Abstract

Background

The Levitation™ “Tri-Compartment Offloader” (TCO) knee brace (Spring Loaded Technology) is designed to reduce pain for individuals with knee osteoarthritis (OA). The TCO is available on the market, however, has not been compared to the current standard of care treatment for knee OA with a controlled clinical trial. This feasibility study aimed to (i) evaluate the feasibility of conducting a full RCT, (ii) evaluate the distributional properties of the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) activity-specific knee pain score to estimate the sample size required for a full randomised controlled trial (RCT), and (iii) refine and optimise the study protocol.

Methods

A prospective, 3-group, parallel, single-centre feasibility RCT of individuals with moderate to severe patellofemoral or multicompartment knee OA was undertaken at the University of Calgary (Alberta, Canada). Participants were randomised using a 1:1:1 random allocation to one of three intervention groups: standard of care (Control), Control plus a knee sleeve (Sleeve), or Control plus a TCO brace (TCO). Participants were assessed at baseline (before intervention) and after 6 weeks and 3 months (primary endpoint) of controlled intervention. The sample size for a full RCT was estimated based on the change in VAS knee pain between baseline and 3 months. Feasibility was assessed using participant recruitment, intervention adherence, participant response rates, data quality, dropout rate and adverse events. All protocol changes made throughout the duration of the study were recorded.

Results

Twenty-nine participants (13 females; age: 62 ± 9 years) were recruited. The estimated sample size for a full RCT is 93 individuals (31 per group). Participants showed high intervention adherence and follow-up rates were 86% at 3 months. Four participants dropped out of the study, and there were 3 adverse events reported. Changes were made to participant eligibility criteria, recruitment strategy and data collection methods to improve feasibility, efficiency, and appropriateness for a full RCT.

Conclusions

This study supports the feasibility of a full scale RCT evaluating the clinical effectiveness of the TCO knee brace compared to the current (conservative) standard of care treatment for individuals with knee OA, and an adequately powered RCT is now warranted.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, ID: NCT05543486. Registered 15 September 2022—retrospectively registered, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05543486

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40814-025-01660-2.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Bracing, Tri-compartment offloader, Knee pain

Key messages regarding feasibility

• Uncertainties existed regarding trial feasibility including patient recruitment, intervention adherence, response rates, data quality, dropout rate, and adverse events

• Participant recruitment was a challenge, which was amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic

• Several recommendations are provided for the main study to improve participant recruitment and to improve participant experience and therefore reduce dropout rate for the main study.

Introduction

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a debilitating musculoskeletal disease affecting approximately 1/3 of Canadians over the age of 25 [1]. The disease is characterised by loss of cartilage in the afflicted joint and can be a major source of pain, disability, and reduced quality of life. The direct cost of OA in Canada was $2.9 billion CAD in 2010 and is expected to rise to $7.6 billion CAD by 2031 [2]. The knee is the most common site for OA [3], and can affect one or both tibiofemoral compartments as well as the patellofemoral compartment. Bi- and tri-compartmental OA constitute 50% of knee OA cases, while the rates of unicompartment tibiofemoral OA account for just 32% of cases [4]. Knee OA is a degenerative disease with up to 68% of patients showing disease progression over a 2-year period, measured by radiographic changes in cartilage defects [5]. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is used to restore mobility and minimise pain in severe cases, contributing to high average costs of OA in Canada ($12,200 CAD annually per affected individual) [6]. Individuals under 65 years of age are at increased risk of expensive and invasive revision surgery at initial TKA, 2–5 times more so than their older counterparts [7]. Revision surgery is also associated with significant pre- and post-operative complications. Thus, finding an alternate early treatment intervention to manage symptoms and promote joint health is imperative for societal and economic health.

Conservative treatment options for knee OA focus on education and self-management to minimise symptoms and improve quality of life. This includes analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications, intra-articular injections, strength training, weight loss, and biomechanical interventions such as knee braces [8, 9]. Knee braces are often prescribed to reduce pain, improve function and enable individuals with OA to participate in physical activity [10]. This is important since physical activity is a key recommended therapy for knee OA, irrespective of age, disease severity and pain [11]. It is well established that excess joint loading is associated with symptoms of knee pain in the OA population [12]. The majority of knee OA braces attempt to restore function and reduce pain in individuals with unicompartmental tibiofemoral OA through a process known as lateral or medial offloading [13]. These braces have been shown to improve symptoms in individuals with unicompartmental tibiofemoral OA [14, 15]. However, they are not designed to offload the joint during deep knee flexion, when joint contact forces and knee pain are highest [16, 17]. Additionally, the effectiveness of these braces for long-lasting biomechanical change remains unclear [10]. Consequently, these “unicompartmental offloader” braces are not designed for the majority of individuals with knee OA who have either isolated patellofemoral, bi-, or tri-compartmental disease [4].

The Levitation™ “Tri-Compartment Offloader” (TCO) knee brace developed by Spring Loaded Technology (Nova Scotia, Canada) is designed to reduce pain for individuals with multicompartment knee OA affecting the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compartments of the knee. The brace uses spring technology to store energy during knee flexion and assist movement during knee extension [18]. The TCO is designed to reduce compressive joint contact forces related to knee pain in all three knee compartments by lowering quadriceps muscle effort [18–21]. Bishop et al. demonstrated that the TCO reduces both the net knee flexion moment and quadriceps muscle activity during a chair rise and lower in individuals with multicompartment knee OA [22]. A follow-up study showed reduced knee joint contact forces in both the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compartments of the knee [23]. The magnitude of joint unloading achieved with TCO use was similar to that achieved by clinically recommended levels of bodyweight loss [24], and is therefore expected to result in clinical benefits for individuals with knee OA [23]. These findings support the proposed mechanism of offloading via reducing compressive quadriceps muscle forces and demonstrate that the TCO brace can provide offloading benefits to multiple compartments in the knee.

In a systematic survey [25], 95% of TCO brace users with symptomatic knee OA experienced reduced knee pain to a level below the patient acceptable symptom state [26]. Additionally, 70% of participants increased their weekly physical activity level, 60% reported a decrease in their use of other treatments, and 50% of users considering surgery before using the TCO brace were able to delay or eliminate the need for surgery following TCO brace use [25]. These findings provide evidence demonstrating that the TCO brace can improve outcomes for individuals with unicompartmental and multicompartmental knee OA, and suggests a positive impact of tricompartment offloading for these patient groups. However, the generalisability of these benefits to a larger group requires investigation through a controlled clinical study involving individuals with patellofemoral and multicompartment knee OA. A patient oriented research (POR) approach is used in this research, whereby patients are involved as partners and active contributors in all phases of the project [27]. The documented benefits of patient engagement in research include improved feasibility, acceptability, rigor and relevance [28]. Therefore, this approach aims to improve the feasibility and effectiveness of the clinical study design while ensuring the outcomes have wide clinical and community impact.

There are several metrics upon which knee braces are assessed for the OA population including pain, function, quality of life, stiffness and need for TKA [29]. Previous knee OA bracing studies have shown improvements in knee pain and function as early as 6 weeks post-intervention, with further improvements at 3 months [30]. Clinical studies evaluating the use of a unicompartmental offloader knee brace with swing-assist (OA RehabilitatorTM, Guardian Brace) over 3 months of use in individuals with knee OA have shown improvements in knee pain, muscle strength and knee function [15, 31]. Spring Loaded Technology's Levitation TCO knee brace is currently available on the market, however, has not been compared to the current standard of care treatment for knee OA using these clinical metrics. It is hypothesised that by providing a tri-compartment offloading effect, the TCO may improve knee pain and other clinical outcomes for individuals with patellofemoral or multicompartmental knee OA. To investigate this hypothesis, a high-quality randomised control trial (RCT) is needed. Knee pain, the primary outcome variable, can be assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is a reliable measure of osteoarthritic knee pain [32]. Other outcomes of interest include knee function, quality of life, performance-based tests and lower limb muscle strength. Importantly, the TCO brace provides both a mechanical offloading effect as well as a proprioceptive effect. Soft-shell neoprene knee braces (or “sleeves”) have also been shown to reduce pain in individuals with knee OA, believed to be a result of improved proprioception [30]. Therefore, to better isolate and understand the mechanical effect of the TCO’s extension assist mechanism on patient outcomes, an intervention group with a proprioception intervention only, such as a neoprene sleeve, is required to remove the potentially confounding effect of proprioception on measured outcomes.

