Abstract

The advent of precision therapy has revolutionized breast cancer treatment, driven by the development of innovative diagnostic techniques and targeted drugs. Identifying biomarkers related to therapy response is crucial for tailoring treatment strategies for breast cancer patients. Liquid biopsies have emerged as minimally invasive techniques for biomarker profiling, leveraging the increasing sensitivity for detecting oncogenic drivers. These liquid biopsy methods, involving the testing of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in biofluids, offer more opportunities for early cancer detection, monitoring treatment efficacy, and identifying resistance mechanisms. This review focuses on the technical methodologies employed for the detection of CTCs and ctDNA. Beyond the technical aspects, we discuss the clinical applications of these biomarkers in breast cancer, including their roles in early detection, monitoring treatment response, and guiding therapeutic decisions. We also address the challenges associated with CTC and ctDNA detection, such as low concentrations in biofluids and tumor heterogeneity, which can complicate analysis and interpretation. By discussing the current landscape of CTC and ctDNA methodologies and their clinical implications, this review highlights the potential of liquid biopsies to enhance personalized medicine approaches in breast cancer management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13058-025-02024-7.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Breast cancer, Liquid biopsy, Circulating tumor cells, Circulating tumor DNA

Background

Breast cancer continues to be a significant global health burden, with an alarming 2.3 million new cases diagnosed worldwide each year [1]. Despite advancements in early detection and treatment strategies, it remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women. The gold standard for molecular profiling of breast cancer has traditionally relied on tumor tissue biopsies, which provide valuable information for subtyping, treatment planning, and identifying prognostic and predictive biomarkers. However, tissue biopsies are invasive procedures and may not accurately represent the heterogeneity within the tumor, posing challenges for long-term surveillance [2]. Furthermore, tissue biopsies may have lengthy turnaround times, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment initiation [3]. These limitations have driven the exploration of liquid biopsies as a complementary approach to tissue biopsies, offering the potential for early identification of resistance mechanisms, monitoring treatment response, and accurate and prompt diagnosis.

At present, liquid biopsy offers a range of valuable biomarkers, including CTCs, ctDNA, extracellular vesicles, tumor metabolites, tumor-associated antigens, and tumor-educated platelets. Among these, CTCs and ctDNA have emerged as the most extensively researched circulating biomarkers to date. These biomarkers can provide invaluable insights into tumor characteristics, genetic alterations, and actionable biomarkers, facilitating diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection without the need for invasive procedures. This review summarizes various methods employed for detecting CTCs and ctDNA (Table 1) and provides an overview of clinical trials investigating the use of CTCs and ctDNA as liquid biopsy methods for breast cancer (Table S1). We aim to elucidate the current landscape of liquid biopsy in breast cancer, highlighting its potential applications, challenges, and future directions in this rapidly evolving field.

Table 1.

Methods frequently used for CTCs and ctDNA detection in breast cancer

| Detection | Source material | Method | Clinical use | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTC | Whole blood; Cerebrospinal fluid | CellSearch® | diagnosis and molecular characterization | [4–7] |

| Whole blood | Parsortix® PC1 | CTC detection | [8–11] | |

| Whole blood | RossetteSep™ | CTCs characterise EMT | [12] | |

| Whole blood | Filtration-based microfluidic CTC detection device | CTC detection | [13] | |

| Serum | Aptamer-mediated target-induced strand displacement amplification | CTC detection | [14] | |

| Whole blood | Platform of DHA-modified and HIF-1-induced fluorometric aptamer-conjugated AuNPs | CTC detection | [15] | |

| Whole blood | PGK1/G6PD-based metabolic typing method | glucose metabolic (GM) + CTCs detection | [16] | |

| Whole blood | CytoSorter® | CTC enumeration | [17, 18] | |

| Whole blood | Real-time methylation-specific Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | ESR1 methylation in the EpCAM+ CTC and plasma ctDNA | [19] | |

| ctDNA | Whole blood | Guardant360 CDx | HER2 -mut MBC, biomarker for drug decision | [20] |

| Whole blood | FoundationOne®/FoundationOne® CDx | Detect potentially targetable mutations; identify potential combinatorial treatment options | [21, 22] | |

| Plasma | Signatera | associated with the risk of distant metastasis; Prognostic Value | [23, 24] | |

| Plasma | MammaPrint | Monitoring for response and recurrence | [25] | |

| Tumor tissue and blood; plasma | NGS | Detection of TP53 and PIK3CA mutations, ESR1 and its methylation | [19, 26, 27] | |

| Plasma | Pyrosequencing | Detection of SPAG6, PER1, and NKX2-6 | [28] | |

| Plasma | droplet-digital PCR (ddPCR), dPCR-SEQ | Resistance monitoring | [29–31] | |

| Whole blood | Targeted NGS | Recurrence monitoring | [32–35] | |

| Whole blood | Whole-genome amplification and NGS | quantity of cell free DNA (cfDNA) | [36] | |

| Whole blood | RT-qPCR and NGS | CTCs, cfDNA, EVs, and miRNA | [37] |

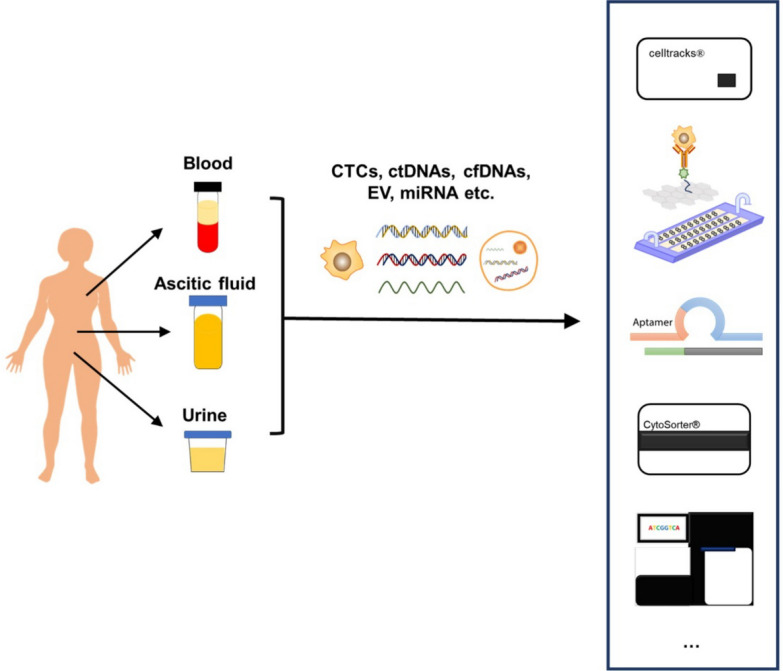

Detection platforms for CTCs in breast cancer liquid biopsy

In recent years, the field of liquid biopsy for breast cancer has witnessed a surge in the development of innovative platforms designed to detect and analyze CTCs and ctDNA (Fig. 1). The “seed” of the tumor, CTCs are cancer cells that circulate in the bloodstream after spontaneously isolating from an initial or metastatic tumor. These may result in new, potentially fatal [38]. Cancer patients’ peripheral blood (PB) include CTC, whereas healthy people’s PBs do not [2, 39]. The American Joint Committee on Cancer and National Comprehensive Cancer Network both promote CTC technology as a liquid biopsy and as a prognostic indicator for breast cancer, respectively [40].

Fig. 1.

