Abstract

Background

In efforts to advance universal healthcare coverage (UHC) in Nigeria, the federal government empowered sub-national entities such as states to develop and implement their respective state-supported health insurance schemes (SSHIS). This study assessed the coverage and predictors of enrollment in the SSHIS in six Nigerian states.

Methods

This study used a quantitative cross-sectional design. Respondents were recruited across six Nigerian states with operational SSHIS, corresponding to the country’s six geopolitical zones. These include the Cross River, Enugu, Oyo, Kwara, Sokoto, and Taraba states, representing the South-South, South-East, South-West, North-Central, North-West, and North-East zones respectively. Data were collected from community members in congregate settings such as markets, churches/mosques, schools, bus stations/parks, and healthcare facilities. Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.

Results

The number of study respondents was 3732. The greater majority of the respondents were self-employed 1855 (49.7%) and were living with an average monthly income of < 10,000 naira 1175 (31.5%). Coverage of the state health insurance was highest in the North-Central Kwara State 326 (37.3%), but lowest in the South-Eastern Enugu State 6 (1%). Among beneficiaries, overall satisfaction with the scheme was highest in Oyo State 73 (77.7%), but lowest in Cross River State 16 (32.7%). After adjusting for confounders, several covariates were identified as decreasing the odds of enrolling into the schemes; however, lack of awareness about the scheme was most significant across all the six states.

Conclusion

Low coverage due to poor awareness, financial barriers, and enrollee dissatisfaction currently affect the SSHIS in Nigeria. To improve enrollment and sustainability, nationwide educational campaigns and consolidation of health insurance schemes are recommended.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23329-4.

Keywords: Health insurance; Out-of-pocket; SSHIS; States; UHC, Nigeria

Background

In recent decades, several low and middle-income countries have prioritized access to quality healthcare for their people towards achieving universal health coverage (UHC). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), UHC means that all people have access to the full range of quality health services that they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship [1]. An important aspect of UHC is financial risk protection, which encompasses minimizing out-of-pocket (OOP) payment for health services to prevent catastrophic or impoverishing outcomes for the consumers [2]. UHC aims to remove the financial barriers that prevent people from accessing healthcare through various insurance strategies [3]. Social health insurance, a financial risk protection strategy, has been shown in several studies to be an important factor in advancing UHC [4–6].

In Nigeria, however, the reality of health insurance coverage still leaves much to be desired. More than 90% of the 43 million households in Nigeria rely on OOP payments for their healthcare, making OOP payments a primary means of health financing in the country [7].Nigeria records one of the highest out-of-pocket (OOP) healthcare expenditures both in Africa and globally, accounting for 76% of its total healthcare expenditure in 2022 [8, 9]. This figure far exceeds the average OOP expenditure in Sub-Saharan Africa (32% in 2022) and the global average (17.23% in 2022) [10]. Despite some gains, Nigeria’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) index remained low at 38 in 2021, compared to the African average of 44 and the global average of 68, highlighting ongoing gaps in service coverage and financial protection [11]. According to the World Bank, increased OOP healthcare expenditure correlates directly with increased rates of extreme poverty, as health expenditure pushes over 1 million Nigerians into poverty, and a quarter of the population into financial strain, every year [10]. As of 2024, nearly 700 million people—8.5% of the global population—live in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $2.15 per day. Sub-Saharan Africa, with 16% of the world’s population, accounts for 67% of those living in extreme poverty [12]. Notably, Nigeria alone is home to over 100 million of these individuals, meaning roughly one in seven extremely poor people globally reside in Nigeria. This underscores the urgent need for financial protection to prevent further impoverishment from healthcare expenses [13].

Nigeria’s low UHC index score and high poverty burden together threaten the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), as limited financial risk protection heightens the risk of healthcare-related impoverishment, deepening poverty levels and undermining efforts to ensure healthy lives and well-being for all by 2030 [13–15].

The Federal Government of Nigeria, in 2005, established the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)- now National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) - in pursuit of UHC goals in the country [16]. However, by 2024, less than 10% of Nigerians have enrolled in the scheme, with most beneficiaries being a fraction in the federal workforce, leaving the majority of the population uninsured [16, 17]. Although less than 10% of Nigerians are currently enrolled in the NHIA scheme, coverage is not uniformly distributed across regions. Notably, just 14 states—including the FCT—reported health insurance coverage rates exceeding the national average, while 22 states fell below it, with Zamfara recording the lowest rate at 0.2% [18]. Evidence suggests significant regional variation in enrollment is often influenced by cultural, religious, and socioeconomic factors [19, 20]. For instance, studies have found that individuals in northern Nigeria—where traditional and religious beliefs are more conservative—may be less likely to enroll due to distrust in formal healthcare systems or preferences for traditional medicine [21]. Additionally, cultural norms around healthcare decision-making, particularly where male heads of households exert dominant influence [22], can affect the uptake of health insurance by women and children. Religion has also been shown to influence perceptions of illness and healing [23], sometimes reducing the perceived need for formal insurance schemes. In addition, low acceptance and reluctance to pay premiums were identified as some of the factors of the scheme’s low coverage, particularly within the informal sector, which accounts for around 70% of Nigeria’s workforce [24]. Thus, the NHIA struggled with its goal of providing financial risk protection to Nigerians [25].

In 2015, to enhance coverage of both informal and formal sectors, the Nigerian government approved for all states of the federation to establish and operate their respective state-supported health insurance schemes (SSHIS), with the NHIA providing technical and financial support [26, 27]. This decentralizing reform was also intended to foster stakeholders’ sense of ownership and commitment to the health insurance system, contributing to progress towards achieving UHC in the states [28].Since its inception, about 20 states have launched their SSHIS programs to different extent [29]. However, a comprehensive assessment of the progress of the SSHIS has not been conducted [30]. Specifically, recent data is lacking on the pattern of enrollment, utility, and perception of this scheme among the target population in the operating states relative to the founding objectives. This study thus aimed to assess the coverage and predictors of enrollment in the SSHIS among its target population in the states under study. Findings from this work will assist in identifying and understanding the barriers to the implementation of these schemes, to support their optimization and improve financial risk protection in line with UHC goals.

