Abstract

Objective

Tyramide signal amplification (TSA)-induced Opal multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) represents an advanced methodology for the in-situ detection of multiple target proteins. A critical aspect of this technique is the complete removal of primary and secondary antibodies to prevent signal cross-reaction. However, current antibody stripping methods exhibit several limitations, particularly when applied to tissues prone to delamination. Microwave treatment may compromise tissue integrity, additionally, the effectiveness of chemical reagents can be sensitive to variations in temperature, pH, and concentration. This study aims to optimize antibody stripping strategies specifically for use in Opal mIHC protocols, addressing limitations of current methods which particularly for tissues prone to delamination.

Results

Evaluation of microwave oven-assisted antibody removal (MO-AR), chemical reagent-based antibody removal (CR-AR), and hybridization oven-based stripping at 50 °C (HO-AR-50) and 98 °C (HO-AR-98) revealed that MO-AR and HO-AR-98 most effectively removed primary and secondary antibodies. In five-color mIHC on mouse kidney sections, both methods yielded strong target-specific signals. However, in brain tissue sections prone to delamination, HO-AR-98 better preserved tissue integrity compared to MO-AR and supported effective multi-target staining. These findings establish a novel thermochemical stripping method compatible with TSA-based Opal mIHC, enhancing its utility in research and clinical diagnostics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13104-025-07301-4.

Keywords: Multiplexed immunohistochemistry, Antibody stripping, Tyramide signal amplification, Hybridization oven-based antibody removing (HO-AR)

Introduction

Multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC), a technique that enables the simultaneous detection of multiple proteins on a single tissue section, has emerged as a powerful tool in both basic research and clinicopathological diagnosis [1]. Conventional mIHC or multiplexed immunofluorescence (mIF) methodologies typically allow staining of only a limited number of markers, commonly fewer than three, and require that all primary antibodies used in the detection process originate from different species [2]. Tyramide signal amplification (TSA) based mIHC has gained widespread adoption as a practical tool for investigating spatial relationships within tissue microenvironment, enabling the simultaneous measurement of 6–8 target proteins on a single tissue section without cross-reactivity [3–5]. This technique involves sequential cycles of antibody labeling and stripping [6]. However, a significant challenge associated with this ‘stain-erase’ protocol is the generation of non-specific signals due to cross-reactivity [7, 8].

To achieve effective antibody stripping, immunoglobulins can be denatured by heat treatment under optimized conditions of pH, temperature, and solution composition [9]. However, this may compromise tissue integrity, particularly when handling delicate biopsies mounted on poly-lysine-coated slides [10]. Besides, denaturing surfactants like SDS [11, 12], proteases [13], and combinations of strong reducing agents and detergents [14] have been explored to facilitate the removal of thermally denatured proteins. Nevertheless, the efficacy of these methods varies depending on the specific case, and their impact on tissue integrity and antigenicity must be carefully evaluated.

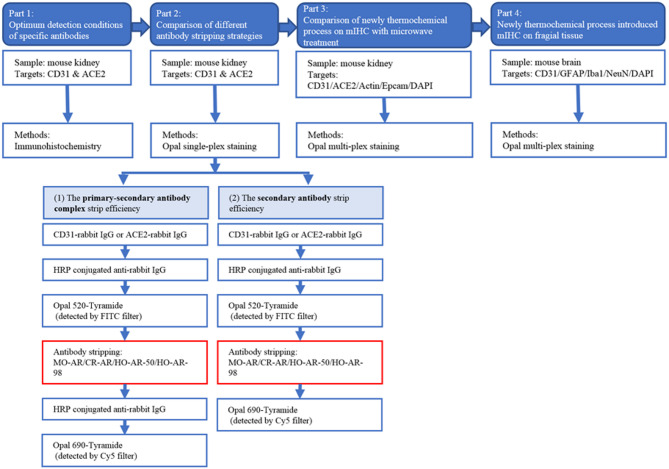

In the present study, we systematically evaluated four antibody stripping strategies for manual mIHC detection when employing the TSA technique. These strategies included microwave oven-assisted antibody removal (MO-AR), which served as the control for stripping quality; chemical reagent-based antibody removal (CR-AR), representing a chemical denaturation approach; and hybridization oven-based antibody removal conducted at 50 °C (HO-AR-50) and 98 °C (HO-AR-98) which involved modifications to the heating process and temperature relative to MO-AR. The workflow of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. After carefully evaluating, we successfully established an optimized thermochemical process using a hybridization oven for the removal of antibody complexes between staining cycles. The newly established antibody stripping protocol will facilitate the application of TSA-based mIHC technology for the detection in fragile tissues.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the study