CTCs and ctDNA detection strategies in breast cancer were summarized

CellSearch system for CTCs detection

The CellSearch system is an automated technology for efficiently obtaining, counting, and analyzing CTCs using immunomagnetic beads [4–7]. It targets specific markers like cytokeratins (CKs) and epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAM), making it suitable for clinical trials in breast cancer. This system employs anti-EpCAM antibody-coated nanoparticles, nuclear dyes, and antibodies for leukocyte discrimination and epithelial cell identification. After immunomagnetic capture, fluorescent markers are added for CTC detection and quantification, with cell counts performed by the CellTracks Analyzer®, a semi-automated microscope [41, 42]. As the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved method for monitoring metastatic disease, CellSearch® is recognized for its standardization and reliability [32].

Parsortix® PC1 system for CTC detection

The Parsortix® PC1 system is the other FDA-approved microfluidic device designed to enrich CTCs from whole blood based on their size and deformability rather than cell surface markers like EpCAM. By gently capturing larger and less deformable cancer cells, the system preserves cell viability and allows for downstream molecular analyses, such as RNA sequencing, FISH, protein profiling, and cytopathological evaluations [8–11]. The Parsortix® PC1 System and CellSearch® System are both FDA-cleared technologies for isolating CTCs, but they use different enrichment strategies. CellSearch® relies on immunomagnetic beads targeting EpCAM, which is highly expressed on many—but not all—CTCs. In contrast, Parsortix® captures cells in a microfluidic cassette based on size and deformability, allowing it to retain a broader range of CTC phenotypes, including those with low EpCAM expression. Consequently, Parsortix® can potentially provide a more diverse snapshot of tumor cell populations, while CellSearch® offers a well-established, standardized approach for EpCAM-positive CTCs. Both platforms can be useful in clinical and research settings for monitoring metastatic disease and guiding therapy decisions.

In addition, a variety of emerging approaches exist to detect CTCs in breast cancer beyond established immunomagnetic or size-based systems. Methods like RosetteSep™ enrichment [12] and filtration-based microfluidic devices [13] can capture CTCs directly from whole blood, whereas aptamer-mediated target-induced strand displacement in serum [14] and a DHA-modified, HIF-1-stimulated, fluorometric aptamer-conjugated AuNPs platform [15]offer additional molecular targeting capabilities. Other techniques include a PGK1/G6PD-based metabolic typing approach for GM + CTC detection[16], the CytoSorter® for CTC enumeration [17, 18], and real-time methylation-specific PCR to assess ESR1 methylation in EpCAM + CTCs and plasma ctDNA [19]. These diversified strategies highlight the pursuit of more comprehensive and sensitive CTC detection to improve disease monitoring and therapy guidance.

Detection platforms for ctDNA in breast cancer liquid biopsy

ctDNA is a valuable biomarker originating from cell-free DNA (cfDNA) released by tumor cells into the bloodstream. These fragments, typically 160 to 200 base pairs long, can comprise between 0.01% and 90% of the total cfDNA. ctDNA has significant advantages over traditional tumor tissue analysis, as it better reflects tumor heterogeneity. With a short half-life of 15 min to 2.5 h—much shorter than blood protein biomarkers, which can last weeks—ctDNA serves as a real-time indicator of tumor dynamics, providing an up-to-date view of disease progression [13]. The ctDNA tumor fraction (TF) represents the proportion of ctDNA in a liquid biopsy sample, distinguishing it from normal cfDNAs [43–48]. Numerous emerging studies have verified that ctDNA tumor fraction can enhance diagnostic accuracy, improve treatment precision, and optimize patient outcomes [43–49].

Two powerful technologies, PCR and NGS, offer distinct advantages for the detection and analysis of ctDNA. PCR provides superior sensitivity and specificity for the identification of known mutations or specific genetic alterations within ctDNA. This technique can reliably detect and quantify even minute amounts of ctDNA, making it an invaluable tool for monitoring disease progression or evaluating treatment response. On the other hand, NGS enables the identification of novel mutations, and the comprehensive profiling of genetic alterations present in ctDNA. This technology allows for the detection of previously unknown or rare mutations, providing insights into tumor heterogeneity and potential therapeutic targets [50].

Guardant360 CDx for ctDNA detection

Guardant360 is an FDA-approved liquid biopsy assay developed by Guardant Health that utilizes NGS for comprehensive genomic profiling of ctDNA [20]. This assay can detect multiple biomarkers, such as EGFR and PIK3CA mutations, which are particularly relevant in breast cancer. It is especially effective in identifying PIK3CA mutations in patients with HR+ /HER2- metastatic breast cancer (MBC), aiding therapy selection for treatments like alpelisib (Piqray). Additionally, a study analyzed samples from two phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04497116 and NCT04972110) that examined the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related kinase inhibitor camonsertib in combination with gemcitabine and various PARP inhibitors (including talazoparib, niraparib, and olaparib). The Guardant360 platform assesses over 800 genomic targets along with 15 Mb of epigenomic targets from cell-free DNA and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Its methylation-based analysis of ctDNA enhances the monitoring of treatment responses within larger patient cohorts, potentially minimizing signal contamination from clonal hematopoiesis [51]. By providing a non-invasive method to profile the molecular landscape of tumors, Guardant360 facilitates therapy selection, monitors treatment responses, and detects emerging resistance.

FoundationOne® liquid CDx for ctDNA detection

FoundationOne is an FDA-approved, NGS–based platform developed by Foundation Medicine for comprehensive genomic profiling of solid tumors [21, 22]. In addition to tissue-based testing (FoundationOne CDx), the platform offers a blood-based assay (FoundationOne Liquid CDx) capable of analyzing ctDNA. By detecting a broad range of genomic alterations—including single-nucleotide variants, insertions or deletions, copy number changes, and select rearrangements—FoundationOne helps clinicians make more personalized treatment decisions and monitor resistance in real time. It is a comprehensive liquid biopsy platform for detecting ctDNA and, like Guardant360, focuses on biomarker-associated mutations—such as PIK3CA—that are highly relevant for breast cancer. Furthermore, it provides detailed tumor profiles to guide precision medicine approaches and optimize patient care. The IMAGE II study (NCT02965755) is a prospective multicenter trial assessing the clinical utility of ctDNA, detected by FoundationOne® Liquid CDx, alongside tissue biopsies in MBC. Results show that ctDNA offers more comprehensive genomic information than traditional tissue biopsies, enabling better monitoring of clinical responses and resistance. Enrolling 199 patients, the study found significant correlations between ctDNA tumor fraction detection rates, metastasis sites, and receptor subtypes [52]. Multiple studies showed that FoundationOne® Liquid CDx allows for easy genomic data acquisition via blood samples, supporting personalized treatment approaches [53–56].

Signatera test for ctDNA detection

Prominent examples of ctDNA-based diagnostic tests include the Signatera test, which is specifically designed to identify molecular residual disease and monitor recurrence in solid tumors [50]. These approvals underscore the growing recognition of ctDNA as a valuable biomarker in cancer management [23, 24]. The test not only facilitates early diagnosis of tumor status but also offers multiple approaches to assess prognosis and monitor for disease recurrence or metastasis.

One study investigates the relationship between ctDNA metrics—specifically, mean tumor molecules per milliliter (MTM/ml) and mean variant allele frequency (mVAF)—and tumor burden in patients with solid tumors [57]. Utilizing the Signatera™ ctDNA assay, the research shows that MTM/ml serves as a more accurate and predictive measure of tumor dynamics, particularly in cases with elevated cfDNA levels. This finding supports enhanced clinical decision-making in cancer treatment.

