Abstract

This study developed a biocompatible multifunctional thiol-ene resin system for adhesion to dentin mineralized tissue. Adhesive resins maintain the strength and longevity of dental composite restorations through chemophysical bonding to exposed dentin surfaces after cavity preparations. Dental pulp cells are exposed to residual monomers transported through dentinal tubules. Monomers of conventional adhesive systems may result in inhomogeneous polymer networks and the release of residual monomers that cause cytotoxicity. In this study, we develop a one-step multi-functional polymeric resin system by incorporating trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) and bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BMEP) to enhance both mechanical properties and adhesion to dentin. Molecular dynamics simulations identified an optimal triacylate:trithiol ratio of 2.5:1, which was consistent with rheological and mechanical tests that yielded a storage modulus of ~30 MPa with or without BMEP. Shear bond tests demonstrated that the addition of BMEP significantly improved dentin adhesion, achieving a shear bond strength of 10.8 MPa, comparable to the commercial primer Clearfil SE Bond. Nanoindentation modulus mapping characterized the hybrid layer and mechanical gradient of the adhesive resin system. Further, the triacrylate-BMEP resin showed biocompatibility with fibroblasts in vitro. These findings suggest the triacrylate-trithiol crosslinking and chemophysical bonding of BMEP provide enhanced bond strength and biocompatibility for dental applications.

Keywords: Triacrylate resin, dentin adhesion, nanoindentation, molecular dynamics simulation, thiol-ene polymerization

Introduction

Clinical applications involving bone and dental tissues require polymeric adhesives for etching and bonding to mineralized tissues. Conventional bone fixation methods, such as metal implants for bone fractures, show limitations in complex cases involving small, unstable fragments1. In restorative dentistry, failed restorations and tooth fractures remain a significant problem despite advancements in dentin resin adhesive materials2, 3. Further, residual monomers released from adhesive materials can negatively impact surrounding biological tissues.4, 5 There remains a need for biocompatible polymeric materials that can achieve strong adhesion to mineralized tissues.

Dental decay is increasing in prevalence, with over 3 billion untreated cases, despite increased access to prevention and dental treatments worldwide.6 Dental decay is treated by removing the decayed tooth material, preparing the tooth for direct access to dentin, and placing a direct resin restoration with a bonded adhesive resin interface.7 Adhesion to the dentin protects the restoration from microleakage, tooth fracture, infection, and ultimate failure of the treatment.8 The widely used commercial methacrylate-based adhesive, Clearfil SE Bond, only shows 56% double bond conversion for the methacrylate functional groups9. Lack of conversion may lead to inhomogeneous polymer networks, residual monomers in the resin, and cytotoxicity and disruption of cellular signaling 4, 10. Hydrolytic degradation and water sorption compromise the long-term durability of adhesive resins 10–12. Acrylamide-based polymers have been developed to improve bond stability and resistance to enzymatic and hydrolytic degradation.13, 14

Thiol-ene click chemistry has been investigated for bonding to mineralized tissues with rapid curing, minimal residual monomer content, and high cytocompatibility15. Thiol-ene-based polymeric materials can achieve mechanical strength comparable to methacrylate and polyurethane systems while minimizing cytotoxic effects.15 Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) and structurally-related tri-thiol (TMPTMP) monomers are investigated as three-armed thiol-ene crosslinked polymers for a biocompatible resin.16 Three acrylate groups in TMPTA provide a high degree of crosslinking, which improves thermal stability, mechanical strength, and glass transition temperature in UV-curable systems17, 18. TMPTA also enhances rheological properties like shear viscosity and storage modulus in various polymer applications, offering fast curing times and improved material hardness, making it more efficient than other monomers19, 20. Thiol-ene materials crosslinked with TMPTA supported the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), providing a bioinstructive environment for tissue regeneration.16

Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy) ethyl] phosphate (BMEP) is investigated in this study as an adhesive monomer. The phosphate group in BMEP reacts with mineralized tissues, such as bone and dentin, by interacting strongly with hydroxyapatite (HA), enabling effective demineralization, the formation of longer resin tags, and a stable hybrid layer 2, 21, 22. This interaction promotes deeper etching compared to other adhesive systems like 10-MDP, which primarily rely on superficial ionic bonding10, 12, 22 and enable an acid-free etching procedure. The methacrylate groups of BMEP can react with thiol-ene click crosslinking, promoting a high degree of polymerization to strengthen the adhesive network and enhance its mechanical properties15, 23. Furthermore, BMEP acts as an effective matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor, protecting the collagen matrix from enzymatic degradation and improving the long-term durability of the resin-dentine bond11, 23, 24. Additionally, compared to other etching systems, BMEP’s ability to perform both chemical and micromechanical retention makes it superior in creating a robust adhesive interface12, 25. This study aimed to develop a biocompatible adhesive with strong dentin adhesion based on the multifunctional properties of TMPTA and BMEP.

