Abstract

Experiencing gender-based violence (GBV) is associated with health conditions that are common indications for referral to exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and other allied health professionals (AHPs). The readiness of AHPs to identify and respond to GBV is currently unknown. This study aimed to determine the readiness of AHPs to respond to a person who had experienced GBV. Participants completed the modified Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) and/or an interview. The AHPs felt underprepared, had low perceived knowledge and lacked confidence to respond to and support people who have experienced GBV, despite recognition of the importance and agreement of the relevance to AHPs’ practice.

Keywords: mental health, physical health, health outcomes, health professionals, training

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a broad term that includes sexual violence and intimate partner violence. A common feature of GBV is that women and LGBTIQ + people are impacted disproportionately, and it is interrelated with an unequal distribution of gendered power and dominance in relationship (Hegarty et al., 2022). GBV leads to short-term and long-term physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health complications (Chandan et al., 2020; Lum On et al., 2016; Rees et al., 2011; World Health Organisation, 2018). GBV is the largest contributing risk factor to the burden of disease for Australian women aged 18–44 years, exceeding the public health problems associated with alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking (Webster, 2016).

Nearly one-third (30%) of women globally are subjected to physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime (World Health Organisation, 2018), and more than one in four (26%) have experienced violence from a current or previous intimate partner since the age of 15 (The World Bank, 2022). In Australia, one in five women over the age of 15 have experienced sexual violence, and one in six women over the age of 15 have experienced physical or sexual violence by a current or past partner (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019). For LGBTIQ + people in Australia, a 2019 national survey found 61% of respondents had experienced intimate partner violence and 49% had experienced sexual assault (Hill et al., 2020).

People experiencing GBV have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, injuries, chronic pain syndromes and all-cause mortality compared to those who have not experienced GBV (Chandan et al., 2020; Dillon et al., 2013; Jakubowski et al., 2021; Loxton et al., 2006). People who have experienced GBV are twice as likely to experience depression and more likely to experience anxiety disorders compared to those who have not been exposed to GBV (Dillon et al., 2013; World Health Organisation, 2018). In Australia, anxiety and depressive disorders contributed to more than two-thirds of the disease burden associated with GBV in women aged 18–44 years (Webster, 2016). Common mental disorders and suicidal behaviour have a high rate of onset one- and five-years following exposure to GBV in women without prior mental disturbance (Rees et al., 2014). There was a particularly high incidence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the first year following exposure to GBV (Rees et al., 2014). Between 31% and 84% of people who have experienced GBV, meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD depending on sample and GBV characteristics (Pill et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2013; Zinzow et al., 2012). Other mental health consequences associated with experiencing GBV include eating disorders, suicidal ideation, sleep difficulties, poor body image and emotional dysregulation (Stubbs & Szoeke, 2021; Webster, 2016).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) identified two key roles of the health sector in preventing and responding to GBV, i) early identification, appropriate referral and support, and ii) providing comprehensive services, sensitizing and training healthcare providers in responding to survivors’ needs, holistically and empathetically (World Health Organisation, 2018). Survivors of GBV are more likely to seek healthcare and interact with healthcare professionals compared to those who haven’t been exposed to GBV (Bonomi et al., 2009; García-Moreno et al., 2015). Predominant disease correlates of GBV, such as chronic pain, cardiometabolic risk factors, depression and anxiety, are common reasons for referral to allied health professionals. Health professionals are therefore uniquely positioned to provide an immediate, or first-line, response to survivors/victims of GBV (McLindon et al., 2021), and could play a key role in the identification, prevention and reduction of GBV-related physical and mental health consequences.

Healthcare providers may frequently, and unknowingly, encounter survivors/victims of GBV (García-Moreno et al., 2015), including allied health professionals who work across a wide range of healthcare settings. Exercise physiologists, physiotherapists, dietitians and other allied health professionals (AHPs) provide interventions that target modifiable behaviour including nutrition and physical activity for the treatment and management of injury, disease, or chronic conditions (Academy Quality Management, 2018; Allied Health Professions Australia, 2022). AHPs who deliver exercise and diet interventions could play a role in reducing the physical and mental health consequences associated with experiencing GBV including reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD, improving body image, reducing cardiovascular risk and improving physical function (Heissel et al., 2023; Pebole et al., 2021; Van de Kamp et al., 2023). For example, interventions that promote physical activity can promote positive mental health and reduce depressive symptoms in people who have experienced GBV (Chuang et al., 2012; Concepcion & Ebbeck, 2005; Mburia-Mwalili et al., 2010). Exercise has also been shown to reduce symptoms of PTSD (Björkman & Ekblom, 2022; Sheppard-Perkins et al., 2022). In addition, healthy dietary patterns can reduce symptoms and risk of depression (Firth et al., 2020; Jacka et al., 2017; Lassale et al., 2019).

Trauma-informed health professionals and services have an increased understanding of victims/survivors of GBV needs, optimising intervention outcomes and minimising negative interactions with the healthcare system (McLindon et al., 2021; Pebole et al., 2020). Trauma-informed care (TIC) is underpinned by a basic understanding that trauma affects the lives of many individuals and the role that violence plays in the lives of people seeking a service (McLindon et al., 2021; Quadara, 2015). Trauma-informed health professionals and services improve opportunities for people who have experienced GBV to engage with health services, provide a sense of safety, improve screening, assessment processes and treatment planning, avoid negative interactions with health services and contribute to reducing the health impacts of trauma (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014).

There have been calls for an Australian national strategic direction that promotes TIC (Bateman et al., 2013; Palfrey et al., 2019), and trauma-informed frameworks are increasingly being integrated into mental health and social services in Australia. Health professionals commonly working in these settings such as psychologists, counsellors and social workers are likely to have been trained in providing TIC. The capability of other AHPs such as physiotherapists or exercise physiologists to provide TIC when responding to GBV is unknown, with emerging research suggesting that sufficient training is not being delivered to healthcare professionals, and that they’re entering the workforce feeling underprepared to manage GBV (McLindon et al., 2021). This is a significant gap in knowledge given the high prevalence of GBV and its associated health conditions.

This project aims to determine the readiness of tertiary-educated exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and other allied health professionals in responding to a person who has experienced GBV. This includes knowledge, attitudes and preparedness with screening and referral for acute crisis help, and the considerations and potential impacts of interventions that support recovery from short- and long-term physical and mental health consequences of GBV. We hypothesised that these AHPs would have limited GBV knowledge and low preparedness to respond to a person who has experienced GBV.

Methods

This project used a mixed methods approach involving qualitative and quantitative data. Data collection included an online survey and semi-structured interviews. A mixed methods approach was adopted for two main purposes: One) complementarity, where the qualitative data was used to enrich and explain trends in the quantitative data and two) Confirmation, where the results of the two methods converge and are used to confirm each other (O'Cathain et al., 2007). Data were collected from September 2021 until March 2022. Ethical approval was obtained through the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC210652). Reporting has been done in accordance with the CHERRIES checklist for reporting on results of internet e-surveys (Eysenbach, 2004).

