Abstract

Amid the global phenomenon of population aging, the health of middle-aged and older adults has become an increasingly critical concern in Chinese society. Drawing on data from the 2021 China General Social Survey (CGSS), this study examines the impact of educational attainment on self-rated health among middle-aged and older adults in China, as well as the mechanisms through which leisure participation and Hukou system (household registration) affect this relationship. The results reveal that leisure participation partially mediates the relationship between education and self-rated health. Furthermore, Hukou system is found to negatively moderate both the direct effect of education on leisure participation and the indirect effect of education on self-rated health through leisure participation. These results provide new understanding of the mechanisms by which education impacts the health of middle-aged and older adults, offering important policy implications for tackling the challenges associated with an aging population.

Keywords: Educational attainment, Leisure participation, Self-rated health, Middle-aged and older adults, Hukou system

Introduction

The Seventh National Census of China, conducted in 2021, revealed that the number of elderly individuals aged 60 and above has exceeded 260 million, making up around 18.7% of the total population. Additionally, the population aged 65 and older has reached 190 million, representing 13.5% of the national population. By 2021, China had entered a stage of deep aging [1]. Health is a critical determinant of successful aging [2], and physical activity during leisure time in middle age has been shown to confer health benefits in later life [3]. Concurrently, with advancing age, the likelihood of developing various diseases and chronic conditions also increases [4]. Consequently, scholars from various disciplines have turned their attention to the antecedents of health among middle-aged and older adults.

The relationship between educational attainment and adult health has long attracted considerable scholarly attention. A substantial body of empirical research has consistently documented a positive association between education and various health outcomes [5–7]. Education not only significantly enhances physical health but also improves positive emotional states, thereby positively influencing mental well-being [8]. Educated individuals tend to have a better understanding of diseases [9], and education has been shown to reduce the likelihood of developing depression and individual mortality rates [10–12]. Earlier research has not only concentrated on the direct impact of education on individual health but have also explored how education indirectly influences health through various mediating and moderating factors [13–15]. For example, past research has demonstrated that engagement in social activities is an effective strategy for improving quality of life and alleviating the burdens associated with aging, including the decline in health and functionality [13]. Other studies have highlighted the beneficial effects of leisure activities for older adults, showing that such engagement helps maintain cognitive functions, physical health, and psychological well-being, thereby promoting successful aging [16]. Additionally, certain studies have examined how employment and income mediate the link between low educational attainment and mental health among older adults [15]. Research suggests that higher education levels provide individuals with better socioeconomic status, thereby enabling greater access to economic resources for health investments or participation in leisure and fitness activities [17, 18]. Hence, participation in leisure activities may act as a key intermediary in the connection between education and health. However, to date, only a few studies have investigated the role of leisure attitudes in the connection between educational attainment and mental health in older adults [19]. Furthermore, research has indicated that individuals with higher education levels seem to benefit more from participating in literacy programs, which reduce the likelihood of developing dementia, with cognitive leisure activities playing a moderating role in the relationship between education and cognition [14].

Leisure participation represents a critical aspect of life, serving as both a fundamental characteristic of daily living and a key indicator of quality of life. It plays a crucial role in balancing the pace of an individual’s life and can significantly influence health outcomes [20]. Engaging in specific leisure activities has been shown to improve both physical and mental health, with the potential to alleviate stress, regulate emotional well-being, and provide pleasurable experiences [21]. As an essential component of human life and development [22], leisure activities also form a vital part of the lives of older adults, impacting their health and overall quality of life [23]. Several studies suggest that leisure activities can help reduce anxiety and foster emotional well-being by facilitating communication with family and friends, reducing perceived stress, and offering psychological solace [24]. Moreover, adequate participation in leisure activities not only enhances the subjective well-being of older adults but also promotes positive emotions, leading to a more optimistic and resilient outlook on life [24–26]. Further research indicates that consistent participation in leisure activities supports the preservation of cognitive function, physical health, and psychological well-being in older adults, thus assisting them in coping with the challenges of aging [16].on the other hand, education serves as an important indicator of lifestyle, as early education fosters the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary for continued participation in activities throughout adulthood [27]Research has shown that educational attainment profoundly influences the way individuals utilize their leisure time, with higher-educated individuals being more likely to engage in intellectually stimulating and socially interactive activities [28]. Furthermore, the positive effects of leisure activities on cognitive function are more pronounced among educated elderly individuals compared to their less-educated counterparts. In fact, engaging in leisure activities during later life can prevent cognitive decline among Chinese older adults, with the protective effects being particularly significant for those with higher educational levels [29]. Recent studies have also revealed that middle-aged and older adults with higher levels of education tend to report fewer functional limitations in their daily activities, and that they are more likely to participate in social activities compared to their less-educated peers [30]. Similarly, research indicates that older adults with higher education levels exhibit better mental health and a more positive attitude toward leisure, with this attitude mediating the impact of education on mental health [19]. Research has indicated that employment and income serve as mediators in the link between low educational attainment and mental health issues in older adult [15]. Additionally, social participation has been recognized as a mediator in the connection between socioeconomic status and both the physical and mental well-being of older individuals [31].Furthermore, social participation mediates the relationship between educational level, neighborhood socioeconomic background, and self-rated health among middle-aged and older adults [32]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Leisure participation acts as a mediator in the connection between education and health in middle-aged and older adults.

