Abstract

Taurine, the most abundant sulfonic amino acid in humans is largely obtained from diets rich in animal proteins. However, taurine is dietary non-essential because it can be synthesized from cysteine by activation of transsulfuration pathway (TSP) when food consumption is low or if the diet is predominantly plant based. The decline of taurine was proposed as the driver of aging through an undefined mechanism. Here, we found that mild food restriction in humans for one year that resulted in 14% reduction of calorie intake elevated the hypotaurine and taurine concentration in adipose tissue. Therefore, we investigated whether elevated taurine mimics caloric-restriction’s beneficial effects on inflammation, a key mechanism of aging. Interestingly, aging increased the circulating and tissue concentrations of taurine suggesting that elevated taurine may serve as a hormetic stress response metabolite that regulates mechanism of age-related inflammation. The elevated taurine protected mice against mortality from sepsis and inhibited inflammasome-driven inflammation and gasdermin-D (GSDMD) mediated pyroptosis. Mechanistically, ‘danger signals’ including hypotonicity that activate NLRP3-inflammasome, caused upstream taurine efflux from macrophages, which triggered potassium (K+) release and downstream canonical NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, caspase-1 activation, GSDMD cleavage and IL-1β and IL-18 secretion that was reversed by taurine restoration. Notably, taurine does not efflux from GSDMD pore and inhibited IL-1β from macrophages independently of known transporters SLC6A6 and SLC36A1. Increased taurine in old mice promotes healthspan by inducing anti-inflammatory pathways previously linked to youthfulness. These findings demonstrate that taurine is an upstream metabolic sensor of cellular perturbations that control NLRP3 inflammasome and lowers age-related inflammation.

Aging related chronic diseases are linked with increased inflammation that is driven in part by NLRP3 inflammasome activation1–3. The inflammasome-dependent elevation of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 acts on multiple cell types4, including but not limited to neurons5, stem cells6 and adipocytes7–9 leading to functional decline in aging also described as “inflammaging”1–3,10–12. Mangum and Towle proposed a physiological adaptation state termed “enantiostasis”, where despite an unstable internal cellular milieu, the net effect of regulatory flux is stability or tendency towards it13. Thus, to stall precipitous functional decline during aging, enantiostatic endogenous molecules may need to be mobilized to oppose mechanisms that cause instability. Immunometabolic reprogramming induced by calorie restriction(CR)-induced negative balance in humans upregulates protective pathways that restrains inflammaging14 and may control longevity15. The identity of CR-induced enantiostatic metabolites that inhibit mechanism of age-related inflammation remains unknown.

Taurine, the most abundant non synthetic zwitterionic sulfonic amino acid is largely obtained from diets rich in animal proteins with intracellular levels in cells ranging from 5–50mM16,17. However, taurine is dietary non-essential because it can be synthesized from cysteine if diet is taurine deficient18. The restriction of sulfur amino acids that activates the dormant transsulfuration pathway to maintain endogenous cysteine and taurine is linked to longevity in mice19,20. Decline in taurine was recently proposed as the driver of aging process21. Multiple longevity interventions in rodents are associated with upregulation of the transsulfuration pathway (TSP) enzyme cystathionine γ-lyase (CTH)22, which converts cystathionine into cysteine23. Cysteine is also a key precursor for synthesis of taurine; the enzyme cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) converts cysteine into cysteine sulfinate, which is further decarboxylated into hypotaurine by cysteine sulfinate decarboxylase (CSAD). The enzymes of the flavin monooxygenase (FMO) family converts hypotaurine to generate taurine24–26. It is thought that mammals are unable to oxidize the sulfur in taurine or cleave its C-S bond. Thus, taurine is thought to be a final product of cysteine metabolism downstream of TSP and is largely excreted in its biochemically native state or as conjugates with bile acids or xenobiotics for elimination16. Given its zwitterionic nature, taurine is highly water soluble and its concentration in leukocytes is reported to be as high as 20 mM27,28. In addition, taurine is implicated in dampening inflammation and maintenance of cell volume by serving as organic osmolyte29, however the unifying mechanism of taurine’s action on innate immune sensing pathways regulating inflammaging are unknown.

Caloric restriction in humans rewires transsulfuration pathway to elevate taurine

The Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE-II) clinical trial in healthy adults demonstrated that food restriction leading to 14% reduction in caloric intake lowers inflammation14,30. To determine the metabolites that may function as signaling regulators of CR’s anti-inflammatory response, we conducted unbiased metabolomics analyses of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) of participants in the CALERIE-II trial at baseline and one year after CR (Fig. 1a). The top 30 up- and down- regulated metabolites in human adipose tissue revealed that CR in humans is associated with a reduction in cysteine and GSH, but a surprising increase in hypotaurine and taurine, the terminal products of cysteine metabolism in TSP (Fig. 1a). Further pathway analyses revealed that taurine and hypotaurine metabolism were the core pathway upregulated upon 1 year of CR in humans (Fig. 1b, c and Fig. S1a). There was also a trend toward an increase in cysteine sulfinic acid (p = 0.0768), which is synthesized from cysteine by the action of CDO, with no significant change in homocysteine, cystathionine, bisulfite or pyruvate (Fig. S1b, c). Consistent with these data, the RNA sequencing analyses of SAT found increased expression of Csad and Fmo1, the enzymes responsible for generating hypotaurine and taurine (Fig. 1d). Also, similar to Fmo1, CR significantly increased the expression of Fmo2 at year 1 (Fig. 1d), which is previously shown to extend lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans31,32. There was no change in the expression of Cdo1 or major taurine transporter Slc6a6 (Fig. S1d). CR significantly increased the concentration of cystathionine and lowered the redox regulator GSH in blood (Fig. S1e). Notably, the elevation of taurine and hypotaurine were specific to the human adipose tissue as CR did not affect these metabolites in the plasma (Fig. S1f). The CR-induced increase in taurine in adipose tissue was also linked to significant decrease in inflammasome pathway genes Il-18, Asc, Nek7 with a trend in reduction of Nlrp3 (Fig. S1g). Together, these findings demonstrate that chronic mild food restriction in humans reduces cysteine and its product GSH, with an increase in taurine concentration in adipose tissue. These findings suggest that CR-induced activation of transsulfuration pathway (TSP) is associated with lower inflammation and prioritization of metabolic demand that favors synthesis of hypotaurine and taurine downstream of cysteine.

Fig.1. Calorie restriction and aging elevate taurine levels.