Materials and methods

Sample

Six- to eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12:12 h light–dark cycle. All procedures followed guidelines approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital (LA2022033). Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation performed by trained personnel. Post-mortem, kidney and brain tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm using a Leica RM2235 microtome for subsequent staining.

Chromogenic immunohistochemistry (IHC)

In this study, we selected distinct staining targets for renal and brain tissues to visualize various cell types, including ACE2, Actin, CD31, Epcam, GFAP, Iba1, and NeuN. These cell populations are consistently present within the respective tissues, thereby rendering them appropriate candidates for both the establishment and assessment of the methodologies employed in this study.

Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H₂O₂ in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed using a microwave in citrate (pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA (pH 9.0) buffer, based on antibody specifications. The sections were subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against ACE2 (ab180252, Abcam), Actin (ab68167, Abcam), CD31 (77688 S, CST), Epcam (ab213500, Abcam), GFAP (ab68428, Abcam), Iba1 (17198T, CST) and NeuN (24307T, CST) at 37 °C for 2 h (see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed information). A negative control was conducted by substituting PBS for primary antibody incubation. Sections were incubated with HRP-polymer goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (PV-6001, ZSBIO) for 30 min at RT. Positive signals were visualized using a DAB Detection Kit (K3468, Dako).

Opal single-plex assay

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated according to the Opal 6-Plex Manual Detection Kit protocol (NEL811001KT, Akoya Bioscience). Then, antigen retrieval was performed consistently with the protocol used for IHC assays. Slides were blocked with blocking/antibody diluent for 10 min at RT, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (anti-ACE2, anti-Actin, anti-CD31, anti-Epcam, anti-GFAP, anti-Iba1, anti-NeuN) for 40 min at 37 °C. After washing with 1X TBST, the slides were incubated with an HRP-polymer goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody for 10 min at RT, then with Opal fluorophores (Opal 520, Opal 570, Opal 620, and Opal 690, 1:100 dilution; see Supplementary Table 2) for 10 min at RT. Sections were counterstained with DAPI and finally mounted with an antifade mounting medium (H-1400, VECTASHIELD).

Antibody stripping

In this study, we compared four different antibody stripping methods. For each stripping method, two consecutive sections were prepared as a group. All sections were initially subjected to the Opal single-plex assay; CD31 or ACE2 was labeled using Opal 520 followed by primary and secondary antibody incubation, after which the antibody removal step was performed. For MO-AR, slides were treated in antigen retrieval buffer for 15 min at 50% power in an 800 W household microwave oven. In the case of CR-AR, commercial reagents (WELLGENE, China) were applied to the sections and incubated for 30 min at RT. Hybridization oven-based antibody removal (HO-AR) was conducted at two different temperatures: HO-AR-50 and HO-AR-98. Briefly, sections were placed on a heating plate and incubated with antigen retrieval buffer for 30 min at either 50–98 °C. To prevent tissue from drying out, the heated retrieval buffer was replenished every 5 min. After the stripping process, the effectiveness of the secondary stripping was confirmed by incubating the sections with Opal 690 fluorophore for 10 min, which was visualized using a Cy5 filter. Additionally, to evaluate the stripping efficiency of the primary-secondary antibody complex, the corresponding section was further incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and Opal 690 (see Table 1 for detailed information). Six sections for each antibody elution method were used to evaluate the stripping efficiency, and imageJ software was utilized to analyze the intensity profile of fluorescence signals in the FITC and Cy5 channels.

Table 1.