The urban–rural household registration system, known as the Hukou system, is a uniquely Chinese social institution that originated in 1955. As a critical standard, the Hukou system plays a fundamental role in determining the allocation of social resources and life opportunities, including education, employment, healthcare, housing, pensions, and other aspects of daily life [33]. The Hukou system directly influences access to healthcare services for urban and rural residen [34]t, which may, in turn, affect their participation in leisure activities and overall health outcomes. Consequently, within the dual structure of the Hukou system, substantial differences exist between urban and rural populations regarding access to leisure spaces and facilities [35–37], further restricting or diminishing the opportunities and frequency of leisure participation among rural populations [35]. Therefore, as a system tied to one’s workplace and ascribed identity, the Hukou system significantly affects the leisure activities and health outcomes of both urban and rural populations in China.

The Hukou system was first implemented in China in the 1950s [38]. Initially designed as a mechanism of social control, its primary objective was to restrict rural residents’ access to state-allocated resources, welfare, and entitlement [39]. Under this system, individuals are classified as either agricultural or non-agricultural Hukou holders based on their place of birth and parental household registration, typically that of the mother [40]. Given the decentralization of fiscal and administrative authority, Chinese citizens’ access to social welfare and public services is largely determined by their types of Hukou system [41]. Urban residents generally benefit from more favorable policies than their rural counterparts, including access to healthcare services, local school enrollment, unemployment and retirement benefits, public housing, and higher-skilled job opportunities [33]. In contrast, individuals with rural Hukou, particularly rural migrants, frequently encounter labor market discrimination, leading to lower wages, fewer employment opportunities, and diminished job security relative to their urban peers [42]. When rural migrants relocate to cities in pursuit of higher-paying jobs, they are often excluded from a broad range of social, economic, and cultural benefits designated for urban residents, thereby exacerbating their socioeconomic vulnerability [43]. Broadly speaking, the Hukou system serves as a critical determinant of an individual’s socioeconomic rights. Functioning as a fundamental instrument of state governance, this registration-based system not only structures social administration but also plays a pivotal role in the allocation of resources and welfare in China [44]. Research has demonstrated that one of the main mechanisms driving the urban-rural divide in China is the unequal resource distribution perpetuated by the Hukou system [45].This bifurcation between urban and rural areas creates significant differences in both the social environment and individual characteristics, leading to divergent leisure lifestyles between the two groups [46]. Factors such as the availability of leisure spaces, the distance to recreational facilities, and the quality of equipment naturally influence individuals’ willingness to engage in leisure activities [35]. Studies have found that individuals residing in more remote areas are less interested in participating in leisure sports [47]. Individuals with higher levels of education tend to engage in leisure activities more frequently [45]. However, leisure participation is constrained by factors such as the availability of recreational spaces, the proximity of facilities, and the quality of equipment [35]. Compared to rural Hukou holders, urban Hukou residents generally enjoy greater advantages in accessing opportunities and mobility, which may lead to higher levels of leisure participation and more refined preferences in activity selection [45]. Consequently, individuals without urban Hukou, even if well-educated, may face resource constraints that hinder their full engagement in leisure activities. Moreover, studies have shown that Hukou system restricts the access of migrant workers’ children to basic education in urban areas, with urban Hukou holders typically enjoying superior educational opportunities compared to their rural counterparts [48]. Given that education is a strong determinant of an individual’s social capital [49], urban residents generally benefit from higher marginal returns on social capital, with superior quality and stronger support networks from relatives, friends, and the broader community [50]. Social capital plays a pivotal role in initiating and sustaining physical activity [51]and is closely associated with community participation, influencing engagement behaviors across various dimensions [52]. In other words, Hukou system not only limits educational opportunities for rural residents but also diminishes their social capital, ultimately affecting their participation in sports and community activities. Similar studies have shown that individuals with higher education seem to benefit more from cognitive leisure activities, such as participating in literacy programs, which reduce the likelihood of dementia. These cognitive leisure activities mediate the relationship between education and cognitive health [14]. Other studies have explored how self-esteem mediates the relationship between campus leisure participation and educational satisfaction [53]. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Hukou system moderates the relationship between education and leisure participation.

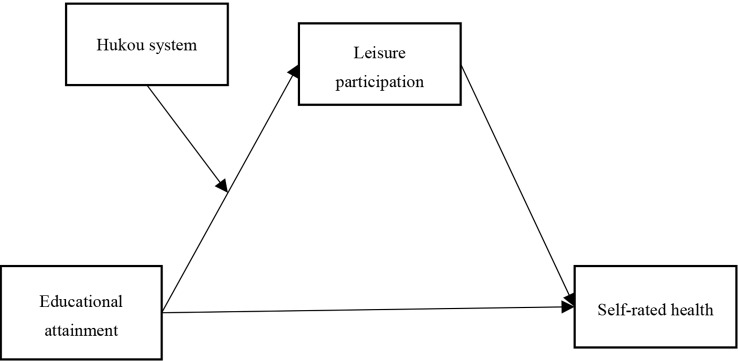

In light of the foregoing literature review and the specific aims of the present study, the present study, utilizing data from the 2021 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), focuses on individuals aged 45 to 70 and investigates the impact of educational attainment on the health of middle-aged and older adults. Additionally, this study incorporates leisure participation as a mediating variable and the Hukou system as a moderating variable to examine the underlying mechanism through which educational attainment influences self-rated health among middle-aged and older adults (Fig. 1). By constructing a moderated mediation model, this research delves into the mechanisms underlying the association between education and health among middle-aged and older adults, illustrating how individuals can gain more opportunities for leisure participation and improve health outcomes through education, while also considering how the distinctive Hukou system shapes the leisure participation behaviors and health levels of urban and rural residents.

