Abstract

Background

Community-acquired respiratory infections are a prevalent cause of sepsis. Current animal models simulate peritoneal rather than respiratory sepsis. This study sought to appraise an influenza model for its ability to develop sepsis.

Methods

Twenty-four six-week-old male BALB/c mice were intranasally inoculated with H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 virus at 3.7 × 10− 1, 3.7 × 100, 3.7 × 101, 3.7 × 102, 3.7 × 103, 3.7 × 104 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) to acquire different levels of clinical severity. Murine Sepsis Score (MSS) was recorded daily over 14 days. Platelets, serum bilirubin and creatinine levels were measured to reflect coagulopathy, liver and renal dysfunction. These three parameters are from the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score which is routinely used for monitoring human sepsis. The primary outcome is organ dysfunction.

Results

Out of 24 infected mice, seven (29%) did not survive beyond 9 days. MSS predicted mortality with an AUC of 0.989 (95%CI: 0.978-1.000; P < 0.001). Liver and renal dysfunction were detected in one non-survived and six survived mice. Histological examination revealed inflammation in lung and liver but not kidney tissues.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of influenza to cause organ dysfunction, providing a basis for building a murine model specific for viral respiratory sepsis, and more closely simulating human viral sepsis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s42826-025-00248-4.

Keywords: Influenza virus, Mouse model, Organ dysfunction, Viral respiratory sepsis

Background

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [1]. Sepsis affects 49 million people annually worldwide, with 25% of hospital cases resulting in death [2, 3]. Community-acquired respiratory infection is one prevalent cause of sepsis in emergency departments [4]. Viral aetiology accounts for 30–40% of sepsis but remains understudied [5–7]. Influenza affects a billion people, causing 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths yearly [8]. Most respiratory virus fatalities end in sepsis [9].

Current experimental models simulate peritoneal sepsis, including injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), injection of live pathogens, and impairment of barrier tissue integrity [10, 11]. There is no good murine model for viral respiratory sepsis, which may have contributed to translational failures of applying preclinical findings to human trials.

Murine models infected with viruses are widely studied but rarely assessed from the perspective of sepsis [12, 13]. Severe, lethal respiratory virus models may develop sepsis before death. This study assessed sepsis in a pneumonia model using the mouse-adapted, influenza virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1). We aimed to build a model that is specific for viral respiratory sepsis.

Methods

Six-week-old male BALB/c mice (20–25 g) were intranasally inoculated with H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 virus at doses of 3.7 × 10− 1, 3.7 × 100, 3.7 × 101, 3.7 × 102, 3.7 × 103 and 3.7 × 104 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) (n = 4 per dose) to acquire infections with different levels of clinical severity. The workflow is shown in Supplementary file 1. The sample size aligns with the protocol used to determine the median lethal dose (MLD50) of this virus and was repurposed for this study. Sham mice received PBS (n = 3). Mice were monitored daily for survival, weight, glucose, and clinical conditions via Murine Sepsis Score (MSS) [14, 15]. MSS evaluates severity based on appearance, level of consciousness, activity, response to stimulus, eye opening, respiratory rate and respiratory quality (Supplementary file 2). Mice were euthanised when they met our institutional humane endpoints (HEP) for animal euthanasia or at the end of the experiment (14 days). HEP were > 20% weight loss, or MSS > 10. Blood samples were collected immediately prior to euthanasia, allowing correlation of biochemical markers with MSS peaks, weight loss, and survival trends. Platelets, bilirubin and creatinine were quantified to reflect coagulopathy, liver and renal dysfunction, aligning with the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score which is routinely used for monitoring human sepsis (Supplementary file 3) [1, 16]. Whole blood platelet count was measured using a Sysmex XN-1000 V haematology analyser, and serum bilirubin and creatinine using a Sysmex BX-3010 chemistry analyser (Sysmex, Norderstedt, Germany). Lung, liver, kidney, spleen, brain and heart tissues were examined by histology as reported previously [17].

All analyses and figures were computed with GraphPad Prism (v.10 GraphPad Software, USA). Statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney U test, t test, and Kruskal–Wallis test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data were presented as median with 95% confidence interval (CI) and mean with standard deviation (SD). The correlation analysis was conducted by Spearman’s rank test. We report findings according to the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines 2.0 [18].

