the exploration of edge sites from both materials in 2D structures. In contrast, for vertical heterostructures, the continuous distinct layers make it difficult to expose the edge sites. As a result, it becomes harder to examine edge‐specific properties in vertical heterostructures, whereas lateral heterostructures provide better access to all edge sites for analysis. This flexibility enables the analysis of systems while ensuring all edge sites of the materials remain accessible for evaluation.

Lateral heterostructure has been employed to pinpoint the roles of each material by exposing both materials as active sites. For alkaline HER electrocatalysts, integrating metal oxides and metals is an effective strategy to enhance water dissociation and hydrogen adsorption/desorption capabilities. Zhu et al. applied lateral heterostructure to simulate Pt single atom supported on Ru/RuO2. In this structure, Pt, Ru, and RuO2 sites were distinguished and analyzed by arranging Ru and RuO2 laterally to expose both materials on the surface. This approach aided in the identification of appropriate materials for distinct roles.[ 40 ] Furthermore, combining lateral and semivertical heterostructures has proven effective in considering multiple materials and clarifying the effects of each material. For instance, a study analyzed the impact of the Ru2P/WO3 lateral interface on N‐ and P‐codoped carbon as an alkaline HER catalyst. This approach utilized Ru2P, known for enhancing electrical conductivity through carbon materials, and WO3, which was introduced to facilitate water adsorption. The modeling utilized the lateral heterostructure of Ru2P and WO3 with a vertical construction for the carbon material. This approach revealed how N and P codoping in carbon improved the electronic conductivity of Ru2P/WO3. It also disclosed the roles of WO3 in water adsorption and dissociation, and Ru2P in hydrogen desorption, demonstrating the effectiveness of the lateral heterostructure.[ 41 ] Similarly, Kumar et al. utilized an approach integrating the lateral heterostructure of NiP2 and FeP2 with the semivertical heterostructure on Cu(111) for alkaline HER. Specifically, to construct the interface of NiP2 and FeP2 laterally, they used five layers of NiP2(210) and FeP2(101), minimizing the interfacial strain. To account for the Cu nanosheet, the NiP2/FeP2 heterostructure was semivertically bound on Cu(111) (Figure 2c).[ 42 ] Consequently, utilizing combinations of different heterostructure types enables researchers to adapt their methodologies to specific research objectives and achieve a more comprehensive understanding.

Lateral heterostructure keeps both materials exposed, yet researchers can still focus on the reaction mechanisms of a specific active site when it is clearly identified. For example, a catalyst composed of NiFe selenide and NiFe(OH) x was suggested as a crystalline–amorphous heterostructure. This catalyst was synthesized by electrodepositing an amorphous NiFe(OH) x shell onto a crystalline selenide core. The computational lateral heterostructure was examined to understand how the presence of selenide influenced the activity of NiFeOOH. While core–shell catalysts were previously introduced with the vertical heterostructure, this system was implemented using lateral heterostructure and specifically focused on the activity of NiFeOOH.[ 43 ] In addition, lateral heterostructure can also be applied to simulate lamellar structures. One example involves a catalyst consisting of CoFe molten alloy and CeO2−x N x , which underwent surface reconstruction during electrochemical reaction. To model the transformation of CoFe into CoFeOOH and the formation of an amorphous phase, ab initio MD (AIMD) was employed. This study further evaluated the effect of nitrogen doping in CeO2 by comparing the structures of CoFeOOH, CoFeOOH/CeO2, and CoFeOOH/CeO2−x N x . They investigated Co within CoFeOOH as the active site for OER mechanism.[ 44 ] In another example, Ag nanoparticles were deposited on a Ni3S2 nanosheet, leading to the formation of amorphous NiOOH. The model, which laterally bonded NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2, revealed the improved OER activity at the edge site of NiOOH due to Ag nanoparticles (Figure 2d).[ 45 ] Additionally, lateral heterostructure facilitated the design of FeS2/Fe‐doped Ni3S2 heterostructure formed through F− ion engineering and Fe doping. This study highlighted the importance of lattice‐matching growth, with a comparative analysis of the OER and HER activity of FeS2, Ni3S2, and the FeS2/Ni3S2 heterostructure demonstrating synergistic effects at the adsorption sites near the interface.[ 46 ] Therefore, these studies have presented how lateral heterostructures can be employed to analyze activity changes when the specific active site forms a heterostructure. Although experimental morphologies appear similar, computational heterostructure types can be selected based on periodic boundary conditions and active sites.

