Abstract

Purpose

Uterine sarcoma is a rare malignancy with the worst prognosis of all uterine cancers. This study evaluated the prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of patients with this disease.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on 127 patients with histologically verified uterine sarcoma who were treated and followed at the Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) from 1989 to 2007.

Results

Histological analyses revealed that 37 patients had endometrial stromal sarcoma, 44 had malignant mixed mullerian tumors and 46 had leiomyosarcoma. Surgical stages, as defined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system, were I in 82 patients, II in 6 patients, III in 18 patients and IV in 19 patients. All patients underwent surgical treatment and 72 patients received adjuvant therapy. The 10-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was 30% and the 10-year overall survival (OS) rate was 48%, with a mean follow-up time of 38 months (ranging from 1 to 212 months). Adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy had limited impact on the outcome of early-stage disease. However, patients with advanced-stage disease who received adjuvant chemotherapy had significantly longer OS times. A multivariate analysis revealed that FIGO stage (P = 0.025), depth of myometrial invasion (P = 0.004), and complete cytoreduction (P = 0.030) were significantly associated with DFS, while menopausal status (P = 0.044), FIGO stage (P = 0.016), depth of myometrial invasion (P = 0.029), and lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI) (P = 0.020) were significantly associated with OS.

Conclusions

This study suggests that complete cytoreduction is important and adjuvant chemotherapy can help achieve favorable prognoses in patients with advanced stage disease. However, postmenopausal status, advanced FIGO stage, deep myometrial invasion, and positive LVSI were associated with poor prognosis.

Keywords: Uterine sarcoma, Endometrial stromal sarcoma, Malignant mixed mullerian tumor, Leiomyosarcoma, Prognostic factor, Treatment outcome

Introduction

Uterine sarcomas are rare tumors that account for 1–3% of all malignancies in the female genital tract (Chauveinc et al. 1999) and 3–8% of all malignancies in the uterus (Shumsky et al. 1994; Brooks et al. 2004). This heterogeneous group of tumors originates from uterine mesodermal tissue. In order of decreasing incidence, the most common histological types of uterine sarcomas are malignant mixed mullerian tumors (MMMT) and leiomyosarcomas (LMS), which together account for approximately 85% of all cases; and endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS), which account for the remaining 15% of cases. Uterine sarcomas are among the most aggressive and malignant tumors that can arise in the uterus. However, because this malignancy is so rare and pathologically diverse, optimal management strategies and prognostic factors have not been well established. Therefore, this study evaluated the treatment outcomes of patients with uterine sarcoma to analyze the prognostic factors and identify optimal treatment modalities.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients with pathologically verified uterine sarcoma who were treated and followed from 1989 to 2007 at the Asan Medical Center (AMC; Seoul, Korea) were identified from a computerized database and cancer registry. Patients who did not receive primary treatment or follow-up care at the AMC were excluded from the analysis. Demographic data obtained from each patient’s medical record included age, menopausal status, body mass index and parity, as well as the patient’s histories of cancer, medical disease, surgery or radiation therapy on the pelvis, and use of tamoxifen. We also obtained clinical data on the patient’s symptoms and signs at the time of diagnosis, as well as the presence of tumor markers; the outcomes of diagnostic procedures and surgical treatments; the presence of residual tumor cells after surgery; the histologic type, size, and grade of tumors; the presence of lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI); peritoneal cytology; lymph node involvement; surgical stage, as determined using the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) system for endometrial cancer; adjuvant therapy; recurrence; and treatment at the times of recurrence and death. Pathological slides were reviewed by two experienced pathologists and the clinicopathological prognostic factors and treatment outcomes were analyzed. The AMC does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board for retrospective chart reviews; hence this analysis was exempted from the approval process.

Definitions and statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) time was calculated as the number of months from the date of surgery to either the date of death or the date censored. Disease-free survival (DFS) time was calculated as the number of months from the date of surgery to either the date of recurrence or the date censored. Survival curves and rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method (Kaplan and Meier 1958). Differences in survival were assessed using the log-rank test for categorical factors (Mantel 1966) and Cox’s proportional hazards model for continuous factors in univariate analysis (Cox 1972). A multivariate analysis was performed using Cox’s proportional hazards model to determine the survival benefit when the model was adjusted for favorable prognostic variables. Stepwise model-selection methods were used to select factors for inclusion in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Frequency distributions were compared using Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests, and mean and median values between groups were compared using a Student’s T-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 in a two-sided test indicated a significant difference. Data were analyzed using SPSS software for Windows (version 11.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Study population

We identified 133 patients with uterine sarcoma who were treated and followed at the AMC from 1989 to 2007. Six patients were excluded due to insufficient follow-up data and the remaining 127 patients were included in the final analysis. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 49.8 years (ranging from 22 to 79 years). The mean body mass index was 23.9 kg/m2 (range: 16–35 kg/m2). Sixty-one patients were postmenopausal. One patient had a history of prior pelvic radiotherapy and four patients had received tamoxifen, owing to prior breast cancer. Most patients presented with symptoms, vaginal bleeding being the most common. Sixty-five patients had preoperative measurements of CA 125 levels in blood and 15 of these patients had elevated CA 125 levels.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics (N = 127)

