Abstract

Diabetic wounds are among the most common and costly complications in diabetic patients. As a result, numerous studies have been conducted to explore effective approaches for accelerating the wound healing process. Biological hydrogels are frequently used for wound healing due to their favorable properties compared to other materials. In this study, we evaluated the effect of a bioactive and degradable hydrogel based on dermal matrix (HDM) encapsulated with microspheres containing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin (IL)-10 on promoting wound healing in diabetic rats. Forty-five diabetic rats were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 15): control, HDM, and HDM encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 (HDMM). In addition, non-diabetic untreated rats (healthy group) were considered as control (n = 15). Wound assessments were performed on days 7, 14, and 21. The results demonstrated significant improvements in wound closure rate, fibroblast and blood vessel counts, collagen density, concentration levels of TGF-β and VEGF cytokines, and biomechanical parameters in the treatment groups compared to the control group, with the most pronounced effects observed in the HDMM group. Additionally, the HDMM group exhibited a greater reduction in neutrophil and macrophage counts, as well as decreased levels of TNF-α and IL-1β cytokines compared to the other groups. In conclusion, the HDM loaded with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 showed a more significant effect in promoting the healing of diabetic wounds.

Keywords: Diabetes, Wound healing, Dermal matrix, Hydrogel, VEGF, IL-10, Microspheres

Highlights

We studied the effects of hydrogel based on the dermal matrix encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 in diabetic wounds.

-

•

Treatment regulate the inflammatory process.

-

•

Treatment increase the angiogenesis.

-

•

Treatment improve the histological characteristics.

-

•

Treatment upregulated regenerative characteristics.

-

•

Treatment improve biomechanical characteristics.

1. Introduction

Diabetic wounds, particularly in individuals with poorly managed blood sugar levels, are a significant clinical challenge due to their delayed healing and increased risk of infection [1]. Chronic wounds in diabetic patients are often characterized by impaired cellular migration, defective angiogenesis, and a disrupted inflammatory response [2]. These persistent defects in wound healing processes not only compromise the quality of life but also lead to severe complications, including infections, amputations, and prolonged hospitalization [3]. Therefore, the development of novel therapeutic strategies to enhance wound healing in diabetic individuals remains a critical area of research [4].

Hydrogels, particularly those derived from biomaterials, have gained significant attention as potential wound dressings due to their excellent biocompatibility, moisture-retentive properties, and ability to facilitate drug delivery [5]. Among various hydrogel formulations, bioactive and degradable hydrogels, which can support cell growth and tissue regeneration, hold particular promise for wound healing applications [6]. These hydrogels can be designed to mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM), providing a scaffold for cellular infiltration and promoting tissue repair [7].

A particularly advantageous approach in designing such hydrogels involves utilizing dermal matrix as a key component [8]. The dermal matrix is a complex structure composed of various proteins, glycosaminoglycans, and collagen fibers, which provide structural support and regulate cellular functions within the skin [9]. As an essential part of the dermis, this matrix plays a critical role in wound healing by serving as a scaffold for fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and other key cells involved in tissue regeneration [8]. When used in hydrogel formulations, dermal matrix-derived components can mimic the natural wound healing environment, providing cues for cellular migration, proliferation, and ECM remodeling, which are crucial for effective tissue repair [10].

Recent advancements have shown that incorporating growth factors and cytokines into hydrogel formulations can further enhance their therapeutic potential [11]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a critical mediator of angiogenesis, promoting the formation of new blood vessels, which is essential for restoring blood flow and oxygen to healing tissues [12]. Similarly, interleukin-10 (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, plays a key role in modulating the immune response, reducing excessive inflammation, and promoting tissue repair [13,14]. However, the controlled delivery of these bioactive molecules presents a significant challenge, as uncontrolled release can lead to undesired effects [15].

To overcome these challenges, the use of microspheres to encapsulate VEGF and IL-10 offers a promising solution. Microspheres provide a controlled release mechanism, ensuring the gradual and sustained delivery of bioactive agents over time, which is crucial for optimal wound healing [16,17]. Additionally, the combination of bioactive, degradable hydrogels encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 has the potential to synergistically accelerate wound healing by addressing multiple aspects of the healing process, including angiogenesis, inflammation, and tissue regeneration.

