Abstract

Background

Sustainability has become an important consideration in the twenty-first century, with physical education contributing to students' cognitive, affective, and psychomotor development. Physical education teachers can promote sustainable lifestyles through their teaching practices. This study examines the relationship between intrapersonal and interpersonal mindfulness and sustainability competencies (social, economic, and environmental dimensions), along with the moderating role of demographic variables.

Methods

Data were collected from 852 physical education teachers in Turkey. Structural equation modeling and moderator analysis were used to analyze the relationships between mindfulness and sustainability competencies, and the moderating effects of gender, education level, and school level.

Results

Intrapersonal mindfulness showed a stronger association with sustainability competencies than interpersonal mindfulness. Demographic variables moderated this relationship, with female teachers, high school teachers, and those with postgraduate education exhibiting stronger links between mindfulness and sustainability competencies.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that mindfulness can support teachers in promoting sustainability. Professional development programs should consider integrating mindfulness training. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability in education and its implications for the Sustainable Development Goals.

Keywords: Physical education teachers, Intrapersonal mindfulness, Interpersonal mindfulness, Sustainability competencies, Demographic factors

Introduction

Sustainability, which is considered one of the most important global challenges of the twenty-first century, is a key issue. In education, as in other areas, it is crucial to consider the environmental, social and economic dimensions. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1] emphasize the crucial role of education systems as catalysts for sustainable development [2]. Education serves as a mechanism for improving environmental literacy and facilitating societal change by providing people with the essential knowledge and skills to understand sustainability [3]. In this regard, educators'competencies in sustainability are extremely important, especially in integrating sustainable practices into educational methodology and communicating this understanding to students [4]. Physical education (PE) provides a unique opportunity to enrich cognitive approaches by incorporating the physical dimension and learning through experiential methods, as well as incorporating emotional and sensory aspects [5]. Although it is claimed that physical education has a limited role in sustainable education [6, 7], PE teachers can significantly improve students'environmental literacy, social responsibility and economic sustainability through physical activity and sport [7].

The SDGs, established by the United Nations in 2015, aim to address global challenges by 2030. These goals include health and well-being, gender equality, decent work and economic growth, reduced inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, responsible consumption and production, climate action, and peace, justice and strong institutions [1]. Physical activity and sport have been identified as important contributors to several of these SDGs [8]. Addressing sustainable development issues in physical education has been shown to promote students'critical and systematic thinking, which is essential for achieving the SDGs [6]. Physical education provides a learning environment that encourages students to connect with nature, understand environmental issues and cultivate a sustainable lifestyle [9]. This requires that physical education teachers not only teach physical skills, but also model sustainable behaviors and advocate for sustainable lifestyles. However, the effectiveness of PE teachers in this role depends on their sustainability competencies and individual characteristics, such as their level of mindfulness. In this context, it is important to conceptually link mindfulness and sustainability competence, as both are essential for teachers to effectively integrate sustainability into their teaching practices. Mindfulness is associated with characteristics that facilitate the implementation of education for sustainable development [10].

Mindfulness, defined as the ability to fully grasp the present moment without judgment and with unwavering concentration [11], is deeply rooted in the psychological principles of attention regulation and emotional awareness. In education, mindfulness is consistent with theories of emotion regulation [12], which state that managing emotional responses improves decision-making and reduces cognitive overload. Studies show that mindfulness practices improve teachers'ability to manage stress and regulate emotions [13], which promotes resilience and cognitive flexibility — key components of positive psychology [14]. This empowerment enables educators to adopt sustainable practices by cultivating intrinsic motivation [15] and adaptive coping strategies that are critical for thriving in dynamic classrooms. In the context of PE, mindfulness may support teachers in modeling and promoting sustainable behaviors, as it enhances their awareness and intentionality in both personal and professional domains.

The link between mindfulness and sustainability literacy is particularly important for physical education teachers who use physical activity as a medium to instill environmentally friendly attitudes and social responsibility in students. This is consistent with social learning theory [16], in which teachers model sustainable behaviors to enhance students'self-efficacy in adopting environmentally conscious habits. Physical activity as a skill to promote sustainability taps into embodied cognition [17], where physical experiences deepen students'connection to environmental stewardship. Physical education teachers, as agents of change, embody transformational leadership [18] by using mindfulness to enhance their emotional intelligence [19] and promote empathy — a psychological driver of prosocial and sustainable behavior.

Demographic variables such as gender, educational background and level of teaching experience add nuance to this relationship. For example, gender socialization [20] explains why female teachers often show a higher commitment to mindfulness and sustainability, reflecting societal expectations of a caring role. Similarly, teachers with postgraduate qualifications demonstrate advanced metacognitive skills [21] that enable them to translate mindfulness into actionable sustainability practices. These findings are consistent with cognitive development theory [22] that higher education promotes abstract thinking and systemic reasoning —which is essential for tackling complex sustainability challenges.

Therefore, in the context of this study, demographic variables are considered as potential moderators that may influence the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competence among PE teachers. By integrating mindfulness into their practice, PE teachers improve their psychological wellbeing and professional effectiveness, reducing the risk of burnout [23], while modeling sustainable self-care for students. Future research should explore the neuropsychological mechanisms linking mindfulness to sustainable behavior, such as how activation of the prefrontal cortex during mindfulness practice improves executive functioning [24], supporting sustainable decision-making.

The strategic application of mindfulness has shown remarkable improvements in teachers'ability to manage stress and regulate emotions, paving the way for more effective decision-making in educational processes [13]. This transformative practice catalyzes the adoption of sustainable practices by equipping educators with the ability to be innovative, adaptable, and flexible in dynamic classrooms [25]. Educators who embody high levels of mindfulness can seamlessly integrate sustainability topics into lessons and extracurricular activities, significantly increasing students'awareness and understanding of these critical issues [9]. The link between mindfulness and sustainability literacy is particularly important for PE teachers as they occupy a central position in engaging and sensitizing students to environmental, social and economic sustainability through physical activity [6, 7].

Physical activity promotes sustainable behaviors in students by increasing their awareness and sensitivity to the natural environment [26]. Within this framework, PE teachers are entrusted with advancing the SDGs and embodying a force for change. Mindfulness gives PE teachers the opportunity to hone their professional skills while promoting students'sustainability competencies. Through mindfulness practices, teachers improve their responsiveness and efficiency in classroom interactions and encourage students to be environmentally and socially responsible [27]. In addition, mindfulness strengthens teachers'resilience, reduces the risk of professional burnout, and improves the overall quality of teaching [13].

Despite the undeniable potential, the extent to which demographic variables influence the dynamic interplay between mindfulness and sustainability literacy remains a vast, unexplored field. Factors such as gender, educational background and teacher level could significantly influence the sustainability competencies of PE teachers. Research has shown that female teachers often have higher levels of mindfulness, which in turn has a very positive impact on their sustainability skills [7]. Similarly, educators with postgraduate training have a more sophisticated ability to transform mindfulness practices into enhanced sustainability competencies [28]. Recognizing the crucial moderating role of demographic factors is critical to developing tailored and effective professional development programs for physical education teachers. Creating a supportive school environment and exemplary leadership can stimulate and sustain teachers'motivation for sustainable practice, while strategically designed professional development programs can accelerate the growth of these important competencies [4].

Nevertheless, there is a significant gap in scientific research on how these influential factors interact in the intricate relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competencies in PE teachers. In summary, this study aims to conceptually and empirically link mindfulness, sustainability competence, and demographic variables within the context of physical education. By doing so, it seeks to provide a clearer justification for examining these variables together and to address the need for a more integrated approach in the literature.

