Highlights

-

•

Cancer-cell-derived CD38 promotes the progression and metastasis of epithelial ovarian cancer both in vitro and in vivo.

-

•

CD38 is highly expressed in the tumor microenvironment and affects cellular components and cell-to-cell interactions.

-

•

CD38 is correlated with immune responses and immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer.

-

•

CD38 inhibitors simultaneously suppress both the tumor and its microenvironment.

-

•

CD38 promotes ovarian cancer progression via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathways.

Keywords: CD38, Epithelial ovarian cancer, Tumor microenvironment, CD38 inhibito, Immunotherapy

Abstract

Background

Ovarian cancer, ranking fifth in cancer mortality, presents a significant therapeutic challenge. The immunomodulatory functions of CD38in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) and its influence on the tumor microenvironment (TME) remain poorly understood.

Methods

Public datasets, RT-qPCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were used to analyze CD38 expression and clinicopathological features in EOC. Gene manipulation techniques were employed to elucidate its functions, while integrated IHC and bioinformatics were conducted to assess its involvement in immune/stromal infiltration. Immune-related functions of CD38 were explored using GO, KEGG analysis and TIP database. TIDE algorithm was employed to predict the correlation between CD38 and immune checkpoint blocking responsiveness. CD38 inhibitor efficacy was evaluated in an EOC mouse model, with flow cytometry monitoring cellular changes. The involvement of CD38 in the PI3K-AKT and IL-6 signaling pathways was evaluated using RT-qPCR, western blot, and publicly datasets.

Results

CD38 is significantly upregulated in EOC, influencing the cell proliferation and metastasis. It regulates the PI3K-AKT and IL-6 signaling pathways, thereby increasing tumor malignancy. CD38 is also upregulated in immune and stromal cells, affecting TME remodeling by facilitating immune cell and CAF infiltration, impeding T cell recognition of tumor cells, and enhancing CAF-tumor cell communication. Additionally, CD38 correlates with multiple immune checkpoint molecules. Notably, CD38 inhibitor therapy inhibited effectively EOC progression and modulates immune responses.

Conclusion

Elevated CD38 expression is associated with EOC progression, TME remodeling, and immune response modulation. Thus, CD38 could be a promising target for ovarian cancer immunotherapy.

Graphical abstract

This image show that the critical role of CD38 in driving EOC progression and remodeling the TME. CD38 regulates the PI3K-AKT and IL-6 signaling pathways, contributing to the increased malignancy of ovarian cancer. It is notably upregulated in both immune cells and stromal cells, where it promotes their infiltration into the TME, disrupts T cell-mediated tumor recognition, and facilitates crosstalk between CAFs and tumor cells. Importantly, treatment with CD38 inhibitors has been shown to effectively curb EOC progression, diminish immune cell infiltration, and decrease the expression of the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1.

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the leading cause of death from gynecological malignancies globally [1]. Standard treatment includes debulking surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy, but the 5-year survival rate remains around 45 % due to chemotherapy resistance [2]. Identifying effective therapeutic targets is imperative. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) targeting PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, has shown remarkable success in various cancers [3], but its efficacy against EOC has been limited [4]. This discrepancy emphasizes the imperative to understand EOC-specific immune regulatory networks for developing precision therapeutic strategies.

CD38 is a 45-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein with ectoenzymatic activity, involved in the metabolism of NAD + to ADP-ribose(ADPR) and cyclic ADP-ribose(cADPR) [5]. CD38 governs extracellular adenosine homeostasis and calcium mobilization, playing pivotal roles in modulating immune cell activation, redox balance, senescence, and inflammatory responses [[6], [7], [8]]. In multiple myeloma, high expression of CD38 has made it a therapeutic target, with treatments like daratumumab showing survival benefits [9]. Similarly, in another B lymphocyte malignancy- B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), CD38 expression combined with the mutational status of the rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain V gene variable region, serves as a prognostic marker for the disease [10,11]. CD38 demonstrates complex dual immunomodulatory functions in the tumor microenvironment (TME). On one hand, it acts as a differentiation antigen that cooperates with other CD molecules to mediate lymphocyte activation [[12], [13], [14]]. Conversely, it concurrently suppresses CD8+ T cells effector functions through adenosine receptor signaling, thereby contributing to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade resistance [15]. Despite these advances in understanding CD38′s multifaceted roles in immune regulation, its specific immunological mechanisms in the TME of EOC remain poorly characterized.

The TME constitutes a highly dynamic ecosystem where intricate interactions among diverse cellular components (T cells, B cells, macrophages, fibroblasts) drive tumor progression, proliferation, and therapeutic resistance [16]. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting based molecular classification has identified four cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) subtypes in ovarian cancer, with the CAF-S1 subgroup (encompassing myCAFs and iCAFs) demonstrating prominent clinical relevance [17]. High CAF-S1 infiltration correlates significantly with poor patient prognosis. Characterized by low α-SMA expression, iCAFs predominantly localize at tumor-stromal interfaces and secrete inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 to build an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Moreover, iCAFs share JAK-STAT pathway activation mechanisms with tumor cells [18], forming a synergistic pro-tumorigenic loop. These findings emphasize the critical importance of explaining dynamic intercellular crosstalk in the TME to overcome therapeutic barriers in EOC.

In this study, we investigated CD38 expression and its potential functions in EOC using online databases, and validated our results through both in vitro and in vivo experiments. We found that CD38 is significantly overexpressed in EOC, facilitating the progression and metastasis. Importantly, CD38 is related to immune and stromal cell infiltrates and various immune checkpoints in the TME. These findings unveil the critical influence of CD38 in shaping the immune microenvironment of EOC and highlight its potential as a promising immunotherapy target against this aggressive malignancy.

Materials and methods

Tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays comprising 18 normal ovary tissue samples and 99 primary ovarian cancer specimens were obtained from ZhuoLi Biotech (Shanghai, China) for the validation of CD38 expression patterns. Antibody against CD38 (#5100, 1:200, CST, USA). IHC was carried out as in previous studies [19]. The IHC staining results of CD38 were evaluated by two pathologists, and the average values were calculated for further analysis. Cells were categorized into tumor cells (TCs), fibroblast-like cells (FLCs) and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) based on their specific shapes and locations, consistent with international guidelines and previous studies [20,21]. CD38 expression in these cell types was categorized as "positive" or "negative" accordingly.

Cell culture and reagents

The human ovarian cancer cell lines A2780 (RRID: CVCL_0134), SKOV3 (RRID: CVCL_0532), CAOV3 (RRID: CVCL_0201), Hey (RRID: CVCL_0297), HEK293 293T (RRID: CVCL_0063) were obtained from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China). C57BL/6 mouse-derived cell line ID8 and the immortalized ovarian epithelial cell line IOSE80 were conserved in our laboratory. A2780, Hey, ID8 and IOSE80 were cultured in DMEM medium (Gbico, CA, USA) with 10 % FBS. SKOV3 were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (HyClone, UT, USA) containing 10 % FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5 % CO2.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted by using a FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Reverse transcription was per formed using the HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative PCR using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The relative mRNA expression was evaluated through 2−△△Ct method. β-actin was used as an internal control. Primer sequences are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral particles for the overexpression of human and mouse CD38 genes (wt-pcDH—CD38) and for the knockdown of the human CD38 gene (PGMLV-SB3 RNAi) were synthesized by Genomeditech company (Shanghai, China), with pcDH—NC as a negative control. SKOV3, A2780, CAOV3 and ID8 cells were transduced with 5 × 10 5 transducing units/mL of lentiviral particles. Antibiotic selection with 2 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany) was initiated for ten days, 48 h after transduction. As a result, stable CD38-overexpression and knockdown cells were generated.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as in previous studies [19]. Antibodies are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Relative quantification of protein expression was conducted using Image J.