In this study, we aim to investigate the efficacy of a bioactive and degradable HDM encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 in accelerating the healing of diabetic wounds in rats. We hypothesize that this advanced hydrogel formulation will significantly enhance the healing process by promoting angiogenesis, modulating inflammation, and supporting tissue regeneration, thus offering a promising therapeutic approach for managing chronic diabetic wounds.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Hydrogel based on dermal matrix (HDM) synthesis

HDM was prepared as described in a previous study by Milan et al. [10] with minor modification. Briefly, skin samples from a healthy adult female donor (aged 30–40 years) who underwent cosmetic surgeries such as mammoplasty or liposuction were collected under sterile conditions and quickly transported to the lab. To ensure standardization across scaffolds, the samples from different individuals were pooled together. Prior to the decellularization process, the skin samples were thawed, cut into approximate pieces of 5 × 5 cm2, and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove blood and other contaminants. The epidermis was then manually separated from the dermal layer. The tissue fragments were exposed to a series of treatments, including trypsin/0.02 % EDTA for 1 h, 3 % Triton for 3 h, and 4 % sodium deoxycholic acid for 2 h. After these treatments, the decellularized dermal matrix (dDM) was washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to lyophilization. For preparation of the HDM, the lyophilized dDM was digested in 1 % pepsin (w/w) and dissolved in 500 mM acetic acid for 72 h under continuous stirring. Afterward, the viscous hydrogel solution obtained was neutralized to a pH of 7.4 by adding NaOH.

2.2. HDM characterization

2.2.1. DNA content

To verify the elimination of cells and their residues, DNA content was assessed. To achieve this, the samples were completely homogenized and dissolved in a lysis buffer (1 mL, 50 mM tris-HCl, 50 mM EDTA, 1 % SDS, 10 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) and then digested overnight with proteinase K (10 mg/ml) at 65 °C. Following a phenol/chloroform extraction, DNA was precipitated with absolute ethanol. The resulting pellet was dissolved in RNase/DNase-free water, and the DNA concentration was assessed at a wavelength of 260 nm with a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) and expressed as ng of DNA per μg of the samples [18].

2.2.2. Biodegradability

To evaluate the biodegradability of the HDM, the initial weight of the freeze-dried hydrogel (Wd) was noted. The samples were subsequently submerged in a PBS solution with 100 μg/ml of collagenase type I and placed in an incubator at 37 °C. At specific intervals (1, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days), the samples underwent washing, freeze-drying, and re-weighting (Wt). The biodegradability was determined utilizing the subsequent formula: Biodegradability (%) = [(Wd - Wt)/Wd].

2.2.3. Ultrastructure

To evaluate their ultrastructure, one of the HDM was gold coated using an EmitechK575X Sputter coater, and electron micrographs were taken using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, TESCAN Mira3, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic).

2.3. Synthesis of microspheres

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres (50:50 lactic/glycolic) were fabricated utilizing a modified electrospray technique, as outlined by Yu et al. [19]. Ten mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.10 mL deionized water was subjected to sonication to mix with 0.12 g PLGA in 2 mL dichloromethane. The water-in-oil emulsion was electrosprayed onto an aluminum foil surface at a rate of 1 mL/h, using a 6 kV voltage applied between the spinneret and the collector, which were 20 cm apart. The procedure was refined to guarantee a consistent jet stream.

2.4. Synthesis of microspheres containing with VEGF and IL-10

To create microspheres containing with VEGF and IL-10, 25 μg of VEGF (from R&D Systems in Minneapolis, MN, USA) was dissolved in 25 μL of 0.1 % BSA and subsequently combined with 0.5 mL of 6 % PLGA. Furthermore, 25 μg of IL-10 (R&D Systems) was combined with 50 μL of 0.1 % (w/v) BSA prior to its addition to 1 mL of 6 % (w/v) PLGA. A water-in-oil emulsion was formed via sonication and subsequent electrospraying. After the solvent evaporated, the microspheres were gathered from the aluminum foil, freeze-dried, and stored at −20 °C.

2.4.1. The examination of VEGF and IL-10 release

The examination of VEGF and IL-10 release from PLGA microspheres involved adding 5 mg of microspheres to 1 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C while rotating at 25 rpm. The release medium with PLGA microspheres was clarified through centrifugation at specific intervals (1, 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 days), and 1 mL of the supernatant was stored at −80 °C. Concurrently, 1 mL of fresh PBS was added to keep the volume of the release medium constant and to remix the microspheres. ELISA kits (R&D Systems located in Minneapolis, MN, USA) were utilized to assess the concentrations of VEGF and IL-10 in the release medium.

2.5. Immobilization of microspheres into HDM (HDMM)

For the immobilization of microspheres into HDM (HDMM), the m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide ester (sulfo-MBS) was employed. To achieve this, the lyophilized HDM was first soaked in a sulfo-MBS solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) for 1 h, after which they were immersed in a microsphere solution for another hour. In the end, the final HDMM was washed three times with sterile PBS over the course of an hour and subsequently kept at −80 °C for later use.

2.6. HDMM characterization

2.6.1. Cell viability

Cell viability in HDMM samples was assessed using the MTT assay. MSCs (20 × 10ˆ3) were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator. Tissue samples were punched, weighed, and placed in the wells. After adding 100 μl of 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution to each well, the plates were incubated for 4 h. The medium was removed, and 600 μl dimethyl sulfoxide was added. Optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer.

2.6.2. Ultrastructure

To assess the ultrastructure of HDMM and the microspheres incorporated within it, SEM was utilized as stated in the earlier section.

