Abstract

Background

Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading (POCL) has shown benefits in non-diabetic patients, but its use in patients with diabetes remains controversial. Concerns about potential hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes have led to conflicting evidence and varied clinical practices.

Objective

To assess the impact of POCL on clinical outcomes after surgery in patients with diabetes.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed 679 patients with diabetes undergoing elective surgery from 2020 to 2023, divided into POCL and fasting groups. After 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM), 410 patients were analyzed. Primary outcomes included postoperative blood glucose levels; secondary outcomes were including glycemic variability, pulmonary infections, hospital stay length, and costs.

Results

After PSM, POCL was associated with significantly lower blood glucose levels on the first postoperative day compared to the fasting group (11.03 [9.43–12.77] vs. 11.37 [9.77–13.20], P = 0.045). No significant differences were observed in glycemic variability. POCL patients demonstrated shorter postoperative hospital stays (5.10 [3.00-7.70] vs. 5.90 [3.80–8.50], P = 0.022). Multivariate analysis revealed that POCL independently predicted reduced hospitalization costs (β=-3417.49, 95% CI [-6358.52, -476.46], P = 0.023) and shorter hospital stays (β=-1.21, 95% CI [-1.83, -0.60], P < 0.001). Higher ASA scores and longer surgical durations were associated with increased costs, while prolonged surgeries correlated with greater pulmonary infection risk (OR = 1.005, 95% CI [1.003–1.008], P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Despite previous concerns, POCL appears to be associated with lower early postoperative blood glucose levels, shorter hospital stays, and reduced costs in patients with well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c < 7.5%). It may be a safe and effective perioperative strategy for this specific population, though individualized assessment remains essential.

Keywords: Diabetes, Surgery, Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading (POCL), Glycemic control, Clinical outcomes

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a global chronic condition with a steadily rising prevalence [1]. As the number of diagnosed diabetes cases increases, so does the need for surgical interventions. Surgery imposes significant physiological stress, which can exacerbate insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and other metabolic disturbances, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative complications [2]. For patients with diabetes, these risks are heightened due to existing metabolic abnormalities [3]. Consequently, meticulous preoperative management is crucial for this patient population.

Traditionally, patients fasted for extended periods before surgery to reduce anesthesia-related complications. However, this practice may paradoxically worsen perioperative metabolic disturbances [2, 4]. Preoperative carbohydrate loading (POCL) has emerged as an alternative strategy, aimed at alleviating insulin resistance, enhancing patient comfort, and accelerating recovery [5–7]. While initially developed for patients without diabetes, the application of POCL in patients with diabetes has been controversial due to concerns about exacerbating perioperative glycemic control [8–10]. Nonetheless, recent insights into diabetes pathophysiology and advances in perioperative management have renewed interest in the potential benefits of POCL for patients with diabetes [1, 11–13].

This retrospective study analyzes data from patients with diabetes who underwent POCL prior to surgery, evaluating its impact on glycemic control, surgical safety, and patient recovery. Our findings aim to assess POCL efficacy to guide perioperative management, promote personalized medicine, and enhance the quality of life for patients with diabetes.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College approved this retrospective study (2023CYFYIRB-BA-May03) and waived the requirement for informed consent. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations [14].

Carbohydrate loading protocol

The carbohydrate drinks were prepared by the nutrition department and administered per medical orders, with instructions for patients to consume them. Patients in the carbohydrate group were instructed to drink 400 mL of the carbohydrate solution (containing 26.8 g of carbohydrates, 4.9 g of protein, 10 g of whey protein, 0.67 g of fat, 11 g of dietary fiber, 20 g of maltodextrin, along with minor amounts of electrolytes and trace vitamins) between 21:00 and 23:00 on the evening before surgery. Additionally, they were given 200 mL of the carbohydrate solution (containing 10 g of maltodextrin) 2 h before surgery.

To verify patients’ adherence to the prescribed carbohydrate intake protocol, we employed a two-step verification process. First, we confirmed the documented medical orders in the patient records. Second, we reviewed the preoperative adherence status recorded in the anesthesia information system, which was based on direct inquiries by the anesthesiologist during the preoperative assessment. Only patients who satisfied both verification criteria were considered to have successfully followed the Perioperative Oral Carbohydrate Loading (POCL) protocol.

