Abstract

Following the evolution of the composition of the atmosphere informs on the entire geological evolution of our planet. The discovery that Archean atmospheric xenon was isotopically fractionated compared to modern atmospheric xenon paved the way for using this noble gas as a tracer of hydrogen escape on the primitive Earth. The curve of the evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon remains, however, poorly defined. Recent studies proposed that the evolution was discontinuous with brief episodes of escape and fractionation of xenon separated by up to several 100 Ma long pauses. Similarly, some major unknowns remain regarding the progressive depletion of xenon in the atmosphere due to the proposed escape mechanism. In this study, we report the noble gas elemental ratios and isotopic compositions of noble gases released from a ca. 3.48 Ga old barite sample from the Dresser Formation (North Pole, Australia) by stepwise crushing in high vacuum. All samples released xenon enriched in light isotopes relative to heavy isotopes compared to modern atmospheric xenon but with various degrees of isotopic fractionation. Krypton is enriched in heavy isotopes relative to light isotopes in some crushed samples. After correction for Kr and Xe loss, results show that 3.48 Ga ago atmospheric xenon was fractionated by −19.1 ± 1.8‰ per atomic mass unit (u–1). This value is more negative than that reported previously for 3.3 Ga old atmospheric xenon. A new curve for the evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon is proposed. Xenon is also enriched relative to Kr in the gas released from the measured samples. While this is consistent with the scenario of a progressive selective escape of xenon from the Archean atmosphere, the exact abundance of Xe in the paleoatmosphere remains elusive.

Keywords: atmosphere, habitability, noble gases, geochemistry, fluid inclusions, Archean

Introduction

The habitability of a planet strongly relies on the pressure, temperature, and composition of its surface or subsurface. The atmosphere surrounding primitive Earth had a chemical (and isotopic) composition drastically different from the modern. The composition of the atmosphere evolved over Gyr time scales under the influence of controlling parameters either internal (e.g., magmatic degassing, biological activity) or external (solar irradiation) to the planetary body. For a given atmospheric constituent, changes might have been progressive or brutal, depending on the relative fluxes controlling its abundance. The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) is one turning point in Earth’s history. It happened about 2.3–2.4 Ga ago and corresponds to a transition from low (O2 < 1 ppmv) to higher partial pressures of O2. The causes of the GOE remain debated. Recent works proposed that changes in the tectonic regime of ancient Earth coupled with biogeochemical cycles led to the oxygenation of the Earth’s surface. , Other models propose that deep Earth played an important role, inducing changes in the oxidation state of silicate Earth or modulating the redox state of magmatic gases emitted at the Earth’s surface. , Escape of hydrogen could also have contributed to the rise of atmospheric O2 , but the history of hydrogen escape is not easily trackable in the geological record.

Recent studies reported that the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon evolved during the Archean and reached modern-like values only around the time of the GOE. − This evolution could be due to protracted escape of Xe ions from the Archean atmosphere to outer space fueled by the concomitant escape of hydrogen ions. In this model of hydrodynamic escape, xenon leaves the atmosphere, but this process depends on the mass of the escaping isotope and escape is more efficient for lighter isotopes. Escape of xenon through this process naturally leads to a progressive enrichment in heavy isotopes of the remaining fraction of atmospheric xenon. The escape of xenon ions would thus have contributed to both the depletion and the isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon, a promising solution for the so-called “xenon paradox”. The evolution of the isotopic composition of paleoatmospheric xenon is thus a potential tracer of the escape of hydrogen from the Archean atmosphere, implying that hydrogen escape played a significant role in the GOE. ,, A preliminary modeling study of the escape mechanism concluded that Xe escape must have been limited to short episodes in order to fit constraints on the Kr/Xe ratio and on the proportion of 244Pu-derived fission xenon in the atmosphere. Existing geochemical studies tend to confirm that the evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon was discontinuous and shows a plausible plateau in isotopic composition for about 600 Myr (between 3.3 and 2.7 Ga ago). , Such a plateau in the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon could reflect a long pause in the escape of xenon for a variety of possible reasons: there was not enough hydrogen in the atmosphere, the transport mechanism to bring xenon at high altitude was not operating or not efficient enough, the strength and/or shape of the magnetic field prevented xenon escape, or solar luminosity was not high enough to ionize xenon in significant quantities. Confirming the existence of this isotopic plateau and its duration is thus important to better understand the atmosphere surrounding Archean Earth and the parameters controlling its evolution. Interestingly, there is no agreement on the magnitude of the isotopic fractionation of xenon in the oldest paleoatmosphere ever detected.

Most of the existing data on the evolution of the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere have been acquired by analyzing gases contained in fluid inclusions trapped in hydrothermal quartz crystals. − ,,,,, However, the oldest record of atmospheric xenon comes from measurements of xenon contained in 3.5 Ga old barite samples. A first study reported an isotopic fractionation of −13.7‰ u–1 for Xe contained in barites from North Pole (Australia) and attributed this fractionation to mass-dependent fractionation of atmospheric xenon at the time of entrapment of xenon in the barite sample. A subsequent study confirmed the presence of fractionated xenon in Archean barites but measured a higher fractionation (in absolute value) reaching −21 ± 3‰ u–1. They considered first that fractionation occurred by mutual diffusion coupled with Rayleigh distillation during the entrapment of fluids but revisited this interpretation later on and concluded that Archean atmospheric xenon was presenting a mass-dependent fractionation relative to modern air. Recently, a study focused on the abundance and isotopic composition of xenon in a set of barite crystals with estimated ages ranging from 3.5 Ga to 1.8 Ga. Unfortunately, measurements of the 3.5 Ga old barite sample did not reveal the presence of a paleoatmospheric component. The exact absolute magnitude of isotopic fractionation of Xe in the 3.5 Ga old atmosphere remains thus uncertain (−13.7‰ u–1 vs −21‰ u–1), although it is crucial to determine the extent of fractionation of the oldest paleoatmospheric Xe signal ever detected in the Earth rock record. Knowing this value would allow determining the true duration of the isotopic plateau suggested in previous works. ,

