Abstract

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women in the United States, representing ~30% of all new female cancer cases annually. For the year 2024, it is estimated that 310,720 new instances of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed, and breast cancer will be responsible for over 42,000 deaths among women. Today, despite the availability of numerous treatments for breast cancer and its symptoms, most cancer-related deaths result from metastasis for which there is no treatment. This emphasizes the importance of early detection and treatment of breast cancer before it spreads. For initial detection and staging of breast cancer, clinicians routinely employ mammography and ultrasonography, which, while effective for broad screening, have limitations in sensitivity and specificity. Advanced biomarkers could significantly enhance the precision of early detection, enable more accurate monitoring of disease evolution, and facilitate the development of personalized treatment plans tailored to the specific molecular profile of each tumor. This would not only improve therapeutic outcomes, but also help in avoiding overtreatment and the associated side effects, thereby improving the quality of life for patients. Thus, the pursuit of novel biomarkers, potentially encompassing metabolomic and lipidomic signatures, is essential for advancing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. In this brief review, we will provide an overview of the current translational potential of metabolic and lipidomic biomarkers for predicting breast cancer prognosis and response to therapy.

Subject terms: Cancer metabolism, Metabolomics

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women in the United States, representing ~30% of all new female cancer cases annually. For the year 2024, it is estimated that 310,720 new instances of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed, and breast cancer will be responsible for over 42,000 deaths among women1. Today, despite the availability of numerous treatments for breast cancer and its symptoms, most cancer-related deaths are still predominantly due to metastasis2. While there are treatments available that can manage metastatic breast cancer and improve quality of life, it remains incurable, and the focus is often on extending life rather than achieving a cure3. This fact emphasizes the necessity for comprehensive management strategies that prioritize prevention, early detection, and vigilant monitoring throughout the course of breast cancer. Despite clinical advances in these areas, not all cases of breast cancer can be intercepted before progressing to stage IV, whether at initial diagnosis or through recurrence4. This limitation highlights the complexity of breast cancer and current gaps in management. It underscores the need for continued research into effective therapies to reduce the incidence of advanced disease.

The primary breast tissue biomarkers currently used in clinical practice to guide treatment decisions include hormone receptor status (estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)5. These receptors are identified through pathological analysis and play an important role in determining the most appropriate treatment approach for patients with breast cancer5. Breast cancer is further classified into subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and Basal-like), each with distinct biological characteristics. This classification informs prognosis and guides treatment decisions tailored to the unique features of each cancer6, but are not comprehensive in predicting disease progression or response to therapy across all patient subtypes7.

Breast cancers can also vary widely in terms of their genetic and molecular characteristics, their response to treatments, and their potential for aggressiveness and metastasis8. Due to this heterogeneity, there is a need for more robust and sensitive biomarkers capable of predicting the risk of breast cancer progression as well as response to therapies. Advanced biomarkers could significantly enhance the precision of early detection, enable more accurate disease monitoring, and facilitate the development of personalized treatment plans tailored to the specific molecular profile of each tumor. This would not only improve therapeutic outcomes but also help avoid overtreatment and its associated adverse effects, thereby improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Thus, pursuing novel biomarkers, potentially encompassing metabolomic and lipidomic signatures, is essential for advancing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. The utility of metabolomics is emphasized by its proven capability to detect early metabolic signatures indicative of disease states in longitudinal studies, often well before clinical symptoms become evident. Notably, early metabolic markers have been identified for diseases such as multiple sclerosis, pancreatic cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive decline4–10. Recently, it has been demonstrated that lipids can be used as biomarkers with health-to-disease transitions as observed through comprehensive lipidomic profiling of longitudinally collected plasma samples, thus highlighting the role of lipidomic changes in diabetes, ageing, inflammation, and immune homeostasis11. The demonstrated ability of metabolomics and lipidomics to predict and correlate with various disease states, and the heightened metabolic and lipid adaptations that take place in cancer cells compared to non-cancer cells suggests predicting cancer progression with metabolic and lipidomic biomarkers is feasible12. For example, metabolomics and lipidomics have recently been employed to map out and elucidate intratumor metabolic heterogeneity in the context of gastric cancer13.

Recent studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the metabolic landscape in breast cancer, highlighting the complexity and clinical relevance of metabolic stratification. Studies have identified distinct metabolic subtypes of human breast tumors, underscoring their potential therapeutic implications and clinical relevance14. This stratification could guide personalized treatment strategies, improving patient outcomes. A recent study further explored the metabolic heterogeneity within cancers, emphasizing the diverse metabolic adaptations that tumors undergo to survive and proliferate15. Another study utilized spatially resolved multiomics to reveal cell-specific metabolic remodeling in gastric cancer, demonstrating the intricate metabolic interactions at the cellular level, which may also be applicable to breast cancer research13. Recent work has highlighted the burgeoning field of spatial metabolomics, suggesting that it could drive innovation in cancer research by providing more detailed metabolic maps of tumors16. A recent study investigated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, showing how these tumors adapt their metabolism to different tissues while retaining essential metabolic signatures, which is crucial for understanding metastasis17. Finally, the role of metabolites in the tumor microenvironment has recently been explored, detailing how metabolic interactions between cancer cells and their surroundings can influence systemic metabolism, potentially offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention18. Together, these studies underscore the importance of metabolic profiling in cancer.

In this brief review, we will provide an overview of the current translational potential of metabolic and lipidomic biomarkers for predicting breast cancer prognosis and response to therapy.