Participants

Eligible participants were tertiary qualified AHPs over the age of 18 years. AHPs are defined as health professionals who are not part of the medical, dental or nursing professions. They are tertiary qualified practitioners who specialise in preventing, diagnosing and treating a range of conditions and illnesses (Allied Health Professions Australia, 2022). In Australia, there are 25 types of AHPs and there is significant variation in scope across and within professions. Australian AHPs are tertiary educated and each separate allied health profession is regulated by their own national organisation. To determine what occupations were included as allied health we used a list of occupations taken from the Australian government list of AHPs which can be found in the supplementary material (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2021). Sampling methods focused on exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and dietitians.

Study recruitment involved researchers posting the study advertisement to social media (e.g.,: Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn). Recruitment efforts were targeted at an Australian audience, however, there was an opportunity for participants from other countries to take part. This included social media pages of organisational bodies for relevant AHPs including: Exercise and Sports Science Australia, Australian Physiotherapy Association and Dietitians Australia. Recruitment materials disclosed participants would be asked questions about sensitive topics such as sexual violence and intimate partner violence. Study data were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted and managed by Research Technology Services (UNSW Sydney) (Harris et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2019). A link to the online 20-min open survey delivered through Redcap was included on recruitment materials. A Participant Information Statement and Consent Form was provided at the start of the online survey and the participants had to answer the consent question before starting the survey. Potential respondents to the survey could indicate their willingness to participate in an additional interview by contacting the research team directly via email using the contact details available on the recruitment materials. Usability and technical functionality of the online survey was tested before fielding the survey.

Demographics

The respondent profile section in the online survey included a yes or no eligibility question if the respondent was a tertiary qualified AHP. Categorical data collected included age, gender, country, highest level of education, current position title, main area of employment, average paid hours of employment per week, number of years of practicing, how many hours of GBV training received and where the training was received. Demographic data collected from interviews included participants’ gender and occupation.

Quantitative Outcomes

Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence (PREMIS) Survey

A modified version of the Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) was used. PREMIS is a validated tool used to assess physician knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour and skills regarding GBV (Short et al., 2006). It has been widely used to inform training needs of healthcare professionals regarding GBV (Renner et al., 2019; Saboori et al., 2021; Sawyer et al., 2017). The original tool developed by Short et al. (2006) showed acceptable internal consistency reliability and acceptable psychometric properties. The modified version of the PREMIS had 60 items in total and adaptive/branching questioning was used. The survey was delivered over five pages, starting with demographics followed by a screen for each of the four PREMIS sub-scales: preparation, knowledge, opinions and practice Issues. Participants had to provide an answer for each item before being able to move onto the next section of the survey, non-response items were included where necessary. Participants could go back to the previous section to change their answers by clicking the “Previous Page” button at the bottom of the survey screen.

We adapted PREMIS to be relevant to the scope of AHPs. The wording “intimate partner violence” was changed throughout the survey to the broader term “GBV” which incorporates intimate partner violence and sexual violence. Given our hypothesis that AHPs would have limited knowledge in the area, a broader term accounts for all types of violence these health professionals may associate with gendered violence (physical, sexual, psychological, coercion and controlling behaviours). Definitions of the terms GBV, intimate partner violence and sexual violence were added to the beginning of the survey. Based on AHP roles and responsibilities, items deemed irrelevant or out of scope for AHPs were removed from the survey. A detailed summary of changes to the modified PREMIS can be found in the supplementary materials.

When scoring the modified PREMIS we adhered to the instructions on the original survey (Short et al., 2006) and created summary scales to assess four sections of the survey: preparation, knowledge, opinions and practice issues.

Preparation Sub-Scale

The modified preparation sub-scale comprised of 13 items assessing perceived preparedness (four items) and perceived knowledge (nine items). For perceived preparedness, possible scores range from 1 to 7 with 1 indicating the participant felt they were not prepared and 7 indicating they were quite well prepared. For perceived knowledge, possible scores range from 1 to 7 with 1 indicating the participant felt they knew nothing and 7 indicating they knew a substantial amount. Twelve items were removed and two items from the original PREMIS were modified to be relevant for AHPs.

Knowledge Sub-Scale

The modified knowledge sub-scale comprised of 14 items assessing actual GBV knowledge using multiple choice and True/False questions about GBV. Possible scores ranged from 1 to 30 with 30 indicating the participant answered all questions correctly. Four items not relevant for AHPs were removed from the original PREMIS preparation sub-scale.

Opinion Sub-Scale

The opinion sub-scale comprised 24 items assessing the participants’ opinions towards GBV. Opinion items were grouped into categories based on the original PREMIS survey including staff preparation (three items), workplace (three items), self-efficacy (seven items), Alcohol and drugs (two items), victim understanding (five items) and scope (two items). Participants rated items on a scale of one to four from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (4). A score for each opinion category was calculated using the average score of each of the items within that category. Negative opinion items were reverse-coded so that higher scores (closer to four) for each opinion category indicated positive opinions and attitudes. Seven items not relevant for AHPs were removed from the original PREMIS preparation sub-scale. One item was modified and four items were added to the opinions sub-scale.

Practice Issues sub-Scale

The modified practice issues sub-scale comprised of 9 items assessing self-reported behaviours, such as individual and workplace GBV practices. Examples of questions asked included: “How many new diagnoses (picked up an acute case, uncovered ongoing abuse, or had a client disclose a past history) of gender-based violence would you estimate you have identified working as a health professional?” and “Are gender-based violence client education or resource materials (posters, brochures, etc.) available at your practice site?” Four items not relevant for AHPs were removed from the practice issues sub-scale.

Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative data were collected during one-to-one online Zoom interviews. Questions were semi-structured, open-ended and initiated by the researcher. The interview schedule was developed with other members of the research team to gain an in-depth understanding of the participants’ knowledge, attitudes and preparedness with screening and referral for acute crisis help. This included how GBV fits into the AHP scope of practice, any experience with a client disclosure of GBV and how they would respond to a disclosure. Interviews also aimed to understand what participants already knew about the considerations and potential impacts of interventions that support recovery from short- and long-term physical and mental health consequences of GBV. This included the knowledge of the physical and mental health impacts of GBV and confidence supporting a client with a history of GBV. This allowed for an assessment of what AHPs believed they needed and what information they would need to feel confident in supporting the recovery of people who have experienced GBV.

