Abstract

There are currently no therapies for the staggering disability and public health costs of chronic low back pain (LBP). Innervation of the degenerating intervertebral disc (IVD) is suspected to cause discogenic LBP, but the mechanisms that orchestrate the IVD’s neo-innervation and subsequent symptoms of LBP remain unknown. We hypothesize that Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A (VEGFA) critically mediates the neurite invasion in the IVD and contributes to prolonged LBP. Initiating IVD degeneration through a mechanical injury, we evaluated the progression of neurovascular features into the IVD, as well as resultant LBP symptoms and locomotive performance at acute (3-weeks) and prolonged (12-weeks) time points following the IVD injury. To determine the role of VEGFA, we used a mouse model with ubiquitously inducible recombination of the floxed Vegfa allele (UBC-CreERT2; Vegfafl/f. The ablation of VEGFA attenuated the neurite and vessel infiltration into the degenerating IVD, and the VEGFA-null animals exhibited alleviated mechanical allodynia and improved locomotive performance. To determine the effects of IVD-derived VEGFA on endothelial cells and neurons, we cultured HMEC-1 endothelial cells and SH-SY5Y neurons using conditioned media from VEGFA-silenced (siRNA) human primary IVD cells stimulated by IL1β. The endothelial cells and neurons exposed to the secretome of the VEGFA-silenced IVD cells exhibited reduced growth, suggesting that the inhibition of IVD-derived VEGFA may be sufficient to attenuate intradiscal neurovascular features. Together, we show that VEGFA orchestrates the growth of intradiscal vessels and neurites that cause low back pain and impaired function, and the inhibition of VEGFA prevents prolonged sensitivity and motor impairment associated with discogenic low back pain.

Keywords: VEGFA, intervertebral disc injury, low back pain, neurovascular features, preclinical model

One Sentence Summary:

VEGFA critically mediates the infiltration of neurovascular features into the degenerating intervertebral disc and subsequent low back pain symptoms, and the ablation of VEGFA prevents chronic low back pain behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is a prevalent, debilitating, costly, and multifactorial condition worldwide, imposing substantial global and economic burdens 1-3. LBP affects as much as 80% of the population, and the elderly experience greater rates of LBP that exacerbate their functional decline, frailty, and loss of independence 4. LBP is the leading cause of years lived with disability and contributes an estimated $50 to $100 billion USD annually in healthcare costs 4-6. Chronic LBP is commonly associated with intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration, which occurs with aging, genetic predisposition, and injury 7-10. Degeneration leads to structural and biochemical changes in the IVD, including the loss of hydration, inflammation, and matrix breakdown 11-14. Despite our understanding of the features of IVD degeneration, it remains unclear which specific features of degeneration are mechanistically responsible for the eventual low back pain 15. While the healthy IVD is relatively aneural, the painful human intervertebral discs are innervated, suggesting a role for aberrant nerve growth in discogenic pain 16. VEGFA (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A) is a potent signaling protein that promotes the proliferation, migration, and survival of endothelial and neural cells17-19. While VEGFA has known roles in both vascular and neural support, its function following an IVD injury, and how it initiates or sustains discogenic pain remain unresolved. We hypothesized that VEGFA is crucial for the neurite growth and vascularization in the injured IVD to mediate acute and chronic discogenic pain.

To investigate the role of VEGFA in IVD degeneration and low back pain, we utilized a mouse model with an inducible global ablation of VEGFA. To model discogenic low back pain, we created an injury in the lumbar IVD to initiate degeneration 20-22. We subsequently measured pain-related symptoms such as mechanical and thermal sensitivity as well as locomotor function 20. Because VEGFA is also a critical regulator of vascular growth, we assessed neo-vascularization into the injured IVD along with neural infiltration to better understand the relationship between vascular and neural response in disc degeneration. To evaluate whether there was peripheral nervous system adaptation, we evaluated pain-related ion channels expression in the lumbar dorsal root ganglions (DRGs). To determine the role of IVD-produced VEGFA on neuron and endothelial cell growth we performed co-culture experiments using human cells.

Our findings show that VEGFA plays a central role in promoting neurovascular ingrowth into the degenerating intervertebral disc contributing to chronic low back pain. The ablation of VEGFA reduced neurite and blood vessel infiltration into the injured disc and alleviated mechanical allodynia and locomotor deficits in mice. VEGFA ablation also attenuated pain-related ion-channel expression in the DRGs of the injured animals. In vitro, endothelial cells and neurons exposed to conditioned media from VEGFA-silenced IVD cells exhibited diminished growth, reinforcing VEGFA’s role as a key mediator of vascular and neurite infiltration. These results demonstrate that targeted inhibition of VEGFA can suppress intradiscal vessels and neurites that cause low back pain and impaired function.

RESULTS

Removal of VEGFA Blunts Intradiscal Invasion of Neurovascular Structures

In WT animals, the injured IVD was infiltrated by PGP9.5+ neurons and by endomucin+ vessels. VEGFA ablation significantly blunted these neuronal and vascular features. Immunofluorescence images from 50μm thick sections (Figure 1A-B) showed fewer neural and vascular structures in VEGFA-null mice compared to WT particularly in the region around the outer annulus fibrosus (AF) near the injury site. Quantitative measurements of structural length and depth (Figure 1C-F) revealed diminished neurite length (p=0.01), vessel length (p=0.004), neurite depth (p=0.002), and vessel depth (p=0.047) due to VEGFA removal. Post hoc analysis reveals differences between the WT and VEGFA-null IVDs in neurite depth at 3 weeks (p=0.001) and in vessel length at 12 weeks (p=0.01). These findings show that VEGFA is crucial for instigating the neural and vascular structures in IVDs following injury. VEGFA ablation also limited the penetration into- and the propagation within- of these structures of the IVD. No sex-differences in nerve or vessel growth were observed (Table S1).

Fig. 1: Removal of VEGFA Blunts Intradiscal Invasion of Neurovascular Structures Following IVD Injury.

A) IHC of dorsal sides of the injured lumbar IVD with the nuclei (DAPI) in blue, neuronal features (PGP9.5) in green and vascular features (Endomucin) in red. The region-of-interest (ROI) is boxed with dotted lines. B) Outer AF ROI with key features notated C-F) VEGFA loss reduces neurite lengths (p=0.01) and vessel lengths (p=0.004) across both post-injury time points. Likewise, the neurite penetration depth (p=0.002) and vessel penetration depth (p=0.047) are blunted by VEGFA removal. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

VEGFA Is Essential for the Spatial Colocalization of Intradiscal Nerves and Vessels

The spatial proximity of intradiscal nerves and vessels are disrupted by VEGFA ablation. Immunofluorescence images reveal the distribution of neural (PGP9.5, green) and vascular (Endomucin, red) structures highlighting the regions of interest around the outer annulus fibrosus (AF) and overlapping lengths relative to neurites (Figure 2A-B). The colocalization analysis show that the WT injured IVDs have neurites with a large amount of vessels in their proximity. The removal of VEGFA in the IVDs 3 weeks following injury protected a higher number of IVDs from infiltrating neurites (Figure 2-C), but there was no difference in the number of IVDs with de novo neurites between the VEGFA-null and WT animals at 12 weeks after injury. The loss of VEGFA did not deter Endomucin+ vessels from penetrating the injured IVD at both time points (Figure 2D). The spatial overlap analysis between neurites and vessels (Figure 2E) show that VEGFA ablation dramatically reduces the amount of neurites near vessels (p=0.007). After adjusting for the length of the neurites, this observation remains robust independent of the basal level of neurites in each animal (p=0.008; Figure 2F). The lack of difference over time between the depth and the length ratios between the neurites and vessels indicates that once initiated, VEGFA does not appear to affect the propagation of these features (Figure 2G-H). These findings highlight the critical role of VEGFA in the initiation of neural and vascular features in the IVD.

Fig. 2: VEGFA is Essential for the Colocalization of Intradiscal Nerves and Vessels Initiation.