Additionally, the abundance of xenon in the Archean paleoatmosphere is a matter of debate. The long-term evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon should be accompanied by a concomitant progressive depletion in this noble gas relative to others. Note, however, that isotopic evolution and elemental depletion do not need to be perfectly synchronized contrary to what was suggested by simplistic previous approaches. ,, Depending on the exact regime of escape, xenon can be efficiently removed from the Earth’s atmosphere without significant isotopic fractionation or it can be barely escaping but the escape mechanism can fractionate isotopes efficiently. While atmospheric xenon is clearly depleted by a factor of about 20 relative to potential chondritic cosmochemical sources, it is difficult to demonstrate that paleoatmospheric xenon was in an intermediate situation. A recent study by Broadley et al. reported elevated Xe/Kr ratios measured for ca. 3.3 Ga old Barberton quartz samples, demonstrating that 3.3 Ga ago, the Archean atmosphere was indeed enriched in xenon relative to the modern atmosphere. However, the exact Xe/Kr ratio the paleoatmosphere remains elusive given the fact that the fluids contained in the samples analyzed in this aforementioned study consist in mixture between paleoatmospheric and hydrothermal fluid, both containing Kr and Xe in unknown relative proportions. Furthermore, while isotopic ratios of noble gases are not significantly altered when noble gases dissolve in water with different temperatures and salinity, elemental ratios can be heavily fractionated, making it challenging to draw conclusions on the elemental ratios of the original paleoatmosphere.

In this study, we measured the elemental and isotopic composition of neon, argon, krypton and xenon contained in fluid inclusions trapped in ca. 3.48 Ga old barite crystals from the Dresser Formation (Australia). Noble gas isotope systematics are used to demonstrate the strong atmospheric affinity of the fluid and to precisely determine the degree of isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon around 3.5 Ga ago. Measured elemental ratios are in line with a higher abundance of xenon in the Archean atmosphere, supporting the scenario of a prolonged selective escape of xenon from the Earth’s atmosphere.

Samples and Analytical Methods

Geological Context and Samples

Analyzed barite crystals come from a freshly exposed cut wall in the Dresser mine (21° 09′ 05.2″ S, 119° 26′ 15.3″ E, Dresser Formation, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia). Field descriptions and petrographic characterization of the barite samples and of their fluid inclusion assemblages have already been reported elsewhere , and only observations relevant to the present study are reported below. Barites measured in this study display coarse crystalline textures and are distributed in 2–10 cm thick units interbedded with stromatolites. Several studies proposed that these barites were precipitated in a surface environment influenced by hydrothermal activity. ,− The fact that adjacent stromatolites are not replaced by barites and the absence of relicts of precursor minerals within the barite crystals argue in favor of a primary origin of the barite units (see ref and refs therein). Most fluid inclusions in barites are oriented parallel to plane of crystal growth. There are two types of fluid inclusions in the barite crystals: aqueous carbonic-sulfidic and nonaqueous carbonic–sulfidic inclusions. Total homogenization temperatures range from 100 to 195 °C. Mißbach et al. concluded that most fluid inclusions of the two types are primary and reflect the presence of two immiscible fluids at the time of entrapment. Only few secondary inclusions were identified. The exact origin of the fluids trapped inside fluid inclusions remains elusive. However, the presence of organic material inside the chert and barite veins suggests that organic matter, probably of biological origin, has been remobilized and redistributed by hydrothermal fluids (“hydrothermal pump”). ,

Barites from the Dresser Formation were probably deposited ca. 3.48 Ga ago. This age corresponds to U–Pb dating of a felsic volcaniclastic tuff in the upper part of the unit as maximum deposition age (3481 ± 4 Ma; ref ). This unit is not affected by the widespread episode of felsic activity 3.47–3.46 Ga ago, thus providing a minimum age constraint.

Analytical Methods

Noble gases contained in fluid inclusions were extracted from barite samples by crushing in vacuum conditions using the same analytical procedure that the one described use in a previous study. Reactive molecules (e.g., H2O, N2, and H2S) were sequentially purified on three getters: one made of Zr–V–Fe pellets (5 min at 300 °C, 10 min at room temperature) and two made of Ti-sponge (5 min at 600–700 °C, 10 min at room temperature). All noble gases, except helium, were trapped on a charcoal cooled down to 25 K. Noble gases were then released by increasing the temperature of the charcoal trap, exposed to a cold D50 CapaciTorr getter, trapped on a charcoal closer to the inlet valve of the mass spectrometer and then sequentially admitted into the instrument. Samples were measured during two analytical sessions using two different noble gas mass spectrometers although the purification and gas separation procedures remain the same. Noble gas contained in samples 1–5 have been analyzed using a Noblesse mass spectrometer equipped with one faraday cup and three electron multipliers. Neon and argon isotopes were detected in multicollection modes with electron multipliers for 20–22Ne and 36,38Ar and with a Faraday cup for 40Ar. Krypton and xenon isotopes were detected in peak-jumping mode using one electron multiplier. For sample 6, noble gases were measured using a new Noblesse mass spectrometer equipped with three Faraday cups and six electron multipliers. Neon and argon were detected in multicollection mode, krypton in partial multicollection (three mass jumps) and xenon in partial multicollection (two mass jumps). For the two analytical sessions, the contributions from doubly charged 40Ar2+ and 44CO2 +2 to the signals of 20Ne and 22Ne were corrected using double ionization ratios and measurements of 40Ar and 44CO2 signals during the measurement of neon.

For the two analytical sessions, sensitivity and reproducibility of the instrument were assessed by measuring aliquots of a standard bottle containing diluted ambient air. All data were corrected for blank contributions, mass discrimination of the instrument, and errors were fully propagated. For sample 6, the abundance of krypton (84Kr) is reported but not its isotopic composition due to improper source tuning inducing uncontrolled mass-independent variations and leading to erroneous isotopic compositions.

