Significance

The FeMo cofactor (FeMoco) is the active center of N2-to-NH3 conversion in the Mo-based nitrogenase, but a mimic that replicates its trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] core with an interstitial µ6-bridging carbide is yet to be synthesized. Herein we report the synthesis of a FeMoco mimic containing a trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety with a µ6-carbide. An analogous mimic with the [Fe6N] unit has also been synthesized. By employing a retrosynthetic analysis, a strategy for the prospective synthesis of model clusters of FeMoco with varied metal composition and interstitial atom has been established, offering a potential platform for the comparative studies of the physical/chemical properties of close structural mimics of the FeMoco.

Keywords: FeMo cofactor, synthetic model, synthetic strategy, carbide, electronic structure

Abstract

The FeMo cofactor (FeMoco), the key active site in the Mo-based nitrogenase, is one of the most complicated metalloenzyme molecules. Synthesis of the FeMoco model cluster ([MoFe7S9C]) is essential to understanding its function in dinitrogen binding, activation, and conversion. However, the complex framework of the FeMoco cluster, which features a unique trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety comprising a µ6-bridging carbide, has made the synthesis of the cluster a persistent challenge. In this work, two analogous mimics of FeMoco have been synthesized, using a cluster-coupling synthetic strategy facilitated by the fabrication of unsaturated ligand/metal coordination. The incorporation of a µ6-X (X = C4− or N3−) to construct the characteristic triangular prismatic [Fe6(µ6-X)] moiety, replicating that in FeMoco, has been achieved synthetically. The two mimics have similar key structural parameters to FeMoco in natural nitrogenase, but differ from the FeMoco structure in two major aspects: the µ2-bridging ligands and the metal atoms capping the [Fe6S9C] cores (Mo/Fe in FeMoco vs. Mo/Mo or W/W in the synthetic models). Quantum chemical studies indicate that the electronic ground states of these clusters resemble those observed for FeMoco, with maximized antiferromagnetic coupling among the iron centers. A future systematic study on the physical and chemical properties of a family of mimics with programmed variations of key structural elements can provide a valuable comparison and facilitate a better understanding of the structure and function of FeMoco.

The conversion of inert atmosphere dinitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3) is of critical importance to both living systems and modern industry (1). In nature, the nitrogenase in certain microorganisms catalyzes the N2-to-NH3 conversion under ambient conditions (<40 °C and 1 atm) (2), whereas the industrial Haber–Bosch process for ammonia production requires high temperatures and pressure (typically 300~500 °C and 150~200 atm), which leads to substantial energy consumption and CO2 emissions (3). Biomimetic nitrogen fixation is potentially an alternate way of artificial ammonia synthesis. This endeavor relies on an in-depth understanding of the mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase, which remains elusive to date (4). One of the major obstacles within this realm is the synthetic challenges associated with the structural complexity of the nitrogenase FeMo cofactor (FeMoco, [MoFe7S9C]), which features an apex-fusing double-cubane ([MoS3Fe3C] and [CFe3S3Fe]) structure with a triple-µ2-S bridged trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety comprising a central μ6-carbide ligand (5–7). Great efforts have been dedicated to understanding nitrogenase, and significant progress has been made so far in elucidating the role of FeMoco, from the structural (8–15), synthetic (5–7, 16–26), spectroscopic (10, 11, 27–29), mechanistic (4, 28, 30–35), or theoretical (28, 36, 37) aspects. However, the chemical synthesis of an analogous cluster of the complete FeMoco structure, particularly that possessing a trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety, has not yet been accomplished.

It has been demonstrated that FeMoco is the key site where N2 is bound, activated, and reduced in the Mo-based nitrogenase (28), with electrons transferred by the [Fe4S4] cluster in Fe–protein and the P-cluster ([Fe8S7]) in MoFe–protein. Historically, following the determination of its core structure [MoFe7S9] in 1992, an interstitial 2p-atom was discovered in 2002 to reside in the center of FeMoco, which was eventually assigned as a carbide in 2011 to constitute a [MoFe7S9C] cluster (Fig. 1, highlighted by orange) (8–11). The synthesis of a FeMoco analog has attracted considerable attention in the field of synthetic iron–sulfur chemistry related to nitrogenase (5–7). However, the presence of an interstitial carbide in a very complex iron–sulfur cluster framework has posed a grand challenge to the synthesis of an analogous mimic of FeMoco. The synthetic task is extremely complicated, involving the incorporation of a carbide ligand into a Mo–Fe–S cluster, and the concomitant shaping of the cluster into a vertex(carbide)-sharing double-cubane structure comprising the trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] unit bridged by three µ2-S atoms. Even the subtasks within this scenario constitute tough synthetic challenges. First, the generation and incorporation of a carbide ligand into an iron–sulfur cluster is challenging. There are current research works on carbide complexes, such as the carbonyl-ligated iron–carbide clusters and the terminal metal–carbide complexes, with iron–sulfur–carbide clusters providing only partial model of the FeMoco structure (38–50). Second, the existing [Fe6X] (X = C or N) core invariably adopts an octahedral geometry in the cases of iron–carbide clusters, rather than the trigonal prismatic geometry observed in FeMoco (38, 39, 43–50). Third, the targeted formation of the complicated [MoFe7S9C] framework, i.e., the construction of an apex-fused double cubane structure with three µ2-bridging sulfides and the concomitant incorporation of a µ6-carbide into the center of the cluster, is difficult (17, 18).

