Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Cardiovascular (CV) and thromboembolic (TE) events are known complications of glomerular disease (GD), but their incidence and risk factors are poorly characterized. This analysis describes CV and TE outcomes in the Cure GlomeruloNephropathy (CureGN) Network.

Study Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting & Participants

CureGN is a prospective cohort study of children and adults with biopsy-proven minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy (MN), or IgA nephropathy (IgAN)/vasculitis (IgAV). Data from 2,545 children and adults (23% MCD, 23% MN, 25% FSGS, 29% IgAN/IgAV) was analyzed.

Exposure

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), proteinuria, serum albumin, tobacco use, body mass index, hypertension, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Outcomes

CV and TE events.

Analytic Approach

Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate cumulative incidence, and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to estimate associations of histologic diagnosis, age, biological sex, and race. Laboratory and other clinical data were evaluated separately in models adjusted for base model covariates.

Results

Median follow-up time was 4.6 years (IQR 2.7-6.1). The cumulative incidence of first CV and TE event postbiopsy was 3% and 2% in children and 10% and 5% in adults, respectively. No association between GD subtype and risk of CV or TE event was detected. Older age and Black race were associated with higher risk of first CV and TE event {hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval {CI}) per 5 years, CV = 1.17 (1.12-1.23); TE = 1.11 (1.05-1.18); for Black race, CV = 1.62 (1.03-2.56), TE = 2.25 (1.27-4.01)}. Lower eGFR, higher urinary protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR), and lower serum albumin levels at enrollment were associated with higher risk of first CV and TE event (eGFR per 10 mL/min/1.73 m2, CV = 0.87 [0.81-0.93], TE = 0.80 [0.73-0.88]; UPCR per mg/mg, CV = 1.04 [1.02-1.07], TE = 1.03 [1.00-1.07]; serum albumin per g/dL, CV = 0.75 [0.59-0.95], TE = 0.71 [0.53-0.96]).

Limitations

Age of cohort, duration of follow-up.

Conclusions

In the CureGN cohort, elevated risk of incident CV and TE events is associated with severity of kidney disease rather than GD subtype.

Index Words: Cardiovascular, glomerular disease, thromboembolic

Plain-Language Summary

Individuals with glomerular disease are at risk for cardiovascular and thromboembolic events. The aim of our study was to determine the frequency and risk factors for such events in adults and children with minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, membranous nephropathy, and IgA nephropathy/vasculitis enrolled in the CureGN study. Our ultimate goal is to equip physicians with tools to identify high-risk individuals and help develop mitigative therapies. We found that poor kidney function, low serum albumin level, and high levels of urine protein at the time participants entered the study, along with older age and self-reported Black race were associated with a higher risk of both cardiovascular and thromboembolic events. In addition, these risk factors are more important than the specific type of glomerular disease.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and albuminuria are well-established risk factors for cardiovascular (CV) disease in children and adults.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Compared with more common causes of CKD, CV risk in patients with glomerular diseases (GD) might be uniquely affected by fluctuating disease trajectories, substantial proteinuria even at relatively preserved levels of kidney function, and exposure to immunosuppressive therapies. Accordingly, rates and determinants of CV events may differ in those with GD compared with the general CKD population. At the same time, risk for thromboembolic (TE) events is high in patients with GD, especially in the presence of nephrotic syndrome,1,12, 13, 14 yet large-scale studies characterizing the frequency and risk factors for TE events in children and adults with GD are lacking.

CV event rates were recently reported to be 2.5 times higher among adults with GD than population-based controls without GD.1,2 In children with CKD, a high prevalence of traditional CV risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and abnormal glucose metabolism have been reported.15 These traditional CV risk factors are also present in children with GD.11 Regarding TE events, elevated rates compared to non-GD controls are reported among adults with GD, whereas data in children are limited.1 Risk factors for TE events in the general adult population include lower eGFR, albuminuria, older age, smoking, and high body mass index (BMI).12,13,16, 17, 18 Whether these associations also exist in adults and children with GD remains to be established.

To address these knowledge gaps, we report the incidence of CV and TE events in children and adults enrolled in the Cure GlomeruloNephropathy (CureGN) Network (see Item S1 for a list of CureGN consortium members), a multinational, prospective, observational study of individuals with biopsy-confirmed GD. We also examine associations between demographic, traditional CV, and kidney-specific risk factors and subsequent CV and TE events.

Methods

Participant Sample

CureGN is a prospective cohort study of children (<18 years old) and adults (≥18 years old) with kidney biopsy-confirmed minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy (MN), or IgA nephropathy (IgAN)/vasculitis (IgAV) enrolled at 71 sites across the United States and in Canada, Italy, and Poland. Participants must have a qualifying diagnosis within 5 years of study enrollment. Exclusion criteria include chronic dialysis, kidney transplant, diabetes mellitus, institutionalization, history of solid organ or bone marrow transplant, system lupus erythematosus, active malignancy (except for nonmelanoma skin cancer), active HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C at the time of biopsy. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Salus Institutional Review Board (IRB), which serves as the single IRB (#IRB00013544), and informed consent or assent, where appropriate, was obtained for all participants.19