| Characteristics | Total (n = 127) | ESS (n = 37) | MMMT (n = 44) | LMS (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [mean (range)] | 49.8 (22–79) | 43.9 (22–64) | 57.1 (23–79) | 47.5 (32–71) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 [mean (range)] | 23.9 (16–35) | 23.5 (17–29) | 24.3 (18–35) | 23.8 (16–32) |

| Parity, n (%) | ||||

| 0–2 | 78 (61.4%) | 22 (59.5%) | 23 (52.3%) | 33 (71.7%) |

| >2 | 49 (38.6%) | 15 (40.5%) | 21 (47.7%) | 13 (28.3%) |

| Menopause, n (%) | ||||

| No | 66 (52%) | 30 (81.1%) | 7 (15.9%) | 29 (63%) |

| Yes | 61 (48%) | 7 (18.9%) | 37 (84.1%) | 17 (37%) |

| Medical disease, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 16 (12.6%) | 5 (13.5%) | 6 (13.6%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (6.3%) | 2 (5.4%) | 4 (9.1%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Othersa | 7 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.1%) | 3 (6.5%) |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | ||||

| Breast cancer | 4 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.8%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Colorectal cancer | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gastric cancer | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Thyroid cancer | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prior pelvic radiotherapy, n (%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Tamoxifen used, n (%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6.8%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 9 (7.1%) | 1 (2.7%) | 3 (6.8%) | 5 (10.9%) |

| Vaginal bleeding | 75 (59.1%) | 27 (73%) | 30 (68.2%) | 18 (39.1%) |

| Palpable mass | 22 (17.3%) | 5 (13.5%) | 7 (15.9%) | 10 (21.7%) |

| Abdominal pain | 21 (16.5%) | 4 (10.8%) | 4 (9.1%) | 13 (28.3%) |

| Preoperative CA 125, n (%) | ||||

| Not elevated | 50 (39.4%) | 10 (27%) | 22 (50%) | 18 (39.1%) |

| Elevated | 15 (11.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | 11 (25%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Not checked | 62 (48.8%) | 25 (67.6%) | 11 (25%) | 26 (56.5%) |

aIncluding bronchial asthma, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation

Our study included 83, 6, 19 and 19 patients with FIGO stages I, II, III and IV disease, respectively. Thirty-seven patients had ESS, 44 had MMMT, and 46 had LMS. Tumor characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Tumor characteristics (N = 127)

| Characteristics | Total (n = 127) | ESS (n = 37) | MMMT (n = 44) | LMS (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIGO stage, n (%) | ||||

| I | 83 (65.4%) | 27 (73%) | 23 (52.3%) | 33 (71.7%) |

| II | 6 (4.7%) | 2 (5.4%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| III | 19 (15%) | 4 (10.8%) | 11 (25%) | 4 (7.8%) |

| IV | 19 (15%) | 4 (10.8%) | 6 (13.6%) | 9 (79.6%) |

| Grade, n (%) | ||||

| I | 49 (38.6%) | 32 (86.5%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (37%) |

| II–III | 78 (61.4%) | 5 (13.5%) | 44 (100%) | 29 (63%) |

| Tumor size, n (%) | ||||

| Mean (range), cm | 7.1 (0.8–21) | 5.3 (0.8–20) | 6.4 (1–17) | 9.3 (2.7–21) |

| <10 cm | 105 (82.7%) | 36 (97.3%) | 38 (86.4%) | 31 (67.4%) |

| >10 cm | 22 (17.3%) | 1 (2.7%) | 6 (13.6%) | 15 (32.6%) |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%) | ||||

| <50% | 32 (25.2%) | 7 (18.9%) | 20 (45.5%) | 5 (10.9%) |

| >50% | 95 (74.8%) | 30 (81.1%) | 24 (54.5%) | 41 (89.1%) |

| LVSI, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 95 (74.8%) | 27 (72.9%) | 29 (65.9%) | 39 (84.8%) |

| Positive | 32 (25.2%) | 10 (27%) | 15 (34.1%) | 7 (15.2%) |

| Cytology, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 60 (47.2%) | 15 (40.5%) | 31 (70.5%) | 14 (30.4%) |

| Positive | 8 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (13.6%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Not done | 59 (46.5%) | 22 (59.5%) | 7 (15.9%) | 30 (65.2%) |

| LN evaluation, n (%) | ||||

| PLND | 28 (22.1%) | 10 (27%) | 16 (34.8%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| PLND + PALND | 37 (29.1%) | 7 (18.9%) | 21 (47.8%) | 9 (20.4%) |

| Not done | 62 (48.8%) | 20 (54.1%) | 7 (15.9%) | 35 (76.1%) |

| LN involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 55 (43.3%) | 15 (40.5%) | 29 (65.9%) | 11 (23.9%) |

| Positive | 10 (7.9%) | 2 (5.4%) | 8 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not available | 62 (48.8%) | 20 (54.1%) | 7 (15.9%) | 35 (76.1%) |

| Ovarian preservation, n (%) | ||||

| No | 80 (63.0%) | 17 (45.9%) | 40 (90.9%) | 23 (50%) |

| Yes | 47 (37.0%) | 20 (54.1%) | 4 (9.1%) | 23 (50%) |

FIGO International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ESS emdometrial stromal sarcoma, MMMT malignant mixed mullerian tumor, LMS leiomyosarcoma, LVSI lymph-vascular space invasion, LN lymph node, PLND pelvic lymph node dissection, PALND paraarotic lymph node dissection