Experimental Methods

Materials

Chemicals used in this study, Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA), Trimethylolpropane tris(3-mercaptopropionate) (TMPMP), Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BMEP) and 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA) were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals in experiments were used as received without further purification.

Material Fabrication

The polymeric resin material was prepared using a dual monomer system consisting of TMPTA and TMPMP (Figure 1a), utilizing thiol-ene click chemistry (Figure S1), which facilitates rapid polymerization through a radical-mediated mechanism, and the photoinitiator, DMPA, was incorporated into the resin formulation to initiate the light-curable reaction. A range molar ratios of TMPTA and TMPMP was tested (1.5:1 to 5.5:1). 5% w/v BMEP was used for samples containing BMEP and 0.05% w/v DMPA was immediately added prior to shaker mixing for several minutes for homogenization. The solution was mixed at room temperature in a clean amber vial to prevent direct ambient light exposure.

Figure 1. Illustration of TMPTA-TMPMP resin-dentin dual adhesion mechanisms.

(a) Overall schematic of resin with Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) and Trimethylolpropane tris(3-mercaptopropionate) (TMPMP) as monomers, Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate (BMEP) as the primer, and 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA) as the photoinitiator. (b) Demonstration of both physical and chemophysical interlocks between resin and dentin through crosslinked polymers and chelation reactions involving BMEP.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted using Blend in Material Studio (http://accelrys.com/products/collaborative-science/biovia-materials-studio/). The process entails constructing desired chemical molecules, optimizing their minimum energy utilizing a preferred force field, and employing the Blend module for compatibility assessments. For example, it effectively evaluates the compatibility of the desired chemical molecule TMPTA with TMPMP. Throughout calculations, critical parameters such as temperature dependence of interaction (χ), binding energy, and phase diagrams are meticulously computed using theories like Gibbs free energy and Flory-Huggins. The outcome is a comprehensive table generated through energy minimization techniques, identifying the lowest energy pairs. Additionally, overlays assist in pinpointing the lowest energy absorption sites, revealing numerous compelling results. Once all molecules are individually minimized, blend computations are initiated by selecting base molecules (TMPTA) and screen molecules (TMPMP). The binding and potential energy data were analyzed of different combinations of TMPTA and TMPMP with simulations up to 10,000 steps during the production run. These calculations are executed at room temperature and atmospheric pressure, determining interaction energies for different mixtures. The chosen blending method provides crucial information on binding energy, coordination numbers, Flory-Huggins interaction parameter (χ), mixing, and interaction energy.

Oscillatory Shear Rheology

Rheology data were obtained using an HR30 Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (TA Inc.). 80 μL of the resin solution was dispensed onto the loading plate with the trim gap set to 1000 nm. Then, a time sweep of oscillatory shear rheology with strain % of 10−3 and a frequency of 1.0 Hz was carried out at 25°C for a duration of 930 seconds (30 seconds delay followed by 900 seconds of data collection). The power density of the ultraviolet (UV) source (Omnicure S2000, Excelitas) was 0.25 mW/cm2. The geometry gap was set to float to maintain a constant normal force. Polymerization shrinkage is measured by the change in gap during curing, defined by

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Dentin samples were prepared by removing enamel from human molars using IsoMet Low Speed Saw, and the cutting edge was sanded with 150 and 220 grit sandpapers. The resultant dentin samples had cuboid shapes, and resin solution was pipetted onto one of the cuboid surfaces which had the largest surface area. A cover glass treated with Smooth-On Ease release spray was positioned over resin solution to avoid oxygen inhibition. After being cured for 60 seconds under UV light with an intensity of 103.2 mW/cm2, the dentin sample coated with resin was detached from the cover glass. The interface between dentin and resin was further sanded with 150 and 220 grit sandpapers. Subsequently, SEM imaging of dentin samples was performed using Quanta 600 FEG ESEM.

Shear Bond Strength Test

Human third molars were obtained by from the Penn Dental Oral Surgery clinic, following approve IRB protocol #827807. Dentin surfaces were prepared using a 600-grit polishing wheel (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) and subsequently embedded in acrylic resin blocks. Resin solutions were applied to the denting surfaces in cylindrical plastic molds with the contact area being 2.1 mm2 and cured. All shear tests were carried out with a universal shear bond tester (BISCO Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA) applying a force (N) parallel to the interface between the dentin and adhesive. Shear bond strength was calculated in megapascals using the formula:

Nanoindentation Mapping

Nanoindentation was performed on a TI-950 nanoindenter (Hysitron, USA) with a diamond Berkovich pyramidal tip. Hardness and modulus were measured as described by Oliver and Pharr26, under load control, to a peak load of 8 mN, with a 5-second loading time, 2-second hold time at the peak load, and 5-second unload time. A 25-nm liftoff was used before testing to allow for proper surface detection27, and the reduced elastic modulus was calculated from the unloading curve26. Testing was performed on the dentin-resin interfaces, with the indentation direction parallel to the interfacial plane. A testing array was constructed to measure the elastic modulus of the dentin and resin as a function of the distance from the interface.