This study examines the relationship between physical education teachers'mindfulness and their sustainability competencies, with particular focus on how demographic variables (gender, school level, and educational background) may influence this relationship. The research seeks to contribute to existing knowledge about the connections between mindfulness and sustainability in educational settings. From a theoretical perspective, the study aims to enhance understanding of how mindfulness relates to sustainability competencies among educators. Practically, the findings may inform teacher training programs by highlighting the potential benefits of considering demographic factors when developing mindfulness-based approaches to sustainability education. The study provides physical education teachers with evidence-based insights that could help them develop effective strategies for fostering sustainability competencies in their students.

This study begins with a conceptual framework and a theoretical background. It addresses the concepts of mindfulness and sustainability literacy and uncovers their interrelationship in education. It then presents a research model with hypotheses that explore the dynamics between mindfulness and sustainability literacy, taking into account the moderating role of demographic variables. The methodology section describes the research design, presenting the composition of participants, ways of collecting data, and methods of analysis. The" Results"section reveals the findings, while the" Discussion"section provides an in-depth interpretation of these findings, placed in the context of the existing literature. The"Conclusion"section summarizes the findings, highlighting their significance and providing recommendations for future research.

Conceptual framework and theoretical background

Goals of sustainable development

Sustainable development is aptly described as the vital safeguarding of abundant resources and dynamic opportunities for the present generation while ensuring the sustainability and prosperity of future generations [29]. Although a clear, universally accepted definition of sustainability is difficult to find, it has been described as a complex, multi-layered paradigm that closely interweaves the social, economic and environmental threads of our global fabric [30]. The internationally recognized SDGs, consisting of 17 essential universal headline targets combined with 169 complex sub-targets, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 with a visionary commitment to create a truly sustainable future on a large global scale by 2030 [1, 31]. These bold goals embody a profound, transformative and multidimensional endeavor that aims to eradicate poverty, reduce inequalities, mitigate the urgent effects of climate change and promote the emergence of harmonious and peaceful societies. The SDGs represent a comprehensive, far-reaching framework that not only advocates for the protection of the environment, but also sounds a resounding call for social justice, robust economic growth and a substantial improvement in the quality of life of people around the world [32].

Achieving the ambitious and transformative SDGs depends on the united and decisive action of governments working together with the dynamic energy of the private sector, the unwavering commitment of civil society and the proactive engagement of individuals. By cultivating and driving global collaboration, these goals serve as a catalyst for solutions that advance sustainable development with vigor and purpose [33]. Consider, for example, the bold and effective strategies to combat climate change: utilizing renewable energy sources and improving energy efficiency promise not only to protect our environment, but also to deliver significant economic benefits [34]. Furthermore, achieving the SDGs requires the strategic empowerment of communities in conjunction with the formulation of equitable and inclusive tactics that are refined at the grassroots level. Central to this paradigm are the pillars of gender equality and women's empowerment, which are recognized as essential components of the sustainable development framework [35]. Expanding access to education and health services is a critical foundation for eradicating poverty and reducing social inequalities [36].

The SDGs are a powerful global call to action, urging individuals, organizations and governments alike to take collective responsibility. Pursuing these ambitious goals is not just a task, but a must to create a sustainable world that protects the well-being of both present and future generations and ensures their well-being and prosperity [37]. In the context of this grand vision, education is proving to be a central cornerstone for achieving the SDGs. Launched by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) program is a dynamic initiative that aims to raise people's awareness of sustainability and inspire them to seamlessly integrate these critical competencies into their daily lives [38]. It is widely recognized that education is a fundamental tool for building a sustainable future, as it significantly improves individuals’ understanding of environmental, social and economic sustainability [39]. Above all, teachers are the heart and soul of this transformative journey. They have the powerful potential to awaken and nurture students’ sustainability competencies and guide them to translate this understanding into meaningful, concrete action [6, 8].

Sustainability competencies

Sustainability competencies provide the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to address environmental, social, and economic sustainability challenges. In physical education (PE), these competencies can be developed through movement-based learning, team activities, and outdoor education, which encourage students to engage with sustainability in practical ways [40]. From a psychological perspective, these competencies align with cognitive and behavioral theories relevant to PE. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development explains how learners construct knowledge through experience—a process mirrored in PE’s emphasis on experiential learning, such as outdoor activities that foster environmental awareness [22]. Bandura’s social cognitive theory highlights observational learning and self-efficacy, which apply to how PE teachers model sustainable behaviors (e.g., responsible resource use in sports facilities) and empower students to adopt them [16].

Social competencies in PE involve promoting fairness, inclusion, and respect through sports and group activities. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development help explain how PE can guide students from self-centered play to cooperative teamwork, reinforcing concepts like equity and social responsibility [41]. Hoffman’s theory of empathy development is also relevant, as PE activities (e.g., mixed-gender or adaptive sports) can cultivate perspective-taking and inclusivity [42]. These psychological foundations help explain how individuals develop the awareness and skills needed to address social problems and foster inclusive communities [2, 38]. Economic competencies in PE include teaching resource efficiency (e.g., managing sports equipment sustainably) and responsible consumption (e.g., reducing waste in school sports events). Insights from behavioral economics, such as Thaler and Sunstein’s"nudging,"can be applied to PE settings—for example, by structuring choices (e.g., reusable water bottles vs. single-use plastics) to encourage sustainable habits among students [43].

Furthermore, self-determination theory (SDT) emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness in motivating individuals to engage in sustainable economic practices [44]. In the context of PE education, SDT can be applied by encouraging students to take initiative in sustainability-related activities, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility for sustainable practices within physical education settings. Environmental competencies focus on fostering the expertise and skills necessary to protect natural resources, implement environmentally friendly practices and ensure the vitality of ecosystems. Psychologically, these competencies can be related to the concept of ecological intelligence, which is about understanding the ecological consequences of human actions and developing empathy for the natural world [45].

Within PE, developing environmental competencies can be achieved through activities that connect students with nature, such as outdoor sports and environmental stewardship projects, thereby directly linking physical education to sustainability goals. For example, initiatives such as recycling, saving energy and minimizing carbon emissions require not only knowledge, but also intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental attitudes influenced by factors such as values, norms and emotional connections to nature [46]. Psychological research suggests that fostering a sense of environmental identity — a personal connection to nature — can increase an individual’s commitment to sustainable practices [47]. PE teachers can play a key role in nurturing this environmental identity by designing lessons that emphasize the impact of physical activity on the environment and encourage students to reflect on their relationship with nature.

Education is a key tool for promoting sustainability competencies and PE teachers play a transformative role in this process. From a psychological perspective, PE teachers can use the principles of experiential learning and self-efficacy to promote sustainability competencies in students. For example, outdoor activities and nature sports provide students with opportunities to interact with the environment, which promotes ecological intelligence and ecological identity [7, 48]. These experiences are consistent with the principles of place-based education, which emphasizes learning through direct engagement with the local environment [49]. By integrating these theories into PE curricula, teachers can create meaningful learning experiences that not only develop physical skills but also foster a deeper understanding of sustainability. In addition, incorporating social issues such as gender equality, cultural diversity and social inclusion into physical education can promote students'moral development and empathy [2, 38, 44]. By creating an inclusive and equitable learning environment, PE teachers can help students develop the social competencies they need to cope with societal challenges. Psychologically, this approach is in line with the concept of cooperative learning, which has been shown to improve social skills and reduce prejudice [50]. Thus, cooperative learning strategies in PE not only enhance teamwork and communication but also support the broader aims of social sustainability.