Fig. 1.

Timeline showing the milestones in revealing the FeMoco structure (highlighted by light-orange, shown by red dots on the timeline), key events in synthetic mimicking of the FeMoco structure (highlighted by light-green, shown by green dots on the timeline), and our synthetic mimics (highlighted by light-blue, shown by blue dots on the timeline).

Despite considerable synthetic efforts toward various iron–sulfur clusters to mimic the FeMoco structure, an analogous mimic that replicates the characteristic trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety remains elusive (Fig. 1, highlighted by green) (17–24). In pursuit of a synthetic scheme toward the FeMoco structure, we were kindled by the total synthesis strategy commonly used in organic chemistry. Through retrosynthetic analysis of the FeMoco structure, a synthetic route was designed and a cluster-coupling strategy for synthesizing the complicated FeMoco structure was envisaged. The feasibility of the cluster-coupling reactions was eventually demonstrated through the use of synthetically optimized precursors. Consequently, two cluster mimics paralleling the FeMoco structure have been successfully synthesized, which contain the characteristic triangular prismatic [Fe6(μ6-X)] (X = C, N) moieties with interstitial carbide and nitride, respectively (Fig. 1, highlighted by blue). Cluster [(Tp*)2W2S6Fe6(μ6-C)(SPh)3]− (Tp*= tris(3,5-dimethyl-1-pyrazolyl)hydroborate) represents a synthetic mimic of the FeMoco cluster that replicates the trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety with an interstitial µ6-carbide.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis.

Inspired by the idea of retrosynthetic analysis in organic total synthesis, the rational synthetic route for the whole FeMoco framework was conceived, as depicted in Fig. 2A. The key step emerged as the cluster-coupling reaction between a complete cubane-like [MoS3Fe3(μ3-C)] cluster and an incomplete cubane-like [Fe4S3] cluster. The [MS3Fe3(μ3-X)] (I, M = Mo or W; X = C or N) and the [Fe3S3M] (II) clusters were designed as the initial precursors for the cluster-coupling reactions. The introduction of the three µ2-S bridges can be realized by programming the terminal ligands on the iron sites of both precursors. When one of the precursors supplies the µ2-S bridges and the other precursor has labile terminal ligands on the iron atoms, the simultaneous introduction of the µ2-S bridges during cluster-coupling can be achieved. Through a systematic screening involving a series of over a hundred of reactions using precursors with different types of terminal ligands and using different reaction conditions, it is eventually demonstrated that the thiophenolate (PhS−) is the ideal terminal ligand for precursor I, and the triethylphosphine (PEt3) constitutes the optimal labile ligand in precursor II.

Fig. 2.

(A) Retrosynthetic analysis of the FeMoco structure. (B) Synthetic route of cluster [III-a]−. (C) Synthetic route for cluster [III-b]−. Clusters were isolated as Et4N+ or BPh4− salt.

The preliminary phase of the endeavor involved the construction of a nitride-containing cluster mimic, with the objective of ascertaining the viability of the cluster-coupling strategy. The synthesis of starting materials [Et4N]2[1], [Et4N][2], and [Et4N]2[3] was performed utilizing the established methodologies (21, 23, 51). Despite the attempts of various pathways to synthesize the nitride-containing precursor with [MoS3Fe3(μ3-N)] core terminally ligated by the S-donors (precursor I), neither direct terminal ligand substitution nor N-Si bond breaking using fluoride gave satisfactory results. Eventually, the desired precursor [Et4N]5[(Tp*)MoS3Fe3(μ3-N)(SPh)3]2 ([Et4N]5[I-a]2) was achieved through core fragmentation of the edge-bridged double-cubane cluster (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). However, our attempts to synthesize the triethylphosphine-bound precursor II proved unsuccessful, with only the [(Tp*)MoS3Fe3(μ3-Cl)(PEt3)3][BPh4] ([II-a][BPh4]) with the expected void occupied by a chloride being obtained. Consequently, the direct reaction between [Et4N]5[I-a]2 and [II-a][BPh4] was conducted by leveraging the lability of the µ3-Cl (21, 22) to generate II in situ (23, 24), and the cluster-coupling reaction proceeded smoothly as anticipated to form [Et4N][(Tp*)2Mo2S6Fe6(μ6-N)(SPh)3] ([Et4N][III-a]) (Fig. 2B). It is remarkable that cluster [III-a]− exhibits a notable similarity to FeMoco, in that the FeMoco topology with a trigonal prismatic [Fe6N] unit incorporating a μ6-nitride is achieved (Fig. 2B).