As an initial step, a feasibility study is required to support the development of a future definitive RCT. The feasibility study is not designed or powered to draw conclusions on the clinical effectiveness of the TCO brace for individuals with knee OA. Rather, feasibility study data will inform the study design, ensuring adequate power and optimised methods, and can be used to assess the feasibility of conducting the full trial. There are several factors that may influence the feasibility of delivering an RCT to evaluate the clinical effect of using the TCO brace to manage knee OA symptoms. These include rate of recruitment, which impacts study timeline, acceptability of the study protocol, and data quality as well as protocol adherence, which both impact the ability to draw strong conclusions from the data. It is also necessary to proactively identify any barriers that would impede the successful delivery of a definitive RCT.

Objectives

The aim of this feasibility study was to establish whether it is feasible to deliver a full RCT comparing clinical outcomes of using the TCO knee brace to the current (conservative) standard of care treatment for individuals with knee OA and to refine trial procedures ahead of a full RCT. This was done using a POR approach where patient partners assisted with study design, implementation and interpretation (described in a separate upcoming publication). This unique approach allowed the research team to use direct patient experience to inform recruitment strategies and data capture mechanisms thus enabling a patient centric approach to research.

The primary objective (OB) of this study was to.

OB1: Evaluate trial feasibility in terms of participant recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome data, dropout rate, and adverse events.

The secondary objectives were to.

OB2: Estimate the sample size required for a full RCT by evaluating the distributional properties of the VAS activity-specific knee pain score.

OB3. Refine and optimise the study protocol to improve feasibility, efficiency and appropriateness for a full RCT.

This study underwent full peer and ethics review prior to commencement (University of Calgary REB 20–1106).

Methods

Trial design

This is a prospective, 3-group, parallel, single-centre feasibility RCT of individuals with moderate to severe patellofemoral or multicompartment knee OA. A total of 29 participants were randomised using a 1:1:1 random allocation. Participants were assessed at baseline (before intervention) and after 6 weeks and 3 months (primary endpoint) of controlled intervention.

Participants

Participants included adults aged 18–80 years with moderate to severe multicompartment or patellofemoral knee OA (Table 1). Diagnosis of OA severity and identification of affected compartments was performed on radiographs by a single orthopaedic surgeon (MC) using the Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic grading system [33].

Table 1.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

• Patellofemoral or combined patellofemoral and tibiofemoral knee OA • Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2 knee OA on weight bearing tunnel view and skyline X-ray • Knee pain that worsens with walking on inclined terrain, going up and down stairs, squatting or rising from a seated position • Minimum VAS pain score of 4/10 during weight-bearing knee flexion (squat, stairs, rising from sitting) • Lower VAS pain score in the contralateral knee compared to the affected knee during weight-bearing activities • < 7° of varus/valgus knee alignment • Minimum knee flexion/extension range of motion of 5–100° • Aged 18–80 years • Able to hear and understand study information and instructions in English • Able to be fit with a Levitation TCO knee brace |

• History of arthroplasty or high tibial osteotomy in the affected limb • Surgery (excluding arthroscopy) on either lower limb within last 6 months • Arthroscopic debridement of the affected knee within last 3 months • Received corticosteroid injections in the affected knee in the last 3 months • Received hyaluronic acid or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections in the affected knee in last 6 months • History of rheumatoid arthritis • Symptomatic disease of the hip, ankle, or foot • History of traumatic onset of knee pain • A major lower limb injury within the past year requiring physiotherapy or surgery • Previous fracture of the tibia or femur of the affected limb • History of diabetic neuropathy or peripheral vascular disease • Parkinson’s or neurodegenerative order that may affect balance or ability to ambulate • Use of a non-study provided knee brace on the affected limb during the study period • Known allergy or adverse skin reaction to neoprene • Open skin wounds present on the affected limb • Unable to physically or mentally comply with the wearing of a knee brace • Any contraindications for knee bracing |

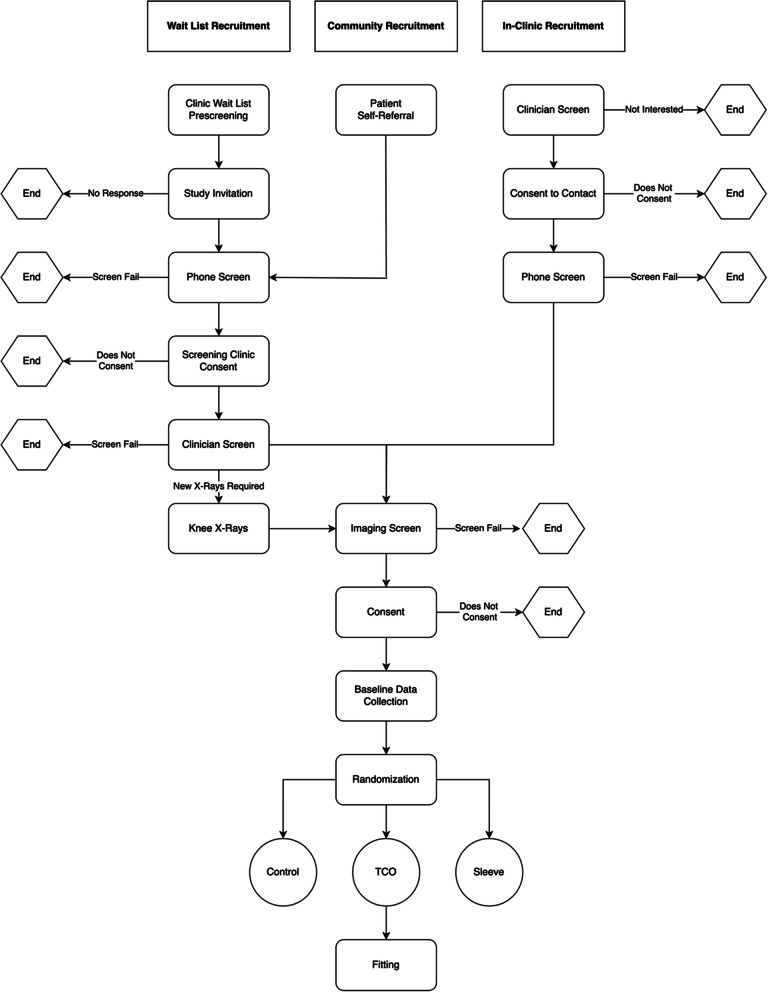

A diverse recruitment strategy (Fig. 1) was employed to capture individuals currently undergoing treatment for knee OA (In-Clinic Recruitment), those awaiting treatment (Waitlist Recruitment), and those from the broader community (Community Recruitment).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the steps of the 3 recruitment pathways employed to recruit participants for the feasibility study

In-Clinic Recruitment targeted patients from 8 clinics in Calgary, Alberta who see knee OA patients (Table 2). Study advertisement posters were displayed in the exam rooms of participating clinics, and clinicians identified and screened patients against inclusion/exclusion criteria in the clinic.

Table 2.

In-clinic recruitment site details

| Clinic | Location |

|---|---|

| Bone and Joint Clinic | South Health Campus, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, Alberta |

| Department of Surgery | Foothills Medical Centre, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, Alberta |

| Alberta Hip and Knee Clinic | Gulf Canada Square, Calgary, Alberta |

| University of Calgary Sports Medicine Centre | University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta |

| Southland Sport Medicine Clinic | Southland Leisure Centre, Calgary, Alberta |

| The Knee Clinic | Southland Park, Calgary, Alberta |

| 4 th Street Medical Clinic | Mission Centre, Calgary, Alberta |

| Canadian Medical Solutions | South Trail Crossing, Calgary, Alberta |

Waitlist Recruitment targeted patients awaiting treatment for knee OA. An orthopaedic surgeon (MC) identified potential participants from their orthopaedic consultation waitlist at a tertiary hospital. Community Recruitment targeted individuals from the broader community. Recruitment posters, online advertisements (University of Calgary Participate in Research webpage, University of Calgary G:LAD Program), and word of mouth were used to target individuals from the Calgary area not captured by other recruitment efforts. Individuals from both community and waitlist recruitment who contacted the study coordinator were invited to attend a screening clinic to determine their eligibility to participate. The in-person screening clinics were conducted by an orthopaedic surgeon (MC) in the Clinical Movement Assessment Laboratory (University of Calgary). Participants signed a separate informed consent form prior to participating in the screening clinic.

Participants were withdrawn from the study if they fell into any of the following categories: violation of entry criteria; serious concurrent illness; adverse reaction preventing treatment; or at the participant’s request. Participant dropout and reason for dropout were recorded.