Metabolomic biomarkers of breast cancer progression

Metabolic processes shape the functional dynamics of cancer cells and their progression19. Metabolomics, the study of these processes, offers a precise method to understand how physiological conditions relate to both external influences and diseases. Metabolites are particularly useful in this context because they act as immediate indicators of disease processes and can serve as direct biomarkers reflecting pathogenic activities. Metabolomics provides an intricate and comprehensive view of biological processes and metabolic pathways, positioning it as a potentially pivotal tool in precision medicine for offering a precise and objective molecular-level analysis20. This omic technique further provides direct readouts, through metabolic maps and profiles, that have the potential to predict metabolic states ranging from the cellular level to the organ of interest16.

Recent innovations in highly sensitive, low-input assays allow for detailed profiling of the metabolome and lipidome from minimal amounts of biological samples, which is revolutionizing the use of lipidomics and metabolomics as biomarkers for tracking the progression of diseases such as breast cancer21. In cancer, fundamental shifts in metabolic pathways have been demonstrated to promote cancer progression in mouse and patient samples22. For instance, cancer cells have been shown to capitalize on glucose uptake and downstream shifts in metabolic processes to provide maximal cellular fuel to maintain cancer cell growth and proliferation23. Furthermore, tumors are dependent on metabolites to sustain growth and survival, and are able to adapt nutrient usage in response to the nutrient availability18.

Amino acid metabolism has also been shown to be altered in cancer cells compared to non-cancer cells24. Cancer cells require and exploit glutamate as it is a precursor molecule for various growth signaling pathways and thus is critical for cell proliferation24. Proline catabolism, by the enzyme proline dehydrogenase (PRODH), has been shown to play a crucial role in supporting the growth and spread of metastatic breast cancer cells, as demonstrated in both 3D culture systems and in vivo mouse models25. Elevated PRODH expression and proline catabolic activity were observed in metastatic tumors compared to primary tumors, indicating its potential as a biomarker and/or target for breast cancer progression25.

Additional metabolite markers, including lactate, β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, glycoproteins, pyruvate, glutamate, and mannose, have been shown to be increased in early cases of breast cancer26–28. The presence of altered metabolic pathways for early breast cancer detection has also been noted in patient samples, notably those involving taurine, hypotaurine, and the metabolism of amino acids such as alanine, aspartate, and glutamate, thus highlighting these metabolites as potential biomarkers of breast cancer progression28. Redox imbalance is also a hallmark of metabolic adaptations as cancer cells tend to experience higher levels of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction29,30. Studies have shown that breast cancer cells upregulate antioxidant pathways to maintain redox balance and sustain cell survival31.

In the PAM50 classification of breast cancer, Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-subtypes subtypes have defined metabolic and lipidomic signatures that have been determined to have clinical relevance. In this classification system, tumors classified as Luminal A are characterized by the presence of ER and/or PR and the lack of HER2; clinically, these tumors are typically low-grade and slow-growing as they rely more on oxidative phosphorylation making the cancer type less aggressive32. This tumor subtype has moderate lipid synthesis as it affects cholesterol metabolism which can be controlled, further reflecting the subtype’s less aggressive nature33. Like Luminal A, Luminal B tumors are ER-positive and HER2-positive, yet they are PR-negative34. This tumor type has higher glycolytic activity and elevated lipid synthesis, which supports cell growth, making the subtype more aggressive in nature35. The HER2-enriched subtype has an overexpression of the HER2 protein. Similar to the Luminal B subtype, HER-enriched has increased glycolytic activity as well as glutamine metabolism and increased lipid biosynthesis which contributes to the overall aggressiveness of the HER2 positive subtype36. Specifically, the overexpression of HER2 can modulate lipid metabolism by promoting an upregulation in gene expression of fatty acid synthesis and uptake, including CD36, which is involved in the uptake of fatty acids and oxidized low-density lipoproteins, and the expression of which has been linked to an overall poor prognosis37. Finally, the Basal-like subtype, unlike the aforementioned types, lacks the ER, PR, and HER2 receptors38. This subtype is also able to readily exploit glycolytic pathways to promote cell proliferation even in normoxic conditions making it one of the most aggressive subtypes39. To meet high energy demands, these cancer cells have high lipid uptake and fatty acid oxidation39. Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-subtypes have unique clinical signatures that influence prognosis and treatment triaging for breast cancer.

Distinct metabolic changes may occur in the different tissue environments to which breast cancer metastasizes17. These specific changes in metabolism could provide valuable insights, potentially serving as indicators for the prediction of breast cancer spread to specific distant metastatic sites such as lymph nodes. Furthermore, previous work has shown that patients with breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy may achieve a pathologic complete response in the breast, yet not replicate the same response in the axillary lymph nodes, revealing a discordant treatment outcome depending on metastatic site40. The unique behavior of cancer within lymph nodes, as opposed to the primary tumor site, can be linked to the specific microenvironment within the lymphatic system. This environment not only facilitates the transportation and dissemination of cancer cells but also shapes their growth, survival, and responsiveness to treatment, setting it apart from other tissue environments41,42.

Studies have demonstrated that metabolites in the lymph node correlate with cancer progression to lymph nodes; cancer cells expressing arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase-1 can not only cause damage to the lymph endothelium, but also facilitate the entrance of tumor cells into the vessel; making it a key candidate metabolite in the progression of cancer43. Similarly, studies have shown breast metastatic spread through the lymph nodes has shown an upregulation in PRODH as well as asparagine synthetase, thus proline and asparagine are metabolites of interest in progression of lymph node metastatic breast cancer25. Because cancer cells in the lymph node tumor microenvironment undergo metabolomic reprograming, the altered nutrient environment presents an opportunity for the identification of metabolites as biomarkers in cancer progression17,44. Nevertheless, the lymphatic tumor microenvironment represents an under-researched area for biomarkers pertinent to breast cancer progression. Furthermore, breast cancer cells in other distant metastatic sites (including lung, liver, brain, and bone) likely undergo metabolic alterations that could be detected by unique metabolomic/lipidomic profiling of tissues from different metastatic locations.