In terms of economic competencies, PE teachers can use psychological strategies such as goal setting and feedback to promote sustainable behaviors. For example, by organizing activities that align with circular economy principles or using sustainable sports equipment, teachers can teach students the importance of resource efficiency and sustainable consumption [43]. These practices can be reinforced through positive reinforcement and the development of intrinsic motivation as emphasized in SDT [44]. In this way, economic aspects of sustainability are directly addressed within PE lessons, linking theory to practice and reinforcing the relevance of sustainability in students’ everyday lives.

At the heart of fostering sustainability literacy lies the pivotal role of PE teachers. They not only empower students by imparting crucial movement competencies but also inspire a profound understanding of environmental, social, and economic sustainability. By explicitly connecting psychological theories such as SDT, ecological intelligence, and cooperative learning to PE education, the relationship between physical education and sustainability becomes clearer and more actionable. This holistic and transformative approach, deeply interwoven with psychological theories and insightful principles, endows students with the essential knowledge, dynamic skills, and forward-thinking attitudes necessary for flourishing in a future that is both sustainable and thriving [6, 48, 51].

Mindfulness in teaching

Mindfulness, defined as the ability to perceive the present moment without judgment or resistance [52], has received considerable attention in psychology and education because of its profound effects on mental well-being, cognitive functioning, and social-emotional development. Mindfulness is rooted in ancient contemplative traditions and has been adopted into modern psychological practice, most notably through the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program developed by Kabat-Zinn [53]. This program has demonstrated remarkable flexibility and goes beyond stress management to improve learning processes and emotional regulation [25]. From a psychological perspective, mindfulness aligns with theories of attention regulation, emotional intelligence and neuroplasticity, making it a powerful tool for teachers and students in education. Teaching is a demanding profession that is often associated with high levels of stress and burnout. Mindfulness offers teachers a way to deal with these challenges by promoting emotional resilience and self-awareness.

The Mindfulness and Emotional Resilience Program (CARE: Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education) has been shown to be particularly effective in improving classroom interactions by enhancing teachers'emotion regulation and empathy competencies [54]. These findings are supported by psychological theories such as the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, which states that mindfulness can expand teachers'emotional resources so that they can respond more adaptively to stressors [55]. In addition, Schussler et al. [56] found that mindfulness training programs improve student–teacher relationships, which are critical to creating a supportive learning environment. For physical education teachers working in high-energy environments, mindfulness practices can help maintain physical and mental balance, reduce the risk of burnout, and increase job satisfaction [13].

For students, mindfulness practices offer a range of psychological and academic benefits. Research has shown that mindfulness improves concentration, reduces stress responses, and increases academic performance [57]. Klingbeil et al. [58] have shown that school-based mindfulness programs can reduce student anxiety by up to 30%, highlighting the role of mindfulness in promoting emotional well-being. Practices such as yoga and meditation integrated into physical education strengthen the mind–body connection and improve motor competencies and overall physical health [59]. For students with special needs, mindfulness-based activities have been shown to support behavioral regulation and social adjustment, which is consistent with the principles of inclusive education [60].

The neuroscience basis of mindfulness further emphasizes its effectiveness. Studies have shown that mindfulness practices increase activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with executive functions, while decreasing activity in the amygdala, the fear center of the brain [61, 62]. These changes facilitate improved emotion regulation and cognitive flexibility, which are essential for learning and social-emotional development. Recent research also highlights the role of mindfulness in promoting brain plasticity, particularly in children, which supports long-term cognitive and emotional growth [63]. Zenner et al. [64] reported that school-based mindfulness programs led to improved academic performance, which is consistent with the broader literature linking mindfulness to positive educational outcomes [65, 66].

Mindfulness supports social-emotional learning by promoting competencies such as empathy, self-compassion and social skills [67]. These findings are based on psychological theories of emotional intelligence that emphasize the importance of self-awareness and interpersonal understanding [19]. Tao [68] highlighted the role of mindfulness in reducing conflict in the classroom and promoting an inclusive learning environment. Culturally sensitive mindfulness programs have further demonstrated their effectiveness in addressing the diverse needs of students, thereby promoting educational equity [66, 69, 70]. These findings are consistent with the principles of culturally sensitive teaching, which emphasizes the importance of recognizing and valuing students'cultural backgrounds in educational practice [71]. In today's digital age, mindfulness apps such as Headspace and Calm are increasingly being used in education. These tools provide students with flexible and accessible ways to engage in mindfulness practices [72]. However, Hidajat et al. [70] suggest that technology-enhanced mindfulness practices should be aligned with face-to-face teaching to ensure depth and authenticity. This view is supported by research on the importance of human relationships for learning and emotional development [73].

Mindfulness embodies a transformative and comprehensive approach to education that significantly enhances the well-being of teachers and students alike. By seamlessly integrating mindfulness into educational policy and practice, schools can create an enriching environment that supports mental health, promotes academic excellence, and fosters social-emotional growth. Recent research efforts have looked closely at the profound long-term effects of mindfulness practices, highlighting their immense potential to act as a catalyst for positivity and innovation in the education sector [65, 66]. From a psychological perspective, mindfulness is a harmonious complement to the complex theories of attention, emotion regulation and neuroplasticity, making it an indispensable and powerful tool for promoting resilience, empathy and cognitive flexibility in the educational landscape.

Intra-mindfulness

Intra-mindfulness (Intra_MF), defined as the ability to understand and manage one's own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors while establishing a deep connection with oneself [74], is an important concept for educators, especially in the context of their professional lives. This introspective practice aligns with psychological theories of self-regulation, emotional intelligence, and self-awareness, which are essential for effective teaching and personal well-being. When teachers cultivate inner mindfulness, they become more attuned to their emotional states, allowing them to respond to challenges in the classroom with more sensitivity, patience, and understanding [54]. This increased self-awareness not only strengthens their professional identity, but also plays a crucial role in mitigating burnout and stress, thereby increasing job satisfaction [13]. From a psychological perspective, inner mindfulness can be understood through the lens of SDT, which emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence and relatedness in promoting intrinsic motivation and well-being [44].

Mindfulness practices enable teachers to develop a deep understanding of their body and physical capabilities, which is particularly relevant for PE teachers. This somatic awareness contributes to the formation of a strong professional identity as it enables teachers to align their physical and emotional experiences with their role as a teacher [75]. Psychological research on embodiment suggests that mindfulness enhances the mind–body connection, leading to greater self-efficacy and resilience in the professional environment [76]. For PE teachers, this connection is particularly important as their work is inherently linked to physical activity and movement. By integrating inner mindfulness into their practice, PE teachers can model self-awareness and emotional regulation to their students, promoting a holistic approach to education that encompasses physical, social and emotional growth [77].

The practice of inner mindfulness has a transformative effect on teacher-student relationships. When educators are mindful of their own emotions and reactions, they are better able to create a supportive and inclusive environment in the classroom. This is consistent with attachment theory, which emphasizes the importance of secure relationships in promoting emotional well-being and learning [78]. Teachers who practice mindfulness are more likely to demonstrate empathy and patience, which strengthens their relationships with students and enriches the learning process. In addition, recognizing the inherent value of their profession and their role in students'lives can increase teachers'motivation and job satisfaction and make their work more meaningful [77].