Results

MSS reflects physical conditions and predicts death after H1N1 infection

Survival rate

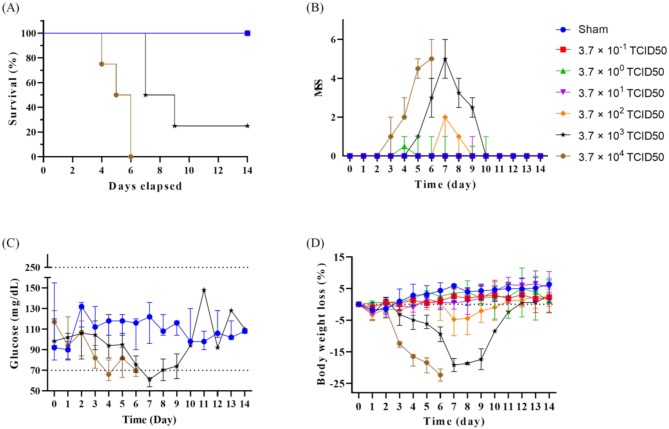

Of 24 infected mice, seven (29%) did not survive beyond nine days. After being inoculated with 3.7 × 104 TCID50, one mouse reached euthanasia criteria on day 4, and survival rate by day 6 was 0%. After being inoculated with 3.7 × 103 TCID50, only one mouse survived beyond 14 days with a survival rate of 25% at day 9 (Fig. 1A). No deaths occurred at lower doses.

Fig. 1.

Physical conditions of 6-week-old male BALB/c mice after intranasally inoculated with influenza virus H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34. Doses of at 3.7 × 10− 1, 3.7 × 100, 3.7 × 101, 3.7 × 102, 3.7 × 103 and 3.7 × 104 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) were evaluated over 14 days. Survival curve (A), Murine Sepsis Score (MSS) (B), blood glucose level (C), and body weight loss (D). Sham (PBS control): n = 3; H1N1 per dose group: n = 4. Data are presented as median with 95% confidence interval (CI)

MSS

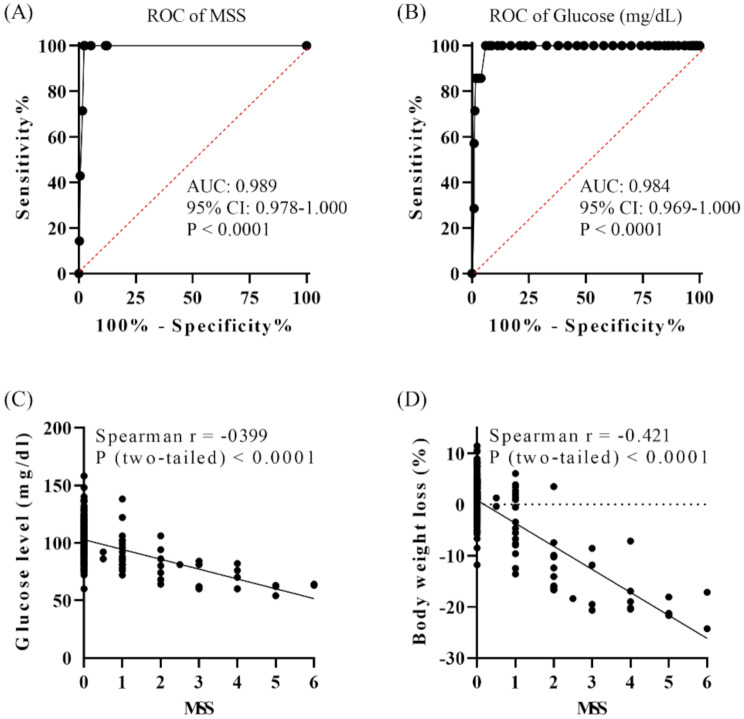

Mice monitored by MSS exhibited abnormal symptoms starting day 3, peaking at day 7 (maximum MSS of 6), and recovering by day 10 (Fig. 1B). Higher doses were associated with higher MSS, matching mortality rate. MSS effectively predicted death in H1N1-infected mice, with an AUC of 0.989 (95% CI: 0.978–1.000) (Fig. 2A). At a cut-off score of > 2.75, sensitivity was 100% (95% CI: 59.04–100%), and specificity was 97.65% (95% CI: 95.22–99.05%).