Next, in lateral heterostructures composed of 2D materials, direct covalent bonding between the materials is possible, effectively impacting electronic structures. Hu et al. compared the lateral heterostructures of graphene and hBN, focusing on C—B interface and C—N interface. They found that graphene served as a more effective HER active site compared to hBN in the heterostructures. Specifically, the carbon atom at the C—B interface exhibited the highest HER activity, outperforming both individual graphene and hBN.[ 47 ] In addition, lateral heterostructure can be applied to vdW heterostructures. This strategy is particularly advantageous for analyzing edge sites of both 2D materials. Yu et al. utilized this strategy to analyze the increased interspacing of MoS2 in MoS2/graphene vdW heterostructure, induced by the introduction of graphene. This introduction of graphene significantly enhanced the advantages of MoS2's single‐layer properties, improving electrical conductivity. Moreover, this approach allowed them to examine the activity of the edge site, which is known for its effectiveness as an active site with high conductivity.[ 48 ] Lateral heterostructure has also been used to examine heterostructures formed through surface reconstruction. In a study of Ru‐doped NiFe2O4 on a NiMoO4 nanowire, researchers have investigated the effects of Ru doping on the NiFeOOH/NiOOH heterostructure. They arranged the oxyhydroxide laterally, exposing the edge sites on the surface and calculating the OER activity.[ 49 ] In summary, lateral heterostructure is a versatile approach, as evidenced by its applications in various electrocatalyst configurations. When combined with semivertical heterostructure modeling, it has shown to be applicable across a range of configurations. These examples also highlight that even for similarly characterized electrocatalysts, including core–shell structures, surface reconstructions, and vdW heterostructures, the construction of computational structures can depend on the specific active sites and research objectives. The relative orientation of the vacuum and surface is particularly important when analyzing edge site activity. These insights into the computational strategies of structure construction provide a foundation for the systematic integration of materials into heterostructured electrocatalyst research.

2.2. Lattice Strain Optimization

Computational simulations typically employ periodic boundary conditions to efficiently mimic the infinite nature of real systems in computational finite systems. However, the integration of materials with different lattice constants inherently leads to lattice mismatch, which can significantly influence the catalytic performance of the system.[ 17 ] This mismatch creates strain that can alter the structural and electronic properties of the materials.[ 50 ] Additionally, this mismatch forces the materials to either stretch (tensile strain) or compress (compressive strain), creating artificial strains that must be optimized to prevent distorted predictions of material behavior. If lattice strain is not properly managed, the simulated properties, such as bond lengths, adsorption energies, and catalytic activity, may be inaccurately represented, leading to overestimated or underestimated results compared to real experimental data. Therefore, to accurately simulate experimental conditions, it is essential to carefully optimize the strain introduced by computational modeling with periodic boundary conditions.[ 51 ] In addition, optimizing the lattice strain in computational models is crucial for ensuring that the simulation accurately reflects the corresponding experimental conditions.

Lattice strain is defined as the ratio of the change in length to the original length of a material. In a heterostructure consisting of materials A and B, each material is compressed or relaxed to match the lattice constant of the unit cell, that of optimized heterostructure. The lattice strain of material A is calculated by the formula

| (1) |

where is the lattice strain on material A, is the lattice constant of material A, and is the lattice constant of the optimized heterostructure. The same equation applies to material B. If the lattice strain is positive, tensile strain occurs; if it is negative, compressive strain occurs. In some contexts, tensile and compressive strain are described without explicitly stating positive or negative signs.

For modeling appropriate lattice strain through computational methods, efforts are being undertaken to accurately replicate experimental conditions without distorting the materials’ properties. Zhou et al. proposed a bifunctional catalyst for ORR and HER by modeling the heterostructure using MXene and N‐doped graphene with high electrical conductivity, optimizing each material to achieve a lattice strain smaller than 2.12%. They confirmed that the 1.81% tensile strain and 2.12% compressive strain on the graphitic layer were negligible in terms of binding energy and catalytic activity.[ 52 ] Liu et al. introduced a core–shell OER catalyst utilizing amorphous NiFe oxides and crystalline (Ni,Fe) selenides to enhance the bimetallic effect and the electrical conductivity of oxyhydroxide. They modeled a heterostructure considering that NiFe oxide and hydroxide transform into NiFeOOH during electrochemical reactions. The (110) facet of NiFeOOH was used to minimize interfacial mismatch with (Ni,Fe)Se2(100), showing a small lattice strain of 0.54%.[ 43 ] Additionally, Wang et al. synthesized an alkaline OER catalyst by decorating Ni foam (NF) with Ag nanoparticles and constructing a heterostructure with Ni3S2. To analyze the Ag/Ni3S2/NF catalyst, they modeled the heterostructure with NiOOH, which was activated during the operating condition. The presence of NiOOH was confirmed through high‐resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and in situ Raman spectroscopy. They determined each facet of the heterostructure as NiOOH(001), Ag(111), and Ni3S2(001) to minimize lattice strain (Figure 2d).[ 45 ] Finally, Hu et al. modeled a lateral heterostructure using the 2D materials hBN and graphene with covalent bonding, proposing its potential as a HER catalyst. The precise matching of lattice constants was essential for forming this heterostructure. hBN and graphene exhibit only a 1.7% lattice mismatch, making them suitable candidates.[ 47 ] In numerous heterostructure studies, minimizing lattice mismatch between materials has been repeatedly emphasized as crucial for accurately predicting catalytic behavior and performance. Using accurate modeling techniques and quantifying lattice mismatch, researchers have been able to replicate results closely, demonstrating the importance of well‐optimized lattice strain in achieving reliable simulations.