Study design, participants and sample size

To evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of POCL in patients with diabetes, we retrospectively collected data from the hospital’s electronic medical records (EMRs) and Anesthesia Information Management Systems (AIMS) for the period from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2023. Patients were divided into the POCL group and the Fasting group based on whether they consumed carbohydrates preoperatively.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Aged 18–75 years, regardless of gender. (2) Undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. (3) Diagnosed with Type II diabetes. Exclusion criteria were: (1) BMI ≥ 35 kg/m². (2) Significant abnormalities in cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal function. (3) History of mental or neurological diseases, alcoholism, drug abuse, long-term use of opioids or sedatives. (4) ASA classification ≥ Class IV. (5) Missing data. (6) Suboptimal preoperative carbohydrate loading due to incomplete adherence to medical instructions.

Sample size: This study, conducted as a retrospective analysis, didn’t include a priori sample size calculations. We adopted a full-sample analysis approach, including all eligible cases, to maximize statistical power and enhance the reliability of the results. This method allowed us to obtain a large, representative sample that accurately reflects clinical practice during the study period.

Data collection

Eligibility assessment was conducted using EMRs and AIMS, adhering to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two trained investigators independently abstracted data, including patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and laboratory examinations. Discrepancies were resolved through consultation with a senior researcher.

Data were entered into a standardized electronic spreadsheet with dual-entry to minimize errors. Rigorous data cleaning included logical checks, strategies for handling missing data, and outlier detection. Inconsistencies were verified and corrected by revisiting primary medical records.

Patients lacking baseline data indicators were excluded from our analysis. The majority of missing data was concentrated in postprandial glucose values for postoperative days 2 and 3. We identified 35 missing glucose data points on postoperative day 2 and 135 missing data points on postoperative day 3. To address these missing values, we employed multiple imputation techniques, generating five imputed datasets.

It is important to note that our Department of Anesthesiology did not routinely monitor blood glucose levels for most patients with well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c < 7.5%) during the perioperative period unless clinically indicated. Additionally, due to varying surgical scheduling patterns, the glucose monitoring data collected by ward nursing staff exhibited irregular timing and substantial missing values. Consequently, we were unable to extract meaningful day-of-surgery glucose data from patient medical records and the Anesthesia Information Management System. Our analysis therefore focuses on postoperative days 1–3, when more systematic monitoring was conducted according to standard postoperative care protocols.

Outcomes

The primary outcome: For assessment of postoperative glycemic control, we selected three postprandial blood glucose values (measured approximately one hour after each meal) daily from patient records. Glycemic variability was calculated as the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as: CV (%) = (blood glucose standard deviation / mean blood glucose value) × 100%. This standardized measure allows for comparison of glucose fluctuations independent of absolute glucose levels. The secondary outcomes include the incidence of postoperative pulmonary and wound infections, postoperative hospital stay, hospitalization expenses.

Postoperative diabetes management was assessed by tracking insulin requirements, including continued preoperative insulin therapy, new insulin initiation, and continuous insulin infusion requirements, as well as ICU admission rates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 27.0, IBM Corp.) and R (version 4.4.1). To reduce bias, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance baseline characteristics between the two groups. Propensity scores were calculated using logistic regression, and standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated to assess balance; an SMD < 0.1 indicated good balance.

Descriptive statistics were performed, including means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables.

Before PSM, group comparisons were made using the independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. After PSM, group comparisons were made using the paired - samples t-test or Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank, and the McNemar’s test for categorical variables. Binary logistic and multiple linear regression analyses were used to control for confounding factors. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 679 participants were enrolled in this study, comprising 212 patients in the POCL group and 467 patients in the Fasting group. To mitigate selection bias and balance baseline characteristics between groups, we employed propensity score matching, which yielded a final analytical cohort of 410 participants (205 patients per group). The detailed patient selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1, while Table 1 presents a comprehensive comparison of baseline characteristics between the matched groups.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process

Table 1.