Results

All results are listed in the table in the Supporting Information, and errors are given with 1σ uncertainty. Results are also available on IPGP Research Collection (https://doi.org/10.18715/IPGP.2025.ma15g91m).

Abundances

Abundances of noble gases released during the crushing experiments are reported in the table in the Supporting Information. Elemental ratios relative to 36Ar and to the composition of the modern atmosphere (F values) are displayed in Figure . Overall, the gas released from fluid inclusions during the crushing experiment is depleted in light (Ne) noble gases relative to heavy ones (Kr and Xe). For neon and krypton, F values are intermediate between values of noble gases contained in air and dissolved in waters (meteoric water, seawater, or bittern brine; see ref ). Most F values for Xe are higher than the water endmembers described above suggesting that the fluid trapped in fluid inclusions is enriched in Xe.

1.

Elemental abundances of noble gases released from the barite samples. Abundances are displayed using the F value defined by F = (X/36Ar)sample/(X/36Ar)air, with X being 20Ne, 84Kr, or 130Xe. Box and whisker plots showing the minimum and maximum values (whiskers) together with the median, lower and upper quartile (box) are used to represent the variability of the data set. Elemental fractionation patterns for noble gases dissolved in meteoric water (0 °C), seawater (25 °C), and bittern brine (evaporated seawater, 29 °C) are shown for comparison (ref and refs therein).

Isotopic Compositions

For neon, 20Ne/22Ne ratios are dispersed around the atmospheric value (9.81,) and range from 9.52 ± 0.07 to 10.27 ± 0.08. The 21Ne/22Ne ratios are all higher than the value of atmospheric neon (0.029) and range from 0.0332 ± 0.0008 to 0.0754 ± 0.0011. In the 20Ne/22Ne–21Ne/22Ne isotope space, most crushing steps for samples 1–5 define a broad horizontal trend going from air to a component enriched in 21Ne (Figure ). For sample 6, crushing steps define a trend with a 20Ne/22Ne ratio lower than 9.7 for a 21Ne/22Ne ratio of 0.029.

2.

Three isotope diagram of neon isotopes measured in the barite samples. Crushing steps define a broad trend toward an endmember with high 21Ne/22Ne ratios although the 20Ne/22Ne ratios are variable. The dashed line corresponds to crustal neon defined by Kennedy from data obtained on crustal gases. The plain line corresponds to the nucleogenic mixing line defined by Holland et al. for ancient fluids. The horizontal dotted line is for a 20Ne/22Ne ratio of 9.8. The hatched area reflects possible mixing ranges between air and mantle neon either from OIB or MORB mantle reservoirs. The red line and light red range show the linear regression and associated one sigma error range for crushing steps of sample 6. Errors are at 1σ.

For argon, the 38Ar/36Ar ratios range from 0.1847 ± 0.0015 (second crushing step of sample 4) to 0.1914 ± 0.0021 (fifth crushing step of sample 6). The 38Ar/36Ar ratios of total argon released from the sample are identical within uncertainties to the isotopic composition of modern atmospheric argon for samples 2, 3, 4, and 6 (Figure ). The 38Ar/36Ar ratio of total argon released from sample 1 is slightly lower than the atmospheric value. For sample 5, the ratio (0.1895 ± 0.001) is only slightly above the atmospheric value of 0.188. For all crushing steps, the 40Ar/36Ar ratios are higher than atmospheric argon and range from 1344 ± 5 (first crushing step of sample 6) to 3293 ± 13 (last crushing step of sample 6). For all samples, 40Ar/36Ar continuously increase when crushing proceeds (Figure ) except for the fifth crushing step of sample 2 which gives a 40Ar/36Ar ratio of 2659 ± 14, lower than the previous crushing step (2802 ± 12). Interestingly, when 21Ne/22Ne and 40Ar/36Ar ratios are combined, data define mixing hyperbolae between air and an endmember with elevated 21Ne/22Ne and 40Ar/36Ar ratios (Figure ). The fact that mixing hyperbolae are rather well-defined (see for example samples 1, 3, and 6) suggests that gases trapped in the barite consist of a mixture between crustal-derived gases and an atmospheric component representing modern and/or paleoatmosphere.

3.

38Ar/36Ar ratios measured in the barite samples. Data points are organized vertically with the crushing steps going from bottom to top. Each crushing step is displayed with a data point accompanied by its respective error bars. The 38Ar/36Ar ratio of total argon released for each sample is represented with a color range. The value for atmospheric argon is shown with its error range (dashed lines) because the uncertainty on the isotopic composition of atmospheric argon (38Ar/36Ar = 0.1880 ± 0.0004;) was not part of the error propagation computed for the data set. All errors are at 1σ.

4.

40Ar/36Ar ratios of argon released from fluid inclusions during the crushing experiment. The 40Ar/36Ar ratio increases during the crushing experiment (except for the last crushing step on sample 2). Error bars are smaller than the symbol sizes.

5.

Mixing hyperbolae defined by crushing steps in the 40Ar/36Ar vs 21Ne/22Ne space. Dashed curves represent mixing hyperbolae for samples 1, 3, and 6 computed using the same code as the one developed in a previous study. For 40Ar/36Ar ratios, error bars are smaller than the symbol sizes.

