Abstract

Goal-directed behavior often requires concatenating different actions to achieve a goal. The neural correlates of such multi-component behavior have extensively been investigated. However, it is still enigmatic whether it is possible to predict, using single-trial EEG data and on a single-subject level, that an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on multi-component behavior. This study gathered data from N = 239 individuals and applied EEG-based deep learning combined with explainable artificial intelligence, temporal EEG signal decomposition, and source localization.

We show that attentional selection and sensory integration processes in sensory association cortices were highly predictive with ∼86%. Processes specifying rule-based response selection and translation, associated with superior and posterior parietal cortices, were also predictive with ∼70%. This, however, was only possible when the information about sensory integration was not available for deep learning. Therefore, sensory integration processes are particularly important in the decoding of whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on response selection capacity limited multi-component behavior. The results provide insights into the relative importance of various cognitive processes during complex goal-directed behavior and suggest that attentional processes are important to consider during multi-component behavior.

Keywords: Response selection, Attention, EEG, Deep learning

1. Introduction

Goal-directed behavior is central to our daily life and often requires concatenating different actions to achieve a goal. The neural processes associated with this multi-component behavior (Duncan, 2010), also referred to as ‘action cascading,’ have extensively been investigated in recent years in humans (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Gohil et al., 2016a; Mückschel et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2014) and animals (Rook et al., 2020). Multi-component behavior describes the ability to generate, process, and execute different task goals and responses in an expedient temporal order to enable efficient goal-directed behavior (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Duncan, 2010; Mückschel et al., 2015; 2014; Stock et al., 2014; van Thriel et al., 2017). Experimentally, these processes have often been examined using tasks in which an ongoing response has to be interrupted (stopped) in favor of another affordance requiring a different response (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Gohil et al., 2016a; Mückschel et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2014). Demands on these processes depend on the coincidence of stimuli signaling to stop and change a response (Verbruggen et al., 2008). When STOP and CHANGE stimuli are presented simultaneously (i.e., the stop-change delay (SCD) is zero), participants can choose to stop and then change or try to process both action plans in parallel. Compared to a condition imposing a temporal sequence of stopping and changing processes, and in which the change process is signaled at a time point where the stop process has been finished (e.g., an SCD of 300 ms), performance is less efficient when stop and change processes are signaled simultaneously. This can well be explained by response selection capacity limitations (Verbruggen et al., 2008). Even though the neural processes underlying multi-component behavior have extensively been investigated, the question is still whether neurophysiological processes can be decoded to predict whether an individual is confronted with high or low demands on multi-component behavior in a given moment? The even more important question is which cognitive processes, as reflected by neurophysiology on a single-trial and single-subject level, are most important for that?

To answer these questions, EEG-based deep learning methods are suitable because the single-trial neurophysiological activity is noisy (Bridwell et al., 2018). Moreover, there are complex non-linear interdependencies in the time course of relevant neural correlates of cognitive processes involved in goal-directed behavior (Bridwell et al., 2018; Saxe et al., 2021; Vahid et al., 2020, 2019). EEG-based deep learning can capture this complexity and provide insights meaningful for cognitive neuroscience if methods of explainable artificial intelligence are used, i.e., “saliency map” approaches (Ancona et al., 2017; Simonyan et al., 2014). Using saliency approaches, one can delineate which time points and EEG electrode sites contribute most to classification accuracy (Borra et al., 2021; Farahat et al., 2019; Vahid et al., 2020, 2019). This is important for interpreting the results since the literature on the cognitive processes reflected by EEG signatures (event-related potentials, ERPs) is based on the time point, the polarity, and the electrode site (Luck and Kappenman, 2013). When combined with EEG source localization methods, one can then delineate the functional neuroanatomical aspects of the question at hand. Finally, EEG-based deep learning methods have other advantages over classical EPR analysis. The main assumption in classical ERP analysis is that the principal neurophysiological features are the peaks of EEG signals in predefined time windows and electrode sites. Other cognitive features may exist outside of these components, which are not taken into account by the traditional analysis (Vahid et al., 2018). Deep learning, on the other hand, employs all of the dataset's features, and the model learns significant features on its own (LeCun et al., 2015).

Considering the current literature on multi-component behavior, as measured using the mentioned stop-change task, two possible scenarios on the importance of cognitive-neurophysiological processes underlying multi-component behavior are conceivable:

Regarding the first scenario, studies revealed that sensory integration or attentional selection processes are modulated during multi-component behavior (Mückschel et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2017). This is reasonable since attentional limitations can affect performance in situations imposing high demands on response selection capacities (Lien et al., 2006; Pashler, 1998). Moreover, there are shared cortical bottlenecks for attentional and response selection capacity limitations (Marti et al., 2012). Varying the complexity of multi-component behavior in experiments modulates the amplitude and latency of the P1 and N1 ERP components. These ERP components have been suggested to reflect sensory integration and attentional processing (Fu et al., 2001; Giard and Peronnet, 1999; Luck and Kappenman, 2013; Molholm et al., 2004; 2002; Murray et al., 2005). Attentional selection and gating processes are intensified in situations imposing high demands on multi-component behavior (Mückschel et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2017), and the relevance of these processes during multi-component behavior is supported by studies varying the modality of the CHANGE stimulus (Gohil et al., 2015), studies in clinical groups (Brandt et al., 2017; Gohil et al., 2016b), and neurobiochemical data (Yildiz et al., 2014). Especially in individuals with high ability to perform multi-component behavior, sensory integration processes are critical (Yildiz et al., 2014). Based on these findings, activity in the P1/N1 time window may be most informative to predict whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing higher or lower demands on action cascading and multi-component behavior.

Considering the second scenario, studies showed that variations of the stop-change delay (SCD) modulate the amplitude of the P3 ERP-component (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Mückschel et al., 2014). The P3 component is larger when stopping and changing processes are signaled simultaneously, compared to a condition where stopping is finished before the change stimulus is presented (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Mückschel et al., 2014). This modulation may reflect processes of response selection capacity limitations, which is supported by studies showing that the P3 reflects processes at the (strategic) response selection bottleneck (Brisson and Jolicoeur, 2007; Sigman and Dehaene, 2008) and that a larger P3 indicates less efficient processing of “stop goals” and “change goals” (Beste et al., 2014). The P3 possibly reflects response inhibition (stopping) and change processes. When these processes are signaled simultaneously, the strategic response selection bottleneck becomes particularly taxed (Verbruggen et al., 2008). Such increased demands on inhibitory control processes are reflected by an enlarged P3 (Huster et al., 2013). Results from source localization revealed that the medial frontal cortex and parietal areas, including the temporo-parietal junction, are associated with these processes (Mückschel et al., 2014; Stock et al., 2014). Based on these findings, activity in the P3 time window associated with medial frontal and/or inferior parietal areas may be most informative to predict whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing higher or lower demands on action cascading and multi-component behavior.

However, with regard to the possible scenarios outlined above, it is, crucial to consider that the EEG signal reflects a mixture of activity from different anatomical sources (Huster et al., 2015; Nunez et al., 1997; Ouyang and Zhou, 2020). Moreover, data shows that attention and response selection related information is concomitantly coded in the neurophysiological signal during cognitive control (Folstein and Van Petten, 2008; Mückschel et al., 2017; Takacs et al., 2020b). This is particularly the case for processes reflected by the P3 ERP component. This ERP component may reflect processes of mapping stimuli on the appropriate response (Verleger et al., 2005, 2014; Ouyang et al., 2017) and also stimulus-driven working memory updating (Polich, 2007). Therefore, we also perform EEG-based deep learning using decomposed EEG data, i.e., after applying residue iteration decomposition (RIDE) (Ouyang et al., 2015). Even though this method was developed to correct intra-individual variability in the EEG signal across trials (Ouyang et al., 2015), it can also dissociate concomitantly coded attentional selection and response selection-related information in neurophysiological data (Chmielewski et al., 2018; Mückschel et al., 2017; Takacs et al., 2020b). RIDE yields three clusters of activity with dissociable functional significance (Ouyang et al., 2015): The S-cluster is supposed to reflect stimulus-driven attentional selection processes, the R-cluster is supposed to reflect motor execution processes. The third cluster, the C-cluster, likely reflects stimulus-response translation processes (Ouyang et al., 2017) and thus processes similar to the P3 ERP-component (Verleger et al., 2014).