Interventions

Eligible participants were randomly assigned (as detailed below in “Randomisation”) to one of three treatment groups: self-management (Control), self-management plus soft shell knee sleeve (Sleeve), or self-management plus Levitation TCO brace (TCO) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptions of 3 study intervention groups

| Control | Sleeve | TCO |

|---|---|---|

| Standard conservative management of patients with knee OA in Alberta, Canada |

Same medical treatment as control group PLUS fitted with a soft-shell knee sleeve (NEENCA, USA) |

Same medical treatment as the control group PLUS fitted with a TCO knee brace (Levitation 2, Spring Loaded Technology) |

|

• Received a standard set of educational materials on knee OA (Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute [34]) which included strategies for self-management and community resources • No formal physiotherapy for the 3-month controlled intervention period • No knee injection therapies (e.g. corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid and PRP) in the affected limb for the 3-month controlled intervention period • Did not wear a knee brace on the affected limb during the 3-month intervention period |

• Knee sleeve comprised a compression style stocking with a padded insert for the patella along with lateral and medial flexible stays • Knee sleeve size determined by the study coordinator based on a measurement of thigh circumference, 5 inches above the centre of the patella • Participants instructed on the appropriate use of the knee sleeve and instructed to wear the sleeve while awake during weight bearing activities for a minimum of 3 h/day for the 3-month controlled intervention period |

• Brace size determined by Spring Loaded Technology based on a set of lower limb leg measurements taken by the study coordinator • Knee brace fitted by a certified orthotist (Colman Prosthetics & Orthotics, Calgary AB) • Participants instructed on the appropriate use of their brace and instructed to wear their brace while awake during weight bearing activities for a minimum of 3 h/day for the 3-month controlled intervention period |

Assessments

Participants were assessed at baseline, 6 weeks post-intervention and 3 months post-intervention (Table 4). The assessment consisted of two parts: (1) an online survey-based assessment completed by participants at their convenience, and (2) an in-person strength and functional assessment. All assessments were developed in consultation with patient partners to ensure that outcomes important to patients were captured, and that the assessments were reasonable for participants to complete.

Table 4.

Participant assessments performed at each study timepoint

| Assessment | Baseline | 6 weeks | 3 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey-based assessment | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Strength and functional assessment | ✔ | ✔ |

The survey was administered using Qualtrics XM data capture platform. Self-administered outcome tools were selected based on the reliability and validity of the tool, use in previous knee OA bracing trials and relevance to knee OA. Validated questionnaires included: VAS for knee pain [32], Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) for knee function [35], EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D) for quality of life [36], Lower Extremity Activity Scale (LEAS) for activity level [37], and Orthotics Prosthetics User Survey–Satisfaction with Devices (OPUS-CSD) for satisfaction with the knee brace [38]. Custom questions were developed to capture demographic data and additional information relevant to the desired study outcomes. The survey took approximately 20–25 min to complete (complete survey included in Supplementary materials).

Strength and functional assessments were performed at the Clinical Movement Assessment Lab (McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health, University of Calgary). The protocol consisted of maximal voluntary muscle strength testing of the hamstring and quadricep muscles measured by isokinetic dynamometry (Biodex Medical Systems Inc.). Participants performed the following exercises on the dynamometer following a standardised warm-up procedure: (a) knee extension at 45° of knee flexion (quadriceps), and (b) knee flexion at 15° of knee flexion (hamstrings) [39, 40]. Participants performed 3 repetitions for each muscle group, and tests were performed bilaterally starting with the unaffected leg. Participants were instructed to hold each muscle contraction for 3 s while being provided with verbal encouragement, with 60 s of rest provided between each exercise. Next, participants performed the following standardised OARSI recommended performance based tests [41] without any aids: (a) 30-s chair stand test, (b) 40 m fast-paced walking test, (c) stair-climb test, (d) timed up and go test, and (e) 6-min walk test. The strength and functional assessment took approximately 60–90 min to complete.

The following outcome measures for the full RCT were captured to enable an evaluation of key outcomes related to interventions for knee OA.

Primary outcome measure (full RCT)

1) Knee pain (VAS) while squatting.

Secondary outcome measures (full RCT)

2) Knee pain (VAS) while walking on a flat surface.

3) Knee pain (VAS) while rising from sitting.

4) Knee pain (VAS) while going up or down the stairs.

5) KOOS Function Daily Living Score.

6) KOOS Symptom Score.

7) KOOS Pain Score.

8) KOOS Function Sport and Recreation Score.

9) KOOS Knee Related QOL Score.

10) EQ-5D Health-related quality of life score.

11) Performance based test scores.

12) Maximal voluntary muscle strength of the hamstrings and quadriceps.

Exploratory outcome measures (full RCT)

Physical activity level (LEAS)

Associated pain in other regions (custom)

Brace expectations (adapted from the Knee Scoring System, KSS [42])

Satisfaction with Devices (OPUS-CSD)

Brace use (custom)

Medication use (custom)

Use of healthcare practitioner services (custom)

Perceived need for joint replacement surgery (custom)

Self-rated protocol adherence (custom)

VAS knee pain data is presented in this manuscript to address Objective 2. The remaining secondary and exploratory outcome measures are not presented, however, they are used to inform Objectives 1 and 3.

Sample size

A formal power analysis for the sample size was not undertaken, as this feasibility study was not designed to test a specific null hypothesis or infer significance to any observed treatment differences. Instead, we chose a sample size for this feasibility study equal to 25% of the estimated number of participants required for a full RCT. The preliminary sample size calculation for the full RCT suggests we need to recruit 120 participants. Therefore, we aimed to recruit 30 participants based on the aims of (i) assessing feasibility and (ii) informing the sample size calculation and design of the full RCT. This aligns with the “rule of thumb” proposed by Kieser and Wassmer [52], who recommended sample sizes of between 20 and 40 participants for two-group studies (10–20 per arm) when the number of participants required for a full RCT is estimated to be 80–250. This sample size is also consistent with previously published pilot and feasibility studies of knee braces in this patient population employing similar designs [31]. Finally, we estimated that a sample size goal of 30 (10 per group) for this feasibility trial to be achievable in relation to the anticipated recruitment rate and available resources at the time of protocol design. Based on this target sample size, the 95% confidence interval around our assumed retention rate of 80% is 63.3% to 89.8%, indicating a reasonable level of precision in estimating participant retention in the context of a feasibility study.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed by the study coordinator using Study Randomizer (2017), a web-based randomisation service (https://www.studyrandomizer.com) following enrollment and baseline data collection. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups according to a permutated block randomisation scheme with stratification based on age (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years) and sex to encourage equal proportions of age and sex in each group.

Blinding

The TCO brace and knee sleeve (or lack thereof) are clearly visible, thus the participants could not be blinded to their intervention. Only the research coordinator (JB) was aware of participants’ group allocation and there was no interaction between study participants during the study. Study outcome data was identified with a unique 5-digit alphanumeric ID, assigned following enrollment. The file linking the study ID to identifying participant information was stored on a secure data storage drive at the University of Calgary, accessible by only the research coordinator during the study. Baseline strength and functional data collection was completed by the study coordinator prior to randomisation. Study team members (ELB and MJ) performed all follow-up strength and functional testing and were blinded to intervention group allocation throughout the duration of the study. The remaining study personnel were blinded to the intervention until all primary and secondary analyses were completed. Statistical analysis was performed by independent assessors at the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Support Unit.

Analytical methods

Participant demographic information and clinical characteristics were examined with descriptive statistics using frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (standard derivation), median (interquartile range) and range for continuous variables, as appropriate. Comparison of treatment groups at baseline with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics was performed.

The primary study objective, trial feasibility, was assessed based on participant recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome data, dropout rates and adverse events, described below. The primary outcome measure for the full RCT is change in user-reported pain as measured by the change in VAS pain score while squatting between baseline and 3 months (controlled intervention period). Between group comparison tests were not completed as this feasibility study was not designed to infer significance to any differences between intervention groups. Instead, the distribution of the primary outcome measure and participant recruitment and retention rates were examined to inform the design of a full RCT.

