Abstract

Nitazenes are an emergent class of synthetic opioids that rival or exceed fentanyl in their potency. These compounds have been detected internationally in illicit drugs and are the cause of increasing numbers of hospitalizations and overdoses. New analogs are consistently released, making detection challenging – new ways of testing a wide range of nitazenes and their metabolic products are urgently needed. Here, we developed a computational protocol to redesign the plant abscisic acid receptor PYR1 to bind diverse nitazenes and maintain its dynamic transduction mechanism. The best design has a low nanomolar limit of detection in vitro against nitazene and menitazene. Deep mutational scanning yielded sensors able to recognize a range of clinically relevant nitazenes and the common metabolic byproduct in complex biological matrices with limited cross-specificity against unrelated opioids. Application of protein design tools on privileged receptors like PYR1 may yield general sensors for a wide range of applications in vitro and in vivo.

Introduction

The rise in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids has been well-documented in the US and worldwide, with prevalence rising in the 2010s to account for well over half of documented overdose deaths in the US in 2022 (1–3). Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl are inexpensive to produce and highly potent, with fentanyl 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin and morphine (2, 4), and thus are often mixed with other drugs to cheaply increase strength and addictivity (2, 3). An emerging class of novel synthetic opioids are 2-benzyl benzimidazole compounds known as nitazenes. First identified in the US and Canadian drug supply in 2019, nitazenes are considered 10 to 40 times more potent than fentanyl (5–8). Furthermore, the molecular structures of synthetic opioids, including nitazenes, are consistently altered to skirt laws banning known compounds (3, 7, 9). While commercial tests exist for fentanyl, including lateral flow assay test strips (10–12), there is an immediate need for diagnostic assays to detect the range of nitazenes in the drug supply, as well as nitazene metabolic byproducts to assist medical providers with patient care (13).

Diagnostic assays often contain a biomolecule to specifically recognize the drug(s). To develop nitazene biosensors, we chose to redesign the binding pocket of the plant abscisic acid (ABA) receptor PYR1 (14–16). PYR1 binds a phosphatase HAB1 in the presence of ABA through an allosteric gate-latch lock mechanism (17), representing a natural chemical induced dimerization (CID) module. This CID module presents a built-in transduction mechanism coupling protein interactions to a diverse range of signal outputs (16, 18, 19). This is additionally advantageous because the molecular ratchet mechanism of the PYR1-HAB1 CID allows highly sensitive readouts from lower affinity ligand-receptor pairs (14, 20). Immunoassays with antibodies or other binding molecules can be developed by brute force screening, but the relatively small surface area of drugs limits the affinity and ability to bind multiple related drug variants. While drug host receptors can be modified into a sensor (21), the same receptor can bind chemically dissimilar drugs, hampering unique identification of a drug class. Computational design has recently been used to create moderate affinity binders for largely apolar, rigid molecules (22–26). However, binders are not sensors: the transduction of the binding event into a measurable signal must typically be engineered for each bespoke design, limiting generality and throughput. In contrast, repurposing the PYR1 binding pocket, while keeping its transduction mechanism intact, promises to be a more generalizable solution.

In this study, we used computational design of the PYR1 binding pocket to identify biosensors suitable for detection of nitazenes and their byproducts. We used deep mutational scanning, directed evolution, and computational modeling to create a pan-nitazene sensor that can detect multiple nitazene derivatives, including the common variant isotonitazene and its 4-hydroxy nitazene byproduct. We then developed a luciferase-based in vitro diagnostic platform that is label-free, fast, sensitive, and can be performed in complex biological matrices like urine. The computational-experimental methodology represents a general way to rapidly develop biosensors to address the emergence of new synthetic opioids that can circumvent existing detection modalities.

RESULTS

A computational design protocol for sensing the nitazene family of synthetic opioids

Design of an allosteric biosensor requires solving the challenge of protein-ligand binder design consistent with, and constrained by, a structural definition of the transduction mechanism (27). A major advantage of redesigning PYR1 for new ligand sensing is that the receptor has an exceptionally well understood and characterized CID mechanism, where a bound water maintains hydrogen bonds between the ligand, the PYR1 receptor, and the HAB1 protein (17) (Figure 1A,B). We hypothesized that successful designs would recapitulate the spatial orientation of this ligand hydrogen bond acceptor.

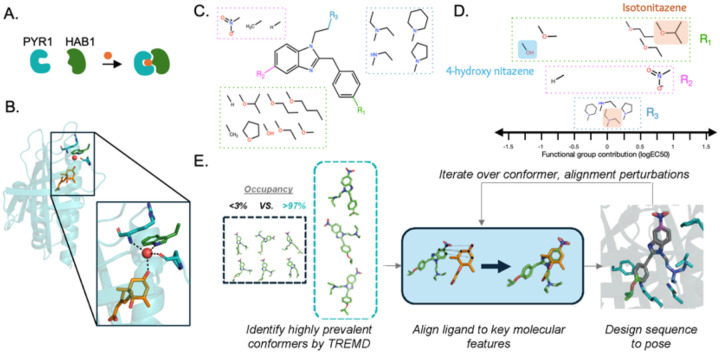

Fig. 1. Computational design of a pan-nitazene biosensor.