Each interview took approximately 20–30 min to complete. Interviews were conducted by members of the research team who are exercise physiologists. Participants were asked to complete an interview on one occasion. The interviews were recorded and transcribed using the automatic transcription function on Zoom. The automatic transcripts were downloaded onto a Word document and the original Zoom audio was downloaded following interviews. A member of the research team (LW) listened to the original audio and checked the transcripts for accuracy before they were analysed.

Considering the discussion of topics related to GBV, there was a potential for participants to become distressed during interviews. Researchers who conducted the interviews either held a Mental Health First Aid certificate and were able to apply mental health first aid to participants who experienced distress or were experienced in providing psychosocial support. The research team also provided participants with mental health support services (e.g.,: Lifeline) and national sexual assault counselling lines (e.g.,: 1800 RESPECT), relevant to their geographical location.

Data Analysis

Modified PREMIS

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.0 (IBM Corp, 2020). Response options for participant demographics were categorical and reported as the total number of participants (n) and percentage of participants (%). Survey responses were analysed in four major sections: preparation, knowledge, opinions, and practice issues creating scores for each section (Short et al., 2006). Preparation, opinion, and knowledge sub-scales had discrete outcomes and were reported as mean and standard deviation. Preparation and practice issue sub-scales had categorical outcomes and were reported as n and %. Only completed surveys were analysed. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to determine whether there was a significant difference in the perceived preparedness and knowledge between participants who have had some GBV training and participants who have had no GBV training.

Interviews

Content analysis of the qualitative data was completed by two researchers independently (LW and CM). Content analysis is a systematic and objective method used to identify recurring themes within qualitative data (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). LW and CM read through the interview transcripts several times to familiarise themselves with the data. LW and CM then organised the data by completing the following steps 1) open coding which included writing notes and headings within the data 2) creating categories and 3) abstraction which was grouping categories under higher order headings to create interview themes (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

Mixed Methods Analysis

Methodological triangulation of the quantitative and qualitative data was used during answering our research question. Methodological triangulation uses different methodologies to approach the same topic (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012). Key findings from the quantitative data confirmed and validated the themes found in qualitative data (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Triangulation included the presentation of final themes from mixed methods analysis of both the qualitative and quantitative data sources (Noble & Heale, 2019).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant demographics are shown in Table 1. Of the 157 people who opened the survey, two respondents did not meet the inclusion criteria (answered ‘no’ to “are you a tertiary qualified allied health professional”) and 50 did not complete the full survey. Of the 50 participants who opened the survey but did not complete it, 90% (n = 45) stopped during or after the demographics section and did not complete the PREMIS items. We received n = 105 full survey responses (67% completion rate). The median age of respondents was 33.2 (10.6) years and the majority were female (n = 78, 74%). Most of the respondents were currently working in Australia (n = 95, 91%). Most respondents had completed either a Bachelors (n = 41, 39%) or Master’s degree (n = 41, 39%). Exercise physiologists (n = 43, 41%) and physiotherapists (n = 27, 26%) were the most common professional group to complete the survey, with a third of all respondents (n = 33, 31%) working in private practice. Between 30 and 40 h of paid work per week was the most common response selected by the participants (n = 43, 41%).

Table 1.

Survey Participant Demographics.

| Characteristic (N = 105) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <25 | 26(25) |

| 26-40 | 58(55) |

| 41-60 | 19(18) |

| >60 | 2(2) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 78 (74) |

| Male | 27 (26) |

| Non-binary | 0 (0) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 95 (90) |

| Other | 10 (10) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Bachelor's degree | 41 (39) |

| Master’s | 41 (39) |

| Doctorate (including PhD) | 11 (11) |

| Other (e.g.,: honours, diploma and certificate) | 12 (11) |

| Profession | |

| Exercise Physiologist | 43 (41) |

| Physiotherapist | 27 (26) |

| Dietitian | 6 (6) |

| Psychologist | 6 (6) |

| Optometrist | 6 (6) |

| Occupational Therapist | 5 (5) |

| Speech Pathologist | 3 (3) |

| Other | 8 (7) |

| Main area of employment | |

| Private Practice | 33 (31) |

| Hospital | 15 (14) |

| Academic Institution | 11 (11) |

| Allied health clinic | 11 (11) |

| Other (e.g.,: Insurance, team sports) | 35 (33) |

| Paid employment hours per week | |

| >40 | 17 (16) |

| 30–40 | 43 (41) |

| 20–30 | 22 (21) |

| 10–20 | 14 (13) |

| <10 | 9 (9) |

| Years in current occupation | |

| >10 | 29 (27) |

| 5–9 | 24 (23) |

| 1–4 | 26 (25) |

| <1 | 26 (25) |

| Hours of gender-based violence training received | |

| None | 68 (65) |

| < 1 h | 16 (15) |

| > 1 h | 21 (20) |

| Where the training was received (n = 37) | |

| Workplace | 18 (49) |

| University | 5 (14) |

| Other (e.g.,: community-based organisation, online module) | 14 (37) |

Gender-Based Violence Training

Most respondents (n = 68, 65%) had received no formal gender-based violence training, with only 35% of the sample (n = 37) having received formal GBV training. Of those respondents who had received gender-based violence training, the most common training setting was in the workplace (n = 18, 49%), followed by a university (14%), hospital or clinic (11%), in the community or an external organisation (11%). A small proportion had received online GBV training as part of modules or tutorials (8%). The most common areas of employment for AHPs who had received training under private practice (n = 13, 35%) followed by hospitals (n = 6, 16%).

Ten (N = 10) participants participated in qualitative interviews. Participant demographics are shown in Table 2. Most were female (n = 7, 70%), exercise physiologists (n = 4, 40%) or dietitians (n = 3, 30%), with a single physiotherapist (n = 1, 10%), occupational therapist (n = 1, 10%) and health education officer/social worker (n = 1, 10%). No participants experienced distress or required mental health support during or following interviews.

Table 2.

Interview Participant Demographics.

| Characteristic (N = 10) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 7 (70) |

| Male | 3 (30) |

| Non-binary | 0 (0) |

| Profession | |

| Exercise Physiologist | 4 (40) |

| Dietitian | 3 (30) |

| Physiotherapist | 1 (10) |

| Occupational Therapist | 1 (10) |

| Health Education Officer | 1 (10) |

Modified PREMIS Results

Preparation sub-Scale

Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations (SD) for overall participant perceived preparation (Mean (SD): 2.79 (1.32)) (1 = ‘not prepared’ to 7 = ‘quite well prepared’). The mean score was 2.79 which means the participants felt between ‘minimally’ (2) and ‘slightly’ (3) prepared. For perceived knowledge the mean score, was 2.68 (SD 1.22) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = ‘nothing’ to 7 = ‘very much’) indicating the participants felt they knew ‘very little’ (2) and ‘a little’ (3).