Treatment outcome

All patients underwent primary surgical treatment at our center and tumor cells were completely removed in 114 patients. Procedures performed during surgical management are listed in Table 3. Most patients with MMMT underwent pelvic lymph node dissection and/or paraaortic lymph node dissection. Forty-seven patients (i.e., 38%) did not undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Of these, 43 (i.e., 91.5%) were premenopausal and 40 (i.e., 85.1%) had FIGO stages I–II disease. Seventy-four patients received adjuvant therapy, with 60 receiving chemotherapy, 7 receiving radiation therapy and 7 receiving concurrent chemoradiation therapy (Table 3). The criteria for adjuvant therapy of uterine sarcoma depended on discretion of the gynecologic oncologist. In most cases, chemotherapeutic regimens included a combination of paclitaxel, doxorubicin, ifosfamide and/or platinum (Table 3). The selections of chemotherapeutic regimen also depended on the discretion of gynecologic oncologist. However, chemotherapeutic regimen containing doxorubicin was a preferred regimen for MMMT, and chemotherapeutic regimen containing ifosfamide was a preferred regimen for LMS. After a mean follow-up time of 38 months (ranging from 1 to 212 months), 47 patients had recurrent disease. Eleven patients were diagnosed with pelvic recurrence, 13 patients with peritoneal sarcomatosis, 12 patients with distant metastasis, 8 patients with pelvic recurrence and distant metastases, and 3 patients with peritoneal sarcomatosis and distant metastases. Recurrent disease was treated with chemotherapy in 16 patients, radiation therapy in 3 patients, surgery in 6 patients, chemotherapy and radiation therapy in 2 patients, and surgery followed by chemotherapy in 11 patients. Nine patients refused treatment at the time of recurrence. At the time of our analysis, 36 patients had died from the disease, 7 patients were living with the disease, and 82 patients were living without the disease. The 3-, 5- and 10-year DFS rates were 62, 53 and 30%, respectively. The 3-, 5- and 10-year OS rates were 69, 59 and 48%, respectively.

Table 3.

Surgical management and adjuvant therapy (N = 127)

| Characteristics | Total (n = 127) | ESS (n = 37) | MMMT (n = 44) | LMS (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical management | 127 | 37 | 44 | 46 |

| Procedures performed | ||||

| Hysterectomy | 125 | 35 | 44 | 46 |

| Mass excision | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 79 | 17 | 40 | 22 |

| Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 10 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Pelvic lymph node dissection | 65 | 17 | 38 | 10 |

| Paraaortic lymph node dissection | 36 | 7 | 21 | 8 |

| Omentectomy | 36 | 7 | 21 | 8 |

| Appendectomy | 36 | 12 | 16 | 8 |

| Low anterior resection | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total colectomy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Small bowel resection | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Partial cystectomy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ureteral mass excision | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Not done | 53 | 22 | 10 | 21 |

| Chemotherapy | 60 | 11 | 27 | 22 |

| Radiation therapy | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Concurrent chemoradiation therapy | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Chemotherapeutic regimen | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Paclitaxel + Platinum | 10 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| Paclitaxel + Doxorubicin | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Paclitaxel + Doxorubicin + Platinum | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Doxorubicin + Platinum | 12 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| Ifosfamide + Platinum | 27 | 2 | 16 | 8 |

| Doxorubicin + Ifosfamide + Platinum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other platinum-based regimen | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

ESS Emdometrial stromal sarcoma, MMMT malignant mixed mullerian tumor, LMS leiomyosarcoma