Fig. 1.

Research framework

Methods

Sample and participants

The data for this study were obtained from the 2021 China General Social Survey (CGSS). The sample includes 28 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government of China, excluding Xinjiang, Tibet, Hainan, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. The survey covers a range of topics, including respondents’ demographic information, lifestyle, health status, and social attitudes. The survey comprised a total of 8,148 respondents, ranging in age from 18 to 99. Given that the focus of this study is the middle-aged and older population, and in line with WHO standards, we categorized respondents into three age groups: middle-aged adults (45–59), younger-old adults (60–74), and older-old adults (75 and above) [54]. Prior research has shown that age moderates the relationship between health and quality-of-life assessments [55]; younger individuals may underreport minor symptoms, whereas older adults may overestimate their health due to illness adaptation and reduced health sensitivity [56]. To address such biases, we excluded respondents outside the age range of 45 to 70. This decision was also informed by our study’s focus on educational attainment among the middle-aged and older Chinese population. China’s economic and agricultural reforms in the early 1980s, followed by a series of educational reforms in the mid-1980s, provided relatively stable and consistent educational environments for those born between 1953 and 1978 [57]. After excluding cases with missing or abnormal values, the final analytic sample consisted of 3,666 respondents, representing 55% of the original sample.

Among all valid samples, 46.2% of respondents were male, while 53.8% were female. In terms of educational attainment, 39.8% had completed primary school or below, 33.5% had attained a middle school education or lower, 18.3% had a high school education or below, and 8.4% had attended college or higher. Regarding household registration status, 62.1% of respondents held an agricultural Hukou, whereas 37.9% were registered as non-agricultural residents. The average annual per capita income of the respondents was 850,060.96 RMB. Additionally, 56.6% of respondents perceived their socioeconomic status as being below the middle level, 37.1% considered themselves to be in the middle class, and 6.3% regarded their socioeconomic status as above the middle level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables in the study

| Variables | Description | Frequency(%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female = 0 | 1971(53.8%) | 0.460(0.499) |

| Male = 1 | 1695(46.2%) | ||

| Age | Continuous variable | 45–70 years old | 57.986(7.334) |

| Hukou system | Rural Hukou = 0 | 2277(62.1%) | 0.379(0.485) |

| Urban Hukou = 1 | 1389(37.9%) | ||

| Individual annual income | Continuous variable | 0-9.993 million RMB | 3.492(1.743) |

| Subjective socioeconomic status | Lower class = 1 | 959(26.2%) | 2.240(0.926) |

| Lower-middle class = 2 | 1115(30.4%) | ||

| Middle class = 3 | 1361(37.1%) | ||

| Upper-middle class = 4 | 208(5.7%) | ||

| Upper class = 5 | 23(0.6%) | ||

| Educational attainment | Primary school or below = 1 | 1459(39.8%) | 1.953(0.956) |

| Junior high school = 2 | 1228(33.5%) | ||

| Senior high school / Technical secondary school = 3 | 672(18.3%) | ||

| University or above = 4 | 307(8.4%) |

Measures

Independent variable: education attainment

Education attainment was measured using the question: “What is the highest level of education you have completed?” Drawing on previous studies [58], education level was categorized into four levels: (1) Primary or below: Including no formal education, literacy classes, and primary school education. (2)Secondary school: Including middle school education.(3) High school: Including vocational high school, general high school, secondary technical school, and technical college.(4)College or higher: Including associate degree, bachelor’s degree, and graduate studies.

Dependent variable: Self-Rated health

Self-rated health is widely utilized in research as a key indicator of elderly health and is one of the most commonly used subjective measures of health status among older adults [59]. It offers a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s overall health condition [60]. When employed to predict general health outcomes in the elderly, SRH is regarded as a reliable and valid measure [61]. Given its extensive adoption in prior studies as a health metric for older adults, Self-rated health provides a holistic reflection of their health status [60]. Accordingly, this study follows the established literature and employs self-rated health as a primary measure of health status. In this study, Self-rated health was assessed using the question: “How would you rate your current physical health?” Respondents were asked to evaluate their health on a scale from 1 (very poor health) to 5 (very good health). A higher score indicates better perceived health.

Mediator variable: leisure participation

Leisure participation was measured by the following question: “In the past year, how often did you engage in the following activities during your leisure time?” The question included 12 items, such as watching television, watching movies in cinemas, shopping, participating in cultural activities, attending family gatherings, socializing with friends, listening to music at home, engaging in physical exercise, watching live sports events, and doing handicrafts. Response options ranged from “never,” “a few times a year,” “a few times a month,” “a few times a week,” to “every day.” Based on previous research [62], we summed the frequencies of leisure participation across the 12 activities to create a continuous variable representing leisure participation.