Tempus xF liquid biopsy assay for ctDNA detection

The Tempus xF liquid biopsy assay is a groundbreaking tool utilized in the detection of circulating ctDNA for breast cancer patients, providing a non-invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies [58]. Utilizing a comprehensive 105-gene NGS panel, the Tempus xF assay enables the identification of actionable mutations with high sensitivity and specificity, crucial for personalized treatment strategies. This assay excels in capturing tumor heterogeneity, particularly beneficial in metastatic cancer cases where multiple mutations may exist [59]. Furthermore, its integration of advanced algorithms, such as the Off-Target Tumor Estimation Routine (OTTER), enhances the estimation of tumor fractions in cell-free DNA, thereby improving clinical decision-making. The Tempus xF assay has shown remarkable efficacy in real-time disease monitoring and has been validated to outperform other commercial ctDNA testing methods, making it a promising option for improving outcomes in breast cancer management [60]. A study utilized real-world data to examine the combined impact of acquired ESR1 mutation status and ctDNA TF dynamics on overall survival in ER+ HER2-negative MBC patients [61]. Tempus xF Monitor enables early therapeutic interventions, allowing for a timely switch to alternative treatments. This approach is particularly beneficial for improving outcomes in a patient population characterized by poor prognosis.

A range of technologies exist for detecting ctDNA in breast cancer. MammaPrint in plasma can be used for monitoring therapeutic response and recurrence [25], while Pyrosequencing of plasma can identify gene methylation changes, such as SPAG6, PER1, and NKX2-6 [28]. Droplet-digital PCR (ddPCR) and dPCR-SEQ enable close tracking of treatment resistance [29–31], and whole-genome amplification and NGS quantify cfDNA in whole blood [36].

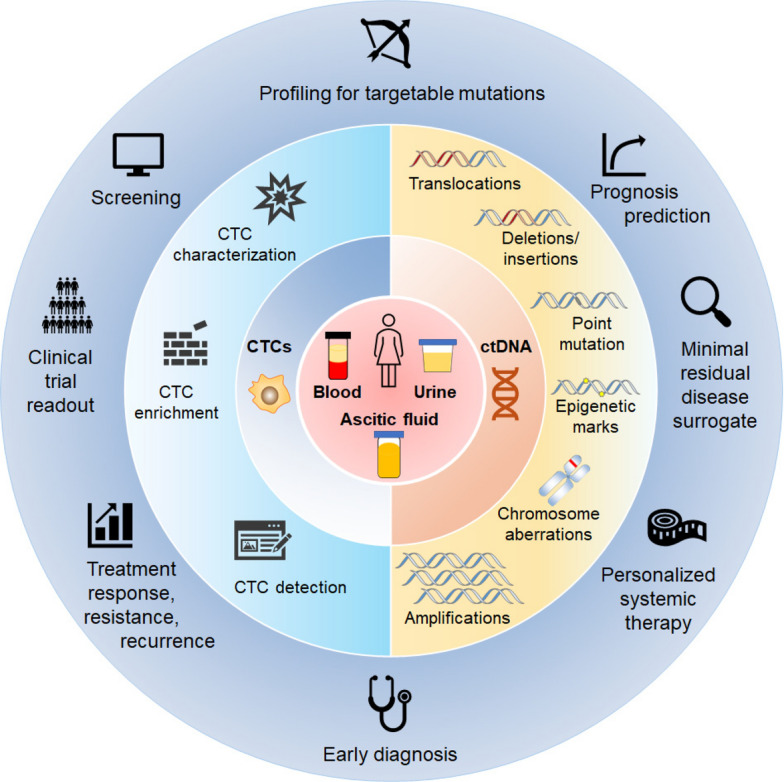

Clinical applications of CTCs in breast cancer liquid biopsy

To review the clinical applications of CTCs and ctDNA in breast cancer liquid biopsy, the related clinical trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov were summarized in Table S1. Almost 300 clinical trials have been generated to investigate the roles and effects of CTCs and ctDNA in breast cancer liquid biopsies. Liquid biopsy has been assiduously integrated into clinical practice in recent years, as illustrated in Fig. 2, offering a valuable chance to improve treatment outcomes and increase survival rates for those suffering from breast cancer [62].

Fig. 2.

The clinical potential of CTCs and ctDNA in blood, urine, and ascitic fluid for the early diagnosis, prognostic assessment, monitoring of treatment response, and surveillance of recurrence and metastasis in breast cancer

CTCs in breast cancer characterization

CTCs served as biomarkers for breast cancer characterization, as well as prognostic indicators for long-term outcomes based on their presence before treatment and their clearance during early treatment phases. In 2020, Lisa Rydén and colleagues conducted a clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01322893) on the distribution and prognostic value of CTCs detected by CellSearch system in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) and no special type (NST) with metastatic disease [63]. The study involved 28 ILC and 111 NST patients and used the CellSearch system to evaluate CTCs. They found that ILC cases had more CTCs and CTC clusters before starting first-line systemic treatment than NST cases, suggesting a higher CTC threshold might be needed for metastatic ILC [64]. Furthermore, the elimination of CTCs within three months indicated positive long-term outcomes in both ILC and NST cases.

CTCs in predicting outcomes and monitoring treatment response

One of the key applications of CTCs is in predicting outcomes and monitoring treatment response in MBC. The presence of CTCs at the start of treatment and their persistence during therapy have been linked to shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in MBC patients [65, 66]. For example, a metabolic classification method for CTCs based on PGK1/G6PD (GM + CTCs) and found that high metabolically active CTCs are closely linked to distant metastasis and poorer progression-free survival in patients. This suggests that GM + CTCs can serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting metastasis and monitoring treatment response in breast cancer patients [47].

CTC counts in breast cancer treatment decision-making

CTC count has also been associated with prognosis and estimated benefit from chemotherapy for early-stage hormone receptor positive breast cancers. The SWOG S0500 trial aimed to determine if modifying chemotherapy based on elevated CTC levels (≥ 5 CTCs/7.5 mL) after three weeks could improve OS in MBC. Results indicated that while high CTC counts correlate with a worse prognosis, changing therapy may not alter the disease course (NCT00382018) [67]. Additionally, METABREAST research (NCT01710605) suggested that low CTC counts can help identify patients who may not require intensive treatment. This trial assigned MBC patients to treatment based on CTC counts, revealing a median progression-free survival of 15.5 months in the CTC arm versus 13.9 months in the conventional arm. Importantly, the METABREAST trial established CTCs as an informative biomarker for selecting therapies in HR+ , HER2− MBC patients [68]. These studies highlight the potential of CTC analysis as a valuable tool in breast cancer management.

CTCs in cancer recurrence monitoring and risk stratification

CTCs play a vital role in monitoring cancer recurrence and guiding personalized treatment strategies. Identifying high-risk patients for relapse is challenging, but single-cell profiling of CTCs shows changes in hormone receptor expression as tumors evolve [69]. CTC counts of 1–10 per 7.5 ml of blood correlate with lower OS and DFS and predict poor relapse-free survival (RFS) in chemotherapy patients. Positive tests for circulating cancer cells (CCC) indicate higher metastatic risk, with counts increasing from 2 in stage 1–1283 in stage 4 breast cancer [70]. Overall, CTC analysis suggests that liquid biomarkers can effectively stratify late recurrence risks and inform personalized therapy.