A) WT injured disc showing key features of the IVD and a ROI for analysis B) Graphical representation of how spatial colocalization analyses quantified the number of neurites that were in proximity of vessels within a 30 μm region. C-D) Loss of VEGFA significantly reduced the number of injured IVDs that experienced infiltrating neurites 3 weeks after injury (p=0.01) in VEGFA-null. Neurite (p=0.02) and vessel (p=0.03) infiltration both show a significant decrease in VEGFA-null groups. E) VEGFA ablation reduced the amount of vessel-adjacent neurites (p=0.007). F) The effect of VEGFA loss on preventing neurite-vessel spatial coupling persevered even when accounting for varying intradiscal neurite lengths between different animals (p=0.008), confirming that this local phenomenon is conserved across animals. G-H) The lack of difference in the depth penetration and length elongation ratios suggest that, on average, once the neurites have initiated, the loss of VEGFA does not appear to affect their propagation. Statistical model C-D: Fisher’s exact test. Statistical model E-H: 2 factor ANOVA with Fisher LSD post-hoc comparisons. E-H Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Depletion of VEGFA Suppresses the Expression of Pain-related Ion Channels in the DRG

Quantitative measurements of corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) of mouse lumbar (left, L3-L6) dorsal root ganglia (DRGs; Figure 3B-D) revealed a significant reduction in transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) fluorescence (p=0.04) due to VEGFA removal following injury. No significant changes were measured in tyrosine kinase receptor A (TrKA) or transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) CTCF levels due to the loss of VEGFA ablation.

Fig. 3: VEGFA Inhibition Reduces the Expression of Pain-related Ion Channels in the DRG.

A) TrKA (top), TRPV1 (middle), and TRPA1 (bottom) in green and DAPI in blue were quantified. B-D) Corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for each sensory ion channel shows VEGFA ablation regulated TRPA1 expression (p=0.037).

Ablation of VEGFA Alleviates Mechanical Sensitivity and Locomotive Function

Loss of VEGFA Attenuates Mechanical, but Not Hot or Cold, Sensitivity

WT animals exhibited mechanical sensitivity measured by the Von Frey filament test at both 3 and 12 weeks after the IVD injury. Ablation of VEGFA partially restored this impairment at the 12-week time point (p=0.001, Figure 4A), although no effects of VEGFA ablation was observed at 3-weeks following IVD injury. The electronic Von Frey filament test also revealed that there is a greater mechanical sensitivity on the left side of the surgical approach. VEGFA removal specifically alleviated the mechanical sensitivity of the injured side, without modifying the contralateral side (Figure S1F). No notable changes were observed in heat or cold sensitivity at any post-operative time point (Figure 4B-C; Table S1).

Fig. 4: VEGFA Ablation Improves Mechanical Sensitivity and Performance.

A) Mechanical sensitivity shows a significant interaction between genotype and time (p=0.001) in mice following IVD injury with a worsening effect seen in WT leading to a chronic sensitivity and an improving effect in VEGFA-null over time. B-C) No evidence of differences in hot or cold sensitivity was observed at any time. D) There was evidence of significant differences in longitudinal measures of performance that included rotarod (genotype, p=0.004; time, p=0.003), indicative of a VEGFA rescue of an injury associated progression of decreased performance in the rotarod test. E-F) There was no evidence of differences in any measures of open field with genotype and at any time point. G-I) There was no evidence of differences in inverted screen endurance or hind paw grip strength with genotype and at any time point. Statistical model A-F, I: Linear mixed effects with genotype and time as factors with post-hoc LSM with Sidak correction. G-H Mantel-Cox test. A-F, I Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

VEGFA Ablation Improves Rotarod Performance, but Does Not Affect Passive Function

We also evaluated locomotive performance through an active challenge of locomotive function, measured through the rotarod assay, longitudinally, every three weeks up to 12 weeks after injury. The longitudinal rotarod test (Figure 4D) reveals that VEGFA-null mice exhibited longer latencies to fall at 9- and 12-weeks post-injury compared to impaired WT (p=0.004), highlighting progressive motor coordination decline over time in the WT animals (p=0.003). In the Open Field test, total distance traveled (Figure 4E) and rearing counts (Figure 4F) were not different between genotypes, sex, tamoxifen, or due to surgery (Table S1), suggesting comparable levels of exploratory behavior and general activity between all groups.

VEGFA Removal Does Not Affect Measures of Strength

To determine overall impacts on much function following VEGFA ablation, strength assessments were conducted, including inverted screen endurance and hind paw grip strength analysis. The inverted screen endurance test, presented using Kaplan-Meier curves, showed that VEGFA-null mice have similar probabilities of hanging on the wired mesh compared to WT at both 3 weeks (Figure 4G) and 12 weeks (Figure 4H). Measures of hind paw grip strength (Figure 4I) were also found to be similar across genotypes, indicating no compromise in muscle function from VEGFA ablation.

Overall, the behavioral and locomotive function analyses show that VEGFA-null mice have improved recovery of mechanical sensitivity and avert the transition to chronic sensitivity seen in the WT while also avoiding the performance deficits in WT at chronic time points. However

Ablation of VEGFA does not affect structure, function, or degeneration of the IVD

Loss of VEGFA Does Not Affect the Histopathologic Degeneration of the IVD

CEμCT analysis of the IVDs 3 weeks after injury reveals significant deterioration of the IVD structure. By using a contrast enhancing agent, Ioversol, the injury was observed on the ventral side of the outer AF as progressively higher attenuating regions that mark the fibrous scar tissues (Figure 5A). The injured IVDs also exhibit a loss of NP attenuation, measured by NI/DI, demonstrating the loss of the water retaining ability of the NP (p=0.03, Figure 5B). The ablation of VEGFA does not affect these injury-mediated changes in degeneration. A narrowing of the intradiscal space measured by disc height index (DHI), a hallmark of IVD degeneration, is apparent in all of the injured discs (p=0.01, Figure 5C) with no evidence of differences among genotypes or with post-operative time. Surprisingly, there was not a change in NP volume either due to injury or VEGFA ablation (Figure 5D). Injury increases the degenerate features including decreased NP hydration and a narrowing DHI; VEGFA ablation did not appear to alleviate these tissue-level changes in the IVD.

Fig. 5: Loss of VEGFA Does Not Alter Structural, Mechanical, or Histopathologic Degeneration to the Injured IVD.

A) IVD structure analyses via CEμCT show that B) injury decreased NP hydration (p=0.03), indicated by the decreased attenuation of the NP compared to sham. C) injury decreased disc height index, DHI, (*, p=0.01) compared to sham, and D) no effect of injury was observed on NP volume. Changes to mechanical behavior were not observed in E) stiffness and F) dissipation factor, indicating that tissue level mechanics were not changed by injury or VEGFA removal at 3-weeks post injury. G) Histological images stained with Safranin-O and Fast Green show IVD degeneration. H) Histopathologic scoring shows a strong effect of injury (*, p<0.0001) with no appreciable differences due to VEGFA loss in nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosus, end plate, or the interface/boundary demonstrating the pathophysiological response from needle puncture. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Injury to the IVD Does Not Impair Its Mechanical Function

Dynamic compression of IVDs 3 weeks post injury show no distinct mechanical responses to injury or impact from VEGFA ablation. The stiffness measurements show no significant differences between WT and VEGFA-null groups, both in sham and injured conditions (Figure 5E). Likewise, the dissipation factor indicates a similar response with no appreciable changes from injury or VEGFA loss (Figure 5F). These findings show that the degeneration that occurs at 3 weeks after injury in this model does not yet impair the IVD’s mechanical function.

VEGFA Loss Does Not Rescue the Degenerative Changes Caused by Injury

Histopathological scoring (Figure 5G-H) revealed the damaging effects of a needle stab on the compartments in the disc, including decreased NP cell density and changes in cellular morphology, disruption of the AF concentric lamellar structures with increased cellularity and presence of clefts, along with thinning and disruptions in the endplate cartilage, and structural disorganization in the boundary regions. Scores for injured groups averaged near 26 out of a 36 possible for maximal injury, while sham controls averaged 11 (p < 0.0001). Statistical differences due to VEGFA removal were not detected. IVD injury dramatically changed all compartments of the disc with the largest effects on the AF followed by NP while sham scores indicate mild degeneration from the surgical exposure of the disc and likely disruption of surrounding soft tissues.