Moderator variable: Hukou system

Hukou system, an essential administrative system in China, has resulted in a rural-urban divide in areas such as geography, labor markets, and public services. Hukou system was categorized into two groups: 0 represents residents with a rural Hukou, while 1 represents residents with an urban Hukou.

Analytical strategy

To investigate the underlying mechanism of leisure participation and Hukou system in the relationship between educational attainment and self-rated health among middle-aged and older adults, we conducted a three-step analysis using SPSS 27.0 and the SPSS macro program PROCESS 4.1. First, we performed descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis on all variables in this study to outline the basic characteristics of the sample and preliminarily assess the relationships among variables. Second, to test the direct effect of educational attainment on the health of older adults and the mediating role of leisure participation, we employed a mediation analysis using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro. Finally, to explore the moderating effect of the hukou system, we utilized Model 7 of the PROCESS macro to examine both its direct moderating effect on the relationship between educational attainment and leisure participation and its indirect moderating effect on the relationship between educational attainment and self-rated health.

Following this analytical strategy, we constructed both a mediation model and a moderated mediation model. The mediation model (Model 4) was used to test the indirect pathway of educational attainment → leisure participation → self-rated health. The PROCESS macro employed the bootstrap method with 5,000 resamples to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect. If the CI did not contain zero, the mediation effect was considered statistically significant. The specific mediation models are presented in Eqs. (1) and (2). The moderated mediation model (Model 7) was used to assess whether the mediating variable’s effect was contingent on the moderating variable (W), specifically testing the direct pathway educational attainment → leisure participation, as shown in Eq. (3). Additionally, the moderated mediation model examined whether the Hukou system moderated the indirect pathway of educational attainment → leisure participation → self-rated health.

|

1 |

|

2 |

Here, a represents the effect of X on M, while c′ denotes the direct effect of educational attainment (X) on self-rated health (Y) after controlling for leisure participation (M). The coefficient b captures the effect of leisure participation (M) on self-rated health (Y), and e₁ and e₂ represent the error terms. If the indirect effect (a × b) is statistically significant, it indicates that M serves as a mediator in the relationship between X and Y.

|

3 |

Here, a₁ represents the main effect of educational attainment (X) on leisure participation (M), while a₂ denotes the main effect of Hukou system (W) on leisure participation (M). The coefficient a₃ corresponds to the interaction term (X × W), which tests whether Hukou system (W) moderates the effect of educational attainment (X) on leisure participation (M). If a₃ (the interaction term X × W) is statistically significant, it indicates that W moderates the relationship between X and M.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 2 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for each variable. The findings reveal a statistically significant positive correlation between education level and leisure participation (r = 0.450, p < 0.01), as well as between education level and self-rated health (r = 0.169, p < 0.01). Leisure participation is positively correlated with self-rated health (r = 0.215 p < 0.01) and with Hukou system (r = 0.363, p < 0.01). Finally, Hukou system is also positively associated with self-rated health (r = 0.101, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations and correlations among variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Age | 0.060** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Income | 0.258** | -0.089** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Subjectivesocioeconomic status | -0.018 | 0.016 | 0.128** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Educational attainment | 0.156** | -0.149** | 0.338** | 0.161** | 1 | |||

| 6. Leisure participation | 0.025 | -0.144** | 0.272** | 0.230** | 0.450** | 1 | ||

| 7. Hukou system | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.332** | 0.151** | 0.511** | 0.363** | 1 | |

| 8. Self-rated health | 0.060** | -0.147** | 0.180** | 0.213** | 0.169** | 0.215** | 0.101** | 1 |

| Mean | 0.460 | 57.986 | 3.492 | 2.240 | 1.953 | 2.205 | 0.379 | 3.290 |

| SD | 0.499 | 7.334 | 1.743 | 0.926 | 0.956 | 0.546 | 0.485 | 1.096 |

Note: N = 3666. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. SD = Standard Deviation

Hypothesis testing

To examine the direct effect of education on the health of middle-aged and older adults, as well as the mediating role of leisure participation, this study employs the SPSS macro PROCESS developed by Hayes to test the mediation model (Model 4). The results, as presented in Table 3, reveal that education level has a positive effect on the health of middle-aged and older adults (B = 0.088, p < 0.001). Additionally, education level exerts a significant influence on leisure participation (B = 0.216, p < 0.001), and leisure participation has a significant impact on the health of middle-aged and older adults (B = 0.234, p < 0.001). As indicated in Table 3, the total effect of education on self-rated health is 0.088[0.050, 0.126], with a direct effect of 0.037[-0.004, 0.784] and an indirect effect of 0.051[0.036, 0.067]. Since the confidence interval for the direct effect includes zero, these results suggest that leisure activities fully mediate the relationship between educational attainment and self-rated health, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Results of mediating hypotheses