Optimizing lattice strain in computational models is also critical for accurately predicting synthesis feasibility, particularly in epitaxial growth.[ 53 ] When forming a heterostructure using the epitaxial growth method, it is essential to have nearly identical lattice constants.[ 54 ] Calculating lattice strain helps evaluate the feasibility of experimental synthesis. For example, Diao et al. modeled a W2N/WC heterostructure with 0.59% interfacial strain for trifunctional electrocatalysis (ORR, OER, and HER). In an alkaline environment, WC exhibits Pt‐like characteristics for HER, while W2N is effective for OER and ORR. With identical lattice constants of a = b = 2.238 Å for W2N(111) and WC(100), the strain is negligible when WC grows along the [111] direction of W2N (Figure 2e). Results confirmed that the synthesized catalyst matched computational predictions, forming the same facets.[ 55 ] Moreover, Liang et al. suggested that epitaxial growth of pristine NiPS3 could improve catalytic activity by forming a heterostructure with Ni2P. Although NiPS3 alone was not suitable for HER, its combination with Ni2P showed promising electrocatalytic potential. The hexagonal Ni2P(001) with a = b = 5.81 Å matches well with the NiPS3(001) facet with a = b = 5.85 Å, resulting in a lattice strain of 0.69% lattice strain. This proved the feasibility of epitaxial growth of Ni2P on NiPS3.[ 56 ] These studies underscore the importance of predicting strain effects in heterostructures through calculations and present the potential for experimental synthesis. Additionally, lateral epitaxial growth requires matching lattice constants to minimize the interfacial energy.[ 57 ] As demonstrated in these studies, the accurate prediction and optimization of lattice strain are the key to bridging computational models with experimental realities. Optimizing lattice strain not only stabilizes interfacial energy but also aids in assessing synthesizability.

3. Structural Stability Analysis

3.1. Interfacial Binding Energy

Interfacial binding energy is a significant parameter in the design and optimization of heterostructures, providing insights into the stability of the resulting heterostructure. This energy quantifies the interaction between different materials at their interface and can be calculated using the equation.

| (2) |

where E b is the binding energy, E A/B represents the total energy of the heterostructure, and E A and E B are the total energies of the isolated materials A and B, respectively. A more negative E b indicates a thermodynamically favorable interaction, suggesting that the formation of the heterostructure is energetically preferable.

Understanding interfacial binding energy is essential for evaluating the structural integrity and the stability of heterostructured catalysts. Strong interfacial interactions with more negative binding energies enhance the stability of the heterostructures under operational conditions. These interactions can lead to charge redistribution, potentially creating unique active sites for electrocatalysis. This can influence catalytic activity by altering the adsorption energies of reactants and intermediates, thereby optimizing reaction kinetics and overall catalytic efficiency. Accurate computation of interfacial binding energy requires careful consideration of exchange‐correlation functionals, atomic precision, and vdW interactions. By tailoring materials and engineering interfaces to optimize binding energy, researchers can develop catalysts with improved stability, activity, and selectivity for applications in energy conversion, environmental remediation, and chemical synthesis.

Interfacial binding energy functions as a benchmark for assessing stability, stacking configuration, and bonding states of heterostructured materials. Ge et al. extensively studied 2D dichalcogenide heterojunctions composed of MX2 (M = Mo, W; X = S, Se, Te) and revealed how binding energy varies with rotational angles. They found that the MoTe2/WTe2 heterojunction had the most stable interfacial binding energy of −4.46 eV at a 300° rotational angle, while the MoS2/WS2 heterojunction showed the weakest interfacial binding energy of −1.77 eV without rotation. This study concluded that eight types of heterostructures generally exhibited stable binding energy at a 180° rotational angle, where interactions occur between metal and nonmetal elements in each layer. A strong correlation between binding energy and layer spacing was observed. The layer spacing tended to decrease at rotational angles greater than 180° before returning to its original state. This analysis highlights the importance of optimizing stacking angles to achieve stable binding energy in the modeling of 2D material‐based heterostructures (Figure 3a).[ 58 ] Santos et al. compared the binding energies associated with different terminations of a support material in a heterostructure. In the MoS2(100)/InAs(111) system, they found that the In‐terminated support was 5.574 eV more stable than the As‐terminated one. The study explained that In atoms tend to move closer to the MoS2 layer in the process of relaxation, resulting in a shorter average distance and stronger interaction compared to As—S interaction. Consequently, they reported that the MoS2 film interacts more strongly when the support has an In termination.[ 59 ] Based on these studies, it is evident that interfacial binding energy is influenced by several factors, including interlayer spacing, rotational angles between layers, and terminations of materials. Therefore, by identifying thermodynamically stable configurations, researchers can simulate optimal structures for enhancing catalytic stability and investigating unique interfacial properties.

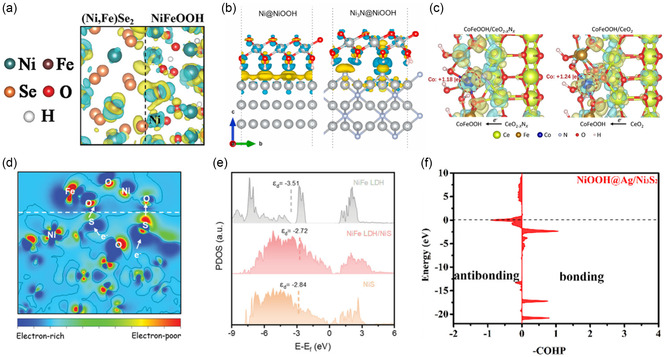

Figure 3.