Currently, changes in specific metabolites during disease progression have led to the identification of biomarkers for some, but not all cancers44. however, no definitive metabolic biomarkers have yet been identified in breast cancer that can predict disease progression in patients45. Prior work has shown that glucose, threonine, and beta-hydroxybutyrate are upregulated in the blood and correlate with nonspecific symptoms of breast cancer like weight loss and fatigue46. Further studies in patient samples have shown metabolites such as glycine, taurine, lactate, and succinate are increased, and glucose and inositol are decreased in breast cancer tissues compared to non-tumorous tissue47. A recent study has shown that metabolomics can provide a prognostic framework to identify distinct metabolomic profiles in serum samples that differentiate early from metastatic breast cancer, thereby enhancing the precision of risk stratification and therapeutic decision-making of conventional clinical methodologies48. Another study using patient samples explored the metabolic landscape of breast cancer and subsequently identified three distinct breast cancer subtypes that correlated with tumor aggressiveness and patient outcomes; these subtypes showed pronounced dysregulation in bile-acid biosynthesis, methionine pathway, fatty acid metabolism, and glucose metabolism14.

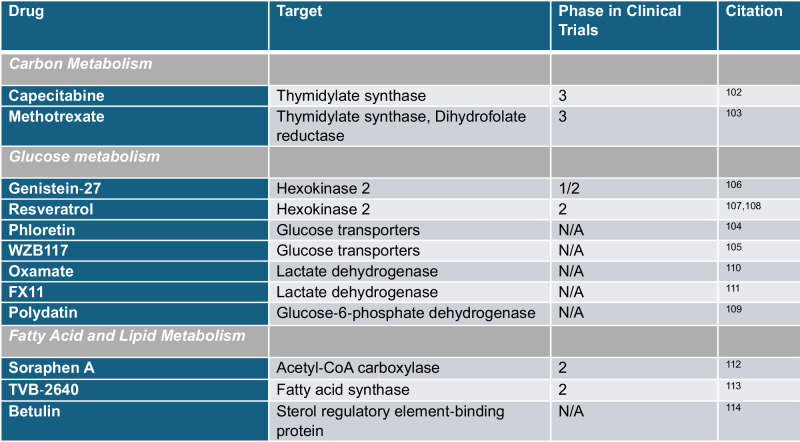

Given that cancer is metabolically active disease, the identification of metabolites that serve not only as biomarkers but as necessary agents of cancer progression could provide the opportunity to intervene with antimetabolite therapeutics49, such as those reviewed in Fig. 1 and Table 1. For instance, if a breast cancer patient’s lymph node metabolomic analysis indicates upregulation in folate metabolism, clinicians could tailor a treatment plan that includes methotrexate, an antimetabolite that inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, thus depleting folate, to potentially enhance the efficacy of standard chemotherapy and mitigate cancer progression50.

Fig. 1. Representative anti‐cancer drugs targeting carbon, glucose, and fatty acid metabolism.

A Carbon metabolism has revealed various targets of interest in the folate synthesis pathway. Metabolomic techniques have led to the development of drugs like methotrexate and capecitabine to target thymidylate synthase102 and methotrexate to target key enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR)103. B Glucose metabolism modulators target glucose transporters phloretin104 and WZB117105 as well as key enzymes in the glycolytic pathway like inhibition of hexokinase 2 via Genistein-27106 and Resveratrol107,108. Within the same pathway, metabolomic techniques have further pioneered anti-cancer drugs targeting glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), like Polydatin109 which inhibits glycolysis, as well drugs targeting the conversion of pyruvate to lactate via the key enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) with Oxamate110 and FX11111. C Fatty acid metabolism targets include Betulin which inhibits sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP-1). At a synthesis level, key enzymes acetyl-CoA carboxylase is inhibited via Soraphen A112 and fatty-acid synthase by TVB-2640113,114. Figure generated with BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Summary of pilot and pre-clinical studies referenced in manuscript text.

Lipidomic biomarkers of breast cancer progression

Lipids, such as sterols and various forms of glycerides and phospholipids, are critical hydrophobic compounds that form the structure of cell membranes and are integral to processes like energy storage and cell signaling within the cell51. In cancer, notably in breast cancer, there is a profound remodeling of lipid metabolism, characterized by increased de novo lipogenesis and alterations in lipidomic profiles due to the rapid proliferation and metabolic demands of cancer cells, which is heightened during tumor progression44,52. Prior work has shown that cancer cells can enhance lipolytic pathways to metabolize stored triglycerides and fatty acids, which are crucial for maintaining rapid cell division and invasion53. These modifications are not merely a consequence of cancer but also contribute to tumor progression and metastasis by providing necessary components for cell membrane formation and energy production.

Furthermore, lipid metabolism in cancer is influenced by the need for various biological processes, such as the production of steroid hormones, vitamins, bile acids, and eicosanoids. This requirement is met through a combination of dietary intake and endogenous synthesis, with most cancer cells depending more heavily on exogenous lipids due to their increased metabolic requirements54–58. Altered lipid metabolism in cancer not only supports the energy and structural needs of proliferating cells but also mediates stress responses, such as endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis, further exacerbating cancer phenotypes53,59,60. Cancer cells also often upregulate lipolytic pathways where lipolysis and β-oxidation, may be activated in cancer cells61. This ensures that cells can then breakdown stored triglycerides and fatty acids to sustain proliferation61. Lipidomic studies in patient breast cancer samples also have revealed a correlation between lipid profiles and both the type of cancer tissue and the tumor grade. Another significant shift observed with tumor growth is the change in the balance of choline-containing compounds62,63.