Biocompatibility Test

Resin samples with and without BMEP were soaked in low glucose DMEM (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 7 days. Collected condition media were diluted with low glucose DMEM to a final concentration of 100%, 50%, and 25% of the original condition media. BJ cells were seeded at 62500 cells cm−2 in 96 well-plate and incubated in low glucose DMEM (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cytiva). After 24 h, cell culture media were replaced by 100 μL serially diluted original condition media, and cells were kept culturing for 24 h. For fluorescence imaging, cells were fixed in 2% PFA for 30 min and then stained with Phalloidin and DAPI. For cell viability experiments, released LDH in cell culture supernatants was measured by CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega). Relative cell viability was compared with maximum LDH release control. For cell counting experiments, cells were trypsinized by Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) (Gibco) and retrieved from 96 well-plate. Retrieved cells were stained with 0.4% solution of trypan blue for counting.

Statistical Methods

GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis and data visualization. Rheology data was analyzed with unpaired t test. Shear bond test data was analyzed with Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA test. Sample size and p-values are noted in figures. Cell viability and cell counting data were analyzed with 2-way ANOVA test.

Results

The multi-functional resin material features physical and chemophysical adhesion mechanisms for bonding with mineralized tissues like dentin (Figure 1). The roughness and unevenness of the dentin surface provide micromechanical, physical bonding between the triacylate-trithiol network and micro-roughness on the interface. Monomer BMEP provides chemophysical bonding by chelation of calcium ions in hydroxyapatite of dentin by the phosphate group in BMEP. BMEP can also etch the surface, which increases roughness for physical bonding. Therefore, BMEP enables a one-step resin adhesive system.

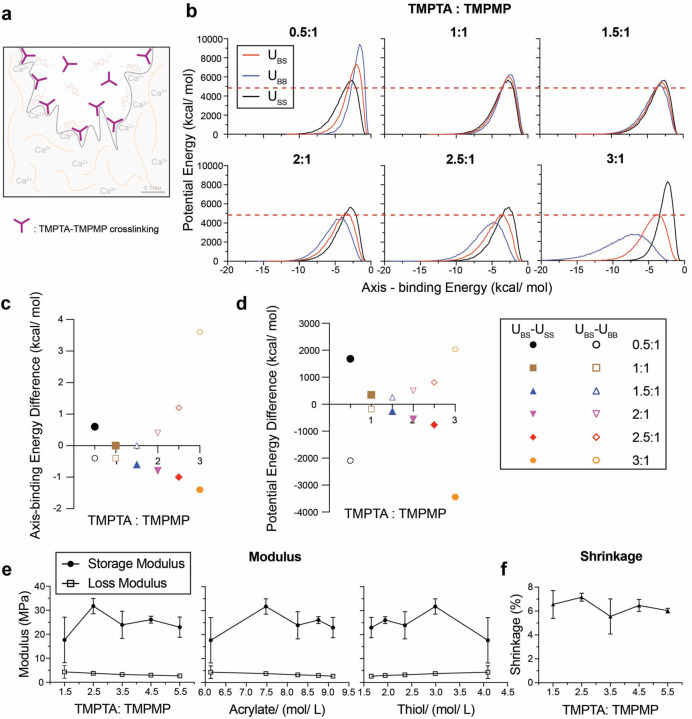

Cross-linked polymer networks reinforce the physical bonding of resin to dentin and increase the cohesive strength of the material (Figure 2a). The cross-linking of TMPTA polymers was investigated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and oscillatory rheology. MD calculations of TMPTA and TMPMP simulated the resin materials at the molecular level to predict polymerization dynamics and crosslinking efficiency28. The red solid curves show the energy between base materials and screening materials (UBS), the blue solid curves are the energy between base materials and base materials (UBB), and the black dotted curves represent the energy between screening materials and screening materials (USS) (Figure 2b). The results were evaluated to identify the appropriate reacting ratios by 1) minimizing UBS, 2) aligning interaction energies, and 3) finding the peak of UBS in between of USS and UBB. UBS’s potential energy is relatively low with molar ratios of 1.5:1 to 3:1. Lower potential energy of UBS in atomistic simulations should indicate the mechanical stability of the resin 28. The red dashed lines indicate the lowest UBS peak potential energy across six ratios. With increasing TMPTA and TMPMP molar ratios, the axis-binding energy difference between UBS and USS decreased while the difference between UBS and UBB increased (Figure 2c). Ratios ranging from 0.5:1 to 2.5:1 show both values near zero. USS, UBB and UBS should have similar curve shapes, and their axis should approximately align with each other (namely, their axis’s position should have the same axis-binding energy value on x-axis). Aligning the interaction energies of different monomers in thiol-ene systems optimizes polymerization dynamics by facilitating molecular collisions along favorable reaction pathways29. The potential energy difference between UBS and USS decreased and the difference between UBS and UBB increased (Figure 2d). The energy difference was largest with ratios at 0.5:1 and from 2.5:1 to 3:1. The peak of UBS should be in between USS and UBB and the one with larger energy differences is preferred because energy differentials between interacting components are critical for optimizing crosslinking reactions as larger energy differences drive more efficient polymerization15. Together, these results suggest that TMPTA: TMPMP ratio at 2.5:1 is most favorable for the thiol-ene reaction. The predicted molecular structure is shown in Figure S2.