(a-c) Unbiased metabolomics analyses of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) of participants in the CALERIA-II trail at baseline and one year after caloric restriction (CR). (a) Volcano plots of the 387 metabolites of SAT from healthy individuals at baseline and 1-year CR. Each dot represents a metabolite identified by LC-MS/MS. The volcano plot shows the fold-change (x-axis) versus the significance (y-axis) of the identified 387 metabolites. The significance (non-adjusted P-value) and the fold change are converted to -Log10(P-value) and log2(Fold-change). The vertical and horizontal dotted lines show the cut-off of fold-change= ±1.0, and of p-value=0.05. 30 significantly regulated metabolites at 1 year of CR compared with baseline were heighted (up-regulated in red, down-regulated in blue (n=14. P<0.05). (b) Schematic summary of the transsulfuration pathway and metabolites from baseline to 1 year CR that were measured in the healthy human SAT. Blue arrows indicate significantly decreasing, pink arrows indicate significantly increasing metabolites and purple lines indicate not significant changes. (c) Changes in the levels of taurine and hypotaurine measured by LC-MS/MS in human SAT after 1 year CR. (Significance was calculated using paired t-test). (d) The RNA-sequencing analyses of SAT of participants in the CALERIA-II trail at baseline and after 1 year CR. The expression level of Csad, Fmo1 and Fmo2 after CR. Paired t-test was performed (n=8). (e) Circulating taurine concentration from serum in young and aged humans (n=17, 28). (f) Taurine level changes prior and 2 days after influenza vaccine immunization in young and aged human serum (young n=17, aged n=28). (g) Serum taurine levels in different ages of male C57BL/6J mice (n=12, 5, 10, 12, Yale rodent colony), mice are littermates. (h) Serum taurine and hypotaurine levels were determined in 2-month-old and 28-month-old male C57BL/6N mice (n=11/10) by LC-MS/MS. (i) Tissues taurine levels in 2-month-old and 28-month-old C57BL/6J male mice (n=10/group), mice are littermates, by taurine assay kit. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Circulating and tissue concentration of taurine increase and doesn’t decline with aging

Since CR increases lifespan and elevates taurine levels, one can posit that aging maybe associated with a decline in taurine in mice and humans. However, in contrast to a recent study that reported reduction of taurine in older adults21, our cross-sectional analyses found that in humans, aging is associated with a significant elevation in taurine concentrations (Fig. 1e). At 2 days after vaccination, the young study participants demonstrated no change while older adults displayed a significant reduction in taurine concentrations (Fig. 1f). Consistent with human data, aged C57BL/6 mice (Yale animal colony) also displayed higher taurine concentrations in serum (Fig. 1g). This was orthogonally validated using metabolomics analyses of sera by LC/MS in a separate cohort of mice (NIA rodent colony) which further confirmed that aging is associated with higher taurine and hypotaurine (Fig. 1h), but lower homocysteine, cystathionine, cysteine sulfinic acid with no changes of cysteine concentration in wild type mice (Fig. S1h). Interestingly, taurine concentration is also high in multiple tissues (Fig. S1i). We found that similar to serum, aging was associated with significant elevation of taurine concentrations in heart, spleen, lung, kidney, liver, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), but not in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and muscle (Fig. 1i, Fig. S1j). These results suggest that aging is not caused by taurine deficiency and that increases of taurine observed post-CR in healthy adults and in older mice and humans could be adaptive hormetic-stress response designed to restore homeostasis.

Upstream taurine efflux in response to danger signals activates the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Given the high mM cellular and tissue concentration of taurine28 and a critical role of macrophages in control of inflammaging, we tested whether taurine controls central mechanisms of inflammation such as the NLRP3 inflammasome. Sensing of multiple ‘danger signals’ such as extracellular ATP33, urate crystals34, ceramides35, oxidized cardiolipin and ectopic DNA from mitochondria36,37 can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome which cleaves caspase-1 to release IL-1β and IL-1838. The unbiased LC/MS metabolomics (Fig. S2a, 2b) revealed that NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages increases glycolytic metabolites39 catalyzed by phosphofructokinase-140, such as fructose 1, 6-biphosphate together with significant reduction in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) (Fig. 2a), a key cofactor in redox reactions41 with no change in cystine (oxidized form of cysteine) and betaine an organic osmolyte in methionine cycle (Fig. 2b, S2c). Interestingly, we found that NLRP3 inflammasome activation caused significant reduction in the concentration of taurine (Fig. 2b) with marked changes in pathways regulating pentose phosphate pathway, arginine and proline and citrulline metabolism (Fig 2a, Fig S2b). Notably, reduction of taurine in NLRP3 inflammasome activated macrophages did not alter GSH and oxidized GSH, suggesting no change in glutathione redox potential (EGSH) (Fig. S2d). The intracellular taurine concentration in murine bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) is approximately 10mM and comparable to taurine rich organs such as heart and muscle (Fig. S2e)27. Interestingly, multiple activators of NLRP3 such as ATP, hypotonicity, monosodium urate crystals (MSU), ceramides, nigericin and imiquimod caused varying degree of taurine efflux (Fig. 2c, Fig. S2f). Further quantification of taurine levels confirmed that extracellular ATP caused rapid and significant efflux of intracellular taurine from macrophages with accumulation in the cell supernatants (Fig. 2d).

Fig.2. Taurine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

(a) Volcano plots of the 290 metabolites identified between the LPS plus ATP challenge group and control group in the bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). Each dot represents a metabolite identified by LC-MS/MS. The volcano plot shows the fold-change (x-axis) versus the significance (y-axis) of the identified 290 metabolites. The significance (non-adjusted p-value) and the fold change are converted to -Log10(p-value) and log2(fold-change). The horizontal dotted lines show the cut-off of fold-change= ±1.0, and of p-value=0.05. 26 significantly regulated metabolites in response to LPS plus ATP treatment compared with baseline were heighted (up-regulated in red, down-regulated in blue (n=3, P<0.05). The right panel is the top 26 discriminating parameters in descending order of importance from the metabolomics data of BMDMs with LPS, ATP treatment and control group. The colored legend on the right indicates the relative abundance of variables, with red and blue indicating high and low values, respectively, while beige illustrates neutral values. (b) Changes in the levels of taurine and L-cystine in response to LPS and ATP stimulation in BMDMs, measured by LC-MS/MS. (c) Taurine efflux was determined in LPS-primed-BMDMs treated with 10 mM ATP, Hypotonic solution (90 mOsmolarity), 10 μM Nigericin for 45 mins, Ceramide 6, MSU for 6 hours and Imiquimod for 2 hours. (d) Intracellular and culture medium taurine levels in BMDMs primed with LPS and stimulated with ATP. (e) Western blots of cell lysates and supernatants from BMDMs stimulated with LPS and ATP and treated with taurine. These results are representative of five independent experiments. (f) ELISA analysis of IL-1β production from BMDMs stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml, 4 hours), followed by ATP (5 mM, 45 min) treatment with or without taurine, MCC950 or KCl. (g) Intracellular taurine level following inflammasome activation in BMDMs supplemented with 100 mM taurine, 10 μM MCC950 or 45 mM KCl. (Representative of three experiments). (h-i) Production of IL-18 and LDH from BMDM stimulated with LPS and ATP and treated with taurine as measured by ELISA (h) and LDH assay (i). (j) Intracellular taurine concentration in LPS-primed BMDMs stimulated by hypotonicity in the presence of sodium chloride. (Representative of three experiments). (k) Western blots of cell lysates and supernatants from BMDMs activated with hypotonic solution in the presence of taurine or NaCl. (Representative of three experiments). (l) Production of IL-1β from BMDMs stimulated with LPS and hypotonic solution and treated with taurine. (m) Intracellular taurine level of LPS-primed BMDMs from control and Nlrp3 deficient mice following ATP or hypotonic treatment supplemented with 10 μM MCC950. (Representative of three experiments). (n) Intracellular taurine concentration in thioglycolate elicited macrophages sorted from peritoneal cavity of mice treated with LPS and ATP. These data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Given an association between taurine efflux and inflammasome activation, we next tested whether elevation of taurine dampens the inflammasome-mediated inflammation in macrophages. Interestingly, restoration of taurine in NLRP3 inflammasome activated macrophages dose-dependently inhibited the IL-1β p17 secretion (Fig. 2e, 2f) and caspase-1 cleavage without affecting the NLRP3 expression (Fig. 2e), with active taurine uptake when taurine was restored (Fig. 2g). Furthermore, the release of IL-18 and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) induced by NLRP3 activation was blocked by taurine in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2h, 2i). In addition to extracellular ATP, we confirmed that taurine also inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to monosodium urate crystals (MSU) (Fig. S2g, S2h) and lipotoxic ceramide (Fig. S2i, S2j).