2.7. Animals and study design

The study utilized sixty male Wistar rats, adhering to the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Type 1 diabetes mellitus was triggered in forty-five rats by an intraperitoneal injection of a single dose of 55 mg/kg of streptozotocin (STZ, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) mixed in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Three days later, the diabetes was confirmed as fasting blood sugar (FBS) > 250 mg/dL. Subsequently, animals were housed in separate metabolic cages in standard laboratory conditions. Diabetic rats were maintained for thirty days to confirm the induction of diabetes [20]. The animals were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 15) as follows: in addition to the non-diabetic untreated rats (healthy group), the diabetic ones were randomly divided into control group; HDM group; and HDM encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 (HDMM group). From each group, five rats were euthanized on days 7 (inflammatory phase), 14 (proliferative phase), and 21 (maturation phase).

2.8. Surgery

The rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (80 mg/kg; 10 mg/kg). To induce the wound, the animals were placed in a prone position, and the back and chest region was shaved. Following the sterilization of the area with 70 % ethanol, a circular wound measuring 2 cm in full thickness was created. In the HDM and HDMM receiving groups, right after the surgery, HDM or HDMM were applied to the wound site so that they completely covered the entire area.

2.9. Wound closure rate

On days 0, 7, 14, and 21 post-surgery, a digital camera was employed to capture images of the wound area, and the surface area was calculated using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) on a daily basis, as detailed below:

Wound closure percentage = ((initial wound size − exposed area on day X)/initial wound size) × 100 %.

2.10. Histological and stereological assessments

Tissue samples were gathered and preserved in 4 % paraformaldehyde. Following standard histological procedures, the specimens were encased in paraffin. Ten sections from each rat were chosen and stained using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Two thicknesses were utilized: 5 μm for evaluating collagen deposition and 20 μm for analyzing the count of fibroblasts, blood vessels, neutrophils, and macrophages. All stereological assessments were conducted following the methods of Howard and Reed [21].

To assess collagen deposition in the healing dermis and compare it across groups, we employed Masson's trichrome (MT) staining. To achieve this, five randomly selected micrographs from five different sections were taken for each sample with a 100 × magnification objective lens. The quantification of collagen distribution was performed using ImageJ software from MacBiophotonics and digital densitometry analysis. The percentage of collagen was determined by dividing the overall blue-colored region by the total areas of the micrographs [4].

The stereological method was performed to determine the number of the fibroblasts, blood vessels, neutrophils, and macrophages using the following equitation:

; where ΣQ: number of nuclei, h (μm): height of the dissector, Σp: the total number of the counted frames, a/f (mm2): frame area, BA (μm): block advance of the microtome (set at 20 μm), and t (μm): real sectional thickness (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Moreover, the following formula was used to assess the number of blood vessel: ; where ΣP: total number of the counted frames, ΣQ: total number of the vessel profiles counted per skin, and a/f (mm2): counting frame area (Supplementary Fig. 1).

2.11. Measurement of TGF-β, VEGF, TNF-α, and IL-1β cytokines

The ELISA technique was used to measure the levels of key cytokines involved in wound healing and tissue regeneration. The cytokines measured included TGF-β (an important cytokine for cell growth and repair), VEGF (essential for angiogenesis), and two pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β. To ensure consistency between groups, half of the wound tissue was harvested on day 7, and the same amount (100 mg) was used for cytokine quantification in each rat. The tissue samples were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (1 mM), Triton X-100 (1 %), EDTA (2 mM), sodium pyrophosphate (2.5 mM), Tris (20 mM), and leupeptin (0.5 mg/ml). The resulting solution was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min to isolate the cell pellet. Cytokine levels were quantified using ELISA kits (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. The specific kits used were: mouse TGF-β ELISA Kit (Catalog No: ab119557), mouse VEGF ELISA Kit (Catalog No: ab100751), mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit (Catalog No: ab208348), and mouse IL-1β ELISA Kit (Catalog No: ab197742). Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HTX, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). The cytokine concentrations were calculated based on the standard curves provided in the kits and expressed as picograms per milligram of protein.

2.12. Mechanical testing

On day 21, tissue samples (5 × 0.5 cm) were obtained from 5 rats in each group using a standard instrument. Specimens were mounted in a Shimadzu AGS-X Series tensiometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Deformation rate was kept constant at 10 mm/min and the load–deformation curve was recorded. The maximum force (N) and energy absorption (J) were calculated.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc). Data are shown as means ± SD. For group comparisons, one-way ANOVA was applied, and subsequently, Tukey's post-hoc test was conducted. A p-value below 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. It is evident throughout all sections of the results that the healthy group, being non-diabetic, demonstrated superior and more substantial outcomes than the other groups. Consequently, the findings are exclusively compared and presented among the diabetic groups.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of HDM and HDMM