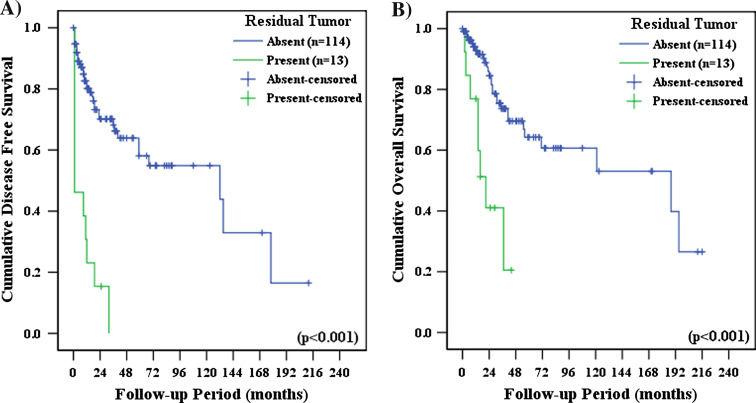

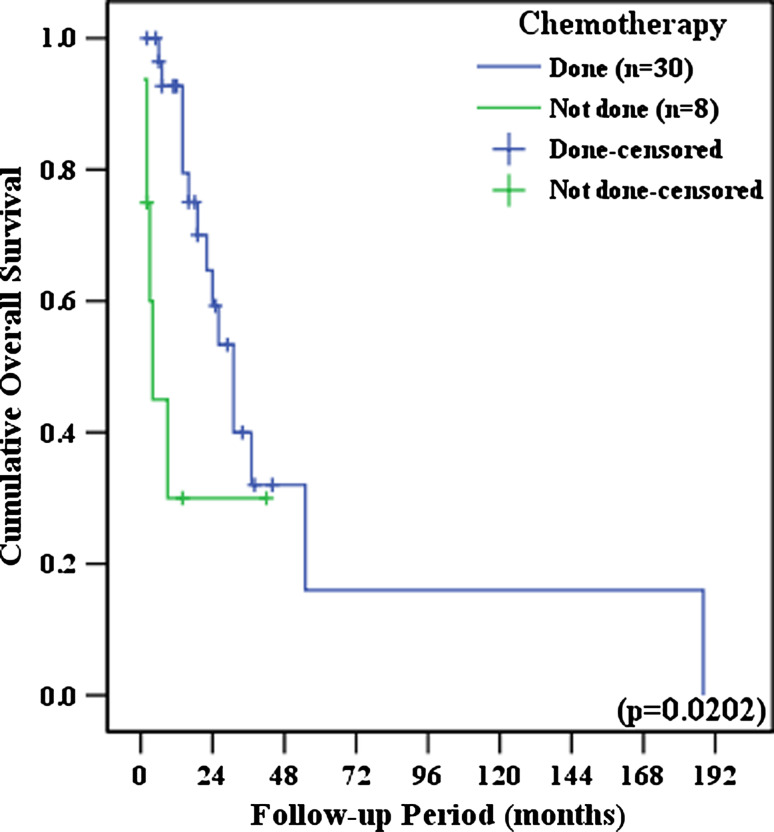

Patients had significantly longer DFS (Odds ratio [O.R.], 5.934; 95% confidence interval [C.I.], 2.983–11.844; P < 0.001) and OS (O.R., 4.589; 95% C.I., 2.014–10.453; P < 0.001) when tumor cells were completely removed during surgery, when compared with patients who still had residual tumor cells following surgery (Fig. 1). No differences in DFS and OS were observed between patients who received adjuvant therapy and who did not receive adjuvant therapy. DFS and OS outcomes were not influenced by adjuvant therapy modality (chemotherapy, radiation therapy or concurrent chemoradiation therapy); and these results held true when each of the histologic subtypes were analyzed separately. There were no significant differences in DFS and OS between patients who received palcitaxel/platinum based chemotherapy and patients who received other chemotherapeutic regimen (P = 0.6203 and P = 0.9104, respectively). In early-stage disease (i.e., FIGO stages I–II), adjuvant therapy and adjuvant therapy modality did not significantly influence DFS and OS. However, in advanced-stage disease (i.e., FIGO stages III–IV), patients who received chemotherapy had significantly longer OS times than patients who did not receive chemotherapy (O.R., 3.200; 95% C.I., 1.121–9.136; P = 0.0202) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

a Disease-free survival and b overall survival, as a function of the presence of residual tumor cells following surgery

Fig. 2.

The effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival in advanced-stage disease (i.e., FIGO stages III–IV)

Prognostic factors

The results of univariate analyses of the relationships between prognostic variables and survival are summarized in Table 4. Menopausal status, advanced FIGO stage, high-grade tumor, deep myometrial invasion, positive LVSI, positive peritoneal cytology, LN involvement, the presence of residual tumor cells after surgery and elevated preoperative CA 125 levels were significantly associated with poor DFS. However, age, parity, histological type, tumor size, LN dissection, ovarian preservation, and adjuvant therapy were not significantly associated with DFS. Menopausal status, advanced FIGO stage, histologic types other than ESS, high-grade tumors, tumors larger than 10 cm, deep myometrial invasion, positive LVSI, positive peritoneal cytology, LN involvement, the presence of residual tumor cells after surgery, and elevated preoperative CA 125 levels were significantly associated with poor OS. In contrast, age, parity, LN dissection, ovarian preservation, and adjuvant therapy did not appear to influence OS.

Table 4.

Prognostic factors for uterine sarcoma (univariate analysis, N = 127)

| Variables | N | Disease free survival | Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P-value | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P-value | |||

| Age (as continuous variable) | 1.010 | 0.984–1.036 | 0.477 | 1.030 | 0.999–1.062 | 0.062 | ||

| Menopause | ||||||||

| No | 66 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 61 | 1.942 | 1.087–3.472 | 0.025 | 2.676 | 1.357–5.278 | 0.005 | |

| Para | ||||||||

| 0–2 | 78 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| >2 | 49 | 1.152 | 0.642–2.068 | 0.635 | 0.841 | 0.418–1.689 | 0.626 | |

| FIGO stage | ||||||||

| I–II | 89 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| III–IV | 28 | 4.471 | 2.453–8.149 | <0.001 | 5.577 | 2.785–11.168 | <0.001 | |

| Histologic type | ||||||||

| ESS | 37 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| MMMT | 44 | 1.940 | 0.906–4.155 | 0.088 | 3.923 | 1.447–10.639 | 0.007 | |

| LMS | 46 | 2.180 | 1.058–4.494 | 0.035 | 3.861 | 1.512–9.857 | 0.005 | |

| Grade | ||||||||

| I | 49 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| II–III | 78 | 2.396 | 1.273–4.511 | 0.007 | 4.649 | 2.010–10.753 | <0.001 | |