Cell viability assay, colony formation assay, wound-healing and transwell assay

These assays were performed as in previous studies [22].

Online database analysis

To perform pan-cancer CD38 expression analysis, gene expression data of 28 cancers including ovarian cancer were collected from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Program (https://portal.gdc.com). normal ovary tissues sequencing data came from GTEx database (https://gtexportal.org/home/datasets). Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE, https://depmap.org/portal/) was used to assess CD38 expression of in ovarian cancer cell lines. The GEPIA2021 database (http://gepia2021.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) was used to assess cell type level expression of CD38 in ovarian cancer [23]. The single-cell sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets were acquired from Tumor Immune Single-cell Hub (TISCH2, http://tisch.comp-genomics.org/) according to the website's guidance [24]. TISIDB platform (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php) was used to analyze CD38 expression in subtype of ovarian cancer and the correlation between CD38 and immunomodulators expression.

TME estimation

The immune, stromal and ESTIMATTE scores for TCGA-OV data and GSE9891 dataset, and tumor purity for GSE9891, were generated by the ‘ESTIMATE’ R package. Pearson correlation analysis between ESTIMATE scores and CD38 expression were counduted by Hiplot (https://hiplot.com.cn/home/index.html). GSE9891 data were divided into high and low groups based on median ESTIMATE scores to compare differences in immune, stromal, tumor purity and CD38 expression.

Identification of differentially expressed genes

TCGA-OV dataset was divided into high or low stromal/ immune groups based on the median of ESTIMATE scores. Differential gene expression (DEG) analysis was performed using the 'limma' package, comparing these two groups [25]. A false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p < 0.05, and an absolute value of fold change |FC| ≥ 1, were set as the threshold.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

TCGA-OV dataset was divided into high and low expression group based on the median expression of CD38. Immune cell infiltration in ovarian cancer was quantified using the CIBERSORT algorithm implemented in the ‘immuneeconv’ R package. R packages ‘ggplot2’ was using to draw dot plot.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA v4.3.1 was used to investigate significantly enriched genes of CD38. TCGA-OV data were divided into high and low CD38 expression groups based on the median CD38 expression. c2.cp.kegg.v7.2.symbols.gmt (curated), h.all.v7.2.symbols.gmt gene sets (Hallmarks) and c5.go.v7.2.symbols.gmt (Gene Ontology) from MSigDB were used as the reference gene sets. Each analysis involved 1000 permutations of gene sets. Normalized P value < 0.05 and FDR q value < 0.05 were established as thresholds for statistical significance. The top 15 KEGG and Hallmark pathways and top 10 GO terms were selected for visualization via dot plots or bar plots using R (4.2.1).

WGCNA of the cancer-immunity cycle scores

The R package ‘WGCNA’ was used to construct a weighted co-expression network as in previous studies [26]. The cancer-immunity cycle scores of OV samples were downloaded from the TIP database (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/TIP/index.jsp) as immune processes module phenotypes for WGCNA. The correlation between CD38 and the TIP phenotype was calculated. Excel was used to draw bar plots.

Immune checkpoint and ICB response analysis

The differential expression of some immune checkpoint genes in ovarian cancer with high and low expression of CD38 was analyzed. The TIDE algorithm was used to predict the potential response to ICB therapy in these groups.

Differential expression analysis

The GSE9891 dataset, as a validation cohort, was categorized into high and low CD38 expression groups based on the median CD38 expression. Genes related to cell communication signals and the IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathway were selected for analysis. The mRNA levels were compared between the two groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Results were visualized in box plots created with R (4.2.1).

Luminex liquid suspension chip detection

The Bio-Plex Pro Human Chemokine Panel 27-plex kit and Luminex 200 system (Wayen Biotechnologies, Shanghai, China) were utilized to assess the expression levels of 27 chemokines in mouse subcutaneous tumor tissues derived from SKOV3-Vector or SKOV3-OVE-CD38 groups.

Animal experiments

For in vivo peritoneal metastasis assays, 1.0 × 10 7 SKOV3 Vector (SKOV3-Vector) or overexpressing-CD38 (SKOV3-OVE-CD38) cells in 200μl PBS were injected into the abdominal cavity of 5-week-old female Balb/c nude mice. After 4 weeks, mice were sacrificed to evaluate peritoneal metastases.

For in vivo tumorigenesis assay, 1.0 × 10 7 ID8 Vector (ID8-Vector) or overexpressing-CD38 (ID8-OVE-CD38) cells in 150μl PBS were subcutaneously injected into right inguinal region of 5-week-old female C57BL/6 mice. After 6 weeks, mice were sacrificed and tumors were harvested. Tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: tumor volume= and tumor weights were measured.

For in vivo evaluation of CD38 inhibitor efficacy, 1.0 × 107 wild-type ID8 cells were subcutaneously injected into right inguinal region of 5-week-old female C57BL/6 mice. Four weeks post-inoculation, the CD38-specific inhibitor Compound 78c (S8906, Selleck Chemicals, TX, USA) was administered to C57BL/6 by intraperitoneal injection (10 mg/kg/dose [27]) every two days over a period of 3 weeks. Mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected to calculate volumes, weight and immune profiling through flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from ID8 subcutaneous tumor through sequential mechanical and enzymatic dissociation: tissues were initially minced and filtered through a 70-μm mesh, followed by enzymatic digestion in DMEM buffer containing 0.2 % collagenase I, 0.002 % DNase I, and 0.01 % hyaluronidase (all from Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany) for 1 hour at 37 °C. The cells were further dissociated using the gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Cologne, Germany), and pelleted by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min. For cell surface staining, cells were resuspended in 100μl FACS buffer and incubated with FVS-510 (BD, NJ, USA) at 4 °C for 30 min to discriminate viable cells. After nonspecific Fc binding blocking with CD16/CD32 Mouse BD Fc Block (BD, NJ, USA) for 15 min at 4 °C, cell surface markers were labeled with anti-Mouse CD4-FITC, CD3e-PE, CD8a-APC from BD, and CD38-FITC (Invitrogen, CA, USA) for 15 min at 4 °C respectively. Compensation was adjusted using BD CompBeads (NJ, USA), with subsequent acquisition on a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD, NJ, USA) and data analysis conducted using FlowJo software [28].

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 22.0 software was conducted for statistical analyses. Data were calculated by the χ 2 or Fisher’s exact test. The correlations were analyzed by Pearson’s test (r,P). The specific test methods, P-values, effect sizes, and confidence intervals can be found in Supplemental Table 3. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

CD38 is upregulated in ovarian cancer and associated with advanced histological grading

The pan-cancer analysis of TCGA and GTEx databases revealed significant upregulation of CD38 in various cancers, including CESC, DLBC, LGG, PAAD, STAD, TGCT (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Our study focused on ovarian cancer shows notably elevated CD38 mRNA levels in ovarian cancer tissues compared to normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Additionally, analysis of CD38 gene expression across different cell lines found that human ovarian cancer cell lines had significantly higher CD38 expression than the normal ovarian epithelial cell line (IOSE80) (Fig. 1B). This disparity was verified by Western blot analysis, which unveiled CAOV3 as exhibiting the highest CD38 expression (Fig. 1C). IHC further validated CD38 protein levels in EOC, particularly in serous and endometrioid subtypes (Fig. 1D-F). We then explored the clinical significance of CD38 expression in ovarian cancer. Our data revealed a correlation between high CD38 expression and advanced histological grades (Fig. 1G), suggesting a potential role for CD38 in ovarian cancer progression. However, there was no statistically significant correlation between CD38 expression and patient age or FIGO stage (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

CD38 is upregulated in ovarian cancer and associated with advanced histological grading

(A) RNA sequencing from the TCGA database revealed significantly higher CD38 expression in ovarian cancer tissues (n = 376) compared to normal tissues (n = 180) ****p < 0.0001).