Data Collection

Enrollment began in December 2014 and is ongoing. Participants enrolled as of December 2022 with at least 1 completed follow-up visit are included in this analysis. Demographic and clinical data as well as laboratory values including serum creatinine levels, urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR), serum albumin levels, and cholesterol levels were recorded at enrollment. Medication use, laboratory values, comorbid conditions, and acute care utilization (emergency department visits or hospitalizations) were collected at 4- to 6-month intervals through in-person or remote follow-up visits. For participants <25 and ≥25 years old, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the U25 formula and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula (without the race coefficient), respectively.20,21

Outcomes of Interest

Participants were considered to have a CV event (excluding hypertension) or TE event if either of 2 conditions were satisfied: (1) a new CV or TE comorbid condition was reported on the follow-up visit case report form (CRF) or (2) a CV or TE event treated in an acute care setting was identified by questions on hospitalization form or discharge summary, and the diagnosis was then converted into an ICD-10 diagnosis code (Tables S1 and S2). Prespecified CV and TE event types collected on the CureGN follow-up CRF are listed in Table S3; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code diagnoses were mapped to these event types. Cardiac arrythmias were included in CV events as CKD, electrolyte fluctuations, and medications may increase risk for arrythmias in patients with GD.22 For the purposes of this analysis, recognizing that CV and TE categories overlap (TE is a form of CV disease), we assigned atherothrombotic events to the CV group and venous thromboembolism (VTE) and other noncardiac, noncerebral thrombotic events to the TE group.

Statistical Methods

Demographic and clinical characteristics at the time of biopsy and enrollment were summarized using frequency and percent for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to calculate the cumulative incidence of CV and TE events from the time of biopsy (postbiopsy), as well as stratified by age (<18 vs ≥18 years old at biopsy) and diagnosis. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard of first CV or TE event postenrollment for participants without a pre-enrollment history of CV or TE events, respectively. For these models, time zero was set at enrollment due to greater availability of clinical data (model covariates) at or after enrollment. The primary exposure was GD diagnosis. Clinically relevant covariates selected for multivariable models were age, sex, self-reported race, eGFR, UPCR, serum albumin level, tobacco use, BMI, blood pressure, lipid profile, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade use at enrollment. All models were adjusted for time from biopsy to enrollment. For continuous variables, functional forms for the associations with outcomes were assessed in univariable models and determined to be approximately linear.

Due to the small number of outcome events, base models were first built to include exposure of interest (GD diagnosis), demographics (race, age, and biological sex), and time from biopsy to enrollment. Subsequently, other covariates at enrollment (eGFR, UPCR, serum albumin, tobacco use, BMI, cholesterol labs, blood pressure, etc.) were added individually to the base model. Sequential models adding domains of variables (kidney laboratories, CV risk factors) were used for the CV model, but not for the TE model due to the low number of TE events. Missing baseline data were imputed using the sequential regression technique implemented in IVEware 2.0.23,24,25 Ten imputed data sets were generated, and all analyses were run on each imputed dataset. Results were combined using Rubin’s rules.26,27 Statistical analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

In total, 2,545 participants with GD were included: 590 MCD, 641 FSGS, 574 MN, and 740 IgAN/IgAV (Table 1). Median time from biopsy to enrollment was 1 year (interquartile range [IQR] 0.3-2.5). The median follow-up time was 4.6 years (IQR 2.7-6.1). At enrollment, the median age was 32 years (IQR 14-52), ranging from 14 years for MCD to 52 years for MN. At biopsy, median eGFR was 86 mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 55-112), ranging from 72 mL/min/1.73 m2 for FSGS to 106 mL/min/1.73 m2 for MCD; median UPCR was 3.3 mg/mg (IQR 1.1-7.1), ranging from 1.5 mg/mg for IgAN/IgAV to 5.5 mg/mg for MN; and median serum albumin was 3.1 g/dL (IQR 2.2-3.8). Compared with time of biopsy, distributions at enrollment were similar for eGFR, lower for UPCR, and higher for serum albumin levels.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Median (IQR) or N (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCD (n = 590) | FSGS (n = 641) | MN (n = 574) | IgAN/IgAV (n = 740) | All (n = 2,545) |

|

| Age at enrollment, y | 14 (7-35) | 32 (15-50) | 52 (37-64) | 27 (14-43) | 32 (14-52) |

| 0-9 | 210 (36%) | 76 (12%) | 7 (1%) | 82 (11%) | 375 (15%) |

| 10-19 | 159 (27%) | 144 (22%) | 51 (9%) | 218 (29%) | 572 (22%) |

| 20-39 | 84 (14%) | 171 (27%) | 110 (19%) | 214 (29%) | 579 (23%) |

| 40-59 | 85 (14%) | 160 (25%) | 218 (38%) | 175 (24%) | 638 (25%) |

| 60+ | 52 (9%) | 90 (14%) | 188 (33%) | 51 (7%) | 381 (15%) |

| Male sex | 325 (55%) | 343 (54%) | 348 (61%) | 445 (60%) | 1461 (57%) |

| Hispanic/Latinoa | 65 (11%) | 94 (15%) | 70 (12%) | 109 (15%) | 338 (13%) |

| Raceb | |||||

| Asian | 53 (9%) | 33 (5%) | 46 (8%) | 80 (11%) | 212 (9%) |

| Black | 103 (18%) | 171 (28%) | 90 (16%) | 28 (4%) | 392 (16%) |

| Multi-racial/Otherg | 28 (5%) | 34 (6%) | 15 (3%) | 24 (3%) | 101 (4%) |

| White | 385 (68%) | 376 (61%) | 405 (73%) | 583 (82%) | 1749 (71%) |

| Weight status at enrollmentb,h | |||||

| Underweight | 11 (2%) | 10 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 11 (2%) | 36 (1%) |

