Abstract

The symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum (B.japonicum) enables high soybean yields with little or no nitrogen fertiliser. A two component regulatory system comprising FixL, a histidine kinase with O2-sensing activity, and FixJ, a response regulator, controls the expression of genes involved in nitrogen fixation, such as fixK and nifA. Only under anaerobic conditions, the monophosphate group is transferred from FixL to the N-terminal receiver domain of FixJ (FixJN), which eventually promote the association of the C-terminal effector domain (FixJC) to the promoter regions of the nitrogen-fixation-related genes. Structural biological analyses carried out so far for rhizobial FixJ molecules have proposed a solution structure for FixJ that differs from the crystal structures, in which the two domains are extended. To understand the FixJ activation caused by phosphorylation of the N-terminal domain, which presumably regulates through the interactions between FixJN and FixJC, here we have performed backbone and sidechain resonance assignments of the unphosphorylated state of B. japonicum FixJ.

Keywords: Two component regulatory system, Response regulator, Nitrogen fixation, Multi domain protein

Biological context

Rhizobia are bacteria that can live in the roots of leguminous plants and form rhizoids. Rhizobia have a symbiotic relationship in which they convert atmospheric nitrogen molecules into ammonia (nitrogen fixation) by nitrogenases, which is supplied to plants, and receive photosynthetic products from the plants. Since nitrogenase is quickly inactivated when exposed to molecular oxygen, rhizobium bacteria have a sophisticated two component regulatory system (TCS) (Urao et al. 2000; Chauhan and Calderone 2008; Gotoh et al. 2010) consisting of two proteins, FixL and FixJ (Gilles-Gonzalez et al. 1991; Gong et al. 1998), to express genes involved in nitrogen fixation only in the absence of O2 (David et al. 1988).

Bradyrhizobium japonicum forms symbiotic relationships particularly with soybeans. B. japonicum FixL is a histidine kinase (HK) comprising N-terminal tandem Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domains, PAS-A and PAS-B, followed by a C-terminal dimerisation and histidine phosphotransfer (DHp) domain and a catalytic adenosine triphosphate-binding (CA) domain. Unlike many other TCS HKs, which are integrated into the membrane, B. japonicum FixL is water soluble and cytoplasmic, and uses a haem b cofactor bound to the PAS-B domain to sense O2 (Gilles-Gonzalez et al. 1994; Gong et al. 1998). B. japonicum FixJ is a response regulator (RR) consisting of an N-terminal receiver (REC) domain (FixJN) and a C-terminal effector domain (FixJC) that binds to DNA.

Under anaerobic conditions the hydrolysis of ATP at the CA domain and the autophosphorylation at His-291 in the DHp domain occur. The monophosphate group is subsequently transferred to the sidechain of Asp-55 in FixJN through the FixL-FixJ interaction, which eventually promotes the association of the helix-turn-helix motif of FixJC to the promoter regions of nitrogen-fixation-related genes, such as fixK and nifA (Wright et al. 2018).

Structural biological analyses have been carried out for FixJ, including for related species. First, the structure of FixJN of Sinorhizobium meliloti was determined by X-ray crystallography (Birck et al. 1999; Gouet et al. 1999). Next, the solution structure of S.meliloti FixJC was determined by NMR, and its interaction with dsDNA containing fixK promoter sequence was also analysed (Kurashima-Ito et al. 2005). Recently the crystal structures of full-length FixJ of B. japonicum were determined, in which multiple interdomain orientations were found, caused by the bending of the α-helix connecting FixJN and FixJC at different angles around Ala-123 (Wright et al. 2018). However, it turned out that no crystallographic conformer fitted the experimental SAXS data for full-length FixJ well, which suggests that FixJ in solution has more compact interdomain orientations on average (Wright et al. 2018).

To understand the mechanism of FixJ activation caused by phosphorylation of the N-terminal domain, the interactions between FixJN and FixJC in solution need to be analysed in detail. Therefore, as a first step, we initiated the heteronuclear multi-dimensional NMR study of the unphosphorylated state of B. japonicum FixJ (BjFixJ) for the assignment of the backbone and sidechain NMR resonances, which will provide a framework for the further analysis of 3D structure and dynamics of BjFixJ in solution.

Methods and experiments

Protein expression and purification

The gene encoding B. japonicum FixJ (BjFixJ) was cloned into a pET-22b(+) vector (Novagen) as an N-terminal His-tag-SUMO-fusion protein, and the resulting plasmid was introduced into the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) star strain (Invitrogen). For NMR experiments, uniformly 13C and 15N-labelled (13C/15N-) and uniformly 2H, 13C and 15N-labelled (2H/13C/15N-) samples were prepared. For 13C/15N-labelling, the transformed bacteria were grown at 37 °C in M9 minimal medium containing 2 g/L [13C6] D-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) and 1 g/L 15NH4Cl (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) as the sole carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. For 2H/13C/15N-labelling, the 13C/15N-labelled M9 medium was prepared with 95% D2O (Sigma-Aldrich). At a turbidity of ~ 0.5 OD (600 nm), expression of the protein was induced by the addition of isopropyl thio-β-D-thiogalactoside to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 18–20 h of further growth at 18 °C, the cells were harvested, washed and stored at -80 °C.