Lipid metabolism plays a critical role in breast cancer as lipid remodeling can shape the tumor microenvironment by altering immune cell responses64. Specifically, tumor cells can alter the tumor microenvironment by secreting signaling molecules and can exacerbate cancer progression as cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cell function become compromised65. The direct effect on cancer cells can disrupt many processes and specifically alter lipid metabolism in cancer cells by enhancing lipid biosynthesis by promoting an upregulation in fatty acid, cholesterol, and phospholipid synthesis to promote cell growth53. The accumulation of lipid droplets in cancer cells can subsequently inactivate immune signaling molecules to foster a hospitable environment by providing the necessary energy reserves and redox balance66.

Lipid metabolism remodeling further hinders cancer phenotypes through its direct association with myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as tumor-infiltrated MDSC upregulates fatty acid uptake and oxidation67. Myeloid cells have been deemed regulators of metastasis and cancer/tumor progression as they negatively regulate immune responses; regulation is dependent on the type of myeloid cell involved which can include and range from polymorphonuclear neutrophils, eosinophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, megakaryocytes, and basophils67. TAMs also support tumor growth as lipid metabolism can reprogram cells to a pro-tumorigenic state67. The lipid tumor microenvironment can also reshape how cancer cells behave and facilitate metabolic reprogramming, as lipids are a source of energy. The readily available abundance of energy provided by lipids is able to sustain cancer cell growth and proliferation as cancer cells can use fatty acids undergo beta oxidation to generate adenosine triphosphate68. Lipids, like prostaglandins, within the TME, can further modulate an immune response due to their ability to readily suppress and alter immune function; they can further promote the formation of new blood vessels or angiogenesis to further supply nutrients necessary for tumor growth69.

Given these significant changes in lipid metabolism, lipidomics emerges as a promising field for developing biomarkers for breast cancer progression. By analyzing the lipid profiles of cancer cells, particularly the patterns of lipid synthesis, remodeling, and breakdown, lipidomics can offer valuable insights into the metabolic state of tumors. This understanding could lead to novel therapeutic strategies targeting lipid biosynthesis and metabolism, potentially decreasing cancer progression.

Influence of environmental and lifestyle factors on metabolome and lipidome

Metabolomics and lipidomics have facilitated new insights into the connections between environmental and lifestyle factors (such as dietary factors) and disease states70. For example, branched-chain amino acids have been associated with obesity and insulin resistance71, and physical activity and dietary-associated changes are known to induce extensive alterations to the plasma metabolome and lipidome72. Plasma levels are directly influenced by dietary intake as consumption of food and drinks provides the body with nutrients, fats, vitamins, mineral and proteins that can be absorbed into the bloodstream73,74. Depending on the content of the diet, metabolic pathways can become enriched as substrates necessary to carryout processes become readily available. For example, a diet high in carbohydrates will raise plasma glucose levels as the carbohydrates provide the substrates necessary to fuel glycolytic pathways45. This will most typically result in a higher presence of glucose related metabolites being enriched from metabolomic analysis. To a similar degree, a diet high in fat content would most likely reveal an elevated lipid and cholesterol panel as the substrates necessary for the metabolic pathways associated would be available75. Because cancer cells can readily rewire their metabolism in cancer progression, this further contributes to the overall metabolic heterogeneity and aggressiveness of the cancer15.

It has been shown that certain metabolites, like trimethylamine N-oxide, are upregulated in patients whose diet consists of meat, fish, and eggs as these foods enrich the gut microbiome to show an upregulation in this metabolite76. Additionally, analysis of metabolite profiles from the plasma of patients with breast cancer from the Nurses’ Health Study demonstrate many associations between metabolite subclasses and breast cancer risk, many of which could be influenced by dietary consumption77. In summary, dietary and environmental factors are critical additional elements that can substantially affect the lipidome and metabolome, potentially influencing the progression of breast cancer. It is important to acknowledge the influence of environmental and lifestyle (including dietary) factors on metabolome and lipidome within the context of analyzing -omics profiles as an additional variable for breast cancer progression.

Patient specimens for metabolomics/lipidomics profiling

Metabolomic and lipidomic profiling techniques can analyze small quantities and volumes of both solid and liquid tissue types. This flexibility means a variety of tissue sources can be used for profiling including plasma, serum, saliva, primary tumor or metastatic site biopsies (including lymph node biopsies), and urine78,79, among others. One study using saliva identified that patients with breast cancer had a distinct metabolite profile of volatile metabolites (including acetic, propanoic, and benzoic acids) that could potentially be used as a prognostic biomarker80. Another study using metabolomics of salivary samples of patients with breast cancer determined that the ratios of polyamines correlated with cancer stage in patients and increased with worsened health status81. A dried blood spot technique for analyzing amino acids and acylcarnitines identified piperamide, asparagine, proline, tetradecenoylcarnitine/palmitoylcarnitine, phenylalanine/tyrosine, and the glycine/alanine ratio as potential biomarkers for breast cancer diagnosis82.