Clinical applications of ctDNA in breast cancer liquid biopsy

For breast cancer, ctDNA detected in blood, ascitic fluid and urine can be used for non-invasive assessment of tumor genomes and quantification of tumor burden [14–16, 36]. That certain mutations found in ctDNA were previously only detectable in primary tumor tissue. Differentiating ctDNA from benign cfDNA has largely depended on advancements in DNA sequencing technology. Thanks to recent improvements in the sensitivity and accuracy of DNA analysis, ctDNA genotyping for somatic genetic mutations observed in biofluids is now possible [71]. Recent studies identified that genetic alterations such as TP53 and PIK3CA mutations are detectable via ctDNA assessment, have been linked to breast cancer growth and progression and are considered potentially treatable [72]. Additionally, promoter methylation of breast cancer-related genes, including APC, BRCA1, ER1, GSTP1, HIN1, RARβ, RASSF1, and TWIST, have been detected in analysis of cfDNA in patients with breast cancer [2].

Because ctDNA is a double-stranded nucleic acid that tumor cells release into the bloodstream, all of the genetic material present in the tumor tissue is included in it. Genetic abnormalities such as somatic single nucleotide variations (SNVs), copy number alterations (CNAs), and structural variants (SVs) have been demonstrated in the ctDNA of breast cancer patients [73]. Additionally, these particular genomic alterations aid in distinguishing ctDNA from normal cfDNA. These somatic mutations are absent from the same person’s normal cellular DNA and only appear in the genome of cancer cells.

ctDNA in early screening and identification of breast cancer

ctDNA analysis has demonstrated promise for early screening and identification of breast cancer in its early stages. Early research has shown that ctDNA can identify somatic PIK3CA and TP53 mutations in patients with early-stage breast cancer [74]. Researchers led by María Isabel Queipo-Ortuño discovered a tendency for individuals exhibiting clinical traits linked to more aggressive disease variables to have a higher burden of plasma ctDNA mutations. These variables include the immunohistochemical subtype, bigger tumor size, BIRADS category 5, higher tumor grade (grade II–III), and the presence of positive lymph nodes. The most often mutated tumors were luminal A tumors, then luminal B malignancies. Additionally, promoter methylation patterns in ctDNA of genes such as NKX26, PER1, and SPAG6 have been investigated as possible blood-based biomarkers for early diagnosis [75]. The c-TRAK TN trial further underscores the potential of ctDNA as a biomarker for early detection of molecular residual disease in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [76]. This prospective, multi-center phase II study demonstrated the feasibility of using ctDNA to guide therapeutic decisions in early-stage, high-risk TNBC patients. While the trial showed promise in identifying patients with molecular residual disease through ctDNA analysis, challenges were noted in achieving sustained ctDNA clearance with current treatments like pembrolizumab. A study focuses on the utility of the Guardant360 assay and FoundationOneLiquid assay for detecting ctDNA, and its implications in understanding tumor burden through the ctDNA TF. Higher ctDNA TF significantly improves the agreement between liquid biopsy results and tissue biopsy findings for driver mutations. When the TF was ≥ 1%, the positive percent agreement increased from 63 to 98%, and the negative predictive value improved from 66 to 97%. Patients with negative liquid biopsy results and a TF ≥ 1% may be candidates for immediate treatment initiation, while those with TF < 1% should undergo tissue testing, as they are more likely to have actionable mutations [77]. Overall, the findings emphasize the potential of ctDNA TF in guiding clinical decision-making, particularly in the management of cancer patients.

Longitudinal monitoring of ctDNA dynamics for early predictions of treatment efficacy

Longitudinal monitoring of ctDNA dynamics during treatment can provide early predictions of treatment efficacy, with ctDNA clearance or suppression indicating favorable response [78]. Baseline ctDNA levels and specific gene alterations, such as high ctDNA TF, TP53 and PIK3CA mutations, have been associated with inferior PFS and OS [78, 79]. Miguel Martín and colleagues found that the presence of plasma TP53 mutations was associated with impaired PFS in patients with HR+ and HER2− MBC, regardless of whether they received endocrine therapy or chemotherapy. Additionally, their results imply that these patients may experience long-term negative consequences as a result of having plasma ESR1 mutations. This study suggested that early ctDNA TF suppression could be a helpful clinical predictor of long-term therapy outcomes [78, 79]. The longitudinal ctDNA analysis from the MONALEESA-ASIA trial demonstrated that higher baseline ctDNA levels, along with the presence of PIK3CA and TP53 alterations, were associated with poorer outcomes in patients receiving ribociclib plus endocrine therapy. Furthermore, on-treatment ctDNA dynamics reflected treatment response patterns, highlighting the potential utility of ctDNA monitoring in guiding treatment decisions [78, 79]. These studies highlight the promising role of ctDNA analysis in the management of MBC by demonstrating that early suppression of ctDNA may be clinically useful for predicting long-term treatment efficacy and identifying patients who may benefit the most from particular treatment approaches.

ctDNA in molecular profiling and targeted therapy selection

Molecular profiling of ctDNA can guide targeted therapy selection in MBC. ESR1 mutations in ctDNA have been linked to resistance to endocrine therapies like aromatase inhibitors, identifying patients who may benefit from alternative treatments. A study looking into the appearance of ESR1 mutations in breast cancer patients at various stages of the disease course was carried out by Einav Nili Gal-Yam and colleagues [80]. Four out of five ESR1 mutations in newly diagnosed metastatic patients happened in those using tamoxifen (TAM) alone. The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease who were treated with aromatase inhibitors and had ESR1 mutations was considerably lower. Of the patients in the local recurrence group, 36% had ESR1 mutations, but only 10% had an allele frequency higher than 1%. In the local recurrence cohort, individuals on TAM monotherapy had the majority of ESR1 mutations found in them. This work emphasizes that early on in both local and metastatic recurrence, clonal selection for hotspot ESR1 mutations can take place. These mutations may appear following or during neoadjuvant endocrine treatment of primary tumors, adjuvant endocrine therapy, including single-agent TAM. The presence of ESR1 mutations was associated with inferior outcomes, emphasizing their potential role as a predictive biomarker for endocrine therapy resistance.

ctDNA in real-time monitoring and therapeutic

Treatment selection and monitoring characterizing the mutational profile of a patient’s tumor from ctDNA can help guide targeted therapy selection. For instance, when treated with the aromatase inhibitors exemestane and everolimus, patients with MBC who had ESR1 mutations identified in their ctDNA at baseline had a worse PFS than those who did not, according to the BOLERO-2 trial (NCT00863655), indicating that ESR1 mutations confer resistance to this therapy [80]. The PADA-1 trial exemplifies the clinical utility of ctDNA monitoring in guiding treatment decisions for breast cancer patients. This pivotal phase 3 study, conducted across 83 French hospitals, investigated the impact of early therapeutic intervention based on detecting rising ESR1 mutations in blood (bESR1mut) among patients with ER+ , HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. By monitoring ctDNA for rising bESR1mut, researchers identified patients who might benefit from an early switch in endocrine therapy before clinical progression occurred [62]. In the MONALEESA-2 trial (NCT01958021) of ribociclib plus letrozole, patients with PIK3CA mutations in ctDNA at baseline had shorter median PFS compared to those with wildtype PIK3CA (12.7 vs 19.2 months) [81]. The PEARL trial (NCT02028507) also showed that detectable TP53 mutations in baseline ctDNA were associated with worse outcomes in metastatic HR+/HER2− patients treated with either palbociclib/fulvestrant or capecitabine [82]. This strategy demonstrated the feasibility of using liquid biopsy for real-time monitoring and therapeutic intervention, highlighting how ctDNA analysis can enable more personalized treatment approaches.