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| <10 cm | 105 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| >10 cm | 22 | 1.664 | 0.859–3.225 | 0.131 | 2.721 | 1.350–5.486 | 0.005 | |

| Mm invasion | ||||||||

| <50% | 32 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| >50% | 95 | 5.096 | 1.578–16.456 | 0.006 | 4.973 | 0.188–20.809 | 0.028 | |

| LVSI | ||||||||

| Negative | 95 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 32 | 2.658 | 1.443–4.894 | 0.002 | 4.560 | 2.276–9.139 | <0.001 | |

| Cytologya | ||||||||

| Negative | 60 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 8 | 5.121 | 1.900–13.802 | 0.001 | 5.562 | 1.836–16.853 | 0.002 | |

| LN dissection | ||||||||

| Done | 65 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Not done | 62 | 0.930 | 0.514–1.683 | 0.812 | 1.574 | 0.779–3.182 | 0.207 | |

| LN involvementb | ||||||||

| Negative | 55 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 10 | 2.983 | 1.052–8.458 | 0.040 | 8.112 | 2.371–27.758 | 0.001 | |

| Ovarian preservation | ||||||||

| No | 80 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 47 | 1.481 | 0.808–2.714 | 0.230 | 0.522 | 0.255–1.068 | 0.075 | |

| Residual tumor | ||||||||

| No | 114 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 13 | 5.943 | 2.983–11.844 | <0.001 | 4.589 | 2.014–10.453 | <0.001 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||||||

| Not done | 53 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Done | 74 | 0.645 | 0.354–1.175 | 0.152 | 0.649 | 0.324–1.303 | 0.224 | |

| CA 125c | ||||||||

| Not elevated | 50 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Elevated | 15 | 4.700 | 1.838–12.017 | 0.001 | 5.074 | 1.675–15.372 | 0.004 | |

O.R. Odds ratio, C.I. confidence interval, FIGO International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ESS emdometrial stromal sarcoma, MMMT malignant mixed mullerian tumor, LMS leiomyosarcoma, LVSI lymph-vascular space invasion, LN lymph node

aPeritoneal cytologic examination was performed in 68 patients

bLN dissection was performed in 65 patients

cPreoperative CA 125 level was available in 65 patients

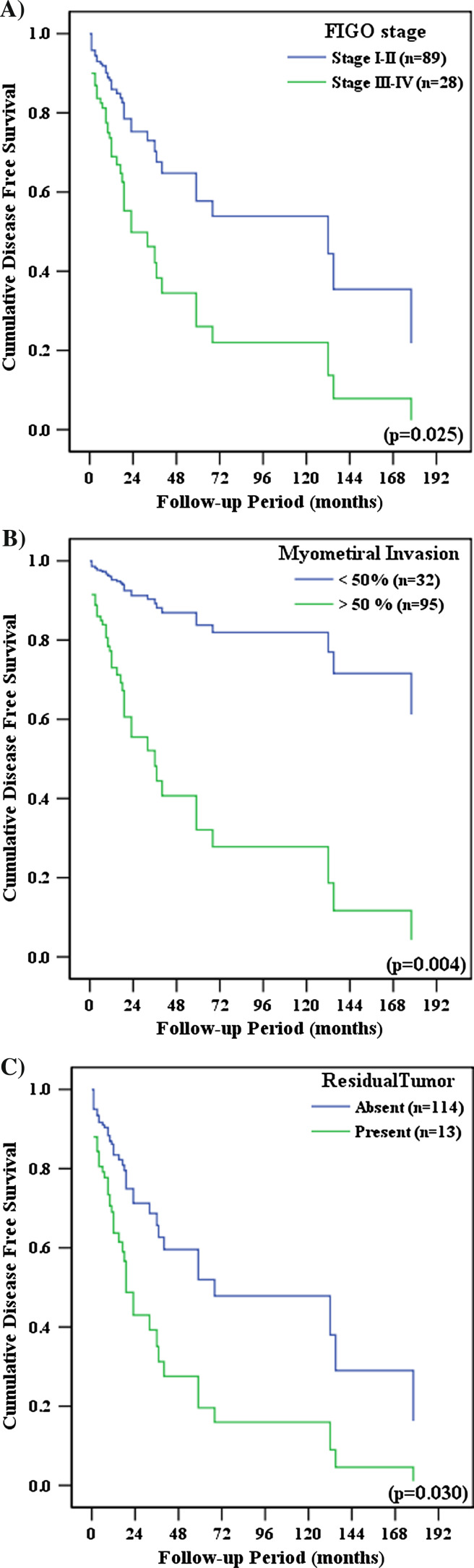

Prognostic factors that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis (Table 5). LN involvement, cytology, and CA 125 levels are surrogates for advanced FIGO stage and thus were excluded from the multivariate analysis to avoid duplication. Advanced FIGO stage, deep myometrial invasion, and the presence of residual tumor cells after surgery were significantly associated with poor DFS (Fig. 3). Menopausal status, advanced FIGO stage, deep myometrial invasion, and positive LVSI were significantly associated with poor OS (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Prognostic factors for uterine sarcoma (multivariate analysis, N = 127)

| Variables | N | Disease free survival | Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P-value | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P-value | |||

| Menopause | ||||||||

| No | 66 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 61 | 1.888 | 0.933–3.821 | 0.077 | 2.442 | 1.025–5.816 | 0.044 | |

| FIGO stage | ||||||||

| I–II | 89 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| III–IV | 28 | 2.450 | 1.120–5.363 | 0.025 | 3.057 | 1.233–7.579 | 0.016 | |

| Histologic type | ||||||||

| ESS | 37 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| MMMT | 44 | 1.595 | 0.550–4.623 | 0.390 | 1.835 | 0.469–7.184 | 0.383 | |

| LMS | 46 | 2.291 | 0.903–5.816 | 0.081 | 2.681 | 0.768–9.352 | 0.122 | |

| Grade | ||||||||

| I | 49 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| II–III | 78 | 1.608 | 0.697–3.810 | 0.281 | 2.295 | 0.785–6.705 | 0.129 | |