All the purification procedures described below were performed at 4 °C. The cells were washed once, centrifuged and resuspended to 0.1 g of cell paste/mL with lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 0.01% NP-40, 25% sucrose and protease inhibiter cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific)]. The cells were lysed with lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL) for 15 min, and the solution was incubated with DNase I (0.1 mg/mL), 0.5% NP-40 and 5 mM MgCl2 for 15 min. Further cell lysis was performed by using ultrasonication. The soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation at 30000g for 30 min.

The His-tag-SUMO-BjFixJ was purified using a Ni–NTA agarose affinity column (QIAGEN) pre-equilibrated with purification buffer A [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP), 10% Glycerol]. The fractions eluted using a 0−250 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) gradient were collected, and the N-terminal His-tag-SUMO part was cleaved with an incubation for overnight with SENP2 protease which is prepared as a GST-fusion protein. The cleaved BjFixJ were obtained by collecting flow-through fractions from sequential Ni-NTA and Glutathione Sepharose (Cytiva) column chromatography steps. Further purification of BjFixJ was achieved using a Superdex 75 pg HiLoad™ 16/600 (Cytiva) gel-filtration column pre-equilibrated with purification buffer B [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP].

The purified protein samples were concentrated (0.3 mM) and dissolved in NMR buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl] containing 10% D2O for NMR lock using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (Millipore). This buffer condition and the sample concentration were selected after optimisation, since BjFixJ showed concentration-dependent nonspecific association.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were performed at a probe temperature of 25 °C on a Bruker Avance-III HD 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic triple-resonance probehead. All 2D NMR spectra were processed using the Azara 2.8 software suite (Wayne Boucher and Department of Biochemistry, The University of Cambridge). For all 3D/4D NMR data, a non-uniform sampling scheme was used for the indirectly observed dimensions to reduce experimental time. Either quantitative maximum entropy (QME) (Hamatsu et al. 2013) or compressive sensing with CambridgeCS software (Mark J. Bostock, Robert Tovey and Daniel Nietlispach, Department of Biochemistry, The University of Cambridge) (Bostock et al. 2012) were used for processing non-uniformly sampled indirect dimensions. All spectra were visualised and analysed using the CcpNmr Analysis 2.5.2 software (Vranken et al. 2005).

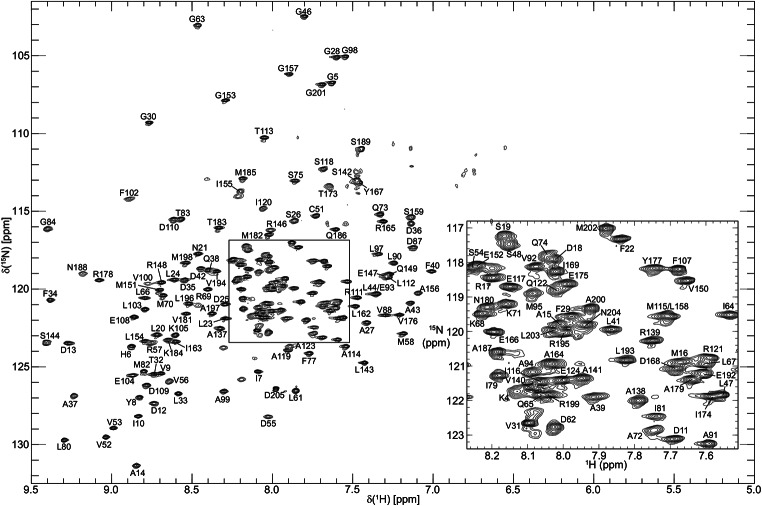

Backbone 1HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13C’, and sidechain 13Cβ resonance assignments of BjFixJ were performed by analysing six 3D TROSY-type triple-resonance NMR spectra, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CB, HN(COCA)CB, HN(CA)CO and HNCO measured on the 2H/13C/15N-labelled sample. The 2D 1H-15N-TROSY-HSQC spectrum of BjFixJ annotated with the assignments is shown in Fig. 1. Aliphatic sidechain 1H and 13C resonances were assigned by analysing 3D HBHA(CBCACO)NH, H(CCCO)NH, (H)CC(CO)NH, and HCCH-TOCSY experiments measured on the 13C/15N-labelled sample. As an example of the sidechain resonance assignment, the methyl-region of the 2D 1H-13C HSQC annotated with the assignments is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum of 0.3 mM 2H/13C/15N-labelled B. japonicum FixJ acquired on a Bruker Avance III HD 600 spectrometer at 25˚C, pH 8.0. Cross peaks are labelled with their corresponding backbone assignments

Fig. 2.