ctDNA alterations for resistance assessing and treatment response monitoring

Serial ctDNA monitoring can also track treatment response and detect emerging resistance mutations. The MONALEESA trials (NCT01958021, NCT02422615, NCT02278120) highlights the importance of genomic profiling to identify molecular alterations in ctDNA and correlate these with treatment efficacy. Alterations in genes like ERBB2, FAT3, FRS2, MDM2, SFRP1, and ZNF217 were associated with increased sensitivity to ribociclib, while others like ANO1, CDKN2A/2B/2C, and RB1 were linked to resistance [81]. In the I-SPY 2 trial (NCT01042379) for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, early clearance of ctDNA 3 weeks after starting treatment predicted pathologic complete response in triple-negative but not HR+/HER2− breast cancer patients [83]. Studies have shown that certain TF thresholds are predictive of clinical outcomes. For instance, a TF of ≥ 10% has been linked to nearly 100% sensitivity for detecting actionable mutations in breast cancer [56]. This predictive capability can guide therapeutic strategies and help in the early identification of patients who may benefit from alternative treatments. These examples highlight the use of genomic profiling to correlate ctDNA alterations with drug sensitivity or resistance, and in some cases predicting treatment outcomes.

ctDNA for evaluating the efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors

Early dynamics in ctDNA levels could potentially serve as a robust biomarker for evaluating the efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors. Notably, these early ctDNA dynamics may reveal divergent responses among tumor subclones to the administered treatment, highlighting the potential for monitoring clonal evolution and resistance mechanisms. Early alterations in the ctDNA dynamics of advanced ER+ breast cancer showed promise in phase III PALOMA-3 study for offering information about treatment effectiveness. After receiving palbociclib and fulvestrant for 15 days, the study discovered that a decrease in PIK3CA ctDNA levels relative to baseline was indicative of PFS [84].

Challenges of CTCs and ctDNA detection in liquid biopsy for breast cancer

Liquid biopsy, which involves the analysis of CTCs and ctDNA in blood or other body fluids, has emerged as a promising non-invasive approach for breast cancer diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment selection.

However, the detection of CTCs and ctDNA presents several significant challenges. Firstly, these biomarkers are present in extremely low concentrations in the bloodstream, with CTCs occurring as few as 1–10 cells per billion normal blood cells and ctDNA being diluted by large amounts of cell-free DNA from normal cells. This challenge is compounded by the fact that, in early-stage breast cancer, there is insufficient clinical trial data to determine how the detection of these biomarkers should guide therapy modifications or whether they surpass imaging for recurrence detection. Several clinical trials (NCT00263211, NCT01939483, NCT02774681, etc.) have been terminated as the low actual detection of CTCs or ctDNA.

Secondly, breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease, and the molecular profiles of CTCs and ctDNA may not fully represent the tumor’s complexity, potentially leading to false-negative results or incomplete characterization. It is particularly difficult to detect and quantify these biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity in early-stage and low-burden diseases, where false-positive results can miss important therapeutic targets and false-negative results can result in needless treatment. Additionally, various techniques such as immunocapture, microfluidics, PCR-based methods, and Next-generation sequencing (NGS) are used for CTC and ctDNA detection. The lack of standardized methodologies and analytical platforms for these liquid biopsy assays complicates the comparison of results across different studies and clinical settings. Furthermore, liquid biopsies may not capture the full extent of tumor heterogeneity, as they represent a snapshot of the tumor at a particular time point [40].

Despite these challenges, liquid biopsies offer a significant advantage over traditional tissue biopsies by providing more detailed information about tumor heterogeneity. As mentioned earlier, they can capture the diverse molecular profile of tumors more effectively, which is crucial in breast cancer management. Ongoing research efforts are paving the way for their future development and widespread adoption. Technological advancements, such as microfluidic devices, digital PCR, and NGS, are improving the sensitivity and specificity of CTC and ctDNA detection [85]. Furthermore, using machine learning and artificial intelligence could improve the detection and use of predictive and prognostic biomarkers.

Conclusion

Liquid biopsy using CTCs and ctDNA has emerged as a potential approach to further personalize breast cancer management. The analysis of these circulating biomarkers provides invaluable insights into tumor biology, heterogeneity, and treatment response, complementing the limitations of traditional tissue biopsies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CTCs

Circulating tumor cells

- ctDNA

Circulating tumor DNA

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- DB

Draining vein blood

- PB

Peripheral blood

- MBC

Metastatic breast cancer

- HR

Hormone receptor

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- CK

Cytokeratin

- EpCAM

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- SNV

Single nucleotide variation

- CNA

Copy number alteration

- SV

Structural variant

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- TMB

Tumor mutational burden

- TAM

Tamoxifen

- ABC

Advanced breast cancer

Author contributions

The work reported in the article has been performed by the authors unless clearly specified in the text. G.-J. Y., X. L. and H.-J. Z. conceived the project, provided directions and wrote the manuscript. Y. Z. and S. C. helped to draw the figures. W. S. helped to check the whole manuscript. The final manuscript has been approved by all authors.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82204482), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (China) (No. 2024A1515010167), Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (China) (2023A03J0616 and 2024A04J9918), Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CACM (China) (No. 2021-QNRC2-B22), Key Laboratory of Prevention, Diagnosis and Therapy of Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer of Zhejiang Province (2022SXHD0003), Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province for Traditional Chinese Medicine Regimen and Health & Key Laboratory of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine for Scientific Research & Industrial Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine Regimen and Health (China) (GZ2022003) and the Tertiary Education Scientific research project of Guangzhou Municipal Education Bureau (No. 2024312331), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY24C190001), the One health Interdisciplinary Research Project, Ningbo University (HZ202201).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hai-Jing Zhong, Email: hjzhong@jnu.edu.cn.

Xiaoxu Liang, Email: liangxxu@126.com.