Objective 1: feasibility

Feasibility measures and progression criteria were developed to determine feasibility success (Table 5). Descriptive statistics were used to describe study feasibility outcomes, including participant recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome data, dropout rate, and adverse events during the intervention period. Participant recruitment was evaluated by assessing the willingness of clinicians to recruit participants, the number of eligible individuals within the recruiting site, the willingness of individuals to enrol in the study, and the rate of participant recruitment to estimate the timescale for a full RCT. Intervention adherence was assessed by evaluating compliance with intervention protocols for all intervention groups, including duration of brace wear for the TCO and knee sleeve groups. Outcome data was evaluated by assessing participant response rates for both the survey-based assessment and the in-person strength and functional testing, as well as quantifying missing and incomplete data. Participant dropout rates were reported and all adverse events were recorded.

Table 5.

Feasibility measures, progression criteria, and justification

| Feasibility measure | Progression criteria | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Recruitment | ||

| Percentage of individuals eligible | Require 30% of individuals screened to meet eligibility criteria | MC sees approximately 32 new knee OA patients in clinic each month. Therefore, as a very conservative estimate based on in-clinic recruitment from one clinic, requires at least 30% of individuals screened to meet study eligibility criteria to identify 10 eligible participants per month, and 60 eligible participants in 6 months |

| Percentage of individuals who consent to randomisation | Require minimum 50% study uptake | Require at least a 50% study uptake rate to enroll 30 participants in the study in 6 months |

| 2. Intervention adherence | ||

| Device usage for participants in the Sleeve and TCO groups | Require minimum 60% of participants in the Sleeve and TCO intervention groups meet the recommended weekly device wear target of 21 h | The device wear target was a recommendation to participants in the TCO and Sleeve groups and was not closely monitored or strictly enforced throughout the study |

| 3. Outcome data | ||

| Retention in all intervention groups | Require minimum 80% completion rate | The sample size calculation for the full RCT is based on an anticipated 20% drop out rate |

| Outcome data collection–VAS knee pain (primary outcome variable) | Require valid primary outcome data for 80% of those recruited at baseline and the 3-month timepoint (Avery et al., 2017) | The sample size calculation for the full RCT is based on change in VAS knee pain between baseline and 3 months. Therefore, to ensure that the full RCT would be powered to show an effect if one existed, we require that at least 80% of participants have valid data for this outcome measure at baseline and 3 months |

Objective 2: knee pain

Participant reported knee pain (VAS) while squatting was examined with descriptive statistics for the three study intervention groups at baseline, 6 weeks and 3 months, as well as the change between baseline and 3 months.

The required sample size for a full RCT was calculated by G*Power [43] to evaluate between group differences based on the primary outcome variable of within participant change in VAS knee pain during squatting between baseline and 3 months. The calculation used an independent t-test and assumed 80% power at an alpha level of 0.05. The sample size was inflated by 20% to account for potential losses to follow-up.

Objective 3: optimise protocol

All changes made to the protocol throughout the duration of the study were recorded, summarised and accompanied by adequate justification for their implementation.

Results

Participants

Baseline participant characteristics for all three intervention groups are presented in Table 6. Only the TCO group contained individuals with isolated patellofemoral knee OA, while the Sleeve group had a relatively higher proportion of individuals with bicompartment knee OA, and the Control group had a relatively higher proportion of individuals with tri-compartment knee OA. The TCO group also had higher scores in sports and recreation (S&R) and knee related quality of life (QoL) compared to the other two groups, meaning they reported higher function in these areas.

Table 6.

Participant characteristics

| TCO (n = 10) |

Sleeve (n = 9) |

Control (n = 10) |

All (n = 29) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.6 ± 8.0 | 60.6 ± 11.3 | 63.7 ± 7.3 | 61.7 ± 8.8 |

| Sex (% female) | 40% | 55.6% | 40% | 44.8% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 ± 4.0 | 26.1 ± 4.0 | 29.1 ± 4.8 | 28.2 ± 4.5 |

| OA pattern (%) | ||||

| Patellofemoral | 20% | 0% | 0% | 7% |

| Bicompartmenta | 30% | 67% | 30% | 41% |

| Tricompartment | 50% | 33% | 70% | 52% |

| KOOS score | ||||

| Symptoms | 55 ± 12 | 51 ± 19 | 58 ± 18 | 55 ± 16 |

| Pain | 54 ± 17 | 50 ± 20 | 55 ± 12 | 53 ± 16 |

| ADL | 67 ± 13 | 60 ± 18 | 64 ± 10 | 64 ± 14 |

| S&R | 41 ± 22 | 24 ± 17 | 25 ± 16 | 31 ± 20 |

| QoL | 39 ± 18 | 26 ± 17 | 28 ± 11 | 31 ± 16 |

| Plans for TKA (%) | ||||

| Confirmed date | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Waiting list | 22% | 11% | 50% | 29% |

| No | 78% | 89% | 50% | 71% |

aBicompartment indicates involvement of the patellofemoral compartment and one of the tibiofemoral compartments

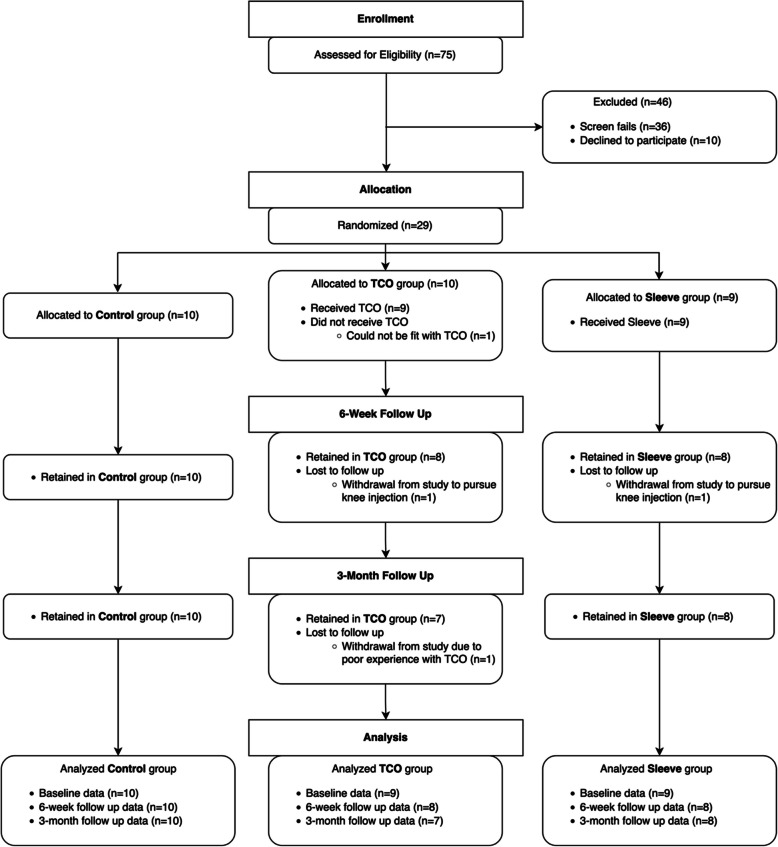

Participant flow through the study is presented in Fig. 2. Between March 2021 and July 2022, 75 individuals were assessed for eligibility and 29 were enrolled and randomised. Baseline data were collected on 29 individuals (10 Control, 9 Sleeve, 9 TCO), 6-week follow-up data were collected on 26 individuals (10 Control, 8 Sleeve, 8 TCO), and 3-month follow-up data were collected on 25 individuals (10 Control, 8 Sleeve, 7 TCO). Data collection commenced in July 2021 and finished in October 2022. Reasons for withdrawing from the study are presented below in “Dropout Rate”.

Fig. 2.

Flow of participants through the study for each intervention group (Control, TCO, and Sleeve)

OB1: feasibility

Table 7 summarises the feasibility progression criteria results. Recruitment and outcome data measures met the feasibility requirements, while intervention adherence was identified as an area requiring protocol improvements to progress to a full RCT.

Table 7.