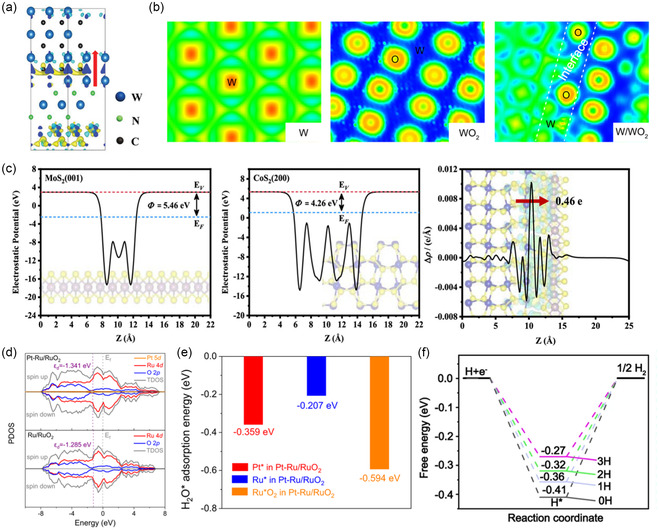

a) Interfacial binding energy based on the angle between 2D TMDs. Reproduced with permission.[ 58 ] Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. b) Normalized interfacial binding energy of graphene/MoS2 dependent on the number of carbon atoms in graphene. Reproduced under the terms of Creative Commons CC BY‐NC 3.0 license.[ 60 ] c) Normalized interfacial binding energy between MO2, MOOH, and noble metal depending on the number of oxide units. Reproduced with permission.[ 34 ] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. d) Formation energy normalized by the number of added oxygen atoms. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.[ 63 ] e) Vacancy formation energy of anions B and N in hBN/Metal heterostructure. The dashed line represents the standalone hBN surface. Reproduced under the terms of Creative Commons CC BY‐NC 3.0 license.[ 21 ] f) Vacancy formation energy of metal Ni and bond length in NiOOH@Ni3S2 and NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2. Reproduced with permission.[ 45 ] Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

3.2. Normalized Interfacial Binding Energy

When evaluating interfacial binding energy across different systems, normalization becomes important to account for variations in model sizes and interacting surface areas. As the size of the model increases, the binding energy may also increase due to larger interacting areas. Hence, normalization is necessary to accurately compare interfacial interactions. This can be achieved by standardizing the binding energy based on the number of specific atoms or compound units in the system, as described by the following equation.

| (3) |

where E normalized b represents the normalized binding energy, E A/B is the total energy of the heterostructure, N i is the number of referenced atoms or compound units, and E A and E B are the total energies of the isolated materials A and B, respectively.

In heterostructures involving carbon‐based materials such as graphene, the interfacial binding energy is commonly normalized by the number of carbon atoms due to the uniform structure and single‐element composition. Fang et al. optimized a graphene/MoS2 heterostructure using the Buckingham potential, which relates the interlayer spacing of the top sulfur atom in MoS2 to graphene with the binding energy. They demonstrated a normalized interfacial binding energy of −39 meV C−1 atom with a 3.414 Å gap between MoS2 and graphene (Figure 3b). This optimization is crucial for stable normalized interfacial binding energy in vdW heterostructures. Furthermore, they observed that positive biaxial strain (tensile strain) weakened the interaction between MoS2 and graphene by increasing the spacing. This study highlights the importance of minimizing and optimizing lattice strain to achieve stable normalized interfacial binding energy.[ 60 ] Similarly, Zhou et al. investigated the binding energy between N‐doped graphene and various MXenes in vertical heterostructures. They reported interlayer displacements of 2.08 to 2.40 Å and binding energies of −0.42 eV C−1 atom for N‐doped graphene on Ti2C, −0.32 eV C−1 atom for N‐doped graphene on V2C, −0.25 eV C−1 atom for N‐doped graphene on Nb2C, and −0.23 eV C−1 atom for N‐doped graphene on Mo2C. These results confirmed strong interfacial interactions and significant charge transfers. Therefore, optimizing interlayer distances and normalized interfacial binding energy is essential for accurate modeling and understanding of electronic structures.[ 52 ] Additionally, N‐doped graphene with metallic surfaces of Co(111) and Fe(110) exhibited normalized interfacial binding energies of −0.10 and −0.16 eV C−1 atom, respectively.[ 61 ] Comparing the normalized interfacial binding energy of N‐doped graphene with MXenes and metal supports helps identify more stable heterostructures. This method also allows for effective comparisons across different systems, even when model sizes vary depending on the support materials during lattice strain optimization. The previous examples focused on carbon‐based materials, such as graphene. On the other hand, modeling heterostructures involving compounds also utilizes this method for evaluating stability. Back et al. compared the interaction between (oxy‐hydro)oxide nanoribbons and face‐centered cubic (FCC) metals by normalizing the binding energy with respect to the number of (oxy‐hydro)oxide units (Figure 3c). They found that Pt exhibited the most stable normalized interfacial binding energy, followed by Ag and Au. This stability trend is explained by the increasing oxophilicity of the support metals and the proximity of their d‐bands to the Fermi level, moving from Au to Pt.[ 34 ] This approach demonstrates the effectiveness of normalization for comparing different systems, even when model sizes and compositions vary.

