Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive form of malignant brain cancer, with a poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of approximately 15%. The malignancy of GBM, including its treatment resistance and high recurrence rate, is largely attributed to the presence of cancer stem cells. Recent studies have identified the N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10), an enzyme responsible for catalyzing N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification in RNA, as a key factor in cancer biology, with diverse roles across multiple cancer types. However, the specific contribution of this RNA modification to the malignancy of GBM remains unexplored. Here, we demonstrate that NAT10 expression is associated with poor prognosis in GBM patients and that NAT10 promotes GBM malignancy by enhancing stemness properties in human GBM cell line U251 and A172. A search for the underlying mechanism of NAT10-mediated enhancement of GBM stemness led to identification of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)-related genes as an epigenetic regulator. NAT10 mediates the acetylation of the coding region of Jumonji and AT-rich Interaction Domain containing 2 (JARID2) mRNA, which results in increased mRNA stability and elevated protein levels. Notably, the knockdown of JARID2 significantly reduced GBM stemness, suppressed tumor growth, and extended the survival of xenograft mice. Our findings suggest that NAT10-mediated acetylation of JARID2 mRNA up-regulates its protein levels, thereby promoting stemness and contributing to the malignancy of GBM. Targeting this NAT10-JARID2 axis may represent a novel therapeutic approach for treatment of GBM.

Keywords: RNA acetylation, NAT10, cancer stem cells, glioblastoma, JARID2

Glioblastoma (GBM) originating from glial cells is the most common malignant brain cancer, classified as grade 4 by the World Health Organization (WHO). The current standard of care for GBM includes surgical resection, when feasible, followed by multidisciplinary treatment consisting of radiotherapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide, a second-generation alkylating agent (1). Conventional treatment for patients with GBM may extend survival; they do not result in a cure (2) largely due to the presence of GBM stem cells. Cancer stem cells possess self-renewal capacity, resistance to therapy, and high invasive potential, with residual cells leading to tumor recurrence. Therefore, eliminating GBM stem cells is crucial for achieving a definitive cure of GBM (3, 4). To achieve this, comprehensive analyses, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (5) and single-cell RNA sequencing analyses (6) have been conducted to identify the mechanisms that sustain GBM stem cells. Although these studies have revealed several underlying mechanisms, effective therapeutics remain elusive.

RNA modifications regulate physiological processes and disease states by modulating mRNA stability and translation efficiency (7), with over 150 types of RNA modifications having been identified (8, 9). These modifications have been closely linked to cancer progression, as exemplified by early mechanistic studies demonstrating that m5C modification in tRNAs is associated with the acquisition of aggressive properties in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells (10). Similarly, m5C modification to GRB2 mRNA causes promotion of tumorigenesis and progression in squamous cell carcinoma (11).

A recent study has identified mRNA acetylation as a novel RNA modification in mammals (12). Acetylation of mRNA at the N4 site of cytidine (ac4C) by N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) stabilizes mRNA and enhances translation efficiency. In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), NAT10 expression is correlated with cellular pluripotency and the maintenance of self-renewal capacity through the acetylation of POU5F1 mRNA (13). Furthermore, mRNA acetylation has been implicated in the malignancy of cancer cells, promoting cell proliferation and collagen synthesis in gastric cancer (14), as well as driving chemoresistance in bladder cancer (15). Although a negative correlation between NAT10 expression and prognosis has also been reported in GBM patients (16), the relationship between NAT10 activity and GBM stemness remains unknown.

Dysregulation of epigenetic modification has been implicated in cancer malignancy. In particular, trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) has been associated with the development of various cancer phenotypes. In fact, H3K27 mutations, which result in the loss of H3K27me3, promote tumor development in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (17). The polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) is the primary writer of H3K27me3 and consists of three core components: enhancer of zeste 1 and 2 (EZH1 and 2), embryonic ectoderm development (EED), and suppressor of zeste 12 homolog (SUZ12). PRC2 is recruited to its methylation sites by interacting with several other proteins, including metal response element binding transcription factor 2 (MTF2), jumonji and AT-rich interaction domain containing 2 (JARID2), AE binding protein 2 (AEBP2), and elongin BC and polycomb repressive complex 2 associated protein (EPOP) (18). Notably, JARID2 plays a crucial role in regulating the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in stem cells by the fine-tuning recruitment of PRC2 to chromatin and its subsequent modification (19, 20, 21). Although JARID2 has also been implicated in the malignant transformation of cancer cells, its role in GBM and its association with cancer stem cells remain unclear.

In this study, we demonstrated that the NAT10 knockout attenuates the malignancy of U251 and A172 cells, a human GBM cell line, through repressing their stemness properties. RNA-seq analysis revealed that NAT10 stabilizes JARID2 mRNA via ac4C modification, leading to up-regulation of JARID2 protein expression. Similarly, knockdown of JARID2 also attenuated the malignancy of U251 and A172 cells by suppressing GBM stemness. Our findings highlight the role of mRNA acetylation by NAT10 in maintaining GBM stemness through JARID2 mRNA stabilization and suggest that targeting this mechanism may provide a novel approach for the treatment of GBM.

Results

Correlation of NAT10 expression with GBM malignancy

To investigate the relationship between NAT10 expression and malignancy of GBM, we explored the mRNA levels of NAT10 in non-tumor brain regions and GBM tissues, as well as the survival time of patients with GBM, using GlioVis, data visualization tools for brain tumor datasets (22) (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/). In the TCGA_GBM datasets, NAT10 mRNA expression was significantly increased in GBM tissues compared to non-tumor brain regions (Fig. 1A left). Higher NAT10 expression in patients with GBM was associated with poorer prognosis (Fig. 1A right). Similar results were also obtained by analyzing the Rembrandt datasets (Fig. 1B). Given the relevance of NAT10 expression levels with prognosis in patients with GBM, we employed the human GBM cell line U251 cells to investigate whether NAT10 regulates GBM malignancy. To achieve this, we prepared NAT10 knockout (KO) U251 cells using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and implanted them subcutaneously into the right back of Balb/c-nude mice. Mice-bearing NAT10 KO U251 cells exhibited significantly prolonged survival and reduced tumor growth compared to those bearing naive U251 cells (Fig. 1C). Additionally, in an orthotopic xenograft model, NAT10 KO also significantly extended survival (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that NAT10 plays a critical role in GBM development and prognosis.

Figure 1.

Relationship between NAT10 expression levels and GBM malignancy. A and B, the data from patients with glioblastoma (GBM) were obtained from the TCGA GBM database (HG-U133 A) (A) and the Rembrandt database (B) and analyzed using GlioVis. Dot plots in each panel show NAT10 mRNA expression levels in GBM tissues and the non-tumor brain region. ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (Mann-Whitney U test). Right graphs show Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with GBM categorized based on NAT10 mRNA expression levels: highest (>75%), higher (75∼50%), lower (50∼25%), lowest (25%>) based on NAT10 mRNA expression levels. ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups (Log-Rank Holm-Sidak test). C, the effect of NAT10 knockout (KO) on the malignancy of U251 cells in the subcutaneous implantation model mice. Naive or NAT10 KO U251 cells were subcutaneously implanted in Balb/c nude mice. The left graph shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves of naive or NAT10 KO U251 tumor-bearing mice (n = 10). The right graph shows the tumor volume for each individual mouse. ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (Log-Rank Holm-Sidak test). D, the effect of NAT10 KO on the malignancy of U251 cells in the orthotopic implantation model mice. Naive or NAT10 KO U251 cells were intracranially implanted into Balb/c nude mice. The data show Kaplan-Meier survival curves of naive or NAT10 KO U251 tumor-bearing mice (n = 10 for Naive, n = 9 for NAT10 KO). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (Log-Rank Holm-Sidak test).