Following the verification of the cluster-coupling strategy, efforts were directed toward the synthesis of precursor I with carbide. The cluster [(Tp*)WS3Fe3(μ3-C-SiMe3)(SPh)3]− ([I-b]−) was obtained by means of terminal ligand substitution of cluster [2]− (23) using sodium thiophenolate. Since the prior method for obtaining nitride is not transplantable for generating carbide, a synthetic strategy was devised to produce carbide by using fluoride to break the C-Si bond of the μ3-C-SiMe3 in cluster [I-b]−, taking advantage of the large bond energy difference between the C–Si and F–Si bonds. However, attempts to isolate the targeted [(Tp*)MS3Fe3(μ3-C)(SPh)3]z cluster (z denotes the variable cluster charge) remained unsuccessful. Therefore, a reaction between the in situ generated type I and type II precursors was envisaged, which included the treatment of [Et4N][I-b] with fluoride anion to trigger the in situ generation of [(Tp*)MS3Fe3(μ3-C)(SPh)3]z followed by the addition of [(Tp*)WS3Fe3(μ3-Cl)(PEt3)3][BPh4] ([II-b][BPh4]) and reductant. Consequently, the C–Si bond cleavage was realized and the cluster-coupling reaction resulted in the formation of the cluster [Et4N][(Tp*)2W2S6Fe6(μ6-C)(SPh)3] ([Et4N][III-b]) as the product (Fig. 2C). The synthesis of this cluster [III-b]− is of particular significance, not only because the cluster closely resembles FeMoco with a trigonal prismatic [Fe6C] moiety (Fig. 2C) but also because it demonstrates the feasibility of the carefully designed strategy in inorganic synthesis for generating and stabilizing a carbide inside iron–sulfur clusters.

Characterizations.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of the clusters [Et4N][III-a] and [Et4N][III-b] indicates that both of these clusters exhibit a FeMoco-type scaffold, each comprising a trigonal prismatic [Fe6(μ6-X)] (X = N for [III-a]− and C for [III-b]−) moiety in the center. The superposition of the core structures indicates that clusters [III-a]− and [III-b]− match very well with the FeMoco topology, as shown in Fig. 3 and S18A. The two [Fe3] faces of the trigonal prismatic [Fe6X] unit are capped by two [(Tp*)MoS3] species in [III-a]− and by a couple of [(Tp*)WS3] species in [III-b]− (Fig. 3 B and C). In both mimics, each pair of irons on the edges of the triangular prism [Fe6X] unit is bridged by a µ2-PhS− ligand (Fig. 3 B and C). In the FeMoco structure, however, the corresponding iron pairs are bridged by µ2-sulfide ligands (SI Appendix, Fig. S18A). This is one of the major differences between these model clusters and the FeMoco. Further comparison of the bond lengths between FeMoco (resting state) and our synthetic mimics reveals only slight differences. The mean Mo···Fe and Fe-(µ2-S) distances outside the trigonal prismatic [Fe6X] moiety are slightly shorter in FeMoco than in our synthetic mimics (SI Appendix, Fig. S18B), while the average distances of Fe···Fe and Fe–X within the [Fe6X] moiety are slightly longer in FeMoco than in our synthetic mimics. The slightly larger geometry of the [Fe6X] moiety in FeMoco as compared with our synthetic mimics is presumably correlated with distinct metal oxidation states within the [Fe6X] moiety (vide infra).

Fig. 3.

(A) Structural model of FeMoco in protein crystal (11). (B) The crystal structure of [III-a]− (Top: the anionic cluster; Bottom: the core structure). (C) The crystal structure of [III-b]− (Top: the anionic cluster; Bottom: the core structure). (D) ESI-HRMS of [Et4N][III-a] and [Et4N][III-b]. All atoms in structure diagrams of [III-a]− and [III-b]− are shown at 50% thermal ellipsoids probability. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. ESI-HRMS were recorded on a Thermo Q Exactive Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer.