We next determined how taurine efflux impacts inflammasome activation. It is known that upstream efflux of K+ from macrophages in response to ‘danger signals’ causes the downstream assembly and activation of NLRP3 inflammasome42. Interestingly, taurine efflux in LPS primed and extracellular ATP activated macrophages was not rescued by either restoration of K+ or inhibition of NLRP3 by its structural antagonist MCC95043 (Fig. 2g), suggesting that taurine efflux is an upstream event that activates downstream NLRP3 inflammasome. As expected KCl, MCC950 and taurine restoration in NLRP3 inflammasome activated cells inhibited IL-1β release (Fig. 2f).

Taurine is also known to function as an organic osmolyte to control cell volume21. Notably, the NLRP3 inflammasome can sense alterations in cell osmolarity and resultant changes in cytosolic or membrane integrity44,45. We found that TLR4 primed macrophages exposed to hypotonic stress, a known activator of NLRP3 inflammasome also caused efflux of taurine (Fig. 2j). Interestingly, restoration of isotonicity in media with sodium chloride (NaCl) reversed intracellular taurine concentrations to normal in macrophages (Fig. 2j), suggesting that taurine is a sensor of cytosolic integrity that signals to NLRP3. Consistent with this hypothesis, in LPS primed cells, hypotonicity induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation was inhibited by addition of NaCl that restores isotonicity in media also reverses taurine depletion (Fig. 2j, 2k, 2l). In support of critical role of taurine in defense of cytosolic homeostasis, we found that elevation of taurine in macrophages despite reduced NaCl mediated hypotonic stress, deactivated the NLRP3 mediated caspase-1 cleavage and blocked IL-1β secretion from macrophages (Fig. 2k, 2l).

Consistent with upstream role of taurine in inflammasome regulation, NLRP3 deficiency or its inhibition with small molecule MCC950, did not affect the ATP and hypotonicity-induced taurine efflux from inflammasome primed macrophages (Fig. 2m). We next elicited peritoneal macrophages with thioglycolate treatment in adult mice followed by challenge with LPS and ATP to activate NLRP3 inflammasome. Inflammasome activation in macrophages in vivo also led to taurine efflux (Fig. 2n). Taken together, these results demonstrate that taurine serves as an upstream danger sensor and its efflux in response to hypotonicity and DAMPs, links metabolic-innate immune sensing to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages.

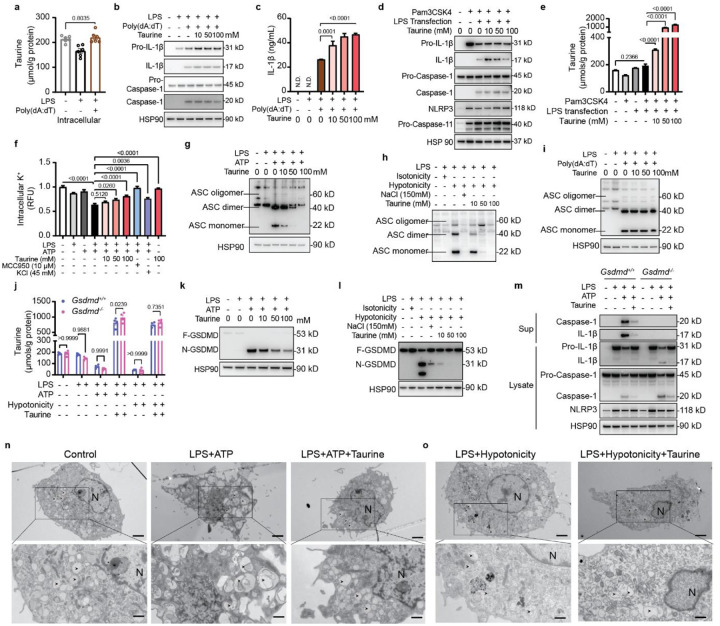

Taurine deactivates canonical NLRP3 inflammasome and gasdermin-D in macrophages

We further investigated the mechanism and specificity of taurine’s anti-inflammatory action mediated via inflammasome deactivation in macrophages. The NLRP3 inflammasome activation also effluxed folic acid from macrophages (Fig. 2a). However, neither folic acid nor amino acids glycine and glutamine that can impact macrophage function affected the IL-1β secretion in response to NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. S2k–m). Moreover, taurine did not affect tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) secretion from macrophages in response to extracellular ATP (Fig. S3a), MSU (Fig. S3b) or C6 Ceramide (Fig. S3c) suggesting specificity. Taurine also did not affect the inflammasome priming step, as it did not inhibit nuclear factor (NF)- κB activation, Erk, P38 or Jnk signaling in response to toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 activation in macrophages (Fig. S3d).

Next, we examined whether taurine could also inhibit the activation of other inflammasome complexes. The non-NLR AIM2 inflammasome was examined by transfecting BMDMs with the dsDNA analog Poly(dA:dT). The AIM2 inflammasome activation with LPS and Poly(dA:dT) did not cause taurine efflux from macrophages (Fig. 3a). Consistent with this, elevation of taurine did not affect caspase-1 cleavage (Fig. 3b), IL-1β (Fig. 3c) or IL-18 (Fig. S3e) from BMDMs in response to AIM2 inflammasome stimulation. In addition, the gram-negative bacteria derived intracellular LPS is sensed by noncanonical pathway that results in caspase-11–dependent pyroptotic cell death and IL-1β production46. We activated caspase-11 in BMDMs primed with the TLR1/2 ligand Pam3CSK4 and transfected with LPS. The treatment of BMDMs with taurine at the same time with LPS transfection has no inhibitory effect on caspase-1 or IL-1β release (Fig. 3d, Fig. S3f) and did not cause taurine efflux (Fig. 3e). In addition, in LPS primed macrophages bacterial flagellin which activates NLRC4 inflammasome, does not affect taurine efflux or IL-1β (p17) (Fig. S3g). These results indicate selectivity of taurine for regulating NLRP3 inflammasome.

Fig. 3. Taurine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and GSDMD activation.

