Significance

Heterotrimeric G proteins act as molecular switches that control cellular responses to external signals. Small molecules that selectively inhibit these proteins are essential for studying their function and therapeutic potential. FR900359 (FR) and YM-254890 (YM) are natural inhibitors of Gq/11 proteins, previously thought to act solely by preventing GDP release from the Gα subunit. Here, we show that these inhibitors also enhance the interaction between Gα and Gβγ, thereby locking the entire G protein in its inactive state. This finding refines their known mode of action and suggests a strategy for targeting G protein signaling. Understanding how these inhibitors work at the molecular level provides insights into drug design for diseases involving dysregulated G protein signaling.

Keywords: Gq/11, G protein inhibitors, FR/YM, BRET, X-ray crystallography

Abstract

Heterotrimeric Gα:Gβγ G proteins function as molecular switches downstream of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). They alternate between a heterotrimeric GDP-bound OFF-state and a GTP-bound ON-state in which GαGTP is separated from the Gβγ dimer. Consequently, pharmacological tools to securely prevent the OFF-ON transition are of utmost importance to investigate their molecular switch function, specific contribution to GPCR signal transduction, and potential as drug targets. FR900359 (FR) and YM-254890 (YM), two natural cyclic peptides and highly specific inhibitors of Gq/11 heterotrimers, are exactly such tools. To date, their efficient and long-lasting inhibition of Gq/11 signaling has been attributed solely to a wedge-like binding to Gα, thereby preventing separation of the GTPase and α-helical domains and thus GDP release. Here, we use X-ray crystallography, biochemical and signaling assays, and BRET-based biosensors to show that FR and YM also function as stabilizers of the Gα:Gβγ subunit interface. Our high-resolution structures reveal a network of residues in Gα and two highly conserved amino acids in Gβ that are targeted by FR and YM to glue the Gβγ complex to the inactive GαGDP subunit. Unlike all previously developed nucleotide-state specific inhibitors that sequester Gα in its OFF-state but compete with Gβγ, FR and YM actively promote the inhibitory occlusion of GαGDP by Gβγ. In doing so, they securely lock the entire heterotrimer, not just Gα, in its inactive state. Our results identify FR and YM as molecular glues for Gα and Gβγ that combine simultaneous binding to both subunits with inhibition of G protein signaling.

A hallmark feature of intracellular signaling pathways is the existence of molecular switches, proteins that transition between two principal states: ON and OFF. Heterotrimeric Gα:Gβγ guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins) are among these switches as the major transducers downstream of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) (1–4). GPCRs sense physicochemical signals of different origin from the environment and relay these to a network of (intra-)cellular signaling proteins including ion channels, enzymes, and kinases and, thereby, impact numerous facets of cell physiology in health and disease (5). Because G proteins—at the core of this network—are directly activated by GPCRs, cells that express them can connect surveillance of the extracellular environment to efficient onset, intensity, duration, and termination of cellular signaling.

Essential to this regulatory function is the ability of G proteins to bind and hydrolyze GDP and GTP nucleotides, respectively. G proteins are composed of a nucleotide-binding Gα subunit and a constitutive Gβγ dimer. In the canonical nonsignaling state, GαGDP is bound to Gβγ to form an inactive heterotrimer. Upon activation by ligand-stimulated GPCRs [functioning as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs)] or by nonreceptor GEFs, GDP is exchanged for GTP leading to conformational changes in Gα that enable a stable engagement of effectors while, at the same time, precluding the interaction with Gβγ. Signaling is terminated by GTP hydrolysis, typically assisted by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) or by domains of the G protein effectors that function as GAPs (6–9). Physiologically, GTP hydrolysis relieves the high energy state of GαGTP, allowing an efficient ON–OFF transition and the return to the GαGDP form that tightly rebinds to Gβγ, thereby completing the activation-deactivation cycle (6–10).

Pharmacological deactivation of G protein signaling by exogenous chemicals appears far more challenging. Despite the discovery of G proteins over four decades ago, disabling the signaling function of large heterotrimeric G protein GTPases is still in its infancy. Pertussis toxin (PTX), which ADP-ribosylates all Gi/o family members except Gz, and the PTX-like protein OZITX, which ADP-ribosylates Go, Gi, and Gz (11–13), render Gi family proteins incapable of coupling to GPCRs only, without disturbing their ability to relay signals from nonreceptor GEFs. A recently developed nucleotide state-selective macrocyclic Gs inhibitor, GD20, sequesters the Gαs OFF-state (14). However, its cell permeable variant cpGD20 requires extended preincubation times just as the toxins, fails to inhibit Gαs-mediated cAMP formation in cells, and potentially prolongs Gβγ signaling, thereby fine-tuning rather than disabling the signaling of entire Gs heterotrimers.

In contrast, the natural cyclic depsipeptides FR and YM are cell-permeable, display remarkable on-target residence times and can be added at will to fully and rapidly blunt signaling of entire Gq/11 heterotrimers with unrivaled specificity (15). Numerous preclinical studies have corroborated their power as pharmacological research tools to investigate G protein signaling as well as their potential for the treatment of complex pathologies involving aberrant Gq protein function (16–21).

Structurally (Fig. 1A) and mechanistically, both depsipeptides are remarkably alike. Both are classified as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), specifically inhibiting GDP-GTP exchange on the Gα subunits of Gq/11 proteins (6–9, 22). They achieve their GDI function by wedging in between the GTPase and α-helical domains of the Gα subunit, thereby preventing the motion of the α-helical domain required for GDP release. A 2.9 Å resolution crystal structure of YM bound to a heterotrimeric Gq/i chimera has illuminated key features of its binding configuration to and its GDI action on Gαq (23). Intriguingly, this very structure implies but does not resolve whether the obligate Gβγ dimer, by itself a GDI for Gα in its basal state, is also involved in the inhibitors’ mechanism. Resolving this question is important for two reasons. First, to rationalize why FR and YM surpass any other compound in suppressing the signaling of entire heterotrimers despite the shared scavenging of Gα in its OFF-state. Second, to guide the path toward unlocking inhibition of heterotrimers for the remainder of large G protein GTPases.

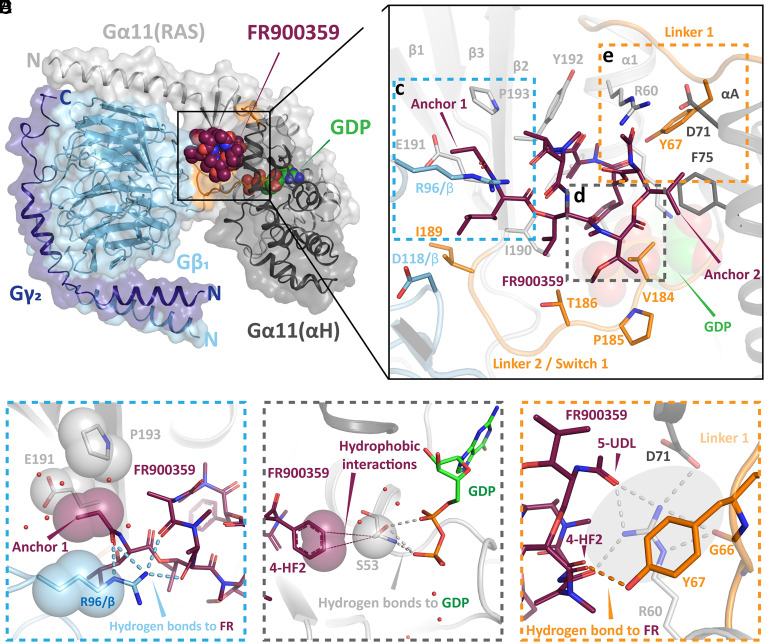

Fig. 1.

Ligand binding and functional characterization of the G11/FR complex. (A) 2D representation of YM-254890 (YM) in dark yellow. FR900359 (FR) has the same scaffold as YM but with two extra alkyl moieties at anchors 1 and 2, shown and highlighted in red. The two anchors are located on opposite sides of the inhibitor scaffold. (B) Thermostability assay of G11iN3-S in the absence and the presence of FR measuring the ratio of 350 nm and 330 nm tryptophan fluorescence. The upper panel shows the unfolding curves and the lower panel displays their first derivative, in which the peaks (maximum and saddle points) represent the melting temperature of each species. In the inhibitor-free state, two transitions are observed: one at 51.36 ± 0.16 °C and one at 57.56 ± 0.08 °C. Upon FR binding, the unfolding curve changes to a single-transition curve with a point of inflection at 60.94 ± 0.08 °C. Data represent mean ± SEM of at least three independent replicates. (C) Representative sensorgram of FR binding (0 to 120 s) and unbinding (120 to 6,000 s) to G11iN3-S measured by grating-coupled interferometry (GCI) using the waveRAPID® technology. A single-digit nanomolar binding affinity was determined under the assumption of a heterogeneous analyte binding model to account for the biphasic unbinding profile. (D) GTPase Glo assay® measuring specific receptor-induced activation and FR-mediated inhibition of purified G11iN3-S. The protein shows some basal activity of GTP depletion (white) that increases moderately in the presence of an inactive GPCR (light gray). We used the light-activated GPCR jumping spider rhodopsin 1 (JSR1) to stimulate the G protein and observed a significant increase in GTP depletion rate (dark gray) that can be fully inhibited by the addition of FR (red). Data represent mean ± SEM values of at least 6 replicates. We assessed statistical differences by a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05). “ns” stands for nonsignificant.