The isotopic composition of krypton released from five of the six different barite subsamples is displayed in Figure . Krypton in sample 5 has an isotopic composition indistinguishable from the one of modern atmospheric krypton. For all other samples, krypton shows isotopic deviations relative to atmospheric krypton. For sample 3, the isotopic composition defines a clear mass-dependent fractionation trend in favor of heavy isotopes relative to light ones. This corresponds to an isotopic fractionation (δKr) of 3.74 ± 0.79 permil per atomic mass unit (‰ u–1). Krypton contained in sample 4 might also present such a mass-dependent fractionation in favor of heavy isotopes if one considers that 78Kr and 80Kr signals could have been polluted by hydrocarbons (C6H6) and interfering 40Ar, respectively. However, it is worth noting that argon released from sample 4 does not show a particularly high 40Ar/36Ar ratio (2052 ± 14) relative to other samples. The isotopic fractionation computed using 82,83,86Kr isotopes and ignoring 78Kr and 82Kr, reaches 8.4 ± 2.6‰ u–1. Kr in sample 1 presents an excess in 78Kr and depletions in 82Kr and 86Kr relative to air. Kr in sample 2 is almost air-like except for an enrichment of 15 ± 7‰ for 78Kr and a slight depletion of −3.3 ± 2.9‰ for 86Kr.

6.

Isotopic composition of total krypton released from barite samples 1–5. The isotopic composition is expressed using the delta notation which corresponds to a permil deviation relative to the isotopic composition of modern atmospheric krypton with 84Kr being the normalizing isotope. Errors are at 1σ.

All crushing steps on all sample duplicates released xenon with an isotopic composition clearly distinct from modern atmospheric xenon (Figure ). A first order observation is that xenon in the barite samples is enriched in light isotopes and depleted in heavy isotopes relative to air. For each sample, delta values for 124Xe,126Xe, 128Xe, and 131Xe (normalized to 132Xe) follow a mass-dependent fractionation trend, computed with the IsoplotR software, with fractionations ranging from −16.2 ± 1.9‰ u–1 for sample 5 and up to −21.8 ± 1.1‰ u–1 for sample 2 (table in the Supporting Information). 130Xe seems to be enriched relative to the mass-dependent fractionation line with a clear excess identified for xenon released for sample 6 (Figure ). 134Xe and 136Xe are enriched relative to the mass-dependent fractionation line identified with light xenon isotopes. Relative excesses of 134Xe and 136Xe on top of mass-dependent fractionation are compatible with the contribution from fissiogenic Xe produced by the spontaneous fission of 238U, although the precision of the data set does not fully exclude a contribution from now extinct 244Pu (Figure ).

7.

Isotopic composition of total xenon released from barite samples 1–6. The isotopic composition is expressed using the delta notation which corresponds to a permil deviation relative to the isotopic composition of modern atmospheric xenon with 132Xe being the normalizing isotope. Errors are at 1σ.

8.

Three-isotope diagram of xenon isotopes showing the effect of addition of fissiogenic xenon derived either from the spontaneous fission of 244Pu or from 238U to a starting atmospheric composition with a ∼20‰ u–1 mass-dependent fractionation of xenon in favor of light Xe isotopes. Colored symbols represent the isotopic composition of total xenon released for each sample. Colored lines correspond to mixing lines between fractionated air (∼20‰ u–1) and xenon produced during the spontaneous of 238U (orange plain line) and 244Pu (dashed green line).

Discussion

Mixing between Crustal Gases and a Paleoatmospheric Endmember

Neon and argon results obtained in this study suggest that the fluid trapped in the studied barite samples consists in a mixture between an atmospheric endmember and a crustal endmember enriched in nucleogenic neon and radiogenic argon (Figure ). Elevated 21Ne/22Ne ratios are commonly found in fluids derived from crustal rocks. − Nucleogenic neon isotopes (20,21,22Ne) are produced in the crust by nuclear reactions between alpha particles and neutrons on target elements such as O, F and Mg. − Most of the time, nucleogenic neon presents high 21Ne/22Ne and low 20Ne/22Ne ratios. If only one nucleogenic endmember is involved, crushing steps define mixing lines between air and the nucleogenic endmember with a slope corresponding to a given O/F ratio, F being the main contributor to nucleogenic 22Ne40. In the present study, no clear mixing trend can be identified in the Ne three-isotope plot (Figure ). Data plot close but above the “Archean neon mixing line” defined by Holland et al. which reflects a mixing line between air–Ne and the pure nucleogenic neon endmember predicted for average crustal O/F ratios. , It is worth noting here that nucleogenic excesses measured in the present study are small. The highest 21Ne/22Ne ratio is only 0.0754 (last crushing step on sample 6) while neon released from fluid inclusions contained in Archean quartz samples can have 21Ne/22Ne ratio up to 0.58 (see ref ). In our study, neon often presents a 20Ne/22Ne ratio higher than 9.8, the value of modern atmospheric neon. The maximum measured 20Ne/22Ne ratio is 10.27 ± 0.08 (first crushing step of sample 4). Such high 20Ne/22Ne ratios are striking, given the fact that in common modern crustal settings, nucleogenic neon systematically presents low 20Ne/22Ne ratios because the production rates of 22Ne by interaction between alpha particles and fluorine atomic nuclei is larger than the production rate of 20Ne. To our knowledge, the only way to produce nucleogenic neon with elevated 21Ne/22Ne and relatively minor changes of 20Ne/22Ne ratios is through negligible production of 22Ne via the aforementioned nuclear reactions. This would be possible if the crustal minerals in which nucleogenic neon was produced has very high O/F ratio. Barites (BaSO4) are rich in oxygen. Interestingly, previously reported chemical measurements of rocks from the Dresser Formation did not detect fluorine in the measured barite samples, suggesting that nucleogenic neon production in such samples would have high 20Ne/22Ne ratios. Nonetheless, nucleogenic production of neon, even in the absence of fluorine, leads to much more 21Ne production than that of 20Ne via alpha reactions on oxygen nuclei, giving almost flat lines in Figure . For these reasons, we cannot exclude that some minor mantle component, carrying a solar-derived signature, contributed to the budget of neon contained in fluid inclusions of the barite samples measured in this study. For sample 6, crushing steps define a linear trend which gives a 20Ne/22Ne ratio of only 9.67 ± 0.03 for a 21Ne/22Ne ratio of 0.029. This value is lower than for modern atmospheric neon (20Ne/22Ne = 9.8). A low atmospheric 20Ne/22Ne ratio in the Archean is compatible with predictions from a recent model of degassing of solar neon in an originally chondritic atmosphere. However, the fact that crushing steps on other samples do not show the presence of this component with a low 20Ne/22Ne ratio and the uncertainties regarding the origin of the nucleogenic component having high 20Ne/22Ne ratios prevent us from providing the value of the 20Ne/22Ne ratio of the 3.5 Ga old atmosphere trapped within the barite samples measured in this study.