Figure 2. Molecular dynamics simulations and comparative modulus and shrinkage analysis for resin systems with varying compositions of TMPTA and TMPMP.

(a) Illustration of TMPTA-TMPMP crosslinking in resin. (b) Molecular dynamics simulation results of potential energy and axis-binding energy profile for TMPTA and TMPMP reacting under different ratios. U – potential energy; S – screening material, TMPMP; B – base material, TMPTA. Summary plots for (c) axis-binding energy difference and (d) potential energy difference between UBS and USS or UBB for different TMPTA: TMPMP ratios. (e) Storage modulus and loss modulus of resin plotted as a function of: TMPTA: TMPMP ratios, acrylate concentration and thiol concentration. (f) Shrinkage of resin under different TPMTA: TMPMP ratios.

Oscillatory shear rheology was performed on resins with TMPTA: TMPMP ratios ranging from 1.5: 1 to 5.5: 1 with or without BMEP. Storage and loss moduli plotted with acrylate and thiol concentrations showed the highest storage modulus at 7.5 mol/L TMPTA concentration and ~2.9–3.0 mol/L TMPMP concentration, corresponding to a 2.5 molar ratio of TMPTA: TMPMP (Figure 2e). And shrinkage remained stable at around 6% through all ratios (Figure 2f). These data showed that increasing acrylate concentration above 7.5 mol/L (ratio=2.5) resulted in a trend of decreasing storage modulus, which is consistent with the MD simulations in Figure 2b-d.

The storage moduli of resin samples with BMEP (5 wt%) ranged from 23 to 36 MPa and remained slightly higher across all ratios than samples without BMEP (17~32 MPa). BMEP did not have a significant impact on the loss modulus (~3.5MPa) and polymerization shrinkage (~6%) (Figure S3). These values are comparable to other resin systems based on thiol-ene click chemistry15, 30, 31 and polymerization shrinkage studies (1~6%)32–34.

We investigated the mechanical and adhesive properties of the triacrylate/trithiol resin (TMPTA: TMPMP = 2.5) at the dentin-resin interface. Nanoindentation was performed on a thin film of TMPTA/TMPMP resin to evaluate the homogeneous curing and nanomechanical properties. The thiol-ene TMPTA and TMPMP radical-initiated propagation rate constant was estimated to be nearly 1000 times higher than that of methacrylate-methacrylate groups28, which leads to a rigid and homogeneous covalently crosslinked polymer network. This homogeneity is verified through the nanoindentation modulus in Figure S4. It shows the modulus was uniformly around 1GPa across the resin film’s frontside (0.992 GPa) and backside (1.125 GPa), with a higher modulus on the backside due to less oxygen inhibition35.

The adhesive interface between the human dentin and the resin material was characterized by SEM, EDS, shear bond strength, and shear rheology (Figure 3). The resin was cured onto dentin surfaces with exposed dentinal tubules. SEM imaging (Figure S5) showed resin tags in dentinal tubules, which was confirmed by the sulfur elemental analysis (yellow) (Figure 3b). When cured onto smooth, polished dentin surfaces, SEM imaging on the resin layer (196 μm thick) showed a smooth interface with dentin with no defects, suggesting an intact micromechanical bonded interface (Figure 3c). Shear bond tests were performed on smooth, polished dentin substrates (Figure 3d). The average shear strength of resin materials with and without BMEP was 10.8 MPa and 1.5 MPa, respectively (Figure 3e), compared to 13.3 MPa with the commercial primer Clearfil SE Bond. The adhesive strength of the multifunctional resin with BMEP showed no statistically significant difference with Clearfil SE Bond, which was consistent with the reported shear bond strength of other commercial adhesive resin systems36. Further, the modulus and shrinkage comparison of resin materials with or without BMEP did not show a statistically significant difference at a molar ratio of TMPTA: TMPMP = 2.5 (Figure 3f). These data suggest that the addition of BMEP significantly strengthens the adhesion on the resin-dentin interface without negatively impacting the resin system’s mechanical properties.