Together with the non-decomposed EEG data, the RIDE-decomposed EEG data will provide valuable information on the relevance of sensory integration/attentional selection vs. response selection processes in predicting whether this individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on multi-component behavior in a given moment: If neurophysiological correlates of sensory integration are most important (scenario 1), the P1/N1 time window in non-decomposed EEG data and the S-cluster should yield comparably high predictions. However, if neurophysiological correlates of response selection are most informative (scenario 2), the P3 in non-decomposed EEG data and the C-cluster should yield comparably high predictions. A pattern of results in which conclusive evidence based on non-decomposed and decomposed EEG data is only available for one of the two scenarios, and evidence supporting the other scenario is only based on non-decomposed or decomposed data, would speak for a hierarchy in the relevance of the identified processes for multi-component behavior.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Data from a sample of N = 239 healthy individuals between 18 and 34 (mean 23.9) years of age (120 females) were used in the study. The data were pooled from previous smaller studies. All participants were free of any medication and did not report a history of neurological diseases or psychiatric disorders. Medical history was assessed via a telephone screening. After all study procedures were explained, all individuals provided written informed consent before participating in the study. The study was approved by a decision from the IRBs of the University of Bochum and TU Dresden. All participants were reimbursed for their participation and treated according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Task

The stop-change paradigm, modified from its original version by Verbruggen et al. (2008), is identical to previous studies by our group (Mückschel et al., 2014) and is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the stop-change paradigm. GO trials end with the first response given. Stop-change (SC) trials require stopping of the GO response as soon as the STOP signal is presented. The CHANGE signal is presented with a stop-change delay (SCD) i.e. stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) of either 0 ms or 300 ms relative to the STOP signal. The CHANGE indicates a change in reference line. SC trials end after any response to the CHANGE stimulus.

In every trial, a white-framed box (20*96 mm) was presented in the center of a 20-inch CRT screen. Within this frame, four white circles (8 mm diameter) were presented (arranged vertically). Three horizontal white lines separated the four circles. These three white lines create the impression of different segments in the frame. The frame, including all circles and lines between the circles, remained on the screen for the entire experiment. In every trial, a GO stimulus was presented on the screen (250 ms after the beginning of the trial). To present the GO stimulus, one of the circles was filled white. The task was to indicate (via button press) whether this filled circle was located above or below the central horizontal line. When the circle was presented above the midline, a response with the right middle finger was required. When the circle was presented below the midline, a response with the right index finger was required. In GO trials (67% of all), the circles remained visible until the participant responded. However, individuals were asked to respond as fast as possible and in no longer than 1000 ms. If a response exceeded this deadline, the German word “Schneller!” (translating to “Faster! ") was presented above the box. The remaining 33% of trials were stop-change (SC) trials. These trials started as a normal GO condition (i.e., a white circle above or below the middle line was presented). Importantly, after a variable” stop-signal delay” (SSD), a STOP stimulus (signal) was presented. To present the STOP stimulus, the white rectangular frame surrounding all circles turned red. Individuals were required to interrupt (stop) the already initiated response on the GO stimulus upon presenting the STOP stimulus. The STOP signal remained on the screen until the end of the trial. The SSD was adjusted using a staircase procedure (Verbruggen et al., 2019, 2008). For the staircase procedure, the initial SSD was set to 250 ms and adapted depending on the participant's ability to stop the GO response. The staircase procedure ensured a 50% probability of a successful stopping of the GO response. Importantly, a CHANGE stimulus was also presented in every trial in which a STOP stimulus was shown. The CHANGE stimulus was a 100 ms sine tone presented via headphones at 75 dB SPL and could be either high (1300 Hz), medium (900 Hz), or low (500 Hz) in pitch. The different pitches referred to one of the three horizontal lines within the rectangle surrounding the circles. This CHANGE stimulus assigned a new reference line concerning the reference line used to determine the correct response on the GO stimulus. The high pitch indicated that the line positioned at the top of the rectangle served as the new reference line. The middle pitch referred to the middle line, and the low pitch indicated the lowest line in the rectangle. All three reference lines were in effect equally often. The CHANGE response required button presses with left-hand fingers. If the target circle (i.e., the former GO stimulus) was located above the newly (tone pitch-assigned) reference line, a response with the left middle finger was required. If the target circle (i.e., the former GO stimulus) was located below the newly assigned reference line, a response with the left index finger was required. To vary demands on multi-component behavior (i.e., the cascade to stop and change the response), the stop-change delay (SCD) was varied in two steps. In the SCD0 condition, the STOP and the CHANGE stimulus occurred simultaneously. In the SCD300 condition, the CHANGE stimulus occurred with a stimulus onset asynchrony of 300 ms. In the SCD300 condition, the CHANGE process is thus signaled after the STOP process has finished (see stop-signal reaction time data in the results section corroborating this).

In 50% of STOP-CHANGE trials, the SCD0 interval was presented; in the other 50% of STOP-CHANGE trials, the SCD300 condition was presented. Whenever responses on the CHANGE stimulus took longer than 2000 ms, the German word “Schneller!” (translating to “Faster! ") was presented above the box. After each stop-change trial, the staircase algorithm adjusted the SSD to be used in the subsequent stop-change trial. In case of an entirely correct stop-change trial (i.e., no response to the GO stimulus, no response before the onset of the CHANGE stimulus and a correct response to the CHANGE stimulus), the SSD was adjusted by adding 50 ms to the SSD of the evaluated trial. In case of an erroneous SC trial (if any of the above criteria were not met), the SSD was adjusted by subtracting 50 ms from the SSD of the evaluated trial. It was ensured that SSD values were not below 50 ms and not above 1000 ms. The trials in the experiment were separated by a fixed duration inter-trial interval of 900 ms. All conditions were presented in pseudorandomized order. The experiment consisted of 864 trials.

2.3. EEG recording and pre-processing

We used a QuickAmp amplifier (Brain Products Inc.) and 65 Ag/AgCl electrodes to record the EEG signal during the task. Electrode impedances were kept below ten kΩ. The recording reference electrode was located at position FCz. The offline processing of the EEG data started with a down-sampling in which the sampling rate was reduced to 256 Hz. After a manual screening of each participant's EEG file to remove gross technical artifacts, a band-pass filter from.5 to 18 Hz (48db/oct each) was applied. Using the filtered data, an independent component analysis (ICA, infomax algorithm) as implemented in the BrainVision Analyzer 2 software package was conducted to correct periodically occurring artifacts (pulse artifacts, horizontal and vertical eye movements, and blinks). Afterward, stimulus-locked segments were built using the time point of STOP signal presentation as the locking point. Only correct trials (i.e., no response to the GO stimulus, no response before the onset of the CHANGE stimulus, and correct response to the CHANGE stimulus) were included in the analysis. Segments were built for the SCD0 and the SCD300 condition separately. The segmented data underwent an artifact detection and elimination procedure. All trials containing residual artifacts were discarded. The criteria for the artifact rejection step were: a maximal value difference of 200 μV in a 250 ms interval, amplitudes lower −150 μV or larger 150 μV or activity below.5 μV. After artifact rejection, a CSD transformation was applied to achieve a reference-free evaluation of the data before a baseline correction was applied in the time interval between −900 and −700 ms before STOP signal presentation. This baseline was used to obtain a pre-stimulus baseline (i.e., before the presentation of the GO stimulus). The procedure is identical to previous work using this paradigm (Mückschel et al., 2014). Deep learning was run on this data.

Deep learning was also run on the RIDE-decomposed data. For that, the baseline-corrected EEG data were used. Residue iteration decomposition was performed using the RIDE Matlab toolbox (manual available on http://cns.hkbu.edu.hk/RIDE.htm) (Ouyang et al., 2011). RIDE assumes that event-related potentials (ERPs) consist of different subprocesses with variable inter-component delays attributable to different processing stages. Since RIDE separates component clusters only by their latency variability but not by their scalp distributions and waveforms, the application of CSDs is not critical. RIDE derives a stimulus-associated S-cluster and a response-associated R-cluster by time markers, i.e., “latencies” (“SL” and “RL”), which are set to the time points of respective stimulus and response onsets in the EEG. Time markers for the derivation of the C-cluster (“CL”) are iteratively estimated and improved. In the current study, we only derived the S-cluster and the C-cluster because a response is first inhibited at the beginning of the STOP-CHANGE trial. When no R-cluster is modeled using RIDE, the motor response-related processes are included in the C-cluster (Ouyang et al., 2013). We did not model the R-cluster, since the R-cluster activity cannot reliably be estimated especially at the beginning of the analyzed trials since no response has to be executed on the STOP stimulus and the R-cluster needs the response information to be calculated. It is only possible to model the R-cluster on the CHANGE stimulus information. If we would have done so, we would have encountered imbalances in the modelling of epochs and conditions because an R-cluster can only reliably be estimated in the SCD300 condition and not in the SCD0 condition. In the SCD0 condition, the modelling of the R-cluster could have been biased by the STOP information because STOP and CHANGE information are presented simultaneously. For all these reasons, we computed the S-cluster and the C-cluster, which is also recommend in paradigms involving an inhibition of a motor response (Ouyang et al., 2013). RIDE requires the specification of a time window to extract the waveform of each RIDE cluster. For the current study, these time windows were set between −200 and 900 ms for the S-cluster and between 100 and 1100 ms for the C-cluster.