Fig. 2.

Performance of the Murine Sepsis Score (MSS) and blood glucose level in differentiating influenza virus H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 infected mice that survived and non-survived over 14 days. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves of MSS (A) and blood glucose level (B). Correlation between MSS and blood glucose level (C), MSS and body weight loss (D). H1N1 infected that survived: n = 17 and non-survived: n = 7. AUC: The area under the ROC curve. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Glycaemia

As blood glucose levels fluctuate in patients with sepsis, we assessed blood glucose variation in the infected mice [19, 20]. Infected mice exhibited hypoglycaemia before death, glucose dropping below 70 mg/dl (Fig. 1C). The AUC for glucose predicting mortality was 0.984 (95% CI: 0.969–1.000) (Fig. 2B). At a cut-off of < 77 mg/dl, sensitivity was 100% (95% CI: 59.04–100%), and specificity was 93.98% (95% CI: 90.65–96.30%).

Body weight loss

Surviving mice experienced maximum weight loss on day 7 before recovery (Fig. 1D). A 20% body weight loss met HEP criteria for euthanasia. All non-survived mice reached this criterion before euthanasia instead of natural death.

Correlations between MSS and glucose levels, and MSS and weight loss were 0.399 and 0.421, respectively (Spearman rank P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C and D). MSS reflects physical conditions and predicts death after H1N1 infection.

Organ dysfunction does not necessarily lead to death, and vice versa

Bilirubin

SOFA bilirubin reflects liver function. Normal serum bilirubin in mice was reported as 1.71 to 18.81 µmol/L [21]. This range can vary depending on factors such as strain, age, gender and specific study conditions. In this study, sham mice had a mean of 10.82 µmol/L (SD 8.59). Thus, the normal range (Mean ± 2 SD) was calculated as 0–28.00 µmol/L. Seven infected mice had bilirubin levels of 36.49 to 93.10 µmol/L, outside normal limits. Human SOFA normal range for this variable is 0–20 µmol/L, scored as 0 [16]. By proportion, sham mice and thirteen infected mice scored 0, five scored 1, and two scored 2 (Fig. 3A; Supplementary file 4 and 5). Of seven mice with scores ≥ 1, only one died by day 7, and other six survived beyond 14 days. There was no dose-response relationship between serum bilirubin levels and virus doses.

Fig. 3.

Application of SOFA score on sham (PBS control) and influenza virus H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 infected mice. *SOFA score of mouse serum bilirubin (A), creatinine (B), and platelets (C). *: Each criterion in the SOFA score was proportionally assigned to score the respective mouse parameters. Sham (PBS control): n = 3; H1N1 infected with available biochemistry data: n = 20

Creatinine

SOFA creatinine reflects renal function. Normal mouse creatinine was reported as 17.68 to 159.12 µmol/L [21]. In this study, sham mice had a mean of 49.33 µmol/L (SD 35.73), giving a calculated normal range of 0–120.79 µmol/L, matching human SOFA score 0 (0–110 µmol/L) for this variable [16]. By proportion, four infected mice scored 1, two scored 2, and one scored 3 (Fig. 3B; Supplementary file 4 and 5). Seven mice scoring creatinine ≥ 1 also scored bilirubin ≥ 1, indicating liver and renal dysfunction occurred simultaneously.

Platelets

Sham mice had a mean platelet count of 1,499 × 103/µL (SD 82.24), with a calculated normal range of 1,335–1,663 × 103/µL. Previous studies reported normal mouse platelet counts as 1,000–1,500 × 103/µL, and in human as 150–400 × 103/µL [22]. Human SOFA platelet score of 0 corresponds to platelets ≥ 150 × 103/µL [16]. All the infected mice scored 0, with a mean platelet count of 1,526 × 103/µL (SD 292.1), showing no significant differences from sham controls (P = 0.8779; t test) (Fig. 3C; Supplementary file 4 and 5). There was no coagulopathy in the infected mice. MSS does not predict organ dysfunction (AUC P = 0.4556).