(a-c) LPS-primed BMDMs are transfected with Poly(dA:dT) in the presence of taurine. (a) Intracellular taurine levels of BMDMs. (b) Western blots analyses of IL-1β (p17), caspase-1 (p20) in cell lysates and supernatants of AIM2 inflammasome activated BMDMs. (c) Production of IL-1β from these BMDMs, measured by ELISA. These results are representative of three to five independent experiments. (d) Immunoblots of cell lysates and supernatant from BMDMs stimulated with Pam3CSK4 and transfected with LPS in the presence of taurine. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (e) Intracellular taurine levels of BMDMs primed with Pam3CSK4 and transfected with LPS in the presence of taurine. (f) Quantification of intracellular potassium following inflammasome activation with LPS and ATP in the presence of indicated concentration of taurine. Intracellular potassium was detected by potassium indicator, ION Potassium Green-2 AM. (g) Immunoblot of ASC in cell lysates and cross-linked cytosolic insoluble pellets from BMDMs stimulated with LPS and ATP with taurine. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (h) Western blots detection of ASC oligomerization in cross-linked insoluble pellets from BMDMs activated by hypotonic solution in the presence of taurine or sodium chloride. Results are representative of three experiments. (i) Immunoblot of ASC oligomerization in BMDM stimulated with LPS and transfected with poly(dA:dT) in the presence of taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (j) Intracellular taurine levels in control and Gsdmd−/− BMDMs primed with LPS and treated with ATP, hypotonicity. (k) Immunoblot of cell lysates from BMDM activated by LPS and ATP in presence of taurine. F-GSDMD, full length GSDMD; N-GSDMD, N-terminal GSDMD; C-GSDMD, C-terminal GSDMD. The results are representative of five experiments. (l) Immunblot detection of GSDMD cleavage in BMDM activated by LPS and hypotonicity in presence of taurine. (m) Western blots of IL-1β (p17), caspase-1 (p20) in cell lysates and supernatants of control and Gsdmd−/− BMDMs stimulated with LPS and ATP with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (n-o) Transmission electron micrograph of LPS-primed BMDMs and treated with ATP (n) or hypotonicity (o). (n) Resting macrophages containing autophagosomes with clear membrane structure (left). In response to LPS and ATP stimulation, macrophages containing autophagosomes with apparent remnants of degenerating parts (middle). With taurine addition, autophagosome with clear autophagosome vacuoles (right). (o) Hypotonic solution induced cell swelling in LPS-primed BMDMs (left) and in presence of taurine. Scale bar: 2 μm in lower magnification (1,900 ×); 1 μm in higher magnification (4800 ×). Arrows point to the autophagosome. N, nucleus.

It is known that upstream K+ efflux is a trigger common to many NLRP3 activators42 for inflammasome assembly. Interestingly, we found that taurine dose-dependently prevent K+ efflux triggered by the LPS and ATP (Fig. 3f). To determine the requirement of K+ efflux step in taurine mediated inflammasome regulation, we activated the macrophages with imiquimod, a K+ independent activator of NLRP3 inflammasome47. Notably, taurine inhibited imiquimod induced IL-1β while restoration of K+ with KCl had minor effect on reducing IL-1β (Fig. S4a, S4b). Imiquimod also caused approx. 38% taurine efflux and restoration of taurine inhibited imiquimod induced caspase-1 cleavage (Fig. S4b, S4c). Inhibition of NLRP3 by MCC950 and KCl did not rescue taurine efflux from imiquimod activated macrophages (Fig. S4c). Next, we utilized NLRP3 activator Nigericin which is a specific K+/H+ antiporter. Nigericin which acts specifically at K+ channel to cause K+ efflux causes approx. 20% taurine efflux (Fig. S4d). This efflux of taurine in LPS+Nigericin activated cells was not rescued by MCC950, validating prior results of taurine in upstream regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. S4d). In presence of taurine, nigericin induced caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β release was reduced (Fig S4e, f). In addition to TLR4, taurine also inhibits TLR1/2 stimulator Pam3CSK4 licensed inflammasome activation in response to ATP (Fig. S4g, S4h) and nigericin (Fig. S4i, S4j). These data further suggest a model whereby taurine responds to danger as an upstream event to induce downstream NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. S4k).

Next, we examined NLRP3 inflammasome assembly through formation of NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomers, a key event that nucleates ASC for inflammasome activation3–5. Cytosolic fractions from cell lysates were cross-linked, and ASC monomers and higher order complexes were observed after stimulation with LPS and ATP. Taurine inhibited the ASC-complex formation in response to NLRP3 activation in macrophages (Fig. 3g). Notably, in TLR4 primed macrophages, hypotonicity induced ASC oligomerization was also inhibited by taurine supplementation (Fig. 3h). Confirming specificity, taurine had no effect on AIM2 inflammasome activation (LPS and Poly(dA:dT) induced ASC-complex formation) (Fig. 3i).

Given taurine inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome, we next investigated pyroptosis, a caspase-1 dependent lytic cell death48 that is driven by cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD) and activation of its pore-forming domain49. It is thought that nonselective ion flux through GSDMD pores causes the collapse of the macrophage electrochemical gradient leading to lytic cell death49. However, extracellular ATP and hypotonicity induced taurine efflux is independent of GSDMD pore (Fig. 3j). Consistent with upstream role of taurine in inhibiting NLRP3 induced caspase-1 activation, taurine led to dose dependent inhibition of GSDMD cleavage in macrophages activated by extracellular ATP (Fig. 3k), hypotonic solution (Fig. 3l), urate crystals (Fig. S5a) and ceramide C6 (Fig. S5b). Consistent with no effect on caspase-11 inflammasome, taurine treatment did not impact Pam3CSK-primed and intracellular LPS transfection induced GSDMD cleavage (Fig. S5c). In support of prior results, taurine inhibited GSDMD activation in LPS primed, imiquimod (Fig. S5d) and nigericin (Fig. S5e) activated macrophages. And taurine suppressed TLR1/2 primed, ATP (Fig. S5f) and nigericin (Fig. S5g) activated macrophages. Furthermore, consistent with upstream role of caspase-1 in cleavage of full length GSDMD to N-truncated active GSDMD, taurine’s inhibitory effects on caspase-1 by NLRP3-induced activation was maintained in Gsdmd deficient macrophages which had equivalent increase in caspase-1 cleavage by extracellular ATP (Fig. S5h, Fig. 3m) and hypotonicity (Fig. S5i, S5j).

Given taurine’s strong inhibitory effects on inflammasome and gasdermin-D mediated pyroptosis, we next conducted transmission electron microscopy to determine ultrastructural changes in macrophages activated in response to NLRP3 activators and hypotonicity. Compared to control cells, LPS and ATP treated cells displayed classic features of a pyroptotic activation response, with loss of pseudopodia and accumulation of large fused autophagosomes. Interestingly, taurine protected against the formation of large autophagosomes and pyroptosis (Fig. 3n, Fig. S6). Similarly, hypotonicity- induced cell swelling was reduced in presence of taurine (Fig. 3o, Fig. S7). Further TEM analyses and quantification revealed that taurine maintained mitochondrial structural integrity in inflammasome activated macrophages (Fig. S8a, S8b, S8c). Taken together, these data demonstrate that taurine inhibits NLRP3 activation by acting upstream and blocking K+ efflux, ASC oligomerization, and GSDMD mediated pyroptosis.

