Abstract

Artificial implants have consistently been recognized as the most effective clinical strategy for repairing bone fractures and defects, particularly in orthopedics and stomatology. Nowadays, the focus of bone repair has shifted from basic fixation and structural restoration to the reconstruction of multifunctional “live” tissue to mimic the natural bone microenvironment. However, developing the smart implants with ideal osteogenesis-related multi-functions remains challenging, as the effects of physicochemical properties of implant materials on intracellular signaling, stem cell niches, and tissue regeneration are not yet fully understood. Herein, we systematically explore recent advancements in innovative strategies for bone repair and regeneration, revealing the significance of the smart implants that closely mimic the natural structure and function of bone tissue. Adaptation to patient-oriented osteogenic microenvironments, dynamic osteoblastogenesis-osteoclastogenesis balance, antibacterial/bactericidal capacity, vascularization, and osteoimmunomodulatory capacity and their regulatory mechanisms achieved by biomaterials design and functional modifications are thoroughly summarized and analyzed. Notably, the popular research on multifunctional platforms with synergetic interactions between different functions and treatment of complex clinical issues, including the emerging neurogenic bone repair, is also significantly discussed for developing more intelligent implants. By summarizing recent research efforts, this review proposes the latest multifunctional strategies and synergistic mechanisms of smart bone implants, aiming to provide better bone defect repair applications that more closely mimic the natural bone tissue.

Keywords: Smart bone implants, Osteogenesis, Multifunctional strategy, Synergistic mechanism, Neurogenic bone repair

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Smart implants tend to more closely mimic and regenerate natural bone tissue.

-

•

Patient-oriented osteogenic microenvironments and bone metabolism are important.

-

•

Antibacterial capacity, vascularization, and osteoimmunomodulation are main osteogenesis-related functions.

-

•

Smart implants achieve synergetic interactions between different functions and complex clinical issues.

-

•

Herein, multifunctional strategies can promote more complex bone reconstruction.

1. Introduction

Bone injuries and defects caused by trauma, tumors, osteoporosis, or severe infection present significant challenges in clinical practice, particularly in orthopedics and stomatology, seriously impairing the quality of millions of individuals life [[1], [2], [3]]. Among the development of aging society, the orthopaedic disorders already occupy a significant proportion of the global burden of disease, notably in the low and middle-income countries, and its injury has reached 11.2 % of the total disability-adjusted life-years worldwide [4,5]. Hence, the demand for clinical therapy techniques and corresponding high-performance implants of the orthopaedic injury is becoming more urgent. Traditional approaches to bone repair, such as autografts and allografts, which have many limitations, including limited donor resource, risk of infection, and immunological rejection, prompting the development of artificial implants as more effective solutions [6,7]. Over the years, the focus of bone repair strategies has evolved from mere structural fixation and shape restoration to the reconstruction of living and multifunctional tissues that closely mimic the natural bone microenvironment [8].

During continual evolution, human skeleton with hundreds of bones endows the unique shape and macro/microstructures [9], which mainly provide the role of supporting human tissues and organs, shaping human body (mechanical function) [10]; producing blood cells (i.e., hematopoiesis) by bone marrow in cancellous part (synthetic function) [11]; releasing of neurogenic factor by the highly neurovascular coupling (secretory function) [12]; keeping the balance of mineral, fat and pH value [13], and detoxicating (metabolic function) [14]. To achieve the biological performance closer to natural bone such as sufficient bioactivity [15], biocompatibility [16], osteogenesis [17], osteoconduction [18], and osteoinduction [19], the concept of “smart bone implants” is gradually emerging. Unlike traditional implants that primarily provide mechanical support, the smart bone implants actively interact with the biological microenvironment, facilitating bone repair and regeneration to match the microstructure and above functions of natural bone tissue as much as possible [20]. By integrating advanced biomaterials, bioinspired structural designs, and functional adaptability, these implants dynamically regulate cellular responses, promote bone regeneration, and optimize microstructural and functional compatibility with natural bone tissue [21]. As shown in Fig. 1, an ideal smart bone implant should not only replicate the natural bone's microstructure but also integrate intelligent, multifunctional features that dynamically influence bone repair and regeneration. This requires a multifunctional approach, integrating features such as being endowed with interconnected porous structure, sufficient strength and hardness, anticipated osteogenesis, bacteriostasis and anti-infection, rational regulation of immune response, promoting internal neovascularization and blood circulation, regaining the awareness of pain and perception (nerve repair and regeneration), and tightly combining with bone tissue in vivo [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Thus, the development of smart bone implants necessitates a comprehensive and synergistic design strategy that mimics the structural, mechanical, and biological complexity of natural bone while actively modulating the local microenvironment to achieve enhanced functional integration and long-term clinical efficacy.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the functional design framework for smart bone implants integrating material properties, regulating cellular behaviours and synergistic functions, and fulfilling clinical requirements.

With the continuous clinical application of metal implants, the strong binding ability of implant to natural bone tissue (also osseointegration) is urgently demanded to overcome the clinical problems such as fractures, nonunion, implant loosening and failure, and periprosthetic infection [26,27]. The emergence of smart implants offers innovative solutions that integrate advanced materials science with biological mechanisms, enabling not only structural support but also active facilitation of the healing process by enhancing osteogenesis, preventing infections, promoting vascularization, modulating the immune response, and supporting neuromodulatory osteogenesis [12,[28], [29], [30]]. These functionalities are achieved through precise material designs, including bioactive coatings, surface nanostructures, and other surface modifications, which dynamically interact with the cellular microenvironment to enhance clinical therapeutic efficacy [31,32]. In recent years, researchers have been devoted to developing smart bone implants, and optimizing existing functions and fabrication approaches of the implants such as effective combination of the above functions, induction and modification of loaded bioactive complexes (e.g., exosome and functional protein). For example, the active regulation of macrophage polarization (M1 and M2 phenotype) is also increasingly studied through designing surface topography of bone implants and introducing some drugs, cytokines and active metal ions, verifying that the immunomodulatory effect of implant is also one of the important functions of osteointegration in bone defect repair [[33], [34], [35]]. However, the smart bone implants proposed inhere has not yet been systematically elaborated in bone tissue engineering. Simultaneously, Simultaneously, when facing complex clinical challenges such as septic prosthetic joint loosening, it is crucial to dynamically regulate biological processes-including osteogenesis, antibacterial properties, vascularization, immunomodulation, and neural regeneration-to restore osseointegration between the implant and natural bone tissue [26]. Therefore, achieving synergistic integration of multifunctional capabilities into implants and developing smart bone implants with functionalities comparable to natural bone tissue remains challenging. A deeper understanding of how the physiochemical properties of implant materials influence intracellular signaling pathways, stem cell niches, and bone regeneration processes is critical for the development of next-generation smart implants. Specifically, integrating dynamic and adaptive functionalities during the bone healing process, such as four-dimensional (4D)-printed implants that can change shape in response to physiological microenvironment, along with strategies that facilitate crosstalk between skeletal and other biological systems, making it more closely mimic the dynamic and hierarchical architecture of natural bone regeneration.

Herein, we systematically present the latest strategies and research perspectives on smart implants for bone tissue repair and regeneration, drawing upon hundreds of relevant publications from the past decade. We comprehensively analyze the patient-specific osteogenic microenvironments encountered in clinical bone repair and the regulatory mechanisms of osteogenesis-related signaling pathways facilitated by smart implants. Notably, the research strategies and synergetic mechanism of multifunctional platforms that closely mimic the performance of natural bone including the neural regeneration within bone tissue, are innovatively summarized and systematically discussed for developing more intelligent implants. This review offers the most recent insights into bone repair, spanning from biomedical materials to underlying biological mechanisms, aiming to provide both technical and theoretical support for the innovative design and clinical application of smart implants in bone repair and regeneration.

2. Osteogenic functions and mechanisms of smart bone implants

Osteogenesis is a vital and basical process in the regenerative healing of skeletal muscle systems, including instances such as fractures [36], total joint arthroplasty [37], and resection of bone tumors [38] during the postoperative recovery stage of skeletal diseases. Robust osteogenic abilities not only enhance bone tissue regeneration and repair but also yield excellent effects in implant osseointegration. Typically, osteogenesis involves the migration of osteoblasts to the site where bone tissue synthesis occurs. They secrete and synthesize collagen and bone protein fibres, subsequently forming new bone tissue by absorbing calcium and phosphorus into the fibres’ pores for precipitation and crystallization [39,40]. Addressing the question of how to promote osteogenesis to enhance bone tissue regeneration represents the most valuable research in orthopaedics and stomatology. The exploration and application of biomaterials, particularly the development of multifunctionally smart implant materials, offer innovative strategies for advancing the healing process of bone tissue defect. In this section, we comprehensively summarize and illustrate the latest strategies and mechanisms for promoting osteogenesis through smart bone implants, focusing on their multifunctional and synergistic effects. These include enhancing osteogenesis, preventing infection, promoting angiogenesis, modulating the immune response, neurogenic regulation, and adapting osteogenic microenvironments (Fig. 2 and Table 1). By integrating these functions, smart bone implants enhance bone repair and regeneration, offering promising clinical applications in orthopaedic biomaterials.

