Abstract

The tidal reach of the Tanjiang River Basin, influenced by both runoff and tidal forces, exhibits complex and variable water levels and river flow conditions. Traditional hydrodynamic models struggle to meet the timeliness requirements for flood forecasting and early warning. Moreover, existing machine learning studies have limitations in integrating hydrological principles and explaining model applicability. This study focuses on this region, constructing a one-dimensional hydrodynamic model based on Saint-Venant’s equations to simulate flood-tide evolution. Using the model’s results, three typical machine learning surrogate models—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM)—are developed to predict the water level at the key control section of Changsha Station. The results show that the surrogate models offer advantages in both timeliness and convenience. Among them, the RF model has the highest prediction accuracy and can accurately identify key hydrological influencing factors. The LSTM model effectively captures the temporal dependencies of hydrological factors, considering the influence of historical moments on current water levels. However, the SVM model performs poorly under extreme flood-tide conditions. SHAP analysis reveals that the feature contribution values in both LSTM and RF models better align with the actual hydrology of the basin. Incorporating hydrological principles into the selection of input features helps improve model accuracy, while employing Stacking model to combine the strengths of different models further enhances prediction precision. This research provides a scientific basis and effective reference for the application of machine learning models in flood forecasting for tidal reaches, with important implications for advancing smart water conservancy construction.

Keywords: Tidal river reaches, Flood and tidal surge superposition, Machine learning, Interpretability, Stacking model

Subject terms: Hydrology, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

The construction of digital twin basins has always been a hot topic in the field of hydrology and water resources research. It is imperative and urgent to promote the construction of smart water conservancy through the establishment of professional hydrological models and the utilization of artificial intelligence technologies such as knowledge graphs and machine learning. The water level in tidal river reaches is simultaneously influenced by both runoff and tides, exhibiting interdependence, randomness, and abrupt changes in water level and channel flood capacity. Accurately forecasting water levels under such circumstances proves to be extremely challenging1–3. Many scholars both domestically and internationally have constructed numerical models based on hydrodynamic processes4–6. The river water level forecasting models, which consider the impact of tidal uplift and are based on the complete Saint-Venant equations, have been widely applied in calculating water levels in tidal river reaches7–9. However, hydrodynamic models face several pressing issues, including slow computation speed and poor timeliness. These challenges are particularly pronounced when coupled with optimization scheduling models, where the required computation time significantly increases, severely impacting the practical application of these models in flood forecasting and scheduling. Consequently, they fail to meet the urgent demand of hydrological regulatory agencies for rapidly and accurately obtaining pre-simulation results.

As the theoretical development of machine learning models continues to advance, the advantages of machine learning models in handling complex nonlinear problems are gradually becoming apparent10,11. Machine learning models known to be used in smart water management include, but are not limited to, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, decision trees, etc12–15. Using machine learning models to establish nonlinear response relationships between different indicators in time series for simulation prediction16, achieving input-output mapping. Machine learning possesses numerous advantages, including minimal requirements for input data types, reinforcement of cognition through variations in input data17, effective capture of complex nonlinear relationships, and rapid computation. These advantages significantly enhance the timeliness of flood forecasting18,19. However, machine learning faces challenges such as the requirement for large data sample sizes and lower accuracy in extreme flood forecasting. These issues make it difficult to apply in areas lacking hydrological monitoring20,21. Emerging technologies in the field of deep learning have provided new perspectives for hydrological forecasting. For example, the Transformer architecture models global dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, enabling parallel capture of nonlinear relationships between variables of different scales and types. This makes it suitable for multi-factor coupling scenarios in hydrological systems and demonstrates superior performance in predicting long-term time-series hydrological data22. However, it requires large amounts of high-quality labeled data for training, limiting its application in regions with sparse hydrological monitoring stations or data gaps (such as remote basins).

In previous related studies, some research has focused on improving traditional machine learning algorithms, such as using genetic algorithms to fine-tune model parameters or optimizing the structures of machine learning models, aiming to enhance the models’ ability to fit complex hydrological data and improve the accuracy of runoff prediction. For example, the two-dimensional hidden layer structure (Td architecture) proposed by Wang et al.23. significantly improves the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) of models like LSTM and CNN by discretizing the spatiotemporal features of hydrological data, providing a new paradigm for fusing spatiotemporal information. Other studies focus on ensemble learning models, which reduce the root mean square error (RMSE) of runoff prediction through multi-layer model stacking24, significantly enhancing the models’ simulation effects on complex hydrological processes. These methods break through the data bottlenecks of traditional machine learning by improving feature extraction mechanisms or optimizing model architectures, but their applicability in tidal river reaches has not been fully validated. Some scholars have also focused on the data preprocessing stage, using methods such as wavelet transform and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) to denoise and decompose raw hydrological data, reducing data complexity and uncertainty to provide a higher-quality data foundation for subsequent model training.

Unlike previous studies that concentrated on improving specific algorithms and leveraging particular techniques to enhance prediction performance, this research focuses on integrating hydrodynamic models with machine learning models. It conducts an in - depth analysis of their applicability and underlying learning mechanisms in flood forecasting for tidal reaches. Additionally, it explores aspects such as model interpretability and the application of fusion models.

In this study, a hydrodynamic model was used to reconstruct historical hydrological conditions and simulate various extreme scenarios. Subsequently, based on the results of the hydrodynamic model, machine learning surrogate models were developed to predict water levels at key control sections. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM) were selected as the research models. The decision-making rationale fully integrates the temporal characteristics of the rainfall-runoff process, the complexity of multi-factor interactions in the river basin, and the practical constraints of data availability. LSTM was chosen as the primary model for handling hydrological time-series data due to its gating mechanisms (forget gate, input gate, output gate), which enable explicit modeling of long-term dependencies—such as the lag effects of antecedent rainfall and downstream tidal levels on flood peaks. RF, through an ensemble of decision trees, efficiently captures the nonlinear interactions among rainfall intensity, river discharge, and tidal levels. Its inherent noise resistance and feature importance evaluation capabilities provide robustness for data-sparse scenarios in small- to medium-sized basins. SVM, leveraging kernel function mapping (e.g., Gaussian kernel), excels at precisely identifying critical hydrological conditions under small-sample constraints, mitigating the data volume dependency of deep learning models. Although the Transformer architecture offers advantages in global attention for long-sequence modeling, its requirements for large-scale datasets and high computational costs are incompatible with the dataset size of this study. In summary, the heterogeneous combination of LSTM, RF, and SVM addresses the core requirements of hydrodynamic simulation in tidal river reaches from three dimensions: temporal dynamics, feature interactions, and small-sample generalization. This approach effectively avoids the adaptability limitations of other models in this specific context25–28. This study conducts an in - depth comparative analysis of the applicability of the three models in the prediction of river channel water levels in tidal reaches, interprets the learning characteristics of each machine learning model and its learning mechanism of the internal causal relationships of hydrological factors, enhances the interpretability of machine learning models, and analyzes the reasons for the accuracy differences among different models. Thus, a more convenient, efficient, and accurate forecasting and simulation method is formed, and the response relationship between flood - control protection targets and hydrological data is clarified. On the one hand, it realizes real - time prediction and update of the Tanjiang River water level, improving the comprehensive forecasting and scheduling capabilities of the basin. On the other hand, it can provide a reference for model decision - making in subsequent studies when dealing with non - linear hydrological data, promoting the scientificity and effectiveness of the selection of machine learning models in the construction of smart water conservancy.