| Variables | leisure participation B(SE) |

self-rated health B(SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant |

1.787*** (0.070) |

3.483*** (0.154) |

3.064*** (0.167) |

| Gender |

-0.068*** (0.016) |

0.068 (0.036) |

0.084* (0.036) |

| Age |

-0.006*** (0.001) |

-0.020*** (0.002) |

-0.018*** (0.002) |

| Income |

0.042*** (0.005) |

0.069*** (0.011) |

0.059*** (0.011) |

| Subjective socioeconomic status |

0.090*** (0.009) |

0.223*** (0.019) |

0.202*** (0.019) |

| Educational attainment |

0.216*** (0.009) |

0.088*** (0.020) |

0.037 (0.021) |

| leisure participation |

0.234*** (0.036) |

||

| Total effect [95% CI] | 0.088[0.050, 0.126] | ||

| Direct effect [95% CI] | 0.037[-0.004, 0.784] | ||

| Indirect effect [95% CI] | 0.051[0.036, 0.067] | ||

| △R2 | 0.205*** | 0.043*** | 0.063*** |

Notes: Bootstrap size = 3666. CI = confidence interval. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. SE = Standard Error

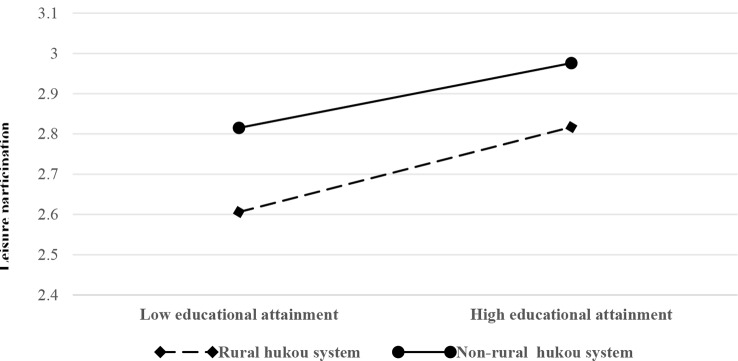

To further examine the moderating effects of Hukou system in the association between education level and leisure participation, we employs Model 7 from the PROCESS macro to test the moderating effect of Hukou system (Table 4). The results indicate that Hukou system significantly affects leisure participation (B = 0.177, p < 0.001), and the interaction between education level and Hukou system has a negative effect on leisure participation (B = -0.050, p < 0.01). This suggests that Hukou system moderates the impact of education on leisure participation, with the effect of education on leisure participation being weaker for middle-aged and older adults with an urban Hukou system compared to those with a rural Hukou system. Thus, the moderating effect of Hukou system is significant, and the moderated mediation effect exists, providing support for Hypothesis 2.

Table 4.

Results for the interaction effect

| Variables | B (SE) | p | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables: leisure participation | |||

| Constant | 2.338(0.068) | 0.000 | [2.205,2.472] |

| Gender | -0.054(0.016) | 0.001 | [-0.086,-0.022] |

| Age | -0.007(0.001) | 0.000 | [-0.009,-0.005] |

| Income | 0.032(0.005) | 0.000 | [0.022,0.042] |

| Subjective socioeconomic status | 0.086(0.009) | 0.000 | [0.069,0.103] |

| Educational attainment | 0.183(0.010) | 0.000 | [0.163,0.204] |

| Hukou system | 0.177(0.019) | 0.000 | [0.139,0.215] |

| Educational attainment x Hukou system | -0.050(0.019) | 0.008 | [-0.087,-0.013] |

| R2 = 0.268***, F-value = 191.604 | |||

Notes: Bootstrap size = 5000. Boot SE = bootstrapping standardized error. LL = low limit, UL = upper limit, CI = confidence interval. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Finally, to provide a more illustrative depiction of the moderating effects at different levels of Hukou system, we examined the conditional effect of education attainment on leisure participation at one standard deviation above and below the mean of Hukou system. A simple slope analysis was performed to further investigate the moderating role of Hukou system (Fig. 2). Figure 2 reveals that the positive effect of educational attainment on leisure participation is stronger for individuals with rural household registration than for those with urban registration, particularly at higher levels of education. Furthermore, the results in Table 5 show that education level significantly influences health through leisure participation for both types of Hukou system. As Hukou system shifts from rural (B = 0.047, 95% CI: [0.032, 0.064]) to urban (B = 0.036, 95% CI: [0.024, 0.048]), the indirect effect of education on self-rated health through leisure participation is strongest for those with a rural Hukou system and weakest for those with an urban Hukou system. In other words, for individuals with urban household registration, the educational advantage associated with their Hukou status exerts a stronger positive effect on self-rated health.

Fig. 2.

Interaction plot of educational attainment and Hukou system predicting Leisure participation

Table 5.

Results for the index of moderated mediation and conditional indirect effects

| Moderator: Hukou system | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional indirect effects [95% CI] | ||||

| M– 1SD | 0.047 | 0.008 | 0.032 | 0.064 |

| M + 1SD | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.048 |

| Index of moderated mediation [95% CI] | ||||

| Hukou system | -0.117 | 0.005 | -0.022 | -0.003 |

Notes: Bootstrap size = 5000. Boot SE = bootstrapping standardized error. LL = low limit, UL = upper limit, CI = confidence interval. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001

Discussions

This study, utilizing the 2021 CGSS data, explores the complex relationships between education, leisure participation, and the health of middle-aged and older adults. Firstly, our study demonstrates that leisure participation partially mediates the relationship between education and health. That is, individuals with higher levels of education are more inclined to engage in leisure activities, which in turn lead to improved health outcomes in later life [29, 30]. This suggests that higher education not only directly contributes to better health but also increases the likelihood of engaging in leisure activities that can further promote health. Thus, our study further elucidates the mediating mechanism through which education influences the health of middle-aged and older adults, offering a more comprehensive explanation of the underlying processes. This finding lays a foundation for future research and introduces a new theoretical framework and direction for investigating the relationship between education and health.