The identities of the central atoms are substantiated by single-crystal X-ray analysis, electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry (ESI-HRMS) and elemental analysis. ESI-HRMS of the two mimics indicates well-fitted experimental and theoretical patterns for both of them (Fig. 3D). Elemental analysis of each mimic also reveals good agreement between the experimental and calculated elemental compositions. The rational synthetic routes and the single-crystal structure analysis indicate the total metal oxidation state of [Mo2Fe6]19+ in [III-a]− and [W2Fe6]20+ in [III-b]−, which are more reduced as compared to [MoFe7]21+ in FeMoco at the resting state (52, 53). To gain further insight into the metal oxidation states, the two model clusters were subjected to the Mössbauer study (Fig. 4). Both of the Mössbauer spectra of the two model clusters have been analyzed to feature a two-component fit, with the isomer shift and the quadrupole splitting indicating two types of iron. Based on the single-crystal structure analysis, Mössbauer study, and quantum-theoretical calculations, the iron oxidation states in the two model clusters can be tentatively assigned as [(Mo3+)2(Fe2.5+)2(Fe2+)4(N3−)]16+ for [III-a]− and [(W3+)2(Fe2.5+)4(Fe2+)2(C4−)]16+ for [III-b]− (see details in the Quantum Chemical Calculations section). While there is an empirical linear relationship between isomer shift and iron oxidation state for tetrahedral FeS4 sites with “covalent ligands” or for FeS3L sites with “ionic ligands” in weak-field Fe–S/Mo–Fe–S clusters (6, 22, 54), this relationship does not fit well in our cases, which can be attributed to the complex structure of the two mimics with a [Fe6X] moiety that may result in unusual electron distributions. The two mimics exhibit distinct 1H NMR spectra, which can be attributed to the differences in peripheral caping metal atoms, central 2p atoms, μ2-bridging ligands, and metal oxidation states (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S6).

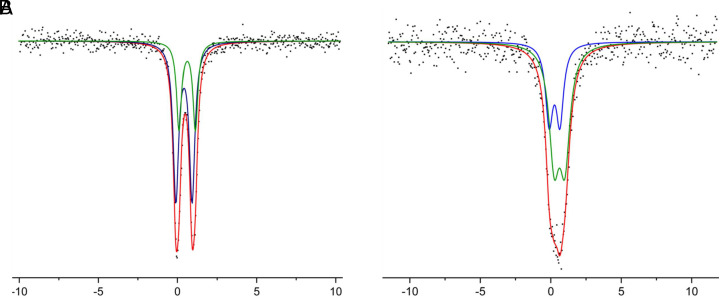

Fig. 4.

Zero field 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of [Et4N][III-a] (A) and [Et4N][III-b] (B) obtained at 77 K. Simulation parameters: A: δ/|ΔEq| (mm s−1): blue fit (67%): 0.41/1.01; green fit (33%): 0.61/1.02. B: δ/|ΔEq| (mm s−1): blue fit (33%): 0.26/0.75; green fit (67%): 0.62/0.76.

A study of the electrochemical properties of the mimics in acetonitrile using cyclic voltammetry (CV) disclosed that each of the clusters [III-a]− and [III-b]− exhibits three quasireversible redox events (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 and S20). The redox potentials of the analogous Mo–Fe–S and W–Fe–S clusters usually differ by about 200 to 500 mV (55). However, the variations at both the heterometal sites and the interstitial atoms make it difficult to determine the dependence of the redox potential on the central atoms. Since the value of the open circuit potential (OCP) measured for [III-b]− is very close to the peak potential at −1.04 V, a further CV study was carried out using N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) as the solvent (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 and S20). The correspondence of the redox pairs with the redox events in the CV curves can thus be achieved by a combined analysis of the OCP values and CV curves of both mimics in acetonitrile and DMF. Consequently, the three quasireversible redox events (in CH3CN) for [III-a]− ([Mo2Fe6]19+) can be proposed to belong to redox events within the series [Mo2Fe6]20+/[Mo2Fe6]19+/[Mo2Fe6]18+/[Mo2Fe6]17+. The three quasireversible redox events for [III-b]− ([W2Fe6]20+) can be proposed to belong to redox events within the series [W2Fe6]21+/[W2Fe6]20+/[W2Fe6]19+/[W2Fe6]18+.

Quantum Chemical Calculations.

We carried out quantum chemical studies based on broken-symmetry density functional theory (BS-DFT) (56) to offer insights into the electronic ground-state structures of the two cluster mimics. The assumptions of Mo(III)/W(III) oxidation states and triangular prismatic core structures [Fe6X] with D3h symmetry are used for the self-consistent field initial guess. A variety of BS states are considered based on the analysis of the possible electron-spin state isomers (57), and both the electronic ground states of [III-a]− and [III-b]− clusters predict the low-spin state, with the spin quantum numbers of S = ½ and 0, respectively (SI Appendix, Tables S2, S6, and S7). The optimized structures with generalized gradient approach functionals of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) level reproduce the crystalline structure well (SI Appendix, Figs. S23 and S32). Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S24 provide the Mulliken spin density population inside the clusters, in which the BS2 solutions are shown to be lowest in energy and maximize the antiferromagnetic (AF) coupling between the iron centers, being consistent with previous findings in FeMoco (36, 37).