Details of antibody stripping strategies

| Approach | Section | Singleplex Opal | Antibody stripping | Protocol | Secondary antibody | Additional Opal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO-AR | #1 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Microwave oven, 15 min, 95℃ |

Yes | Opal 690 |

| #2 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Microwave oven, 15 min, 95℃ |

No | Opal 690 | |

| CR-AR | #1 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Chemical reagent, 30 min, RT |

Yes | Opal 690 |

| #2 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Chemical reagent, 30 min, RT |

No | Opal 690 | |

| HO-AR-50 | #1 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Hybridization oven, 30 min, 50℃ |

Yes | Opal 690 |

| #2 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Hybridization oven, 30 min, 50℃ |

No | Opal 690 | |

| HO-AR-98 | #1 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Hybridization oven, 30 min, 98℃ |

Yes | Opal 690 |

| #2 | Opal 520 | Yes |

Hybridization oven, 30 min, 98℃ |

No | Opal 690 |

Opal multiplex immunohistochemistry (Opal mIHC) assay

According to the manufacturer’s instructions [15, 16], sections were dewaxed and subsequently dehydrated. Each target protein was detected sequentially using the Opal single-plex method. Antigen retrieval was performed with citrate or Tris-EDTA buffer, followed by incubation with the CD31 primary antibody at 37 °C for 40 min. After TBST washing, detection was carried out using the Opal Polymer HRP Ms + Rb system (NEL811001KT, Akoya Biosciences) for 10 min at RT, and signals were visualized with Opal 520 (1:100) for 10 min. After each staining cycle, the sections were washed in TBST, and the previously labeled antibodies were stripped to prepare for the next target protein detection. Details of the staining targets and corresponding Opal fluorophores are provided in Table 2. This process was repeated until all targets were detected. Sections were finally counterstained with DAPI and mounted with antifade medium. To evaluate antigenicity across methods, at least ten paired regions of interest (ROIs) were imaged and analyzed for each marker.

Table 2.

Details of mIHC assay

| mIHC Staining |

Target | Opal-TSA | Stripping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Brain | |||

| 1st Cycle | CD31 | CD31 | Opal 520 | MO-AR or HO-AR-98 |

| 2nd Cycle | Actin | NeuN | Opal 570 | MO-AR or HO-AR-98 |

| 3rd Cycle | Epcam | Iba1 | Opal 690 | MO-AR or HO-AR-98 |

| 4th Cycle | ACE2 | GFAP | Opal 620 | MO-AR or HO-AR-98 |

Tissue integrity assessment

According to previous studies, several methods for stripping antibodies may affect tissue integrity or slide adhesion [7]. To compare tissue integrity under MO-AR and HO-AR-98 treatments, three consecutive mouse brain sections from 12 samples were utilized. For each sample, the first section underwent MO-AR treatment, and the last was subjected to four cycles of HO-AR-98. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on the middle section. Fluorescence images were converted to grayscale in ImageJ, and thresholds were adjusted to define total tissue area based on H&E staining. Missing regions in MO-AR and HO-AR-98 treated sections were similarly identified, and the ratio of missing area to total tissue area was calculated as a quantitative measure of tissue integrity. This approach enabled a comparative evaluation of tissue morphology following different stripping protocols.

Image acquisition and analysis

Multispectral images were acquired using the Vectra Polaris system (Akoya Bioscience) with autoexposure settings to detect positive signals [17, 18]. InForm 2.6 software (Akoya Biosciences) was used to unmix images using a custom spectral library and perform quantitative analysis, including cell segmentation and signal quantification. Signal thresholds were set for each target to ensure accuracy. Stripping efficiency was assessed by measuring mean fluorescence intensity in the Cy5 channel. Positive cells were identified and counted based on consistent thresholds. Uniform imaging parameters in the Cy5 channel were applied across methods to ensure standardized comparison.

Data analysis

Paired t-tests, independent t-test and Pearson correlation coefficients were utilized to compare differences between groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 26. The statistical graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 6 software. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of different antibody stripping strategies

Before evaluating the efficacy of the different antibody stripping methods, we first performed chromogenic IHC and fluorescence single-plex staining for CD31 and ACE2 to optimize the staining conditions and confirm the suitability and specificity of the antibodies used (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Two consecutive mouse kidney sections were used to evaluate the stripping efficiency of the secondary antibody and primary-secondary antibody complex, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). If the secondary antibody is completely stripped while the primary antibody remains bound to the antigen epitope, reapplication of the same secondary antibody leads to binding and subsequent Opal 690 signal detection via the Cy5 channel. Similarly, if the primary-secondary antibody complex remains bound to the target protein, additional incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG can bind the primary antibody and activate Opal 690. Positive signals detected in both channels indicate incomplete stripping. Thus, the ability to relabel the first target with a second Opal-TSA signal reflects the effectiveness of the stripping method.

