Abstract

Objective

We aim to investigate the association between serum osmolality and the risk of developing delirium in septic patients.

Methods

Adult septic patients meeting the Sepsis-3 definition were included. Delirium was screened according to the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) tool. Patients lacked of serum osmolality results and those with delirium prior to sepsis occurrence were excluded. The association between osmolality and delirium was visualized using both restricted cubic splines (RCS) and local weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS) methods. Logistic regression, subgroup and sensitivity analysis were performed to determine the predictive value of osmolality on delirium.

Results

A total of 17,171 septic patients were included. A U-shaped pattern was observed between serum osmolality and delirium risk (P for non-linear < 0.001). Compared with intermediate range (286–301 mmol/L), patients in the low and high osmolality groups had an increased percentage of delirium. Compared with intermediate osmolality, low and high osmolality could increase the risk of delirium by 21.6-34.5% (OR 1.216–1.345) and 18.4-53.3% (OR 1.184–1.533). All subgroups analysis supported that abnormal osmolality is an independent risk factor for delirium (OR > 1), and a more significant association was found in SOFA < 6 subgroup. In sensitivity analysis, the presence of comorbidities made no influence on this U-shaped relationship. After balancing the baseline information by propensity score matching (PSM), patients in the intermediate range still had a lower incidence of delirium.

Conclusion

There was a U-shaped association between serum osmolality and the risk of sepsis-associated delirium. Further high-quality research is needed to verify our findings.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Keywords: Sepsis, Metabolism, Serum osmolality, Delirium, Sepsis-associated encephalopathy, Brain

Background

Sepsis is a common clinical syndrome caused by infection and characterized by fatal organ dysfunction and failure resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection, with extremely high morbidity and mortality [1]. Delirium, one of the major clinical manifestations of sepsis-associated brain disease, is common in both elderly and septic patients [2]. Recently, a meta-analysis including 51 studies and 39,076 patients indicated that the overall incidence and prevalence of delirium in adult patients in intensive care units (ICUs) department can be as high as 31 per 1000 and 33% [3]. In addition, delirium can affect up to 70% of patients with sepsis and is significantly associated with increased mortality and adverse outcomes, especially for elderly patients [4, 5]. Early detection and prevention of delirium are essential to improve the prognosis of septic patients, which makes the exploration of related biomarkers a hot spot in relevant research fields.

Water molecules tend to move across the semi-permeable membrane from the lower concentration side to the higher concentration side, and the resulting hydrostatic pressure is known as osmotic pressure [6]. Serum osmolality is a well-known indicator to maintain the metabolism balance in body fluid, electrolyte and renal function. Both hypertonic and hypotonic conditions, in which cells undergo osmotic swelling and shrinkage as a result of water absorption and loss, respectively, have been observed to affect normal cellular physiological functions [7]. It has been well documented that elevated osmolality levels are significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality in a range of diseases [8, 9, 10]. Among them, Liang M et al. reported a U-shaped relationship between osmolality and the risk of mortality in septic patients [11]. A study suggested serum osmolality levels at admission can effectively predict the mortality risk in patients with severe traumatic brain injury, with a sensitivity of 70.49% and a specificity of 62.86% [12]. Furthermore, the regulation of osmolality is of great importance for maintaining normal perfusion and function of brain. Given that abnormal changes in osmolality can cause brain edema, dehydration and lead to blood-brain barrier injury, it raises the question whether such changes might contribute to the development of delirium in septic patients. We hypothesized that both hyperosmolality and hypoosmolality would elevate the risk of delirium and increase mortality in patients with sepsis. To date, no studies have explored this potential relationship.

This is a retrospective analysis based on a widely used global critical care clinical database. Our objective is to elucidate the association between serum osmolality and sepsis-associated delirium. Our findings may contribute to the development of effective and convenient biomarkers for the early diagnosis of sepsis-associated delirium, as well as offering new evidence for osmolality control targets fluid and electrolyte metabolism of septic patients.

Materials and methods

Design and setting

Our retrospective research using data from a public database called the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV database (MIMIC IV, version 2.2). This is one of the most commonly used clinical databases for intensive care, comprising medical records selected years 2001 to 2010 data from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). It contains over 70,000 electronic health records of more than 50,000 patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The database is freely accessible and downloadable upon successful completion of an examination [13]. The MIMIC IV, version 2.2, used in present study, is the latest available version. Approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA, USA) and BIDMC. Regarding the issue of informed consent, the requirement for consent was waived due to the retrospective research design and without any effect on clinical decision-making. The author, Fang Yipeng, was granted access to the database and was responsible for the extraction and analysis of the data (ID: 43025968). This study was prepared in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [14]. Clinical trial number: Not applicable.

Participants

Inclusion standard: (1) Adults admitted to the ICU (aged > 18 years); (2) Only the first ICU admission record was retained for patients with multiple ICU admissions; (3) Diagnosed with sepsis during their hospitalization.

Exclusion standard: (1) Lack of serum osmolality results; (2) Being diagnosed with delirium before sepsis; (3) An ICU stay of less than 24 h, including those who died within 24 h.

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the population selection process. The final analysis included a total of 17,171 patients, with 4,523 delirium patients and 12,648 non-delirium patients.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the patient selection

Study variable

The following data were extracted: demographic information, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, urine output, vital signs, and special interventions for the patients. The diagnosis of sepsis was based on the Sepsis 3.0 criteria. In summary, patients with suspected infection and a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of at least 2 were considered to have sepsis [1]. Comorbidities were diagnosed in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was evaluated according to the creatinine standard mentioned in the KDIGO guidelines [15]. For laboratory parameters, the extreme values, either the maximum or the minimum, were used according to their clinical significance, prior to the onset of sepsis. Serum osmolality was calculated using serum sodium (mmol/L), serum potassium (mmol/L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN, mg/dL), and blood glucose (mg/dL) with the following formula: 2 × (sodium + potassium) + glucose/18 + BUN/2.8. The serum osmolality readings from the initial 24-hour period and the subsequent 24-hour period following the diagnosis of sepsis were obtained. The data pertaining to mean blood pressure (MBP) and volume status from the initial 24-hour period following the diagnosis of sepsis and the overall situation during their ICU stay were utilized. Information was gathered on any special interventions received by the patients, including the use of invasive mechanical ventilation (MV), diuretics, vasopressors and midazolam, from the time of admission to the development of sepsis.