To confirm the removal of cells and their remnants, DNA content was evaluated. The analysis of DNA content revealed that the DNA levels dropped to under 3 ng/μg, indicating that more than 97% of the cellular DNA was removed from the dDM (Fig. 1A). An examination of biodegradability indicated that the rate of HDM degradation gradually attained approximately 71 % by day 21 (Fig. 1B). The persistent release of VEGF and IL-10 throughout a 21-day timeframe began at roughly 9.66 ± 1.53 % and 12 ± 1 % for VEGF and IL-10, respectively, on the first day, ultimately reaching about 84.66 ± 5.5 % for VEGF and 91.33 ± 3.78 % for IL-10 by day 21 (Fig. 1C). Evaluation of cell viability showed that neither the manufactured HDM nor the HDMM exhibited any notable toxicity (Fig. 1D). Examining the HDM with SEM revealed that it had a porous structure, offering an appropriate framework for cell invasion and migration (Fig. 1E). Additionally, examining the HDMM with SEM indicated that microspheres were effectively loaded onto the surfaces of the scaffold (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of HDM and HDMM. (A) To verify the elimination of cells and their remnants, DNA content was assessed. The examination of DNA content showed that the DNA concentrations decreased from 98 ng/μg to below 3 ng/μg, suggesting that over 97% of the cellular DNA was eliminated from the dDM. (B) To assess the biodegradability of the fabricated scaffolds in the body environment, collagenase type I was utilized. A study on biodegradability indicated that the degradation rate of HDM began at approximately 14 % on day 1 and increased to 71 % by day 21. (C) The continuous release of VEGF and IL-10 over a 21-day period started at approximately 9.66 ± 1.53 % and 12 ± 1 % for VEGF and IL-10, respectively, on day one, and culminated at around 84.66 ± 5.5 % for VEGF and 91.33 ± 3.78 % for IL-10 by the end of day 21. (D) Biocompatibility of HDM and HDMM were proved through MTT assay. The results indicated that neither the manufactured HDM nor the HDMM exhibited any notable toxicity. (E) To evaluate the ultrastructure of the fabricated scaffolds, scanning electron microscopy was used. The micrograph shows the structure of the HDM had a porous structure. (F) The ultrastructure of the HDMM indicated that the microspheres were uniformly distributed.