To fill this gap, we solved two X-ray structures of the Gα11iNβ1γ2 heterotrimer bound to FR and YM at 1.43 and 1.70 Å resolution, respectively, the highest reported to date for any heterotrimeric G protein structure. Our high-resolution structures of a G11 heterotrimer accommodating two highly specific inhibitors enabled us to identify additional inhibitor contact sites within Gα refining and extending i) the structural framework underlying inhibitor:Gα interaction and ii) the mechanistic framework underlying inhibition of Gα nucleotide exchange. Beyond that, we reveal an unexpected role of Gβγ in the inhibitors’ mechanism, thereby classifying FR and YM as bimodal ligands acting like molecular glues to stabilize the protein–protein interaction between Gα and Gβγ.

Results

We expressed and purified (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) different variants of Gαq/11 proteins as previously described (23) to attempt the production of diffraction-quality crystals. We successfully grew crystals of a heterotrimeric Gα11β1γ2 complex bound to FR using the vapor diffusion method at 4 °C and solved its structure by X-ray cryocrystallography to a resolution of 1.43 Å (SI Appendix, Table S1). The construct design was based on previously reported structures of the Gαq/11 family (23, 24). Namely, the N-terminal helix of Gα11 was replaced by the first 29 amino acids of Gαi1 (Gα11iN1-29) to increase protein solubility. To optimize expression and purification, an N-terminal, cleavable eGFP was fused to Gα11iN1-29. Gβ1 was N-terminally fused to a cleavable deca-histidine-tag. The prenylation site of Gγ2 was removed by introducing the known mutation C68S to create a fully soluble heterotrimer. The final crystallized complex was thus Gα11iN1-29β1γ2C68S:FR900359 which will be abbreviated from now on as G11iN3-S:FR (3 = heterotrimer; S = soluble).

We assessed the functionality of our construct using several methods. First, we measured the thermostability of G11iN3-S in the absence and presence of FR (Fig. 1B). In the absence of FR, two transitions are observed in the melting temperature curve: one at 51.4 °C, corresponding to the unfolding of the Gα subunit and one at 57.6 °C, representing the unfolding of Gβγ. Upon FR binding, the unfolding curve simplifies to display a single transition with an inflection point at 60.9 °C. This significant increase in melting temperature in the presence of FR indicates specific ligand binding to functionally folded protein. Moreover, the change to a single melting point that is higher than the two individual melting temperatures in the absence of inhibitor suggests the unpredicted stabilization of the Gα/Gβ interface—and, thus, of the entire heterotrimer—by FR. In addition, FR binding to G11iN3-S measured by grating-coupled interferometry (GCI) shows nanomolar binding affinity (Fig. 1C), in close agreement with values reported in the literature (25). Finally, we assessed the functionality of the purified protein by measuring its GTPase activity. We find specific receptor-induced activation and FR-mediated inhibition of our construct (Fig. 1D).

The heterotrimeric G protein displays its typical fold, with the Gα subunit composed of a Ras-like GTPase and an α-helical domain connected by linker 1 and linker 2/switch I, a Gβ subunit with a seven-blade β-propeller fold and an α-helical N terminus parallel to the Gγ subunit which further wraps around Gβ (Fig. 2A). The overall structure superposes well with other structures of the Gαq/11 family [e.g., 0.8 Å RMSD to the Gαq/i heterotrimer bound to YM (23)].

Fig. 2.

X-ray structure of G11iN3-S in complex with FR. (A) Overall view of the crystal structure shown as cartoons with a translucent molecular surface. The Gα11 subunit is shown in gray (Gα-RAS: light; Gα-αH: dark), Gβ in cyan, Gγ in dark blue, and linker 1 and linker 2/switch I in orange. FR and GDP are depicted as spheres with red and green carbon atoms, respectively. (B) Close-up view of the FR binding pocket. FR and the interacting amino acid side chains (distance < 3 Å) are depicted as sticks. The inhibitor interacts with residues from both Gα domains, with both linkers and, additionally, contacts R96 from the Gβ subunit (blue dashed box). Two additional dashed boxes (gray, orange) highlight other notable ligand–protein interactions, which are shown in greater detail in panels c–e. (C) The side chain of R96 in the Gβ subunit extends toward FR in a straight conformation and establishes four direct hydrogen bonds with the inhibitor (blue dashed lines). Furthermore, anchor 1 of FR inserts into a small hydrophobic pocket (shown as translucent spheres) composed of the R96 side chain in Gβ and E191G.S2.03 and P193G.S2.05 in Gα. (D) Direct interaction of FR with the nucleotide-binding pocket: the phenyl ring of FR contacts S53G.H1.02 at the P-loop through a hydrophobic interaction (shown as red translucent spheres and thin lines). Residue S53G.H1.02 also coordinates the phosphate groups of GDP through hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). (E) The direct polar contact between FR and Y67G.h1ha.04 in linker 1 (red dashed line) is shown in the foreground. The inhibitor also stabilizes linker 1 through a hydrogen bond network mediated by R60G.H1.09, shown in gray (circled dashed lines) in the background.

FR binds to a central part of the heterotrimer at the interface of the two Gα domains and the Gβ subunit and near the GDP-binding pocket, in the same site where YM-254890 binds to Gq/11 (23). The high-resolution diffraction data and the resulting detailed and well-defined electron density map (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) allowed the unambiguous modeling of the inhibitor in the binding pocket.

FR binds to a shallow pocket composed of helix α1 in the GTPase domain, helix αA in the α-helical domain, and of the joining linker 1 and linker 2/switch I. Furthermore, anchor 1 of FR extends into a wide-open cleft on the Gα/Gβ interface (Fig. 2 B and C). Many putative interactions between FR and Gq have been predicted and tested (25) and many of these are indeed observed in our structure. However, our high-resolution data allow us to detect additional interactions that provide fresh insights into the singular properties of FR.

In the inhibitor binding pocket, we observed several interactions between the anchor 1 region of FR and the Gβ subunit, namely with Ser97 and the previously unidentified Asp118 and Arg96 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The most striking feature is the interaction of Arg96, consisting of four direct and one water-mediated hydrogen bonds (Fig. 2C). This interaction is responsible for four of the eleven polar contacts formed with the ligand and presumably contributes decisively to the stability of the heterotrimer. From a structural point of view, Arg96/Gβ appears to “cover” anchor 1 of FR, locking it in a stable pose in an otherwise shallow binding pocket. The ethyl group of anchor 1 is also positioned near Glu191G.S2.03 [the superscript corresponds to the G protein general residue numbering (26)] and Pro193G.S2.05 of the GTPase domain. Hydrophobic interactions within this triad of residues from the Gα and Gβ subunits further stabilize the anchor 1 region (Fig. 2C), as shown by its very low average B-factors (21.8 Å2), indicating an exceptional rigidity of the Gα and Gβ interface that contributes to the stabilization of the heterotrimer.

We also observe a previously unrecognized hydrophobic contact between the phenyl ring of FR and Ser53G.H1.02 in the P-loop of the GTPase domain (Fig. 2D). Ser53G.H1.02 is completely conserved in all G protein families and is involved in nucleotide binding and exchange by binding the phosphate groups of GDP/GTP and a Mg2+ ion. It has been shown that Mg2+ has a rather low affinity (in the millimolar range) to the GDP-bound state of G proteins (27, 28) that increases significantly in the GTP-bound state toward a low nanomolar affinity. So, despite the presence of Mg2+ ions in the purification buffer at a concentration of 1 mM, we obtained a magnesium-free structure, as expected in the GDP-bound state. In our structure, the oxygen of the Ser53G.H1.02 side chain is oriented toward both phosphate groups of GDP. This places Ser53G.H1.02 between GDP and FR, resulting in a direct contact between the side chain and the inhibitor (Fig. 2D). Remarkably, this contact between the inhibitor and the P-loop was predicted by molecular dynamics simulations of Gq/FR complexes in which the relative mobility of the S53G.H1.02 side chain clearly differed between the inhibitor-free and inhibitor-bound ensembles (29). Here, we provide experimental evidence of a direct influence of FR on the nucleotide-binding pocket. We suspect that FR binding reduces the flexibility of the Ser53G.H1.02 side chain, which further hinders efficient nucleotide exchange, revealing an additional feature to the inhibition mechanism of the Gq/11 family by cyclic depsipeptides.

Moreover, we observed another previously unidentified contact between FR and Tyr67G.h1ha.04 (Fig. 2E). This residue is part of linker 1 connecting the GTPase and α-helical domains, which is associated with the regulation of nucleotide exchange rates as well as GPCR interaction specificity (30–32). So far, it was assumed that linker 1 showed reduced mobility in the presence of an inhibitor solely due to indirect interactions mediated by Arg60G.H1.09 (23). The additional direct polar interaction with Tyr67G.h1ha.04 further stabilizes this crucial region. In addition, the structure shows that Arg60G.H1.09 (23) and Tyr67G.h1ha.04 mutually stabilize each other through a cation–π interaction (distance between the guanidinium moiety of Arg60G.H1.09 (23) and the aromatic ring of Tyr67G.h1ha.04 = 4.5 Å).