Fig. 2.

Summative scheme of the latest multifunctional strategies and synergistic mechanisms of smart bone implants for enhanced bone repair and regeneration.

Table 1.

Osteogenic function and mechanisms of smart bone implants.

| Implant material | Osteogenic mechanism | Cell | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation of osteogenesis-related signaling pathways | |||

| silica-coated GO/GelMA scaffold | adsorption and release of endogenous BMPs, activation of the BMPs/Smad signaling pathway, released silicon ions triggering the upregulation of BMP2 | BMSCs | [87] |

| nHA/GO/CS scaffold | mild photothermal effect, enhance the BMP2/Smad signaling pathway | MC3T3-E1 cells, human BMSCs | [89] |

| hydrogel delivery system | localized delivery and synergistic release of Mg2+ and Zn2+, upregulate MAPK signal pathway | human BMSCs | [93] |

| nano-Mg(OH)2 films on Ti surfaces | release Mg2+ and create a weakly alkaline microenvironment, promote TGF-β signal pathway | murine C3H10T1/2 cells | [94] |

| functionalized methacrylate hyaluronic acid hydrogels | activate the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway, enhance intracellular calcium levels | human skeletal stem cells | [97] |

| Mg-1Ca/PCL scaffolds | releasing Mg2+, activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | human BMSCs | [96] |

| 3D-printed Mg-1Ca/PCL scaffolds | macro- and microstructures, releasing Mg2+, activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | human BMSCs | [96] |

| PCL polymer film bandage | deliver the WIOTM, asymmetric cell division, enhance β-catenin and Wnt signaling pathway | human SSCs | [98] |

| Balance bone homeostasis | |||

| Mn-TCP | release Mn2+ ions, scavenge ROS, promote osteogenic differentiation | RAW264.7 cells, mouse BMDMs | [101] |

| nanoporous Ti implant | downregulate the integrin-mediated β1/FAKpY397/MAPK pathway, micropitted/nanotubular topography | RAW264.7 cells, MC3T3-E1 cells | [102] |

| hyaluronic acid nanocomposite hydrogel | acidic environment-responsive release of the bisphosphonates, inhibit osteoclast maturation, enhance in situ bone regeneration | RAW264.7 cells, mouse BMMs, rat BMSCs | [103] |

| AdOPG mediated nanoparticulate mineralized collagen glycosaminoglycan scaffold | enhance BMP signaling pathway, uncoupling osteogenic and osteoclastogenic differentiation | human BMSCs, human osteoclasts | [106] |

| high Ca/P ratio CPC scaffold | promote secretion of endogenous TGF-β1 to recruit BMSC, enhance osteoclastogenesis | mouse BMMs, rat BMSCs | [108] |

| Regulation of autophagic flux | |||

| negative pressure hydrogels with BMSCs | promote AMPK-ULK1 (unc-51-like kinase 1)-autophagy axis | rat BMSCs | [115] |

| LDO nanosheet coated Ti | Release of Mg2+ and Ga3+, generate an appropriate alkaline microenvironment (about pH 8.5), promote AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways | rat BMSCs | [120]. |

| Sr-doped micro/nano rough Ti | upregulate Akt-mTOR-dependent signaling pathways, altered RANK/RANKL/OPG axis | rat BMSCs, rat BMDMs | [122]. |

| Biomaterials surface morphology enhance osteogenesis | |||

| nanotopographical titanium plates | release of pro-osteogenesis sEV (Ti4-21-sEVs) | human BMSCs | [129] |

| sEV decorated 3D-printed PEEK scaffold | time-dependent osteogenic activity, deliver osteogenic miRNAs | human BMSCs | [129] |

| exosomes modified 3D-printed Ti alloy scaffold | upregulate osteogenic miRNAs level, activate PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways | human BMSCs | [130] |

| micron-size micropillar arrays on Ti surface | modulate nuclear deformation, alter chromatin organization | human BMSCs | [131] |

| methacrylated poly(octamethylene citrate) micropillar implant | nuclear deformation, lamin A/C multimerization, alter chromatin conformation and reprogramming | human BMSCs | [132] |

| flower-like nanostructures CaSiO3 bioceramics | promote cell adhesion and ALP activity, enhance FAK/p38 signaling pathway | rat BMSCs | [135] |

2.1. Diverse patient-oriented osteogenic microenvironments

The term “osteogenic microenvironment” refers to the local biological milieu surrounding bone tissue, where a delicate interplay of bone metabolism-related cellular and signal molecules orchestrates the intricate processes of osteogenesis-the formation of new bone [41,42]. In clinical practice, patients with conditions such as osteoporosis, menopause, obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and thyroid dysfunction often experience impaired bone tissue healing due to a disrupted osteogenic microenvironment [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47]]. Therefore, designing smart implants to meet the specific needs of patients undergoing bone repair becomes pivotal in the realm of orthopaedic treatments, as it profoundly ameliorates the osteogenic microenvironment compromised by various diseases to accelerate bone tissue regeneration.

One crucial consideration in achieving optimal osteogenic microenvironment is addressing bone density-related issues such as osteoporosis. For patients afflicted by senile osteoporosis, postmenopausal osteoporosis, and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, they are mainly characterized by decreased bone mineral density, compromised skeletal strength, and trabecular microstructure, as well as an increased risk of fractures [[48], [49], [50]]. In the osteoporotic marrow, accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proinflammatory cytokines can create a chronic inflammatory state, which not only activates osteoclast precursors for promoting bone resorption but also suppresses the number of osteoblasts [51,52]. In cases where patients present with comorbidities such as estrogen, glucocorticoid, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) deficiency, the regulatory pathways governing bone metabolism are further disrupted in bone repair procession [53]. Estrogen deficiency, for instance, is associated with decreased osteoblast activity, while glucocorticoid excess can lead to impaired osteogenic differentiation and increased bone resorption (Fig. 3a) [54,55]. PTH deficiency may contribute to disturbances in calcium homeostasis, impacting bone mineralization [56]. Accordingly, in osteoporotic conditions, bone homeostasis is disrupted by excessive bone resorption and insufficient bone formation, achieving bone-implant osseointegration more challenging than under normal conditions. To devise targeted interventions in osteoporotic patients, a programmed PEEK surface with a degradable hybrid coating is designed to sequentially regulate osteoimmunomodulation and bone regeneration [57]. By initially releasing interleukin-4 (IL-4) to mitigate acute inflammation, followed by sustained delivery of alendronate and Ca2+ to enhance osteogenesis, suppress osteoclastogenesis, and ultimately improve bone-implant osseointegration under osteoporotic conditions. Similarly, Chen et al. constructed that the biofunctional metal-organic framework (bio-MOF) coating on the Ti implant surface, which led to improved osteointegration in the senescence-induced osteoporotic microenvironment [58]. The novel strategy effectively decomposed excessive ROS, restored mitochondrial dynamics, and reprogrammed senescent bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) into normal BMSCs, ultimately recovering their osteogenic potential.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms underlying bone remodelling imbalance in pathological microenvironment. (a) Overview of age-related changes in the bone marrow microenvironment. In young/healthy marrow, osteoblasts and osteoclasts are balanced via coupling agents such as RANKL, IGF-1, and PDGF-BB. In old/osteoporotic marrow, accumulating ROS and proinflammatory cytokines can create a chronic inflammatory state, finally leading to a bone matrix that becomes thin and porous (osteoporotic) and susceptible to fracture [55]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier Ltd. (b) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone diseases in diabetes mellitus [63]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature.

Furthermore, diabetes mellitus is affected by a partial or complete failure of β-cells of the pancreas combined with low levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), which significantly suppresses the terminal differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts, along with a notable reduction in osteoblastic activity [59,60]. As diabetes progresses, the concurrent presence of hyperglycemia, chronic inflammation, advanced glycation end products, and microangiopathy, collectively exert detrimental effects on both the architecture and biomechanical properties of the skeleton (Fig. 3b) [[61], [62], [63]]. The microvascular complications significantly impair angiogenesis and microcirculatory dysfunction, and impede the necessary nutrient and oxygen delivery to the healing site, thereby affecting osteogenesis and bone-implant osseointegration. Given that vascularization is orchestrated by BMSCs-mediated osteogenic microenvironment, deficiencies in vasculature may be exacerbated during the persistent chronic inflammatory milieu characteristic of diabetes [64,65]. In addition to these impediments, patients living with diabetes mellitus face an elevated risk of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI). This heightened susceptibility is attributed to the complex interplay of factors such as compromised immune function, altered tissue perfusion, and the presence of chronic hyperglycemia, collectively creating an environment conducive to bacterial attachment and biofilm formation [66,67]. Tailoring therapeutic strategies to address both the inflammatory aspects, poor neovascularization, and the specific PJI of diabetes is crucial for promoting effective bone regeneration and mitigating the progression of osteoporosis.