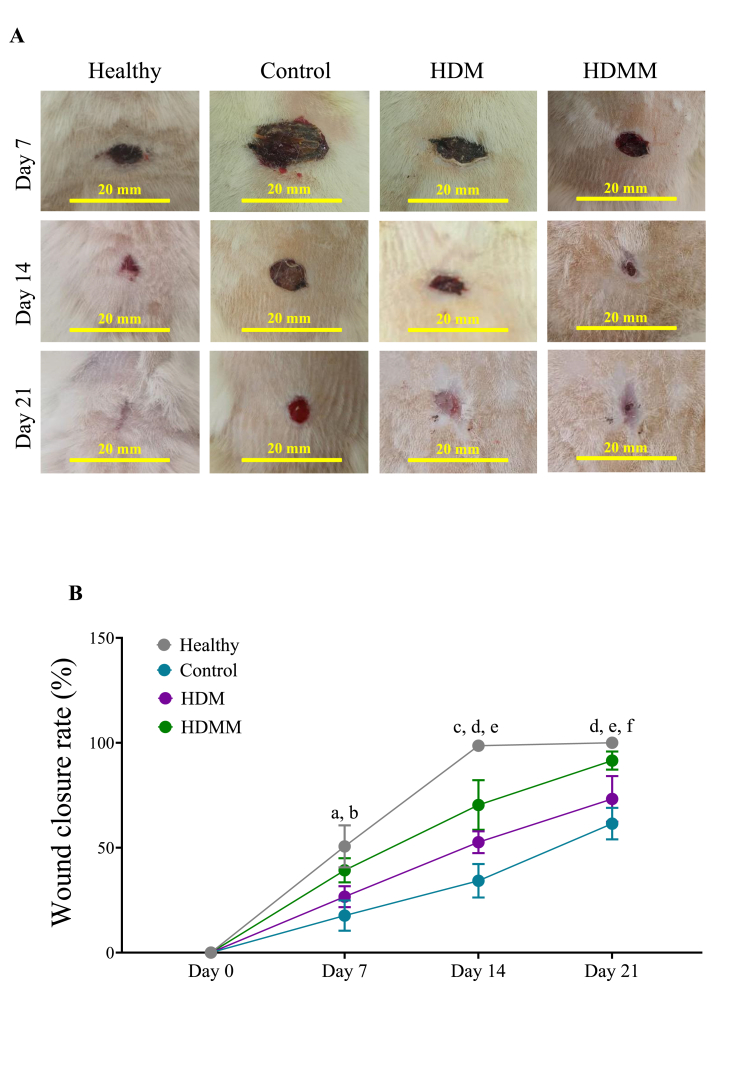

3.2. Wound closure rate

To assess wound healing on a macroscopic level, the wound site was photographed on days 7, 14, and 21, and the area of the wound was measured and compared among the study groups. The photographs from the wound area at three-time points are shown in Fig. 2A. Evaluation of the wound closure rate demonstrated a significant reduction in wound size in the HDMM group relative to the control group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.01, p < 0.0001, and p < 0.0001, respectively). Additionally, we discovered that the HDM group exhibited a notably greater wound contraction rate than the control group on days 14 and 21 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Additionally, the HDMM group exhibits a significantly greater wound closure rate compared to the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of HDMM on wound closure rate. (A) To evaluate wound healing at a macroscopic level, photographs of the wound site were taken on days 7, 14, and 21, and the percentage of wound closure rate was measured. (B) As shown in the graph, the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, had higher wound closure rate compared to the control group in all time intervals. a p < 0.01 HDMM group vs control groups; b p < 0.05 HDMM group vs HDM group; c p < 0.01 HDM group vs control group; d p < 0.0001 HDMM group vs control group; e p < 0.01 HDMM group vs HDM group; f p < 0.05 HDM group vs control group.

3.3. Stereological analysis

In the current research, the number of fibroblasts, blood vessels, neutrophils, and macrophages at the healed wound site were calculated through a stereological method and compared among the study groups.

3.3.1. Number of fibroblasts

Our findings indicated a significantly higher count of fibroblasts in the HDM and HDMM groups compared to the control group on days 7 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively), 14 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively), and 21 (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, the HDMM group shows a significantly greater count of fibroblasts compared to the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effects of HDMM on number of fibroblasts and blood vessels. Number of (A) fibroblasts and (B) blood vessels on days 7, 14, and 21, which was determined by stereological method. Regarding both parameters, fibroblasts and blood vessels, the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, were higher than the control group at all three time points. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

3.3.2. Number of blood vessels

In the comparison of blood vessel counts, the HDM and HDMM groups demonstrated a notably higher vessel count than the control group on days 7 (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively), 14 (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively), and 21 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, the HDMM group shows a notably higher number of blood vessels than the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3B).

3.3.3. Number of neutrophils

Upon analyzing the neutrophil count, we noted a significant decrease in neutrophils in the HDM and HDMM groups when compared to the control group on days 7 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively), 14 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively), and 21 (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively). In addition, the HDMM group exhibits notably reduced neutrophil counts compared to the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Effects of HDMM on number of neutrophils and macrophages. Number of (A) neutrophils and (B) macrophages on days 7, 14, and 21, which was determined by stereological method. For both cell types, the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, showed lower levels than the control group across all three time points. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

3.3.4. Number of macrophages

In evaluating the macrophage counts across groups, we noted that the HDM and HDMM groups exhibited a significantly lower number of cells compared to the control group on days 7, 14, and 21 (all instances, p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Moreover, the HDMM group displays notably fewer macrophage counts compared to the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4B).

3.4. Collagen deposition

MT staining was used to assess collagen density at the site of healed wounds. Fig. 5A depicts MT staining in tissue sections across the duration of the study. In quantitative assessment of collagen density among the study groups, we observed a significant increase in collagen density in the HDM and HDMM groups compared to the control group on days 7 (p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively), 14 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively), and 21 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Additionally, collagen accumulation in the HDMM group was significantly greater than in the HDM group on days 7, 14, and 21 (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of HDMM on collagen deposition. (A) Micrographs of the newly created dermis stained using the MT technique to depict collagen in a blue color. (B) Quantitative analysis of collagen density at three time points revealed that collagen deposition was elevated in the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, in relation to the control group. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

3.5. Cytokines concentration levels

To investigate the impact of treatments on the wound healing at molecular level, the levels of a regenerating cytokine (TGF-β), an angiogenesis-promoting cytokine (VEGF), and two pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) were measured on day 7 using the ELISA method. We found that the concentrations of TGF-β (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) and VEGF (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively) in the HDM and HDMM groups were markedly elevated compared to the control group. Additionally, the HDMM group demonstrates a significantly elevated level of VEGF when compared to the HDM group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 6.

Effects of HDMM on cytokine concentrations. The levels of concentration for (A) TGF-β (effective in proliferation and regeneration) and (B) VEGF (effective in angiogenesis), along with (C) TNF-α and (D) IL-1β (which are involved in inflammation) were assessed by employing the ELISA technique. The graphs indicating TGF-β and VEGF reveal that the levels of these two cytokines were greater in the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, than in the control group. Concerning the inflammatory cytokines, the findings demonstrated a notable reduction in the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, in relation to the control group. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Considering the pro-inflammatory cytokines, we observed that the HDM and HDMM groups showed considerably lower levels of TNF-α (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively) and IL-1β (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively) when compared to the control group. Examining the concentration levels of inflammatory cytokines across the treatment groups showed that the HDMM group displayed significantly lower levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in comparison to the HDM group (both, p < 0.01) (Fig. 6C and D).

