Summary

Background

Antibiotics constitute a prevalent class of medications prescribed for pediatric patients. Concerns have arisen regarding the impact of early-life antibiotic use on the risk of atopic illnesses, including childhood atopic dermatitis (AD). AD affects approximately 2% of adults but is twice as prevalent in children, with rates ranging up to 4%. Therefore, the potential correlation between antibiotic exposure and childhood AD is of significant concern.

Methods

Relevant literature was searched from English databases (PubMed, Web of science, Scopus, and The Cochrane Library) and Chinese databases (CNKI database, VIP Database, Wanfang Database) to May 1, 2025. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to assess the association between antibiotic exposure and the risk of childhood AD. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024535141).

Findings

A total of 39 literature sources were included, encompassing 7,487,925 children. Meta-analysis showed that antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and childhood is associated with an increased risk of childhood AD (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.17–1.28; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.06%). The subgroup analyses showed that: (1) Children exposed to antibiotics during childhood had a higher risk of developing AD compared to those exposed to antibiotics during pregnancy; (2) the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure was significantly affected by the diagnostic criteria and race, but not living areas; (3) antibiotic exposure frequency and type of antibiotics may contribute to the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure; (4) the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure seems to be positive related with age of outcome measure but not the age of exposure.

Interpretation

Antibiotic exposure during pregnancy or early childhood enhances AD risk, with childhood exposure posing a higher risk than prenatal exposure. Exposure time (during pregnancy and childhood) and the age at outcome measurement are important influencing factors for this association. Diagnostic criteria, race, frequency of antibiotic exposure, and type of antibiotics may also affect this relationship. While the observed statistical significance may be associated with the increased statistical power afforded by the large sample size, the clinical implications of these findings warrant cautious interpretation. Further comprehensive and high-quality studies are warranted to clarify these findings.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang (LYY22H310002), the Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2024KY1170), Special Fund for the Incubation of Young Clinical Scientist, The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (CHZJU2023YS006).

Keywords: Antibiotic, Atopic dermatitis, Eczema, Children, Meta-analysis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Antibiotics represent one of the most frequently prescribed medications for pediatric patients. However, antibiotic administration may confer an increased risk of atopic diseases. Atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic skin disorder characterized by inflammation, eczema-like lesions, and severe itching, is particularly prevalent in children. Recent meta-analyses have focused primarily on pregnancy antibiotic exposure, and the results pertaining to childhood AD should be carefully interpreted given the limited number of studies included in these analyses. We conducted a comprehensive and systematic literature search, spanning from the inception of relevant research to May 1, 2025, with a focus on studies exploring the relationship between childhood AD and antibiotic exposure.

Added value of this study

Our finding showed that antibiotic exposure, both during pregnancy and childhood, is associated with an increased risk of childhood AD. The subgroup analyses were obtained including antibiotic exposure time (pregnancy or early childhood), diagnostic criteria, race, living environment, antibiotic exposure frequency, and type of antibiotics. Random-effects meta-regression were performed for age of exposure, age of outcome measure, and NOS. Our results suggest that antibiotic exposure time, diagnostic criteria, antibiotic exposure frequency, type of antibiotics, and age of outcome measure may be important influencing factors for this association.

Implications of all the available evidence

Antibiotic exposure during pregnancy or early childhood enhances AD risk, with childhood exposure posing a higher risk than prenatal exposure. Antibiotic exposure time, diagnostic criteria, race, antibiotic exposure frequency, type of antibiotics, and age of outcome measure may be important influencing factors for this association. The risk of AD seems to be positively correlated with antibiotic exposure frequency and age of outcome measure, indicating a potential dose-related and age-related increase in risk. Further comprehensive and high-quality studies are warranted to clarify these findings.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic skin condition characterized by inflammation, eczema-like lesions, and severe itching.1 It affects 2.0% of adults globally, but is twice as prevalent in children, with a prevalence of 4.0%.2 AD is a chronic and recurrent disorder that frequently co-occurs with allergic rhinitis, asthma, and other allergic conditions.3 It affects quality of life and imposes substantial financial and daily burdens on families.4 Thus, further exploring the risk factors of AD is crucial for facilitating prevention, optimizing treatment strategies, and enhancing public health awareness.

Antibiotics are amongst the most commonly used medications in children. However, antibiotic-treated children frequently have poorer gut microbiota diversity and community stability, which might impair immune system development and raise the risk of atopic illnesses. Our previous study found that pretreatment with azithromycin (AZI) exacerbates trimellitic anhydride (TMA)-induced AD-like pathology in mice, which may be related to the gut microbiota homeostasis.5 Although previous clinical and meta-analysis studies have reported inconsistent results regarding the relationship between antibiotic exposure during AD in children, increasing evidence from epidemiologic, experimental, and clinical studies support that antibiotic exposure contributes to the development and progression of childhood AD.6, 7, 8 Especially, several new high-quality studies have investigated the association between antibiotics exposure and childhood AD in recent years.9, 10, 11 Thus, an updated, comprehensive meta-analysis is critically required to deepen our understanding of the contribution of antibiotic exposure to the development of childhood AD.

This study conducted a meta-analysis to further explore the association between antibiotic exposure and the risk of childhood AD. We collected cohort studies of expectant mothers and young children, which may offer more robust and scalable evidence than before. Our findings may be critical for improving medical research and informing decision-making processes.

Methods

The study was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024535141) and conducted by the PRISMA guidelines. Ethical approval was not required as the current study was based on published data.

Literature search

We conducted a systematic search across four English-language databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Library) and three Chinese language databases: Wanfang Data (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (http://www.cnki.net/), and VIP Database (VIP) (http://www.cqvip.com/). All databases for relevant studies were searched up to May 1, 2025 without any language restriction. The search strategy incorporated a mix of MeSH and free text terms for key concepts relevant to “Atopic dermatitis”, “Eczema”, “Antibiotic”. The literature screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Studies must be cohort studies published as original articles. (2) The exposure of antibiotic should be during pregnancy or early childhood. (3) The outcome of interest must be childhood AD. (4) Studies must include raw data or report odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios (RRs), or hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the prevalence of childhood AD following antibiotic exposure.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Non-cohort studies. (2) Duplicate publications. (3) Studies without displaying specific data. (4) Non-primary literature, such as conference abstracts and reviews. (5) The outcome included data from individuals aged over 18 years.

Study selection

The total literature was managed using EndNote ×20. Two investigators independently evaluated the potentially eligible studies. Full texts of the studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria were screened to identify the final included studies. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by a third investigator.

Data collection

Two reviewers independently identified and recorded relevant information from the qualified research. Data extracted from the screened studies included: author, publication year, country, region, ethnicity, living environment, population, diagnosis basis, total sample size, antibiotic exposure sample size, AD sample size, type of antibiotics (if specified) and frequency of antibiotic exposure (if any). Any inconsistencies in data extraction were resolved by consulting with the corresponding author.

In this manuscript, terms such as “effect measures”, “effect sizes”, and “effect estimates” are used. However, it is important to clarify that in observational research, such as cohort studies, these metrics should more appropriately be described as “association measures”, “magnitude of association”, or “association estimates”, as they reflect statistical relationships observed in data rather than demonstrable causal effects.12

Quality assessment

Two independent reviewers used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the selection of study population, comparability between groups, and outcome measures for each article. Each study was classified as having a high (7–9), moderate (5–6), or low (≤4) quality, based on a full score of 9 on the NOS.13 In case of disagreement during the evaluation process, a third evaluator was consulted to determine the accuracy of the evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 18.0 software. HRs, RRs and ORs were treated as equivalent measures of risk given the incidence of childhood AD in the general population was less than 10%.2,14 Adjusted HRs, RRs and ORs with corresponding 95% confidence intervals were pooled directly as effect measures through random-effects modeling. All adjusted effect estimates were log-transformed and standardized to ensure scale comparability.15 Dichotomous data were aggregated as pooled Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was inferred based on whether the confidence interval excluded 1 or p-value <0.05. A random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was adopted when the number of included studies was greater than five. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method was used for subgroup meta-analyses with five or fewer studies.16,17

When multiple adjusted estimates were reported, the most comprehensively controlled estimates from each publication were preferentially extracted. When effect estimates for association between antibiotic exposure and childhood AD were not listed in the original article, but enough information was available, the effect estimates were calculated.18 External adjustments were made to account for potential confounding biases in studies that did not report adjusted estimates.19 Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the estimated effects differed between different statistical models separately. The complete data of extracted effect sizes is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Authors | Year | Sample size | Study design | Country/race | Diagnostic criteria | Living environment | Effect size, 95% CI | Adjusted model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aversa Z20 | 2021 | 14,572 | Population-based cohort study | America/European and American | ICD | Rural | Adjusted HR 1.47 (1.12–1.94) | Childhood onset, after adjustment for child confounders (male sex, birth weight, ethnicity, and cesarean section) and maternal confounders (age, education, smoking, and antibiotic use during pregnancy). |

| Böhme Mb21 | 2002 | 3786 | Prospective birth cohort study | Sweden/European and American | ISAAC | Urban | Crude OR 1.35 (1.17–1.57) Adjusted external OR 1.29 (1.11–1.50) |