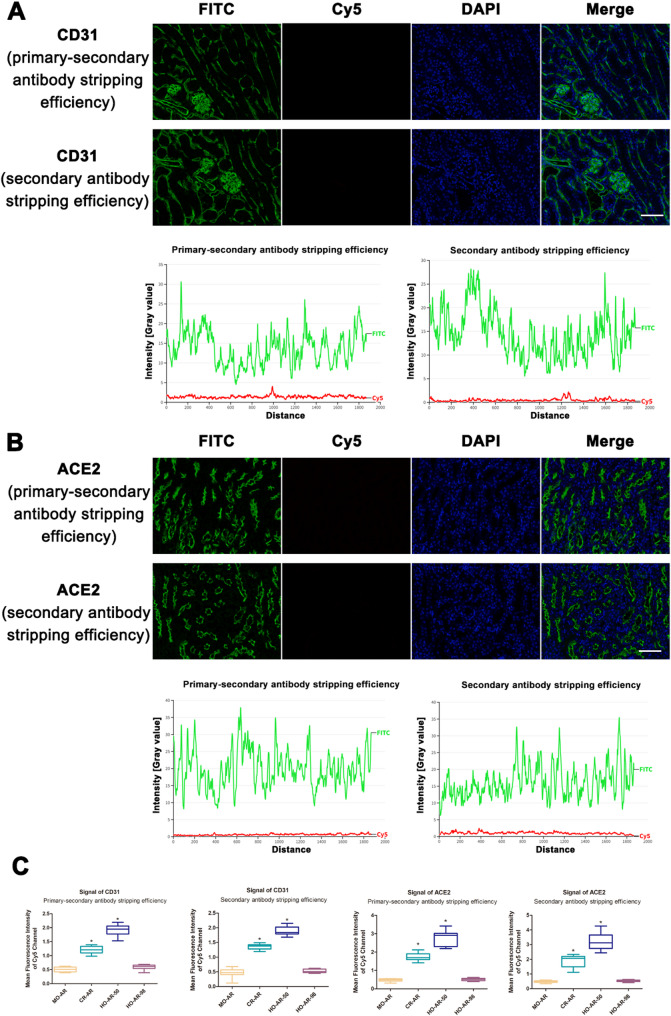

First, we examined the efficacy of antibody removal using MO-AR treatment. As shown in Fig. 2, no positive signal was detected using Opal 690 during CD31 and ACE2 staining. The signal intensity in the Cy5 channel was very low and there was no colocalization with the FITC channel. These findings confirm that MO-AR effectively eliminates both primary and secondary antibodies, ensuring there is no residual binding that could interfere with subsequent staining rounds.

Fig. 2.

Antibody stripping effect of MO-AR on CD31 and ACE2 staining. A-B. Experimental validation of the antibody stripping effect of MO-AR on CD31 and ACE2 staining. Positive signals were detected using FITC for Opal 520 and Cy5 for Opal 690. Scale bar: 100 μm. The mean intensity profile (gray value) of the FITC and Cy5 channel was calculated and displayed as a histogram

For CR-AR, positive signals were detected not only in the Opal 520 channel but also in the Cy5 filter channel. The intensity profiles showed that the signals in the Cy5 channel exhibited consistent expression changes with those in the FITC channel (Figs. 3). These results indicate that the primary and secondary antibodies were not completely removed by the commercial stripping buffer.

Fig. 3.