| Normal weight | 217 (38%) | 194 (31%) | 148 (27%) | 289 (40%) | 848 (34%) |

| Overweight | 158 (27%) | 176 (29%) | 179 (32%) | 185 (26%) | 698 (28%) |

| Obese | 189 (33%) | 236 (38%) | 225 (40%) | 239 (33%) | 889 (36%) |

| BMI (adults only)b | 27.6 (24-32.9) | 28.3 (24.9-33.8) | 28.8 (24.8-33.4) | 27.3 (24.2-32.4) | 28.1 (24.4-33.2) |

| BMI percentile (children only)b | 87 (66.3-96.3) | 86.5 (51.4-96.5) | 93.6 (71.7-96.6) | 83.1 (55.2-96) | 86.3 (58.6-96.4) |

| Blood pressure at enrollmentb,i | |||||

| Normal blood pressure | 268 (48%) | 215 (35%) | 156 (29%) | 319 (46%) | 958 (40%) |

| Elevated blood pressure | 84 (15%) | 82 (13%) | 76 (14%) | 98 (14%) | 340 (14%) |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 145 (26%) | 158 (26%) | 136 (25%) | 176 (25%) | 615 (26%) |

| Stage 2 hypertension | 67 (12%) | 156 (26%) | 171 (32%) | 102 (15%) | 496 (21%) |

| Tobacco exposure at enrollmenta | 80 (14%) | 163 (26%) | 246 (43%) | 167 (23%) | 656 (26%) |

| Secondhand tobacco exposure at enrollmentb | 108 (19%) | 95 (15%) | 65 (12%) | 102 (14%) | 370 (15%) |

| Steroid use at enrollment | 309 (52%) | 204 (32%) | 108 (19%) | 212 (29%) | 833 (33%) |

| Other immunosuppression use at enrollment | 157 (27%) | 131 (20%) | 145 (25%) | 65 (9%) | 498 (20%) |

| RAAS blockade use at enrollment | 186 (32%) | 374 (58%) | 383 (67%) | 471 (64%) | 1,414 (56%) |

| Other antihypertensive medication use at enrollment | 206 (35%) | 385 (60%) | 441 (77%) | 379 (51%) | 1,411 (55%) |

| Time from diagnosis to enrollment, yearsa | 1.8 (0.7-3.8) | 1.4 (0.5-3.5) | 1 (0.4-2.6) | 1.1 (0.3-2.8) | 1.2 (0.4-3.1) |

| Time from biopsy to enrollment, years | 1.1 (0.3-2.8) | 1.1 (0.4-2.8) | 0.9 (0.3-2.3) | 0.9 (0.2-2.4) | 1 (0.3-2.5) |

| Laboratory tests at enrollment | |||||

| eGFR at enrollment, mL/min/1.73 m2,c | 99 (81-118) | 65 (37-94) | 78 (52-102) | 81 (50-102) | 83 (53-104) |

| Serum albumin at enrollment, g/dLe | 3.7 (2.9-4.2) | 3.7 (3-4.2) | 3.2 (2.5-3.9) | 4.0 (3.6-4.3) | 3.8 (3.0-4.2) |

| 0 to <2.5 | 81 (18%) | 67 (14%) | 103 (23%) | 19 (4%) | 270 (14%) |

| 2.5 to <3.5 | 94 (20%) | 121 (25%) | 147 (33%) | 82 (15%) | 444 (23%) |

| ≥3.5 | 285 (62%) | 292 (61%) | 194 (44%) | 433 (81%) | 1204 (63%) |

| UPCR at enrollment, mg/mge | 0.4 (0.1-3.4) | 1.8 (0.5-4.2) | 3.0 (0.9-6.6) | 0.6 (0.2-1.7) | 1.1 (0.2-3.7) |

| 0 to <0.3 | 213 (47%) | 95 (19%) | 56 (12%) | 201 (33%) | 565 (28%) |

| 0.3 to <3.0 | 120 (26%) | 223 (45%) | 172 (38%) | 328 (54%) | 843 (42%) |

| ≥3.0 | 123 (27%) | 173 (35%) | 223 (49%) | 83 (14%) | 602 (30%) |

| Total cholesterol levels at enrollment, mg/dLf | 221 (176-298) | 214 (170-281) | 224 (183-287) | 191 (168-224) | 210 (173-269) |

| HDL cholesterol levels at enrollment, mg/dLf | 64 (54-87) | 55 (42-74) | 55 (42-74) | 50 (41-63) | 56 (43-73) |

| LDL cholesterol levels at enrollment, mg/dLf | 126 (94-170) | 119 (86-169) | 129 (92-180) | 116 (95-136) | 121 (92-165) |

| Laboratory tests at biopsy | |||||

| eGFR at biopsy, mL/min/1.73 m2d | 106 (82-127) | 72 (41-103) | 90 (64-110) | 75 (47-104) | 86 (55-112) |

| Serum albumin levels at biopsy, g/dLe | 2.4 (1.8-3.2) | 3 (2.1-3.8) | 2.6 (2-3.2) | 3.7 (3.2-4.1) | 3.1 (2.2-3.8) |