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| <10 cm | 105 | 1 | ||||||

| >10 cm | 22 | 1.684 | 0.736–3.851 | 0.217 | ||||

| Mm invasion | ||||||||

| <50% | 32 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| >50% | 95 | 6.419 | 1.792–22.992 | 0.004 | 5.898 | 1.200-28-978 | 0.029 | |

| LVSI | ||||||||

| Negative | 95 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 32 | 1.483 | 0.699–3.144 | 0.304 | 2.897 | 1.178–7.121 | 0.020 | |

| Residual tumor | ||||||||

| No | 114 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 13 | 2.489 | 1.092–5.672 | 0.030 | 1.757 | 0.642–4.811 | 0.273 | |

O.R. Odds ratio, C.I. confidence interval, FIGO International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ESS emdometrial stromal sarcoma, MMMT malignant mixed mullerian tumor, LMS leiomyosarcoma, LVSI lymph-vascular space invasion

Fig. 3.

Disease-free survival by a FIGO stage, b depth of myometrial invasion and c presence of residual tumor cells after surgery. The multivariate analysis was adjusted for menopausal status, FIGO stage, histological type, tumor grade, depth of myometrial invasion, lymph-vascular space invasion, and presence of residual tumor cells (Cox proportional hazards model)

Fig. 4.

Overall survival by a menopausal status, b FIGO stage, c depth of myometrial invasion and d invasion of lymph-vascular space. The multivariate analysis was adjusted for menopausal status, FIGO stage, histological type, tumor grade, tumor size, depth of myometrial invasion, invasion of lymph-vascular space, and presence of residual tumor cells (Cox proportional hazards model)

Discussion

Our results revealed that the overall DFS rate for patients with uterine sarcoma was 30%, with a median follow-up time of 38 months. This is consistent with previous the reports of DFS rates, ranging from 34 to 36% (Chauveinc et al. 1999; El Husseiny et al. 2002). The overall OS rate for patients in our study was 48%, which coincides with previous reports in the range of 45–47% (Nordal and Thoresen 1997; Chauveinc et al. 1999; Denschlag et al. 2007). However, some studies reported lower OS rates, ranging from 21 to 31% (Olah et al. 1991; Kelly and Craighead 2005), and other studies reported a higher OS rate of 64.5% (Gonzalez-Bosquet et al. 1997).

Extrafascial hysterectomy (EH) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) are the standard treatments for uterine sarcomas (Gadducci et al. 2008). Recent reports insist that patients who underwent extended or radical hysterectomy had more favorable outcomes than those who underwent EH (Kokawa et al. 2006). The role of BSO in uterine sarcoma is controversial. Some studies have found that adnexectomy is associated with an improved prognosis in patients with LMS and a decreased recurrence in patients with ESS (Gadducci et al. 1996; Morice et al. 2003). However, others have reported contradictory results (Giuntoli et al. 2003; Li et al. 2005). In our study, 47 patients who did not undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy did not have significantly different DFS and OS times than patients who underwent this procedure.

Our results show that complete surgical resection is important for favorable treatment outcomes. This finding is consistent with the previous reports in the literature (Sagae et al. 2004; Benoit et al. 2005). Complete surgical resection may be the best option because effective adjuvant treatments for uterine sarcoma remain elusive. Therefore, gynecologic oncologists should strive for complete surgical resection of tumors, in addition to performing EH and BSO.

This study reveals that adjuvant therapy has little impact on the management of uterine sarcoma, especially in early-stage disease. The method of adjuvant therapy also had a limited effect on prognosis. However, our univariate analysis revealed that patients with advanced-stage disease who received adjuvant chemotherapy had significantly longer OS times when compared with patients who either did not receive adjuvant therapy or received other types of adjuvant therapy. A preliminary report from the only published prospective randomized controlled trial on adjuvant radiation therapy suggests that adjuvant radiation therapy improves the local control rate for MMMT, but does not improve the DFS or OS of any other type of uterine sarcoma (Reed et al. 2003). Moreover, retrospective studies provide limited evidence that adjuvant radiation therapy improves the survival of patients with uterine sarcoma (Olah et al. 1991; Gadducci et al. 1996; Giuntoli et al. 2003; Dusenbery et al. 2005), although some positive results have been reported (Brooks et al. 2004; Livi et al. 2004). The high rate of distant failure, even among patients with early-stage uterine sarcoma, makes adjuvant chemotherapy more appealing than radiation therapy. As with adjuvant radiotherapy, however, there is little evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy improves the survival of patients with early-stage uterine sarcoma (Omura et al. 1985; Hempling et al. 1995; Gadducci and Romanini 2001), with a few exceptions in the literature (Odunsi et al. 2004; Sutton et al. 2005). Several randomized controlled trials and prospective non-randomized trials have evaluated the role of chemotherapy in advanced-stage disease. Although there is limited evidence in the literature to suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy improves the survival of patients with advanced-stage uterine sarcoma (Muss et al. 1985; Omura et al. 1985; Sutton et al. 2000), some studies, including our own, have reported that adjuvant chemotherapy has a positive effect (Kokawa et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2006).