(A) Cartoon of the PYR-HAB chemically induced dimerization mechanism. (B) The structural definition of the transduction mechanism for PYR1 biosensors. The ligand shown as orange sticks is abscisic acid, the original PYR1 ligand. Red sphere shows the bound water molecule. (C) Structure of the nitazene central 2-benzyl benzimidazole with locations for possible substitutions color-coded. (D) Functional groups of nitazene derivatives organized by substitution position and contribution to molecular potency. The sign shows the direction of effect on potency (negative values are weaker potency), and the magnitude (logEC50) reflects contribution strength. Values are regression model coefficients from one-hot encoded functional group identities at each position. The R1 groups of isotonitazene and its less-potent metabolic product 4-hydroxy nitazene are labeled, as well as the common tertiary amine at R3 shared by both molecules. (E) Overview of the computational design process. Temperature replica exchange MD (TREMD) is used to identify highly prevalent solution populated ligand conformers. These conformers are aligned to key molecular features preserving the PYR1 transduction mechanism, and sequences are designed to each pose. This process is iterated over conformer and alignment perturbations and filtered to identify sets of sequences. A library is encoded using position-specific and local residue preferences.

To guide our design efforts, we first sought to understand the relationship between the molecular features of nitazenes and their potency. The nitazene family of 2-benzyl benzimidazole compounds contains substitutions observed at three positions (R1, R2, R3; Figure 1C) (7). We used supervised learning to classify the relative importance to potency of these substitutions (Figure S1) using a previous study of nitazene substitutions on cell-based activation of the μ-opioid receptor (7). A nitro group at R2 and larger aliphatic ethers at R1 increased potency significantly (Figure 1D), consistent with known potent synthetic opioids like isotonitazene (7, 28), which contains an isopropoxy branched ether group at R1. Substitutions of different N-containing heterocycles or secondary and tertiary amine groups at R3 have less effects on molecular potency. Finally, isotonitazene and other nitazenes are metabolized at R1 to an hydroxyl (7, 29–31), forming 4-hydroxy nitazene and related metabolites. This leaves the R2 group as a defining feature of nitazene potency. Thus, a biosensor that can detect a range of nitazenes containing an R2 nitro group and with limited cross-reactivity to other opioids is imperative for sensing nitazenes in the drug supply.

Repurposing an existing pocket to sense nitazenes requires a way to down-select the astronomical number of possible ligand-protein conformations. We accomplished this by developing a new computational design protocol to identify likely ligand-protein conformations and ligand orientations in the receptor binding pocket that maintain the transduction mechanism (Figure 1B,E). Sequences for these poses are then designed using either physically based (32) or deep learning (33) algorithms.

To identify likely conformers of isotonitazene, which contains 9 rotatable bonds, we performed temperature replica exchange MD simulations in solution. Three isotonitazene conformers were observed greater than 97% of the time (Figure S2). To orient these conformers in the binding pocket, we reasoned that likely configurations occur where the important nitro group hydrogen binds to the bound water critical to the dynamic transduction mechanism. Performing the alignment revealed that two isotonitazene conformers could dock without steric clashing when all 21 allowable positions in the binding pocket are mutated to glycine. These results match ligand docking experiments in a deeply mutagenized PYR1 library biased toward hydrophobic ligands (HMH, (34)), which contains sequences that allow docking of nitazenes in the binding pocket (Figure S3).

To test these initial steps of our computational design process, we screened a nitazene panel (Table S1) against the HMH library using a yeast two hybrid (Y2H) assay (35, 36), identifying sensors for six nitazene family members with differences in R1, R2, and R3 groups (although not isotonitazene; see Figure S4, Table S1, Table S2). Initial nitazene hits were identified with a geometric mean minimum dose response (MDR) of 61 μM in the Y2H growth selection, suggesting that their sequences were not optimized for binding. The hits had a mean of 6.4 mutations from the parental receptor; a previous computationally designed double site saturation mutagenesis library (18) yielded no sensors when nearly the same panel was screened (Table S1), highlighting that many PYR1 mutations are necessary to repurpose this privileged receptor for recognizing nitazenes.

Computational design protocol yields a nM-responsive nitazene binder

The insights from screening and structural modeling were integrated into the design process for a nitazene-specific PYR1 library. We used the perturbed alignments of predicted conformations of isotonitazene for Rosetta sequence redesign (see Methods, Table S3), fixing the identity of residues known to be essential for the allosteric transduction mechanism (17, 35). The library was ordered as an oligo pool and constructed by a four part Golden Gate assembly (37) in a thermally stabilized PYR1 background, PYR1HOT5 (38) (Table S4–S5, Figure S5). The library contained a mean of 9 mutations from the PYR1HOT5 background. We screened this library using Y2H assays against a panel of nitazenes (Figure 2A), identifying 49 unique ligand-responsive sequences for six nitazene analogs, including isotonitazene (Figure S6, Table S6). Sensors with the lowest MDR for each compound are shown in Figure 2B. Across all hits, the MDR was 19 μM, representing a significant improvement over that of the previous HMH library (61 μM; two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p-value 8.5e-5).

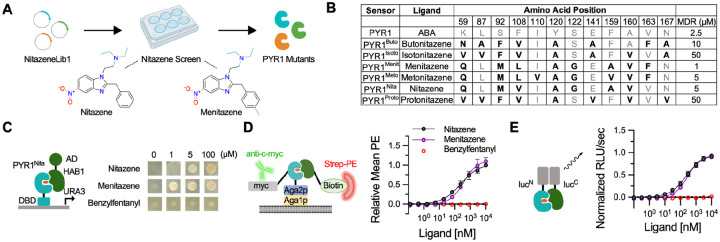

Fig. 2. Isolation of PYR1nita, a nanomolar sensor for the synthetic opioid nitazene.