Methods

Study design, settings and inclusion criteria

A multi-site cross-sectional survey was conducted to investigate the enrollment predictors of the SSHIS across six Nigerian states. To ensure broad geographic representation, Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones were considered. From each zone, states where the SSHIS had been officially launched and was operational as of January 2023 were identified. States where the SSHIS had not yet been launched or were inactive were excluded from selection. Among eligible states in each zone, one state was selected by convenience. The final selected states were Cross River (South-South), Enugu (South-East), Oyo (South-West), Kwara (North-Central), Sokoto (North-West), and Taraba (North-East), each representing their respective geopolitical zones. These states present diverse socioeconomic characteristics, allowing for robust data comparison (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of the six study States

| State | Geopolitical Zone | Population Size (2019) | GDP (bil. $) | GDP per capita ($) | HDI Rank (out of 37 states) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taraba | North East | 3,331,885 | 5.05 | 1,424 | 21st |

| Sokoto | North West | 5,863,187 | 7.06 | 1,215 | 33rd |

| Kwara | North Central | 3,259,613 | 3.41 | 919 | 15th |

| Oyo | South West | 7,512,855 | 9.11 | 980 | 23rd |

| Enugu | South East | 4,396,098 | 3.54 | 690 | 11th |

| Cross River | South-South | 4,175,020 | 10.08 | 2,255 | 7th |

GDP: gross domestic product

HDI: human development index

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (https://nigerianstat.gov.ng)

Sampling method and sample size calculation

A multi-stage sampling method was employed. In the first stage, two Local Government Areas (LGAs) were selected from each state using simple random sampling by balloting. In the second stage, within each selected LGA, key public congregation points — markets, religious institutions (churches/mosques), schools, bus stations/parks, and healthcare facilities — were identified as clusters. At least two clusters were randomly selected from each LGA through balloting. In the third stage, within each selected cluster, adult residents (aged 18 years and above) were recruited using simple random sampling.

The minimum sample size for this study was calculated using the formula described by Kadam and Bhalerao [31]: n = Z² ×S²/ m² Where n is the sample size; Z is z-value for a 95% confidence level (1.960); S is the population standard deviation (0.5); and m is the margin of error of 5%. The minimum sample size was determined to be 385. To account for non-responses, the sample size was increased by 10%. The minimum sample size per state was determined to be 424.

Data collection and analysis

Between August 2023 and February 2024, data were collected from adult residents in each of the six study states using a pre-developed survey tool. The survey tool was adapted from previous studies investigating users’ perspectives and experiences with the health insurance system in Nigeria [32–34]. The survey tool questions were split into two sections. The first section collected demographic and socioeconomic information of respondents while the second section collected data on awareness, enrollment history, and satisfaction (of enrollees) with the SSHIS operating in their resident states [Appendix 1]. The data were collected by trained research assistants. To enhance credibility and rigor, the developed survey tool was reviewed by two experts in prepayment schemes, especially social health insurance prior to data collection. To ensure clarity, cultural relevance, and comprehensibility, the questionnaire was piloted among 20 individuals from the target population who shared similar characteristics with the intended study participants. In recognition of the linguistic diversity within the study areas, the instrument was translated into the major local languages prevalent in the selected states. Based on feedback obtained during the pilot, revisions were made to improve the flow, phrasing, and interpretability of specific questions. Individuals who participated in the pilot testing were excluded from the main study to prevent bias in the final analysis.

The survey responses were downloaded into a Google spreadsheet and then imported into IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA.) for data analysis. Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Bivariate logistic regression was performed to estimate Crude Odds Ratios (CORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the relationship between each predictor variable and enrollment in a health insurance scheme. Subsequently, all variables, regardless of significance at the bivariate level, were included in the multivariate logistic regression model to compute Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs). This approach was adopted to control for potential confounding and to assess the independent contribution of each variable. The outcome variable was set as “Enrollment in the SSHIS” (yes/no). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in both the chi-square and regression analyses. A multicollinearity test was conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and we found no evidence of multicollinearity among the studied variables.

Ethical considerations and approval

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the National Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC/01/01/2007-04/08/2023) and the ethical committees of the respective state ministries of health [Appendix 2]. Also, written informed consent was obtained from each participant in the study [Appendix 1].

Results

Demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 3,732 respondents across the six Nigerian states were involved in this study. The distribution by state was as follows: Kwara (874), Taraba (665), Enugu (600), Cross River (550), Sokoto (545), and Oyo (498). Full data on the demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

| Characteristics | Cross River (n = 550) | Taraba (n = 665) | Oyo (n = 498) | Enugu (n = 600) | Sokoto (n = 545) | Kwara (n = 874) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | f | % | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 224 | 40.7 | 337 | 50.7 | 261 | 52.4 | 432 | 72 | 238 | 43.7 | 474 | 54.2 |

| 30–39 | 205 | 37.3 | 178 | 26.8 | 103 | 20.7 | 88 | 14.7 | 171 | 31.4 | 198 | 22.7 |

| 40–49 | 86 | 15.6 | 86 | 12.9 | 69 | 13.9 | 37 | 6.2 | 81 | 14.9 | 116 | 13.3 |

| 50–59 | 24 | 4.4 | 47 | 7.1 | 43 | 8.6 | 29 | 4.8 | 39 | 7.2 | 50 | 5.7 |

| 60 and above | 10 | 1.8 | 17 | 2.5 | 22 | 4.4 | 14 | 2.3 | 16 | 2.8 | 36 | 4.1 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 243 | 44.2 | 374 | 56.2 | 239 | 48 | 230 | 38.3 | 386 | 70.8 | 487 | 55.7 |

| Female | 306 | 55.6 | 289 | 43.5 | 259 | 52 | 370 | 61.7 | 159 | 29.2 | 387 | 44.3 |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 280 | 50.9 | 270 | 40.6 | 206 | 41.4 | 149 | 25 | 276 | 50.6 | 493 | 57.4 |

| Single | 269 | 48.9 | 388 | 58.3 | 292 | 58.6 | 451 | 75 | 269 | 49.4 | 381 | 43.6 |

| Highest educational level | ||||||||||||

| No formal education | 19 | 3.4 | 37 | 5.6 | 49 | 9.8 | 14 | 2.3 | 109 | 20 | 109 | 12.5 |

| Primary School/FSLCE | 26 | 4.7 | 38 | 5.7 | 32 | 6.4 | 16 | 2.7 | 18 | 3.3 | 133 | 15.2 |

| Secondary School/WASSCE | 181 | 32.9 | 310 | 46.6 | 152 | 30.5 | 150 | 25 | 199 | 36.5 | 361 | 41.3 |