Based on this high-resolution structure of the G11/FR complex, we have been able to identify several interactions not observed in the published Gq/YM structure6. However, it was not possible to determine whether these interactions (mediated by Arg96/Gβ, Ser53G.H1.02, and Tyr67G.h1ha.04) were unique to the binding mode of FR or if they could also be made by YM, as the lower resolution of the Gq/YM structure prevented precise modeling of the ligand binding pose. For instance, in the published Gq/YM crystal structure (23), the inhibitor was not modeled close enough to Tyr67G.h1ha.04 for this interaction to be detected. Interestingly, there is unexplained positive mFo − DFc electron density in the Gq/YM maps exactly at this position, suggesting that YM may share these features with FR. Therefore, to discriminate between inhibitor-specific and more general features rationalizing the mode of action of Gq cyclic depsipeptide inhibitors, we determined a high-resolution structure of the G11/YM complex as well.

We adapted the purification and cocrystallization protocols using YM instead of FR to grow crystals of a G11/YM complex under almost identical conditions. We solved the structure of the G11iN3-S:YM complex at a 1.7 Å resolution, allowing us to investigate the binding modes of both ligands with remarkable accuracy (Fig. 3).

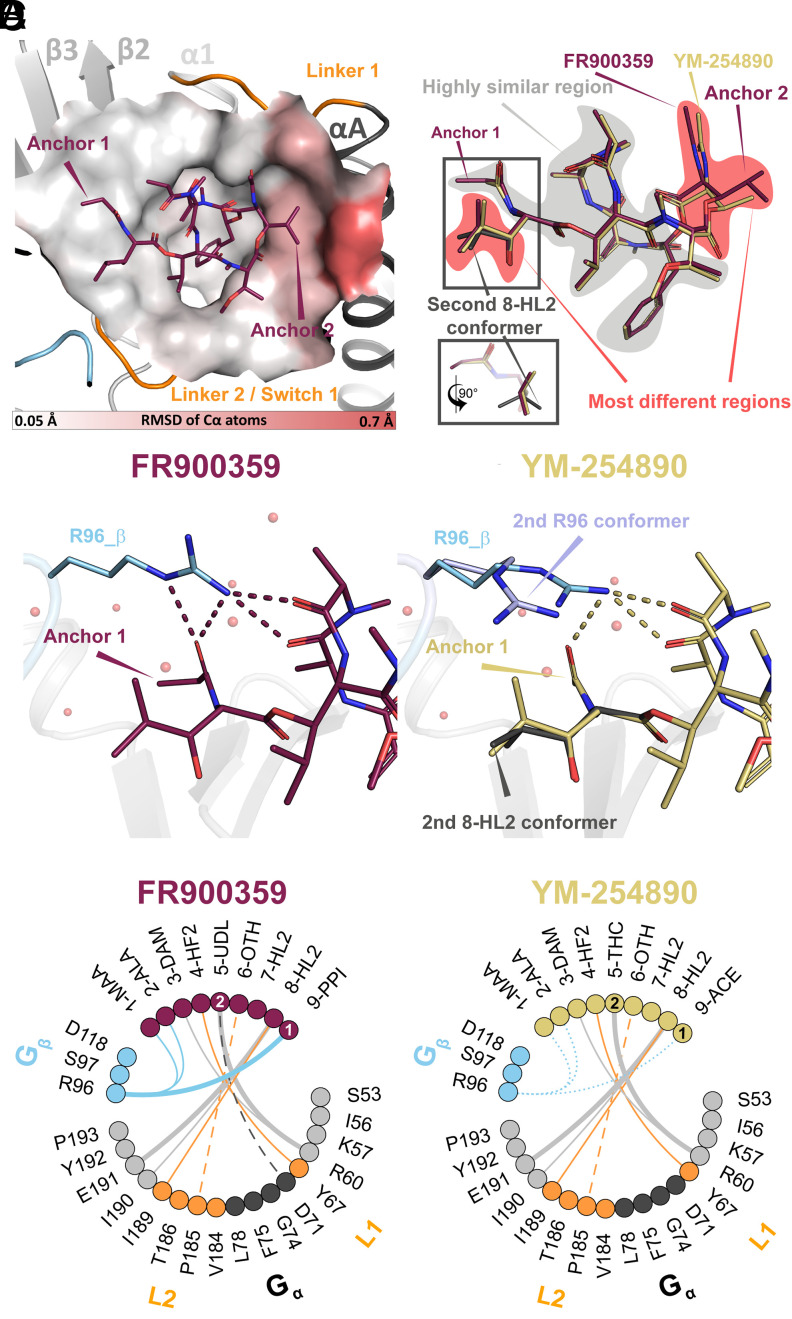

Fig. 3.

Comparison between the G11/FR and the G11/YM crystal structures. The structures were aligned on the Cα atoms of the protein. (A) Local structural differences between the binding pockets (measured as relative RMSD of the protein Cα atoms) are used to color the protein surface around FR. RMSD values are depicted with a color gradient from light gray (RMSD = 0.05 Å; nearly identical local protein structure between FR and YM) to red (RMSD = 0.7 Å; maximum differences). The changes are subtle and can only be clearly observed in the region near anchor 2, where Asp71H.HA.03 and Gly74H.HA.06 of helix αA are mildly displaced away from FR compared to the G11/YM structure. (B) Comparison of the ligand binding poses. The two ligands show only small structural differences. In particular, the ligand core (shaded in gray) is highly similar. The main differences appear near both anchors (shaded in red). A small difference in the position of anchor 2 in FR translates into a small local rearrangement of its backbone. In addition, a second conformer of the β-hydroxyleucine (residue ID: 8-HL2) side chain near anchor 1 is observed in YM with 0.5 occupancy. In the figure, residues in FR and YM are labeled according to their assigned residue ID (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). (C) Detailed view of the region around anchor 1 of FR (Left panel) and YM (Right panel). The interactions of R96/Gβ with FR include four direct hydrogen bonds (red dashes). In the presence of YM, however, R96/Gβ displays two conformations: The first conformer (occupancy 0.5) is similar to that of FR, forming three hydrogen bonds with YM (yellow dashes). Interestingly, a second conformer that does not contact YM is also observed. (D) Interaction plots between both ligands and the binding pocket (FR Left, YM Right). Residues of FR/YM and G11iN3-S within 4.5 Å of the ligands are represented as filled circles colored as in Fig. 2A. The lines depict contacts between residues within a radius of 3.5 Å. The thickness of the line represents the number of interatomic interactions between the residues (thin = single interaction; thick = two interactions). Solid lines correspond to polar interactions and dashed lines to van-der-Waals contacts. In the YM plot, the conformational variability of R96 is depicted by representing its weaker interactions with the ligand as dotted lines.

We found that the two protein–ligand complexes align very well (RMSD = 0.2 Å), including the ligand-binding sites of FR and YM, which are virtually superimposable. While all newly described ligand–protein interactions of the G11/FR structure are also present in the G11/YM structure, we also identified differences in the protein backbone (Fig. 3A), the ligand-binding poses (Fig. 3B), and in protein side chains (Fig. 3C), collectively rationalizing the slightly lower affinity of YM:G11iN3-S binding as determined by GCI (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Subtle changes in the protein backbone can be observed around anchor 2 (Fig. 3A), where Asp71H.HA.03 and Gly74H.HA.06 of helix αA are mildly pushed away from FR compared to YM. The isopropyl moiety of FR is slightly shifted compared to the methyl group of YM (Fig. 3B) due to a steric clash with Gly74H.HA.06 and an additional contact to Asp71H.HA.03 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). This displacement has only mild consequences on the structure of the cyclic backbone of FR, e.g., the N-acetyl side chain is relocated by 0.7 Å toward the opposite side of the pocket (i.e., toward anchor 1). Another change in the ligand-binding pose is the presence of a second conformer of the β-hydroxyleucine side chain near anchor 1 in YM where one methyl group is rotated by ~80° (Fig. 3B).

The most noticeable difference between the G11/FR and G11/YM complexes is at the Gα/Gβ interface (Fig. 3 C and D). Our data show a second conformer of Arg96/Gβ in the YM structure (Fig. 3C) that relocates the side chain away from YM to interact with Asp118 also in the surface of Gβ through a water molecule. Both Arg96 and Asp118 are highly conserved in Gβ subfamilies. One conformer (occupancy = 0.5) still interacts with YM but is tilted by ~70° compared to the G11:FR structure resulting in the loss of one of the four hydrogen bonds to the inhibitor. Notably, the second conformer, which does not interact with the inhibitor directly, is located above the β-hydroxyleucine residue of YM (8-HL2 in Fig. 3C), suggesting a possible coupling between these two elements.