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Preparation, Opinion and Knowledge Scales.

| Scale | Mean | Std. deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | ||

| Perceived preparation | 2.79 | 1.32 |

| Perceived knowledge | 2.68 | 1.22 |

| Opinion | ||

| Victim understanding | 3.18 | 0.39 |

| Workplace | 2.62 | 0.56 |

| Allied health scope | 3.21 | 0.55 |

| Staff preparation | 2.06 | 0.63 |

| Self-efficacy | 2.46 | 0.42 |

| Alcohol and drugs | 2.86 | 0.47 |

| Knowledge | ||

| Actual knowledge | 21.99 | 3.66 |

Note. Perceived preparation scale: 1 = ‘not prepared’ to 7 = ‘quite well prepared’. Perceived knowledge scale: 1 = ‘nothing’ to 7 = ‘very much’. Opinion's scale: 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 4 = ‘strongly agree’ (15 items were reverse coded), closer to 4 indicates positive opinions and attitudes. Knowledge scale: mean scores out of 30.

An independent-samples t-test indicated that perceived preparedness scores were significantly higher for participants who had some GBV training (M = 3.60, SD = 1.41) than for participants with no GBV training (M = 2.35, SD = 1.03), t(103) = -5.230, p < .001, d = 1.18.

Table 4 presents frequencies and percentages for participant perceived preparation and knowledge scores. For all four perceived preparation items, 52% of the participants answered ‘not prepared’ or ‘minimally prepared’, with only 3% of the participants perceiving they were ‘quite well prepared’. Across all perceived knowledge items, 79% of participants responded they knew ‘a little’ or less and only 4% of participants responded ‘very much’.

Table 4.

Percentages for Participant Preparation Scores.

| Scale | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Preparation (4 items) | ||

| Not prepared | 17 | |

| Minimally prepared | 35 | |

| Slightly prepared | 23 | |

| Moderately prepared | 12 | |

| Fairly well prepared | 7 | |

| Well prepared | 3 | |

| Quite well prepared | 3 | |

| Total | 100 | |

| Perceived Knowledge (9 items) | ||

| Nothing | 13 | |

| Very little | 39 | |

| A little | 27 | |

| A moderate amount | 10 | |

| A fair amount | 4 | |

| Quite a bit | 3 | |

| Very much | 4 | |

| Total | 100 | |

An independent-samples t-test indicated that perceived knowledge scores were significantly higher for participants who had some GBV training (M = 3.32, SD = 1.42) than for participants with no GBV training (M = 2.34, SD = 0.94), t(103) = -4.242, p < .001, d = 1.13.

Knowledge Sub-Scale

Table 3 presents the mean knowledge score for participants which was 22 (SD 3.66) equating to 73% correct answers. The lowest score was 7 (23%) and the highest score was 28 (93%).

Opinions Sub-Scale

Table 3 presents the mean scores for participants’ opinions and attitudes towards GBV. Tables presenting the frequency and percentage scores for opinion items can be found in the supplementary material.

A majority of participants either ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’ to items “recognising the signs and symptoms of GBV was not part of their job” (n = 91, 87%) and “understanding the impacts of GBV on mental and physical health is not an important part of their role as a health professional” (n = 94, 90%).

Most participants (n = 70, 67%) ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly’ agreed they “could make appropriate referrals to services within the community for GBV victims”. A majority (n = 88, 83%) of participants ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ to “I understand the impact of GBV on physical and mental health”

For the two items “I am able to gather the necessary information to identify GBV as an underlying cause of clients condition”, more participants ‘strongly disagreed’ or ‘disagreed’ when the example conditions used were depression and migraines (n = 67,64%) compared to bruises and fractures (n = 47, 45%).

A majority of participants ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ to items “I do not have sufficient training to assist individuals in addressing situations of GBV” (n = 93, 89%) and “I do not have sufficient training on the impacts of GBV on my clients physical or mental health” (n = 87, 83%).

Most participants ‘strongly disagreed’ or ‘disagreed’ to the items “I feel comfortable discussing GBV with my clients” (n = 73, 70%), “I am capable of identifying GBV without asking my client about it” (n = 78, 74%) and “I can recognise victims of GBV by the way they behave” (n = 78, 74%). For the item “I don't have the necessary skills to discuss abuse with a gender-based violence victim who is: female, male, non-binary and from a different culture/ethnic background” majority of respondents checked female (n = 64, 61%), male (80, 76%), non-binary (80, 76%) and different culture/ethnic background (n = 83, 79%).

Practice Issues Sub-Scale

Half of the participants had never identified GBV (n = 55, 52%) and 9 (9%) participants answered they were not in clinical practice. This left 39% (n = 41) of AHPs in clinical practice who responded they had recognised a case of GBV or had a client disclosure of GBV. Most participants (n = 87, 83%) responded they were not screening for GBV. Most participants (n = 79, 75%) had never asked their clients about the possibility of GBV. The most common health conditions that participants reported asking their clients about the possibility of GBV included injuries (19%), depression and anxiety (18%) and eating disorders (15%). Most participants (n = 80, 76%) answered ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ to having adequate knowledge of GBV referral resources for clients in the community. One-third of the participants said there was no protocol for dealing with GBV at their worksite (n = 34, 32%) or that they were unsure (n = 33, 31%). Half of the participants did not have adequate GBV referral resources at their worksite (n = 53, 51%) and another 24% (n = 25) were unsure.

Interviews

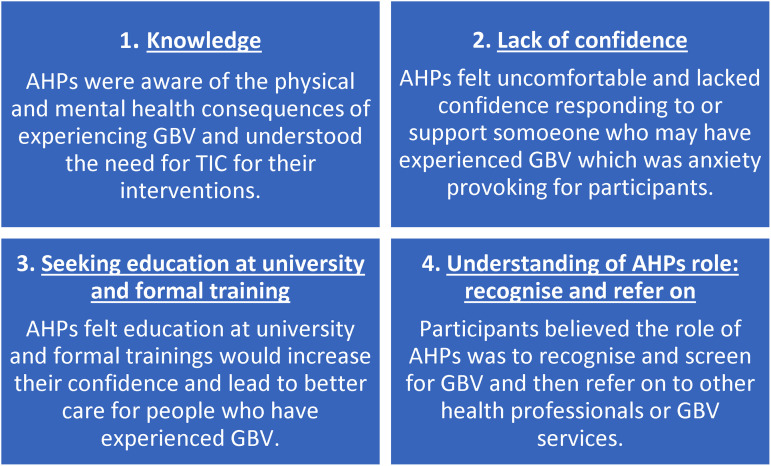

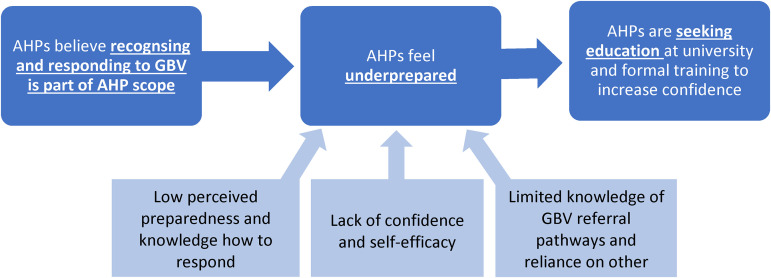

Four themes emerged from interviews: knowledge, lack of confidence, understanding the role of AHPs and seeking education at a university and formal training (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of interview themes and definitions.