2.4. Deep learning procedure

Deep learning was run on the un-decomposed, baseline-corrected single-trial EEG data (data, which were not processed using RIDE) and on the decomposed single-trial EEG data (data processed using RIDE). For the RIDE-decomposed single-trial data, the deep learning was run separately for the single-trial S-cluster and the single-trial C-cluster data.

To predict whether an individual is faced with high or low demands during multi-component behavior, we used EEG data for deep learning in a well-established deep learning architecture (i.e., EEGNet) developed for EEG data (Lawhern et al., 2018a). Our group also used this deep learning architecture in previous studies (Vahid et al., 2020, 2019). Methodologically, the question equals a two-class decision problem; i.e., the deep learning algorithm has to decide whether segmented EEG data (single-trial data) is from the SCD0 or the SCD300 condition. Using EEGNet, this was done on the subject level. The architecture of EEGNet is delineated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Architecture of the EEGNet.

| Block | Layer Type | Filters | Size | Parameters | Output Dimension | Activation | Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Input |

(C,T) |

|||||

| Reshape |

(1,C,T) |

||||||

| Conv2D |

|

(1,64) |

64* |

(,C,T) |

Linear |

same |

|

| BatchNorm |

2* |

(,1,T) |

|||||

| DepthwiseConv2D |

D* |

(C,1) |

C*D* |

(,1,T) |

Linear |

valid |

|

| BatchNorm |

2*D* |

(,1,T) |

|||||

| Activation |

(,1,T) |

ELU |

|||||

| AveragePool2D |

(1,4) |

(,1,T/4) |

|||||

| Dropout |

(,1,T/4) |

||||||

| 2 |

SeparableConv2D |

|

(1,16) |

16*D* |

(,1,T/4) |

Linear |

same |

| BatchNorm |

2* |

(,1,T/4) |

|||||

| Activation |

(,1,T/4) |

ELU |

|||||

| AveragePool2D |

(1,8) |

(,1,T/32) |

|||||

| Dropout |

(,1,T/32) |

||||||

| Flatten |

(*T/32) |

||||||

| Dense | (*T/32) | N | Softmax | ||||

Before applying EEGNet, the data was down-sampled to 128 Hz. The first block of the network is designed to train temporal and spatial filters. Based on a 2D convolution with filters of sizes (1, 64), F1 feature maps are extracted. F1 indicates the number of temporal filters, and 64 is the kernel size chosen as half of the data sampling rate (i.e., 128 Hz). After the temporal filter step, batch normalization is employed. Then, a spatial filter with a 2D convolution of size (C, 1) is used, where C is the number of electrodes. The number of spatial filters for each temporal feature map represent by D. After the temporal and spatial filter step, batch normalization, Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) nonlinearity as an activation function, average pooling over four-time steps with a stride of four, and dropout are applied. A separable convolution is employed in the second block. Separable convolution is beneficial for preventing overfitting since it has fewer parameters than regular convolution. Again, batch normalization, followed by ELU activation, average pooling across eight-time steps, and dropout are applied. Finally, the model classifies the data samples based on a dense layer with a Softmax activation function. Importantly, the model's classification performance is estimated using a cross-validation technique (i.e., subject-wise K fold with k = 10). For that, the dataset is divided into ten groups with an equal number of participants. 90% of the individuals are picked for training with all of the associated trails, while the remaining 10% are used for testing. The procedure is repeated ten times, i.e., until all subjects have been part of a testing data set once. In each fold, four participants from the training set are chosen at random to serve as the validation set. It is important to note that the validation set is solely utilized for early stopping and not for training the model. Using subject-wise K fold allows us to estimate the model's performance without any leakage of data (i.e., single-trial EEG data) between participants. In other words, there are different sets for training, validation, and testing in each of the ten folds, with no overlap.

After 50 epochs of training, the model with the lowest cross-entropy in the validation set is saved. All results shown in this study are calculated based on the test set. Moreover, because the dataset is imbalanced (equal numbers of trials for each class), a class-weights to the loss function is applied. The class weights are the inverse of the proportion in the training data, with the majority class is set to one.

To ensure that the model classifies the data significantly better than a random classifier, the chance level for a two-classes problem is computed as suggested previously (Combrisson and Jerbi, 2015a). This method assumes that the classification error obeys a cumulative binomial distribution. For a two-class problem with an unlimited number of data, the chance level is 50%. However, it has been proven that this chance level is greater than 50% for a smaller number of trials (Combrisson and Jerbi, 2015a). To compute the chance level, the MATLAB function “binoinv” is employed (std(α) = binoinv(1−α,n,1c)∗100n, where α is the significance level, n is the number of predictions (i.e., number of data in the test set), and C is the number of classes). There are N = 239 participants in the sample, and the number of available trials for each participant ranged from 15 to 250. For the “SCD0″ and “SCD300″ classes, the samples are 21,447 and 18,693, respectively. We intend to predict two classes of EEG data on the single-trial and subject-level based on k = 10 folds cross-validation. This means that there are ten estimations of classification accuracy, their corresponding chance level (i.e., based on the data samples in each fold), and a threshold for each fold. Accuracies above the threshold are considered significant.

The “saliency mapping” approach is used to analyze what the model has learned [Ancona et al., 2017]. In this approach, the assumption is that the relevant features cause the model's output to change rapidly. The trained model is considered a constant, and we calculate the gradient of the model's output with respect to the input. Applying this method to EEG data leads to a heat map among all electrodes and time points, which can inform us of the contribution of each input feature to the model's decision. Some preprocessing steps are applied to improve the visualization of the saliency map results. The absolute values of all saliency maps from each single-trial EEG in a given class were averaged. In a normalizing step, the minimum and maximum of the averaged saliency map scores were then adjusted to 0 and 1, respectively. A score close to 1 implies that this feature has a crucial impact on classification accuracy [Vahid et al., 2020]. All figures for saliency maps in the result section are calculated based on the test sets in the K-fold method. It is worthwhile to mention that to infer relevant neurophysiological sub-processes for multi-component behavior, one needs to consider general task-relevant features. As a result, employing a grand average saliency map is a good strategy since it captures the model's attitude across all participants and trials. Of course, the significant features for each subject or trial can be different. However, grand averaging reduces the variations of important features among examples of the datasets (Farahat et al., 2019).

2.5. Considerations on the choice of the used deep learning method

EEGNet's performance has already been investigated using various event-related potential datasets (Heilmeyer et al., 2018; Lawhern et al., 2018a; Vahid et al., 2019, 2020). In the P300-based BCI competition, EEGNet proved to outperform other CNNs, recurrent networks, and traditional machine learning algorithms (Simões et al., 2020). However, in addition to the EEGNet (Lawhern et al., 2018a), also other Deep Neural Network (DNN) architectures have been developed for EEG data (Bashivan et al., 2015; Schirrmeister et al., 2017). Bashivan's et al. (2015) approach focuses on the frequency of the EEG signal (using information from Fast Fourier Transformation), which is not the focus of the current study. For the current study, it is essential that the time information of the EEG can be analyzed with high prevision because only this information can yield theoretically relevant insights into the cognitive processes being most important during multi-component behavior. The timing information is also essential for the saliency mapping approach which we use to inform the source reconstruction. The approach proposed by Bashivan et al. (2015) results in a data structure, which is hard to visualize. Even though the time information is not entirely discarded in Bashivan's et al. (2015) approach, time resolution is quite low because each trial is divided into seven frames.

Another DNN architecture, similar to the EEGNet by Lawhern et al. (2018a), has been proposed by Schirrmeister et al. (2017). Like EEGNet, this architecture has been inspired by a Filter bank common spatial patterns (FBCSP) algorithm (Zheng Yang Chin et al., 2009). However, EEGNet uses separable convolution, which has fewer parameters to estimate than ordinary convolution used in the DNN architecture by Schirrmeister et al. (2017). Consequently, EEGNet is less prone to overfitting.