Research area

The Tanjiang River is a first - order tributary of the Pearl River Delta water system. Its main stream is 248 km long, with an average slope of 0.45‰, and a drainage area of 6026 km². The annual precipitation in the basin ranges from 1200 to 2000 mm, with precipitation from April to September accounting for 80% of the annual total. The water system map of the Tanjiang River Basin is shown in Fig. 1. The lower reaches of the Tanjiang River, starting from the Heshan Sluice, are a tidal area, belonging to a mixed - type irregular semi - diurnal tide. The Changsha Station is a key flood - control control section. Due to its coastal location, there are uncertainties in meteorology, tides, and typhoons. Coupled with the lack of effective management, the basin often suffers from flood disasters, causing serious losses and disasters to normal human life and production activities. It is of great significance to forecast the possibility of flood disasters in advance and formulate various flood - control measures in a timely manner to minimize the losses caused by flood disasters to downstream towns.

Fig. 1.

Schematic map of the Tanjiang River Basin.

The Tanjiang River Basin contains 22 reservoirs and 6 sluices. Subsequently, a scientific and reasonable joint dispatching model will be established. Due to the backwater effect of tides, the flood - discharge window time is extremely limited, only 6 h, which poses extremely strict requirements on the timeliness of hydrodynamic solutions. Moreover, the proportion of flood in the middle reaches of the Tanjiang River Basin is relatively large, the encounter of flood and tide is complex in time and space, the flood - carrying capacity of the river channel fluctuates with the tide, and coupled with the lack of flow monitoring data at existing stations, the lack of effective flow monitoring data has greatly increased the difficulty of flood forecasting in the Tanjiang River Basin. Currently, flood forecasting in the Tanjiang River Basin is mainly based on experience. This method has low accuracy and is difficult to apply in extreme flood - tide superposition situations. Therefore, it is urgent to establish a machine learning surrogate model, combine meteorological, rainfall, and tide level forecasts, construct an efficient flood forecasting model for the Tanjiang River Basin, quickly form feedback on measured hydrological information, and achieve accurate flood forecasting and real - time early warning for the Tanjiang River.

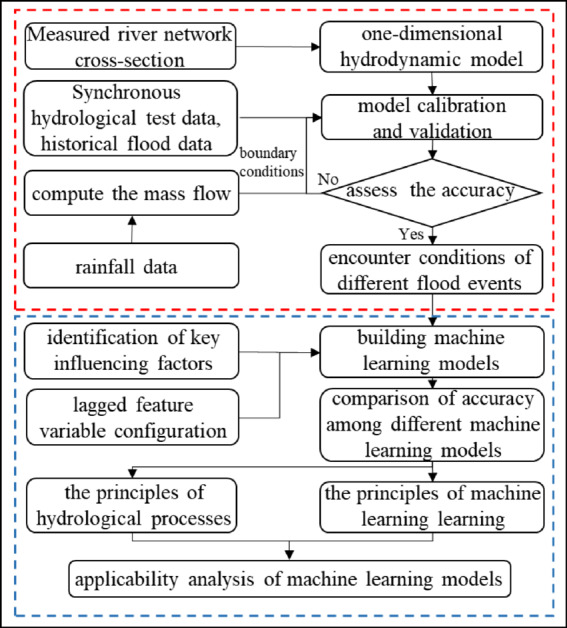

Research method

To study the flood evolution characteristics of the Tanjiang River Basin, it is necessary to establish necessary mathematical models to simulate the water state of the Tanjiang River Basin. This study establishes a one-dimensional river network hydrodynamic model to simulate the movement process of water flow in the river. The implicit finite difference scheme is used to discretize the equations for solving the Saint Venant equation. Based on the section from Heshan Sluice to Yamenkou, the flood evolution process is studied under different flood and tide combination conditions, and historical hydrological conditions are inverted. Leveraging a substantial volume of computational outcomes from the hydrodynamic model, a machine learning agent model is devised to address the nonlinear response relationship between the water level at key control sections of the Tanjiang River and downstream tide levels, upstream inflows, and interval inflows. The objective is to achieve precise water level simulation predictions for the pivotal control section of the Tanjiang River at Changsha Station. By delving into the learning mechanisms of three distinct machine learning models and their responses to hydrological processes, alongside assessing errors in model simulation results, an analysis and comparison are conducted to evaluate the applicability and underlying reasons of each model in forecasting water levels in tidal river sections. The research process diagram is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Research process diagram.

Hydrodynamic model

Model principle

The hydrodynamic model is based on the one-dimensional unsteady flow equations of open channels, with its theoretical foundation rooted in the Saint-Venant equations, which comprise the continuity equation and the momentum equation.

(1)Continuity equation:

| 1 |

(2)Momentum equation:

| 2 |

Where, Q: River section discharge (m3/s). x: Distance along the flow direction (m). t: Time (s). A: Cross-sectional area of flow (m2). Z: Water level (m). q: Lateral inflow per unit length of river segment (including uniform lateral inflow and concentrated lateral inflow) (m3/s). 𝛼: Momentum correction coefficient. K: Flow modulus. g: Gravitational acceleration (m/s2).

The Saint-Venant equations are discretized using the 6-point Abbott-Ionescu implicit finite difference scheme. The discretization is performed in an alternating manner, following the sequence of water level-flow-water level, to construct the computational grid. Additionally.

Model construction

The study focuses on flood prediction in the tidal reach of the Tanjiang River basin, using the discharge from Heshan Watergate as the upper boundary condition for the hydrodynamic model and the water level at Guanchong as the downstream boundary condition. The research scope covers the downstream area of the Tanjiang River, from Heshan Watergate to Yamenkou, including seven main tributaries: Xiangang, Baisha, Zhenhai, Xinchang, Gongyi, Xinqiao, and Zhishan River, as well as 19 other tributaries, totaling 27 rivers. The total length of the rivers is 514.6 km, with the main stream of the Tanjiang River accounting for 106.4 km.

In the one-dimensional hydrodynamic model, the physical characteristics of the river, such as width, bottom elevation, and slope, are simulated through river cross-sections. In this study, the river cross-sections were generalized using measured river topographic data, resulting in 423 generalized cross-sections. Among them, there are 154 generalized cross-sections for the main stream of the Tanjiang River and 269 for other tributaries. The schematic diagram of the river network model is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of the generalized river network model.