Figure 2.

AHP readiness to identify and respond to GBV results from quantitative and qualitative data.

Knowledge

Participants were able to identify components of TIC and identify considerations for the interventions they provide. Participants were aware of the risk of causing harm or potential re-traumatisation if the appropriate considerations were not used during conversations or interventions. Participants understood the importance of autonomy as a key component in their interventions. This included a client-centred approach, the importance of the client having control and collaborative goal setting. Participants identified environmental factors as a consideration for interventions, such as the difference a male or female AHP can make to a client's comfortability and consent prior to physical contact.

“It would just be like whatever they're comfortable with. If they want a male trainer or female trainer, or if there's a specific exercise that they can't do because of an injury or something that for whatever reason triggers them” (P1, exercise physiologist).

Participants felt more confident recognising the physical health consequences of GBV (e.g.,: bruises and injuries) while being aware of mental health consequences (e.g.,: depression, anxiety and eating disorders) but less confident in linking these to an experience of GBV. Participants commonly associated behaviour changes as a sign of GBV including becoming shy or timid, hiding something, looking or acting on-edge and stories that changed.

Lack of Confidence

Participants were not confident in their ability to appropriately respond to GBV due to a perceived lack of knowledge and lack of experience.

I kind of just palmed it off to someone else because I don’t have the experience or the confidence in knowing what to do. (P1, exercise physiologist)

Perceived knowledge was low among participants, especially after completing the survey, participants felt they had little baseline knowledge on GBV.

My main reflection after that [the survey] is, wow I really don't know a lot about this topic. (P2, dietitian)

Most AHPs talked about not knowing what to do or how to a support a client who may have experienced or was experiencing GBV. Participants were not confident to start a conversation or respond to a disclosure of GBV, describing that as uncomfortable or anxiety-inducing for the AHPs. Low confidence was related to a lack of knowledge of GBV-specific referral services in the community. Participants not knowing what to do after a disclosure of GBV was a factor in potentially avoiding a conversation with their client about GBV.

If I was presented with it, it would be very anxiety-provoking. I’d feel very, very uncomfortable talking about it. (P3, exercise physiologist)

Seeking Education at University and Formal Training to Increase Confidence

All participants expressed an interest in undertaking GBV training. Participants expressed they would have liked to receive additional training during their initial training at the university and the opportunity to complete formal GBV training as part of their professional development in the future. Most participants suggested that formal training, along with education at the university, would increase confidence in AHPs practice and ability to support clients who had experienced GBV and lead to better care.

The fact that myself as a clinician doesn't have much experience with being able to respond to that [GBV], was a little bit alarming…I would love to get a bit more training on, for example, if I did have a client that raised this to me, I want to know how to help them the best way that I can. (P10, exercise physiologist)

Formal training would help me to be more confident in recognizing it or even if it wasn't disclosed then how to bring it up. (P1, exercise physiologist)

Lack of education about GBV at the university contributed to the participants’ low confidence in identifying and responding to GBV. The participants were unsure if responding to and managing GBV was part of their scope of practice as an AHP, which further reduced confidence in their ability to support clients who experienced GBV. Participants felt they might be stepping out of their role as an AHP and that they were under-prepared to respond to and support someone with a history of GBV, based on GBV not being included in their university curricula. Participants believed more GBV education in their university curricula would increase confidence in supporting clients who had experienced GBV. Participants who had experience working with trauma populations and knowledge of TIC from their workplace (e.g., community mental health and hospital settings) also mentioned a lack of education about TIC principles at the university.

Based on what we were taught in our degree, there was no indication to me that it's part of our scope. [GBV] Never got mentioned once…If it came up to now, I don't think I’d have the tools and knowledge to deal with it…you don't want to do the wrong thing. (P3, exercise physiologist)

Recognising and screening for GBV was identified by participants as a key gap in the AHPs’ knowledge and skills they wanted to be addressed during GBV training. Participants felt they needed training on “how to bring it up” if they suspected a client may have a history of GBV. This linked to participants wanting training on and recognising the importance of “having uncomfortable conversations”. Another knowledge gap identified was the steps to take to support someone following the identification of GBV or client disclosure. Participants often brought up that they were unsure “what to do next”. Participants wanted GBV training that would increase their knowledge of available GBV referral services and resources. Participants expressed the importance of GBV training being occupation-specific to the allied health profession and their intervention driven diversity and variation across allied health professions (e.g.,: dietetic intervention versus an exercise-based intervention).

Understanding of the Role of AHPs: Recognise and Refer on

Participants believed their scope of practice included recognising physical and mental health consequences of experiencing GBV and being able to refer on for GBV-specific support. Participants felt they had a duty of care to facilitate a conversation and provide validation and reassurance if a client disclosed GBV or the AHP suspected GBV.

I think it is definitely a conversation that we can't just avoid, if we suspect there's warning signs, we should be trying to address that. (P4, exercise physiologist)

Participants recognised GBV as a health issue, and believed their scope involved addressing not only the physical health conditions people present with but understanding the impact of mental health on people's physical health.

AHPs relied on being able to refer a client if they recognised or had a disclosure of GBV. All AHPs valued a team around them where they could discuss and refer clients when needed.

As any health care professional, I think we've got some role in screening for any type of violence, or you know, abuse that might be happening. I would say it's probably more so within my scope to flag it to other team members…I definitely think it's within my scope to kind of raise that issue, or if someone does disclose information to maybe explore a little bit further, and then take it higher. (P2, dietitian)

Participants lacked the knowledge of available GBV services. Who AHPs would refer the client to was heavily influenced by their workplace. AHPs working in multidisciplinary environments had greater support and opportunity for support compared to private practitioners.