Second, our research identifies that the Hukou system moderates the relationship between education level and leisure participation. Specifically, individuals from different Hukou system exhibit varying levels of engagement in leisure activities, with those possessing higher education levels more likely to participate in leisure activities [45], particularly among those with an urban Hukou system. Conversely, individuals with a rural Hukou system tend to participate less. In other words, when rural residents transition from a rural to an urban household registration status, they are likely to gain greater access to educational opportunities. Higher educational attainment, in turn, fosters greater engagement in leisure activities. Consequently, we posit that the influence of the household registration system on leisure participation outweighs that of education. Once rural residents acquire urban household status, the effect of education on leisure participation is attenuated by the household registration system. Additionally, we find that the indirect effect of education on the health of middle-aged and older adults through leisure participation may be contingent upon Hukou system. As a fundamental mechanism of China’s urban-rural divide, Hukou system significantly influences the unequal distribution of resources. Middle-aged and older adults with higher education levels are more likely to be motivated to participate in leisure activities, which in turn benefit their health. While scholars generally agree that education is a precursor to better health among older adults, the present study offers a new perspective by emphasizing the moderating role of Hukou system in the relationship between education and leisure participation. Furthermore, several Asian countries, such as North Korea and Vietnam, also implement some form of a Hukou system. Therefore, the findings of this study regarding the moderating effects of the Hukou system may hold significant academic value beyond China, potentially offering insights for comparative research in these countries.

Practical implications

This study offers several practical recommendations aimed at promoting the health of middle-aged and older adults. First, given the significant positive impact of education on the health of this demographic, increasing the educational level of middle-aged and older adults can effectively enhance their health. Therefore, the government, society, and communities should continue to promote the widespread development of education for older adults, focusing on both its broad-based expansion and its targeted, high-efficiency implementation. This could include initiatives such as the provision of smart elderly care services and the establishment of senior universities to foster lifelong learning among older populations. Second, the study shows that leisure participation acts as a mediator in the relationship between education and health. Engagement in leisure activities is an important channel through which education contributes to improved health. Previous research indicates that participation in leisure activities offers significant benefits for older adults, helping to maintain cognitive and physical functions as well as psychological well-being, all of which are crucial for successful aging [16]. Consequently, the government, society, and communities should promote the construction of sports and fitness facilities and encourage middle-aged and older adults to engage in appropriate and moderate levels of leisure activities and physical exercise. Lastly, this study identifies that the Hukou system moderates the relationship between education and leisure participation, as well as the indirect effect of education on health. Rural Hukou system holders in China face various systemic barriers such as occupational inequality, lack of social welfare, and cultural and linguistic disadvantages [43]. The government should intensify efforts to develop leisure infrastructure in rural areas, ensuring that residents with rural household registration have greater access to leisure opportunities and resources. This would ensure that individuals across different Hukou system have access to quality education, thereby enhancing cognitive levels, increasing leisure participation, and ultimately promoting the health of middle-aged and older adults.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite its contributions, this study also has several limitations. First, it utilizes a cross-sectional design, which prevents drawing causal conclusions about the relationships between education, Hukou system, and the health of middle-aged and older adults. Given the limitations in data collection timing and methods, it may not fully capture the long-term changes or dynamic processes through which education levels, under different Hukou system conditions, affect leisure participation and health outcomes over time. Future research could consider conducting longitudinal studies that track the same cohort of middle-aged and older adults over an extended period to observe how the relationship between education and health evolves at different stages and provide further evidence of the causal effects of education on health. Second, the reliance on self-reported data in this study introduces the possibility of subjective bias. Personal opinions, attitudes, and emotional states of respondents may significantly influence the quality of the data. For example, respondents may exaggerate or underreport their participation in physical exercise or leisure activities to align with personal expectations or socially accepted standards. Third, this study relies on a single-item measure of self-rated health (SRH), which may lack objectivity and methodological rigor. While SRH is widely used in health research [59], individuals consider diverse factors—such as health conditions, behaviors, and functioning—when responding, leading to systematic differences across groups. Its predictive validity also varies by social and health characteristics, with experiential knowledge enhancing accuracy [63]. Future research should integrate subjective and objective indicators to construct more comprehensive health measures, while accounting for biases related to gender and sociocultural context, particularly among older adults. Finally, the Hukou system is a relatively unique social institution in China [64], and therefore, the findings of this study may not be applicable to all countries or regions. However, aside from China, there are several countries that implement Hukou system or similar resident registration systems. For example, Vietnam has a system similar to China’s Hukou, which influences residents’ mobility, employment, education, and healthcare. North Korea’s citizen registration strictly controls population movement, with citizens’ residence and occupation being rigorously managed, and migration requiring government approval. Although these countries’ household registration or resident registration systems differ in specific details, most are used for managing population data, distributing social welfare, and providing public services. Future research could attempt to collect a broader range of cross-national sample data, so that the conclusions of this study are not only applicable to specific regions or countries but also have relevance for Southeast Asian countries.