(B) qPCR analysis showed relative CD38 mRNA levels in human ovarian cancer cell lines (IOSE80, A2780, SKOV3, HEY, and CAOV3), normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

(C) Western blot analysis showed CD38 protein expression in the indicated ovarian cancer cell lines.

(D) IHC staining for CD38 expression in normal ovarian epithelial tissues and EOC tissues. Scale bars: 250 μm (low magnification) and 50 μm (high magnification).

(E) IHC scores for CD38 expression showed a significant difference between normal (n = 18) and EOC tissues (n = 98) (****p < 0.0001).

(F) IHC scores for CD38 expression across different EOC subtypes: normal tissue (n = 18), serous cystadenocarcinoma (n = 54), mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (n = 12), and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (n = 31) (***p < 0.001).

(G) IHC scores for CD38 expression stratified by histological grades of EOC. A correlation with advanced stages is observed, with sample sizes as follows: normal (n = 18), stage I (n = 15), stage I-II (n = 8), stage II (n = 20), stage II-III (n = 11), and stage III (n = 44) (***p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Relationship between clinical pathologic characteristics and expression of CD38 in ovarian cancer tissues.

| Factors | Number of patients | CD38 expression |

χ2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||||

| Age(years) | |||||

| <50 | 35 | 10 | 25 | 2.234 | 0.1350 |

| ≥50 | 63 | 10 | 53 | ||

| Histological grade | |||||

| I-II II-III |

43 55 |

14 5 |

29 50 |

8.504 | 0.0035⁎⁎ |

| FIGO stage | |||||

| I II III IV |

42 20 8 23 |

10 6 1 3 |

32 18 7 20 |

1.195 | 0.2744 |

| T stage | |||||

| T1 T2+T3 |

44 54 |

10 10 |

34 44 |

0.2644 | 0.6071 |

| N stage | |||||

| N0 N1 |

91 7 |

18 2 |

73 5 |

0.6287 | |

| M stage | |||||

| M0 M1 |

75 23 |

17 3 |

58 20 |

0.3891 | |

Significant at the 0.01 level.

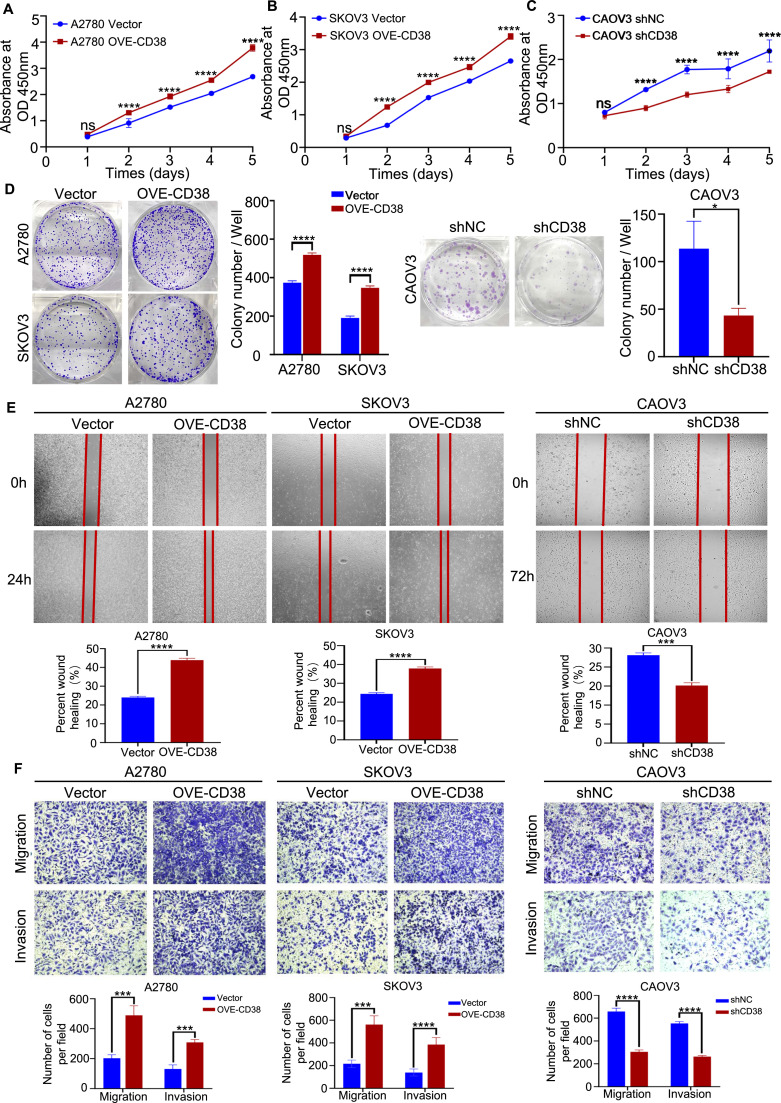

Cancer-cell-derived CD38 promotes the progress and metastasis of EOC in vitro

To explore the function of CD38 in EOC, we established stable CD38-overexpressing cell lines (CAOV3, A2780, and SKOV3) and CD38-knockdown in CAOV3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A-D). Using CCK-8 and colony formation assays, we found that CD38 overexpression significantly enhanced the proliferation of CAOV3, A2780, and SKOV3 cells, whereas CD38 silencing suppressed cell growth (Fig. 2A-D, Supplementary Fig. 2E-F). Wound-healing and transwell assays further demonstrated that CD38 overexpression markedly enhanced the migration and invasion capacities of these cells, while CD38 knockdown yielded opposite results (Fig. 2E-F, Supplementary Fig. 2G-H).

Fig. 2.

Cancer-cell-derived CD38 promotes progress and metastasis of EOC in vitro

(A-C) Cell viability of A2780 (A) and SKOV3 (B) cells stably expressing vector or CD38, and CAOV3 (C) cells stably expressing shNC or shCD38, was assessed every 24 h for 5 days using a CCK-8 assay (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Optical density (OD) values represent relative cell proliferation (n = 5 per group).

(D) Colony formation assays for A2780 and SKOV3 cells stably expressing vector or CD38, and CAOV3 cells stably expressing shNC or shCD38 (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Left, representative images. Right, quantification of colony numbers.

(E) Wound healing assays for A2780 and SKOV3 cells stably expressing vector or CD38 at 0 and 24 h post-wounding, and for CAOV3 cells stably expressing shNC or shCD38 at 0 and 72 h post-wounding (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Upper panels, representative images. Lower panels, quantification of migration distances.

(F) Transwell assay evaluated migration and invasion in A2780 and SKOV3 cells stably expressing vector or CD38, and in CAOV3 cells stably expressing shNC or shCD38 (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Upper panels, representative images. Lower panels, quantification of migrated and invaded cell numbers. Scale bars: 250 μm.

CD38 is highly expressed in tumor-infiltrating immune cells and stroma cells of ovarian cancer

To investigate the mechanisms and prognostic significance of CD38 in tumor immunity within the ovarian cancer microenvironment, we applied the ESTIMATE algorithm on TCGA-OV data to estimate the immune and stromal components proportions. Through comparative analysis of gene expression profiles between high and low immune/stromal scores, we identified 272 DEGs linked to high immune scores and 1402 DEGs associated with high stromal scores. Notably, CD38 emerged as a shared key gene in both groups (Fig. 3A-3C). Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed positive correlations between CD38 expression and both immune and stromal scores (Fig. 3D). Similar trends were observed in the GEO dataset GSE9891, where high-score groups showed increased CD38 expression (Fig. 3E). IHC revealed CD38 positivity in TCs, FLCs and TILs (Fig. 3F-G).