Heredity; (Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Cantarutti A22 | 2022 | 73,816 | Retrospective cohort study | Italy/European and American | ICD | Unclear |

Antibiotic therapy = 1 Adjusted HR 1.03 (0.96–1.10) Antibiotic therapy = 2 Adjusted HR 0.99 (0.92–1.09) Antibiotic therapy ≥3 Adjusted HR 1.00 (0.93–1.09) |

Gender, year of birth, residence, and birth weight. |

| Adjusted HR 1.02 (0.96–1.07) | ||||||||

| Celedón JCb23 | 2002 | 448 | Prospective birth cohort study | America/European and American | NR | Urban |

Use of oral antibiotic 1 time Crude OR 0.9 (0.2–3.3) Adjusted external OR 0.9 (0.3–3.4) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age, and atopy. |

|

Use of oral antibioti at least 2 times Crude OR 1.3 (0.5–3.4) Adjusted external OR 1.1 (0.4–3.1) | ||||||||

| Chae J24 | 2024 | 2,177,755 | Retrospective cohort study | Korean/Asian | ICD | Unclear | Adjusted RR 1.11 (1.10–1.12) | Demographic characteristics such as age, type of medical insurance, primiparity, and multifetal pregnancy. Maternal health conditions (respiratory tract infection, asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergies, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, gastrointestinal disease, urinary tract infection, sexually transmitted infections, and drug dependence) and healthcare utilization (number of diagnoses, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and outpatient visits). |

| Chang YC25 | 2023 | 1,459,093 | Retrospective cohort study | The Taiwan of China/Asian | ICD | Urban and rural | Crude HR 1.13 (1.12–1.14) Adjusted HR 1.13 (1.12–1.14)a 1.05 (1.04–1.06)b 1.04 (1.03–1.05)c |

a:childbirth year, child's sex, gestational age, birth weight, apgar score, maternal age, urbanization, insurance property, mode of delivery, and type of pregnancy. b:childbirth year, child's sex, gestational age, birth weight, apgar score, maternal age, urbanization, insurance property, mode of delivery, type of pregnancy, maternal acetaminophen use during pregnancy, maternal comorbidities, maternal atopic disorders, gestational infections, and paternal age. c:childbirth year, child's sex, gestational age, birth weight, apgar score, maternal age, urbanization, insurance property, mode of delivery, type of pregnancy, maternal acetaminophen use during pregnancy, maternal comorbidities, maternal atopic disorders, gestational infections, paternal age, and frequency of outpatient clinic visits during pregnancy. |

| Dom S26 | 2010 | 670 | Prospective cohort study | Belgium/European and American | ISAAC | Urban | Crude OR 1.90 (1.29–2.78) Adjusted OR 1.82 (1.14–2.92) |

Gender, maternal age, birth weight, siblings, breastfeeding, pre- and post-natal exposure to cats or dogs, pre- and post-natal exposure to cigarette smoke, day care attendance, parental education and parental history of allergies. |

| Farooqi IS27 | 1998 | 1855 | Birth cohort Study |

UK/European and American | NR | Urban | Crude OR 2.04 (1.53–2.73) Adjusted external OR 1.95 (1.46–2.60) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Fuxench ZC28 | 2024 | 1,023,140 | Prospective cohort study. | UK/European and American | NR | Unclear |

Penicillin Crude HR 1.70 (1.67–1.73) Adjusted HR 1.76 (1.72–1.80) Sulfa Crude HR 1.46 (1.37–1.56) Adjusted HR 1.42 (1.31–1.53) Cephalosporin Crude HR 1.70 (1.56–1.85) Adjusted HR 1.96 (1.76–2.18) Macrolide Crude HR 1.77 (1.69–1.86) Adjusted HR 1.86 (1.75–1.98) |

Maternal AD, maternal exposure to antibiotics, sex of the child assigned at birth, child's other allergic illnesses, Townsend index and ethnicity. |

| Gao X29 | 2019 | 903 | Prospective, community-based birth cohort study | China/Asian | NR | Urban |

Exposed during pregnancy Crude OR 3.51 (1.26–9.80) Adjusted OR3.59 (1.19–10.85) |

Infant's sex and other exposure variables associated with eczema during the first year of life. |

|

Exposed in the first year Crude OR 0.43 (0.27–0.67) Adjusted OR 0.44 (0.28, 0.70) | ||||||||

| Geng MLb30 | 2021 | 2453 | Birth cohort | China/Asian | NR | Urban and rural | Crude OR 1.14 (0.96–1.36) Adjusted external OR 1.12 (0.94–1.33) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) maternal age at delivery, parity, marital status, prepregnancy body mass index, preexisting hypertension, preexisting diabetes, maternal history of allergies, antipyretic or analgesic use during pregnancy, maternal education, household income, complication of pregnancy or delivery, morning sickness, weight gain during pregnancy, urinary cotinine concentration during pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, sex of the infant, premature birth, birth weight, breast-feeding, and pet ownership. |

| Hoskin-Parr L31 | 2013 | 5780 | Birth cohort study | UK/European and American | NR | Urban and rural | Adjusted OR 1.20 (1.02–1.41) | Child-based variables (sex, ethnicity and age of child at time of outcome), birth-related variables (mother's age at time of delivery, birth mode, birthweight and gestation), socioeconomic status (marital status, home ownership status, mother's highest educational qualification and degree of difficulty in paying for food) and lifestyle variables (child breastfed, time spent outdoors by the child, disinfectant use by mother during pregnancy, mother's smoking during pregnancy and child's contact with cats). |

| Hoskinson Cb32 | 2024 | 2484 | Prospective cohort study. | Canada/European and American | ISAAC | Urban | Crude OR 1.29 (1.02–1.63) Adjusted external OR 1.23 (0.98–1.56) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Hua Lb33 | 2021 | 593 | Prospective birth cohort study | China/Asian | ISAAC | Urban | Crude OR 2.00 (1.39–2.87) Adjusted external OR 1.96 (1.37–2.82) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) maternal age at delivery, parity, marital status, prepregnancy body mass index, preexisting hypertension, preexisting diabetes, maternal history of allergies, antipyretic or analgesic use during pregnancy, maternal education, household income, complication of pregnancy. or delivery, morning sickness, weight gain during pregnancy, urinary cotinine concentration during pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, sex of the infant, premature birth, birth weight, breast-feeding, and pet ownership. |

| Jedrychowski W34 | 2006 | 102 | Cohort study | America/European and American | ISAAC | Urban | Adjusted OR 2.30 (0.91–5.81) | Multiple logistic regression mod els were used to analyze the association between the use of antibiotics and the occurrence of wheezing and allergy, with adjustment to potential confounding variables. |

| Kelderer F35 | 2022 | 1387 | Prospective cohort study | Sweden/European and American | NR | Urban and rural |

Prenatal antibiotic exposure Crude OR 1.08 (0.72–1.64) Adjusted OR 0.92 (0.58–1.47) |

Infant sex, maternal and paternal history of allergic disease, exposure to pets (cats and dogs), and exposure to farm animals. |

| prenatal antibiotic exposure 1240 |

Postnatal antibiotic exposure Crude OR 1.50 (1.12–2.00) Adjusted OR 1.49 (1.07–2.06) |

|||||||

| postnatal antibiotic exposure 1245 |

Crude OR 1.33 (1.05–1.68) Adjusted OR 1.27 (1.00–1.60) |

|||||||

| Kummeling I36 | 2007 | 815 | Cohort study | Netherlands/European and American | ISAAC | Unclear | Crude OR 1.08 (0.81–1.44) Adjusted OR 1.07 (0.80–1.42) |

Gender, parental history of allergy, sibling history of allergy, number of older siblings, place and mode of delivery, breastfeeding, day care attendance, pets, exposure to ETS, vaccinations, fever, and subcohort. |

| Levin MEb37 | 2020 | urban 1185 | Prospective study | South Africa/African | Hanifin and Rajka standards | Urban | Crude OR 1.34 (1.02–1.74) Adjusted external OR 1.28 (0.98–1.66) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| rural 398 | Rural | Crude OR 1.03 (0.12–8.54) Adjusted external OR 0.98 (0.12–8.16) |

||||||

| Mai XM38 | 2010 | 3306 | Population-based cohort study | Sweden/European and American | ISAAC | Urban |

Measured at 4 years old Crude OR 1.3 (1.1–1.5) Adjusted OR 1.3 (1.1–1.5) Measured at 8 years old Crude OR 1.3 (1.1–1.6) Adjusted OR 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

Sex, young maternal age, older sibling, maternal smoking, parental allergy and exclusive breastfeeding. |

| McKeever TM11 | 2002 | 19,133 | Birth cohort study | UK/European and American | NR | Unclear |