3.3. Formation Energy

In the previous section, we introduced (normalized) interfacial binding energy to understand the bonding interactions between pristine materials. This section focuses on formation energy, which is essential for evaluating surface and composition stability in heterostructures. While formation energy encompasses a broad range of applications, we specifically focus on cases where components are added or substituted. Formation energy is a fundamental concept in understanding the thermodynamic stability of heterostructured catalysts, providing insights into surface stability. Accurately determining the formation energy requires the establishment of model‐specific equations that account for the total number of components involved. This energy is calculated using the equation.

| (4) |

where E f represents formation energy, E total is the total energy of the heterostructure with added or substituted constituent units, E A/B is the total energy of the original heterostructure, n i represents the number of constituent unit, μ i is the chemical potential of constituent unit i, and N i is the total number of added or substituted constituent units. A negative formation energy indicates a thermodynamically stable state compared to its original states, which supports favorable surface stability. Additionally, normalizing the formation energy by the number of referenced atoms or compounds enables the comparison of different surface conditions. The following examples illustrate the application of formation energy calculations to optimize metal oxide compositions and the quantity of adsorbed oxygen atoms. First, a study was conducted to investigate the origins of the high performance of Ag and MnO x ‐based catalysts for ORR. The ratio of Ag to MnO x and the composition of MnO x both significantly influence catalytic activity, necessitating appropriate modeling strategies. To precisely simulate Ag–MnO x catalysts in DFT modeling, various MnO x configurations were investigated based on experimental observations. In the case of MnO2, formation energy was corrected by the oxygen chemical potential and normalized to the number of Mn atoms. The study revealed that the Mn18O36 nanostripe@Ag(111) had a formation energy of −0.08 eV Mn−1 atom, while the Mn7O9 nanoisland had a formation energy of −0.75 eV Mn−1 atom.[ 62 ] Therefore, they effectively utilized formation energies to assess the model structures by considering the configuration and composition of MnO x . In another study, Liu et al. synthesized an Ir nanorod–MoO3 catalyst embedded in a graphitic carbon layer using various semiconducting metal oxides through the electrospinning method, with IrO2 being reduced. To model the heterostructure based on HRTEM images, they utilized the MoO3(040) and Ir(111) facets. To verify that the electron‐poor Ir state promotes the OER, they compared the OER activity of an oxygen‐covered Ir metallic surface. The formation energy for eight additional surface oxygen atoms was −1.74 eV O−1 atom, compared to −1.63 eV O−1 atom for seven oxygen atoms, −1.62 eV O−1 atom for nine oxygen atoms, and −1.42 eV O−1 atom for ten oxygen atoms (Figure 3d). The model with eight additional surface oxygen atoms, being the most stable in terms of formation energy, was compared with the OER‐active model with seven oxygen atoms and metallic Ir on MoO3. As a result, it was revealed that the added oxygen atoms act as proton acceptors and improve OER activity.[ 63 ] In this way, formation energy functions not only as an indicator for assessing the stability of models but also as a criterion for considering oxidation states and additional active sites, which are important factors in catalytic reaction environments.

Next, the formation energy can be calculated to analyze the stability of substituting specific elements within a heterostructure. In the study of N‐doped graphene (NG) supported on Fe3C as an ORR catalyst, stability was explored by substituting different metals into the Fe positions in the first and second top layers. This analysis involved comparing the energy of NG/Fe3C after the removal of all Fe atoms in the first layer with another metal, with corrections made for the number of substituted metal atoms and the preferred metal carbide units. When substituting Fe in the first layer with another metal, the referenced constituent unit was pure metal. The formation energy was then calculated by comparing it with a model where all Fe atoms were removed from the first layer and adjusting for the substituted metal atoms. According to this equation, a negative formation energy indicates that Fe is more likely to be replaced by other metals in NG/Fe3C. Additionally, for some metals that prefer to exist as carbides rather than in their pure metal when carbon is present, metal carbides were used as the referenced constituent unit. This adjustment accounted for the tendency of the substituted metal to form a separate carbide phase in the presence of graphite. By establishing these equations, the substitutions of Fe by metals and metal carbides in Fe3C encapsulated by NG were effectively modeled. Furthermore, for metals like Ni or Co, which prefer to exist in the metal carbide phase, formation energies were calculated across various substitution concentrations, providing insights into the distribution of metal layers and the concentrations of stable models.[ 64 ] Therefore, by computationally using formation energy to reflect the stable components of the catalyst and its environment in heterostructures, one can propose and compare metal distribution, optimal concentrations with encapsulation, and other key factors for enhancing catalytic performance.