In the case of continuous variables with a normal distribution, values that fall beyond the mean ± 3 × standard deviation (SD) range are defined as outliers. In the case of continuous variables exhibiting a non-normal distribution, values exceeding the third quartile plus one and a half times the interquartile range (IQR) or falling below the first quartile minus one and a half times the IQR were defined as outliers. We defined outliers as missing values and performed data imputation. In the case of variables with a percentage of missing values below 5%, the mean or median was employed as a means of imputing the missing values. In present study, the missing values for lactate was imputed using regression imputation, as the percentage of missing data exceeded 5%. The formula used was: Lactate = 0.713 × male − 0.410 × CKD + 0.373 × liver disease + 0.245 × SOFA − 0.001 × age + 0.004 × MBP.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was sepsis-associated delirium, defined as novel delirium that occurred after the development of sepsis during their hospitalization. Those with delirium prior to sepsis diagnosis were excluded from the final analysis. We used the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) scale to screen for sepsis-associated delirium. It is a commonly used tool with a sensitivity and specificity of 81% and 98% respectively for screening delirium [4]. The CAM-ICU screening for delirium focuses on four aspects: (1) Acute change or fluctuating course of mental status, (2) Inattention, (3) Altered level of consciousness, and (4) Disorganized thinking. When patients had both changes in mental status and inattention, further screening for level of consciousness and disorganized thinking were conducted. If either altered consciousness level or disorganized thinking present, they were considered to have delirium. Secondary outcomes included mortality, length of stay (LOS).

Statistical analysis

In this study, we showed the numbers as mean ± SD or median with IQR, depending on whether they were normally distributed. We showed the categorical data as numbers and percentages. If the data were normally distributed, we used Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA to analyze them. If the data followed with a non-normal distribution, we used the rank sum or Kruskal-Wallis for analysis. We used the Chi-square test to analyze the categorical variables. Not only the local weighted scatter plot smoothing (LOWESS), but also the restricted cubic splines (RCS) analysis methods were used to visualize how serum osmolality is linked to the risk of delirium. We got the best cut-off value and reference range for serum osmolality from the RCS curves. In addition, we used logistic regression analyses to detect the effect of serum osmolality on the risk of developing delirium. Variables were sequentially included to construct several multivariate regression models to adjust for potential confounding factors. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to check for the multicollinearity in logistic models. A VIF > 10 showed that variables were collinear. These were converted into categorical variables. Subgroup analysis was performed to detect potential interactive factors using logistic regression analysis according to age, gender, race, use of diuretics, and SOFA score. We added multiplicative interaction terms into the regression models of subgroup analysis to detect the interaction of serum osmolality and these variables. Additionally, in sensitivity analysis, RCS curves of the risk between delirium occurrence and serum osmolality in several cohorts with different comorbidities were described to explore the robustness of our findings. Finally, the propensity score matching (PSM) was performed [16], using a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching method without replacement, with a caliper value set at 0.02, to balance baseline information between the “Q2 group” (286 ≤ serum osmolality < 301) and the “Q1/Q3 group” (serum osmolality < 286 or ≥ 301). Demographic data, comorbidities, laboratory tests, MAP, special interventions, and volume balance status on the first day of sepsis diagnosis were matched.

A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (version 15.0 SE) and the R (version 4.3.2) softwares.

Result

Baseline characteristic and clinical outcomes

Delirium patients had a lower proportion of Whites (57.55% vs. 68.41%, P < 0.001, shown in Table 1). More patients in the delirium group had cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, HF, atrial fibrillation (AF), anemia, chronic pulmonary disease (CPD), AKI, chronic kidney disease (CKD), liver disease, and adrenal diseases, while fewer had coronary artery disease (CHD), hypertension (HT) and malignant cancer (all P < 0.05). Delirium patients had higher levels of white blood cells (WBC), serum creatinine and lactate, but decrease levels of serum hemoglobin and platelets (all P < 0.05). The delirium group had higher blood pressure ((76.38 ± 9.85 vs. 75.92 ± 9.79, P = 0.006)). For volume status, the degree of positive balance was more significant in delirious patients on the first day (1755 (270,3866) vs. 1153 (-200,3110), P < 0.001) and throughout the entire ICU period (405 (-248,1274) vs. 345 (-505,1396), P < 0.001). Patients with delirium had increased disease severity scores (SOFA 8 (6,11) vs. 5 (4,8); SAPSII 42 (34,52) vs. 36 (28,45)), and more patients received MV, vasopressors, and midazolam treatment (all P < 0.001). No significant difference was found in diuretic use between delirium and non-delirium groups (P = 0.427). On the first and second days after sepsis diagnosis, the delirium group had higher osmolality levels than the non-delirium group (303 (297,312) vs. 300 (295,307) on day 1; 302 (295,311) vs. 298 (292,305) on day 2, all P < 0.001). Patients with delirium had worse outcomes, higher mortality rate and LOS (all < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of the participants with and without delirium

| Variable | Overall | Non-delirium | Delirium | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 17,171 | 12,648 | 4,523 | |

| Age (years) | 66.28 ± 16.13 | 66.17 ± 16.04 | 66.58 ± 16.40 | 0.136 |

| Male (%) | 10,112(58.89) | 7,480(59.14) | 2,632(58.19) | 0.266 |

| Ethnicity, white (%) | 11,256(65.55) | 8,653(68.41) | 2,603(57.55) | < 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.72 ± 23.38 | 82.59 ± 23.03 | 83.08 ± 24.33 | 0.228 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Cerebral infarction (%) | 1,740(10.13) | 1,041(8.23) | 699(15.45) | < 0.001 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage (%) | 472(2.75) | 257(2.03) | 215(4.75) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 5,611(32.68) | 4,401(34.80) | 1,210(26.75) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 4,679(27.25) | 3,339(26.40) | 1,340(29.63) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 7,594(44.23) | 5,688(44.97) | 1,906(42.14) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 5,243(30.53) | 3,849(30.43) | 1,394(30.82) | 0.626 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 5,490(31.97) | 3,967(31.36) | 1,523(33.67) | 0.004 |

| Anemia (%) | 7,915(46.10) | 5,452(43.11) | 2,463(54.46) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (%) | 4,440(25.86) | 3,203(25.32) | 1,237(27.35) | 0.008 |

| Acute kidney injury (%) | 6,416(37.37) | 4,657(36.82) | 1,759(38.89) | 0.014 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 3,459(20.14) | 2,479(19.60) | 980(21.67) | 0.003 |

| Liver disease (%) | 2,472(14.40) | 1,651(13.05) | 821(18,15) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant cancer (%) | 2,297(13.38) | 1,736(13.73) | 561(12.40) | 0.025 |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 2,849(16.59) | 2,130(16.84) | 719(15.90) | 0.143 |

| Adrenal diseases (%) | 221(1.29) | 136(1.08) | 85(1.88) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory parameter | ||||

| White blood cell (k/uL) | 14.1(10.4,18.9) | 13.9(10.2,18.6) | 14.6(10.8,19.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.59 ± 2.03 | 9.61 ± 1.96 | 9.54 ± 2.19 | 0.044 |

| Platelets (k/uL) | 150(105,208) | 151(108,211) | 146(97,202) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1(0.8,1.7) | 1.1(0.8,1.6) | 1.2(0.9,2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.3(1.7,3.3) | 2.2(1.7,3.1) | 2.5(1.7,4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.04 ± 9.81 | 75.92 ± 9.79 | 76.38 ± 9.85 | 0.006 |