No, because if I was in private practice, to be honest, I probably wouldn't really know what to do…like I wouldn't know in their community any of those people [case manager, social workers etc.]. (P1, exercise physiologist)

Mixed Methods Analysis

Overall results showed AHPs believed being able to recognise the health consequences of experiencing GBV and responding to and supporting someone who has experienced GBV is part of the AHP scope. A summary of these findings is shown in Figure 2. Low perceived preparedness and knowledge and self-efficacy scores seen in PREMIS were confirmed in interviews by the participants expressing a lack of confidence to respond to and support people who have experienced GBV. AHPs were unaware of GBV services within the community and recognised this as a gap in knowledge as well as valued and relied on a multidisciplinary team where they could refer onto other health professionals. The PREMIS results showed AHPs felt they did not receive sufficient training and all interview participants said that education at the university and formal training would increase AHPs’ confidence to identify and respond to GBV.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the readiness of exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and other AHPs to respond to a person who has experienced GBV. We found evidence that AHPs felt underprepared, had low perceived knowledge and lacked confidence to respond to and support people who have experienced GBV, despite recognition of the importance and agreement of the relevance to practice of AHPs. AHPs scored well in GBV knowledge and victim understanding, as well as had an understanding that trauma impacts physical and mental health and were able to identify considerations for trauma-informed practices. AHPs identified that education at the university and formal GBV training would increase confidence in identifying and responding to GBV. AHPs believe they need to be aware of physical and mental health consequences of GBV, being able to recognise signs, respond appropriately to disclosures and refer to other health professionals to effectively respond to GBV or GBV-specific support.

No previous studies have focused on the readiness of exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and other AHPs to identify and respond to GBV. Our findings are consistent with existing evidence assessing the readiness of health professionals (medical, nursing and allied health) to respond to GBV (Fisher et al., 2020; Renner et al., 2019; Withiel et al., 2021). AHPs are well placed to recognise GBV and refer to specific GBV services that support recovery (McLindon et al., 2021; Sawyer et al., 2016). Results from this study showed AHPs agreed they should play a role in recognising and responding to GBV.

Our results showed that 80% of AHPs who completed the PREMIS survey had received none or less than one hour of GBV training. When compared to other health professionals, AHPs have the lowest levels of training and report the lowest levels of knowledge and preparedness to respond to GBV (Fisher et al., 2020; Hughes et al., 2022; Withiel et al., 2021). However, studies show social workers score higher in preparedness and knowledge than other allied health professions and medical and nursing professions due to their scope of practice (McLindon et al., 2021; Renner et al., 2019; Withiel et al., 2021). Despite most of our samples being exercise physiologists and physiotherapists, a large proportion of respondents who are currently in clinical practice (n = 41, 39%) have recognised a case of GBV or had a client disclosure of GBV, indicating the need for training for all AHPs.

Our results are consistent with the previous literature that the lack of confidence and poor self-efficacy due to low perceived knowledge and preparedness is a common barrier for all types of health professionals’ (e.g.,: medical, nursing and allied health) readiness to manage GBV (Fisher et al., 2020; McLindon et al., 2021; Renner et al., 2019; Sawyer et al., 2017; Walton et al., 2015; Withiel et al., 2021). Findings from this study show AHPs are not aware of specific GBV referral services within the community and valued a team where they could refer to another health professional if someone disclosed or they suspected GBV. AHPs reliance on referring to other health professionals is consistent with a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies where health practitioners’ readiness to respond to GBV was enhanced by collaborating with a team for support and health professionals with specialist knowledge (Hegarty et al., 2020).

Participants felt GBV education at the university and professional training would increase the AHPs’ confidence and readiness to respond to and support people who have experienced GBV. PREMIS results showed perceived preparedness and knowledge scores were significantly higher for participants who had received some GBV training compared to participants who had received none. There is a strong link between education and improved GBV knowledge, attitudes, readiness and clinical skill (McLindon et al., 2021). University and workplace training is critical for health professionals to develop the necessary skills to safely and effectively support the recovery of someone who has experienced GBV (McLindon et al., 2021). A Cochrane review on training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence concluded that training may be effective for outcomes that are precursors to behavioural change; however, the evidence is weak for training to improve attitudes, knowledge, self-perceived readiness and actual responses (Kalra et al., 2021).

A potential barrier for the effectiveness of GBV training are structural factors which make people feel uncomfortable talking about GBV, for example societal attitudes towards gender and harmful gender norms. One study found that another barrier for healthcare students to accepting GBV education into their curriculum is its reputation as a ‘taboo’ subject (Sammut et al., 2022). These structural factors serve to maintain the silence about GBV reducing healthcare professionals’ ability to respond to and support people who have experienced GBV.

Occupation-specific training and research is important for skill development relevant to a specific role (Sawyer et al., 2016). Based on the results from this study, GBV education and training needs to include AHPs’ role and responsibility when responding to and supporting people who have experienced GBV, the signs and symptoms of GBV, practical skills to improve the AHPs’ confidence to ask about or respond to a disclosure of GBV as well as TIC principles to support the recovery from the physical and mental health consequences of GBV.

Context-specific ethical considerations, for example, survivor/victim confidentiality, and understanding of local laws and reporting policies and procedures need to also be considered when developing training for AHPs.

There is a wide range of research and resources available to inform GBV education and training, including the WHO ‘LIVES’ model of first-line GBV support and The CATCH model (Hegarty et al., 2020; McLindon et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2013; World Health Organization, 2019). Addressing and using TIC as a framework for responding to GBV is also important to consider when designing and delivering GBV education and training (McLindon et al., 2021).

Ambikile et al. (2021) presented curricular limitations and recommendations for training healthcare professionals to respond to intimate partner violence which should be considered for potential AHP education and training. Key points include dedicating more time and ensuring the inclusion of intimate partner violence content in university curricula, improving teaching and learning strategies, the importance of institutional endorsement for intimate partner violence response content and the need for more funding to support the implementation of intimate partner violence response training in curricula (Ambikile et al., 2021).

Limitations of This Study

Methodological limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting these data. This includes the cross-sectional design. A strength of the study was the mixed methods approach, which allowed for conclusions drawn from quantitative data to be confirmed and strengthened by quantitative data. A limitation included the inability to determine the representativeness of the sample due to recruitment being through social media pages of relevant AHP organisational bodies. This recruitment strategy may have produced a likely biased sample of AHPs who are more interested and potentially more knowledgeable in the area. The psychometric properties and validity of the modified PREMIS are unknown and future research should consider the reliability of individual items and the overall scale. Member checking was not completed with qualitative data which may reduce data credibility. This study did not include representative samples of social workers, psychologists and other AHPs who may score differently to exercise physiologists and physiotherapists who were the majority in this study. A limitation of the triangulation analysis was the small sample size of interview participants (n = 10) in comparison with the larger sample who completed the PREMIS survey (n = 105). Triangulation analysis focused on themes explored in the small sample of interview participants also found in the survey and therefore may not be representative of the views of those surveyed.

A limitation of the paper is that the participants were not asked whether they had personally experienced GBV which may have influenced the participants’ responses. For example, own experiences of GBV may increase the AHPs’ preparedness and confidence to identify and respond to GBV (Dheensa et al., 2023). Future research could consider asking about how the participants’ personal experiences impact their knowledge and confidence to respond.