Antibody stripping effect of CR-AR on CD31 and ACE2 staining. A-B. Experimental validation of the antibody stripping effect of CR-AR on CD31 and ACE2 staining. Positive signals were detected using FITC for Opal 520 and Cy5 for Opal 690. Scale bar: 100 μm. The mean intensity profile (gray value) of the FITC and Cy5 channel was calculated and displayed as a histogram

To explore alternative and milder methods for antibody stripping during TSA-based mIHC staining, we utilized a hybridization oven to achieve the necessary temperature for antibody removal without causing the buffer to boil during the process. This approach was designed to maximize protection of tissue integrity. We observed that a temperature of 50 °C was insufficient for achieving complete antibody elution (Fig. 4). When the temperature was increased to 98 °C, both the primary and secondary antibodies were stripped from their epitopes (Fig. 5). Additionally, we analyzed the Cy5 channel signal intensity across stripping methods. Compared to MO-AR, CR-AR and HO-AR-50 showed significantly higher Cy5 signal intensity in CD31 and ACE2 staining (P < 0.001), while HO-AR-98 showed comparable intensity to MO-AR (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that HO-AR-98 method is an effective thermochemical process for complete antibody stripping.

Fig. 4.

Antibody stripping effect of HO-AR-50 on CD31 and ACE2 staining. A-B. Evaluation of the antibody stripping effect of HO-AR-50 on CD31 and ACE2 staining. The procedures for assessing primary-secondary antibody stripping efficiency and secondary antibody stripping efficiency follow a methodology similar to that of previously mentioned protocols. Scale bar: 100 μm

Fig. 5.

Antibody stripping effect of HO-AR-98 on CD31 and ACE2 staining. A-B. Evaluation of the antibody stripping effect of HO-AR-98 on CD31 and ACE2 staining. The procedures for assessing antibody stripping efficiency was similar to that of previously mentioned protocols. C. Mean fluorescence intensity of Cy5 channel. * P < 0.001 compared to MO-AR

Establishment of novel thermochemical stripping process for mIHC

Prior to performing multiplex staining, we tested the detection conditions for each antibody and verified the effectiveness of the antibody elution (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

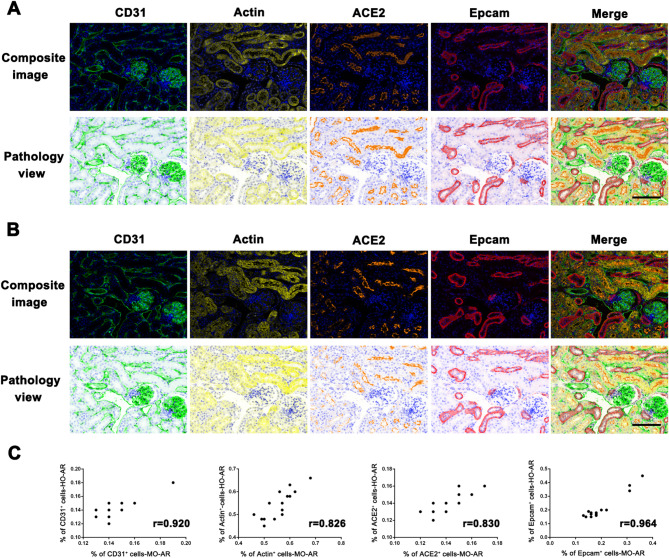

Next, we compared Opal mIHC staining induced by MO-AR and HO-AR-98 using two adjacent kidney sections (details are provided in Table 2). Figure 6A and B present representative composite images and pathology views of CD31, Actin, Epcam, ACE2, and DAPI staining. Both MO-AR- and HO-AR-98-based mIHC exhibited specific positive fluorescent signals for each target without cross-reactivity. To assess whether HO-AR-98 affects subsequent staining, we analyzed the positive rate of each target. The pearson correlation coefficients for CD31, Actin, ACE2, and Epcam were 0.920, 0.826, 0.830, and 0.964, respectively (all P < 0.001; Fig. 6C), indicating no significant difference in antigen detection efficacy between the stripping methods.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of mIHC staining using MO-AR and HO-AR-98 for antibody stripping. Composite images and pathological views of each target from mIHC following antibody stripping with MO-AR (A) and HO-AR-98 (B). The targets include CD31, Actin, ACE2, and Epcam. C. Quantitative analysis of the percentage of CD31+, Actin+, ACE2+ and Epcam+ cells determined by mIHC induced by MO-AR compared to HO-AR-98 in adjacent tissue sections