| Volume status (mL/day) | ||||

| Input 1st day | 3405(2010,5733) | 3316(1898,5646) | 3632(2317,5958) | < 0.001 |

| Input overall | 2588(1762,3715) | 2586(1701,3779) | 2659(1910,3566) | 0.004 |

| Urinary output 1st day | 2090(1275,3150) | 2195(1349,3215) | 1917(1090,2930) | < 0.001 |

| Urinary output overall | 2236(1507,3052) | 2265(1551,3087) | 2166(1358,2951) | < 0.001 |

| Volume balance 1st day | 1295(-107,3295) | 1153(-200,3110) | 1755(270,3866) | < 0.001 |

| Volume balance overall | 354(-427,1365) | 345(-505,1396) | 405(-248,1274) | < 0.001 |

| Intervention | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 7,117(41.45) | 4,649(36.76) | 2,468(54,57) | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive drug (%) | 3,922(22.84) | 2,479(19.60) | 1,443(31.90) | < 0.001 |

| Midazolam exposure (%) | 1,713 (9.98) | 1,141(9.02) | 572(12.65) | < 0.001 |

| Diuretic exposure (%) | 3,054(17.79) | 2,232(17.65) | 822(18.17) | 0.427 |

| Disease severity score | ||||

| SOFA score | 6(4,9) | 5(4,8) | 8(6,11) | < 0.001 |

| SAPSII score | 37(30,47) | 36(28,45) | 42(34,52) | < 0.001 |

| Osmolality related, day 1 | ||||

| Sodium, day 1(mmol/L) | 138.57 ± 4.60 | 138.44 ± 4.35 | 138.91 ± 5.23 | < 0.001 |

| Potassium, day 1(mmol/L) | 4.17 ± 0.62 | 4.16 ± 0.60 | 4.18 ± 0.68 | 0.018 |

| Glucose, day 1(mg/dL) | 140.26 ± 50.14 | 137.50 ± 47.56 | 147.98 ± 56.03 | < 0.001 |

| Urea nitrogen, day 1(mg/dL) | 20(14,31) | 19(13,29) | 21(15,36) | < 0.001 |

| Osmolality, day 1(mmol/L) | 301(295,308) | 300(295,307) | 303(297,312) | < 0.001 |

| Osmolality related, day 2 | ||||

| Sodium, day 2(mmol/L) | 138.14 ± 4.69 | 137.82 ± 4.45 | 139.03 ± 5.21 | < 0.001 |

| Potassium, day 2(mmol/L) | 4.07 ± 0.52 | 4.08 ± 0.51 | 4.07 ± 0.56 | 0.579 |

| Glucose, day 2(mg/dL) | 129.22 ± 39.79 | 127.42 ± 38.25 | 134.24 ± 43.44 | < 0.001 |

| Urea nitrogen, day 2(mg/dL) | 20(14,31) | 20(13,29) | 22(14,36) | < 0.001 |

| Osmolality, day 2(mmol/L) | 299(293,307) | 298(292,305) | 302(295,311) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Hospital mortality (%) | 2,077(12.10) | 1,210(9.57) | 867(19.17) | < 0.001 |

| ICU mortality (%) | 1,491(8.68) | 862(6.82) | 629(13.91) | < 0.001 |

| 28-day mortality (%) | 2,555(14.88) | 1,543(12.20) | 1,012(22.37) | < 0.001 |

| 90-day mortality (%) | 3,553(20.69) | 2,222(17.57) | 1,331(29.43) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 8.8(5.6,14.9) | 7.8(5.2,12.7) | 13.0(7.9,21.5) | < 0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 3.1(1.9,6.3) | 2.6(1.6,4.6) | 6.2(3.5,11.3) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: AF, Atrial fibrillation; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CPD, Chronic pulmonary disease; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; DM, Diabetes mellitus; HB, hemoglobin; HF, Heart failure; HT, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MV, Mechanical ventilation; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score, SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; WBC, White blood cell

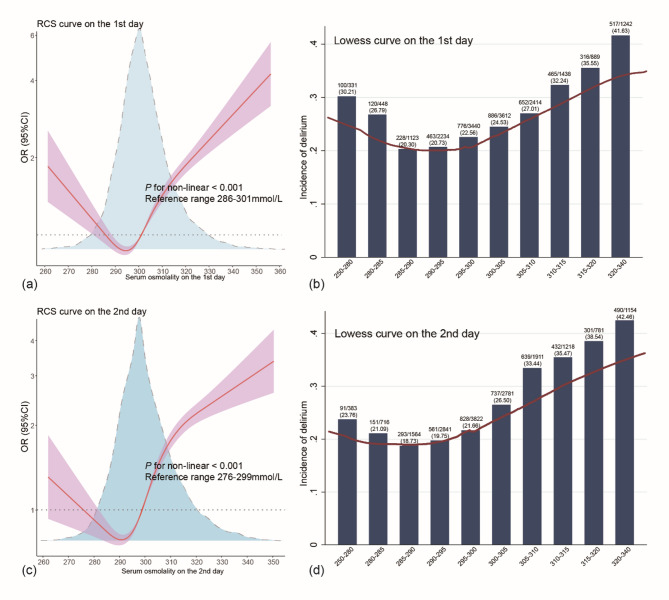

Non-linear relationship between osmolality and the risk of delirium

Figure 2 shows the RCS curves and LOWESS analysis. There was a U-shaped pattern between serum osmolality and the risk of delirium in patients with sepsis. Both low and high osmolality levels were linked to the increased risk of delirium development. Similar patterns were found on the first and second days after sepsis diagnosis. The RCS curve suggested that the optimal cut-off value was 293 mmol/L, with 286–301 mmol/L as a reference. On the base of the reference range, we further categorized patients into low osmolality (Q1, osmolality < 286mmol/L), intermediate osmolality (Q2, osmolality 286–301 mmol/L) and high osmolality (Q3, osmolality ≥ 301mmol/L) categories, using Q2 as the reference for subsequent analyses. The Q1, Q2 and Q3 categories included 919, 7,585 and 8,667 patients, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Non-linear association between osmolality and developing delirium in septic patients visualized by RCS and LOWESS curves. Day 1 and day 2 serum osmolality levels were used as the exposure in (a-b) and (c-d). (a) and (c) RCS curve. (b) and (d) LOWESS curve

Comparison of prognostic indicators among patients in different osmolality categories