(A) Schematic of the sensor isolation pipeline, including chemical structures of nitazene and menitazene. NitazeneLib1 was screened for sensors using Y2H growth selections in the presence of a ligand of interest. (B) Binding pocket mutations of PYR1 mutants hit from NitazeneLib1. The most sensitive receptor for each nitazene derivative is shown. Mutations from the wild type residues shown in bold. (C-E) PYR1nita portability to different sensing modalities: Y2H growth assays (C), yeast surface display (D), and in vitro split nano-luciferase assays (E). (D,E) n=4, data points represent the mean, error bars represent 1 s.d. and in some cases may be smaller than the symbol.

From this screen, we identified PYR1nita (PYR1HOT5/H60P/N90S with K59Q, S92M, F108V, Y120A, S122G, F159A, A160V) as the lead candidate. This mutant appeared in screens for nitazene (MDR: 5 μM), menitazene (MDR: 1 μM), and protonitazene (MDR: 50 μM), and showed no detectable binding to the structurally unrelated synthetic opioid benzylfentanyl (Figure 2C, Figure S6). To further characterize PYR1nita, we displayed it on the surface of yeast and performed cell surface titrations. No binding was observed in the presence of a thermostable variant of HAB1 (ΔN-HAB1T+) alone or in the presence of the structurally unrelated ligand benzylfentanyl. Saturable responses were observed for nitazene EC50 250 nM (95% c.i. 177–390 nM) and menitazene EC50 383 nM (95% c.i. 277–588 nM), with a limit of detection (LOD) for nitazene of 43 nM (Figure 2D). To test binding in vitro, we optimized a previously described ex vivo split luciferase detection system (18) using a split Nanoluc (39). Here, LgBiT is fused to a PYR1 sensor construct, and SmBiT is fused to HAB1 (40) (Figure S7). Ligand titrations showed no activation with benzylfentanyl and nanomolar sensitivity to both nitazene EC50 243 nM (95% c.i. 216–276 nM) and menitazene EC50 306 nM (95% c.i. 240–405 nM), with a LOD for nitazene of 3.2 nM (Figure 2E). Thus, the computational design pipeline enabled the isolation of a nitazene sensor with low nM sensitivity in vitro.

Optimization of nitazene biosensors by deep mutational scanning

Next, we used deep mutational scanning coupled with a directed evolution strategy to develop two distinct nitazene biosensors (Figure 3A). The first of these is for the detection of 4-hydroxy nitazene, the major metabolite byproduct of isotonitazene. While the current needed LOD is unknown (41), an effective sensor should exhibit a low nM LOD and function in complex biological matrices like urine. The second sensor is a pan-sensor capable of detecting nitazenes in mixtures. While the sensitivity requirement of this sensor is less strenuous, it must be specific for nitazenes compared with other synthetic opioids, fillers, or recreational drugs.

Fig. 3. Optimization of nitazene sensor breadth and sensitivity using deep mutational scanning.

(A) Overview of the protein engineering workflow. (B) Heatmap of calculated enrichment ratios of single-point mutations to the PYR1nita sensor in binding nitazene. 16 residues relevant to ligand binding were scanned. Purple indicates an increased enrichment ratio and orange indicates a decreased enrichment ratio relative to the parental sensor sequence. (C) Correlation plot of the enrichment ratios of PYR1nita binding nitazene versus menitazene. The color scale correlates to that of the heatmap. Open purple squares indicate mutations that result in constitutive binding. (D) Model of the PYR1nitav2 computationally designed structure. Structure of the PYR1nitav2 binding pocket, highlighting the histidine residue at position 159 which is hypothesized to delocalize the partial charge on the nitro group. Selected mutated residues from PYR1 are shown as cornflower blue sticks. (E) Sequence differences between WT PYR1, computationally designed PYR1nita, PYR1nitav2, and PANnita. New mutations added in each step of the optimization are shown in orange, purple, and green, respectively. (F) Yeast surface display titrations of PYR1nitav2 against nitazene (black circles), menitazene (purple circles), 4-hydroxy nitazene (cornflower blue circles), and benzylfentanyl (open red circles). The EC50 was 2.5 nM (95% c.i. 2.2 to 2.9 nM), 3.4 nM (95% c.i. 3.0 to 4.0 nM), and 2.9 nM (95% c.i. 2.2 to 3.9 nM) for nitazene, menitazene, and 4-hydroxy nitazene, respectively, using 500 nM of biotinylated ΔN-HAB1T+. (G) Yeast surface display binding measured for PANnita against indicated ligands. Max concentrations for butonitazene, isotonitazene, and N-pyrrolidino isotonitazene are 24 uM and 10 uM for benzylfentanyl. R1 and R3 groups that differ between nitazenes are indicated. **** p<0.0001, ** p<0.002, * p<0.05, ns not statistically significant. For all measurements, n=4 comprising two technical replicates performed on different days. Error bars represent 1 s.d.

In a first step to designing these sensors, we performed a deep mutational scan (DMS) of 16 positions inside of the PYR1nita binding pocket using yeast display screening coupled to fluorescence activated cell sorting. Libraries were screened at 250 nM of nitazene and menitazene (approx. 20% of the EC50). Additionally, a constitutive (no ligand but in the presence of the 500 nM HAB1T+ binding protein) and a reference control (sorting on all gates except the gate associated with binding) were included. Example sorting gates are shown in Figure S8.