Fig. 5.

Theoretical results for the ground state (S = 0, BS2) of [III-b]− cluster at the PBE level. Here, S is the spin quantum number; BS means the broken-symmetry state, where the definition of BS2 state can be found in SI Appendix, Fig. S22. (A) Diagram and values of Mulliken spin density population. Red and blue represent spin-up (α) and spin-down (β) population, respectively. (B) Electronic ground state diagram with spin distribution. The bold dashed lines represent metal–metal bonding between the two atoms. (C) Four seven-center two-electron (7c-2e) AdNDP orbitals and the corresponding orbital compositions for the Fe–C interactions. AdNDP: Adaptive Natural Density Partitioning.

To evaluate the oxidation states for each metal center, a theoretical analysis of Pipek–Mezey localized molecular orbitals (PM-LMOs) (58) is carried out. Fig. 5B shows the calculated electronic ground-state structure of [III-b]− cluster, where each iron atom in this iron-sulfur double-cubane appears to possess a high-spin configuration in a tetrahedral ligand field. Inspection of the PM-LMOs in Fe-3d manifold (SI Appendix, Figs. S33–S36) supports the identification of their oxidation states as follows. In [III-b]− cluster, the mixed-valence Fe(+2.5)−Fe(+2.5) pair can be found in Fe1−Fe2 and Fe4−Fe5 atoms, with a delocalized electron shared by the adjacent iron ions (SI Appendix, Figs. S33 and S34), which is reminiscent of the scenario of Fe–Fe interaction with low oxidation state iron atoms (59). Moreover, the oxidation states of two AF-coupled Fe3 and Fe6 atoms are established as divalent Fe(II) derived from the electron counting of their PM-LMOs (SI Appendix, Fig. S35). The spin-coupled W atoms have low-spin configurations with W(III) oxidation states (SI Appendix, Fig. S36), accompanied by the fact that W-5d electrons are significantly delocalized toward Fe atoms. Accordingly, the Mayer bond orders (BOs) in SI Appendix, Table S10 suggest that the Fe−W BOs are about 0.50, indicating the strength of Fe−W covalent interactions. The BOs values for Fe−Fe pairs lie within 0.34 to 0.45, which are consistent with the local orbital contours and suggest the presence of non-negligible, albeit weak, Fe−Fe interaction. As a consequence, based on the synthetic stoichiometry and single-crystal structure analysis, in combination with Mössbauer spectrum (Fig. 4), the metal oxidation states are assigned as [(W3+)2(Fe2.5+)4(Fe2+)2(C4−)]16+ for the mimic [III-b]− (Fig. 5B). With analogous orbital localization interpretation of [III-b]−, the electronic ground state of [III-a]− cluster can be described as [(Mo3+)2(Fe2.5+)2(Fe2+)4(N3−)]16+ (SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S25–S29). Following the identification of oxidation state on each metal center in these two mimics, it becomes clear that these structural mimics are more reduced than the resting state of FeMoco with [(Mo3+)(Fe2+)3(Fe3+)4] (37). Notably, by comparing the calculated atomic charges in the two core structures with FeMoco (SI Appendix, Table S11), the individual characteristic of the Mo or W heterometals can affect the charge distribution of the iron cluster core centers. The charge distribution in [III-a]− with 4d heterometals is more similar to FeMoco. As the heterometals change to heavier 5d atoms, they become more positively charged and the average charge on Fe decreases by 0.13|e|, which is consistent with the compositions of the heterometal–iron bonding in the PM-LMOs analysis.

The calculated density-of-states curves elaborate the chemical bonding in these two synthesized mimics. As depicted in SI Appendix, Figs. S30 and S37, the α and β spin-states are almost symmetrically distributed due to the AF coupling of iron centers in the low-spin BS2 state. The Fe-3d bands are broadened by virtue of the orbital interaction with the μ2-S, μ3-S bridges and the core-forming C/W atoms in [III-b]− cluster (N/Mo atoms in [III-a]−). The increasing distributions of Fe-3d states below the Fermi level as well as the evenly distributed W-5d states (Mo-4d states in [III-a]−) reflect the expected formal oxidation states of trivalent W(III) (or Mo(III) in [III-a]−), divalent Fe(II) and mixed-valent Fe(+2.5). To explore the interaction between the central carbide (nitride in [III-a]−) and iron ions, Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S31 show the delocalized Kohn–Sham MOs and Adaptive Natural Density Partitioning (AdNDP) (60) results. In the trigonal prismatic cluster core of [Fe6X], four 7c-2e bonds are found with the compositions of occupied X-2s/2p orbitals and empty Fe-3d/4s orbitals. The chemical bonding analyses reveal significant electrostatic interaction between the cationic [(Tp*)2W2S6Fe6(SPh)3]z moiety and μ6-X (X = N3− in [III-a]− and C4− in [III-b]−) as well as the multicentered covalent orbital interaction, through which the core structure of the [Fe6X] trigonal prismatic cluster is stabilized.