The incidence rates of delirium in the three categories were 27.42%, 21.92%, and 30.09%, respectively (shown in Table 2). The incidence of delirium was significantly higher in both Q1 and Q3 categories than in the Q2 category (all P < 0.001). Significant differences were found in all mortality rate and LOS among all three categories. Compared to the Q2 category (10.49%), the 28-day mortality rate was significantly higher in both the Q1 (19.80%) and Q3 (18.20%) categories (all P < 0.001). The same was true for 90-day mortality, hospital mortality, and ICU mortality (all P < 0.001). Additionally, compared to the Q2 category, patients in the Q1 and Q3 categories had a significantly longer LOS in both hospital and ICU departments (all P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Outcomes among patients in different serum osmolality categories

| Overall | Low osmolality (Q1) | Intermediate osmolality (Q2) | High osmolality (Q3) | P1-value, P2-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 17,171 | 919 | 7,585 | 8,667 | |

| Delirium (%) | 4,523(26.34) | 252(27.42) | 1,663(21.92) | 2,608(30.09) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| 28-day mortality (%) | 2,555(14.88) | 182(19.80) | 796(10.49) | 1,577(18.20) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| 90-day mortality (%) | 3,553(20.69) | 264(28.73) | 1,163(15.33) | 2,126(24.53) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| hospital mortality (%) | 2,077(12.10) | 150(16.32) | 637(8.40) | 1,290(14.88) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| ICU mortality (%) | 1,491(8.68) | 102(11.10) | 433(5.71) | 956(11.03) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 8.8(5.6,14.9) | 9.7(6.0,16.3) | 8.2(5.3,13.8) | 9.1(5.8,15.7) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 3.1(1.9,6.3) | 3.2(1.9,6.0) | 2.8(1.6,5.2) | 3.6(2.0,7.1) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

Tip: P1-value presented the significance results between the Q1 and Q2, while P2-value was used to present the results obtained between the Q2 and Q3. P-value < 0.017(0.05/3) was considered as significant difference. Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay

Value of osmolality on developing delirium by logistic regression models

Compared to the optimal cut-off point (293 mmol/L), a 1 mmol/L increase in osmolality increased the risk of delirium by 1.5-3.0% (Odds Ratio, OR, 1.015–1.030, all P < 0.001, shown in Table 3). Meanwhile, in the low osmolality cohort, a decrease of 1 mmol/L in osmolality resulted in a 2.1-2.8% increased risk of delirium development (OR 1.021–1.028, all P < 0.001). When using patients with osmolality ranging from 286 to 301 mmol/L as a reference, osmolality < 286 mmol/L was independently associated with an increased risk of delirium occurrence, which led to a 21.6-34.5% increase in risk (OR 1.216–1.345, all P < 0.001). Osmolality ≥ 301 mmol/L also increased the risk of delirium development in patients with sepsis by 18.4-53.3% (OR 1.184–1.533, all P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Predictive value of serum osmolality on the risk of developing delirium using logistic regression analysis

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model 1 | Adjusted Model 2 | Adjusted Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | ||||||||

| Each 1mmol/L decrease (osmolality < 293) | 1.028(1.017–1.038) | < 0.001 | 1.020(1.009–1.031) | < 0.001 | 1.021(1.010–1.033) | < 0.001 | 1.024(1.013–1.036) | < 0.001 |

| Each 1mmol/L increase (osmolality > 293) | 1.030(1.026–1.033) | < 0.001 | 1.026(1.023–1.030) | < 0.001 | 1.023(1.020–1.027) | < 0.001 | 1.015(1.012–1.019) | < 0.001 |

| Categorical variables | ||||||||

| Q1(osmolality < 286) | 1.345(1.152–1.571) | < 0.001 | 1.216(1.038–1.424) | 0.015 | 1.252(1.067–1.468) | 0.006 | 1.321(1.119–1.560) | 0.001 |

| Q2(286 ≤ osmolality < 301) | Reference | |||||||

| Q3(osmolality ≥ 301) | 1.533(1.427–1.646) | < 0.001 | 1.462(1.357–1.576) | < 0.001 | 1.369(1.268–1.476) | < 0.001 | 1.184(1.094–1.283) | < 0.001 |

Model 1 adjusted for demographic information (sex, age, ethnicity, body weight), and comorbidities (cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, diabetes, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, anemia, malignant cancer, thyroid disease, adrenal diseases). Model 2 included all adjustments in Model 1 and further adjusts for MAP and laboratory parameters. Model 3 built on Model 2 by additionally adjusting for special intervention and SOFA score, SAPSII score, and volume balance on the 1st day. Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SAPSII, Simplified Acute Physiology Score-2

Subgroup analysis

Table 4 shows that serum osmolality was related to delirium risk in different subgroups. The interaction term between osmolality and SOFA score was significant (P < 0.001), while that between serum osmolality and other factors were not significant (all P > 0.05). In both young and elderly cohorts, the risk effect of abnormal osmolality still existed. Compared to patients with a SOFA score ≥ 6, the impact of changes in osmolality on the risk of delirium was more significant in those with a SOFA score < 6. Taking the Q2 category as a reference, patients with a SOFA score < 6 had a significantly higher risk of delirium for the Q1 (OR (95% CI), 1.350(1.068–1.699) vs. 1.196(0.933–1.534)) and Q3 (OR (95% CI), 1.115(1.003–1.239) vs. 1.285(1.136–1.453)) than those with a SOFA score ≥ 6. The results for all subgroups supported that abnormal osmolality changes increased the risk of delirium (all OR > 1).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis to detect the effect of different serum osmolality categories on the risk of delirium development

| Subgroups | Number | Serum osmolality(mmol/L) | P for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1(osmolality < 286) | Q2(286 ≤ osmolality < 301) | Q3(osmolality ≥ 301) | |||

| Overall | 17,171 | 1.321(1.119–1.560) | 1.00 | 1.185(1.094–1.283) | |

| Sex | 0.631 | ||||

| Male | 10,112 | 1.495(1.196–1.871) | 1.00 | 1.189(1.071–1.320) | |

| Female | 7,059 | 1.145(0.892–1.470) | 1.00 | 1.155(1.022–1.306) | |

| Age | 0.377 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 9,795 | 1.197(0.931–1.539) | 1.00 | 1.186(1.068–1.316) | |

| < 65 | 7,376 | 1.445(1.155–1.808) | 1.00 | 1.160(1.02–1.313) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.745 | ||||

| White | 11,256 | 1.478(1.201–1.820) | 1.00 | 1.190(1.076–1.317) | |

| Non-white | 5,915 | 1.074(0.816–1.414) | 1.00 | 1.157(1.017–1.316) | |

| Diuretics exposure | 0.421 | ||||

| Yes | 5,243 | 1.406(0.957–2.065) | 1.00 | 1.248(1.076–1.448) | |

| No | 11,928 | 1.294(1.076–1.557) | 1.00 | 1.167(1.062–1.282) | |

| SOFA score | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 7,601 | 1.350(1.068–1.699) | 1.00 | 1.115(1.003–1.239) | |

| No | 9,570 | 1.196(0.933–1.534) | 1.00 | 1.285(1.136–1.453) | |

Tip: Osmolality categories were determined by RCS curves of osmolality values obtained 1st day after sepsis diagnosis. Osmolality ranged from 286 mmol/L to 301 mmol/L was taken as reference. SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