Verification the stripping effect of thermochemical method in brain slices

To establish a feasible Opal mIHC protocol for tissues prone to detachment, we used mouse brain samples to validate the multitarget panel and assess tissue integrity during antibody stripping with MO-AR or HO-AR-98. Compared to H&E-stained sections, slides treated with MO-AR exhibited more missed tissue fields than those treated with HO-AR-98 (Fig. 7A). To quantify tissue integrity, ImageJ software was used to measure the total tissue area and the missed tissue area (data was shown in Supplementary Table 3). The ratio of missed area to total area was significantly lower in HO-AR-98-treated sections compared to MO-AR-treated sections (Fig. 7B, P < 0.001), indicating that HO-AR-98 significantly improved tissue integrity over microwave treatment.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of tissue integrity in mIHC using two antibody stripping strategies. A. Comparison with HE staining sections, areas where tissue was missed are marked by red lines. For tissue area recognition, imageJ software was used to analyze and label these regions in red. B. Quantitative analysis showing the percentage of missed tissue area under MO-AR or HO-AR-98 treatment. ***P < 0.001. C. Whole slide scan images of brain sections subjected to mIHC using MO-AR and HO-AR-98. A representative high-resolution field from HO-AR-98-induced mIHC is provided. Scale bar: 100 μm

Furthermore, we performed a 5-plex mIHC panel targeting CD31, GFAP, Iba1, NeuN, and DAPI on brain sections, followed by an antibody stripping efficiency assay (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The multiplex fluorescent images demonstrated excellent specific positive signals with no cross-reactivity (Fig. 7C). Taken together, our data successfully demonstrate that the optimized HO-AR-98 stripping strategy is stable and effective for multitarget detection in softer samples, significantly improving tissue integrity. Thus, it represents a robust approach for advanced immunohistochemical analyses.

Discussion

Antibody stripping is important for TSA-based mIHC

Over the past years, multitarget immunohistochemical assays have garnered increasing attention for their utility in both diagnosis and research applications. These assays enable the visualization of complex data hidden within the tumor microenvironment (TME) and facilitate the analysis of spatial relationships between cell subsets in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue Sect. [6]. One of the most widely adopted multiplex immunohistochemical approaches is the TSA-based mIHC which can detect multiple protein targets through sequential staining rounds. However, the efficiency and completeness of antibody stripping between staining rounds significantly impact the specificity and balance of the fluorescent signals. Incomplete removal of antibodies can lead to cross-reactivity and compromised results. In the present study, we aimed to address these challenges by developing an optimized antibody stripping strategy suitable for both conventional tissues and specialized tissue slices that are prone to detachment. After a thorough evaluation, HO-AR-98 demonstrated significant advantages, particularly in maintaining tissue integrity and ensuring thorough antibody removal. This strategy was successfully applied to multiplex immunohistochemical staining, providing reliable and reproducible results. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of the four antibody stripping methods discussed herein is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

The advantages and disadvantages of the four antibody stripping methods

| Methods* | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| MO-AR | Stable elution efficacy | Morphological damage and tissue loss in fragile tissues |

| CR-AR | Applicable to a wide range of tissue types |

Inconsistent elution efficacy; Optimization of time and temperature parameters |

| HO-AR-50 | Applicable to a wide range of tissue types | Inconsistent Elution efficacy |

| HO-AR-98 |

Applicable to a wide range of tissue types; Stable elution efficacy; Preservation of tissue integrity |

Relatively lengthy processing time |

* MO-AR: microwave oven-assisted antibody removal; CR-AR: chemical reagent-based antibody removal; HO-AR-50: hybridization oven-based antibody removal conducted at 50℃; HO-AR-98: hybridization oven-based antibody removal conducted at 98℃