Conclusions

Two mimics replicating the triangular prismatic [Fe6(µ6-X)] unit of the FeMoco structure have been synthesized using a cluster-coupling strategy derived from retrosynthetic analysis of the FeMoco framework. The directed incorporation of preexisting nitride or in-situ generated carbide into a structurally complex apex-fused double-cubane M–Fe–S cluster yielded the mimics containing the trigonal prismatic [Fe6(μ6-N)] and [Fe6(μ6-C)] moieties bearing central nitride and carbide, respectively. The two mimics have similar key structural parameters to FeMoco in natural nitrogenase, but differ from the FeMoco structure in two major aspects: i) the µ2-bridging ligands is S2− in FeMoco vs. PhS− in the two mimics; ii) the peripheral caping metal is Mo/Fe in FeMoco vs. Mo/Mo or W/W in the two mimics. Theoretical calculations reveal formally [(W3+)2(Fe2.5+)4(Fe2+)2(C4−)]16+ and [(Mo3+)2(Fe2.5+)2(Fe2+)4(N3−)]16+ total oxidation states of the electronic ground states of these two mimics. The cluster-coupling strategy developed in this work has the potential to serve as a synthetic methodology for constructing FeMoco-type clusters, which can be achieved by varying the M and X atoms and R groups in the precursors for the cluster-coupling reactions. Subsequent systematic studies of the physical and chemical properties using spectroscopic, experimental, and computational methods can provide a valuable comparison and facilitate a better understanding of the structure and function of FeMoco.

Materials and Methods

All reactions and manipulations were performed on standard Schlenk lines or in a glovebox under a dry N2 atmosphere. Details of the materials and methods, experimental procedures and data, and theoretical studies, including compound syntheses and characterizations, electrochemical studies, X-ray crystallography, and theoretical and computational details and results are described in the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92361303; 92261107, 22071110, and 21671104 to X.-D.C.; 22388102, 22033005 and 22250710677 to J.L.), NSFC Center for Single-Atom Catalysis, the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1503900), Start-up fund of Ganjiang Innovative Academy, and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (No. 2020B121201002). X.-D.C. also acknowledges the financial support from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Educational Institutions, the Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Biomedical Functional Materials, and the State Key Laboratory of Coordination Chemistry in Nanjing University. We acknowledge the Center for Advanced Mössbauer Spectroscopy, Mössbauer Effect Data Center, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing the Mössbauer measurement and analysis. We thank the staff from the BL17B1 beamline of the National Facility for Protein Science in Shanghai at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, for assistance during data collection. The computational resource is supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at SUSTech and the CHEM high-performance supercomputer cluster located at the Department of Chemistry, SUSTech.

Author contributions

X.-D.C. designed research; J.L. directed the theoretical study; Y.-Y.X., X.-L.J., J.-L.C., S.-J.Q., J.H., G.X., J.W., Q.-X.Y., H.-Y.Z., Yue Li, X.-W.Z., G.-L.C., Yong Li, Y.-S.C., and C.-Q.X. performed research; Y.-Y.X., X.-L.J., J.-L.C., S.-J.Q., J.L., and X.-D.C. analyzed data; and Y.-Y.X., X.-L.J., J.-L.C., S.-J.Q., J.L., and X.-D.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