Silencing VEGFA RNA in Human IVD Cells Attenuates the Growth of Co-Cultured Neuronal and Endothelial Cells

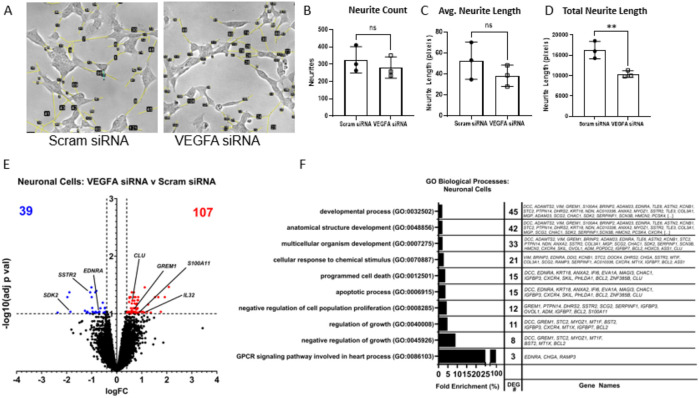

Transfecting human IVD cells with VEGFA-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) suppressed their production of the VEGFA protein production by 57.4% when stimulated with IL-1β (Figure S6). Coculturing these VEGFA-siRNA transfected, IL-1β stimulated IVD cells with SH-SY5Y neurons maintained the neuron morphology but blunted the growth of the axonal extensions (Figure 6A). Although there was no difference in the number of neurites and their averaged lengths for co-cultured neurons (Figure 6B-C), the total neurite length, which is a product of these two measurements, reveals a decrease in neurite growth co-cultured with VEGFA-siRNA transfected IVD cells (Figure 6D). RNA sequencing revealed that neurons cultured with VEGFA-knockdown IVD cells expressed 39 downregulated and 107 upregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) when compared to those neurons cultured with VEGFA-intact IVD cells (Figure 6E). Gene ontology analysis determined the most enriched biological process from the DEGs involved the regulation of general cell processes, e.g. GPCR signaling pathway, known for neurovascular development (EDNRA, CHGA, RAMP3), regulation of growth (DCC, GREM1, STC2, MYOZ1, MT1F, BST2, IGFBP3, CXCR4, MT1X, IGFBP7, BCL2), and the negative regulation of cell population proliferation (GREM1, PTPN14, DHRS2, SSTR2, SCG2, SERPINF1, IGFBP3, OVOL1, ADM, IGFBP7, BCL2, S100A11). Notably, several DEGs were specific to cell growth inhibition (SSTR2, S100A11), immune cells and inflammation (CXCR4, FGFB2, IL32), and neuronal cell functions (DCC, SDK2, ASTN2).

Fig. 6: VEGFA Inhibition Reduces in vitro Neurite Activity and Suppresses Processes Related to Growth and Elongation.

A) Neurite extension assay after treating neuronal cells with media collected from IL-1β stimulated and siRNA transfected human disc cells shows inhibition of neurites in neuronal cells (NC) with VEGFA siRNA treatment. B-D) Quantification of neurite lengths showing functional suppression with VEGFA siRNA in NCs. E) Volcano plot of RNA-seq analysis showing 146 differentially expressed genes and F) key biological processes regulated by VEGFA siRNA. NCs co-cultured with IL1β naïve disc cells showed undifferentiated cells possessing few short projections which cluster together, while NCs co-cultured with IL1β+SCRAM siRNA and NCs co-cultured with IL1β+VEGFA siRNA showed differentiated cells having many extensive projections.

We also co-cultured VEGFA-siRNA transfected IVD cells, first stimulated with IL-1β, with the HMEC-1 endothelial cells (aka ECs). The ECs cocultured with VEGFA-silenced human IVD cells were less capable of forming closed tubes, a measure of angiogenesis (Figure 7A). ECs cultured with Scram siRNA developed a higher number of closed loops than ECs cultured with VEGFA-siRNA (p=0.04) after 6 hours of culturing. (Figure 7B). RNAseq uncovered 175 downregulated and 0 upregulated DEGs when ECs are cultured with IVD cells transfected with Scram versus VEGFA siRNA (Figure 7C). Gene ontology analysis determined the most enriched biological processes from the DEGs were involved in vessel and vasculature related processes, These included lymph vessel development (NR2F2, TBX1, SOX18, EFNB2, HEG1), blood vessel morphogenesis (TNFAIP2, EFNB2, HEG1, PRKACA, NRARP, TBX1, SOX4, NR2F2, AKT1, QKI, SMAD7, SOX18, VEGFB), and regulation of neuron projection development (EFNB2, CDK5R1, RYK, RAPGEF1, CARM1, AKT1, PLZNA1, NCS1, DVL1, SLK, STK24, BRSK2, ADNP). Interestingly, the canonical WNT signaling pathway was also an enriched biological pathway. WNT signaling plays an important role in endothelial cell proliferation, survival, differentiation and response to mechanical forces due to shear stress from blood flow.23,24

Fig. 7: VEGFA Inhibition Reduced In Vitro Endothelial Cell Function and Regulates Gene Transcription.

A) Matrigel tube forming assay images of endothelial cells (ECs) cocultured with human IVD cells treated with siRNA showing initiation of vessel formation after 6 hours. B) The silencing of VEGFA siRNA in IVD cells reduced tube formation in EC co-cultures, compared to IVD cells with Scrambled siRNA (p=0.04). C) The silencing of VEGFA in IVD cells via siRNA was associated with 176 downregulated genes in EC co-cultures. There is a suppression of key angiogenic genes in ECs including HEG1, NARAP, and NCS1. There is also a suppression of endothelial cell-derived neurogenic genes including BRSK2 and CRLF1. D) The RNAseq analyses of the HMEC-1 also show an ontological shift to lymphangiogenesis, matrix remodeling, and suppression of neurovascular regulating pathways following co-culture with VEGFA-silenced IVD cells.

The endothelial cells co-cultured with the VEGFA-silenced IL-1β-stimulated IVD cells produce less angiogenic and inflammatory factors and more non-VEGFA proangiogenic compensatory factors

Following co-culture with VEGFA-silenced, IL-1β-stimulated IVD cells, the HMEC-1 endothelial cells exhibited a distinct cytokine profile that suggests a shift in cellular function. Notably, there was a reduction in secretion of VEGFA (Figure 8A) and CCL3 (Figure 8K) protein in the ECs co-cultured with VEGFA-silenced IVD cells, indicating decreased angiogenic and inflammatory signaling from factors secreted by the VEGFA-deficient IVD cells. In contrast, HMEC-1 cells exposed to VEGFA-silenced disc cells upregulated VEGFC protein, a canonical driver of lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic endothelial cell proliferation 25,26. Simultaneously, ECs increased protein production of PDGF-AA (Figure 8J), a mitogenic factor that can compensate for VEGFA loss by promoting vessel stabilization and pericyte recruitment 27. Increases in MMP1, MMP3, MMP10, and MMP13 protein levels (Figure 8C-F) reflect heightened extracellular matrix remodeling, a process essential for vessel pruning and structural reorganization typically associated with either vessel regression or tissue remodeling rather than active angiogenesis28,29. The elevation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) supports a role for immune cell recruitment and activation, especially of myeloid lineages that modulate inflammation and tissue repair (Figure 8G-H) 30,31. Similarly, upregulation of CXCL1 and CCL5 (RANTES) reinforces the potential for leukocyte chemotaxis and immune surveillance (Figure 8I,L) 32,33.

Fig. 8: The secreted factors from HMEC-1 (aka ECs) co-cultured with IVD cells were analyzed using the Luminex multiplex ELISA.

Despite having a functional VEGFA gene, the ECs produced less (A) VEGFA and (K) CCL3 protein when co-cultured with VEGFA-silenced IL-1β–stimulated IVD cells. The ECs also produced more (B) VEGFC and (J) PDGF-AA that are both positive regulators of lymphoangiogenesis; MMPs (C-F; MMP1, MMP3, MMP10, MMP13) involved in matrix remodeling; chemokines including (G) G-CSF, (H) GM-CSF, (I) CXCL1, and (L) CCL5; and (J) PDGF-AA, a compensatory angiogenic growth factor. Units are pg/ml.

Taken together, this cross talk supports a mechanism in which endothelial cells, in the presence of IL-1β-stimulated secretome of VEGFA-silenced IVD cells, pivot toward a reparative state characterized by elevated lymphangiogenesis, increased immune cell engagement, and enhanced matrix remodeling—rather than the robust angiogenic response seen with IL-1β-stimulated VEGFA-intact IVD cells. These findings align with the vessel-pruning and tissue remodeling hypotheses seen in regenerative contexts and suggest that VEGFA inhibition not only reduces angiogenesis but promotes a more immunomodulatory and matrix-adaptive endothelial phenotype. In addition, several mediators known to support vessel homeostasis (e.g., Angiopoietin-2, Endoglin, Endothelin-1, PlGF) remained unchanged in co-culture with the VEGFA-silenced IVD cells (Table S2) and likely continue to support the normal functions of existing vessels.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to demonstrate that intradiscal innervation contributes to low back pain behavior and locomotive performance in a model of intervertebral disc degeneration. While studies in the past have shown progressive associations where neurovascular structures increase with progressive degeneration and pain,34-38 none have been able to block or prevent these structures to prevent chronic pain and maintain locomotive performance. From this work, we also demonstrate that VEGFA may be a therapeutic target for a disease modifying therapy of low back pain. While VEGFA ablation did not significantly impact the structural and mechanical properties of the IVDs, it had a profound effect on neural and vascular infiltration and the subsequent mechanical sensitivity and locomotive performance following degeneration.