It is also unclear whether prognosis is influenced by the histological type of uterine sarcoma. Several studies have reported that histological type is an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analyses (Major et al. 1993; Sagae et al. 2004; Denschlag et al. 2007). In these previous studies, the outcome of ESS was significantly better than the outcomes of LMS and MMMT, primarily because ESS tends to present as a low-grade, early-stage disease with low levels of metastases. However, other multivariate analyses, including ours, have found that the histological subtype does not impact survival (George et al. 1986; Wolfson et al. 1994; Kokawa et al. 2006). Furthermore, high-grade ESS has a poor prognosis, similar to that in patients with other high-grade uterine sarcomas (Gadducci et al. 1996).

Our study suggests that age has no significant impact on survival. The literature contains conflicting data regarding the significance of age in the survival of patients with sarcoma. Some studies, including our own, have found no relationship between age and survival (Peters et al. 1984; El Husseiny et al. 2002). However, others have reported that patients younger than age 50 years have significantly longer DFS and OS times (Olah et al. 1991; Kokawa et al. 2006). However, our multivariate analyses revealed that postmenopausal women have significantly poorer OS times, consistent with previously reported data (Coquard et al. 1997; Chauveinc et al. 1999; El Husseiny et al. 2002).

As there is no official staging system for uterine sarcomas, the FIGO system for corpus carcinoma is generally used. We relied on the FIGO system to stage tumors, using pathological data obtained by surgery. Many reports, including our own, have found that the FIGO stage is one of the most important prognostic factors. Consistent with previous studies, we found that positive peritoneal cytology and lymph node metastasis are also significant prognostic factors (Major et al. 1993; El Husseiny et al. 2002), although these may be surrogates for advanced-stage disease. Elevated CA 125 levels, another significant prognostic factor, may also be a surrogate for advanced disease that has spread to the peritoneum. As information about peritoneal cytology, LN status and preoperative CA 125 levels were only available for some patients in our series, limiting our ability to draw conclusions from this data. However, our results suggest that CA 125 levels may be especially useful as a preoperative prognostic factor.

Previous studies have found that tumor size is a significant prognostic factor for uterine sarcoma (George et al. 1986; Rovirosa et al. 2002). However, our multivariate analysis did not find that tumor size is a significant factor in the patient’s prognosis. Our results suggested that depths of myometrial invasion exceeding 50% are significant prognostic factors, similar to previous findings (Rovirosa et al. 2002; Sagae et al. 2004). Interestingly, we found that LVSI is a significant prognostic factor like carcinoma of the uterine cervix, and corpus. LVSI generally indicates an aggressive neoplasm with a marked tendency to metastasize and recur locally. The impact of LVSI on uterine sarcoma has been described in previous studies (Major et al. 1993; Rovirosa et al. 2002).

In conclusion, complete surgical resection is important for the successful treatment of uterine sarcoma. Adjuvant therapy appears to play a limited role in patients with early-stage disease. However, patients with advanced-stage disease who receive adjuvant chemotherapy appear to survive significantly longer than other patients. Our multivariate analysis indicates that postmenopausal status, advanced FIGO stage, deep myometrial invasion, and positive LVSI are associated with poor prognosis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors hereby confirm that all authors fulfill the requirements for authorship and that no potential conflicts of interest are declared.

References

- Benoit L, Arnould L, Cheynel N, Goui S, Collin F, Fraisse J et al (2005) The role of surgery and treatment trends in uterine sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 31:434–442. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR (2004) Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989–1999. Gynecol Oncol 93:204–208. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauveinc L, Deniaud E, Plancher C, Sastre X, Amsani F, de la Rochefordiere A et al (1999) Uterine sarcomas: the Curie Institut experience. Prognosis factors and adjuvant treatments. Gynecol Oncol 72:232–237. doi:10.1006/gyno.1998.5251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquard R, Romestaing P, Ardiet JM, Mornex F, Sentenac I, Gerard JP (1997) Uterine sarcoma treated by surgery and postoperative radiation therapy. Patterns of relapse, prognostic factors and role of radiation therapy. Bull Cancer 84:625–629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables. R Stat Soc B 34:187–220 [Google Scholar]