Figure 3. Comparative adhesion, storage modulus and shrinkage analysis of the resin-dentin interface and resin systems with and without BMEP.

(a) Illustration of resin-dentin interface. (b) SEM (left) and EDS (right) images of dentin interface with resin tag exposed. (Yellow: sulfur). (c) SEM images of dentin interface without resin tag under 200 μm and 50 μm scale. (d) Shear test demonstration for adhesion situation between resin and dentin sample and (e) corresponding shear strength statistical results for resins and the commercial primer Clearfil SE Bond (Brown-Forsythe and Welch Test, sample size n = 15). (f) Statistical results of two resin systems about storage modulus and shrinkage percentage (unpaired t-test, sample size n = 3).

We hypothesized that the phosphate-hydroxyapatite chemophysical interactions of BMEP reinforce the nano-mechanical interface of resin and dentin (Figure 4). Nanoindentation line mapping was performed to investigate the nanomechanical properties of the dentin-resin interface and its hybrid layer with a line of 20 indentation tests (black dots), spaced 10μm apart, beginning in the dentin 100μm away from the interface and running to 100 μm inside the resin (Figure 4b). Indents were spaced by a distance of 10 μm to avoid any interference from subsurface plastic deformation from neighboring indents27. Improved spatial resolution across the interface of 1 μm was achieved by running 10 separate lines of indents, each beginning 1μm closer to the interface, with each line being spaced 10 μm apart. This resulted in a total array of 200 indents on each specimen and an indentation test every 1 μm away from the interface from 100 μm inside the dentin to 100 μm inside the resin.

Figure 4. Nanomechanical analysis of the resin-dentin adhesive interface.

(a) Illustration of two interlocking mechanisms on the resin-dentin interface. (b) Nanoindentation mapping array (10 sperate indentation lines * 20 indentation tests), (c) modulus results for resin with (red) and without (black) BMEP, plots for (d) sigmoidal fitting results (blue curves), (e) corresponding summary table, and (f) comparison on HL’s sum of residual (SSres). (g) Weighted k-means clustering results (dentin region – orange, hybrid layer (HL) region – grey, resin region – blue), and (h) corresponding summary table. All the results demonstrated here represent the aggregate outcomes derived from the analysis of all 10 individual indentation line tests.

Line mapping nanoindentation results of TMPTA/TMPMP resin samples with BMEP (red dots) and without BMEP (black squares) are shown in Figure 4c. Sigmoidal fitting was utilized to model the transition between dentin and resin modulus (Figure 4d) because a similar sigmoidal shape was observed in nanoindentation studies of the dentin-enamel junction 37, 38. The sigmoidal expression to describe the relationship between modulus and indentation position is . E represents modulus, k is a fitting parameter, x is the position, and x0 is the shifted origin. The fitting parameter results in Figure 4e show a 22% higher modulus (3.84 GPa, R2 = 0.97) with BMEP compared to without BMEP (3.14 GPa, R2 = 0.94). Further, Figure 4f shows that BMEP improved the sigmoidal transition of modulus from dentin to resin, quantified by a lower sum of squared residuals (SSres) within the hybrid layer (32.6), compared to resin without BMEP (422.4). Weighted k-means clustering analysis39 was performed to calculate the thickness of the hybrid dentin-resin layer (Figure 4g – dentin (orange), hybrid layer (grey), resin (blue)). Resin materials with BMEP show a hybrid layer thickness of 22 μm, compared to 20 μm for samples without BMEP (Figure 4h). This hybrid layer thickness is larger than the numbers reported for other resin systems, which is from 0.3~10 μm40–43. These results suggest the addition of BMEP increases the thickness of the hybrid layer by 10%, which improves the mechanical stability of the dentin-resin interface. This is consistent with the shear strength results and other studies that suggest the importance of reinforcing the hybrid layer 40, 44. This nanoindentation result shows consistency in a more stabilized hybrid layer between materials to enhance bonding strength41.