Guan-Jun Yang, Email: champion2014@126.com.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw JA, Guttery DS, Hills A, Fernandez-Garcia D, Page K, Rosales BM, Goddard KS, Hastings RK, Luo J, Ogle O, et al. Mutation analysis of cell-free DNA and single circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients with high circulating tumor cell counts. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:88–96. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-16-0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basik M, Aguilar-Mahecha A, Rousseau C, Diaz Z, Tejpar S, Spatz A, Greenwood CMT, Batist G. Biopsies: next-generation biospecimens for tailoring therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:437–50. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huebner H, Fasching PA, Gumbrecht W, Jud S, Rauh C, Matzas M, Paulicka P, Friedrich K, Lux MP, Volz B, et al. Filtration based assessment of CTCs and Cell Search® based assessment are both powerful predictors of prognosis for metastatic breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:204. 10.1186/s12885-018-4115-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirix L, Buys A, Oeyen S, Peeters D, Liègeois V, Prové A, Rondas D, Vervoort L, Mariën V, Laere SV, et al. Circulating tumor cell detection: a prospective comparison between Cell Search® and RareCyte® platforms in patients with progressive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;193:437–44. 10.1007/s10549-022-06585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Hong R, Shi S, Wang S, Chen Y, Han C, Li M, Ye F. The prognostic significance of circulating tumor cell enumeration and HER2 expression by a novel automated microfluidic system in metastatic breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:1067. 10.1186/s12885-024-12818-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darlix A, Cayrefourcq L, Pouderoux S, Menjot N, de Champfleur A, Bievelez WJ, Leaha C, Thezenas S, Alix-Panabières C. Detection of circulating tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with suspected breast cancer leptomeningeal metastases: a prospective study. Clin Chem. 2022;68:1311–22. 10.1093/clinchem/hvac127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciccioli M, Kim K, Khazan N, Khoury JD, Cooke MJ, Miller MC, O’Shannessy DJ, Pailhes-Jimenez A-S, Moore RG. Identification of circulating tumor cells captured by the FDA-cleared Parsortix® PC1 system from the peripheral blood of metastatic breast cancer patients using immunofluorescence and cytopathological evaluations. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:240. 10.1186/s13046-024-03149-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciccioli M, Moore R, Kim KK, Khazan N, Miller MC, Pailhes-Jimenez A-S. Identification of circulating tumor cells captured by the FDA cleared parsortix® PC1 system from the peripheral blood of metastatic breast cancer patients using immunofluorescence and cytopathological evaluations. Cancer Res. 2023. 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs22-p1-05-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen E, Jayachandran G, Moore R, Cristofanilli M, Lang JE, Khoury J, Press MF, McBride H, Kim KK, Khazan N, et al. A multi-center clinical study to harvest and characterize circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic breast cancer using the parsortix® PC1 system in support of FDA clearance. Cancer Res. 2023. 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs22-p5-06-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciccioli M, Young A, Vlietinck L, Johnson C, Pailhes-Jimenez A-S. Development and analytical validation of a novel assay for HER2 assessment on circulating tumor cells using Parsortix® isolation and BioView imaging technologies. Cancer Res. 2024;84:3705. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2024-3705. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miklikova S, Minarik G, Sedlackova T, Plava J, Cihova M, Jurisova S, Kalavska K, Karaba M, Benca J, Smolkova B, et al. Inflammation-based scores increase the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in primary breast cancer. Cancers. 2020;12:1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattori M, Nakanishi H, Yoshimura M, Iwase M, Yoshimura A, Adachi Y, Gondo N, Kotani H, Sawaki M, Fujita N, et al. Circulating tumor cells detection in tumor draining vein of breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18195. 10.1038/s41598-019-54839-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Zhang P, Dou L, Wang Y, Sun K, Zhang X, Song G, Zhao C, Li K, Bai Y, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients by nanopore sensing with aptamer-mediated amplification. ACS Sensors. 2020;5:2359–66. 10.1021/acssensors.9b02537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia W, Shangguan X, Li M, Wang Y, Xi D, Sun W, Fan J, Shao K, Peng X. Ex vivo identification of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood by fluorometric “turn on” aptamer nanoparticles. Chem Sci. 2021;12:3314–21. 10.1039/D0SC05112H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Ye C, Dong J, Cao S, Hu Y, Situ B, Xi X, Qin S, Xu J, Cai Z, et al. Metabolic classification of circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for metastasis and prognosis in breast cancer. J Transl Med. 2020;18:59. 10.1186/s12967-020-02237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInnes LM, Jacobson N, Redfern A, Dowling A, Thompson EW, Saunders CM. Clinical implications of circulating tumor cells of breast cancer patients: role of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity. Front Oncol. 2015;5:42. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radovich M, Jiang G, Hancock BA, Chitambar C, Nanda R, Falkson C, Lynce FC, Gallagher C, Isaacs C, Blaya M, et al. Association of circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with disease recurrence in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: preplanned secondary analysis of the BRE12-158 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1410–5. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastoraki S, Strati A, Tzanikou E, Chimonidou M, Politaki E, Voutsina A, Psyrri A, Georgoulias V, Lianidou E. ESR1 Methylation: a liquid biopsy-based epigenetic assay for the follow-up of patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving endocrine treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1500–10. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okines AFC, Curigliano G, Mizuno N, Oh D-Y, Rorive A, Soliman H, Takahashi S, Bekaii-Saab T, Burkard ME, Chung KY, et al. Tucatinib and trastuzumab in HER2-mutated metastatic breast cancer: a phase 2 basket trial. Nat Med. 2025. 10.1038/s41591-024-03462-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivakumar S, Jin DX, Tukachinsky H, Murugesan K, McGregor K, Danziger N, Pavlick D, Gjoerup O, Ross JS, Harmon R, et al. Tissue and liquid biopsy profiling reveal convergent tumor evolution and therapy evasion in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7495. 10.1038/s41467-022-35245-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasseur D, Arbab A, Giudici F, Marzac C, Michiels S, Tagliamento M, Bayle A, Smolenschi C, Sakkal M, Aldea M, et al. Genomic landscape of liquid biopsy mutations in TP53 and DNA damage genes in cancer patients. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8:51. 10.1038/s41698-024-00544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutts R, Ulrich L, Beaney M, Robert M, Coakley M, Bunce C, Crestani GW, Hrebien S, Kalashnikova E, Wu HT, et al. Association of post-operative ctDNA detection with outcomes of patients with early breast cancers. ESMO Open. 2024;9: 103687. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw JA, Page K, Wren E, Bruin ECd, Kalashnikova E, Hastings R, McEwen R, Zhang E, Wadsley M, Acheampong E, et al. Serial postoperative circulating tumor DNA assessment has strong prognostic value during long-term follow-up in patients with breast cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2024. 10.1200/po.23.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magbanua MJM, Rugo H, Swigart LAB, Ahmed Z, Hirst GL, Wolf DM, Lu R, Kalashnikova E, Renner D, Rodriguez A, et al. Abstract P5–05–05: Monitoring for response and recurrence in neoadjuvant-treated hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative breast cancer by personalized circulating tumor DNA testing. Cancer Res. 2023. 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs22-p5-05-05. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakauchi C, Kagara N, Shimazu K, Shimomura A, Naoi Y, Shimoda M, Kim SJ, Noguchi S. Detection of TP53/PIK3CA mutations in cell-free plasma DNA from metastatic breast cancer patients using next generation sequencing. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16:418–23. 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen TW-W, Hsiao W, Dai M-S, Lin C-H, Chang D-Y, Chen IC, Wang M-Y, Chang S-H, Huang S-M, Cheng A-L, et al. Plasma cell-free tumor DNA, PIK3CA and TP53 mutations predicted inferior endocrine-based treatment outcome in endocrine receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2023;201:377–85. 10.1007/s10549-023-06967-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mijnes J, Tiedemann J, Eschenbruch J, Gasthaus J, Bringezu S, Bauerschlag D, Maass N, Arnold N, Weimer J, Anzeneder T, et al. SNiPER: a novel hypermethylation biomarker panel for liquid biopsy based early breast cancer detection. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6494–508. 