- Denschlag D, Masoud I, Stanimir G, Gilbert L (2007) Prognostic factors and outcome in women with uterine sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 33:91–95. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbery KE, Potish RA, Argenta PA, Judson PL (2005) On the apparent failure of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy to improve survival for women with uterine sarcomas confined to the uterus. Am J Clin Oncol 28:295–300. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000156919.04133.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Husseiny G, Al Bareedy N, Mourad WA, Mohamed G, Shoukri M, Subhi J et al (2002) Prognostic factors and treatment modalities in uterine sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol 25:256–260. doi:10.1097/00000421-200206000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadducci A, Romanini A (2001) Adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage uterine sarcomas: an open question. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 22:352–357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadducci A, Sartori E, Landoni F, Zola P, Maggino T, Urgesi A et al (1996) Endometrial stromal sarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol 63:247–253. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadducci A, Cosio S, Romanini A, Genazzani AR (2008) The management of patients with uterine sarcoma: A debated clinical challenge. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 65:129–142. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George M, Pejovic MH, Kramar A (1986) Uterine sarcomas: prognostic factors and treatment modalities—study on 209 patients. Gynecol Oncol 24:58–67. doi:10.1016/0090-8258(86)90008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuntoli RL 2nd, Metzinger DS, DiMarco CS, Cha SS, Sloan JA, Keeney GL et al (2003) Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol 89:460–469. doi:10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00137-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Bosquet E, Martinez-Palones JM, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Garcia Jimenez A, Xercavins J (1997) Uterine sarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 93 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 18:192–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempling RE, Piver MS, Baker TR (1995) Impact on progression-free survival of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (adriamycin), and dacarbazine (CYVADIC) chemotherapy for stage I uterine sarcoma. A prospective trial. Am J Clin Oncol 18:282–286. doi:10.1097/00000421-199508000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric extimator from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481. doi:10.2307/2281868 [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KL, Craighead PS (2005) Characteristics and management of uterine sarcoma patients treated at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15:132–139. doi:10.1111/j.1048-891x.2005.15014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokawa K, Nishiyama K, Ikeuchi M, Ihara Y, Akamatsu N, Enomoto T et al (2006) Clinical outcomes of uterine sarcomas: results from 14 years worth of experience in the Kinki district in Japan (1990–2003). Int J Gynecol Cancer 16:1358–1363. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AJ, Giuntoli RL 2nd, Drake R, Byun SY, Rojas F, Barbuto D et al (2005) Ovarian preservation in stage I low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas. Obstet Gynecol 106:1304–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livi L, Andreopoulou E, Shah N, Paiar F, Blake P, Judson I et al (2004) Treatment of uterine sarcoma at the Royal Marsden Hospital from 1974 to 1998. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 16:261–268. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major FJ, Blessing JA, Silverberg SG, Morrow CP, Creasman WT, Currie JL et al (1993) Prognostic factors in early-stage uterine sarcoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 71:1702–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N (1966) Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep 50:163–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice P, Rodrigues A, Pautier P, Rey A, Camatte S, Atallah D et al (2003) Surgery for uterine sarcoma: review of the literature and recommendations for the standard surgical procedure. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 31:147–150. doi:10.1016/S1297-9589(03)00061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muss HB, Bundy B, DiSaia PJ, Homesley HD, Fowler WC Jr, Creasman W et al (1985) Treatment of recurrent or advanced uterine sarcoma. A randomized trial of doxorubicin versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (a phase III trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group). Cancer 55:1648–1653. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19850415)55:8<1648::AID-CNCR2820550806>3.0.CO;2-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordal RR, Thoresen SO (1997) Uterine sarcomas in Norway 1956–1992: incidence, survival and mortality. Eur J Cancer 33:907–911. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00040-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odunsi K, Moneke V, Tammela J, Ghamande S, Seago P, Driscoll D et al (2004) Efficacy of adjuvant CYVADIC chemotherapy in early-stage uterine sarcomas: results of long-term follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14:659–664. doi:10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah KS, Gee H, Blunt S, Dunn JA, Kelly K, Chan KK (1991) Retrospective analysis of 318 cases of uterine sarcoma. Eur J Cancer 27:1095–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura GA, Blessing JA, Major F, Lifshitz S, Ehrlich CE, Mangan C et al (1985) A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant adriamycin in uterine sarcomas: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 3:1240–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters WA 3rd, Kumar NB, Fleming WP, Morley GW (1984) Prognostic features of sarcomas and mixed tumors of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 63:550–556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed N, Mangioni C, Malmstrom H, Scarfone G, Poveda A, Tateo S et al (2003) First results of a randomised trial comparing radiotherapy versus observation postoperatively in patients with uterine sarcomas. An EORTC-GCG study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 13:4 [Google Scholar]

- Rovirosa A, Ascaso C, Ordi J, Abellana R, Arenas M, Lejarcegui JA et al (2002) Is vascular and lymphatic space invasion a main prognostic factor in uterine neoplasms with a sarcomatous component? A retrospective study of prognostic factors of 60 patients stratified by stages. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 52:1320–1329. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02808-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagae S, Yamashita K, Ishioka S, Nishioka Y, Terasawa K, Mori M et al (2004) Preoperative diagnosis and treatment results in 106 patients with uterine sarcoma in Hokkaido, Japan. Oncology 67:33–39. doi:10.1159/000080283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumsky AG, Stuart GC, Brasher PM, Nation JG, Robertson DI, Sangkarat S (1994) An evaluation of routine follow-up of patients treated for endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 55:229–233. doi:10.1006/gyno.1994.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton G, Brunetto VL, Kilgore L, Soper JT, McGehee R, Olt G et al (2000) A phase III trial of ifosfamide with or without cisplatin in carcinosarcoma of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 79:147–153. doi:10.1006/gyno.2000.6001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton G, Kauderer J, Carson LF, Lentz SS, Whitney CW, Gallion H (2005) Adjuvant ifosfamide and cisplatin in patients with completely resected stage I or II carcinosarcomas (mixed mesodermal tumors) of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 96:630–634. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson AH, Wolfson DJ, Sittler SY, Breton L, Markoe AM, Schwade JG et al (1994) A multivariate analysis of clinicopathologic factors for predicting outcome in uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol 52:56–62. doi:10.1006/gyno.1994.1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TI, Chang TC, Hsueh S, Hsu KH, Chou HH, Huang HJ et al (2006) Prognostic factors and impact of adjuvant chemotherapy for uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol 100:166–172. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]