Fractionated Krypton and the True Isotopic Composition of 3.5 Ga Old Paleoatmospheric Xenon

Krypton released from samples 1 to 4 presents varying degrees of isotopic fractionation relative to modern atmospheric krypton (Figure ). Kr in samples 1 and 2 is enriched in light Kr isotopes relative to heavy ones while Kr in samples 3 and 4 presents an enrichment in heavy isotopes relative to light ones. Mass-dependent fractionation of Kr (δKr) is nicely defined for sample 3 (+3.7 ± 0.8‰ u–1; Figure ). To our knowledge, this is the first time that fractionated krypton is clearly detected in crustal fluids trapped in fluid inclusions in hydrothermal minerals. Interestingly, for sample 3, fractionated Kr is accompanied by xenon presenting an isotopic fractionation (δXe) of −16.1 ± 1.2‰ u–1, lower in absolute magnitude than for other samples (average value of −19.1 ± 2.0‰ u–1 for samples 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6). We corrected the isotopic composition of xenon in sample 3 with the assumption that Kr and Xe in sample 3 have been affected by the same mass-dependent fractionation mechanism and that the original isotopic composition of Kr was modern-like. Note, however, that the exact mechanism responsible for the fractionation of Kr (and Xe) in the samples analyzed in this study remains elusive. The result of the applied correction using a fractionation law proportional to the square root of the mass (m 1/2) is displayed in Figure , which shows values of the mass-dependent isotopic fractionation of Kr and Xe (δKr and δXe, respectively). After correction, the new δXe value for sample 3 is −19.0 ± 1.2‰ u–1, a value in complete agreement with those obtained for barite samples 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. A similar correction could be applied to sample 4. However, the absence of a clear mass-dependent fractionation pattern in the Kr isotope spectra (Figure ) would lead to high uncertainties for the corrected δXe value. Altogether, our results point toward a value of −19.1 ± 1.8‰ u–1 for the isotopic fractionation of paleoatmospheric xenon trapped in the ca. 3.48 Ga old barite samples analyzed in this study (Figure ). Thus, our results support previous data obtained by Pujol et al. and confirm that the fractionation of atmospheric xenon was higher at 3.5 Ga ago compared to the 3.3 Ga old atmosphere.

9.

Isotopic fractionation of krypton and xenon measured in the barite samples. Both fractionations are given in permil per atomic mass unit (‰ u–1) relative to the composition of modern atmospheric krypton and xenon. The effect of correction of mass-dependent fractionation is shown for sample 3. Results obtained by Pujol et al. are represented by a gray range. The result obtained by Srinivasan is represented with a gray circle. The isotopic fractionation of Archean atmospheric Xe measured for the 3.3 Ga old atmosphere in Barberton samples is shown for comparison.

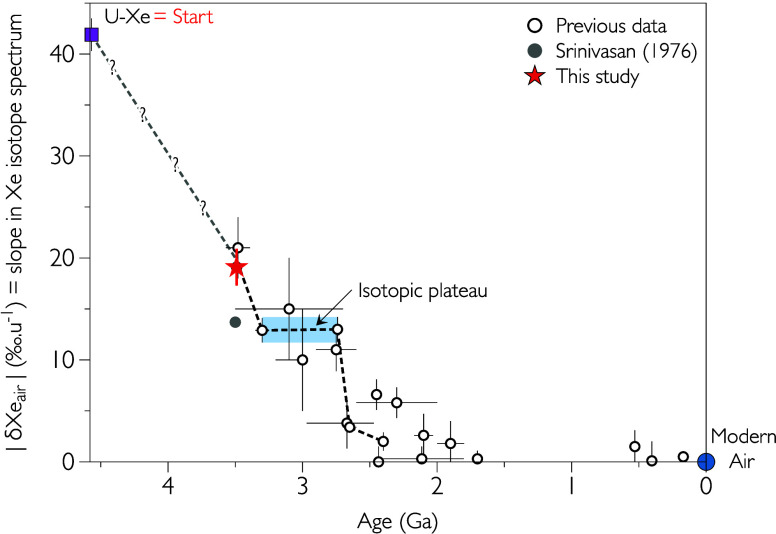

This is consistent with the following scenario (Figure ):

3.5 Ga old atmospheric xenon was fractionated by almost −20‰ u–1, a value about half way between U–Xe, the progenitor of atmospheric xenon , and modern atmospheric xenon (0‰, by definition).

Between 3.5 Ga and 3.3 Ga, the composition of atmospheric xenon evolved from −19.1 ± 1.8 to −10.3 ± 0.5‰ u–1 (see refs , , and ).

The isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon stayed constant between 3.3 and 2.7 Ga. We thus suggest that isotopic plateau lasted about 600 Myr.

After 2.7 Ga, the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon started to evolve again and reached modern-like value at 2.4 Ga, at the time of the GOE.

10.

Updated curve of the evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon. U–Xe corresponds to the progenitor of atmospheric xenon. Empty circles and the gray point obtained by Srinivasan in 1976 represent data from previous studies. − ,− , The new value for the 3.48 Ga old atmosphere is represented by a red star. The isotopic plateau between 3.3 and 2.7 Ga is represented with a blue range encompassing uncertainties of the isotopic fractionation of atmospheric xenon determined previously for these two dates. Errors are at 1σ.