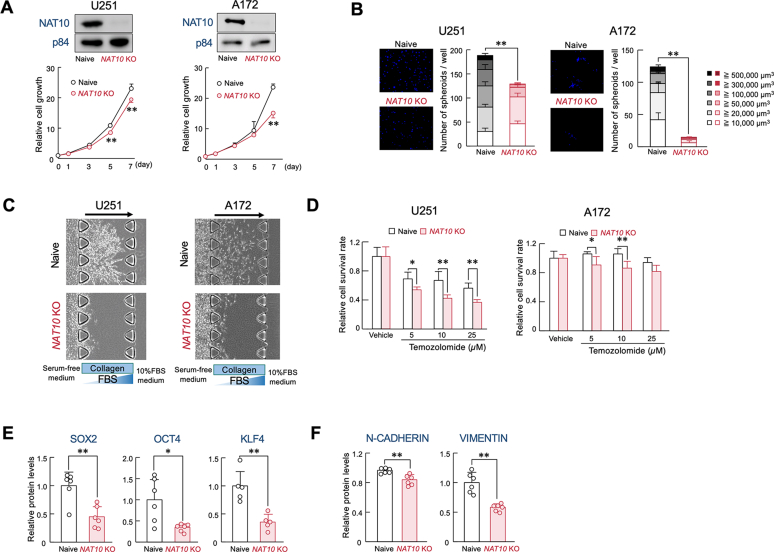

Dysfunction of NAT10 alleviates aggressive properties of GBM cells

To investigate how NAT10 promotes the malignancy of GBM, we investigated the proliferation and stemness properties of NAT10 KO U251 and A172 cells. Although the growth ability of both NAT10 KO U251 and NAT10 KO A172 cells was slightly, but significantly, decreased compared to their respective naive cells (Fig. 2A). By contrast, spheroid formation ability, a hallmark of cancer stemness, was significantly decreased in both KO cells (Fig. 2B). GBM malignancy is also characterized by high invasiveness and chemoresistance (23). To assess the invasive potential of GBM cells, we performed a collagen-based invasion assay using a 3D cell culture chip. In both U251 and A172 cells, invasive potential was decreased by dysfunction of NAT10 (Fig. 2C). Dysfunction of NAT10 also enhanced cytotoxic effects of temozolomide (TMZ), a standard chemotherapeutic agent for GBM, on both cell lines (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that NAT10 contributes to the malignancy of GBM by promoting aggressive traits such as stemness, invasiveness, and chemoresistance. This notion was also supported by the observation that dysfunction of NAT10 decreases the protein expression of key stem cell regulatory factors—SOX2, OCT4, and KLF4 (24, 25)—as well as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, N-CADHERIN and VIMENTIN (Fig. 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

Suppression of GBM stemness by knockout of NAT10. A, the proliferation of naive and NAT10 knockout (KO) U251 and A172 cells. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 12). The cell viability of seeding day (day 0) was set at 1.0. ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference from naive group at corresponding time points. (F9,110 = 69.073 p < 0.001 for U251 cells, F9,110 = 2331.346 p < 0.001 for A172 cells; ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test). Each upper panel shows the NAT10 protein levels in naive and NAT10 KO U251 and A172 cells. B, the spheroid formation ability of naive and NAT10 KO U251 and A172 cells. Each left panel shows a representative photograph of Hoechst33342-stained spheroids-formed by naive or NAT10 KO U251 or A172 cells. Each right panel shows the number of spheroids and the distribution of their diameters. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5 for U251 cells, n = 4 for A172 cells). ∗∗; p < 0.01, significant difference between the two groups (t = 13.355 for U251 cells, t = 2.663 for A172 cells, Welch’s t test). C, the invasion ability of naive and NAT10 KO U251 and A172 cells. Microphotographs show invasion of cells into 3D collagen gel. D, the sensitivity of naive and NAT10 KO U251 and A172 cells to temozolomide. Naive and NAT10 KO cells were treated with indicated concentration of temozolomide for 96 h. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 8 for U251 cells, n = 6 for A172 cells). Cell viability of vehicle-treated groups was set at 1.0. ∗∗; p < 0.01, ∗; p < 0.05; significant difference between the two groups at corresponding concentration points. (F7,56 = 55.596 p < 0.001 for U251 cells, F7,40 = 7.381 p < 0.001 for A172 cells; ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test). E, protein expression levels in SOX2, OCT4, KLF4 in naive or NAT10 KO U251 cells. Protein levels were normalized to those of p84 expression levels. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5–6). ∗∗; p < 0.01, ∗; p < 0.05; significant difference between the two groups (t10 = 4.134 for SOX2, t10 = 3.001 for OCT4, t8 = 4.491 for KLF4, Student’s t test). F, protein expression levels in N-CADHERIN, VIMENTIN in naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells. Protein levels were normalized to those of β-ACTIN expression levels. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 6). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (t10 = 3.979 for N-CADHERIN, t10 = 5.635 for VIMENTIN, Student’s t test).

NAT10 regulates GBM malignancy through regulating JARID2 expression

To assess the changes in the intracellular environment of NAT10 KO U251 cells, pathway and process analysis was performed using the naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells RNA-seq data (Table S1) by Metascape (26). A total of 393 genes were identified as showing greater than two-fold up- or down-regulation in NAT10 KO U251 cells (Table S2). Enrichment analysis revealed that these gene sets were significantly associated with stemness- and differentiation-related terms, such as tissue morphogenesis, embryonic organ development, and stem cell differentiation (Fig. 3A). GBM stemness is maintained not only by the intracellular environment but also by the extracellular stimuli (4, 27). Therefore, we investigated whether extracellular factors are also involved in NAT10-mediated maintenance of GBM stemness. To this end, we performed a spheroid formation assay of naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells under the same culture conditions. The EGFP-expressing naive U251 cells and mCherry-expressing NAT10 KO U251 cells were co-cultured in the same soft agar plate. Even under the same external conditions, spheroid formation of NAT10 KO U251 cells (Fig. S1) suggests that NAT10 contributes to the cancer stemness of GBM without being influenced by extracellular stimuli.

Figure 3.