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Survey and Data Center at Renmin University of China for providing the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) data used in this study.

Abbreviations

- SD

Standard deviation

- CI

Confidence interval

- SE

Standard error. Boot

- SE

Bootstrapping standardized error

- LL

Low limit

- UL

Upper limit

Author contributions

J and Y performed the data analyses. J drafted the manuscript. G and Y revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of manuscript and approved it for publication.

Funding

The work was supported by The Xingdian Talent Support Program project (41112080006/015).

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Chinese General Social Survey with the primary accession link http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhang M, Chen C, Zhou X, Wang X, Wang B, Huan F, Liu J. The impact of accelerating population aging on service industry development: evidence from China. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(6):e0296623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Liu J, Rozelle S, Xu Q, Yu N, Zhou T. Social engagement and elderly health in China: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal survey (CHARLS). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kekäläinen T, Freund AM, Sipilä S, Kokko K. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between leisure time physical activity, mental well-being and subjective health in middle adulthood. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15(4):1099–116. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W, Wu B, Tan SY, Li B, Lou VW, Chen Z, Wang Y. Understanding health and social challenges for aging and long-term care in China. Res Aging. 2021;43(3–4):127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niemeyer H, Bieda A, Michalak J, Schneider S, Margraf J. Education and mental health: do psychosocial resources matter? SSM-population Health. 2019;7:100392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman D, Smith JP. The increasing value of education to health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1728–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Kippersluis H, O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E. Long-run returns to education: does schooling lead to an extended old age? J Hum Resour. 2011;46(4):695–721. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai X, Li W. Impact of education, medical services, and living conditions on health: evidence from China health and nutrition survey. In healthcare. MDPI. 2021;9:1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tsou MT. Association of education, health behaviors, concerns, and knowledge with metabolic syndrome among urban elderly in one medical center in Taiwan. Int J Gerontol. 2017;11(3):138–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Dong Y, Liu X, Zhang L, Bai Y, Hagist S. The more educated, the healthier: evidence from rural China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lager ACJ, Torssander J. Causal effect of education on mortality in a quasi-experiment on 1.2 million Swedes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(22):8461–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies NM, Dickson M, Davey Smith G, Van Den Berg GJ, Windmeijer F. The causal effects of education on health outcomes in the UK biobank. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2(2):117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamar B, Coberley CR, Pope JE, Rula EY. Impact of a senior fitness program on measures of physical and emotional health and functioning. Popul Health Manage. 2013;16(6):364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Chi I. Do cognitive leisure activities really matter in the relationship between education and cognition? Evidence from the aging, demographics, and memory study (ADAMS). Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(3):252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sperandei S, Page A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J. Low education and mental health among older adults: the mediating role of employment and income. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(5):823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala G, Jopp D, Gobet F, Ogawa M, Ishioka Y, Masui Y, Gondo Y. The impact of leisure activities on older adults’ cognitive function, physical function, and mental health. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0225006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J Health Econ. 2010;29(1):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leopold L, Engelhartdt H. Education and physical health trajectories in old age. Evidence from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Public Health. 2013;58:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belo P, Navarro-Pardo E, Pocinho R, Carrana P, Margarido C. Relationship between mental health and the education level in elderly people: mediation of leisure attitude. Front Psychol. 2020;11:573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Hsu CC, Lin CT. Leisure participation behavior and psychological well-being of elderly adults: an empirical study of Tai Chi Chuan in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(18):3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nkuba M, Hermenau K, Hecker T. The association of maltreatment and socially deviant behavior––Findings from a National study with adolescent students and their parents. Mental Health Prev. 2019;13:159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kepper MM, Myers CA, Denstel KD, Hunter RF, Guan W, Broyles ST. The neighborhood social environment and physical activity: a systematic scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2019;16:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Zhang J. Impacts of leisure and tourism on the elderly’s quality of life in intimacy: A comparative study in Japan. Sustainability. 2018;10(12):4861. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsay Smith G, Banting L, Eime R, O’Sullivan G, Van Uffelen JG. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2017;14:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida Y, Iwasa H, Ishioka Y, Suzukamo Y. Leisure activity moderates the relationship between living alone and mental health among J apanese older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(5):421–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toyama M, Fuller HR. Longitudinal stress-buffering effects of social integration for late-life functional health. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2020;91(4):501–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Lv C, Li X, Zhang J, Chen K, Liu Z, Zhang Z. The positive impacts of early-life education on cognition, leisure activity, and brain structure in healthy aging. Aging. 2019;11(14):4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gauthier AH, Smith SJ. Educational attainment and leisure time activities. An International Perspective. Social Indicators Research. 2022.