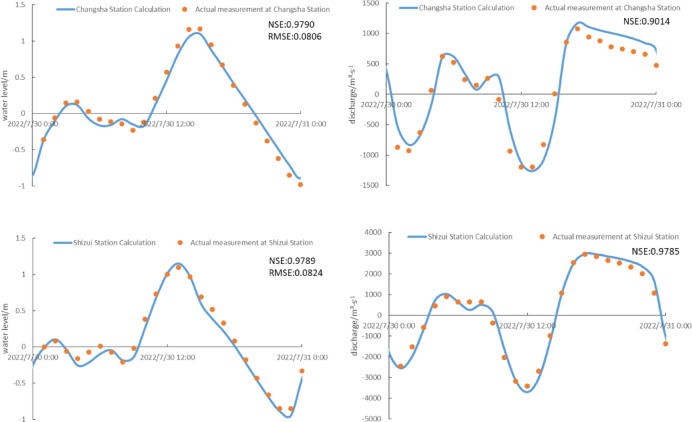

Model calibration and validation

The parameters of the hydrodynamic model mainly consist of the Manning’s roughness coefficient n for the riverbed. Synchronous hydrological test data from July 29 th, 2022 to July 31 st, 2022 in the Tanjiang River basin were collected. The Manning’s roughness coefficient n was calibrated and set for different river sections, with Changsha Station and Shizui Station serving as reference data for model calibration and validation. The calibration results for the roughness coefficient show a gradual decrease from 0.032 at the upstream section of the main stream to 0.015 at the downstream end section. For the tributary rivers, the roughness coefficient is uniformly set at 0.032. As shown in Fig. 4, the calibration results of the model show that the Nash coefficients for water level are all above 0.96, and the Nash coefficients for flow rate are all above 0.9, indicating a good overall validation performance. Based on this model, the flood evolution in the Tanjiang River basin can be studied effectively.

Fig. 4.

Validation of water level and flow rate during synchronous hydrological tests.

Using the hydrodynamic model, the hydrological processes during the dragon boat water period from June 5, 2018, to June 8, 2018, in the Tanjiang River basin were simulated. As shown in Fig. 5, the verification results indicate that the Nash coefficients for water level all exceeded 0.94, demonstrating a satisfactory simulation performance. This model can be utilized for further studies on flood evolution within the Tanjiang River basin.

Fig. 5.

Water level verification during dragon boat water.

Machine learning agent model

Based on the validated hydrodynamic model, simulations were conducted for the stretch from Heshan Watergate to Yamenkou, exploring the flood evolution process under different flood and tide combination scenarios. The scheme combinations are presented in Table 1 below. Due to the maximum designed discharge of 4972 m3/s at the upstream control node Heshan Watergate, the magnitude of upstream discharge was set from 0 to 5000 m3/s, with increments of 100 m3/s. Similarly, the interval inflow was set at levels ranging from 0 to 5000 m3/s, with increments of 100 m3/s. For the downstream tide levels, based on multi-year tidal frequency analysis, typical tide processes containing heights such as 1.77 m (average high tide level), 2.05 m (5-year high tide level), and typhoon storm tide of 2.39 m (100-year high tide level) were selected.

Table 1.

Hydrodynamic model boundary condition schemes.

| Scheme | Downstream tide level/(m) | Upstream discharge magnitude/(m3/s) | Interval inflow magnitude/(m3/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.77/2.05/2.39 | 0–5000 | / |

| 2 | 1.77/2.05/2.39 | / | 0–5000 |

| 3 | 1.77/2.05/2.39 | 0–5000 | 0–5000 |

Through hydrodynamic model calculations, 125 floods were simulated, with each flood lasting 48 h, resulting in a total of 6,000 sets of calculation results. Based on these 6,000 sets of data, a training set was formed to construct three machine learning surrogate models, namely LSTM, RF, and SVM, to solve the non - linear response relationship between the water level at the key control section of the Tanjiang River, the downstream tide level, the upstream incoming water, and the interval inflow, and to simulate and predict the water level at Changsha Station.

Through the study of the hydrodynamic simulation results and the existing hydrological data of the Tanjiang River Basin, it is found that the influence of 19 tributaries and other factors on the water level at Changsha Station is relatively small or their influence can be indirectly reflected through other variables. Among the 11 hydrological characteristic variables finally selected, the tide level at Guanchong is one of the key factors, which directly reflects the impact of downstream tides on the study area. The discharge flow under the Heshan Sluice represents the main part of the upstream incoming water and plays an important role in the water level change at Changsha Station. The inflows from Zhenhai River, Xiangang River, Baisha River, Xinchang River, Gongyi River, Xinqiao River, Zhishan River, etc. During the flood evolution process in the basin, the inflow of these tributaries will significantly change the water balance of the river channel, thus affecting the water level at Changsha Station. The discharges of Dashahe Reservoir and Zhenhai Reservoir are non - negligible factors during floods. According to the calculation results of the hydrodynamic model and synchronous hydrological measurements, it takes about three hours for the tide to travel upstream from Guanchong Station in the lower reaches to Changsha Station. Introducing the delay characteristic of the Guanchong tide level can better reflect the time lag of the hydrological process and help improve the model accuracy.

Based on the above analysis, a total of 11 hydrological characteristics that have a significant impact on the water level at Changsha Station, including the Guanchong tide level, the discharge flow under the Heshan Sluice, the inflows of Zhenhai River, Xiangang River, Baisha River, Xinchang River, Gongyi River, Xinqiao River, Zhishan River, the discharges of Dashahe Reservoir and Zhenhai Reservoir, are used as the input variables for machine learning, with the water level at Changsha Station as the output target. Then, three machine learning surrogate models, LSTM, RF, and SVM, are constructed to solve the non - linear response relationship between the water level at the key control section of the Tanjiang River, the downstream tide level, the upstream incoming water, and the interval inflow, and to simulate and predict the water level at Changsha Station.

LSTM model

The Long Short - Term Memory (LSTM) model, abbreviated as LSTM, is a typical gate - controlled recurrent neural network. It can effectively tackle the problems of gradient explosion or gradient vanishing that occur during the training of simple recurrent neural networks. It is characterized by a gating structure that incorporates a Forget Gate (ft), an Input Gate (It), and an Output Gate (Ot).

LSTM realizes feature extraction and the modeling of temporal dependencies through its gating mechanism and recurrent connections. By integrating the current input with the previous hidden state, it establishes temporal dependencies, taking into account the influence of historical data during the prediction process. In the training process, hydrological and meteorological variable data are first taken as the input sequence, and the corresponding river channel water - level data are used as the target sequence, which are then input into the LSTM network. Subsequently, the predicted output of the model is calculated by means of the forward - propagation algorithm. Next, the loss between the predicted value and the true value is computed, using the mean - squared error loss function. The back - propagation algorithm is utilized to calculate the gradients of the loss function with respect to the model’s parameter weights and biases. Optimization algorithms such as gradient descent are employed to update the parameters so as to minimize the loss function. Through the coordinated operation of the forget gate and the input gate, the LSTM model can automatically learn and identify which information is significant, will affect the target variable (water level), and needs to be retained in the cell state, and which information can be forgotten. The LSTM model implemented based on the Python and Keras frameworks selects the mean - squared error as the loss function and Adam as the optimizer, with a learning rate of 0.001. Two hyperparameter optimization methods, namely the trial - and - error method and Bayesian optimization, are used to adjust the LSTM hyperparameters. The final parameters are set as follows: the number of hidden layers is 2, the number of neurons in each layer is 64, and the number of iterations is 50. To prevent overfitting, the dropout parameter is set to 0.2, and the L2 regularization parameter is set at 0.01.

RF model

Random Forest (RF) is hailed as a method that represents the level of ensemble learning technology. In a typical Random Forest model, when the number of decision trees generated does not reach the set quantity, the model will continue to generate and save new decision trees.