Taurine inhibits NLRP3 in models of cryopyrinopathy independently of Slc6a6 and Slc36a1

Missense mutations in NLRP3 cause human systemic inflammatory diseases like familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS) and Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS), which are characterized by overproduction of IL-1β and IL-1850. We tested the efficiency of taurine in BMDMs with Nlrp3 mutations (L351P and A350V) corresponding to the human NLRP3 gain-of-function mutations (L353P and A352V), resulting in human FCAS and MWS respectively, rendering the inflammasome constitutively active without the requirement of NLRP3 ligands50. In mouse macrophages with FCAS mutation that renders NLRP3 constitutively active, taurine blocked the processing of both IL-1β and caspase-1 (Fig. 4a, 4b). The GSDMD cleavage was inhibited in the presence of taurine in response to LPS in FCAS BMDMs (Fig. 4c). Similarly, taurine can also suppress IL-1β release (Fig. 4d), caspase-1 processing (Fig. 4e) and GSDMD activation (Fig. 4f) in TLR4 primed mouse macrophages with the Nlrp3 mutation that mimics MWS (Fig. 4d–f). These data suggest that elevation of taurine in macrophages inhibits intrinsic NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in disease models of cryopyrinopathies.

Fig. 4. Taurine inhibits NLRP3 in disease models of cryopyrinopathies independently of Slc6a6 or Slc36a1 transporters.

(a-c) BMDMs from Nlrp3L351P mice. (a) IL-1β production from these BMDMs stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine as measured by ELISA. These data are representative of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. (b) Western blots of IL-1β (p17), caspase-1 (p20) in cell lysates and supernatants from BMDMs stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Immunoblot analysis of GSDMD cleavage in cell lysates from BMDM stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (d-f) BMDMs from Nlrp3A350V mice. (d) IL-1β production from BMDMs stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine. These data are representative of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. (e) Western blots of IL-1β (p17), caspase-1 (p20) in BMDMs stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (f) Western blot analyses of GSDMD cleavage in BMDM stimulated with LPS and treated with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (g) qPCR analysis of genes encoding key proteins involved in taurine uptake and synthesis in BMDMs (n=5–6). (h-i) Western blot analyses of IL-1β (p17), caspase-1 (p20) (h) and GSDMD (i) from control and Slc6a6−/− BMDMs stimulated with LPS and ATP and treated with taurine. These results are representative of three independent experiments. (j) Intracellular taurine levels in control and Slc6a6−/− BMDMs activated by LPS and ATP and treated with taurine. (k-l) IL-1β production (k) and GSDMD cleavage (l) in control and Slc6a6−/− BMDMs stimulated with LPS and hypotonicity and treated with taurine. These data are representative of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. (m and n) 10- to 11-week-old littermate Slc6a6+/+ and Slc6a6−/− mice were pretreated with taurine (1000 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle control for 5 days, then given LPS i.p. injection, 4 hours later blood and liver were analyzed (n=17,16,14,14). (m) Taurine levels of the liver from the mice. (n) Serum levels of IL-1β from these mice. (o and p) 13- to 14-week-old littermate Slc6a6flox/floxLysMCre− or Slc6a6flox/floxLysMCre+ mice were pre-treated with taurine (1000 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle control for 5 days, IL-1β was quantified in blood and liver 4 h post LPS challenge (n=12,12,10,10). Taurine levels in livers (o) and serum IL-1β levels (p) of control and myeloid specific Slc6a6 deficient mice. (q) Production of IL-1β from Cth+/+ and Cth−/− BMDMs stimulated with LPS and ATP and treated with taurine. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate.

Taurine is zwitterionic and its high concentration in specific cells could be due to either synthesis downstream of cysteine or by active import via canonical transporters Slc6a6 and Slc36a151. We found that murine BMDMs had low expression of Cdo1, Csad with undetectable expression of Fmo1 and Fmo2 (Fig. 4g). In contrast, BMDM had high expression of taurine transporter Slc6a6 compared to Slc36a1 (Fig. 4g). As Slc6a6 is reported to be the main taurine transporter in cells52,53, we reasoned that Slc6a6 might transport taurine in macrophages. Genetic ablation of Slc6a6 led to about 80% depletion of the taurine in serum (Fig. S9a). However, the Slc6a6−/− BMDMs treated with taurine showed comparable IL-1β (Fig. S9b), caspase-1 (Fig. 4h) and GSDMD cleavage (Fig. 4i) in response to LPS and ATP treatment. Furthermore, taurine caused a dose-dependent reduction of LDH release (Fig. S9c) in Slc6a6−/− macrophages. Compared to control cells, the Slc6a6 deficient macrophages displayed equivalent reduction of ASC oligomerization (Fig. S9d) in response to taurine. Furthermore, the Slc6a6 deficient macrophages showed efficient taurine efflux and import upon NLRP3 activation (Fig. 4j). Taurine also inhibited the hypotonicity induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 4k, Fig. S9e) and GSDMD cleavage (Fig. 4l) independently of Slc6a6, since the deficiency of Slc6a6 has no effect on intracellular taurine uptake (Fig. S9f). We next silenced Slc36a1 (Pat1) in BMDM to investigate the potential role of this transporter in taurine’s effects on macrophage biology (Fig. S9g). Compared to Slc6a6, alternate taurine transporter Slc36a1 has low mRNA and protein expression in BMDMs (Fig. 4g, Fig. S9h, S9i). Taurine significantly and equivalently inhibited IL-1β release in both control and Slc36a1 silenced BMDMs (Fig. S9j). To rule out potential compensation of one transporter, we created Slc6a6 and Slc36a1 double deficient BMDMs. Interestingly, compared to control BMDMs, taurine equivalently inhibited LPS and ATP induced IL-1β secretion in BMDMs lacking both canonical taurine transporters Slc6a6 and Slc36a1 (Fig. S9k). The livers of Slc6a6 deficient mice treated with LPS displayed lower baseline taurine (Fig. 4m) but with equivalent reduction of IL-1β by taurine treatment (Fig. 4n). Given inflammasome activation requires TLR priming, there was no spontaneous activation of NLRP3 in Slc6a6 deficient mice with lower baseline taurine. We next conditionally ablated Slc6a6 in myeloid cells and found no significant change in taurine levels in liver (Fig. 4o) and both control littermates and LysMCre:Slca6fl/fl mice had equivalent reduction of serum IL-1β upon taurine supplement in response to LPS challenge (Fig. 4p) validating our results from in vitro cell model.

The enzyme cystathionine-γ lyase (CTH) mediates the critical rate limiting step in TSP downstream of cysteine to generate taurine (Fig. 1b)16. Given our finding that CR induced elevation of taurine is associated with reduction of cysteine despite an increase in Cth expression (Fig. 1a, 1b), we investigated the role of CTH in taurine’s effect on macrophages. When compared control to Cth deficient macrophages, taurine similarly inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome dependent caspase-1 cleavage (Fig. S9l) and IL-1β secretion (Fig. 4q). Consistent with our data that inflammasome activation does not change oxidized cystine or GSH in macrophages (Fig. 2b, Fig. S2d), taurine inhibited IL-1β (Fig. S9m), caspase-1 and GSDMD activation in macrophages independently of redox regulator NRF2 (Fig. S9n). This suggest that inflammasome deactivation is independent of taurine synthesis and taurine uptake from media is sufficient to inhibit caspase-1 cleavage, IL-1β release and GSDMD mediated pyroptosis in macrophages without the requirement of canonical transporters Slc6a6 and Slc36a1.