In addition to direct interactions between ligand and protein, water-mediated effects can contribute significantly to binding (33). The high resolution of our electron density maps allowed us to model 760 and 804 water molecules in the FR/G11 and YM/G11 complexes, respectively. In shallow and open binding pockets exposed to the solvent, the formation of enthalpically favorable first-shell hydration layers around solvent-exposed parts of ligands can be relevant for binding (34). Indeed, we observe an extended and continuous hydrogen bonding network of first-shell waters that extends to polar functional groups of the ligand and the protein (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Table S2). Even though many of these waters do not directly contact the ligand, they all show strong electron densities, indicating that they are well ordered (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A).

Fig. 4.

Ligand solvation. Water networks in the first solvation shell of FR (Left panel) and YM (Right panel). Water molecules are represented as small spheres (FR = red, YM = dark yellow), ligands are shown as spheres (FR = red, YM = dark yellow), the interacting protein residues as sticks, and the protein backbone as translucent cartoons. Water–water interactions are indicated with thick dashes and water–ligand and water–protein interactions are represented by thin black dashes. Differences in the solvation of both ligands, with a stronger solvation of YM, could potentially contribute to the different binding profiles of FR and YM.

The remarkable order of the first-shell waters can be attributed to the rigidity of the ligands in the binding site, as evidenced by their well-defined electron density (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). NMR studies (35–37) have shown that the cyclic depsipeptide backbones of FR and YM also exist primarily in a well-defined conformation in water, with all amide bonds in a trans conformation except for one cis amide bond between the phenyllactic acid and the N-methyl-α-β-dehydroalanine residues, which adopt the same conformations that we observed in our structures. This rigidity of the depsipeptide backbone is compatible with a conformational selection binding mechanism (25). There may be greater diversity in the ligand side chain conformations, as observed in the β-hydroxyleucine (residue ID: 8-HL2) side chain near anchor 1 of YM (Fig. 3B). In this case, the preferred conformation will depend on the precise backbone geometry but also on the interaction of the ligand side chains with neighboring residues in the peptide or the protein.

At the Gα/Gβ interface, near anchor 1, the first-shell water layer over the ligands is less dense due to the shielding by Arg96/Gβ. The smaller acetyl group in anchor 1 of YM allows the presence of water A that bridges the inhibitor to the backbone of Arg96 (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). However, the larger propionyl in anchor 1 of FR shifts water A (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), resulting in the relocation of the Arg96 side chain closer to anchor 1 of FR. This allows the formation of further polar and hydrophobic interactions with FR, which may translate into the observed conformational stability of the Arg96 side chain.

In summary, our structures reveal three unrecognized mechanistic features underlying the action of FR and YM. The inhibitors i) stabilize the GDP-bound conformation via a direct contact to Ser53G.H1.02 in the P-loop of the GTPase domain, ii) increase the rigidity of linker 1 by contacting Tyr67G.h1ha.04, further hindering nucleotide exchange, and iii) the long side chain of Arg96 in Gβ disrupts a first-shell layer of waters in a shallow binding pocket and holds over the inhibitors, tightly over FR and more loosely over YM. Furthermore, our structures reveal previously unrecognized direct polar interactions of both inhibitors with the Gβ residue Arg96. This led us to hypothesize a more prominent role for the Gβγ complex in the inhibitors’ mechanism than just acting as a GDI for GαGDP. We hypothesized that direct inhibitor–Gβ interactions could translate into enhanced stabilization of the G protein heterotrimer—beyond Gα inactivation alone.

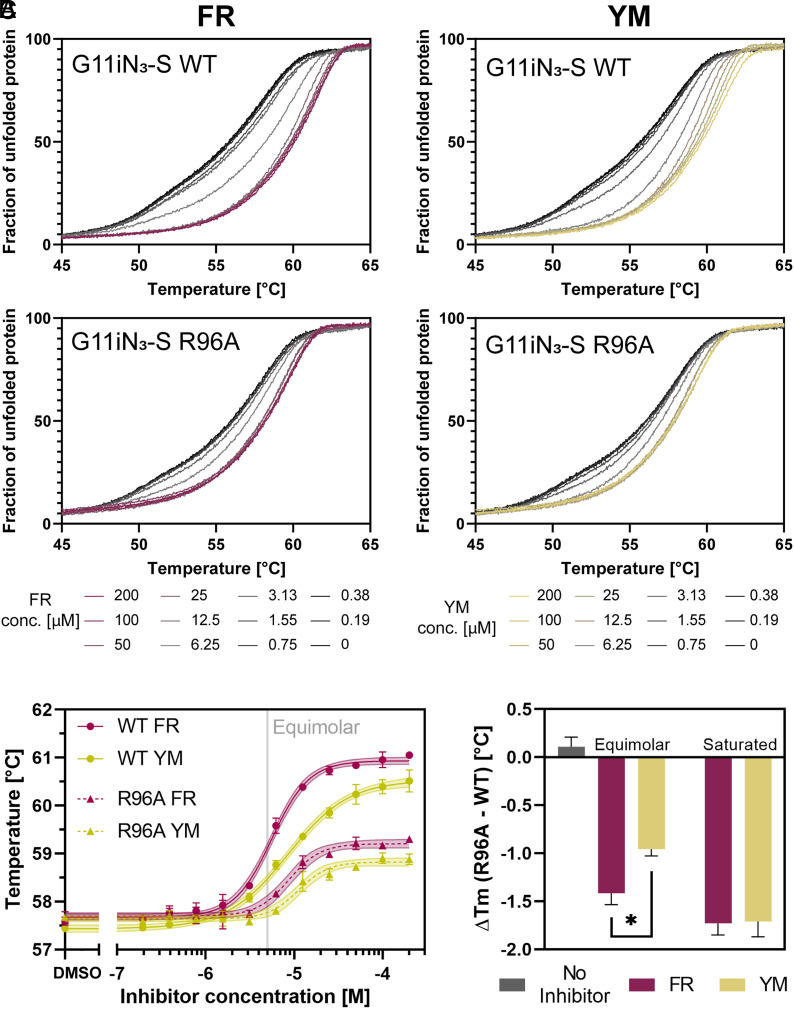

To test this hypothesis, we used site-directed mutagenesis to mutate Arg96 in Gβ to alanine. We then assessed its potential involvement in inhibitor binding by recording GCI sensorgrams for FR and YM and compared these with G11iN3-S WT. Indeed, our results indicate that the R96A mutation leads to a modest but detectable decrease in affinity (two- and three-fold) for both ligands (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). We then turned to thermal stability analysis of wild-type and R96A heterotrimers in the presence and absence of the inhibitors (Fig. 5A). In the absence of inhibitors, the wild-type and mutant heterotrimers display near-identical biphasic curves with two distinct unfolding events, indicating that the R96A mutation does not impact protein stability in the inhibitor-free state. For the wild-type heterotrimer, addition of FR or YM results in a concentration-dependent thermal stabilization and change into a monophasic unfolding profile. Notably, in the R96A mutant, inhibitor-mediated enhancement of thermal stability was significantly diminished, consistent with the role of Arg96/Gβ as a direct inhibitor contact site. To more accurately characterize the thermal stability of wild-type and R96A heterotrimers, we plotted its dependence on the inhibitor concentration. (Fig. 5B). We observed that the wild type was more effectively stabilized by both inhibitors than the mutant (solid vs dashed lines in Fig. 5B) and that FR confers slightly greater stabilization than YM for both the wild type and the mutant (red vs yellow lines in Fig. 5B). These data indicate that the loss of inhibitor contact to Arg96/Gβ significantly diminishes their ability to stabilize G11 heterotrimers. We have quantified this effect in Fig. 5C and noticed that at equimolar concentrations of inhibitor and protein, inhibitor-mediated enhancement of thermal stability differs between FR and YM [ΔTm (FR) = −1.41 ± 0.12 °C; ΔTm (YM) = −0.96 ± 0.07 °C], consistent with our structural findings. This difference disappears at saturating concentrations, where both inhibitors display a similar behavior −ΔTm (FR) = −1.73 ± 0.12 °C; ΔTm (YM) = −1.71 ± 0.16 °C]. These data reveal that both inhibitors exhibit a molecular glue function between the Gα subunit and the Gβγ complex which is mediated by Arg96/Gβ.

Fig. 5.

Influence of R96/Gβ on inhibitor-induced G protein heterotrimer stabilization. (A) NanoDSF data from titration of FR or YM on different G11 variants using a protein concentration of 5 μM. The plot shows mean values from at least three independent replicates. The normalized unfolding curves from the 350 nm/330 nm ratio represent the fraction of unfolded heterotrimeric G11 variants. The ligand concentration ranges from 200 μM (red for FR/yellow for YM) to 0 μM (black). The curves display the same shape as described in Fig. 1B. (B) Thermal stability concentration–response curves of G11iN3-S WT and the R96A mutant in the presence of FR and YM. Melting points were calculated from the inflection points of the curves in panel (A). The melting temperatures are shown as circles for G11iN3-S WT and triangles for the R96A/Gβ mutant. Solid (WT) and dashed (R96A) lines show the fitted data with a 95% CI. (C) Difference in melting temperature [ΔTm = Tm (R96A) – Tm (WT)] at either saturating or equimolar inhibitor concentrations derived from the curves shown in panel (A). Bars represent the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05). The negative values indicate a relative destabilization induced by the mutation.