Random Forest (RF) is regarded as a representative method of ensemble learning techniques. In a typical Random Forest model, if the number of generated decision trees has not reached the preset quantity, the model will continue generating and saving new decision trees. Hydrological, meteorological, and other variables are used as input features, with water level as the target variable to construct the training set. Decision trees are built by randomly selecting subsets of training data and feature subsets through Bootstrap sampling. For each decision tree, the CART algorithm is used, recursively splitting the data into subsets with the least impurity to form the tree structure. The splitting process is determined based on the feature variable values, with the objective of minimizing the prediction error of water levels. The process of dividing the dataset involves gradually learning the relationship between features and the target variable. By selecting optimal splitting features and points, the consistency within the subsets is increased, which better reflects the relationship between hydrological, meteorological features and the target water level. Each tree makes predictions on the test data, outputting a water level prediction. The final ensemble prediction result is obtained by averaging the predictions from all the trees. The Random Forest Regressor class in the scikit-learn library is used to create the Random Forest regression model. Through automatic parameter tuning, the number of trees is set to 50, the maximum depth of decision trees is set to 10, the minimum number of samples required to split a node is 3, the minimum number of samples required for a leaf node is 1, and the mean squared error is used as the criterion to evaluate the quality of node splits.

SVM model

Support Vector Machine (SVM) was introduced by Corinna Cortes et al. (1995). SVM handles non-linear problems by implicitly mapping non-linear vectors into a high-dimensional space using kernel functions, transforming the problem into a linearly separable one in the high-dimensional space. A training set containing hydrological, meteorological variables and corresponding water level data at control sections is prepared. Hydrological and meteorological variables are used as input features, and the water level at Changsha Station is set as the target variable. A kernel function is used to map the data into a high-dimensional feature space for better fitting. The Huber loss function is used to minimize the error between the target values and the model predictions. By solving the constrained optimization problem, an optimal hyperplane is found that best fits the training data while keeping the error as small as possible, thus minimizing the discrepancy between predicted and actual water levels. The SVM regression model is implemented using the scikit-learn library in Python, employing a radial basis kernel function, with the regularization parameter C set to 1, and the epsilon-insensitive loss function set to 0.01. The remaining parameters are set to their default values.

Bayesian linear regression model

In this study, the Bayesian Linear Regression model is also introduced for comparative analysis to comprehensively explore the performance of different models in predicting water levels in the tidal reach. Bayesian Linear Regression is a method based on Bayesian statistical theory, incorporating the concept of prior distributions into traditional linear regression, fully accounting for the uncertainty of model parameters. The basic assumption is that the response variable (water level at Changsha Station in this study) has a linear relationship with a set of input feature variables (such as tidal levels at Guancong Station, upstream discharge, and inflows from different sections) and includes a random error term. Under the Bayesian framework, prior distributions are assigned to the regression coefficients and the variance of the error term, typically assuming the regression coefficients follow a multivariate normal distribution and the error term variance follows an inverse gamma distribution. Given the observed data and corresponding response variables, the posterior distribution is calculated using Bayes’ theorem. In this study, the Python language is used to construct the Bayesian regression model via the BayesianRidge class in sklearn.linear_model, which internally implements the logic for prior value setting and posterior distribution calculation based on a specific algorithm. During the training process, the model continuously updates its estimates of the model parameters based on the input data and the set prior distribution, until certain convergence criteria are met. The iteration count parameter niter for BayesianRidge is set to 300. The parameters α1 and α2 are set to 1e-6, determining the shape of the prior distribution (gamma distribution) for the regression coefficients. λ1 and λ2 are set to 1e-6, determining the prior distribution for the noise precision (related to the variance of the error term). The fit_intercept parameter is set to True. The Normalize parameter is set to False, meaning the input features will not be automatically normalized. Manual normalization is performed during the data preprocessing stage.

Feature importance analysis method

Compared to traditional mechanism models, machine learning models are often considered data-driven “black box” or “gray box” models, typically unable to directly explain the mechanistic reasons behind changes in model outputs. However, in recent years, some interpretable machine learning models and techniques have been widely applied, such as feature importance evaluation in Random Forest (RF) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations). These techniques can provide explanations for the decision-making process of models, making the application of machine learning models in hydrological forecasting not only highly accurate but also providing a certain degree of interpretability.

Compared to LSTM and SVM models, RF can directly perform feature importance analysis. By observing the reduction in impurity each feature contributes when splitting nodes, the average impurity reduction for each feature across all decision trees is calculated. Features with larger average impurity reduction are considered more important.

The Shapley value theory originates from game theory and was first proposed by Lloyd Shapley in 1953. It is a method used to distribute the payoffs among participants in cooperative games. The Shapley value fairly distributes each participant’s contribution to the cooperative payoff by considering all possible permutations of participants. This concept is widely used to explain the outputs of machine learning models because it provides a consistent and fair method for evaluating the impact of each feature on the prediction results. The calculation formula is as follows: Suppose we have a cooperative game with n participants, denoted as set N={1,2,…,n}. For each subset  , the characteristic function

, the characteristic function  represents the total payoff of subset

represents the total payoff of subset  .

.

| 3 |

where  indicates that

indicates that  is a subset of N excluding

is a subset of N excluding  ;

;  represents the size of subset

represents the size of subset  ;

;  represents the total payoff of subset

represents the total payoff of subset  ;

;  represents the total payoff after adding

represents the total payoff after adding  to subset

to subset  ;

;  is the number of permutations of subset

is the number of permutations of subset  ;

;  is the number of permutations of the remaining participants after excluding subset

is the number of permutations of the remaining participants after excluding subset  and participant

and participant  ;

;  is the number of permutations of all participants.

is the number of permutations of all participants.

Results and discussion

Feature importance

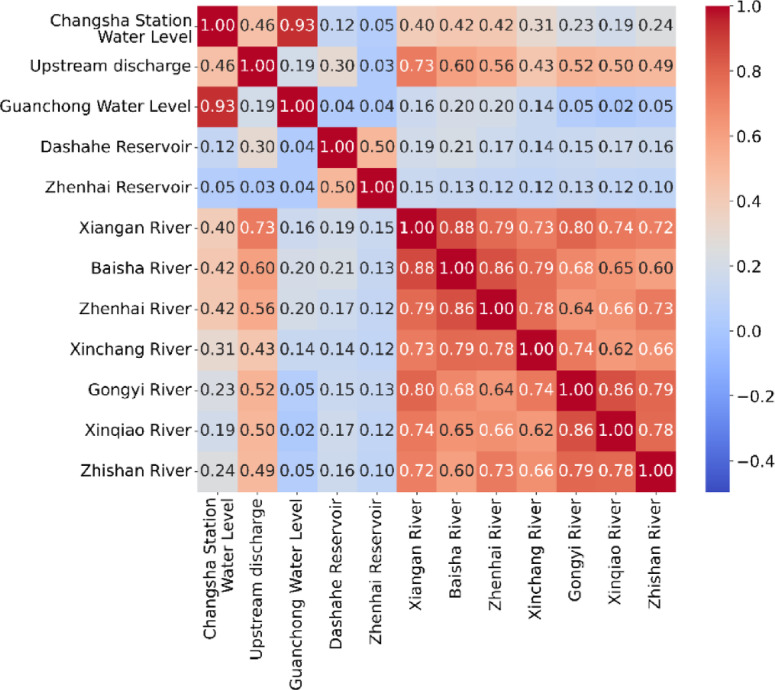

Correlation analysis

Compared to traditional mechanistic models, machine learning models are data-driven “black-box” or “gray-box” models, unable to provide explicit explanations for the underlying mechanisms behind changes in output. Through correlation analysis, the influence of each input factor on the simulation results of machine learning models can be quantified, thereby identifying important input factors. Using correlation analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficients between each boundary condition and the water level at the control section Changsha Station are calculated to measure the strength and direction of their linear relationships. The correlation between each boundary input and the water level at Changsha Station is shown in Fig. 6 below. The results indicate that the downstream tide level has the greatest impact on Changsha Station, with a correlation coefficient of 0.93, showing a strong positive correlation. The upstream discharge flow, Baisha water, Xiangang water, and Zhenhai water also have a significant impact on Changsha Station. This result is generally consistent with the results of hydraulic model calculations and existing hydrological laws in the Tanjiang River Basin.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of input variable correlation.