Biocompatibility tests were performed using resin-treated conditioned media to confirm the triacrylate-trithiol polymer adhesive system supports cell viability10 (Figure 5 & S6). Fully cured resin samples with and without BMEP were conditioned in low glucose DMEM at 37°C. Media was collected after 7 days to treat in BJ fibroblast cells. Cell morphology was imaged after 24 h exposure to original condition media by fluorescence imaging of cells stained for cell nuclei (DAPI, blue) and F-actin (phalloidin, green) (Figure 5a & S6). The cytotoxicity of resin materials was measured by LDH release after 24 h exposure to serially diluted original condition media. In the 100% condition media group, the relative cell viability of resin with BMEP was 83.24%, and the resin without BMEP was 80.97%; in the 50% and 25% condition media group, the relative cell viability of resin with BMEP was 86.33% and 86.39%, respectively, compared to 88.54% and 87.71% for the resin without BMEP (Figure 5b). These revealed low cytotoxicity of this triacrylate-trithiol polymer system and no significant differences between the resins with and without BMEP. BJ cells were retrieved and cell numbers in each condition were counted after 24 h exposure to the serially diluted condition media. Media containing released residuals of resin materials with and without BMEP did not significantly affect cell number and proliferation (Figure 5c). Together, we confirmed that TMPTA resin systems had low cytotoxicity, and resins with and without BMEP didn’t exhibit significant differences in their biocompatibility. This finding can be applied to incorporate additional functional groups for drug delivery and remineralization at the mineralized tissue interface.

Figure 5. Biocompatibility of resin systems with and without BMEP.

(a) Fluorescence imaging (scale bar 200 μm) of BJ cells after 24 h culture in original condition (100% concentration) media compared to negative control, stained for nuclei (blue) and F-actin (green). (b) Relative cell viability, compared to negative control, and (c) cell counts of BJ cells after 24 h culture in condition media. Condition media are diluted with DMEM to a total concentration of 100%, 50% and 25% of the original condition media. n = 3 biological replicates, error bars represent SD.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the mechanical and adhesive properties of a multi-functional polymeric resin system composed of TMPTA and BMEP, designed to improve adhesion to mineralized tissues. Molecular dynamics simulations identified 2.5:1 TMPTA: TMPMP as the optimal ratio for the thiol-ene polymerization reaction, which was experimentally validated through rheological and mechanical testing. The addition of BMEP in the TMPTA resin played a crucial role in enhancing adhesion strength, achieving a shear bond strength of 10.8 MPa, comparable to commercial primer Clearfil SE Bond, without significantly affecting biocompatibility or shear modulus. Nanoindentation mapping further revealed that BMEP increased dentin-resin hybrid layer thickness with a sigmoidal modulus profile. Biocompatibility tests demonstrated that the TMPTA resin materials with and without BMEP had low cytotoxicity. The combination of micromechanical interlocking and chemophysical bonding with a thiol-ene polymer network enables strong adhesion while maintaining biocompatibility. Overall, the TMPTA-TMPMP-BMEP resin system presents a promising strategy for improving the longevity and clinical performance of dental adhesives, with potential applications beyond dentistry, including bone fixation and biomedical coatings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Joseph and Josephine Rabinowitz Award for Excellence in Research from Penn Dental Medicine. KHV received support from the National Institutes of Health for this work, NIH/NIDCR R00DE030084. This work was carried out in part at the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, which is supported by the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program under grant NNCI-2025608. We would like to acknowledge the undergrads from University of Pennsylvania, Hyunil Kim, Asset Yermekkaliyev, Sylvia Chen, Justin Wang and their advisor Shu Yang, who helped on the initial material synthesis protocol. We thank Luc Capaldi and Kailin Chen for their invaluable training and support on Nanoindentation test. And we also thank Brandley Tanelus for the preparation of dentin sample for shear bond test. Their assistance was instrumental in the successful completion of this research. LR acknowledges that this work was conducted during her sabbatical leave from CMU at the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors affirm that they do not have any known conflicting financial interests or personal relationships that could have potentially influenced the findings presented in this paper. KHV is a co-inventor of US patent 11224679B2 and European patent 3426182B1 related to the use of TMPTA and TMPMP for dental applications.

Data Availability

All data to generate figures for this manuscript will be made available prior to publication in a public repository.