A Chinese patent is pending.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Jun Li, Email: junli@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Xu-Dong Chen, Email: xdchen@njnu.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The crystallographic data reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) with deposition numbers CCDC 2355656, 2355658-2355660, and 2419422. These data are freely available at the CCDC via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Chen J. G., et al. , Beyond fossil fuel–driven nitrogen transformations. Science 360, eaar6611 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil B. S., et al. , “Nitrogen fixation” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (Wiley-VCH, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X., Ward B. B., Sigman D. M., Global nitrogen cycle: Critical enzymes, organisms, and processes for nitrogen budgets and dynamics. Chem. Rev. 120, 5308–5351 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seefeldt L. C., et al. , Reduction of substrates by nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 120, 5082–5106 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Čorić I., Holland P. L., Insight into the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase from synthetic iron complexes with sulfur, carbon, and hydride ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7200–7211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S. C., Lo W., Holm R. H., Developments in the biomimetic chemistry of cubane-type and higher nuclearity iron-sulfur clusters. Chem. Rev. 114, 3579–3600 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanifuji K., Ohki Y., Metal-sulfur compounds in N2 reduction and nitrogenase-related chemistry. Chem. Rev. 120, 5194–5251 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J., Rees D. C., Structural models for the metal centers in the nitrogenase molybdenum-iron protein. Science 257, 1677–1682 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einsle O., et al. , Nitrogenase MoFe-protein at 1.16 Å resolution: A central ligand in the FeMo-cofactor. Science 297, 1696–1700 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lancaster K. M., et al. , X-ray emission spectroscopy evidences a central carbon in the nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor. Science 334, 974–977 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spatzal T., et al. , Evidence for interstitial carbon in nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. Science 334, 940–940 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang W., Lee C. C., Jasniewski A. J., Ribbe M. W., Hu Y., Structural evidence for a dynamic metallocofactor during N2 reduction by Mo-nitrogenase. Science 368, 1381–1385 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters J. W., et al. , Comment on “Structural evidence for a dynamic metallocofactor during N2 reduction by Mo-nitrogenase”. Science 371, eabe5481 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang W., Lee C. C., Jasniewski A. J., Ribbe M. W., Hu Y., Response to comment on “Structural evidence for a dynamic metallocofactor during N2 reduction by Mo-nitrogenase”. Science 371, eabe5856 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badding E. D., Srisantitham S., Lukoyanov D. A., Hoffman B. M., Suess D. L. M., Connecting the geometric and electronic structures of the nitrogenase iron–molybdenum cofactor through site-selective 57Fe labelling. Nat. Chem. 15, 658–665 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson D. W. N., Holland P. L., “15.03–Nitrogenases and model complexes in bioorganometallic chemistry” in Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry IV, Parkin G., Meyer K., O’Hare D., Eds. (Elsevier, Oxford, 2022), pp. 41–72, 10.1016/B978-0-12-820206-7.00035-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohki Y., Ikagawa Y., Tatsumi K., Synthesis of new [8Fe-7S] clusters: A topological link between the core structures of P-cluster, FeMo-co, and FeFe-co of nitrogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10457–10465 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta S., Ohki Y., Hashimoto T., Cramer R. E., Tatsumi K., A nitrogenase cluster model [Fe8S6O] with an oxygen unsymmetrically bridging two proto-Fe4S3 cubes: Relevancy to the substrate binding mode of the FeMo cofactor. Inorg. Chem. 51, 11217–11219 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Zuo J.-L., Zhou H.-C., Holm R. H., Rearrangement of symmetrical dicubane clusters into topological analogues of the P cluster of nitrogenase: Nature’s choice? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 14292–14293 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X.-D., Duncan J. S., Verma A. K., Lee S. C., Selective syntheses of iron−imide−sulfide cubanes, including a partial representation of the Fe−S−X environment in the FeMo cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15884–15886 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu G., et al. , Ligand metathesis as rational strategy for the synthesis of cubane-type heteroleptic iron–sulfur clusters relevant to the FeMo cofactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5089–5092 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu G., Zhou J., Wang Z., Holm R. H., Chen X.-D., Controlled incorporation of nitrides into W-Fe-S clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58, 16469–16473 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le L. N. V., Bailey G. A., Scott A. G., Agapie T., Partial synthetic models of FeMoco with sulfide and carbyne ligands: Effect of interstitial atom in nitrogenase active site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2109241118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott A. G., Agapie T., Synthesis of a Fe3–carbyne motif by oxidation of an alkyl ligated iron-sulfur (WFe3S3) cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2–6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeRosha D. E., et al. , Planar three-coordinate iron sulfide in a synthetic [4Fe-3S] cluster with biomimetic reactivity. Nat. Chem. 11, 1019–1025 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiig J. A., Hu Y., Lee C. C., Ribbe M. W., Radical SAM-Dependent carbon insertion into the nitrogenase M-cluster. Science 337, 1672–1675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Stappen C., et al. , The spectroscopy of nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 120, 5005–5081 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman B. M., Lukoyanov D., Yang Z.-Y., Dean D. R., Seefeldt L. C., Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: The next stage. Chem. Rev. 114, 4041–4062 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C.-H., DeBeer S., Structure, reactivity, and spectroscopy of nitrogenase-related synthetic and biological clusters. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 8743–8761 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., et al. , Ammonia formation by a thiolate-bridged diiron amide complex as a nitrogenase mimic. Nat. Chem. 5, 320–326 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y., et al. , A thiolate-bridged FeIVFeIV μ-nitrido complex and its hydrogenation reactivity toward ammonia formation. Nat. Chem. 14, 46–52 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohki Y., et al. , Nitrogen reduction by the Fe sites of synthetic [Mo3S4Fe] cubes. Nature 607, 86–90 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McSkimming A., Suess D. L. M., Dinitrogen binding and activation at a molybdenum–iron–sulfur cluster. Nat. Chem. 13, 666–670 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sippel D., et al. , A bound reaction intermediate sheds light on the mechanism of nitrogenase. Science 359, 1484–1489 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spatzal T., Perez K. A., Einsle O., Howard J. B., Rees D. C., Ligand binding to the FeMo-cofactor: Structures of CO-bound and reactivated nitrogenase. Science 345, 1620–1623 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li W.-L., Li Y., Li J., Head-Gordon T., How thermal fluctuations influence the function of the FeMo cofactor in nitrogenase enzymes. Chem Catal. 3, 100662 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raugei S., Seefeldt L. C., Hoffman B. M., Critical computational analysis illuminates the reductive-elimination mechanism that activates nitrogenase for N2 reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10521–E10530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Churchill M. R., Wormald J., Knight J., Mays M. J., Synthesis and crystallographic characterization of bis(tetramethylammonium) carbidohexadecacarbonylhexaferrate, a hexanuclear carbidocarbonyl derivative of iron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 3073–3074 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tachikawa M., Muetterties E. L., Metal clusters. 25. A uniquely bonded C-H group and reactivity of a low-coordinate carbidic carbon atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 4541–4542 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolis J. W., Basolo F., Shriver D. F., Reactivity of metal carbide clusters: Alkylation and protonation of [Fe5(CO)14C]2−. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 5626–5630 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tachikawa M., Geerts R. L., Muetterties E. L., Metal carbide clusters synthesis systematics for heteronuclear species. J. Organomet. Chem. 213, 11–24 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le L. N. V., et al. , Molybdenum-iron-sulfur cluster with a bridging carbide ligand as a partial FeMoco model: CO activation, EPR studies, and bonding insight. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 11216–11226 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L., Rauchfuss T. B., Woods T. J., Iron carbide-sulfide carbonyl clusters. Inorg. Chem. 58, 8271–8274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tachikawa M., et al. , Metal clusters. 24. Synthesis and structure of heteronuclear metal carbide clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 1725–1727 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu L., Woods T. J., Rauchfuss T. B., Reactions of [Fe6C(CO)14(S)]2–: Cluster growth, redox, sulfiding. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 3460–3465 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joseph C., Kuppuswamy S., Lynch V. M., Rose M. J., Fe5Mo cluster with iron-carbide and molybdenum-carbide bonding motifs: Structure and selective alkyne reductions. Inorg. Chem. 57, 20–23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuppuswamy S., et al. , Structures, interconversions, and spectroscopy of iron carbonyl clusters with an interstitial carbide: Localized metal center reduction by overall cluster oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 56, 5998–6012 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reina R., et al. , Electrophilic additions of metal fragments containing 11- and 12-group elements to the anion carbide cluster [Fe5MoC(CO)17]2-. X-ray crystal structures of (NEt4)[Fe5MoAuC(CO)17(PMe3)] and [Fe5MoAu2C(CO)17(dppm)]. Organometallics 20, 1575–1579 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joseph C., Cobb C. R., Rose M. J., Single-step sulfur insertions into iron carbide carbonyl clusters: Unlocking the synthetic door to FeMoco analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 3433–3437 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pergola R. D., et al. , Characterization, redox properties and structures of the iron nitridocarbonyl clusters [Fe4N(CO)11{PPh(C5H4FeC5H5)2}]–, [Fe6N(CO)15]3– and [Fe6H(N)(CO)15]2–. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 747–754 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 51.He J., Wei J., Xu G., Chen X.-D., Stepwise construction of Mo–Fe–S clusters using a LEGO strategy. Inorg. Chem. 61, 4150–4158 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bjornsson R., et al. , Identification of a spin-coupled Mo(iii) in the nitrogenase iron–molybdenum cofactor. Chem. Sci. 5, 3096–3103 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spatzal T., et al. , Nitrogenase FeMoco investigated by spatially resolved anomalous dispersion refinement. Nat. Commun. 7, 10902 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei J., He J., Xu G., Chen X.-D., Adaptive Mo-Fe-S clusters: Consistent redox behavior versus reversible structural transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 64, e202504016 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu S.-J., et al. , Nitride-bridged Mo-Fe-S double-cubanes: Syntheses, redox behaviors and comparison with their W analogs. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 27, e202400245 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lovell T., Li J., Liu T., Case D. A., Noodleman L., FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase: A density functional study of states MN, MOX, MR, and MI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 12392–12410 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia Y., et al. , Rh19–: A high-spin super-octahedron cluster. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi0214 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pipek J., Mezey P. G., A fast intrinsic localization procedure applicable for ab initio and semiempirical linear combination of atomic orbital wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 4916–4926 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu G., et al. , Synthesis and characterization of iron clusters with an icosahedral [Fe@Fe12]16+ core. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwad327 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zubarev D. Y., Boldyrev A. I., Developing paradigms of chemical bonding: Adaptive natural density partitioning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 5207–5217 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The crystallographic data reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) with deposition numbers CCDC 2355656, 2355658-2355660, and 2419422. These data are freely available at the CCDC via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.