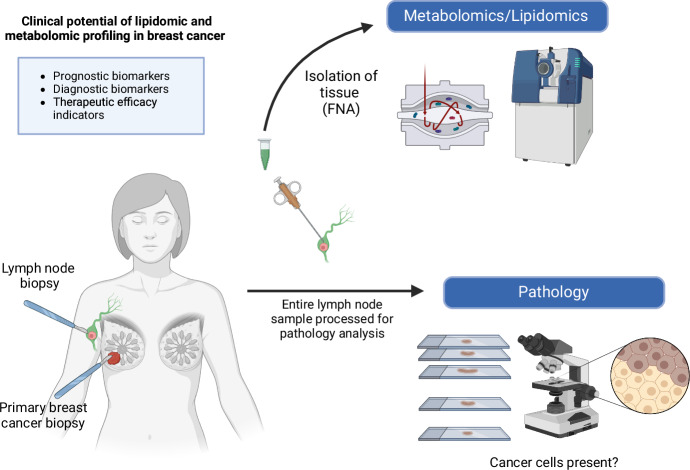

Plasma sampling enables the detection of various indicators of cancer, including circulating tumor cells, serum-based disease markers, circulating tumor DNA, and plasma DNA methylation patterns83,84. These indicators can be analyzed together with metabolomic and lipidomic profiles derived from the same plasma samples for a comprehensive understanding of breast cancer progression at a molecular-level. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies also provide sufficient sample to be able to obtain a metabolomic/lipidomic profile, and FNA techniques have been successfully applied to other -omic profilings in cancer including proteomics85. Since FNA is commonly performed on primary breast tumors and lymph node biopsies, it represents a novel sampling method that could be used to determine the metabolic and lipidomic profile of the tissues for comparison of profiles between primary tumor and progression to lymph nodes85–87 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Clinical potential of lipidomic and metabolomic profiling in breast cancer.

As fine-needle aspirations are commonly performed on primary breast tumors and lymph node biopsies, it represents a novel sampling method that could be used to determine the metabolic and lipidomic profile of the tissues for comparison of profiles between primary tumor and progression to lymph nodes. Figure generated with BioRender.com.

Benefits and challenges of lipidomics/metabolomics profiling in breast cancer

Lipidomics and metabolomics profiling offer potential benefits in breast cancer management, specifically by opening new opportunities for personalized treatments. In the context of lipidomics and metabolomics profiling for breast cancer, several types of specimens can be considered for clinical analysis. Primary tumor samples are the most direct source of metabolic information specific to the malignancy88. Lymph node samples, often obtained during staging procedures, provide critical insights into metastatic processes89. Plasma represents a highly feasible option due to its non-invasive collection and potential to reflect systemic metabolic alterations associated with breast cancer. Moreover, plasma can be longitudinally sampled over time, allowing for dynamic monitoring of disease progression and response to treatment66,81,82. Other potential sample types include urine, which offers ease of collection and potential for reflecting systemic metabolic changes, and fine-needle aspiration samples of primary tumors, lymph nodes, and larger metastases at distant sites (including liver biopsies). While each specimen type presents unique advantages and challenges, in the future routine clinical implementation will likely favor those that balance diagnostic value with practicality and patient comfort, particularly plasma and minimally invasive biopsy techniques83,84.

By discovering the unique lipid and metabolite alterations associated with an individual’s breast cancer progression, these tools have the potential to inform tailored treatment regimens that integrate with standard oncologic care, including targeted therapy and conventional treatments like chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Despite their promise, the use of lipidomic and metabolomic profiling as prognostic and diagnostic tools in breast cancer also faces technical and methodological challenges. Immediate freezing of patient samples on dry ice is imperative to preserve the integrity of the metabolome and lipidome, and plasma must be processed without delay to prevent coagulation—prerequisites that demand meticulous handling and rapid processing90–94. Temperature fluctuations can impair the integrity and overall accuracy of the sample analysis91–94. The shortcomings of these tools further include the conditions at which samples must be prepared.

Variability in metabolites due to diet, medication, gut microbiome influences that differ from patient-to-patient, as well as timing of sample collection present significant confounders for analysis necessitating careful consideration of these factors in study designs95. Diet can also influence the lipidome not only from patient-to-patient but within an individual patient as lipid composition can change based on dietary consumption. These techniques also rely on advanced instrumentation, such as high-resolution mass spectrometry, and may require collaborative efforts across multiple institutions to ensure consistency and validity of data11.

Furthermore, the heterogeneity and structural complexity of metabolites, present substantial challenges in the specific detection and analysis of metabolic alterations tied to cancer progression96. This complexity is particularly problematic in translational research involving cellular samples from patients, which exhibit significant variability, thereby complicating the application of standard metabolic methodologies. One of the most challenging aspects of lipidomic and metabolic profiling from plasma or tissue samples is the ability to differentiate between metabolites derived from immune versus cancer cells within a sample—a challenge that current and future technological advancements must address to refine metabolomics and lipidomics as diagnostic and prognostic tools in breast cancer progression. Furthermore, while lipidomic and metabolomic profiling can identify potential biomarkers, we currently lack a broad range of drugs to target these metabolic changes, underscoring the gap between biomarker discovery and therapeutic application.

Outlook

Ongoing clinical trials for metabolomic and lipidomic profiling in the identification of biomarkers have become a powerful tool for metabolic diseases. Specifically in colorectal cancer, -omic techniques have been previously utilized to identify predictive biomarkers for the prediction of colorectal cancer, thus demonstrating the feasibility of conducting such clinical trials in breast cancer12. Clinical trials in the identification of metabolomic and lipidomic biomarkers are technically feasible as low cell number input is possible and able to offer insightful and key information. Recent advancements in metabolomic/lipidomic technologies such as spatial metabolomics, single-cell metabolic profiling (scMEP)97, assessing metabolism by flow cytometry (Met-Flow), and nutrient uptake assays (QUAS-R)98, along with single-cell metabolomics and SpaceM99, have greatly improved the precision and throughput of metabolite quantification in breast cancer research100,101. As these technologies advance, they are increasingly being combined with multiomics and imaging techniques, forming an integrated approach that deepens our understanding of metabolic functions and of identifying predictive biomarkers in breast cancer progression.

Outstanding questions

Key outstanding questions in the use of lipidomics and metabolomics as potential biomarkers for breast cancer progression include:

What is the anticipated specificity and sensitivity of lipidomic and metabolomic biomarkers for breast cancer progression?

Can metabolomic and lipidomic profiles be used for the early detection of breast cancer?

What are the underlying mechanisms by which changes in the metabolome and lipidome contribute to breast cancer progression?

How do environmental and lifestyle (including dietary) factors influence the metabolome and lipidome in the context of breast cancer?