| 0 to <2.5 | 222 (51%) | 166 (36%) | 181 (44%) | 48 (9%) | 617 (33%) |

| 2.5 to <3.5 | 136 (31%) | 123 (27%) | 161 (39%) | 140 (25%) | 560 (30%) |

| ≥3.5 | 81 (18%) | 170 (37%) | 70 (17%) | 367 (66%) | 688 (37%) |

| UPCR at biopsy, mg/mge | 4.7 (0.8-9.2) | 4.1 (2-7.9) | 5.5 (2.7-8.4) | 1.5 (0.7-3.3) | 3.3 (1.1-7.1) |

| 0 to <0.3 | 75 (17%) | 26 (6%) | 21 (5%) | 68 (12%) | 190 (10%) |

| 0.3 to <3.0 | 108 (24%) | 153 (32%) | 95 (23%) | 349 (60%) | 705 (37%) |

| ≥3.0 | 258 (59%) | 293 (62%) | 292 (72%) | 165 (28%) | 1008 (53%) |

Note: Values for categorical variables are presented as counts (percentage among non-missing values) and values for continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range). IQR, interquartile range; MCD, minimal change disease; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; MN, membranous nephropathy; IgAN, Immunoglobulin A nephropathy; IgAV, Immunoglobulin A vasculitis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UPCR, urine protein-creatinine ratio; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Missing.

<1%.

1%-5%.

13%.

16%.

20%-27%.

65%-75%.

Other race includes Native American and Pacific Islander.

Weight status: for participants ≥18 years old, BMI < 18.5 is underweight, BMI 18.5 to <25 is normal weight, BMI 25 to <30 is overweight, BMI ≥30 is obese; for participants <18 years old, BMI <fifth percentile is underweight, BMI 5th to <85th percentile is normal, BMI 85th to <95th percentile is overweight, BMI ≥95th percentile is obese.

Blood pressure [BP]: for participants ≥13 years old, systolic BP [SBP] < 120 and diastolic BP [DBP] < 80 is normal, SBP 120-129 and DBP < 80 is elevated, SBP 130-139 or DBP 80-89 is stage 1 hypertension, SBP ≥ 140 or DBP ≥ 90 is stage 2 hypertension; for participants < 13 years old, BP < 90th percentile is normal, BP 90 to <95th percentile or 120/80 mm Hg to <95th percentile, whichever is lower, is elevated, BP ≥95th percentile to <95th percentile + 12 mm Hg, or 130/80-139/89 mm Hg, whichever is lower, is stage 1 hypertension, BP ≥95th percentile + 12 mm Hg, or ≥140/90 mm Hg, whichever is lower, is stage 2 hypertension.

Cardiovascular Events

Cumulative Incidence: Postbiopsy

Among the 2,545 participants, 2,337 (98% of children, 88% of adults) had no history of CV events at the time of biopsy. After biopsy, 166 (7%) of those with no CV history experienced at least 1 CV event during follow-up, including 23 participants who also experienced a TE event. Overall, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative incidence of CV events postbiopsy were 1.3%, 3.4%, and 5.4%, respectively (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular and thromboembolic events since biopsy.

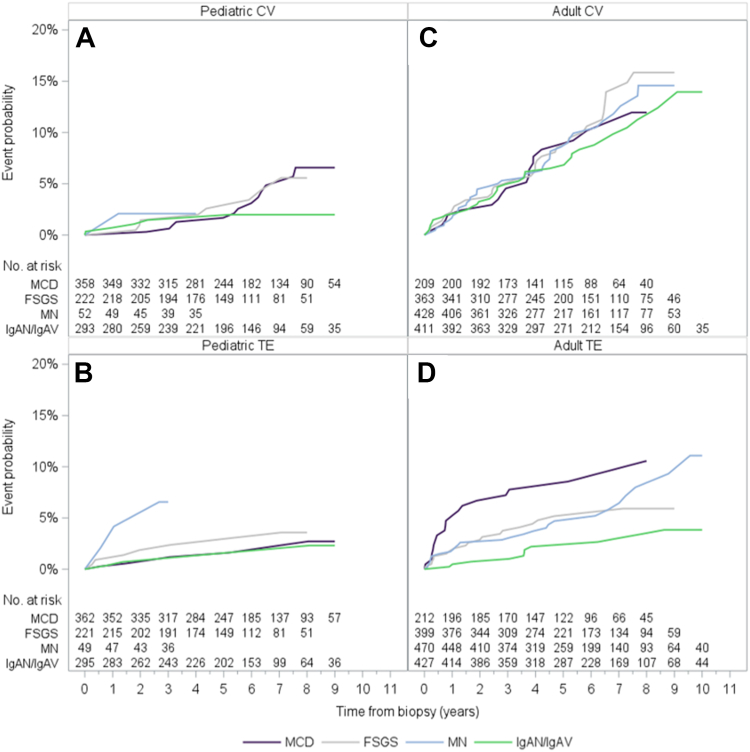

Three percent of children (n = 29) without a history of CV events experienced at least 1 CV event postbiopsy; 4 of these participants also experienced TE events. Among children, “other” CV events (ie, acute pericarditis, other cerebrovascular diseases, other diseases of the pericardium, other pulmonary heart diseases, complications of heart disease) were the most common (n = 10), followed by arrhythmia (n = 6) (Fig S1, Table S3). The 5-year cumulative incidence of postbiopsy CV events in children was highest in participants with FSGS (2.6%), followed by MN (2.1%), MCD (1.7%), and IgAN/IgAV (1.5%) (Fig 2A).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular and thromboembolic events since biopsy, by diagnosis and age at biopsy.