Feasibility measures, progression criteria and outcomes

| Feasibility measure | Progression criteria | Outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Recruitment | |||

| Percentage of individuals eligible | Require 30% of individuals screened to meet eligibility criteria | 52% of individuals screened were eligible | Meets feasibility requirement |

| Percentage of individuals who consent to randomisation | Require minimum 50% study uptake | 74% of eligible participants enrolled | Meets feasibility requirement |

| 2. Intervention adherence | |||

| Device usage for participants in the Sleeve and TCO groups | Require minimum 60% of participants in the Sleeve and TCO intervention groups meet the recommended weekly device wear target of 21 h |

TCO group 6 weeks: 62% met target 3 months: 57% met target Sleeve group 6 weeks: 62% met target 3 months: 50% met target |

Device usage has been identified as a challenge and we recommend proceeding to the main trial following protocol changes to improve intervention adherence |

| 3. Outcome data | |||

| Retention in all intervention groups | Require minimum 80% completion rate | Follow-up rate at 3 months (primary endpoint) was 86% | Meets feasibility requirement |

| Outcome data collection–VAS knee pain (primary outcome variable) | Require valid primary outcome data for 80% of those recruited at baseline and the 3-month timepoint (Avery et al. 2017) | 100% response rate to primary outcome variable at all timepoints | Meets feasibility requirement |

Recruitment

Recruitment commenced in March 2021 and concluded in July 2022. There were 75 individuals screened, of which 36 (48%) were excluded because they did not meet eligibility criteria. The primary reasons for exclusion were using a non-study provided brace, not residing in Calgary, and not able to be fit with a TCO brace. Ten individuals (13%) declined to participate after learning about the study design, resulting in a total of 29 (39%) individuals being enrolled and randomised. Hence, 52% (39/75) of individuals screened met eligibility criteria, and of those eligible, 74% (29/39) enrolled in the study, meeting the feasibility criteria (Table 7). The study team closed recruitment at the end of July 2022, after enrolling 29 participants, due to limited resources available to continue to run the study.

Overall, there was a general willingness of clinicians to recruit participants for the study. Eighteen clinicians from 8 orthopaedic, sports medicine or primary care clinics in Calgary, Alberta agreed to recruit patients for the study. A total of 51 participants were identified by 12 clinicians (In-Clinic recruitment), with a range of 1–22 participants recruited per clinician. Six recruiting clinicians did not identify any eligible participants. The remaining 24 participants were recruited through Waitlist and Community recruitment via online advertisements, recruitment posters, and word of mouth.

It is important to note that recruitment was hugely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. When recruitment commenced in March 2021, recruitment opportunities were limited due to a small number of patients being assessed during clinic hours (or virtual assessments only) at recruitment sites, as well as wariness of patients to attend in-person study assessments. Furthermore, the University of Calgary ceased all non-essential in-person research activities for a 10-month period, which negatively impacted recruitment efforts and caused a significant delay in study assessments. This is confirmed by comparing recruitment numbers from 2021, when we experienced an average of 0.7 enrollments per month, with those from 2022, when we experienced a much higher average of 3.14 enrollments per month. This increase in recruitment rate can also be attributed to the introduction of Community and Waitlist recruitment pathways in 2022. We speculate that the rate of recruitment in 2022 is more reflective of typical recruitment for this study, when COVID-19 restrictions were lesser and all study recruitment strategies were in place. Therefore, based on the 2022 recruitment rate, the estimated recruitment timescale for a full single-centre RCT (93 participants) is estimated to be 30 months, or 2.5 years.

Intervention adherence

The TCO group reported wearing their device for an average of 43 h/week at 6 weeks, and 35 h/week at 3 months (Table 8). Overall, participants in the Sleeve group reported wearing their device less, with an average of 28 h/week at 6 weeks, and 24 h/week at 3 months (Table 8). On average, participants were wearing their device (TCO or Sleeve) more than the recommended minimum amount of 3 h per day (21 h/week) during weightbearing activities at both 6 weeks and 3 months. However, individual data shows that less than 60% of participants in each of the TCO and Sleeve groups met the recommended weekly device wear target at the 3-month timepoint (Table 8), not fulfilling the feasibility criteria. Device usage has therefore been identified as a challenge and we recommend implementing changes to the main trial protocol to improve intervention adherence.

Table 8.

Participant device use for the TCO and Sleeve intervention groups reported in hours per week [Average (Range)] and percentage of individuals in each group who met the minimum recommended weekly device wear target

| 6 weeks (hours/week) |

6 weeks (% group meeting target) |

3 months (hours/week) |

3 months (% group meeting target) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCO | 43 (6–105) | 62% | 35 (18–70) | 57% |

| Sleeve | 28 (8–56) | 62% | 24 (0–56) | 50% |

Outcome data

Overall follow-up rates were 90% (26/29) at 6 weeks, and 86% (25/29) at 3 months, which met the feasibility requirement for completion rate (Table 7). All participants who were actively enrolled in the study completed the required surveys and participated in the in-person strength and functional assessments. The response rate to the primary outcome variable of knee pain (VAS) was 100% at all timepoints, meeting the feasibility requirement for outcome data collection (Table 7). However, 23–41% of active participants had missing or incomplete medication use data, and 23–36% had missing or incomplete allied health services data (Table 9). There were also low response rates on questions regarding body pain in other areas of the body, mobility aids and injections.

Table 9.

Number of active study participants with missing or incomplete survey data in the areas of medication use and allied health services

| Baseline | 6 weeks | 3 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication use | 12/29 (41%) | 6/26 (23%) | 6/25 (24%) |

| Allied health services | 9/29 (31%) | 6/26 (23%) | 9/25 (36%) |

All participants completed baseline strength and functional testing. However, at the 3-month follow-up, there were 2 participants (8%) who could not perform the strength tests on the affected limb due to pain in the affected limb, one of whom could not perform the functional tests either.

Dropout rate and adverse events

There were 4 (14%) participants who dropped out of the study, 3 from the TCO group and 1 from the Sleeve group (Table 10). In the TCO group, one participant was diagnosed with a meniscal tear after completing the baseline assessment and being fitted with the TCO brace, and as a result, withdrew from the study to pursue injection therapy. Another participant in the TCO group dropped out following baseline assessment because they could not be fit with the TCO brace. A third participant in the TCO group dropped out following the 6-week assessment due to a poor experience with the TCO. In the Sleeve group, one participant dropped out following the baseline assessment to pursue injection therapy. No participants dropped out of the study due to their intervention group allocation.

Table 10.

Summary of dropouts and adverse events for each intervention group

| TCO | Sleeve | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total dropouts, n (%) | 3 (10.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 |

| Could not be fit with device | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| Injection therapy | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Poor experience with device | 1 | 0 | n/a |

| Total adverse events, n (%) | 3 (10.3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Pain during device use | 1a | 0 | n/a |

| Pain following device use | 1a | 0 | n/a |

| Hamstring pain | 1 | 0 | 0 |

aThe participant dropped out of the study

There were 3 adverse events reported throughout the duration of the study, reported by 3 (10%) participants (Table 10). All adverse events were reported by participants in the TCO brace intervention group. Adverse events included knee pain during or following TCO use, and hamstring pain. No adverse reactions to TCO brace or sleeve materials were reported.

OB2: knee pain

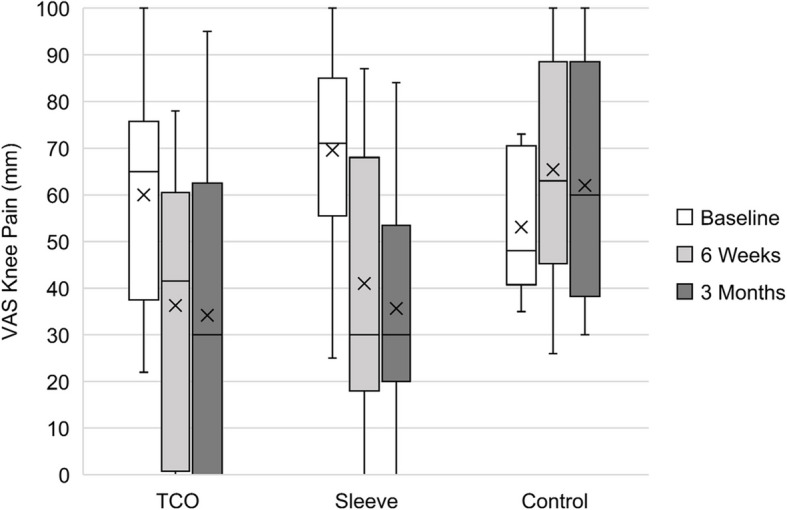

Table 11 presents the distributional properties of the participant reported VAS knee pain score for four different activities including walking on a flat surface (walk), squatting (squat), going up and down stairs (stairs), and rising from sitting (chair). Median pain scores decreased from baseline to 3 months for all four activities for the TCO and Sleeve groups, and increased for the Control group. Figure 3 illustrates knee pain during squatting for each intervention group at each study timepoint. This plot highlights the differences in median baseline pain scores for the three intervention groups, with the Sleeve group having the highest (worst) baseline knee pain during squatting, and the Control group having the lowest (best).

Table 11.