VEGFA plays a crucial role in limiting nerve and vessel infiltration post-injury. IVD degeneration in VEGFA-null mice exhibited reduced neurite and vessel lengths and the depths of their penetration, particularly in the outer annulus fibrosus (AF). VEGFA ablation inhibits the elongation and penetration of neural and vascular structures in the normally avascular IVD, potentially preventing painful sensory neurons from entering injured areas. The synergistic relationship between nerve and vessel infiltration highlights VEGFA's importance in neurovascular coupling within the IVD, with its absence leading to diminished neurite and vessel growth, which may limit painful neurological signals and affect overall disc health. These findings emphasize VEGFA's critical role in supporting neural and vascular initiation post-injury.

The loss of VEGFA also affected some of the neuropeptide-related signaling in in the Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG). The increase expression of TrKA, TRPV1, and TRPA1 in the DRG have been observed in chronic low back pain 39,40, as well as in DRG that are sensitive to capsaicin stimulation 41. The decrease in TrKA activation could be responsible for the reduction in pain sensitivity measured by the Von Frey test. The VEGFA-null mice were less sensitive to mechanical filament provocation than the wild-type mice at prolonged time points. VEGFA removal also decreased TRPA1 expression, whose inhibition is associated with cold sensitivity, in the DRGs. However, these animals did not exhibit cold sensitivity. In contrast, TRPV1 expression, commonly associated with heat sensitivity 42, did not change between VEGFA-null mice and wild-type mice. Indeed, the VEGFA-null mice and wild-type mice did not exhibit observable difference in heat sensitivity in the hot plate experiment. The behavioral assessments revealed that despite exhibiting acute pain post-injury, VEGFA-null mice had improved recovery from mechanical sensitivity and avoided the prolonged sensitivity observed in WT mice. VEGFA-null mice did not develop the motor performance impairments seen in WT mice at later points (9-12 weeks), indicating a protective effect of VEGFA ablation against prolonged pain and impaired performance. Mechanical sensitivity showed imbalanced injury induced sensitivity while VEGFA inhibition balanced this asymmetry demonstrating that VEGFA loss rescued the IVD injury effects but did not change systemic pain sensing. Taken together, our results suggest that modulation of VEGFA in this context modifies the disease physiology rather than exerting analgesic effects.

Neurovascular Elongation vs Sprouting

Injuries to the intervertebral disc primarily trigger nerve and blood vessel sprouting as an adaptive response to inflammation and hypoxia 43,44. This sprouting—stimulated by factors like NGF and inflammatory cytokines—leads to increased neurovascular infiltration into normally aneural and avascular disc regions, contributing to chronic pain and ongoing inflammation.45-47 Consistent with this, we observed neurites and vessels infiltrating into the degenerating IVD at 3-weeks following injury. However, once sprouted, the neurites did not appear to elongate further, as evidenced by the relative similar lengths and depths between 3- and 12- weeks. In this animal model, VEGFA is ubiquitously ablated from the whole animal, and it is not possible to determine the source of the VEGFA. However, our in vitro experiments support that blocking IVD-produced VEGFA is sufficient to prevent growth of the neurites and the maturation of the blood vessels. RNAseq analysis suggested that the reduced neural outgrowths is driven by the suppression of cell proliferation. We observed a phenotypic shift in the endothelial cells co-cultured with VEGFA-silenced IL-1β–stimulated IVD cells, which secreted higher levels of VEGFC and PDGF-AA, positive regulators of lymphangiogenesis, alongside increased MMPs, and immune cell recruiting chemokines. Such changes suggest that, in the absence of VEGFA-driven angiogenesis, endothelial cells promote a microenvironment conducive to tissue remodeling and immune-mediated repair. These immune cell recruiting chemokines are likely to be important for the intrinsic healing of the IVD 48. RNAseq analyses of the HMEC-1 also showed an ontological shift to lymphangiogenesis and matrix remodeling with a suppression of key angiogenic genes including Heg1, Narap, and Ncs1. There is also a suppression of endothelial cell-derived neurogenic factors including Brsk2 and Crlf1.

Needle stab injury models in animals are frequently utilized to study the pathophysiology of intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and to develop treatments for chronic lower back pain (CLBP). These models effectively replicate critical aspects of human disc degeneration, such as mechanical damage, inflammatory responses, and biochemical changes. For example, they simulate the mechanical damage caused by traumatic events and the inflammatory cytokine upregulation observed in human discs, which are crucial for understanding the progression of disc degeneration49. However, these models have limitations, especially in replicating the chronic, multifactorial nature of human CLBP and the complexity of human pain perception50,51. Human IVD degeneration occurs over years and decades, with the herniation of the IVD being one of the most apparent instigating factors. Despite the varied etiologies of discogenic pain, the chronic symptoms and eventual degenerative presentation, such as the deterioration of IVD structure, are quite similar. Therefore, the needle injury model in murine IVD is employed to understand the mechanisms following IVD injury that eventually lead to low back pain symptoms.

While these models are beneficial for basic research and initial therapeutic testing, their findings must be interpreted with caution and validated in more complex models and ultimately in human clinical studies. Differences in disc anatomy and biomechanics between humans and animals can affect the translational relevance of these models, underscoring the need for complementary approaches to fully capture the complexity of human IVD degeneration51. The needle injury in a mouse induces progressive, but relatively rapid degeneration, occurring over weeks and months, compared to human degeneration, which spans years and decades. Despite being traumatic relative to the human scale, this model is a necessary caveat for developing feasible and mechanistic experiments. A single level lumbar injury utilized here may also have underestimated the magnitude of our findings, since multiple groups have shown a more pronounced pain behavior with 3 levels of injury in rodents 52.

The multifactorial nature of the injury and VEGFA ablation at 3 weeks complicated the detection of significant changes acutely, but painful alterations were apparent with successive longitudinal measurements. Additionally, the WT sham group displayed elevated disc degeneration scores, suggesting that sham procedures may induce a mild phenotype. Notably, neurovascular ingrowth was more pronounced on the dorsal side opposite the ventral injury location, as seen by others34, likely due to its proximity to the spinal cord and increased availability of neural and vascular sources. These findings have translational promise since it is possible to intervene early in the sequalae of chronic low back pain development. Since patients typically seek treatment only after an injury or an acute episode of pain, the timely post-injury inhibition of VEGFA may be able to prevent the transition to chronic low back pain.

Overall, the loss of VEGFA appears to be protective against mechanical sensitivity, with decreased innervation and no major impact on IVD degeneration. These findings, for the first time to date, show a causative relationship between neurovascular pathoanatomy and pain while implicating VEGFA as a critical mediator in these processes following lumbar injury and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target for preventing lower back pain through neurovascular inhibition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design

The Postnatal Inducible Ablation of Vegfa in Adult Mice

Young adult, 4–6-month-old, ubiquitin (UBC)-CreERT2 ; Vegfafl/fl; Ai9-tdTomato mice on a C57BL/6J background 53-55 allowed for a temporally controllable ablation of Vegfa upon tamoxifen administration with recombination expressed via an Ai9 fluorescence reporter. An estrogen responsive Cre element is activated when a mutant estrogen receptor (ERT2) renders Cre active upon tamoxifen binding and promotes Cre entering the nucleus and catalyzing a recombination event at LoxP sites. These Cre+ mice allow for precise temporal control over gene modification allowing ubiquitous recombination through systemic ablation of Vegfa in all tissues. Moreover, this approach can avoid developmental defects and embryonic lethality, especially in pathways that are essential to organogenesis. All procedures (breeding, drug administration, procedures, and tissue extraction) were performed with WUSM IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) approval.

Confirmation and Quantification of Vegfa Ablation

The Ai9-tdTomato reporter protein is co-expressed with Cre recombinase presence, and it is visually evident (Figure S1) by inspection at the macroscopic scale after two doses of tamoxifen (100 mg/ kg) administered over two consecutive days.

We also evaluated the efficiency of Vegfa ablation in the intervertebral disc (IVD) by measuring the production of the VEGFA protein secreted by the IVD. Mice with Cre− and Cre+ alleles driven by the ubiquitin promotor in animals with the homozygous Vegfa floxed alleles (UBC-CreERT2; Vegfafl/fl Ai9) received 2 consecutive days of tamoxifen administration via oral gavage (100 mg/kg in corn oil). The animals were sacrificed on the third day, following the two days of induction. The functional spine units (FSUs), containing the vertebrae-intervertebral disc-vertebrae structure were cultured as previously described and stimulated with TNFα (5ng/ml) to provoke an inflammatory response 56. Media was collected every other day for 7 days and analyzed using a VEGFA ELISA (R&D Systems Cat: DY493).