References

- 1.Farrar D. F. Bone adhesives for trauma surgery: A review of challenges and developments. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2012, 33, 89–97. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2011.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuja N.; Nagpal R.; Pandit I. K. Dental adhesion: mechanism, techniques and durability. The Journal of clinical pediatric dentistry 2012, 36 3, 223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorndal L.; Fransson H.; Bruun G.; Markvart M.; Kjaeldgaard M.; Nasman P.; Hedenbjork-Lager A.; Dige I.; Thordrup M. Randomized Clinical Trials on Deep Carious Lesions: 5-Year Follow-up. J Dent Res 2017, 96 (7), 747–753. DOI: 10.1177/0022034517702620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krifka S.; Spagnuolo G.; Schmalz G.; Schweikl H. A review of adaptive mechanisms in cell responses towards oxidative stress caused by dental resin monomers. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (19), 4555–4563, Review. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisman R.; Aksoy A.; Yalcin M.; Karaoz E. Cytotoxic effects of bulk fill composite resins on human dental pulp stem cells. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 58 (3), 299–305, Article. DOI: 10.2334/josnusd.15-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassebaum N. J.; Smith A. G. C.; Bernabé E.; Fleming T. D.; Reynolds A. E.; Vos T.; Murray C. J. L.; Marcenes W. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. Journal of Dental Research 2017, 96 (4), 380–387. DOI: 10.1177/0022034517693566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes G. C.; Vieira L. C. C.; Araujo E. Direct composite resin restorations: a review of some clinical procedures to achieve predictable results in posterior teeth. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry 2004, 16 (1), 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breschi L.; Maravic T.; Mazzitelli C.; Josic U.; Mancuso E.; Cadenaro M.; Pfeifer C. S.; Mazzoni A. The evolution of adhesive dentistry: From etch-and-rinse to universal bonding systems. Dental Materials 2025, 41 (2), 141–158. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2024.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Z.; Jiang L. Visualization of single crosslinks and heterogeneity in polymer networks. Giant 2022, 12, 100131. DOI: 10.1016/j.giant.2022.100131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vining K. H.; Scherba J. C.; Bever A. M.; Alexander M. R.; Celiz A. D.; Mooney D. J. Synthetic light-curable polymeric materials provide a supportive niche for dental pulp stem cells. Advanced materials 2018, 30 (4), 1704486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgi R.; Kharouf N.; Cuevas-Suárez C. E.; Lukomska-Szymanska M.; Haikel Y.; Hardan L. A Literature Review of Adhesive Systems in Dentistry: Key Components and Their Clinical Applications. Applied Sciences 2024, 14 (18), 8111. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Munck J.; Van Landuyt K.; Peumans M.; Poitevin A.; Lambrechts P.; Braem M.; Van Meerbeek B. A Critical Review of the Durability of Adhesion to Tooth Tissue: Methods and Results. Journal of Dental Research 2005, 84 (2), 118–132. DOI: 10.1177/154405910508400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borges L.; Logan M.; Weber S.; Lewis S.; Fang C.; Correr-Sobrinho L.; Pfeifer C. Multi-acrylamides improve bond stability through collagen reinforcement under physiological conditions. Dental Materials 2024, 40 (6), 993–1001. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2024.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuzuki F. M.; Logan M. G.; Lewis S. H.; Correr-Sobrinho L.; Pfeifer C. S. Stability of the Dentin-Bonded Interface Using Self-Etching Adhesive Containing Diacrylamide after Bacterial Challenge. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2024, 16 (35), 46005–46015. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.4c07960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganabady K.; Contessi Negrini N.; Scherba J. C.; Nitschke B. M.; Alexander M. R.; Vining K. H.; Grunlan M. A.; Mooney D. J.; Celiz A. D. High-Throughput Screening of Thiol– ene Click Chemistries for Bone Adhesive Polymers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15 (44), 50908–50915. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.3c12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vining K. H.; Scherba J. C.; Bever A. M.; Alexander M. R.; Celiz A. D.; Mooney D. J. Synthetic Light-Curable Polymeric Materials Provide a Supportive Niche for Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Advanced Materials 2018, 30 (4), 1704486–n/a. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201704486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X.; Huang W.-T.; Yuan B.-Y.; He G.-J.; Yin X.-C.; Cao X.-W. Synergistic effect of GMA and TMPTA as co-agent to adjust the branching structure of PLLA during UV-induced reactive extrusion. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2023, 43 (7), 640–650. DOI: 10.1515/polyeng-2023-0106 (acccessed 2024-09-28). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalid M.; Salmiaton A.; Ratnam C.; Luqman C. Effect of trimethylolpropane triacrylate (tmpta) on the mechanical properties of palm fiber empty fruit bunch and cellulose fiber biocomposite. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 2008, 3 (2), 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Es-haghi H.; Bouhendi H.; Bagheri Marandi G.; Zohurian-Mehr M. J.; Kabiri K. An investigation into novel multifunctional cross-linkers effect on microgel prepared by precipitation polymerization. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2013, 73 (3), 524–530. DOI: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2012.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kardar P.; Ebrahimi M.; Bastani S.; Jalili M. Using mixture experimental design to study the effect of multifunctional acrylate monomers on UV cured epoxy acrylate resins. Progress in Organic Coatings 2009, 64 (1), 74–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.07.