2.6. Source localization analysis (sLORETA)

Using the information from the saliency map approach, we examined which functional neuroanatomical structures are associated with neurophysiological activity in time windows, contributing most to prediction accuracy. We used standardized low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA) (Pascual-Marqui, 2002). This method has well been validated in combined functional imaging-EEG and brain stimulation EEG studies (Dippel and Beste, 2015; Sekihara et al., 2005). The method has been shown to provide a single linear solution for the inverse problem without localization bias (Marco-Pallarés et al., 2005; Pascual-Marqui, 2002; Sekihara et al., 2005) using information from scalp electrodes with standard coordinates as defined in the 10/10 or 10/20 system. Technically, the algorithm uses a three-shell spherical head model. The head model's intra-cerebral volume is partitioned into 6239 voxels using a spatial resolution of 5 mm. For source localization, sLORETA calculates the standardized current density for every voxel. Brain region information is derived from the MNI152 head model template. For the sLORETA contrasts, we performed a comparison against zero. To account for the multiple-comparison problem when delineating voxel showing significant activity, we employed the sLORETA built-in voxel-wise randomization tests with 2,500 permutations and statistical non-parametric mapping procedures (SnPM). Significant voxels are shown in the MNI-brain.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral results

The mean reaction time (RT) for the Go condition was 478 ± 6.5 ms. On average, participants responded correctly in 95.9 ± .2% of all Go trials. Regarding the Stop condition, paired-sample t-tests showed that, on average, participants responded significantly faster in the SCD300 condition (805.3 ± 15.5 ms) than in the SCD0 condition (964.8 ± 14.1 ms; t(238) = 40.6; p < .001; d = 2.4). Beside faster responses, participants also showed significantly more correct responses in the SCD300 condition (86 ± .6%) compared to the SCD0 condition (83.1 ± .7%), as indicated by a t-test (t(238) = −4.7; p < .001; d = −0.3). The mean stop-signal delay (SSD) was 309.1 ± 9.8 and the average SSRT was 253.1 ± 5.1.

3.2. EEG results

The deep learning analysis was based on a two-class problem. The EEGNet deep learning architecture (Lawhern et al., 2018b) was trained on a training-set of SCD0 condition trials and SCD300 condition trials. Classification accuracy was then determined by applying the trained model on the test data. To evaluate the classification performance, a cross-validation technique (i.e., subject-wise K-fold with k = 10) was used. The analysis was conducted for the undecomposed data, for the RIDE S-cluster as well as for the RIDE C-cluster on single-trial level.

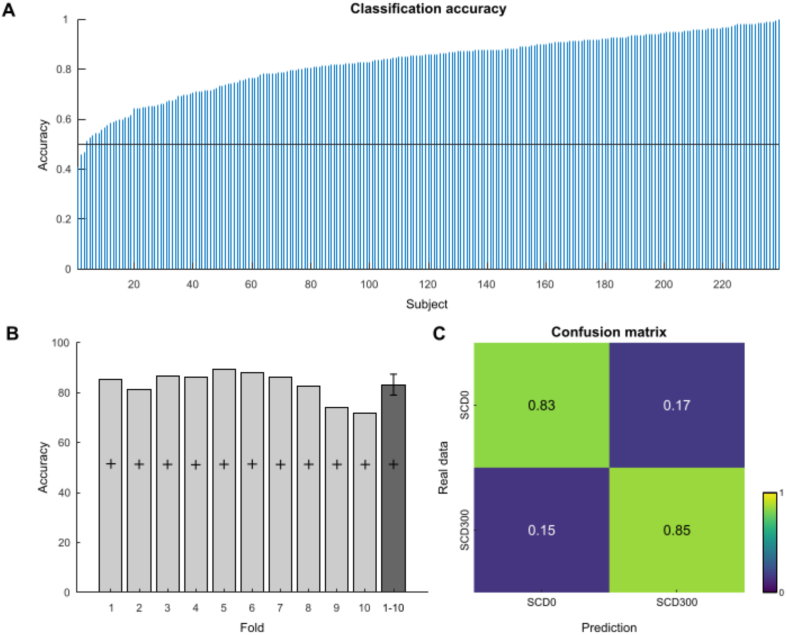

For undecomposed ERP data, Fig. 2A shows the classification accuracy of the two-class problem for each subject. The average classification accuracy was 86.7 ±.6%, well above the two-class problem chance level of 50%. Fig. 2B shows the classification accuracy per-fold as well as the specific chance levels as determined using the method by Combrisson and Jerbi (2015b). As can be seen, the accuracy was well-above chance level in all folds (mean 86.8 ± 1.4; confidence bounds 83.7 to 90). The confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracy of the EEGNet is depicted in Fig. 2 C. The real data i.e., the true condition labels are given in row-wise orientation (on the y-axis), the predicted labels are given column-wise (on the x-axis). As can be seen in the diagonal top-left to bottom-right the prediction accuracy was equally high for SCD0 and SCD300 at about ∼87%. Supplemental Fig. 1 shows the training and validation loss for one fold to confirm that the model does not suffer from overfitting. Epochs and losses are shown on the X and Y axes, respectively. As can be observed, there are not too many variations between training and validation loss. Both the training and validation losses have a decreasing trend until epoch 10, and after that, the validation loss oscillates, and the training loss is saturated.

Fig. 2.

Undecomposed data classification accuracy and confusion matrix. A) The classification accuracy for the two-fold problem for each individual subject is shown. Individual subjects are shown on the x-axis, sorted by accuracy. The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The horizontal black line denotes the chance level. B) Classification accuracy per fold is shown (x-axis). The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The plus denotes the specific chance levels as determined using the method by Combrisson and Jerbi (2015b). The dark grey bar shows the mean classification accuracy of folds 1 to 10, the error bars denote the upper and lower bounds of the 95 confidence interval the upper lower confidence bounds. C) Confusion matrix showing the classification results for SCD0 and SCD300 conditions. The colors and numbers in the matrix denote the frequency at which the real data was classified (y-axis) into one of the two possible predicted classes (x-axis). . (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