The Lumbar Puncture Intervertebral Disc Injury Model

Male and female mice of 4-6 months of age were randomly allocated into respective experimental groups. The animals undergoing surgery were first anesthetized using a subcutaneous lidocaine injection (0.5% at 7mg/kg) followed by isoflurane inhalation (3–4% v/v induction and 2–2.5% v/v maintenance at 1 L/min flow rate). The left flank was shaved, and the skin sterilized with 70% ethanol and povidone iodine. Under microscopic guidance, a retroperitoneal dissection was performed to expose the lateral aspect of the spine using a Penfield dissector and size 11 scalpels. The pelvis and hip were rotated posteriorly to enhance the working space. The peritoneal wall was gently tugged to expose the psoas muscle, which was retracted posteriorly to anteriorly using a cotton swab and then held in place with a metal spatula. The spinal column and IVDs at the L5/6 and L6/S1 levels were exposed by blunt dissection. The superior margin of the pelvic bone indicated the L6 vertebral body, confirming the locations of L5/6 and L6/S1 IVDs. The L5/L6 IVD was targeted and either exposed in shams or injured with a 30G needle 3 times through the annulus fibrosus and partially into the nucleus pulposus 20,34.

Postoperatively, mice were monitored every 8–12 hours for 4 days. Pain management included intraperitoneal injections of carprofen (5 mg/kg) every 8–12 hours, supplemented with carprofen tablets (2 mg/tablet) for 48-72 hours. On days 3 and 4 post-operatively, tamoxifen (TAM, Cat#: T5648, Millipore Sigma) was given via oral gavage (100 mg/kg in corn oil, Cat#: C8267, Millipore Sigma) to Cre+;Vegfafl/fl animals (aka ‘VEGFA-null’) and Cre−;Vegfafl/fl littermates (‘WT’) inducing Vegfa ablation. Data collection occurred at 3 and 12 weeks with behavioral assays including additional timepoints at baseline, within 7 days of injury, and longitudinal cohorts at 6 and 9 weeks. Mouse weights were collected at baseline, 3, and 12 weeks to track overall health and survival was tracked throughout the experiment to create Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Acute 3-week post-op and chronic 12-week post-op time points were chosen with the acute injury response allowing for the initial surgical wound healing recovery, while chronic LBP is defined as pain lasting 12 weeks or longer 57,58.

Histological analyses

Histopathological Evaluation of Degeneration

To quantify acute IVD degeneration at 3 weeks, frozen 10 μm thick midsagittal sections were stained with Safranin O / Fast Green and imaged at 10x on a Nanozoomer (Hamamatsu, Japan). Histopathological scoring followed an established protocol for degeneration in four compartments of the IVD including the NP, AF, end plate, and interface/boundary regions 59. Mean degeneration scores from three independent investigators (n=3/sex/genotype/surgery, N=24 total) were used for analysis.

Structural Quantification of Nerve and Vascular Features by Immunohistochemistry

Spines from the animals were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for approximately 48 hours, washed 6 times for 15 minutes each in 1X PBS, and subsequently demineralized in 14% EDTA for 10-14 days. After which, samples were washed 8-10 times for 15 minutes in 1X PBS and serially infiltrated with 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose solutions for 1 hour each prior to optimal cutting temperature (OCT) infiltration and freezing for cryosectioning. Section thickness was 50 μm to provide a semi-3-dimensional visualization of the neuronal and vascular morphology. Serial sections were collected with CryoJane adhesive slides to adhere tissue to the slide during IHC staining with tissues being stored at −80°C prior to antibody staining.

To stain for Protein Gene Product 9.5 (PGP9.5), Endomucin, and DAPI counter stain, a 4-day protocol60 was followed whereby slides were dried at room temperature for 30 minutes and washed in PBS 2 times for 5 minutes. A PAP pen was used to create a hydrophobic perimeter around the tissue and allow for direct pipetting of reagents onto the slides to avoid tissue loss from vertical slide immersion. Slides were blocked with 10% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The primary PGP9.5 antibody (Millipore Cat # Ab1761) at a 1:1000 dilution and Endomucin antibody (Cat #14-5851-85) at a 1:500 dilution was added to 1% normal donkey serum in a TNT (Tris-NaCl-Tween) buffer and incubated 48 hours at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Samples were then washed 3 times for 5 minutes in TNT buffer prior to incubation of a PGP9.5 secondary antibody (Jackson Cat #711-545-152) at 1:1000 concentration and 488nm fluorophore and Endomucin secondary antibody (Jackson Cat #712-605-153) at 1:1000 concentration and 657nm fluorophore in 1% normal donkey serum in TNT buffer for 24 hours at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Samples were washed 3 times with TNT for 5 minutes prior to DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich D9542) at 1:1000 for 5 minutes at room temperature. A final wash with TNT 3 times for 5 minutes was done prior to cover slipping and subsequent sealing of the slides with Fluoromount-G a day later (Thermo Cat:00-4958-02).

To confirm that the PGP9.5 positive structures within the IVD accurately captured the sensory neurons population, we conducted a direct comparison of the PGP9.5 straining of an injured intervertebral disc in a Nav1.8 td Tomato reporter mouse and found the Nav1.8+ features accounted for 88% of the PGP9.5+ features with a spatial colocalization correlation of R=0.86 (Figure S3). The sodium-sensitive ion channel Nav1.8 is highly specific to sensory neurons 61-63.

DAPI, PGP9.5, and Endomucin helped visualize, respectively, cell nuclei, broad neural populations, and endothelial cells of vasculature via a confocal microscope (Leica, USA) at 2.5 μm focal depth increments with 10x magnification and 2048x2048 resolution and 600 speed with 2 frame averaging. Excitation and emission wavelengths were set as follows: DAPI excitation 405nm and emission 414-450 nm, PGP9.5 excitation 488nm and emission 498-530 nm, and Endomucin excitation 635nm and emission 650-725 nm. Note that there was no overlap between the Ai9 tdTomato reported with excitation of 554 and emission of 581nm. Neurite and vessel quantification of the outer AF were performed on max projections of a Z-stack with Fiji (ImageJ), with lengths on or within the AF and the surrounding fibrous tissue calculated from the Neuroanatomy SNT plugin and with depths calculated normal to the peripheral edge of the AF. PGP9.5 staining showed some non-specific regions so was only not included if neuronal morphology was apparent.

To quantify spatial coupling of neurites and vessels, an automated MATLAB program was developed to measure lengths and depths and calculate colocalization lengths and a colocalization ratio based on distance from the rare neurite features. Spatial coupling was defined as vessels within 30 μm from neurites and based on the distance between two adjacent lamellae as lamellar structure and proximity likely impact the transmission of neurovascular coupling signaling.

Neuropeptide Immunostaining of the Dorsal Root Ganglia

Frozen DRG sections, isolated from L1-L3 were processed for immunohistochemistry using a standardized protocol across all targets. Briefly, slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing in 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.6), non-specific binding was minimized through sequential blocking steps with 0.005% BSA in Tris and 10% normal goat serum. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies—anti-TrkA (1:100, Alomone Labs #ANT-018), anti-TRPA1 (1:200, Alomone Labs #ACC-037), or anti-TRPV1 (1:500, Abcam #ab6166)—diluted in Tris-BSA. After rinsing, a goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:300, Invitrogen #A11006) was applied for 4 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Nuclear counterstaining was performed using DAPI (1:5 dilution in 0.1 M Tris), and slides were mounted prior to imaging. DRG immunohistochemical images were quantified using the custom Python software, DRGVisual. Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) was applied to enhance the contrast of the images. The processing began with Canny edge detection to refine the segmentation and ensure accurate depiction of cell boundaries. Following edge detection, seed points within the cells were identified to indicate the center of the cells, and diameters were drawn to estimate each cell's maximum size. Cell regions were grown using a projection-based region-growing algorithm that expands the region from each seed point by examining neighboring pixels and including them in the region if they meet criteria based on intensity and connectivity. For each cell, the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated by subtracting the background intensity from each pixel’s intensity within the cell region and summing the total fluorescence across the cells for each ion channel.

3D Structural Evaluation of Intervertebral Disc Structure Using Contrast-enhanced μCT

At 3 weeks post lumbar intervertebral disc injury, in vivo μCT was used to evaluate structural changes of the intradiscal space (VivaCT, 45 kVp, 177 uA, 300 ms integration time, 10 μm voxel) with isoflurane inhalation (2-3% v/v). Disc height was calculated in ImageJ as the average of 5 measures across the midsagittal view 20. To confirm that the loss of VEGFA did not affect the structure of the IVD, we examined the uninjured L4-L5 and L6-S1 IVDs between the VEGFA-null and the WT animals. Additionally, we examined the injured L5-L6 IVD level to ensure that the VEGFA-null animals were susceptible to injury-mediated degeneration. A 2-tailed t-test was used to determine differences between groups.