Penicillin Crude HR 1.23 (1.11–1.35) Adjusted HR 1.07 (0.97–1.18) |

Consultation rates in the first year of life. |

|

Amoxycillin Crude HR 1.31 (1.22–1.40) Adjusted HR 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | ||||||||

|

Macrolides Crude HR 1.13 (1.05–1.22) Adjusted HR 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | ||||||||

|

Cephalosporins Crude HR 1.10 (0.98–1.24) Adjusted HR 0.90 (0.80–1.02) | ||||||||

| Metzler S39 | 2019 | During pregnancy 1080 <1 years 1019 |

Prospective birth cohort | Europe/European and American | NR | Rural | Crude OR 1.67 (1.35–2.12) Adjusted OR 1.61 (1.28–2.03) Exposed in pregnancy Adjusted OR 1.23 (0.73–2.09) Exposed in 1st year Adjusted OR 1.92 (1.29–2.86) |

Farmer, centre, parental atopic status, gender, smoking during pregnancy, number of siblings, pets (dogs and cats) during pregnancy, caesarean section, maternal education. |

| Mitre E40 | 2018 | 792,130 | Retrospective cohort study | America/European and American | ICD | Unclear | Adjusted HR 1.18 (1.16–1.19) | Prematurity, cesarean delivery, sex, the other drug classes, and any significant first-order interaction terms.-During the first 6 months of life. |

| Mubanga M41 | 2021 | 722,767 | Prospective cohort study | Sweden/European and American | ICD | Unclear | Adjusted HR 1.10 (1.09–1.12) | Age, sex, mother's age, family situation, parity, level of education, area of residence, smoking history, maternal history of asthma, and mode of delivery. |

| Okoshi Ka42 | 2023 | 61,706 | Birth cohort study | Japan/Asian | ISAAC | Urban and rural | Crude OR 1.04 (0.99–1.10) Adjusted OR 1.02 (0.97–1.08) |

Maternal age at delivery, parity, marital status, prepregnancy body mass index, preexisting hypertension, preexisting diabetes, maternal history of allergies, antipyretic or analgesic use during pregnancy, maternal education, household income, complication of pregnancy or delivery, morning sickness, weight gain during pregnancy, urinary cotinine concentration during pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, sex of the infant, premature birth, birth weight, breast-feeding, and pet ownership. |

| Park MJ43 | 2021 | 1637 | Prospective cohort study | Korea/Asian | NR | Unclear | Adjusted OR 1.84 (1.18–2.86) | Sex, maternal education, family history of allergic disease, breastfeeding, and mode of delivery. |

| Peng Z44 | 2025 | 1640 | Birth cohort study | German/European and American | NR | Unclear | Adjusted HR 1.30 (0.98–1.72) | The maternal age at baseline, mothers' education level, children's first-degree relatives' history of AD at baseline, mother ever having a fever during pregnancy, maternal smoking status during pregnancy, maternal BMI before pregnancy, children's sex, preterm birth, delivery mode, birth weight, exclusive breastfeeding duration, history of antibiotic use in the first year of life and having at least one older sibling or not. |

| Räty Sb45 | 2024 | 11,255 | Prospective Birth cohort |

Finland/European and American | ICD | Unclear |

Exposed in neonatal period Crude OR 1.12 (0.90–1.39) Adjusted external OR 1.107(0.87–1.32) Exposed before six months of birth Crude OR 0.93 (0.79–1.10) Adjusted external OR 0.89 (0.75–1.05) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Sariachvili Mb46 | 2007 | 952 Pregnancy | Prospective study | Belgium/European and American | NR | Unclear |

Exposed in pregnancy Crude OR 1.7 (1.2–2.4) Adjusted external OR 1.62 (1.15–2.29) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| 926 Birth |

Exposed before first 12 months Crude OR 1.2 (0.9–1.6) Adjusted external OR 1.15 (0.86–1.53) |

|||||||

| Schmitt Jb47 | 2010 | 370 | Population-based cohort study | Germany/European and American | ICD | Urban |

Penicillins RR 0.88 (0.37–2.12) Macrolides RR 1.83 (1.00–3.35) Cephalosporines RR 1.73 (0.98–3.08) Sulphonamides RR 1.91 (0.54–6.70) Adjusted external OR 1.71 (0.91–3.21) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Slob EMA48 | 2020 | 3–12 years 35,183 9 years 7916 |

Cohort study | Netherlands/European and American | NR | Unclear | Adjusted OR 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | Educational attainment, hours of outside childcare, breastfeeding, delivery mode, gender, birth weight, asthma. |

| Su Yb49 | 2010 | 424 | Prospective Birth cohort |

America/European and American | NR | Unclear | Crude OR 0.74 (0.48–1.15) Adjusted external OR 0.71 (0.46–1.09) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Tai SK50 | 2024 | 900,584 | Cohort study | The Taiwan of China/Asian | ICD | Unclear | Adjusted HR 1.14 (1.13–1.15) | Model adjusted for maternal age, mode of delivery, preterm delivery, maternal comorbidity, maternal allergic disease, pregnancy-related complication, neonatal gender. |

| Taylor–Robinson DCa51 | 2016 | 12,917 | Cohort study | UK/European and American | ISAAC | Urban and rural | Adjusted OR 1.28 (1.16–1.42) | Sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Tetsuya T52 | 2021 | 85,954 | Retrospective study | Japan/Asian | ICD | Unclear | Crude HR 1.21 (1.14–1.29) Adjusted HR 1.12 (1.04–1.21) |

Sex, comorbidities (food allergies, allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma and allergic conjunctivitis) at <12 months of age. Also adjusted for concomitant medicine (probiotics, histamine H1 receptor antagonist, histamine H2 receptor antagonist, leukotriene receptor antagonist, carbocysteine, ambroxol, tipepidine hibenzate and acetaminophen) at <12 months of age as confounders. |

| Timm Sb53 | 2017 | 62,560 | Population-based cohort study | Denmark/European and American | ISAAC | Urban and rural | Crude OR 1.10 (1.06–1.15) Adjusted external OR 1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Vassilopoulou Eb54 | 2023 | 501 | Prospective cohort study. | Greece/European and American | NR | Urban and rural |

Exposed in pregnancy Crude OR 0.84 (0.43–1.64) Adjusted external OR 0.81 (0.41–1.56) Exposed after birth Crude OR 0.82 (0.51–1.32) Adjusted external OR 0.78 (0.49–1.26) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Wickens K55 | 2008 | 1064 0–15 months 1011 |

Cohort study | New Zealand/European and American | ISAAC | Urban | Crude OR 1.44 (1.13–1.83) Adjusted external OR 1.37 (1.08–1.75) Exposed in 0–15 months Crude OR 1.71 (1.27–2.29) Adjusted OR 1.71 (1.26–2.33) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. Each outcome is mutually adjusted for antibiotic exposure and chest infections (1, 21 vs. none) occurring 0–15 months. |

| 3–4 years 967 |

Exposed in 3–4 years Crude OR 1.23 (0.93–1.61) Adjusted OR 1.14 (0.87–1.51) |

Each outcome is mutually adjusted for antibiotic exposure and chest infections (1, 21 vs. none) occurring 3–4 years. | ||||||

| Wohl DLb56 | 2015 | 507 | Retrospective study | America/European and American | NR | Unclear | RR 1.03 (0.75–1.41) Crude OR1.07 (0.69–1.68) Adjusted external OR 1.02 (0.66–1.60) |

(Adjusted by external estimates) sex, ethnicity, maternal age and atopy. |

| Yamamoto-Hanada K57 | 2017 | 902 | Prospective birth cohort study | Japan/Asian | ISAAC | Urban |

All antibiotics Crude OR 1.42 (1.03–1.95) Adjusted OR 1.40 (1.01–1.94) |

Maternal history of allergy (asthma, atopic dermatitis, or allergic rhinitis), maternal education level, maternal age at pregnancy, maternal body mass index, maternal smoking during pregnancy, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, previous live births, daycare, bronchitis, and sex of the child. |

|

Penicillin Crude OR 1.42 (0.83–2.44) Adjusted OR 1.41 (0.82–2.43) Cephem Crude OR 1.41 (0.98–2.04) Adjusted OR 1.37 (0.94–1.99) Macrolide Crude OR 1.59 (1.09–2.32) Adjusted OR 1.58 (1.07–2.33) |

Abbreviations: NR: not reported; ICD: Irritant Contact Dermatitis; ISAAC: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Two articles that used to calculate the U value.