Enrichment in Xe

In the model of joint H+–Xe+ escape, isotopic evolution of atmospheric xenon should be accompanied by a depletion of atmospheric xenon over time (ref see also Introduction). The present study provides a new opportunity to test if the 3.5 Ga old atmosphere was enriched in xenon relative to the modern atmosphere and, furthermore, to compare our results with those obtained by Broadley et al. for quartz from the Barberton Greenstone Belt. Noble gas elemental ratios (relative to 36Ar) measured in this study are distinct from those of noble gases contained in the modern atmosphere (see the Results section and Figure ). While Ne/Ar and Kr/Ar ratios are relatively close to those of noble gases dissolved in water (either seawater or bittern brine), Xe/Ar ratios are generally higher (Figure ). Using the same three-element plot as the one used in a previous study, it becomes clear that noble gases released from the fluid inclusions contained in barite samples measured in the present study present an enrichment in Xe relative to Kr (Figure ). 130Xe/84Kr ratios range from 0.015 to 0.037. This range is at least three times larger than for noble gases contained modern air (0.005). It is also larger than for noble gases dissolved in seawater and/or trapped in metamorphic hydrothermal quartz (25 and refs therein). As described above, the fluid trapped in the ca. 3.48 Ga old barites consists in a mixture between a paleoatmospheric and a hydrothermal end-member and contribution from modern air cannot be fully excluded. It is thus challenging to determine accurately what was the true paleoatmospheric Xe/Kr ratio. The fact that most data show Xe/Kr ratios lower than the value determined for Barberton quartz (0.037) by Broadley et al. suggests that the abundance of Xe in the Archean atmosphere could have been previously overestimated. Note however that the Xe/Kr ratio tends to increase when crushing proceeds (Figure ) suggesting that the trapped component in the least accessible fluid inclusion has a high Xe/Kr ratio. Future studies should focus on disentangling the paleoatmospheric and hydrothermal components in ancient samples containing paleoatmospheric signals in order to draw more substantial conclusions on the elemental ratios of the noble gases contained in the Archean atmosphere.

11.

Elemental ratios of Ar and Xe relative to Kr measured in barite samples. All crushing steps are displayed, and the crushing step number appears next to the symbol. Ar/Kr ratios are intermediate between air and mantle values. Xe/Kr ratios are significantly higher than for modern atmospheric noble gases dissolved in seawater or trapped in 1.5 Ga old metamorphic quartz but remain lower than the value defined by ref for the 3.3 Ga old Archean atmosphere. The figure was modified after ref . See refs therein.

Conclusion

A better knowledge of the composition of the atmosphere surrounding Archean Earth is a key to understand our planet’s geological history. In this study we measured noble gases contained in fluid inclusions of ca. 3.48 Ga old barites from the Dresser Formation (North Pole, Australia). The elemental and isotopic compositions of noble gases contained in the fluid inclusions are consistent with a mixture between Archean atmospheric noble gases and crustal noble gases produced inside the Earth’s crust. Results are used to determine that the isotopic composition of 3.5 Ga old Archean atmospheric xenon was fractionated by −19.1 ± 1.8‰ u–1 in favor of light isotopes relative to the composition of modern atmospheric Xe. For some samples, the isotopic composition of paleoatmospheric xenon can be recovered after correcting for mass-dependent fractionation using fractionated Kr isotopic composition. Xenon in the trapped fluid is enriched relative to Kr, confirming that there was more xenon in the Archean atmosphere because escape of xenon was still ongoing. The new curve of the evolution of the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon is compatible with a pause of about 600 Myr long in the evolution. This could be due to a pause of the leakage of xenon from the Earth’s atmosphere if conditions for escape were not met during this time window. Future studies should focus on determining the true abundance of xenon in the Archean atmosphere as well as on finding ∼3.4 Ga old paleoatmospheric signals in order to determine how fast the isotopic composition of atmospheric xenon evolved between 3.5 and 3.3 Ga ago.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Guillaume Avice acknowledges Prof. Bernard Marty for his pioneering work on paleoatmospheres and his continuous support throughout the years. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Program (Grant Agreement 101041122 to Guillaume Avice). Helge Mißbach-Karmrodt and Joachim Reitner received funding from the German Research Foundation [DFG Priority Programme (SPP) 1833 “Building a Habitable Earth”: DU 1450/3-1, DU 1450/3-2, TH 713/13-2, and RE 665/42-2]. The authors thank J. Blum for his editorial handling of the manuscript as well as three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. The authors dare to think that Reika Yokochi, with her strong background in crustal noble gas geochemistry and her experience on the topic of noble gases in the ancient Earth, would have been interested in these results showing the entrapment of very ancient paleoatmospheric signals in Archean barites.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.4c00356.

Experimental results listed in a table containing noble gas abundances expressed in cm3 STP g–1 and isotopic ratios (XLSX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Published as part of ACS Earth and Space Chemistry special issue “Reika Yokochi Memorial”.