3.4. Vacancy Formation Energy

Vacancy formation energy represents the energy required to create a vacancy within the crystal lattice of a material. It is a critical parameter for understanding the stability of heterostructures and for modeling defective surface conditions. When vacancy formation is energetically favored, vacancies can become reactive species, indicating the potential involvement of lattice atoms in catalytic reactions. This understanding is crucial for understanding the structural integrity and performance of heterostructured catalysts, as vacancies can significantly influence catalytic activity by modifying surface properties and reaction kinetics. By accurately calculating vacancy formation energies in computational modeling, researchers can design heterostructured catalysts that are optimized for enhanced stability and catalytic performance for various applications. The vacancy formation energy (E vac) can be calculated using the equation.

| (5) |

where E vac represents the vacancy formation energy, E vacant is the total energy of the defective structure with the created vacancy, and E pristine is the total energy of the pristine structure without any vacancies. μ vac represents the chemical potential of the vacancy atom, and n i is the number of vacancy atoms. In certain cases, an energy term considering the Fermi level is included, especially for semiconductors; however, it is often disregarded when comparing neutral structures.[ 59 ] A lower vacancy formation energy indicates a more favorable vacancy formation. This metric is essential for determining the stability of heterostructures and the activity of lattice vacancy sites, ultimately aiding in the design of more efficient and stable catalysts.

Through the comparison of vacancy formation energy, one can analyze whether a heterostructure promotes or restricts vacancy formation. Back et al. reported that in hBN/metal‐support heterostructured catalysts, vacancies in hBN are required to activate ORR activity. To determine the preference for B and N vacancy formation in hBN on Ag, Pd, Pt, and Cu supports, they calculated the corresponding vacancy formation energies. Compared to vacancy formation in isolated hBN, B vacancy formation is generally preferred in the presence of a metal support, except under B‐rich conditions on Ag. Notably, B vacancies are most stably formed on Cu support (Figure 3e), highlighting the crucial role of the support in facilitating vacancy formation.[ 21 ] Santos et al. also analyzed vacancy formation energy in a heterostructure formed by 3D InAs(111) with As and In terminations and 2D MoS2(100). They examined the formation energies of As, In, and S vacancies at various sites, including corner, edge, and center for different bonding states. Their calculations revealed that vacancy formation is more favorable at the interface interacting with MoS2 than within the bulk for both As and In terminations. In particular, In vacancies in the In termination had negative vacancy formation energy, indicating a highly favorable spontaneous formation, in contrast to As vacancies. S vacancies in MoS2 at the interface exhibited high positive vacancy formation energy, suggesting a low likelihood of occurrence. Despite the positive vacancy formation energy for As, its proximity to zero suggests that As vacancies could still form under thermal and experimental conditions. This study underscores that vacancies in InAs/MoS2 heterostructures are more likely to form at the surface interface rather than in the bulk of InAs.[ 59 ] It also suggests that it is crucial to consider various factors, such as bonding states, interface interactions, bulk or surface sites, and the specific material characteristics, to comprehensively investigate vacancy formation energy. Furthermore, vacancy formation energy in heterostructures can be used as an indicator of structural stability. Generally, the formation of vacancies can alter material properties or increase the concentration of active species, thereby enhancing catalytic activity. However, if spontaneous defect formation is energetically favored, the overall stability of the catalyst may decrease. Experimentally, a higher concentration of dissolved metals from the catalyst into the electrolyte can indicate reduced stability.

Similarly, in computational studies, metal vacancy formation energy is often used to compare the stability of different catalysts. For instance, Wang et al. addressed stability issues in Ni3S2 utilizing a heterostructure with noble metal Ag. They determined the improved stability by calculating the Ni vacancy formation energy for NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2 and NiOOH/Ni3S2. They found that NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2 required 4.55 eV for Ni vacancy formation, compared to 3.11 eV for NiOOH/Ni3S2, indicating that Ni vacancies are more difficult to form in NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2 (Figure 3f). This higher‐energy requirement was attributed to the shorter Ni—O bond length in NiOOH@Ag/Ni3S2, which suggests stronger Ni—O bonding, contributing to increased stability and potentially reducing Ni dissolution in the electrolyte.[ 45 ] Vacancy formation energy also reflects the stability of defective surfaces. Reda et al. calculated the vacancy formation energy associated with the removal of 1–4 carbon atoms at the Fe3C(010)/N‐doped graphene(NG) interface. They found that while the vacancy formation energy for removing three carbon atoms was positive, the energy was sufficiently small (12 meV C−1 atom), indicating that these atoms could still be removed under pyrolytic conditions. Consequently, the thermodynamically most stable state with the removal of all four carbon atoms was used in their ORR analysis.[ 65 ] Therefore, vacancy formation energy can be utilized both to simulate catalyst surfaces by introducing defects in heterostructures and to assess the overall stability of the heterostructured catalysts.