How can lipidomic and metabolomic biomarkers be used to inform treatment decisions in breast cancer?

Given the heterogeneity of breast cancer, what is the extent to which personalized versus generalizable lipidomic and metabolomic biomarkers can be used to predict disease progression in diverse patient populations?

How can lipidomic and metabolomic data be integrated with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to provide a more comprehensive understanding of breast cancer progression?

Are there dynamic changes in the lipidome and metabolome during breast cancer treatment, and can these changes predict therapeutic response or relapse?

How can advances in cell isolation techniques and mass spectrometry technology improve the accuracy, speed, ability to analyze low cell number metabolomics, ability to distinguish between cancer versus non-cancer (including immune cell) metabolomic/lipidomic profiles, and the cost-effectiveness of lipidomic and metabolomic profiling?

What are the challenges in translating metabolomic and lipidomic findings from the lab to the clinic?

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Ubellacker Lab for their helpful suggestions for this review. We are grateful for the support from the Breast Cancer Research Alliance (J.M.U.), Landry Cancer Biology Research Fellowship (A.C.), and the Ludwig Center at Harvard who have provided funding to make this review possible.

Author contributions

A.C. and J.M.U. wrote the review with input and clinical insights from S.M. and T.A.J. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin.74, 12–49 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park, M. et al. Breast cancer metastasis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 6806 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Harbeck, N. et al. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.5, 66 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng, Y. et al. Breast cancer development and progression: risk factors, cancer stem cells, signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes Dis.5, 77–106 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onitilo, A. A., Engel, J. M., Greenlee, R. T. & Mukesh, B. N. Breast cancer subtypes based on ER/PR and Her2 expression: comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival. Clin. Med. Res.7, 4–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veerla, S., Hohmann, L., Nacer, D. F., Vallon-Christersson, J. & Staaf, J. Perturbation and stability of PAM50 subtyping in population-based primary invasive breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer9, 83 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindström, L. S. et al. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J. Clin. Oncol.30, 2601–2608 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perou, C. M. et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature406, 747–752 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mapstone, M. et al. Plasma phospholipids identify antecedent memory impairment in older adults. Nat. Med.20, 415–418 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayers, J. R. et al. Elevation of circulating branched-chain amino acids is an early event in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma development. Nat. Med.20, 1193–1198 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hornburg, D. et al. Dynamic lipidome alterations associated with human health, disease and ageing. Nat. Metab.5, 1578–1594 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi, C. et al. Breast cancer in the era of integrating “Omics” approaches. Oncogenesis11, 17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun, C. et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics highlights cell-specific metabolic remodeling and interactions in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun.14, 2692 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iqbal, M. A. et al. Metabolic stratification of human breast tumors reveal subtypes of clinical and therapeutic relevance. iScience26, 108059 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demicco, M., Liu, X.-Z., Leithner, K. & Fendt, S.-M. Metabolic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat. Metab.6, 18–38 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexandrov, T. Spatial metabolomics: from a niche field towards a driver of innovation. Nat. Metab.5, 1443–1445 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roshanzamir, F., Robinson, J. L., Cook, D., Karimi-Jafari, M. H. & Nielsen, J. Metastatic triple negative breast cancer adapts its metabolism to destination tissues while retaining key metabolic signatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA119, e2205456119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elia, I. & Haigis, M. C. Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: from cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nat. Metab.3, 21–32 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffin, J. L. & Shockcor, J. P. Metabolic profiles of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer4, 551–561 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clish, C. B. Metabolomics: an emerging but powerful tool for precision medicine. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud.1, a000588 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosgrove, J. et al. A call for accessible tools to unlock single-cell immunometabolism research. Nat. Metab.6, 779–782 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Jang, M., Kim, S. S. & Lee, J. Cancer cell metabolism: implications for therapeutic targets. Exp. Mol. Med.45, e45 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boroughs, L. K. & DeBerardinis, R. J. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat. Cell Biol.17, 351–359 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyamfi, J., Kim, J. & Choi, J. Cancer as a metabolic disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 1155 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Elia, I. et al. Proline metabolism supports metastasis formation and could be inhibited to selectively target metastasizing cancer cells. Nat. Commun.8, 15267 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asiago, V. M. et al. Early detection of recurrent breast cancer using metabolite profiling. Cancer Res.70, 8309–8318 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budczies, J. et al. Remodeling of central metabolism in invasive breast cancer compared to normal breast tissue - a GC-TOFMS based metabolomics study. BMC Genomics13, 334 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jové, M. et al. A plasma metabolomic signature discloses human breast cancer. Oncotarget8, 19522–19533 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piskounova, E. et al. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature527, 186–191 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Gal, K. et al. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci. Transl. Med.7, 308re308 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris, I. S. & DeNicola, G. M. The complex interplay between antioxidants and ROS in cancer. Trends Cell Biol.30, 440–451 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cappelletti, V. et al. Metabolic footprints and molecular subtypes in breast cancer. Dis. Markers2017, 7687851 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albi, E. et al. The effect of cholesterol in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 3007–30013 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Das, C. et al. A prismatic view of the epigenetic-metabolic regulatory axis in breast cancer therapy resistance. Oncogene43, 1727–1741 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Li, W. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the association between tumor glycolysis and immune/inflammation function in breast cancer. J. Transl. Med.18, 92 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartlome, S. & Berry, C. C. Recent insights into the effects of metabolism on breast cancer cell dormancy. Br. J. Cancer127, 1385–1393 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taborda Ribas, H., Sogayar, M. C., Dolga, A. M., Winnischofer, S. M. B. & Trombetta-Lima, M. Lipid profile in breast cancer: from signaling pathways to treatment strategies. Biochimie219, 118–129 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pazaiti, A. & Fentiman, I. S. Basal phenotype breast cancer: implications for treatment and prognosis. Women’s. Health7, 181–202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, S., Li, Y., Yuan, M., Song, Q. & Liu, M. Correlation between the Warburg effect and progression of triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Oncol.12, 1060495 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flores, R. et al. Discordant breast and axillary pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol.30, 8302–8307 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ubellacker, J. M. et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature585, 113–118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reticker-Flynn, N. E. et al. Lymph