Intra_MF is particularly valuable for physical education teachers as their role goes beyond physical education and includes the promotion of social and emotional development. By utilizing their own mindfulness practice, PE teachers can create an environment that supports students'holistic development. Research has shown that mindfulness practices improve teachers'stress management skills and emotional resilience, which is essential for promoting students'physical and mental well-being [79]. For example, Emeljanovas et al. [79] found that PE teachers with high levels of emotional resilience were better able to promote student engagement and motivation, even in challenging contexts such as distance learning.

Studies have consistently shown that mindfulness practices improve student engagement and participation. Teachers who regularly practice mindfulness are calmer and more focused in the classroom, which has a positive impact on student interest and engagement [80]. This is supported by psychological theories of attentional control, which suggest that mindfulness improves the ability to maintain focus and resist distractions [79]. In addition, Zhang et al. [81] found that the level of mindfulness in PE teachers had a significant effect on students'active participation in physical activities and their self-confidence. These findings emphasize the importance of internal mindfulness in creating an engaging and supportive learning environment.

Intra_MF also empowers teachers to integrate sustainability into their teaching practice. By reflecting mindfully on their role in promoting environmental, social and economic sustainability, teachers can impart their knowledge from a broader and more enriching perspective [7]. This is consistent with the principles of transformative learning, which emphasize the importance of critical reflection and self-awareness in promoting meaningful change [80]. Intra-mindfulness is a powerful tool for educators, enabling them to strengthen their professional identity, manage stress and build stronger relationships with students. For physical education teachers, this practice is particularly valuable as it supports the holistic development of students through the integration of physical, social and emotional learning. Psychological theories of self-regulation, emotional intelligence and attachment provide a solid framework for understanding the benefits of mindfulness in education. By incorporating mindfulness into their practice, teachers can create a more engaging, inclusive and sustainable learning environment that ultimately promotes the well-being of themselves and their students.

Interpersonal mindfulness

Interpersonal mindfulness (Inter_MF), defined as the ability to understand and respond appropriately to the emotions, cognitions and needs of others, plays a central role in promoting healthy relationships in educational settings [81]. This concept is deeply rooted in the psychological theories of empathy, emotional intelligence and social cognition, which emphasize the importance of understanding and responding to the emotional states of others for effective communication and relationship building [82]. In the educational context, Inter_MF enables teachers to create a supportive, empathic, and collaborative environment in the classroom that is essential for students'academic, social, and emotional development [28, 83]. Inter_MF is particularly important for teachers as it enhances their ability to recognize and respond to students'emotional needs. This ability is consistent with attachment theory, which emphasizes the importance of secure and empathetic relationships for students'emotional well-being and academic success [78]. For example, mindfulness practices have been shown to reduce negative behaviors such as bullying and promote more cooperative attitudes among students [57]. Research has also shown that students who participate in mindfulness programs show more empathy and strengthen their social competencies [13]. These findings are supported by theories of social-emotional learning (SEL) that emphasize the role of empathy and emotion regulation in promoting positive interpersonal interactions [84].

For physical education teachers, Inter_MF is important for both classroom management and student engagement. Physical education provides a unique environment where social and emotional development is as important as physical activity. Teachers with high levels of Inter_MF are better able to understand and respond to students'individual needs, which promotes motivation, collaboration and overall well-being [65, 85, 86]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of Inter_MF became even more apparent as PE teachers with strong interpersonal mindfulness skills were able to maintain student motivation and engagement through effective communication and empathetic support, even in remote learning contexts [6, 86, 87]. This is consistent with SDT, which emphasizes the importance of relationship and empathy in fostering intrinsic motivation and resilience [15, 44].

Inter_MF has been shown to have a significant impact on students'physical, emotional and social development. Research shows that PE teachers with high levels of Inter_MF can increase students'engagement in physical activities, boost their self-confidence and promote important skills for teamwork and cooperation [86, 87]. For example, Sánchez-García et al. [88] found that PE teachers'inter_MF positively influenced students'perceptions of self-efficacy and increased their participation in physical activities. These findings are consistent with Bandura's theory of self-efficacy, which states that empathetic and supportive interactions between teachers and students can increase students'belief in their abilities and their willingness to engage in challenging tasks [89]. Inter_MF also plays a crucial role in shaping the social dynamics in the classroom.

Teachers with high levels of Inter_MF are more likely to create an inclusive and supportive learning environment, which has a positive impact on students'academic achievement and social competencies [65, 83, 90]. A meta-analysis by Young [91] has shown that teachers with strong Inter_MF skills have deeper bonds with students and foster a more positive classroom climate. These teachers are better able to understand and respond to students'emotional needs, which has a positive impact on students'overall well-being and academic performance. This is supported by research on classroom climate, which emphasizes the role of teacher empathy and mindfulness in creating a sense of belonging and safety for students [92].

Interpersonal mindfulness is a critical skill for educators, especially in physical education, where social and emotional development is an essential part of the learning process. By promoting empathy, emotion regulation and effective communication, Inter_MF enables teachers to create a supportive and inclusive classroom environment that fosters students'physical, emotional and social development. Psychological theories of attachment, emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy provide a solid framework for understanding the benefits of Inter_MF in education. As research continues to highlight the importance of mindfulness in teaching, integrating Inter_MF into teacher training and professional development programs can serve as a catalyst for positive change in education.

The relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competencies in teaching

Mindfulness and sustainability competencies are two interrelated concepts that play a complementary role in education. While mindfulness enhances an individual's ability to experience the present moment with heightened awareness, sustainability competencies equip individuals with the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to address environmental, social and economic challenges [11, 38]. Together, these concepts promote transformative learning, which is essential for promoting sustainable development and empowering individuals to actively engage in change. Research has shown that mindfulness practices can contribute significantly to the development of sustainability competencies. For example, mindfulness promotes sustainable behaviors by fostering a deep connection with nature and strengthening socio-emotional competencies such as emotion regulation, empathy, and social connectedness [93–95].

These competencies are crucial for tackling complex sustainability problems as they enable individuals to face challenges with creativity, resilience and a sense of responsibility. Mindfulness also plays a central role in fostering creativity and innovative thinking, which are essential for solving sustainability-related problems. By encouraging students to think critically and reflectively, mindfulness practices can help them to develop innovative solutions to environmental and social challenges. Furthermore, mindfulness facilitates the development of the ecological self — a concept defined by Albrecht [96] as the ability to perceive oneself as an integral part of the natural world. This heightened sense of connectedness promotes sustainable practices and encourages individuals to take responsibility for the environment.

Physical education teachers are in a unique position to integrate mindfulness and sustainability competencies into their teaching. Through activities such as yoga, meditation and outdoor sports, PE teachers can promote their students'physical and mental well-being while increasing their environmental awareness [2, 38, 83]. For example, guiding students to make sports equipment from recyclable materials not only encourages creativity but also reinforces the principles of sustainability [19, 81]. In addition, mindfulness practices in physical education can improve students'ability to focus their attention, regulate their emotions and manage stress, which enables them to make more informed decisions on sustainability issues [58]. Integrating mindfulness and sustainability competencies into physical education has been shown to be highly beneficial. For example, Santos-Pastor et al. [97] found that mindfulness practices during the pandemic increased students'environmental literacy and promoted the adoption of sustainable lifestyles. Similarly, Delgado-Montoro et al. [10] emphasized the effectiveness of mindfulness in promoting environmental awareness and mental health in students. These studies emphasize the importance of incorporating mindfulness into physical education to promote both physical and environmental literacy.