Comparison of general characteristics between groups

| Before PSM | SMD | P | After PSM | SMD | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCL Group (212) | Fasting Group (467) | POCL Group (205) | Fasting Group (205) | |||||

| Sex, Female (n, %) | 119 (56.13%) | 299 (64.03%) | 0.162 | 0.050 | 113 (55.12%) | 112 (54.63%) | 0.010 | 0.921 |

| Age (Years) |

61.50 [54.00–68.25] |

62.00 [53.00–69.00] |

0.009 | 0.987 |

61.00 [54.00–69.00] |

61.00 [53.00–69.00] |

0.022 | 0.885 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

24.75 [22.05–26.85] |

24.17 [22.22–26.56] |

0.038 | 0.530 |

24.73 [22.02–26.81] |

24.56 [22.04–27.18] |

0.058 | 0.727 |

| MAP (mmHg) |

94.67 [88.25–103.00] |

95.67 [88.67–104.00] |

0.022 | 0.560 |

95.00 [88.67–103.00] |

95.33 [88.67–102.67] |

0.004 | 0.991 |

| HbA1c |

7.25 [6.50 9.00] |

7.30 [6.40 9.10] |

0.03 | 0.787 |

7.30 [6.50–9.00] |

7.30 [6.40–9.00] |

0.005 | 0.970 |

| Anesthesia (n, %) | 0.013 | 0.873 | 0.013 | 0.896 | ||||

| General anesthesia | 176 (83.02%) | 390 (83.51%) | 170 (82.93%) | 169 (82.44%) | ||||

| Regional anesthesia | 36 (16.98%) | 77 (16.49%) | 35 (17.07%) | 36 (17.56%) | ||||

| Departments (n, %) | 0.618 | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 1.000 | ||||

| Gynecology Department | 19 (8.96%) | 112 (26.12) | 19 (9.27%) | 19 (9.27%) | ||||

| Thyroid and Breast Surgery Department | 7 (3.30%) | 48 (10.28%) | 7 (3.41%) | 7 (3.41%) | ||||

| Urology Department | 63 (29.72%) | 125 (26.77) | 63 (30.73%) | 64 (31.22%) | ||||

| Thoracic Surgery Department | 52 (24.53%) | 59 (12.63%) | 45 (21.95%) | 44 (21.46%) | ||||

| Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery Department | 71 (33.49%) | 113 (24.20%) | 71 (34.63%) | 71 (34.63%) | ||||

| Surgical Duration (min) |

200.00 [150.00–332.50] |

220.00 [150.00–310.00] |

0.004 | 0.947 |

200.00 [150.00–325.00] |

195.00 [135.00–300.00] |

0.012 | 0.393 |

| ASA (n,%) | 0.002 | 0.982 | 0.052 | 0.596 | ||||

| II | 145 (68.40%) | 319 (68.31%) | 142 (69.27%) | 137 (66.83%) | ||||

| III | 67 (31.60%) | 148 (31.69%) | 63 (30.73%) | 68 (33.17%) | ||||

| Hypertension (n,%) | 96 (45.28%) | 228 (48.82%) | 0.071 | 0.392 | 95 (46.34%) | 93 (45.37%) | 0.020 | 0.843 |

| PCA | 114 (53.77%) | 272 (58.24%) | 0.090 | 0.276 | 109 (53.17%) | 109 (53.17%) | < 0.001 | 1.000 |

| COPD (n,%) | 10 (4.72%) | 18 (3.83%) | 0.043 | 0.600 | 10 (4.88%) | 6 (2.93%) | 0.101 | 0.308 |

| CHD (n,%) | 15 (7.08%) | 41 (8.78%) | 0.063 | 0.454 | 15 (7.32%) | 17 (8.29%) | 0.036 | 0.713 |

| Diabetes drug (n,%) | 143 (67.45%) | 317 (67.88%) | 0.009 | 0.912 | 137 (66.83%) | 135 (65.85%) | 0.021 | 0.834 |

| Insulin | 17 (8.02%) | 37 (7.92%) | 16 (7.80%) | 17 (8.29%) | ||||

| Non-Insulin | 126 (59.43%) | 280 (59.96%) | 121 (59.02%) | 118 (57.56%) | ||||

Note: PSM: Propensity score matching; MAP: Mean arterial pressure; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHD: Coronary heart disease; PCA: Patient - controlled analgesia; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Diabetes drug: At least 6 months of regular antidiabetic medication use. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance

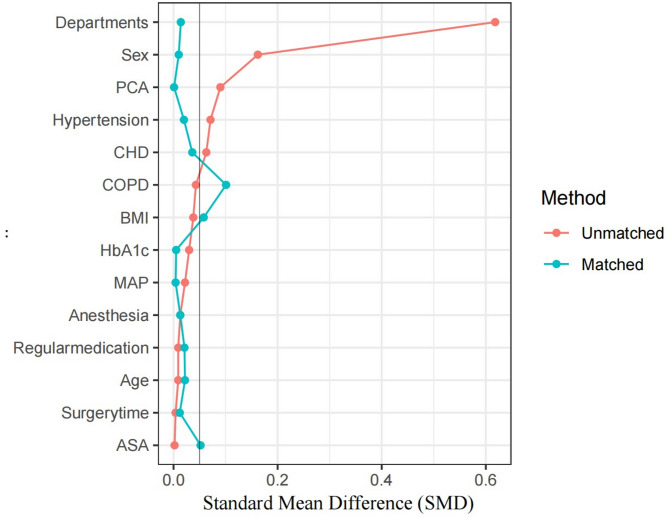

Propensity score matching

To reduce selection bias and balance covariates, we used propensity score matching (PSM) based on departments, age, sex, BMI, mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), anesthesia method, surgery time, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and adherence to diabetes medications (At least 6 months of regular antidiabetic medication use.). Matching was 1:1 with a caliper width of 0.2. SMD plots before and after matching were used to assess balance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparation of SMD beetween groups. Standardized mean difference (SMD): Less than 0.1 indicates negligible differences between groups

Outcomes

We performed statistical analyses on the glucose values of all five imputed datasets, and the results from each dataset showed consistency. We randomly selected one of the five datasets to present the postoperative glucose results.

Primary outcomes: After PSM, the POCL group demonstrated significantly lower blood glucose levels on the first postoperative day compared to the fasting group (11.03 [9.43–12.77] vs. 11.37 [9.77–13.20], P = 0.045) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of postoperative blood glucose levels and glycemic variability (GV) between groups (values represent daily means of three postprandial measurements)

| Before PSM | P | After PSM | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCL Group (212) | Fasting Group (467) | POCL Group (205) | Fasting Group (205) | |||

| Pos−1 d | 11.05 [9.43–12.81] | 11.37 [9.73–13.17] | 0.066 | 11.03 [9.43–12.77] | 11.37 [9.77–13.20] | 0.045 |

| Pos−2 d | 8.15 [7.20–9.51] | 8.37 [7.13–10.15] | 0.347 | 8.13 [7.20–9.50] | 8.40 [7.13–10.13] | 0.258 |

| Pos−3 d | 7.68 [6.75–9.01] | 7.93 [6.67–9.70] | 0.312 | 7.67 [6.76–8.93] | 7.90 [6.64–9.68] | 0.209 |

| GV (%) | 20.48 [15.09–27.48] | 22.68 [16.09–29.42] | 0.182 | 20.39 [14.90–27.48] | 21.81[16.10–29.78] | 0.214 |

Note: PSM: Propensity score matching; Pos−1 d: The first postoperative day. Glycemic variability is expressed as coefficient of variation (CV%), calculated as (standard deviation/mean glucose) × 100%. All glucose values were selected from patient records at approximately one hour postprandially, three times daily

Secondary outcomes and postoperative diabetes management: There were no significant differences in the incidence of postoperative pulmonary infections or hospitalization costs, but the POCL group showed a significantly shorter length of postoperative hospital stay both before and after matching (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of secondary outcomes and postoperative diabetes management between groups

| Before PSM | P | After PSM | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCL Group (212) | Fasting Group (467) | POCL Group (205) | Fasting Group (205) | |||

| Postoperative Pneumonia (n, %) | 42 (19.81%) | 68 (14.56%) | 0.085 | 36 (17.56%) | 43 (20.98%) | 0.401 |

| Postoperative Hospital Stay (day) | 5.45 [3.00–7.80] | 6.70 [3.90–8.90] | < 0.001 | 5.10 [3.00–7.70] | 5.90 [3.80–8.50] | 0.022 |

| Hospitalization Costs (Yuan) |

19327.90 [12754.92–44717.36] |

20768.73 [14409.86–33433.51] |

0.780 |

18450.77 [12647.08–41826.94] |

18577.79 [13213.16–38643.61] |

0.494 |

| ICU Admission (n,%) | 12 (5.67%) | 34 (7.28%) | 0.436 | 11 (5.37%) | 13 (6.34%) | 0.674 |

| Preoperative insulin continued (n,%) | 17 (8.02%) | 37 (7.92%) | 0.966 | 16 (7.80%) | 17 (8.29%) | 0.856 |

| New insulin initiation (n,%) | 50 (23.58%) | 115 (24.63%) | 0.770 | 48 (23.41%) | 52 (25.37%) | 0.646 |

| Continuous insulin infusion (n,%) | 5 (2.36%) | 12 (2.57%) | 0.870 | 5 (2.44%) | 5 (2.44%) | 1.000 |