Tightly regulated interactions between the immune and skeletal systems have reaffirmed that aberrant immune responses have a strong potential to govern bone metabolism within the osteogenic microenvironment [68]. As a chronic autoimmune disease, RA is characterized by persistent inflammation, predominantly affecting synovial joints [69]. The immune system's aberrant activation in RA results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which have far-reaching negative effects on the local bone microenvironment via initiating the inflammatory cascade [70,71]. Furthermore, the dysregulated immune responses in RA can instigate the production of autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies [72,73]. These autoantibodies not only contribute to the perpetuation of inflammation but also directly activate osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction [74,75]. Simultaneously, the chronic inflammatory state would alter the immune milieu, contributing to increased osteoclast activity by stimulating the production of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL), a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, by various immune cells [76]. In the context of RA, the differentiation and function of osteoblasts (OB) were inhibited by B cells producing chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 3 and TNF within the bone marrow microenvironment, contributing to bone loss and joint destruction [77]. The intricate interplay between the immune and skeletal systems is underscored by the impact of aberrant immune responses on the osteogenic microenvironment. RA serves as a paradigm, illustrating how chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation disrupt the delicate balance of bone metabolism, eventually leading to peri-implant bone loss and implant loosening [78]. Understanding these complexities is vital for developing targeted therapeutic interventions to mitigate implant-related complications in conditions characterized by immune dysregulation. Otherwise, with the advancement of society and technology, an increasing number of individuals with unhealthy habits such as drinking, smoking, and staying up late are showing varying degrees of inflammatory responses and weakened immunity. As a result, they exhibit reduced osteogenic ability compared to the general population, which draws more attention to the need for developing targeted implants with enhanced bone regeneration capacity.

The development of smart orthopaedic implants targeting the clinical patient-oriented osteogenic microenvironment represents a promising strategy for enhancing bone tissue regeneration. With the introduction of innovative implants integrating advanced materials and technologies, there is an effective achievement of self-adaptive prevention and treatment in response to bone repair under dynamic pathological conditions. Ultimately, we believe that the pursuit of an optimized osteogenic microenvironment in clinical practice will contribute to advancing patient outcomes, promoting faster and more durable bone healing, and improving the overall quality of life for individuals undergoing orthopaedic interventions.

2.2. Regulation of osteogenesis-related signaling pathways

Osteoblasts, primarily derived from BMSCs, stand as crucial cells in fostering the osteogenesis of the bone remodelling process in vivo [79]. The osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs undergoes regulation through multiple signaling pathways, including bone morphogenic proteins/sma and mad (BMPs/Smad) signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway, transforming growth factor (TGF) signaling pathway, wingless/integrated (Wnt) signaling pathway, and others [[80], [81], [82], [83], [84]]. These pathways collectively form a complex and precise regulatory network that plays a pivotal role in controlling osteoblast differentiation, osteogenesis, and bone metabolism. Numerous smart bioactive materials exhibit significant therapeutic potential by modulating osteogenic signaling pathways [85,86]. Consequently, smart implant materials are anticipated to demonstrate exceptional capabilities in promoting osteogenic differentiation, thereby contributing to the advanced healing process of bone tissue.

The BMPs/Smad signaling pathway works via the direct binding of BMPs to receptors on the surface of osteoblasts, initiating the bone formation process through the intracellular Smad signaling system [80]. An illustrative example involves the design of graphene oxide-functionalized methacrylate gelatin (GO/GelMA) scaffolds to enhance the osteogenic capability of BMSCs. These scaffolds enhance the adsorption and release of endogenous BMPs, synergistically cooperating with high activation of the Smad1/5 pathway for advanced osseointegration [87]. Similarly, the silica-coated GO/GelMA nanocomposite scaffolds further promote mineralization and osteogenesis through the released silicon ions triggering the upregulation of BMP2. In a mouse subcutaneous implantation model, the BMSC-loaded GO/GelMA and SiGO/GelMA samples exhibit remarkable increases in bone volumes, compared to the GelMA control group. In addition, the near-infrared (NIR) light irradiation has also been proven to enhance osteogenesis via the BMP2/Smad signaling pathway [88]. Ma et al. successfully designed a novel temperature-controlled nano-HA/graphene oxide/chitosan (nHA/GO/CS) scaffold, which exhibited excellent osteogenic ability of human BMSCs at 42 ± 0.5 °C under NIR irradiation [89]. With the introduction of nHA, the multifunctional scaffold improved the biocompatibility and biological activity, and further enhanced osteogenic differentiation via upregulated the BMP2/Smad signaling pathway. Furthermore, the endogenous proteins are used to modify gold nanorods, which improved biocompatibility and reduced immune response [90]. It is worth noting that modified gold nanorods with NIR laser irradiation may successfully stimulate osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by enhancing the osteogenic signal transduction pathways, including MAPK, Akt, Smad, and β-catenin. Surprisingly, tobacco mosaic virus, turnip yellow mosaic virus, and other plant viruses modified gold nanorods for promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by the elevation of BMP-2 gene expression in an autocrine way, as reported by Metavarayuth et al. (Fig. 4a) [91]. All of these materials, notwithstanding their differences, significantly induce the expression of the BMP2 signaling pathway for advanced osteogenesis.

Fig. 4.

Multi-dimensional analysis of osteogenesis and bone regeneration mechanisms. (a) Proposed pathway in stem cells involves BMP-2 intermediates osteogenesis in which initiated by unique nanoscale topography of virus substrate [91]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (b) Potential molecular signaling pathways by which nano-Mg(OH)2 films on Ti surface influence cell behaviours [94]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier Ltd. (c) Schematic representation of the possible cell division modes in three dimensions on a Wnt3a surface. (d) Representative confocal Z planes with 3D reconstructions and side-view projections of hSSCs undergoing perpendicular cell division at the Wnt3a-platform. The cells were stained with antibodies against APC (cyan) and β-catenin (magenta) and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (yellow). (e) Representative confocal z planes of the base (cells contacting the Wnt3a-platform, middle (10–50 μm from the platform) and top (50–100 μm from the platform) of the WIOTM after immunostaining against CDH13 (cyan) and OPN (magenta) and with DAPI (yellow). (f) Representative micro-CT images of calvarial defects in mice at 8 weeks post-procedure [98]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature.

Previous studies demonstrated that magnesium ions (Mg2+) promotes the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via activation of the MAPK signaling pathway, and increased osteoblast activity and mineralization capacity [83,92]. The smart hydrogel delivery system, for example, incorporated a rationally designed T4 lysozyme mutant (T4M) with cross-linked bioactive ions to mediate the localized delivery and synergistic release of Mg2+ and zinc ions (Zn2+), which promoted osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and bone regeneration through significantly increasing the expression of MAPK pathway-related genes [93]. Moreover, Yao et al. developed two bioactive nano-Mg(OH)2 films on Ti surfaces using hydrothermal treatment [94]. As shown in Fig. 4b, the Mg(OH)2 films, as a nano-sheet-like structure, can release Mg2+ and create a weakly alkaline microenvironment surrounding the implant, which lead to improved osteogenesis via extracellular matrix (ECM) receptor interaction, focal adhesion, and promotion of BMP-4 expression by activating the classic TGF-β signal pathway.

The Wnt signaling pathway is intricately involved in the regulation of bone homeostasis, and bispecific Wnt mimetics such as 18R5-DKK1c have demonstrated the ability to stimulate bone repair and remodelling [81,95]. Recent studies have demonstrated that three-dimensional (3D)-printed Mg-1Ca/polycaprolactone (PCL) composite scaffolds with precisely controlled macro- and microstructures significantly promote new bone formation and effectively repair bone defects [96]. These scaffolds achieve their osteogenic effects by stably releasing Mg2+ ions, which facilitate BMSCs adhesion and proliferation, and by activating osteogenic differentiation through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The functionalized methacrylate hyaluronic acid hydrogels containing the Foxy5 peptide, a noncanonical Wnt5a mimic, stimulate the osteogenic differentiation of human skeletal stem cells (hSSCs) by not only activating the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway involving RhoA-ROCKs but also boosting intracellular calcium levels [97]. In addition, Okuchi et al. covalently bound Wnt3a onto microbeads and an aldehyde-modified glass platform (Wnt3a-platform) in a 3D environment of collagen type 1 gel, where BMSCs were co-cultured and subsequently formed an organized 3D Wnt-induced human osteogenic tissue model (WIOTM) [98]. Then, they designed a biodegradable PCL polymer film bandage to deliver the WIOTM (WIOTM-bandage) to integrate and contribute to bone repair. The localized application of Wnt3a directs the asymmetric cell division of BMSCs, resulting in the generation of two distinct populations: Wnt3a-distal cells, characterized by an enrichment of early osteogenic differentiation genes, and Wnt3a-proximal cells, exhibiting elevated levels of β-catenin, aPKCζ (a cell polarity protein), and various stem cell markers. This orchestrated division serves to maintain the quantity of human stem and osteogenic cells at the injury site. Moreover, it significantly augments the activation of the β-catenin pathway, thereby expediting endogenous osteogenesis and efficient bone repair (Fig. 4c–f). Therefore, the mechanism by which the Wnt signaling pathway regulates osteogenesis has been revealed and represents a viable strategy of biomaterials functionalized with related signaling proteins to contribute to bone repair.

The different signaling pathways play critical roles in the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and osteogenesis, thereby, smart implants embedding biomolecules (e.g., signaling pathway proteins, growth factors, etc.) or other biodegradable ingredients provide novel insights into the treatment of bone defect regeneration. However, novel biomaterials lead to many challenges such as biocompatibility, biological toxicity, immunogenicity of bioactive molecules, and other diseases induced by intracellular signaling activating mutations, etc. These problems limit the application and clinical translation of the innovatively smart implants, but the biofunctionalization of biomaterials may offer future effective therapeutic approaches for bone tissue regeneration and repair.

2.3. Dynamic balance between osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis

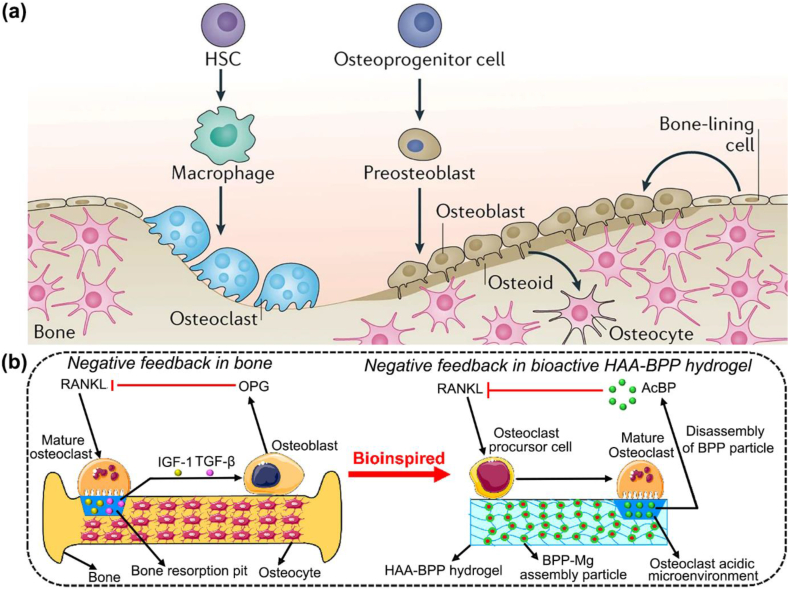

The dynamic maintenance of bone structure, i.e., bone homeostasis, involves a delicate equilibrium between bone formation by osteoblasts and resorption by osteoclasts. Osteoclasts, originating from the hematopoietic lineage of monocytes or macrophages, predominantly govern the resorption of bone matrix and mineralized tissue through alterations in the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK), RANKL, and osteoprotegerin (OPG) axis. This regulatory mechanism plays a crucial role in osteogenesis and bone homeostasis (Fig. 5a) [99]. Simultaneously, the release of TGF-β and IGF1 follows the bone resorption process, triggering osteoblast differentiation and the formation of a new bone matrix [100]. Therefore, the reasonable regulation of resorptive osteoclast activity to maintain bone homeostasis stands as a significant strategy for promoting osteogenesis and bone defect repair.

Fig. 5.

Mechanisms of bone homeostasis and biomimetic regulation of osteoclast activity. (a) Schematic illustration of the bone homeostasis achieved through the balance between the activity of osteoblast lineage cells and osteoclast lineage cells. Osteoblast lineage cells such as the osteoid secrete HA and calcium to promote bone mineralization and formation of osteocytes. Meanwhile, osteoclast lineage cells resorb the bone tissue. HSC is the hematopoietic stem cell [99]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature. (b) Schematic flow of the native negative feedback regulation of osteoclasts in bone and the biomimetic emulation of the negative feedback regulation of osteoclasts by a bisphosphonate-based nanocomposite hyaluronic acid (HAA-BPP) hydrogel. Osteoclastic activities degrade the HAA-BPP hydrogel, thereby triggering the release of BPP, which in turn inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastic maturation [103]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier Ltd.

To inhibit osteoclast differentiation and osteoclastic activity for treating bone tissue regeneration and osteoporosis is an effective strategy. The Mn-contained β-tricalcium phosphate (Mn-TCP) bioceramics are successfully fabricated to accelerate bone tissue regeneration in osteoporotic rats via promoting osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts and decreasing the formation and resorptive function of osteoclasts [101]. The related detailed mechanism is that the released Mn2+ ions scavenge ROS by activating nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 to increase antioxidant enzymes, ultimately decreasing the number of osteoclasts. Similarly, He et al. revealed that nanoporous titanium implant surfaces, such as the micropitted/nanotubular topography and micropitted topography, significantly accelerating early bone formation and osseointegration around the implant in vivo [102]. The nanoporous surface could remarkably inhibit the formation of osteoclasts by significantly downregulating the integrin-mediated β1/FAKpY397/MAPK pathway, thus relieving the inhibition of osteoclasts on osteogenesis via altering the secretion of macrophage cytokine profiles and clastokines. In addition, the smart stimuli-responsive biomaterial scaffolds provide valuable inspiration for facilitating osteogenesis and bone regeneration. Li et al. designed the biomimetic hyaluronic acid nanocomposite hydrogel by coordination bonds with the antiosteoclastic drugs bisphosphonates [103]. Under the acidic environment created by mature osteoclasts secreting abundant amounts of hydrogen ions into the subosteoclast compartment [104], the biomimetic hydrogel exhibited the expedited release of loaded bisphosphonates and then the osteoclast maturation. However, this hydrogel only releases basal levels of bisphosphonates in the presence of preosteoclasts, whereas it releases a significant number of bisphosphonates when mature osteoclasts are present. This conclusion may help to selectively inhibit mature osteoclasts through biomimetic negative feedback regulation, which would improve osteogenesis and bone repair in vivo.

Under bone homeostatic conditions, osteoclastic activity is regulated by negative feedback. The activity of mature osteoclasts is increased with increasing RANKL exposure, resulting in the release of matrix-bound factors such as IGF1 and TGF-β, subsequently triggering the recruitment of osteoblasts and synthesis of OPG, which can inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast maturation (Fig. 5b) [99,103,105]. The nanoparticulate mineralized collagen glycosaminoglycan scaffolds can induce osteogenic differentiation via through activation of the canonical BMP signaling pathway. Then, the special scaffolds are integrated with adenovirus-mediated delivery of OPG (AdOPG), an endogenous anti-osteoclastogenic decoy receptor, uncoupling osteogenic and osteoclastogenic differentiation that inhabit osteoclast resorptive activity to enhance osteogenesis [106]. This reveals that the regulation of osteoclast resorptive activity while maintaining the positive paracrine effects on osteogenic differentiation is a new avenue for the development of osteogenic biomaterials. When cytokines are activated at the implant interface, osteoclasts play a crucial part in osseointegration, whereas any suppression of osteoclastogenesis may delay bone repair [107]. Nowadays, CaP-based materials, such as calcium phosphate cement (CPC), dicalcium phosphate (DCP) bioceramic scaffolds, etc., have been demonstrated that could modulate osteoclast-mediated osseointegration efficiently [108]. The CPC scaffolds with high Ca/P ratio can significantly enhance osteoclastogenesis and activity via increasing affinity between RANKL and RANK, meanwhile promoting the secretion of endogenous TGF-β1 to recruit BMSCs and significantly ameliorate osseointegration. This perspective diverges from the conventional notion that inhibiting osteoclastogenesis promotes bone formation. Instead, it establishes a connection between osteoclasts and osteoblasts, introducing a novel strategy to promote osteogenesis and advance bone repair.

Furthermore, the few-layered Nb2C (MXene) is also recently demonstrated to effectively inhibit osteoclastogenesis by its ROS adsorption ability [109,110]. Other researchers found that selenoprotein W acts as an osteoclastogenic stimulator and engages in negative feedback to suppress osteoclast differentiation through downregulating RANKL/RANK/TNF receptor-associated factor 6/p38 signaling [111]. In addition, the antiosteoclastic nano-biomaterials or specific signaling molecules may be more efficient in reducing osteoclastogenesis and triggering osteogenesis via local nanoparticle drug delivery systems. The preceding multifarious biomaterials give innovative methods for promoting osteogenesis by reducing osteoclast differentiation and maturation. Nevertheless, to achieve long-term osteogenesis, future emphasis should be placed on the moderate regulation of osteoclast activity and its close interaction with osteoblasts.

2.4. Regulation of autophagic flux in osteogenesis

Autophagy, a major catabolic process in eukaryotic cells that degrades and recycles damaged macromolecules and organelles, contributes to mediating the survival and functioning of osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts, which plays an essential role in bone homeostasis [112,113]. In addition, the levels of autophagy are enhanced during osteoblast differentiation of BMSCs through AMPK signaling pathways [113], and autophagic vacuoles could be used as vehicles to secrete apatite crystals during the mineralization process [114]. This also reveals the link between autophagy and osteogenesis, which provided a new strategy to improve the treatment of nonunion fractures. According to the report of Zhang et al., the combination therapy using BMSCs in hydrogels with negative pressure greatly boosted osteoblast differentiation and bone regeneration by identifying a novel AMPK- unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1)-autophagy axis [115].

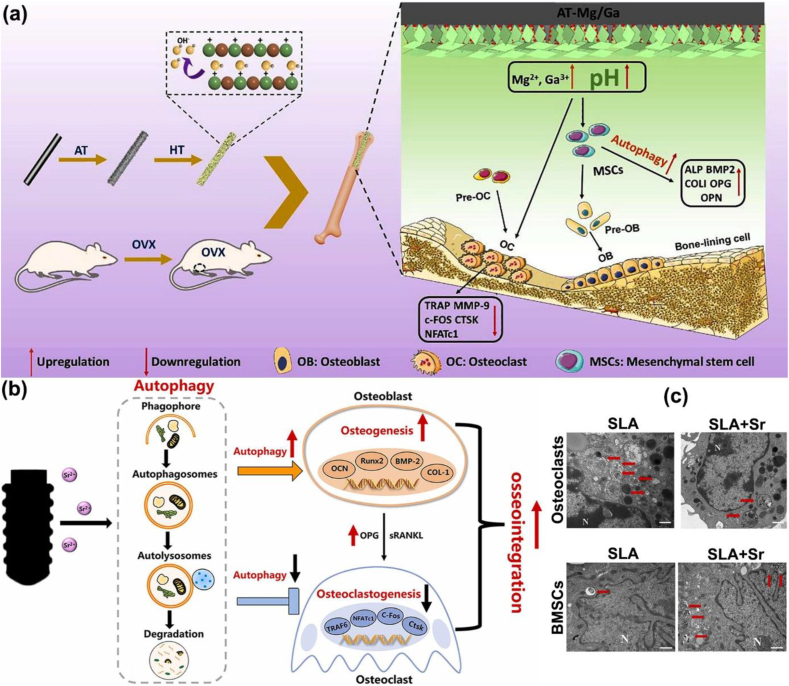

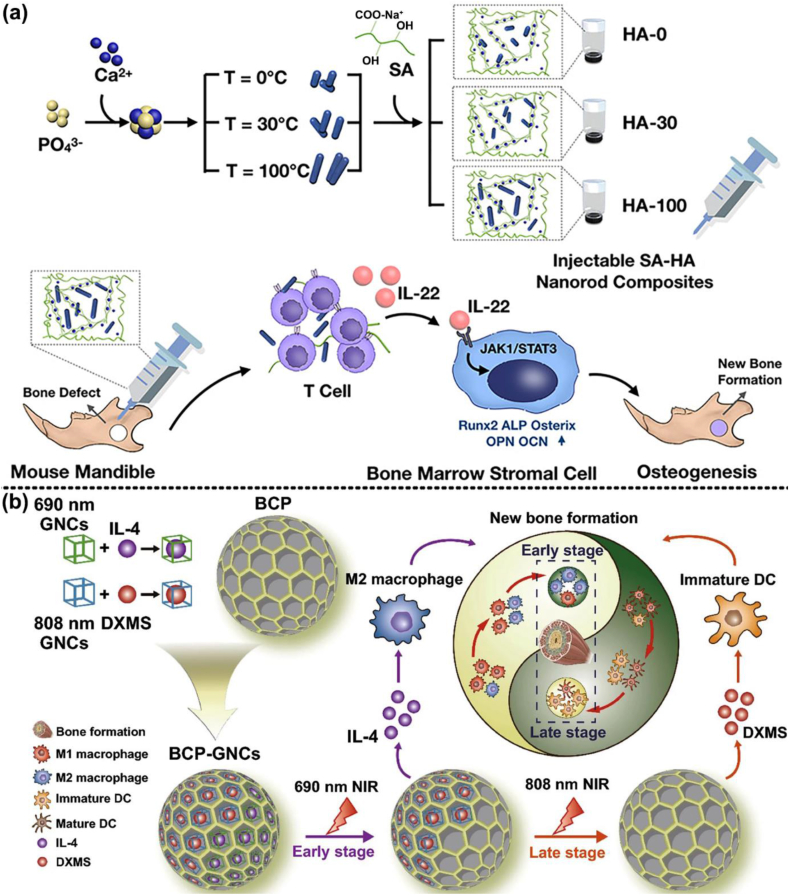

As a novel bioactive inorganic material, calcium silicate (Ca2SiO4) nanoparticles (NPs) have been identified as a potential candidate for bone repair [116], which could up-regulate autophagy by activating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/ULK1 and subsequently triggering the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to boost the differentiation and mineralization of osteoblasts [117]. Previous studies have illustrated that the alkaline microenvironment around the repair and regeneration of bone tissue induces autophagy as a cytoprotective mechanism and decreases the activity of osteoclasts to promote osteogenesis [118,119]. Chen etc. successfully fabricated the coating with Mg-Ga layered double oxide nanosheets, which was in situ grown on the surfaces of alkali-heat-treated titanium (AT-Mg/Ga) implants (Fig. 6a) [120]. To our surprise is that the novel coating displayed good stability and generated an appropriate alkaline microenvironment (about pH 8.5) over the long term due to the Mg2+ and Ga3+. Under the resulting weak alkaline environment, significantly improved the autophagic level by regulating AMPK pathways via P2Y receptors and activating ULK1 to trigger mTOR signaling pathways, thus promoting the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and suppressing osteoclastogenesis to achieve interfacial osseointegration.

Fig. 6.

Mechanisms of autophagic regulation in bone remodelling. (a) Schematic illustration of the AT-Mg/Ga implants that promoted autophagic activity that upregulated the osteogenic differentiation level of BMSCs and suppressed osteoclastogenesis to achieve interfacial osseointegration. (HT: hydrothermal treatment; OVX: ovariectomy) [120]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (b) Schematic diagram of the regulatory role of autophagy in osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis stimulated by Sr-doped titanium implant. (c) TEM images of the autophagosomes in osteoclast and BMSCs seeded on the SLA and SLA + Sr surface for 24 h (N: cell nucleus; red arrow: autophagosome) [122]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Furthermore, the titanium nanotopography has been reported to regulate cytoplasmic Yes-associated protein (YAP, an effector protein involved in the degradation of β-catenin) degradation and activate the β-catenin pathway to induce osteoblast autophagy, which can promote osteogenic differentiation and mineralization [121]. Wang etc. fabricated Sr-doped micro/nano rough titanium implant surface by sandblasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) and following hydrothermal treatments (SLA + Sr) that endowed implants with the ability to modulate autophagy to promote osteogenesis and osseointegration (Fig. 6b) [122]. The distinctive mechanism underlying the Sr-incorporated micro/nano-rough titanium implant surface involves the synergistic effects of nano-morphology and Sr2+, leading to the upregulation of osteogenesis and autophagy through Akt-mTOR-dependent signaling pathways. Simultaneously, this modification enhances the secretion of OPG by osteoblasts, thereby suppressed osteoclast autophagy and osteoclastogenesis via influencing the RANK/RANKL/OPG axis (Fig. 6c). Concurrently, the innovative modified Ti significantly accelerated bone tissue regeneration and improved periprosthetic osseointegration. This interaction between autophagy and osteogensis signifies a promising avenue for smart implant design, where the intricate cellular reprogramming processes hold the key to enhance osseointegration and long-term implant success.

Nowadays, researchers also confirm that the upconversion optogenetic nanosystem could up-regulate autophagy via converting tissue-penetrative NIR light into local visible blue light [123], which provides the possibility of modulating autophagy in combination with photodynamic therapy to promote osteogenesis. Hence, the regulation of autophagy is a crucial pathway for promoting osteogenesis, especially the role of an alkaline environment, which reveals a new horizon for designing appropriate implant materials to enhance their osseointegration in the future translational medicine field.

2.5. Osteogenic activity of the surface topographies of implants

For smart bone implants, the optimization of topography and morphological characteristics of synthetic biomaterial surfaces is robustly demonstrated as an effective approach to enhance their biological performance, offering novel insight and potential mechanism for bone tissue regeneration and repair. Surface modifications have been employed to establish favourable biological interfaces, augmenting the interfacial bioactivity of bone-implanted biomaterials [124]. Herein, we systematically summarize and discuss the diverse osteogenic surface properties of biomaterials along with their underlying mechanisms.

Micro/nano-textured topography structures show favourable roughness, hydrophilicity, and mechanical interlocking ability, which endow the biomaterials capable of guiding cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [125]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that micro/nanonet-textured hierarchical titanium topography enhanced the spreading areas of BMSCs on its surface and boosted exosomes synthesis and transport by upregulating RAB27B and sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3 gene expression [126]. Exosomes released by BMSCs have been demonstrated in vivo and in vitro to promote BMSC adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation, as well as to allow enhanced bone regeneration by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway or suppressing the plexin B1/RhoA (ras homolog gene family, member A)/ROCK (Rho-associated kinase) pathway [127,128]. Therefore, this reveals a potential mechanism of the implant surface topographies that can regulate the function of exosomes and thereby promote BMSCs osteogenesis differentiation, which also expands new horizon for the development of bioactive smart materials. The nanotopographical titanium plates are produced through alkali heat treatment, which can stimulate human BMSCs (hBMSCs) osteogenic differentiation and cause the release of pro-osteogenesis small extracellular vesicles (sEVs, Ti4-21-sEVs) (Fig. 7a) [129]. Researchers discover that the sEVs secreted from hBMSCs cultured on Ti4 could be utilized to decorate 3D-printed polyether ether ketone (PEEK) scaffolds with polydopamine (PDA), and these scaffolds demonstrated enhanced osteogenic activity in a time-dependent manner without adding cells or other biochemical factors. Simultaneously, the engineered Ti4-21-sEVs significantly promoted osteogenesis in vivo and in vitro by delivering miRNAs (e.g., miR-497-5p and miR-210-3p) with osteogenic signaling pathways (Fig. 7b and c). Similarly, Zhai et al. discovered that exosomes extracted from hBMSCs at different stages of osteogenic pre-differentiation were used to modify 3D-printed Ti alloy scaffolds, enhancing osteogenesis and bone tissue regeneration by activating the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways [130]. Therefore, the bioscaffolds bind to osteogenic exosomes, especially the exosomes induced by nanotopological surfaces, which provides a novel cell-free osteogenesis method for bone repair.

Fig. 7.

Osteogenic activity driven by the surface topographies of the implant. (a) Schematic of nanotopography regulation of mesenchymal stem cell sEVs that promote osteogenesis and 3D-printed PEEK scaffolds decorated with sEVs for bone regeneration; Osteogenesis indicators including OPN, RUNX2, ALP, and OCN were detected by RT-qPCR after incubation with 50 μg/mL Ti-21-sEV and Ti4-21-sEV for (b) 14 days and (c) 21 days, and untreated cells denoted as a control group. (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001) [129]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (d) Representative false colored scanning electron micrographs highlighting phenotypic differences between BMSCs cultured on (i) flat substrates (control) and (ii) micropatterned substrates. (e) Representative false-colored FIB/SEM image of BMSCs cultured on 5 × 5 substrate. Micropillars are colored red, with nuclei colored blue [131]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (f) Schematic illustration of the influence of contact-guidance-induced nuclear deformation on bone regeneration. Microtopography engineering was used to create the micropillar implants fabricated using methacrylated poly(octamethylene citrate) (mPOC) [132]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

The micron-size micropillar arrays are also prepared by ultraviolet nanoimprint lithography and exhibit excellent osteogenic capacity of BMSCs, especially on micropillars with 5 μm width/spacing and height [131]. This reveals new insight into promoting osteogenesis by microscale structures, which modulate nuclear deformation caused by myosin-II-generated tension on the actin cytoskeleton and subsequently alter chromatin organization and gene expression (Fig. 7d and e). More importantly, Wang et al. innovatively revealed that the micropillar-induced nuclear deformation could facilitate bone regeneration via chromatin engineering method, as shown in Fig. 7f [132]. The methacrylated poly(octamethylene citrate) micropillars profoundly influenced nuclear architecture, lamin A/C multimerization, and chromatin reprogramming through contact-guidance-induced nuclear constriction. These chromatin conformation changes collectively facilitate osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs and bone tissue regeneration in mice with critical-size cranial defects. Similarly, titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanotube arrays with manganese-containing bioglass also exhibit higher bone formation and osseointegration capacity [133]. Moreover, Bai et al. fabricated TiO2 nanotube arrays with different diameters on titanium surfaces that exhibited excellent osteogenesis ability [134]. The nanotube arrays tends to induce the formation of clot made of thin fibres via coagulation protein adsorption, and subsequently regulate a favourable osteoimmunomodulatory environment with the release of growth factors, which can significantly accelerate the formation of bone healing hematoma, leading to better bone regeneration and osseointegration.

Moreover, the flower-like nanostructures were successfully constructed in situ on biodegradable calcium silicate (CaSiO3) bioceramics via hydrothermal treatment, which exhibited strong abilities to promote bone regeneration in vivo [135]. Compared with CaSiO3 bioceramics, the novel nanostructures significantly provide more sites for BMSCs adhesion and proliferation, which further activate the FAK/p38 signaling pathway to enhance osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. In addition, biological synthesis of the micro/nanostructures on bioceramics such as the mineralization in bacteria, is also a novel strategy to fabricate the advanced biomedical materials for bone tissue regeneration [136]. The microbially catalyzed micro/nanostructures can stimulate adhesion, spreading, and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by upregulating integrin alpha-2 and the Wnt signaling pathway to significantly enhance in vitro and in vivo osteogenesis.

Therefore, the achievement of multifarious micro/nanotopographical structures of bone implants through surface modification represent a novel and effective approach to promoting osteogenesis. This strategy can not only efficiently enhance the adhesion of BMSCs on the interface between bone and implants, but also actively stimulate the secretion of osteoinductive factors that subsequently activate corresponding osteogenic signaling pathways and then contribute to improved osseointegration. The diverse topographical surfaces offer valuable inspiration and novel insights into the design and production of bioactive materials for bone tissue regeneration and repair. In clinical practice, micro/nanotopographical surface modifications have been successfully applied to orthopaedic implants to enhance osseointegration and long-term stability, showing excellent prospects for clinical translation [137]. Notably, biodegradable magnesium-based implants with bioactive coatings have demonstrated promising clinical outcomes. For example, Mg-Nd-Zn-Zr alloy screws with calcium phosphate (Ca-P) coatings have demonstrated excellent osteoinductivity and biocompatibility in preliminary clinical trials for treating medial malleolar fractures, as evidenced by satisfactory fracture healing, gradual in vivo degradation, and improved postoperative functional recovery without severe complications [138]. However, in the context of these excellent biomaterial clinical applications, attention should also be given to the mechanical properties of micro/nanotopographical structures and the potential generation of wear particles, which may induce complications such as bone resorption and related osteolytic effects.

3. Bifunctional platform-based smart bone implants

Although exceptional osteogenesis and regenerative effects can be obtained with different biomaterials, several challenges remain to be addressed. For example, while the rough surface structure or nanotopography of bone implants plays a critical role in enhancing BMSCs adhesion and osteogenic differentiation, it may also unintentionally promote microbial attachment and biofilm formation on implant surfaces [139,140]. Additionally, a favourable osteoimmunomodulatory microenvironment can accelerate the transition from the initial inflammatory response to bone remodelling phase, highlighting the crucial role of immune modulation in promoting osteogenesis [19]. Finally, neovascularization plays a pivotal role in osteogenesis by ensuring adequate oxygen and nutrient supply to the regenerating bone tissue, thereby creating a microenvironment conducive to the recruitment of osteoprogenitor cells and facilitating bone formation and remodelling [141]. However, the synergistic interplay between osteogenesis and other critical functions, such as antibacterial, immunomodulatory, or angiogenesis, remains insufficiently explored in the design of osteogenic biomaterials. Therefore, bifunctional platform-based smart implants should be designed to integrate both osteogenesis with one of these additional functions, addressing multiple aspects of bone repair and regeneration simultaneously. In the following section, we summarize and illustrate various strategies for achieving this synergistic effect of bifunctionality in smart bone implants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bifunctional platform-based smart implants.

| Biomaterial type | Smart composition | Advantage |

Model | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Special | ||||

| Antibacterial capacity and osteogenesis | |||||

| 3D hybrid scaffold | TDN, clindamycin | 1) destroy bacterial membranes and biofilms, 2) increase adhesion, spreading, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, 3) enhance the expression of osteogenesis-related genes and proteins, 4) reinforce osteoinductivity and osseointegration |

sustained release, enhance drug sensitivity | MRSA, rat BMSCs | [147] |

| 3D porous PEEK scaffold | Li+, antimicrobial peptide, porous structure | penetrate the bacterial cell wall | S. aureus, rat BMSCs | [149] | |

| surface modified Ti | ZnO/Zn3(PO4)2 hybrid nanostructures | physically rupture the bacterial membranes, release Zn2+, and generate ROS | S. aureus, E. coli, human BMSCs | [159] | |

| surface modified Ti | Al2O3-wrapped nanorod patterned array | mechano-puncture, | S. aureus, rat BMSCs | [151] | |

| surface modified Ti | PDA, Zn2+, nanorod arrays | physical puncture bacteria, enhance Fenton-like reactions, scavenge ROS, | S. aureus, E. coli, MC3T3-E1 cells | [157] | |

| Zn-Ag alloy implants | Zn2+, Ag+ | biodegradable, autolysis-related pathways, anti-osteolysis | S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, MRSA, MRSA 287, MC3T3-K cells, BMDMs | [161] | |

| surface modified Ti6Al4V | HA/MoS2, electrons transfer | disrupt redox balance, upregulate Ca2+ level, alter mitochondrial membrane | S. aureus, E. coli, MRSA, P. aeruginosa, rat BMSCs | [164] | |

| surface modified anodized Ti | triboelectric nanogenerator, negatively charged surface, electrical stimuli | reduce bacterial adhesion | S. aureus, E. coli, MC3T3-E1 cells | [167] | |

| 3D-printed scaffold | BPs, Zn2+, HA, photothermal effects | gradually release, Increase bacterial intracellular ATP and ROS levels, protein leakage, | S. aureus, E. coli, human BMSCs | [176] | |

| surface modified magnesium alloy | FeOOH nanosheets, Mg2+, photocatalytic and photothermal effects | corrosion resistance, sustained release | S. aureus, MC3T3-E1 cells | [177] | |

| surface modified Ti screw | photosonotherapy, ROS, | electron−hole separation, oxygen deficiency, | S. aureus, Porphyromanus gingivalis, MC3T3-E1 cells | [180] | |

| surfaced modified Ti | S-nitrosoglutathione, NO, photothermal therapy | controlling release of NO | S. aureus, E. coli, rat osteoblasts | [185] | |

| surface modified Ti | Mg/Zn-MOF74, Zn2+, Mg2+, | create alkaline microenvironment, anti-inflammatory | S. aureus, E. coli, rat osteoblasts, RAW264.7 cells | [7] | |

| 3D printed bioactive glass scaffold | FeSAC, •OH, hyperthermia | Fenton catalytic activity, destruct osteosarcoma | S. aureus, E. coli, human BMSCs, saos-2 cells | [191] | |

| surface modified Ti | LUT, Ca2+, PO43−, thermotherapy | acidic environment releasing | S. aureus, rat osteoblasts | [193] | |

| Immunomodulatory activity and osteogenesis | |||||

| injectable silk scaffolds | sitagliptin | 1) induce M2 phenotype macrophages polarization 2) ameliorate inflammatory microenvironment 3) promote osteointegration |

recruit M2 macrophages | rat osteoblasts, rat BMDMs | [217] |

| 3D-bioprinted scaffold | BMP-4 | sustained release, secrete BMP-2 | rat BMSCs, RAW264.7 cells | [220] | |

| surface modified Ti | honeycomb-like TiO2 structures | upregulate RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway | rat BMSCs, RAW264.7 cells | [33] | |

| surface modified Ti | Sr-doped Na2TiO3 nanorods arrays, Na+, Sr2+ | long-term release, paracrine of TGF-β1 and BMP2, enhance adhesion and filopodia formation of macrophage | MC3T3-E1 cells, RAW264.7 cells | [223] | |

| CS bioceramics | CaSiO3 | upregulate macrophage-derived OSM, upregulate ERK1/2 and JAK3 pathways | mouse BMDMs, mouse BMSCs | [226] | |

| tricalcium silicate cements | tricalcium silicate | secret BMP2, TGF- β1, and VEGF | mouse BMDMs, mouse BMSCs | [227] | |

| nanocomposite membrane | BaTiO3 | endogenous negative electrical microenvironment, inhibit PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | human monocytic THP-1 cells, human BMSCs | [232] | |

| nanocomposite membrane | CoFe2O4, P(VDF-TrFE), RGD-integrin | magnetoelectric microenvironment, activate PI3K/Akt signaling | rat BMSCs, RAW264.7 cells | [239, 242] | |

| delivery composite hydrogel | blood clot, BMP-2, hyperthermia effects | recruit macrophages, upregulate osteogenic protein expression | MC3T3-E1 cells, Balb/c mice cranial defect model | [245] | |

| surface modified Ti | PDA@HA nanorod-like array, photo-thermal therapy | ROS scavenging, sequential immunomodulation, release HSP 70, activate PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | mouse BMDMs, mouse BMSCs, RAW264.7 cells | [250] | |

| Angiogenesis and osteogenesis | |||||

| bioceramics | micro-nano-hybrid HAp and Sr2+ | 1) enhanced expression of osteogenic and angiogenic genes 2) improved expression of angiogenic factors 3) enhance vascularized bone regeneration |

micro-nanostructured surface promotes gene expression of osteogenic and angiogenic factors | rat BMSCs, | [275] |

| surface modified Ti6Al4V | magnesium-coated porous Ti6Al4V scaffold | improve cell proliferation, adhesion, ECM mineralization and ALP activity | MC3T3-E1 cells, HUVECs cells | [278] | |

| ion-Based Microspheres | Mg2+ and Si4+ | precise and controlled release of ions, massive collagen secretion | rat BMSCs, Ex vivo cam model (fertilized chicken embryos) | [281] | |

| 3D printed bioactive glass scaffolds | Nb2C MXene, calcium and phosphate released | biodegrades, photothermal ablation of osteosarcoma | Saos-2 cells (human osteosarcoma tumor cells), hBMSCs, HUVECs | [284] | |

| MgSnZnNa alloy | Na+, Mg2+ | co-release of Na and Mg ions | MC3T3-E1 cells, mouse adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells | [286] | |

| nanocomposite scaffolds | umbilical MSCs exosomes, HA-Gel, nanohydroxyapatite | exosomal miR-21 suppress the NOTCH1/DLL4 signal pathway, | umbilical MSCs, HEK293 cells, EPCs, and rat BMSCs | [300] | |

| β-TCP composite scaffolds | modularized sEVs | target ECs, BMSCs, and pre-OCs, inhibit OC maturation | mouse BMDMs, mouse BMSCs, HUVECs | [304] | |

| 3D printed PCL composite scaffolds | wesselsite [SrCuSi4O10] nanosheets, photothermal effect, Sr, Cu, and Si ions | thermal ablation of deep-seated osteosarcoma, | rat BMSCs, HUVECs, Saos-2 cells | [310] | |

| nanoparticle-hydrogel composite | mild magnetocaloric effect, cobalt ions | facilitated the expression of heat shock protein (HSP) 90, activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, | rat BMSCs, HUVECs | [311] | |

| nanofibrous scaffold | DMOG, BFP, simulate bone microenvironment | Activate PI3K/PKB/HIF-1α pathway, dual-drug delivery | rat BMSCs, HUVECs | [312] | |

| 3D printed enzyme-functionalized scaffold | Gox, CaP@CAT NSs, Ca2+ and PO43− ions | induce hypoxic microenvironment, alleviate the hyperglycemia environment | rat BMSCs, HUVECs, RAW264.7 cells | [322] | |

3.1. Synergistic interaction between osteogenesis and antibacterial/bactericidal capacity

Biomedical implant-associated infection is one of the most frequent and problematic complications related to the use of biomaterials, and the common routes of infection are intraoperative and hematogenous spread [67,142]. The rough structure of the biomaterial formed by surface modification not only improves BMSCs adhesion but also attracts bacteria at the implant-tissue interface, which can finally produce a biofilm that shields the bacteria and facilitates infection persistence [139]. As the concept of “race for the surface” is introduced, bacteria and host tissue cells compete for colonization on the surface of implanted materials, and in turn affects the osseointegration of the implant with the surrounding tissue, resulting in premature implantation failure [143]. Whatever the mechanism is, the design of multifunctional biomaterials to accomplish the antimicrobial effects and simultaneously promote cell affinity and osteointegration is a crucial solution to preventing implant infection.

3.1.1. Antimicrobial agent loaded bioactive implants

As the most traditional antibacterial method, an antibacterial agent combined with novel biomaterial could achieve the purpose of bacteria-killing by releasing the loaded agent into the surrounding tissues and its pharmacological effects [144]. Nowadays, the tetrahedral DNA nanostructure (TDN) are versatile 3D framework consisting of single-stranded DNA molecules, which may deliver medications while regulating their release and prolonging their effective concentration [145,146]. A 3D GelMA hybrid scaffold loaded with TDN and clindamycin complexes is fabricated, which representes exceptional biocompatibility, osteogenic and antibacterial activity, and significantly accelerates the repair of infected bone defects [147]. With the antimicrobial agents diffusing out of the hydrogels, the TDN-clindamycin-loaded scaffold significantly enhances the drug sensitivity of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) to clindamycin via enhancing the affinity between clindamycin and penicillin-binding proteins. Simultaneously, the acidified environment is obviously alleviated by effective infection control, and this in turn enhances the expression of osteogenesis-related proteins, such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP), RUNX family transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), osteocalcin (OCN), and osteopontin (OPN), which also boosts cell competition against bacteria and eventual osteogenesis.

Due to the bacterial resistance to current antibiotics, supramolecular short peptide nanomaterials, such as dipeptides, cyclic peptides, amphiphilic peptides, and self-assembling peptides, have recently gained interest for their potential to combat pathogenic microorganisms [148]. If combined with osteogenic materials, they can provide a promising strategy for simultaneously improving osseointegration and infection prevention. The researchers fabricate a multifunctional PEEK that loads with Lithium ion (Li+) and mussel-inspired antimicrobial peptide on its surface for both ideal implant-bone interface osseointegration and anti-infection effect [149]. The mussel-inspired antimicrobial peptide exhibited outstanding antibacterial properties via penetrating the bacterial cell wall and irreversibly damaging to bacterial membrane, resulting in protein leakage and destruction of adenosine triphosphate synthesis. In addition, the 3D porous structure of PEEK attracts the adhesion and proliferation of BMSCs, and the release of Li+ improves the osteogenic differentiation and osseointegration of stem cells via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Therefore, the antimicrobial peptides or engineered chimeric peptides successfully combined with osteogenic implants also provide a potentially effective therapeutic way to bacterial drug resistance in clinical practice.

3.1.2. Physical bactericidal capacity and osteogenesis

As above the micro/nanostructures have been proven to promote osseointegration by promoting exosome biogenesis and extracellular secretion [126], however, utilizing its property of physically puncturing bacterial membranes can be regarded as a good strategy for antimicrobial therapy. Due to the negligible side effects of physical bactericidal strategies, Mo et al. demonstrate that argon plasma-treated PEEK surfaces with tilted and vertical nanolamellae penetrate and stretch bacteria, leading to their destruction, with tilted structures being more favourable for peri-implant bone regeneration [150]. In addition, Ye et al. confirmed that the top sharpness and shorter Al2O3-wrapped nanorod patterned array can induce mechano-puncture of S. aureus to achieve the effect of sterilization (Fig. 8a and b) [151]. Fortunately, these sharp nanorods do not damage the viability of BMSCs, which is ascribed to the role of the lower Young's modulus and 3D architecture of the ECM of stem cells [152,153], thereby, simultaneously exhibit excellent osseointegration in bacteria-infected rat tibias models. However, due to the different membrane sensitivities of different bacteria to the nanotopography, the physical puncture is not always effective in preventing implant-associated infection [154,155]. Hence, physical sterilization alone does not seem to be a universal way to alleviate the problem of infection, and it is necessary to combine it with other more effective sterilization strategies for achieving higher synergism between anti-infection and bone-promoting. The antibacterial activity of zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs is increasingly being investigated since it induces intracellular ROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction, which can lead to bacterial death and/or inhibition [156]. On the surface of Ti implants, biofunctionalized ZnO/PDA/arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-cysteine nanorod arrays are prepared for balancing the bacteria-osteoblast race [157]. The special nanorods arrays show the capability to selectively physically puncture bacteria, enhance cytocompatibility, and mitigate cell toxicity through the binding of PDA with Zn2+ to scavenge ROS, which also exhibit excellent ability of infection prevention and osseointegration. In addition, the released Zn2+ can inflow into bacteria through Zn importer and enhance intracellular ROS levels via Fenton-like reactions to achieve a bactericidal effect [158]. The rapid degradation and cytotoxicity of ZnO nanorods limit their biomedical applications, but converting them into stable zinc phosphate (Zn3(PO4)2) via hydrothermal treatment can mitigate these issues while maintaining antibacterial properties [159]. This optimized ZnO/Zn3(PO4)2 hybrid nanostructures exhibits potent antibacterial activity by mechanically disrupting bacterial membranes and concurrently enhances osseointegration in a rabbit model of femoral infection (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 8.

Mechanisms of physical bactericidal capacity and osteogenesis by nanorods. (a) Schematic illustration of the antibacterial mechanisms of nanorods with different top sharpness, showing nanorods with flat top to deform cell envelop appearing bacteriostatic, while nanorods with sharp top to penetrate into S. aureus appearing bactericidal. (b) TEM images of ultrafine structures of S. aureus cultured on Al2O3@ZNRes and Al2O3@ZNR1 for 30 min as well as on Al2O3@ZNRl for 2 h (Blue arrow: electron-lucent region, indicating the leakage of intracellular proteins of bacteria) [151]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier Ltd. (c) Schematic illustration of the fabrication procedures for ZnO/Zn3(PO4)2 hybrid nanostructure (Ti-ZnP2) from ZnO nanorods (Ti-ZnO) to achieve a balance between the anti-bacterial and pro-osteogenic properties [159]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH Verlag.

The advantages of antibacterial coatings prepared by surface modification are obvious, but there are still shortcomings, such as a relatively complex coating process, poor adhesion between the coating and the substrate, easy wear of the coating, and poor long-term antibacterial performance [25,29,160]. In view of the infection problems caused by implanting Ti alloys and the lack of antibacterial coatings, researchers began to try to develop new antibacterial alloy implants with antibacterial functions by adjusting the alloy composition. Meanwhile, the emergence of novel alloy-based biomaterials also displays the strong antibacterial properties and excellent osteogenesis for bone tissue regeneration and repair. For example, Qu et al. designed the biodegradable Zn-Ag alloy implants that possessed remarkable effects of antibacterial, anti-osteolysis, and internal fixation for fractures [161]. Only sporadic bacterial adhesion is observed on the surface of the Zn-Ag alloy and the potential mechanism may be suppressed by the bacterial adhesion colonization genes including Alte and Fbe. What's more, the related gene expression of biofilm formation, autolysis-related pathways, and antibiotic resistance pathways are respectively down-regulated, demonstrating effective antibacterial performance under the release of Zn and Ag ions around the implant during degradation. Compared with the Ti6Al4V alloy implant, the inflammatory response that plays an important role in osteoclastic differentiation is not an obvious change during the degradation of Zn-Ag alloy, which displays reinforced resistance to osteolysis and osseointegration advantages. The successful design of new type of alloys can make up for the long-term deficiency of traditional antibacterial drug treatment method and the generation of drug-resistant bacteria, which also provides a new strategy for advanced smart antibacterial implants.

The bacterial resistance and side-effects of antibiotics remain significant challenges for clinicians treating post-implant infections in clinical practice. It is quite essential to develop safe strategies for eliminating germs without using antibiotics, preventing bacterial infections, and concurrently improving osseointegration to deal with the side effects of antibiotics. During respiration and metabolism, bacteria transfer endogenous electrons to extracellular electron acceptors via the cell envelope c-type cytochromes, whereas in cells, electron transfer occurs within the inner membrane of the mitochondria to produce energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate [162,163]. Due to the structure difference between cells and bacteria in terms of transferring electrons, it also provides new therapeutic strategies for implant-associated infection. Fortunately, the HA/MoS2 coated metallic implants are successfully constructed to interfere with energy metabolism between BMSCs and bacteria (Fig. 9a) [164]. With electrons transfer from the adhered bacteria to the coating surface, the metabolism pathway of S. aureus is altered from aerobic to anaerobic respiration, which induces the disruption of redox balance and then bacterial death. Meanwhile, the coating also promotes the osteoblastic differentiation of BMSCs by altering the potentials of the cell membrane and mitochondrial membrane.

Fig. 9.

Strategies for anti-infection and promotion of osseointegration mediated by biomimetic electrical signals. (a) Electrons extracting from bacteria to HA/MoS2-Ti6Al4V (Ti6) lead to the metabolism pathway changes (left), and the potential of HA/MoS2-Ti6 leads to the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs due to upregulated Ca2+ level (right) [164]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (b) Energy harvesting points of the human body and the structure of triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) for energizing implant with anti-biofilm and osteogenesis promotion activity. (c) Surface microstructure of the friction layers and general appearance of TENG. (d) Assumed principle of biofilm formation inhibition and promotion of osteogenic differentiation [167]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

As mentioned earlier, the positive charge is conducive to the destruction of the bacterial cell wall and cell membrane, similarly, the implant surface with steady and long-term negative charge could effectively inhibit bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation by the electrostatic repulsive force due to the bacterial surface also endowing negative charge [165,166]. Shi et al. innovatively present a self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator to enhance the antimicrobial and osteogenesis properties of implants, which can harvest and transfer mechanical energy from daily human exercise to electrical energy for producing and accumulating numerous negative charge on the surface of anodized Ti implant (Fig. 9b–d) [167]. The constant generation of electric charge on the surface of implants not only reduces the bacterial adhesion but also disrupts the formation of biofilms through synergizing with electrolysis products such as oxidizing radicals. For osteoblasts, the negatively charged biomaterial surfaces can remarkably promote preosteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, which may be ascribed to the slightly alkaline environment caused by the increasing pH level around the cathode [168]. In addition, the charged implant surfaces can also induce mineralization from media with mineral ions and recruit the osteogenesis-related cells to accelerate bone healing, that is, the negative potential surface (or film) utilizes galvanotaxis of BMSCs to recruit cells and the positive one attracts electronegative fibronectin to promote cell adhesion [169,170]. These strategies further demonstrates that the biomimetic electrical signals endow the implant with excellent tissue healing function.

3.1.3. External stimuli-mediated bactericidal capacity and osteogenesis