Elevation of taurine inhibits inflammaging in mice and enhances healthspan

We next investigated the effects of taurine on inflammation in vivo. Adult mice were pre-treated for 7 days with taurine and were assessed 4 hours after LPS challenge (Fig. 5a). Pretreatment with taurine significantly reduced serum concentrations of IL-1β, TNFα and MCP-1 (Fig. 5a) without affecting IL-6 (Fig. S10a). Unlike LPS, urate crystals specifically activate NLRP3. We found that taurine treatment resulted in the decreased production of GRO- α/KC and MCP-1 (Fig. S10b) but not TNF-α or IL-6 (Fig. S10c) in response to in vivo challenge with MSU crystals. Taurine also inhibited LPS induced IL-1β concentration in female mice (Fig. 5b). Acute administration of taurine (4 hours) in LPS+ATP treated mice also reduced IL-1β in adult mice (Fig. 5c) without affecting the body weight (Fig. 5d). We next administered lethal dose of LPS to mice to induce inflammation and sepsis. Interestingly consistent with its anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, the taurine treatment significantly reduced endotoxemia induced mortality in adult mice (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5. Elevation of taurine inhibits NLRP3-inflammaging and enhances healthspan.

(a) 8- to 9-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were intraperitoneally injected with taurine at 500 mg/kg body weight or vehicle control for 7 days and then give i.p. LPS injection. 4 hours later, serum levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and MCP-1 were measured by ELISA (n=3, 8, 4, 9) (b)10- to 11-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were i.p. injected with taurine at 1000 mg/kg body weight or vehicle control for 5 days, and then mice were given i.p. LPS injection for 4 hours. Serum IL-1β was measured by ELISA (n=11, 9). (c and d) 13-week-old C57BL/6J male mice pretreated with taurine (1000 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle control for 5 days, then mice were given LPS for 4 hours followed by ATP treatment for 15 mins (n=6,6,10,10). (c) Levels of IL-1β of the serum and peritoneal lavage were measured by ELISA. (d) body weight changes of these mice. (e) Survival curves of 10- to 11-week-old C57BL/6J male mice pretreated with PBS or Taurine (1000 mg/kg body weight) for 5 days followed by LPS i.p. injection (n=12,15). (f-m) Aged male C57BL/6N mice (20-month-old) given normal water or drinking water with taurine (8,000 mg/kg/day, 4% in water (w/v)) for 4 months. (f) Serum taurine (n=11,8) levels after 4 months of oral taurine treatment. (g) Glucose tolerance test (GTT) and area of the curve (A.O.C.) of mice for 3 months taurine treatment (n=14, 15). (h and i) Rotarod (h) and Grip-strength (i) tests of mice after 3 month of taurine treatment (n=15, 15). (j) UMAP visualizations of the scRNA-sequencing data from stromal vascular faction (SVF) cells of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) in these old mice (n=10, 8 pooled). Identified cells colored by treatment condition (left). Proportions and annotation of selected cell types in control versus taurine treated condition (right). (k) The mouse hallmark gene set enrichment analysis for down-regulated genes in taurine treated group across cell types. Color represents minus log10 adjusted p-values. (l) Dot plots showing significantly up/down-regulated genes (n=10 each) in taurine-treated group versus control group for macrophages, ASPCs and mesothelial cells. The dot colors indicate the log fold changes. Dot sizes indicate the fraction of cells that express the genes. (m) Serum levels of IL-1β and liver levels of IL-1β, IL-18 and IL-6 from mice treated with taurine for 4 months (n=9, 8). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Given taurine levels increase with age and inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome, we next investigated the mechanism of taurine in control of age-related inflammation. The 20-month-old C57BL/6 mice were treated with taurine in drinking water for 4 months and evaluated for measures of healthspan and inflammation. Taurine treatment doubled taurine concentrations in the serum (Fig. 5f) and liver of old mice (Fig. S10d). Taurine supplementation reduced the body weight and fat mass of old mice without affecting the lean mass (Fig. S10e, S10f). Consistent with lower body weight, the old mice treated with taurine had significant improvements in the glucose homeostasis (Fig. 5g). Notably, taurine also improved rotarod test and grip strength, which suggested enhanced balance, motor coordination and reduced frailty, which are important indicators of healthspan (Fig. 5h, 5i).

To determine the mechanism of taurine’s anti-inflammaging effects, we conducted single-cell RNA (sc-RNA) sequencing of stromal vascular fraction cells isolated from visceral adipose tissue (VAT) of old mice that were supplemented with taurine. The uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) unbiased clustering revealed 16 distinct cell populations including adaptive, innate immune cells and mesothelial cells (Fig. 5j). Comparison of sham with taurine groups revealed few changes in cellular composition including no change in adipose progenitor cells (ASPCs), macrophages or T cell except reduction in B cells, which are known to increase in VAT of aged WT mice12 (Fig. 5j, Fig. S10g). The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) analyses within ASPC, macrophages and mesothelial cells displayed significant downregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α signaling, interferon-response and IL-6 signaling and complement cascade (Fig. 5k). The taurine induced top up and down regulated genes in ASPCs, macrophages and mesothelial cells displayed common gene-regulation hubs such as upregulation of Uba52 and Cmss1 and inhibition of β2 microglobulin (B2m) expression (Fig. 5l, Fig. S10h). Previous studies have shown that increase of B2M, a component of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, is a pro-aging factor that is linked to inflammation and cognitive decline in old mice54. Collectively, these data suggested that taurine downregulates major pro-inflammatory pathways in aged mice. To confirm this, we performed cytokines detection in serum and liver tissues in these aged mice. Compared to sham-treated mice, supplementation of taurine significantly decreased the concentrations of IL-1β (both serum and liver), IL-18 and IL-6 (liver) (Fig. 5m), the pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive inflammaging. Taurine also has an inhibitory trend in IL-18 in the serum without affecting Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and eotaxin (Fig. S10i). Collectively these data demonstrate that taurine downregulates NLRP3 inflammasome and major pro-inflammatory pathways in aged mice.

Discussion

Activation of TSP pathway, that generates cysteine and culminates in production of GSH and taurine has previously been associated with pro-longevity interventions22,55. In addition, taurine has been linked to protection from inflammation in SARS-COV2 infection and reduces oxidative stress56,57. In older adults, chronic inflammation contributes to loss of organ function and development of aging-associated diseases1–3. Our findings indicate that CR-induced upregulation of taurine in humans is an adaptive mechanism to control inflammation. Reduction of taurine was reported to be a driver of aging, and daily gavage of old mice for approximately two years with taurine enhanced lifespan21. Our data demonstrate that taurine concentrations do not decline and instead increase in older humans and mice. The reasons for the difference in findings are unclear, one possibility is that taurine is also present in high concentrations in red blood cells, leukocytes, so that hemolyzed plasma or serum or contamination with degranulated platelets or other cells could influence taurine measurements. Our sample sets were carefully evaluated for this potential confounder, and we can rule out that increased taurine is a result of cell contamination. It has been known that taurine levels increase in response to osmolar imbalance, thirst or increased hypertonicity16. Notably, aging is associated with reduced thirst58, which can induce negative water balance and lead to adaptive increase in organic osmolytes such as taurine. Indeed, using isotope-tracking 2H methods that quantifies water turnover through measurement of hydrogen isotope dilution and elimination, aging in humans was found to be associated with reduced water turnover59. Thus, the observed age-related increase in taurine could also represent an adaptive compensatory response to maintain osmolar balance.