10.18632/oncotarget.27303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakai M, Yamada T, Sekiya K, Sato A, Hankyo M, Kuriyama S, Takahashi G, Kurita T, Yanagihara K, Yoshida H, et al. PIK3CA mutation detected by liquid biopsy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. JNMS. 2021. 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Lindsay D, Chen QB, Garrett AL, Tan XM, Anders CK, Carey LA, Gupta GP. Tracking plasma DNA mutation dynamics in estrogen receptor positive metastatic breast cancer with dPCR-SEQ. npj Breast Cancer. 2018;4:39. 10.1038/s41523-018-0093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corné J, Quillien V, Godey F, Cherel M, Cochet A, Le Du F, Robert L, Bourien H, Brunot A, Crouzet L, et al. Plasma-based analysis of ERBB2 mutational status by multiplex digital PCR in a large series of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2024;18:2714–29. 10.1002/1878-0261.13592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma S, Zhou M, Xu Y, Gu X, Zou M, Abudushalamu G, Yao Y, Fan X, Wu G. Clinical application and detection techniques of liquid biopsy in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:7. 10.1186/s12943-023-01715-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gennari A, Foca F, Zamarchi R, Rocca A, Amadori D, De Censi A, Bologna A, Cavanna L, Gianni L, Scaltriti L, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) expression on circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and metastatic breast cancer outcome: results from the TransMYME trial. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2020;181:61–8. 10.1007/s10549-020-05596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martínez-Sáez O, Pascual T, Brasó-Maristany F, Chic N, González-Farré B, Sanfeliu E, Rodríguez A, Martínez D, Galván P, Rodríguez AB, et al. Circulating tumor DNA dynamics in advanced breast cancer treated with CDK4/6 inhibition and endocrine therapy. npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7:8. 10.1038/s41523-021-00218-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alba-Bernal A, Godoy-Ortiz A, Domínguez-Recio ME, López-López E, Quirós-Ortega ME, Sánchez-Martín V, Roldán-Díaz MD, Jiménez-Rodríguez B, Peralta-Linero J, Bellagarza-García E, et al. Increased blood draws for ultrasensitive ctDNA and CTCs detection in early breast cancer patients. npj Breast Cancer. 2024;10:36. 10.1038/s41523-024-00642-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shishido SN, Welter L, Rodriguez-Lee M, Kolatkar A, Xu L, Ruiz C, Gerdtsson AS, Restrepo-Vassalli S, Carlsson A, Larsen J, et al. Preanalytical variables for the genomic assessment of the cellular and acellular fractions of the liquid biopsy in a cohort of breast cancer patients. J Mol Diagn. 2020;22:319–37. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa C, Muinelo-Romay L, Cebey-López V, Pereira-Veiga T. Analysis of a real-world cohort of metastatic breast cancer patients shows circulating tumor cell clusters (CTC-clusters) as predictors of patient outcomes. Cancers. 2020. 10.3390/cancers12051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin D, Shen L, Luo M, Zhang K, Li J, Yang Q, Zhu F, Zhou D, Zheng S, Chen Y, et al. Circulating tumor cells: biology and clinical significance. STTT. 2021;6:404. 10.1038/s41392-021-00817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang C, Xia B-R, Jin W-L, Lou G. Circulating tumor cells in precision oncology: clinical applications in liquid biopsy and 3D organoid model. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:341. 10.1186/s12935-019-1067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Liquid biopsy: from discovery to clinical application. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:858–73. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Venesio T, Marsoni S, Seoane J, Dive C, Papadopoulos N, Kopetz S, Corcoran RB, Siu LL, et al. How liquid biopsies can change clinical practice in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1580–90. 10.1093/annonc/mdz227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S, Zhang K, Tan S, Xin J, Yuan Q, Xu H, Xu X, Liang Q, Christiani DC, Wang M, et al. Circular RNAs in body fluids as cancer biomarkers: the new frontier of liquid biopsies. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:13. 10.1186/s12943-020-01298-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X, Cheng Z, Dong M, Liu Q, Yang W, Liu M, Tian J, Cheng W. Tumor fractions deciphered from circulating cell-free DNA methylation for cancer early diagnosis. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7694. 10.1038/s41467-022-35320-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber ZT, Collier KA, Tallman D, Forman J, Shukla S, Asad S, Rhoades J, Freeman S, Parsons HA, Williams NO, et al. Modeling clonal structure over narrow time frames via circulating tumor DNA in metastatic breast cancer. Genome Med. 2021;13:89. 10.1186/s13073-021-00895-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prat A, Brasó-Maristany F, Martínez-Sáez O, Sanfeliu E, Xia Y, Bellet M, Galván P, Martínez D, Pascual T, Marín-Aguilera M, et al. Circulating tumor DNA reveals complex biological features with clinical relevance in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2023;14:1157. 10.1038/s41467-023-36801-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reichert ZR, Morgan TM, Li G, Castellanos E, Snow T, Dall’Olio FG, Madison RW, Fine AD, Oxnard GR, Graf RP, et al. Prognostic value of plasma circulating tumor DNA fraction across four common cancer types: a real-world outcomes study. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:111–20. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.09.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shan NL, Gould B, Blenman K, Foldi J, Du P, Zhang F, Walsh M, Pusztai L. Abstract PO5–14–05: circulating tumor DNA fraction correlates with residual cancer burden post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2024. 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs23-po5-14-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald BR, Contente-Cuomo T, Sammut S-J, Odenheimer-Bergman A, Ernst B, Perdigones N, Chin S-F, Farooq M, Mejia R, Cronin PA, et al. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis to detect residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer. Sci Trans Med. 2019;11:eaax7392. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panet F, Papakonstantinou A, Borrell M, Vivancos J, Vivancos A, Oliveira M. Use of ctDNA in early breast cancer: analytical validity and clinical potential. npj Breast Cancer. 2024;10:50. 10.1038/s41523-024-00653-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trujillo B, Wu A, Wetterskog D, Attard G. Blood-based liquid biopsies for prostate cancer: clinical opportunities and challenges. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:1394–402. 10.1038/s41416-022-01881-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silverman I, Schonhoft J, Yablonovitch A, Lagow E, Cecchini M, Herzberg B, Reis-Filho J, Rosen E, Rimkunas V, Yap T. Performance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) genomic and epigenomic profiling (GuardantINFINITY) in the TRESR and ATTACC studies. J Liq Biopsy. 2023. 10.1016/j.jlb.2023.100014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linville LM, Canzoniero JV, Too F, Lombardo A, Malwankar J, Mawalkar R, Haile M, Zandi L, Babu V, Brown DW, et al. Utility of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) to inform treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1042. 10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.1042. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu D, Keller-Evans RB, Schrock AB, Drilon AE, Jee J, Li BT. Characterization of diverse targetable ERBB2 alterations in 512,993 patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:3129. 10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.3129. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhave MA, Quintanilha JCF, Tukachinsky H, Li G, Scott T, Ross JS, Pasquina L, Huang RSP, McArthur H, Levy MA, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of ESR1, PIK3CA, AKT1, and PTEN in HR(+)HER2(−) metastatic breast cancer: prevalence along treatment course and predictive value for endocrine therapy resistance in real-world practice. Breast Cancer Res Tr. 2024;207:599–609. 10.1007/s10549-024-07376-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McArthur H, Tukachinsky H, Schrock A, Madison R, Holmes O, Sivakumar S, Sokol E, Graf R, Quintanilha J, Dougherty K, et al. Abstract PO2–16–03: ESR1 genomic alterations (GAs) and coexistent putative resistance alterations in comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Cancer Res. 2024. 10.1158/1538-7445.Sabcs23-po2-16-03. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Husain H, Pavlick DC, Fendler BJ, Madison RW, Decker B, Gjoerup O, Parachoniak CA, McLaughlin-Drubin M, Erlich RL, Schrock AB, et al. Tumor fraction correlates with detection of actionable variants across > 23,000 circulating tumor DNA samples. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022. 10.1200/po.22.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalashnikova E, Aushev VN, Malashevich AK, Tin A, Krinshpun S, Salari R, Scalise CB, Ram R, Malhotra M, Ravi H, et al. Correlation between variant allele frequency and mean tumor molecules with tumor burden in patients with solid tumors. Mol Oncol. 2024;18:2649–57. 