Tissue damage in lung and liver were identified in the H1N1 model

Lung tissues displayed classic thin alveolar septa in sham controls and survived mice. Non-survived mice exhibited massive inflammatory cellular infiltration (Fig. 4). Acute lung injury appears to be the leading injury after H1N1 infection [23]. Hepatocytic vacuolation occurred in mice with detected liver dysfunction (Fig. 4), consistent with biochemistry results. No significant changes were seen in kidney, spleen, brain, or heart tissues (Supplementary file 6).

Fig. 4.

Histology of lung, liver and kidney from sham (PBS control) and influenza virus H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 infected mice. Score = 0: no organ dysfunction; score ≥ 1: organ dysfunction detected by biochemistry tests. Histology was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Blue arrow: massive inflammatory cellular infiltration; black arrow: hepatocytic vacuolation. Magnification: 600 ×. Size bar = 20 μm

Discussion

There is currently no gold standard murine sepsis model. We repurposed an influenza pneumonia model to assess its use for modelling viral respiratory sepsis. This strategy reduces time cost and is easy to implement. It will open an innovative way to develop experimental systems through collaborating with multiple research disciplines. We identified liver and renal dysfunction alongside lung inflammation in this model. This provides a prototype for building a murine model specific for viral respiratory sepsis, and more closely simulating human sepsis.

LPS models simulate endotoxemia, and surgery models, e.g., the caecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model, mimic abdominal sepsis [11]. This H1N1 model employs live influenza virus delivered intranasally, presenting a less-invasive and clinically relevant method for studying respiratory sepsis caused by viral infections. This model requires a higher biosafety level, which may limit its accessibility to some laboratories. Nevertheless, it serves as a valuable tool for advancing research into viral respiratory sepsis.

Mortality has been used to reflect sepsis, but although the mortality rate correlates with disease severity, it does not reflect organ dysfunction [24]. Further, sepsis does not necessarily lead to death. In fact, the majority of sepsis patients survive, with a mortality rate of 20–30% [25]. Hence, organ dysfunction could appear in survived mice but not must in non-survived mice. Bilirubin, creatinine, and platelets were used to quantify organ dysfunction, reflecting human SOFA scoring. In humans, the SOFA score is routinely used to monitor sepsis, reflecting the presence and severity of organ dysfunction [16]. Though MSS was developed to monitor murine sepsis, its subjective observational criteria do not address several critical components of human SOFA [14, 15]. There is a compelling need to develop a murine-SOFA comparable with human SOFA, which will allow for more confidence in translating animal study results into human studies.

Histological examination confirmed liver damage, consistent with liver dysfunction. No kidney damage was observed despite elevated serum creatinine indicating renal dysfunction biochemically. This aligns with reports of subtle histological changes in organs from septic mice despite significant biochemical changes [14]. In humans, it is impractical to perform biopsy to detect organ injury, resulting in a lack of histological evidence in sepsis patients.

One limitation of using this influenza model to produce viral respiratory sepsis is the selection of a dose that can lead to maximum levels of organ dysfunction in mice. There is no dose-response relationship observed between organ dysfunction and virus doses. Organ dysfunction appeared at lower doses but not consistently at the highest dose, and responses varied among mice inoculated with the same viral dose. Genetic susceptibility of individual mice to sepsis may contribute to the variability. This phenomenon mirrors clinical reality, where patients infected with influenza may experience varying disease severity; some develop sepsis, while others do not. These findings emphasise the need for future studies to determine an optimal dose of the H1N1 strain A/PR/8/34 to produce sepsis. Alternatively, a series of different doses will be required to produce this viral sepsis model, leading to difficulty in controlling experimental conditions, which will limit the use of this model in sepsis research.

The respiratory sepsis model will ultimately be used for biomarker discovery and drug research. The preclinical findings will be translated into human trials. Therefore, it is essential to determine the relevance of the experimental tools to real patients. Future studies will investigate the extent to which the mouse model reflects the real progression of viral sepsis in patients, and compare whether there is a similar progression trend of each parameter in SOFA scoring systems between mouse models and patients.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates H1N1 influenza virus can cause organ dysfunction, providing a basis for building a murine model specific for viral respiratory sepsis and more closely simulating human sepsis. Larger-scale, dynamic studies are needed to refine and validate the performance of this model. A murine scoring tool comparable to SOFA is essential.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- HEP

Humane endpoint

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MSS

Murine Sepsis Score

- SD

Standard deviation

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TCID50

Median tissue culture infectious dose

Authors’ contributions

YJ and TR conceived the study and designed the study. YJ, YC, YZ, KTC and KMC performed the experiments. YJ analysed the data. HY, PL and JN provided their expertise. YJ drafted the manuscript. TR revised the manuscript for critical content, and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by HKU Seed Fund for PI Research - Basic Research from the University Research Committee (URC) to THR.