The structural changes at this 3-week post injury time point were further evaluated using the ex vivo contrast-enhanced micro-computed tomography (CEμCT). Ioversol was used as a contrast agent to highlight the water-rich nucleus pulposus 64. The fresh IVDs were immersed in 50% Ioversol (OptiRay 350, Guerbet Pharma) at 37°C for 24 hours before imaging. The Scanco40 μCT system (Zurich, Switzerland) scanned samples at 45 keVp, 177 μA, 10.5 μm voxel size, and 300 ms integration after the incubation 65. Groups were n=3 mice/sex/genotype/injury. Total disc ROI and nucleus pulposus ROI were contoured using the MATLAB graphical user interface from Washington University Musculoskeletal Image Analyses (github.com). NP hydration, a ratio of nucleus attenuation to total disc attenuation (NI/DI), was calculated along with volumes and disc height index, DHI, as an average of 5 height measures in a midsagittal slice over the disc width.

Biomechanical Assessment of the Intervertebral Disc

Mechanical behavior of the IVDs using dynamic compression testing under displacement control was conducted using a BioDent reference point indenter (Active Life Scientific) 66. After CEuCT, these samples (n=3 mice/sex/genotype/injury) were mechanically tested with the strain rate calculated from the 5-point average disc height. FSUs were affixed to aluminum platens and immersed in a phosphate-buffered saline bath at room temperature and preloaded to 0.25N. A sinusoidal compressive waveform at 10% strain and 1 Hz frequency was applied for 20 cycles. The average stiffness was calculated from the second through the final loading cycles and the loss tangent, or dissipation factor, was calculated from the phase angle between load and displacement data.

Behavioral Assessments

Habituation measures were taken to reduce animal stress during behavioral assessments. Acclimation to room environment prior to assessment was set for 1 hour at the beginning of each behavioral testing week. To avoid additional animal stress, assessments were typically performed twice a day with 1 hour rest between tests between 9am-5pm to minimize diurnal variations in activity 67. All tests were performed by the same laboratory personnel. Baseline data was collected one week prior to surgery and post-operative data collection included a cross-sectional group at baseline, 3, and 12 weeks and a longitudinal group at 3, 6, 9, and 12 weeks. Care was taken to ensure a clean, quiet, and odor-free environment at a controlled temperature (20-23°C). Testing was initiated up to one week prior to the 3- and 12-week time points as the full set of assays took 4-5 days to complete with efforts made to reproduce the order and timing of each test to remove stress on the animals and replicate methods.

Mechanical Sensitivity Measured Using the Von Frey and E-Von Frey

Mechanical sensitivity was measured using the up-down method of the Von Frey test using Semmes Weinstein filaments (Bioseb, France) and an electronic Von Frey (BIOSEB, France) 68,69. Prior to baseline behavioral testing, mice were habituated to the elevated mesh grid chamber for 1 hr. Calibrated filaments were applied to the plantar surface of the hind paw to elicit paw withdrawal or filament buckling 70. Filament Von Frey was done on the left hind paw to focus on the injury response. EVF consisted of maximum force values at withdrawal from the median of the result of 3 trials which were conducted bilaterally, with at least 5 min between testing opposite paws, and at least 10 min between testing the same paw. Post-op measures were normalized to baseline.

Hot and Cold Nociceptive Sensitivity

Mice were subjected to thermal stimulus to measure the temperature sensitivity response 71,72. A hot/cold plate (Bioseb, France) was set to 55±0.5°C or 5±0.5°C and mice were placed individually onto the plate with a transparent enclosure to prevent escape and allow for visibility. The latency to the first sign of nociceptive behavior, either lick of the hind paws or jumping for hot plate and lifting, licking, or shaking of the hind paws for cold plate was recorded with a cutoff time of 20 seconds for hot or 30 seconds for cold to prevent tissue damage. Three repeated measures were collected with >15 minutes between tests to allow for home cage recovery. Values were averaged and normalized to baseline.

Functional Assessments of Performance

Locomotor Function – Rotarod

Assessing motor coordination and balance, the Rotarod performance test challenged mice to a rotating rod apparatus (Bioseb, France) 69,73,74. Prior to testing, mice were trained on the Rotarod at a slow 4 rpm for 2 minutes to ensure baseline capabilities. Mice unable to achieve this baseline capacity were excluded from assessment. On a subsequent day, mice were tested on an accelerating bar from 4 to 40 rpm over a 2-minute period. Latency to fall was recorded for each mouse. Each mouse underwent 5 trials with a >5-minute rest period between trials to reduce fatigue. The best performance of the 5 trials was used for data analysis and normalized to baseline when possible.

Open Field Testing

In the open field test, designed to evaluate exploratory passive behavior, mice were individually introduced into the center of an open field arena (40 cm x 40 cm, with 30 cm high walls) equipped with an automated tracking system (Omnitech Electronics, Columbus, OH) 69,73,74. The apparatus featured an array of infrared sensors for precise movement tracking over a 60-minute test period. Behavioral parameters recorded included total distance traveled and instances of vertical rearing, among others. The total distance and rearing events were reported over 60 minutes.

Strength

Inverted Wire Hang Endurance

In the wire hang behavioral test, mice were evaluated for neuromuscular strength and endurance 75. The apparatus consisted of a wire mesh (2 mm diameter) suspended above a soft bedding layer to ensure a safe landing for the mice. Each mouse was gently held by the base of the tail and allowed to grasp the wire at a 60° incline before the mesh was inverted to 180°. The duration the mouse remained suspended inverted was recorded up to a maximum of 2 minutes. A minimum 5-minute rest was given between trials. The maximum time of three trials was recorded.

Grip Strength

Grip strength, a measure of neuromuscular strength, was measured using a uniaxial grip force tester (Bioseb, France) 76. Hind paw grip strength assessed mechanical strength as the mouse was gently restrained and allowed to freely grab and hold a bar with both hind paws. Maximum force was recorded as the tail was pulled in a steady manner to avoid rate-dependent effects. A brief rest period, >15 sec, was given between each of the 5 repeated trials. Average strength was reported normalized to body weight at the time of testing and normalized to baseline.

Cell Culture

Human Primary IVD Cell Culture

Human intervertebral disc cells were isolated from the disc tissue of eight patients (mean age ± SD = 68.5 ± 8.1; female:male = 5:3; mean Pfirrmann grade ± SD = 3.5 ± 0.7) removed during elective discectomy surgeries (Table S3). Human biospecimens were obtained under IRB Exemption Category 4, in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines for research using de-identified, previously collected samples, as described in prior studies 77,78 . Tissue specimens were placed in sterile Ham’s F-12 medium (F-12; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Gibco-BRL) and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL). Disc tissue was washed three times with Hank’s balance salt solution (HBSS; Gibco-BRL) containing 1% P/S to remove blood and other bodily contaminants prior to isolation. Specimens were minced and digested for 60 min at 37°C under gentle agitation in F-12 medium containing 1% P/S, 5% FBS, and 0.2% pronase (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). The specimens were rinsed three times with HBSS and 1% P/S and incubated overnight in a solution of F-12 medium containing 1% P/S, 5% FBS, and 0.025% collagenase I (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO). A sterile nylon mesh filter (70 μm pore size) was used to separate suspended cells from the remaining tissue debris. Isolated cells were centrifuged (2000 rpm, 5 min) and resuspended in F-12 medium with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. Cells were plated in a 75-cm2 culture flask (VWR Scientific Products, Bridgeport, NJ) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, 20% O2 in a humidified incubator. Culture medium was changed three times weekly, and cultures grew to 90% confluence. Cells were then trypsinized (0.05% trypsin/ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid; Gibco-BRL) and re-plated (6 x 105 cells/mL) in 75-cm2 culture flasks.

Immortalized Human Microvascular Endothelial Cell (HMEC-1) Culture

HMEC-1(CRL-3243; ATCC, Masassas, VA) were cultured in MCDB 131 medium (10372019; Gibco-BRL) containing 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (PHG0311; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 500 mg/mL hydrocortisone (H0396; Sigma), 1% P/S, 2 mM L-Glutamine and supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells at passage number 5-10 were plated in 75 cm2 culture flasks and grown to 90% confluence.

Immortalized Human Neuroblastoma Cell (SH-SY5Y) Culture

The SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line (CRL-2266; ATCC) was cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM; ATCC, Manassas, VA) and Ham’s F12 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S in a 5% carbon dioxide humidified incubator at 37°C. Cells at passage number 5-10 were plated in 75 cm2 culture flasks and grown to 90% confluence.