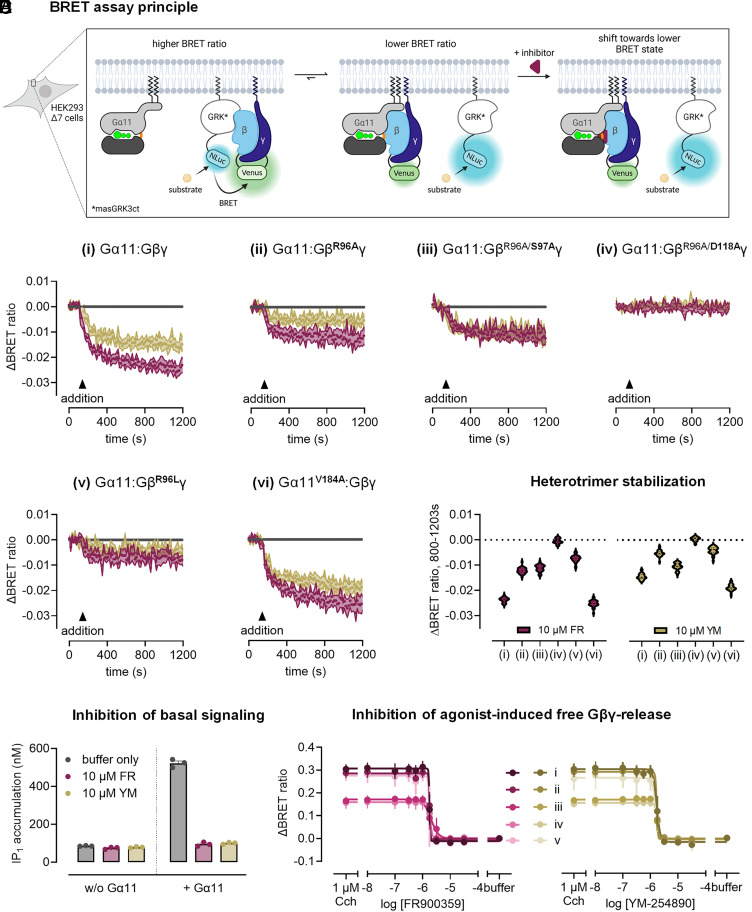

To investigate whether heterotrimer stabilization can be recapitulated in a cellular environment, we monitored the effects of FR and YM on Gα11:Gβ1γ2 heterotrimers in their basal state in living cells. We limited the inhibitor effects to Gα11 heterotrimers by reexpressing wild-type Gα11 and the crystallization construct Gα11iN1-29 in CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited HEK293 cells lacking all other Gα subtypes apart from Gαi/o (HEK293 Δ7) (38). We then employed a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based approach measuring the competition for Gβγ binding between the Gα11 subunit and a membrane-associated Gβγ-effector mimic, the C-terminus of GPCR kinase 3 (masGRK3ct). BRET was achieved by tagging the Gβγ dimer with a split Venus as BRET acceptor and masGRK3ct with nano luciferase as the BRET donor. In this experimental setup, sequestering of free Gβγ dimers by masGRK3ct produces high BRET signals, which are diminished by coexpressed Gα11. A stabilization of Gα11:Gβγ heterotrimers by FR and YM would shift the equilibrium toward Gα-bound Gβγ and away from Gβγ:masGRK3ct, and hence manifest in a BRET decrease (Fig. 6A). This sensor is particularly suited to investigate our question, as it uses split Venus-tagged Gβγ and changes in BRET ratio can be unambiguously assigned to differences in the direct interactions between the transfected Gβ subunit and the Gα11:inhibitor complex, while bypassing the confounding contribution of endogenous Gβ proteins.

Fig. 6.

FR and YM stabilize the Gα11:Gβγ heterotrimer in cells through an interaction with R96/Gβ. (A) BRET assay in living cells, in which Gβγ is tagged with split Venus (BRET acceptor) and masGRK3ct with NanoLuc luciferase (Nluc, BRET donor). The binding of free Gβγ to masGRK3ct results in a basal BRET signal. Inhibitor-induced heterotrimer stabilization shifts the equilibrium further toward Gα-bound Gβγ resulting in a BRET ratio decrease. (B) Effect of FR or YM addition (10 µM, saturating concentration) on the BRET signal in HEK293 Δ7 cells transiently transfected with the indicated Gα11 and BRET sensor constructs, as well as PTX-S1. BRET traces represent mean ± SEM of at least five independent biological replicates. (C) Violin plot summary of the BRET data shown in (B). (D) Effect of FR or YM addition (10 µM, saturating concentration) on basal IP1 accumulation in HEK ΔGq/11-KO cells transiently transfected with BRET sensor constructs and PTX-S1, and with either Gα11 or vector control. Data are mean + SEM of four independent biological experiments done in triplicate. (E) Buffer-corrected BRET ratio concentration-inhibition curves after preincubation with FR or YM (inhibition of carbachol signal induced at its EC90 via muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3) in HEK293 ∆7 cells transiently transfected with Gα11 and the indicated Gβγ split Venus constructs, Nluc-tagged masGRK3ct, and M3 receptor, as well as PTX-S1. Note that “buffer” represents conditions without carbachol and FR/YM. Data points are mean ± SEM of three to eight independent biological replicates. BRET: bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, masGRK3ct: myristic acid attachment peptide-fused GRK3 c-terminus; CCh: carbachol.

The addition of both FR and YM decreased the basal BRET ratio, indicating a shift of the G protein population toward Gα:Gβγ heterotrimers for both Gα11 wild type (Fig. 6 B, i and C) and the crystallization construct Gα11iN1-29 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A, i and ii). Interestingly, the effect on BRET amplitude induced by YM is smaller than that induced by FR, in accordance with its smaller shift in the thermostability assays and the observed differences in Gβ contacts in the crystal structures. This drop of BRET is not likely to originate from reduced basal activity, as both inhibitors suppress basal IP1 production to the same extent (Fig. 6D). Though likely, it is not clear whether the observed BRET decrease invariably depends on a direct physical interaction between FR and YM and Arg96 in Gβ. To investigate this, we made use of the previously created Gβ R96A mutant.

Consistent with our thermostability data and with the contribution of Arg96 to heterotrimer stabilization, mutation of Arg96 to Ala significantly reduced the stabilizing effect of the inhibitors on the heterotrimer in unstimulated cells, for both Gα11 wild type and Gα11iN1-29 (Fig. 6 B, ii and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A, iii and B). We also probed the relevance for heterotrimer stabilization of the previously unidentified Asp118/Gβ and Ser97/Gβ within the inhibitor-binding pocket. The BRET profiles of the respective alanine mutants of Asp118/Gβ and Ser97/Gβ in addition to R96A (Fig. 6 B, iii and iv) suggest that the two highly conserved residues within Gβ, Arg96 and Asp118, fully account for the heterotrimer stabilization observed with FR and YM.

In turn, we hypothesized that heterotrimer stabilization by the inhibitors should be compromised in the background of an already stabilized heterotrimer. We tested this hypothesis with a heterotrimer harboring GβR96L, a loss-of-function Gβ variant causally related to severe global developmental delay (39). This disease-causing Gβ mutant has been reported to show enhanced Gα binding and should, therefore, display lower propensity to further stabilization by FR and YM. Indeed, BRET decreases were largely diminished for both inhibitors on Gα11:GβR96LGγ2, entirely consistent with the reduction of a stabilizing effect in an already stabilized mutant (Fig. 6 B, v and C). In contrast, an equally efficacious inhibition by FR and YM was observed when Gα11:GβR96LGγ2 heterotrimers were activated with carbachol-bound muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 (M3R) (Fig. 6E). These data discriminate active heterotrimer stabilization (differential action for both inhibitors) from stabilization through inhibition of ligand- and GPCR-mediated G protein signaling (identical action for both inhibitors). Moreover, because mutations of Arg96, Asp118, and Ser97 in Gβ do not impact inhibitor potency (Fig. 6E), our data also indicate that the inhibitor:Gα interaction is sufficient to block G protein activation, consistent with the previous finding that Gβγ is neither required nor conducive to inhibition of nucleotide exchange by YM of Gαq (23). Activation potencies of carbachol-stimulated G11 heterotrimers by exogenous M3R were comparable across all mutations, attesting intact activation profiles similar to those observed with G11 wild-type proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Interestingly, mutation of Val184G.hfs2.03 in linker 2/switch I at the opposite side of the inhibitor binding site did not impair heterotrimer stabilization by the inhibitors, as was the case for the Gβ mutants (Fig. 6 B, vi and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). These data further support the prominent role of inhibitor:Gβ interaction in heterotrimer stabilization.

In summary, both thermostability and BRET data demonstrate that the stabilization of the entire heterotrimer—and not just the Gα subunit—is an additional molecular feature in the mode of action of FR and YM.