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vuorinen A.-M.; Dyer S. R.; Vallittu P. K.; Lassila L. V. Bonding of Composite Resin to Dentin Using Rigid Rod Polymer Modified Primers. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry 2010, 12 (3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkattan R.; Koller G.; Banerji S.; Deb S. Bis [2-(methacryloyloxy) ethyl] phosphate as a primer for enamel and dentine. Journal of Dental Research 2021, 100 (10), 1081–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkattan R.; Banerji S.; Deb S. A multi-functional dentine bonding system combining a phosphate monomer with eugenyl methacrylate. Dental Materials 2022, 38 (6), 1030–1043. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkattan R.; Koller G.; Banerji S.; Deb S. Bis[2-(Methacryloyloxy) Ethyl] Phosphate as a Primer for Enamel and Dentine. Journal of Dental Research 2021, 100 (10), 1081–1089. DOI: 10.1177/00220345211023477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarikaya R.; Ye Q.; Song L.; Tamerler C.; Spencer P.; Misra A. Probing the mineralized tissue-adhesive interface for tensile nature and bond strength. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2021, 120, 104563. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver W. C.; Pharr G. M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. Journal of materials research 2004, 19 (1), 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulco S.; Wolf S.; Jakes J. E.; Fakhraai Z.; Turner K. T. Effect of surface detection error due to elastic–plastic deformation on nanoindentation measurements of elastic modulus and hardness. Journal of Materials Research 2021, 36 (11), 2176–2188. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northrop B. H.; Coffey R. N. Thiol–ene click chemistry: computational and kinetic analysis of the influence of alkene functionality. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134 (33), 13804–13817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoyle C. E.; Bowman C. N. Thiol–Ene Click Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2010, 49 (9), 1540–1573. DOI: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q.; Zhou H.; Hoyle C. E. The effect of thiol and ene structures on thiol–ene networks: Photopolymerization, physical, mechanical and optical properties. Polymer 2009, 50 (10), 2237–2245. DOI: 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo C.; Fernández-Francos X.; De la Flor S. Rheological and Mechanical Characterization of Dual-Curing Thiol-Acrylate-Epoxy Thermosets for Advanced Applications. Polymers 2019, 11 (6), 997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaisarly D.; Gezawi M. E. Polymerization shrinkage assessment of dental resin composites: a literature review. Odontology 2016, 104 (3), 257–270. DOI: 10.1007/s10266-016-0264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Damanhoury H.; Platt J. Polymerization Shrinkage Stress Kinetics and Related Properties of Bulk-fill Resin Composites. Operative Dentistry 2014, 39 (4), 374–382. DOI: 10.2341/13-017-l (acccessed 10/3/2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao B.-T.; Lin H.; Han J.-m.; Zheng G. Polymerization characteristics, flexural modulus and microleakage evaluation of silorane-based and methacrylate-based composites. American journal of dentistry 2011, 24 (2), 97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauthier M.; Stangel I.; Ellis T.; Zhu X. Oxygen inhibition in dental resins. Journal of dental research 2005, 84 (8), 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amsler F.; Peutzfeldt A.; Lussi A.; Flury S. Bond Strength of Resin Composite to Dentin with Different Adhesive Systems: Influence of Relative Humidity and Application Time. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry 2015, 17 (3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall S. J.; Balooch M.; Habelitz S.; Balooch G.; Gallagher R.; Marshall G. W. The dentin–enamel junction—a natural, multilevel interface. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2003, 23 (15), 2897–2904. DOI: 10.1016/S0955-2219(03)00301-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue J.; Li W.; Swain M. V. In vitro demineralization of human enamel natural and abraded surfaces: A micromechanical and SEM investigation. Journal of Dentistry 2009, 37 (4), 264–272. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerdprasop K.; Kerdprasop N.; Sattayatham P. Weighted K-Means for Density-Biased Clustering. In Data Warehousing and Knowledge Discovery, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005//, 2005; Tjoa A. M., Trujillo J., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: pp 488–497. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skupien J. A.; Susin A. H.; Angst P. D.; Anesi R.; Machado P.; Bortolotto T.; Krejci I. Micromorphological effects and the thickness of the hybrid layer-a comparison of current adhesive systems. J Adhes Dent 2010, 12 (6), 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto M.; Ohno H.; Endo K.; Kaga M.; Sano H.; Oguchi H. The effect of hybrid layer thickness on bond strength: demineralized dentin zone of the hybrid layer. Dental Materials 2000, 16 (6), 406–411. DOI: 10.1016/S0109-5641(00)00035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albaladejo A.; Osorio R.; Toledano M.; Ferrari M. Hybrid layers of etch-and-rinse versus self-etching adhesive systems. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal 2010, 15 (1), e112–e118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ku S.; Tan Y.; Yahya N. A. The effect of different dental adhesive systems on hybrid layer qualities. Annals of Dentistry University of Malaya 2014, 21 (1), 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Arcangelo C.; Vanini L.; Prosperi G. D.; Bussolo G. D.; De Angelis F.; D’Amario M.; Caputi S. The influence of adhesive thickness on the microtensile bond strength of three adhesive systems. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry 2009, 11 (2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data to generate figures for this manuscript will be made available prior to publication in a public repository.