4. Electronic Structure Analysis

4.1. Charge Density Difference

Charge density difference (CDD) analysis visualizes and quantifies the redistribution of electron density upon the formation of heterostructures. This analysis is essential for understanding the electronic interactions at the interface of two materials. Charge density redistribution analysis, particularly Bader charge analysis, focuses on the spatial distribution of electronic charge within a material. It decomposes the total charge density into contributions from individual atoms, providing a microscopic view of charge distribution.[ 66 ]

Bader analysis, a quantum theory‐based method, divides electronic charge density into atomic contributions by identifying atomic regions with minimum charge density, enabling the assignment of charge to atoms in molecules and condensed phase systems. This method complements CDD analysis by offering an atomistic quantification of charge distribution. The resulting quantitative insights enable the calculation of charge transfer, vital for predicting catalytic activity and stability in heterostructured catalysts.[ 66 , 67 ]

More specifically, charge density can be described as a gradient, moving from a grid point (i, j, k) along the direction which maximizes itself. Charge density gradient can be calculated.

| (6) |

where di, dj, dk are each assigned the values {−1, 0, 1}, but excluding di = dj = dk = 0. The change in charge density

| (7) |

and the distance

| (8) |

are evaluated between neighboring points. is the Cartesian vector to the grid point (i, j, k). The steepest ascent step, , is known to maximize the positive value for . If no such point exists, the point (i, j, k) is the charge density maximum. Based on the trajectories toward the charge density maximum points, Bader volume can be designated, and the charge density within each Bader region is used to quantify the charge density.

Furthermore, the CDD of a heterostructure model can be calculated using the following equation.

| (9) |

where represents the CDD of the heterostructure, is the charge density of the heterostructure, and are the charge density of the isolated materials A and B, respectively.[ 68 ] Researchers employ the CCD analysis, including Bader charge analysis, to validate heterostructure models by quantitatively confirming their characteristics and understanding the electronic interactions at the interface.

4.2. Electron Localization Function

Heterostructured catalysts integrate different materials to enhance catalytic performance through synergistic interactions at their interfaces. ELF provides detailed visualizations of electron distribution within materials, highlighting the nature of bonds, electron pairs, and charge transfer processes. By analyzing ELF, researchers can examine electron distribution across interfaces, identifying changes in bonding and electronic structure induced by heterostructure formation. This analysis reveals regions of electron accumulation or depletion, indicating critical charge transfer between the constituent materials. This understanding is vital for optimizing catalyst design and improving catalytic reactions.

The ELF is a dimensionless scalar field that measures the spatial localization of electrons and can further map out electron pair probability for multielectron systems. It ranges from 0 to 1, where a value of 1 indicates perfect localization and 0 indicates complete delocalization. The ELF was originally defined by Becke and Edgecombe in 1990, as shown in the equation below.

| (10) |

where D(r) is the curvature of the electron pair density, and D h (r) is the corresponding quantity for a homogeneous electron gas with the same density. The ELF is instrumental in visualizing various types of chemical bonds, including covalent, ionic, and metallic bonds, by illustrating how electrons are redistributed within materials. It can distinguish between lone pairs and bonding pairs of electrons, offering insights into the geometry and reactivity of molecules and materials. In heterogeneous catalysts, ELF analysis is particularly useful for interpreting electron localization around active sites and understanding how these localizations influence catalyst activity.[ 69 ] This makes ELF a powerful tool for optimizing the design of heterostructured catalysts. Using ELF in the investigation of these catalysts, researchers can gain deeper insights into electronic interactions at the atomic level. This facilitates the strategic design of more efficient catalysts by identifying optimal configurations and compositions that maximize performance. ELF's detailed analysis clarifies the connection between electronic structure and catalytic activity, facilitating the development of advanced materials tailored for specific catalytic applications.

4.3. Density of States

Density of states (DOS) is a fundamental concept in solid‐state physics and computational materials science that describes the distribution of electron states relative to the Fermi level within a heterostructure. In the context of heterostructures, DOS plays a crucial role in providing a global perspective on the electronic structures. It is particularly effective for examining heterostructure models via DFT. DOS function, D(E), describes the number of electronic states available at each energy level E within a material. It is defined mathematically as

| (11) |

where E i are the energy eigenvalues and δ is the Dirac delta function. DOS is integral to understanding the electronic structure of a material because it indicates how electrons occupy various energy levels and how these distributions are affected by the formation by heterostructures, directly optimizing their electronic properties.[ 70 ]

DOS analysis is pivotal in heterostructures for several reasons. It elucidates how the electronic structure is modified when two materials form a heterostructure, revealing new electronic states at the interface. These changes in the DOS signify the emergence of unique states that can potentially enhance catalytic performance. For example, semiconducting properties of individual materials can shift to metallic properties when forming heterostructures. These new electronic states at the Fermi level can facilitate the charge transfer and increase the electrical conductivity. Moreover, DOS analysis aids in understanding charge transfer dynamics between the materials within the heterostructure. By examining the alignment of energy bands and shifts in the Fermi level before and after heterostructure formation, researchers can track electron redistribution across the interface. Understanding and optimizing these electronic properties through DOS analysis are instrumental in designing efficient and selective heterostructured catalysts.