Conclusion

Exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and other AHPs may feel underprepared, have low perceived knowledge and lack the confidence to respond to or support people who have experienced GBV. Increasing AHPs confidence to identify and respond to GBV through dedicated training programs is warranted and urgently needed. Future research should focus on how to develop GBV education that is relevant to AHPs scope and unique role in responding to GBV and its health consequences.

Reflexivity Statement

The research team represent a range of allied health professions including exercise physiologists, a dietitian and a psychologist. The authors acknowledge the potential for their own social biases to influence the research process. Both LW (first author) and GM (senior author) are exercise physiologists and researchers in the field of mental health. They have not received training in GBV during their allied health degrees. The first authors’ (LW) position as a white, cis-gendered, straight, non-disabled female adds the potential for bias to the research, including the authors’ own privilege and values. This is particularly important to acknowledge in GBV research considering the differing experiences of diverse populations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-vaw-10.1177_10778012241257245 for Readiness of Exercise Physiologists, Physiotherapists and Other Allied Health Professionals to Respond to Gender-Based Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study by Lauren Wheatley, Simon Rosenbaum, Chiara Mastrogiovanni, Michelle Pebole, Ruth Wells, Susan Rees, Scott Teasdale and Grace McKeon in Violence Against Women

Author Biographies

Lauren Wheatley is an exercise physiologist with a Master's in research in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Chiara Mastrogiovanni is a PhD candidate and an exercise physiologist in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Grace McKeon is a postdoctoral research fellow and exercise physiologist in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health and the School of Population Health at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Michelle M Pebole, PhD, MA is an advanced postdoctoral fellow in polytrauma at the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS) at the Boston Veteran's Affairs Healthcare System and Harvard University. Her research focuses on developing and implementing physical activity programs to improve physical and mental health outcomes among individuals who have experienced violence and trauma.

Ruth Wells is a senior research fellow in the Trauma and Mental Health Unit, School of Psychiatry, UNSW Sydney, and a Registered Psychologist.

Susan Rees is a full-time professor in psychiatry with a public health and social science background in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Scott Teasdale is an accredited practising dietitian and senior research fellow in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health at UNSW Sydney and Mindgardens Neuroscience Network in Sydney NSW, Australia. Dr Teasdale's research focuses on the role nutrition can play for people with mental health challenges.

Simon Rosenbaum is Scientia Associate Professor, academic exercise physiologist and NHMRC EL Fellow in the Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Health and Behavior International Collaborative Research Award and the Society of Behavioural Medicine awarded to Michelle M Pebole, PhD.

ORCID iDs: Lauren Wheatley https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5768-4613

Chiara Mastrogiovanni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5197-6412

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Correction (June 2024): This article has been updated with changes in Table 4 since its original publication.

References

- Academy Quality Management C. (2018). Academy of nutrition and dietetics: Revised 2017 scope of practice for the registered dietitian nutritionist. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 118(1), 141–165. 10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allied Health Professions Australia (2022). What is allied health? Retrieved from https://ahpa.com.au/what-is-allied-health/.

- Ambikile J. S., Leshabari S., Ohnishi M. (2021). Curricular limitations and recommendations for training health care providers to respond to intimate partner violence: An integrative literature review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1262–1269. 10.1177/1524838021995951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2021). Allied health in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/allied-health/in-australia.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019). Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019.

- Bateman J., Henderson C., Kezelman C. (2013). Mental Health Coordinating Council (MHCC) 2013, Trauma-Informed Care and Practice: Towards a cultural shift in policy reform across mental health and human services in Australia, A National Strategic Direction, Position Paper and Recommendations of the National Trauma-Informed Care and Practice Advisory Working Group. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet A., Zauszniewski J. (2012). Methodological triangulation: An approach to understanding data. Nurse Researcher (Through 2013), 20(2), 40–43. https://login.wwwproxy1.library.unsw.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/methodological-triangulation-approach/docview/1325690432/se-2. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2012.11.20.2.40.c9442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman F., Ekblom Ö. (2022). Physical exercise as treatment for PTSD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Military Medicine, 187(9-10), e1103–e1113. 10.1093/milmed/usab497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A. E., Anderson M. L., Rivara F. P., Thompson R. S. (2009). Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research, 44(3), 1052–1067. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandan J. S., Thomas T., Bradbury-Jones C., Taylor J., Bandyopadhyay S., Nirantharakumar K. (2020). Risk of cardiometabolic disease and all-cause mortality in female survivors of domestic abuse. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(4), e014580. 10.1161/jaha.119.014580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C. H., Cattoi A. L., McCall-Hosenfeld J. S., Camacho F., Dyer A. M., Weisman C. S. (2012). Longitudinal association of intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 9(2), 107–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concepcion R. Y., Ebbeck V. (2005). Examining the physical activity experiences of survivors of domestic violence in relation to self-views. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 27(2), 197–211. 10.1123/jsep.27.2.197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Miller D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dheensa S., McLindon E., Spencer C., Pereira S., Shrestha S., Emsley E., Gregory A. (2023). Healthcare Professionals’ own experiences of domestic violence and abuse: A meta-analysis of prevalence and systematic review of risk markers and consequences. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1282–1299. 10.1177/15248380211061771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon G., Hussain R., Loxton D., Rahman S. (2013). Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2013, 1–15. 10.1155/2013/313909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. (2004). Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(3), e34. 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J., Solmi M., Wootton R. E., Vancampfort D., Schuch F. B., Hoare E., Stubbs B. (2020). A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: The role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 360–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. A., Rudkin N., Withiel T. D., May A., Barson E., Allen B., Willis K. (2020). Assisting patients experiencing family violence: A survey of training levels, perceived knowledge, and confidence of clinical staff in a large metropolitan hospital. Women's Health, 16, 174550652092605. 10.1177/1745506520926051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Hegarty K., d'Oliveira A. F. L., Koziol-McLain J., Colombini M., Feder G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A., Taylor R., Minor B. L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., Duda S. N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K., McKibbin G., Hameed M., Koziol-McLain J., Feder G., Tarzia L., Hooker L. (2020). Health practitioners’ readiness to address domestic violence and abuse: A qualitative meta-synthesis. PLOS ONE, 15(6), e0234067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K. L., Andrews S., Tarzia L. (2022). Transforming health settings to address gender-based violence in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 217(3), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissel A., Heinen D., Brokmeier L. L., Skarabis N., Kangas M., Vancampfort D., Schuch F. (2023). Exercise as medicine for depressive symptoms? A systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A., Bourne A., McNair R., Carman M., Lyons A. (2020). Private Lives 3: The health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people in Australia.