Note: Data presented as n (%). PSM: Propensity score matching; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; POCL: Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading. Preoperative insulin continued: patients who were on insulin therapy before surgery and continued insulin during postoperative period. New insulin initiation: patients who required insulin therapy postoperatively despite no previous insulin use. Continuous insulin infusion: patients requiring intravenous insulin administration for glycemic control. All postoperative insulin management decisions were made according to institutional protocol by the attending physicians based on glycemic control status. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance

Postoperative diabetes management parameters showed no statistically significant between-group differences. The frequency of continued preoperative insulin therapy, de novo insulin initiation, continuous insulin infusion requirements, and ICU admission rates remained comparable between POCL and fasting cohorts (all P > 0.05). (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

To further investigate the independent associations between various variables and the outcome variables, we conducted multivariable linear regression and binary logistic regression analyses on both the matched and unmatched samples.

Postoperative hospital stay

Postoperative hospital stay was an outcome measure that showed significant differences between the groups. Regression analysis revealed that POCL (β=-1.213, 95% CI [-1.826, 0.600], P < 0.001) and Age (β = 0.036, 95% CI [0.001–0.070], P = 0.044) was positively correlated with postoperative hospital stay. Patients with shorter surgical durations also had shorter postoperative hospital stay (β = 0.016, 95% CI [0.014, 0.018], P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Multivariate analysis results for postoperative pulmonary infections and postoperative hospital stay. MAP: Mean arterial pressure; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHD: Coronary heart disease; PCA: Patient-controlled analgesia; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Diabetes drug: At least 6 months of regular antidiabetic medication use. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance

Hospitalization costs

Hospitalization costs varied among different surgical departments, with thoracic surgeries having significantly higher costs compared to other departments. ASA classification (β = 5583.44, 95%CI [1763.65, 9403.24], P = 0.004) and surgical duration (β = 102.93, 95% CI [92.68, 113.18], P < 0.001) showed a significant positive correlation with increased hospitalization costs. POCL was associated with a reduction in hospitalization costs (β = -3417.49, 95%CI [-6358.52, -476.46], P = 0.023) (Fig. 3).

Pulmonary infections

We found a significant independent association between surgical duration and the incidence of postoperative pulmonary infections (Adjusted OR = 1.005, 95% CI [1.003–1.008], P < 0.001), indicating that each additional minute of surgery increases the risk by 0.5%. Patients who developed pulmonary infections were mainly those undergoing thoracic surgeries, with a higher incidence compared to other surgeries (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our results showed that patients in the POCL group had lower glucose levels on the first postoperative day compared to those in the Fasting group. Additionally, POCL was associated with shorter postoperative hospital stays and lower hospitalization costs, indicating its effectiveness in improving patient recovery. These findings suggest that POCL implementation does not compromise postoperative glycemic management in patients with well-controlled diabetes, thereby providing new insights into perioperative management for this specific population.

POCL is effective in reducing glucose levels on the first postoperative day and no significant differences were observed between groups at other time points, indicating that POCL does not increase the risk of early postoperative hyperglycemia or greater glucose fluctuations. This finding is consistent with the results of Wang et al. [7], who found that POCL can reduce insulin resistance in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Similarly, a study by Yadav et al. [15] indicated that patients with diabetes undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy who consumed carbohydrates preoperatively experienced improved insulin resistance postoperatively. A retrospective study by Talutis et al. [16] also noted that POCL did not increase early postoperative glucose levels in patients with diabetes. This effect may be due to carbohydrate intake stimulating insulin secretion, thereby improving glucose metabolism [3].

However, it should be noted that Lee et al. [10]found that preoperative carbohydrate intake might increase glycemic variability in patients with type 2 diabetes. This discrepancy may be related to baseline glucose control, carbohydrate dose, and timing. Most studies support preoperative carbohydrate administration to patients with diabetes with good glycemic control (HbA1c < 7.5% (58 mmol/mol)) [17, 18]. In our study, mean HbA1c levels in both groups did not exceed 7.5% (58 mmol/mol). Zhang et al. [19] caution that for patients with diabetes with poor glycemic control, preoperative nutritional interventions should be implemented more cautiously. Therefore, preoperative nutritional protocols should be individualized based on each patient’s glycemic control status [1]. An important limitation is our inability to provide detailed diabetes pharmacological profiles. Our data collection categorized treatments broadly without specifying medication classes or combinations, preventing analysis of how specific regimens (metformin, DPP-4 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, GLP-1 receptor agonists) might interact with POCL outcomes. Future studies should incorporate comprehensive medication data to determine if treatment regimen influences POCL tolerability and efficacy.