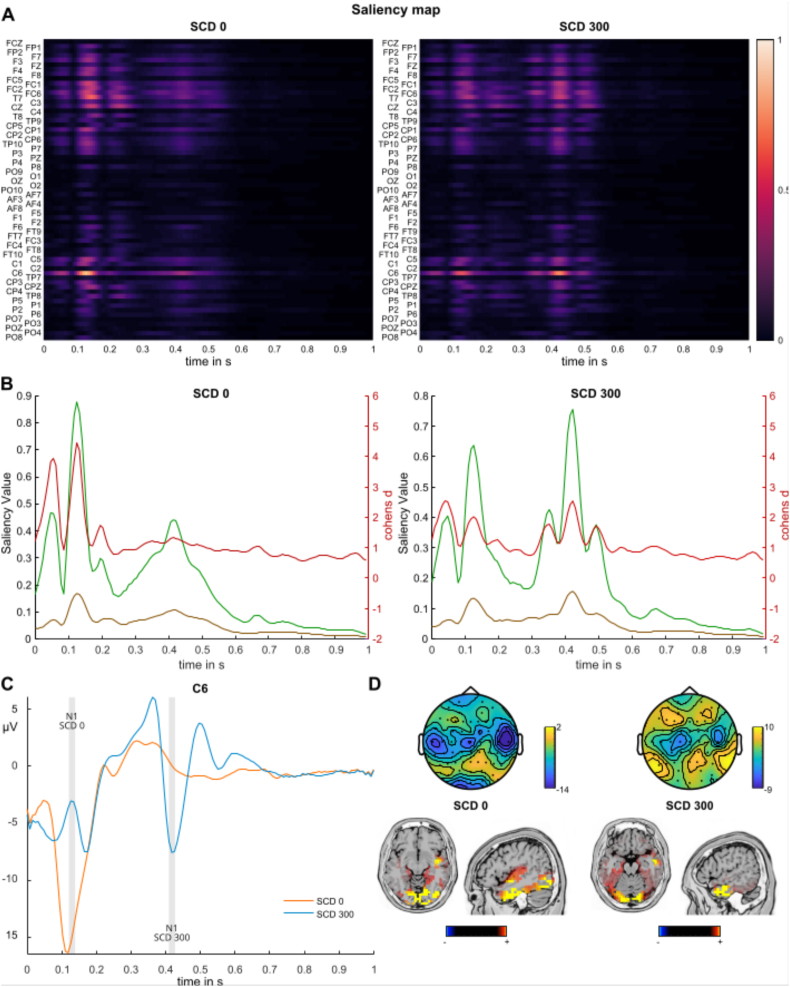

Saliency maps for the two classes SCD0 and SCD300 are presented in Fig. 3A. Fronto-central and central electrodes including C6, FC1, FC2, FC6, CZ, CP1 in the time windows from about 100 to 170 ms and 400–470 ms relative to STOP signal onset contributed most to the classification accuracy. As depicted in Fig. 3B, the highest saliency value in the SCD0 condition of 84% was observed at electrode C6 at 130 ms. For the SCD300 condition, the highest saliency value of 62% was also observed at electrode C6, but about 300 ms later at 410 ms than in the SCD0 condition. In contrast to the saliency values at electrode C6, parietal electrodes (including PO3, PO4, PO7, PO8, P7, and P8) typically connected to visual STOP signal processing contributed significantly less, as tested with FDR corrected paired-sample t-tests for each time point. The magnitude of these differences is corroborated by on average large Cohen's d effect sizes from .43 to 3.99 (mean 1.15) for the SCD0 condition and 0.25 to 2.29 (mean 1.14) for the SCD300 condition. As can be seen in Fig. 3C, the data point at 130 ms on electrode C6 showing the largest saliency values in the SCD0 condition overlap with the time window of the N1 ERP. This is also true for the SCD300 condition, where the N1 was observed about 300 ms later. Please refer to the supplemental material for a plot of all EEG electrodes. Topography plots of the respective N1 time windows are given in Fig. 3D. Below the topography plots, the results of the sLORETA source localization analysis for the N1 time window are presented. For the SCD0 condition sources in inferior/middle occipital areas (BA18, BA19) as well as inferior/middle temporal areas (BA20) and right superior temporal cortices (BA21) were activated.

Fig. 3.

Results of the deep learning analysis for undecomposed data. A) Saliency maps depicting the relevance of each datapoint and electrode for classification between the two classes. Higher values indicate that the specific feature at the respective time point contributed more to classification accuracy. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to STOP signal onset. B) Saliency values for electrode C6 as well as a pool of parietal electrodes (PO3, PO4, PO7, PO8, P7, and P8) are shown (primary left x-axis). Cohens'd effect sizes are given on the secondary (right) y-axis, depicting the effect sizes of the comparison of C6 and the pooled parietal electrodes by means of a dependent sample t-test. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to STOP signal onset. C) Event-related potential plots of electrode C6 of SCD0 and SCD300 condition. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to STOP signal onset. The grey shaded areas depict the peaks of the N1 in the SCD0 and SCD300 condition. D) Top: Scalp topography plots denoting amplitude distribution in the respective N1 time window of SCD0 and SCD300 condition. Below: Results of the sLORETA source localization for SCD0 and SCD300 condition. Only significant activations corrected for multiple comparisons are shown (p < .05).

3.3. RIDE S-cluster

For the RIDE decomposed S-cluster data, the classification accuracy for each subject is shown in Fig. 4A. The average classification accuracy was 83 ± .8% and therefore well above the chance level for a two-class problem of 50%. Fig. 4B shows the classification accuracy per-fold as well as the specific chance levels. Again, the accuracy was well-above chance level (mean 83.2 ± 1.9; confidence bounds 79 to 87.4). The confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracy of the deep learning architecture for the S-cluster is depicted in Fig. 4C. Prediction accuracy (i.e., diagonal top-left to bottom-right) was again almost equally high for SCD0 and SCD300 at about ∼84%.

Fig. 4.

RIDE S-cluster classification accuracy and confusion matrix. A) The classification accuracy for the two-fold problem for each individual subject is shown. Individual subjects are shown on the x-axis, sorted by accuracy. The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The horizontal black line denotes the chance level. B) Classification accuracy per fold is shown (x-axis). The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The plus denotes the specific chance levels as determined using the method by Combrisson and Jerbi (2015b). The dark grey bar shows the mean classification accuracy of folds 1 to 10, the error bars denote the upper and lower bounds of the 95 confidence interval. C) Confusion matrix showing the classification results for SCD0 and SCD300 conditions. The colors and numbers in the matrix denote the frequency at which the real data was classified (y-axis) into one of the two possible predicted classes (x-axis). . (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

As can be seen in Fig. 5A, the saliency maps for the two classes SCD0 and SCD300 are quite similar to the saliency maps for the undecomposed data. Again, predominantly fronto-central and central electrodes including C5, C6, FC1, FC2, FC6, CZ, CPz, CP1 but also T7 contributed strongly to the classification accuracy. The time window from 100 to 250 ms is of high relevance for the SCD0 (up to 88%). For the SCD300 condition the time window from 100 to 250 (up to 64%) as well as from 400 to 470 (up to 76%) contributed most. Similar to the undecomposed data, saliency values of the S-cluster data were highest at electrode C6 (SCD0 88% at 125 ms; SCD300 76% at 422 ms; see Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Results of the deep learning analysis for the RIDE S-cluster data. A) Saliency maps depicting the relevance of each datapoint and electrode for classification between the two classes are shown. Higher values indicate that the specific feature at the respective time point contributed more to classification accuracy. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to the STOP signal onset. B) Saliency values for electrode C6 as well as a pool of parietal electrodes (PO3, PO4, PO7, PO8, P7, and P8) are shown (primary left x-axis). Cohens'd effect sizes are given on the secondary (right) y-axis, depicting the effect sizes of the comparison of C6 and the pooled parietal electrodes by means of a dependent sample t-test. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to the STOP signal onset. C) Event-related potential plots of electrode C6 of SCD0 and SCD300 condition are shown. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to the STOP signal onset. The grey shaded areas depict the peaks of the S-cluster N1 in the SCD0 and SCD300 condition. D) Top: Scalp topography plots denoting amplitude distribution in the respective S-cluster N1 time window of SCD0 and SCD300 condition. Below: Results of the sLORETA source localization for SCD0 and SCD300 condition. Only significant activations corrected for multiple comparisons are shown (p < .05).

Again, saliency values at C6 were significantly larger compared to a pool of parietal electrodes (PO3, PO4, PO7, PO8, P7, P8). Large Cohen's d effect sizes were observed for the SCD0 (range 0.55–4.45, mean 1.2) and for the SCD300 condition (range 0.6–2.54; mean 1.15). For SCD0, the time window contributing most at electrode C6 overlapped with the N1-like potential in the S-cluster. This was also true for the SCD300 condition, where the N1-like potential occurred about 300 ms later. Please refer to the supplemental material for a plot of all EEG electrodes. Topography plots of the respective N1 time windows are given in Fig. 5D. Below the topography plots, the results of the sLORETA source localization analysis for the N1 time window are presented. The sLORETA revealed sources in the inferior/middle occipital areas (BA18, BA19) as well as inferior/middle temporal areas (BA20) and right superior temporal cortices (BA21).

3.4. RIDE C-cluster

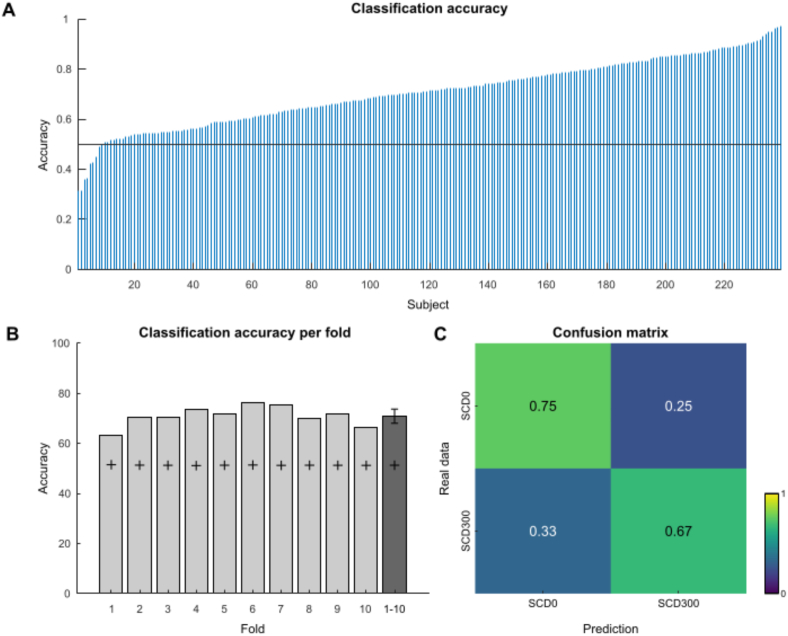

Regarding the RIDE decomposed C-cluster data, the classification accuracy for each subject is depicted in Fig. 6A. Compared to the undecomposed as well as RIDE S-cluster data, the average classification accuracy was slightly lower (70.7 ±.9%) but still well above chance level. Fig. 6B shows the classification accuracy per-fold as well as the specific chance levels. For all folds, the accuracy was above chance level (mean 70.9 ± 1.3; confidence bounds 68.1 to 73.7). Fig. 6C depicts the confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracy of the EEGNET architecture for the C-cluster data. Prediction accuracy (i.e., diagonal top-left to bottom-right) was slightly higher for SCD0 (∼75%) than for SCD300 (∼67%).