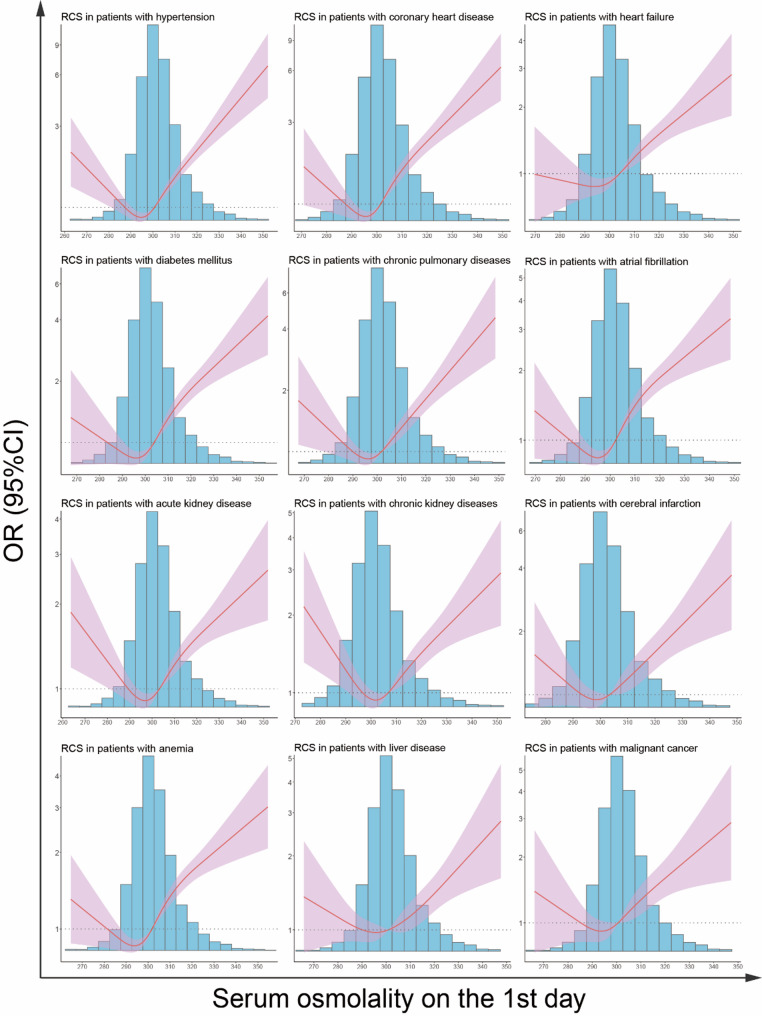

Sensitivity analysis

Further sensitivity analysis was conducted by examining different comorbidity cohorts to explore the robustness of our findings (Fig. 3). In all cohorts with different comorbidities, the U-shaped association between serum osmolality and the risk of delirium persisted (all P for non-linear < 0.001). The primary difference among the cohorts was the optimal osmolality range. Both excessively high and low serum osmolality were associated with an increased risk of delirium.

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity analysis results. The association between osmolality and the risk of delirium was further detected in nine cohorts with different comorbidities. The RCS curves were used to visualize the results

PSM matching cohort

In the PSM cohort, baseline data between the two groups were balanced (all P > 0.05, shown in Table 5), except for age and MAP. Patients in the Q2 group were younger (65.76 ± 15.98 vs. 66.33 ± 16.15, P = 0.048), while their MAP was lower (75.86 ± 9.48 vs. 76.36 ± 10.02, P = 0.004) than those in the Q1/Q3 groups. After matching the baseline characteristics, the incidence of delirium in the Q2 group remained significantly lower than that in the Q1/Q3 group (24.25% vs. 26.95%, P = 0.001). Additionally, the mortality rate in the Q2 group was also significantly decreased (all P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints for patients in PSM cohort

| Variable | Q2 group | Q1/Q3 group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 6,177 | 6,177 | |

| Age (years) | 65.76 ± 15.98 | 66.33 ± 16.15 | 0.048 |

| Male (%) | 3,619(58.59) | 3,552(57.50) | 0.222 |

| Ethnicity, white (%) | 4,082(66.08) | 4,074(65.95) | 0.879 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.30 ± 23.38 | 82.18 ± 23.01 | 0.785 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Cerebral infarction (%) | 588(9.52) | 560(9.07) | 0.386 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage (%) | 177(2.87) | 170(2.75) | 0.703 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 2,021(32.72) | 2,002(32.41) | 0.715 |

| Heart failure (%) | 1,531(24.79) | 1,491(24.14) | 0.402 |

| Hypertension (%) | 2,963(47.97) | 2,927(47.39) | 0.517 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 1,732(28.04) | 1,633(26.44) | 0.045 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 1,922(31.12) | 1,874(30.34) | 0.349 |

| Anemia (%) | 2,746(44.46) | 2,739(44.34) | 0.899 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (%) | 1,597(25.85) | 1,588(25.71) | 0.853 |

| Acute kidney injury (%) | 2,121(34.34) | 2,044(33.09) | 0.143 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 913(14.78) | 839(13.58) | 0.056 |

| Liver disease (%) | 847(13.71) | 832(13.47) | 0.694 |

| Malignant cancer (%) | 842(13.63) | 823(13.32) | 0.617 |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 1,040(16.84) | 1,031(16.69) | 0.828 |

| Adrenal diseases (%) | 68(1.10) | 64(1.04) | 0.726 |

| Laboratory parameter | |||

| White blood cell (k/uL) | 14.1(10.3,18.9) | 14.0(10.4,18.8) | 0.937 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.64 ± 1.98 | 9.68 ± 2.02 | 0.312 |

| Platelets (k/uL) | 148(107,208) | 152(106,210) | 0.484 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0(0.8,1.4) | 1.1(0.8,1.5) | 0.648 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.3(1.7,3.2) | 2.2(1.6,3.2) | 0.005 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.86 ± 9.48 | 76.36 ± 10.02 | 0.004 |

| Volume balance 1st day | 1261(-102,3261) | 1268(-125,3193) | 0.604 |

| Intervention | |||

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 2,560(41.44) | 2,538(41.09) | 0.688 |

| Vasoactive drug (%) | 1,343(21.74) | 1,311(21.22) | 0.483 |

| Midazolam exposure (%) | 568(9.20) | 545(8.82) | 0.470 |

| Diuretic exposure (%) | 1,059(17.14) | 1,050(17.00) | 0.830 |

| Disease severity score | |||

| SOFA score | 6(4,8) | 6(4,8) | 0.280 |

| SAPSII score | 37(29,45) | 36(29,45) | 0.375 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Delirium (%) | 1,498(24.25) | 1,665(26.95) | 0.001 |

| Hospital mortality (%) | 598(9.68) | 738(11.95) | < 0.001 |

| ICU mortality (%) | 413(6.69) | 543(8.79) | < 0.001 |

| 28-day mortality (%) | 746(12.08) | 921(14.91) | < 0.001 |

| 90-day mortality (%) | 1,070(17.32) | 1,284(20.79) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 8.7(5.6,14.7) | 8.4(5.4,14.6) | 0.159 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 3.0(1.8,5.8) | 3.1(1.9,6.2) | < 0.001 |

Tip: Continuous variables are displayed as mean (standard deviation) or median (first quartile–third quartile); categorical variables are displayed as count (percentage); ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score, SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. Q2 group included patients with serum osmolality ranged from 286–301 mmol/L, while Q1/Q3 group represented those with osmolality < 286 mmol/L or ≥ 301 mmol/L. PSM was performed using a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching method without replacement, with a caliper value set at 0.02

Discussion

Maintaining a proper balance of fluid and electrolyte metabolism is essential. The objective of present research is to clarify whether abnormal changes in serum osmolality are associated with an increased risk of delirium in septic patients. Our findings suggested that the relationship between osmolality and sepsis-associated delirium risk exhibited a U-shaped pattern. Both high and low osmolality were associated with an increased risk of sepsis-associated delirium. The RCS curves recommended an optimal osmolality cut-off point of 293 mmol/L, with 286–301 mmol/L as a reference. After adjusting for multiple potential confounding factors and balancing baseline information by PSM method, this association remained significant. Subgroup analysis found that our results was robust across different subgroups. Sensitivity analysis further elucidated that the presence of different comorbidities did not affect this U-shaped association. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical study to systematically describe the association between serum osmolality and the risk of delirium in septic patients. As a simple and easily obtainable biomarker related to metabolism, our study provides a potential novel biomarker for the early prediction of sepsis-associated delirium.

Serum osmolality is a measure of the solute concentration per unit mass of solvent in serum, which is influenced by levels of serum sodium, potassium, glucose, and BUN. Osmolality is crucial for maintaining cell shape and function [7]. Abnormal changes in osmolality, including hyperosmolality and hypoosmolality, are related to the increased mortality in various disease cohorts, including heart failure, diabetes mellitus, acute pulmonary embolism and sepsis [8–12]. Ziaei M’s study included 141 patients with traumatic brain injury and found that the osmolality level in the death group was significantly higher than in the survival group, with an optimal cutoff value of 298.90 mOsm/L [12]. The sensitivity and specificity for predicting death were 70.49% and 62.86%, respectively. The U-shaped association between serum osmolality and 28-day death in septic cohort, with an optimal cut-off value of 286.9 mmol/L, has been reported recently [11]. What we found in present study is consistent with previous research trends. Additionally, abnormal osmolality is closely related to an increased risk of organ dysfunction, like acute kidney injury and impaired lung function [17, 18]. Compared to osmolality levels between 285 and 300 mmol/L, osmolality < 285 mmol/L and > 300 mmol/L were associated with an increased risk of developing AKI by 33.2% (OR (95% CI), 1.332 (1.199–1.479), P < 0.001) and 19.8% (OR (95% CI), 1.198 (1.199–1.479), P < 0.001), respectively [18]. Recently, the guiding value of osmolality in encephalopathy has also received widespread attention. Eric M. Liotta et al. indicated that increased osmolality is associated with more severe hepatic encephalopathy, represented by decreasing Glasgow Coma Scale score and lower cerebro-spinal fluid specific gravity [19]. Research by Ziaei M et al. and Meng Liu et al. demonstrated the correlation between abnormal serum osmolality and the risk of mortality in patients with severe brain trauma [12] and severe acute ischemic stroke [20], respectively. Our study provides new evidence for the clinical guidance of osmolality in the field of encephalopathy. This U-shaped relationship is significantly valuable in predicting sepsis-associated delirium. Our study highlights the importance of maintaining optimal osmolality levels in clinical practice, while whether correcting abnormal osmolality could effectively reduce the incidence of delirium and mortality in patients with sepsis remains to be further explored.

The mechanisms by which elevated osmolality levels impact delirium and mortality are multifaceted. Firstly, hyperosmolality affects the distribution of solutes and water within the body, which can mediate osmotic diuresis, exacerbate dehydration, and cause electrolyte imbalance, thereby worsening hypoxia in tissues and cells [8]. Secondly, increased osmolality causes intracellular water to be shifted into the extracellular space, leading to cell shrinkage and morphological abnormalities. This, in turn, affects the function of various cellular organelles, including the nucleus and mitochondria, and ultimately disrupts cellular energy metabolism, activates the onset of apoptosis and promotes cell death [21, 22]. Thirdly, changes in osmolality affect brain perfusion and function through alterations in blood viscosity and coagulation. Increased osmolality, particularly the elevation of blood glucose, promotes coagulopathy by inhibiting fibrinolysis, creating a hypercoagulable state [23]. A significant increase in osmolality indicates a fluid-depleted state, which leads to increased blood viscosity and reduced collateral flow to the brain, increasing cerebral oxygen metabolism and impairing cerebral perfusion [20]. Fourthly, hyperosmolality can increase the levels of intracellular Ca²⁺ and reactive oxygen species, leading to endoplasmic reticulum stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis [24, 25]. Fifthly, hyperosmolality is also accompanied by the upregulation of inflammatory cytokine, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, thereby exacerbating the central nervous system inflammatory response and mediating the occurrence of delirium [26]. Sixthly, disrupting the blood-brain barrier function is an important mechanism of hyperosmolality leading to the development of encephalopathy. The impacted blood-brain barrier can lead to an increase in cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules and metabolic toxins in the central nervous system [19, 27, 28].

Hypoosmolality has been found to be significantly associated with sepsis-associated delirium in current study, but there is limited research on the underlying mechanisms. Firstly, the increase in cell swelling and associated cytocidal effects caused by the influx of extracellular water due to low osmotic pressure would ultimately lead to cell rupture and death [8]. Secondly, the presence of hyponatremia, a common cause of low osmolality, depletes the adaptive response of cell to hypoosmotic stress [29]. At the same time, the reduction of intracellular solutes in a hypoosmotic environment makes cells more susceptible to the hyperosmotic effects of increased glutamine and the subsequent influx of water into the cells [29].

Since serum osmolality is determined by the levels of serum sodium, potassium, glucose, and BUN, changes in these levels can directly lead to abnormalities in serum osmolality. Hyperosmolality is usually accompanied by hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Hong L et al. found that hypernatremia is associated with an increased risk of postoperative delirium (POD) after cardiac surgery, raising the risk of delirium by 73% [30]. The relationship between elevated blood glucose, diabetes, and the risk of delirium remains inconclusive. Van Keulen K et al. revealed a positive correlation between elevated blood glucose and the increased risk of ICU-related delirium in non-diabetic patients, emphasizing the importance of good blood glucose control for non-diabetic patients [31]. However, their research yielded a negative conclusion when exploring the association between hyperglycemia and delirium development in patients with diabetes [31]. A study from India found that the presence of diabetes is an independent risk factor of delirium for patients in cardiac ICU department [32]. There is also a paucity of studies focusing on the relationship between BUN and delirium. Mariz J et al. found that BUN and creatinine were higher in patients with delirium than in those without delirium [33]. As the presence of renal injury is widely considered to be a risk factor for the development of delirium [34], the way in which BUN affects the development of delirium, independently or through renal injury, remains unclear. A recent study reported that in populations without kidney disease or renal replacement therapy, elevated BUN has been confirmed as an independently risk factor for the occurrence of delirium, suggesting that high levels of BUN may also mediate the development of delirium through non-renal pathways [35]. Furthermore, the role of hypoglycemia and hyponatremia in the development of delirium has been widely reported. The study by Zieschang T et al. on elderly patients found that patients with hyponatremia have a higher incidence of delirium, higher in-hospital mortality rate, and may require a higher level of long-term care postoperatively compared to their pre-hospitalization status [36]. Another study by van Keulen et al. found that hypoglycemia increases the risk of delirium by 1.78-fold in diabetic patients, but not in non-diabetic patients [37]. Therefore, as a composite indicator, changes in osmolality may reflect alterations in the levels of different substances. A more comprehensive analysis of the reasons behind the abnormal changes of osmolality would provide greater clinical value.

Although this study revealed the association between osmolality and the risk of delirium, there have been no reports on using osmolality levels as targets to guide pharmacological treatment for delirium. The potential benefits of effective osmolality regulation for the prevention and treatment of delirium remain to be further explored. Mannitol and hypertonic saline are commonly used osmotic diuretics in clinical practice, which exert their dehydrating effects by increasing osmotic pressure and promoting the movement of water from cells and tissues. By increasing osmolality to induce osmotic diuresis, they are commonly used to treat cerebral edema. A few studies have investigated the effects of mannitol on delirium treatment, but their conclusions are inconsistent. Mao D et al. found that the use of mannitol is an independent risk factor for POD in children after cardiac surgery, increasing the risk of delirium by 196% [38]. However, Hamiko M et al. reported that the mannitol exposure during extracorporeal circulation is associated with a lower incidence of POD following aortic valve surgery [39]. The use of hypertonic saline has been reported to inhibit the levels of inflammatory molecules and reduce the risk of POD in elderly patients undergoing hip surgery [40]. For patients with hyponatremia, correcting hyponatremia and increasing osmolality by supplementing with sodium chloride is a standard approach. If the treatment is inadequate, life-threatening complications such as cerebral edema may occur. However, in patients with severe symptomatic hyponatremia, overcorrection of hyponatremia can lead to permanent neurological impairment due to osmotic demyelination [41]. CRRT is considered one of the effective interventions for regulating serum levels of sodium, as it can help maintain stable sodium levels without fluctuations [42]. Once clinical improvement is observed, CRRT allows for gradual and consistent withdrawal [42]. CRRT can also remove various other solutes, including BUN, which can impact osmolality. Good glycemic control is also crucial for improving the prognosis of critically ill patients and reducing complications, especially in those with stress-induced hyperglycemia [43]. Regulation of different solutes can achieve control over osmolality levels, but this may have varying impacts on the outcomes. Future research is warranted explore these potential effects further.

Serum osmolality, an easily calculated values based on laboratory parameters available at the time of hospitalization, can reflect severe organ dysfunction and solution homeostasis, including serum sodium, glucose and BUN. It holds promise as a potential new biomarker for early prediction of sepsis-associated delirium in clinical settings. While the present study offers numerous advantages and innovations, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the study and to interpret the results with caution. Firstly, as a single-center retrospective study, the presence of confounding factors may affect the accuracy of the results, although we have attempted to adjust for potential confounders using various methods. The single-center design also affects the generalizability of our results. Secondly, the retrospective manner of the study limits the ability to establish causality in present study. Mendelian randomization analysis, which has gained popularity in recent years, could elucidate the causal relationship from a genetic perspective and further eliminate the influence of confounders on our findings. Thirdly, as a variable indicator, the predictive value of dynamic observation and trend changes in osmolality is superior to that of a single time point. The future study of dynamic data changes based on trajectory models is essential, as recent advancements in trajectory analysis have provided an effective approach for this purpose [44]. Fourthly, the explanations for the potential mechanisms are based on different kinds of delirium, with only a small amount of research focusing on sepsis-associated delirium and encephalopathy. Finally, the delirium assessment tool CAM-ICU, which we used in the present study, heavily relies on the subjectivity of the assessors, which may influence our outcomes. Future research may need to incorporate objective measures for delirium assessment to improve the quality and accuracy of the study, such as electroencephalography (EEG), which has been shown to serve as an objective tool to enhance the diagnosis and prognosis of delirium [45]. Therefore, the explanations may be biased. To investigate the impact of different osmolality trajectories on the risk of delirium using trajectory models seems to be necessary. In short, future high quality, rigorously designed prospective clinical trials, Mendelian randomization studies and group-based trajectory analysis are needed to further validate the accuracy of our findings. Meanwhile, further research on the mechanisms of sepsis-associated delirium is also needed.

Conclusion

We found a U-shaped pattern between serum osmolality and the risk of delirium in patients with sepsis, in both young and elderly patients. Both excessively high and low osmolality levels were associated with a higher risk of delirium development. Osmolality has the potential to become a novel metabolic biomarker for the prediction of sepsis-associated delirium. Further research is needed to understand the causal relationship between osmolality and the risk of delirium, and whether dynamic changes of osmolality contribute to the prognosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- BIDMC

The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- CAM-ICU

The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU scale

- CI

Confident intervals

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CPD

Chronic pulmonary disease

- DM

Diabetes

- HF

Heart failure

- HT

Hypertension

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases codes

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LOS

Length of stay

- LOWESS

Local weighted scatter plot smoothing curve

- MIMIC IV

The Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV database

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

- OR

Odds ratios

- POD

Postoperative delirium

- RCS

Restricted cubic splines

- SAPSII

Simplified acute physiology score

- SD

Standard deviation

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- STROBE

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology () guidelines

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

- WBC

White blood cells

Author contributions

Yipeng Fang & Hui Xie: Writing– original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization. Aizhen Dou: Writing– review & editing. Keliang Xie & Yan Cui: Writing– review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. All authors have read and approved the final submitted version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81971879 to Keliang Xie), and the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Clinical Research Program (No.22ZYYLCCG05 to Keliang Xie), as well as the 2021-N-15 project of the China International Medical Foundation (No.2021-N-15-8 to Keliang Xie).

Data availability

Data is freely available from the MIMIC IV database (Version 2.2, accessible at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/). The raw datasets and code used in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for MIMIC IV databae was granted by the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA, USA) and BIDMC. Regarding the issue of informed consent, the requirement for consent was waived due to the retrospective research design and without any effect on clinical decision-making. Since no new data were included in the analysis, no additional ethics approval or informed consent is required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yipeng Fang and Hui Xie contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yan Cui, Email: cuiyanbio45@163.com.

Keliang Xie, Email: xiekeliang2009@hotmail.com, Email: mzk2011@126.com.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tokuda R, Nakamura K, Takatani Y et al. Sepsis-Associated delirium: A narrative review. J Clin Med. 2023. 12(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wu NN, Zhang YB, Wang SY, Zhao YH, Zhong XM. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors of delirium in ICU patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(5):653. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Q, Warren L, Saposnik G, Macdermid JC. Confusion assessment method: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1359–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widmann CN, Heneka MT. Long-term cerebral consequences of sepsis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasouli M. Basic concepts and practical equations on osmolality: biochemical approach. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(12):936–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argyropoulos C, Rondon-Berrios H, Raj DS, et al. Hypertonicity: pathophysiologic concept and experimental studies. Cureus. 2016;8(5):e596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu T, Li C, Wang T, Liu H, Geng J, Gong A. Serum osmolality was non-linearly associated with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023. 11(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaya H, Yücel O, Ege MR, et al. Plasma osmolality predicts mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Kardiol Pol. 2017;75(4):316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Öz A, Çınar T, Hayıroğlu Mİ, Avşar Ş, Keskin M, Orhan AL. The predictive value of plasma osmolality for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Clin Respir J. 2019;13(3):174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang M, Xu Y, Ren X, Huang D, Jin M, Qiu Z. The U-shaped association between serum osmolality and 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study. Infection. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ziaei M, Galavi M, Bahmani A, Abdolrazaghnejad A. The level of serum osmolarity at admission in prognosis of nosocomial mortality in patients with severe brain trauma. Adv Biomed Res. 2023;12:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z. Propensity score method: a non-parametric technique to reduce model dependence. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pogson ZE, McKeever TM, Fogarty A. The association between serum osmolality and lung function among adults. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, Cheng Y, Wang R, Wang B. Association between serum osmolality and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:745803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liotta EM, Karvellas CJ, Kim M, et al. Serum osmolality, cerebrospinal fluid specific gravity and overt hepatic encephalopathy severity in patients with liver failure. Liver Int. 2020;40(8):1977–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Deng Y, Cheng Y, Hao Z, Wu S, Liu M. Association between plasma osmolality and case fatality within 1 year after severe acute ischemic stroke. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62(7):600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dmitrieva NI, Michea LF, Rocha GM, Burg MB. Cell cycle delay and apoptosis in response to osmotic stress. Comp Biochem Physiol Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;130(3):411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinehr R, Häussinger D. Hyperosmotic activation of the CD95 death receptor system. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2006;187(1–2):199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherz N, Labarère J, Aujesky D, Méan M. Elevated admission glucose and mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgos JI, Morell M, Mariángelo J, Vila Petroff M. Hyperosmotic stress promotes Endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent apoptosis in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Apoptosis. 2019;24(9–10):785–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricardo RA, Bassani RA, Bassani JW. Osmolality- and Na+ -dependent effects of hyperosmotic NaCl solution on contractile activity and Ca2 + cycling in rat ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455(4):617–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz L, Guais A, Pooya M, Abolhassani M. Is inflammation a consequence of extracellular hyperosmolarity. J Inflamm (Lond). 2009;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burks SR, Kersch CN, Witko JA et al. Blood-brain barrier opening by intracarotid artery hyperosmolar mannitol induces sterile inflammatory and innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021. 118(18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Huang K, Zhou L, Alanis K, Hou J, Baker LA. Imaging effects of hyperosmolality on individual tricellular junctions. Chem Sci. 2020;11(5):1307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamdi T. Pathogenesis of cerebral edema in patients with acute renal and liver failure and the role of the nephrologist in the management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2018;27(4):289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong L, Shen X, Shi Q, et al. Association between hypernatremia and delirium after cardiac surgery: A nested Case-Control study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:828015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Keulen K, Knol W, Belitser SV, et al. Diabetes and glucose dysregulation and transition to delirium in ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahariya S, Grover S, Bagga S, Sharma A. Delirium in patients admitted to a cardiac intensive care unit with cardiac emergencies in a developing country: incidence, prevalence, risk factor and outcome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(2):156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mariz J, Santos NC, Afonso H, et al. Risk and clinical-outcome indicators of delirium in an emergency department intermediate care unit (EDIMCU): an observational prospective study. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutierrez RD, Smith E, Matthay ZA, et al. Risk factors and associated outcomes of postoperative delirium after open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2024;79(4):793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang Y, Tang X, Gao Y, Xie H, Shen Y, Peng M, Liu J, Zhang Y, Cui Y, Xie K. Association between blood Urea nitrogen and delirium in critically ill elderly patients without kidney diseases: A retrospective study and Mendelian randomization analysis. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2025;31(1):e70201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zieschang T, Wolf M, Vellappallil T, Uhlmann L, Oster P, Kopf D. The association of hyponatremia, risk of confusional State, and mortality. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(50):855–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Keulen K, Knol W, Belitser SV, et al. Glucose variability during delirium in diabetic and non-diabetic intensive care unit patients: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0205637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao D, Fu L, Zhang W. Risk factors and nomogram model of postoperative delirium in children with congenital heart disease: A Single-Center prospective study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2024;45(1):68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamiko M, Charitos EI, Velten M, et al. Mannitol is associated with less postoperative delirium after aortic valve surgery in patients treated with Bretschneider cardioplegia. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;70(7):549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xin X, Xin F, Chen X, et al. Hypertonic saline for prevention of delirium in geriatric patients who underwent hip surgery. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sterns RH. Treatment of severe hyponatremia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(4):641–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamdi T, Yessayan L, Yee J, Szamosfalvi B. High sodium continuous veno-venous Hemodialysis with regional citrate anticoagulation and online dialysate generation in patients with acute liver failure and cerebral edema. Hemodial Int. 2018;22(2):184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fahy BG, Sheehy AM, Coursin DB. Glucose control in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(5):1769–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagin DS, Jones BL, Elmer J. Recent advances in Group-Based trajectory modeling for clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2024;20(1):285–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohamad Faizal NS, Tan JK, Tan MM, Khoo CS, Sahibulddin SZ, Zolkafli N, Hod R, Tan HJ. Electroencephalography as a tool for assessing delirium in hospitalized patients: A single-center tertiary hospital experience. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2024;16:11795735241274203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is freely available from the MIMIC IV database (Version 2.2, accessible at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/). The raw datasets and code used in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.