Discussion

Large heterotrimeric G protein GTPases are guanine nucleotide-dependent switches essential for numerous cellular processes. Their signaling is GTP-dependent and tightly controlled—allosterically and through protein–protein interaction (PPI)—by several regulators: GEFs such as GPCRs, GAPs, and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) (6–9). Targeting of G proteins by small molecule or rationally designed peptide GDIs to control nucleotide cycling and signaling is known to be notoriously difficult (40). Two prominent exceptions are the natural cyclic depsipeptides FR and YM, which function as GDIs and fully silence the signaling of Gq, G11, and G14 with high specificity (15, 23). No other pharmacological agent even comes close to their effectiveness in suppressing the signaling of entire heterotrimers in living cells (40–42).

In this study, we use X-ray crystallography along with biochemical and cellular assays to provide a molecular explanation for their unique pharmacological behavior. Both inhibitors similarly lock GαGDP in its OFF-state by stabilizing the flexible hinge regions and constraining Ser53G.H1.02 in the P-loop in a position that is incompatible with activation. FR and YM also interact directly with two highly conserved residues in Gβ, Arg96 and Asp118, the former shielding both inhibitors, more tightly over FR than YM (Fig. 3C). We used site-directed mutagenesis, thermostability, as well as cellular BRET assays to unveil that FR and YM actively capitalize on the established GDI function of Gβγ by enhancing the protein–protein interaction between GαGDP and the Gβγ complex. Compellingly, replacing the key residues Arg96 and Asp118 by alanine (to remove Gβ:inhibitor interactions) or by leucine (to mask the inhibitors’ stabilizing effect), selectively attenuated (R96A) or abrogated (R96A/D118A; R96L) inhibitor-mediated Gα:Gβγ subunit interaction without affecting inhibition of G protein–intrinsic or ligand-induced Gq signaling. We term this feature of the natural cyclic depsipeptides “active heterotrimer stabilization,” differentiating it from the inhibition of intrinsic and GPCR-induced G protein signaling.

Based on our findings, we propose to reclassify the modes of action of Gq/11 inhibitors into two main classes: those that interdict Gα nucleotide exchange while tolerating the inhibitory occlusion of Gβγ, and those that inhibit Gα nucleotide exchange but compete with Gβγ in their action (Fig. 7). Only the former, epitomized by FR and YM, will securely lock entire heterotrimers in the OFF-state in living cells. Intriguingly, the two cyclic peptides not only tolerate Gβγ while inhibiting Gα, but even actively promote the PPI between the inhibited Gα and Gβγ through direct engagement of R96/D118:Gβ. Because Arg96 and Asp118 are highly conserved among Gβ subunits, this mechanism is likely to be generally applicable to the stabilization of Gq/11 heterotrimers, regardless of the combinatorial diversity of Gβγ subunit complexes. It might even be extended to other G protein subfamilies by engineering FR/YM-scaffolds with altered Gα recognition profiles. This stabilizing effect of the Gα:Gβγ heterotrimer is not to be confounded with the inhibition of nucleotide exchange on the Gα subunit, which does not require inhibitor interaction with Gβγ (23) and is therefore not affected by mutations within Gβ.

Fig. 7.

Schematic proposing a reclassification of GDIs for Gq/11 proteins/large G protein GTPases. FR/YM-type GDIs inhibit Gα nucleotide exchange while binding to Gβγ, whereas rationally designed nucleotide-state specific GDIs, often selected to bind to Switch II (14), may compete with Gβγ in their action. Therefore, FR- and YM-type GDIs inhibit signaling of large heterotrimeric G protein GTPases in living cells, whereas GDIs that compete with Gβγ prevent GDP release in vitro but potentially prolong Gβγ signaling in the living cell context.

Interestingly, there is a precedent for heterotrimer stabilization: The antibody fragment FAB16 (43) recognizes an interface between the N terminus of the Gαi and Gβγ subunits. Its binding to the interface moderately impairs heterotrimer dissociation, conferring some resistance to dissociation upon GTPγS addition. Unlike FR and YM, FAB16 is not selective for the nucleotide-binding state of the G protein. This suggests that the entire Gα–Gβ interface of G protein heterotrimers could be a target for structure-based drug screening to find new inhibitors acting as “Gα–Gβ glues” that fully hinder heterotrimer dissociation.

Our structures also allow the rationalization of observed structure–activity relationships of FR and YM synthetic derivatives (35, 44). Essentially, the reported (semi-)synthetic FR- and YM-based peptides harbor modifications at various positions that in most cases drastically reduce their inhibitory ability (45–47). Most natural analogs, however, present variations primarily at the acyl chain of anchor 1 (48). This indicates that there is room for structural variation specifically at the site, which is determinant for optimal inhibitor:Arg96/Gβ interaction and, consequently, for heterotrimer stabilization, but not in most other parts of the molecule. Interestingly, anchor 1 of FR is directed toward a polar pocket (Ser98 in Gβ and Arg202G.S3.04 in Gα) that contains several well-ordered water molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), suggesting that addition of polar groups at anchor 1 may further stabilize the Gα:Gβ–ligand interface. We anticipate that our high-resolution structures will contribute to the targeted development of new FR derivatives with the potential to explore the tunability of the Gα:Gβγ interaction.

Owing to their vital roles in the cell, dysregulation of G protein signaling is linked to a wide range of diseases (16, 18, 39, 49–57). For the same reason, nature may have “selected” G proteins as targets of particularly efficacious virulence factors. Prime examples include PTX, cholera toxin, and Pasteurella multocida toxin, members of the A-B toxin family, which enter host cells to access their G protein substrates and disrupt cellular function and physiology in multiple ways (58). In contrast to all natural compounds that securely and specifically perturb G protein function, the development of small molecules targeting heterotrimeric G proteins has been notoriously difficult (40). In this context, cyclic depsipeptides have emerged as promising alternatives in the search for inhibitors of this protein class (15, 23, 45, 59). GN13 and GD20 are two recent examples that either antagonize the Gαs ON-state (GN13) or sequester the Gαs OFF-state (GD20) (14). However, their cell permeable variants do not disable the signaling of entire Gs heterotrimers. FR and YM, on the contrary, securely lock entire heterotrimers in the inactive state (60). We recognize that heterotrimer stabilization by FR and YM is not necessary for the blunting of Gq/11 signaling (because inhibition of Gα does not require Gβγ), but we suggest that inhibition of Gα while simultaneously binding to Gβγ may be a strategy for maintaining both subunits of large GTPases in their inactive state. We anticipate this feature may become key to unlocking the inhibition of the remaining large G protein GTPases.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

FR900359 was isolated and purified from Chromobacterium vaccinii as described elsewhere (61, 62). YM-254890 was purchased from Fujifilm.

Protein Expression and Purification.

The G11iN3-S WT and R96A heterotrimer were expressed in High Five insect cells (Invitrogen, Waltham) and purified on ice or at 4 °C as described elsewhere (23) with small modifications, which are outlined in more detail in supplementary material.

Protein Crystallization, Data Collection and Processing.

Concentrated G11iN3-S WT heterotrimer solution was crystallized at 4 °C using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at a concentration of 32 mg/ml (370 µM) with a twofold molar excess of FR or YM. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland, and processed with autoPROC (63). The structures were solved by molecular replacement. Details are described in supplementary methods section.

GTPase Glo Assay® (Promega, Madison).

Reactions were set up in 384-well, low-volume, white, solid-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria) and carried out at 20 °C under dim-red light conditions. Each condition was prepared with N = 8. 2.5 µL of protein (±FR900359) solution containing 2 µM G11iN3-S, 0.2 µM dark-state or light-activated Jumping Spider Rhodopsin 1 (64) were mixed with 2.5 µL of 2 µM GTP solution. The plate was sealed and incubated for 180 min shaking at 500 rpm. Subsequently, 5 µl of GTP-Glo reagent was added to each well and the reaction was carried out for 30 min. Finally, 10 µl of Detection Reagent was added. Luminescence was measured after 5 min in a PheraStar FSX (BMG labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) plate reader (Optical module: LUM plus, Gain: 3,600, focal height:14, 1 s/well).

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry.

Melting temperatures were assessed using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) on a Prometheus Panta (NanoTemper Technologies GmbH, Munich, Germany). Purified G11iN3-S WT and G11iN3-S R96A were diluted in DSF buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 µM GDP, 100 µM TCEP) to 5 µM in the presence of FR or YM or an equivalent volume of DMSO. A twofold dilution series of each ligand (200 µM to 0.19 µM) was used to generate dose–response curves. After a 15-min incubation on ice, samples were analyzed using a linear temperature gradient ranging from 35 to 75 °C with a slope of 0.5 °C/min. Fluorescence was measured 33 times per °C, with the optimal excitation energy autodetected and set to 60%.

GCI.