Current applications of antibody stripping methods

Antibody stripping, a crucial step in mIHC staining, has been extensively explored and studied. Heating-based IgG denaturation of Fab and Fc fragments is largely determined by temperature and pH [9]. Microwave treatment between staining cycles has become a standard stripping method, serving as a heat-based process for removing primary/secondary antibody complexes, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations [19]. However, microwave treatment may cause delicate tissues to detach from poly-lysine-coated slides, such as brain, bone, cartilage, and skin [20, 21], as observed in our study on mouse brain. Wenjun Zhang. et al. used Ventana’s BenchMark ULTRA auto slide stainer to perform mIHC using indirect Fluor-IgG. Heat pads placed under the slides were employed to heat the samples for 8 min, facilitating the stripping of antibodies from the prior round of antigen detection [22]. For TSA-based mIHC in our study, the hybridization oven’s heating plate replaced the microwave oven or proprietary heat pad to provide necessary temperature for antibody stripping, as Fab fragments are more sensitive to temperature [9]. We also observed that higher temperature improved stripping effectiveness. Other factors, such as low molecular weight surfactants (e.g., SDS) and the reducing agent 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), has been reported to effectively remove primary and secondary antibodies from FFPE tonsil tissue and BMCB sections. These methods demonstrate high efficiency with minimal impact on tissue antigenicity or integrity [23]. The ineffectiveness of the commercial solution used in this study may be attributed to suboptimal working concentrations or temperatures, which fail to adequately deactivate the antibodies. In fact, several factors must be carefully considered during antibody stripping, including heat, buffer properties, composition, and antibody affinity [11, 24, 25]. Moreover, it should be noted that each antigen requires separate testing due to variation in sensitivity to the stripping process. Several reported methods for physically or chemically removing antibodies from FFPE sections focus not only on the efficiency of antibody elution but also on preserving antigenicity and tissue integrity [23]. The use of a stripping buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, instead of heating, has been shown to markedly improve tissue integrity without affecting signal intensity or exposure times. However, the toxicity of β-mercaptoethanol limits its widespread application [12]. In this study, the HO-AR-98 process improved the protection of tissue morphology while maintaining the detection rate of specific proteins. Consequently, this newly developed thermochemical stripping strategy was demonstrated to be a “mild” process that performs well in cyclic antibody labeling and stripping.

In conclusion, this study compared four antibody stripping methods for TSA-based Opal mIHC to develop an approach ensuring complete antibody removal and tissue integrity. We established an optimized strategy that thoroughly removes antibodies and significantly enhances tissue preservation, expanding mIHC applicability in research and clinical diagnostics.

Limitation

Limitation in sample quantity and variety: In this study, we validated the optimized approach using only a limited number of mouse kidney and brain tissue sections. In future work, the number and variety of tested samples should be further expanded to better enhance the reliability and generalizability of the technical system.

Limitation in target detection: In this study, we evaluated the optimized technical system using a total of seven protein targets in kidney and brain tissues. However, the reliability of the method has not yet been validated across a broader range of target proteins. Notably, prior to implementing the mIHC panel, it is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of each target antigen individually. This step ensures that each antibody performs optimally under the specified stripping and staining conditions, thereby maintaining the specificity and reliability of the results.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81400440, No.82072870). The authors would like to thank Jingshu Hong for tissue preparation.

Abbreviations

- mIHC

Multiplexed Immunohistochemistry

- mIF

Multiplexed Immunofluorescence

- TSA

Tyramide Signal Amplification

- MWT

Microwave Treatment

- MO-AR

Microwave Oven-Based Antibody Removal

- CR-AR

Chemical Reagent-Treated Antibody Removal

- HO-AR-50

Hybridization Oven-Based Antibody Removal at 50 °C

- HO-AR-98

Hybridization Oven-Based Antibody Removal at 98 °C

Author contributions

Xiaotong Yu and Chen Huang designed this research; Yan Song and Li Chen coordinated the study and collected data; Xiaotong Yu analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Jianling Yang, Chen Huang and Lixiang Xue approved the final version to be published.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81400440, No.82072870).

Data availability

Data and materials are provided by tables and figures within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In this study, animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animal Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital (approval number: LA2022033).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianling Yang, Email: jianlingyang@bjmu.edu.cn.