The raw data were adjusted using external estimate.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and was interpreted as follows: I2 = 0–25%: low degree of heterogeneity; I2 = 25–50%: moderate degree of heterogeneity; I2 = 50–100%: high degree of heterogeneity. In accordance with the PICOS format, subgroup analyses (for categorical variables) and univariate random-effects meta-regression (for continuous variables) were conducted to explore potential heterogeneity arising from seven factors: race, living environment, age of antibiotic exposure, type of antibiotics, frequency of antibiotic exposure, age of outcome measurement, NOS score.58,59 The linearity of continuous predictors in meta-regression were assessed through scatterplots with locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curves and residual normality were evaluated by quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots.60 Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding each study one at a time to examine the impact of that study on the pooled point estimate. Funnel plots and the Egger linear regression test were performed to assess publication bias.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

The study selection process is depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 6892 articles were identified through literature screening, comprising 75 in Chinese and 6817 in English. After removing 2666 duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts, 4143 articles were excluded, leaving 83 for further consideration. Following a full-text assessment, 42 articles were excluded due to inappropriate study populations, irrelevant outcomes, conference abstracts, insufficient data, not cohort studies or unavailable full texts. Ultimately, 39 articles9,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 were included in the final analysis, after excluding two articles61,62 because of details.

Study characteristics

This meta-analysis included 399,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 articles involving a total of 7,487,925 participants to measure the association between antibiotic exposure and the risk of AD. Among the included 39 studies,9,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 17 9,21,23,26,29,32,33,35,37,39,41,43,45,46,49,54,57 were prospective cohort studies on AD,7 20,22,24,25,40,52,56 were retrospective cohort studies on AD, 6 11,27,30,31,42,44 were birth cohort studies, and 934,36,38,47,48,50,51,53,55 reported cohort study designs without specifying the type. Fifteen studies provided adjusted OR,26,27,29,31,34, 35, 36,38,39,42,43,48,51,55,57 nine studies provided adjusted HR, 9,20,22,25,40,41,44,50,52 two study provided RR, 47,56 one study provided adjusted RR24 and twelve studies provided sufficient data to calculate OR11,21,23,30,32,33,37,45,46,49,53,54 The included literatures were involving populations across Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and Africa. The basic characteristics and details of these studies are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. The quality of the included literature was evaluated using the NOS scale (Supplementary Table S2). A total of three studies obtained a quality assessment score of 9,20,26,39 fifteen scored 8,9,11,21, 22, 23,25,29,31,38,41,42,46,47,52,54 sixteen scored 7, 24,30,32, 33, 34,36,40,43,45,48, 49, 50, 51,53,55,57 and five studies received a score of 627,35,37,44,56 on the NOS quality assessment tool. The included studies exhibited a high standard of quality, characterized by reliable data across the key assessment categories of selection, comparability, and outcome.

Main analysis

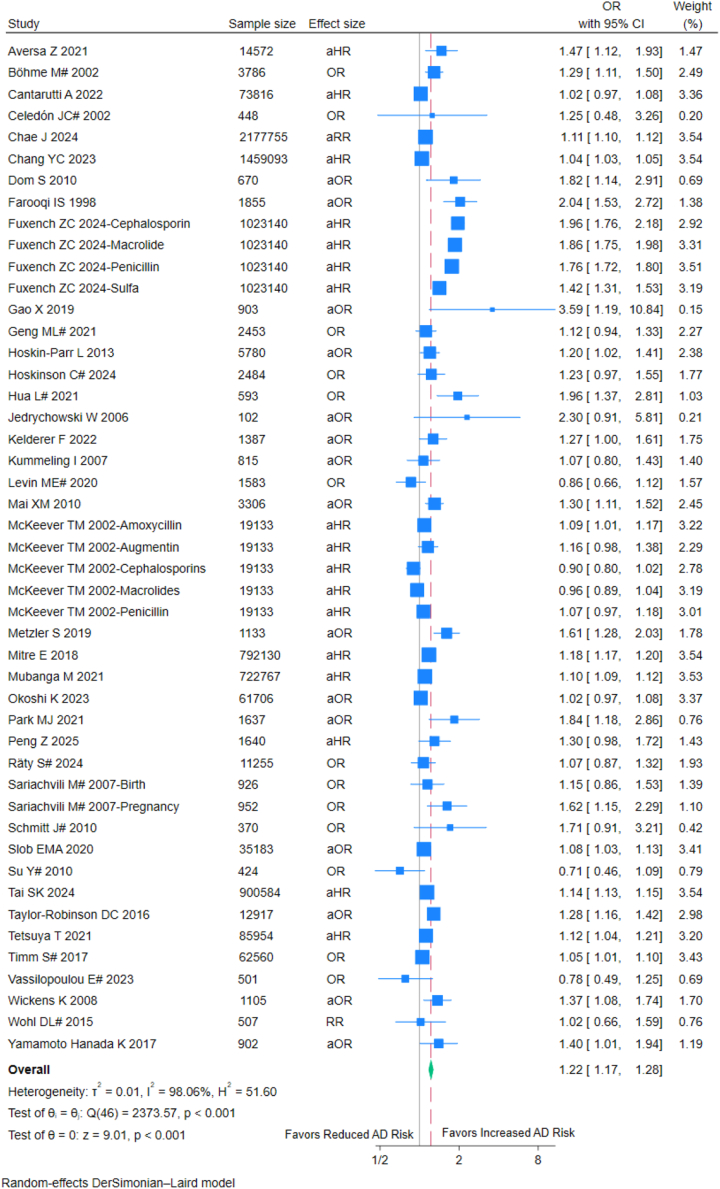

The meta-analysis of 399,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 studies (7,487,925 children) indicated that antibiotic exposure was associated with a 22% increased odds of childhood AD (pooled OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.17–1.28; I2 = 98.06%) (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analyses demonstrated consistent results across different statistical models: the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.14–1.32; I2 = 99.28%), adjusted odds ratio (aOR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.19–1.45; I2 = 80.59%), and unadjusted odds ratio (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.08–1.31; I2 = 60.66%) all supported this association (Supplementary Figures S1–S2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of analysis based on antibiotic exposure. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; #: externally adjusted OR.

Subgroup analyses

To investigate the sources of heterogeneity and clarify the relationship between various subgroups and the main outcome, we conducted several subgroup analyses, including exposure time, diagnostic criteria, race, living environment, type of antibiotics, frequency of antibiotic exposure.

Subgroup analysis based on exposure time (pregnancy or childhood)

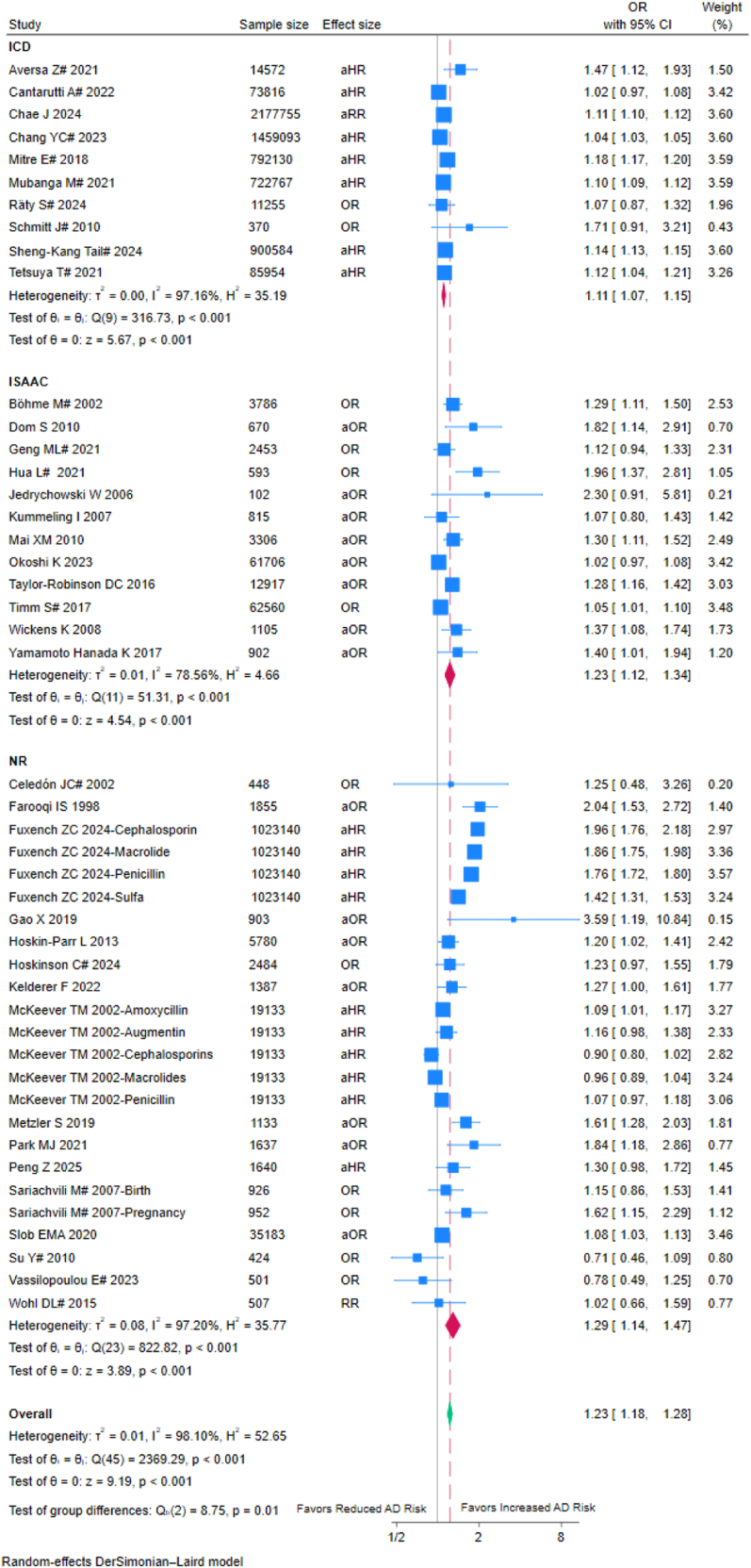

Childhood antibiotic exposure demonstrated a stronger association with AD (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.13–1.34; I2 = 97.53%) compared to exposure during pregnancy (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.05–1.13; I2 = 93.85%) (Fig. 3). The 14% absolute difference in odds ratios between subgroups reached statistical significance (p for interaction = 0.008), the non-overlapping confidence intervals suggest a higher magnitude of risk from childhood exposure.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on exposure time (pregnancy or childhood); OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; #: externally adjusted OR.