VAS knee pain scores [Median (IQR)] during four activities for three intervention groups (TCO, Sleeve, Control) at baseline (Base), 6 weeks (6 W) and 3 months (3 M). The change between baseline and 3 months (3 M minus Base) is also presented for each group [Median (IQR)]

| Walk | Squat | Stairs | Chair | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCO | Base (n = 10) |

30.0 (26.0, 30.0) |

65.0 (40.0, 75.0) |

59.5 (50.0, 70.0) |

46.50 (41.0, 62.0) |

|

6 W (n = 8) |

17.0 (12.0, 59.5) |

45.0 (32.0, 65.0) |

45.0 (22.5, 69.5) |

44.0 (27.0, 69.5) |

|

|

3 M (n = 7) |

20.0 (10.0, 53.0) |

43.0 (29.0, 76.0) |

43.0 (23.0, 83.0) |

32.0 (10.0, 75.0) |

|

|

Change (n = 7) |

− 4.0 (− 10.0, 18.0) |

− 20.0 (− 42.0, 3.0) |

− 7.0 (− 25.0, 8.0) |

− 6.0 (− 18.0, 20.0) |

|

| Sleeve |

Base (n = 9) |

59.0 (10.0, 70.0) |

71.0 (66.0, 80.0) |

80.0 (50.0, 87.0) |

67.0 (49.0, 79.0) |

|

6 W (n = 8) |

27.0 (10.0, 57.0) |

40.0 (29.5, 68.0) |

45.0 (30.0, 65.5) |

34.0 (21.0, 51.0) |

|

|

3 M (n = 8) |

25.0 (10.0, 51.5) |

30.0 (27.50, 53.5) |

48.5 (30.0, 60.0) |

37.0 (17.50, 59.5) |

|

|

Change (n = 8) |

− 7.5 (− 29.5, 1.0) |

− 40.5 (− 45.5, − 21.5) |

− 30.5 (− 40.0, − 15.0) |

− 22.5 (− 32.0, − 17.5) |

|

| Control |

Base (n = 10) |

38.0 (28.0, 51.0) |

48.0 (41.0, 70.0) |

59.0 (40.0, 66.0) |

50.0 (23.0, 60.0) |

|

6 W (n = 10) |

40.0 (39.0, 67.0) |

63.0 (47.0, 88.0) |

67.0 (49.0, 74.0) |

48.5 (45.0, 72.0) |

|

|

3 M (n = 10) |

45.5 (18.0, 63.0) |

60.0 (40.0, 85.0) |

62.5 (52.0, 80.0) |

56.0 (16.0, 62.0) |

|

|

Change (n = 10) |

2.5 (− 15.0, 10.0) |

5.0 (− 2.0, 27.0) |

1.5 (− 5.0, 15.0) |

2.0 (− 1.0 16.0) |

Fig. 3.

Participant reported VAS knee pain scores during squatting for three intervention groups (TCO, Sleeve, Control) at baseline, 6 weeks and 3 months. The black centre line denotes the median value (50 th percentile), the X represents the mean, and the box contains the 25 th to 75 th percentiles of the dataset. The black whiskers mark the 5 th and 95 th percentiles

Sample size calculation

The mean change in VAS knee pain during squatting between baseline and 3 months was − 15.1 ± 23.3 mm for the TCO group, − 32.5 ± 19.7 mm for the Sleeve group, and 8.9 ± 18.0 mm for the Control group. A sample size of 78 individuals (26 per group) is estimated to detect a between-group difference of 17.4 mm (the smallest between group difference, Sleeve vs. TCO) in the change in knee pain during squatting over time (baseline to 3 months) at 80% power and alpha of 0.05. We inflated the sample to 93 individuals (31 per group) to account for potential losses to follow-up (20%).

OB3: optimise protocol

Several changes were made to study eligibility criteria following the commencement of participant recruitment to improve trial feasibility (Table 12). These changes were informed by feedback from recruiting clinicians regarding criteria they perceived as barriers to recruitment, as well as information collected from interactions and during the screening process where conditions arose that were not initially contemplated. Changes to recruitment criteria were always discussed with the team’s patient partners to understand the implications from a patient perspective. Research team members received ethics board approval prior to the implementation of all changes.

Table 12.

Changes to participant eligibility criteria

| Criteria | Initial criteria | Final criteria | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 45–75 years old | 18–80 years old | This change was made in an effort to be more inclusive of individuals with knee OA across the lifespan [44]. The original lower age limit of 45 was deemed overly restrictive, since all participants underwent radiographic confirmation of moderate to severe patellofemoral or multicompartment knee OA based on Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grading during screening. Moreover, several published knee OA brace intervention trials have included individuals ≥ 80 years, or not included an upper age limit [45], prompting the increase of the upper eligible age limit |

| Contralateral knee pain | Pain in contralateral knee must be less than 20 mm (VAS) | Must report lower VAS pain score in the contralateral knee compared to the affected knee during weight-bearing activities | Since pain is systemic, any significant contralateral knee pain may affect the reporting of knee pain in the affected (study) limb. However, given the prevalence of individuals with knee OA who report bilateral knee pain [46], this criterion was deemed overly restrictive |

| Knee pain location | Pain under the kneecap or at the front of the knee that worsens during weightbearing activity | Knee pain that worsens with walking on inclined terrain, going up and down stairs, squatting or rising from a seated position | Specifying an anterior origin of knee pain that worsened during weightbearing activity could unnecessarily exclude potential participants with pain not localised to the anterior knee, or pain that is masked by greater lateral or medial knee pain |

| Injection therapy | Individuals were excluded if they had received any knee injection therapies in the affected (study) limb less than 3 months prior to study participation | Individuals were excluded if they: (a) received corticosteroid injections in the affected knee in the last 3 months, or (b) received hyaluronic acid or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections in the affected knee in last 6 months | This change was informed by available evidence on the therapeutic window of corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid and PRP knee injections [47–49] |

| Surgery | Exclusion of individuals who had undergone any lower limb surgery within the last 6 months | Exclusion of individuals who had undergone: (a) surgery (excluding arthroscopy) on either lower limb within the last 6 months, or (b) arthroscopic debridement of the affected knee within the last 3 months | This change was informed by clinical evidence suggesting that the recovery period for arthroscopic debridement is less than 3 months |

| Knee brace use | n/a | Exclusion of individuals using a non-study provided knee brace on the affected limb during the study period | This change was implemented to ensure greater experimental rigor by specifying that participants allocated to the intervention or control groups should not use a knee brace on the affected limb during the study period, as this would introduce a confounding variable |

| TCO Knee Brace Sizing | Able to be fit with a Levitation TCO knee brace | Able to be fit with a Levitation TCO knee brace (based on leg measurements, leg alignment and leg inseam). Confirmed by study coordinator and, when necessary, the SLT engineering team | This change was made after a participant was enrolled who could not be fit with a Levitation TCO knee brace due to leg shape and circumference following randomisation to the TCO brace group |

In addition, the participant recruitment strategy was expanded in January 2022 to allow for recruitment from patient waitlists (i.e. Waitlist Recruitment) and the larger community (i.e. Community Recruitment). A screening clinic was added to determine participant eligibility from these two additional recruitment channels. This change, spearheaded by the patient partners, was implemented to improve the rate of participant recruitment and to ensure the study was accessible to the larger knee OA population, not only the small percentage of patients who were able to see a sports medicine clinician or orthopaedic surgeon. From January 2022 to July 2022, 24 participants (32%) were identified via Waitlist and Community recruitment channels. Twelve participants went on to attend one of 4 screening clinics, of which, 10 were enrolled in the study.

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was initially selected to measure participant-reported physical activity due to its use in comparable trials and easy conversion to a metabolic equivalents score. However, the IPAQ comprises several questions that are highly demanding of participants’ ability to recall the amount of time engaged in different intensities and types of physical activity. The Lower Extremity Activity Scale (LEAS), designed to assess physical activity in individuals with hip or knee OA [37], was later identified as a more suitable measurement tool for measuring physical activity in this study due to its appropriateness for the population, simplicity and ease of scoring for analysis and reporting purposes. All active participants completed the LEAS at all study timepoints. The survey questions used to collect medication use were also modified during the study to improve ease of completing this section. Three medication categories were removed (Antidepressants, Medical marijuana, and Other) to focus on medications that address physical pain. Furthermore, instead of asking for participants’ average dosage in milligrams, the survey was modified to ask how many pills they consumed at a time. This was easier for participants to report, while still enabling the assessment of differences over time in medication use. The patient partners were closely involved in the decision-making process for both of the above changes to data collection.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether it is feasible to deliver a definitive RCT comparing clinical outcomes of using the Levitation TCO knee brace to the current (conservative) standard of care treatment for individuals with knee OA, and to refine trial procedures ahead of the full RCT. The feasibility study included adults with moderate to severe multicompartment or patellofemoral knee OA. Participants in each intervention group reported median baseline knee pain levels that were higher than the patient acceptable symptom state for knee OA patients of 32.3 mm [26] during all activities, except the TCO group during walking, which had a median of 30.0 mm. This indicates that overall, participants did not consider themselves well from a knee pain perspective.