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-siRNA Transfection

Isolated human IVD cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 3x105 cells per well 24 hours prior to transfection. VEGF-specific siRNA (sc-29620; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Tx) and scrambled control siRNA- FITC (sc-36869; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were transfected into DCs using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Catalog #: 13778100, Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer's protocol. The final concentration of siRNA in the culture medium was 50 pM. The effectiveness of transfection was evaluated by checking the amount of the secreted VEGF in media using ELISA (DY293; R&D system, Minneapolis, MN) and confirming transfection of control siRNA by FITC fluorescence with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted scope at 10x.

Co-culture between IVD cells and HMEC-1 (ECs) Cells

IVD cells were plated in a 6 well plate and transfected with either control, scrambled siRNA (Scram siRNA) or with VEGF specific siRNA (VEGF siRNA). Medium with 1% FBS and recombinant human interleukin-1β (IL-1β; R&D Systems) at 1 ng/mL was added to stimulate Scram siRNA (IL-1β+Scram siRNA) and VEGF siRNA (IL-1β+VEGF siRNA) transfected IVD cells for 24 hours. After stimulation, HMEC-1 cells “ECs” that were plated for 24 hours on 1 μm pore co-culture inserts (Thincert cell culture insert; Greiner, Monroe, NC) at a density of 3x105 cells were inserted to the wells containing Scram siRNA or VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells with MCDB media plus 1% FBS. ECs co-cultured with stimulated Scram siRNA treated IVD cells are denoted as ECIL-1β+Scram siRNA and ECs co-cultured with stimulated VEGF siRNA treated IVD cells are denoted as ECIL-1β+VEGF siRNA. Naïve ECs that did not undergo co-culturing were used as a control group. ECs were analyzed via a Matrigel tube formation assay, multiplex (Human Angiogenesis & Growth Factor 17-Plex, Human Cytokine Panel A 48-Plex, Human MMPTIMP 13-Plex. MilliporeSigma) and RNA sequencing (Figure S4).

Co-culture Between IVD cells and SH-SY5Y Cells (NCs)

SH-SY5Y neuronal cells “NCs” were plated at a density of 1.5 x 105 cells per well in a 6 well plate and cultured for 48 hours prior to the co-culture experiment. For co-culturing, non-stimulated IVD cells “naive”, IL-1β+Scram siRNA, and IL-1β+VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells were plated on the co-culture insert at a density of 3.0 x 105 cells and co-cultured for 48 hours with NCs. NCs were analyzed via a neurite outgrowth assay and RNA sequencing. (Figure S5)

RNA Preparation and Sequencing

Post co-culture experiments, HMEC-1 and SH-SY5Y cells were lysed (TRIzol reagent, Fisher Scientific), and total RNA was extracted (Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep Kit, Zymo Research). Samples were prepared according to library kit manufacturer’s protocol, indexed, pooled, and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq X Plus. Basecalls and demultiplexing were performed with Illumina’s DRAGEN and BCLconvert version 4.2.4 software. RNA-seq reads were then aligned to the Ensembl release 101 primary assembly with STAR version 2.7.9a1. Gene counts were derived from the number of uniquely aligned unambiguous reads by Subread:featureCount version 2.0.32. Isoform expression of known Ensembl transcripts were quantified with Salmon version 1.5.23. Sequencing performance was assessed for the total number of aligned reads, total number of uniquely aligned reads, and features detected. The ribosomal fraction, known junction saturation, and read distribution over known gene models were quantified with RSeQC version 4.04. All gene counts were then imported into the R/Bioconductor package EdgeR5 and TMM normalization size factors were calculated to adjust for samples for differences in library size. Ribosomal genes and genes not expressed in the smallest group size (minus one sample greater than one count-per-million) were excluded from further analysis. The TMM size factors and the matrix of counts were then imported into the R/Bioconductor package Limma6. Weighted likelihoods based on the observed mean-variance relationship of every gene and sample were then calculated for all samples and the count matrix was transformed to moderated log 2 counts-per-million with Limma’s voomWithQualityWeights7. The performance of all genes was assessed with plots of the residual standard deviation of every gene to their average log-count with a robustly fitted trend line of the residuals. Differential expression analysis was then performed to analyze differences between conditions and the results were filtered for only those genes with Benjamini-Hochberg false-discovery rate adjusted p-values less than or equal to 0.05. The raw data files are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus database: GSE294577

See Excel files

Table S8A,B and S9A,B: DEGs and GO terms for Endothelial and Neuronal Cells

Multiplex Protein Assay

The supernatant from naive ECs and those co-cultured with IL-1β+Scram siRNA and IL-1β+VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells was collected and analyzed by multiplex protein assay (Human Angiogenesis & Growth Factor 17-Plex, Human Cytokine Panel A 48-Plex, Human MMPTIMP 13-Plex, Eve Technologies, Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Out of range values or results < 2pg/ml were not included.

Matrigel Tube Formation Assay

To determine the vessel formation capacity between ECs cultured with conditioned media (CM) collected from IL-1β+Scram siRNA versus IL-1β+VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells, a Matrigel tube formation assay was performed. Matrigel matrix (356231; Corning Inc., Corning, NY), a gelatinous protein mixture that mimics the extracellular matrix, was used to coat a 24-well plate following the manufacturer's protocol. HMEC-1 cells at the density of 3 x 104 cells per well were suspended in the CM collected from IL-1β+Scram siRNA or IL-1β+VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells for 48 hours and plated onto each Matrigel coated well. Images were acquired at 6 hours and 12 hours post plating via a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted scope at 10x. To assess the ability of tube formation by each conditioned media and time point, the numbers of closed loops were counted.79

Neurite Outgrowth Assay

The number and length of neurites from NCs co-cultured with non-stimulated IVD cells “naive”, IL-1β+Scram siRNA, or IL-1β+VEGF siRNA transfected IVD cells were compared. Neurite outgrowth was quantified using ImageJ software. For each neuron, neurite number and length were counted manually. Neurite length was measured from the edge of the cell body to the tip of the neurite. The average neurite length per neurite was calculated for each treatment group, with all measurements expressed in microns.

Statistical and Bioinformatics Analyses

Statistical comparisons on repeated measures, IE longitudinal behavioral assays, were done using a linear mixed effect model to assess surgery (Sham/Injured), genotype (WT/VEGFA-null), weeks after surgery (3/12), sex (M/F), and surgery (Naïve/Sham). Linear mixed effect models were initiated with all factors and reduced in complexity as factors were found to be not significant. Additionally, focused questions were modeled to assess injured groups with genotype and week. A 2 or 3 factor ANOVA was used on terminal measures such as Ex Vivo CEμCT, biomechanics, disc degeneration scoring, or immunohistochemistry to assess effects of injury, genotype, and sex. ANOVA pairwise comparisons were done with the Fisher’s Least Significant Difference method. Survival curves implemented Mantel-Cox test while binary penetration results used a Fisher’s exact test. Simple pairwise comparisons were done using a Welch’s t-test when appropriate. Appropriate adjustments were made in the respective statistical models for unequal variances and non-normal distributions. The ROUT outlier test with Q=0.1% removed definitive outliers within groups.80 R and GraphPad Prism were used to model results.

For gene ontology analyses, biological pathways enriched by the upregulated and downregulated DEGs were identified by using the Panther Classification System with version Panther 19.0 by using the statistical overrepresentation test. For ECs, an adjusted p value of p < 0.05 and logFC of 0.41 was used to identify statistically significant DEGs with at least a 50% increase in fold change of the treatment group when compared to the control. For neuronal cells, an adjusted p value of p < 0.10 and logFC of 0.41 was used to identify statistically significant DEGs with at least a 50% increase in fold change of the treatment group when compared to the controls. The full list of all DEGs and GO terms for the endothelial cells comparisons are listed in Tables S8A and S8B and for the neuronal cell comparisons are listed in Tables S9A and S9B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge the support of the Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center Structure and Function Core (Michael Brodt); Histology Core (Crystal Idleburg and Samantha Coleman); and Animal Behavior and Function Core. We also acknowledge Kelsey Collins and Washington University Pain Center Judith Golden for their training in behavioral assessments of pain. We thank Jenny McKensie and Evan Buettmann for assistance in working with the VEGFA-null animals. We thank the Washington University Genomics Technology Access Core (GTAC), and the Eve-tech for the multiplex ELISA analysis.