In adults without a history of CV events, 10% (n = 137) experienced at least 1 CV event postbiopsy; 19 of these participants also experienced TE events. Arrhythmia was the most common CV event (n = 50) in adults, followed by coronary artery disease (n = 25) (Figure S1, Table S3). By GD subtype, the 5-year cumulative incidence of postbiopsy CV event in adults ranged from 6.5% in IgAN/IgAV to 8.6% in MN (Fig 2C).

Multivariable Analysis: Postenrollment

Among participants without a history of CV events at enrollment (n = 2,299), 6% (n = 128) had at least 1 CV event postenrollment. Among the “base model” covariates, age at enrollment and Black race were positively associated with first CV event (age: hazard ratio [HR], 1.17 per 5 years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12-1.23; Black race: HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.03-2.56), whereas Asian race was inversely associated with first CV event (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.09-0.93) (Fig 3, Table S4). No association between GD subtype and hazard of first CV event was detected. Added individually to the base model, enrollment UPCR was positively associated with first CV event (HR, 1.04 per mg/mg; 95% CI, 1.02-1.07), whereas eGFR and serum albumin level at enrollment were inversely associated with first CV event (HR, 0.87 per 10 mL/min/1.73 m2; 95% CI, 0.81-0.93 and HR, 0.75 per g/dL; 95% CI, 0.59-0.95, respectively). In sequential models adjusting for other laboratory values and CV risk factors, older age and lower eGFR retained their association with a higher hazard of first CV event (Table S5, Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Cox proportional hazards model time from enrollment to first cardiovascular event (N = 2,299 participants).

Thromboembolic Events

Cumulative Incidence: Postbiopsy

In total, 2,434 participants (99% of children, 94% of adults) had no known history of TE event at the time of biopsy. Among those, 95 (4%) experienced at least 1 TE event postbiopsy. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative incidences of TE event postbiopsy were 1.3%, 2.4%, and 3.4%, respectively (Fig 1). In total, 2% (n = 19) of children and 5% (n = 76) of adults without a history of TE events experienced at least 1 TE event postbiopsy. In children and adults, deep vein thrombosis was the most common (10 and 44 participants, respectively), followed by PE (5 and 22 participants, respectively). Renal vein or artery thrombosis occurred in 5 children and 10 adults (Fig S1, Table S3).

In children, the 1-year cumulative incidence for a TE event was particularly high (6.6%) for MN. Because the pediatric MN cohort was substantially smaller (n = 49) than other GD subtypes, 3- and 5-year risks are not shown. Among the other diagnoses, children with FSGS had the highest 3- and 5-year cumulative incidence of TE events (1.9% and 2.4%, respectively), followed by MCD (0.9% and 1.2%, respectively) and IgAN/IgAV (0.7% for both). In adults, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative incidences of TE events were highest in MCD followed by FSGS, MN, and IgAN/IgAV (7.8%, 5.2%, 4.7%, and 2.2%, respectively) (Fig 2D).

Multivariable Analysis: Postenrollment

Among participants without TE history at enrollment (n = 2,402), 63 (3%) had at least 1 TE event postenrollment. The first TE event was positively associated with Black race (HR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.27-4.01) and age (HR, 1.11 per 5 years; 95% CI, 1.05-1.18) (Fig 4, Table S6). No association between GD subtype, tested as IgAN/IgAV versus MCD, FSGS, and MN, and probability of TE event was detected (P = 0.10). Added individually to the base model, UPCR at enrollment was positively associated with first TE event (HR, 1.03 per mg/mg; 95% CI, 1.00-1.07), whereas enrollment eGFR and serum albumin levels were inversely associated with first TE event (HR, 0.80 per 10 mL/min/1.73 m2; 95% CI, 0.73-0.88 and HR, 0.71 per g/dL; 95% CI, 0.53-0.96, respectively).

Figure 4.

Cox proportional hazards model time from enrollment to first thromboembolic event (N = 2,402 participants).

Discussion

In this multicenter cohort of more than 2,500 children and adults with biopsy-proven GD followed for a median of 4 years, 3% of children and 10% of adults without a prior history of CV events experienced at least one postbiopsy CV event, whereas 2% of children and 5% of adults without a history of TE events experienced at least 1 postbiopsy TE event. This cohort comprised relatively younger participants and is enriched for children, with 75% of the cohort aged 52 years or younger. CureGN excluded individuals with diabetes at time of biopsy, which likely contributed to the lower risk of CV and TE events than reported in other studies. Lower eGFR, higher UPCR, lower serum albumin level, older age, and Black race were associated with higher risk of CV and TE events. We did not, however, identify associations between GD subtype and risk of either CV or TE events.

In this study, the cumulative incidences of first ever CV event at 1- and 5-years postbiopsy were 1.3% and 5.4% respectively and roughly 3-fold higher in adults than children. Despite limitations in comparisons, these risks are comparable with other studies and higher than in the general population. The increased risk of arrythmias and heart failure in patients with CKD is well established.22,28 Fluctuations in serum potassium levels with RAAS blockade, and changes in circulating volume and electrolytes with diuretic use, all used routinely in the care of GD patients who may also have underlying CKD, may contribute to arrythmias. Similarly, the risk of heart failure should be explored in GD patients given the presence of shared risk factors such as hypertension. A recent study of 907 adults with primary nephrotic syndrome in a Kaiser Permanente database reported the rate of acute coronary syndrome was 0.01/year, 2.5-fold higher than matched controls.1 Our study similarly found CV events were associated with proteinuria and lower eGFR.1,2 Mechanisms underlying this association require elaboration as several factors have been proposed.29 Albuminuria, in those with or without diabetes, is a well-known predictor of CV events including stroke, myocardial infarction, and CV death.6,30 Furthermore, albuminuria may develop before other traditional CV risk factors, especially in young adults,30 which is relevant to our GD cohort. Albuminuria is a known marker of endothelial dysfunction, and several studies purport a role of inflammation, evidenced by increases in proinflammatory cytokines, elevated C-reactive protein levels, and increased oxidative stress in patients with kidney disease.23,29 Additionally, some literature supports the possibility that atherosclerosis may be accelerated by elevated levels of circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in the setting of kidney dysfunction.24,26

For first ever TE events, the 5-year postbiopsy cumulative incidence was 3.4% and was highest in children with FSGS (2.4%) and adults with MCD (7.8%). The overall risk we report is higher than in the recent Kaiser Permanente study of adults with primary nephrotic syndrome (0.25% per year), though this comparison across data sources should be interpreted with caution.1 In both children and adults in CureGN, the most common TE event was deep vein thrombosis, followed by pulmonary embolism, as seen in the general population.31 As with other studies in kidney disease populations, our study found an association of TE events in children and adults with lower serum albumin levels, lower eGFR, higher BMI, and tobacco use at enrollment.1,12,21,32,33 Comparing across GD subtypes, MN has been linked to greater TE risk.34 However, this finding was not replicated in our cohort. As an explanation, this often-reported association may be because of profound nephrotic syndrome seen with MN, rather than the underlying cause of MN per se. CureGN is well-designed to gain insight into this possibility. Beyond kidney-specific risk factors, we identified self-reported Black race as a risk factor for both CV and TE events. Although the association of Black race with CV events in the general population is well known, its association with TE events is less certain, with inconsistent associations reported for venous thromboembolism.31,35 Mechanisms to explain differences in observed risk by race are poorly understood. In the setting of kidney disease, and in particular GD, a higher prevalence of APOL1 risk genotype could potentially contribute to a heightened CV risk.36 This hypothesis merits further study as genetic data, including that from CureGN, becomes available. At a general level, our observations highlight the imperative to further explore reasons underlying the observed associations of race with adverse health outcomes and to mitigate inequalities they may represent.

The pathophysiology of thrombogenesis in patients with GD and underlying nephrotic syndrome remains incompletely understood but is likely multifactorial, potentially involving an interplay among genetic factors, environmental conditions, comorbid conditions, and acquired risk factors during illness such as medications, central venous catheters, protein loss in the urine, and a proinflammatory state.33,37,38 GD may predispose to enhanced platelet activation and aggregation, thereby increasing the risk of TE along with stimulation of additional proinflammatory pathways promoting thrombosis,14 During times of heavy proteinuria in GD, there is urinary loss of proteins including antithrombin and protein S which theoretically shift toward a prothrombotic state.33 However, a recent analysis of 208 subjects pooled from 3 nephrotic syndrome cohorts found that antithrombin deficiency was not uniform in nephrotic syndrome and concluded that it likely has a limited role in the mechanisms underlying hypercoagulable states.39 Additional mechanistic investigation leveraging studies with a larger number of TE cases, such as CureGN, is warranted.

Our study has many strengths that add to the literature evaluating CV and TE outcomes in GD. Prior studies did not consistently confirm GD diagnoses by kidney biopsy, were restricted to either children or adults, and typically focused on either CV or TE events, not both. Many prior studies were limited to single glomerular diseases, raising the chance that disease-specific inferences made, such as between MN and TE events, may be spurious (ie, explained by nephrotic syndrome rather than cause of GD). Prior reports also included participants with diabetes, without disentangling the potential contributions from GD alone from that of diabetes in determining CV or TE risk. CureGN participants were followed prospectively with collection of rich clinical data following a study protocol, in contrast to retrospective and other studies with a higher risk for ascertainment bias. Children with nephrotic syndrome are generally presumed to have MCD and hence not routinely biopsied. The inclusion of biopsy-proven MCD only, although not necessarily representative of all children with the disease, adds to the rigor of the study. CureGN is also substantially larger and has longer follow-up time than many other published studies.

Despite these strengths, our study highlights challenges associated with studying infrequently occurring outcomes because it was insufficiently powered to include all potential risk factors concurrently in our models or to precisely estimate event rates in certain subgroups due to low event counts. Although some of our data, between disease onset and enrollment, were captured retrospectively and thus subject to biased ascertainment, we consider substantial under-ascertainment unlikely, as pre-enrollment event rates were similar or higher than rates following enrollment. For multivariable modeling, we chose enrollment date as time zero so that we could include only prospectively collected data in our models.