In addition, activities such as nature walks, outdoor sports, and environmental cleanup initiatives can further enhance students'sustainability literacy while improving their teamwork and collaboration skills [59, 98]. By participating in these activities, students develop a greater appreciation for the natural world and a stronger commitment to sustainable practices. The role of PE teachers in promoting sustainability competencies is particularly important in the context of achieving the SDGs. As UNESCO emphasizes, education systems must cultivate sustainability competencies to empower future generations to tackle environmental and social challenges [2, 38, 99].

By integrating mindfulness practices into their lessons, physical education teachers can help students develop the skills and attitudes required for a sustainable lifestyle. For example, they can emphasize the importance of conserving natural resources, saving energy and recycling, thus promoting students'sense of responsibility for the environment. In summary, the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competencies is a powerful framework for promoting transformative learning in education. By integrating mindfulness practices into physical education lessons, teachers can improve students'physical, emotional and environmental wellbeing while equipping them with the skills they need to tackle sustainability challenges. This holistic approach not only supports the achievement of the SDGs, but also empowers students to become responsible and proactive members of their communities.

The role of demographic factors

Demographic factors such as gender, school level, and education level, play a critical role in shaping the intricate relationship between mindfulness and sustainability literacy in physical education teachers. These factors shape teachers'knowledge, attitudes and competencies and have a major impact on their commitment to sustainability and mindfulness practices. Understanding the transformative impact of these demographic variables is critical to developing accurate and impactful interventions and professional development programs that significantly increase teachers'effectiveness in promoting sustainability.

Gender plays a notable role in shaping teachers'attitudes and competencies related to sustainability and mindfulness. Research shows that female teachers often show greater sensitivity to environmental sustainability and mindfulness practices compared to their male counterparts [100–102]. This difference may be attributed to societal gender roles that traditionally associate women with empathetic, caring, and nurturing behaviors [20]. Hastürk [103], for example, found that female teachers are more environmentally aware and more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. These findings are consistent with gender role theory, which posits that women are socialized to take on roles that emphasize empathy and sensitivity, making them more sensitive to environmental and social issues [20]. However, it is important to point out that these differences may be influenced by cultural and social contexts and that further research is needed to investigate these dynamics in different settings.

The school level in which teachers work also influences their mindfulness and sustainability competencies. Studies suggest that high school teachers tend to address sustainability issues in more depth as they often work with older students who are able to grapple with complex issues [104, 105]. This is consistent with Bandura's social cognitive theory, which emphasizes that learning is shaped by social interactions and environmental contexts [16]. High school teachers may have more opportunities to promote critical thinking and discuss complex sustainability challenges, while middle school teachers are more likely to focus on building foundational knowledge and basic competencies. This distinction reflects the level of cognitive development and learning needs of students at different educational levels, as outlined in the UNESCO Framework for Sustainability Education [38].

The educational level of teachers has a significant impact on their mindfulness and sustainability competencies. Teachers with higher degrees often demonstrate a deeper understanding of sustainability issues and a greater ability to apply this knowledge in practice [48]. Wiek et al. [40] found that educators with postgraduate degrees exhibited higher levels of sustainability literacy and a more comprehensive understanding of environmental challenges. This phenomenon can be explained by Piaget's cognitive development theory, which states that higher cognitive skills enable individuals to better understand and solve complex problems [22]. Furthermore, Mezirow's transformative learning theory highlights that people with higher education are more likely to be able to critically reflect on their thinking patterns and behaviors, leading to transformative changes in their attitudes towards sustainability and mindfulness [80].

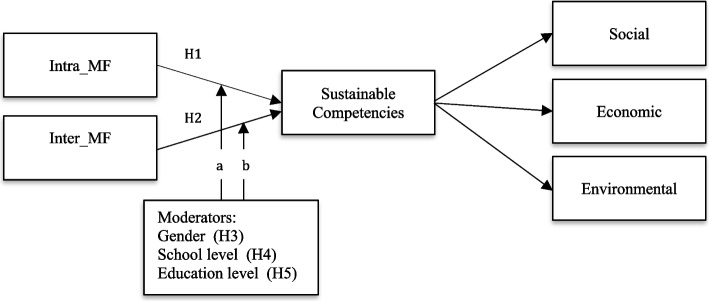

This study investigates the structural relationship between two dimensions of mindfulness — intra_MF and inter_MF — and sustainability competencies in physical education teachers. In addition, the moderating role of demographic factors, including gender, educational level, and school level, in this relationship is examined. The proposed model (Fig. 1) provides a comprehensive framework to understand how these factors influence the interplay between mindfulness and sustainability competencies.

Fig. 1.

Model of the study. In accordance with the research model, the following hypotheses were developed: H1:Intra_MF positively and significantly predicts sustainability competencies. H2: Inter_MF positively and significantly predicts sustainability competencies. H3a: Gender moderates the relationship between intra_MF and sustainability competencies. H3b: Gender moderates the relationship between inter_MF and sustainability competencies. H4a: School level moderates the relationship between intra_MF and sustainability competencies. H4b: School level moderates the relationship between inter_MF and sustainability competencies. H5a: Educational level moderates the relationship between intra_MF and sustainability competencies. H5b: Educational level moderates the relationship between inter_MF and sustainability competencies

This study makes a significant theoretical and practical contribution to this topic. First, it fills a gap in the literature by examining the different roles of intra_MF and inter_MF in shaping PE teachers'sustainability competencies. Second, it highlights the moderating influence of demographic factors and offers insights into how gender, educational level and school level influence this relationship. These findings can inform the design of teacher professional development programs and sustainability education initiatives. For example, gender-specific professional development programs could be developed to address the unique needs of male and female teachers. Similarly, strategies tailored to different educational levels and school levels can improve the effectiveness of sustainability education in different contexts.

In summary, this study provides a solid theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability literacy in physical education teachers. By revealing the moderating role of demographic factors, it offers valuable insights for policy makers and educators seeking to promote sustainability and mindfulness in education. The findings underscore the importance of considering demographic variables in the design of teacher education programs and sustainability initiatives to ultimately contribute to the development of more effective and inclusive educational practices.

Method

Research model

This study employed a cross-sectional design to examine the relationship between PE teachers'mindfulness in teaching and their sustainability competence, as well as the moderating role of demographic factors (gender, educational level, and school level). Cross-sectional models are widely used in educational research to analyze relationships between variables at a single point in time, providing insights into behaviors, attitudes, and competencies [106]. The research model was tested using structural equation modeling (SEM), a statistical method suitable for analyzing complex relationships between observed and latent variables. Additionally, moderator analysis was conducted to determine whether the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competence varied across subgroups (e.g., male vs. female teachers) [107]. This approach is particularly useful in educational research, as it helps identify how individual and contextual factors influence outcomes. By combining SEM and moderator analysis, the study offers a systematic framework for understanding how mindfulness, sustainability competence, and demographic factors interact among PE teachers.