node colonization induces tumor-immune tolerance to promote distant metastasis. Cell185, 1924–1942.e1923 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerjaschki, D. et al. Lipoxygenase mediates invasion of intrametastatic lymphatic vessels and propagates lymph node metastasis of human mammary carcinoma xenografts in mouse. J. Clin. Invest.121, 2000–2012 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suri, G. S., Kaur, G., Carbone, G. M. & Shinde, D. Metabolomics in oncology. Cancer Rep.6, e1795 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silva, M. E., Pupo, A. A. & Ursich, M. J. Effects of a high-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose, insulin and triglyceride levels in normal and obese subjects and in obese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res.20, 339–350 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larkin, J. R. et al. Metabolomic biomarkers in blood samples identify cancers in a mixed population of patients with nonspecific symptoms. Clin. Cancer Res.28, 1651–1661 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giskeødegård, G. F. et al. Lactate and glycine-potential MR biomarkers of prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. NMR Biomed.25, 1271–1279 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oakman, C. et al. Identification of a serum-detectable metabolomic fingerprint potentially correlated with the presence of micrometastatic disease in early breast cancer patients at varying risks of disease relapse by traditional prognostic methods. Ann. Oncol.22, 1295–1301 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luengo, A., Gui, D. Y. & Vander Heiden, M. G. Targeting metabolism for cancer therapy. Cell Chem. Biol.24, 1161–1180 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonen, N. & Assaraf, Y. G. Antifolates in cancer therapy: structure, activity and mechanisms of drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat.15, 183–210 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horn, A. & Jaiswal, J. K. Structural and signaling role of lipids in plasma membrane repair. Curr. Top. Membr.84, 67–98 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilvo, M. et al. Novel theranostic opportunities offered by characterization of altered membrane lipid metabolism in breast cancer progression. Cancer Res.71, 3236–3245 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu, Y. et al. Lipid metabolism in cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. MedComm2, 27–59 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ackerman, D. & Simon, M. C. Hypoxia, lipids, and cancer: surviving the harsh tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol.24, 472–478 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ackerman, D. et al. Triglycerides promote lipid homeostasis during hypoxic stress by balancing fatty acid saturation. Cell Rep.24, 2596–2605.e2595 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kamphorst, J. J. et al. Hypoxic and Ras-transformed cells support growth by scavenging unsaturated fatty acids from lysophospholipids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA110, 8882–8887 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu, B. et al. HIF2α-dependent lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov.5, 652–667 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young, R. M. et al. Dysregulated mTORC1 renders cells critically dependent on desaturated lipids for survival under tumor-like stress. Genes Dev.27, 1115–1131 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams, K. J. et al. An essential requirement for the SCAP/SREBP signaling axis to protect cancer cells from lipotoxicity. Cancer Res.73, 2850–2862 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snaebjornsson, M. T., Janaki-Raman, S. & Schulze, A. Greasing the wheels of the cancer machine: the role of lipid metabolism in cancer. Cell Metab.31, 62–76 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaidi, N. et al. Lipogenesis and lipolysis: the pathways exploited by the cancer cells to acquire fatty acids. Prog. Lipid Res.52, 585–589 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bathen, T. F. et al. Feasibility of MR metabolomics for immediate analysis of resection margins during breast cancer surgery. PLoS One8, e61578 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mimmi, M. C. et al. High-performance metabolic marker assessment in breast cancer tissue by mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. Lab Med.49, 317–324 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jin, H. R. et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J. Hematol. Oncol.16, 103 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu, Y. & Cao, X. Characteristics and significance of the pre-metastatic niche. Cancer Cell30, 668–681 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petan, T. Lipid droplets in cancer. Rev. Physiol. Biochem Pharm.185, 53–86 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hicks, K. C., Tyurina, Y. Y., Kagan, V. E. & Gabrilovich, D. I. Myeloid cell-derived oxidized lipids and regulation of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res.82, 187–194 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia, C., Andersen, C. J. & Blesso, C. N. The role of lipids in the regulation of immune responses. Nutrients15, 3899 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Nie, J. Z., Wang, M. T. & Nie, D. Regulations of tumor microenvironment by prostaglandins. Cancers (Basel)15, 3090 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belhaj, M. R., Lawler, N. G. & Hoffman, N. J. Metabolomics and lipidomics: expanding the molecular landscape of exercise biology. Metabolites11, 151 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Newgard, C. B. et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab.9, 311–326 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ding, M. et al. Metabolome-wide association study of the relationship between habitual physical activity and plasma metabolite levels. Am. J. Epidemiol.188, 1932–1943 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Padron-Monedero, A., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. & Lopez-Garcia, E. Dietary micronutrients intake and plasma fibrinogen levels in the general adult population. Sci. Rep.11, 3843 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smilowitz, J. T. et al. Nutritional lipidomics: molecular metabolism, analytics, and diagnostics. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.57, 1319–1335 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moholdt, T., Parr, E. B., Devlin, B. L., Giskeødegård, G. F. & Hawley, J. A. Effect of high-fat diet and morning or evening exercise on lipoprotein subfraction profiles: secondary analysis of a randomised trial. Sci. Rep.13, 4008 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rafiq, T. et al. Nutritional metabolomics and the classification of dietary biomarker candidates: a critical review. Adv. Nutr.12, 2333–2357 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Romanos-Nanclares, A. et al. Consumption of olive oil and risk of breast cancer in U.S. women: results from the Nurses’ health studies. Br. J. Cancer129, 416–425 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nam, H., Chung, B. C., Kim, Y., Lee, K. & Lee, D. Combining tissue transcriptomics and urine metabolomics for breast cancer biomarker identification. Bioinformatics25, 3151–3157 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woo, H. M. et al. Mass spectrometry based metabolomic approaches in urinary biomarker study of women’s cancers. Clin. Chim. Acta400, 63–69 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cavaco, C. et al. Screening of salivary volatiles for putative breast cancer discrimination: an exploratory study involving geographically distant populations. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.410, 4459–4468 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takayama, T. et al. Diagnostic approach to breast cancer patients based on target metabolomics in saliva by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chim. Acta452, 18–26 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang, Q. et al. A dried blood spot mass spectrometry metabolomic approach for rapid breast cancer detection. Onco Targets Ther.9, 1389–1398 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tang, Q., Cheng, J., Cao, X., Surowy, H. & Burwinkel, B. Blood-based DNA methylation as biomarker for breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin. Epigenetics8, 115 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rajkumar, T. et al. Identification and validation of plasma biomarkers for diagnosis of breast cancer in South Asian women. Sci. Rep.12, 100 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin, P. et al. Deciphering novel biomarkers of lymph node metastasis of thyroid papillary microcarcinoma using proteomic analysis of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy samples. J. Proteom.204, 103414 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sigmon, D. F. & Fatima, S. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2024).