Although prior studies have established that patients with GD are at higher risk of CV and TE events than the general population, the limited data on incidence and risk factors in children and adults and across causes of GD has hindered effective risk stratification, patient counseling, and prevention strategies.1,4 Our findings from CureGN help address these knowledge gaps. The analyses confirm previously established risk factors for CV and/or TE events including reduced eGFR, low serum albumin levels, obesity, older age, and tobacco use and clarify that CV and TE risk appear to be driven predominantly by severity of disease rather than GD subtype. Novel to our study is the finding of increased TE risk with self-reported Black race, and further work is needed to understand the reasons for this association. Because glomerular diseases are rare and CV and TE events uncommon, especially in younger individuals, studies such as CureGN that have enrolled a large patient sample with rich clinical and biospecimen data are ideal sources for further investigation to gain mechanistic understanding. Although the short-term clinical focus should target modifiable risk factors using existing pharmacologic or lifestyle interventions, longer-term goals need to aim for precision-based strategies to lessen the burden of these serious complications of GD.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Shikha Wadhwani, MD, MS, Sarah A. Mansfield, MS, Abigail R. Smith, PhD, MS, Bruce M. Robinson, MD, MS, Eman Abdelghani, MD, Amira Al-Uzri, MD, Isa F. Ashoor, MD, Sharon M. Bartosh, MD, Aftab S. Chishti, MD, Salim S. Hayek, MD, Michelle A. Hladunewich, MD, Bryce A. Kerlin, MD, Siddharth S. Madapoosi, MPH, Laura H. Mariani, MD, Amy K. Mottl, MD, Michelle N. Rheault, MD, Michelle M. O'Shaughnessy, MD, Christopher John Sperati, MD, Tarak Srivastava, MD, David T. Selewski, MD, Chia-shi Wang, MD, Craig S. Wong, MD, Donald J. Weaver, Jr., MD, PhD, Myda Khalid, MD; on behalf of Cure GlomeruloNephropathy (CureGN) Study Consortium

Author Contributions

Research idea and study design: MK, SW, SM, AS, BR; data acquisition: SW, SM, AS, BR, EA, AA, IA, SB, AC, DG, SH, MH, BK, SM, LM, AM, MR, MO, CS, TS, DS, CW, CSW, DW, MK; data analysis/interpretation: SM, AS, MK, SW, BR, BK, SH; statistical analysis: SM, AS; supervision or mentorship: AS, BR. Each author contributed important intellectual content during article drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Funding for the CureGN consortium is provided by U24DK100845 (formerly UM1DK100845), U01DK100846 (formerly UM1DK100846), U01DK100876 (formerly UM1DK100876), U01DK100866 (formerly UM1DK100866), and U01DK100867 (formerly UM1DK100867) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Patient recruitment is supported by NephCure Kidney International. Dates of funding for first phase of CureGN was September 16, 2013, to May 31, 2019.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Wang: NIH-NIDDK 5K23DK118189. Dr Khalid: NIH-NIAID R01AI165327. Dr O'Shaughnessy: Consulting/honoraria from Chinook therapeutics, Vera therapeutics, Vifor pharma, unrelated to the subject of this work. Dr Srivastava: Research funding from Roche, Apellis Pharmaceuticals, and Travere Therapeutics. Dr Selewski: Previous research funding from Travere Therapeutics. Dr Rheault: Research funding from Chinook, Travere, Reata, R3R, Sanofi; consulting from Visterra. Dr Mottl: Consulting for Chinook, Bayer; research funding from Alexion, Bayer, Pfizer. Dr Kerlin: NIH-NIDDK R01DK124549. Dr Robinson: Consultancy fees or travel reimbursement in the last 3 years from AstraZeneca, Kyowa Kirin Co., and Monogram Health, paid directly to his institution of employment, and from GSK. Dr Wong: NIH-NIDDK 5UO1DK066143-8, UNM CTSC UL1TR001449. Dr Wadhwani: Consulting/honoraria from GSK, Calliditas, and Travere Therapeutics. Dr Hayek: NHLBI R01-HL153384 and NIDDK R01-DK128012. Dr Hladunewich: Ionis IgA study, Chinook IgA Study, Pfizer FSGS study, Roche Preeclampsia biomarker study, Ontario Renal Network.

Peer Review

Received December 23, 2023, as a submission to the expedited consideration track with 2 external peer reviews. Direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form May 2, 2024.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1: Cardiovascular and thromboembolic event counts.

Figure S2: Sequential time from enrollment to first cardiovascular event Cox proportional hazards models (N = 2,299 participants).

Item S1: List of CureGN consortium members.

Table S1: ICD-10 diagnosis codes at hospital discharge used to identify cardiovascular events.

Table S2: ICD-10 diagnosis codes at hospital discharge used to identify thromboembolic events.

Table S3: Counts of first cardiovascular and thromboembolic events following kidney biopsy and study enrollment, overall and cause-specific.

Table S4: Cox proportional hazards model time from enrollment to first cardiovascular event (N = 2,299 participants).

Table S5: Sequential time from enrollment to first cardiovascular event Cox proportional hazards model (N = 2,299 participants).

Table S6: Cox proportional hazards model time from enrollment to first thromboembolic event (N = 2,402 participants).

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1, S2; Item S1; Table S1-S6.