Subgroup analysis based on diagnostic criteria

Among the 399,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 studies, 10 used ICD codes20,22,24,25,40,41,45,47,50,52 (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.07–1.15; I2 = 97.16%), 12 employed the ISAAC questionnaire21,26,32, 33, 34,36,38,42,51,53,55,57 (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.12–1.34; I2 = 78.56%), 1 used the Hanifin-Rajka criteria,37 and 16 using unclear diagnostic criteria 9,11,23,27,29, 30, 31,35,39,43,44,46,48,49,54,56 (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.14–1.47; I2 = 97.20%) (Fig. 4). The increase in AD risk defined using ICD coding was significantly lower than ISAAC questionnaire and unclear diagnostic criteria (p for interaction = 0.01), suggesting that diagnostic methods may influence effect estimates.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on diagnostic criteria. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval, NR: unclear diagnostic criteria group; ICD: Irritant Contact Dermatitis; ISAAC: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; #: externally adjusted OR.

Subgroup analysis based on race

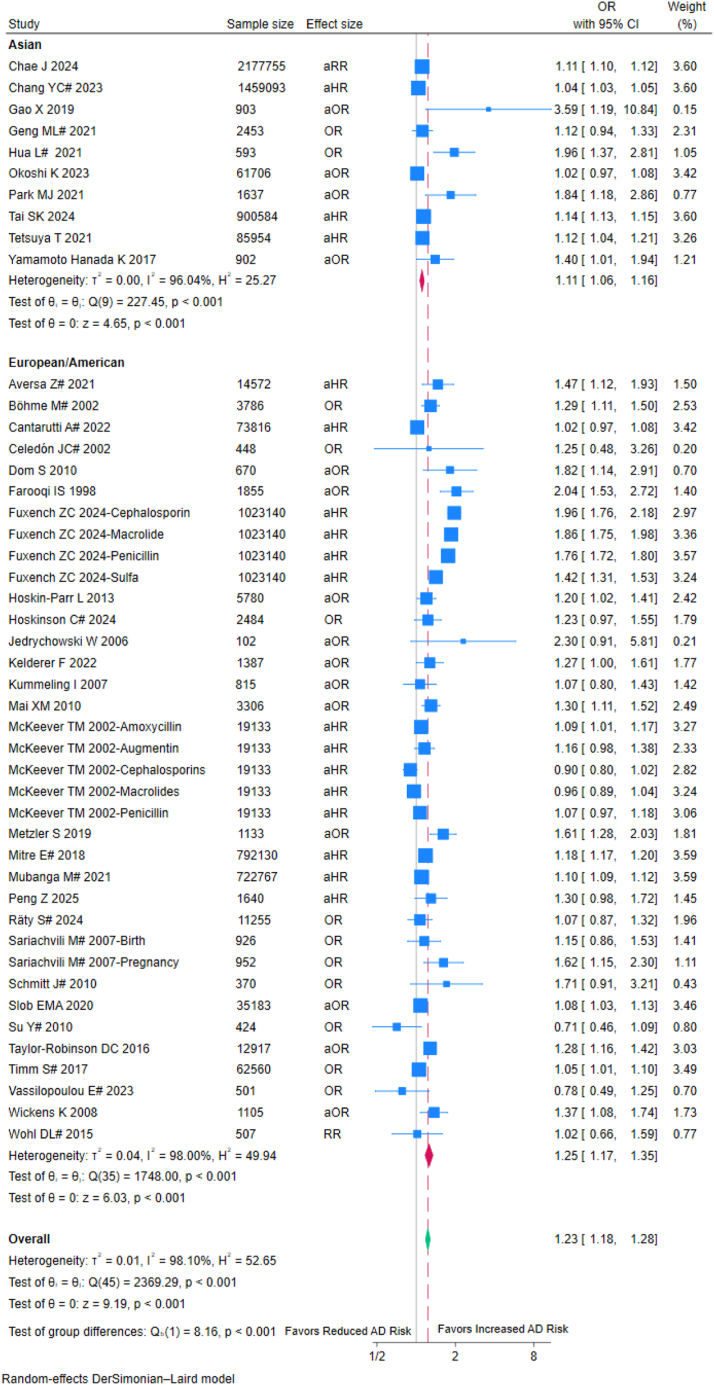

The Asian population exhibited a lower increase in AD risk (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.06–1.16; I2 = 96.04%) compared to the European/American population (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.17–1.35; I2 = 98.00%) (Fig. 5). The between-group difference test suggested that race may moderate the association between antibiotics and AD (p for interaction <0.001). Other racial groups were not included in the analysis due to insufficient studies.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on races. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; #: externally adjusted OR.

Subgroup analysis based on living environment

Antibiotic exposure was associated with a moderately higher risk of AD in rural areas (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.27–1.86; I2 = 14.12%) compared to that in urban areas (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.19–1.48; I2 = 98.51%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p for interaction = 0.21) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on living environment. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; #: externally adjusted OR.

Subgroup analyses based on antibiotic exposure frequency

The risk of AD in children with 1–2 times antibiotics exposure (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.16; I2 = 95.98%) was lower than that in children with 3 or more times antibiotics exposure (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.07–1.47; I2 = 84.27%). Cumulative exposure demonstrated gradient effects but the difference did not reach significance (p for interaction = 0.08) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on antibiotic exposure frequency. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; #: externally adjusted OR.

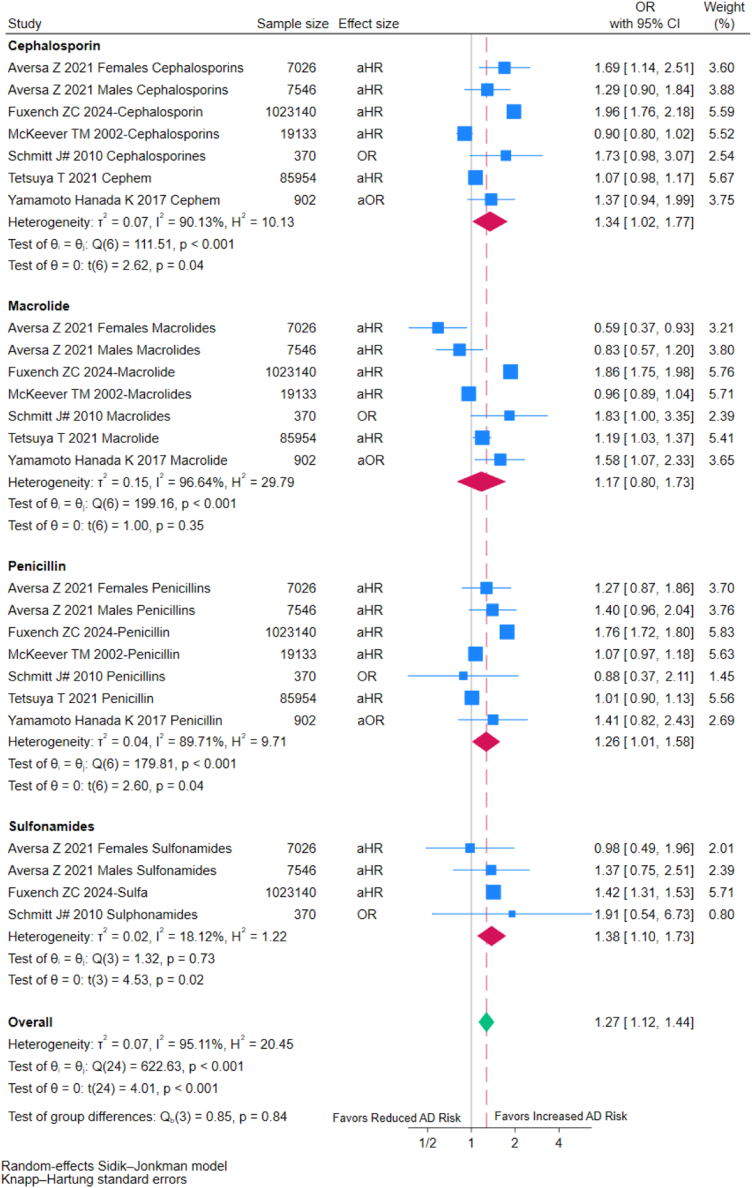

Subgroup analysis based on type of antibiotics

Individuals exposed to cephalosporins (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.02–1.77; I2 = 90.13%), penicillins (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.01–1.58; I2 = 89.71%), and sulfonamides (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.10–1.73; I2 = 18.12%) exhibited increased AD risks. Individuals exposed to macrolides showed no clear association with AD risks (OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.80–1.73; I2 = 96.64%) (Fig. 8). The differences in effect size among the four antibiotic groups were not statistically significant (p for interaction = 0.84).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis based on type of antibiotics. OR: Odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; RR: Risk ratios; aRR: Adjusted risk ratios; aHR: Adjusted hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; #: externally adjusted OR.