To accurately determine the DOS, the eigenvalues E i and eigenfunctions for the heterostructure are calculated using the Kohn–Sham equation as seen below.

| (12) |

where V eff(r) is the combination of external potential, Hartree potential, and exchange correlation potential. The energy levels E i are sampled over the Brillouin zone using a dense k‐point mesh and the delta functions are broadened to finite‐width Gaussian or Lorentzian functions for practical numerical evaluation using the below formula.

| (13) |

where σ is the broadening parameter. This method yields a smooth DOS curve, which is crucial for analyzing the global perspective of the electronic properties of heterostructure materials.[ 71 ]

Understanding the d‐band center is essential for improving catalytic performance in heterostructured catalysts. The influence of the d‐band center on catalytic properties was highlighted by Hammer and Nørskov, who demonstrated that its position can predict the reactivity of TMs and suggested it as a descriptor for catalytic activity. The d‐band center is a critical factor in determining the binding strength of adsorbates on surfaces. The d‐band center, ε d , is calculated as.

| (14) |

where ρ(E) is the DOS and E is the relative energy to the Fermi level. The position of the d‐band center affects the binding strength of adsorbates.[ 68 ] A d‐band center closer to the Fermi level typically indicates stronger binding of adsorbates on the catalyst surface, which can enhance catalytic activity by facilitating stronger interaction with reactants and intermediates. However, if the binding is excessively strong, it can lead to catalyst poisoning. Leveraging the concept of the d‐band center allows researchers to optimize the electronic structure of heterostructured catalysts, achieving higher activity and selectivity for specific electrochemical reactions. By carefully selecting and combining materials, computational materials scientists can engineer the d‐band center to tailor the catalyst's reactivity, guiding the development of efficient and sustainable catalytic systems.

4.4. Work Function

Work function is defined as the energy required to remove an electron from a material and elevate it to the vacuum level. In heterostructures composed of different materials, this analysis helps understand how the interface alters surface potential energy and electron emission capability. By assessing the work function of each material and the heterostructured system, researchers can discern shifts in the Fermi level, quantify charge transfer dynamics, and characterize changes in surface dipole moments. These alterations directly impact catalytic activity by influencing the adsorption and desorption of reactants and intermediates on the catalyst surface, thereby guiding the optimization of catalyst design for enhanced performance.[ 72 ]

DFT is useful in determining the work function (Φ) of a heterostructure. After calculating the electrostatic potential across the slab model, the work function is determined from the difference between the vacuum level (V vacuum) and the Fermi level (E f).

| (15) |

This calculation provides valuable insights into how the interface between different materials influences surface potential and charge transfer processes.[ 73 ]

The concept of a Schottky heterojunction is frequently employed when creating high‐performance heterostructured electrocatalysts. A Schottky heterojunction, named after Walter H. Schottky, forms at the interface between two materials, typically a semiconductor and a metal, with different work functions, leading to the formation of a built‐in potential barrier. This barrier, arising from the work function disparity, regulates the transport of charge carriers, electrons or holes, across the junction, resulting in distinct electronic properties and behaviors. This enables precise manipulation of the electronic structure and surface properties to enhance catalytic activity and selectivity for designing heterostructures.[ 74 ] The Schottky heterojunctions in heterostructured catalysts are also pivotal for catalytic reactions that rely on charge transfer processes in electrocatalysis. The built‐in potential barrier at the heterojunction interface dictates the flow of electrons or holes, enabling efficient charge separation.[ 75 ] Tailored engineering of surface properties in each constituent material allows for the modulation of reaction kinetics, with one material acting as a cocatalyst for intermediate activation and the other as a promoter to stabilize reaction intermediates.[ 76 ] Control over band alignment at the interface further influences electron transfer energetics, enhancing reaction efficiency and minimizing energy losses. The unique electronic properties of Schottky heterojunctions provide opportunities for precise tuning of reaction pathways, promoting desired reactions while suppressing undesirable side reactions. By leveraging Schottky heterojunctions and conducting work function calculations, researchers can ensure that heterostructured catalysts are well designed to fulfill their intended purpose. These methodologies provide critical insights into the electronic interactions at interfaces, guiding the development of advanced catalysts tailored for specific catalytic applications.

5. Applications of Heterostructured Electrocatalyst

Developing highly efficient heterostructured electrocatalysts hinges on a thorough understanding of the key factors that govern their performance. This section will explore computational approaches on heterostructured catalysts, focusing on specific electrochemical reactions. By investigating the methodologies and activity descriptors in heterostructure research, we aim to present meaningful insights and comprehensive frameworks for interpreting calculation results of heterostructured electrocatalysts. These insights will provide a practical guide for advancing the application of heterostructured electrocatalysts within computational materials science.

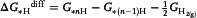

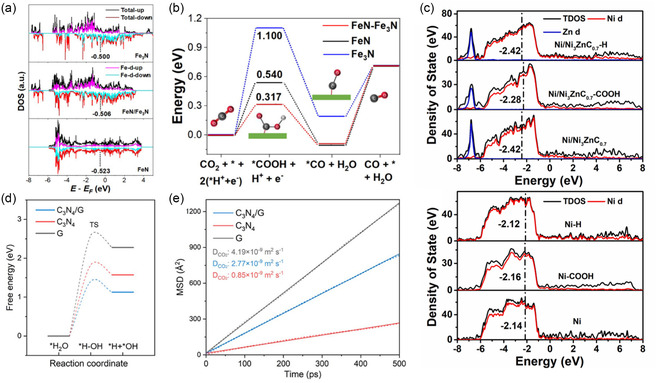

5.1. Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER)