Abstract

5-Formylcytosine (f5C) modification is present in human mitochondrial methionine tRNA (mt-tRNAMet) and cytosolic leucine tRNA (ct-tRNALeu), with their formation mediated by NSUN3 and ALKBH1. f5C has also been detected in mRNA of yeast and human cells, but its transcriptome-wide distribution in mammals has not been studied. Here we report f5C-seq, a quantitative sequencing method to map f5C transcriptome-wide in HeLa and mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). We show that f5C in RNA can be reduced to dihydrouracil (DHU) by pic-borane, and DHU can be exclusively read as T during reverse transcription (RT) reaction, allowing the detection and quantification of f5C sites by a unique C-to-T mutation signature. We validated f5C-seq by identifying and quantifying the two known f5C sites in tRNA, in which the f5C modification fractions dropped significantly in ALKBH1-depleted cells. By applying f5C-seq to chromatin-associated RNA (caRNA), we identified several highly modified f5C sites in HeLa and mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC).

Keywords: 5-Formylcytosine, quantitative sequencing, transcriptome-wide, mutation rate, read-through rate

Over 100 naturally occurring RNA modifications have been identified so far, with some of them playing various roles in gene expression regulation1–3. As the most abundant internal modification in eukaryotic mRNA, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is dynamically regulated and involved in numerous aspects of mRNA metabolism, such as alternative splicing4, nuclear export5, stability6, translation7,8 and decay9. In recent years, studies on transcriptome-wide sequencing of other mRNA modifications have also been emerging. The reported sequencing methods can be grouped as: (1) Antibody-based MeRIP-seq for m6A4, m1A10–13, ac4C14,15, m5C16 and hm5C17. These methods rely on antibody-based enrichment but could neither achieve base precision nor reveal absolute modification fraction. (2) Reverse transcription (RT) stop-based methods such as CMC-based pseudouridine sequencing18 and low dNTP-based 2′-O-Me sequencing19. While these methods can detect modification sites at base resolution, they usually have high false-positive rates since RT stop signatures could be generated non-specifically20. (3) RT mutation-based approaches, such as methods to map m6A21–24, m7G25–27 and m1A28 that generate mutation signatures at modified sites in order to achieve single base resolution with low background. (4) RT deletion-based approaches, such as BS-Induced quantitative pseudouridine sequencing29,30. Another consideration in RNA modification is the modification stoichiometry at each site. The modification fraction is a biological parameter that is directly related to the modification dynamics and their regulatory functions.

5-Methylcytosine (5mC), 5-hydroxylmethylcytosine (5hmC), and 5-formylcytosine (5fC) are DNA modifications that are important intermediates in an active DNA 5mC demethylation pathway. Sequencing methods for these modified bases in DNA have been well documented31–37. However, these modified bases also occur naturally in RNA, and their biological roles remain to be elucidated. m5C has been reported to protect RNA from degradation38, regulate mRNA export39, and promote the pathogenesis of bladder cancer40. Additionally, m5C on nuclear mRNA can serve as DNA damage codes to regulate DNA repair41. hm5C has been detected in mRNA42, and its presence was found to favor mRNA translation17. f5C displays approximately 100% modification fraction at C34 in mt-tRNAMet43 and a moderate modification fraction in ct-tRNALeu in human cells43–45. In both cases, NSUN3 was reported to be the methyltransferase that converts the target C to m5C, while ALKBH1 further catalyzes the oxidation of m5C to f5C43. f5C in tRNA is associated with several human diseases46 and f5C in tRNA-Leu-CAA promotes decoding under stress conditions47. In addition, the presence of f5C in yeast and human mRNA has also been detected by LC-MS/MS48,49. Here, we describe f5C-seq, a new method for quantitative sequencing of f5C in HeLa and mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). To detect 5fC in DNA, Zhu et al used malononitrile to specifically react with 5fC in DNA to generate a cyclized base which induces a C-to-T transition during DNA amplification50. Recently, a new method that employs pic-borane to reduce 5fC in DNA to DHU which could be read as T during amplification was reported51. We speculated that pic-borane reduction may also convert f5C base in RNA to DHU under optimized conditions, and RT enzyme may read through DHU efficiently and generate high C-to-T mutation rate to enable f5C detection and quantitation at base resolution in RNA.

To ascertain whether pic-borane facilitates the efficient and quantitative conversion of f5C to DHU in RNA, we initiated our study with the treatment of a 5-mer RNA oligo incorporating an f5C modification with pic-borane under different conditions (Table S1). The reactions were closely monitored utilizing MALDI-TOF MS method. We found that the reduction products were temperature dependent. At 25 °C, f5C was primarily reduced to dihydro-f5C (DHf5C) via 3,4-reduction, where DHU was obtained as the sole product at 70 °C via further deformylation and subsequent deamination (Figure 1a–b). Moreover, we detected a small peak at 1,529 Daltons at 25 °C, which represents the intermediate of 3,4-reduction and deformylation, but without deamination (Figure 1a–b). This observation suggests that deformylation occurs after 3,4-reduction and prior to deamination, which differs from the proposed mechanism for the pic-borane reduction of 5fC in DNA, in which deamination was thought to occur before deformylation51.

Figure 1.

f5C-seq and its chemical validation. a Suggested pic-borane f5C reduction mechanism based on the observed intermediates. b MALDI-TOF MS analysis comparing an untreated f5C-continaing RNA probe with the same probe treated with pic-borane for 2 h at either 25 °C or 70 °C. The observed peaks at m/z values 1,555, 1,557, 1529 and 1,530 represent oligos integrated with f5C, DHf5C, DHC and DHU, respectively. Notably, the peak at 1,557 represents the intermediate that f5C is reduced via 3,4-reduction and undergoes subsequent deformylation process, yielding DHC followed by further deamination to produce DHU. c Primer extension assay of 33-mer f5C-containing RNA oligo treated with pic-borane and malononitrile. FL: full length; T: truncated product; P: primer. d Sanger sequencing of untreated, pic-borane and malononitrile treated f5C-containing 33-mer RNA oligos followed by RT-PCR.

To determine whether RT enzymes can read through DHU and produce a C-to-T mutation in RNA, we undertook a primer extension on an f5C-containing 33-mer RNA oligo (Table S1), previously converted to its DHU counterpart (Figure 1c). Notably, both the untreated f5C-rich probe and the pico-borane treated sample rendered full-length products using the SuperScript II RT enzyme. In contrast, the sample treated with malononitrile predominantly produced RT-stop byproducts. The resulting cDNA products were then amplified by RT-PCR followed by Sanger sequencing. Our analysis revealed that untreated f5C was interpreted as C, while malononitrile treatment led to approximately 50% C-to-T mutations. Impressively, pico-borane treatment produced a significantly elevated C-to-T mutation rate of over 80% (Figure 1d). Collectively, our findings suggest that pico-borane-mediated conversion of f5C to DHU offers superior read-through and C-to-T mutation rates compared to malononitrile treatment. Additionally, we observed no significant RNA degradation when a 45-mer f5C-containing RNA oligo (Table S1) was treated with pico-borane across a temperature spectrum ranging from 55 to 70 °C (Figure S1). The mild nature of pico-borane treatment paved the way for the development of f5C-seq, which performs reduction after integrating the RNA fragments into library construction, followed by high-throughput sequencing (Figure S2).

We next investigated whether the C-to-T mutation rate is dependent on f5C sequence context and whether there is a significant linear correlation between the mutation rate and f5C fractions11,25,28. To do this, we treated fragmented small RNA isolated from HeLa cells treated with E. coli AlkB demethylase to remove the major tRNA methylations that block RT52. We then added spike-in oligos with NNf5CNN motifs (N represents a mixture of A, C, G and U) and five pairs of RNA oligos with different f5C modification fractions (Table S1). After performed 3′- and 5′-ligations, we treated the ligated RNA with pic-borane followed by RT reaction, PCR amplification, and sequencing to determine the C-to-T mutation rates of the reduced f5C. Our results showed that the C-to-T mutation rates were consistently high in all 256 NNf5CNN oligos, suggesting that the C-to-T mutation rate is generally independent of the f5C sequence context (Figure 2a). To our delight, we observed a nearly linear calibration curve, which allows us to precisely deduce the f5C modification fraction from the observed C-to-T mutation rate in RNA (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Validation of f5C-seq by identifying two known f5C sites in human tRNA with next generation sequencing. a Mutation rate is independent of sequence context around the f5C site. b Calibration curve of spike-in oligos containing f5C with varying f5C fractions and C-to-T mutation rates. c C-to-T mutation rates of mt-tRNAMet CAU(C34) and ct-tRNALeu CAA(C34) sites, as well as their neighboring sites, in shControl and shALKBH1 HeLa cells. d C-to-T mutation rates of mt-tRNAMet CAU(C34) and ct-tRNALeu CAA(C34) sites, as well as their neighboring sites, in WT and ALKBH1-KO mESC. Bars represent mean of two technical replicates ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by t-test using the Holm-Sidak method.

In order to construct libraries suitable for sequencing, an alkaline fragmentation step is necessary. Initially, we performed MALDI TOF MS analysis of f5C-containing oligo treated in 0.1M NaHCO3 pH 9.2 at 95 °C for 9 min to evaluate the potential impact of alkaline fragmentation on f5C in RNA. Our data shows that f5C remains unaffected under alkaline fragmentation condition (Figure S3). Previous studies have shown that ALKBH1 catalyzes f5C formation in both mt-tRNAMet and ct-tRNALeu in human cells43. Therefore, we used small RNA isolated from shControl and shALKBH1 HeLa cells to construct f5C-seq libraries (Figure S4a–b). We then examined the C-to-T mutation rates at the known f5C sites in tRNAs. In HeLa cells, we observed a high C-to-T mutation rate of approximately 80% at the mt-tRNAMet f5C site and a low C-to-T mutation rate of around 15% at the ct-tRNALeu f5C site (Figure 2c, S5a), corresponding to f5C modification fractions of 87.2% and 16.4%, respectively, which is consistent with the previous reports based on mass spectrometry analysis43. The bases surrounding the f5C sites had minimal background mutation (Figure 2c). Two known f5C sites at tRNAs also showed very low C-to-U mutation rates in the input libraries (Figure S5). Additionally, we observed a marked reduction of f5C modification fractions in ALKBH1-deficient HeLa cells, while the mutation frequencies at adjacent cytosine sites remained unchanged upon ALKBH1 knockdown (Figure 2c, S5a). Similarly, our findings also revealed that both C34 sites in mt-tRNAMet and ct-tRNALeu in mESCs are f5C-modified (Figure 2d, S5b), with a similar f5C modification fraction to that in the corresponding HeLa tRNAs. Notably, the f5C fractions decreased to nearly undetectable levels in ALKBH1-deficient mES cells (Figure 2d, S5b). Taken together, these findings robustly confirm the accuracy and quantitative reliability of our f5C-seq method in detecting f5C modifications at base resolution in RNA.

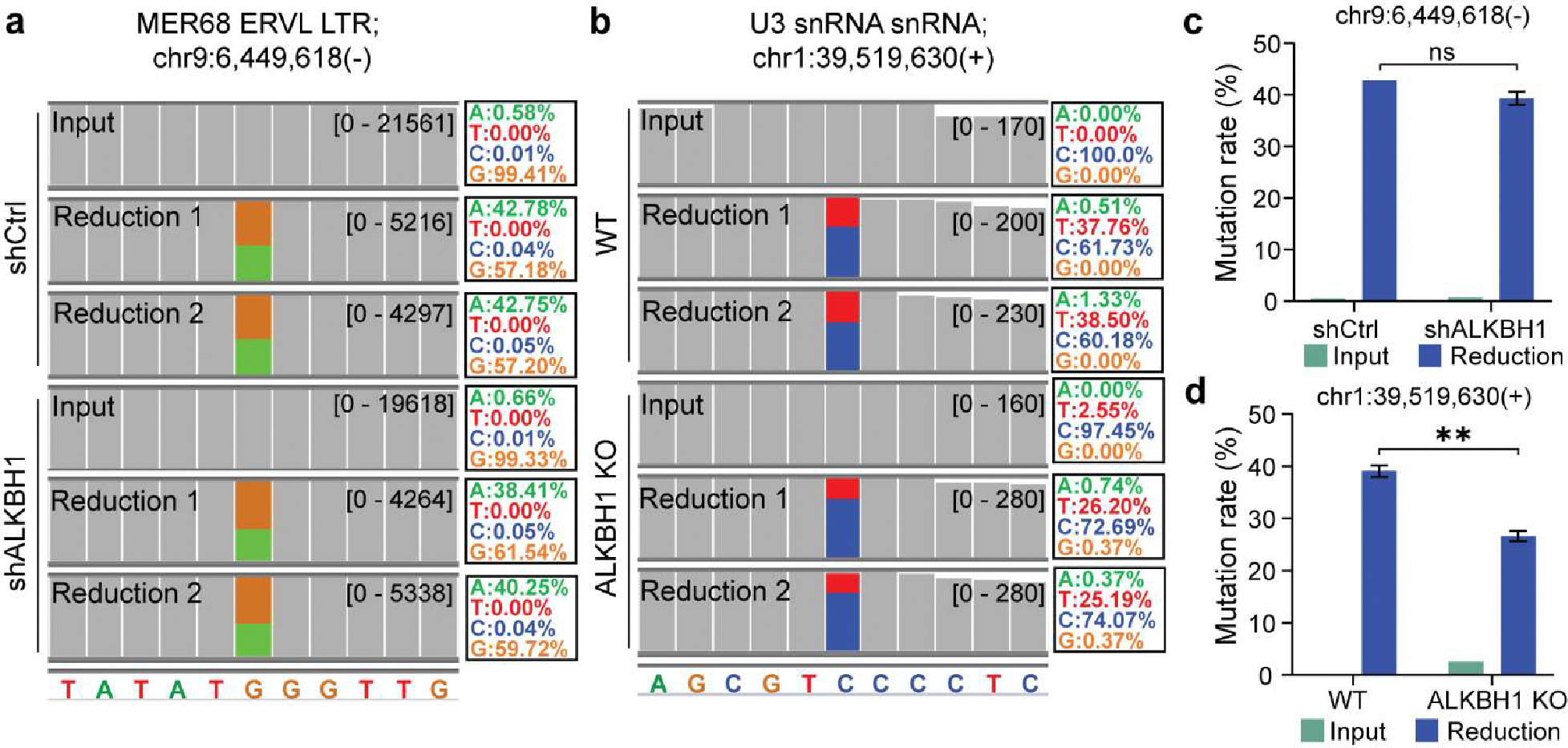

Given that f5C has previously been identified within human mRNA, we then tried to map transcriptome-wide f5C sites in polyA+ RNA isolated from both HeLa and mES cells using f5C-seq. Although we identified several hundred f5C sites in both cell lines, the f5C fraction at each site did not exceed 10%. Interestingly, when we employed f5C-seq on chromatin-associated RNA (caRNA) from HeLa and mES cells, we identified multiple f5C sites with high fraction levels (Table S2). This includes a site on the MER68 ERVL endogenous retrovirus-related Long Terminal Repeats (LTR) in HeLa cells (Figure 3a), and another on the U3 snRNA repeats in mES cells (Figure 3b). While the modification fraction at the MER68 ERVL LTR site remained relatively stable following ALKBH1 knockdown (Figure 3c), we observed a notable reduction at the U3 snRNA repeat site. Specifically, upon ALKBH1 depletion, the modification fraction declined markedly from 39.04% to 26.62%, which corresponds to a decrement in the f5C fraction from 42.57% to 29.27% (Figure 3d). This data presents a compelling avenue for further exploration into the dynamic roles and regulation of f5C modifications in RNA biology.

Figure 3.

Overview of f5C sites detected in caRNA in HeLa and mES cells. a IGV tracks showing the mutation signature of the identified f5C site on caRNA MER68 ERVL LTR in shCtrl and shALKBH1 HeLa cells. b IGV tracks showing the mutation signature of identified f5C site on caRNA U3 snRNA repeats in wide-type (WT) and ALKBH1 knockout (KO) mES cells. c C-to-T mutation rates of detected tRNA f5C site on caRNA MER68 ERVL LTR in shCtrl and shALKBH1 HeLa cells. Statistical significance was determined by t-test using the Holm-Sidak method (ns: not significant). d C-to-T mutation rate of detected f5C site on caRNA U3 snRNA repeats in WT and ALKBH1 KO mES cells. Bars represent mean of two technical replicates ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by t-test using the Holm-Sidak method (**p < 0.01).

It is worth to mention that during the preparation of this manuscript, several other RNA f5C sequencing methods have been published53–55. One of these methods uses pyridine borane as a reductant53, while the other was based on the selective and efficient malononitrile-mediated labeling of f5C residues to generate adducts that are read as C-to-T mutations upon reverse transcription54. However, our f5C-seq method distinguishes itself by utilizing pic-borane as a reductant, akin to the pyridine borane used in published method. Through extensive analysis, we demonstrated that pic-borane can proficiently reduce f5C to DHU, similarly inducing C-to-T transitions at f5C sites during RT-PCR, which facilitates f5C single-base resolution detection. When contrasted with other methods that employ malononitrile or photo-mediated labeling, our technique stands out for its simplicity and efficiency in mapping transcriptome-wide f5C sites. These newly developed methods represent exciting developments in the field and offer alternative approaches to sequencing f5C modifications. The emergence of multiple methods for detecting f5C modifications highlights the growing interest in this area of research and suggests that there is still much to be learned about the function and regulation of these modifications in various cellular contexts. As the field continues to evolve, it will be important to compare the strengths and limitations of different approaches and to identify the best methods for studying f5C modifications in different biological systems.

In summary, we have developed f5C-seq, a quantitative sequencing method for mapping f5C modification in RNA. Our method is based on the chemical principle that f5C in RNA can be specifically and quantitatively reduced to DHU by pic-borane at a higher temperature, and DHU is read as T instead of C in RNA sequencing. It is worth to note that although in principle ca5C can also be converted to DHU by pic-borane to generate C to T mutation, so far, no ca5C has been detected in RNA. Using f5C-seq, we verified the two known f5C sites of mt-tRNAMet (C34) and ct-tRNALeu (C34) in human tRNA and confirmed that their f5C modification fractions are sensitive to ALKBH1 knockdown. Further sequencing confirmed that ALKBH1 is also responsible for the formation of these two f5C sites in mES cells. We then sequenced f5C in HeLa and mESCs polyA+ RNA. The f5C levels in identified hundreds of sites were low and did not exceed 10%. This result is consistent with the low f5C levels (~1.7 ppm) measured in HEK293C polyA+ RNA by LC-MS/MS by Arguello et al56. We also applied f5C-seq to caRNA from HeLa and mES cells and detected several highly modified f5C sites that were not reported previously. We found that f5C located on mouse U3 snRNA repeats was sensitive to ALKBH1 depletion, suggesting that ALKBH1 is also responsible for f5C formation at this position. Interestingly, the f5C fraction identified on human MER68 ERVL LTR did not change upon ALKBH1 KD. Further studies are needed to unravel the enzyme responsible for the formation of f5C on human MER68 ERVL LTR. Other RNA modifications, notably m6A, have been co-transcriptionally integrated into various caRNAs in mammalian cells. These modifications play a pivotal role in controlling RNA abundance, which in turn influences gene transcription through alterations in chromatin accessibility57. Intriguingly, in our studies, we have identified multiple sites on caRNA with pronounced f5C modifications in both HeLa and mouse ES cells. Noteworthy among these are the f5C sites present on the carRNA MER68 ERVL LTR and U3 snRNA repeats. These f5C sites exhibit diverse responses to ALKBH1 KD, which hints at the potential diverse roles of f5C in orchestrating chromatin states, influencing transcription, and governing alternative splicing. This diverges from its established regulatory function in translation. Furthermore, given the prevalence of m5C sites on both caRNA58 and mRNA59, we speculate that f5C could serve as an intermediate in a potential RNA demethylation process. Taken together, f5C-seq provides a quantitative tool for future studies on the biological function of f5C in RNA.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources

This study was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant RM1 HG008935 (C.H.).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental protocols, supporting figures and oligonucleotides sequences are to be found in Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dominissini D Roadmap to the epitranscriptome. Science (80-. ). 346, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao BS, Roundtree IA & He C Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. (2016) doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saletore Y et al. The birth of the Epitranscriptome: deciphering the function of RNA modifications. Genome Biol. 13, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominissini D et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roundtree IA et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 6, 1–28 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kierzek E & Kierzek R The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 4472–4480 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heilman KL, Leach RA & Tuck MT Internal 6-methyladenine residues increase the in vitro translation efficiency of dihydrofolate reductase messenger RNA. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 28, 823–829 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer KD et al. 5′ UTR m6A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 163, 999–1010 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen K et al. High-resolution N6-methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 54, 1587–1590 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominissini D et al. The dynamic N1 -methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 530, 441–446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X et al. Base-Resolution Mapping Reveals Distinct m1A Methylome in Nuclear- and Mitochondrial-Encoded Transcripts. Mol. Cell 68, 993–1005.e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N1-methyladenosine methylome. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 311–316 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safra M et al. The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature 551, 251–255 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinclair WR et al. Profiling Cytidine Acetylation with Specific Affinity and Reactivity. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2922–2926 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arango D et al. Acetylation of Cytidine in mRNA Promotes Translation Efficiency. Cell 175, 1872–1886.e24 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amort T et al. Distinct 5-methylcytosine profiles in poly(A) RNA from mouse embryonic stem cells and brain. Genome Biol. 18, 1–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delatte B et al. Transcriptome-wide distribution and function of RNA hydroxymethylcytosine. Science (80. ). 351, 282–285 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlile TM et al. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature 515, 143–146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Incarnato D et al. High-throughput single-base resolution mapping of RNA 2-O-methylated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 1433–1441 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaringhalam M & Papavasiliou FN Pseudouridylation meets next-generation sequencing. Methods 107, 63–72 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu L et al. m6A RNA modifications are measured at single-base resolution across the mammalian transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1210–1219 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge R et al. m6A-SAC-seq for quantitative whole transcriptome m6A profiling. Nat. Protoc. 2022 182 18, 626–657 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C et al. Absolute quantification of single-base m6A methylation in the mammalian transcriptome using GLORI. Nat. Biotechnol. (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01487-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao YL et al. Transcriptome-wide profiling and quantification of N6-methyladenosine by enzyme-assisted adenosine deamination. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023 1–11 (2023) doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01587-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang LS et al. Transcriptome-wide Mapping of Internal N7-Methylguanosine Methylome in Mammalian mRNA. Mol. Cell 74, 1304–1316.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enroth C et al. Detection of internal N7-methylguanosine (m7G) RNA modifications by mutational profiling sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandolfini L et al. METTL1 Promotes let-7 MicroRNA Processing via m7G Methylation. Mol. Cell 74, 1278–1290.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou H et al. Evolution of a reverse transcriptase to map N 1-methyladenosine in human messenger RNA. Nat. Methods 16, 1281–1288 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang M et al. Quantitative profiling of pseudouridylation landscape in the human transcriptome. Nat. Chem. Biol. (2023) doi: 10.1038/S41589-023-01304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai Q et al. Quantitative sequencing using BID-seq uncovers abundant pseudouridines in mammalian mRNA at base resolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 344–354 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito S et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science (80-. ). 333, 1300–1303 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He YF et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science (80-. ). 333, 1303–1307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song CX et al. Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 68–75 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu M et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell 149, 1368–1380 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song CX et al. Genome-wide profiling of 5-formylcytosine reveals its roles in epigenetic priming. Cell 153, 678–691 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Booth MJ, Marsico G, Bachman M, Beraldi D & Balasubramanian S Quantitative sequencing of 5-formylcytosine in DNA at single-base resolution. Nat. Chem. 6, 435–440 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth MJ et al. Quantitative sequencing of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at single-base resolution. Science (80-. ). 336, 934–937 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuorto F et al. RNA cytosine methylation by Dnmt2 and NSun2 promotes tRNA stability and protein synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 900–905 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export-NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m 5 C reader. Cell Res. 27, 606–625 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H et al. m5C modification of mRNA serves a DNA damage code to promote homologous recombination. Nat. Commun. 11, 3–14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber SM et al. Formation and abundance of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in RNA. ChemBioChem 16, 752–755 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawarada L et al. ALKBH1 is an RNA dioxygenase responsible for cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 7401–7415 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haag S et al. NSUN 3 and ABH 1 modify the wobble position of mt-t RNA Met to expand codon recognition in mitochondrial translation . EMBO J. 35, 2104–2119 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asano K et al. Metabolic and chemical regulation of tRNA modification associated with taurine deficiency and human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1565–1583 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jonkhout N et al. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. Rna 23, 1754–1769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arguello AE et al. Reactivity-dependent profiling of RNA 5-methylcytidine dioxygenases. Nat. Commun. 2022 131 13, 1–17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tardu M, Jones JD, Kennedy RT, Lin Q & Koutmou KS Identification and Quantification of Modified Nucleosides in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1403–1409 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang W et al. Formation and determination of the oxidation products of 5-methylcytosine in RNA. Chem. Sci. 7, 5495–5502 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu C et al. Single-Cell 5-Formylcytosine Landscapes of Mammalian Early Embryos and ESCs at Single-Base Resolution. Cell Stem Cell 20, 720–731.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y et al. Bisulfite-free direct detection of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at base resolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 424–429 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng G et al. Efficient and quantitative high-throughput tRNA sequencing. Nat. Methods 12, 835–837 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y et al. Single-Base Resolution Mapping Reveals Distinct 5-Formylcytidine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 77–84 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li A, Sun X, Arguello AE & Kleiner RE Chemical Method to Sequence 5-Formylcytosine on RNA. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 503–508 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin XY et al. Photo-Facilitated Detection and Sequencing of 5-Formylcytidine RNA. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 61, e202210652 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arguello AE et al. Reactivity-dependent profiling of RNA 5-methylcytidine dioxygenases. Nat. Commun. 13, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu J et al. N6-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science (80-. ). 367, 580–586 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aguilo F et al. Deposition of 5-Methylcytosine on Enhancer RNAs Enables the Coactivator Function of PGC-1α. Cell Rep. 14, 479–492 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen X et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 978–990 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.