Funding:

This work was conducted with funding support from National Institute of Health:

National Institutes of Health grant R21AR081517 (ST/MG)

National Institutes of Health grant R01AR074441 (ST)

National Institutes of Health grant R01AR077678 (LS/ST)

National Institutes of Health grant P30AR074992 (MS)

National Institutes of Health grant S10OD028573 (MS)

List of Abbreviations

- AF

Annulus Fibrosus

- Ai9

Cre-reporter expressing tdTomato fluorescent protein (Rosa-CAG-LSL-tdTomato

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- CEμCT

Contrast-Enhanced Micro-Computed Tomography

- CLBP

Chronic Low Back Pain

- CM

Conditioned Media

- CTCF

Corrected Total Cell Fluorescence

- C57BL/6J

Common inbred mouse strain

- DAPI

4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DNA stain)

- DEG

Differentially Expressed Gene

- DHI

Disc Height Index

- DRG

Dorsal Root Ganglion

- EC

Endothelial Cell (HMEC-1)

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (chelating agent)

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- EMCN

Endomucin (endothelial cell marker)

- EMEM, ATCC

Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium, from American Type Culture Collection

- ERT2

Modified Estrogen Receptor Ligand Binding Domain (used in tamoxifen-inducible Cre systems

- EVF

Electronic Von Frey

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- FITC

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate dye

- FSU

Functional Spinal Unit

- HBSS

Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution

- HMEC-1

Human Microvascular Endothelial Cell Line

- IL1β

Interleukin 1 Beta

- IVD

Intervertebral Disc

- LBP

Low Back Pain

- LoxP

Locus of X-over P1 (recombination sites for Cre-Lox systems

- LSD

Least Significant Difference (statistical post hoc test

- MCDB

Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology

- Nav1.8

Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel (gene SCN10A) expressed in nociceptive neurons

- NC

Neuron cells (SH-SY5Y)

- NFkB

Nuclear Factor Kappa B

- NGF

Nerve Growth Factor

- NI/DI

Nucleus Attenuation Intensity/Disc Attenuation Intensity

- NP

Nucleus Pulposus

- OCT

Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound

- PAP

Hydrophobic barrier pen

- PBS

Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- PGP9.5

Protein Gene Product 9.5 (neuronal marker

- P/S

Penicillin/Streptomycin

- ROI

Region of Interest

- SCRAM

Scrambled siRNA (negative control)

- SH-SY5Y

Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line

- siRNA

Small Interfering RNA

- SNT

Simple Neurite Tracer (ImageJ plugin)

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

- TNT

Tris-NaCl-Tween buffer

- TrKA

Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase A (NGF receptor)

- TRPA1

Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1

- TRPV1

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1

- UBC

Ubiquitin

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- WT

Wild Type

Footnotes

Competing interests:

Provisional Patent: 020859/US

Title: VEGFA INHIBITORS AS A TREATMENT FOR CHRONIC MECHANICAL ALLODYNIA

Co-inventors: RSP, HJM, MCG, SYT

Data and materials availability: All data, code, and materials used in the analysis must be available in some form to any researcher for purposes of reproducing or extending the analysis. Include a note explaining any restrictions on materials, such as materials transfer agreements (MTAs). Note accession numbers to any data relating to the paper and deposited in a public database; include a brief description of the data set or model with the number. If all data are in the paper and supplementary materials, include the sentence

REFERENCES

- 1.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. Mar 2006;15 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S192–300. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. Jun 9 2018;391(10137):2356–2367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H, Haldeman S. Behavior-Related Factors Associated With Low Back Pain in the US Adult Population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Jan 1 2018;43(1):28–34. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2014;73(6):968–74. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shokri P, Zahmatyar M, Falah Tafti M, et al. Non-spinal low back pain: Global epidemiology, trends, and risk factors. Health Sci Rep. Sep 2023;6(9):e1533. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collaborators GBDLBP. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990-2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. Jun 2023;5(6):e316–e329. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00098-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rannou F, Lee TS, Zhou RH, et al. Intervertebral disc degeneration: the role of the mitochondrial pathway in annulus fibrosus cell apoptosis induced by overload. Am J Pathol. Mar 2004;164(3):915–24. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63179-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y, Egan B, Wang J. Genetic Factors in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Genes Dis. Sep 2016;3(3):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang F, Cai F, Shi R, Wang XH, Wu XT. Aging and age related stresses: a senescence mechanism of intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. Mar 2016;24(3):398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luoma K, Riihimäki H, Luukkonen R, Raininko R, Viikari-Juntura E, Lamminen A. Low Back Pain in Relation to Lumbar Disc Degeneration:. Spine. February/2000 2000;25(4):487–492. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002150-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban JP. Swelling pressure of the lumbar intervertebral discs: influence of age, spinal level, composition, and degeneration. Spine. Feb 01 1988;13(2):179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckwalter JA. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Jun 1 1995;20(11):1307–14. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams MA, Freeman BJ, Morrison HP, Nelson IW, Dolan P. Mechanical initiation of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Jul 1 2000;25(13):1625–36. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setton LA, Chen J. Mechanobiology of the intervertebral disc and relevance to disc degeneration. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume. 2006-April 2006;88 Suppl 2:5257. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binch ALA, Fitzgerald JC, Growney EA, Barry F. Cell-based strategies for IVD repair: clinical progress and translational obstacles. Nat Rev Rheumatol. Mar 2021;17(3):158–175. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00568-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binch ALA, Cole AA, Breakwell LM, et al. Nerves are more abundant than blood vessels in the degenerate human intervertebral disc. Arthritis Research & Therapy. December/2015 2015;17(1)doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0889-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato J, Inage K, Miyagi M, et al. Inhibiting Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Injured Intervertebral Discs Attenuates Pain-Related Neuropeptide Expression in Dorsal Root Ganglia in Rats. Asian spine journal. Aug 2017;11(4):556–561. doi: 10.4184/asj.2017.11.4.556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmeliet P, Ruiz de Almodovar C. VEGF ligands and receptors: implications in neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. May 2013;70(10):1763–78. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1283-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falk T, Gonzalez RT, Sherman SJ. The yin and yang of VEGF and PEDF: multifaceted neurotrophic factors and their potential in the treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. Aug 5 2010;11(8):2875–900. doi: 10.3390/ijms11082875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walk RE, Moon HJ, Tang SY, Gupta MC. Contrast-enhanced microCT evaluation of degeneration following partial and full width injuries to the mouse lumbar intervertebral disc. Sci Rep. Sep 16 2022;12(1):15555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19487-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leimer EM, Gayoso MG, Jing L, Tang SY, Gupta MC, Setton LA. Behavioral Compensations and Neuronal Remodeling in a Rodent Model of Chronic Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Sci Rep. Mar 6 2019;9(1):3759. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39657-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millecamps M, Stone LS. Delayed onset of persistent discogenic axial and radiating pain after a single-level lumbar intervertebral disc injury in mice. PAIN®. Sep 01 2018;159(9):1843. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rickman M, Ghim M, Pang K, et al. Disturbed flow increases endothelial inflammation and permeability via a Frizzled-4-beta-catenin-dependent pathway. J Cell Sci. Mar 15 2023;136(6)doi: 10.1242/jcs.260449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dejana E. The role of wnt signaling in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Circ Res. Oct 15 2010;107(8):943–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohela M, Saaristo A, Veikkola T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenic growth factors, receptors and therapies. Thromb Haemost. Aug 2003;90(2):167–84. doi: 10.1160/TH03-04-0200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell. Feb 19 2010;140(4):460–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Li X, et al. Angiogenesis stimulated by PDGF-CC, a novel member in the PDGF family, involves activation of PDGFR-alphaalpha and -alphabeta receptors. FASEB J. Oct 2002;16(12):1575–83. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0319com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. Mar 2007;8(3):221–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. Apr 2 2010;141(1):52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panopoulos AD, Watowich SS. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: molecular mechanisms of action during steady state and 'emergency' hematopoiesis. Cytokine. Jun 2008;42(3):277–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. Jul 2008;8(7):533–44. doi: 10.1038/nri2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. The Chemokine Superfamily Revisited. Immunity. May/2012 2012;36(5):705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appay V, Rowland-Jones SL. RANTES: a versatile and controversial chemokine. Trends Immunol. Feb 2001;22(2):83–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01812-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, Millecamps M, Foster DZ, Stone LS. Long-term histological analysis of innervation and macrophage infiltration in a mouse model of intervertebral disc injury-induced low back pain. J Orthop Res. Jun 2020;38(6):1238–1247. doi: 10.1002/jor.24560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freemont AJ, Peacock TE, Goupille P, Hoyland JA, O apos Brien J, Jayson MI. Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain. Lancet. Jul 19 1997;350(9072):178–181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02135-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brisby H. Pathology and possible mechanisms of nervous system response to disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Apr 2006;88 Suppl 2:68–71. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]