Fig. 6.

RIDE C-cluster classification accuracy and confusion matrix. A) The classification accuracy for the two-fold problem for each individual subject is shown. Individual subjects are shown on the x-axis, sorted by accuracy. The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The horizontal black line denotes the chance level. B) Classification accuracy per fold is shown (x-axis). The y-axis denotes the classification accuracy. The plus denotes the specific chance levels as determined using the method by Combrisson and Jerbi (2015b). The dark grey bar shows the mean classification accuracy of folds 1 to 10, the error bars denote the upper and lower bounds of the 95 confidence interval. C) Confusion matrix showing the classification results for SCD0 and SCD300 conditions. The colors and numbers in the matrix denote the frequency at which the real data was classified (y-axis) into one of the two possible predicted classes (x-axis). . (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

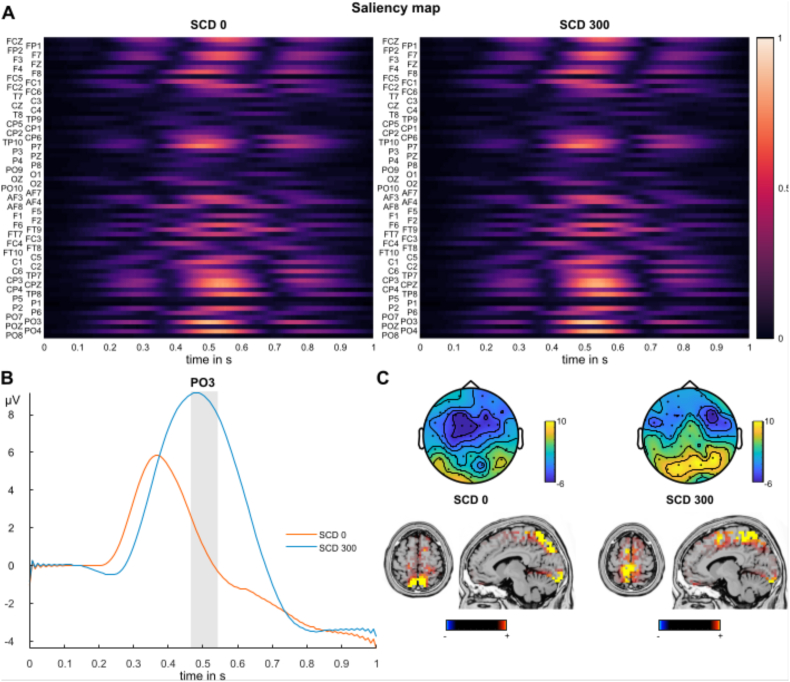

The saliency maps for the C-cluster data are shown in Fig. 7A. In contrast to the undecomposed and S-cluster data, posterior electrodes including CP3, CPz, PO3, PO4, P7 and TP8 contributed most to the classification accuracy. Here, the time window from 450 to 550 ms was of highest relevance for both the SCD0 (up to 86%) and the SCD300 condition (up to 89%). Electrode PO3 showed the largest contribution at 492 ms for SCD0 and 508 ms for SCD300. As can be seen in Fig. 7B, the amplitudes of the P3 like potential of the SCD300 condition were maximal within this time window. A plot of all EEG electrodes is given in the supplemental material. Fig. 7C shows topography plots of the time window of highest saliency. The sLORETA source analysis revealed sources in the superior and posterior parietal cortex (BA7) for SCD0 and SCD300, as well as in the superior frontal gyrus (BA6) for the SCD300 condition.

Fig. 7.

Results of deep learning analysis for RIDE C-cluster data. A) Saliency maps depicting the relevance of each data point and electrode for classification between the two classes. Higher values indicate that the specific feature at the respective time point contributed more to classification accuracy. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to the STOP signal onset. B) Event-related potential plot at electrode PO3 of SCD0 and SCD300 condition. The x-axis denotes the time in seconds relative to the STOP signal onset. The grey shaded areas depict the time window of highest saliency for SCD0 and SCD300 condition. C) Top: Scalp topography plots denoting amplitude distribution in the time window of highest saliency of SCD0 and SCD300 condition. Below: Results of the sLORETA source localization for SCD0 and SCD300 condition in the time window of highest saliency. Only significant activations corrected for multiple comparisons are shown (p < .05).

To investigate whether a simple machine learning model can achieve similar performance to EEGNet, we also used a Logistic Regression with the same procedure for training and evaluating the model's performance based on the subject-wise K-fold. The classification accuracy was 87%.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we used deep learning applied to EEG data to examine whether neurophysiological correlates of processes involved in multi-component behavior to decode (i.e. predict in terms of machine learning) whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on multi-component behavior. Moreover, we examined which precise cognitive-neurophysiological processes are most important for decoding whether a person is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands of multi-component behavior. To achieve this, we used a deep learning architecture specialized for EEG data combined with a “saliency map approach” to delineate which features in the neurophysiological contribute most to prediction accuracy. Based on the saliency mapping approach results, we used source localization methods to delineate which functional neuroanatomical structures are associated with the neurophysiological activity.

The behavioral data align with previous studies and show that reaction times on the CHANGE stimulus are the longest when STOP and CHANGE stimuli are presented simultaneously (Verbruggen et al., 2008). If the change process is signaled after a 300 ms delay relative to STOP stimulus presentation, reaction times are shorter. The likely reason is that the CHANGE stimulus is presented after the stop process has been finished. This is corroborated by the finding that the SSRT is faster than 300 ms. In the SCD300 condition, STOP and CHANGE processes do not demand restricted response selection capacities (Verbruggen et al., 2008).

4.1. Scenario 1

The deep learning results using un-decomposed EEG data revealed that classification accuracy on the single-subject level was ∼85%. The results from the saliency mapping approach revealed that processes in the time window between 100 and 170 ms after CHANGE stimulus presentation contributed most to the above-chance single-subject classification performance. In this time interval, the saliency map revealed that electrodes C6 and FC6 contributed substantially to classification accuracy (cf. Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Strictly electrode C6 revealed differences between the SCD0 and the SCD300 condition in the first study delineating neurophysiological processes during multi-component behavior using conventional event-related potential analyses (Mückschel et al., 2014). Notably, the EEG-based deep learning using the S-cluster data revealed the same pattern of results with a classification accuracy of ∼84%. Interestingly, it is shown that in the SCD300 condition, the same electrode sites contributed to classification accuracy between 400 and 470 ms. In the SCD300 condition, the auditory change signal is presented 300 ms after the stop signal. This clearly shows that attentional selection and sensory integration processes reflected by the N1 (Fu et al., 2001; Giard and Peronnet, 1999; Luck and Kappenman, 2013; Molholm et al., 2004; 2002; Murray et al., 2005) on the auditory CHANGE stimulus are relevant to decode whether an individual is faced with high or low demands during multi-component behavior. This is corroborated by the results from the source localization step. In the SCD0 and the SCD300 condition, the source estimation in the time window of the N1 (as shown in the saliency map) revealed activity modulations in the right superior and middle temporal gyrus (BA21) for the S-cluster. Right superior temporal cortices (BA21) were also associated with activity in the N1 time window for the un-decomposed data.1 Thus, attentional selection processes at the basic CHANGE stimulus encoding level can decode whether an individual is faced with high or low demands during multi-component behavior. Previously, other evidence suggested that these attentional and sensory integration processes are relevant during multi-component behavior (Brandt et al., 2017; Gohil et al., 2016b; 2015; Yildiz et al., 2014). However, from these previous findings, it could not be concluded that these processes are so important that they can decode whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on action cascading and multi-component behavior. The consistency of deep learning-based finding using decomposed and non-decomposed EEG data suggests that particularly cognitive-neurophysiological correlates of perceptual integration and attention in the time window between 100 and 170 ms after CHANGE stimulus presentation are most important to decode whether an individual is faced with high or low demands during multi-component behavior. Note that the task combines a stop-signal task with dual-task (i.e. psychological refractory period, PRP) task (Verbruggen et al., 2008). Even though for the latter mostly (strategic) response selection bottleneck models have been discussed, evidence also shows that attentional limitations can affect performance in dual task situations (Lien et al., 2006; Pashler, 1998) and that there are shared cortical bottlenecks for attentional and response selection capacity limitations (Marti et al., 2012). The current results provide further evidence that attentional selection processes is important during processes usually attributed to reflect response selection limitations. This is interesting because not only the CHANGE stimulus is essential to accomplish multi-component behavior in this task. Accurate processing of the visual STOP stimulus information is also essential. Without appropriate processing of the STOP stimulus information, no multi-component behavior is possible. In particular, in the SCD0 condition, both processes could be given equal priority in attentional processing. However, this does not seem to be the case since this would have led to a pattern in which visual STOP and auditory CHANGE information would have contributed equally to classification accuracy. Since the visual STOP information does not contribute much to the classification accuracy, this process seems remarkably invariant and runs with similar priority no matter whether demands on multi-component behavior are high or low. The data therefore suggest that especially attentional processes relevant for the CHANGE information are subject to capacity limitations. To process the CHANGE information, inter-modal shifts of attention are required. Future studies should examine the possible role of inter-modal changes in more detail.

