Abstract

Objective

To achieve satisfying function and appearance of nasal tip after tumor resection.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients with nasal tip tumors admitted between January 2010 and January 2024. A standardized data collection template was used to collect related variables. Tumors were all resected according to the guidelines, and the defects were repaired with different flaps. For nasal tip soft tissue defects smaller than 1 cm, a horn-shaped flap was used; for defects with a diameter of 1–2 cm, the bilobed flap was applied; for defects larger than 2 cm, frontonasal flap was designed.

Results

Twenty-eight patients were included in this study. All the skin defects were repaired according to the one-stage reconstruction strategy. All patients achieved primary healing without severe complications. Slight edema occurred in 5 patients, and slight infection occurred in 2 patients, all healed with dressing change in several days. Ideal aesthetic results achieved without distortion of the nasal tip or alar rim. During the follow-up period of 3–11 months, no tumor occurrence was observed.

Conclusion

The reconstruction strategy reported in this study is a promising way in the repair of nasal tip soft tissue defect with little complication and satisfying outcomes.

Keywords: nasal tip defect, horn-shaped flap, bilobed flap, frontonasal flap, nasal reconstruction

Introduction

Nose locates at the central part of the mid-face and plays an important role in functional and aesthetical aspects, including nasal respiration, olfaction, and phonation. The sun-exposure makes the nose one of the most common sites for the presentation of cutaneous cancer on the face. The nasal surface is made up of several concave and convex subunits—dorsum and paired sidewalls, nasal tip and paired alae, columella, and paired soft tissue facets. And the different skin texture of these subunits makes the repair of nasal defect more challenging than other areas. Specifically, the skin of the nasal tip and alae is thicker, more sebaceous, and less flexible, than the dorsum, columella, and sidewalls.1 Any small alterations in skin color or texture caused by surgery are obvious and may lead to suboptimal results.

Restoring the 3-dimensional original shape, symmetry establishment, and color and texture match to the adjacent structures are the goal of nasal defect reconstruction. There have been many flaps designed to repair nose skin defect, and the most ideal procedure is repairing based on the nasal subunits. Goldman and Wollina1 used nasolabial banner flaps to reconstruct alar, sidewall, and columnar nasal defects, bilobed flap to repair sidewall defects, and Rintala flap to reconstruct nasal dorsum and nasal tip defects. Other flaps include tunneled island flap and frontal flap have also been reported. This article describes an alternative method of repair for nasal tip defects using one-stage flaps depending on the size of the original skin defect.

Patients and Methods

Data Collection

Patients admitted to the Department of Plastic Surgery, Changhai Hospital, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China, between January 2010 and January 2024 were included in this retrospective study. Patients were all diagnosed with various nasal tumor and accept surgical removal and reconstruction. The exclusion criteria consisted of two specific clinical situations: defects smaller than 0.5 cm that could be closed primarily, and lesions larger than 2.5 cm with significant tissue loss that could not be effectively reconstructed with a single flap which requiring a multi-flap approach. Intraoperative and postoperative photographs included in this study were taken with patients’ consent. A standardized data collection template was used to collect variables including patient demographics, type of tumor, defect sizes, anatomic location and complications were collected. Descriptive analyses were performed, and the results are presented as the mean ± SD. The Changhai Hospital, Naval Medical University, granted approval for this study.

Tumor Resection and Flap Design

In our study, local infiltration anesthesia was administered to all patients. Specifically, lidocaine or ropivacaine with epinephrine were injected in the subfascial (SMAS) plane of the donor area for local anesthesia and preventing massive bleeding during surgery. Regarding tumor margin management, intraoperative frozen section pathology was routinely performed to evaluate tumor infiltration in both peripheral and basal surgical margins. For benign lesions, margin-controlled resection is performed. In the case of malignant mass, confirmed basal cell carcinoma (BCC) required 5 mm extended resection margins, while squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) necessitated 5–8 mm radical resection margins to achieve R0 clearance. Medical-grade drainage rubber sheets were placed in the subcutaneous tissue during wound closure and removed 5–7 days postoperatively if there are no complications such as infection or hematoma with minimal wound exudate.