Data availability

All datasets, on which the conclusions of the manuscript rely on, are presented in the paper.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted under the license of the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research (approval number: 23–507). This study was carried out by persons holding valid Cap. 340 licenses issued by the Department of Health, and the principles of laboratory animal care were followed along the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, et al. Global, regional, and National sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009–2014. JAMA. 2017;318(13):1241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H, Lan T, Guo S. Prognostic prediction value of qSOFA, SOFA, and admission lactate in septic patients with community-acquired pneumonia in emergency department. Emerg Med Int. 2020;2020(1):7979353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceccato A, Torres A. Sepsis and community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Res Hosp. 2018;2:7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madkour AM, AA EL, Elsayed MM. Prevalence and outcome of sepsis in respiratory intensive care unit. Egypt J Bronchol. 2022;16(1):29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaughn VM, Dickson RP, Horowitz JK, Flanders SA. Community-acquired pneumonia: A review. JAMA. 2024;332(15):1282–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70(9):1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos TA, Oliveira JE, Fonseca CDD, Barbosa DA, Belasco A, Miura CRM. Sepsis and COVID-19: outcomes in young adults in intensive care. Rev Bras Enferm. 2023;76(6):e20230037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis AJ, Seymour CW, Rosengart MR. Current murine models of sepsis. Surg Infect. 2016;17(4):385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korneev KV. Mouse models of sepsis and septic shock. Mol Biol. 2019;53(5):704–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan Y-M, Diao Z-L, Huang H-D, Zheng J-F, Zhang Q-D, Wang L-Y, et al. Bioactive peptide Apelin rescues acute kidney injury by protecting the function of renal tubular mitochondria. Amino Acids. 2021;53(8):1229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bednash JS, Kagan VE, Englert JA, Farkas D, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, et al. Syrian hamsters as a model of lung injury with SARS-CoV-2 infection: pathologic, physiologic, and detailed molecular profiling. Transl Res. 2022;240:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrum B, Anantha RV, Xu SX, Donnelly M, Haeryfar SM, McCormick JK, et al. A robust scoring system to evaluate sepsis severity in an animal model. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulzbacher MM, Sulzbacher LM, Passos FR, Bilibio BLE, de Oliveira K, Althaus WF, et al. Adapted murine sepsis score: improving the research in experimental sepsis mouse model. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:5700853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent J-L, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao Y, Tong CSW, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Nicholls JM, Rainer TH. Intraperitoneal versus intranasal administration of lipopolysaccharide in causing sepsis severity in a murine model: a preliminary comparison. Lab Anim Res. 2024;40(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du Sert NP, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, et al. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(7):e3000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Liu J, Shi G-P, Zhang X. Protocol for in vivo and ex vivo assessment of hyperglycemia and islet function in diabetic mice. STAR Protoc. 2023;4(1):102133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park MJ, Yoo SW, Choe BS, Dantzer R, Freund GG. Acute hypoglycemia causes depressive-like behaviors in mice. Metabolism. 2012;61(2):229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtz DM, Travlos GS. The clinical chemistry of laboratory animals. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda T, Asou E, Nogi K, Goto K. Evaluation of mouse red blood cell and platelet counting with an automated hematology analyzer. J Vet Med Sci. 2017;79(10):1707–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quispe-Laime AM, Bracco JD, Barberio PA, Campagne CG, Rolfo VE, Umberger R, et al. H1N1 influenza A virus-associated acute lung injury: response to combination oseltamivir and prolonged corticosteroid treatment. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(1):33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer M, Gerlach H, Vogelmann T, Preissing F, Stiefel J, Adam D. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019— results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Méndez R, Figuerola A, Ramasco F, Chicot M, Pascual NF, García Í, et al. Decrease in mortality after the implementation of a hospital model to improve performance in sepsis care: Princess Sepsis code. J Pers Med. 2024;14(2):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets, on which the conclusions of the manuscript rely on, are presented in the paper.