Furthermore, our multivariate analysis showed that POCL is an independent predictor of favorable perioperative glucose control, shorter postoperative hospital stay, and lower hospitalization costs. This finding underscores the potential benefits of POCL in the perioperative management of patients with diabetes. The comparable frequencies of continued insulin therapy, novel insulin initiation, and continuous insulin administration between groups further suggest that preoperative carbohydrate intake does not intensify glycemic management complexity in surgical patients with well-regulated diabetes (HbA1c < 7.5%). These observations reinforce the feasibility of incorporating carbohydrate loading into enhanced recovery frameworks for selected diabetic populations, though these outcomes may not extend to patients with suboptimal glycemic profiles. This aligns with recent literature highlighting the importance of perioperative glucose management in improving surgical outcomes [1].

The significant association between surgical duration and postoperative pulmonary infections indicates that prolonged surgery may increase this risk, especially in thoracic surgeries. While COPD showed a correlation with postoperative pulmonary infections in the pre-matching analysis, this association weakened after propensity score matching. Such results may be related to the reduction in sample size following propensity score matching, or there may indeed be no significant association between the variables. Interestingly, a recent retrospective study on postoperative pneumonia did not find a correlation with chronic pulmonary disease, which is consistent with our research outcomes [20]. Regarding hospitalization costs, the study showed that Higher ASA scores and prolonged surgical duration significantly increased costs, while POCL showed a trend toward cost reduction.

When discussing the impact of POCL on patients with diabetes, it is important to consider its effects on patient comfort and quality of life. Studies [9, 21–23] show that POCL significantly reduces thirst and hunger compared to traditional fasting, enhancing patient comfort and reducing psychological stress.

The timing and method of POCL are also important areas for further exploration. Ljungqvist et al. [24] found that consuming a carbohydrate drink 2–3 h before surgery optimizes metabolic benefits without increasing the risk of aspiration. However, this timing may need adjustment for certain surgeries or high-risk patients.

While considering POCL, it is crucial not to overlook other perioperative management strategies. Gustafsson et al. [25] emphasized the role of multimodal enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols in improving outcomes for patients with diabetes. Stenberg et al. [26] highlighted the need for comprehensive perioperative management, including optimized glycemic control, fluid management, pain control, and early mobilization. Integrating POCL with these strategies to maximize benefits for patients with diabetes is a direction for future ERAS research.

None of the enrolled patients in this study experienced significant reflux or aspiration. Current evidence suggests that patients with diabetes without known gastrointestinal complications can safely consume 200–400 ml of carbohydrates preoperatively without increasing the risk of reflux or aspiration [27–30]. Even a study of morbidly obese patients with diabetes who consumed 200 ml of carbohydrates 3 h before a procedure found no increase in gastric volume [31].

Future research directions should include prospective randomized controlled trials to further validate the effectiveness of POCL in surgical patients with diabetes [11]. Additionally, there should be investigations into the optimal doses and timing of carbohydrate intake [5], as well as personalized protocols for different types of surgeries and varying degrees of diabetes [1]. Furthermore, research is needed to examine the long-term outcomes associated with POCL [12].

In summary, our study’s results support the POCL in surgical patients with diabetes. However, the implementation of this strategy should be based on a comprehensive patient assessment and individualized risk-benefit analysis [13]. Additionally, it is important to note that POCL is just one component of perioperative management and should be combined with other strategies such as glucose monitoring, medication adjustments, and complication prevention [1, 11].

Strength and limitations

Strength of the Study: (1) This study provides valuable clinical data on POCL in patients with diabetes, a controversial area. As one of the few studies in this field, it offers new insights into perioperative management; (2) The use of propensity score matching effectively reduced selection bias and enhanced the reliability of the results; 3.The study also focused on important clinical endpoints such as hospital stay and costs, critical for evaluating patient outcomes and resource utilization; 4. Multivariate analysis explored the impact of multiple factors on outcomes, providing a more comprehensive understanding.

Limitations of the Study: First, the retrospective design precludes establishment of causality, providing only correlational information. Clinician discretion in recommending POCL versus fasting protocols preceded our research initiative, potentially introducing selection bias beyond what propensity matching could address. Patients with poor or moderate glycemic control were underrepresented—likely due to clinicians’ selective prescription of POCL to well-controlled diabetes patients (HbA1c < 7.5%). While we employed propensity score matching and carefully documented exclusion criteria, the substantial number of excluded records may affect generalizability, and our findings should primarily be applied to patients with well-controlled diabetes. Second, while statistically significant, the absolute difference in day 1 glucose levels (0.34 mmol/L) was modest, and its independent clinical significance should be interpreted cautiously. The observed glycemic advantage should be considered as part of a broader constellation of benefits rather than in isolation. Third, we cannot fully account for unmeasured confounders that might have influenced treatment allocation, particularly those related to diabetes severity, management complexity, detailed medication regimens, patient compliance, and physician decision-making processes [14].

Finally, long-term outcomes, including sustained glycemic control and quality of life improvements, were not assessed in this study.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that preoperative carbohydrate loading in patients with well-controlled diabetes (HbA1c < 7.5%) is associated with improved postoperative outcomes, including lower day-one glucose levels, shorter hospital stays, and reduced costs. These benefits should not be generalized to all diabetic populations, as patients with poor glycemic control require more cautious nutritional interventions.

Implementation should be guided by individual patient assessment and integrated within comprehensive perioperative management that includes glucose monitoring, medication adjustment, and complication prevention. Future multicenter research should focus on optimizing protocols across different surgical procedures and diabetes severity levels, particularly examining POCL safety and efficacy in patients with suboptimal glycemic control [32, 33].

Acknowledgements

We thank the hospital staff who assisted with this study and the research department for their statistical support.

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Consent for publication: No details on individuals have been reported within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- POCL

Preoperative oral carbohydrate loading

- EMRs

Electronic medical records

- AIMS

Anesthesia Information Management System (AIMS)