Following deep sequencing of these populations, the frequencies of each mutant were assessed and normalized to the parental sequence by an enrichment ratio (Figure 3B, Figure S9). Most mutations (298/320) were depleted, indicating a restricted sensor pocket. Nitazene and menitazene shared 10 non-constitutive beneficial mutations (V81CLI, V83ML, M92FL, A120G, A159H, V164I; Figure 3C), largely in the aliphatic central cavity near the predicted binding site of the benzylimidazole nitazene scaffold (Figure 3D). The largest enriched mutation for both ligands was A159H. Our original design models did not include a residue which delocalizes the partial charge on the nitro group; we hypothesize that H159 satisfies this requirement (Figure 3D). Indeed, redesigning the PYR1 sequence using the deep learning algorithm LigandMPNN (33) identifies H159 in 8% of designs (Figure S10). Overall, the mutational profile is largely consistent with the designed binding mode.

To develop a sensor capable of binding the major metabolite byproduct 4-hydroxy nitazene, we used the DMS output to create a focused combinatorial library of 4,608 members largely containing the beneficial mutations shared between nitazene and menitazene (Table S7). Screening this library on nitazene and menitazene yielded two sensors, PYR1nitav2.1 (PYR1nita with V81I, M92F, A120G, G122E, E141D, A159H) and PYR1nitav2 (PYR1nita with V81I, V83L, E141D, A159H), containing 4–6 additional mutations from PYR1nita (Figure 3E and S10). Both sensors recognized 4-hydroxy nitazene, menitazene, and nitazene at an average LOD of 100 pM and EC50 of approx. 2 nM (Figure 3F, and S11), representing a more than 100-fold improvement in affinity over the originally designed PYR1nita sensor. Neither sensor recognized the unrelated synthetic opioid benzylfentanyl at the highest concentration tested, indicating highly specific recognition of nitazene, its metabolic byproduct 4-hydroxy nitazene and a close analog menitazene over a competing synthetic opioid.

To develop a sequence able to sense structurally diverse nitazenes, we used the structural model of PYR1nita to identify mutations which could allow binding breadth by increasing the pocket space for diverse functional R2 and R3 groups. We created a focused combinatorial library of 2048 variants encoding differences at positions 59, 141, 163, 164, & 167 to the PYR1nitav2.1 and PYR1nitav2 sensors (Table S8). After the library was screened against constitutive binders, the library was split and screened in parallel against butonitazene, isotonitazene, and N-pyrrolidino isotonitazene (Figure S12). These populations were deep sequenced; sequences that were enriched in all three ligand populations were individually tested (Figure S13). The best sensors, PANnita and PANnita.1, recognized all three diverse nitazenes and did not recognize benzylfentanyl (Figure 3G and S14). PANnita has in total 11 mutations in the receptor binding pocket out of 18 total mutable positions. Combined, computational design coupled to protein engineering can access a more diverse functional sequence space than accessed by previous libraries.

Development of a robust diagnostic assay suitable for biological matrices

To test whether PYRnitav2 and PANnita are capable of sensing nitazenes under relevant conditions, we repurposed our in vitro luminescence assay. Luminescence detection assays are susceptible to errors from varying experimental conditions including fluctuating activity in diverse biological matrices (42). For these reasons, ease of single sample detection is limited by the need for external calibration. A previously described calibrator luciferase (43) enables single-sample ratiometric quantitative readouts (Figure 4A). This assay compares the ratio of ligand dependent luminescence to background GFP fluorescence to mitigate experimental variance. We tested this new calibrator assay with the parental PYR1 sensor and a range of synthetic cannabinoid sensors (18). All tested sensors had nearly identical dynamic range, LOD, and EC50 values between buffer and urine (Figure S15). Using this assay, PYR1nitav2 could recognize 4-hydroxy nitazene with a LOD of 1 nM in urine, and with no cross-reactivity to the unrelated opioids benzylfentanyl, codeine, or heroin (Figure 4B). We next tested whether PANnita.1 could recognize diverse nitazenes relative to these other synthetic opioids. PANnita.1 bound the nitazene variants butonitazene, isotonitazene, and N-pyrrolidino nitazene while exhibiting minimal perception of benzylfentanyl, codeine, and heroin. At their highest tested concentration, this assay was able to detect a 6.4x, 7.2x, and 23x fold-change respectively for the target ligands butonitazene, isotonitazene, and N-pyrrolidino nitazene, with limited activation of off-target opioids (2-way ANOVA, p<0.0001) (Figure 4C). Similar results were obtained for the PANnita sensor (Figure S16).

Fig. 4. A ratiometric luminescent assay can sense nitazenes specifically in clinically relevant matrices.

(A) Cartoon of the luminescence assay. A mNeonGreen-NanoBiT “calibrator” protein enables ratiometric detection of samples, fluorescing at a wavelength of 520 nm independent of ligand concentration. PYR1 to ΔN-HAB1T+ dimerization results in an increased ratio of the relative luminescence units per second (RLU/s) at 450 nm versus the RLU/s at 520 nm. (B) Ratiometric assay of PYR1nitav2 in buffer or in urine using the indicated ligands. EC50 measurements and LOD for the sensor are colored for the appropriate condition. 200 nM SmBit-ΔNHAB1, 10 nM LgBiT-PYR1, and 512 pM calibrator are used. Benzylfentanyl, codeine, and heroin were tested in buffer. (C) Luminescence assay results using PANnita.1 show sensitivity against a panel of nitazene variants and synthetic opioids across multiple concentrations. Analysis of variance was calculated using an ordinary 2-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, with a single pooled variance (**** p<0.0001, ** p<0.01, ns not statistically significant). 4 nM SmBit-ΔNHAB1 and 4 nM LgBiT-PYR1 are used. Data is shown as the average of n=3 (A,B) or n=4 (C) replicates. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean and in some cases are smaller than the symbols. LODs were calculated using the 3σ method, which is equivalent to the drug concentration that yields a signal equal to 3 times the standard deviation of the blank after subtraction.