Meta-regression

Random-effects univariable meta-regression using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator was conducted to assess associations between continuous moderators and effect sizes (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table S3). Three pre-specified covariates (age of exposure, age of outcome measure, and NOS) were examined. A statistically significant positive association was observed between age of outcome measure and the log-transformed effect estimates (β = 0.028, 95% CI: 0.009–0.048, p = 0.005; I2 = 97.57%, R2 = 0.00%). In contrast, no significant associations were found for the NOS score (β = −0.015, 95% CI: −0.073 to 0.043, p = 0.62; I2 = 97.63%, R2 = 0.00%) or age of exposure (β = −0.008, 95% CI: −0.089 to 0.073, p = 0.86; I2 = 96.40%, R2 = 13.28%). Multivariable meta-regression was not conducted due to the limited heterogeneity accounted for by covariates. Standardized residuals from the meta-regression models (NOS score, age of exposure, age of outcome measurement) were randomly distributed around zero (Supplementary Figure S10 A–C), with no evidence of nonlinear trends, heteroscedasticity, or systematic deviations, supporting linear relationships between predictors and effect sizes. Q–Q plots (Supplementary Figure S10 D–F) confirmed residual normality, showing only marginal tail deviations, validated the meta-regression linear assumptions.

Fig. 9.

Random-effects meta-regression of log (odds ratios) against (A) age of outcome measure (B) age of exposure, and (C) NOS score for the risk of childhood AD after antibiotic exposure. OR: Odds ratio.

Sensitivity analyses

To evaluate the effect of individual studies on the combined quantitative synthesis of OR and the degree of heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The sensitivity of meta-analysis was evaluated by sequentially excluding individual studies. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, Fuxench ZC 20249 seems to be one of the specific sources of the observed heterogeneity. The association between antibiotic exposure and childhood AD and the difference between subgroups of exposure time remained stable, as the cumulative OR calculated after removing any one of the included studies did not exhibit a meaningful change (Supplementarty Figures S4 and S6). The difference between subgroups of Asian and European/American and the difference between subgroups of exposure time were not robust in sensitivity analyses: after removing Fuxench ZC 2024,9 the interaction effect attenuated (from p = 0.008 to p = 0.089) with broadly overlapped confidence intervals (exposure during pregnancy 95% CI: 1.05–1.13; exposure during childhood 95% CI: 1.09–1.21) (Supplementary Figure S5); the interaction effect attenuated (form p < 0.001 to p = 0.31) with broadly overlapped confidence intervals (Asian 95% CI: 1.06–1.16; European/American 95% CI: 1.10–1.18) (Supplementary Figure S7). The statistical significance for the analyses of cephalosporins (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.93–1.58; heterogeneity: I2 = 80.80%), penicillin (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.96–1.29; heterogeneity: I2 = 52.85%) and sulphonamides (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 0.63–2.50; heterogeneity: I2 = 14.02%) on the risk of childhood AD became non-significant after removing Fuxench ZC 2024 (Supplementary Figure S8). As shown in Supplementary Tables S3–S4, the association between NOS score and log-transformed effect estimates became significant from (β = −0.015, 95% CI: −0.073 to 0.043, p = 0.62) to (β = −0.040, 95% CI: −0.078 to −0.0027, p = 0.036) whereas the association with age of outcome measure became non-significant from (β = 0.028, 95% CI: 0.009–0.048, p = 0.005) to (β = 0.008, 95% CI: −0.003 to 0.020, p = 0.16) after excluding Fuxench ZC 2024.

Publication bias

To evaluate potential publication bias, a funnel plot analysis was conducted with Egger test. As shown in Supplementary Figure S9, the observed asymmetry in the funnel plot raises the possibility of publication bias, although Egger's regression test showed no statistically significant evidence of small-study effects (p = 0.20). This apparent discrepancy suggests that while publication bias cannot be ruled out as a potential contributor to the between-study heterogeneity, other substantive sources of heterogeneity should be considered.

Discussion

Antibiotics play a crucial role in treating bacterial infections and are commonly administered during pregnancy and early childhood.63 However, the impact of antibiotic use during pregnancy and early childhood on AD remains unclear in children. This meta-analysis examined the impact of antibiotic exposure on childhood AD. Based on 39 9,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 included studies with a total of 7,487,925 children, we mainly found that antibiotic exposure during pregnancy up to less than five years post-birth increased the risk of AD occurring within the age range of 0–12 years. Children exposed to antibiotics during childhood had a significantly higher risk of developing AD compared to those exposed during pregnancy. Subgroup analyses and meta-regressions further revealed that: (1) the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure was affected by the diagnostic criteria of AD, and it was notably lower when the ICD code was utilized; (2) The increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure in the European/American population were higher than that in the Asian population; (3) The association between antibiotic exposure and AD risk did not meaningfully differ between rural and urban environments; (4) both the antibiotic exposure frequency and type of antibiotic appear to influence the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure; (5) meta-regressions showed that the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure was not correlated with the age of antibiotic exposure and the NOS of included study, but it was positively related with age of outcome measure. Thus, our results suggest that antibiotic exposure increases the risk of developing childhood AD, especially when exposed in childhood.

Recently, several meta-analyses have been conducted. Because of the limited number of included studies and the existence of heterogeneity, the main results of these meta-analyses are inconsistent.6,7,64 For example, a meta-analysis based on seven studies showed pregnancy antibiotic exposure may increase AD risk in children.6 In contrast, another meta-analysis based on seven studies found no significant link between antibiotic exposure and AD.7 Compared to these previous studies, our meta-analysis included 399,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 studies, and these included studies reported comprehensive baseline characteristics, encompassing diagnostic criteria, race, living environment, age of outcome measure et al. The majority of studies were classified as having high quality, with a NOS score ranging from 7 to 9. Based on these high-quality included studies, our meta-analysis found that the risk of childhood AD in the antibiotic-exposure population was significantly increased when compared with the non-antibiotic-exposure population (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.17–1.28; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.06%).

The effect of antibiotic exposure in childhood (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.16–1.38; heterogeneity: I2 = 97.5%) is associated with an elevated risk of AD, with weaker associations observed for pregnancy antibiotic exposure (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.05–1.12; heterogeneity: I2 = 94.18%). Taken together, our study supports that antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and early childhood increases the risk of AD.

Several subgroup analyses were further conducted in this study to analyze the potential effect modifiers, including exposure time, diagnostic criteria, race, living environment, antibiotic exposure frequency, and the type of antibiotics. The increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure was nearly independent of the diagnostic criteria of AD, although it was lower when the ICD code was utilized. Of note, in situations where diagnostic criteria are not well defined, the diagnosis of AD often relies on questionnaires that depend on maternal recall of physician diagnoses or the child's symptoms. Such recall bias may contribute to an increase in the risk of AD.62 These results suggest that the association between the risk of AD and antibiotic exposure may be influenced by the diagnostic method used for AD, which should be carefully considered in further studies.

The increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure in the European/American population were higher than that in the Asian population. This difference may be attributed to genetic predispositions, environmental influences, dietary habits et al. Of note, breast milk adequately meets the nutritional and immune needs of infants under six months, which may promote a healthy intestinal microecological environment and alleviate the impact of antibiotic exposure on the development of AD.65 Generally, countries in the global south and Southeast Asia tend to breastfeed longer than European/American areas, which might be partly related to the higher risk of AD following antibiotic exposure in European/American population. Besides, sensitivity analysis showed this difference between subgroups of Asian and European/American diminished after removing Fuxench ZC 2024,9 suggesting further study are still need and these interference factors could be further considered.