Kinetic binding measurements were performed using GCI on a Creoptix WAVEdelta system (Creoptix—a Malvern Panalytical brand). All four flow channels of a PCH Creoptix WAVEchip (sensor chip) were conditioned according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The surface was activated by a 420-s injection of 0.4 M EDC [1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride] and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Purified wild-type G11iN3-S and G11iN3-S R96A were injected at 20 μg/ml in immobilization buffer (10 mM Na-Acetate, pH 4.5) onto separate flow channels and covalently coupled to a final level of 8,000 to 9,000 pg/mm2. The surface of all channels was passivated by a 420-s injection of 1 M Ethanolamine pH8 and then stabilized with several injections of running buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 μM GDP, 100 μM TCEP, 2% (v/v) DMSO). FR and YM were diluted from a 10 mM DMSO stock to 5 μM in running buffer and injected using the waveRAPID method (65) with 6 pulsed injections of increasing duration over 120 s, followed by 6,000 s of running buffer to follow ligand dissociation from wild-type G11iN3-S and G11iN3-S R96A. Data analysis was performed using the Creoptix WAVEcontrol software (Creoptix—a Malvern Panalytical brand). The response signals were double-referenced, subtracting the signal recorded on the reference channel without protein as well as the signal recorded from blank injections with running buffer. Double-referenced signals were fit to a heterogeneous analyte binding model, determining two sets of association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd), and dissociation constant (KD), as well as a maximum response (Rmax) and an apparent dissociation constant (App KD) for the interaction.

Chemicals for Cellular BRET and IP1 Accumulation Assays.

BRET substrate (Nano-Glo®) was purchased from Promega. DMEM, trypsin (0.05%), FCS, and HBSS were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The IP-One Gq Detection Kit was purchased from Revvity. Primers were from Invitrogen and enzymes for mutagenesis were from Promega. If not stated elsewhere, all other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmids for Cellular BRET and IP1 Accumulation Assays.

Plasmids encoding masGRK3ct-Nluc, Venus (1 to 155)-Gγ2, and Venus (155 to 239)-Gβ1 have been described previously (66) and were kindly provided by Kirill Martemyanov. Plasmids containing muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 (M3) or PTX-S1 cDNA in a pCAGGS backbone were a kind gift from Asuka Inoue. The plasmid encoding Gα11iN1-29 for mammalian expression was generated via Gibson Assembly. Mutations of the human Gα11 and Venus (156 to 239)-Gβ1 cDNA in pcDNA3.1 were generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol with small modifications (67). Double mutations in Venus (156 to 239)-Gβ1 were generated accordingly using Venus (156 to 239)-Gβ1 R96A as the template. Primers used for mutagenesis and cloning of Gα11iN1-29 for mammalian expression are detailed in SI Appendix, Table S3. Plasmids with the desired mutations were selected after DNA sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany).

Cell Lines/Cell Culture for Cellular BRET and IP1 Accumulation Assays.

CRISPR/Cas9 generation of HEK293 ∆Gq/11 and HEK293 Δ7 cells was reported elsewhere (15, 38). Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with FCS (10% V/V), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) and grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

BRET Assays.

Cells were transfected 24 h before the experiments using Polyethyleneimine (PEI, 1 mg/mL). Transfection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (DNA to PEI solution ratio 1:3). For activation and inhibition testing of G11 heterotrimers, approximately 2.8 × 106 cells were seeded into 10-cm dishes and immediately transfected with plasmids containing the following cDNA (amounts per dish): M3 receptor (1.5 µg), masGRK3ct-Nluc (0.4 µg), wild-type or mutant Venus (156 to 239)-Gβ1 (0.4 µg), (1 to 155)-Gγ2 (0.4 µg), wild-type or mutant Gα11 (0.8 µg), PTX-S1 (0.4 µg). Empty pcDNA3.1 vector was added to a total DNA amount of 5 µg per condition. Cells were washed with PBS, detached with trypsin, and centrifuged at 130×g for 3 min. After washing with PBS, cells were centrifuged again and resuspended in BRET buffer (HBSS supplemented with 20 mM HEPES). Approximately 80,000 cells per well were seeded into white 96-well flat bottom plates (Corning, Corning). For carbachol concentration–response curves, cells were mixed with Nano-Glo (final dilution 1:1,000) and agonist. For inhibitor concentration–response curves, cells were incubated with inhibitor in BRET buffer for 15 min. All inhibitor dilutions and the buffer control were equalized to the same DMSO content. Afterward, cells were mixed with Nano-Glo (final dilution 1:1,000) and agonist. After approximately one minute of incubation, luminescence (475 nm ± 30 nm) and fluorescence (535 nm ± 30 nm) were measured using the BMG PHERAstar® FSX plate reader for 0.48 s once per minute for 5 min at 28 °C. The BRET ratio was calculated by dividing fluorescence emission values by luminescence emission values. BRET signals in concentration–response curves are means of the fourth and fifth (minute) measurement shown as an increase in BRET ratio over buffer. For measuring heterotrimer stabilization, approximately 350,000 cells per well were seeded into 6-well plates and were transfected 24 h later with plasmids containing the following cDNA (amounts per dish): masGRK3ct-Nluc (0.025 µg), wild-type or mutant Venus (156 to 239)-Gβ1 (0.2 µg), (1 to 155)-Gγ2 (0.2 µg), wild-type or mutant Gα11 (1 µg), PTX-S1 (0.05 µg). Empty pcDNA3.1 vector was added to a total DNA amount of 2 µg per well. Cells were washed with PBS, detached by gentle scraping, centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min, and resuspended in BRET buffer (HBSS supplemented with 20 mM HEPES). Approximately 20,000 cells per well were seeded into white 96-well flat bottom plates (Corning, Corning) and mixed with Nano-Glo to a final concentration of 1:1,000. After five minutes of incubation, luminescence (475 nm ± 30 nm) and fluorescence (535 nm ± 30 nm) were measured using the BMG PHERAstar® FSX plate reader for 2.88 s every 15 s for 20 min at 28 °C. Inhibitor dilutions or DMSO-adjusted BRET buffer were added manually after 120 s of baseline read. The BRET ratio was calculated by dividing fluorescence emission values by luminescence emission values. BRET signals in kinetic measurements are shown as buffer-corrected increase in BRET ratio over baseline by subtracting the mean of the baseline-read and buffer values corresponding to each data point.

IP1 Accumulation Assay.

IP1 accumulation was measured with homogeneous time resolved fluorescence (HTRF) technology using the IP-One Gq Detection Kit (Revvity) following the manufacturer’s instructions. HEK ∆Gq/11 cells were transfected as described above (cf. BRET assays, for measuring heterotrimer stabilization). 28 h after transfection, cells were trypsinized and washed in PBS. After resuspension in LiCl-containing assay buffer to stop the breakdown of IP1, cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells per well into white 384-well plates. Buffer, FR900359, or YM-254890 were added to a final concentration of 10 µM. After 60 min of incubation at 37 °C to allow accumulation of intrinsically produced IP1, cells were lysed and incubated with the kit’s detection reagents for 60 min at room temperature. HTRF ratio values were measured using a Mithras LB 940 plate reader (Berthold Technologies). IP1 concentrations in nM were calculated using a previously recorded standard curve.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Appendix 02 (PDF)

Appendix 03 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (MTZ)

Dataset S02 (PDB)

Dataset S03 (MTZ)

Dataset S04 (PDB)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project numbers 290827466/FOR2372 (Grants CR464/7-1 to M.C., KO 902/17-2 to G.M.K., 216619161 to G.S., 418513893 to X.D., 290847012 to E.K., and 494832089/GRK2873 to E.K. and L.J.), and the Swiss NSF—Project numbers 192780 (to X.D.) and 183563 (to G.S., under the Sinergia program) for funding. M.J.R. received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant agreement No. 701647. We thank the SLS beamline scientists for their support during crystallography data collection.

Author contributions

G.S., E.K., and X.D. designed research; J.M., J.A., M.J.R., L.J., R.G.-G., L.G., F.A., A.B., and H.S. performed research; M.C. and G.M.K. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.M., J.A., M.J.R., L.J., R.G.-G., L.G., F.A., A.B., M.H., H.S., E.K., and X.D. analyzed data; and J.M., J.A., E.K., and X.D. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

A.B., F.A., and M.H. are current employees of the company leadXpro AG. G.S. is a co-founder and scientific advisor of leadXpro AG and InterAx Biotech AG.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Gebhard Schertler, Email: gebhard.schertler@psi.ch.

Evi Kostenis, Email: kostenis@uni-bonn.de.