4.2. Scenario 2

Compared to scenario 1, later time windows between 350 and 700 ms (i.e., the P3 time window) did not contribute much to classification accuracy using the un-decomposed EEG data, especially not in the SCD0 condition imposing the highest demands on multi-component behavior. Previous work suggested that processes in the P3 time window are modulated (Beste et al., 2014; Mückschel et al., 2014) because inhibitory control response selection processes, reflected by neurophysiological processes in this time window (Huster et al., 2013; Verleger et al., 2005, 1994) are demanded to a varying extent in the SCD0 and the SCD300 condition. Importantly, the findings using un-decomposed EEG data cannot be interpreted as evidence against the relevance of response selection processes in decoding whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on action cascading and multi-component behavior. As mentioned, event-related potentials are a mixture of activity from different anatomical sources (Huster et al., 2015; Nunez et al., 1997; Ouyang and Zhou, 2020). This is particularly the case for processes reflected by the P3 ERP-component, which not only reflects processes of mapping stimuli on the appropriate response (Ouyang et al., 2017; Verleger et al., 2014, 2005) but also processes of stimulus-driven working memory updating (Polich, 2007). The likely reason why the P3 time window at frontal and parietal electrode sites did not contribute much to classification accuracy is that stimulus-related information (i.e., of the STOP and CHANGE stimulus) is also modulating processes in the P3 time window (Polich, 2007). This information, however, is also captured by the neurophysiological processes in the preceding N1 time window. The deep learning algorithm considers all this information simultaneously. To the extent that stimulus-related information is already sufficiently contained in the N1 time window and can easily be captured in this time window, this aspect is no longer considered by the deep learning procedure when evaluating the P3 time window. Thus, important information determining the substantial variation in P3 amplitudes between the SCD0 and SCD300 conditions is not considered. This makes the P3 time window less distinctive and informative for classifying between SCD0 and SCD300 conditions. Stimulus-response translation processes that are also captured by activity in the P3 time window (Verleger et al., 2005, 1994) carry too little information for successful classification if information about sensory integration processes is also available. This interpretation is corroborated by the results from the deep learning analysis using the RIDE-decomposed data (i.e., the C-cluster). The RIDE clusters have a dissociable functional relevance (Ouyang et al., 2015). While the S-cluster is supposed to reflect stimulus-driven attentional selection processes (Ouyang et al., 2015), the C-cluster likely reflects stimulus-response translation processes (Ouyang et al., 2017; Verleger et al., 2014). Even though the C-cluster shows strong similarities to a P3 (Ouyang et al., 2017; Verleger et al., 2014), the C-cluster is less prone to bottom-up stimulus information because bottom-up stimulus information is typically assigned to the S-cluster during RIDE decomposition. The C-cluster likely represents information only relevant for the stimulus-response translation process (Takacs et al., 2020a, 2020b). When only the information of stimulus-response translation processes is available for deep learning, classification is possible, but the prediction accuracy was about 15–20 percent points lower (75% for the SCD0 condition and 67% for the SCD300 condition) than for the S-cluster (about 84%) and undecomposed data (about 87%). The saliency map results for the C-cluster data revealed that the time window between 400 and 700 ms after STOP stimulus presentation contributed strongly to classification accuracy in the SCD0 and the SCD300 condition. Neural activity in this time window was associated with activity modulations in the superior and posterior parietal cortex (BA7). However, in the SCD300 also the superior frontal gyrus (BA6) was involved. Notably, C-cluster activity has previously been associated with the superior parietal cortex function (Dilcher et al., 2021), which underlines the validity of the source localization results. Superior parietal mechanisms contribute to the selection of motor responses (Bernier et al., 2012; Cisek and Kalaska, 2002; Jaffard et al., 2008; Sulpizio et al., 2017), possibly because the superior parietal cortex plays a central role in stimulus-response translation processes (Gottlieb, 2007). Superior and posterior parietal areas serve to integrate perception and action (Gottlieb, 2007) by binding sensory and motor information into a representation used for goal-directed action (Gottlieb, 2007). The task used to assess multi-component behavior requires a complex integration of visual information (STOP stimulus) and auditory information (CHANGE stimulus) to inform response stopping and the execution of the alternative response. Moreover, the task requires complex rule processing because the rule determining the correct response on the CHANGE stimulus is derived by combining features of the CHANGE stimulus and the GO stimulus. Such rule-dependent selection and categorization processes are have also been associated with the parietal cortex (Gottlieb and Snyder, 2010). All these aspects explain the relevance of the processes and areas found to decode whether an individual is faced with a situation imposing high or low demands on multi-component behavior.

4.3. Limitations and outlook

Although logistic regression has a similar performance as EEGNet, two points need to be considered. First, by applying traditional machine learning algorithms like logistic regression to the raw EEG data, we concatenate all features (i.e., time points and channels) into one vector. Thus, the data structure of EEG data will be neglected, and the model cannot consider correlations between neighboring electrodes and channels. Each feature in logistic regression has its weight, which is independent of the other features' weight. Consequently, it would be possible that relevant features for the model are not near each other, and they are not plausible in terms of cognitive control theory. To infer neurophysiological processes, the relevant features for the model must be near electrode sites and time points. In contrast, EEGNet uses convolutional operation. Here, the significant neurophysiological features are close to each other in terms of time points and channels. Second, EEGNet's performance has been evaluated successfully on many ERP datasets (Heilmeyer et al., 2018; Lawhern et al., 2018b; Simões et al., 2020; Vahid et al., 2020, 2019). As a result, EEGNet is assumed to perform well in the case of a new ERP task. There is less experience with the application of logistic regression and SVM for ERP data. In the case of high dimensional datasets such as images and signals, it is widely suggested to use convolutional DNNs. It is difficult to decide a-priori which machine learning model is most suitable for a certain type of data. To answer this question one could apply logistic regression, SVM, and DNN and have a comparison among them. However, this study did not aim to find the best model for the SCD dataset. We chose EEGNet since its performance has been evaluated on a variety of ERP datasets, and its interpretability is simple thanks to the saliency maps. Importantly, since the mean response time between the two groups is indeed different (i.e., in SCD00 is 905 ms and in SCD 300,805 ms), one can argue that this experimental confound causes the model to reach high classification accuracy. The saliency map reveals that the important features rely on the classical ERP components. Thus, the model considers the data for classification accuracy. If the model classifies two groups based on the experimental confound, important features must be in the range of response time. However, the relevant features (i.e., classical ERP components) are less than the response time range.

We used a deep learning architecture specialized for EEG data combined with a “saliency map approach” to delineate which features in the neurophysiological contribute most to prediction accuracy. Even though this revealed the time intervals which contributed most to prediction performance, which is important because the functional interpretation of EEG signatures is strongly relying on the time point, the polarity, and the electrode site (Luck and Kappenman, 2013), future studies should aim delineating which features of the neurophysiological signal in each convolution layer of a deep learning architecture used to predict differences between groups/experimental conditions. This may yield more fine-grained insights into the neurophysiological mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated whether it is possible to decode (predict in terms of machine learning), using singe-trial EEG data and on a single-subject level, that an individual is confronted with high or low demands on multi-component behavior. This was achieved using EEG-based deep learning. We show that attentional selection and sensory integration processes in sensory association cortices were most predictive with ∼86%. Processes specifying rule-based response selection and translation, associated with superior and posterior parietal cortices, were also predictive with ∼70%. This, however, was only possible when information about sensory integration was discarded from the EEG signal. Therefore, sensory integration processes are important in decoding of whether an individual is confronted with a situation imposing high or low demands on response selection capacity limited multi-component behavior. The results provide insights into the relative importance of various cognitive processes during complex goal-directed behavior and suggest that attentional processes are important to consider during multi-component behavior.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by a Grant from the Volkswagen Stiftung “Experiment!".

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynirp.2022.100118.