References

- Catling D. C., Zahnle K. J.. The Archean Atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(9):eaax1420. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G., Ono S., Beukes N. J., Wang D. T., Xie S., Summons R. E.. Rapid Oxygenation of Earth’s Atmosphere 2.33 Billion Years Ago. Science Advances. 2016;2(5):e1600134. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcott L. J., Mills B. J. W., Poulton S. W.. Stepwise Earth Oxygenation Is an Inherent Property of Global Biogeochemical Cycling. Science. 2019;366(6471):1333–1337. doi: 10.1126/science.aax6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi J., Seales J., Dasgupta R.. Great Oxidation and Lomagundi Events Linked by Deep Cycling and Enhanced Degassing of Carbon. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K., Frost D. J., McCammon C. A., Rubie D. C., Boffa Ballaran T.. Deep Magma Ocean Formation Set the Oxidation State of Earth’s Mantle. Science. 2019;365(6456):903–906. doi: 10.1126/science.aax8376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kump L. R., Kasting J. F., Barley M. E.. Rise of Atmospheric Oxygen and the “Upside-down” Archean Mantle. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2001;2(1):2025. doi: 10.1029/2000GC000114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard F., Bouhifd M. A., Füri E., Malavergne V., Marrocchi Y., Noack L., Ortenzi G., Roskosz M., Vulpius S.. The Diverse Planetary Ingassing/Outgassing Paths Produced over Billions of Years of Magmatic Activity. Space Sci. Rev. 2021;217(1):22. doi: 10.1007/s11214-021-00802-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catling D. C., Zahnle K. J., McKay C. P.. Biogenic Methane, Hydrogen Escape, and the Irreversible Oxidation of Early Earth. Science. 2001;293(5531):839–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1061976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnle K. J., Catling D. C., Claire M. W.. The Rise of Oxygen and the Hydrogen Hourglass. Chem. Geol. 2013;362:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol M., Marty B., Burgess R.. Chondritic-like Xenon Trapped in Archean Rocks: A Possible Signature of the Ancient Atmosphere. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2011;308(3–4):298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.05.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avice G., Marty B., Burgess R.. The Origin and Degassing History of the Earth’s Atmosphere Revealed by Archean Xenon. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15455. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avice G., Marty B., Burgess R., Hofmann A., Philippot P., Zahnle K., Zakharov D.. Evolution of Atmospheric Xenon and Other Noble Gases Inferred from Archean to Paleoproterozoic Rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2018;232:82–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert D. V., Broadley M. W., Delarue F., Avice G., Robert F., Marty B.. Archean Kerogen as a New Tracer of Atmospheric Evolution: Implications for Dating the Widespread Nature of Early Life. Science Advances. 2018;4(2):eaar2091. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avice G., Marty B.. Perspectives on Atmospheric Evolution from Noble Gas and Nitrogen Isotopes on Earth, Mars & Venus. Space Sci. Rev. 2020;216(3):36. doi: 10.1007/s11214-020-00655-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almayrac M. G., Broadley M. W., Bekaert D. V., Hofmann A., Marty B.. Possible Discontinuous Evolution of Atmospheric Xenon Suggested by Archean Barites. Chem. Geol. 2021;581:120405. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardoin L., Broadley M. W., Almayrac M., Avice G., Byrne D. J., Tarantola A., Lepland A., Saito T., Komiya T., Shibuya T., Marty B.. The End of the Isotopic Evolution of Atmospheric Xenon. Geochem. Persp. Lett. 2022;20:43–47. doi: 10.7185/geochemlet.2207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley M. W., Byrne D. J., Ardoin L., Almayrac M. G., Bekaert D. V., Marty B.. High Precision Noble Gas Measurements of Hydrothermal Quartz Reveal Variable Loss Rate of Xe from the Archean Atmosphere. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2022;588:117577. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnle K. J., Gacesa M., Catling D. C.. Strange Messenger: A New History of Hydrogen on Earth, as Told by Xenon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2019;244:56–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avice G., Kendrick M. A., Richard A., Ferrière L.. Ancient Atmospheric Noble Gases Preserved in Post-Impact Hydrothermal Minerals of the 200 Ma-Old Rochechouart Impact Structure, France. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2023;620:118351. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani F., Avice G., Ferrière L., Alwmark S.. Noble Gases in Shocked Igneous Rocks from the 380 Ma-Old Siljan Impact Structure (Sweden): A Search for Paleo-Atmospheric Signatures. Chem. Geol. 2024;670:122440. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2024.122440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan B.. Barites: Anomalous Xenon from Spallation and Neutron-Induced Reactions. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1976;31(1):129–141. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(76)90104-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol M., Marty B., Burnard P., Philippot P.. Xenon in Archean Barite: Weak Decay of 130Ba, Mass-Dependent Isotopic Fractionation and Implication for Barite Formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2009;73(22):6834–6846. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marty B., Bekaert D. V., Broadley M. W., Jaupart C.. Geochemical Evidence for High Volatile Fluxes from the Mantle at the End of the Archaean. Nature. 2019;575(7783):485–488. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1745-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin R. O.. On the Origin and Early Evolution of Terrestrial Planet Atmospheres and Meteoritic Volatiles. Icarus. 1991;92(1):2–79. doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(91)90036-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, M. A. ; Burnard, P. . Noble Gases and Halogens in Fluid Inclusions: A Journey Through the Earth’s Crust. In The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers; Burnard, P. , Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp 319–369, 10.1007/978-3-642-28836-4_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mißbach H., Duda J.-P., van den Kerkhof A. M., Lüders V., Pack A., Reitner J., Thiel V.. Ingredients for Microbial Life Preserved in 3.5 Billion-Year-Old Fluid Inclusions. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1101. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann L., Reinhardt M., Duda J.-P., Mißbach-Karmrodt H., Drake H., Schönig J., Holburg J., Andreas L. B., Reitner J., Whitehouse M. J., Thiel V.. Carbonaceous Matter in ∼ 3.5 Ga Black Bedded Barite from the Dresser Formation (Pilbara Craton, Western Australia)Insights into Organic Cycling on the Juvenile Earth. Precambrian Research. 2024;403:107321. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2024.107321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Djokic T., Van Kranendonk M. J., Campbell K. A., Havig J. R., Walter M. R., Guido D. M.. A Reconstructed Subaerial Hot Spring Field in the ∼ 3.5 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, North Pole Dome, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Astrobiology. 