Xavier Deupi, Email: xavier.deupi@psi.ch.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Coordinates and structure factors data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDBids: 8QEG (68) and 8QEH (69)).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Gilman A. G., G proteins: Transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56, 615–649 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldham W. M., Hamm H. E., Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 60–71 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milligan G., Kostenis E., Heterotrimeric G-proteins: A short history. Br J. Pharmacol. 147, S46–S55 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston C. A., Siderovski D. P., Receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins: Current structural insights. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 219–230 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wettschureck N., Offermanns S., Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol. Rev. 85, 1159–1204 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimple A. J., Bosch D. E., Giguere P. M., Siderovski D. P., Regulators of G-protein signaling and their Galpha substrates: Promises and challenges in their use as drug discovery targets. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 728–749 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprang S. R., Invited review: Activation of G proteins by GTP and the mechanism of Galpha-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis. Biopolymers 105, 449–462 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siderovski D. P., Willard F. S., The GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs of heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunits. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 1, 51–66 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuho I., et al. , A global map of G protein signaling regulation by RGS proteins. Cell 183, 503–521.e519 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert N. A., Dissociation of heterotrimeric g proteins in cells. Sci. Signal 1, re5 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangmool S., Kurose H., G(i/o) protein-dependent and -independent actions of Pertussis Toxin (PTX). Toxins (Basel) 3, 884–899 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Littler D. R., et al. , Structure-function analyses of a pertussis-like toxin from pathogenic Escherichia coli reveal a distinct mechanism of inhibition of trimeric G-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 15143–15158 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keen A. C., et al. , OZITX, a pertussis toxin-like protein for occluding inhibitory G protein signalling including Galpha(z). Commun. Biol. 5, 256 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai S. A., et al. , State-selective modulation of heterotrimeric Galphas signaling with macrocyclic peptides. Cell 185, 3950–3965.e3925 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrage R., et al. , The experimental power of FR900359 to study Gq-regulated biological processes. Nat. Commun. 6, 10156 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annala S., et al. , Direct targeting of Galphaq and Galpha11 oncoproteins in cancer cells. Sci. Signal 12, eaau5948 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onken M. D., et al. , Targeting nucleotide exchange to inhibit constitutively active G protein alpha subunits in cancer cells. Sci. Signal 11, eaao6852 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapadula D., et al. , Effects of oncogenic Galpha(q) and Galpha(11) inhibition by FR900359 in uveal melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 17, 963–973 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klepac K., et al. , The Gq signalling pathway inhibits brown and beige adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 7, 10895 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthey M., et al. , Targeted inhibition of G(q) signaling induces airway relaxation in mouse models of asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaag2288 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlegel J. G., et al. , Macrocyclic Gq protein inhibitors FR900359 and/or YM-254890-Fit for Translation?. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 4, 888–897 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todd T. D., et al. , Stabilization of interdomain closure by a G protein inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 121, e2311711121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura A., et al. , Structural basis for the specific inhibition of heterotrimeric Gq protein by a small molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13666–13671 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda S., Qu Q., Robertson M. J., Skiniotis G., Kobilka B. K., Structures of the M1 and M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor/G-protein complexes. Science 364, 552–557 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voss J. H., et al. , Unraveling binding mechanism and kinetics of macrocyclic Galphaq protein inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 173, 105880 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandy-Szekeres G., et al. , The G protein database, GproteinDb. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D518–D525 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman D. E., Sprang S. R., Crystal structures of the G protein Gi alpha 1 complexed with GDP and Mg2+: A crystallographic titration experiment Biochemistry 37, 14376–14385 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higashijima T., Ferguson K. M., Sternweis P. C., Smigel M. D., Gilman A. G., Effects of Mg2+ and the beta gamma-subunit complex on the interactions of guanine nucleotides with G proteins J. Biol. Chem. 262, 762–766 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voss J. H., et al. , Unraveling binding mechanism and kinetics of macrocyclic G alpha(q) protein inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 173, 105880 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumdar S., Ramachandran S., Cerione R. A., Perturbing the linker regions of the alpha-subunit of transducin: A new class of constitutively active GTP-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40137–40145 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heydorn A., et al. , Identification of a novel site within G protein alpha subunits important for specificity of receptor-G protein interaction. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 250–259 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh G., Ramachandran S., Cerione R. A., A constitutively active Galpha subunit provides insights into the mechanism of G protein activation. Biochemistry 51, 3232–3240 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darby J. F., et al. , Water networks can determine the affinity of ligand binding to proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15818–15826 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmoud A. H., Masters M. R., Yang Y., Lill M. A., Elucidating the multiple roles of hydration for accurate protein-ligand binding prediction via deep learning. Commun. Chem. 3, 19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reher R., et al. , Deciphering specificity determinants for FR900359-derived Gq alpha inhibitors based on computational and structure-activity studies. ChemMedChem 13, 1634–1643 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tietze D., et al. , Structural and dynamical basis of G protein inhibition by YM-254890 and FR900359: An inhibitor in action. J. Chem. Inf Model 59, 4361–4373 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonifer C., et al. , Structural response of G protein binding to the cyclodepsipeptide inhibitor FR900359 probed by NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Sci. 15, 12939–12956 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hisano Y., et al. , Lysolipid receptor cross-talk regulates lymphatic endothelial junctions in lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1582–1598 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lohmann K., et al. , Novel GNB1 mutations disrupt assembly and function of G protein heterotrimers and cause global developmental delay in humans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 1078–1086 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell A. P., Smrcka A. V., Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signalling by blocking G proteins. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 789–803 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmitz A. L., et al. , A cell-permeable inhibitor to trap Galphaq proteins in the empty pocket conformation. Chem. Biol. 21, 890–902 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charpentier T. H., et al. , Potent and selective peptide-based inhibition of the G protein Galphaq. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 25608–25616 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maeda S., et al. , Development of an antibody fragment that stabilizes GPCR/G-protein complexes. Nat. Commun. 9, 3712 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voss J. H., et al. , Structure-affinity and structure-residence time relationships of macrocyclic Galpha(q) protein inhibitors. iScience 26, 106492 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taniguchi M., et al. , YM-254890 analogues, novel cyclic depsipeptides with Galpha(q/11) inhibitory activity from Chromobacterium sp. QS3666. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12, 3125–3133 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong X. F., et al. , Total synthesis and structure-activity relationship studies of a series of selective G protein inhibitors. Nat. Chem. 8, 1035–1041 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaur H., Harris P. W., Little P. J., Brimble M. A., Total synthesis of the cyclic depsipeptide YM-280193, a platelet aggregation inhibitor. Org. Lett. 17, 492–495 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanke W., et al. , Feature-based molecular networking for the targeted identification of Gq-inhibiting FR900359 derivatives. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 1941–1953 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martemyanov K. A., Sampath A. P., The transduction cascade in retinal ON-bipolar cells: Signal processing and disease. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 3, 25–51 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marivin A., et al. , Dominant-negative Galpha subunits are a mechanism of dysregulated heterotrimeric G protein signaling in human disease. Sci. Signal 9, ra37 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farfel Z., Bourne H. R., Iiri T., The expanding spectrum of G protein diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 1012–1020 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Hayre M., et al. , The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 412–424 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dryja T. P., Hahn L. B., Reboul T., Arnaud B., Missense mutation in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of rod transducin in the Nougaret form of congenital stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 13, 358–360 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuchs T., et al. , Mutations in GNAL cause primary torsion dystonia. Nat. Genet. 45, 88–92 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar K. R., et al. , Mutations in GNAL: A novel cause of craniocervical dystonia. JAMA Neurol. 71, 490–494 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kostenis E., Pfeil E. M., Annala S., Heterotrimeric G(q) proteins as therapeutic targets? J. Biol. Chem. 295, 5206–5215 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Raamsdonk C. D., et al. , Mutations in GNA11 in Uveal Melanoma. New Engl. J. Med. 363, 2191–2199 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson B. A., Ho M., Pasteurella multocida toxin interaction with host cells: Entry and cellular effects. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 361, 93–111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takasaki J., et al. , A novel Galphaq/11-selective inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47438–47445 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White A. D., et al. , G(q/11)-dependent regulation of endosomal cAMP generation by parathyroid hormone class B GPCR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 7455–7460 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanke W., et al. , The bacterial G(q) signal transduction inhibitor FR900359 impairs soil-associated nematodes. J. Chem. Ecol. 49, 549–569 (2023), 10.1007/s10886-023-01442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hermes C., et al. , Thioesterase-mediated side chain transesterification generates potent Gq signaling inhibitor FR900359. Nat. Commun. 12, 144 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vonrhein C., et al. , Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 293–302 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varma N., et al. , Crystal structure of jumping spider rhodopsin-1 as a light sensitive GPCR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 14547–14556 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kartal O., Andres F., Lai M. P., Nehme R., Cottier K., waveRAPID-A Robust Assay for High-Throughput Kinetic Screens with the Creoptix WAVEsystem. SLAS Discov 26, 995–1003 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Masuho I., et al. , Distinct profiles of functional discrimination among G proteins determine the actions of G protein-coupled receptors. Sci. Signal 8, ra123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng L., Baumann U., Reymond J. L., An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e115 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muehle J., Rodrigues M. J., Guixa-Gonzalez R., Deupi X., Schertler G. F. X., Crystal structure of the G11 protein heterotrimer bound to YM-254890 inhibitor. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8QEG. Deposited 31 August 2023.

- 69.Muehle J., Rodrigues M. J., Guixa-Gonzalez R., Deupi X., Schertler G. F. X., Crystal structure of the G11 protein heterotrimer bound to FR900359 inhibitor. Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8QEH. Deposited 31 August 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Appendix 02 (PDF)

Appendix 03 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (MTZ)

Dataset S02 (PDB)

Dataset S03 (MTZ)

Dataset S04 (PDB)

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates and structure factors data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDBids: 8QEG (68) and 8QEH (69)).