- Hughes C. M. L., Southard R., Walsh L., Gordon-Murer C., Hintze A., Musselman E. (2022). Intimate partner violence knowledge and preparation: Perspective of health care profession students. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 36(2), 163–170. 10.1097/jte.0000000000000229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. [Google Scholar]

- Jacka F. N., O'Neil A., Opie R., Itsiopoulos C., Cotton S., Mohebbi M., Berk M. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Medicine, 15(1), 23. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski K. P., Murray V., Stokes N., Thurston R. C. (2021). Sexual violence and cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 153, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra N., Hooker L., Reisenhofer S., Di Tanna G. L., García-Moreno C. (2021). Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(5). 10.1002/14651858.CD012423.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassale C., Batty G. D., Baghdadli A., Jacka F., Sánchez-Villegas A., Kivimäki M., Akbaraly T. (2019). Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(7), 965–986. 10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton D., Schofield M., Hussain R., Mishra G. (2006). History of domestic violence and physical health in midlife. Violence Against Women, 12(8), 715–731. 10.1177/1077801206291483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum On M., Ayre J., Webster K., Moon L. (2016). Examination of the health outcomes of intimate partner violence against women : State of knowledge paper. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS). 10.1111/1753-6405.13301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mburia-Mwalili A., Clements-Nolle K., Lee W., Shadley M., Wei Y. (2010). Intimate partner violence and depression in a population-based sample of women: Can social support help? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(12), 2258–2278. 10.1177/0886260509354879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLindon E., Fiolet R., Hegarty K. (2021). Is gender-based violence a neglected area of education and training? An analysis of current developments and future directions. In Bradbury-Jones C., Isham L. (Eds.), Understanding gender-based violence: An essential textbook for nurses, healthcare professionals and social workers (pp. 15–30). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Noble H., Heale R. (2019). Triangulation in research, with examples. Evidence Based Nursing, 22, 67–68. 10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Cathain A., Murphy E., Nicholl J. (2007). Why, and how, mixed methods research is undertaken in health services research in England: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 85. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey N., Reay R. E., Aplin V., Cubis J. C., McAndrew V., Riordan D. M., Raphael B. (2019). Achieving service change through the implementation of a trauma-informed care training program within a mental health service. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(3), 467–475. 10.1007/s10597-018-0272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebole M., Gobin R. L., Hall K. S. (2020). Trauma-informed exercise for women survivors of sexual violence. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(2), 686–691. 10.1093/tbm/ibaa043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebole M., Hall K., Gobin R. (2021). Physical activity to address multimorbidity among survivors of sexual violence: A comprehensive narrative review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pill N., Day A., Mildred H. (2017). Trauma responses to intimate partner violence: A review of current knowledge. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.014 [Google Scholar]

- Quadara A. (2015). Implementing trauma-informed systems of care in health settings: The WITH study: State of knowledge paper (ANROWS Landscapes, 10/2015). ANROWS. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S., Silove D., Chey T., Ivancic L., Steel Z., Creamer M., Forbes D. (2011). Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. JAMA, 306(5), 513–521. 10.1001/jama.2011.1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S., Steel Z., Creamer M., Teesson M., Bryant R., McFarlane A. C., Silove D. (2014). Onset of common mental disorders and suicidal behavior following women's first exposure to gender based violence: A retrospective, population-based study. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 312. 10.1186/s12888-014-0312-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner L. M., Wang Q., Logeais M. E., Clark C. J. (2019). Health care Providers’ readiness to identify and respond to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19-20), 9507–9534. 10.1177/0886260519867705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboori Z., Gold R. S., Green K. M., Wang M. Q. (2021). Community health worker knowledge, attitudes, practices and readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Journal of Community Health, 47, 17–27. 10.1007/s10900-021-01012-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammut D., Ferrer L., Gorham E., Hegarty K., Kuruppu J., Salvo F. L., Bradbury-Jones C. (2022). Healthcare Students’ and Educators’ views on the integration of gender-based violence education into the curriculum: A qualitative inquiry in three countries. Journal of Family Violence, 38, 1469–1481. 10.1007/s10896-022-00441-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S., Coles J., Williams A., Lucas P., Williams B. (2017). Paramedic Students’ knowledge, attitudes, and preparedness to manage intimate partner violence patients. Prehospital Emergency Care, 21(6), 750–760. 10.1080/10903127.2017.1332125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S., Coles J., Williams A., Williams B. (2016). A systematic review of intimate partner violence educational interventions delivered to allied health care practitioners. Medical Education, 50(11), 1107–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard-Perkins M. D., Malcolm S. K., Hira S. K., Smith S. V., Darroch F. E. (2022). Exploring moderate to vigorous physical activity for women with post-traumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 23, 100474. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2022.100474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Short L. M., Alpert E., Harris J. M., Surprenant Z. J. (2006). A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(2), 173–180.e19. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs A., Szoeke C. (2021). The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health-related behaviors of women: A systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1157–1172. 10.1177/1524838020985541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. (2022). Violence against women and girls – what the data tell us. Retrieved from https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/overview-of-gender-based-violence/.

- Van de Kamp M. M., Scheffers M., Emck C., Fokker T. J., Hatzmann J., Cuijpers P., Beek P. J. (2023). Body-and movement-oriented interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 36(5), 835–848. 10.1002/jts.22968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton L. M., Aerts F., Burkhart H., Terry T. (2015). Intimate Partner Violence Screening and Implications for Health Care Providers. Online Journal of Health Ethics, 11. 10.18785/ojhe.1101.05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster K. (2016). A preventable burden: Measuring and addressing the prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence in Australian women (ANROWS Compass, 07/2016). ANROWS. [Google Scholar]

- Withiel T. D., Gill H., Fisher C. A. (2021). Responding to family violence: Variations in knowledge, confidence and skills across clinical professions in a large tertiary public hospital. SAGE Open Medicine, 9, 205031212110009. 10.1177/20503121211000923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2018). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Caring for women subjected to violence: a WHO curriculum for training health-care providers. 2019.

- Xu Y., Olfson M., Villegas L., Okuda M., Wang S., Liu S.-M., Blanco C. (2013). A characterization of adult victims of sexual violence: Results from the national epidemiological survey for alcohol and related conditions. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 76(3), 223–240. 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.3.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow H. M., Resnick H. S., McCauley J. L., Amstadter A. B., Ruggiero K. J., Kilpatrick D. G. (2012). Prevalence and risk of psychiatric disorders as a function of variant rape histories: Results from a national survey of women. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(6), 893–902. 10.1007/s00127-011-0397-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-vaw-10.1177_10778012241257245 for Readiness of Exercise Physiologists, Physiotherapists and Other Allied Health Professionals to Respond to Gender-Based Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study by Lauren Wheatley, Simon Rosenbaum, Chiara Mastrogiovanni, Michelle Pebole, Ruth Wells, Susan Rees, Scott Teasdale and Grace McKeon in Violence Against Women