3.6. Tensiometrical analysis

Tensiometry was used to assess the consistency of healed wounds. Regarding tensiometrical parameters, it was observed that both the HDM and HDMM groups exhibited significantly elevated scores for maximum force (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) and energy absorption (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively) when compared to the control group. In addition, the HDMM group demonstrates significantly higher scores for maximum force and energy absorption when compared to the HDM group (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 7A and B).

Fig. 7.

Effects of HDMM on tensiometrical parameters. To measure the consistency of healed wounds, tensiometry technique was used on day 21. The comparison of both parameters, (A) maximum force and (B) energy absorption indicated that the treatment groups, especially HDMM group, outperformed the control group in their scores. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the efficacy of a bioactive and degradable hydrogel based on the dermal matrix (HDM) encapsulated with microspheres containing VEGF and IL-10 for accelerating the healing of diabetic wounds in rats. Diabetic wounds are known for their delayed healing due to impaired angiogenesis, chronic inflammation, and insufficient ECM remodeling. The hydrogel developed in this study aimed to address these challenges by delivering VEGF and IL-10 in a controlled manner, which are key factors known to promote angiogenesis, reduce inflammation, and enhance tissue regeneration. Our findings demonstrated that this innovative hydrogel formulation (HDMM) significantly accelerated the healing process, enhanced cellular responses, and improved the mechanical properties of the wound healing tissue in diabetic rats. The key results showed that the HDMM-treated wounds exhibited significantly faster closure rates, higher collagen deposition, improved angiogenesis, and a marked reduction in inflammatory cytokines, suggesting the potential of this hydrogel as an effective therapeutic approach for managing diabetic wounds.

Chronic inflammation is a significant obstacle to wound healing, particularly in diabetic wounds, where prolonged inflammation can impair tissue regeneration and delay recovery [1]. In this study, we assessed the infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, which are key players in the inflammatory response, as well as the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β. Our results demonstrated that both the HDM and HDMM treatments significantly reduced the number of neutrophils and macrophages, as well as both pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to the control group at all-time points (days 7, 14, and 21). Moreover, the HDMM group exhibited a more pronounced reduction in macrophage count compared to the HDM group. Neutrophils and macrophages are the first responders to injury, and while they are essential for pathogen clearance and the initial inflammatory response, excessive or prolonged these cells and subsequent secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines can lead to tissue damage and hinder the progression to the proliferative phase of wound healing [22,23].

In our study, the significant reduction in inflammatory markers in the HDM and HDMM groups suggests that the hydrogel formulation, particularly with the incorporation of IL-10, modulates the inflammatory response effectively. IL-10 is a cytokine with anti-inflammatory properties that reduces both neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, and subsequent secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules such as IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, interferon- γ, matrix metalloproteinase-9, nitric oxide synthase, myeloperoxidase, and ROS. IL-10 reduces levels of pro-apoptotic factors like cytochrome c, caspase 3, and Bax, while increasing levels of anti-apoptotic factors such as B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and Bcl-2–associated X, B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (Bcl-xl) [24,25]. On the other hand, Yang et al. reported that the dermal matrix considerably suppressed the transcript of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 at the wound site [26]. Furthermore, Bour et al. and Khalatbary et al. reported that the dermis-derived scaffold contains anti-inflammatory factors and its placement in diabetic wounds can significantly reduce the transcript levels of inflammatory related genes and the number of inflammatory cells [8,9]. Therefore, considering the inflammatory findings, it can be concluded that the anti-inflammatory nature of the dermal matrix on the one hand and the presence of the cytokine IL-10 on the other hand have significant effects in reducing inflammation at the wound site.

In addition, in this study, we also examined characteristics related to wound site proliferation, including wound closure rate, fibroblast cell number, TGF-β cytokine concentration, and collagen deposition. In all cases, we found that the treatment groups indicated significant improvements relative to the control group, with the most noticeable advancements seen in the HDMM group. In this regard, Khalatbary et al. reported that the use of dermal derived matrix scaffold in the wound area considerably increase the volumes of newly formed dermis and epidermis, numerical density of fibroblasts, and the expression levels of miRNA-21, TGF-β, and bFGF [8]. In addition, Yu et al. documented that the dermal derived matrix contained a high amount of growth factors that affected cell proliferation and promoting wound healing [27]. On the other hand, studies have shown that IL-10, in addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, can play novel roles as a regulator of the extracellular matrix, fibroblast cellular function, and endothelial progenitor cells [28]. Additionally, the assessment of collagen accumulation in the newly developed dermis aligned with the results from the proliferative phase. We observed that the collagen density was notably higher in the treatment groups in comparison to the control group. Nevertheless, a key reason might be the composition of the hydrogels, predominantly made up of collagen [8,9]. Additionally, since the tensile strength of the wound tissue is closely linked to the collagen deposited in the wound bed, we evaluated three parameters, namely maximum force and energy absorption. The tissue strength results aligned with the collagen deposition findings, showing a notable increase in the treatment groups, particularly in the HDMM group when compared to the control group.