However, the results from the source localization analysis also revealed that cortical areas along the ventral visual pathway revealed activity (i.e., the inferior and middle occipital gyri (BA18, BA19), inferior and middle temporal gyri (BA20)). The ventral visual pathway codes information about ‘what’ is presented (Goodale et al., 2005; Goodale and Milner, 1992) and thus critical information about stimulus features necessary to inform response control.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ancona M., Ceolini E., Öztireli C., Gross M. 2017. Towards Better Understanding of Gradient-Based Attribution Methods for Deep Neural Networks. arXiv:1711.06104 [cs, stat] [Google Scholar]

- Bashivan P., Rish I., Yeasin M., Codella N. 2015. Learning Representations from EEG with Deep Recurrent-Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv:1511.06448 [cs] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier P.-M., Cieslak M., Grafton S.T. Effector selection precedes reach planning in the dorsal parietofrontal cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:57–68. doi: 10.1152/jn.00011.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste C., Stock A.-K., Epplen J.T., Arning L. On the relevance of the NPY2-receptor variation for modes of action cascading processes. Neuroimage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borra D., Fantozzi S., Magosso E. A lightweight multi-scale convolutional neural network for P300 decoding: analysis of training strategies and uncovering of network decision. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.655840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt V.C., Stock A.-K., Münchau A., Beste C. Evidence for enhanced multi-component behaviour in Tourette syndrome - an EEG study. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridwell D.A., Cavanagh J.F., Collins A.G.E., Nunez M.D., Srinivasan R., Stober S., Calhoun V.D. Moving beyond ERP components: a selective review of approaches to integrate EEG and behavior. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018;12:106. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson B., Jolicoeur P. Cross-modal multitasking processing deficits prior to the central bottleneck revealed by event-related potentials. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:3038–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski W.X., Mückschel M., Beste C. Response selection codes in neurophysiological data predict conjoint effects of controlled and automatic processes during response inhibition. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39:1839–1849. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisek P., Kalaska J.F. Modest gaze-related discharge modulation in monkey dorsal premotor cortex during a reaching task performed with free fixation. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1064–1072. doi: 10.1152/jn.00995.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrisson E., Jerbi K. Exceeding chance level by chance: the caveat of theoretical chance levels in brain signal classification and statistical assessment of decoding accuracy. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, Cutting-edge EEG Methods. 2015;250:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combrisson E., Jerbi K. Exceeding chance level by chance: the caveat of theoretical chance levels in brain signal classification and statistical assessment of decoding accuracy. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, Cutting-edge EEG Methods. 2015;250:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilcher R., Beste C., Takacs A., Bluschke A., Tóth-Fáber E., Kleimaker M., Münchau A., Li S.-C. Perception-action integration in young age-A cross-sectional EEG study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2021;50:100977. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dippel G., Beste C. A causal role of the right inferior frontal cortex in the strategies of multi-component behaviour. Nat. Commun. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J. The multiple-demand (MD) system of the primate brain: mental programs for intelligent behaviour. Trends Cognit. Sci. 2010;14:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahat A., Reichert C., Sweeney-Reed C.M., Hinrichs H. Convolutional neural networks for decoding of covert attention focus and saliency maps for EEG feature visualization. J. Neural. Eng. 2019;16 doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/ab3bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein J.R., Van Petten C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:152–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu K.M., Foxe J.J., Murray M.M., Higgins B.A., Javitt D.C., Schroeder C.E. Attention-dependent suppression of distracter visual input can be cross-modally cued as indexed by anticipatory parieto-occipital alpha-band oscillations. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2001;12:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(01)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giard M.H., Peronnet F. Auditory-visual integration during multimodal object recognition in humans: a behavioral and electrophysiological study. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 1999;11:473–490. doi: 10.1162/089892999563544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohil K., Dippel G., Beste C. Questioning the role of the frontopolar cortex in multi-component behavior--a TMS/EEG study. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22317. doi: 10.1038/srep22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohil K., Hahne A., Beste C. Improvements of sensorimotor processes during action cascading associated with changes in sensory processing architecture-insights from sensory deprivation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28259. doi: 10.1038/srep28259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohil K., Stock A.-K., Beste C. The importance of sensory integration processes for action cascading. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9485. doi: 10.1038/srep09485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale M.A., Króliczak G., Westwood D.A. Dual routes to action: contributions of the dorsal and ventral streams to adaptive behavior. Prog. Brain Res. 2005;149:269–283. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)49019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale M.A., Milner A.D. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:20–25. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb J. From thought to action: the parietal cortex as a bridge between perception, action, and cognition. Neuron. 2007;53:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb J., Snyder L.H. Spatial and non-spatial functions of the parietal cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmeyer F.A., Schirrmeister R.T., Fiederer L.D.J., Volker M., Behncke J., Ball T. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC). Presented at the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) IEEE; Miyazaki, Japan: 2018. A large-scale evaluation framework for EEG deep learning architectures; pp. 1039–1045. 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huster R.J., Enriquez-Geppert S., Lavallee C.F., Falkenstein M., Herrmann C.S. Electroencephalography of response inhibition tasks: functional networks and cognitive contributions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013;87:217–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster R.J., Plis S.M., Calhoun V.D. Group-level component analyses of EEG: validation and evaluation. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:254. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffard M., Longcamp M., Velay J.-L., Anton J.-L., Roth M., Nazarian B., Boulinguez P. Proactive inhibitory control of movement assessed by event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1196–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhern V.J., Solon A.J., Waytowich N.R., Gordon S.M., Hung C.P., Lance B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional network for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces. J. Neural. Eng. 2018;15 doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawhern V.J., Solon A.J., Waytowich N.R., Gordon S.M., Hung C.P., Lance B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural. Eng. 2018;15 doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCun Y., Bengio Y., Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien M.-C., Ruthruff E., Johnston J.C. Attentional limitations in doing two tasks at once: the search for exceptions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006;15:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luck S.J., Kappenman E.S., editors. The Oxford Handbook of Event-Related Potential Components. Oxford library of psychology. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Pallarés J., Grau C., Ruffini G. Combined ICA-LORETA analysis of mismatch negativity. Neuroimage. 2005;25:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti S., Sigman M., Dehaene S. A shared cortical bottleneck underlying attentional blink and psychological refractory period. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2883–2898. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molholm S., Ritter W., Javitt D.C., Foxe J.J. Multisensory visual-auditory object recognition in humans: a high-density electrical mapping study. Cerebr. Cortex. 2004;14:452–465. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molholm S., Ritter W., Murray M.M., Javitt D.C., Schroeder C.E., Foxe J.J. Multisensory auditory-visual interactions during early sensory processing in humans: a high-density electrical mapping study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2002;14:115–128. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mückschel M., Chmielewski W., Ziemssen T., Beste C. The norepinephrine system shows information-content specific properties during cognitive control - evidence from EEG and pupillary responses. Neuroimage. 2017;149:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mückschel M., Stock A.-K., Beste C. Different strategies, but indifferent strategy adaptation during action cascading. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9992. doi: 10.1038/srep09992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mückschel M., Stock A.-K., Beste C. Psychophysiological mechanisms of interindividual differences in goal activation modes during action cascading. Cerebr. Cortex. 2014;24:2120–2129. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M.M., Molholm S., Michel C.M., Heslenfeld D.J., Ritter W., Javitt D.C., Schroeder C.E., Foxe J.J. Grabbing your ear: rapid auditory-somatosensory multisensory interactions in low-level sensory cortices are not constrained by stimulus alignment. Cerebr. Cortex. 2005;15:963–974. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez P.L., Srinivasan R., Westdorp A.F., Wijesinghe R.S., Tucker D.M., Silberstein R.B., Cadusch P.J. EEG coherency. I: statistics, reference electrode, volume conduction, Laplacians, cortical imaging, and interpretation at multiple scales. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1997;103:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang G., Herzmann G., Zhou C., Sommer W. Residue iteration decomposition (RIDE): a new method to separate ERP components on the basis of latency variability in single trials. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:1631–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang G., Hildebrandt A., Sommer W., Zhou C. Exploiting the intra-subject latency variability from single-trial event-related potentials in the P3 time range: a review and comparative evaluation of methods. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;75:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang G., Schacht A., Zhou C., Sommer W. Overcoming limitations of the ERP method with Residue Iteration Decomposition (RIDE): a demonstration in go/no-go experiments. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:253–265. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang G., Sommer W., Zhou C. A toolbox for residue iteration decomposition (RIDE)--A method for the decomposition, reconstruction, and single trial analysis of event related potentials. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2015;250:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]