For defects smaller than 1 cm, a horn-shaped flap was designed. The horn flap is a randomized local triangle flap with a straightforward design and a consistent blood supply which is based on a musculocutaneous flap. It is a dependable and adaptable flap for reconstructing the lateral and superior nasal tips, so it is utilized to repair minor regions of skin damage in our study. For the design of the flap, each incision was at the tangential position of the primary defect. The diameter of the lateral and medial curved incision is about 3 and 2 times of the defect diameter, respectively. The incisions were made, and the subcutaneous pedicle skin flap were transposed to cover the primary skin defect (Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

A case of a 56-years-old female with BCC. (A) Preoperative photograph of the lesion on the nose tip. (B) Intraoperative photograph of the wound after the removal of a tumor, with the markings of the flap. The defect area measuring 1.0×1.0 cm. (C) Immediate postoperative photograph demonstrating soft tissue coverage of the wound with horn-shaped flap. (D) Follow-up after three months demonstrating successful wound closure with ideal esthetic result. The front view (E) and right profile (F) taken 11 months after surgery.

For defects with a diameter of 1–2 cm, the bilobed flap was used. The design of the bilobed flap is described as follows. The flap is divided into two lobes, the first lobe is on the tangential position of the circular primary defect, and the second lobe is perpendicular to the first lobe and about half the size of the first lobe. The width of the first lobe should be equal to or slight larger than the width of the primary defect to avoid upward displacement of the nasal ala, and the length should be about one-third longer than the primary defect. The second lobe is to minimize tension when closing the secondary defect, and its size is variable. The distal end of the second lobe is designed to be 30 degrees sharp to facilitate the direct closure of the secondary defect after flap transposition (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

A case of a 77-years-old female with pleomorphic adenoma. (A) Intraoperative photograph of the wound after the removal of a tumor, with the markings of the flap. The defect area measuring 2.0×2.0 cm. (B) Immediate postoperative photograph demonstrating soft tissue coverage of the wound with bilobed flap. (C) Flap was well-survived five days after surgery. (D) Ten days after surgery and the sutures can be removed. The front view (E), the right profile (F and G), and the head tilted back view (H) taken 1 months after surgery.

For defects larger than 2 cm, frontonasal flap was applied. This flap is based on the branches of the angular artery and was designed at the area between dorsum and glabella. The incision between the eyebrow was designed to be inverted V-shaped, and the incision lines were designed at the naso-facial junction on both sides and naturally and smoothly transit to the defect. The tissue is dissected in the subcutaneous layer, and the flap is rotated and transferred to the defect. On the same side of the vascular pedicle, part of the skin tissue needs to be excised to avoid dog ear deformity. The secondary glabellar defect was sutured by V-Y plasty, and all wound edges were sutured without tension (Figure 3A–D).

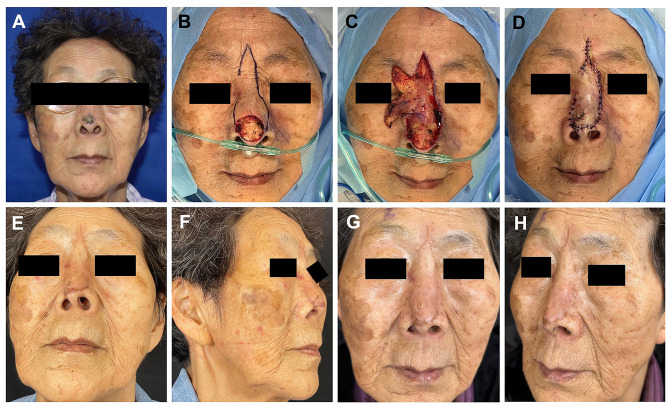

Figure 3.

A case of an 85-years-old female with BCC. (A) Preoperative photograph of the lesion on the nose tip. (B) Intraoperative photograph of the wound after the removal of a tumor, with the markings of the flap. The defect area measuring 2.7×2.5 cm. (C) Dissection of the flap. (D) Immediate postoperative photograph demonstrating soft tissue coverage of the wound with frontonasal flap. (E and F) Follow-up after 2 months demonstrating successful wound closure without distortion of nose tip. The front view (G) and left profile (H) taken 5 months after surgery.

Straticulate interrupted sutures were applied in all cases to carefully close the wound. Antibiotics should be administrated in the first 3–5 days after surgery to avoid infections from nasal mucosal lining, nasopharynx, or oropharynx. In some cases, negative pressure wound therapy was applied to assist wound healing and removed after 3–5 days. Patients were advised to keep the head elevated in the first few days after surgery to reduce edema, and any abnormal swelling or hematoma should be promptly treated to avoid flap necrosis.

Results

The prerequisite for stage-one defect closure after malignant tumor resection is a complete R0 resection of the tumor, which was accomplished in all our patients. A total of 28 patients with an average age of 63.4 years (range 5–85 years, standard deviation 19.7 years) were included. Fifteen (75%) patients were male and 13 (25%) were female. No patients were excluded based on age, demographics, or comorbidities.