Participants

Physical education teachers working in middle and high schools in Turkey participated in the study. A total of 852 physical education teachers participated in the study, 60.2% of whom were male (n = 513) and 39.8% of whom were female (n = 339). In terms of school level, 38.5% of the teachers worked at middle schools (n = 328), while 61.5% worked at high schools (n = 524). In terms of education level, 61.2% had a bachelor's degree (n = 521) and 38.8% had a college degree (n = 331). The sample size was determined based on the requirements for SEM. A minimum of 5–10 participants per observed variable is recommended in the literature, with more complex models requiring 300 to 500 participants for robust analysis [106]. As the scales used in this study comprised 33 items, a minimum of 165 participants was required, with the ideal sample size being 330. However, to account for the complexity of the model and the number of free parameters, a sample size of 852 was considered appropriate to ensure sufficient reliability and validity for both the model and the subgroup analyzes [107]. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics

| Demographic characteristic | Group | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 513 | 60.2 |

| Female | 339 | 39.8 | |

| School level | Middle School | 328 | 38.5 |

| High School | 524 | 61.5 | |

| Education level | Undergraduate | 521 | 61.2 |

| Graduate | 331 | 38.8 |

Tools for data collection

Physical education scale for sustainable development in future teachers (PESD-FT)

The"Physical Education Scale for Sustainable Development in Future Teachers (PESD-FT), developed by Baena-Morales et al. [108], assesses sustainability competencies in three sub-dimensions: Social (8 items), Economic (6 items) and Environmental (6 items), totaling 20 items. The scale uses an 8-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 8 = strongly agree). Example items are: Social:"I could improve people’s physical ability through physical education", Economic:"I could promote the recognition of local culture and local products during physical education lessons.", Environmental:"I could emphasize the importance of sustainable consumption and production of resources during physical education lessons.". Although the scale was originally developed for prospective PE teachers, in this study it was applied to current PE teachers to assess their sustainability competencies and to examine how demographic factors influence these competencies. The scale was adapted into Turkish using translation and back-translation methods. Two experts translated the scale into Turkish and a third expert back-translated it to ensure accuracy. A panel of three academics reviewed the scale for content, language and cultural appropriateness and made adjustments to improve clarity. A pilot study with 30 PE teachers confirmed the comprehensibility of the scale and led to further refinements.

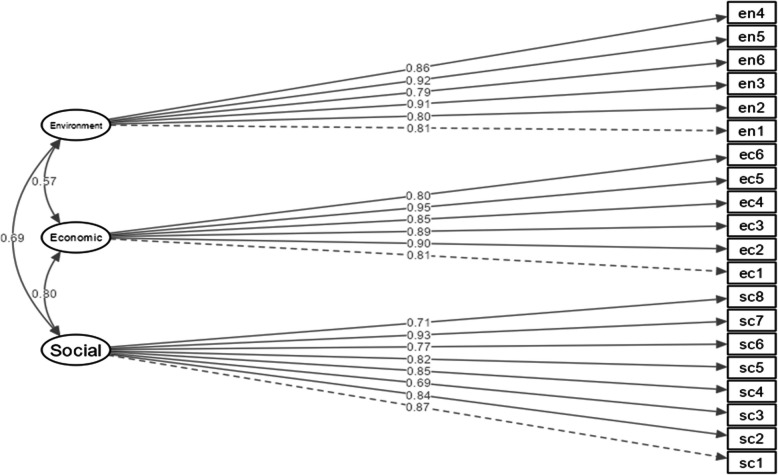

To assess the validity and reliability of the scale, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted method (WLSMV). The WLSMV method is suitable for Likert-type data that violate the assumption of multivariate normality, as confirmed by the Mardia test (p < 0.001). The CFA results showed excellent model fit (X2/df = 1.72, SRMR = 0.049, RMSEA = 0.029 [0.023, 0.035], CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.996) [109]. The factor loadings ranged from 0.70 to 0.95 across all sub-dimensions, indicating a strong representation of the constructs. Internal consistency was high, with Cronbach's alpha values between 0.94 and 0.95. Other reliability measures were omega (ω) and average variance extracted (AVE): social: ω = 0.939, AVE = 0.663, economic: ω = 0.948, AVE = 0.756, environmental: ω = 0.937, AVE = 0.714. These results confirm the reliability and validity of the scale for measuring sustainability competencies in PE teachers, which is supported by established psychometric standards [107, 110, 111]. Figure 2 shows the CFA model diagram illustrating the relationships between the sub-dimensions and the items.

Fig. 2.

PESD-FT model of confirmatory factor analysis

Scale for mindfulness in teaching

The"Mindfulness in Teaching Scale"developed by Frank et al. [112] assesses educators'mindfulness using 14 items divided into two sub-dimensions: intrapersonal mindfulness (Intra_MF, 9 items) and interpersonal mindfulness (Inter_MF, 5 items). The scale uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never applies, 5 = always applies), with 9 items being reverse scored. Example items include: Intra_MF:"I am often so busy thinking about other things that I am not really listening to my students.", Inter_MF:"When I’m upset with my students, I notice how I am feeling before I take action.". The scale was adapted into Turkish by Genç et al. [113] and achieved linguistic equivalence (r = 0.91, p < 0.01) and construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). One item was removed during validation and the two-dimensional structure showed adequate model fit across two data sets (X2/df = 2.02, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.07, GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.89 for the first data set; X2/df = 1.70, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06, GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.89 for the second data set). Reliability analyzes yielded Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.80 for Intra_MF and 0.71 for Inter_MF, with test–retest reliability coefficients of 0.80 and 0.73, respectively [113].

In this study, the Turkish adaptation of the scale was assessed using CFA with a sample of 852 participants. The WLSMV method was used, and the results confirmed the two-dimensional structure with an appropriate model fit (X2/df = 3.04, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96). Although the X2/df value was above 3, this is acceptable for large sample sizes [109]. Internal consistency was strong, with Cronbach's alpha values between 0.82 and 0.91. Omega coefficients were 0.92 for Intra_MF and 0.85 for Inter_MF, while AVE values were 0.60 and 0.57, respectively [107, 110, 111]. These results confirm the validity and reliability of the scale for measuring mindfulness in teaching. Figure 3 shows the CFA model diagram illustrating the relationships between the sub-dimensions and the items.

Fig. 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis model of the Mindfulness in Teaching scale

Data collection process

The data for this study was collected through online surveys in January and February 2024. Online surveys were chosen because of their efficiency, cost-effectiveness and ability to reach a large number of participants quickly [114]. In addition, the anonymity offered by online surveys encourages honest responses, which improves data quality [115]. Participants were recruited via email and social media platforms. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation. They were assured that their data would only be used for scientific purposes and that their anonymity would be preserved. These measures, which are based on ethical research standards, helped to strengthen the participants'trust and ensure compliance with ethical guidelines [116]. A consent form was included to confirm voluntary participation in order to reinforce informed decision-making, a cornerstone of ethical research practices.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections: 1. demographic information: This section collected data on participants'gender, education level, and school level. Demographic data provides an important context for interpreting the results [117]. 2. Sustainability competencies: The Physical Education Scale for Sustainable Development in Future Teachers (PESD-FT) [108] was used to assess participants'sustainability competencies. 3. Mindfulness in teaching: The Mindfulness in Teaching Scale [112] adapted from Genç et al. [113] was used to measure the teachers'level of mindfulness. Both scales used Likert-type response formats. The online data collection method enabled broad participation and compliance with ethical standards. By communicating the purpose of the study and the ethical principles, the study aimed to increase participants'trust and support the validity of the results.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Jamovi software and the R programming language, in particular the SEMLj module in Jamovi and the Lavaan package in R [118, 119]. The Mardia test revealed a violation of the multivariate normality assumption (p < 0.05), which resulted in the use of the WLSMV method for robust analysis. This method is particularly suitable for Likert-type data that do not fulfill the normality assumptions [109]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the construct validity of the scales, as described in the"Data collection instruments"section. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the relationship between mindfulness (Intra_MF and Inter_MF) and sustainability competencies in teaching.