OB1: feasibility

The primary study objective was to evaluate trial feasibility, including participant recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome data, dropout rate, and adverse events. Recruitment was a challenge for this study and was severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, the feasibility criteria were satisfied. Overall, 29 participants were enrolled in the study over a 17-month period. Of the participants who met the eligibility criteria, 74% enrolled, demonstrating willingness of individuals to enroll in the study. Changes were made during the study to make the participant eligibility criteria less restrictive, and additional recruitment channels were added to improve the number of individuals screened for participation. As a result, the average rate of enrollment over the final 7 months of the study was 3 participants per month, which is reasonable given the strict study qualification criteria. We demonstrated clinician willingness to identify potential participants based on initial screening criteria, with 18 clinicians in the area actively recruiting. The recruitment timeline for a full scale RCT was estimated to be 2.5 years, based on the estimated sample size of 93 participants and an average rate of enrollment of 3 participants per month. However, this could be improved through further improvements to operational procedures and by increasing the number of recruitment sites.

The feasibility criteria for intervention adherence were not satisfied, and was therefore identified as a challenge. While the average reported device wear time exceeded the suggested minimum of 21 h per week in both the TCO and Sleeve groups at 6 weeks and 3 months, less than 60% of participants in either group met this target at 3 months, suggesting an area for further improvement and exploration. The average device wear time decreased between 6 weeks and 3 months for both groups, which is common in knee OA bracing studies [51]. On average, the TCO group wore their device more than the Sleeve group, with the TCO group reporting an average of 15 and 11 h more device use per week compared to the Sleeve group at 6 weeks and 3 months, respectively (Table 8). Importantly, there was a wide range of device wear times within each group, as shown in Table 8, demonstrating high variability in how much participants wore their device within each group. We recommend changes to the protocol to improve intervention adherence prior to proceeding with a full RCT, such as implementing regular follow-up with participants on device wear or incorporating a sensor-based monitoring device to track daily brace or sleeve wear.

The feasibility criteria for outcome data were both satisfied. Participant follow-up rates were excellent, with 86% of participants completing the primary endpoint of 3 months. The high follow-up and response rates suggest acceptability of the assessment tools and intervention protocol. The primary outcome variable, VAS knee pain, had a 100% response rate for active study participants, confirming that this is a reliable primary outcome measure for the full RCT. There were sections of the survey that suffered from poor completion rates, including medication use and allied health services, highlighting areas for improvement. Although changes were made to data collection for medication use, this could be further improved in future studies. The in-person strength and functional testing was well attended and well tolerated. All participants completed this testing at baseline, and all active participants attended the testing at 3 months, suggesting that the protocol was reasonable and acceptable. However, two participants were not able to complete parts of the strength and functional testing at 3 months due to knee pain in the affected limb, which should be a consideration for future studies.

The total dropout rate in this study was 14%. The majority of dropouts were in the TCO group, with reasons including not able to be fit with the device, pursuing injection therapy, and having a poor experience with the device. Changes were made to the study screening criteria following the incident of a participant not being able to be fit with the TCO to prevent recurrence. In the sample size calculation for the full RCT, we have allowed for a 20% dropout rate to account for the longitudinal study design, which is reasonable given the observed 14% dropout rate in this feasibility study. Three participants in the TCO group reported an adverse event during the study, none of which necessitated a report to the ethics committee. Adverse events included knee pain during or following TCO use, and hamstring pain. The insights gained from this study on participant experience being fitted with and using the TCO can also be used to help the manufacturer (SLT) improve aspects of the device design, such as ability to fit a broader range of individuals and improved brace comfort, prior to launching a full RCT.

Our findings suggest that a future RCT powered to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the Levitation TCO knee brace for individuals with knee OA is feasible based on the observed recruitment rate and outcome data measures. However, protocol changes are recommended to address intervention adherence prior to progressing to a full RCT. It is suggested that a full RCT would require 93 participants in 3 intervention groups, and the estimated timeframe for participant recruitment is 2.5 years.

OB2: knee pain

The second objective was to evaluate the distributional properties of the VAS activity-specific knee pain score to estimate the sample size required for a full RCT. We calculated a conservative sample size of 93 individuals (31 per group) to detect a between-group difference in the primary outcome measure of change over time in VAS knee pain during squatting. This sample size calculation was then used to inform the timeline for a full RCT, discussed below. The sample size estimate is based on a relatively small sample; therefore, it is recommended that this calculation be revised as further data is available. Importantly, the estimated sample size was not used to determine the feasibility of proceeding to a full RCT, but rather, to inform the design of the full RCT.

The Sleeve and TCO groups both reported improvements in knee pain between baseline and 3 months, while the Control group reported slight increases in knee pain over the intervention period. The median change in knee pain over the intervention period for squatting was − 20.0 mm and − 40.5 mm for the TCO and Sleeve groups, respectively. This magnitude of change is greater than the minimum clinically important improvement in VAS knee pain of −19.9 mm for knee OA patients [50], which indicates a clinically important improvement in knee pain.

The Sleeve group tended to report greater median improvements in VAS knee pain during all activities from baseline to 3 months compared to the TCO group. When looking at the IQR data of the change in knee pain over time (Table 6), it’s apparent that there was a range of responses to the intervention within each group. In the TCO and Control groups, the IQR includes both positive and negative changes, demonstrating that some participants experienced improvements in knee pain while others did not. In the Sleeve group, the IQR endpoints are both negative, with the exception of walking, indicating an improvement in knee pain over time for the vast majority of individuals in that group. The Sleeve group had a slightly higher proportion of females, and a higher proportion of individuals with bicompartment knee OA compared to the other intervention groups, which may have influenced their response to the intervention. Participants in the Sleeve group also reported higher baseline levels of knee pain during all activities compared to the TCO and Control groups. Individuals with higher starting pain scores need to experience a larger change in order to consider themselves improved [50]. Therefore, the larger improvements in knee pain reported by the Sleeve group may be a result of their higher starting pain scores, requiring a larger magnitude of change to experience an improvement from the intervention relative to the TCO and Control groups, who had lower baseline knee pain. Typically, the randomisation process results in an even distribution of baseline characteristics between groups. However, despite randomisation and given the small sample size in this study, the discrepancy in baseline pain scores has presented by chance. While these findings are interesting, this study is not powered to draw any conclusions on the clinical effectiveness of the TCO brace compared to the sleeve or standard of care from this data, and this was not the aim of the study.

OB3: optimise protocol

The third objective was to refine and optimise the study protocol to improve feasibility, efficiency and appropriateness for a full RCT. There were several changes made to eligibility criteria throughout the study to improve participant recruitment. The age range was increased, which allowed 3 participants (10%) to participate who would have otherwise been excluded. Other changes included modifications to criteria regarding contralateral knee pain and the location of knee pain in the affected limb, timeframes for recovery from arthroscopic surgery and the therapeutic window of HA and PRP injections. The above changes were implemented to make the study eligibility criteria less restrictive and more representative of individuals seeking solutions for knee OA pain. The criteria to determine whether an individual could be fit with a TCO brace were modified, which included measures of participant height, leg circumference and leg alignment. There were no post-randomisation exclusions related to these criteria following this change. Lastly, exclusion criteria were added so that anyone using another knee brace on the affected limb was not eligible to participate in the study, as this would interfere with determining the effect of the study interventions. The addition of Waitlist and Community recruitment channels was very successful, with 24 participants (32%) identified from these channels in the final 7 months of recruitment (3.4 participants/month). Changes to data collection included changing the survey used to assess physical activity level to one that was designed specifically for the OA population and was significantly easier and quicker to fill out, resulting in a 100% response rate. Additionally, we simplified how medication use data was collected to improve ease of completing this survey section. Nevertheless, issues remained with the reporting of medication use, and we suggest further action to improve this section of the survey.