Analysis of the importance of RF features

Compared to LSTM and SVM models, RF can directly perform feature importance analysis. By observing the decrease in impurity brought by each feature at node splitting, the average decrease in impurity of each feature in all decision trees is calculated. Features with larger average impurity reduction are considered more important. In the model, the Feature Importance command is used to analyze the feature importance of each input variable, and the results are shown in the Fig. 7 below. The tide level at Guanchong three hours ago is the most important feature, while upstream discharge, Zhenhai water, Baisha water, and Xiangang water inflow are also important. The feature importance analysis results of the random forest model are basically consistent with the results of variable correlation analysis, and they conform to the hydrological cognition of the basin, indicating that the random forest can well understand the intrinsic causal relationships between input hydrological features.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of feature importance in RF model.

Shapley value calculation for machine learning models

Using the SHAP method, we calculated the Shapley values for the LSTM, RF, and SVM models to analyze the contribution of each feature variable to the results, thereby explaining the model’s rationality. The calculation results are shown in the Fig. 8 below. The Shapley values for the RF model are largely consistent with the Feature Importance and correlation analysis results of the variables. The water level at Guan Chong three hours earlier contributes the most to the results. The inflows from upstream discharge, Zhenhai water, Baisha water, and Xiangang water are also significant, aligning with hydrological knowledge of the basin. This further indicates that the Random Forest model can well understand the inherent causal relationships among the input hydrological features.

Fig. 8.

Shapley value calculation for machine learning models.

The feature contributions in the LSTM model are similar to those in the RF model, with a significant contribution from Xiangang water, which also aligns with the hydrological relationships. However, the contributions in the SVM model differ significantly from those in the RF and LSTM models. The contribution of Zhenhai water is relatively small, which does not match the actual conditions of the basin. Nevertheless, the water level at Guan Chong three hours earlier, upstream discharge, Zhenhai water, Baisha water, and Xiangang water remain the five major influential feature variables.

Comparison of various machine learning models

Lag feature configuration

Based on the results of the hydraulic model and synchronous hydrological measurements, it was found that it takes about three hours for the tide from the downstream Guanchong Station to propagate to the Changsha Station. Now, the tide level at Guanchong is lagged and introduced as delayed features. Delayed features are introduced with lags of 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and 4 h. The accuracy of the models under different delayed features was tested using data from Typhoon Mangkhut in 2018. The comparison results of Nash coefficients corresponding to different delayed features for each model are shown in Fig. 9 below.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of NSE accuracy for different delayed features.

All three models performed best when the tide level at Guanchong was lagged by 3 h, which is consistent with the propagation time of the downstream tide calculated by the hydraulic model and observed in measurements. This indicates that all three proxy models can capture certain physical significance. The LSTM model is most sensitive to the setting of delayed features. There is a significant difference in accuracy among different lag sequences, indicating that the LSTM model has a strong ability to capture the dependency relationship of floods and tides in the time series, but it is sensitive to the time series and requires reasonable lag sequences. The RF model performed well under various delayed features, indicating that RF has lower requirements for the temporal precision of lag sequences compared to LSTM. However, when the lag time is set to 3 h, the accuracy of the RF model also significantly improved, indicating that when accurate feature variables given by hydrological processes are combined, it can improve the learning accuracy of the RF model. The SVM model performed poorly under various delayed features, indicating that the setting of lag variables cannot solve the problem of poor simulation accuracy of the SVM model in the case of flood and tide superposition.

Model error comparison

Using hydrodynamic model calculation data as training samples for machine learning, the periods from June 5 to 8, 2018 (Dragon Boat Water) and from September 15 to 17, 2018 (Typhoon Mangkhut) were selected as test sets to simulate the water levels at Changsha Station during these flood-tide events. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 10. The root mean square error (RMSE), Nash coefficient (NSE), and correlation coefficient (CC) for each model’s simulation results were calculated, and a Taylor diagram was created, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Fig. 10.

Model validation comparison.

Fig. 11.

Model error comparison.

From the calculation results and error comparison, it is evident that the LSTM and RF machine learning models meet the accuracy requirements, with Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) values exceeding 0.9. Additionally, the peak shapes of the water level simulation process are generally good, accurately capturing the variations in water levels at Changsha Station under the overlay of flood tides. Among them, the RF model performs the best in both forecasting periods. On the other hand, while the SVM model performs well under normal conditions, it exhibits poorer performance during extreme flood events, showing significant deviations in peak water level and peak time.

Model complexity impact

In the model analysis process, a deeper investigation into the bias-variance tradeoff caused by model complexity is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of model performance. For the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model, experiments were conducted with different numbers of hidden layers and neurons. The number of hidden layers was set to 1, 2, and 3, respectively, while keeping other hyperparameters unchanged. During the training process, the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) on both the training and testing sets were recorded. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of LSTM model with different numbers of layers.

| Layers | Training RMSE | Training NSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing NSE |

Training time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1080 | 0.971 | 0.4159 | 0.749 | 155 |

| 2 | 0.0911 | 0.978 | 0.2068 | 0.924 | 218 |

| 3 | 0.0811 | 0.983 | 0.3177 | 0.878 | 302 |

When the number of hidden layers was set to 1, the NSE remained around 0.749. This indicates that with such a simple setup, although the model could learn certain data patterns quickly, its low complexity led to underfitting, limiting its prediction accuracy for water level changes. It also showed significant deviations when faced with complex flood-tide scenarios. As the number of hidden layers increased to 3, the RMSE and NSE continued to decrease on the training set, but the RMSE on the testing set increased, and the NSE dropped to around 0.878. This indicates that the model experienced overfitting. The overly complex model structure caused the model to excessively learn the noise and details from the training data, reducing its generalization ability on new data and increasing variance.

For the Random Forest (RF) model, experiments were conducted by varying the number of decision trees, with the number of trees set to 20, 50, and 100, respectively. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of RF model with different numbers of trees.

| Trees | Training RMSE | Training NSE |

Testing RMSE |

Testing NSE |

Training time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.1002 | 0.9722 | 0.2981 | 0.8832 | 350 |

| 50 | 0.0897 | 0.9765 | 0.1911 | 0.9438 | 3100 |

| 100 | 0.0801 | 0.9828 | 0.1917 | 0.9431 | 4 |

As the number of trees increased to 100, although performance on the training set improved, the performance on the testing set declined, indicating that too many decision trees increased the model’s variance, affecting its accuracy and stability.