Model fit was assessed using indices such as RMSEA, SRMR, CFI, TLI and IFI. Values of RMSEA and SRMR below 0.08 and CFI and TLI above 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit, while values above 0.95 indicate an excellent fit [109]. A moderation analysis was performed to assess the role of demographic variables (gender, education level and school level) in this relationship. A simple slope analysis was performed to assess the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable at different levels of moderators (mean, low −1SD, high + 1SD).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Results of the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis are presented in Table 2. Mean scores were 127.81 (SD = 16.59) for sustainability competencies, 33.68 (SD = 5.01) for Intra_MF, and 20.66 (SD = 2.67) for Inter_MF. The distribution of scores showed skewness values between −0.61 and −1.74 and kurtosis values between 0.09 and 2.59, indicating normal distribution as values fell within acceptable ranges (skewness ± 2, kurtosis ± 7) for SEM analysis with large samples [109, 120]. Correlation analysis showed a moderate positive correlation between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), a weak positive correlation between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), and a very weak positive correlation between Intra_MF and Inter_MF (r = 0.09, p < 0.01). These correlation coefficients align with conventional interpretations of weak (± 0.10–0.29), moderate (± 0.30–0.49), and strong (± 0.50 +) relationships [121].

Table 2.

Descriptive and correlative analysis results

| Variables | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Sustainability competencies | 127.81 | 16.59 | −0.61 | 0.09 | 1 | ||

| 2. Intra_MF | 33.68 | 5.01 | −1.74 | 2.59 | 0.37*** | 1 | |

| 3. Inter_MF | 20.66 | 2.67 | −1.27 | 1.65 | 0.21*** | 0.09** | 1 |

**p <.01, ***p <.001

Results of the structural equation model analysis

The structural equation model analysis showed positive relationships between physical education teachers'mindfulness (both Intra_MF and Inter_MF) and their sustainability competencies. The model demonstrated acceptable fit based on the following indices: χ2/df = 3.05, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI [0.04, 0.05]), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, and IFI = 0.98. While the χ2/df ratio slightly exceeded 3, this is considered acceptable for large sample sizes, and the other indices supported the model's good fit [109].

In the measurement model, the strongest factor loadings were observed for Intra_MF with im2 (β = 0.85, p < 0.001) and im6 (β = 0.84, p < 0.001), for Inter_MF with ip3 (β = 0.78, p < 0.001) and ip4 (β = 0.78, p < 0.001), for social competence with sc1 (β = 0.89, p < 0.001) and sc7 (β = 0.92, p < 0.001), for economic competence with ec2 (β = 0.90, p < 0.001) and ec5 (β = 0.94, p < 0.001), and for environmental competence with en3 (β = 0.92, p < 0.001) and en5 (β = 0.93, p < 0.001). The standardized coefficients indicated that Intra_MF had a stronger association with sustainability competencies (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) than Inter_MF (β = 0.17, p < 0.001). The model accounted for 22% of the variance in sustainability competencies (R2 = 0.22), suggesting that while mindfulness dimensions are significant predictors, additional factors likely influence these competencies. Figure 4 presents the complete SEM model.

Fig. 4.

SEM model between Intra_MF and Inter_MF and sustainability competencies

The reliability analysis for the scale constructs is summarized in Table 3. Cronbach's alpha (α) values were between 0.82 and 0.95 and McDonald's omega (ω) values were between 0.82 and 0.96, indicating strong internal consistency for all scales and sub-dimensions. Both coefficients exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 and confirmed the reliability of the scales [110]. McDonald's omega is particularly advantageous as it provides more accurate reliability estimates, especially when factor loadings are not uniform [122]. The values of the average variance extracted (AVE) additionally underpinned the validity of the constructs: Mindfulness in the classroom: Intra_MF (AVE = 0.58), Inter_MF (AVE = 0.52). Sustainability competencies: Social competence (AVE = 0.66), economic competence (AVE = 0.76), environmental competence (AVE = 0.71). According to established guidelines, AVE values above 0.50 confirm the convergent validity of the constructs, which indicates that the measurement models correspond well with the theoretical constructs [111].

Table 3.

Reliability indices

| Variable | α | ω | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness in teaching | 0.86 | 0.87 | |

| Intra_MF | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.58 |

| Inter_MF | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.52 |

| Sustainability competencies | 0.95 | 0.96 | |

| Social | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.66 |

| Economic | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.76 |

| Environment | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.71 |

Moderating role of demographic variables on Intra_MF and sustainability competencies

The study examined whether gender, school level, and educational level moderated the relationship between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies. As shown in Table 4, all three variables showed significant moderating effects: gender (β = 0.46, p = 0.03), school level (β = 0.67, p < 0.001), and educational level (β = 0.46, p = 0.03). The analysis revealed that: male teachers had a stronger association between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies than female teachers; high school teachers showed a more substantial relationship than middle school teachers; and teachers with graduate degrees demonstrated a stronger link than those with undergraduate degrees. These results suggest that demographic characteristics influence how Intra_MF relates to sustainability competencies, which could inform the design of professional development programs.

Table 4.

Moderation estimates for the role of demographics in intra_mf and sustainability competencies

| Estimate | SE | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra_MF | 0.59 | 0.09 | 6.80 | <.001 |

| Gender | −23.83 | 0.73 | −32.73 | <.001 |

| Intra_MF ✻ Gender | 0.46 | 0.21 | 2.16 | 0.03 |

| Intra_MF | 1.43 | 0.10 | 14.18 | <.001 |

| School Level | 5.61 | 1.03 | 5.44 | <.001 |

| Intra_MF ✻ School Level | 0.67 | 0.20 | 3.30 | <.001 |

| Intra_MF | 0.85 | 0.12 | 7.25 | <.001 |

| Education level | −13.42 | 0.96 | −13.98 | <.001 |

| Intra_MF ✻ Education level | 0.46 | 0.22 | 2.12 | 0.03 |

The simple slope analysis (Table 5) revealed variations in the association between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies across demographic subgroups. For gender differences, female teachers showed a stronger association (β = 0.82, p < 0.001) than male teachers (β = 0.37, p = 0.03). Regarding school level, high school teachers demonstrated a more substantial association (β = 1.76, p < 0.001) compared to middle school teachers (β = 1.10, p < 0.001). For educational attainment, teachers with graduate degrees exhibited a stronger association (β = 1.07, p < 0.001) than those with undergraduate degrees (β = 0.62, p < 0.001). These findings indicate that gender, school level, and educational background moderate the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability competencies in physical education teachers.

Table 5.

Simple slope analysis for the moderation of intra_mf and sustainability competencies by demographics

| Estimate | SE | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Average | 0.59 | 0.09 | 6.77 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | 0.37 | 0.17 | 2.17 | 0.03 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 0.82 | 0.09 | 9.12 | <.001 |

| School Level | ||||

| Average | 1.43 | 0.10 | 14.09 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | 1.10 | 0.13 | 8.21 | <.001 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 1.76 | 0.15 | 11.82 | <.001 |

| Education level | ||||

| Average | 0.85 | 0.12 | 7.24 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | 0.62 | 0.20 | 3.10 | 0.00 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 1.07 | 0.10 | 10.64 | <.001 |

Moderating role of demographic variables on Inter_MF and sustainability competencies

The study examined whether gender, education level, and school level moderate the association between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies. As shown in Table 6, gender demonstrated a significant moderating role (β = 1.28, p < 0.001), with the Inter_MF-sustainability competencies association varying between male and female teachers. Educational level also showed a moderating pattern (β = 0.71, p = 0.04), where teachers with higher qualifications exhibited a stronger Inter_MF-competencies link. In contrast, school level did not show statistical significance as a moderator (β = 0.25, p = 0.54). These findings suggest that while gender and educational background influence how interpersonal mindfulness relates to sustainability competencies, school level does not appear to be a determining factor in this relationship.