2021;21(1):1–38. doi: 10.1089/ast.2019.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. C., White N. C., McPhie J., Bull S. W., Line M. A., Skrzeczynski R., Mernagh T. P., Tosdal R. M.. Early Archean Hot Springs above Epithermal Veins, North Pole, Western Australia: New Insights from Fluid Inclusion Microanalysis. Economic Geology. 2009;104(6):793–814. doi: 10.2113/gsecongeo.104.6.793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman W., De Bruijne K. H., Valkering M. E.. Growth Fault Control of Early Archaean Cherts, Barite Mounds and Chert-Barite Veins, North Pole Dome, Eastern Pilbara, Western Australia. Precambrian Research. 1998;88(1–4):25–52. doi: 10.1016/S0301-9268(97)00062-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranendonk M. J.. Volcanic Degassing, Hydrothermal Circulation and the Flourishing of Early Life on Earth: A Review of the Evidence from c. 3490–3240 Ma Rocks of the Pilbara Supergroup, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Earth Science Reviews. 2006;74(3–4):197–240. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranendonk M. J., Pirajno F.. Geochemistry of Metabasalts and Hydrothermal Alteration Zones Associated with 3.45 Ga Chert and Barite Deposits: Implications for the Geological Setting of the Warrawoona Group, Pilbara Craton, Australia. GEEA. 2004;4(3):253–278. doi: 10.1144/1467-7873/04-205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duda J.-P., Thiel V., Bauersachs T., Mißbach H., Reinhardt M., Schäfer N., Van Kranendonk M. J., Reitner J.. Ideas and Perspectives: Hydrothermally Driven Redistribution and Sequestration of Early Archaean BiomassThe “Hydrothermal Pump Hypothesis. Biogeosciences. 2018;15(5):1535–1548. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-1535-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranendonk M., Philippot P., Lepot K., Bodorkos S., Pirajno F.. Geological Setting of Earth’s Oldest Fossils in the ca. 3.5Ga Dresser Formation, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Precambrian Research. 2008;167(1–2):93–124. doi: 10.1016/j.precamres.2008.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranendonk, M. J. ; Smithies, R. H. ; Hickman, A. H. ; Champion, D. C. . Paleoarchean Development of a Continental Nucleus: The East Pilbara Terrane of the Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. In Developments in Precambrian Geology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007; Vol. 15, Chapter 4.1, pp 307–337, 10.1016/S0166-2635(07)15041-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert D. V., Avice G., Marty B., Henderson B., Gudipati M. S.. Stepwise Heating of Lunar Anorthosites 60025, 60215, 65315 Possibly Reveals an Indigenous Noble Gas Component on the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2017;218:114–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2017.08.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Györe D., Sumino H., Yang I., Palcsu L., László E., Bishop M. C., Mukhopadhyay S., Stuart F. M.. Inter-Laboratory Re-Determination of the Atmospheric 22Ne/20Ne. Chem. Geol. 2024;645:121900. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meshik A., Hohenberg C., Pravdivtseva O., Burnett D.. Heavy Noble Gases in Solar Wind Delivered by Genesis Mission. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014;127(C):326–347. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeesch P.. IsoplotR: A Free and Open Toolbox for Geochronology. Geoscience Frontiers. 2018;9(5):1479–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2018.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy B. M., Hiyagon H., Reynolds J. H.. Crustal Neon: A Striking Uniformity. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1990;98(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(90)90030-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann-Pipke J., Sherwood Lollar B., Niedermann S., Stroncik N. A., Naumann R., van Heerden E., Onstott T. C.. Neon Identifies Two Billion Year Old Fluid Component in Kaapvaal Craton. Chem. Geol. 2011;283:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland G., Lollar B. S., Li L., Lacrampe-Couloume G., Slater G. F., Ballentine C. J.. Deep Fracture Fluids Isolated in the Crust since the Precambrian Era. Nature. 2013;497(7449):357–360. doi: 10.1038/nature12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill G. W.. Variations in the Isotopic Abundances of Neon and Argon Extracted from Radioactive Minerals. Phys. Rev. 1954;96(3):679–683. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.96.679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsevich I., Honda M.. Production of Nucleogenic Neon in the Earth from Natural Radioactive Decay. Journal of Geophysical Research. 1997;102(B5):10291–10298. doi: 10.1029/97JB00395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leya I., Wieler R.. Nucleogenic Production of Ne Isotopes in Earth’s Crust and Upper Mantle Induced by Alpha Particles from the Decay of U and Th. Journal of Geophysical Research. 1999;104(B7):15439–15450. doi: 10.1029/1999JB900134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballentine C. J., Marty B., Sherwood Lollar B., Cassidy M.. Neon Isotopes Constrain Convection and Volatile Origin in the Earth’s Mantle. Nature. 2005;433(7021):33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature03182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. J., Avice G., Parai R.. Noble Gas Insights into Early Impact Delivery and Volcanic Outgassing to Earth’s Atmosphere: A Limited Role for the Continental Crust. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2023;609:118083. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marty B., Altwegg K., Balsiger H., Bar-Nun A., Bekaert D. V., Berthelier J. J., Bieler A., Briois C., Calmonte U., Combi M., De Keyser J., Fiethe B., Fuselier S. A., Gasc S., Gombosi T. I., Hansen K. C., Hässig M., Jackel A., Kopp E., Korth A., Le Roy L., Mall U., Mousis O., Owen T., Reme H., Rubin M., Semon T., Tzou C. Y., Waite J. H., Wurz P.. Xenon Isotopes in 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko Show That Comets Contributed to Earth’s Atmosphere. Science. 2017;356(6342):1069–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira M., Kunz J., Allègre C.. Rare Gas Systematics in Popping Rock: Isotopic and Elemental Compositions in the Upper Mantle. Science. 1998;279(5354):1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozima, M. ; Podosek, F. A. . Noble Gas Geochemistry, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2001; 10.1017/CBO9780511545986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parai R., Mukhopadhyay S., Standish J. J.. Heterogeneous Upper Mantle Ne, Ar and Xe Isotopic Compositions and a Possible Dupal Noble Gas Signature Recorded in Basalts from the Southwest Indian Ridge. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2012;359–360(C):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2012.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli D., Ballentine C. J., Wieler R.. An Overview of Noble Gas Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 2002;47(1):1–19. doi: 10.2138/rmg.2002.47.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.