Proper blood supply is essential for efficient wound healing, particularly in diabetic wounds, where impaired angiogenesis often contributes to delayed tissue repair [12]. In this study, we focused on the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), as well as the expression of VEGF, a key cytokine that promotes vascularization. The results of our stereological analysis showed that both the HDM and HDMM groups exhibited significantly higher blood vessel counts and cytokine levels compared to the control group on days 7, 14, and 21. Moreover, the HDMM group demonstrated the highest number of blood vessels and VEGF concentrations across all time points. VEGF is a critical regulator of angiogenesis, known for stimulating endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and new capillary formation [29]. The elevated levels of VEGF in the HDM and HDMM groups suggest that the hydrogel, particularly with the addition of VEGF-encapsulated microspheres, effectively enhanced the local vascularization within the wound bed. This is especially crucial in diabetic wounds, where poor blood supply often hinders the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the regenerating tissue, thus slowing down the healing process [30]. The increased number of blood vessels observed in the HDMM group correlates with improved tissue perfusion and may facilitate the transport of essential nutrients and immune cells to the site of injury, promoting a more rapid and efficient healing process. Bour et al. reported that the dermal derived-matrix contains VEGF cytokine and can facilitate angiogenesis in the wound bed [9]. This finding further underscores the effectiveness of the hydrogel in delivering VEGF in a sustained manner, which not only enhances angiogenesis but also contributes to the overall acceleration of wound healing.

Furthermore, the observed decrease in the number of blood vessels over time after the initial increase in the inflammatory phase (day 7) is consistent with the natural progression of wound healing. In the early stages, angiogenesis is actively promoted to provide essential nutrients and oxygen to the healing tissue [31]. However, as the wound transitions into the proliferative and remodeling phases (days 14 and 21), the newly formed blood vessels begin to regress as part of tissue maturation. This regression occurs as the extracellular matrix becomes more organized, and the wound tissue stabilizes. The decrease in blood vessel count, therefore, reflects the dynamic nature of wound healing, where angiogenesis is initially upregulated, followed by vascular remodeling and maturation [20]. Notably, treatment groups showed a higher number of blood vessels compared to the control group, suggesting that the therapeutic interventions (HDM and HDMM) were effective in promoting angiogenesis during the early phases of healing.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that both HDM and HDMM treatments significantly improve wound healing by enhancing tissue remodeling, reducing inflammation, and promoting collagen deposition and angiogenesis. The combination therapy, HDMM, was particularly effective in promoting faster and more robust healing compared to the individual HDM treatment. Further research is needed to explore its underlying mechanisms and potential clinical applications.

Authors contributions

Z.W. Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft. J.L. Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Project administration. R.D., Y.Y., and C.F. Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation. S.Y. Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and informed consent

All animal experiments and human sample collection were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China. Skin samples were obtained from healthy adult female donors who underwent cosmetic surgeries such as mammoplasty or liposuction. Informed consent was obtained from all human donors prior to sample collection. The study adhered to all ethical standards concerning the use of human and animal subjects. All authors indicate that all animal experiments comply with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of in Vivo Experiments) and should be carried out in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, or the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Funding