2D 1H-13 C constant-time HSQC spectrum of 0.3 mM 13C/15N-labelled B. japonicum FixJ acquired on a Bruker Avance III HD 600 spectrometer at 25˚C, pH 8.0. Mirror-image linear prediction in the t1 (13C) dimension was performed prior to Fourier transform. Only positive contours are shown. Cross peaks due to methyl groups of Ala, Ile, Leu, Thr, and Val residues are labelled with their corresponding assignments

3D 13C-separated NOESY, 3D 15N-separated NOESY and 4D 13C/15N-separated NOESY experiments were used for assigning aromatic 1H and 13C resonances as well as further confirmation of the assigned sidechain chemical shifts.

Extent of assignments and data deposition

1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shift assignments for BjFixJ were deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under the ID 26,351. As described, backbone resonance assignment was performed using the 2H/13C/15N-labelled sample, while sidechain resonances were analysed using the 13C/15N-labelled sample. For BMRB-deposition, chemical shifts for protonated 13Cα and 13Cβ were used.

BjFixJ consists of 205 amino acid residues containing 9 proline residues. If there is no conformational multiplicity with a slow exchange regime, there are therefore a total of 195 observable 1H-15N correlation cross peaks due to backbone amide groups in the 2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra, excluding the N-terminal amino group as well. For backbone resonances, we assigned them in the assignment completeness of 86.7% for 1HN (169/195), 86.7% for 15N (169/195), 86.8% for 13Cα (178/205), 86.3% for 13Cβ (177/205), and 87.3% for 13C’ (179/205).

The secondary structure of BjFixJ was predicted by TALOS-N (Shen and Bax 2013) based on the assigned resonances (Fig. 3). For FixJN and FixJC the βαβαβαβαβα and ααααα folds were found, which is consistent with previously reported structural biological results on FixJ as a whole and of each domain.

Fig. 3.

a. Secondary structure probabilities for B. japonicum FixJ predicted by TALOS-N (Shen and Bax 2013). Blue and red bars represent probabilities that the corresponding residues form β-strand or α-helix, respectively. The confidence in the prediction at each residue is indicated by a black dot. Grey regions represent the residues for which secondary structure prediction based on the chemical shifts was not performed due to the lack of assignments. b. Schematic diagram of the predicted secondary structures

The incompleteness in the backbone resonance assignments was presumably caused by line broadening of cross peaks in the 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum, thus providing scarcely observable cross peaks in triple-resonance spectra for these 1HN-15N correlations. Incomplete exchange of amide 2H to 1H in the 2H/13C/15N-labelled sample was ruled out, since almost all the 1H-15N correlation cross peaks found in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the protonated sample were indeed observed in the 1H-15 N TROSY-HSQC spectrum of the deuterated sample as well. The residues with missing amide-assignments were Thr-2, Thr-3, Phe-49, Gly-50, Gly-60, His-85, Gly-86, Lys-96, Asp-101, Ala-126-Ile-136, Asn-160, Lys-161, Ser-170, Arg-172, Leu-190 and Ser-191. These “unassigned” residues are all localised at the N-terminus (Thr-2 and Thr-3) or in loop regions between α2 and β3 (Phe-49 and Gly-50), β3 and α3 (Gly-60), β4 and α4 (His-85 and Gly-86), α4 and β5 (Lys-96 and Asp-101), α5 and α6 (Ala-126-Ile-136), α7 and α8 (Asn-160 and Lys-161), α8 and α9 (Ser-170 and Arg-172), and α9 and α10 (Leu-190 and Ser-191) and are therefore likely to be exposed to the solvent. Since the NMR experiments were carried out at pH 8, the exchange of amide protons due to these residues with the solvent presumably caused significant line broadening of these resonances. On the other hand, the Ala-126–Ile-136 residues were localised following Ala-123, which is the exact location where the bending of the α-helix connecting FixJN and FixJC was observed in the crystal structures. Thus changes in the relative orientation of two domains in solution may also explain the exchange broadening of the 1HN-15N correlation cross peaks for the residues. The predicted secondary structure, in which a loop structure was suggested for Ala-123 and Glu-124, also supports the flexibility of the region in solution with wider area than that observed in the crystal structures.