DISCUSSION

Computational protein design has advanced towards relevant and pressing societal needs (44). Here we designed and engineered protein biosensors for a range of clinically relevant synthetic opioids. The designed sensors, the best of which exhibit pM responsiveness and low nM EC50s, are orders of magnitude more sensitive than has been achieved by previously described computational approaches for small molecule binders (22, 24, 25). Our design success depended on a quantitative, molecular understanding of the dynamic transduction mechanism, which was worked out by biochemical and structural studies of abscisic acid perception in plants (17, 35, 45–48). A deeper mechanistic insight into the more complicated and varied allosteric transduction mechanisms of ligand-dependent molecules like GPCRs or bacterial transcription regulators (27) could improve biosensor hit rates for these classes of proteins.

Variants of the PYR1 receptor are able to sense an unusually broad spectrum of drug-like molecules (Tian et al, unpublished). This suggests that PYR1 sensors can be developed for a wide range of molecules, ultimately enabling new medical diagnostics, chemically-responsive cell therapies, environmental sensors (19), and biotechnologies for cell engineering (34). Our design process allows navigation to a search space largely inaccessible to random site saturation mutagenesis libraries, and when coupled with our conformer selection and alignment protocol creates a powerful design approach for ligand binding. We anticipate that emerging (49, 50) and future deep learning algorithms will further improve design and overall hit rates in designing PYR1 receptors for new target ligands, which could be incorporated into our protocol in the future as conformer selection and alignment are largely independent of sequence generation. Another possible approach to develop biosensors for wider swathes of chemical space is the generation of de novo proteins which maintain the PYR1 dynamic transduction mechanism. These efforts would be enabled by new computational and experimental tools to test and predict motions of designed proteins (51, 52).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Yves Janin for kindly providing the luciferase prosubstrate, Hikarazine-108. ACL would like to thank the Interdisciplinary Quantitative Biology and Molecular Biophysics programs at the University of Colorado Boulder for ongoing support. TAW would like to thank M. Stammnitz for helpful discussions related to transduction mechanisms for ligand-dependent protein biosensors.

Funding:

National Science Foundation NSF Award #2128287 (TAW)

National Science Foundation NSF Award #2128016 (SRC, IW)

National Science Foundation NRT Integrated Data Science Fellowship Award #2022138 (LMW)

NSF GRFP Award #1650115 (ACL)

NSF GRFP Award #2040434 (ZTB)

DARPA CERES Award#D24AC00011-05 (SRC, IW, TAW)

NIH award# R01GM123296 (LMW, AJF)

NIH award #5T32GM145437 (LMW)

Funding Statement

National Science Foundation NSF Award #2128287 (TAW)

National Science Foundation NSF Award #2128016 (SRC, IW)

National Science Foundation NRT Integrated Data Science Fellowship Award #2022138 (LMW)

NSF GRFP Award #1650115 (ACL)

NSF GRFP Award #2040434 (ZTB)

DARPA CERES Award#D24AC00011-05 (SRC, IW, TAW)

NIH award# R01GM123296 (LMW, AJF)

NIH award #5T32GM145437 (LMW)

Footnotes

Competing interests:

TAW, SRC, and IW, have filed a provisional patent entitled REAGENTS AND SYSTEMS FOR GENERATING BIOSENSORS (US9738902B2; WO2011139798A2) covering some research in the present work. TAW is a consultant for Inari Ag and serves on the scientific advisory board for Metaphore Biotechnologies and Alta Tech.

Data and materials availability:

An automated protocol for the TREMD conformer generation protocol is available on GitHub https://github.com/ajfriedman22/SM_ConfGen. PyRosetta scripts for biosensor design by structural replacement are available at https://github.com/alisoncleonard/Structural-Replacement-Biosensor-Design. Scripts used to generate figures S1 and S10 are available at https://github.com/WhiteheadGroup/Leonard_ComputationalDesign_Supplemental.Raw deep sequencing data are deposited in the SRA (BioProject ID PRJNA1256820), and analyzed deep sequencing data are on Zenodo (doi:10.5281/zenodo.15298585). All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse, Drug Overdose Deaths: Facts and Figures, National Institute on Drug Abuse (2024). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- 2.Opioid overdose. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose.

- 3.Prekupec M. P., Mansky P. A., Baumann M. H., Misuse of novel synthetic opioids: A deadly new trend. J. Addict. Med. 11, 256–265 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC, Fentanyl Facts, Stop Overdose (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/stop-overdose/caring/fentanyl-facts.html.

- 5.New, Dangerous Synthetic Opioid in D.C., Emerging in Tri-State Area, DEA. https://www.dea.gov/stories/2022/2022-06/2022-06-01/new-dangerous-synthetic-opioid-dc-emerging-tri-state-area.

