Abstract

The purpose of this narrative review was to summarize perinatal exercise guidelines and associations of perinatal physical activity and/or exercise with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. Observational studies, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were included. Gaps in literature and suggestions for future studies were identified. Despite concordant international guidelines, data to support nuanced activity advice for some subgroups are limited. Perinatal physical activity and exercise are consistently recommended to combat traditional CVD risk factors during the perinatal period, like excessive gestational weight gain, high blood pressure, and high blood glucose. Physical activity and exercise appear to improve nontraditional risk factors such as poor sleep and depression. Data are emerging regarding associations with some pregnancy-specific factors, such as placental characteristics. Further research investigating associations with pregnancy-specific CVD risk factors and associations in the longer term, as well as data to support uptake, adherence, and resistance exercise prescription is warranted.

Key words: cardiovascular disease– physical activity, exercise, perinatal, pregnancy

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

Perinatal exercise guidelines address programming, safety issues, and some pregnancy-related anatomical or physiological changes.

-

•

Perinatal exercise can improve most traditional and some nontraditional cardiovascular disease risk factor determinants.

-

•

Independent and joint associations of perinatal exercise with pregnancy/perinatal-specific factors like placentation and lactation should be investigated.

-

•

Identifying optimal timing and dosing exercise strategies is important for improving perinatal and longer-term cardiovascular disease health.

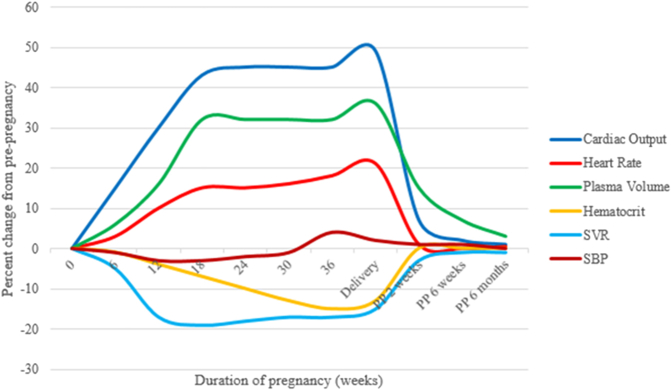

Pregnancy is a cardiometabolic challenge.1 Even in uncomplicated pregnancies, individuals become more insulin resistant, and cholesterol levels increase.2 Hemodynamic adaptations occur: increased cardiac output, heart rate, plasma volume, and red blood cell mass, along with decreased systemic vascular resistance and hematocrit (Figure 1).1 Normotensive pregnancy is characterized by a small, transient fluctuations in systolic blood pressure (BP) (Figure 1).3 Impaired hemodynamic adaptations may represent unmasking of pre-existing subclinical cardiovascular dysfunction and/or an independent process that contributes to long-term complications.3 Compared to other developed nations, maternal morbidity and mortality rates in the United States are high and rising, reaching 23.8 deaths/100,000 live births in 2020.4 Cardiovascular conditions are the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for >25% of all pregnancy-related deaths.5 Reasons include more women entering pregnancy with risk factors, poor access to healthcare, and unfavorable social determinants of health.4,5

Figure 1.

Hemodynamic Adaptations to Pregnancy

Adapted from Yucel et al.3

Evidence unequivocally demonstrates that regular exercise can prevent and/or treat adverse cardiometabolic conditions in many populations.6 Physical activity (PA) or exercise is associated with lower risk of novel and traditional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in the perinatal period,6 including adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [HDPs], gestational diabetes [GDMs], preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age deliveries).7,8 Offspring of individuals who exercise during pregnancy have better cardiovascular health, body composition, and nervous system development, with benefits extending into childhood.9

The goal of this narrative review is to synthesize literature related to perinatal PA/exercise, including national guidelines and effects of perinatal exercise on short- and long-term maternal CVD risk. This paper refers to PA as “any bodily movement resulting in energy expenditure,” while exercise is defined as “a subset of PA that is structured, repetitive, and aimed at maintaining or improving physical fitness.”10

Methods

Studies published in English were identified in PubMed and Google Scholar databases. Search terms included “pregnancy,” “pregnant,” “postpartum,” “perinatal,” “cardiovascular disease,” “risk factors,” “blood pressure,” “glucose,” “lipids,” “cholesterol,” “obesity,” “BMI,” “smoking,” “arterial stiffness,” “endothelial function,” “autonomic function,” “Flt-1,” “sleep,” “diet,” “inflammation,” “placenta/l,” “mood,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “exercise,” and “physical activity.” Observational studies, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were screened. When consensus statements, systematic reviews, and/or meta-analyses were found, conclusions were included. Results from individual studies were included if they specifically addressed the risk factor of interest and were conducted in a large or specific population or were one of the few existing studies related to a particular risk factor.

Perinatal exercise and PA recommendations worldwide

The benefits of exercise for reducing CVD risk are well described.11 Although benefits are clear, many individuals of reproductive age do not meet national PA guidelines including 150 min/wk or 500 MET·min/wk of moderate-vigorous aerobic activity and muscle-strengthening activities,6 and PA is frequently reduced during pregnancy and parenting.12

Current American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology guidelines

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) guidelines were updated in 2020 (Table 1).13 Previously, organizations recommended maintaining heart rates under specific levels (eg, 140 beats/min) due to wellbeing concerns.15 Guidelines now suggest using a subjective measure, the rating of perceived exertion (RPE), to monitor intensity as heart rate changes significantly during pregnancy.13 The RPE scale describes the individual's perception of physical work.16 Moderate-intensity exercise should elicit an RPE of 13 to 14 on the 6 to 20 scale, or “somewhat hard.”13,16 ACOG guidelines provide information about exercise frequency, type, intensity, and some information on duration.13 Musculoskeletal adaptations and injuries, as well as lower back, hip, leg, and foot pain are common17 and require consideration when prescribing perinatal exercise. Individualized or dynamic exercise prescriptions may be needed due to changes in body habitus and pre-existing or newly acquired comorbidities.13

Table 1.

Detailed Summary of PA and Exercise Guidelines During Pregnancy and Postpartum

| Exercise Principle | Recommendation | Red Flags |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 150 min spread out throughout the week for aerobic exercise; no specific dosing in guideline statements for resistance exercise; nonconsecutive days are recommended for resistance training in nonpregnant populations |

|

| Intensity | Moderate subjective exertion level of 12-14 on Borg Scale; <60%-80% of max effort; can say more than a few words or a sentence at a time during exercise but could not sing during exercise; Can continue vigorous activity if vigorous activity was performed prior to pregnancy; Moderate intensity resistance training characterized by >8 repetitions to volitional fatigue per set |

|

| Time | Work up to 30-60 min/session; Can begin with shorter durations until >20-30 min is possible | |

| Type | Non-contact aerobic training free from fall risk; resistance training including bands, bodyweight, or weights; pelvic floor exercises | |

| Environment & safety | Thermoneutral and preferably supervised setting; ensure hydration; avoid lying on back during pregnancy; avoid Valsalva maneuver during resistance training; avoid hypoglycemia; empty breasts before exercising if lactating | |

| Timing | From first trimester until delivery as tolerated; may resume as soon as it is safe; consult a healthcare provider after complicated birth or c-section |

Adapted from ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 804, National PA Guidelines, and the 2023 AHA Resistance Training Scientific Statement.6,13,14 Exercise physiology principles can be applied to the perinatal population for exercise prescription. Special considerations and red flags contraindicating exercise or necessitating exercise termination are included. Pregnant people should consult with a health care provider before beginning exercise. Hypoglycemia can be avoided by limiting the intensity or duration (<45 min) of exercise sessions and/or by consuming adequate calories before exercise.

Current ACOG guideline gaps

While resistance exercise is recommended, specific exercise prescription information is lacking in ACOG guidelines.13 For discussion of ACOG guidelines for patient subgroups and other guideline gaps, please see the Supplemental Appendix.

Global guidelines

Many countries developed their own perinatal exercise recommendations.18 While generally concordant, guidelines do not always have comprehensive exercise prescription recommendations (Table 2). A 2017 review reported prenatal walking, stationary cycling, aerobic exercises, dancing, resistance exercises, stretching exercises, hydrotherapy, and water aerobics have all been extensively studied and were safe and beneficial.19 Authors concluded that all pregnant individuals without a contraindication should engage in regular PA and exercise.19 Meta-analyses reported that women of normal weight (n = 2,059) who engage in aerobic exercise experience 49% lower incidence of GDM (2.9% vs 5.6%; relative risk: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.31-0.82) and 79% lower incidence of HDPs (1.0% vs 5.6%; relative risk: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.09-0.45).20

Table 2.

Summary of Perinatal PA and Exercise Guideline Components by Country

| Country | Frequency Days/Week | Intensity | Duration |

Type |

Prior Activity Level |

SB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | D | AE | RE | Inactive | Active | ||||

| Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Austria | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Belgium | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Brazil | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Brunei | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Canada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Chile | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cyprus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Denmark | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Estonia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Fiji | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Finland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| France | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Greece | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Iceland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Kenya | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Latvia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Malaysia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| NZ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Norway | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Portugal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Qatar | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Singapore | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Slovenia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Spain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sri Lanka | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Switzerland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| UK | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| USA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Uruguay | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

About half countries provide a weekly while half provide a daily exercise volume recommendation. Most countries provide frequency and intensity guidance. About half countries provide guidance on aerobic and resistance exercises. Most countries provide information regarding inactive people who become pregnant, with less information given for active women. Guidelines on sedentary behavior are provided in less than half the guidelines.

Adapted from Hayman et al.18

AE = aerobic exercise; D = daily; NZ = New Zealand; RE = resistance exercise; SB = sedentary behavior; UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America; W = weekly.

Pregnancy PA or exercise and CVD risk factor determinants during pregnancy and after delivery

Studies evaluated associations of perinatal exercise/PA and CVD risk factors. Summaries according to individual risk factors are found below with general effects shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Perinatal Exercise and Traditional and Novel CVD Risk Factor Determinants

| Risk Factor Determinant | Influence of Perinatal PA or Exercise |

|---|---|

| Traditional CVD risk factor determinants | |

| Blood pressure | ↓ SBP, ↓DBP21 |

| Glucose | ↓ Fasting blood glucose, ↓ risk of GDM22 |

| Obesity | ↓ Risk of excessive GWG, ↓ postpartum weight retention23 |

| Body composition | ↑ Improved maternal and fetal body composition ↓ Maternal fat mass,24 ↓ fetal fat mass25 |

| Lipid profile | ↑ Improved maternal LDL and triglyceride levels26,27 |

| Novel CVD risk factor determinants | |

| APOs | ↓ Risk of APOs, PE, GDM, LBW, PTB19 |

| Sleep | ↑ Improved sleep quality28,67 |

| Depression and anxiety | ↓ Risk of PPD13 |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | ↑ Fitness13 and ↓HDP29 |

| Inflammation | ↓ C-reactive protein30, 31, 32 |

| Arterial stiffness | ↔/? Pulse wave velocity33 |

| Endothelial function | ↑ Endothelial-dependent dilation34 |

| Cardiac autonomic control | ↓ Heart rate, ↑ HRV35,36 |

| Lactation | ↔ Breastmilk composition, volume, infant growth37 |

APO = adverse pregnancy outcomes; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; GWG = gestational weight gain; HDP = hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; HRV = heart rate variability; LBW = low birth weight; LDL = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PA = physical activity; PE = preeclampsia; PPD = postpartum depression; PTB = preterm birth; SBP = systolic blood pressure. ↑ = higher with exercise, ↔ = similar with PA/exercise, ↓ = decreased with PA or exercise.

Traditional CVD risk factor determinants

Blood pressure

According to a recent meta-analysis, exercise during pregnancy can lower systolic and diastolic BP by about 2-3 mm Hg (systolic: −3.19, 95% CI: −5.13 to −1.25 mm Hg; diastolic: −2.14, 95% CI: −4.26 to −0.03 mm Hg).21 Systolic BP was 7.5 mm Hg (95% CI: 1.5-12.6, P = 0.013) lower following a 12-week uphill walking exercise intervention in normotensive participants.38 This finding is important; even moderately elevated prenatal BP is associated with higher risk of hypertension years after delivery.39

Pregnant individuals at high risk of HDP had a smaller increase in systolic and diastolic BP from week 14 to 34 of pregnancy with a walking intervention; the mean systolic BP increase was 1.81 ± 2.40 mm Hg in walking group vs 9.87 ± 2.87 mm Hg in control group (P = 0.03).40 Regular PA during pregnancy appears to help prevent HDP and assist with management and severity in those diagnosed.7,40 Benefits are seen in individuals who do and do not exercise prior to becoming pregnant.13 PA prior to and during early pregnancy were associated with reductions in preeclampsia risk between 20% and 35%, with the greatest reductions seen in those engaged in PA prior to pregnancy (relative risk: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.47-0.89).41 Authors hypothesized that PA before and during early pregnancy could protect against hypertensive APOs due to improved placentation.41 The greatest benefits of PA were observed with 5 to 6 hours per week of exercise.41 This volume of PA is much greater than current guidelines for nonpregnant and pregnant adults.6

Less is known regarding the influence of prenatal PA or exercise on BP after delivery. An observational study reported that greater moderate-to-vigorous physical activity throughout pregnancy was linked to better BP in the first weeks after delivery.42 A sub-analysis of a trial that began in early pregnancy and focused on preventing excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) by counseling participants to eat healthfully and be more active found no effect of the intervention on BP patterns from early pregnancy to 12 months postpartum.43

Glucose

Performing high amounts of exercise (760 MET·min/wk) in early pregnancy–mid-second trimester was associated with a decrease of 3.9 mg/dL in glucose (95% CI: −7.4 to −0.5 mg/dL) compared with low exercise levels.22 According to a systematic review investigating associations between prenatal exercise and blood glucose, women with diabetes can improve fasting blood glucose following chronic exercise training (mean difference: −2.76 mg/dL, 95% CI: −3.18 to −2.34 mg/dL), an effect not observed in women free from diabetes (mean difference: −0.05 mg/dL, 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.05 mg/dL), although quality of evidence was “low.”44

GDM is a carbohydrate intolerance first observed during pregnancy and is associated with greater risk of hypertensive APOs, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.45 GDM is associated with higher lifetime risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs).46 PA is linked to a lower risk of GDM, and National PA Guidelines recommend PA/exercise to help prevent GDM.6,10 Once GDM is diagnosed, lifestyle modification, including moderate exercise, is recommended for first-line management.45 Lifestyle modification, including increasing PA, was one of the few strategies identified for combating excess CMD risk after GDM in a recent review.47

Body mass index

Increases in body mass index do not always completely reverse after delivery, predisposing individuals to risk of obesity.48 The Institute of Medicine sets pregnancy weight gain goals based on pre-pregnancy body mass index to optimize pregnancy outcomes,49 yet only 30% to 40% of women gain the recommended amount of weight.50 Excessive GWG and postpartum weight retention are associated with excess CMD risk in individuals who did and did not have GDM.51,52 Historically, there was concern that prenatal exercise increases risk of inadequate GWG; these fears have been refuted.13

National PA Guidelines and others concluded that prenatal/perinatal exercise lowered odds of excessive GWG and promoted better postpartum weight, especially when combined with healthy diet.10,23 ACOG recommends obesity management prior to pregnancy, as even small weight reductions may improve pregnancy outcomes.53 A randomized controlled trial that began in early pregnancy among individuals who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy counseled participants to eat healthfully and be more active demonstrated mildly favorable or null effects of the intervention on GWG depending on race and weight at study entry.54 However, the same study found postpartum weight outcomes were better in the intervention group: intervention participants retained 3.6 kg less weight (95% CI: −5.5 to −1.8 kg) at 6 months postpartum and 2.4 kg less weight (95% CI: −4.3 to −0.5 kg) at 12 months postpartum. At 6 months postpartum, overweight-intervention participants retained 4.1 kg less weight (95% CI: −6.7 to −1.5 kg), and obese intervention participants retained 3.3 kg less weight (95% CI: −5.8 to −0.7 kg) than control groups of the same weight status.55

Smoking

Pregnancy has been identified as an ideal time to intervene on smoking behaviors as pregnant women tend to have increased access to healthcare and may be motivated by fetal well-being.56 Health behaviors often cluster; PA interventions may have off-target effects on smoking. However, lifestyle interventions have not demonstrated consistent benefits on smoking cessation or relapse prevention in postpartum women.57 Studies that utilized a PA intervention as a smoking-cessation treatment have not been effective, although better PA quantification is needed.58

Diet

PA + nutrition interventions are recommended to combat obesity around the perinatal period.53 These combined interventions have had mixed effects on other pregnancy-specific CVD risk factors: GDM, excessive GWG, BP, APOs, and postpartum weight retention.43

Lipids

During pregnancy, cholesterol levels can increase by 50% to 70%.59 High maternal cholesterol levels during pregnancy may be associated with risk of CVD in offspring.60 Maternal dyslipidemia is associated with multiple APOs.61 Maternal lipid levels were improved with prenatal exercise (low-density lipoprotein levels mean change: −8 mg/dL, 95% CI: −3 to −29 mg/dL, P < 0.001) and triglycerides (mean change: −6 mg/dL, 95% CI: −1 to −11 mg/dL, P = 0.03)22,26,27 with nonsignificant improvements or no benefits seen with postpartum exercise in lactating women.62,63

Novel CVD risk factor determinants

Sleep

Poor sleep is an independent risk factor for CVD.64 Pregnancy has been associated with sleep disturbances and lower sleep quality.65 Greater sleep disturbances were directly associated with higher odds of preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR]: 2.80, 95% CI: 2.38-3.30), HDP (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.54-1.97), GDM (OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.45-1.76), preterm birth (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.26-1.51), and stillbirth (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.08-1.45).66 Exercise improves perinatal sleep, especially when initiated during early pregnancy,28 with improvements in sleep quality detected in a meta-analysis (OR: 6.21, 95% CI: 2.02-19.11, P = 0.001).67

Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety are strong CVD risk factors, especially for women.68 Depression and anxiety affect about 12% of pregnant and postpartum women.69,70 Exercise/PA can lower postpartum depression symptoms.6,71

Placental characteristics

Inadequate placental formation and vascularization is a seminal event in the pathogenesis of multiple APOs.72 Pan-vascular adaptations to exercise, including reduced inflammation and improved angiogenesis, may benefit placental development.73 Maternal exercise during pregnancy may influence placentation or placental characteristics.73 Pathological features, such as malperfusion lesions, have been associated with APOs and subclinical CVD after delivery.74,75

Better placental growth, volume, and function have been described in women who began or continued vigorous exercise (running) during pregnancy vs women who did not.76 A recent study found no association of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity with placental malperfusion lesions, but results were limited by the convenience sample that included only 50 individuals with medically indicated placental pathology examinations.42 Soluble FMS-like tyrosine-kinase-1 is a placenta-derived angiogenic inhibitor that is elevated in preeclampsia.77 Individuals in a national, diverse sample who were meeting PA guidelines had lower soluble FMS-like tyrosine-kinase-1 levels in the first trimester (846.3 pg/mL, 95% CI: 821.6-871.8) vs those who did not meet PA guidelines (893.0 pg/mL, 95% CI: 864.5-922.5, P < 0.017), potentially indicating a role for the placenta in the utility of PA for combating preeclampsia.78

Lactation

Lactation (dichotomous or dose-dependent) leads to both short- and long-term CMD risk-factor-determinant improvements, like insulin sensitivity, hypertension, lipid profiles, and glucose levels; is associated with 25% to 47% lower diabetes risk through late middle age; and is associated with lower lifetime CVD risk (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.83-0.95).79,80 Individuals affected by APOs may be less likely to lactate due to multiple biological and logistical factors, such as delayed lactogenesis or infant neonatal intensive care unit admission.81,82 With appropriate caloric intake, breastmilk volume and composition and infant growth are not influenced by moderate exercise.37 A recent national cohort study found that Black and White parous individuals who both lactated for ≥3 months during reproductive years and performed above average amounts of PA throughout adulthood had lower CMD risk scores in late middle age, suggesting joint (and not overlapping) effects of lactation and PA in adulthood.83

Arterial stiffness

Arterial stiffness is independently associated with CVD in people with and without hypertension.84 High arterial stiffness may be associated with greater risk of preeclampsia.85 Increases in arterial stiffness during pregnancy tend to normalize 7 weeks postpartum in most cases but may continue following delivery in women with preeclampsia, enhancing CVD risk later in life.86 A recent study concluded that aerobic exercise initiated after the first trimester in low-risk pregnancies does not appear to influence pregnancy-induced vascular adaptations, including arterial stiffness.33

Endothelial function

Endothelial function is enhanced during pregnancy, perhaps due to greater shear stress in arteries and higher circulating blood volume.87 Fetal growth restriction and HDP are often characterized by endothelial dysfunction.87 Regular exercise training can improve endothelial function in healthy pregnant individuals.34

Autonomic balance

Lower baroreflex sensitivity may be associated with greater risk of HDP.88 Higher than expected increases in resting heart rate may be associated with greater risk of HDP.88 Lower heart rate variability may be an important risk marker for HDP, suggesting sympathovagal imbalance may play a role in the etiology of HDP.88

A prospective study of 139 women reported higher beat-to-beat BP variability in every trimester in individuals who developed preeclampsia (systolic: first: 4.8 ± 1.3 vs 3.7 ± 1.2 mm Hg, P = 0.001; second: 5.1 ± 1.8 vs 3.8 ± 1.1 mm Hg, P = 0.02; third: 5.2 ± 0.8 vs 4.0 ± 1.1 mm Hg, P = 0.002; diastolic: first: 3.1 ± 0.9 vs 2.5 ± 0.7 mm Hg, P = 0.02; second: 3.0 ± 0.8 vs 2.5 ± 0.5 mm Hg, P = 0.007; third: 3.5 ± 1.3 vs 2.5 ± 0.8 mm Hg, P = 0.04).35 Elevated first trimester systolic beat-to-beat BP variability was associated with preeclampsia after statistical adjustment, OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 1.27-2.99.35 Sympathetic activity during pregnancy was improved in a recent, small trial of pregnant individuals who began aerobic exercise.36

Inflammation

In individuals who go on to develop some APOs, higher inflammation may be detectable early in pregnancy yet do not appear to pre-date pregnancy.89,90 C-reactive protein was lower in active (n = 16) vs inactive (n = 16) women with obesity (inactive: 9.1 ± 4.0 mg/L vs active: 6.3 ± 2.5 mg/L, P = 0.02).30 Women at risk of GDM enrolled in an exercise intervention (n = 84) or control group (n = 87) who maintained their exercise had a decrease in CRP while those who reduced their exercise had an increase in CRP (decreased PA: +0.09 mg/dL, 95% CI: −0.14 to 0.33; maintained PA: −0.08 mg/dL, 95% CI: −0.23 to 0.08, P < 0.05).31 Light PA was negatively and significantly correlated with maternal C-reactive protein (light PA: r = −0.40, P = 0.01, moderate PA: r = −0.18, P = 0.21).32

Future directions to improve understanding of perinatal exercise and CVD risk

Areas in need of investigation are described in Table 4. Participation in perinatal exercise or PA is low. Effective, low-cost, perinatal exercise/PA promotion strategies are needed. Although entering pregnancy with an established exercise routine would be ideal, many US pregnancies are unplanned.92 Just-in-time interventions supporting the adoption and upkeep of exercise programs immediately before, during, and after pregnancy are critical. Given the role of social determinants of health in CVD risk and PA/exercise participation, perinatal exercise strategies must be tailored and adapted for individuals across a broad range of social and economic strata.

Table 4.

Areas in Need of Research

| Gaps in Research Informing Recommendations | Significance and Suggestions for Future Studies |

|---|---|

| Timing and dosing strategies | Optimal timing and dosing of the PA or exercise (pre-pregnancy, mid-pregnancy, or postpartum) are unknown. Some association studies concluded that prepregnancy or early pregnancy exercise/PA is especially helpful.41 Specific guidelines for return to exercise and fitness progression postpartum in athletes are lacking. |

| Resistance training exercise programs | Data are sparse regarding the use of perinatal resistance training on CVD risk. Resistance training alone can improve multiple CVD risk factors in the general population14 and might be more feasible for pregnant individuals, especially in late pregnancy or early postpartum when aerobic exercise might be less comfortable. |

| Gaps in research regarding relationships with perinatal exercise | |

| Placental features | Whether perinatal exercise influences placental formation or function is not well defined. The use of more sensitive indicators of placental function and large, unbiased samples might better identify the optimal dose and timing of exercise/PA for placental health. |

| Lactation | Recent evidence suggests joint rather than overlapping effects of PA/exercise and lactation on cardiometabolic disease (CMD) risk.83 Whether PA must be performed before, during, or after lactation to mitigate later life cardiometabolic risk is unknown. |

| Arterial stiffness | Arterial stiffness is independently associated with CVD.84 Data regarding associations of perinatal exercise with arterial stiffness during and after pregnancy are extremely limited. |

| Sedentary behavior | Sedentary behavior is a CVD risk factor. Preliminary data reveled that high sedentary behavior is a risk factor for APOs.91 Detailed recommendations regarding total amounts and consideration of sedentary behavior volume in relation to PA volume do not exist. |

Conclusions

PA and exercise are recommended for pregnant and postpartum individuals without contraindications, have beneficial effects on CVD risk during and after pregnancy, and do not adversely influence infant growth or breastmilk (Central Illustration).10,93 Granular levels of information regarding optimal types, timing, doses, progression, and adoption and adherence strategies are sparser than those in the general nonpregnant population.6 More nuanced guidelines for prescribing and monitoring PA in individuals entering pregnancy or postpartum with CVD/CMD should be developed. Overlapping or interactive effects of exercise/PA with perinatal-specific factors linked to long-term CVD/CMD risk, such as placental development and lactation, need more investigation. Trials utilizing behavior change strategies and technologies should be tested in this population.

Central Illustration.

Guidelines and Benefits of Perinatal Exercise for Traditional and Non-Traditional CVD Risk Factor Determinants

Created with BioRender.

Funding support and author disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For a discussion of ACOG guidelines for patient subgroups and other guideline gaps, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplemental data

References

- 1.Sanghavi M., Rutherford J.D. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation. 2014;130:1003–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berggren E.K., Presley L., Amini S.B., Hauguel-de Mouzon S., Catalano P.M. Are the metabolic changes of pregnancy reversible in the first year postpartum? Diabetologia. 2015;58:1561–1568. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3604-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yucel E., DeFaria Y.D. Pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2017;19:73. doi: 10.1007/s11936-017-0572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S., Rexrode K.M., Florio A.A., Rich-Edwards J.W., Chavarro J.E. Maternal mortality in the United States: trends and opportunities for prevention. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:199–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042921-123851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians. Gynecologists' Presidential Task Force on Pregnancy. Heart Disease. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e320–e356. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piercy K.L., Troiano R.P., Ballard R.M., et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama. 2018;320:2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavard J.A., Artal R. Effect of exercise on pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:467–480. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816feb1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magee L.A., Smith G.N., Bloch C., et al. Guideline no. 426: hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: diagnosis, prediction, prevention, and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44:547–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2022.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moyer C., Reoyo O.R., May L. The influence of prenatal exercise on offspring health: a review. Clin Med Insights Womens Health. 2016;9:37–42. doi: 10.4137/CMWH.S34670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell K.E., King A.C., Buchner D.M., et al. The scientific foundation for the physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. J Phys Act Health. 2018:1–11. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiuza-Luces C., Santos-Lozano A., Joyner M., et al. Exercise benefits in cardiovascular disease: beyond attenuation of traditional risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:731–743. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane-Cordova A.D., Jerome G.J., Paluch A.E., et al. Supporting physical activity in patients and populations during life events and transitions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145:e117–e128. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syed H., Slayman T., Thoma K.D. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 804: physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:375–376. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paluch A.E., Boyer W.R., Franklin B.A., et al. Resistance exercise training in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2023 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;149:e217–e231. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing C.H., Stannard A.B. Pregnancy and exercise guidelines fifty years makes a difference. Acsms Health Fit J. 2016;20:4–6. doi: 10.1249/Fit.0000000000000183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borg G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borowski L.E., Barchi E.I., Han J.S., Friedman D.A., Carter C.W. Musculoskeletal considerations for exercise and sport: before, during, and after pregnancy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:e805–e814. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayman M., Brown W.J., Brinson A., Budzynski-Seymour E., Bruce T., Evenson K.R. Public health guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy from around the world: a scoping review. BMJ. 2023;57:940–947. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghella V., Saccone G. Exercise in pregnancy! Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:335–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Mascio D., Magro-Malosso E.R., Saccone G., Marhefka G.D., Berghella V. Exercise during pregnancy in normal-weight women and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Z., Xie H., Liu S., et al. Effects of physical exercise on blood pressure during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14074-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald S.M., Hinkle S.N., Grantz K.L., Zhang C. Maternal moderate-to-vigorous physical activity before and during pregnancy and maternal glucose tolerance: does timing matter? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:2520. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruchat S.-M., Mottola M.F., Skow R.J., et al. Effectiveness of exercise interventions in the prevention of excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1347–1356. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H., Santos-Rocha R., Radzimiński Ł., et al. Effects of 8-week online, supervised high-intensity interval training on the parameters related to the anaerobic threshold, body weight, and body composition during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2022;14:5279. doi: 10.3390/nu14245279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menke B.R., Duchette C., Tinius R.A., Wilson A.Q., Altizer E.A., Maples J.M. Physical activity during pregnancy and newborn body composition: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:7127. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramírez-Vélez R., Lobelo F., Aguilar-de Plata A.C., Izquierdo M., García-Hermoso A. Exercise during pregnancy on maternal lipids: a secondary analysis of randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:396. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1571-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark E., Isler C., Strickland D., et al. Influence of aerobic exercise on maternal lipid levels and offspring morphometrics. Int J Obes (Lond) 2019;43:594–602. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0258-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker J.H., Rothenberger S.D., Kline C.E., Okun M.L. Exercise during early pregnancy is associated with greater sleep continuity. Behav Sleep Med. 2018;16:482–493. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1228649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Huda F., Shapiro G.D., Davenport M.H., Bertagnolli M., Dayan N. Association between cardiorespiratory fitness and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4364. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinius R.A., Cahill A.G., Strand E.A., Cade W.T. Maternal inflammation during late pregnancy is lower in physically active compared with inactive obese women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:191–198. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins M., Braun B., Marcus B.H., Stanek E., Markenson G., Chasan-Taber L. The impact of an exercise intervention on C-reactive protein during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0576-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tinius R.A., Cahill A.G., Cade W.T. Low-intensity physical activity is associated with lower maternal systemic inflammation during late pregnancy. J Obes Weight Loss Ther. 2017;7:343. doi: 10.4172/2165-7904.1000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skow R.J., Steinback C.D., Davenport M.H. Prenatal exercise and cardiovascular health (PEACH) study: impact on the vascular system. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:2605–2617. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramírez-Vélez R., Aguilar de Plata A.C., Escudero M.M., et al. Influence of regular aerobic exercise on endothelium-dependent vasodilation and cardiorespiratory fitness in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1601–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuckols V.R., Holwerda S.W., Luehrs R.E., et al. Beat-to-beat blood pressure variability in the first trimester is associated with the development of preeclampsia in a prospective cohort: relation with aortic stiffness. Hypertension. 2020;76:1800–1807. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skow R.J., Fraser G.M., Steinback C.D., Davenport M.H. Prenatal exercise and cardiovascular health (PEACH) study: impact on muscle sympathetic nerve (Re) activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53:1101–1113. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovelady C., Lonnerdal B., Dewey K.G. Lactation performance of exercising women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:103–109. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haakstad L.A.H., Edvardsen E., Bø K. Effect of regular exercise on blood pressure in normotensive pregnant women. A randomized controlled trial. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2016;35:170–180. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2015.1122036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunietz G.L., Strutz K.L., Holzman C., et al. Moderately elevated blood pressure during pregnancy and odds of hypertension later in life: the POUCH moms longitudinal study. BJOG. 2017;124:1606–1613. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoram S., Loripoor M., Pirhadi M., Beigi M. The effect of walking on pregnancy blood pressure disorders in women susceptible to pregnancy hypertension: a randomized clinical trial. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:95. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_378_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aune D., Saugstad O.D., Henriksen T., Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2014;25:331–343. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lane A., Catov J., Jones M.A., Barone Gibbs B. Patterns in prenatal physical activity and sedentary behavior: associations with blood pressure and placental features in the MoMHealth cohort. J Phys Act Health. 2022;19:658–665. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lane A., Wilcox S., Wingard E., McLean M.K., Liu J. Association of a lifestyle intervention with blood pressure trajectories during pregnancy and postpartum in women with pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity. Matern Child Health J. 2023;27:1407–1415. doi: 10.1007/s10995-023-03709-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davenport M.H., Sobierajski F., Mottola M.F., et al. Glucose responses to acute and chronic exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1357–1366. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caughey A.B., Turrentine M. ACOG PRACTICE BULLETIN: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(2):E49–E64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis M.B., Arendt K., Bello N.A., et al. Team-based care of women with cardiovascular disease from pre-conception through pregnancy and postpartum: JACC Focus Seminar 1/5. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1763–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jowell A.R., Sarma A.A., Gulati M., et al. Interventions to mitigate risk of cardiovascular disease after adverse pregnancy outcomes: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:346–355. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunderson E.P. Childbearing and obesity in women: weight before, during, and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines . In: Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Rasmussen K.M., Yaktine A.L., editors. National Academies Press (US); 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herring S.J., Rose M.Z., Skouteris H., Oken E. Optimizing weight gain in pregnancy to prevent obesity in women and children. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minschart C., Myngheer N., Maes T., et al. Weight retention and glucose intolerance in early postpartum after gestational diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2023;188(5):438–447. doi: 10.1093/ejendo/lvad053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kew S., Ye C., Hanley A.J., et al. Cardiometabolic implications of postpartum weight changes in the first year after delivery. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1998–2006. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Catalano P.M., Koutrouvelis G.O. Obesity in pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 230. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(6):e128–e144. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J., Wilcox S., Wingard E., Turner-McGrievy G., Hutto B., Burgis J. A behavioral lifestyle intervention to limit gestational weight gain in pregnant women with overweight and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29:672–680. doi: 10.1002/oby.23119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu J., Wilcox S., Hutto B., Turner-McGrievy G., Wingard E. Effects of a lifestyle intervention on postpartum weight retention among women with elevated weight. Obesity. 2022;30:1370–1379. doi: 10.1002/oby.23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ussher M., Lewis S., Aveyard P., et al. Physical activity for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;350:h2145. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoedjes M., Berks D., Vogel I., et al. Effect of postpartum lifestyle interventions on weight loss, smoking cessation, and prevention of smoking relapse: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010;65:631–652. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182077f64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calder R., Gant E., Bauld L., McNeill A., Robson D., Brose L.S. Vaping in pregnancy: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:1451–1458. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jayalekshmi V.S., Ramachandran S. Maternal cholesterol levels during gestation: boon or bane for the offspring? Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:401–416. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03916-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palinski W. Effect of maternal cardiovascular conditions and risk factors on offspring cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2014;129:2066–2077. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hajar Sharami S., Abbasi Ranjbar Z., Alizadeh F., Kazemnejad E. The relationship of hyperlipidemia with maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019;17:739–748. doi: 10.18502/ijrm.v17i10.5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zourladani A., Zafrakas M., Chatzigiannis B., Papasozomenou P., Vavilis D., Matziari C. The effect of physical exercise on postpartum fitness, hormone and lipid levels: a randomized controlled trial in primiparous, lactating women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:525–530. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3418-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovelady C.A., Nommsen-Rivers L.A., McCrory M.A., Dewey K.G. Effects of exercise on plasma lipids and metabolism of lactating women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arnett D.K., Blumenthal R.S., Albert M.A., et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines (vol 74, pg e177, 2019) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1429–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mindell J.A., Sadeh A., Kwon R., Goh D.Y. Relationship between child and maternal sleep: a developmental and cross-cultural comparison. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40:689–696. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu Q., Zhang X., Wang Y., et al. Sleep disturbances during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;58 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang S.-Y., Lan S.-J., Yen Y.-Y., Hsieh Y.-P., Kung P.-T., Lan S.-H. Effects of exercise on sleep quality in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2020;14:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cho L., Davis M., Elgendy I., et al. Summary of updated recommendations for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2602–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leach L.S., Poyser C., Fairweather-Schmidt K. Maternal perinatal anxiety: a review of prevalence and correlates. Clin Psychol. 2017;21:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mughal S., Azhar Y., Siddiqui W. 2018. Postpartum depression. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brunson A., McLean M.K., Parker-Brown J., Whitney J., Lane A.D. Favorable lifestyle behaviors as reverse risk factors and treatment for postpartum depression. Phys Educ Sport Health Culture Modern Soc. 2024 doi: 10.29038/2220-7481-2023-04-95-103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roberts J.M., Hubel C.A. The two stage model of preeclampsia: variations on the theme. Placenta. 2009;30:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clapp J.F., 3rd Exercise during pregnancy: a clinical update. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:273–286. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Catov J.M., Muldoon M.F., Gandley R.E., et al. Maternal vascular lesions in the placenta predict vascular impairments a decade after delivery. Hypertension. 2022;79:424–434. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shaaban C.E., Rosano C., Cohen A.D., et al. Cognition and cerebrovascular reactivity in midlife women with history of preeclampsia and placental evidence of maternal vascular malperfusion. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.637574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Clapp J.F. Influence of endurance exercise and diet on human placental development and fetal growth. Placenta. 2006;27:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schrey-Petersen S., Stepan H. Anti-angiogenesis and preeclampsia in 2016. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:6. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Whorton A.E., Pan A.Y., Palatnik A. Effects of physical activity on placental analytes in nulliparous persons. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;292:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tschiderer L., Seekircher L., Kunutsor S.K., Peters S.A.E., O'Keeffe L.M., Willeit P. Breastfeeding is associated with a reduced maternal cardiovascular risk: systematic review and meta-analysis involving data from 8 studies and 1 192 700 parous women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lane A., Lewis C.E., Gunderson E.P. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: the missing link in discovering the role of lactation in cardiovascular disease prevention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.027707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chetwynd E.M., Stuebe A.M., Rosenberg L., Troester M., Rowley D., Palmer J.R. Cumulative lactation and onset of hypertension in African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:927–934. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burgess A., McDowell W., Ebersold S. Association between lactation and postpartum blood pressure in women with preeclampsia. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2019;44:86–93. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lane A., Whitaker K.M., Tahir M., et al. Associations of physical activity and lactation duration with cardiometabolic risk factors: the CARDIA study. JACC Adv. 2023;2 doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Niiranen T.J., Kalesan B., Hamburg N.M., Benjamin E.J., Mitchell G.F., Vasan R.S. Relative contributions of arterial stiffness and hypertension to cardiovascular disease: the framingham heart study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hausvater A., Giannone T., Sandoval Y.-H.G., et al. The association between preeclampsia and arterial stiffness. J Hypertens. 2012;30:17–33. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834e4b0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robb A.O., Mills N.L., Din J.N., et al. Influence of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and preeclampsia on arterial stiffness. Hypertension. 2009;53:952–958. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lopes van Balen V.A., van Gansewinkel T.A.G., de Haas S., et al. Physiological adaptation of endothelial function to pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:697–708. doi: 10.1002/uog.17431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Subha M., Pal P., Pal G.K., Habeebullah S., Adithan C., Sridhar M.G. Decreased baroreflex sensitivity is linked to sympathovagal imbalance, low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress in pregnancy-induced hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:666–672. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1200596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gomes J., Au F., Basak A., Cakmak S., Vincent R., Kumarathasan P. Maternal blood biomarkers and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2019;49:461–478. doi: 10.1080/10408444.2019.1629873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lane-Cordova A.D., Gunderson E.P., Carnethon M.R., et al. Pre-pregnancy endothelial dysfunction and birth outcomes: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:282–289. doi: 10.1038/s41440-018-0017-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barone Gibbs B., Jones M.A., Jakicic J.M., Jeyabalan A., Whitaker K.M., Catov J.M. Objectively measured sedentary behavior and physical activity across 3 trimesters of pregnancy: the monitoring movement and health study. J Phys Act Health. 2021;18:254–261. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finer L.B., Zolna M.R. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones P.A.T., Moolyk A., Ruchat S.M., et al. Impact of postpartum physical activity on cardiometabolic health, breastfeeding, injury and infant growth and development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2025 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.