NAT10 regulates the expression of JARID2 protein in U251 cells. A, pathway and process enrichment analysis was performed using Metascape on 1217 genes that exhibited altered mRNA expression levels due to NAT10 knockout (KO). Each term is represented by a circle node, where the size corresponds to the number of input genes associated with that term, and the color indicates its cluster identity. B, a schematic of diagram illustrates the search for NAT10-regulated genes responsible for stemness of U251 cells, utilizing analysis tools, ChIP-ATLAS and Enrichr. Left panel depicts schematic image of the gene search process. Right panel shows the results of Enrichr analysis using the Wiki_pathway_2021_Human dataset. C, identification of RNA-acetylated genes was performed based on three criteria: the enriched pathways shown in Fig.3B, acetylated genes identified from RedaC:T-seq (GSE162043) and acRIP-seq (GSE102113). D, protein expression levels of MAD1L1, JARID2, SUZ12, and THRAP3 in naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells. Protein levels were normalized to those of p84 expression levels. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5). ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups (t8 = 1.682 for MAD1L1, t8 = 2.686 for JARID2, t8 = 1.384 for SUZ12, t8 = 1.173 for THRAP3, Student’s t test). E, the spheroid formation ability of naive and NAT10 KO U251 GBM cells. The left panel shows a representative photograph Hoechst33342-stained spheroids formed by Mock-transfected naive, NAT10 KO, or JARID2-expressing NAT10 KO U251 cells. The right panel shows the number of spheroids and the distribution of their diameters. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 6). ∗∗; p < 0.01, ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups (Kruskal-Wallis test with Mann-Whitney U test).

To identify the intracellular biological pathways whose gene expressions are under the control of NAT10, we focused on NAT10-regulated 393 genes (Table S2) and conducted the ChIP-Atlas enrichment analysis (28, 29) (https://chip-atlas.org). A variety of transcriptional factors were identified as being under the control of NAT10 (Table S3). In addition, we also performed wiki_pathway analysis using these enriched transcriptional factors (30). The results of pathway analysis revealed regulation of sister chromatid separation at the metaphase-anaphase transition (WP4240) and interaction of polycomb repressive complex 2 (WP2916) were significantly enriched in NAT10 KO U251 cells (Fig. 3B). By integrating the current pathway analysis with NAT10 target genes from previous RNA-seq datasets (GSE162043 for RedaC:T-seq and GSE102113 for acRIP-seq), we identified several candidate genes potentially undergoing acetylation by NAT10, including MAD1L1, a regulator of sister chromatid segregation, and JARID2, SUZ12, and THRAP3, which are associated with PRC2 binding factors (Fig. 3C). Among them, JARID2 protein levels decreased in NAT10 KO U251 cells (Fig. 3D). Consequently, we further focused on this PRC2 component as a key NAT10 target and investigated its function in regulating GBM stemness. To determine whether JARID2 is involved in the regulation of GBM stemness, we prepared JARID2-expressing NAT10 KO U251 cells and conducted spheroid formation assay. The spheroid formation ability of NAT10 KO U251 cells was significantly restored by enhanced expression of JARID2 (Fig. 3E), suggesting that NAT10 contributes to the maintenance of GBM malignancy through regulating JARID2 expression.

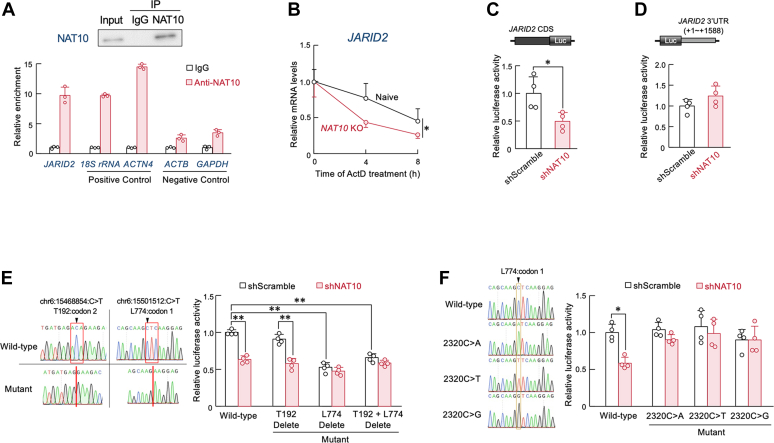

NAT10 stabilizes JARID2 mRNA through ac4C modification

NAT10 is an RNA acetyltransferase that binds to mRNA and catalyzes the acetylation of cytidine residues. To investigate whether NAT10 protein binds to JARID2 mRNA, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation assay using anti-NAT10 antibodies. JARID2 mRNA was co-precipitated with anti-NAT10 antibodies (Fig. 4A). The amount of JARID2 mRNA precipitated with anti-NAT10 antibodies, relative to that with control IgG, was comparable to the levels observed for 18S rRNA and ACTN4 mRNA, both of which have been previously reported to undergo acetylation (31). In contrast, the enrichment levels of ACTB and GAPDH mRNAs—whose cytidine residues are not acetylated by NAT10 (12)—were lower than that of JARID2 mRNA. These results suggest that NAT10 protein interacts with JARID2 mRNA, potentially for cytidine acetylation. NAT10 has been reported to promotes mRNA stability by ac4C modification in the coding sequence (CDS) and 3′-untranslated region (UTR) (12). Therefore, we investigated how NAT10 regulates the expression of JARID2 protein by focusing on its mRNA stability. After treatment of naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells with Actinomycin D (ActD), an inhibitor of RNA synthesis, we assessed JARID2 mRNA levels at 4 h intervals. The stability of JARID2 mRNA was significantly reduced in NAT10 KO U251 cells (Fig. 4B). The half-lives of JARID2 mRNA in naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells were estimated approximately 7.09 h and 4.57 h, respectively.

Figure 4.

NAT10 regulates JARID2 mRNA stability by acetylation of 2320 cytidine residue in JARID2 CDS. A, RNA precipitation (RIP) assay using anti-NAT10 antibodies. Upper panel shows western blotting analysis of NAT10 in immune-precipitates by anti-NAT10 antibodies. Lower graph shows quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of NAT10-RIP using primers listed in Table 1. Values are the mean with S.D. (n = 3). B, difference in the stability of JARID2 mRNA between naive and NAT10 knockout (KO) U251 cells. The mRNA levels were normalized by ATP5E mRNA levels. Basal levels of expression (0 h; the time of the initiation of ActD treatment) was set at 1.0. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 4). ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups. (F1,17 = 5.936, p = 0.026; Two-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test). C, The reporter activity of JARID2 CDS::Luc in U251 cells transfected with shRNA against NAT10. Control cells were transfected with scramble shRNA (shScramble). Schematic diagram of JARID2 CDS::Luc is shown in the top of panels. Values of firefly luciferase activity were normalized to renilla luciferase activity. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 4). ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups (t6 = 3.006, Student’s t test). D, the reporter activity of JARID2 3′-UTR::Luc in U251 cells transfected with shRNA against NAT10. Schematic diagram of JARID2 3′-UTR::Luc is shown in the top of panel. Control cells were transfected with shScramble. Values of firefly luciferase activity were normalized to renilla luciferase activity. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 4). (t6 = 1.670, Student’s t test). E, left panel shows Sanger sequencing of wild-type and mutated (T192 and L774 deletion) JARID2 CDS::Luc. Black arrowheads indicate the NAT10-mediated acetylation site identified from RedaC:T-seq (GSE162043). Right graph shows the reporter activity of wild-type JARID2 CDS::Luc, JARID2 T192 del::Luc, JARID2 L774 Del::Luc, and JARID2 T192 + L774 del::Luc in U251 cells transfected with shRNA against NAT10. Control cells were transfected with scramble shRNA. Luciferase activities of shScramble-transfected cells are set at 1.0. Values of firefly luciferase activity were normalized to renilla luciferase activity and show the mean with S.D. (n = 4). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups. (F7,24 = 46.719, p < 0.001, ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test). F,Left panel shows Sanger sequencing of wild-type and point mutated (2320C > A, T, or G) JARID2 CDS::Luc. Right graph shows the reporter activity of wild-type JARID2 CDS::Luc, JARID2 2320C > A::Luc, JARID2 2320C > T::Luc, and JARID2 2320 C > G::Luc in U251 cells transfected with shRNA against NAT10. Control cells were transfected with scramble shRNA. Luciferase activities of shScramble-transfected cells are set at 1.0. Values of firefly luciferase activity were normalized to renilla luciferase activity and show the mean with S.D. (n = 4). ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups. (F7,24 = 4.357, p = 0.003, ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test).