The current project was financially supported by grants to S.Y. from Nanjing University, Nanjing, China.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reth.2025.04.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Burgess J.L., Wyant W.A., Abdo Abujamra B., Kirsner R.S., Jozic I. Diabetic wound-healing science. Medicina. 2021;57:1072. doi: 10.3390/medicina57101072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falanga V., Isseroff R.R., Soulika A.M., Romanelli M., Margolis D., Kapp S., et al. Chronic wounds. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:50. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowers S., Franco E. Chronic wounds: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amiri F.T., Omraninava M., Shahzamani S., Khodashenas A., Daryakar A., Nasiry D. Bioactive and degradable collagen-based three-dimensional scaffold encapsulated with adipose mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes improved diabetic wound healing. Regen Ther. 2025;28:606. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2025.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang T., Guo Q., Jia L., Yin T., Huang W., Zhang X., et al. Multifunctional hydrogels for the healing of diabetic wounds. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202301885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firlar I., Altunbek M., McCarthy C., Ramalingam M., Camci-Unal G. Functional hydrogels for treatment of chronic wounds. Gels. 2022;8:127. doi: 10.3390/gels8020127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharaziha M., Baidya A., Annabi N. Rational design of immunomodulatory hydrogels for chronic wound healing. Adv Mater. 2021;33 doi: 10.1002/adma.202100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalatbary A.R., Sarabandi S., Ahmadi F., Kasmaie F.M., Sadeghi N., Soleimani S., et al. Transplantation of bioengineered dermal derived matrix-scaffold in combination with hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves wound healing in diabetic rats. Tissue Cell. 2024;89 doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2024.102462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bour F., Khalilollah S., Omraninava M., Mirzaie M.S., Taghiloo S., Mehrparvar S., et al. Three-dimensional bioengineered dermal derived matrix scaffold in combination with adipose-derived stem cells accelerate diabetic wound healing. Tissue Cell. 2024;87 doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2024.102302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milan P.B., Lotfibakhshaiesh N., Joghataie M., Ai J., Pazouki A., Kaplan D., et al. Accelerated wound healing in a diabetic rat model using decellularized dermal matrix and human umbilical cord perivascular cells. Acta Biomater. 2016;45:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H., Xu Z., Zhao M., Liu G., Wu J. Advances of hydrogel dressings in diabetic wounds. Biomater Sci. 2021;9:1530–1546. doi: 10.1039/d0bm01747g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okonkwo U.A., DiPietro L.A. Diabetes and wound angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1419. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy R., Zayas J., Mohamed M.F., Aboonabi A., Delgado K., Wallace J., et al. IL-10 dysregulation underlies chemokine insufficiency, delayed macrophage response, and impaired healing in diabetic wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:692–704. e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.08.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafari A., Khalatbary A.R., Taghiloo S., Mirzaie M.S., Nazar E., Poorhassan M., et al. Exosomes derived from human placental mesenchymal stem cells in combination with hyperbaric oxygen synergically alleviates spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury. Regen Ther. 2023;24:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2023.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metwally W.M., El-Habashy S.E., El-Hosseiny L.S., Essawy M.M., Eltaher H.M., El-Khordagui L.K. Bioinspired 3D-printed scaffold embedding DDAB-nano ZnO/nanofibrous microspheres for regenerative diabetic wound healing. Biofabrication. 2023;16 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/acfd60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alissa M., Alghamdi A., Alshehri M.A. Fibrin scaffold encapsulated with epigallocatechin gallate microspheres promote neural regeneration and motor function recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury in rats. Tissue Cell. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2024.102691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu C., Hou B., Yang F., Huang X., Chen Y., Liu C., et al. Enhancing diabetic wound healing through anti-bacterial and promoting angiogenesis using dual-functional slow-release microspheres-loaded dermal scaffolds. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2024;242 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2024.114095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasiry D., Khalatbary A.R., Abdollahifar M.-A., Amini A., Bayat M., Noori A., et al. Engraftment of bioengineered three-dimensional scaffold from human amniotic membrane-derived extracellular matrix accelerates ischemic diabetic wound healing. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:567–582. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu S., Yao S., Wen Y., Wang Y., Wang H., Xu Q. Angiogenic microspheres promote neural regeneration and motor function recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep33428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalatbary A.R., Omraninava M., Nasiry D., Akbari M., Taghiloo S., Poorhassan M., et al. Exosomes derived from human adipose mesenchymal stem cells loaded bioengineered three-dimensional amniotic membrane-scaffold-accelerated diabetic wound healing. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2853–2870. doi: 10.1007/s00403-023-02709-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard V., Reed M. Garland Science; 2004. Unbiased stereology: three-dimensional measurement in microscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong S.L., Demers M., Martinod K., Gallant M., Wang Y., Goldfine A.B., et al. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat Med. 2015;21:815–819. doi: 10.1038/nm.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharifiaghdam M., Shaabani E., Faridi-Majidi R., De Smedt S.C., Braeckmans K., Fraire J.C. Macrophages as a therapeutic target to promote diabetic wound healing. Mol Ther. 2022;30:2891–2908. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson C.D., Zurko J.C., Hanna B.F., Hellenbrand D.J., Hanna A. The therapeutic role of interleukin-10 after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1311–1324. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Z., Peng X., Insolera R., Fink D.J., Mata M. IL-10 promotes neuronal survival following spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2009;220:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang H-y, Fierro F., So M., Yoon D.J., Nguyen A.V., Gallegos A., et al. Combination product of dermal matrix, human mesenchymal stem cells, and timolol promotes diabetic wound healing in mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9:1353–1364. doi: 10.1002/sctm.19-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu Y., Xiao H., Tang G., Wang H., Shen J., Sun Y., et al. Biomimetic hydrogel derived from decellularized dermal matrix facilitates skin wounds healing. Mater Today Bio. 2023;21 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King A., Balaji S., Le L.D., Crombleholme T.M., Keswani S.G. Regenerative wound healing: the role of interleukin-10. Adv Wound Care. 2014;3:315–323. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saaristo A., Tammela T., Fārkkilā A., Kärkkäinen M., Suominen E., Yla-Herttuala S., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C accelerates diabetic wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1080–1087. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasiry D., Khalatbary A.R., Abdollahifar M.-A., Bayat M., Amini A., Ashtiani M.K., et al. SDF-1α loaded bioengineered human amniotic membrane-derived scaffold transplantation in combination with hyperbaric oxygen improved diabetic wound healing. J Biosci Bioeng. 2022;133:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2022.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varyani L., Ahmadpanah N., Kasiri R., Shahzamani S., Tomraee S., Jafari A., et al. Human amniotic membrane hydrogel loaded with exosomes derived from human placental mesenchymal stem cells accelerate diabetic wound healing. Tissue Cell. 2024;91 doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2024.102590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.