- 87.Roskell, D. E. & Buley, I. D. Fine needle aspiration cytology in cancer diagnosis. BMJ329, 244–245 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gaude, E. & Frezza, C. Tissue-specific and convergent metabolic transformation of cancer correlates with metastatic potential and patient survival. Nat. Commun.7, 13041 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ji, H. et al. Lymph node metastasis in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms, clinical significance and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target Ther.8, 367 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnson, C. H. & Gonzalez, F. J. Challenges and opportunities of metabolomics. J. Cell Physiol.227, 2975–2981 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ulmer, C. Z. et al. A review of efforts to improve lipid stability during sample preparation and standardization efforts to ensure accuracy in the reporting of lipid measurements. Lipids56, 3–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fomenko, M. V., Yanshole, L. V. & Tsentalovich, Y. P. Stability of metabolomic content during sample preparation: blood and brain tissues. Metabolites12, 811 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Reis, G. B. et al. Stability of lipids in plasma and serum: effects of temperature-related storage conditions on the human lipidome. J. Mass Spectrom. Adv. Clin. Lab22, 34–42 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haid, M. et al. Long-term stability of human plasma metabolites during storage at −80 °C. J. Proteome Res.17, 203–211 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hong, B. V. et al. A single 36-h water-only fast vastly remodels the plasma lipidome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.10, 1251122 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim, J. & DeBerardinis, R. J. Mechanisms and implications of metabolic heterogeneity in cancer. Cell Metab.30, 434–446 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hartmann, F. J. et al. Single-cell metabolic profiling of human cytotoxic T cells. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 186–197 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ahl, P. J. et al. Met-Flow, a strategy for single-cell metabolic analysis highlights dynamic changes in immune subpopulations. Commun. Biol.3, 305 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rappez, L. et al. SpaceM reveals metabolic states of single cells. Nat. Methods18, 799–805 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schönberger, K. et al. LC-MS-based targeted metabolomics for FACS-purified rare cells. Anal. Chem.95, 4325–4334 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.DeVilbiss, A. W. et al. Metabolomic profiling of rare cell populations isolated by flow cytometry from tissues. eLife10, e61980 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lluch, A. et al. Phase III trial of adjuvant capecitabine after standard neo-/adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early triple-negative breast cancer (GEICAM/2003-11_CIBOMA/2004-01). J. Clin. Oncol.38, 203–213 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rana, R. M. et al. In silico study identified methotrexate analog as potential inhibitor of drug resistant human dihydrofolate reductase for cancer therapeutics. Molecules25, 3510 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Wu, K. H. et al. The apple polyphenol phloretin inhibits breast cancer cell migration and proliferation via inhibition of signals by type 2 glucose transporter. J. Food Drug Anal.26, 221–231 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao, Y., Butler, E. B. & Tan, M. Targeting cellular metabolism to improve cancer therapeutics. Cell Death Dis.4, e532 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tao, L. et al. Gen-27, a newly synthesized flavonoid, inhibits glycolysis and induces cell apoptosis via suppression of hexokinase II in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Pharm.125, 12–25 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dai, W. et al. By reducing hexokinase 2, resveratrol induces apoptosis in HCC cells addicted to aerobic glycolysis and inhibits tumor growth in mice. Oncotarget6, 13703–13717 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boocock, D. J. et al. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.16, 1246–1252 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mele, L. et al. A new inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase blocks pentose phosphate pathway and suppresses malignant proliferation and metastasis in vivo. Cell Death Dis.9, 572 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Le, A. et al. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress and inhibits tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 2037–2042 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhou, M. et al. Warburg effect in chemosensitivity: targeting lactate dehydrogenase-A re-sensitizes taxol-resistant cancer cells to taxol. Mol. Cancer9, 33 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Corominas-Faja, B. et al. Chemical inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase suppresses self-renewal growth of cancer stem cells. Oncotarget5, 8306–8316 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Falchook, G. et al. First-in-human study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of first-in-class fatty acid synthase inhibitor TVB-2640 alone and with a taxane in advanced tumors. EClinicalMedicine34, 100797 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Król, S. K., Kiełbus, M., Rivero-Müller, A. & Stepulak, A. Comprehensive review on betulin as a potent anticancer agent. Biomed. Res. Int.2015, 584189 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]