Next, we explored whether NAT10-mediated stability of JARID2 mRNA is caused by the acetylation of CDS or 3′-UTR. We constructed two reporter vectors. One vector was designed with a luciferase gene inserted downstream of the human JARID2 mRNA CDS (JARID2 CDS::Luc), while other one was designed in which the human JARID2 mRNA a 3′-UTR was inserted downstream of the luciferase gene (JARID2 3′-UTR::Luc). The reporter activity of JARID2 CDS::Luc was significantly decreased by down-regulation of NAT10 (Fig. 4C), but the reporter activity of JARID2 3′-UTR::Luc in NAT10 knockdown cells was comparable to that observed in control cells (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that NAT10 stabilizes the JARID2 mRNA through acetylation of its CDS.

We also searched for NAT10-mediated acetylated cytidine residues (ac4C) on the JARID2 mRNA CDS using RedaC:T-seq dataset (GSE162043). Two ac4C sites were identified within the JARID2 mRNA CDS, located at the codons for the 192nd threonine (T192) and the 774th leucine (L774). Therefore, we constructed reporter vectors in which the codons corresponding to the NAT10-mediated acetylated cytidine residues at positions T192 (JARID2 T192 del::Luc), L774 (JARID2 L774 del::Luc), or both T192 and L774 (JARID2 T192 + L774 del::Luc) were deleted from the JARID2 CDS::Luc vector and subsequently assessed their reporter activity. Deletion of the codons for the T192 cytidine residue had negligible effects on the reporter activity, whereas deletion of codons for the L774 or both T192 and L774 cytidine residues significantly decreased reporter activities (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that NAT10 regulates the JARID2 mRNA stability through cytidine acetylation at the L774 codon. This notion was also supported by the fact that downregulation of NAT10 was unable to further decrease the luciferase activities of JARID2 L774 del::Luc and JARID2 T192 + L774 del::Luc. Furthermore, we introduced point mutations at the cytidine residue (position 2320) within the JARID2 CDS to adenosine, thymidine (uridine), or guanosine, and conducted a luciferase reporter assay using JARID2 CDS-inserted constructs. The reporter activity of the wild-type JARID2 CDS::Luc construct was significantly decreased upon NAT10 knockdown. In contrast, reporter activity of the point mutants—2320C > A, 2320C > T, and 2320C > G—showed little to no change following NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 4F). These findings suggest that NAT10 stabilizes JARID2 mRNA through ac4C modification on the 2320 cytidine residue within JARID2 CDS.

JARID2 is involved in the regulation of GBM malignancy

In the final set of experiments, we investigated whether JARID2 is involved in the regulation of GBM malignancy. Downregulation of JARID2 decreased both the growth and spheroid formation abilities of U251 cells (Fig. 5A left and 5B left). While JARID2 knockdown (KD) had minimal effect on the growth of A172 cells (Fig. 5A right), spheroid formation ability was significantly decreased in JARID2 KD cells (Fig. 5B right). The invasive potential of JARID2 KD U251 cells was attenuated compared to that of control U251 cells (Fig. 5C left). A similar decreased invasive potential was also observed in JARID2 KD A172 cells (Fig. 5C right). These data suggest that JARID2 promotes the aggressive properties of GBM. Consistent with the results, the protein levels of SOX2, OCT4, and KLF4 were decreased in JARID2 KD U251 cells (Fig. 5D). Although the protein levels of N-CADHERIN were increased in JARID2 KD U251 cells, VIMENTIN protein levels were decreased by JARID2 downregulation (Fig. 5E). These results suggest the contribution of JARID2 to the malignancy of GBM, which led us to conduct in vivo experiment with xenograft mouse model. Survival period of JARID2 KD U251 cells-bearing mice significantly prolonged compared to that with control U251 cells-bearing mice. Tumor formation and growth were suppressed in JARID2 KD U251-bearing mice (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these data indicate that GBM malignancy is promoted through the upregulation of JARID2.

Figure 5.

Contribution of JARID2 to the maintenance of stemness properties of GBM cells. A, decrease in the growth ability of U251 and A172 cells by downregulation of JARID2. Each upper panel show JARID2 protein levels in U251 and A172 cells transfected with shRNA against JARID2 or scramble shRNA (shScramble). Each below graph shows the cell viability of seeding day (day 0) was set at 1.0. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 6). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference from shScramble group at corresponding time points. (F9,50 = 1636.125 p < 0.001 for U251 cells, F9,50 = 140.977 p < 0.001 for A172 cells, ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc test). B, the spheroid formation ability of U251 and A172 cells transfected with shRNA against JARID2 or shScramble. Eash left panel shows a representative photograph of Hoechst33342-stained spheroids formed by shScramble- or shJARID2-transfected U251 and A172 cells. Right panel shows the number of spheroids and the distribution of their diameters. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5–6 for U251 cells, n = 8 for A172 cells). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (t = 11.897. for U251 cells, t = 3.412 for A172 cells, Welch’s t test). C, the invasion ability of U251 and A172 cells transfected with shRNA against JARID2 or shScramble. Microphotographs show invasion of cells into 3D collagen gel. D, the protein expression levels of SOX2, OCT4, and KLF4 in U251 cells transfected with shRNA against JARID2 or scramble shRNA (shScramble). Values of protein levels were normalized to p84 protein levels. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (t8 = 3.407 for SOX2, t8 = 12.072 for KLF4, Student’s t test). E, the protein expression levels N-CADHERIN and VIMENTIN in shScramble- or shJARID2-transfected U251 cells. Values of protein levels were normalized to those of β-ACTIN levels. Values show the mean with S.D. (n = 5). ∗∗; p < 0.01 significant difference between the two groups (t8 = 9.389 for N-CADHERIN, t8 = 6.029 for VIMENTIN, Student’s t test). F, decrease in the malignancy of U251 cells by downregulation of JARID2. shScramble or shJARID2 RNA expressing lentivirus transfected U251 cells were subcutaneously implanted in Balb/c-nude mice. Left graph shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves shScramble or shJARID2 RNA expressing lentivirus transfected U251 tumor-bearing mice (n = 7 for shScramble, n = 9 for shJARID2). Right graph shows the tumor volume of each individual mouse. ∗; p < 0.05 significant difference between the two groups (LogRank Holm-Sidak test).