- BMI

Body mass index

- SMDs

Standardized mean differences

- PSM

Propensity score matching

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- PCA

Patient-controlled analgesia

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- ERAS

Enhanced recovery after surgery

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Shun Wang, Liqin DengMethodology: Shun Wang, Jie Zhang, Liqin DengInvestigation: Shun Wang, Jie Zhang, Qiaoli LiuData curation: Shun Wang, Jie Zhang, Qiaoli LiuFormal analysis: Shun Wang, Jie Zhang, Qiaoli LiuProject administration: Liqin DengResources: Liqin DengSupervision: Liqin DengVisualization: Shun WangWriting– original draft: Shun WangWriting– review & editing: Shun Wang, Jie Zhang, Qiaoli Liu, Liqin DengAll authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College approved this retrospective study (2023CYFYIRB-BA-May03) and waived the requirement for informed consent. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shun Wang, Jie Zhang and Qiaoli Liu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Crowley K, Scanaill PÓ, Hermanides J, Buggy DJ. Current practice in the perioperative management of patients with diabetes mellitus: a narrative review[J]. Br J Anaesth. 2023;131(2):242–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygern J. The metabolic effects of fasting and surgery[J]. Best practice & research. Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20(3):429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abel ED, Gloyn AL, Evans-Molina C, Joseph JJ, Misra S, Pajvani UB, Simcox J, Susztak K, Drucker DJ. Diabetes mellitus-Progress and opportunities in the evolving epidemic[J]. Cell. 2024;187(15):3789–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gul A, Andsoy I I Ozkaya B. Preoperative fasting and patients’ Discomfort[J]. Indian J Surg. 2018;80(6):549–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong E, Chen Y, Ren Y, Zhou Y, Di C, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of preoperative carbohydrate loading on recovery after elective surgery: A systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Front Nutr, 2022,9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Soop M, Nygren J, Myrenfors P, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O. Preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment attenuates immediate postoperative insulin resistance[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(4):E576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Zhuang J, Cheng J, Wang Z, Sheng J, Guo S, et al. Effect of preoperative oral carbohydrates on insulin resistance in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Langenbeck’s Archives Surg, 2024,409(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lin XQ, Chen YR, Chen X, Cai YP, Lin JX, Xu DM, et al. Impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on gastric volume in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Volume 10. World J Clin Cases; 2022. pp. 6082–90. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Cassady BA, McDonald JD, Yalawar M, Baggs GE, Maki KC. Pilot study on the impact of a carbohydrate loading drink on postprandial glycemic responses and gastric emptying in adults with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023;38(1):108–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee B, Kim SY, Cho BW, Suh S, Park KK, Choi YS. Preoperative carbohydrate drink intake increases glycemic variability in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in total joint arthroplasty: A prospective randomized Trial[J]. World J Surg. 2022;46(4):791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canelli R, Louca J, Hartman C, Bilotta F. Preoperative carbohydrate load to reduce perioperative glycemic variability and improve surgical outcomes: A scoping review[J]. Volume 14. World J Diabetes; 2023. pp. 783–94. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Noba L, Wakefield A. Are carbohydrate drinks more effective than preoperative fasting: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials[J]. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(17–18):3096–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontes JPJ, Mendes FF, Vasconcelos MM, Batista NR. Evaluation and perioperative management of patients with diabetes mellitus. A challenge for the anesthesiologist[J]. Volume 68. Braz J Anesthesiol; 2018;68(1):75-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies[J]. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav K, Prakash R, Singh GP, Gautam S, Arshad Z, Singh BP. Effect of carbohydrate loading in diabetic patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized controlled Trial[J]. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e44570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talutis SD, Lee SY, Cheng D, Rosenkranz P, Alexanian SM, McAneny D. The impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on patients with type II diabetes in an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol[J]. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge L, Wang L, Wang F. Effectiveness and safety of preoperative oral carbohydrates in enhanced recovery after surgery protocols for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic Review[J]. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson KN, Cassady BA, Hegazi RA, Wischmeyer PE. Preoperative carbohydrate loading in surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: are concerns supported by data?[J]. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;45:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Gu Y, Guo T, Li Y, Cai H. Perioperative immunonutrition for Gastrointestinal cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials[J]. Surg Oncol. 2012;21(2):e87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alrefaei MI, Ahmed RA, Al Thoubaity F. Incidence of postoperative pneumonia in various surgical subspecialties: a retrospective study[J]. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2024;86(9):5043–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackland GL, Abbott TEF, Cain D, Edwards MR, Sultan P, Karmali SN, et al. Preoperative systemic inflammation and perioperative myocardial injury: prospective observational multicentre cohort study of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery[J]. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(2):180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Gao PF, Guo X, Xu Q, Zhang YF, Wang GQ, Lin JY. Effect of low-concentration carbohydrate on patient-centered quality of recovery in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a prospective randomized trial[J]. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Liu L, Liang XQ, Li YT, Wang DX. Preoperative carbohydrate loading with individualized supplemental insulin in diabetic patients undergoing Gastrointestinal surgery: A randomized trial[J]. Int J Surg. 2022;98:106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: A Review[J]. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018[J]. World J Surg. 2019;43(3):659–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenberg E, Dos Reis Falcão LF, O'Kane M, Liem R, Pournaras DJ, Salminen P, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations: A 2021 Update[J]. World J Surg. 2022;46(4):729–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laffin MR, Li S, Brisebois R, Senior PA, Wang H. The use of a Pre-operative carbohydrate drink in patients with diabetes mellitus: A prospective, Non-inferiority, cohort Study[J]. Volume 42. World J Surg; 2018. pp. 1965–70. 7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lee S, Sohn JY, Lee HJ, Yoon S, Bahk JH, Kim BR. Effect of pre-operative carbohydrate loading on aspiration risk evaluated with ultrasonography in type 2 diabetes patients: a prospective observational pilot study[J]. Sci Rep, 2022,12(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Vishak M, Gayathri B, Chandrasekhar G, Ramani S. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of preoperative carbohydrate and Non-carbohydrate loading on gastric emptying in diabetic and Non-diabetic patients posted for elective Surgery[J]. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu N, Jin Y, Wang X, Xiang Z, Zhang L, Feng S. Safety and feasibility of oral carbohydrate consumption before Cesarean delivery on patients with gestational diabetes mellitus: A parallel, randomized controlled trial[J]. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2021;47(4):1272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pimenta GP, Dandin O, Caporossi C, Nascimento JEA. Residual gastric volume in morbidly obese diabetics after an overnight fasting or 3 hours of a carbohydrate-enriched supplement. a randomized crossover pilot study[J]. ABCD. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cirurgia Digestiva (São Paulo); 2023. p. 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Gillis C, Wischmeyer PE. Pre-operative nutrition and the elective surgical patient: why, how and what?[J]. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ljungqvist O, de Boer HD. Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of enhanced recovery after surgery: A Review[J]. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.