Our findings that inflammasome activation causes taurine efflux in macrophages and pyroptosis is consistent with prior reports of swelling-evoked taurine release in the brain, including astrocytes and neurons60,61. In addition, metabolomics identified greater taurine efflux in macrophages undergoing pyroptosis than apoptosis62. Our results provide direct evidence that taurine efflux acts as an upstream sensor of DAMPs that activates downstream NLRP3 inflammasome in TLR primed macrophages. Taurine did not affect the priming step, its efflux induces K+ release, ASC oligomerization, caspase-1 activation and GSDMD cleavage. Taurine was active against the hypersensitive Nlrp3 mutations associated with FCAS and MWS, and against canonical NLRP3 stimuli without impacting AIM2, NLRC4 or caspase-11 inflammasomes. Taurine functions in mM ranges in multiple organs and upon efflux by NLRP3 activating DAMPS while 10–50 mM supplementation effectively inhibits the inflammasome. Thus, unlike endocrine hormones or a distally produced metabolite that have to be secreted in blood to produce an effector response, taurine’s mM cellular and local concentrations likely operate in autocrine/paracrine fashion without undergoing the dilution effect in blood. Consistent with Mangum and Towle’s hypothesis, elevation of taurine may serve as an enantiostatic metabolite that opposes inflammaging to maintain biological function despite perturbation of internal milieu.

Given its low lipophilicity, taurine is impermeable across plasma membrane and high levels of cellular taurine are maintained by synthesis and transport via Slc6a6. Our studies performed in Cth−/− macrophages have shown that synthesized taurine has no effect on NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Surprisingly, canonical taurine transporters were not required for anti-inflammasome effect in macrophages as both the global and myeloid cell specific Slc6a6 deficient mice had a similar anti-inflammatory response to taurine upon LPS challenge and NLRP3 activation. Interestingly, macrophages can take up intact mitochondria and multiple cellular components including exosomes via unknown mechanisms63. It has been shown that taurine can boost cellular uptake of small D-peptides by endocytosis or trogocytosis64. In some condition, uptake of taurine appeared to be non-saturable and possibly due to diffusion65. Our data suggest that additional mechanisms are required for taurine uptake in macrophages and future studies are required to determine the transport and efflux mechanism.

One to two years of mild food restriction leading to reduced calorie intake in healthy adults in CALERIE-II clinical trial helped highlight the transsulfuration pathways (TSP), which is typically dormant in fed conditions with adequate protein intake. This is likely because reduction of food consumption is associated with proportional decrease in protein intake and humans prioritize production of sulfonic amino acid taurine by rewiring cysteine metabolism in TSP. Upon exposure to NLRP3 activating ‘danger signals’ taurine efflux allows downstream NLRP3 inflammasome assembly while elevation of taurine inhibits NLRP3 driven inflammation and inflammaging. In summary, we demonstrate that elevation of taurine in aging and CR-induced metabolic stress maybe an adaptive mechanism to restore homeostasis. Our studies suggest that elevation of taurine inhibits age-related inflammation by serving as a metabolic osmosensor that protects against NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all investigators and staff involved in coordinating and executing CALERIE-II clinical trial. We also thank to Genentech for providing anti-Caspase-1 antibody. SR is a recipient of American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) postdoctoral fellowship. The research in Dixit Lab was supported in part by NIH grants AG031797, AG045712, P01AG051459, AR070811, and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (CAF).