| Tertiary education/BSC or equivalent | 274 | 49.8 | 243 | 36.5 | 210 | 42.2 | 405 | 67.5 | 196 | 36 | 267 | 30.5 |

| Higher degree | 50 | 9.1 | 37 | 5.6 | 55 | 11 | 15 | 2.5 | 23 | 4.2 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Religion | ||||||||||||

| Christianity | 438 | 79.6 | 376 | 56.5 | 326 | 65.5 | 587 | 97.8 | 66 | 12.1 | 233 | 26.7 |

| Islam | 112 | 20.4 | 289 | 43.5 | 172 | 34.5 | 5 | 0.8 | 479 | 87.9 | 641 | 73.3 |

| Other | 8 | 1.4 | ||||||||||

| Tribe | ||||||||||||

| Igbo | 237 | 43.1 | 58 | 8.7 | 90 | 18.1 | 567 | 94.5 | 31 | 5.7 | 67 | 7.7 |

| Hausa | 114 | 20.7 | 214 | 32.2 | 71 | 14.3 | 7 | 1.2 | 443 | 81.3 | 58 | 6.6 |

| Yoruba | 19 | 3.5 | 40 | 6 | 321 | 64.5 | 11 | 1.8 | 37 | 6.8 | 745 | 85.2 |

| Other | 180 | 32.7 | 353 | 53.1 | 16 | 3.1 | 15 | 2.5 | 34 | 6.2 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Self employed | 322 | 58.5 | 202 | 30.3 | 190 | 38.1 | 227 | 37.8 | 300 | 55 | 614 | 70.3 |

| Private employee | 26 | 4.7 | 57 | 8.6 | 67 | 13.5 | 60 | 10 | 25 | 4.6 | 8 | 0.9 |

| Government employee | 58 | 10.5 | 137 | 20.6 | 96 | 19.3 | 42 | 7 | 54 | 9.9 | 48 | 5.5 |

| Student | 144 | 26.2 | 269 | 40.5 | 145 | 29.1 | 271 | 45.2 | 166 | 30.5 | 204 | 23.3 |

| Average Monthly Income | ||||||||||||

| Less than 10,000 | 60 | 10.9 | 153 | 23 | 127 | 25.5 | 117 | 19.5 | 93 | 17.1 | 625 | 71.5 |

| 10-30k | 233 | 42.3 | 239 | 35.9 | 125 | 25.1 | 197 | 32.8 | 270 | 49.6 | 174 | 19.9 |

| Above 30k | 257 | 46.8 | 273 | 41.1 | 246 | 49.4 | 286 | 47.7 | 182 | 33.3 | 75 | 8.6 |

| Household size | ||||||||||||

| Greater than 5 | 188 | 34.2 | 354 | 53.2 | 93 | 18.7 | 298 | 49.7 | 167 | 30.6 | 209 | 23.9 |

| Less than or equal to 5 | 362 | 65.8 | 311 | 46.8 | 405 | 81.3 | 302 | 50.3 | 378 | 69.4 | 665 | 76.1 |

The distribution of respondents across age groups varied between states. The age distribution shows a predominant representation of younger adults aged 18–29, especially in Enugu 432 (72%) and Kwara 474 (54.2%), whereas Sokoto had a relatively lower proportion of respondents in this age group 238 (43.7%). The gender distribution varies too, with males constituting the majority in Sokoto 386 (70.8%), Kwara 487 (55.7%), and Taraba 374 (56.2%), while Enugu 370 (61.7%), Oyo 259 (52%) and Cross River 306 (55.6%) had a higher proportion of female respondents. Marital status shows a mixed pattern; most respondents in Enugu 451 (75%), Taraba 388 (58.3%), and Oyo 292 (58.6%) were single, whereas the majority in Cross River 280 (50.9%), Kwara 493 (57.4%), and Sokoto 276 (50.6%) were married.

Educational attainment varies significantly. Enugu had the highest percentage of respondents with tertiary education 405 (67.5%), while Sokoto had the highest proportion with no formal education 109 (20%). Religious affiliation shows distinct regional differences. The majority of the respondents across most states identified as Christians, Enugu: 587 (97.8%), Cross River: 438 (79.6%), Taraba: 376 (56.5%), Oyo: 326 (65.5%). Islam was the dominant religion in Sokoto 479 (87.98%) and Kwara 641 (73.3%). The ethnic distribution reveals a high representation of Igbo in Enugu 567 (94.5%), Hausa in Sokoto 443(81.3%), and Yoruba in Kwara 745 (85.2%) and Oyo 321 (64.5%). Cross River and Taraba show a diverse ethnic composition with a significant proportion of respondents classified as ‘Other.’

Self-employment was the most common occupation across most of the states; Cross River, 322 (58.5%), Sokoto, 300 (55%), Kwara, 614 (70.3%). In terms of income, a significant proportion of respondents in Kwara State 625 (71.5%) earned less than 10,000 Naira monthly, while those earning above 30,000 Naira were more prevalent in Oyo State 246 (49.4%). Household size data show that the majority of respondents in Oyo State 405 (81.3%), Kwara State 665 (76.1%), Sokoto State 378 (69.4%), and Cross River State 362 (65.8%) had households with five or fewer members, while larger households (greater than five members) were more common in Taraba State 354 (53.2%).

Awareness of the SSHIS

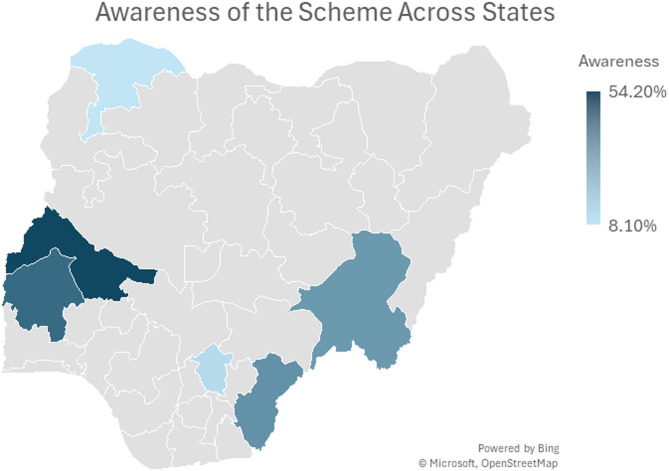

Awareness of the SSHIS varied widely among the states (Figs. 1 and 2). In Enugu, awareness was notably low, with only 67 (11.2%) of respondents being aware of the scheme. This trend was similarly observed in Sokoto, where only 44 (8.1%) were aware. In contrast, awareness was significantly higher in Kwara, where 474 (54.2%) of respondents knew about the SSHIS. In Cross River and Taraba, awareness was also relatively high, with 180 (32.7%) and 202 (30.4%) of the respondents, respectively, being aware of the scheme. Oyo had a slightly balanced distribution, with 219 (44%) awareness among its respondents.