Table 6.

Moderation estimates for the role of demographics in inter_mf and sustainability competencies

| Estimate | SE | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter_MF | 0.57 | 0.15 | 3.90 | <.001 |

| Gender | −25.07 | 0.75 | −33.49 | <.001 |

| Inter_MF ✻ Gender | 1.28 | 0.33 | 3.92 | <.001 |

| Inter_MF | 1.65 | 0.20 | 8.13 | <.001 |

| School level | 5.95 | 1.11 | 5.38 | <.001 |

| Inter_MF ✻ School level | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Inter_MF | 1.08 | 0.18 | 5.78 | <.001 |

| Education level | −15.40 | 0.99 | −15.51 | <.001 |

| Inter_MF ✻ Education level | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.93 | 0.04 |

The simple slope analysis (Table 7) examined the association between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies across demographic subgroups. Three main patterns emerged: First, a significant association was found for female teachers (β = 1.20, p < 0.001) but not for male teachers (β = −0.06, p = 0.82). Second, both middle school (β = 1.53, p < 0.001) and high school teachers (β = 1.77, p < 0.001) showed similar associations, suggesting school level does not moderate this relationship. Third, teachers with graduate degrees demonstrated a stronger association (β = 1.43, p < 0.001) than those with undergraduate degrees (β = 0.74, p = 0.01). These findings indicate that while gender and educational level differentiate how interpersonal mindfulness relates to sustainability competencies, school level does not appear to be a relevant factor in this association.

Table 7.

Simple slope analysis for the moderation of inter_mf and sustainability competencies by demographics

| Estimate | SE | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Average | 0.57 | 0.15 | 3.85 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | −0.06 | 0.25 | −0.23 | 0.82 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 1.20 | 0.18 | 6.72 | <.001 |

| School level | ||||

| Average | 1.65 | 0.20 | 8.13 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | 1.53 | 0.27 | 5.70 | <.001 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 1.77 | 0.30 | 5.95 | <.001 |

| Education level | ||||

| Average | 1.08 | 0.19 | 5.77 | <.001 |

| Low (−1SD) | 0.74 | 0.29 | 2.54 | 0.01 |

| High (+ 1SD) | 1.43 | 0.23 | 6.36 | <.001 |

The study hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) and moderation analysis based on the proposed model (Fig. 1). As summarized in Table 8, the analysis showed significant associations between both Intra_MF and Inter_MF with sustainability competencies, with Intra_MF demonstrating a stronger relationship. Demographic variables including gender, education level, and school level were found to moderate these associations to varying extents. Table 8 presents the detailed results and indicates which hypotheses were supported by the data.

Table 8.

Confirmation of the hypotheses

| Hypotheses | Confirmation status | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Intra_MF positively and significantly predicts sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H2 | Inter_MF positively and significantly predicts sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H3a | Gender moderates the relationship between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H3b | Gender moderates the relationship between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H4a | School level moderates the relationship between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H4b | School level moderates the relationship between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies | Rejected |

| H5a | Educational level moderates the relationship between Intra_MF and sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

| H5b | Educational level moderates the relationship between Inter_MF and sustainability competencies | Confirmed |

Discussion

This study identified a relationship between PE teachers'mindfulness levels (Intra_MF and Inter_MF) and their sustainability competencies. Recent research by Javaid et al. [123] on workplace mindfulness supports our findings, demonstrating how mindfulness mediates between quality of life and stress management among educators, which may similarly influence sustainability integration in teaching practices. The analysis showed Intra_MF had a stronger association with sustainability competencies than Inter_MF, suggesting the relevance of teachers'emotion and cognitive regulation skills. Additionally, demographic factors including gender, education level, and school level moderated this relationship, indicating contextual variations in how mindfulness relates to sustainability competencies. The findings align with social cognitive theory [16], which describes the role of self-regulation in behavior, and transformative learning theory [80], which addresses how reflection and awareness contribute to learning processes. The connection between mindfulness and environmental factors is further supported by Javaid et al. [124], whose work on environmental identity and satisfaction provides additional theoretical grounding for our observed mindfulness-sustainability relationship. Previous research on service-learning (SL) models has demonstrated their effectiveness in developing teachers'competencies related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [125]. Such approaches may help teachers integrate sustainability into their professional practice.

The results indicate a relationship between PE teachers'Intra_MF and Inter_MF and their sustainability competencies. Specifically, Intra_MF showed a positive correlation with sustainability competencies, supporting hypothesis 1 (H1). This association suggests that teachers'emotional and mental awareness may contribute to integrating sustainability into pedagogical practice. Teachers with higher Intra_MF scores tend to demonstrate better stress and emotion management, which could help address students'social and emotional needs and potentially encourage sustainable behaviors [13, 28, 57]. These findings are consistent with transformational learning theory [80], which suggests that teachers'personal development can influence student outcomes. The study also found that higher Intra_MF in teachers relates to both professional performance and students'social-emotional development [6, 7, 57]. Additionally, teachers'emotional regulation appears to strengthen their classroom management self-efficacy [126]. In summary, the study underscores the central role of mindfulness in improving teachers'and students'sustainability competencies and highlights the need for mindfulness-based professional development programs in education. Collectively, the results point to mindfulness as a relevant factor for sustainability competencies in education, supporting the consideration of mindfulness-based professional development programs.

The results support hypothesis 2 (H2), indicating that Inter_MF is associated with PE teachers'sustainability competencies. This finding suggests the relevance of teacher-student interactions for developing sustainability competencies. Consistent with Social Cognitive Theory [16], mindful social interactions may contribute to students'sustainability competencies. Research indicates that teachers'Inter_MF behaviors can affect students'motivation and emotional well-being in physical education, with supportive behaviors showing positive associations and controlling behaviors negative associations [127]. Studies by Baena-Morales et al. [7] suggest that Inter_MF may enhance teachers'communication skills and potentially increase student engagement with sustainability topics. These findings point to Inter_MF as a factor in facilitating teacher-student interactions that support sustainability competencies [13, 60]. In summary, Inter_MF appears to influence classroom dynamics and sustainability competencies, which could inform the development of training programs to enhance teachers'interpersonal skills.

The study found that gender moderates the relationship between Intra_MF, Inter_MF and sustainability competencies, supporting hypotheses H3a and H3b. Specifically, female teachers demonstrated a stronger association between mindfulness and sustainability competencies compared to male teachers. This finding aligns with Gender Role Theory [20], which suggests women may tend to adopt more empathic approaches that could facilitate addressing sustainability issues. Previous research by Baena-Morales et al. [7] reported higher sustainability competencies among female teachers, while Roeser et al. [13] noted that emotional intelligence may contribute to these competencies. These results indicate gender differences should be considered in sustainability education, potentially informing tailored mindfulness-based training programs. Further research could explore how gender influences sustainability competency development in educational settings.