Discussion

NAT10, a multifunctional enzyme, has been recognized as a crucial factor in the complex landscape of cancer biology, with its diverse role in tumorigenesis affecting processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, and genomic stability maintenance (12). In this study, we elucidated the role of NAT10 in enhancing glioblastoma (GBM) stemness by promoting JARID2 expression. Mechanistically, NAT10 acetylates cytidine residues within the coding sequence of JARID2 mRNA, leading to increased mRNA stability and enhanced translational efficiency. This results in the upregulation of JARID2, an epigenetic regulator known to promote stemness properties. Collectively, our findings suggest that NAT10 acts as a key regulator of GBM stemness via RNA epitranscriptomic modification of JARID2 mRNA (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the maintenance of GBM malignancy by NAT10-mediated acetylation of JARID2 mRNA. Upregulation of NAT10 leads to acetylation and subsequent stabilization of JARID2 mRNA. This increased stability enhances JARID2 protein levels, which in turn contributes to the malignant properties of GBM.

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is implicated as a positive regulator to induce the expression of NAT10 in bladder cancer (15). Specifically, p65, a component of NF-κB, binds to the NAT10 promoter region and enhances its transcriptional activity. Indeed, increased expression of RELA mRNA, encoding p65 protein, and the activation of TNF-α-mediated NF-κB signaling are observed in GBM-formed tumor masses (32). We also found a positive correlation between the NAT10 and RELA mRNA expression levels in GBM patients, as revealed by analysis of TCGA_GBM and Rembrandt database (Fig. S2). These facts suggest that the activation of NF-κB signaling, probably due to inflammatory stimuli, contributes to the up-regulation of NAT10 expression in GBM cells.

Ac4C modification is widely observed in the mRNA of human cancer cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that cytidine acetylation in mRNA tends to occur at the third base of the codon (Wobble base). This modification has been shown to enhance mRNA stability and translation efficiency by thermally stabilizing mRNA and tRNA binding (33). Acetylation at the wobble base forms stable wobble base pairs with guanine residues of tRNA anticodons in the ribosome, thereby increasing translation efficiency through stabilization of ribosome binding (12). On the other hand, the NAT10-mediated acetylation site within JARID2 mRNA was identified at the first residue of the 774th leucine rcodon. Although the molecular significance of cytidine acetylation at the first codon remains unclear, reporter assays using a construct in which the coding sequence of JARID2 mRNA was fused upstream of the luciferase gene suggest that acetylation at this site promotes both mRNA stability and JARID2 protein expression. Acetylation of 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR has been demonstrated to decrease translational efficiency and mRNA stability, respectively (14, 31). Therefore, it is plausible that acetylation of the cytidine residue at the first codon of the 774th leucine in the coding region of JARID2 mRNA similarly contributes to enhanced translation efficiency and mRNA stabilization. However, further detailed investigations are required to fully elucidate these mechanisms.

NAT10 enhances the self-renewal capacity by increasing the expression of POU5F1 mRNA through acetylation in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) (13). In contrast, acetylation of POU5F1 mRNA is not observed in human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells (12), indicating that the NAT10 targets different mRNA between normal and cancer cells. NAT10-mediated RNA acetylation has been identified not only in mRNA but also in ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA). The RNA acetylation is not solely mediated by NAT10, but involves interaction with SNORD13, short nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) (34), and THUMP domain-containing protein 1 (THUMPD1) as an adapter (35). The selection of NAT10 target RNAs is also regulated by these adaptors, suggesting that additional, unidentified NAT10-binding proteins may contribute to the specificity of mRNA acetylation. In addition, ac4C modifications within Kozak sequences of 5′-UTR mRNA inhibit canonical start codon recognition and reduce transcript levels (31), while ac4C modification in Gremlin1 mRNA accelerates its degradation (36). Further studies are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms underlying NAT10-mediated mRNA acetylation specificity.

NAT10 also regulates the differentiation of hESCs through modulation of the chromatin landscape via acetylation of acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 B (ANP32 B) mRNA. This study demonstrates that down-regulation of NAT10 increases or decreases the methylation state of the H3K27 in hESCs, probably via mediating by PRC2 (37). JARID2 negatively and positively regulates the recruit region of PRC2 and its methylation activity (38, 39). Consistent with the landscape changes of H3K27me3 by down-regulation of NAT10, JARID2-defective ESCs also alter methylation levels of H3K27 and disrupt the normal regulation of self-renewal and differentiation (40). Therefore, JARID2 may contribute to GBM stemness through regulating PRC recruitment and its histone methylation activity on H3K27. This notion is also supported by the previous findings that JARID2 promotes the invasion ability of lung cancer cells by recruiting PRC2 to the promoter region of EMT-regulatory genes CDH1 and microRNA-200 family (41).

On the other hand, JARID2 also causes deacetylation and methylation of target gene promoters and downregulates several tumor suppressor genes, leading to the promotion of proliferation, invasion, and cancer stemness in breast cancer (42). We observed partial suppression of GBM stemness in U251 cells after treatment with EZH1/2 inhibitor valemetostat (Fig. S3). The suppressive effect of valemetostat on spheroid formation of U251 cells was modest compared to that observed in JARID2-downregulated U251 cells (Fig. 5B left), suggesting, in addition to PRC2-mediated regulation, other mechanisms may also contribute to the regulation of GBM stemness by JARID2. Previous studies have shown that JARID2 enhances the efficiency and kinetics of reprogramming into iPS cells via interactions with PRDM14, ESRRB, and SALL4A, independently of PRC2 (43). Indeed, JARID2 lacking the N-terminus, which is required for interaction with EZH2, retains the ability to induce differentiation genes (44). These results suggest that JARID2 promotes GBM stemness not only through PRC2, but also through other mechanisms. Further investigation is required to elucidate the detailed mechanism of JARID2-mediated enhancement of GBM stemness.

Recent accumulating evidence has demonstrated the involvement of the post-transcriptional modification in promoting tumor aggressiveness (45). Our present findings extend to understanding the role of mRNA acetylation by NAT10 in the maintenance of GBM stemness. The previously unrecognized function of the NAT10-JARID2 cascade in GBM stem cells may provide a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of GBM.

Materials and methods

Cell and treatment

U251 and A172 human glioblastoma cells were purchased from the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (Osaka, Japan). Lenti-X 293T cells were purchased from Takara Bio Inc . U251 and Lenti-X 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco BRL), and A172 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (FUJIFILM Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS (Bioweat) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin solution (FUJIFILM Wako). Cells were maintained at 37oC in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were confirmed that there was no microbial contamination using MycoBlue Mycoplasma Detector (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd). Cells were authenticated by each cell bank using short tandem repeat PCR analysis and were used in less than 3 months from frozen stocks.

Construction of NAT10 knockout U251 and A172 cells

sgRNAs targeting exon 5 of the human NAT10 gene for CRISPR knockout were constructed using the Guide-it single-guide RNA (sgRNA) in Vitro Transcription Kit (Takara). Cells were transfected with the sgRNA and Guide-it Recombinant Cas9 (Electroporation-ready) (Takara) using the NEPA21 electroporator (Nepagene). Cell clones were isolated and expanded in 96-well plates via ultrafiltration.

Construction of mEGFP-, and mCherry2-expressing U251 cells

mEGFP-N1 plasmids (RRID: addgene_54767) and mCherry2-N1 plasmids (RRID: addgene_54517) were obtained from Addgene. The sequences of mEGFP and mCherry2 were subcloned into pLVSIN-CMV Puro (Takara). Lentiviral particles were produced using the Lentiviral High Titer Packing Mix with pLVSIN series (Clonetech) in Lenti-X 293T-cell lines. mEGFP-expressing and mCherry2-expressing lentivirus particles, along with 10 μg/ml of polybrene (Sigma Aldrich), were added to the U251 cell culture medium and incubated for 24 h. Cells transduced with mEGFP-expressing and mCherry2-expressing lentivirus were selected with 5 μg/ml of puromycin.

Construction of JARID2 knockdown U251 and A172 cells

Scramble shRNA (Scramble[shRNA#1]) and JARID2 shRNA (pLV[shRNA]-Puro-U6>hJARID2[shRNA#1]) expressing plasmid were provided by VectorBuilder. Lentiviral particles were generated using the Lentiviral High Titer Packing Mix with pLVSIN series using Lenti-X 293T cell lines. Scramble shRNA and JARID2 shRNA-expressing lentivirus particles, along with 10 μg/ml polybrene, were added to the culture media of U251 and A172 cells and incubated for 24 h. Cells transduced with shScramble and shJARID2 were selected with 5 μg/ml of puromycin.

Determination of the growth ability of cells

Cells were seeded at a density of 2000 cells per well in 100 μl of culture medium in 96-well plates. Cell viability was assessed on Days 1, 3, 5, and 7 post-seeding using the Cell Titer-Glo luminescent cell viability assay kit (Promega). The growth rate was calculated by dividing the change in cell viability from the basal level (Day 0).

Spheroid formation assay

The ability of cells to grow in an anchorage-independent manner was assessed to evaluate the spheroid formation. Cells were seeded in soft agar containing DMEM with 10% FBS at a density of 6.0 × 103 cells per well in a 24-well plate. For co-culture experiments, mEGFP-expressing naive U251 cells and mCherry2-expressing NAT10 knockout U251 cells were seeded in soft agar with DMEM containing 10% FBS at a density of 3.0 × 103 cells each per well in a 24-well plate. On day 10 post-seeding, spheroid formation was evaluated by staining with Hoechst33342 (Dojindo Laboratories). Cells were observed using the KEYENCE all-in-one microscope BZ-X800, and the numbers and size of spheroids were measured by the BZ Analyzer software (KEYENCE).

Invasion assay

Cells were seeded onto a collagen-filled 3D Cell Culture Chip (AIM BIOTECH, Singapore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The culture medium, containing 10% FBS, was replaced every 2 days. On day 14 post-seeding, cells were observed using the KEYENCE all-in-one microscope BZ-X800 (KEYENCE).

Animals and treatments

Male Balb/c-nude mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory Japan (Yokohama, Japan). Mice were housed in groups of 6 to 8 per cage in a light-controlled room (ZT, zeitgeber time; ZT0, lights on, ZT12, lights off) at 24 ± 1°C, with 60 ± 10% humidity, and provided with food and water ad libitum. U251 cells (8.0 × 105 cells) suspended in 10 μl of PBS were implanted subcutaneously into the backs of 6-week-old Balb/c-nude mice under isoflurane anesthesia (Pfizer, New York, NY). U251 cells (1.6 × 106 cells), suspended in 5 μl of PBS, were implanted slowly over a 2 min into the brain (a small hole was drilled in the skull at stereotaxic coordinates: 1.0 mm posterior to the bregma, +2.0 mm mediolateral from the midline and 3.0 mm depth) of 6-week-old Balbc-nude mice under isoflurane anesthesia and fixed on a stereotactic frame using SR-5M-HT (NARISHIGE, Tokyo, Japan). All protocols using mice were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitative real-time RT-PCR, the cDNA equivalent of 10 ng of RNA was amplified by PCR using the LightCycler 96 system (Roche Diagnostics) with THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). Sequences of primers are listed in Table 1. We confirmed no significant amplification of RNA products without reverse transcription. The PCR-amplified products were separated by electrophoresis using 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Signals from the agarose gel were detected using LAS3000 (FUJIFILM).

Table 1.

Primer sets for quantitative RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| Human JARID2 | |

| Forward | 5′-ACCAGTCTAAGGGATTAGGACC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGCTGGGACTATTCGGCTGA-3′ |

| Human 18S rRNA | |

| Forward | 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′ |

| Human ACTN4 | |

| Forward | 5′-GCAGCATGGGCGACTACAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTGAGCCCGTCTCGGAAGT-3′ |

| Human ACTB | |

| Forward | 5′-AAACTGGAACGGTGAAGGTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CGCATCTCATATTTGGAATGACT-3′ |

| Human GAPDH | |

| Forward | 5′-ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC-3′ |

| Human ATP5E | |

| Forward | 5′-GTGGCCTACTGGAGACAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGAGTATCGGATGTAGCTGAGT-3′ |

| Human JARID2 [1.0 kbp] | |

| Forward | 5′-GCTGAACGGACACGTGAAGAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGGTGGTCGTTCTCTGTGTGG-3′ |

Western blotting

Nuclear and cytosolic fractions from U251 cells were prepared by centrifugation. Total protein was extracted using lysis buffer [20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Deoxycholic acid, and 2 mmol/L EDTA]. The extracts were centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4 oC, and the supernatant was collected. Protein extracts were mixed with 2 × sample buffer [250 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% (w/v) SDS, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 10% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue] and denatured at 95 oC for 5 min. Nuclear protein was extracted using cell lysis buffer [150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), 1% (v/v) NP-40, 1 mol/L Hexylene glycol]. The extracts were centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min at 4 oC, and the pellet was washed once with cell lysis buffer. After washing, the pellet was extracted using nuclear lysis buffer [150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 0.5%(w/v) SDS, 1 mol/L Hexylene glycol].

Protein extracts were mixed with 2 × sample buffer and denatured at 95 oC for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were reacted with antibodies against NAT10 (13365-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, RRID:AB_2148944), p84 (THOC1, 10920-1-AP, Proteintech, RRID:AB_2202239), SOX2 (AF2018, R&D systems, RRID:AB_355110), KLF4 (#4038, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2265207), OCT4 (#4038, Cell Signaling Technology), N-CADHERIN (AF6426, R&D systems, RRID:AB_10718850), VIMENTIN (MAB21052, R&D systems, RRID:AB_2832972), SUZ12 (#3737, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2196850), JARID2 (#13594, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2798269), THRAP3 (TRAP150, sc-133250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID:AB_2202901), MAD1L1 (MAD1, 18322-1-AP, Proteintech, RRID:AB_2139251) and β-ACTIN conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID:AB_2202239).

Specific antigen–antibody complexes were visualized using HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (ab97051, Abcam, RRID:AB_10679369), HRP-conjugated anti-goat antibody (sc-2020, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID:AB_631728), HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (ab6820, Abcam, RRID:AB_955438), HRP-conjugated anti-sheep antibody (sc-2770, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID:AB_656968) and ImmunoStar LD (FUJIFILM Wako). Visualized images were scanned using ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare). The band intensity of Western blotting was quantified using Image J (version 1.8.0, NIH) with the “Gel Analysis” function to measure peak areas (46). The obtained data were normalized to the housekeeping protein, β-ACTIN and p84.