- 29.Zhu X, Qiu C, Zeng Y, Li J. Leisure activities, education, and cognitive impairment in Chinese older adults: a population-based longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(5):727–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng SZ, Fu XX, Feng XL. Association between education and the onset of disability in activities of Daily living in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: the mediator role of social participation. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. Yi Xue ban = journal of Peking university. Health Sci. 2021;53(3):549–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Su D, Chen Y, Tan M, Chen X. Effect of socioeconomic status on the physical and mental health of the elderly: the mediating effect of social participation. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang W, Wu YYST. Individual educational attainment, neighborhood-socioeconomic contexts, and self-rated health of middle-aged and elderly Chinese: exploring the mediating role of social engagement. Health Place. 2017;44:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Treiman DJ. Social origins, Hukou conversion, and the wellbeing of urban residents in contemporary China. Soc Sci Res. 2013;42(1):71–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Shi L, Liang H, Ding G, Xu L. Urban-rural disparities in health care utilization among Chinese adults from 1993 to 2011. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomes CS, Matozinhos FP, Mendes LL, Pessoa MC, Velasquez-Melendez G. Physical and social environment are associated to leisure time physical activity in adults of a Brazilian City: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0150017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ding C, Song C, Yuan F, Zhang Y, Feng G, Chen Z, Liu A. The physical activity patterns among rural Chinese adults: data from China National nutrition and health survey in 2010–2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozma G, Teperics K, Czimre K, Radics Z. Characteristics of the Spatial location of sports facilities in the Northern great plain region of Hungary. Sports. 2022;10(10):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boffy-Ramirez E, Moon S. The role of China’s household registration system in the urban-rural income differential. China Economic J. 2018;11(2):108–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan KW. The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Popul Dev Rev. 2010;36(2):357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song Q, Smith JP. Hukou system, mechanisms, and health stratification across the life course in rural and urban China. Health & place. 2019;58:102150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Gersovitz M. Sectoral asymmetries and a social-welfare interpretation of Hukou. China Econ Rev. 2016;38:108–15. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Wu X. Occupational segregation and earnings inequality: rural migrants and local workers in urban China. Soc Sci Res. 2017;61:57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hung J. Hukou system influencing the structural, institutional inequalities in China: the multifaceted disadvantages rural Hukou holders face. Social Sci. 2022;11(5):194. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu Y. Does Hukou still matter? The household registration system and its impact on social stratification and mobility in China. Social Sci China. 2008;29(2):56–75. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou L. Leisure distinction: the social stratification mechanism and its intergenerational difference of Chinese residents’ leisure participation. J Sichuan Univ Sci Eng (Soc Sci Ed). 2020;35:17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weifei LI, Shaoxiang SHI, Lin YUAN. Differences in and influencing factors of the leisure lifestyles of urban and rural residents. Tourism Hospitality Prospects. 2022;6(5):50. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen C, Tsai LT, Lin CF, Huang CC, Chang YT, Chen RY, Lyu SY. Factors influencing interest in recreational sports participation and its rural-urban disparity. PLoS ON. 2017;12(5):e0178052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Tang X. Educational inequality between urban and rural areas in China. Lecture Notes Educ Psychol Public Media. 2023;30:293–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, Van den Brink HM, Groot W. A meta-analysis of the effect of education on social capital. Econ Educ Rev. 2009;28(4):454–64. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z, Wei Y, Li Q, Lan J. The mediating role of social capital in digital information technology poverty reduction an empirical study in urban and rural China. Land. 2021;10(6):634. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiltshire G, Stevinson C. Exploring the role of social capital in community-based physical activity: qualitative insights from parkrun. Qualitative Res Sport Exerc Health. 2018;10(1):47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu T, Mao S. Individual social capital and community participation: an empirical analysis of Guangzhou, China. Sustainability. 2022;14(12):6966. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unguren E. Exploring the moderating effect of campus recreation participation on the relationship between education satisfaction and self-esteem. Pol J Sport Tourism. 2020;27(3):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ai Z, Tang C, Wen X, Kartheepan K, Tang S. Examining the impact of chronic diseases on activities of daily living of middle-aged and older adults aged 45 years and above in China: a nationally representative cohort study. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1303137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cubi-Molla P, Shah K, Garside J, Herdman M, Devlin N. A note on the relationship between age and health-related quality of life assessment. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1201–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Potter S, Gerstorf D, Schmiedek F, Drewelies J, Wolff JK, Brose A. Health sensitivity in the daily lives of younger and older adults: correlates and longer-term change in health. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(6):1261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang C. Minban education: the planned elimination of the people-managed teachers in reforming China. Int J Educational Dev. 2002;22(2):109–29. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Liu H. Individual’s gender ideology and happiness in China. Chin Sociol Rev. 2021;53(3):256–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garbarski D. Research in and prospects for the measurement of health using self-rated health. Pub Opin Q. 2016;80(4):977–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu N, Xu S, Zhang J. Community social capital, family social capital, and self-rated health among older rural Chinese adults: empirical evidence from rural Northeastern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caetano SC, Silva CM, Vettore MV. Gender differences in the association of perceived social support and social network with self-rated health status among older adults: a population-based study in Brazil. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park H, Kim J. The use of assistive devices and social engagement among older adults: heterogeneity by type of social engagement and gender. GeroScience. 2024;46(1):1385–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Idler E, Leventhal H, McLaughlin J, Leventhal E. In sickness but not in health: self-ratings, identity, and mortality. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):336–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng J. Insiders’ entitlements: Formation of the household registration (huji/hukou) system (1949–1959) (Doctoral dissertation). 2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Chinese General Social Survey with the primary accession link http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn.