Abstract

This work reports on various physicochemical properties and energy conversion processes in phosphate glasses containing Sn2+ and Nd3+ ions of interest for luminescence-based applications. The glasses were prepared by melting with 50P2O5-(49 – x)BaO-1Nd2O3-xSnO (x = 0, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 mol %) nominal compositions and characterized by X-ray diffraction, 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy, density and related physical properties, Raman spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, dilatometry, optical absorption, and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. X-ray diffraction confirmed the noncrystalline nature of the glasses. The 119Sn Mössbauer evaluation allowed for estimating the relative amounts of Sn2+ and Sn4+ in the glasses, which showed that Sn2+ occurrence was favored. The densities showed variations without definite trends; additional physical parameters were then determined such as Sn2+-Nd3+ distances based on 119Sn Mössbauer results. The characterization by Raman spectroscopy showed no significant structural variation was induced as SnO replaced BaO. The thermal properties of the codoped glasses assessed were however found to be impacted mostly by Sn2+ at high nominal SnO contents. Absorption spectra supported consistent occurrence of Nd3+ ions among the codoped glasses. The PL evaluation showed that exciting Sn2+ centers in the UV (e.g., near 290 nm) results in near-infrared emission from Nd3+, which was maximized for SnO added at 5 mol %. The visible PL data were consistent with the presence of Sn2+ in the glasses and showed dips in the emission spectra, indicating the energy transfer to Nd3+ ions. The Nd3+ decay times were however similar among the different samples.

Keywords: phosphate glasses, photoluminescence, physical properties, spectroscopy, structural properties, thermal properties

1. Introduction

Glasses doped with Nd3+ (f3) ions have been the subject of interest in optical technologies, with their near-infrared (NIR) emission being especially useful in high-power lasers. − Hence, it has been a topic of inquiry to find ways to maximize the Nd3+ luminescence output and add versatility to the laser pumping scheme. One of the strategies commonly investigated to enhance Nd3+ NIR emission or provide alternate routes for nonresonant excitation is based on codoping with metal ions acting as sensitizers, including Cr3+, Mn2+, , Sn2+, , Cu+, , and Ag+. , Among these, the use of Sn2+ was first proposed as a sensitizer for Nd3+ ions in La-containing glass by Malashkevich et al. over three decades ago. Their pioneering work, however, focused exclusively on evaluating the optical properties of SnO-La2O3-Nd2O3 containing glasses. More recently, Bondzior and Lisiecki reported on the energy transfer processes involving Sn2+ and Nd3+ as well as Yb3+ ions in lanthanum borate glasses. The authors noticed that the Sn2+ → Nd3+ transfer efficiency was especially high, and further evaluations suggested that the interaction was of the dipole–dipole type. Nonetheless, although the work embarked on an extensive optical investigation that included temperature-dependent phenomena, questions remain with regards to the impact of tin on various physical, structural, and thermal properties of the glass. Hence, there is still room for holistically investigating the physicochemical properties of a variety of glass systems containing SnO and Nd2O3.

Divalent tin is also commonly utilized as a reductant to stabilize other redox active species in glasses. ,, Apart from this use in formulations, its role as a Nd3+ NIR emission enhancer has been partially recognized in phosphate glasses co-doped with SnO/CuO , and SnO/Ag2O. However, the sole effect of luminescent Sn2+ centers on Nd3+ ions in phosphate glasses remains largely unexplored. Phosphate-based glasses are specifically desirable for Nd3+-based lasing due to their favorable solubility, thermo-mechanical properties, and manufacturability. − Divalent tin is also an interesting ns2-type center with blue-emitting character and has therefore been studied in phosphate glasses for light-emitting applications. − Various studies have thus been devoted to assess exclusively the role of tin ions in enhancing the luminescent properties of phosphate glasses in the presence of various rare-earths such as Eu3+, , Pr3+, , Dy3+, Sm3+, Er3+, , Gd3+, Yb3+, ,, and Tb3+. , Complementing this literature with new studies on SnO/Nd2O3 codoped phosphate glasses is then desired.

In this setting, we pursued a comprehensive experimental investigation of the effects of adding SnO at various concentrations on Nd3+-activated phosphate glasses of interest for optical applications. Considering the appeal of a simple fabrication method, material preparation was carried out by melting in ambient atmosphere, wherein the SnO concentration influences the resulting tin valences. The barium phosphate glass matrix used as host in prior studies ,,− was employed for SnO/Nd2O3 codoping, as it is considered adequate from fundamental and practical standpoints. The glasses were made with fixed Nd2O3 content at 1 mol %, which was found to be optimal in a recent investigation concerning 50P2O5-(50 – x)BaO-xNd2O3 (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 mol %) glasses. The amount of SnO was then varied while replacing BaO within the 50P2O5-(49 – x)BaO-1Nd2O3-xSnO compositions with x = 0, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 mol % with the aim of identifying the amount of tin that enhances Nd3+ emission optimally. Comprehensive experimental evaluations were carried out using X-ray diffraction (XRD), 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy, densitometry, Raman spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), dilatometry, UV–vis–NIR optical absorption, and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. The results were then analyzed to link the different physicochemical parameters to the variation in absolute and relative Sn2+ and Sn4+ concentrations as assessed by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy. The concentration of divalent tin for achieving the sensitized UV-excited NIR emission from Nd3+ ions attractive for optical devices is then finally endorsed.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Glass Preparation

The glasses were prepared by melting under ambient atmosphere using as raw materials P2O5 (Thermo Scientific, 98%), BaCO3 (Thermo Scientific, 99.8%), Nd2O3 (Thermo Scientific, 99.99%) and SnO (Thermo Scientific, 99%). SnO was added at the expense of BaO targeting the 50P2O5-(49 – x)BaO-1Nd2O3-xSnO (x = 0, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 mol %) nominal compositions. The different glasses prepared are summarized in Table with the assigned glass codes. The amount of Nd2O3 being fixed at 1 mol % follows a previous work where this concentration was found to produce maximum PL in the 50P2O5-(50 – x)BaO-xNd2O3 (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 mol %) glass system. The raw materials were weighed in the appropriate quantities (making about 25 g batches), thoroughly mixed and melted in porcelain crucibles at 1150 °C for 15 min, after which they were quenched in a heated steel mold. To remove mechanical/thermal stress, the glasses were annealed for 3 h at 420 °C (below the glass transition temperature). The glasses were subsequently cooled to room temperature (RT), and then cut and polished to ∼1 mm thick slabs for spectroscopic measurements. Glass samples were also quenched as glass cylinders and cut to a length (L) of about 2.54 cm for dilatometric measurements. Some pieces were crushed by mortar and pestle for powder XRD measurements while some grains were used for DSC.

1. Glass Codes and Nominal Compositions of the 50P2O5-(49 – x)BaO-1Nd2O3-xSnO (x = 0, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0 mol %) Glasses Synthesized.

| glass | P2O5 (mol %) | BaO (mol %) | Nd2O3 (mol %) | SnO (mol %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | 50.0 | 49.0 | 1.0 | |

| 1SnNd | 50.0 | 48.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 3SnNd | 50.0 | 46.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| 5SnNd | 50.0 | 44.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| 7SnNd | 50.0 | 42.0 | 1.0 | 7.0 |

| 9SnNd | 50.0 | 40.0 | 1.0 | 9.0 |

2.2. Measurements

Powder XRD characterization was performed at RT to confirm the amorphous nature of the glasses (crushed by mortar and pestle) with a PANalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71 Å). The acceleration voltage used was 60 kV and the current 40 mA.

119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements were carried out using a M6 Resonant Gamma-ray Spectrometer (SEE Co.) with a Kr/CO2 proportional counter and a 119mSn/CaSnO3 radioisotope source (Ritverc). All measurements were obtained with the sample and source at RT. The velocity axis was calibrated using a 57Co/Rh radioisotope source and a 25 μm thick α-Fe reference foil (Ritverc), and all isomer shifts are given relative to a natural abundance SnO2 powder at 0 mm/s.

Glass densities were determined by the Archimedes principle using distilled water as immersion liquid at RT in a Mettler-Toledo XSR Analytical Balance. The measurements were done in triplicate and the averages are reported (uncertainties in third decimal place). Various physical parameters that were useful for characterizing the glasses were then calculated by use of corresponding formulas. ,

Raman spectroscopy measurements were carried out on the polished glass slabs at RT with a Thermo Scientific DXR Raman microscope (532 nm laser with power at 10 mW). The instrument was calibrated using a proprietary autoalignment tool and a polystyrene film prior to data collection. The data was collected using the 10× MPlan objective with an acquisition time for each spectrum of 100 s. Baseline subtraction was then done using OriginPro and the spectra normalized for comparison.

DSC was carried out in a SDT650 calorimeter (TA Instruments) in alumina pans under nitrogen gas atmosphere (flow rate at 100 mL/min) at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The thermal parameters of interest [glass transition temperature (T g), onset of crystallization (T x ), peak crystallization temperature (T c)] were estimated using the instrument’s software (midpoint-inflection point for T g).

Dilatometry measurements were carried out for the ∼2.54 cm-long glass cylinders at a heating rate of 3 °C/min in an Orton dilatometer (model 1410B). The thermal parameters of interest such as the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), T g and the softening temperature (T s) were then estimated through the instrument’s software.

UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometry measurements were made on the ∼1 mm thick glass slabs taken at RT with an Agilent Cary 5000 double-beam spectrophotometer; air was always the reference.

The collection of PL emission and excitation spectra was done under static conditions (1 nm step size) at RT using a Horiba Fluorolog-QM spectrofluorometer with a Xe lamp. Emission decay curves were recorded using as excitation source a Xe flash lamp (∼2 μs pulse duration). The InGaAs detector was used for NIR measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD

Shown in Figure are the XRD patterns obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71 Å). The diffractograms show broad features toward small 2θ values characterizing long-range structural disorder. , Some intensity fluctuations are seen with the broad humps, yet the diffractograms do not show discrete crystallization peaks. The XRD results thus support that amorphous solids were realized for the set of glasses within the range of SnO concentrations considered.

1.

XRD patterns obtained for the various glasses with Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71 Å).

3.2. 119Sn Mössbauer Spectroscopy

Prior to the evaluation of the structural, thermal and optical properties of the glasses, we proceed at this point with tin speciation analysis by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy. The spectra obtained for the 1-9SnNd glasses are shown in Figure a–e. It is noticed that all samples show singlets near 0 mm/s indicative of Sn4+, while the presence of Sn2+ is evidenced by the quadrupolar doublets spanning 1–6 mm/s. ,,, The data thus shows that some SnO oxidation occurred for all glasses during the melting. This is in fact expected given that the synthesis was carried out under ambient atmospheric conditions, as similarly reported in various works. ,,, To estimate the relative amounts of Sn2+ and Sn4+, peak deconvolution was performed on the spectra as previously reported. While the Sn2+ doublet could be fit with two Lorentzian lines of equal width, the Sn4+ singlet was best fit with a Gaussian line shape; the fits were not improved any further using pseudo-Voigt lineshapes, so the minimal fitting model of one Gaussian and two Lorentzians was used for all spectra. The results are shown as the dashed traces in Figure a–e, where the cumulative fits are presented as solid traces. The relative percentage of Sn2+ in each glass was estimated from the prefactors of the normalized lineshapes obtained from these fits, and the values are shown in the respective panels of Figure for quick access. The complete spectral parameters and estimated percent abundances of Sn2+ and Sn4+ deduced for each glass are presented in Table . It is noticed that even though Sn4+ occurs in all glasses, most of the tin exists as divalent tin. The relative Sn2+ percent estimated for the 9SnNd glass of 85.5% is close to the 88% reported for a phosphate glass made similarly with 2 mol % Yb2O3 and 10 mol % SnO (each added in relation to P2O5) as also estimated by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy. Reasonable agreement is also observed with other reported barium phosphate glasses made similarly with 10 mol % additive SnO and containing Eu2O3 ([Sn2+] = 73.2%) or Pr2O3 ([Sn2+] = 81.6%) as appraised by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Thus, in the presence of merely trivalent rare earth oxides, the oxidation of SnO appears to be essentially driven by the oxidizing air atmosphere. This contrasts with the situation with Tb4O7, which was observed to exert an additional oxidizing effect on SnO. Herein, the Nd2O3 employed, which was constant in all glasses at 1 mol %, is not expected to promote such an oxidizing effect.

2.

119Sn Mössbauer spectra (open symbols) for the tin-containing glasses: (a) 1SnNd; (b) 3SnNd; (c) 5SnNd; (d) 7SnNd; and (e) 9SnNd. The corresponding deconvolutions employed for tin speciation are the dashed traces overlaid; the solid traces are the cumulative fits. The spectral parameters and estimated percent abundances of Sn2+ and Sn4+ deduced for each glass are summarized in Table .

2. Isomer Shift, Quadrupole Splitting, Line Width, and % Abundance of the Tin Species in the 1-9SnNd Glasses as Estimated from 119Sn Mössbauer Spectra.

|

119Sn Mössbauer parameter |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glass | component | isomer shift velocity (mm/s) | quadrupole splitting velocity (mm/s) | linewidth (mm/s) | % abundance |

| 1SnNd | Sn2+ | 3.79 | 1.58 | 1.73 | 77.8 |

| Sn4+ | –0.29 | 0 | 0.57 | 22.2 | |

| 3SnNd | Sn2+ | 3.78 | 1.58 | 1.51 | 82.2 |

| Sn4+ | –0.24 | 0 | 0.49 | 17.8 | |

| 5SnNd | Sn2+ | 3.79 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 78.2 |

| Sn4+ | –0.24 | 0 | 0.65 | 21.8 | |

| 7SnNd | Sn2+ | 3.71 | 1.55 | 1.55 | 81.9 |

| Sn4+ | –0.33 | 0 | 0.53 | 18.1 | |

| 9SnNd | Sn2+ | 3.77 | 1.58 | 1.55 | 85.5 |

| Sn4+ | –0.34 | 0 | 0.57 | 14.5 | |

Using the nominal amounts of SnO (Table ) and the relative percentages of Sn2+ and Sn4+ obtained from the 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy results (Table ), the absolute concentrations of Sn2+ and Sn4+ in mol % in the glasses were estimated. The results are shown in Table . It is observed that the concentration of Sn2+ increases continuously in the glass series up to a maximum value of 7.70 mol % Sn2+ for the 9SnNd glass with nominally 9.0 mol % SnO. On the other hand, the concentration of Sn4+ increases but reaches a maximum of ≈1.3 mol % in the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses. The estimated concentrations of the different tin species is an important aspect to consider in the interpretation of the various physicochemical properties herein assessed (vide infra). Meanwhile, the estimated concentrations of Sn2+ in mol % become useful in the evaluation of physical parameters following the assessment of glass densities considered next.

3. Concentrations of Sn2+ and Sn4+ Estimated for the 1-9SnNd Glasses Based on Mössbauer Spectroscopy Analysis (Table ) and the Nominal Concentrations of SnO (Table ).

| glass | Sn2+ (mol %) | Sn4+ (mol %) |

|---|---|---|

| 1SnNd | 0.78 | 0.22 |

| 3SnNd | 2.47 | 0.53 |

| 5SnNd | 3.91 | 1.09 |

| 7SnNd | 5.73 | 1.27 |

| 9SnNd | 7.70 | 1.31 |

3.3. Density and Basic Physical Properties

Table summarizes the densities obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses along with other physical quantities calculated. The density of the Nd glass is the lowest at 3.674 g/cm3, yet there is no trend afterward for the 1-9SnNd glasses, as the values fluctuate. This suggests that differences arise due to experimental variability. The molar masses of SnO (134.71 g/mol) and BaO (153.33 g/mol) are close, with the former having a somewhat lower value. All else the same, the substitution of BaO by SnO should lead to slightly lower density values. However, the analysis of the 119Sn Mössbauer spectra above indicated that SnO oxidized to some extent in the 1-9SnNd glasses. This could be interpreted as a partial conversion of SnO (134.71 g/mol) to SnO2 (150.71 g/mol) with molar mass similar to that of BaO (153.33 g/mol). In this context, the fluctuating density values obtained for the 1-9SnNd glasses may reflect several experimental factors such as oxygen uptake from air accompanying the SnO oxidation, i.e.

| 1 |

and changes in molar volumes (V m) of the glasses. Hence, to assess the latter parameter, V m, we proceed first to calculate the average molar mass (M av) of each glass by considering that the amounts of Sn2+ and Sn4+ (mol %) estimated from the 119Sn Mössbauer analysis (Table ) have associated equivalent amounts of SnO and SnO2. The M av values were then calculated from the following equation ,

| 2 |

where X i and M i are the mole fractions and molar masses of each component, respectively, with the mole fractions of SnO and SnO2 being determined from the 119Sn Mössbauer results. From the measured densities (ρ), the molar volumes were obtained from the known formula ,

| 3 |

4. Densities and Other Parameters Related to the Physical Properties of the Different Glasses.

| parameter | Nd | 1SnNd | 3SnNd | 5SnNd | 7SnNd | 9SnNd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| density, ρ (g/cm3) | 3.674 | 3.718 | 3.696 | 3.694 | 3.709 | 3.700 |

| average molar mass, M av (g/mol) | 149.47 | 149.32 | 148.99 | 148.71 | 148.37 | 148.00 |

| molar volume, V m (cm3/mol) | 40.68 | 40.16 | 40.31 | 40.26 | 40.01 | 39.99 |

| Nd3+ concentration, N Nd (×1020 ions/cm3) | 2.960 | 2.999 | 2.988 | 2.992 | 3.011 | 3.011 |

| Nd3+–Nd3+ mean distance, d Nd–Nd (Å) | 15.00 | 14.94 | 14.96 | 14.95 | 14.92 | 14.92 |

| Sn2+ concentration, N Sn (×1020 ions/cm3) | | 1.167 | 3.683 | 5.848 | 8.630 | 11.586 |

| Sn2+–Sn2+ mean distance, d Sn–Sn (Å) | | 20.47 | 13.95 | 11.96 | 10.50 | 9.52 |

| Sn2+–Nd3+ mean distance, d Sn–Nd (Å) | | 13.58 | 11.44 | 10.42 | 9.51 | 8.82 |

The M av and V m values are shown in Table along with the densities. It is seen that the average molar masses decrease continuously, although only slightly, within the Nd and 1-9SnNd glass series. Hence, the 9SnNd glass exhibited the lowest M av at 148.00 g/mol. The marginally decreasing trend thus follows with the prevalence of SnO in the glasses over SnO2. However, fluctuations are again observed regarding the molar volumes where the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses exhibited the lowest values at 40.01 and 39.99 cm3/mol, respectively.

We continue by calculating the concentration of optically relevant ions (e.g., luminescent) Nd3+ (N Nd) and Sn2+ (N Sn) in the glasses from the following equation ,

| 4 |

using the corresponding mole fractions (X i ), the glass densities (ρ), the average molar masses (M av), and Avogadro’s constant (N A). Here again, the mole fractions of Sn2+ were determined employing the 119Sn Mössbauer results. Then the mean distances between Nd3+ ions (d Nd–Nd) and the mean distances between Sn2+ ions (d Sn–Sn) were calculated from the individual ionic concentrations (N i ) as ,

| 5 |

Lastly, the mean distances between Sn2+ and Nd3+ ions (d Sn–Nd) were determined from the following equation

| 6 |

where N i and N j are the respective ion concentrations. All the obtained values for the different glasses as applicable are presented in Table . The Nd3+ concentrations, N Nd, vary only slightly within the 2.960–3.011 × 1020 ions/cm3 range in accord with changes in the molar volumes, as the Nd2O3 content was fixed at 1.0 mol %. Accordingly, the mean Nd3+–Nd3+ distances, d Nd–Nd, fluctuate only marginally within the 15.00–14.92 Å range throughout the entire glass set, as expected. In relation to divalent tin concentration, N Sn, it increases continuously in the 1-9SnNd glasses within the 1.167–11.586 × 1020 ions/cm3 range. Hence, we see that the interionic distances, d Sn–Sn, decrease steadily from 20.47 to 9.52 Å. Finally, the Sn2+–Nd3+ mean distances, d Sn–Nd, are similarly observed to become shorter with the increase in tin content in the 1-9SnNd glasses, decreasing from 13.58 to 8.82 Å. These various parameters will become relevant for the discussion and interpretation of the luminescence results later considered (vide infra).

3.4. Raman Spectroscopy Assessment

Shown in Figure are the Raman spectra obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses following baseline subtraction and normalization with respect to the strongest band for comparison. The different features observed are assigned in accordance with reports of similar glass compositions. ,,,,, Beginning at the low energy region, the tin-free Nd glass taken as reference presents a band around 686 cm–1 recognized as the in-chain symmetric stretching vibrations in P–O–P bridges, νs(POP), in Q 2 tetrahedral units (PO4 tetrahedra with 2 bridging oxygens, BOs). The small feature observed around 1005 cm–1 is credited to the symmetric stretch, νs(PO3 2–), in nonbridging oxygens (NBOs) concerning Q 1 units (PO4 tetrahedra with 1 BO). Then the Nd-doped glass shows the most intense band at about 1160 cm–1 due to the out-of-chain symmetric stretch in PO2 – groups, νs(PO2 –), occurring with the NBOs of the Q 2 units. Last of all, the corresponding asymmetric stretching vibrations, νas(PO2 –), are seen in the Nd glass around 1244 cm–1.

3.

Raman spectra obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses (normalized); main spectroscopic features in the Nd glass as reference are indicated (vertical dashed linesfrequencies displayed).

The Raman spectra for the 1-9SnNd glasses in Figure appear very similar to the spectrum of the Nd glass. This suggests a lack of significant structural alteration upon substituting BaO by SnO in the codoped glasses. To assist with the evaluation, shown in Table are the peak positions and full width at half-maximum (fwhm) values of the νs(POP) band (BO-related) as well as the νs(PO2 –) band (NBO-related). , Both bands exhibit a slight broadening with tin content, whereas variation in band frequencies are only minor. Overall, the data seems to support marginal depolymerization with the increase in tin content. This contrasts with the case where the rare earth codopant along with SnO was Tb4O7, which was observed to exert an oxidizing effect on SnO. There, the presence of Sn4+ was linked to the more clearly exhibited depolymerization effect. Hence, it appears in the present case that the minor changes in the Raman spectra of the 1-9SnNd glasses are induced by the relatively small amounts of Sn4+ ascertained (Table ), which can act as a network modifier to produce a slight structural disruption. ,

5. Spectral Positions and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) Values for the Bridging Oxygen (BO)-νs(POP) and Non-Bridging Oxygen (NBO)-νs(PO2 –) Raman Bands Obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd Glasses.

| BO-νs(POP) band |

NBO-νs(PO2

–) band |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| glass | peak (cm–1) | fwhm (cm–1) | peak (cm–1) | fwhm (cm–1) |

| Nd | 686 | 60 | 1160 | 31 |

| 1SnNd | 687 | 62 | 1159 | 33 |

| 3SnNd | 687 | 61 | 1159 | 33 |

| 5SnNd | 687 | 62 | 1159 | 32 |

| 7SnNd | 688 | 63 | 1158 | 33 |

| 9SnNd | 688 | 63 | 1158 | 36 |

3.5. Thermal Properties

Figure shows the DSC thermograms obtained for the different glasses under study. From these, the parameters of glass transition temperature, T g, onset of crystallization, T x , and peak crystallization temperature, T c, were estimated for each glass and are presented in Table . Added to Table is the parameter indicating thermal stability, ΔT = T x – T g. , The tin-free Nd glass taken as reference exhibited a T g at about 499 °C close to that reported for the undoped barium phosphate host of 497 °C. A crystallization peak was detected for the Nd glass with T c around 710 °C and an onset, T x , at 670 °C. The resulting thermal stability factor ΔT is then 171 °C, which represents an improvement over the un-doped host with ΔT reported at 148 °C. It is noticed in Table that the temperatures for all parameters are higher for the 1SnNd glass relative to the Nd reference. Especially noticeable is the increased T g estimated for the 1SnNd glass at 508 °C. An upward trend in the T g has been indicated to follow the increase in Sn4+ concentration (ascertained from X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy) in the DSC evaluation reported for barium phosphate glasses melted with SnO and Tb4O7. The shift in the glass transition to higher temperatures is likely due to the high field strength of Sn4+ ions acting as network modifiers. It then seems that the higher T g of the 1SnNd glass is related to the presence of Sn4+ determined by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy (Figure , Tables and ). On the other hand, the values of T g and T x exhibit decreasing trends for the 3-9SnNd glasses, and T c and ΔT are seen to fluctuate. The 9SnNd glass shows the lowest T g at 463 °C but the highest thermal stability ΔT = 191 °C. The decreasing trend in T g is contrary to the leading effect of Sn4+ ions and thus points to a more significant impact from Sn2+ contents evidenced to be significant for the 3-9SnNd glasses by the 119Sn Mössbauer analysis (Table ). This concurs with other works in ternary phosphate glasses, wherein a decrease in T g values has been observed with increasing SnO content. ,

4.

DSC thermograms obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses displaying the regions of glass transition temperature (T g), onset of crystallization (T x ), and crystallization temperature (T c); regions indicated for the 5SnNd glass (estimated values for all glasses presented in Table ).

6. Glass Transition Temperature (T g), Onset of Crystallization (T x ), Main Peak Crystallization (T c) Temperature, and Thermal Stability Parameter ΔT = T x – T g, Estimated for the Nd and 1-9SnNd Glasses from the DSC Profiles.

| glass | Tg (°C) | T x (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔT = T x – T g (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | 499 | 670 | 710 | 171 |

| 1SnNd | 508 | 684 | 723 | 176 |

| 3SnNd | 499 | 687 | 732 | 188 |

| 5SnNd | 485 | 661 | 711 | 176 |

| 7SnNd | 478 | 653 | 701 | 175 |

| 9SnNd | 463 | 654 | 704 | 191 |

We continue with evaluating the thermomechanical properties of the various glasses by means of the dilatometry data presented in Figure . The linear expansion regimes of the different curves appear similar for the different glasses. The main differences are noticed at high temperatures where the glasses go through the glass transition region and reach the peak dilatometric temperature. The thermal expansion profiles shown in Figure were then used to estimate T g as well as the parameters of dilatometric or softening temperature, T s, and the coefficient of thermal expansion, CTE, which was evaluated in the 50–400 °C range. The results for the different parameters obtained are presented in Table . It is noticed that the T g values are somewhat lower than those obtained from DSC (Table ), which is not uncommon. , However, the type of behavior seen in the DSC results (Table ) is similarly observed in the dilatometry results (Table ). The T g of the 1SnNd glass of 490 °C is higher than that of the Nd reference estimated at 486 °C (Table ), which points to the significant impact of Sn4+ ions, as similarly observed for glasses melted with SnO and Tb4O7. Krohn et al. performed a dilatometric analysis on a different tin-doped glass system, namely soda-lime silica glass, and consistently reported a noticeable influence by SnO2 for achieving a higher T g. Then, as seen in Table , the 3-9SnNd glasses exhibit a downward trend for the T g values relative to the 1SnNd glass. Consistent with this is also the behavior observed for the T s results in Table , which follow the same evolution as the T g, suggesting an overruling effect from Sn2+. It turns out that Krohn et al. also observed for tin-doped silica glasses doped with fixed tin oxide at 2 mol % that the T g and T s values decreased with increasing Sn2+ fraction. The data from the two different techniques herein thus harmonize and point to the noticeable effect of Sn4+ in the 1SnNd glass but a dominant influence from Sn2+ in the 3-9SnNd glasses that lowers the glass transition and softening temperatures.

5.

Dilatometric profiles obtained for the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses; the estimated values of glass transition temperature (T g), softening temperature (T s) and coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) are presented in Table .

7. Values of Glass Transition Temperature (T g), Softening Temperature (T s) and Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE, Estimated in the 50–400 °C Range) Obtained for the Different Glasses From Dilatometry.

| glass | Tg (°C) | Ts (°C) | CTE (×10–6 °C–1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | 486 | 510 | 14.6 |

| 1SnNd | 490 | 519 | 14.2 |

| 3SnNd | 475 | 507 | 14.1 |

| 5SnNd | 472 | 502 | 14.0 |

| 7SnNd | 468 | 490 | 14.0 |

| 9SnNd | 447 | 479 | 14.0 |

With respect to the CTE, it is interesting that the 1SnNd glass exhibits a value of 14.2 × 10–6 °C–1, a decrease compared to the Nd reference with CTE of 14.6 × 10–6 °C–1 (Table ). This indicates that a somewhat tighter glass network was produced with 1 mol % SnO added in place of BaO. On the other hand, the CTE of the 3SnNd glass is estimated at 14.1 × 10–6 °C–1 and those of the 5-9SnNd glasses are equally estimated at 14.0 × 10–6 °C–1 (Table ), all of which are more similar to that of the 1SnNd glass. Admittedly, disentangling the effects of the different oxidation states of tin on the thermal expansion of glasses is a challenging task. The present results at least do not contradict the dilatometric study of tin-doped silica glasses carried out by Krohn et al., where it was noticed that the CTE values were inclined to decrease in a similar manner with both SnO and SnO2. However, a contrast is seen with the case of the phosphate glasses melted with SnO and Tb4O7, wherein a small amount of SnO produced an increase in the CTE relative to the Tb-doped tin-free glass. In that instance, Tb4O7 exerted a major impact on SnO speciation, leading to tin being present mostly as the Sn4+ ions linked to the decreased rigidity. Additionally, as more Sn2+ was incorporated in the Tb-doped glasses relative to Sn4+, the CTE values tended to decrease but were never as low as those obtained for the tin-free Tb-doped ref . However, the presence of Sn4+ in the glasses studied in ref was also indicated to induce glass depolymerization. It is known that the varying extent of depolymerization in glasses can impact the CTE. For instance, a high degree of depolymerization is commonly linked to high CTE values in connection with looser glass networks. , It is then likely that the relatively high CTE values reported in ref reflected the effects of glass depolymerization in conjunction with the influence of tin in different oxidation states. In the present study, replacing BaO with SnO always produced a lower CTE, especially noticeable at low concentrations. In addition, the Raman spectroscopy analysis carried out did not support significant depolymerization, especially for the lowest SnO contents (Figure and Table ). Hence, in the present case the lower CTE in the 1SnNd glass could be linked to the lack of network depolymerization and the presence of the high field strength Sn4+ ions, which are also suggested to increase the T g and T s (vide supra). Thereafter, the increasing occurrence of Sn2+ (Table ) did not appear to further decrease the CTE to a significant extent. The fact that the 5SnNd, 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses had Sn4+ concentrations of 1.09, 1.27 and 1.31 mol % (Table ), respectively, is at least consistent with the lack of change in the CTE being related to similar quantities of Sn4+. Henceforth, we focus on evaluating the optical properties of the glasses, converging on the luminescent behavior highly impacted by divalent tin.

3.6. Optical Properties

The absorption spectra measured from the UV to the NIR for the different glasses are shown in Figure along with sample photographs. The glasses presented similarly a light purple color in accord with the comparable Nd3+ concentrations contained. The spectra in Figure in fact all display in like manner the different transitions characteristic of Nd3+ ions originating from the 4I9/2 ground state, most prominently the absorption peak around 583 nm linked to 4I9/2 → 4G5/2 + 2G7/2 transitions. ,, That the spectra are analogous harmonizes with the fact that the concentration of Nd2O3 in all glasses was kept constant at 1 mol %, in clear contrast with cases in which the neodymium content is varied in the glasses. , This upholds that the Nd and 1-9SnNd glasses had Nd3+ ions similarly incorporated. The incremental amounts of SnO added at the expense of BaO in the 1-9SnNd glasses have no distinct impact in the visible and NIR regions of the absorption spectra. This is because the Sn2+ centers absorb in the UV region, which is obscured by the absorption inherent to the glass host. ,,,, The presence of the divalent tin centers however becomes evident through their PL properties, as considered next.

6.

UV–vis–NIR absorption spectra obtained for the different glasses with some excited states associated with prominent absorption in Nd3+ ions from the 4I9/2 ground state indicated. The inset shows photographs of samples on a white background (from left to right: Nd, 1SnNd, 3SnNd, 5SnNd, 7SnNd and 9SnNd).

We continue with the PL investigation by considering excitation spectra obtained by monitoring the key emission from Nd3+ ions at 1056 nm due to the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 lasing transition. The spectra recorded for all glasses are shown in Figure , where we focus on the UV region relevant to the excitation of divalent tin centers. ,− ,− It is observed that the tin-free Nd glass lacks any excitation features in the region being non-resonant for exciting Nd3+ ions between 220 and 320 nm. Conversely, a new excitation band emerges in the 1SnNd glass peaking around 270 nm. This type of band has been associated with the excitation of singlet-to-singlet transitions (S 0 → S 1) in Sn2+ centers commonly linked with 2-fold coordination in glasses. ,− ,− ,, It is direct evidence of an energy transfer process leading to the sensitized emission from Nd3+ ions. This confirms the original work of Malashkevich et al. on the sensitization of Nd3+ PL by divalent tin and the more recent report from Bondzior and Lisiecki indicating a nonradiative interaction of the dipole–dipole type. It is also consistent with reports wherein divalent tin has been suggested to play a partial role in the enhancement of Nd3+ emission in phosphate glasses codoped with SnO/CuO , and SnO/Ag2O. It is noticed in Figure that the tin-related excitation band increases in intensity and broadens for the 3SnNd and 5SnNd glasses, ultimately shifting to about 280 and 290 nm, respectively. It then starts to be somewhat suppressed for the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glass while continuing to shift, displaying maxima around 295 and 300 nm, correspondingly. This behavior thus reflects the increase in Sn2+ concentration (Table ), suggesting an optimum Nd3+ emission due to Sn2+ → Nd3+ energy transfer for the 5SnNd glass. The subsequent intensity decrease observed for the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses thereafter suggests the concentration self-quenching effect inherent to Sn2+ pointed out by Malashkevich et al.

7.

PL excitation (PLE) spectra obtained for the different glasses by monitoring NIR emission from Nd3+ ions at 1056 nm.

The evolution of the Nd3+ luminescence with tin content is validated by the NIR emission spectra shown in Figure . The emission spectra were obtained for the different glasses using the respective maximum peak excitation wavelengths detected in Figure (indicated in parentheses next to each glass label in the legend in Figure ). The tin-free Nd glass PL spectrum was recorded as reference under excitation at 270 nm. It displays rather weak emission given that the excitation wavelength is not resonant with any of the main Nd3+ ions absorption peaks. However, the 1-9SnNd glasses clearly exhibit the typical Nd3+ 4F3/2 → 4I9/2, 4I11/2, 4I13/2 NIR transitions. ,, Here again, it is noticed that the PL intensity grows for the 3SnNd and 5SnNd glasses and then drops for the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses. Malashkevich et al. indicated that a PL quenching could take place for Nd3+ ions if the Sn2+ added to the glasses reduces the Fe3+ impurities to Fe2+, which is a known quencher of Nd3+. However, the Nd3+ PL evolution in Figure is consistent with the excitation spectra in Figure and points instead to the concentration quenching effect inherent to tin. In addition, emission decay curves were also obtained for the 1-9SnNd glasses by monitoring Nd3+ 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 emission at 1056 nm under excitation of the Sn2+ centers between 270 and 300 nm. The data are shown as semilog plots in Figure with the excitation wavelengths used for each glass specified in the legend. The curves clearly exhibit exponential behavior and were therefore fit by a first-order exponential decay function ,

| 7 |

where I(t) is the time-dependent luminescence intensity, I 0 the initial intensity, and τ the excited state lifetime. The values obtained for the 1SnNd, 3SnNd, 5SnNd, 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses were 231.1 (±0.2), 235.6 (±0.2), 234.1 (±0.2), 235.0 (±0.2) and 216.5 (±0.2) μs, respectively (values also shown in Figure ). These lifetimes are comparable with those reported for similar glasses containing 1 mol % Nd2O3. For instance, a Nd3+ 4F3/2 lifetime of 212 (±1) μs was estimated under resonant Nd3+ excitation at 803 nm for the 50P2O5-49BaO-1Nd2O3 composition, whereas a value of 227 (±1) μs was deduced for 50P2O5-47BaO-2MnO-1Nd2O3 glass. Hence, significant production of Fe2+ impurities by Sn2+ does not seem to be the source of the Nd3+ quenching. The similarity of the lifetimes for 1-9SnNd relates to the comparable Nd3+-Nd3+ distances found for the glasses within 14.92–15.00 Å (Table ). A concentration quenching effect, wherein high Nd3+ concentrations lead to interionic distances sufficiently short to allow excitation migration , is then not likely. On the other hand, looking at Table it is seen that the most favorable Sn2+ concentration was that for the 5SnNd glass of 5.355 × 1020 ions/cm3, with associated Sn2+–Sn2+ and Sn2+–Nd3+ mean distances of 12.32 and 10.62 Å, respectively. Although shorter Sn2+–Nd3+ distances were found for the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses (Table ), which would be favorable for the Sn2+ → Nd3+ transfer, it seems that the accompanying shorter Sn2+–Sn2+ distances ultimately trigger a concentration quenching effect that becomes detrimental.

8.

NIR emission spectra obtained for different glasses (excitation wavelengths indicated in parentheses next to each glass label in the legend).

9.

Semilog plots of the emission decay curves obtained for the 1-9SnNd glasses under excitation of divalent tin centers (excitation wavelengths used for each glass specified in the legend) while monitoring NIR emission at 1056 nm. The lifetimes estimated from single exponential fits are shown above each trace (the numbers in parentheses represent the uncertainties in the last digits).

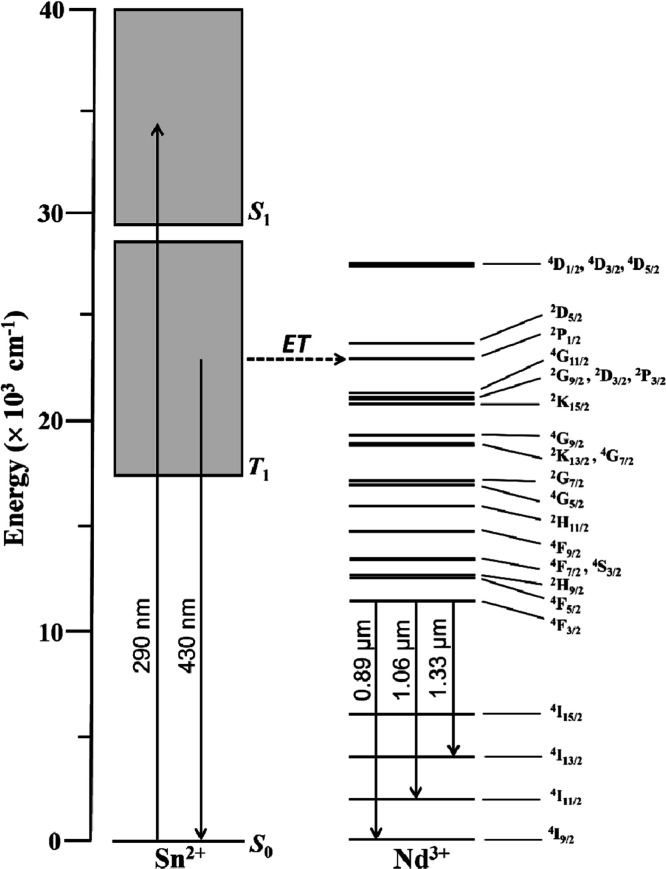

In Figure , the visible emission stemming from divalent tin is assessed for the different glasses under the relevant excitations linked to S 0 → S 1 transitions in Sn2+ (the excitation wavelengths used for each glass are specified in the legend). The tin-free Nd glass was excited for reference purposes at 270 nm and again shows no significant emission, as expected. On the contrary, the 1SnNd glass shows a broad emission band with a maximum around 410 nm. This type of PL has been associated with the emission of triplet-to-singlet transitions (T 1 → S 0) in Sn2+ centers in glasses. ,,− ,− The broad band intensifies and shifts slightly toward longer wavelengths for the 3SnNd and 5SnNd glasses and then diminishes for the 7SnNd and 9SnNd glasses. This behavior resembles that observed in the excitation spectra in Figure and the NIR emission in Figure , thus supporting the tin-related concentration self-quenching effect. The spectra of the 1-9SnNd glasses in Figure all show dips that correspond with Nd3+ absorption, as evidenced by the absorption spectrum of the Nd glass overlaid. This effect is proof of a resonant radiative energy transfer from the excited triplet states (T 1) of divalent tin to the rare-earth ions. ,, The nature of the Sn2+ → Nd3+ energy transfer was further investigated by Bondzior and Lisiecki through decay kinetic analyses in the context of the Inokuti-Hirayama model, indicating a nonradiative interaction of the dipole–dipole type. Herein, the processes involving Sn2+ and Nd3+ ions can be represented with the schematic diagram shown in Figure . Optical absorption (e.g., at 290 nm as with the 5SnNd glass) leads to the excitation of the singlet state (S 1) in Sn2+ centers, after which intersystem crossing populates the emitting T 1 states. The Sn2+ centers can then emit broadly (inhomogeneous broadening) as seen in Figure , which is illustrated in Figure with 430 nm emission since it is also resonant with the 2P1/2 state in Nd3+ ions. Alternatively, the excited Sn2+ centers can transfer the energy to resonant energy levels in Nd3+ ions, such as the 2P1/2 state as illustrated in Figure . Besides the 2P1/2 state, other resonant states in Nd3+ likely involved are 4D1/2, 4D3/2, 4D5/2, 2D5/2, 4G11/2, 2G9/2, 2D3/2, 2P3/2, 2K15/2, 4G9/2, 2K13/2 and 4G7/2. Subsequently, these excited states then decay nonradiatively to the 4F3/2 metastable state, leading to the radiative relaxation in the NIR due to 4F3/2 → 4I9/2, 4I11/2, 4I13/2 transitions (Figure ).

10.

Visible emission spectra obtained for the different glasses (excitation wavelengths indicated in parentheses next to each glass label in the legend). The absorption spectrum of the Nd glass is overlaid to show the spectral overlap with absorption (Nd3+ Abs).

11.

Simplified energy level diagram of Sn2+ and Nd3+ ions illustrating the excitation of the S 0 → S 1 transitions in Sn2+ at 290 nm (e.g., 5SnNd glass), the emission from the T 1 state at 430 nm, and the energy transfer (ET) to the 2P1/2 resonant level in Nd3+ ions leading to the radiative transitions from the 4F3/2 emitting state (nonradiative relaxations omitted).

4. Summary and Conclusions

Recapitulating, glasses were prepared by the melt-quenching technique with 50P2O5-(49 – x)BaO-1Nd2O3-xSnO (x = 0, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 mol %) compositions for a holistic study of various physicochemical properties, ultimately resulting in evaluation of the optimum conditions for the UV-excited Sn2+-sensitized NIR emission from Nd3+ ions. The investigation encompassed measurements by XRD, 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy, densitometry, Raman spectroscopy, DSC, dilatometry, optical absorption, and PL spectroscopy. The glasses were confirmed to be X-ray amorphous, whereas Raman spectroscopy showed no significant structural variation with SnO added at the expense of BaO. 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy was used for evaluating the speciation of tin in the glasses, showing that Sn2+ occurrence was favored even though some SnO oxidation occurred in the melts. The densities showed fluctuations which were rationalized in terms of SnO and SnO2 contents in correspondence with the Sn2+ and Sn4+ concentrations determined by 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy. Other physical parameters were then determined such as the Sn2+–Sn2+ and Sn2+–Nd3+ mean distances, which decreased with increasing nominal SnO concentrations. Thermal analyses by DSC and dilatometry suggested that Sn2+ was mostly influencing the glass transition and softening temperatures, showing a decreasing trend in the codoped glasses. However, the thermal expansion coefficients first decreased but then remained steady at high nominal SnO contents, likely connected with the lack of network depolymerization and the presence of relatively low amounts of Sn4+ ions with high field strength.

With respect to the optical properties, the absorption spectra appeared similar as expected for the fixed concentration of Nd2O3 of 1 mol % and the lack of influence from tin species in the visible and NIR regions. The PL evaluation then evidenced that exciting Sn2+ centers in the UV produced the sensitized NIR emission from Nd3+ ions. This was further observed to be maximized for SnO added at 5 mol % corresponding to about 3.9 mol % Sn2+ based on 119Sn Mössbauer spectroscopy. Higher tin concentrations were found to exhibit decreased intensities for the Nd3+ 4F3/2 → 4I9/2, 4I11/2, 4I13/2 NIR transitions, concurring with the evolution of Sn2+ PL. The Nd3+ lifetimes were evaluated and found to be comparable among the different samples. Accordingly, the presence of a significant quenching channel depopulating the 4F3/2 state in Nd3+ ions is not likely to produce the decreased NIR emission at high tin content. Instead, the concentration self-quenching effect inherent to Sn2+ ions is suggested to be the limiting factor in optimizing the nonresonant UV-excited NIR emission from Nd3+ ion via divalent tin centers.

Acknowledgments

J.A.J. is grateful the College of Science and Mathematics (COSM) and the Department of Biochemistry, Chemistry, and Physics (BCP) at Georgia Southern University (GSU) for financial support. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under award DE-SC0019429, which provided the instrumental resources for the Mössbauer spectroscopy work.

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT: Jose A. Jimenez conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Dugan Hayes formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, resources, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Solaleh Farnia formal analysis, investigation, methodology; Michael Vautier formal analysis, methodology.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Campbell J. H.. Recent advances in phosphate laser glasses for high-power applications. Proc. SPIE. 1996;10286:1028602. doi: 10.1117/12.245185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. H., Suratwala T. I.. Nd-doped phosphate glasses for high-energy/high-peak-power lasers. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2000;263–264:318–341. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3093(99)00645-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sontakke A. D., Biswas K., Mandal A. K., Annapurna K.. Concentration quenched luminescence and energy transfer analysis of Nd3+ ion doped Ba-Al-metaphosphate laser glasses. Appl. Phys. B: Laser Opt. 2010;101:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00340-010-4010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iparraguirre I., Azkargorta J., Balda R., Krishnaiah K. V., Jayasankar C. K., Al-Saleh M., Fernández J.. Spontaneous and stimulated emission spectroscopy of a Nd3+-doped phosphate glass under wavelength selective pumping. Opt. Express. 2011;19:19440–19453. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.019440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., He D., Li S., Chen W., Hu L.. Investigation on thermal properties of a new Nd-doped phosphate glass. Ceram. Int. 2014;40:13389–21339. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.05.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. S., Kumar V. R., Zhydachevskii Ya., Suchocki A., Piasecki M., Gandhi Y., Kumar V. R., Veeraiah N.. Luminescence emission features of Nd3+ ions in PbO-Sb2O3 glasses mixed with Sc2O3/Y2O3/HfO2 . Opt. Mater. 2017;69:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2017.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neelima G., Venkata Krishnaiah K., Ravi N., Suresh K., Tyagarajan K., Jayachandra Prasad T.. Investigation of optical and spectroscopic properties of neodymium doped oxyfluoro-titania-phosphate glasses for laser applications. Scripta Mater. 2019;162:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramprasad P., Basavapoornima Ch., Depuru S. R., Jayasankar C. K.. Spectral investigations of Nd3+:Ba(PO3)2+La2O3 glasses for infrared laser gain media applications. Opt. Mater. 2022;129:112482. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Quiñonero M., Azkargorta J., Iparraguirre I., Jiménez-Riobóo R. J., Tricot G., Shao C., Muñoz F., Fernández J., Balda R.. Dehydroxylation processing and lasing properties of a Nd alumino-phosphate glass. J. Alloys Compd. 2022;896:163040. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.163040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu A., Al-Dossari M., EL-Gawaad N. S. A., Gelija D., Ganesha K. N., Srinatha N.. Structural, optical and luminescence properties of Nd3+ ions in B2O3+SiO2+TeO2+Na2O glasses. Opt. Mater. 2023;136:113436. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Holistic assessment of NIR-emitting Nd3+ activated phosphate glasses: A structure-property relationship study. ACS Org. Inorg. Au. 2024;4:338–349. doi: 10.1021/acsorginorgau.3c00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. G., Gomulka S.. Enhanced performance of Nd laser glass by double doping with Cr. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1979;12:187–194. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/12/2/005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed N. T., Hirayama C., Davis E. K.. Laser action in neodymium-doped glass produced through energy transfer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1965;7:170–172. doi: 10.1063/1.1754362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Physical, thermal, and optical properties of Mn2+ and Nd3+ containing barium phosphate glasses. ACS Phys. Chem. Au. 2024;4:363–374. doi: 10.1021/acsphyschemau.4c00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malashkevich G. E., Bazylev A. G., Blinov A. L., Borik M. A., Voĭtovich A. P., Kalinov V. S., Tadéush V. N.. Sensitization of neodymium ion luminescence by divalent tin. Sov. J. Quantum Electron. 1991;21:601–605. doi: 10.1070/QE1991v021n06ABEH003893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondzior B., Lisiecki R.. Divalent tin activator for Nd3+/Yb3+ emission in lanthanum borate glass and its impact on inter-ionic phenomena and thermometry. J. Alloys Compd. 2024;1007:176471. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.176471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Sendova M.. Near-UV sensitized 1.06 μm emission of Nd3+ ions via monovalent copper in phosphate glass. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015;162:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2015.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Lysenko S., Sendova M., Zhao C.. Excited-state dynamics and enhanced near-IR emission in Nd3+-structurally activated aluminophosphate glass containing silver and tin. Opt. Mater. 2015;46:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kindrat I. I., Padlyak B. V., Lisiecki R., Adamiv V. T.. Spectroscopic and luminescent properties of the lithium tetraborate glass co-doped with Nd and Ag. J. Alloys Compd. 2021;853:157321. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Sendova M., Zhao C.. Efficient energy transfer and enhanced near-IR emission in Cu+/Nd3+-activated aluminophosphate glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015;98:3087–3093. doi: 10.1111/jace.13727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masai H., Takahashi Y., Fujiwara T., Matsumoto S., Yoko T.. High photoluminescent property of low-melting Sn-doped phosphate glass. Appl. Phys. Express. 2010;3:082102. doi: 10.1143/APEX.3.082102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segawa H., Inoue S., Nomura K.. Electronic states of SnO-ZnO-P2O5 glasses and photoluminescence properties. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2012;358:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2012.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masai H., Tanimoto T., Okumura S., Teramura K., Matsumoto S., Yanagida T., Tokuda Y., Yoko T.. Correlation between preparation conditions and the photoluminescence properties of Sn2+ centers in ZnO–P2O5 glasses. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2014;2:2137–2143. doi: 10.1039/C3TC32259A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Blue-emitting phosphate glasses synthesized via reduction of tin(IV) by silicon. Opt. Mater. 2017;66:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2017.01.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C., Baccaro S., Xing Z., Yan Q., Wang S., Chen G.. Different luminescence behaviors of SnO2/Eu3+ and SnO2/Tm3+ co-doped phosphate glasses. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010;492:123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Fachini E. R.. Origin of light emission and enhanced Eu3+ photoluminescence in tin-containing glass. J. Rare Earths. 2015;33:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0721(14)60378-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Ren J., Liu Y., Chen G.. Broad blue-green-red emissions of SnO2/Pr3+ co-doped phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2012;358:2961–2963. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2012.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Sendova M., Rosim Fachini E.. UV-stimulated near-IR emission of Pr3+ in phosphate glass via twofold-coordinated Sn centers. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2014;67:359–362. doi: 10.1016/j.infrared.2014.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Twofold-coordinated tin centers as UV sensitizers of trivalent dysprosium ions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2014;387:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Emission properties of Sn2+ and Sm3+ co-doped barium phosphate glass. J. Electron. Mater. 2014;43:3588–3592. doi: 10.1007/s11664-014-3240-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Sendova M., Hosterman B., Haney L.. Sn centers-mediated enhancement of 1.53 μm emission of Er3+ ions in phosphate glass. Mater. Lett. 2014;131:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajanikanth P., Gandhi Y., Veeraiah N.. Enrichment of orange emission of Er3+ ion with Sn4+ ion as sensitizer in lithium lead phosphate glass system. Opt. Mater. 2015;48:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2015.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi Y., Rajanikanth P., Sundara Rao M., Ravi Kumar V., Veeraiah N., Piasecki M.. Effect of tin ions on enhancing the intensity of narrow luminescence line at 311 nm of Gd3+ ions in Li2O single bond PbO single bond P2O5 glass system. Opt. Mater. 2016;57:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2016.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Hayes D., Hasselbrink C.. UV to NIR down-shifting in Yb3+-doped phosphate glass via divalent tin centers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2022;126:18421–18428. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c04429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Physical and spectroscopic properties of variable Yb2O3 doped phosphate glasses containing SnO as UV sensitizer for Yb3+ NIR emission. Opt. Mater. 2023;141:113984. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.-m., Gan G.-y.. Photoluminescence and energy transfer in Sn2+, Tb3+ co-activated P2O5-Li2O-ZnO glasses with tailored emission. ECS Solid State Letters. 2014;3:R36–R39. doi: 10.1149/2.0021408ssl. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Hayes D., Antolini C., Reinhart B. J.. XANES analysis of phosphate glasses melted with Tb4O7 and SnO: Evaluating the impact of valence states on structural, thermal, and luminescent properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023;25:32688–32698. doi: 10.1039/D3CP04784A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert E., Montagne L., Delevoye L., Palavit G., Wattiaux A.. NMR and Mössbauer characterization of tin(II)–tin(IV)–sodium phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2004;345–346:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2004.07.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn M. H., Hellmann J. R., Mahieu B., Pantano C. G.. Effect of tin-oxide on the physical properties of soda-lime–silica glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2005;351:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2005.01.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton J. E., Latifzadeh L., Fletcher J. P., Risbud S. H.. Raman spectroscopy of calcium phosphate glasses with varying CaO modifier concentrations. Chem. Mater. 1991;3:195–200. doi: 10.1021/cm00013a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saoût G., Simon P., Fayon F., Blin A., Vaills Y.. Raman and infrared study of (PbO)x(P2O5)(1–x) glasses. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2002;33:740–746. doi: 10.1002/jrs.911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Fachini E. R., Zhao C.. XPS and 31P NMR inquiry of Eu3+-induced structural modification in SnO-containing phosphate glass. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1164:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.03.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Shen X., Huang Q., Zhang J., He Y., Liu T., Lu A.. Study on the structure, fining and properties of non-alkali aluminoborosilicate glasses containing SnO2 . J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2021;559:120670. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2021.120670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Fang L., Shen J., Pascual M. J., Zhang T.. Tuning the interfacial reaction between bismuth-containing sealing glasses and Cr-containing interconnect: effect of ZnO. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015;98:3797–3806. doi: 10.1111/jace.13779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A.. Spectroscopic and dilatometric analysis of low-melting bismuth borate glasses in the Bi2O3–BaO–Li2O–B2O3 quaternary. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;255:123635. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.123635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Lima A. M., de Queiroz M. N., dos Santos Bianchi G., Astrath N. G. C., Pedrochi F., Steimacher A., Barboza M. J.. Structural and thermal properties of Yb:CaBTeX glasses as a function of TeO2 content. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2022;595:121848. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T., Enomoto T., Nogami M.. β-Band photoluminescence and Sn-E′ center generation from twofold-coordinated Sn centers in SiO2 glasses produced via sol–gel method. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;45:5078–5083. doi: 10.1143/JJAP.45.5078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. A., Lysenko S., Liu H., Fachini E., Resto O., Cabrera C. R.. Silver aggregates and twofold-coordinated tin centers in phosphate glass: A photoluminescence study. J. Lumin. 2009;129:1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.04.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann P. R., Campbell J. H.. Nonradiative energy losses and radiation trapping in neodymium-doped phosphate laser glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002;85:1061–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00223.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.