Comparison with other models

There is a significant difference in solving speed between hydrodynamic models and machine learning models. While hydrodynamic models can accurately describe the physical processes of water flow, they have a high computational complexity, especially when handling long time series and multiple working conditions, requiring a substantial amount of computational resources and time. In contrast, machine learning models have a clear advantage in solving speed. For instance, after training is complete, a machine learning model can generate a prediction for 72 h in less than 1 s, making it much faster than a hydrodynamic model, which takes about 5 min to solve. Although training machine learning models requires some time and computational resources, their prediction speed is much faster than that of hydrodynamic models, which supports their widespread use in practical applications.

In this study, in addition to the analysis of LSTM, RF, and SVM models, a Bayesian Linear Regression model was also introduced for comparison to more comprehensively evaluate the performance of different models in tidal river reach water level prediction. The results showed that the Bayesian model had some limitations, as seen in Fig. 12. While it could capture some data trends and achieved good simulation performance in normal conditions, it showed lower prediction accuracy compared to LSTM and RF models when faced with complex non-linear flood-tide interactions. Especially during extreme flood-tide events, such as typhoon storm surges, the predictions of the Bayesian model deviated significantly, likely due to its weaker ability to handle extreme values and complex multivariate interactions.

Fig. 12.

Bayesian linear regression model results.

In summary, although the hydrodynamic model performs excellently in accurately describing the physical process of water flow, its slow solution speed makes it difficult to meet the requirements of real-time water level prediction and rapid decision-making. Moreover, simple linear regression models, when faced with the complex phenomenon of extreme flood - tide superposition, are unable to effectively capture the non-linear relationships and complex dynamic changes in hydrological data. As a result, their accuracy is significantly insufficient, making it difficult to provide reliable prediction results.

Therefore, in the field of water level prediction in tidal reaches, considering key factors such as accuracy and solution speed, machine learning models are necessary. They provide a more effective solution for improving the accuracy and timeliness of flood forecasting, which is of crucial significance for ensuring the safety of river basins and the scientific management of water resources.

Model improvement

Traditional standalone machine learning models often face limitations when dealing with complex flood data, as they struggle to fully extract potential information, thereby affecting predictive accuracy. To address this issue and improve flood forecasting precision, advanced model ensemble techniques have been considered. Among these, the Stacking model, an effective ensemble method, has garnered significant attention in the field of machine learning in recent years. This model combines multiple base learners and utilizes a meta-learner to learn from the outputs of the base learners, leveraging the strengths of multiple models to enhance overall predictive performance.

The superiority of Stacking stems from its unique two-level modeling mechanism. The underlying base learners, LSTM and RF, extract features from different perspectives: LSTM captures long-term dependencies and dynamic changes in time series through its gating mechanisms, excelling at modeling the inertial propagation of water levels along the time axis and tidal cycle characteristics. RF, through integrated decision trees, mines nonlinear interactions among multivariate variables, focusing on “causal relationships in the feature space” (such as the superposition effect of multi-source inflows), and has strong robustness to complex relationships like runoff and tidal backwater. Parallel modeling by the two achieves heterogeneous feature complementarity of “temporal dynamics and causal relationships.” The top-layer meta-learner XGBoost dynamically fits the prediction residuals of the base learners through gradient boosting algorithms, performing nonlinear corrections for LSTM’s inertial bias in extreme events and RF’s regularization bias in rare patterns. This mechanism not only suppresses the variance of single models through ensemble averaging but also reduces systematic bias through residual iteration, significantly improving the ability to capture complex hydrological processes (such as flood-tide coupling abrupt changes) in water level prediction of tidal rivers and achieving dual optimization of prediction accuracy.

For LSTM: 2 hidden layers are used, with 64 neurons in each layer. The Tanh activation function is adopted to match the continuous value characteristics of water level data. Dropout rate of 0.2 and L2 regularization parameter of 0.01 are introduced between layers to suppress overfitting. The Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001) and mean squared error (MSE) loss function are used, with 50 iterations (early termination after validation set loss stabilizes via early stopping). For RF: 50 decision trees are constructed through Bootstrap sampling and random feature selection, with a maximum depth of 10, a minimum sample size of 3 for node splitting, and a minimum sample size of 1 for leaf nodes. Mean squared error (MSE) is used as the node splitting criterion to ensure minimum water level prediction error at each split point. Each tree randomly selects 4 features (50% of the total 8 input features) for splitting to enhance model diversity. The core role of the meta-learner is to fit the prediction residuals of the base learners. Its parameters are finely tuned via Bayesian optimization and early stopping: learning rate 0.1, maximum depth 5, subsampling ratio 0.8, L2 regularization parameter 0.1. The input is the prediction values of LSTM and RF on the validation set, and the output is the final fused predicted water level. Distributed gradient boosting is used, with the validation set MSE as the stopping criterion. Training terminates when the validation error does not decrease for 10 consecutive rounds, and the final iteration count stabilizes at 120 rounds to ensure the optimal balance between bias and variance.

The final prediction results of the stacking model are shown in Fig. 13. The results indicate that the stacking model significantly improves the prediction accuracy of machine learning models, with more precise predictions of flood peak water levels and peak times. Compared with single models, the RMSE of the Stacking model is reduced by 13.58% and 6.49% compared to LSTM and RF, respectively, and the NSE is improved by 4.64% and 2.68%, demonstrating its significantly enhanced ability to capture extreme flood events.

Fig. 13.

Stacking model simulation results.

To comprehensively evaluate the model fusion effect, this study selects three mainstream methods—Simple Averaging, Weighted Averaging, and Blending fusion—as comparisons with Stacking, with specific implementations as follows. Simple averaging fusion performs equal-weight averaging of the prediction results of the base learners (LSTM, RF). Weighted averaging fusion assigns weights based on the performance of the base learners on the validation set, with weights calculated as 0.4 for LSTM and 0.6 for RF (normalized by the reciprocal of RMSE). Blending fusion divides the training set into two parts: the first part trains the base learners, and the second part generates prediction values as input features for the meta-learner (linear regression). During testing, the prediction values of the base learners on the full training set are input into the meta-learner. The training set is divided into training-validation subsets at a 7:3 ratio; LSTM and RF are trained on the training subset, and prediction values are generated on the validation subset as features; linear regression is trained as the meta-learner using the true values of the validation subset as labels. The comparison of different fusion effects is shown in Table 4. The Stacking model achieves the highest NSE improvement, the smallest RMSE, and the optimal optimization effect.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different fusion models.

| Model | NSE | RMSE/(m) |

|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.9243 | 0.2068 |

| RF | 0.9438 | 0.1911 |

| Simple averaging | 0.9340 | 0.1990 |

| Weighted averaging | 0.9405 | 0.1850 |

| Blending | 0.9552 | 0.1811 |

| Stacking | 0.9672 | 0.1787 |

Discussion

The prediction of tide-flood superimposed water levels, as an important research direction in the fields of hydrology and hydrodynamics, is characterized by complex multi-factor coupling. This paper compares three typical machine learning models—LSTM, RF, and SVM—analyzing the applicability and limitations of surrogate models in flood forecasting in tidal river sections. It delves into the performance differences of various machine learning models in tidal river water level prediction and explores the underlying reasons. The paper systematically analyzes the comprehensive effects of model complexity, feature variables, and other factors on the results, achieving better predictive performance through model fusion techniques. Additionally, it makes positive attempts to enhance model interpretability, which has significant implications for improving the accuracy and reliability of flood forecasting in tidal river sections.