References

- 1.Go A.S., Tan T.C., Chertow G.M., et al. Primary nephrotic syndrome and risks of ESKD, cardiovascular events, and death: The Kaiser Permanente Nephrotic Syndrome Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2303–2314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020111583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canney M., Gunning H.M., Zheng Y., et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in individuals with primary glomerular diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80(6):740–750. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis C. Matsushita K., van der Velde M., et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go A.S., Chertow G.M., Fan D., McCulloch C.E., Hsu C.Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klausen K., Borch-Johnsen K., Feldt-Rasmussen B., et al. Very low levels of microalbuminuria are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and death independently of renal function, hypertension, and diabetes. Circulation. 2004;110(1):32–35. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133312.96477.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerstein H.C., Mann J.F., Yi Q., et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286(4):421–426. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen J.B., Yang W., Li L., et al. Time-updated changes in estimated GFR and proteinuria and major adverse cardiac events: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(1):36–44.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello A.K., Hemmelgarn B., Lloyd A., et al. Associations among estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(6):1418–1426. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09741110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Velde M., Matsushita K., Coresh J., et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011;79(12):1341–1352. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gansevoort R.T., Correa-Rotter R., Hemmelgarn B.R., et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashoor I.F., Mansfield S.A., O'Shaughnessy M.M., et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in childhood glomerular diseases. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(14) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoodi B.K., ten Kate M.K., Waanders F., et al. High absolute risks and predictors of venous and arterial thromboembolic events in patients with nephrotic syndrome: results from a large retrospective cohort study. Circulation. 2008;117(2):224–230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massicotte-Azarniouch D., Bader Eddeen A., Lazo-Langner A., et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients by albuminuria and estimated GFR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(6):826–833. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loscalzo J. Venous thrombosis in the nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):956–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1209459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson A.C., Schneider M.F., Cox C., et al. Prevalence and correlates of multiple cardiovascular risk factors in children with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(12):2759–2765. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03010311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wattanakit K., Cushman M., Stehman-Breen C., Heckbert S.R., Folsom A.R. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(1):135–140. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmoodi B.K., Gansevoort R.T., Naess I.A., et al. Association of mild to moderate chronic kidney disease with venous thromboembolism: pooled analysis of five prospective general population cohorts. Circulation. 2012;126(16):1964–1971. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.113944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregson J., Kaptoge S., Bolton T., et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):163–173. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariani L.H., Bomback A.S., Canetta P.A., et al. CureGN study rationale, design, and methods: establishing a large prospective observational study of glomerular disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(2):218–229. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce C.B., Munoz A., Ng D.K., Warady B.A., Furth S.L., Schwartz G.J. Age- and sex-dependent clinical equations to estimate glomerular filtration rates in children and young adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2021;99(4):948–956. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inker L.A., Eneanya N.D., Coresh J., et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737–1749. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Writing Group for the CKDPC. Grams M.E., Coresh J., et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria, and adverse outcomes: an individual-participant data meta-analysis. JAMA. 2023;330(13):1266–1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.17002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anavekar N.S., Pfeffer M.A. Cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2004;(92):S11–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hindy G., Tyrrell D.J., Vasbinder A., et al. Increased soluble urokinase plasminogen activator levels modulate monocyte function to promote atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(24) doi: 10.1172/JCI158788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghunathan T.E., Lepkowski J.M., Van Hoewyk J., Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayek S.S., Sever S., Ko Y.A., et al. Soluble urokinase receptor and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1916–1925. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsueh C.H., Chen N.X., Lin S.F., et al. Pathogenesis of arrhythmias in a model of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(12):2812–2821. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsushita K., Ballew S.H., Wang A.Y., Kalyesubula R., Schaeffner E., Agarwal R. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18(11):696–707. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00616-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel R.B., Colangelo L.A., Reis J.P., Lima J.A.C., Shah S.J., Lloyd-Jones D.M. Association of longitudinal trajectory of albuminuria in young adulthood with myocardial structure and function in later life: coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(2):184–192. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wendelboe A.M., Campbell J., Ding K., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in a racially diverse population of Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(6):816–825. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1722189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyamlani G., Molnar M.Z., Lu J.L., Sumida K., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kovesdy C.P. Association of serum albumin level and venous thromboembolic events in a large cohort of patients with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(1):157–164. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerlin B.A., Ayoob R., Smoyer W.E. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of nephrotic syndrome-associated thromboembolic disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):513–520. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10131011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lionaki S., Derebail V.K., Hogan S.L., et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(1):43–51. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04250511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakai N.A., McClure L.A., Judd S.E., et al. Racial and regional differences in venous thromboembolism in the United States in 3 cohorts. Circulation. 2014;129(14):1502–1509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornelissen A., Fuller D.T., Fernandez R., et al. APOL1 genetic variants are associated with increased risk of coronary atherosclerotic plaque rupture in the black population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(7):2201–2214. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lijfering W.M., Rosendaal F.R., Cannegieter S.C. Risk factors for venous thrombosis - current understanding from an epidemiological point of view. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(6):824–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanevold C.D., Lazarchick J., Constantin M.A., Hiott K.L., Orak J.K. Acquired free protein S deficiency in children with steroid resistant nephrosis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1996;26(3):279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdelghani E., Waller A.P., Wolfgang K.J., et al. Exploring the role of antithrombin in nephrotic syndrome-associated hypercoagulopathy: a multi-cohort study and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18(2):234–244. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1, S2; Item S1; Table S1-S6.