For sidechain 1H/13C resonances, roughly 84.5% of aliphatic and 54.5% of aromatic chemical shifts were identified. In addition 91.7% (11/12) of sidechain NH2 groups were assigned. The assignments obtained in this study will be used in the analysis of the detailed 3D structure and dynamics of the unphosphorylated FixJ. Comparison with NMR results of phosphorylated FixJ in the future should also help to understand the mechanism of FixJ activation caused by the Asp-55 phosphorylation.

Author contributions

H.S., Y.S., T.I. and Y.I. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. A.H., and R.O. conducted the research including sample preparation, data acquisition, and resonance assignment. K.K.-I. and P.M.S. helped with NMR data analysis. N.H., R.W. and H.K. helped with optimising the conditions for stable isotope-labelling. K.I. and M.M. helped with NMR measurements.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tokyo Metropolitan University.

This work was supported by grants from the Funding Program for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST; JPMJCR13M3 to Y.I., JPMJCR21E5 to T.I.) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP22H02562 and JP24H02094 to M.M., JP15K06979 to T.I., JP19H05645, JP24H0129 to Y.I.) and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (JP15H01645, JP16H00847, JP17H05887 and JP19H05773 to Y.I. JP26102538, JP25120003, JP16H00779 and JP21K06114 to T.I.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Data availability

1 H, 13 C, and 15N chemical shift assignments for Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixJ were deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under ID 26351.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Akio Horikawa and Rika Okubo contributed equally to this work.

References

- Birck C, Mourey L, Gouet P, Fabry B, Schumacher J, Rousseau P, Kahn D, Samama JP (1999) Conformational changes induced by phosphorylation of the FixJ receiver domain. Structure 7:1505–1515. 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88341-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock MJ, Holland DJ, Nietlispach D (2012) Compressed sensing reconstruction of undersampled 3D NOESY spectra: application to large membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR 54:15–32. 10.1007/s10858-012-9643-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Calderone R (2008) Two-component signal transduction proteins as potential drug targets in medically important fungi. Infect Immun 76:4795–4803. 10.1128/iai.00834-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M, Daveran ML, Batut J, Dedieu A, Domergue O, Ghai J, Hertig C, Boistard P, Kahn D (1988) Cascade regulation of Nif gene expression in Rhizobium meliloti. Cell 54:671–683. 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80012-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles-Gonzalez MA, Ditta GS, Helinski DR (1991) A haemoprotein with kinase activity encoded by the oxygen sensor of Rhizobium meliloti. Nature 350:170–172. 10.1038/350170a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles-Gonzalez MA, Gonzalez G, Perutz MF, Kiger L, Marden MC, Poyart C (1994) Heme-based sensors, exemplified by the kinase FixL, are a new class of heme protein with distinctive ligand binding and autoxidation. Biochemistry 33:8067–8073. 10.1021/bi00192a011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, Hao B, Mansy SS, Gonzalez G, Gilles-Gonzalez MA, Chan MK (1998) Structure of a biological oxygen sensor: a new mechanism for heme-driven signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15177–15182. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh Y, Eguchi Y, Watanabe T, Okamoto S, Doi A, Utsumi R (2010) Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:232–239. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P, Fabry B, Guillet V, Birck C, Mourey L, Kahn D, Samama JP (1999) Structural transitions in the FixJ receiver domain. Structure 7:1517–1526. 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88342-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamatsu J, O’Donovan D, Tanaka T, Shirai T, Hourai Y, Mikawa T, Ikeya T, Mishima M, Boucher W, Smith BO, Laue ED, Shirakawa M, Ito Y (2013) High-resolution heteronuclear multidimensional NMR of proteins in living insect cells using a baculovirus protein expression system. J Am Chem Soc 135:1688–1691. 10.1021/ja310928u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashima-Ito K, Kasai Y, Hosono K, Tamura K, Oue S, Isogai M, Ito Y, Nakamura H, Shiro Y (2005) Solution structure of the C-terminal transcriptional activator domain of FixJ from Sinorhizobium meliloti and its recognition of the fixK promoter. Biochemistry 44:14835–14844. 10.1021/bi0509043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Bax A (2013) Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J Biomol NMR 56:227–241. 10.1007/s10858-013-9741-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urao T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (2000) Two-component systems in plant signal transduction. Trends Plant Sci 5:67–74. 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01542-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED (2005) The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinf 59:687–696. 10.1002/prot.20449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright GS, Saeki A, Hikima T, Nishizono Y, Hisano T, Kamaya M, Nukina K, Nishitani H, Nakamura H, Yamamoto M, Antonyuk SV, Hasnain SS, Shiro Y, Sawai H (2018) Architecture of the complete oxygen-sensing FixL-FixJ two-component signal transduction system. Sci Signal 11:eaaq0825. 10.1126/scisignal.aaq0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

1 H, 13 C, and 15N chemical shift assignments for Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixJ were deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) under ID 26351.