Limitations

A key limitation associated with this feasibility study is the small sample size and differences in knee OA patterns across intervention groups, which resulted in an imbalance in baseline knee pain between intervention groups. It is therefore important that the findings of this study are not interpreted as evidence that supports or does not support the clinical effectiveness of the TCO brace in individuals with patellofemoral or multicompartment knee OA, providing further motivation for a larger-scale RCT. The study eligibility criteria excluded individuals who could not be fit with a TCO knee brace, those with a history of injury or surgery, and those with a number of other health conditions. Participants were only recruited from clinics and the greater community in a single metropolis (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Given the strict eligibility criteria and limited sample size, the study population may not be representative of the average person with symptomatic knee OA, and therefore the findings may not be generalisable across all brace users with knee OA. Finally, the intervention endpoint for this study was 3 months, therefore the results may not be reflective of long-term brace use.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are proposed for a full RCT evaluating the Levitation TCO knee brace in individuals with knee OA. In this feasibility study, participants were required to have KL grading performed by a clinician based on radiographs taken within the last year. This was an overly restrictive criteria, and it is recommended that instead, participants provide written confirmation of a knee OA diagnosis from a clinician. KL grading can then be performed retrospectively, for reporting purposes only. It is also recommended that the inclusion and exclusion criteria be further simplified to improve the rate of recruitment as well as the generalisability of the results to the knee OA population. There was a discrepancy between intervention groups in baseline knee pain and the distribution of knee OA patterns. While this is likely due to the small sample size, it is recommended to consider including these factors in the randomisation procedure to achieve more similar groups. The majority of dropouts and all of the adverse events were in the TCO intervention group. Many were related to a poor experience with the brace resulting from brace discomfort or pain during or after use. Following the start of this feasibility study, SLT released a newer version of the brace, Spring Loaded OA, that is designed to be lighter, more comfortable, more accommodating to various leg shapes and sizes, and the assistance level is highly adjustable. It is recommended that the new TCO brace design be used in the full RCT, as the design used in the current study is no longer available. Additionally, given the improvements to the new TCO brace model, it is possible that the comfort and pain issues would not be as prevalent. Finally, there were a number of participants (11%) who were eligible but decided not to enroll in the study after learning the study design (i.e. that they were not guaranteed to get the TCO brace). While this is to be expected, it is recommended to consider an alternative study design, such as a crossover design, which may be more attractive for study participants.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that conducting a larger scale RCT evaluating the clinical effectiveness of the TCO knee brace for knee OA is feasible in terms of recruitment rate and outcome data, with protocol changes recommended to improve intervention adherence. The current research evidence is the foundation for demonstrating the biomechanical and clinical effectiveness of the TCO brace, and the quality and breadth of current research differentiates the TCO from other available knee OA braces [18, 21–23, 25]. However, continuing to build the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of the TCO for addressing knee OA symptoms would further build prescriber and user confidence and adoption. Therefore, an adequately powered RCT evaluating the effectiveness of the TCO brace compared to the current (conservative) standard of care treatment for individuals with knee OA is recommended.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. Participant Baseline Survey

Supplementary material 2. Participant Follow-up Survey

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Preston Wiley, Dr. Stephen French, Dr. Ivan Wong, Dr. Courtney Brown, and Dr. Nicholas Mohtadi for conducting an in-depth review of the study protocol. We would like to acknowledge Deb Baranec, Anita Wamsley, Marisa Vigna, Shelly Longmore, Gail Haines, Tom Neifer and Paul Kerber for being patient partners. We would like to thank Dr. Linda Mrkonjic, Dr. Trevor Trinh, Dr. Margot McLean, Dr. Jonathan Okrainetz, Dr. Neesha Patel, Dr. Elana Taub, Dr. Stephanie Mullin, Dr. Eldridge Batuyong, Dr. Denis Joly, Dr. Kelly Johnston, Dr. Stephen Miller, Dr. Richard Ng, and Emma Smith for recruiting participants into this study. We would like to thank Ken Laidlaw and team at Colman Prosthetics and Orthotics for providing TCO brace fittings. We would like to thank Spring Loaded Technology for in-kind provision of the TCO knee braces. We would like to acknowledge and thank Bo Pan and Dr. Yazid Hamarneh of the Alberta SPOR Support Unit Consultation and Research Services for their contribution to the biostatistics analysis and support for this study. Finally, we would like to say a big thank you to the participants of this study for their time and contribution to this research project.

Abbreviations

- EQ-5D

EuroQol 5D

- IQR

Interquartile range

- KL

Kellgren-Lawrence

- KOOS

Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score

- LEAS

Lower Extremity Activity Scale

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- OB

Objective

- OPUS-CSD

Orthotics Prosthetics User Survey–Satisfaction with Devices

- POR

Patient-oriented research

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SLT

Spring Loaded Technology

- TCO

Tri-compartment offloader

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- 3M

3 Months

- 6 W

6 Weeks

Authors'contribution

ELB, CCS, JLR, and MLC conceived the study and obtained funding. ELB, JB, JLR, and MLC designed the trial protocol with input from CCS. JB conducted participant recruitment with assistance from MLC. ELB, JB, and MJ conducted data collection. ELB and JB conducted data analyses, with input from JLR and MLC. ELB and JB drafted the manuscript with input from MJ, CCS, JLR, and MLC. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Patient-Oriented Research Catalyst Grant (169387), the Cumming School of Medicine Clinical Research Fund, the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health, and the Alberta Bone and Joint Health Strategic Clinical Network (Alberta Health Services). ELB was supported by a Mitacs Accelerate Postdoctoral Scholarship.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research,425086,Janet Lenore Ronsky,Mitacs,IT13127,Emily Lynn Bishop,Cumming School of Medicine,University of Calgary,Clinical Research Fund,Marcia L. Clark,Bone and Joint Health Strategic Clinical Network,Facilitation Funding Opportunity,Janet Lenore Ronsky,McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health,Facilitation Funding Opportunity,Janet Lenore Ronsky

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB 20–1106). All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ELB is supported by a Mitacs Accelerate Postdoctoral Fellowship on which the partner organisation is Spring Loaded Technology. JLR receives research funding from Spring Loaded Technology. CCS is a cofounder and current board member of Spring Loaded Technology. CCS and Spring Loaded Technology employees were not involved in the analysis, interpretation or reporting of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Birtwhistle R, Morkem R, Peat G, Williamson T, Green ME, Khan S, et al. Prevalence and management of osteoarthritis in primary care: an epidemiologic cohort study from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network. C Open [Internet]. 2015;3:E270–5. Available from: http://cmajopen.ca/cgi/doi/10.9778/cmajo.20150018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Sharif B, Kopec J, Bansback N, Rahman MM, Flanagan WM, Wong H, et al. Projecting the direct cost burden of osteoarthritis in Canada using a microsimulation model. Osteoarthr Cartil [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2015;23:1654–63. Available from: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, Cirillo PA, Walker AM. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoddart JC, Dandridge O, Garner A, Cobb J, Arkel RJ Van. The compartmental distribution of knee osteoarthritis e a systematic review and meta-analysis Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2021;29:445–55. Available from: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Davies-Tuck ML, Wluka AE, Wang Y, Teichtahl AJ, Jones G, Ding C, et al. The natural history of cartilage defects in people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S, Hawker GA, Laporte A, Croxford R, Coyte PC. The economic burden of disabling hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) from the perspective of individuals living with this condition. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. Knee replacement. Lancet [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2012;379:1331–40. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60752-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee a randomized, controlled trial. 2000;132:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2014 [cited 2014 Mar 21];22:363–88. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24462672 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Steadman RJ, Briggs KK, Pomeroy SM, Wijdicks C a. Current state of unloading braces for knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2016;24:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennell KL, Dobson F, Hinman RS. Exercise in osteoarthritis: moving from prescription to adherence. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol Elsevier Ltd. 2014;28:93–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felson DT. The sources of pain in knee osteoarthritis: editorial review. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:624–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks KS. Osteoarthritic knee braces on the market: a literature review. J Prosthetics Orthot. 2014;26:2–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhaar J a N, LNJEM Coene, Bierma-Zeinstra SM a. Brace treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective randomized multi-centre trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2006;14:777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherian JJ, Bhave A, Kapadia BH, Starr R, McElroy MJ, Mont M a. Strength and functional improvement using pneumatic brace with extension assist for end-stage knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, randomized trial. J Arthroplasty [Internet]. Elsevier Inc.; 2015;30:747–53. Available from: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Kuster MS. Exercise recommendations after total joint replacement: a review of the current literature and proposal of scientifically based guidelines. Sport Med. 2002;32:433–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]