Chen Huang, Email: candyhuang719@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Taube JM, Akturk G, Angelo M, Engle EL, Gnjatic S, Greenbaum S et al. The society for immunotherapy of Cancer statement on best practices for multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF) staining and validation. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Harms PW, Frankel TL, Moutafi M, Rao A, Rimm DL, Taube JM, et al. Multiplex immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence: A practical update for pathologists. Mod Pathol. 2023;36(7):100197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyt CC. Multiplex Immunofluorescence and multispectral imaging: forming the basis of a clinical test platform for Immuno-Oncology. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:674747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovisa S, LeBleu VS, Tampe B, Sugimoto H, Vadnagara K, Carstens JL, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat Med. 2015;21(9):998–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJM, Robert L, et al. PD-1 Blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515(7528):568–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stack EC, Wang C, Roman KA, Hoyt CC. Multiplexed immunohistochemistry, imaging, and quantitation: a review, with an assessment of tyramide signal amplification, multispectral imaging and multiplex analysis. Methods. 2014;70(1):46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrenberg AJ, Morales DO, Piergies AMH, Li SH, Tejedor JS, Mladinov M, et al. A manual multiplex Immunofluorescence method for investigating neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;339:108708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim JCT, Yeong JPS, Lim CJ, Ong CCH, Wong SC, Chew VSP, et al. An automated staining protocol for seven-colour Immunofluorescence of human tissue sections for diagnostic and prognostic use. Pathology. 2018;50(3):333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeer AW, Norde W. The thermal stability of Immunoglobulin: unfolding and aggregation of a multi-domain protein. Biophys J. 2000;78(1):394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirici D, Mogoanta L, Kumar-Singh S, Pirici I, Margaritescu C, Simionescu C, et al. Antibody elution method for multiple immunohistochemistry on primary antibodies Raised in the same species and of the same subtype. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57(6):567–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gendusa R, Scalia CR, Buscone S, Cattoretti G. Elution of High-affinity (> 10(-9) K-D) antibodies from tissue sections: clues to the molecular mechanism and use in sequential immunostaining. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62(7):519–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willemsen M, Krebbers G, Bekkenk MW, Teunissen MBM, Luiten RM. Improvement of opal multiplex Immunofluorescence workflow for human tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 2021;69(5):339–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JR, Fallahi-Sichani M, Sorger PK. Highly multiplexed imaging of single cells using a high-throughput Cyclic Immunofluorescence method. Nat Commun. 2015;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kim M, Soontornniyomkij V, Ji BH, Zhou XJ. System-Wide immunohistochemical analysis of protein Co-Localization. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gide TN, Silva IP, Quek C, Ahmed T, Menzies AM, Carlino MS, et al. Close proximity of immune and tumor cells underlies response to anti-PD-1 based therapies in metastatic melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1659093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parra ER, Uraoka N, Jiang M, Cook P, Gibbons D, Forget MA, et al. Validation of multiplex Immunofluorescence panels using multispectral microscopy for immune-profiling of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded human tumor tissues. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiore C, Bailey D, Conlon N, Wu X, Martin N, Fiorentino M, et al. Utility of multispectral imaging in automated quantitative scoring of immunohistochemistry. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(6):496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abel EJ, Bauman TM, Weiker M, Shi F, Downs TM, Jarrard DF, et al. Analysis and validation of tissue biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma using automated high-throughput evaluation of protein expression. Hum Pathol. 2014;45(5):1092–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sommaggio R, Cappuzzello E, Dalla Pieta A, Tosi A, Palmerini P, Carpanese D et al. Adoptive cell therapy of triple negative breast cancer with redirected cytokine-induced killer cells. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cuevas EC, Bateman AC, Wilkins BS, Johnson PA, Williams JH, Lee AH, et al. Microwave antigen retrieval in immunocytochemistry: a study of 80 antibodies. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47(5):448–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi SR, Key ME, Kalra KL. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39(6):741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W, Hubbard A, Jones T, Racolta A, Bhaumik S, Cummins N, et al. Fully automated 5-plex fluorescent immunohistochemistry with tyramide signal amplification and same species antibodies. Lab Invest. 2017;97(7):873–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolognesi MM, Manzoni M, Scalia CR, Zannella S, Bosisio FM, Faretta M, et al. Multiplex staining by sequential immunostaining and antibody removal on routine tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 2017;65(8):431–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tornehave D, Hougaard DM, Larsson L. Microwaving for double indirect Immunofluorescence with primary antibodies from the same species and for staining of mouse tissues with mouse monoclonal antibodies. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;113(1):19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tramu G, Pillez A, Leonardelli J. Efficient method of antibody elution for successive or simultaneous localization of 2 antigens by immunocytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochemistry. 1978;26(4):322–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are provided by tables and figures within the manuscript.