- 6.CCENDU Drug Alert: Nitazenes (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vrieze L. M., Walton S. E., Pottie E., Papsun D., Logan B. K., Krotulski A. J., Stove C. P., Vandeputte M. M., In vitro structure-activity relationships and forensic case series of emerging 2-benzylbenzimidazole “nitazene” opioids. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 2999–3018 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland A., Copeland C. S., Shorter G. W., Connolly D. J., Wiseman A., Mooney J., Fenton K., Harris M., Nitazenes-heralding a second wave for the UK drug-related death crisis? Lancet Public Health 9, e71–e72 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krausz R. M., Westenberg J. N., Mathew N., Budd G., Wong J. S. H., Tsang V. W. L., Vogel M., King C., Seethapathy V., Jang K., Choi F., Shifting North American drug markets and challenges for the system of care. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 15, 86 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uljon S., Advances in fentanyl testing. Adv. Clin. Chem. 116, 1–30 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger M. S., Goedel W. C., Buxton J. A., Lysyshyn M., Bernstein E., Sherman S. G., Rich J. D., Hadland S. E., Green T. C., Marshall B. D. L., Use of rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Int. J. Drug Policy 61, 52–58 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman M., Badea A., Desnoyers C., Hayes K., Park J. N., An urgent need for community lot testing of lateral flow fentanyl test strips marketed for harm reduction in Northern America. Harm Reduct. J. 21, 115 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green H. H., New class of opioids that may be more potent than fentanyl emerges globally, The Guardian (2024). https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/sep/25/opioid-crisis-nitazenes-fentanyl. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner P. J., Swift S. D., Bedewitz M., Wheeldon I., Cutler S. R., Nusinow D. A., Whitehead T. A., A Closed Form Model for Molecular Ratchet-Type Chemically Induced Dimerization Modules. Biochemistry 62, 281–291 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziegler M. J., Yserentant K., Dunsing V., Middel V., Gralak A. J., Pakari K., Bargstedt J., Kern C., Petrich A., Chiantia S., Strähle U., Herten D. P., Wombacher R., Mandipropamid as a chemical inducer of proximity for in vivo applications. Nature Chemical Biology 2021 18:1 18, 64–69 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S. Y., Peterson F. C., Mosquna A., Yao J., Volkman B. F., Cutler S. R., Agrochemical control of plant water use using engineered abscisic acid receptors. Nature 520, 545–548 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melcher K., Ng L.-M., Zhou X. E., Soon F.-F., Xu Y., Suino-Powell K. M., Park S.-Y., Weiner J. J., Fujii H., Chinnusamy V., Kovach A., Li J., Wang Y., Li J., Peterson F. C., Jensen D. R., Yong E.-L., Volkman B. F., Cutler S. R., Zhu J.-K., Xu H. E., A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signalling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 462, 602–608 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beltrán J., Steiner P. J., Bedewitz M., Wei S., Peterson F. C., Li Z., Hughes B. E., Hartley Z., Robertson N. R., Medina-Cucurella A. V., Baumer Z. T., Leonard A. C., Park S.-Y., Volkman B. F., Nusinow D. A., Zhong W., Wheeldon I., Cutler S. R., Whitehead T. A., Rapid biosensor development using plant hormone receptors as reprogrammable scaffolds. Nat. Biotechnol., doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01364-5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S.-Y., Qiu J., Wei S., Peterson F. C., Beltrán J., Medina-Cucurella A. V., Vaidya A. S., Xing Z., Volkman B. F., Nusinow D. A., Whitehead T. A., Wheeldon I., Cutler S. R., An orthogonalized PYR1-based CID module with reprogrammable ligand-binding specificity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 103–110 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard A. C., Whitehead T. A., Design and engineering of genetically encoded protein biosensors for small molecules. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 78, 102787 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalogriopoulos N. A., Tei R., Yan Y., Klein P. M., Ravalin M., Cai B., Soltész I., Li Y., Ting A. Y., Synthetic GPCRs for programmable sensing and control of cell behaviour. Nature 637, 230–239 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An L., Said M., Tran L., Majumder S., Goreshnik I., Lee G. R., Juergens D., Dauparas J., Anishchenko I., Coventry B., Bera A. K., Kang A., Levine P. M., Alvarez V., Pillai A., Norn C., Feldman D., Zorine D., Hicks D. R., Li X., Sanchez M. G., Vafeados D. K., Salveson P. J., Vorobieva A. A., Baker D., Binding and sensing diverse small molecules using shape-complementary pseudocycles. Science 385, 276–282 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee G. R., Pellock S. J., Norn C., Tischer D., Dauparas J., Anischenko I., Mercer J. A. M., Kang A., Bera A., Nguyen H., Goreshnik I., Vafeados D., Roullier N., Han H. L., Coventry B., Haddox H. K., Liu D. R., Yeh A. H.-W., Baker D., Small-molecule binding and sensing with a designed protein family. bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2023.11.01.565201 (2023). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bick M. J., Greisen P. J., Morey K. J., Antunes M. S., La D., Sankaran B., Reymond L., Johnsson K., Medford J. I., Baker D., Computational design of environmental sensors for the potent opioid fentanyl. Elife 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polizzi N. F., DeGrado W. F., A defined structural unit enables de novo design of small-molecule-binding proteins. Science 369, 1227–1233 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchand A., Buckley S., Schneuing A., Pacesa M., Elia M., Gainza P., Elizarova E., Neeser R. M., Lee P.