Luciferase reporter assay

Reporter vectors were constructed using the pGL4.13 reporter plasmids. The coding region of the human JARID2 mRNA was inserted N-terminal of the luciferase gene (JARID2 CDS::Luc). The 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the human JARID2 mRNA was inserted downstream of the luciferase gene (JARID2 3′-UTR::Luc). Deletions were introduced into the CDS of the human JARID2 gene at the codon for the 192nd threonine (JARID2 T192 del::Luc) and the 774th leucine (JARID2 L774 del::Luc) as well as at both codons simultaneously (JARID2 T192 + L774 del::Luc). Moreover, point mutations were introduced into the cytidine located on 2320 in its CDS for adenosine (JARID2 2320C > A::Luc), for thymidine (Uridine) (JARID2 2320C > T::Luc), and for guanosine (JARID2 2320C > G::Luc).

U251 cells were seeded on 24 well culture plates at 1.0 × 105 per well. Cells were transfected with 300 ng of each reporter construct: JARID2 CDS::Luc, JARID2 T192 del::Luc, JARID2 L774 del::Luc, JARID2 T192 + L774 del::Luc, JARID2 2320C > A::Luc, JARID2 2320C > T::Luc, JARID2 2320C > G::Luc, and JARID2 3′UTR::Luc. A total of 5 ng of phRL-TK vector (Promega) was also transfected as an internal control reporter. Cells were harvested for 24 h post-transfection, and lysates were analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The ratio of fireflies to renilla luciferase activity in each sample served as a measure of normalized luciferase activity.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

Cells were lysed with 1 ml of nuclear isolation buffer [1.28 M sucrose, 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, and 4% Triton X-100]. After the addition of 1 ml of PBS and 3 ml of RNase-free water to lysates, they were centrifuged at 2500×g for 15 min at 4 oC and resuspended nuclear pellet in RIP buffer [150 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40]. The resuspended nuclei were homogenized and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was split into two fractions and was then incubated with anti-NAT10 antibody (13365-1-AP, Proteintech) or normal rabbit IgG (PM035, MBL, Tokyo, Japan) for 2 h at 4 oC with gentle rotation, followed by incubation with protein G magnetic beads (Dynabeads Protein G for IP; Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at 4 oC. Then, the samples were applied magnetic field to pull beads to the side of the tube to remove supernatant and were washed of RIP buffer twice and of PBS once. The beads were used for protein elution while the rest was subjected to RNA extraction using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio Inc.) and quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed as mentioned above.

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted from naive and NAT10 KO U251 cells using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, German). The quality of the extracted total RNA was assessed using Novogene’s quality control (QC) report. mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. After fragmentation, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers followed by the second strand cDNA synthesis. The library was prepared through end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, size selection, amplification, and purification. The quality and quantity of the library were assessed using with Qubit and real-time PCR, while size distribution detection was evaluated with a bioanalyzer. For RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, mRNA sequencing was conducted on the Novaseq 6000 platform (PE150, 6 Gb). Raw reads were processed to remove adaptor contaminants and low-quality bases. The cleaned reads were aligned to Human Genome Reference (GRCh38) using STAR, and uniquely mapped reads were quantified using RSEM with default parameters. Gene expression normalization was calculated as Trancripts per kilobase million (TPM).

Enrichment analysis using ChIP-Atlas

Transcriptional regulatory factors were extracted by enrichment analysis using ChIP-Atlas. We performed on the promoter region (−5000 bp ∼ +100 bp; the distance from the transcription site (+1)) of each gene. Transcriptional regulatory factors with high binding on the altered gene promoters were carried out, as extraction conditions set; Fold enrichment ≧ 1.5 and log Q-value ≦ −1.5.

Statistical and data analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP pro 17 software (SAS Institute). Prior to performing ANOVA, data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances. The comparison of multiple groups was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer post hoc test, or Kruskal-Wallis test with Mann-Whitney U test. The comparison of two groups was analyzed using either Student’s t test, Welch’s t test, or Mann–Whitney U test. The comparison of Kaplan-meier survival curves data was assessed by LogRank Holm-Sidak test. Correlations between continuous variables were evaluated by Pearson correlation analyses. It was considered to be significant if p value was <0.05.

Data availability

All data supporting the results of the present study are included in the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the technical support provided by the Research Support Center, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University.

Author contributions

T. I., A. T., Y. M., S. K., and S. O. conceptualization; T. I., A. T., Y. M., Y. K., Y. Y., and N. M. methodology; T. I., A. T., and S. K. validation; T. I., A. T., and Y. M. formal analysis; T. I., A. T. ,Y. K., and Y. M. investigation; T. I., A. T., Y. M., and S. K. resources; T. I. and A. T. writing–original draft; S. K. and S. O. writing–review & editing; T. I., A. T., and Y. M., visualization; S. K., supervision; S. K., project administration; T. I., A. T., S. K., and S. O. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Challxenging Eploratory Research (22K18375 to S.K.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research A (22H00442 to S.O.), a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (20K21484 and 23K14569 to A.T.), a Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (19K23891, to A.T.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (20K21484 and 23K14569 to A.T.), Fukuoka Public Health Promotion Organization Cancer Research Fund, JST SPRING (Grant Number JPMJSP2136 to T.I.), and the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery, Life Science Research [Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)] from AMED (Grant Number JP25 AM121031), and Robert T. Huang Entrepreneurship Center of Kyushu University.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Paul Shapiro