10.1002/1878-0261.13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finkle JD, Boulos H, Driessen TM, Lo C, Blidner RA, Hafez A, Khan AA, Lozac’hmeur A, McKinnon KE, Perera J, et al. Validation of a liquid biopsy assay with molecular and clinical profiling of circulating tumor DNA. npj Precis Oncol. 2021;5:63. 10.1038/s41698-021-00202-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iams WT, Mackay M, Ben-Shachar R, Drews J, Manghnani K, Hockenberry AJ, Cristofanilli M, Nimeiri H, Guinney J, Benson AB. Concurrent tissue and circulating tumor DNA molecular profiling to detect guideline-based targeted mutations in a multicancer cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2351700. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.51700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakamura Y, Kaneva K, Lo C, Neems D, Freaney JE, Boulos H, Hyun SW, Islam F, Yamada-Hanff J, Driessen TM, et al. A tumor-naïve ctDNA assay detects minimal residual disease in resected stage II or III colorectal cancer and predicts recurrence: subset analysis from the GALAXY study in CIRCULATE-Japan. Clin Cancer Res. 2025;31:328–38. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-24-2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein MM, Kaneva K, Hyun SW, Sangli C, Ting-Lin M, Ben-Shachar R, Freaney J, Sasser K, Guinney J, Nimeiri H, et al. Abstract 3676: a circulating tumor fraction DNA biomarker response stratified by ESR1 mutation status correlates with overall survival in patients with HR+ HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2024;84:3676. 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2024-3676. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bidard F-C, Hardy-Bessard A-C, Dalenc F, Bachelot T, Pierga J-Y, de la Motte RT, Sabatier R, Dubot C, Frenel J-S, Ferrero JM, et al. Switch to fulvestrant and palbociclib versus no switch in advanced breast cancer with rising <em>ESR1</em> mutation during aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib therapy (PADA-1): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1367–77. 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larsson A-M, Jansson S, Bendahl P-O, Levin Tykjaer Jörgensen C, Loman N, Graffman C, Lundgren L, Aaltonen K, Rydén L. Longitudinal enumeration and cluster evaluation of circulating tumor cells improve prognostication for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer in a prospective observational trial. Br Cancer Res. 2018;20:48. 10.1186/s13058-018-0976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Narbe U, Bendahl P-O, Aaltonen K, Fernö M, Forsare C, Jørgensen CLT, Larsson A-M, Rydén L. The distribution of circulating tumor cells is different in metastatic lobular compared to ductal carcinoma of the breast—long-term prognostic significance. Cells. 2020;9:1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costa C, Muinelo-Romay L, Cebey-López V, Pereira-Veiga T, Martínez-Pena I, Abreu M, Abalo A, Lago-Lestón RM, Abuín C, Palacios P, et al. Analysis of a real-world cohort of metastatic breast cancer patients shows circulating tumor cell clusters (CTC-clusters) as predictors of patient outcomes. Cancers. 2020;12:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hassanzadeh-Barforoushi A, Tsao SC-H, Nadalini A, Inglis DW, Wang Y. Rapid isolation and detection of breast cancer circulating tumor cells using microfluidic sequential trapping array. Adv Sens Res. 2024. 10.1002/adsr.202300206. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gasch C, Plummer PN, Jovanovic L, McInnes LM, Wescott D, Saunders CM, Schneeweiss A, Wallwiener M, Nelson C, Spring KJ, et al. Heterogeneity of miR-10b expression in circulating tumor cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15980. 10.1038/srep15980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bidard F-C, Jacot W, Kiavue N, Dureau S, Kadi A, Brain E, Bachelot T, Bourgeois H, Gonçalves A, Ladoire S, et al. Efficacy of circulating tumor cell count-driven versus clinician-driven first-line therapy choice in hormone receptor-positive, ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer: the STIC CTC randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:34–41. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keller L, Pantel K. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity by single-cell profiling of circulating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:553–67. 10.1038/s41568-019-0180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sparano J, O’Neill A, Alpaugh K, Wolff AC, Northfelt DW, Dang CT, Sledge GW, Miller KD. Association of circulating tumor cells with late recurrence of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1700–6. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seoane J, De Mattos-Arruda L, Le Rhun E, Bardelli A, Weller M. Cerebrospinal fluid cell-free tumour DNA as a liquid biopsy for primary brain tumours and central nervous system metastases. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:211–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdy544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cescon DW, Bratman SV, Chan SM, Siu LL. Circulating tumor DNA and liquid biopsy in oncology. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:276–90. 10.1038/s43018-020-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tukachinsky H, Madison RW, Chung JH, Gjoerup OV, Severson EA, Dennis L, Fendler BJ, Morley S, Zhong L, Graf RP, et al. Genomic analysis of circulating tumor DNA in 3,334 patients with advanced prostate cancer identifies targetable BRCA alterations and AR resistance mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3094–105. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jimenez Rodriguez B, Diaz Córdoba G, Garrido Aranda A, Álvarez M, Vicioso L, Llácer Pérez C, Hernando C, Bermejo B, Julve Parreño A, Lluch A, et al. Detection of TP53 and PIK3CA mutations in circulating tumor DNA using next-generation sequencing in the screening process for early breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Judes G, Rifaï K, Daures M, Dubois L, Bignon Y-J, Penault-Llorca F, Bernard-Gallon D. High-throughput «Omics» technologies: new tools for the study of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;382:77–85. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turner NC, Swift C, Jenkins B, Kilburn L, Coakley M, Beaney M, Fox L, Goddard K, Garcia-Murillas I, Proszek P, et al. Results of the c-TRAK TN trial: a clinical trial utilising ctDNA mutation tracking to detect molecular residual disease and trigger intervention in patients with moderate- and high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:200–11. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rolfo CD, Madison RW, Pasquina LW, Brown DW, Huang Y, Hughes JD, Graf RP, Oxnard GR, Husain H. Measurement of ctDNA tumor fraction identifies informative negative liquid biopsy results and informs value of tissue confirmation. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30:2452–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-23-3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pascual J, Gil-Gil M, Proszek P, Zielinski C, Reay A, Ruiz-Borrego M, Cutts R, Ciruelos Gil EM, Feber A, Muñoz-Mateu M, et al. Baseline mutations and ctDNA dynamics as prognostic and predictive factors in ER-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29:4166–77. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-23-0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiu J, Su F, Joshi M, Masuda N, Ishikawa T, Aruga T, Zarate JP, Babbar N, Balbin OA, Yap Y-S. Potential value of ctDNA monitoring in metastatic HR+ /HER2− breast cancer: longitudinal ctDNA analysis in the phase Ib MONALEESASIA trial. BMC Med. 2023;21:306. 10.1186/s12916-023-03017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zundelevich A, Dadiani M, Kahana-Edwin S, Itay A, Sella T, Gadot M, Cesarkas K, Farage-Barhom S, Saar EG, Eyal E, et al. ESR1 mutations are frequent in newly diagnosed metastatic and loco-regional recurrence of endocrine-treated breast cancer and carry worse prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:16. 10.1186/s13058-020-1246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.André F, Su F, Solovieff N, Hortobagyi G, Chia S, Neven P, Bardia A, Tripathy D, Lu YS, Lteif A, et al. Pooled ctDNA analysis of MONALEESA phase III advanced breast cancer trials. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:1003–14. 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pascual J, Gil-Gil M. Baseline mutations and ctDNA dynamics as prognostic and predictive factors in ER-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29:4166–77. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-23-0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Magbanua MJM, Brown Swigart L, Ahmed Z, Sayaman RW, Renner D, Kalashnikova E, Hirst GL, Yau C, Wolf DM, Li W, et al. Clinical significance and biology of circulating tumor DNA in high-risk early-stage HER2-negative breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1091-102.e4. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Leary B, Hrebien S, Morden JP, Beaney M, Fribbens C, Huang X, Liu Y, Bartlett CH, Koehler M, Cristofanilli M, et al. Early circulating tumor DNA dynamics and clonal selection with palbociclib and fulvestrant for breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:896. 10.1038/s41467-018-03215-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gao Q, Zeng Q, Wang Z, Li C, Xu Y, Cui P, Zhu X, Lu H, Wang G, Cai S, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA for cancer early detection. Innovation. 2022. 10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.