All lesions in the nasal tips were sent for pathological analysis. BCC was diagnosed in 12 patients and SCC in 3 patients. R0 resection was achieved in all malignant tumors. The other lesions included were seborrheic keratosis (3 cases), verruca vulgaris (1 case), nevi (5 cases), trichoblastoma (1 case), keratoacanthoma (1 case), pleomorphic adenoma (1 case), and hamartomatoid lesions (1 case). A horn-shaped flap was the reconstructive option in 5 subjects, a bilobed flap was used in 11 patients, and frontonasal flap was used in 12 cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Divisional Reconstruction Strategy |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 63.4±19.7 |

| Sex | |

| -Male | 15 |

| -Female | 13 |

| Immunocompromised | |

| -Yes | 0 |

| -No | 28 |

| Tumor type | |

| -BCC | 12 |

| -SCC | 3 |

| -Benign lesions | 13 |

| Primary defect (length×width, cm, mean±SD) | (2.1±0.9)×(1.6±0.6) |

| Closure strategy | |

| -Horn-shaped flap | 5 |

| -Frontonasal flap | 12 |

| -Bilobed flap | 11 |

| Mean follow-up (months, mean±SD) | 4.9±1.8 |

All patients achieved primary healing. No severe complications like wound dehiscence, congestion, postoperative hematomas or major necrosis occurred, and all the flaps survived completely. Slight edema occurred in 5 patients, and slight infection occurred in 2 patients, manifesting as peri-incisional erythema with increased exudate. Given the negative bacterial culture results, sterile dressing changes were conducted twice a day, which led to complete wound healing in several days (Table 2). Moreover, there was no distortion of the nasal tip or alar rim. The postoperative healing process of the patients was generally favorable and well-tolerated (Figures 1D–F, 2C–F, 3E–H). During the follow-up period of 3–11 months, no tumor recurrence was observed.

Table 2.

Complications of All the Flaps

| Complications | No. of Flaps (%) |

|---|---|

| Delayed healing | 0 (0) |

| Slight edema | 5 (18) |

| Slight infection | 2 (7) |

| Significant events* | 0 (0) |

Notes: Significant events*: major infection, flap congestion, flap necrosis, flap loss (particle and total).

Discussion

Successful nasal skin defect reconstruction after complete tumor excision requires surgeons to master different surgical techniques to tailor the procedures based on tumor localization, size, and depth, and patients’ needs. Although single-stage flaps combined with grafts in facial defect repair may be easier and less time consuming, they can also lead to a poor cosmetic outcome. Burget and Menick improved nasal reconstruction techniques by establishing the aesthetic subunit principle.2 The reconstruction should follow the principles of cosmetic subunit repair. Specifically, Burget suggested that entire subunit reconstruction should be conducted if the defect is larger than 50% of the subunit. Multiple approaches has been reported in nasal repair, which including mucosal flaps, skin grafting, local flap, forehead flap, and free tissue transfer.3 Until now, various flaps have been applied depending on the size of the defect, skin quality, functionality and aesthetics, and the patient’s requirements.

The limited tissue mobility and lack of adequate tissue reservoir make simple linear closure on the nose difficult in most cases. Studies reported that for small skin defects, the dorsum defects can choose full thickness skin grafting (FTSG) and primary closure, rotation and cheek advancement flaps, and FTSG are options for the sidewall defects, and nasal tip defects can be repaired by advancement or rotation flaps, island pedicle flaps, and FTSG. The forehead flap is preferred for defects larger than 3 cm in these areas, and nasal ala reconstruction requires composite grafts or a forehead flap with a cartilage graft. To repair superficial defects of all subunits, healing by secondary intention is an option.4 Despite the advantage of reduced incision on nose, the FTSG can cause secondary damage to the donor site and involves prolonged wound care. However, FTSG should be considered in repairing defects in the thin skin of dorsum and sidewalls, or in patients with superficial defects, patients who refused multi-staged procedure or multiple flap harvest, and patients with severe medical comorbidities.

A study conducted by Park et al5 revealed that the most commonly used surgical technique for nasal ala reconstruction was the nasolabial flap, whereas for the nasal tip bilobed flaps were preferred. However, nasolabial flap has the risk of different color and texture, and blunting of nasal facial sulcus and alar groove.6 The application of bilobed or trilobed transposition flaps allow for the transposition of more mobile skin to reconstruct defects on the thick immobile skin of the nose tip. It is a single-stage procedure with a result of exceptional color and texture match but is often restricted to defects less than 1.5 cm diameter. However, some complications of bilobed flap including pincushioning, alar displacement and airflow obstruction have been reported due to individual suboptimal flap design and execution.7 Correa et al8 demonstrated that the paramedian forehead flap is an ideal choice and should be the gold standard for whole nasal reconstruction.

Some studies reported modified flaps for nasal repair. Zeikus et al6 designed a variation of an advancement flap for the reconstruction of partial thickness defects less than 1 cm on the nasal ala and lateral nasal tip. This flap can be laterally, medially, or bilaterally based, with sharply undermining with a scalpel blade in the subcutaneous plane (on the ala) or just above perichondrium (on the lateral tip). Hafiji et al9 reported a nasal sidewall (AIRNS) flap for reconstruction of the distal nose. It may be a possible alternative to the bilobed flap. But the application of AIRNS flap in the laterally based defects of the nasal alar may cause the blunting of the superior alar crease, which can be avoided by using the bilobed flap. Staged interpolation flaps or skin grafting are recommended for larger defects, in combination with autologous cartilage grafting if necessary.8,10

Furthermore, the Rintala flap, a rectangular flap made from the glabellar and nasal dorsum areas, is an additional alternative for correcting the nasal deformity. The flap maintains face symmetry since it runs along the midline. However, it would result in inadequate supply of blood surrounding the flap because this is a narrow pedicle flap. It is advised that the flap extend from the glabella to the middle part of the nasal dorsum to prevent necrosis.11,12 Besides, it may cause bilateral scars, and the restricted width is not appropriate for defects involving adjacent subunits.

Management of nasal skin cancers requires an accurate assessment of the extent of tumor excision, functional preservation, and aesthetic outcomes of postoperative reconstruction. As a result, a multidisciplinary team effort is required to ensure that the surgical team precisely diagnoses tumor margins, chooses appropriate flap types, and conducts precise vascular anastomosis and tissue repair during the operation. Nasal tip and alar skin reconstruction is prone to aesthetic complications such as contour deformities of larger flaps and hypertrophic scars. The incidence of complications was 24% in patients with nasal defects greater than 1.5 cm and 4.8% in those with defects less than 1.5 cm. However, the complication rate increased to 32% for the patients who smoked.13 To avoid bulky flap, the flap should be precisely matched or thinned to the thickness of the defect, while the hemostatic and drainage procedure need be adequately followed as well.

In our study, we designed the reconstruction strategy regarding the size of defects. The horn flap, a curved V-Y advancement flap with forward displacement and rotation features, is a versatile and reliable reconstruction method for the reconstruction. However, due to the potential for dog ear deformity or flap distortion during flap advancement, the horn flap is often appropriate for the restoration of small defects.14 The bilobed flap demonstrates enhanced biomechanical efficacy through its dual-lobed configuration, achieving simultaneous optimization of wound closure geometry and greater tissue mobilization distances compared to single-lobed counterparts, so it is an ideal flap for small defects <1.5 cm in the distal third of the nose.15 Knackstedt et al16 retrospectively analyzed 111 cases of nasal tip defects repaired with bilobed flaps, and postoperative erythema occurred in 4.5% without any serious complications. The frontonasal flap relies on a narrow skin bridge and provides ample supply of blood. By advancing and rotating the flap, the tissue is transferred from the donor site (glabella and nasal dorsum) to the deficiency area (nasal tip and alar). The frontonasal flaps can repair larger defects than bilobed flaps and are typically used to treat medium-sized deformities in the tip or dorsum of the nose.17 Elderly patients are particularly well-suited for correcting nasal abnormalities with frontonasal flap because of their loose skin.18 Nevertheless, all the procedure should be based on the preoperative consent from patients after generalized information about the risks and potential side effects of the surgery. Moreover, multi-staged surgery should be avoided in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, and skin grafts are not recommended in patients who are active smokers or have only recently quit. The strategy reported in this article is a one-staged procedure with excellent color and texture match. The surgical incisions will fade with time and are usually not noticeable to others. It can maintain the contour of the nasal tip or alar rim without blunting of the nasofacial sulcus.

The limitations of our study are listed as follows. Since this is a retrospective study, the height and width of the patients’ noses cannot be measured, and the scar formation rate is not available. The strategy cannot be applied in patients with little tissue mobility or defects larger than 2 cm. FTSG or divisional reconstruction can be applied in those cases.

Conclusion

The face serves as both a central hub for diverse physiological functions and the primary area of human aesthetic expression. It becomes crucial to take into account both practical restoration and cosmetic results while restoring the face defect. This requires a thorough evaluation of the patient’s regional anatomy, biomechanical properties, and defect-specific characteristics, such as size, depth, location, and involvement of underlying tissues. Nasal defect reconstruction demands particular attention to its multi-subunit architecture, where flap design should adhere to subunit boundaries to optimize postoperative contour symmetry and functional unity. Furthermore, interpatient variability significantly influences reconstructive effectiveness, as individual differences in cutaneous texture, thickness, elasticity, and vascular integrity directly inform flap selection criteria and surgical success rates. Consequently, reconstruction techniques must be precisely adjusted using a comprehensive examination of patient-specific characteristics in order to reduce complication risks while attaining optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes. In summary, our strategy based on the size of defects demonstrates the versatility of local flaps for defect closure on the nose. The treatment can be tailored according to the size of the defect to achieve excellent aesthetic and functional results.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Ethics Statement

This study complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring that all research procedures meet the required standards for the protection of human participants.

Informed Consent

In this study, the patients depicted in Figures 1-3 were fully informed that the images would be used for medical publication and consented to their use. Specifically, prior to the acquisition and use of the images, we thoroughly explained to the patients the purpose of the images, the potential scope of publication, and the potential implications following publication. Based on their complete understanding, the patients voluntarily signed written informed consent forms.

Disclosure

Minliang Wu, Xinyi Zhang, and Ang Li are co-first authors for this study. All authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Goldman A, Wollina U. Defect closure after successful skin cancer surgery of the nose: a report of 52 cases. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2020;29(4):209–214. doi: 10.15570/actaapa.2020.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burget G, Menick F. Aesthetic Reconstruction of the Nose, 2nd Ed. St. Louis, MO, USA: Mosby; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding F, Huang C, Sun D, et al. Combination of extended paramedian forehead flap and laser hair removal in the reconstruction of distal nasal defect. Ann Plastic Surg. 2021;86(3 Suppl 2):S293–S298. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wollina U, Bennewitz A, Langner D. Basal cell carcinoma of the outer nose: overview on surgical techniques and analysis of 312 patients. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg. 2014;7(3):143–150. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.146660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park YJ, Kwon GH, Kim JO, et al. Reconstruction of nasal ala and tip following skin cancer resection. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20(6):382–387. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeikus PS, Maloney ME, Jellinek NJ. Advancement flap for the reconstruction of nasal ala and lateral nasal tip defects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(6):1032–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook JL. Reconstructive utility of the bilobed flap: lessons from flap successes and failures. Dermatologic Surg. 2005;31(8 Pt 2):1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa BJ, Weathers WM, Wolfswinkel EM, et al. The forehead flap: the gold standard of nasal soft tissue reconstruction. Semin Plastic Surg. 2013;27(2):96–103. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafiji J, Salmon P, Hussain W. The AIRNS flap: an alternative to the bilobed flap for the repair of defects of the distal nose. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stiff KM, Fisher CC, Collins LK, et al. Multilobed flaps for intermediate and large nasal defects: flap characteristics, patient outcomes, and provider experience at two institutions. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthetic Surg. 2022;75(8):2757–2774. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitman T, Geerards D, Hoogbergen M. Nose tip defect reconstruction with a modified extended Rintala flap: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64(3):397–399. doi: 10.1111/ajd.14107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onishi K, Okada E, Hirata A. The Rintala flap: a versatile procedure for nasal reconstruction. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35(5):577–581. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berens AM, Akkina SR, Patel SA. Complications in facial Mohs defect reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25(4):258–264. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito O, Yano T, Kawazoe T, et al. Flexible curved V-Y subcutaneous flap for facial skin defects. plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global Open. 2015;3(10):e531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habib Bedwani N, Rizkalla M. Single-stage reconstruction of full-thickness nasal alar defect using bilobed and turnover flaps. J Craniofacial Surgery. 2020;31(2):e169–e171. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knackstedt T, Lee K, Jellinek NJ. The differential use of bilobed and trilobed transposition flaps in cutaneous nasal reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(2):511–519. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheufler O. Variations in frontonasal flap design for single-stage reconstruction of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(6):1032e–1042e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldosari BF. The axial frontonasal flap for nasal tip defect: a single centre experience. Cureus. 2019. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]