Compared with living in urban areas, rural environment slightly increased the risk of developing childhood AD after antibiotic exposure to some extent (for rural areas: OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.27–1.86; for the urban areas: OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.19–1.48). Of note, only three included studies were conducted in the rural areas, while 21 included studies in urban areas. The impact of diverse factors between rural and urban environments on allergic diseases, including AD, remains controversial. Contrary to our findings, a study based on the population of South Africa found that the risk of AD onset is higher in urban areas, potentially due to the fact that exposure to livestock in rural environments is the strongest protective factor.37 In urban communities, contact with animals is rare, and cesarean section is an important risk factor. Furthermore, globally, numerous factors have been linked to allergic outcomes, including family size, a family history of allergy and asthma, maternal smoking, cesarean birth, dietary habits, physical activity levels, exposure to vitamin D and sunlight, antibiotic use, and exposure to probiotics and prebiotics. All of these factors are associated with the differing risks of AD in rural and urban areas. Besides, the increased risk of AD following antibiotic exposure seems to be positively correlated with the antibiotic exposure frequency according to the confidence intervals of these effects, which suggest there might be a dose-dependent-like phenomenon.66,67 An increasing number of studies have found that the overuse of antibiotics is more severe in rural areas,68, 69, 70 which may also explain the slightly higher increase of the risk of AD in rural areas. Further research is needed to confirm the impact of living environments on the risk of developing AD.

The risk of AD in individuals may be influenced by exposure to different type of antibiotics, such as macrolides, cephalosporins, penicillins, and sulfonamides. According to a recent study of Fuxench et al., 2024,9 penicillin showed the strongest association with AD for both in utero and childhood exposures. This phenomenon might be related to the different antibacterial spectrum of these antibiotics. Base on limited number of included studies, we preliminarily found the risk of AD in individuals exposed to macrolide was slightly but not significantly higher than that in individuals not exposed (OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.80–1.73), while the risk of AD in individuals exposed to cephalosporins (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.02–1.77), penicillin (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.01–1.58) and sulphonamides (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.10–1.73) was significantly higher than that in individuals not exposed. However, the statistical significance for the analyses of cephalosporins (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.93–1.58), penicillin (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.96–1.29) and sulphonamides (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 0.63–2.50) on the risk of childhood AD became non-significant after removing Fuxench Z 2024.9 Thus, further studies are still warranted to determine the relationship between the exposure of specific type of antibiotic and the risk of AD.

Subgroup analyses showed consistent positive associations between antibiotic exposure and AD risk, though the strength of these associations varied. For example, childhood antibiotic exposure (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.13–1.34) exhibited a stronger association than prenatal exposure (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.05–1.13). The statistically significant 14% absolute OR difference (p for interaction = 0.008) may be related to the enhanced statistical power from the large sample size, the clinical relevance requires cautious interpretation. Future studies should standardize diagnostic criteria and quantify absolute risks to distinguish biologically meaningful gradients from methodological heterogeneity.

Meta-regressions were also conducted in this study, including age of exposure, age of outcome measure, and NOS. The risk of AD following antibiotic exposure was not correlated with the age of exposure, but it was positively correlated with the age of outcome measure. This suggested that the effect of antibiotic exposure on the risk of childhood AD may be a very long-term chronic progression. The previous study55 found that antibiotic exposure was not associated with the development of AD between birth and 15 months, but it was related to AD (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.10–3.05) developing after 15 months and remaining present at 4 years. This suggests that older children may have a higher risk of AD due to early-life antibiotic exposure, which is consistent with our study results. The finding of Johnke et al.71 that infants with persistent sensitization were more likely to have AD than those with transient sensitization may explain that there was a higher risk of AD onset as age increased. Besides, the risk of AD following antibiotic exposure were not correlated with NOS, suggesting the quality of the included studies seems to not affect our findings.

In this meta-analysis, 30 9,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33,35,37,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46,49,52,54,56,57 of the 399,11,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 included studies employed prospective, retrospective, or birth cohort designs that confirming antibiotic exposure preceded AD diagnosis. Additionally, most studies adjusted for potential confounders such as concomitant medications and comorbidities, reducing confounding by indication. However, retrospective studies may still be susceptible to recall bias in exposure assessment. Although the methodological rigor of these studies strengthens causal interpretation, residual confounding remains an inherent limitation of observational study designs that cannot be fully excluded.

Several limitations in our meta-analysis should be considered as follows: (1) Methodological limitations exist in some included samples, such as no randomized selection. (2) The subgroup analysis, especially when based on a limited number of studies (such as rural areas, type of antibiotic), should be interpreted with caution due to the potential for inaccurate estimation of between-study heterogeneity arising from the small sample size of included studies. (3) The potential for selection bias persists due to the inherent language limitations of databases and retrospective evaluation. (4) The pooled estimates are confounded because some individual odds ratios are unadjusted and others are not fully adjusted, such that confounding bias may persist even after applying external estimates for adjustment. Besides, HRs, RRs, and ORs were treated as equivalent measures of risk in this meta-analysis, which may bring biased effect size estimates and misinterpretation. (5) Heterogeneity among studies limited the quality of the evidence and hindered the drawing of strong conclusions. (6) Sensitivity analysis showed that some results, such as race, type of antibiotics, and the age of outcome measure, were sensitive to variations in individual studies, more comprehensive and methodologically robust cohorts are needed for validation.

This meta-analysis indicates that antibiotic exposure during pregnancy or early childhood increases the risk of AD. The risk of childhood AD following antibiotic exposure during pregnancy is lower than that following antibiotic exposure during childhood. The risk of childhood AD following antibiotic exposure were affected by diagnostic criteria, race, antibiotic exposure frequency, type of antibiotics, and age of outcome measure. Given the presence of biases (such as selection bias and publication bias), other potential effect modifiers, and uncontrolled confounding factors, further high-quality research with larger sample sizes is imperative. Future studies should consider variables including different types and dosages of antibiotic exposure, the influence of breast milk, specific conditions in rural areas, and medication compliance.

Contributors

H.Z. and Z.X. developed the study design. H.Z. and Y.L. carried out the systematic search and reviewed to screen relevant studies. Y.L. and W.L. accessed and verified the underlying data. E.J. helped to confirm the extracted data for analysis. C.J. helped to analyze the data. H.Z. and Y.L. analyzed the data and composed the manuscript with feedback from Z.X.

Data sharing statement

Most datasets and study materials are publicly available within the original manuscripts, appendices of the included studies, or the Supplementary Materials of this article. Researchers interested in further discussions or collaborative inquiries are encouraged to contact the corresponding author directly.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and also the authors of all references.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103296.

Contributor Information

Huawei Zhao, Email: zhaohuawei@zju.edu.cn.