-W., Reymond L., Miao Y., Scheller L., Georgeon S., Schmidt J., Schwaller P., Maerkl S. J., Bronstein M., Correia B. E., Targeting protein–ligand neosurfaces with a generalizable deep learning tool. Nature, 1–10 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow A., Hobbs H. T., Perry Z. R., Wells M. L., Marqusee S., Kortemme T., Ligand-specific changes in conformational flexibility mediate long-range allostery in the lac repressor. Nat. Commun. 14, 1179 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shover C. L., Falasinnu T. O., Freedman R. B., Humphreys K., Emerging characteristics of isotonitazene-involved overdose deaths: A case-control study: A case-control study. J. Addict. Med. 15, 429–431 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taoussi O., Berardinelli D., Zaami S., Tavoletta F., Basile G., Kronstrand R., Auwärter V., Busardò F. P., Carlier J., Human metabolism of four synthetic benzimidazole opioids: isotonitazene, metonitazene, etodesnitazene, and metodesnitazene. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 2101–2116 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanamori T., Okada Y., Segawa H., Yamamuro T., Kuwayama K., Tsujikawa K., Iwata Y. T., Metabolism of highly potent synthetic opioid nitazene analogs: N-ethyl-N-(1-glucuronyloxyethyl) metabolite formation and degradation to N-desethyl metabolites during enzymatic hydrolysis. Drug Test. Anal., doi: 10.1002/dta.3705 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walton S. E., Krotulski A. J., Logan B. K., A forward-thinking approach to addressing the new synthetic opioid 2-benzylbenzimidazole nitazene analogs by liquid chromatography-tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-QQQ-MS). J. Anal. Toxicol. 46, 221–231 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maguire J. B., Haddox H. K., Strickland D., Halabiya S. F., Coventry B., Griffin J. R., Pulavarti S. V. S. R. K., Cummins M., Thieker D. F., Klavins E., Szyperski T., DiMaio F., Baker D., Kuhlman B., Perturbing the energy landscape for improved packing during computational protein design. Proteins 89, 436–449 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dauparas J., Lee G. R., Pecoraro R., An L., Anishchenko I., Glasscock C., Baker D., Atomic context-conditioned protein sequence design using LigandMPNN. Nat. Methods 22, 717–723 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson N. R., Lenert-Mondou C., Leonard A. C., Tafrishi A., Carrera S., Lee S., Aguilar Y., Zamora L. S., Nguyen T., Beltrán J., Li M., Cutler S. R., Whitehead T. A., Wheeldon I., PYR1 biosensor-driven genome-wide CRISPR screens for improved monoterpenoid production in Kluyveromyces marxianus, bioRxiv (2024)p. 2024.11.14.623641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S.-Y., Fung P., Nishimura N., Jensen D. R., Fujii H., Zhao Y., Lumba S., Santiago J., Rodrigues A., Chow T.-F. F., Alfred S. E., Bonetta D., Finkelstein R., Provart N. J., Desveaux D., Rodriguez P. L., McCourt P., Zhu J.-K., Schroeder J. I., Volkman B. F., Cutler S. R., Abscisic Acid Inhibits Type 2C Protein Phosphatases via the PYR/PYL Family of START Proteins. [Preprint] (2009). 10.1126/science.1173041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaidya A. S., Peterson F. C., Eckhardt J., Xing Z., Park S.-Y., Dejonghe W., Takeuchi J., Pri-Tal O., Faria J., Elzinga D., Volkman B. F., Todoroki Y., Mosquna A., Okamoto M., Cutler S. R., Click-to-lead design of a picomolar ABA receptor antagonist with potent activity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daffern N., Francino-Urdaniz I. M., Baumer Z. T., Whitehead T. A., Standardizing cassette-based deep mutagenesis by Golden Gate assembly. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 121, 281–290 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daffern N., Johansson K. E., Baumer Z. T., Robertson N. R., Woojuh J., Bedewitz M. A., Davis Z., Wheeldon I., Cutler S. R., Lindorff-Larsen K., Whitehead T. A., GMMA Can Stabilize Proteins Across Different Functional Constraints. J. Mol. Biol. 436, 168586 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon A. S., Schwinn M. K., Hall M. P., Zimmerman K., Otto P., Lubben T. H., Butler B. L., Binkowski B. F., Machleidt T., Kirkland T. A., Wood M. G., Eggers C. T., Encell L. P., Wood K. V., NanoLuc Complementation Reporter Optimized for Accurate Measurement of Protein Interactions in Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 400–408 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gagnot G., Hervin V., Coutant E. P., Goyard S., Jacob Y., Rose T., Hibti F. E., Quatela A., Janin Y. L., Core-modified coelenterazine luciferin analogues: Synthesis and chemiluminescence properties. Chemistry 27, 2112–2123 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Vrieze L. M., Stove C. P., Vandeputte M. M., Nitazene test strips: a laboratory evaluation. Harm Reduct. J. 21, 159 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozel T. R., Burnham-Marusich A. R., Point-of-care testing for infectious diseases: Past, present, and future. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 2313–2320 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ni Y., Rosier B. J. H. M., van Aalen E. A., Hanckmann E. T. L., Biewenga L., Pistikou A.-M. M., Timmermans B., Vu C., Roos S., Arts R., Li W., de Greef T. F. A., van Borren M. M. G. J., van Kuppeveld F. J. M., Bosch B.-J., Merkx M., A plug-and-play platform of ratiometric bioluminescent sensors for homogeneous immunoassays. Nat. Commun. 