The complexity of models is a key issue that must be balanced in both scientific research and practical applications. In this study, the LSTM model, with its powerful ability to model time-series data, is capable of capturing dynamic nonlinear processes in the watershed, demonstrating good prediction performance. However, its complex structure and high sensitivity to hyperparameters limit its widespread use in real-time flood forecasting. On the other hand, the RF model, with its lower computational cost and good interpretability of feature variables, shows significant advantages in tide-flood superposition scenarios. In comparison, the SVM model, while capable of nonlinear feature mapping, performs poorly when dealing with extreme tide-flood events, failing to adapt to the complex interactions of multiple variables. The linear regression model may provide sufficient prediction accuracy under certain conditions, suggesting that when choosing a surrogate model, the necessity of complex models should be clarified based on research objectives to avoid unnecessary computational complexity.

Extreme scenarios such as typhoon storm surges or abnormal floods are often the key and difficult points in flood forecasting. This study shows that the RF model exhibits good robustness under extreme flood - tide superposition conditions. Through the analysis of feature importance, it can capture the influence of key hydrological variables. However, due to its strong dependence on lag features, the LSTM model requires more precise setting of delay features to achieve optimal performance. The SVM model, on the other hand, shows significant deviation in the peak simulation of extreme events, reflecting its insufficiency in handling abnormal features. The Stacking model combines the advantages of LSTM and RF, and further optimizes the prediction performance through the XGBoost meta - learner. This phenomenon indicates that in areas with limited data or frequent extreme events, the model should make full use of the calculation results of physical models or data augmentation techniques to enhance its adaptability to extreme scenarios. In addition, methods of model integration should be explored to combine the advantages of multiple models and strengthen the overall prediction ability for extreme scenarios.

Scientific interpretability is a critical indicator for the practical application of surrogate models. This study employs SHAP value analysis to clearly demonstrate the contribution of each characteristic variable to the results. For example, it identifies the importance of key factors such as the water level at Guanchong three hours prior and upstream discharge in water level prediction, with their importance ranking highly consistent with the actual hydrological mechanisms of the basin. The high contribution of the Guanchong section’s water level three hours prior essentially reflects the phase lag characteristics of flood propagation in tidal river reaches. Influenced by the bidirectional interaction between runoff and tides, the measured tidal wave propagation time is approximately 3 h, fully consistent with the flood evolution time simulated by the numerical solution of the Saint-Venant equations. The high contributions of upstream Heshan sluice discharge and inflows from the Zhenhai, Baisha, and Xiangang tributaries directly reflect the multiple runoff recharge characteristics of this basin. As the main control node of the Tanjiang Basin, the Heshan sluice undertakes more than 70% of the upstream runoff regulation task, and its discharge process directly determines the flow base value of the downstream river channel. The Zhenhai, Baisha, and Xiangang, as the three main tributaries in the lower reaches of the basin, exhibit a superposition effect on river water levels through changes in their inflows. SHAP value ranking and hydrodynamic model simulation results show that the contribution of tide-related features is higher than that of runoff-related features, consistent with the dynamic mechanism of “tidal backwater dominance and runoff supplementation” in this river reach. This interpretive analysis not only provides a transparent decision-making basis for the model (e.g., prioritizing core features such as delayed water levels and sluice-controlled discharges in variable selection) but also proves the effective mapping of data-driven models to complex hydrological mechanisms through cross-validation with physical models.

Previous studies have mostly focused on the application of the model algorithms themselves, with insufficient integration of hydrological principles into the model construction and training stages. This study closely integrates the computational results of hydrodynamic models and the hydrological characteristics of the Tanjiang River basin. In determining the input feature variables, it fully considers factors such as flood-tide propagation time and watershed hydrological characteristics, such as the reasonable setting of tide delay features at Guan Chong and incorporating the 11 hydrological features that significantly affect water levels at Changsha station, making the machine learning model better suited to the hydrological characteristics of tidal river sections. This approach provides the model with more practical prior knowledge, effectively improving its accuracy and reliability.

From the perspective of application prospects, the model and methods developed in this study demonstrate significant practical value. In real-time water level forecasting, the proxy model’s efficiency and convenience enable it to quickly respond to new hydrological data, providing timely support for flood forecasting. In data-scarce regions, the proxy model reduces data dependency by leveraging hydrodynamic simulations. In integrated watershed management, the model can be incorporated into decision support systems, coupled with scheduling models, and assist in formulating flood management strategies. However, several potential challenges remain in practical applications. For instance, climate change may alter the hydrological patterns of watersheds, necessitating continuous updates and adaptations of the model to address new conditions effectively.

Although this study primarily focused on constructing and validating models for the tidal river sections in the lower reaches of the Tanjiang River Basin, the selected machine learning models possess a certain degree of generalizability. The LSTM model’s capability to handle time series and the RF model’s strength in analyzing multivariable data make them applicable to other basins with similar hydrological characteristics. However, variations in topography, climate conditions, and hydrogeological factors among different basins may affect model performance. When applying the models to other basins, it is necessary to adjust and retrain them according to the local context. This includes reselecting and optimizing input feature variables, fine-tuning model parameters, and adapting the training process to the specific conditions of the target region. Future research could involve conducting cross-basin comparative experiments to more comprehensively assess the generalization ability of the models. Such studies would help refine their applicability to diverse hydrological scenarios and enhance their robustness in broader contexts. For cross-basin migration, parameter tuning and feature engineering are performed in response to significant differences across basins in hydrological mechanisms (e.g., runoff generation and concentration processes, tidal impacts), geographic features (e.g., topographic slope, river channel morphology), and human activities (e.g., distribution of water conservancy projects). In rapidly responsive basins (e.g., mountainous small basins with concentration time < 12 h), short-period high-frequency features are prioritized. Lag windows of 1–6 h are set, with instantaneous values (at time t) and previous 1-hour values (at t − 1) of variables such as rainfall intensity and upstream section discharge used as inputs to capture nonlinear responses in rapid runoff generation and concentration processes. In slowly responsive basins (e.g., plain tidal river reaches with concentration time > 48 h), lag feature windows are extended to 24–72 h, incorporating tidal cycle characteristics (e.g., maximum tidal level over the past 3 days, tidal range change rate) and channel storage parameters (e.g., longitudinal river width change rate, roughness spatial distribution). In reservoir-dominated basins, variables such as reservoir inflow, flood discharge dispatch commands, and water storage change rate are preferentially selected. For snowmelt-dominated basins (e.g., inland rivers in northwestern China), new features such as snow cover rate, diurnal temperature range, and permafrost depth are added, with seasonal cycle components of snowmelt runoff extracted via Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD). In basins significantly influenced by monsoons (e.g., the southeastern coast), low-frequency features such as typhoon tracks, monsoon indices, and sea-land air pressure differences are introduced. Wavelet transforms are used to separate high-frequency rainfall signals from low-frequency tidal trends, reducing data noise interference.