Zhenghao Xu, Email: xuzhenghao@zcmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Labib A., Ju T., Yosipovitch G. Emerging treatments for itch in atopic dermatitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(2):338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian J., Zhang D., Yang Y., et al. Global epidemiology of atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. Br J Dermatol. 2023;190(1):55–61. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weidinger S., Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langan S.M., Irvine A.D., Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):345–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao H., Zhou J., Lu H., et al. Azithromycin pretreatment exacerbates atopic dermatitis in trimellitic anhydride-induced model mice accompanied by correlated changes in the gut microbiota and serum cytokines. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;102 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong Y., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Huang R. Maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy and the risk of allergic diseases in childhood: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(3):445–456. doi: 10.1111/pai.13411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang F.Q., Lu C.Y., Wu S.P., Gong S.Z., Zhao Y. Maternal exposure to antibiotics increases the risk of infant eczema before one year of life: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(2):143–151. doi: 10.1007/s12519-019-00301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bath-Hextall F.J., Birnie A.J., Ravenscroft J.C., Williams H.C. Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of atopic eczema: an updated Cochrane review. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(1):12–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuxench Z.C., Mitra N., Del Pozo D., et al. In utero or early-in-life exposure to antibiotics and the risk of childhood atopic dermatitis, a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191(1):58–64. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.R., Jo S.J., Koh S.-J., Park H. Impact of dynamic antibiotic exposure on immune-mediated skin diseases in infants and children: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91(3):562–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKeever T.M., Lewis S.A., Smith C., et al. Early exposure to infections and antibiotics and the incidence of allergic disease: a birth cohort study with the West Midlands General Practice Research Database. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(1):43–50. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaeizadeh G., Mansournia M.A., Keshtkar A., et al. Maternal education and its influence on child growth and nutritional status during the first two years of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;71 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanagaratnam L., Dramé M., Trenque T., et al. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients with cognitive disorders: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2016;85:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penders J., Kummeling I., Thijs C. Infant antibiotic use and wheeze and asthma risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(2):295–302. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00105010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantovani A., Petracca G., Beatrice G., Tilg H., Byrne C.D., Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident diabetes mellitus: an updated meta-analysis of 501 022 adult individuals. Gut. 2021;70(5):962–969. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Röver C., Knapp G., Friede T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:99. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0091-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IntHout J., Ioannidis J.P.A., Borm G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerayeli F.V., Milne S., Cheung C., et al. COPD and the risk of poor outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland S. Quantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literature. Epidemiol Rev. 1987;9 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aversa Z., Atkinson E.J., Schafer M.J., et al. Association of infant antibiotic exposure with childhood health outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1):66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böhme M., Lannerö E., Wickman M., Nordvall S.L., Wahlgren C.F. Atopic dermatitis and concomitant disease patterns in children up to two years of age. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82(2):98–103. doi: 10.1080/00015550252948112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantarutti A., Amidei C.B., Bonaugurio A.S., Rescigno P., Canova C. Early-life exposure to antibiotics and subsequent development of atopic dermatitis. Expet Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2022;15(6):779–785. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2092471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celedón J.C., Litonjua A.A., Ryan L., Weiss S.T., Gold D.R. Lack of association between antibiotic use in the first year of life and asthma, allergic rhinitis, or eczema at age 5 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):72–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chae J., Choi Y.-M., Kim Y.C., Kim D.-S. Quinolone use during the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergies of offspring during 2011 to 2020. Infect Chemother. 2024;56(4):461–472. doi: 10.3947/ic.2024.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang Y.C., Wu M.C., Wu H.J., Liao P.L., Wei J.C. Prenatal and early-life antibiotic exposure and the risk of atopic dermatitis in children: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023;34(5) doi: 10.1111/pai.13959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dom S., Droste J.H.J., Sariachvili M.A., et al. Pre- and post-natal exposure to antibiotics and the development of eczema, recurrent wheezing and atopic sensitization in children up to the age of 4 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(9):1378–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farooqi I.S., Hopkin J.M. Early childhood infection and atopic disorder. Thorax. 1998;53(11):927–932. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.11.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuxench Z.C., Mitra N., Del Pozo D., et al. In utero or early-in-life exposure to antibiotics and the risk of childhood atopic dermatitis, a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2023;191(1):58–64. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao X., Yan Y., Zeng G., et al. Influence of prenatal and early-life exposures on food allergy and eczema in infancy: a birth cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1623-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geng M., Tang Y., Liu K., et al. Prenatal low-dose antibiotic exposure and children allergic diseases at 4 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021:225. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoskin-Parr L., Teyhan A., Blocker A., Henderson A.J.W. Antibiotic exposure in the first two years of life and development of asthma and other allergic diseases by 7.5 yr: a dose-dependent relationship. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(8):762–771. doi: 10.1111/pai.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoskinson C., V. Medeleanu M., Reyna M.E., et al. Antibiotics taken within the first year of life are linked to infant gut microbiome disruption and elevated atopic dermatitis risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(1):131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hua L., Chen Q., Liu Q.H., et al. Interaction between antibiotic use and MS4A2 gene polymorphism on childhood eczema: a prospective birth cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):314. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02786-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jędrychowski W., Gałaś A., Whyatt R., Perera F. The prenatal use of antibiotics and the development of allergic disease in one year old infants. A preliminary study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2006;19(1) doi: 10.2478/v10001-006-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelderer F., Mogren I., Eriksson C., Silfverdal S.A., Domellöf M., West C.E. Associations between pre- and postnatal antibiotic exposures and early allergic outcomes: a population-based birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(9) doi: 10.1111/pai.13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kummeling I., Stelma F.F., Dagnelie P.C., et al. Early life exposure to antibiotics and the subsequent development of eczema, wheeze, and allergic sensitization in the first 2 years of life: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e225–e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levin M.E., Botha M., Basera W., et al. Environmental factors associated with allergy in urban and rural children from the South African Food Allergy (SAFFA) cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mai X.M., Kull I., Wickman M., Bergström A. Antibiotic use in early life and development of allergic diseases: respiratory infection as the explanation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(8):1230–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Metzler S., Frei R., Schmaußer-Hechfellner E., et al. Association between antibiotic treatment during pregnancy and infancy and the development of allergic diseases. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(4):423–433. doi: 10.1111/pai.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitre E., Susi A., Kropp L.E., Schwartz D.J., Gorman G.H., Nylund C.M. Association between use of acid-suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(6) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mubanga M., Lundholm C., D'Onofrio B.M., Stratmann M., Hedman A., Almqvist C. Association of early life exposure to antibiotics with risk of atopic dermatitis in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okoshi K., Sakurai K., Yamamoto M., et al. Maternal antibiotic exposure and childhood allergies: the Japan Environment and Children's Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;2(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jacig.2023.100137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park M.J., Lee S.Y., Lee S.H., et al. Effect of early-life antibiotic exposure and IL-13 polymorphism on atopic dermatitis phenotype. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(7):1445–1454. doi: 10.1111/pai.13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng Z., Siziba L.P., Brenner H., Wernecke D., Rothenbacher D., Genuneit J. Changes in childhood atopic dermatitis incidence and risk factors over time: results from two German birth cohorts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2025;55(6):469–480. doi: 10.1111/cea.70066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raty S., Ollila H., Turta O., et al. Neonatal and early infancy antibiotic exposure is associated with childhood atopic dermatitis, wheeze and asthma. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183(12):5191–5202. doi: 10.1007/s00431-024-05775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sariachvili M., Droste J., Dom S., et al. Is breast feeding a risk factor for eczema during the first year of life? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(5):410–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmitt J., Schmitt N.M., Kirch W., Meurer M. Early exposure to antibiotics and infections and the incidence of atopic eczema: a population-based cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2p1):292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slob E.M.A., Brew B.K., Vijverberg S.J.H., et al. Early-life antibiotic use and risk of asthma and eczema: results of a discordant twin study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02021-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su Y., Rothers J., Stern D.A., Halonen M., Wright A.L. Relation of early antibiotic use to childhood asthma: confounding by indication? Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(8):1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tai S.K., Lin Y.H., Lin C.H., Lin M.C. Antibiotic exposure during pregnancy increases risk for childhood atopic diseases: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s40001-024-01793-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor-Robinson D.C., Williams H., Pearce A., Law C., Hope S. Do early-life exposures explain why more advantaged children get eczema? Findings from the U.K. Millennium Cohort Study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(3):569–578. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuchida T., Yoshida S., Takeuchi M., Kawakami K. Large-scale health insurance study showed that antibiotic use in infancy was associated with an increase in atopic dermatitis. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111(3):607–613. doi: 10.1111/apa.16221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timm S., Schlünssen V., Olsen J., Ramlau-Hansen C.H. Prenatal antibiotics and atopic dermatitis among 18-month-old children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(7):929–936. doi: 10.1111/cea.12916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emilia V., Dimitrios R., Gregorio Paolo M., et al. Nurturing infants to prevent atopic dermatitis and food allergies: a longitudinal study. Nutrients. 2023;16(1):21. doi: 10.3390/nu16010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wickens K., Ingham T., Epton M., et al. The association of early life exposure to antibiotics and the development of asthma, eczema and atopy in a birth cohort: confounding or causality? Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(8):1318–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wohl D.L., Curry W.J., Mauger D., Miller J., Tyrie K. Intrapartum antibiotics and childhood atopic dermatitis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(1):82–89. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.01.140017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto-Hanada K., Yang L., Narita M., Saito H., Ohya Y. Influence of antibiotic use in early childhood on asthma and allergic diseases at age 5. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(1):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong S.H., Tan Z.Y.A., Cheng L.J., Lau S.T. Wearable technology-delivered lifestyle intervention amongst adults with overweight and obese: a systematic review and meta-regression. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bennette C., Vickers A. Against quantiles: categorization of continuous variables in epidemiologic research, and its discontents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schoch J.J., Satcher K.G., Garvan C.W., Monir R.L., Neu J., Lemas D.J. Association between early life antibiotic exposure and development of early childhood atopic dermatitis. JAAD Int. 2023;10:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2022.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vance T.M., Li T., Cho E., Drucker A.M., Camargo C.A., Qureshi A.A. Prenatal antibiotic use and subsequent risk of atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(4):561–563. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljac108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nogacka A.M., Salazar N., Arboleya S., et al. Early microbiota, antibiotics and health. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2670-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duong Q.A., Pittet L.F., Curtis N., Zimmermann P. Antibiotic exposure and adverse long-term health outcomes in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2022;85(3):213–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Volery M., Scherz V., Jakob W., et al. Study protocol for the ABERRANT study: antibiotic-induced disruption of the maternal and infant microbiome and adverse health outcomes - a prospective cohort study among children born at term. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mansournia M.A., Nazemipour M. Recommendations for accurate reporting in medical research statistics. Lancet. 2024;403(10427):611–612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenland S., Mansournia M.A., Joffe M. To curb research misreporting, replace significance and confidence by compatibility: a Preventive Medicine Golden Jubilee article. Prev Med. 2022;164 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dyar O.J., Yang D., Yin J., Sun Q., Stålsby Lundborg C. Variations in antibiotic prescribing among village doctors in a rural region of Shandong province, China: a cross-sectional analysis of prescriptions. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devine P., O'Kane M., Bucholc M. Trends, variation, and factors influencing antibiotic prescribing: a longitudinal study in primary care using a multilevel modelling approach. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;11(1) doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Z., Hu Y., Zou G., et al. Antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory infections among children in rural China: a cross-sectional study of outpatient prescriptions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1287334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnke H., Norberg L.A., Vach W., Host A., Andersen K.E. Patterns of sensitization in infants and its relation to atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17(8):591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.