Fig. 3.

CD38 is highly expressed in tumor-infiltrating immune cells and stroma cells of ovarian cancer

(A-B) Volcano plots illustrated DEGs by comparing high and low score groups based on Immune Scores(A) and Stromal scores(B) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with an adjusted p-value< 0.05 and a fold-change ≥1 after log2 transformation as the significance threshold).

(C) Venn diagram illustrated the overlap of common up-regulated DEGs between Immune Scores and Stromal Scores.

(D) Pearson's correlation analysis showed the relationship between immune, stromal, ESTIMATE scores with CD38 expression levels.

(E) Comparison of CD38 expression levels between high and low groups based on immune scores, stromal scores, ESTIMATE scores, and tumor purity in the ovarian cancer dataset GSE9891 from GEO (n = 293, ****p < 0.0001).

(F) IHC staining to evaluate CD38 expression in tumor nests, TILs and FLCs. Sample sizes: n = 67 for TCs, n = 42 for TILs, n = 61 for FLCs. Scale bars: 250 μm (low magnification) and 50 μm (high magnification).

(G) Proportions of CD38 IHC staining positive and negative samples in TCs, TILs and FLCs.

Utilizing the GEPIA2021 database, we observed elevated CD38 expression in CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and macrophages in ovarian cancer microenvironment (Fig. Supplementary 1C). Through CIBERSORT analysis of the TCGA-OV dataset, samples were stratified into high and low CD38 expression groups. The result showed that high CD38 expression correlated with increased infiltration of plasma cells, CD8+ T cells, T follicular helper cells, and M1 macrophages. Conversely, low CD38 expression was associated with higher infiltration of B cells, CD4+ memory T cells, activated dendritic cells, and M0 and M2 macrophages (Fig. Supplementary 1D).

To investigate CD38 expression at the single-cell level in ovarian cancer, we analyzed six single-cell sequencing datasets from the TISCH2 database. CD38 was expressed in tumor cells, immune cells and stromal cells, particularly in CD8+T cells, plasma cells and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 4A-B, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Comparative analysis of GSE118828 data showed significantly higher CD38 expression in ovarian cancer than normal ovary tissues (Fig. 4C), with further elevation in metastatic lesions (Fig. 4D). These results reinforce our funding that malignant cell-derived CD38 drives ovarian cancer progression and metastasis.

Fig. 4.

Evaluating CD38’s impact on cell infiltration and communication in ovarian cancer by single-cell resolution

(A) Cell type annotation for six datasets categorized by major lineage. The heatmap showed the average gene expression of CD38 in different populations of malignant, immune and stromal cells.

(B) UMAP dimensionality reduction of cellular landscape of ovarian cancer and CD38 expression across different cell populations.

(C) Violin plots illustrated the distribution of CD38 expression levels among various cell populations in normal and ovarian cancer tissues.

(D) Violin plots illustrated CD38 expression patterns among cell populations in primary, metastatic, and relapsed ovarian cancer tissues.

(E) Heatmap showed the intensity of intercellular communication in the GSE118828 dataset.

(F) Comparison of gene expression levels involved in cell-cell interactions between high and low CD38-expressing groups in the GSE9891 dataset (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

(G) qPCR analysis of relative mRNA expression of cell-cell interaction genes in subcutaneous tumors from C57BL/6 mice treated with Compound 78c, normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Our detailed exploration of the TISCH2 database also identified robust tumor cell-fibroblast communication networks mediated by extensive ligand-receptor crosstalk (Fig. 4E). To explore CD38′s impact on tumor-CAFs communication and infiltration, we integrated transcriptomic profiling with CD38-targeted intervention studies. Transcriptomic analysis of the GSE9891 dataset demonstrated that high CD38 expression correlated with increased levels of chemokine signaling (CXCL12-CXCR4), extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling factors (THBS1/2, FN1, collagen isoforms), and immune checkpoint molecules (CD47-SPP1) (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. 3C). In the mouse model, CD38 inhibition reduced mRNA levels of these proteins, along with multiple collagen isoforms (COL1A1/2, COL4A1/2, COL6A1/3) (Fig. 4G, Fig. Supplementary 3D). To delineate CAF subpopulations, we analyzed CAF marker expression in CD38-high samples from GSE9891, revealing significantly elevated FAP and ACTA2 (α-SMA) levels (Fig. 4F). This phenotype was validated in CD38-inhibited mice, showing reduced FAP, CD29, and ACTA2 expression (Fig. 4G). Notably, the FAPhigh CD29med-high SMAhigh phenotype aligned with CAF-S1 subpopulation characteristics, suggesting preferential enrichment of CAF-S1 in CD38-enriched microenvironments.

CD38 is correlated with immune response and immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer

To further investigate the role of CD38 in ovarian cancer, we performed GSEA analysis between CD38 high and low expression groups from TCGA-OV data. The top 15 significantly activated KEGG and hallmark pathways were selected for visualization. KEGG analysis showed that CD38 activated multiple immune-related pathways, including cytokine receptor interactions, NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and T/B cell receptor signaling pathways (Fig. 5A). Hallmark pathway analysis identified CD38 was involved in IL2-STAT5 signaling, IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling, IFN-γ/α response, and PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling (Fig. 5B). GO analysis revealed that CD38 regulated immune processes including T cell activation, cytokine production and immune receptor activity (Fig. 5C). Molecular subtype stratification via TISIDB revealed CD38 expression in immunoreactive and mesenchymal subtypes (Fig. Supplementary 4A), with preferential enrichment in IFN-γ-dominant C2 immune subtypes (Fig. Supplementary 4B). Utilizing the TIP database, we found that CD38 promoted the recruitment of various immune cells, while concurrently suppressing T cell recognition of cancer cells. This suggests a dual role for CD38: attracting T cells to the tumor site while impairing their functional capacity. (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

CD38 is correlated with immune response and immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer

(A) Bubble plot displayed the top 15 KEGG pathways enriched by high CD38 expression in the TCGA-OV dataset.

(B) Bubble plot illustrated the top 15 HALLMARK pathways enriched by high CD38 expression in the TCGA-OV dataset.

(C) Top 10 Gene Ontology terms enriched by CD38 expression in the TCGA-OV dataset.

(D) Correlation analysis between CD38 expression and the Cancer-Immunity Cycle Scores using data from the TIP database.

(E) Correlation analysis between CD38 and immunomodulator genes expression in ovarian cancer using data from TISIDB database.

(F) Comparison of immune checkpoint marker expression between high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA-OV dataset (***p < 0.001).

(G) TIDE scores between the high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA-OV data showed the potential ICB response (n = 188, ***p < 0.001).

Given the potential of CD38 as a target for immune checkpoint therapy in solid tumors, we analyzed its correlation with immunomodulators using the TIP database. We discovered a positive correlation between CD38 expression and numerous key immune checkpoint molecules: CD274 (PD-L1), CTLA-4, HAVCR2 (TIM-3), LAG3, PDCD1 (PD-1), PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2), and TIGIT, all of which were significantly upregulated in ovarian cancer with elevated CD38 expression (Fig. 5E, Fig. Supplementary 4C-D). Additionally, TIDE scores predicted the impact of CD38 on ICB response. Lower CD38 expression got higher TIDE scores, indicating a potential limited response to ICB therapy (Fig. 5G).

CD38 promotes ovarian cancer growth, metastasis and immune cell infiltration in vivo

To validate the oncogenic role of CD38 in vivo, we established ID8-OVE-CD38 and ID8-Vector subcutaneous ovarian cancer models in C57BL/6 mice. After 6 weeks, ID8-OVE-CD38 group exhibited a significant increase in tumor volume and weight (Fig. 6A-C). Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated CD38-driven immune remodeling, showing increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in ID8-OVE-CD38 group (Fig. 6D). For metastasis studies, Balb/c nude mice were intraperitoneally injected with SKOV3-OVE-CD38 or SKOV3-Vector cells. After 4 weeks, the CD38 overexpression group exhibited a higher frequency of metastatic lesions in various sites, including the diaphragmatic region, gastric serosa, liver, mesentery, and pelvic cavity, with notably more mesenteric metastases (Fig. 6D-E).

Fig. 6.

CD38 promotes ovarian cancer proliferation, metastasis and immune cell infiltration in vivo

(A) Tumor formation in C57BL/6 mice ubcutaneously injected with ID8 cells stably expressing vector or CD38 (ID8-Vector or ID8-OVE-CD38). After 6 weeks, tumors were excised and photographed.

(B) Quantification of tumor volume and total tumor weight in the transplanted tumors (n = 7 for ID8-Vector, n = 5 for ID8-OVE-CD38, *p<0.05, ***p < 0.001).

(C) Flow cytometry detected T cell proportion in the transplanted tumors (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05).

(D) Abdominal metastases in BALB/c nude mice intraperitoneally injected with SKOV3 cells stably expressing vector or CD38 (SKOV3-Vector or SKOV3-OVE-CD38). After 4 weeks, tumors were excised and photographed. Upper panels: peritoneal metastasis nodules. Lower panels: mesenteric metastasis nodules.

(E) Quantification of peritoneal metastasis nodules counts and total tumor weight, n = 7 for SKOV3-Vector, n = 6 for SKOV3-OVE-CD38, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). The proportion of mesenteric metastases nodules was evaluated using Fisher's exact test (*p < 0.05).

(F) Tumor formation in C57BL/6 mice subcutaneously injected with ID8 cells. After 4 weeks, Compound 78c were administered intraperitoneally (10 mg/kg/dose) every two days for 3 weeks. Tumors were excised and photographed.

(G) Quantification of tumor volume in the transplanted tumors (n = 5 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

(H) Flow cytometry detected proportion of CD38-positive TCs and TILs, CD4/8 + T cells, macrophages, and PD-L1-positive cells in the transplanted tumors (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of CD38 inhibitor (compound 78c), wild-type ID8 cells were injected into C57BL/6 to build the subcutaneous tumor model. Four weeks post-implantation, mice received intraperitoneal administration of compound 78c for three consecutive weeks. CD38 inhibitor significantly inhibited tumor volume and weight (Fig. 6F-G). Flow cytometry showed decreased CD38+ tumor cells and TILs in the treatment group, and reduced infiltration of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and M2 macrophages. Besides, CD38 inhibitor inhibited PD-L1 expression on tumor cell surface (Fig. 6H).

CD38 promotes ovarian cancer progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR and IL6-JAK-STAT3 pathways

GSEA analysis demonstrated that high CD38 expression was associated with activation of IL6-JAK-STAT3 and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways (Figs. 5B and 7A). To validate these findings, we investigated the regulatory role of CD38 on core genes in these pathways. RT-qPCR showed that CD38 overexpression in A2780 cells upregulated mRNA level key PI3K-AKT pathway components (PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PTEN, AKT1) and downstream targets (cMYC, STAT3, mTOR, BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1) (Fig. 7B). In subcutaneous tumors treated with CD38 inhibitors, there was significant downregulation of PIK3CA, PIK3CB, AKT1, PTEN and BCL-XL (Fig. 7C). Consistent with transcriptional changes, protein levels of PIK3CA, AKT1, p-AKT1, PTEN and p-PTEN were significantly positively regulated by CD38 expression in ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, CD38-overexpressing tumors exhibited elevated IL-6 levels (Fig. 7E). CD38 inhibitors reduced expression of IL-6 signaling pathway components (IL-6, IL-6R, JAK2, STAT3, SOCS1) in tumor (Fig. 7F), further supporting CD38′s role in this cascade reaction. Dataset analysis from GSE9891 corroborated these results, demonstrating elevated expression of these genes in CD38-high tumors (Fig. 7G).

Fig. 7.

CD38 promotes ovarian cancer tumorigenesis through PI3K-AKT and IL-6 pathway

(A) KEGG enrichment plot of CD38 involvement in JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT pathways.

(B) qPCR analysis of relative core gene mRNA expression in the PI3K-AKT pathway in A2780 cells stably expressing vector or CD38 (Vector or OVE-CD38), normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

(C) qPCR analysis of relative CD38 and core gene mRNA expression in the PI3K-AKT pathway in subcutaneous tumors from C57BL/6 mice treated with Compound 78c, normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

(D) Western blot analysis of core protein expression levels in the PI3K-AKT pathway in A2780 cells stably expressing vector or CD38 (Vector or OVE-CD38), and CAOV3 cell lines stably expressing shNC or shCD38 (shNC or shCD38).

(E) Luminex liquid suspension chip assay for 27 chemokines levels in SKOV3-Vector or SKOV3-OVE-CD38 mouse subcutaneous tumor tissues.

(F) qPCR analysis of relative core gene mRNA expression in the IL6 pathway in subcutaneous tumors from C57BL/6 mice treated with Compound 78c, normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

(G) Comparative expression analysis of IL6 pathway core genes between high and low CD38-expressing groups in the GSE9891 dataset (***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Discussion

CD38 function exhibits remarkable heterogeneity in solid tumors. While its overexpression in most malignancies drives oncogenesis through dual synergistic mechanisms: (1) metabolic reprogramming via enhanced glycolysis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and fatty acid synthesis to sustain tumor bioenergetics [[29], [30], [31], [32]]; (2) calcium-dependent activation of oncogenic signaling cascades that promote cell adhesion, migration, and metastatic dissemination [33,34]. Conversely, in prostate and pancreatic cancers, CD38 exerts tumor-suppressive effects by disrupting the NAD salvage pathway, resulting in metabolic collapse and subsequent cell death [35,36]. Notably, the pathophysiological significance of CD38 in ovarian cancer remains underexplored. Our investigation identifies CD38 upregulation as a critical oncogenic driver of ovarian cancer, demonstrating that CD38-mediated activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling axis promotes tumor progression and metastasis in experimental models. This discovery positions CD38 as a potential therapeutic target in ovarian malignancies, warranting further mechanistic exploration.

Although increased CD38 expression on TIICs has been reported in various cancers [[37], [38], [39]], its role in ovarian cancer remains underexplored. Our study revealed high CD38 expression on TIICs in ovarian cancer, which positively correlated with immune infiltration level. In the TME, CD38 increases adenosine to recruit immunosuppressive cells and directly inhibiting immune cell function—such as CD8+ T, NK, DC cells— through A2AR signaling [40]. Intriguingly, our bioinformatics analyses indicated a dual functionality for CD38, recruiting both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing immune cells. Prior studies have demonstrated that T cells in HGSOC exhibit limited ability to recognize cancer cells [41]. Additionally, CD38 is linked to CD8+ T cell exhaustion in ovarian cancer, marked by decreased effector function and persistent activation of inhibitory receptors [42]. In our experiments, we also discovered that CD38 inhibits the ability of T cells to recognize cancer cells. These findings collectively reveal the complex role of CD38 in ovarian cancer: it facilitates immune cell infiltration while simultaneously suppressing their effector functions. This dual role ultimately shapes an immune microenvironment that favors tumor progression, underscoring its potential as a promising therapeutic target.

In vivo experiments showed that a CD38 inhibitor effectively inhibited tumor growth in C57BL/6 mice, indicating its tumor-suppressing function. Further flow cytometry analysis revealed that the treatment markedly reduced the number of tumor cells. To explore the underlying mechanisms, we analyzed the tumor immune microenvironment using flow cytometry and found that CD38 inhibitors exhibit multi-layered immunomodulatory effects. The analysis showed a significant reduction in CD38-positive TILs, with decreased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, indicating that CD38 inhibitors comprehensively suppress CD38-mediated immune cell recruitment. Moreover, CD38 inhibitor decreased PD-L1 expression on tumor cells, impeding immune escape. Furthermore, CD38 inhibitor preferentially reduced M2 macrophages infiltration, further supporting its therapeutic role in ovarian cancer.

Beyond their intended pharmacological effects on CD38, potential off-target actions must be carefully evaluated. Some CD38 inhibitors may cross-react with structurally related NAD+-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CD157, CD203a) due to conserved catalytic domains [43], while certain small molecules could inadvertently modulate purinergic receptors (P2X/P2Y families) through interference with ADPR metabolism [44]. Inhibition may also disrupt intracellular NAD+ homeostasis, indirectly affecting PARP-mediated DNA repair, sirtuin-dependent epigenetic regulation, and mitochondrial function [45]. A comprehensive assessment of these potential off-target effects is essential for therapeutic development. Key approaches to reduce off-target activity may involve (1) engineering monoclonal antibodies with extreme selectivity (2) structure-guided small-molecule optimization to exploit CD38-specific conformations, and (3) systematic off-target screening using proteome-wide binding assays in early drug development.

CD38 is widely expressed in immune cells, endothelial cells, and neurons, and participates in multiple physiological processes through its enzymatic activities [7]. Therefore, CD38 inhibition might lead to unintended immune modulation beyond the intended therapeutic effects. Its inhibition could also affect NAD+ homeostasis, potentially impacting cellular energy metabolism and calcium signaling pathways. Moreover, CD38 is expressed in vascular endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes, where it may influence vascular tone and cardiac function through ADPR signaling [46].

The CD38 inhibitor (compound 78c) and the clinically used CD38 monoclonal antibody (Daratumumab) have both been pharmacokinetically tested and shown to possess high specificity [47,27]. Anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies, such as Daratumumab and Isatuxima, represent the first immunotherapeutic approach in multiple myeloma. They have shown favorable safety profiles with minimal off-target effects at therapeutic doses [48,49]. The development of tissue-specific or activity-specific CD38 modulators may further improve the therapeutic window by minimizing off-target actions while maintaining desired pharmacological effects.

Current immunotherapeutic strategies for ovarian cancer primarily encompass ICB, tumor antigen vaccines, and immunostimulatory cytokines, yet demonstrate limited clinical efficacy and remain excluded from standard treatment regimens. ICB has been extensively investigated in cancer immunotherapy. however, PD-L1 blockade demonstrated an objective response rate (ORR) below 10 % in the JAVELIN ovarian cancer trial [50]. Resistance to PD-L1 blockade is associated with multifaceted immunosuppressive mechanisms in the TME, including T cell exhaustion, aberrant infiltration of immunosuppressive cells (M2-TAMs, Tregs), and heterogeneous PD-L1 expression [51]. Notably, we identified a positive correlation between CD38 and multiple immune checkpoint molecules (such as PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4) suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker for ICB therapy. Furthermore, CD38 hyperexpression suppressed T cell functionality. Treatment with CD38 inhibitors significantly reduced PD-L1 expression, diminished M2-TAMs infiltration, and remodeled the immunosuppressive TME, indicating that CD38 inhibitors have the potential to target a broader immune suppression network. In lung cancer, combining CD38 inhibition with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has demonstrated synergistic anti-tumor effects, offering insights for preclinical research in ovarian cancer [15]. To further enhance the efficacy of CD38-targeted therapy, we propose identifying potential biomarkers that could benefit from such treatment: detecting CD38+ immunosuppressive cells (such as Tregs) in ascites; monitoring changes in plasma NAD+ or adenosine levels, as elevated levels of these biomarkers may indicate activation of the CD38-mediated pathway. Future investigations should employ multi-omics approaches (e.g., single-cell transcriptomics coupled with spatial proteomics) to delineate CD38high molecular subtypes, thereby establishing a precision biomarker framework to guide personalized immunocombination therapies.

CAFs can establish a robust cross-communication with cancer cells, thereby contributing to diverse biological processes [52]. A previous study has demonstrated that stromal CD38 deficiency suppresses solid tumor growth, diminishes CAFs density, and diminishes angiogenesis [53,54]. Our IHC analysis revealed significant CD38 upregulation in stromal compartments, while CD38-inhibited mouse tumor models showed concurrent downregulation of several fibroblast-specific markers, suggesting its role in facilitating fibroblast infiltration. We also observed robust intercellular communication between CAFs and ovarian cancer cells, supported by single-cell data, transcription datasets and CD38-inhibited mouse models. Furthermore, CD38 influences some proteins expression, including IGF1, IGF2, ITGA5 and ANGPTL2 (Fig. Supplementary 3C-D) which are associated with angiogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis in ovarian cancer. iCAFs further reinforce tumor progression through IL-6 and the JAK-STAT pathway activation, consistent with elevated IL-6 levels observed in CD38-high ovarian and their potential modulation of JAK2-STAT3 pathway. CAFs can modulate the immune environment by interacting with TIICs and other components, thereby shaping an immunosuppressive TME [55]. Despite these insights, a comprehensive understanding of CD38′s role in the interactions between CAFs and the immune microenvironment is lacking. Further research into the complex mechanisms is essential for developing novel immunotherapeutic strategies targeting stromal-tumor crosstalk in ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

In summary, this study highlights the pivotal role of CD38 in driving progression of EOC and its influence on the remodeling of the TME. CD38 regulates the PI3K-AKT and IL-6 signaling pathways, contributing to the increased malignancy of ovarian cancer. It is notably upregulated in immune cells and stromal cells, facilitating their infiltration into the TME. This upregulation also impedes T cell recognition of tumor cells and enhances the communication between CAFs and tumor cells. CD38 expression is also associated with multiple immune checkpoints within the EOC microenvironment and modulates the response to immune checkpoint blockade. Importantly, CD38 inhibitors have proven effective in curbing EOC progression, diminishing immune cell infiltration, and decreasing immune checkpoints expression, such as PD-L1. Therefore, CD38 may represent a promising immunotherapeutic target for ovarian cancer.

List of abbreviations

TME=tumor microenvironment; EOC= epithelial ovarian cancer; IHC= immunohistochemistry; CAFs= cancer-associated fibroblasts; OS= overall survival; FBS=fetal bovine serum; TCGA= Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx= Genotype-Tissue Expression; DEGs= Differentially Expressed Genes; TIP =Tracking Tumor Immunophenotype; TISCH2=Tumor Immune Single-cell Hub 2; ICB= immune checkpoint blockade; GSEA= Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; GO= Gene Ontology; KEGG= Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TCs= tumor cells; TILs= tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; FLCs= fibroblast-like cells; myCAF= myofibroblast CAF; iCAF= inflammatory CAF;

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol was established, according to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Mouse studies have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the approval number is 2023AW026.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wei Wang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xiangnan Liu: Validation, Investigation. Shengjie Xu: Validation, Investigation. Enci Dai: Visualization, Investigation. Yingying Li: Visualization, Investigation. Yinping Liu: Funding acquisition. Liyun Shan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Yanli Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grand No. 82072868), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grand No. 18ZR1430500) and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Youth Fund (Grand No. 202004Y0063).

Availability of data and material

Data are available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Yang Rui for her contribution to this article. We appreciate Dr. Enrun Zheng (Peking university, Beijing) for his guidance on part of the bioinformatics analysis of this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2025.102414.

Contributor Information

Wei Wang, Email: wangwei980423@sjtu.edu.cn.

Xiangnan Liu, Email: lxnan257@163.com.

Shengjie Xu, Email: xuxdc@qq.com.

Enci Dai, Email: daiencixixi@sjtu.edu.cn.

Yingying Li, Email: liyingying1119@sjtu.edu.cn.

Yinping Liu, Email: DrLYP116@163.com.

Liyun Shan, Email: 18121288193@139.com.

Yanli Li, Email: liecho121@126.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Figure 1 (A) Pan-cancer analysis of CD38 expression from TCGA and GTEx databases (*p<0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001). (B) CD38 expression levels in different ovarian cancer cell lines from CCLE database. (C) CD38 expression levels in various immune cells, as reported by the GEPIA2021 database. (D) CIBERSORT scores of TILs between high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA-OV database (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Figure 2 (A-D) Confirmation of CD38 overexpression in CAOV3 (A), A2780 (C), and SKOV3 (D) cells transfected with Vector or OVE-CD38 constructs by qPCR and western blot. Knockdown of CD38 in CAOV3 (B) cells transfected with shNC or shCD38 constructs was also confirmed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001). (E) Cell viability of CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 was evaluated every 24 h for 5 days using the CCK-8 assay (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). OD values reflect relative cell proliferation (n = 5 per group). (F) Colony formation assays for CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 (n = 3 per group *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of colony numbers. (G) Wound healing assays for CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 at 0 and 72 h (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of migration distance. (H) Transwell assay to assess migration and invasion abilities of CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of migrated and invaded cell numbers. Scale bars: 250 μm.

Sup figure 3 (A) Cell type annotation for six datasets, categorized based on malignancy. Heatmap showed the average gene expression of CD38 in different populations of malignant, immune and stromal cells. (B) Ligand-receptor interactions between tumor microenvironment cells and malignant cells. (C) Comparative analysis of cell-cell interaction gene expression between high and low CD38 expression groups in the GSE9891 dataset (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). (D) qPCR analysis of relative mRNA expression of cell-cell interaction genes in subcutaneous tumors from C57BL/6 mice treated with Compound 78c, normalized to β-actin (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Sup figure 4 (A) Analysis of CD38 expression across different molecular subtypes of ovarian cancer using data from the TISIDB database. (B) Analysis of CD38 expression across different immune subtypes of ovarian cancer using data from the TISIDB database. (C-D) Comparative expression of immunomodulators between high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA- OV dataset (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

Sup figure 5 (A) Flow cytometry detection of CD4/CD8+ T cells from subcutaneous ID8-Vector or ID8-OVE-CD38 tumor tissues. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process. (B) Flow cytometry detection of CD38+ TCs and TILs from subcutaneous ID8 tumor tissues treated with Compound 78c. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process. (C) Flow cytometry detection of CD4/CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and PD-L1-positive cells from subcutaneous ID8 tumor tissues treated with Compound 78c. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process.

Sup figure 6 Original images of the full western blot separately.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lheureux, S., C. Gourley, I. Vergote, and A.M. Oza Epithelial ovarian cancer(1474-547X (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ribas A., Wolchok J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359(6382):1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odunsi K. Immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_8):viii1–viii7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogan K.A., Chini C.C.S., Chini E.N. The multi-faceted ecto-enzyme CD38: roles in immunomodulation, cancer, aging, and metabolic diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1187. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horenstein A.L., Chillemi A., Zaccarello G., Bruzzone S., Quarona V., Zito A., Serra S., Malavasi F. A CD38/CD203a/CD73 ectoenzymatic pathway independent of CD39 drives a novel adenosinergic loop in human T lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(9) doi: 10.4161/onci.26246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Yang R., Chen L., Wu S. CD38 as an immunomodulator in cancer. Future Oncol. 2020;16(34):2853–2861. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeidler J.D., et al. The CD38 glycohydrolase and the NAD sink: implications for pathological conditions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022;322(3):C521–c545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00451.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horenstein A.L., Bracci C., Morandi F., Malavasi F. CD38 in adenosinergic pathways and metabolic re-programming in Human multiple myeloma cells: in-tandem insights from basic science to therapy. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:760. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damle R.N., et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94(6):1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karan-Djurasevic T., et al. Expression of Bcl2L12 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients: association with clinical and molecular prognostic markers. Med. Oncol. 2013;30(1):405. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joosse M.E., et al. Frequencies of circulating regulatory TIGIT(+)CD38(+) effector T cells correlate with the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12(1):154–163. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konjević G., Jović V., Jurisić V., Radulović S., Jelić S., Spuzić I. IL-2-mediated augmentation of NK-cell activity and activation antigen expression on NK- and T-cell subsets in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with interferon-alpha and DTIC. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2003;20(7):647–655. doi: 10.1023/a:1027387930868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malavasi F., Funaro A., Alessio M., DeMonte L.B., Ausiello C.M., Dianzani U., Lanza F., Magrini E., Momo M., Roggero S. CD38: a multi-lineage cell activation molecule with a split personality. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 1992;22(2):73–80. doi: 10.1007/bf02591400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L., et al. CD38-Mediated immunosuppression as a mechanism of tumor cell escape from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1156–1175. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitt J.M., Marabelle A., Eggermont A., Soria J.C., Kroemer G., Zitvogel L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27(8):1482–1492. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Givel A.M., et al. miR200-regulated CXCL12β promotes fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppression in ovarian cancers. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03348-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M., Chen Z., Wang Y., Zhao H., Du Y. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(11) doi: 10.3390/cancers14112637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y.L., Ye F., Cheng X.D., Hu Y., Zhou C.Y., Lü W.G., Xie X. Identification of glia maturation factor beta as an independent prognostic predictor for serous ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2010;46(11):2104–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding L., Ren J., Zhang D., Li Y., Huang X., Ji J., Hu Q., Wang H., Ni Y., Hou Y. The TLR3 agonist inhibit drug efflux and sequentially consolidates low-dose cisplatin-based chemoimmunotherapy while reducing side effects. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16(6):1068–1079. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-16-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salgado R., et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26(2):259–271. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu S., Yang Y., Wang X., Liu X., Jin C., Ma M., Wu S., Li Y. γ-glutamyl cyclotransferase contributes to endometrial carcinoma malignant progression and upregulation of PD-L1 expression during activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;81 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li C., Tang Z., Zhang W., Ye Z., Liu F. GEPIA2021: integrating multiple deconvolution-based analysis into GEPIA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W242–w246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun D., et al. TISCH: a comprehensive web resource enabling interactive single-cell transcriptome visualization of tumor microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1420–d1430. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X., Zhou T., Chen X., Wang Y., Ding Y., Tu H., Gao S., Wang H., Tang X., Yang Y. System analysis based on the cancer-immunity cycle identifies ZNF207 as a novel immunotherapy target for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10(3) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-004414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarragó M.G., et al. A potent and specific CD38 inhibitor ameliorates age-related metabolic dysfunction by reversing tissue NAD(+) decline. Cell Metab. 2018;27(5) doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.016. 1081-1095.e1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jurisic V., Srdic-Rajic T., Konjevic G., Bogdanovic G., Colic M. TNF-α induced apoptosis is accompanied with rapid CD30 and slower CD45 shedding from K-562 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;239(3):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao L., et al. The intrinsic role and mechanism of tumor expressed-CD38 on lung adenocarcinoma progression. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(7):680. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03968-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurisic V., Kraguljac N., Konjevic G., Spuzic I. TNF-alpha induced changes in cell membrane antigen expression on K-562 cells associated with increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. Neoplasma. 2005;52(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao S., Liang L., Yue C., He J., He Z., Jin X., Luo G., Zhou Y. CD38 is involved in cell energy metabolism via activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2020;57(1):338–354. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wo Y.J., Gan A.S.P., Lim X., Tay I.S.Y., Lim S., Lim J.C.T., Yeong J.P.S. The roles of CD38 and CD157 in the solid tumor microenvironment and cancer immunotherapy. Cells. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.3390/cells9010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbosa M.T., Soares S.M., Novak C.M., Sinclair D., Levine J.A., Aksoy P., Chini E.N. The enzyme CD38 (a NAD glycohydrolase, EC 3.2.2.5) is necessary for the development of diet-induced obesity. Faseb. J. 2007;21(13):3629–3639. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8290com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camacho-Pereira J., et al. CD38 Dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an SIRT3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1127–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chini C.C., Guerrico A.M., Nin V., Camacho-Pereira J., Escande C., Barbosa M.T., Chini E.N. Targeting of NAD metabolism in pancreatic cancer cells: potential novel therapy for pancreatic tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(1):120–130. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-13-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chmielewski J.P., et al. CD38 Inhibits prostate cancer metabolism and proliferation by reducing cellular NAD(+) pools. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018;16(11):1687–1700. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.Mcr-17-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo C., et al. CD38 in advanced prostate cancers. Eur. Urol. 2021;79(6):736–746. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karakasheva T.A., Dominguez G.A., Hashimoto A., Lin E.W., Chiu C., Sasser K., Lee J.W., Beatty G.L., Gabrilovich D.I., Rustgi A.K. CD38+ M-MDSC expansion characterizes a subset of advanced colorectal cancer patients. JCI Insight. 2018;3(6) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karakasheva T.A., et al. CD38-Expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote tumor growth in a murine model of esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(19):4074–4085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-14-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young A., Mittal D., Stagg J., Smyth M.J. Targeting cancer-derived adenosine: new therapeutic approaches. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(8):879–888. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-14-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheper W., et al. Low and variable tumor reactivity of the intratumoral TCR repertoire in human cancers. Nat. Med. 2019;25(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi T., Yan R., Han M.I. System analysis based on the T cell exhaustion‑related genes identifies CD38 as a novel therapy target for ovarian cancer. Oncol. Res. 2023;31(4):591–604. doi: 10.32604/or.2023.029282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohta A. A metabolic immune checkpoint: adenosine in tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:109. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carracedo S., Launay A., Dechelle-Marquet P.A., Faivre E., Blum D., Delarasse C., Boué-Grabot E. Purinergic-associated immune responses in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2024;243 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2024.102693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navas L.E., Carnero A. NAD(+) metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021;6(1):2. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00354-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takasawa S., Makino M., Uchiyama T., Yamauchi A., Sakuramoto-Tsuchida S., Itaya-Hironaka A., Takeda Y., Asai K., Shobatake R., Ota H. Downregulation of the Cd38-cyclic ADP-ribose signaling in cardiomyocytes by intermittent hypoxia via pten upregulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(15) doi: 10.3390/ijms23158782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim K., Phelps M.A. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Daratumumab. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2023;62(6):789–806. doi: 10.1007/s40262-023-01240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gozzetti A., Ciofini S., Simoncelli M., Santoni A., Pacelli P., Raspadori D., Bocchia M. Anti CD38 monoclonal antibodies for multiple myeloma treatment. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(5) doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2052658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van de Donk N., Pawlyn C., Yong K.L. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2021;397(10272):410–427. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Disis M.L., et al. Efficacy and safety of Avelumab for patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: phase 1b results from the JAVELIN solid tumor trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(3):393–401. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan Y., Adam A., Zhao C., Chen H. Recent advancements in the mechanisms underlying resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(4) doi: 10.3390/cancers13040663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16(9):582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ben Baruch B., Blacher E., Mantsur E., Schwartz H., Vaknine H., Erez N., Stein R. Stromal CD38 regulates outgrowth of primary melanoma and generation of spontaneous metastasis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(61):31797–31811. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben Baruch B., Mantsur E., Franco-Barraza J., Blacher E., Cukierman E., Stein R. CD38 in cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes pro-tumoral activity. Lab Invest. 2020;100(12):1517–1531. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mao X., Xu J., Wang W., Liang C., Hua J., Liu J., Zhang B., Meng Q., Yu X., Shi S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 (A) Pan-cancer analysis of CD38 expression from TCGA and GTEx databases (*p<0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001). (B) CD38 expression levels in different ovarian cancer cell lines from CCLE database. (C) CD38 expression levels in various immune cells, as reported by the GEPIA2021 database. (D) CIBERSORT scores of TILs between high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA-OV database (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Figure 2 (A-D) Confirmation of CD38 overexpression in CAOV3 (A), A2780 (C), and SKOV3 (D) cells transfected with Vector or OVE-CD38 constructs by qPCR and western blot. Knockdown of CD38 in CAOV3 (B) cells transfected with shNC or shCD38 constructs was also confirmed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM normalized to β-actin (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001). (E) Cell viability of CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 was evaluated every 24 h for 5 days using the CCK-8 assay (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). OD values reflect relative cell proliferation (n = 5 per group). (F) Colony formation assays for CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 (n = 3 per group *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of colony numbers. (G) Wound healing assays for CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 at 0 and 72 h (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of migration distance. (H) Transwell assay to assess migration and invasion abilities of CAOV3 cells stably expressing Vector or CD38 (n = 3 per group, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Left: representative images. Right: quantification of migrated and invaded cell numbers. Scale bars: 250 μm.

Sup figure 3 (A) Cell type annotation for six datasets, categorized based on malignancy. Heatmap showed the average gene expression of CD38 in different populations of malignant, immune and stromal cells. (B) Ligand-receptor interactions between tumor microenvironment cells and malignant cells. (C) Comparative analysis of cell-cell interaction gene expression between high and low CD38 expression groups in the GSE9891 dataset (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). (D) qPCR analysis of relative mRNA expression of cell-cell interaction genes in subcutaneous tumors from C57BL/6 mice treated with Compound 78c, normalized to β-actin (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Sup figure 4 (A) Analysis of CD38 expression across different molecular subtypes of ovarian cancer using data from the TISIDB database. (B) Analysis of CD38 expression across different immune subtypes of ovarian cancer using data from the TISIDB database. (C-D) Comparative expression of immunomodulators between high and low CD38 expression groups in the TCGA- OV dataset (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001).

Sup figure 5 (A) Flow cytometry detection of CD4/CD8+ T cells from subcutaneous ID8-Vector or ID8-OVE-CD38 tumor tissues. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process. (B) Flow cytometry detection of CD38+ TCs and TILs from subcutaneous ID8 tumor tissues treated with Compound 78c. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process. (C) Flow cytometry detection of CD4/CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and PD-L1-positive cells from subcutaneous ID8 tumor tissues treated with Compound 78c. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software, and the representative image shows the flow sorting process.

Sup figure 6 Original images of the full western blot separately.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.