Contributor Information

Shigehiro Ohdo, Email: ohdo@phar.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Satoru Koyanagi, Email: koyanagi@phar.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Angom R.S., Nakka N.M.R., Bhattacharya S. Advances in glioblastoma therapy: an update on current approaches. Brain. Sci. 2023;13:1536. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13111536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K.D., Ostrom Q.T., Kruchko C., Patil N., Tihan T., Cioffi G., et al. Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics, 2021. CA A Cancer J. Clini. 2021;71:381–406. doi: 10.3322/caac.21693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J., Li Y., Yu T.-S., McKay R.M., Burns D.K., Kernie S.G., et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012;488:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X., Prager B.C., Wu Q., Kim L.J.Y., Gimple R.C., Shi Y., et al. Reciprocal signaling between glioblastoma stem cells and differentiated tumor cells promotes malignant progression. Cell. Stem. Cell. 2018;22:514–528.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins I., Kinnersley B., Ostrom Q.T., Labreche K., Il’yasova D., Armstrong G.N., et al. Transcriptome-wide association study identifies New candidate susceptibility genes for glioma. Cancer. Res. 2019;79:2065–2071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel A.P., Tirosh I., Trombetta J.J., Shalek A.K., Gillespie S.M., Wakimoto H., et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344:1396–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boo S.H., Kim Y.K. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52:400–408. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roundtree I.A., Evans M.E., Pan T., He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begik O., Lucas M.C., Liu H., Ramirez J.M., Mattick J.S., Novoa E.M. Integrative analyses of the RNA modification machinery reveal tissue- and cancer-specific signatures. Genome. Biol. 2020;21:97. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02009-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li P., Wang W., Zhou R., Ding Y., Li X. The m5C methyltransferase NSUN2 promotes codon-dependent oncogenic translation by stabilising tRNA in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Clin. Translational. Med. 2023;13 doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su J., Wu G., Ye Y., Zhang J., Zeng L., Huang X., et al. NSUN2-mediated RNA 5-methylcytosine promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via LIN28B-dependent GRB2 mRNA stabilization. Oncogene. 2021;40:5814–5828. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01978-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arango D., Sturgill D., Alhusaini N., Dillman A.A., Sweet T.J., Hanson G., et al. Acetylation of cytidine in mRNA promotes translation efficiency. Cell. 2018;175:1872–1886.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu R., Wubulikasimu Z., Cai R., Meng F., Cui Q., Zhou Y., et al. NAT10-mediated N4-acetylcytidine mRNA modification regulates self-renewal in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2023;51:8514–8531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Jing Y., Wang Y., Tang J., Zhu X., Jin W.-L., et al. NAT10 promotes gastric cancer metastasis via N4-acetylated COL5A1. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6:173. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie R., Cheng L., Huang M., Huang L., Chen Z., Zhang Q., et al. NAT10 drives cisplatin chemoresistance by enhancing ac4C-associated DNA repair in bladder cancer. Cancer. Res. 2023;83:1666–1683. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mughal A.A., Grieg Z., Skjellegrind H., Fayzullin A., Lamkhannat M., Joel M., et al. Knockdown of NAT12/NAA30 reduces tumorigenic features of glioblastoma-initiating cells. Mol. Cancer. 2015;14:160. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0432-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammad F., Weissmann S., Leblanc B., Pandey D.P., Højfeldt J.W., Comet I., et al. EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for H3K27M-mutant pediatric gliomas. Nat. Med. 2017;23:483–492. doi: 10.1038/nm.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holoch D., Margueron R. Mechanisms regulating PRC2 recruitment and enzymatic activity. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2017;42:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng J.C., Valouev A., Swigut T., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Sidow A., et al. Jarid2/Jumonji coordinates control of PRC2 enzymatic activity and target gene occupancy in pluripotent cells. Cell. 2009;139:1290–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinkel S.A., Galeev R., Flensburg C., Keniry A., Breslin K., Gilan O., et al. Jarid2 regulates hematopoietic stem cell function by acting with polycomb repressive complex 2. Blood. 2015;125:1890–1900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-603969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Y., Xu J.-J., Sun X.-L., Jiang H., Han D.-X., Liu C., et al. Function of JARID2 in bovines during early embryonic development. PeerJ. 2017;5 doi: 10.7717/peerj.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman R.L., Wang Q., Carro A., Verhaak R.G.W., Squatrito M. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:139–141. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke M.F., Dick J.E., Dirks P.B., Eaves C.J., Jamieson C.H.M., Jones D.L., et al. Cancer stem cells—Perspectives on current Status and Future Directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer. Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and Adult Fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Bertoni H., Johnson A., Rui Y., Lal B., Sall S., Malloy M., et al. Sox2 induces glioblastoma cell stemness and tumor propagation by repressing TET2 and deregulating 5hmC and 5mC DNA modifications. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00857-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunaga N., Ogino T., Hara Y., Tanaka T., Koyanagi S., Ohdo S. Optimized Dosing Schedule based on Circadian Dynamics of mouse breast cancer stem cells Improves the Antitumor effects of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase inhibitor. Cancer. Res. 2018;78:3698–3708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oki S., Ohta T., Shioi G., Hatanaka H., Ogasawara O., Okuda Y., et al. ChIP-Atlas: a data-mining suite powered by full integration of public ChIP-seq data. EMBO Rep. 2018;19 doi: 10.15252/embr.201846255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou Z., Ohta T., Oki S. ChIP-Atlas 3.0: a data-mining suite to explore chromosome architecture together with large-scale regulome data. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2024;52:W45–W53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen E.Y., Tan C.M., Kou Y., Duan Q., Wang Z., Meirelles G.V., et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arango D., Sturgill D., Yang R., Kanai T., Bauer P., Roy J., et al. Direct epitranscriptomic regulation of mammalian translation initiation through N4-acetylcytidine. Mol. Cell. 2022;82:2797–2814.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahsan H., Malik S.I., Shah F.A., El-Serehy H.A., Ullah A., Shah Z.A. Celecoxib Suppresses NF-κB p65 (RelA) and TNFα expression signaling in glioblastoma. J. Clin. Med. 2023;12:6683. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson G., Coller J. Codon optimality, bias and usage in translation and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:20–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thalalla Gamage S., Bortolin-Cavaillé M.-L., Link C., Bryson K., Sas-Chen A., Schwartz S., et al. Antisense pairing and SNORD13 structure guide RNA cytidine acetylation. RNA. 2022;28:1582–1596. doi: 10.1261/rna.079254.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma S., Langhendries J.-L., Watzinger P., Kötter P., Entian K.-D., Lafontaine D.L.J. Yeast Kre33 and human NAT10 are conserved 18S rRNA cytosine acetyltransferases that modify tRNAs assisted by the adaptor Tan1/THUMPD1. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2015;43:2242–2258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu Z., Xing X., Huang S., Tu Y. NAT10 promotes Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by mediating N4-acetylcytidine modification of Gremlin 1. Stem. Cells. Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8833527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu Z., Lu Y., Cao J., Lin L., Chen X., Zhou Z., et al. N -acetyltransferase NAT10 controls cell fates via connecting mRNA cytidine acetylation to chromatin signaling. Sci. Adv. 2024;10 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adh9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laugesen A., Højfeldt J.W., Helin K. Role of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) in transcriptional regulation and cancer. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016;6 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pasini D., Cloos P.A.C., Walfridsson J., Olsson L., Bukowski J.-P., Johansen J.V., et al. JARID2 regulates binding of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 to target genes in ES cells. Nature. 2010;464:306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature08788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landeira D., Bagci H., Malinowski A.R., Brown K.E., Soza-Ried J., Feytout A., et al. Jarid2 coordinates Nanog expression and PCP/Wnt signaling required for efficient ESC differentiation and early Embryo development. Cell. Rep. 2015;12:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tange S., Oktyabri D., Terashima M., Ishimura A., Suzuki T. JARID2 is involved in transforming growth factor-Beta-Induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung and Colon cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W., Zeng Y., Hao X., Wang X., Liu J., Gao T., et al. JARID2 coordinates with the NuRD complex to facilitate breast tumorigenesis through response to adipocyte-derived leptin. Cancer. Commun. 2023;43:1117–1142. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iseki H., Nakachi Y., Hishida T., Yamashita-Sugahara Y., Hirasaki M., Ueda A., et al. Combined overexpression of JARID2, PRDM14, ESRRB, and SALL4A dramatically improves efficiency and kinetics of reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem. Cells. 2016;34:322–333. doi: 10.1002/stem.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Raawi D., Jones R., Wijesinghe S., Halsall J., Petric M., Roberts S., et al. A novel form of JARID2 is required for differentiation in lineage-committed cells. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.201798449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbieri I., Kouzarides T. Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20:303–322. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the results of the present study are included in the article.