Conclusion

This study provides new insights and methodologies for flood forecasting in tidal river sections. By utilizing the computational results of hydrodynamic models to establish machine learning proxy models, it effectively achieves water level forecasting for tidal river sections.

In the application of machine learning models, this research explores the performance differences and underlying mechanisms of various machine learning models in water level prediction for tidal river sections. It systematically analyzes the impact of factors such as model complexity and feature variables on prediction outcomes. These findings offer valuable reference points for selecting and applying machine learning models under similarly complex hydrological conditions. The study also verifies the advantages of the RF model in predicting combined water levels from floods and tides, contributing to improved specificity and effectiveness in model applications.

However, the study has some limitations. In terms of model improvement, although the strengths and weaknesses of different models have been identified, further exploration is needed to more effectively integrate their advantages. For instance, developing new hybrid model structures or enhancing existing training algorithms could improve prediction accuracy and stability, particularly under extreme flood-tide scenarios. Explore the integration of lightweight deep learning models, such as variants of LSTM and Transformer, with parallel computing technologies to enhance real-time performance and reduce computational costs. In cross-basin application validation, while the study achieved promising results in the Tanjiang River Basin, significant differences in hydrogeological conditions and climatic characteristics across basins necessitate additional cross-basin comparative studies. Such research would help validate the generalization ability of the models and enable targeted adjustments and optimizations tailored to the characteristics of different basins.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3002704), the Guangdong Water Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. 2021-08), the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Grant No. Y523001), and the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (Grant No. 312260).

Author contributions

Z.J. wrote the manuscript. Z.J and C.L.M conceived and designed the study. H.T.F and L.H. were responsible for data collection and management. S.Y. and C.L.G guided and supervised the research. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All data, models, or codes generated or used during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. E-mail: lmchen@nhri.cn.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhao, S. C. et al. Analysis of hydrological changes in the tidal reach of Fenghua river. Jiangsu Ocean. Univ. China Nat. Sci. Ed. 30 (03), 19–24 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng, H. et al. Study on the encounter of upstream flood and estuarine tide in the tidal reach. China Yellow River. 43 (08), 44–47 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, Z. M., Qin, G. H., Chen, Z. S. & Jin, J. L. Study on the correlation between water level in the tidal reach and upstream flood and estuarine tide. China Hydraul Eng.44 (11), 1278–1285 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin, T. P., Vila-Concejo, A., Short, A. D. & Ranasinghe, R. A multi-scale conceptual model of flood-tide delta morphodynamics in micro-tidal estuaries. Geosciences8 (9), 324 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao, Z. W. Analysis of flood discharge capacity and forecasting method in the tidal reach of Yalu river. China Water Resour. Plann. Des.5, 90–93 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao, T. T. & Chen, M. X. Study on the hydrodynamic mechanism of characteristic points in the tidal reach of the lower reaches of Minjiang river. China Pearl River. 41 (11), 9–15 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv, X. S. & Shen, X. Q. Analysis of flood-tide encounter rules in the Jiao (Ling) river basin. China Hydroelectric Power. 48 (07), 13–15 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, L. L., Yang, F., Yu, S. C. & Xu, F. J. Study on storm surge flood risk simulation in the tidal river network area: taking Zhongshun Dawei as an example. China Pearl River. 39 (08), 4–8 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen, H. L. & Gao, C. Study on flood control and tide prevention scheme in tidal river reach based on MIKE11 and AHP method. China. J. China Three Gorges Univ. (Natural Sciences). 42 (01), 36–41 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, Y., Wang, C. H., Wang, N., Chen, J. B. & Xu, Q. Application of BP neural network in hydrodynamic flood forecast in tidal river reach. China Hydropower Hydropower Eng.42 (02), 21–25 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amini, A., Dolatshahi, M. & Kerachian, R. Adaptive precipitation nowcasting using deep learning and ensemble modeling. J. Hydrol.612, 128197 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, F. F., Wang, Z. Y. & Qiu, J. Long-term streamflow forecasting using artificial neural network based on preprocessing technique. J. Forecast.38 (3), 192–206 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, L. Application of machine learning methods in Huaihe River water level prediction. China. Ph.D. Thesis. Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Anhui (2022).

- 14.Zahura, F. T. et al. Training machine learning surrogate models from a high-fidelity physics-based model: application for real-time street-scale flood prediction in an urban coastal community. Water Resour. Research56(10) (2020).

- 15.Ritter, A. & Muñoz-Carpena, R. Performance evaluation of hydrological models: statistical significance for reducing subjectivity in goodness-of-fit assessments. J. Hydrol.480, 33–45 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, J. J. Research on ensemble streamflow forecasting for reservoir inflow of rockfill dam hydroelectric power station based on meteorology-hydrology-machine learning methods. China. Ph.D. thesis. Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology (2022).

- 17.Wu, J. Research on flood forecasting of small and medium-sized rivers in hilly areas based on Long Short-Term Memory network. China. Ph.D. thesis. Dalian University of Technology (2021).

- 18.Song, T. Y. Research on flood forecasting in hilly areas based on Long Short-Term Memory network. China Ph.D. thesis. Dalian University of Technology (2020).

- 19.Cheng, M., Fang, F., Kinouchi, T., Navon, I. M. & Pain, C. C. Long lead-time daily and monthly streamflow forecasting using machine learning methods. J. Hydrol.590, 125376 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bomers, A., Meulen, B., Schielen, R. M. J. & Hulscher, S. J. M. H. Historic flood reconstruction with the use of an artificial neural network. Water Resour. Res.55 (11), 9673–9688 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou, Y. L. et al. Short-term flood probability density forecasting using a conceptual hydrological model with machine learning techniques. J. Hydrol.604, 127255 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pölz, A. et al. Transformer versus LSTM: A comparison of deep learning models for karst spring discharge forecasting. Water Resources Research 60(4): e2022WR032602 (2024).

- 23.Wang, Y. et al. A novel strategy for flood flow prediction: integrating Spatio-Temporal information through a Two-Dimensional hidden layer structure. J. Hydrol.638, 131482 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, W. et al. A stacking ensemble machine learning model for improving monthly runoff prediction. Earth Sci. Inf.18 (1), 120 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kao, I. F., Zhou, Y., Chang, L. C. & Chang, F. J. Exploring a long short-term memory based encoder-decoder framework for multi-step-ahead flood forecasting. Journal Hydrology124631 (2020).

- 26.Hussain, D. K. A.A. Machine learning techniques for monthly river flow forecasting of Hunza river, Pakistan. Earth Sci. Informatics13(3) (2020).

- 27.Chen, S. J., Wei, Q., Zhu, Y. M., Ma, G. & Wang, L. Medium- and long-term runoff forecasting based on a random forest regression model. Water Sci. Technology: Water Supply. 20 (8 Pt.2), 3658–3664 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng, C., Chen, C. Y., Yin, X., Wang, M. M. & Zhang, Y. X. Watershed runoff simulation method integrating data assimilation and machine learning. Adv. Water Sci.34 (6), 839–849 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, or codes generated or used during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. E-mail: lmchen@nhri.cn.