12, 4586 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torres S. V., Valle M. B., Mackessy S., Menzies S. K., Casewell N., Ahmadi S., Burlet N. J., Muratspahić E., Sappington I., Overath M. D., Rivera-de-Torre E., Ledergerber J., Laustsen A. H., Boddum K., Bera A. K., Kang A., Brackenbrough E., Cardoso I. A., Crittenden E., Edge R. J., Decarreau J., Ragotte R. J., Pillai A. S., Abedi M. H., Han H. L., Gerben S. R., Murray A., Skotheim R., Stuart L., Stewart L., Fryer T., Jenkins T. P., Baker D., De novo designed proteins neutralize lethal snake venom toxins. Nature 639, 225–231 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santiago J., Rodrigues A., Saez A., Rubio S., Antoni R., Dupeux F., Park S.-Y., Márquez J. A., Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Modulation of drought resistance by the abscisic acid receptor PYL5 through inhibition of clade A PP2Cs. Plant J. 60, 575–588 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dupeux F., Santiago J., Betz K., Twycross J., Park S.-Y., Rodriguez L., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Jensen M. R., Krasnogor N., Blackledge M., Holdsworth M., Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Márquez J. A., A thermodynamic switch modulates abscisic acid receptor sensitivity. EMBO J. 30, 4171–4184 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santiago J., Dupeux F., Betz K., Antoni R., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Rodriguez L., Márquez J. A., Rodriguez P. L., Structural insights into PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA receptors and PP2Cs. Plant Sci. 182, 3–11 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao Q., Yin P., Li W., Wang L., Yan C., Lin Z., Wu J. Z., Wang J., Yan S. F., Yan N., The molecular basis of ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs by a subclass of PYL proteins. Mol. Cell 42, 662–672 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fry B. P., Slaw K., Polizzi N. F., Zero-shot design of drug-binding proteins via neural selection-expansion, bioRxiv (2025). 10.1101/2025.04.22.649862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho Y., Pacesa M., Zhang Z., Correia B. E., Ovchinnikov S., Boltzdesign1: Inverting all-atom structure prediction model for generalized biomolecular binder design, bioRxiv (2025). 10.1101/2025.04.06.647261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo A. B., Akpinaroglu D., Kelly M. J. S., Kortemme T., Deep learning guided design of dynamic proteins, bioRxivorg (2024). 10.1101/2024.07.17.603962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrari Á. J. R., Dixit S. M., Thibeault J., Garcia M., Houliston S., Ludwig R. W., Notin P., Phoumyvong C. M., Martell C. M., Jung M. D., Tsuboyama K., Carter L., Arrowsmith C. H., Guttman M., Rocklin G. J., Large-scale discovery, analysis, and design of protein energy landscapes, bioRxivorg (2025). 10.1101/2025.03.20.644235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S., Chen J., Cheng T., Gindulyte A., He J., He S., Li Q., Shoemaker B. A., Thiessen P. A., Yu B., Zaslavsky L., Zhang J., Bolton E. E., PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res., doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae1059 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leonard A. C., Friedman A. J., Chayer R., Petersen B. M., Woojuh J., Xing Z., Cutler S. R., Kaar J. L., Shirts M. R., Whitehead T. A., Rationalizing diverse binding mechanisms to the same protein fold: Insights for ligand recognition and biosensor design. ACS Chem. Biol. 19, 1757–1772 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dupeux F., Antoni R., Betz K., Santiago J., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Rodriguez L., Rubio S., Park S.-Y., Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Márquez J. A., Modulation of abscisic acid signaling in vivo by an engineered receptor-insensitive protein phosphatase type 2C allele. Plant Physiol. 156, 106–116 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beltrán J., Steiner P. J., Bedewitz M., Wei S., Peterson F. C., Li Z., Hughes B. E., Hartley Z., Robertson N. R., Medina-Cucurella A. V., Others, Rapid biosensor development using plant hormone receptors as reprogrammable scaffolds. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1855–1861 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daffern N., Francino-Urdaniz I., Baumer Z. T., Whitehead T. A., Benchmarking cassette-based deep mutagenesis by Golden Gate assembly, bioRxiv (2023)p. 2023.04.13.536781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medina-Cucurella A. V., Whitehead T. A., Characterizing protein-protein interactions using deep sequencing coupled to yeast surface display. Methods Mol. Biol. 1764, 101–121 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wrenbeck E. E., Klesmith J. R., Stapleton J. A., Adeniran A., Tyo K. E. J., Whitehead T. A., Plasmid-based one-pot saturation mutagenesis. [Preprint] (2016). 10.1038/nmeth.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mighell T. L., Toledano I., Lehner B., SUNi mutagenesis: Scalable and uniform nicking for efficient generation of variant libraries. PLoS One 18, e0288158 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steiner P. J., Bedewitz M. A., Medina-Cucurella A. V., Cutler S. R., Whitehead T. A., A yeast surface display platform for plant hormone receptors: Toward directed evolution of new biosensors. AIChE J. 66 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Magoč T., Salzberg S. L., FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

An automated protocol for the TREMD conformer generation protocol is available on GitHub https://github.com/ajfriedman22/SM_ConfGen. PyRosetta scripts for biosensor design by structural replacement are available at https://github.com/alisoncleonard/Structural-Replacement-Biosensor-Design. Scripts used to generate figures S1 and S10 are available at https://github.com/WhiteheadGroup/Leonard_ComputationalDesign_Supplemental.Raw deep sequencing data are deposited in the SRA (BioProject ID PRJNA1256820), and analyzed deep sequencing data are on Zenodo (doi:10.5281/zenodo.15298585). All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.