References

- 1.Camell C. D. et al. Inflammasome-driven catecholamine catabolism in macrophages blunts lipolysis during ageing. Nature 550, 119–123, doi: 10.1038/nature24022 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youm Y. H. et al. Canonical Nlrp3 inflammasome links systemic low-grade inflammation to functional decline in aging. Cell Metab 18, 519–532, doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.010 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latz E. & Duewell P. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammaging. Semin Immunol 40, 61–73, doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.09.001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes M. M. & O’Neill L. A. J. Metabolic regulation of NLRP3. Immunol Rev 281, 88–98, doi: 10.1111/imr.12608 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venegas C. et al. Microglia-derived ASC specks cross-seed amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 552, 355–361, doi: 10.1038/nature25158 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell C. A. et al. Stromal niche inflammation mediated by IL-1 signalling is a targetable driver of haematopoietic ageing. Nat Cell Biol 25, 30–41, doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-01053-0 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stienstra R. et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 15324–15329, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen H., Ting J. P. & O’Neill L. A. A role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in metabolic diseases--did Warburg miss inflammation? Nat Immunol 13, 352–357, doi: 10.1038/ni.2228 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandanmagsar B. et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med 17, 179–188, doi: 10.1038/nm.2279 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin-Aguilar F. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome suppression improves longevity and prevents cardiac aging in male mice. Aging Cell 19, e13050, doi: 10.1111/acel.13050 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauernfeind F., Niepmann S., Knolle P. A. & Hornung V. Aging-Associated TNF Production Primes Inflammasome Activation and NLRP3-Related Metabolic Disturbances. J Immunol 197, 2900–2908, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501336 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camell C. D. et al. Aging Induces an Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Dependent Expansion of Adipose B Cells That Impairs Metabolic Homeostasis. Cell Metab 30, 1024–1039 e1026, doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangum C. & Towle D. Physiological adaptation to unstable environments. Am Sci 65, 67–75 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spadaro O. et al. Caloric restriction in humans reveals immunometabolic regulators of health span. Science 375, 671–677, doi: 10.1126/science.abg7292 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speakman J. R. & Mitchell S. E. Caloric restriction. Mol Aspects Med 32, 159–221, doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.07.001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huxtable R. J. Physiological Actions of Taurine. Physiological Reviews 72, 101–163, doi:DOI 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana S. K. & Sanders T. A. Taurine concentrations in the diet, plasma, urine and breast milk of vegans compared with omnivores. Br J Nutr 56, 17–27, doi: 10.1079/bjn19860082 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brand A., Leibfritz D., Hamprecht B. & Dringen R. Metabolism of cysteine in astroglial cells: synthesis of hypotaurine and taurine. J Neurochem 71, 827–832, doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020827.x (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyshkovskiy A. et al. Identification and Application of Gene Expression Signatures Associated with Lifespan Extension. Cell Metab 30, 573–593 e578, doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.018 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uthus E. O. & Brown-Borg H. M. Methionine flux to transsulfuration is enhanced in the long living Ames dwarf mouse. Mech Ageing Dev 127, 444–450, doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.001 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh P. et al. Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging. Science 380, eabn9257, doi: 10.1126/science.abn9257 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyshkovskiy A. et al. Distinct longevity mechanisms across and within species and their association with aging. Cell 186, 2929-+, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.002 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao A. M., Drake M. R. & Stipanuk M. H. Role of the transsulfuration pathway and of gamma-cystathionase activity in the formation of cysteine and sulfate from methionine in rat hepatocytes. J Nutr 120, 837–845, doi: 10.1093/jn/120.8.837 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remy A., Henry S. & Tappaz M. Specific antiserum and monoclonal antibodies against the taurine biosynthesis enzyme cysteine sulfinate decarboxylase: identity of brain and liver enzyme. J Neurochem 54, 870–879, doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02332.x (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misra C. H. & Olney J. W. Cysteine oxidase in brain. Brain Res 97, 117–126, doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90918-x (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veeravalli S. et al. Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 1 Catalyzes the Production of Taurine from Hypotaurine. Drug Metab Dispos 48, 378–385, doi: 10.1124/dmd.119.089995 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grisham M. B., Jefferson M. M., Melton D. F. & Thomas E. L. Chlorination of endogenous amines by isolated neutrophils. Ammonia-dependent bactericidal, cytotoxic, and cytolytic activities of the chloramines. J Biol Chem 259, 10404–10413 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Learn D. B., Fried V. A. & Thomas E. L. Taurine and Hypotaurine Content of Human-Leukocytes. J Leukocyte Biol 48, 174–182, doi:DOI 10.1002/jlb.48.2.174 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warskulat U., Zhang F. & Haussinger D. Taurine is an osmolyte in rat liver macrophages (Kupffer cells). J Hepatol 26, 1340–1347, doi:Doi 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80470-9 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraus W. E. et al. 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endo 7, 673–683, doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30151-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi H. S. et al. FMO rewires metabolism to promote longevity through tryptophan and one carbon metabolism in C. elegans. Nat Commun 14, 562, doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36181-0 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leiser S. F. et al. Cell nonautonomous activation of flavin-containing monooxygenase promotes longevity and health span. Science 350, 1375–1378, doi: 10.1126/science.aac9257 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mariathasan S. et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature 430, 213–218, doi: 10.1038/nature02664 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinon F., Petrilli V., Mayor A., Tardivel A. & Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440, 237–241, doi: 10.1038/nature04516 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youm Y. H. et al. The Nlrp3 inflammasome promotes age-related thymic demise and immunosenescence. Cell Rep 1, 56–68, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.11.005 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iyer S. S. et al. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 39, 311–323, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xian H. & Karin M. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA: a protective signal gone awry. Trends Immunol 44, 188–200, doi: 10.1016/j.it.2023.01.006 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnett K. C., Li S., Liang K. & Ting J. P. A 360 degrees view of the inflammasome: Mechanisms of activation, cell death, and diseases. Cell 186, 2288–2312, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.04.025 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills E. L. et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase Supports Metabolic Repurposing of Mitochondria to Drive Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell 167, 457–470 e413, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amara N. et al. Selective activation of PFKL suppresses the phagocytic oxidative burst. Cell 184, 4480–4494 e4415, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shim D. W. et al. Intracellular NAD(+) Depletion Confers a Priming Signal for NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Front Immunol 12, 765477, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.765477 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munoz-Planillo R. et al. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 38, 1142–1153, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coll R. C. et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nature Medicine 21, 248-+, doi: 10.1038/nm.3806 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Compan V. et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 37, 487–500, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.013 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ip W. K. & Medzhitov R. Macrophages monitor tissue osmolarity and induce inflammatory response through NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 6, 6931, doi: 10.1038/ncomms7931 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kayagaki N. et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117–121, doi: 10.1038/nature10558 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross C. J. et al. K. Efflux-Independent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Small Molecules Targeting Mitochondria. Immunity 45, 761–773, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.010 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kesavardhana S., Malireddi R. K. S. & Kanneganti T. D. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu Rev Immunol 38, 567–595, doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-073119-095439 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton K., Dixit V. M. & Kayagaki N. Dying cells fan the flames of inflammation. Science 374, 1076–1080, doi: 10.1126/science.abi5934 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brydges S. D. et al. Inflammasome-mediated disease animal models reveal roles for innate but not adaptive immunity. Immunity 30, 875–887, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.005 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson C. M., Howard A., Walters J. R., Ganapathy V. & Thwaites D. T. Taurine uptake across the human intestinal brush-border membrane is via two transporters: H+-coupled PAT1 (SLC36A1) and Na+- and Cl(−)-dependent TauT (SLC6A6). J Physiol 587, 731–744, doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164228 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munck L. K. & Munck B. G. Distinction between Chloride-Dependent Transport-Systems for Taurine and Beta-Alanine in Rabbit Ileum. Am J Physiol 262, G609–G615, doi:DOI 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.4.G609 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thwaites D. T., McEwan G. T. & Simmons N. L. The role of the proton electrochemical gradient in the transepithelial absorption of amino acids by human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Membr Biol 145, 245–256, doi: 10.1007/BF00232716 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith L. K. et al. beta2-microglobulin is a systemic pro-aging factor that impairs cognitive function and neurogenesis. Nat Med 21, 932–937, doi: 10.1038/nm.3898 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mota-Martorell N. et al. Methionine transsulfuration pathway is upregulated in long-lived humans. Free Radical Bio Med 162, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.11.026 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas T. et al. COVID-19 infection results in alterations of the kynurenine pathway and fatty acid metabolism that correlate with IL-6 levels and renal status. medRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.14.20102491 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabaka P. et al. Role of interleukin 6 as a predictive factor for a severe course of Covid-19: retrospective data analysis of patients from a long-term care facility during Covid-19 outbreak. BMC Infect Dis 21, 308, doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05945-8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phillips P. A. et al. Reduced thirst after water deprivation in healthy elderly men. N Engl J Med 311, 753–759, doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409203111202 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada Y. et al. Variation in human water turnover associated with environmental and lifestyle factors. Science 378, 909–915, doi: 10.1126/science.abm8668 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Estevez A. G. et al. Induction of nitric oxide-dependent apoptosis in motor neurons by zinc-deficient superoxide dismutase. Science 286, 2498–2500, doi:DOI 10.1126/science.286.5449.2498 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haskew-Layton R. E. et al. Two Distinct Modes of Hypoosmotic Medium-Induced Release of Excitatory Amino Acids and Taurine in the Rat Brain In Vivo. Plos One 3, doi:ARTN e3543. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003543 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehrotra P. et al. Oxylipins and metabolites from pyroptotic cells act as promoters of tissue repair. Nature 631, doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07585-9 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brestoff J. R. et al. Intercellular Mitochondria Transfer to Macrophages Regulates White Adipose Tissue Homeostasis and Is Impaired in Obesity. Cell Metab 33, 270–282 e278, doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.11.008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou J., Du X., Li J., Yamagata N. & Xu B. Taurine Boosts Cellular Uptake of Small D-Peptides for Enzyme-Instructed Intracellular Molecular Self-Assembly. J Am Chem Soc 137, 10040–10043, doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06181 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacobsen J. G. & Smith L. H. Biochemistry and physiology of taurine and taurine derivatives. Physiol Rev 48, 424–511, doi: 10.1152/physrev.1968.48.2.424 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Konstorum A. et al. Platelet response to influenza vaccination reflects effects of aging. Aging Cell 22, e13749, doi: 10.1111/acel.13749 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolf F. A., Angerer P. & Theis F. J. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol 19, 15, doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1382-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Emont M. P. et al. A single-cell atlas of human and mouse white adipose tissue. Nature 603, 926–933, doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04518-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang Z., Liu X. & Peltz G. GSEApy: a comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 39, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac757 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liberzon A. et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1, 417–425, doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.