Fig. 1.

Awareness and enrollment in the scheme across states

Fig. 2.

Awareness of the scheme across states

Sources of information about SSHIS

Among those who were aware of the SSHIS, the primary source of information varied across states (Table 3). In Oyo, the radio was the most significant source, cited by 59.4% (149) of the respondents. This was also true for Cross River, 69.8% (114), Taraba, 43.2% (99), and Sokoto, 32.4% (22). Television was another key source in Taraba, 54.1% (124), and Enugu, 24.5% (24). Seminars were less influential overall but still played a role in Taraba, 26.6%(61) and Enugu, 15.3% (15). Newspapers were the least cited source across all states, with the highest being in Taraba, 16.6% (38).

Table 3.

Awareness, coverage, satisfaction in the scheme

| Cross River | Taraba | Oyo | Enugu | Sokoto | Kwara | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of SSHIS | n = 550 | n = 665 | n = 498 | n = 600 | n = 545 | n = 874 | ||||||

| No | 370 | 67.3 | 463 | 69.6 | 279 | 56 | 533 | 88.8 | 501 | 91.9 | 400 | 45.8 |

| Yes | 180 | 32.7 | 202 | 30.4 | 219 | 44 | 67 | 11.2 | 44 | 8.1 | 474 | 54.2 |

| How did you hear of the state health insurance | n = 202 | n = 229 | n = 251 | n = 98 | n = 68 | n = 286 | ||||||

| Radio | 114 | 69.8 | 99 | 43.2 | 149 | 59.4 | 22 | 22.4 | 22 | 32.4 | 112 | 39.1 |

| Television | 90 | 44.6 | 124 | 54.1 | 76 | 30.3 | 24 | 24.5 | 9 | 13.2 | 45 | 15.6 |

| Seminar | 73 | 36.1 | 61 | 26.6 | 39 | 15.5 | 15 | 15.3 | 13 | 19.1 | 14 | 4.9 |

| Newspaper | 15 | 7.4 | 38 | 16.6 | 40 | 15.9 | 6 | 6.1 | 7 | 10.3 | 8 | 2.9 |

| Are you currently enrolled | n = 550 | n = 665 | n = 498 | n = 600 | n = 545 | n = 874 | ||||||

| Yes | 13 | 2.4 | 29 | 4.4 | 75 | 15.1 | 6 | 1 | 15 | 2.8 | 326 | 37.3 |

| No | 537 | 97.6 | 636 | 95.6 | 423 | 84.9 | 594 | 99 | 530 | 97.2 | 548 | 62.7 |

| What is your overall satisfaction with the scheme | (n = 49) | n = 69 | n = 94 | n = 37 | n = 48 | n = 728 | ||||||

| Not Satisfied | 33 | 67.3 | 15 | 21.7 | 21 | 22.3 | 22 | 59.5 | 24 | 50 | 352 | 48.4 |

| Satisfied | 16 | 32.7 | 54 | 78.3 | 73 | 77.7 | 15 | 40.5 | 24 | 50 | 376 | 51.6 |

| Reasons for enrolling in the Scheme | (n = 30) | n = 68 | n = 99 | n = 38 | n = 49 | n = 715 | ||||||

| Cheap access to care | 8 | 26.7 | 31 | 45.6 | 60 | 60.6 | 16 | 42.1 | 19 | 38.8 | 386 | 54 |

| Prevents out of pocket spending | 11 | 36.7 | 24 | 35.3 | 51 | 51.5 | 8 | 21.1 | 13 | 26.5* | 88 | 12.3 |

| To be healthy | 6 | 20 | 41 | 60.3 | 64 | 64.6 | 23 | 60.5 | 28 | 57.1 | 135 | 18.9 |

| Reasons for not enrolling in the Scheme | (n = 293) | n = 330 | n = 392 | n = 459 | n = 415 | n = 785 | ||||||

| Don’t know how the scheme works | 247 | 84.3 | 249 | 75.5 | 204 | 52 | 314 | 68.4 | 244 | 58.8 | 240 | 30.6 |

| Do not trust the scheme | 46 | 15.7 | 37 | 11.2 | 20 | 5.1 | 49 | 10.7 | 36 | 8.7 | 86 | 11 |

| Cannot afford premium | 17 | 5.8 | 55 | 16.7 | 148 | 37.8 | 40 | 8.7 | 82 | 19.8 | 65 | 8.3 |

Enrollment in SSHIS

Enrollment rates in the SSHIS were low across all states (Fig. 1). The highest enrollment was seen in Kwara, where 37.3% (326) of the respondents were enrolled. Other states had significantly lower enrollment rates, with Oyo at 15.1% (75), Taraba at 4.4% (29), Sokoto at 2.8% (15), Cross River at 2.4% (13), and Enugu at 1% (6).

Reasons for enrolling in SSHIS

The reasons for enrolling in the SSHIS differed across states (Table 3). In Kwara, 54% (386) of respondents cited cheap access to healthcare as the primary reason for enrollment. This was also a significant reason in Oyo, 60.6% (60). Preventing out-of-pocket spending was a notable reason in Oyo, 51.5% (51) and Cross River, 36.7% (11). Staying healthy was a top reason in Enugu, 60.5% (23), Sokoto, 57.1% (28), and Oyo, 64.6%(64).

Reasons for not enrolling in SSHIS

The primary reasons for not enrolling in the SSHIS included a lack of understanding of how the scheme works and distrust of the scheme (Table 3). A significant portion of respondents in Cross River, 84.3% (247), Taraba, 75.5% (249), Enugu, 68.4% (314), Sokoto, 58.8% (244), and Oyo, 52% (204) did not enroll because they did not know how the scheme works. Distrust in the scheme was a common reason in Cross River, 15.7% (46), Taraba, 11.2% (37), and Sokoto, 8.7% (36). Additionally, the inability to afford the premium was a major barrier in Oyo, 37.8% (148) and Taraba, 16.7% (55).

Overall satisfaction with the scheme

Among those enrolled in the SSHIS, overall satisfaction varied (Fig. 1). Taraba and Oyo had a high satisfaction rate of 78.3% (54) and 77.7% (73) respectively. Conversely, satisfaction was much lower in Enugu, where only 40.5% (15) were satisfied. Cross River had the lowest satisfaction rate, with only 32.7% (16) satisfied and a significant portion 67.3% (33) unsatisfied.

Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis of Factors Affecting Enrollment in the Scheme

Table 4 presents the crude and adjusted odds ratios for the association between respondent characteristics and enrollment in the health insurance scheme.

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of factors affecting enrollment into the SSHIS

| Characteristics | Cross River (n = 550) | Taraba (n = 665) | Oyo (n = 498) | Enugu (n = 600) | Sokoto (n = 545) | Kwara (n = 874) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR (CI) | aOR (CI) | cOR (CI) | aOR (CI) | cOR (CI) | aOR (CI) | cOR (CI) | aOR (CI) | OR (CI) | AOR (CI) | OR (CI) | AOR (CI) | |

| Age (RC = 30 and above) | ||||||||||||

| Less than 30 | 0.908 (0.293–2.811) | 3.879 (0.428–35.131) | 0.499 (0.228–1.090) | 1.049 (0.224–4.905) | 0.093* (0.045–0.191) | 0.318* (0.115–0.881) | 0.499 (0.228–1.090) | 1.550 (0.038–62.889) | 19.125* (2.497-146.505) | 16.303* (1.248–213.010) | 2.161* (1.627–2.871) | 0.391* (0.248–0.617) |

| Occupation (RC = Government employed) | ||||||||||||

| Student | 0.282 (0.050–1.572) | 0.167 (0.014–1.996) | 0.32* (0.135–0.757) | 1.489 (0.242–9.142) | 0.022* (0.005–0.092) | 0.076* (0.016–0.376) | 1.517 (0.168–13.731) | 2.528 (0.096–66.569) | 5.5 (0.697–43.373) | 1.630 (0.119–22.270) | 0.406* (0.214–0.768) | 0.312* (0.116–0.838) |

| Self employed | 0.444 (0.127–1.556) | 0.536 (0.122–2.353) | 0.211* (0.070–0.640) | 0.488 (0.144–1.658) | 0.079* (0.038–0.166) | 0.323* (0.135–0.770) | 0.457 (0.028–7.385) | 1.089 (0.044–26.849) | 0.791 (0.081–7.705) | 0.660 (0.049–8.959) | 0.272* (0.150–0.495) | 0.174* (0.066–0.459) |

| Education (RC = Has secondary education) | ||||||||||||

| No secondary | 0.957 (0.122–7.539) | 1.040 (0.066–16.395) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.229 (0.030–1.759) | 1.278 (0.106–15.379) | 0.454* (0.326–0.632) | 0.391* (0.248–0.617) |

| Family size (RC = Less than 5) | ||||||||||||

| Greater than 5 | 0.571 (0.155-2.100) | 0.770 (0.185–3.205) | 0.523 (0.243–1.125) | 0.635 (0.279–1.447) | 2.23* (1.282–3.881) | 1.165 (0.558–2.433) | 0.2 (0.023-1.722) | 0.258 (0.029–2.338) | 0.558 (0.155–2.004) | 0.220 (0.046–1.041) | 0.503* (0.356–0.712 | 1 (0.566–1.766) |

| Awareness (RC = Yes) | ||||||||||||

| No | 0.038 (0.005–0.294) | 0.027* (0.003–0.253) | 0.062* (0.021–0.180) | 0.087* (0.029–0.260) | 0.057* (0.026–0.128) | 0.164* (0.067–0.404) | 0.059* (0.011–0.330) | 0.070* (0.012–0.418) | 1.12 (0.247–5.078) | 0.042* (0.011–0.158) | 0.017* (0.010–0.031) | 0.014* (0.007–0.026) |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender (RC = Female) | ||||||||||||

| Male | 0.785 (0.254–2.431) | 0.793 (0.231–2.719) | 1.109 (0.521–2.360) | 0.959 (0.424–2.169) | 0.939 (0.574–1.537) | 0.652 (0.337–1.263) | 3.257 (0.592–17.924) | 2.535 (0.422–15.216) | 1.668 (0.464–5.994) | 1.439 (0.334–6.202) | 1.357* (1.030–1.787) | 1.028 (0.683–1.546) |

| Religion (RC = Islam) | ||||||||||||

| Christianity | 3.127 (0.402–24.304) | 1.184 (0.086–16.314) | 1.109 (0.521–2.360) | 0.915 (0.406–2.058) | 0.547* (0.333-0.900) | 0.538 (0.280–1.035) | 14,815,423 | 1.12 (0.247–5.078) | 0.788 (0.136–4.557) | 0.826 (0.603–1.131) | 0.679 (0.440–1.049) | |

| Marital Status (RC = Ever married) | ||||||||||||

| Single | 0.453 (0.138–1.488) | 0.157 (0.15–1.649) | 0.569 (0.269–1.204) | 1.647 (0.528–5.139) | 0.172* (0.097–0.303) | 1.072 (0.456–2.521) | 1.659 (0.192–14.316) | 1.218 (0.026–56.262) | 6.957* (1.555–31.130) | 0.895 (0.112–7.140) | 1.208 (0.917–1.592) | 0.586 (0.342–1.004) |

| Average Income (RC = Above 30k) | ||||||||||||

| 30k and less | 0.747 (0.248–2.251) | 2.618 (0.368–18.624) | 0.206* (0.087–0.490) | 0.172* (0.035–0.848) | 0.075* (0.034–0.167) | 0.376* (0.145–0.973) | 0.91 (0.182–4.545) | 0.634 (0.091–4.408) | 1.391 (0.437–4.429) | 0.652 (0.143–2.961) | 1.707* (1.003–2.904) | 7.787* (3.680-`16.481) |

The likelihood of enrolling in state health insurance varied significantly with age across the different states (Table 4). In Oyo, younger individuals (aged 18–29 years) were significantly less likely to enroll (AOR = 0.318, 95%CI: 0.115–0.881) than those aged 30 and above. Contrastingly, in Sokoto, younger individuals were more likely to enroll in the health insurance scheme (AOR = 16.303, 95%CI: 1.248–213.010). In Kwara, although younger individuals were two times more likely to enroll in the state health insurance scheme compared to those aged 30 and above (COR = 2.161, 95%CI: 1.627–2.871), this likelihood decreased after adjustment (AOR = 0.391, 95%CI: 0.248–0.617).

Occupation played a notable role in enrollment decisions (Table 4). Across states, students were generally less likely to enroll in state health insurance schemes compared to those who were government employed. In Oyo, students were significantly less likely to enroll (AOR = 0.076, 95%CI: 0.016–0.376). Similarly, in Kwara, students had lower odds of enrollment (AOR = 0.312, 95%CI: 0.116–0.838). Self-employed individuals also showed lower enrollment rates compared to their government-employed counterparts. This trend was significant in Oyo (AOR = 0.323, 95%CI: 0.135–0.770), and Kwara (AOR = 0.174, 95%CI: 0.066–0.459).

Educational attainment influenced enrollment in the health insurance scheme, particularly in Kwara. Individuals without secondary education were less likely to enroll compared to those with secondary education (AOR = 0.391, 95%CI: 0.248–0.617).

Income levels also played a significant role in determining enrollment (Table 4). In Taraba, individuals living on or below the minimum wage per month (30,000 Naira) were less likely to enroll compared to those with higher incomes (AOR = 0.172, 95%CI: 0.035–0.848). This trend was also observed in Oyo (AOR = 0.376, 95%CI: 0.145–0.973). However, in Kwara, lower-income individuals were more likely to enroll (AOR = 7.787, 95%CI: 3.680-16.481).

Awareness of the state health insurance scheme was a critical factor affecting enrollment across all states (Table 4). Individuals who were unaware of the scheme were significantly less likely to enroll compared to those who were aware in Cross River (AOR = 0.027, 95%CI: 0.003–0.253), Taraba (AOR = 0.087, 95%CI: 0.029–0.260), Oyo (AOR = 0.164, 0.067–0.404), Enugu (AOR = 0.070, 95%CI: 0.012–0.418), Sokoto (AOR = 0.042, 95%CI: 0.011–0.158), and Kwara (AOR = 0.014, 95%CI: 0.007–0.026).

Discussion

This study elucidates the predictors of enrollment, pattern of coverage, and overall satisfaction with the state-supported health insurance schemes (SSHIS) among residents in six representative states in Nigeria. Our findings appraise the contribution of SSHIS to Nigeria’s progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC)—a central component of Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) [14]. The SSHIS initiative holds some promise in bridging the equity gap left by the NHIA scheme, particularly for informal sector populations. By extending access to health services and financial protection, sustainable SSHIS also contributes to achieving SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), especially in underserved regions. Overall, we found a wide variation in the pattern of coverage of SSHIS among the studied states as indicated by the respondents’ enrollment rates ranging from 1% (Enugu State) to 37.3% (Kwara State). The inter-state differences in coverage may reflect the disparity in the implementation strategy and current progress of each state’s SSHIS, despite the commencement of the schemes around the same time.

Currently, many states operating an SSHIS struggle to enroll and retain enrollees in the schemes, as low enrollment rates in the SSHIS were recorded across all the study states. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Lagos state where only 1.5% of 2490 participants were enrolled in a state-owned health insurance scheme [17]. Four of the six states in this study (Cross River, Enugu, Sokoto and Taraba) had less than 5% enrollment rates. In Oyo state, where we found a 15% enrollment rate, a 3-year post-implementation appraisal of the state’s scheme (OYSHIA) by Adewole et al. [35] reported only 1% coverage relative to the state’s population. The authors estimated that the scheme had a 35% enrollee dropout rate in 3 years, and, at its growth rate of 18,373 people per year, could take about four centuries to achieve statewide coverage, assuming a static population [35]. According to Bolarinwa et al. [36], Kwara state, which had the highest SSHIS coverage in this study, might have leveraged the social capital built via the pre-existing Kwara State Community Health Insurance Program (KCHIP) which transitioned into the statewide Kwara State Health Insurance Programme (KSHIP) or “KwaraCare” in 2017. It was understood that beneficiaries of the KCHIP, operating prior in 11 of 16 local government areas of the state, had been reversed into OOP payments and financial strain during the KCHIP suspension and transition phase [36]. Thus, higher familiarity with a local insurance system and its benefits could explain the higher enrollment rate in the KwaraCare found in this study, as over half of our Kwara respondents were aware of the scheme.

While self-employment is the most reported form of occupational means among respondents in this study, it was associated with lower odds of enrollment, and this was also significant in both Kwara and Oyo states with relatively higher enrollment rates. This may suggest that the SSHIS faces challenges of penetrating the informal sector. Also, students (unemployed) and younger adults were largely uninsured in most of our study states, despite being half of all respondents, suggesting peculiar barriers to young adults’ coverage in the scheme. The situation seem to go against established actuarial consensus which supports that having a large number of younger enrollees with less medical needs in a health insurance scheme not only promotes better health coverage for this important subpopulation but also enhances the scheme’s sustainability through better risk pooling and cross-subsidization of older and higher-risk individuals [37, 38]. However, students’ low financial capability may be attributed to the low enrollment recorded amongst them in this study. Taken together, SSHIS currently faces coverage and informal sector penetration challenges, akin to the NHIA. In a study comparing health insurance coverage among four African countries, the Nigerian NHIA had the lowest informal sector coverage, following Ghana, Kenya, and Tanzania [39]. However, since SSHIS is relatively new, it is anticipated that, with time, a better understanding of the scheme and its benefits can enhance its success. Achieving this therefore calls for effort intensification from state SSHIS boards to overcome barriers to enrollment and ensure the SSHIS succeeds where the NHIA failed.

Our findings showed that poor awareness or inadequate understanding of how the scheme works, public distrust, and inability to afford premiums are the major barriers to enrollment in the SSHIS. Another possible barrier is the fragmentation of health insurance schemes in Nigeria [36]. However, evidence suggests that increased awareness and knowledge of the health insurance system may positively influence enrollment rates [40, 41]. This study also found SSHIS awareness to be high in the states with significant enrollment rates for example, Kwara, Oyo, and Taraba States, which could be explained as an impact of the community engagement and mobilization strategies in these states. For instance, many respondents from these states indicated they got useful information about SSHIS from radio and seminars. In agreement, a study focusing on Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) reported that people who read newspapers or magazines, listened to the radio, and watched television at least once a week had higher chances of being covered by health insurance [36]. Similar findings were reported by Adewole and colleagues among enrollees of the NHIA in Southwest Nigeria [34].

Furthermore, our findings revealed the motivations of current SSHIS enrollees to include low-cost access to care services, limited OOP expenditure, and assurance of health security. Enrollment into similar schemes has also been reported to be fueled by individuals’ desire for financial protection when they fall sick [42]. These motivations align with the purpose of the scheme and should therefore be emphasized during campaigns and promotions of the scheme. Educating potential beneficiaries about the scheme is important, especially emphasizing where packages for indigent people exist. For example, the Kwara state government has an ‘equity health plan’ through which it offers free enrollment to the poorest residents and vulnerable groups, with the commitment to offset the cost in the short term with the state’s basic primary healthcare provision fund [43].

Nevertheless, providing high-quality services to enrollees is essential for enrollee satisfaction and retention and scheme sustainability. However, our study found mixed-results with satisfaction and quality of service among current enrollees in different states. This was similar to findings in previous studies where just about half of the participants were satisfied with the quality of services rendered under the NHIA [44]. Differences in care quality dimensions such as waiting times, quality of health facilities, availability of care providers and essential medicines, and friendliness of staff, among other operational factors between each state’s SSHIS could accountfor the varied satisfaction levels found in this study [33, 34, 44]. Therefore, low enrollee satisfaction in states with low enrollment, like Enugu and Cross River states, may point to gaps in implementation or service quality for SSHIS administrators and healthcare providers to address.

Limitations of our study

Despite the relevance of our findings, we acknowledge some methodological limitations. Using convenient sampling technique, we selected one state per geopolitical zone to balance representativeness with logistical feasibility while assuming consistency in demographic characteristics across the states within each zone. While this assumption allowed for efficient sampling, intra-zone diversity may limit the generalizability of our findings. Nonetheless, we anticipate minimal cultural effects on the key outcome measures in the study—enrollment status and predictors [45]. Also, although random sampling was applied in selecting the LGAs, proportional representation across clusters was not strictly maintained, potentially introducing selection bias. Additionally, selection bias may have arisen from the exclusion of extremely remote areas or hard-to-reach populations.

Additionally, we recognize that important factors such as premium costs, distance to health facilities, type of services covered under the SSHIS, and type of facility supported were not captured in our dataset. Their omission may limit the full understanding of the factors influencing enrollment, and future research should explore these dimensions to strengthen insights into SSHIS uptake.

Conclusion

This study investigated the coverage and enrollment predictors of recently implemented SSHIS in Nigeria. Findings revealed uneven progress of the SSHIS; low coverage or enrollment rates, and currently inadequate informal sector penetration across the study states. The low enrollment was largely due to poor awareness and understanding of the schemes, financial barriers, enrollee dissatisfaction, and public distrust. Despite these challenges, some states like Kwara and Oyo recorded higher awareness, enrollment, and satisfaction levels among residents. To improve the coverage and impact of SSHIS in Nigeria, organizing nation-wide educational campaigns and community engagement meetings is recommended, targeting areas of low awareness to promote awareness, understanding and buy-in. Also, the Nigerian government should consolidate and streamline health insurance schemes in the country to enhance resource pooling and efficiency.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank our research assistants: Abdulmajid Mahmud, Baba Gazali, Chuseh Bello, Blessing Cornelius, Reuben Iliya, Abdulmajeed AGBOOLA, Abdullahi Soliu, Lateefat BABATUNDE, Maryam IBRAHEEM, Yahaya habibat, Ayomipo Mojisola, Deborah Egwuonwu, Nomeh Somtochukwu, Muoneke Amaka, Victor Okorie, Abubakar Umar, Mohammed Isah, Emmanuel Elebesunu, Aishat Hammanjoda.

Abbreviations

- OOP

Out–of–pocket

- SSHIS

State–Supported Health Insurance Schemes

- SSHISA

State–Supported Health Insurance Scheme Agency

- OYSHIA

Oyo State Health Insurance Agency

- CRISHA

Cross River State Health Insurance Agency

- ESA UHC

Enugu State Agency for Universal Health Coverage

- KSHIP

Kwara State Health Insurance Programme

- SOCHEMA

Sokoto State Contributory Healthcare Management Agency

Author contributions

FBE: Conceptualization, Data Collection, Analysis, Writing. RDD: Writing and methodology DAA: Writing. IAH: Writing. IKI: Review and critical edits DAO: Conceptualization, Review and critical edits.

Funding

Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (RSTMH).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee (NHREC/01/01/2007-04/08/2023), and ethical committees of various state ministries of health [Appendix 2]. Written informed consent was also obtained from every respondent of the study [Appendix 1]. Additionally, we conducted this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsink. A letter of introduction was written to all the KII stakeholders who participated in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.58th World Health Assembly. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage, and social health insurance. World health assembly resolution 58.33. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD. Measuring Financial Protection and Access To Services in the Uhc Agenda. 2014.

- 3.Day C, Zondi T. Measuring National health insurance: towards universal health coverage in South Africa. South Afr Health Rev. 2019;2019(1).

- 4.Chemouni B. The political path to universal health coverage: power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Dev. 2018;106:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dye C, Reeder JC, Terry RF. Research for universal health coverage. Sci Transl Med. 2013; 5:199ed13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006971 PMID: 23966297. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, Muga R, Otoo N. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Lancet. 2012; 380 (9845):933–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61147-7 PMID: 22959390. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Adesina AD, Ogaji DS. Out-of-Pocket payment for healthcare and implications for households: situational analysis in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state. J Community Med Prim Health Care. 2020;32(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Public financing for health in Africa: from Abuja to the SDGs. Geneva, WHO. 2016. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249527/WHO-HIS-HGF-Tech.Report-16.2-eng.pdf

- 9.Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Out-of-Pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):798–806. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.19. Published 2018 Sep 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank. World Development Indicators [Internet], Washington DC. World Bank; [cited 2025 May 2]. Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Type/TABLE/preview/on

- 11.Belay TA, De Simone ME, Parajuli DO, Olumide O, Dahal M et al. Human Capital Public Expenditure and Institutional Review - An analysis of financing and governance constraints for the delivery of basic education and primary health care in Nigeria (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099062424122052532/P1768901361c910261a816182a0804756d9

- 12.World Bank, Poverty, Prosperity. and Planet Report 2024: Pathways Out of the Polycrisis [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2024 [cited 2025 May 2]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-prosperity-and-planet

- 13.Claeson M, Griffin CC, Johnston TA et al. Poverty reduction and the health sector - the health, nutrition, and population network’s chapter in the World Bank’s poverty reduction strategy sourcebook. The World Bank. Accessed June 19, 2023. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/936521468147314026/Poverty-reduction-andthe-health-sector-the-health-nutrition-and-populationnetworks-chapter-in-the-World-Banks-poverty-reductionstrategy-sourcebook

- 14.World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage: 2023 global monitoring report. World Health Organization; 2023. Nov 7.

- 15.Note C. Sustainable development goals [Internet]. 2020 Nov.

- 16.National Health Insurance Scheme. NHIS. Accessed June 19. 2023. http://www.nhis.gov.ng/

- 17.Erinoso O, Oyapero A, Familoye O, Omosun A, Adeniran A, Kuyinu Y. Predictors of health insurance uptake among residents of Lagos, Nigeria. Nigeria Popul Med. 2023;5. 10.18332/popmed/169666.

- 18.Adekunle W, Oluwaseyi V. Analysing the Determinants of Healthcare Insurance Uptake in Nigeria. 2024.

- 19.Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Predictors of enrolment in the National health insurance scheme among women of reproductive age in Nigeria. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2018;7(11):1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adewole DA, Dairo MD, Bolarinwa OA. Awareness and coverage of the National health insurance scheme among formal sector workers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Afr J Biomedical Res. 2016;19(1):1–0. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Experience of Health Shocks. and Uptake of health insurance in rural and urban communities, North Central Nigeria: A Qualitative Study.

- 22.Nyande FK, Ricks E, Williams M, Jardien-Baboo S. Socio-cultural barriers to the delivery and utilisation of child healthcare services in rural Ghana: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rumun AJ. Influence of religious beliefs on healthcare practice. Int J Educ Res. 2014;2(4):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okebukola PO, Brieger WR. Providing universal health insurance coverage in Nigeria. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2016;36(4):241–6. 10.1177/0272684X16657451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alawode GO, Adewole DA. Assessment of the design and implementation challenges of the National health insurance scheme in Nigeria: a qualitative study among sub-national level actors, healthcare and insurance providers. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):124. 10.1186/s12889-020-10133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogundeji YK, Akomolafe B, Ohiri K, Butawa NN. Factors influencing willingness and ability to pay for social health insurance in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220558. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federal Government of Nigeria. National Health Act 2014. Government notice no. 208. Federal Republic of Nigeria official gazette no.145 Vol. 101. Lagos: The Federal Government Printer.

- 28.National Council on Health Nigeria. Memorandum of the honourable minister of health on the implementation of the state supported health insurance schemes. Abuja, Nigeria; 2015.

- 29.PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Nigeria. Sustainability of State Health Insurance Schemes in Nigeria: Beyond the Launch. 2019. Available. https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/assets/pdf/sustainability-state-health-insurance-nigeria.pdf Accessed: 15 July 2023.

- 30.Bolarinwa. Are There Evidence to Support the Informal Sector’s Willingness to Participate and Pay for Statewide Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria? Available: https://www.npmj.org/article.asp?issn=1117-1936;year=2021;volume=28;issue=1;spage=71;epage=73;aulasts=Bolarinwa#ref10. Accessed May 03, 2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kadam P, Bhalerao S. Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okpani AI, Abimbola S. Operationalizing universal health coverage in Nigeria through social health insurance. Niger Med J. 2015;56:305. 10.4103/0300-1652.170382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akwaowo CD, Umoh I, Motilewa O, Akpan B, Umoh E, Frank E, et al. Willingness to pay for a contributory social health insurance scheme: A survey of rural residents in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Front Public Health. 2021;9. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.654362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Adewole DA, Adeniji FIP, Adegborioye SE, Dania OM, Ilori T. Enrollees’ knowledge and satisfaction with National health insurance scheme service delivery in a tertiary hospital, Southwest Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2020;61(1):27–31. 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_126_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adewole DA, Ilori T, Ladepo W, Akande OA, Owolabi G. Pattern of population coverage of a social health insurance scheme in a Southwest Nigeria State: A 3-year post-implementation evaluation. South East Eur J Public Health 2023 Jan 24. 10.11576/seejph-4287

- 36.Bolarinwa OA, Akande TM, et al. Effects of a temporary suspension of community-based health insurance in Kwara State, North-Central, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2022;41(10). 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.10.27978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. Improving the Health, Safety, and Well-Being of Young Adults: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2013. 8. Health Care. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK202219/ [PubMed]

- 38.Collins SR. Young Adult Participation in the Health Insurance Marketplaces: Just How Important Is It? The Commonwealth Fund. [online]. Available: [https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/feb/young-adult-participation-health-insurance-marketplaces-just-how]. Accessed: 20 Sep 24.

- 39.Amu H, Dickson KS, Kumi-Kyereme A, Darteh EKM. Understanding variations in health insurance coverage in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania: evidence from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adewole DA, Adebayo AM, Osungbade KO. A qualitative survey of pre-payment scheme for healthcare services in a rural Nigerian community. Afr J Biomed Res. 2017;20:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gazmararian JA, Schwarz KS, Amacker LB, Powell CL. Barriers to prenatal care among medicaid managed care enrollees: patient and provider perceptions. HMO Pract. 1997;11:18–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pahlevan Sharif S, Naghavi N, Ong FS, Sharif Nia H, Waheed H. Health insurance satisfaction, financial burden, locus of control and quality of life of cancer patients: a moderated mediation model. Int J Soc Econ. 2021;48(4):513–30. 10.1108/ijse-10-2019-0629. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwara State Health Insurance Agency (KSHIA). Our Packages. [online]. Available: https://kwaracare.com.ng/ Accessed: 1 Oct 2024.

- 44.Mohammed S, Bermejo JL, Souares A, Sauerborn R, Dong H. Assessing responsiveness of health care services within a health insurance scheme in Nigeria: users’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sedgwick P. Convenience sampling. BMJ. 2013;347(oct25 2):f6304–6304. [Internet].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.