Abstract

Peritoneal metastases (PM), frequently observed in malignancies such as ovarian, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancers, present a significant therapeutic challenge due to poor prognosis and limited effectiveness to systemic chemotherapy. The peritoneal–plasma barrier reduces effective drug transfer from plasma to the peritoneal cavity, reducing cytotoxic effects on PM. Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy offers a locoregional approach, enabling high local drug concentrations that can enhance therapeutic efficacy while limiting systemic toxicity. The three major methods for IP administration—hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC), and catheter-based IP (CBIP) chemotherapy—each provide unique pharmacokinetic (PK) advantages for PM treatment. This review provides a comprehensive update on the pharmacological rationale of IP chemotherapy, focusing on drug characteristics that support extended IP retention and effective tumor targeting. The effects of administration variables are discussed, highlighting their role in optimizing IP drug exposure. Additionally, recent PK data on commonly used drugs in IP therapy, including platinum-based agents, taxanes, and novel nanoparticle formulations, will be evaluated. While PK rationale supports the administration of IP chemotherapy, further efficacy results from ongoing clinical trials are still awaited. Innovations in nanoparticle-based formulations and controlled-release systems offer substantial potential for improving both drug retention and targeted delivery, enhancing treatment precision and minimizing systemic toxicity. Continued exploration in these areas, along with optimization of IP administration protocols, is vital for advancing patient outcomes, refining therapeutic strategies, and maximizing the benefits of IP chemotherapy in clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40265-025-02195-9.

Key Points

| This review updates the pharmacological rationale of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. |

| Intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves HIPEC, PIPAC, or CBIP and offers higher local drug exposure to systemic methods. |

| Pharmacokinetic profiles after intraperitoneal administration strongly depend on drug properties and administration protocols. |

Introduction

Peritoneal metastases (PM) originate from several cancer types including ovarian, colon, pancreas, and gastric cancer, and are all associated with a poor prognosis [1]. Systemic chemotherapy is considered relatively ineffective against these types of distant metastases, and systemic toxicity limits the maximum tolerable dose [2]. A potential explanation lies in the peritoneal–plasma barrier, which restricts effective transfer of cytotoxic agents from the plasma to the peritoneal fluid and metastases. Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy, whether or not in combination with cytoreductive surgery (CRS), is increasingly used for the treatment of PM in the curative or palliative setting. IP chemotherapy can be administered in several ways [3]. Three main approaches to IP chemotherapy are currently used: catheter-based IP chemotherapy (CBIP), pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC), and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) (Fig. 1). CBIP chemotherapy is administered in cycles through a peritoneal access port at the outpatient clinic (catheter-based IP chemotherapy, CBIP chemotherapy), and is often combined with systemic chemotherapy (bidirectional chemotherapy). PIPAC, on the contrary, is administered during laparoscopy in cycles. Like CBIP, PIPAC can be applied as a palliative treatment for patients with advanced peritoneal disease. Its pressurized aerosolized delivery may enhance drug uptake and allow for deeper penetration into tumor tissue, potentially increasing therapeutic efficacy. While CBIP is routinely used with curative intent in ovarian cancer, particularly following the GOG 172/Armstrong regimen, it has also been explored in the palliative setting for gastrointestinal malignancies such as gastric and colorectal cancer [4, 5]. Although not a common indication, palliative CBIP remains under investigation in clinical trials. Both CBIP and PIPAC offer treatment options for patients with initially unresectable peritoneal disease, with conversion surgery remaining a potentially curative approach in selected cases [5]. Compared with PIPAC, CBIP is less invasive because it does not require repeated laparoscopy and can be administered in an outpatient setting [3].

Fig. 1.

Comparative overview of intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IP) modalities: HIPEC, CBIP chemotherapy, and PIPAC. HIPEC is a single intraoperative treatment using heated perfusate, often combined with cytoreductive surgery. CBIP chemotherapy involves repeated outpatient instillations and enables prolonged drug exposure. PIPAC is a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach delivering aerosolized chemotherapy under pressure, potentially enhancing distribution and tissue penetration. Drug suitability varies by method, with heat-stable, hydrophilic agents favored for HIPEC, while high molecular weight or slow-clearing agents such as paclitaxel and docetaxel are best suited for CBIP chemotherapy. PIPAC shows promise for certain nanoparticles, though clinical data are emerging. *Primarily applicable to patients with stage III ovarian cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy; not generally applicable to recurrent ovarian cancer or gastrointestinal malignancies. **Only patients with limited peritoneal disease that is deemed resectable are eligible for cytoreductive surgery combined with HIPEC

In contrast, HIPEC is a single treatment involving the circulation of heated chemotherapy agents within the peritoneal cavity, typically performed immediately following CRS. CRS combined with HIPEC (CRS-HIPEC) is a potentially curative treatment, but its use is limited to carefully selected, fit patients with limited and resectable peritoneal disease [3, 6, 7].

Peritoneal–Plasma Barrier

The peritoneal–plasma barrier is formed by the tissue surrounding the peritoneal space and covers the abdominopelvic organs and the abdominal wall. The peritoneum consists of a monolayer of mesothelial cells supported by a basement membrane and five layers of connective tissue [8]. This connective tissue includes interstitial cells and a matrix of collagen, hyaluronan, and proteoglycans, along with pericytes, parenchymal cells, and blood capillaries (Fig. 2) [8].

Fig. 2.

Anatomy and structure of the peritoneum. The peritoneum forms the peritoneal–plasma barrier and lines the abdominopelvic cavity, covering the internal organs and abdominal wall. It consists of a single layer of mesothelial cells resting on a basement membrane, underlaid by five layers of connective tissue. This connective tissue contains interstitial cells, a matrix of collagen, hyaluronan, and proteoglycans, as well as pericytes, parenchymal cells, and blood capillaries

The rationale for IP therapy lies in achieving higher local drug concentrations and tumor exposure, enhancing efficacy when a dose-effectiveness relationship exists [8]. The peritoneum retains chemotherapy agents by slow diffusion through the capillary endothelium to the central compartment, resulting in higher IP concentrations compared with plasma. The main barrier to drug diffusion is provided by the capillary endothelium and the cell-matrix system surrounding the vessels in the subperitoneal tissue [9]. While the clinical effectiveness of IP therapy still needs to be validated by ongoing and future clinical trials, the pharmacokinetic profile of IP treatment is generally considered beneficial [3, 10].

Ideally, low peritoneal clearance combined with rapid central metabolism and excretion results in higher concentrations in the peritoneal fluid compared with plasma [11]. This concentration difference increases exposure of peritoneal metastases to cytotoxic drugs, often expressed as the area under the curve (AUC) ratio of IP versus plasma exposure.

Drug Characteristics

For all methods of IP administration, certain drug characteristics can influence treatment PK, such as large molecular weight, hydrophilicity, and rapid systemic clearance. Additionally, factors such as the type of carrier solution, the volume used, and the procedure’s duration can contribute to prolonged retention in the peritoneal cavity. Table 1 provides an overview of important drug characteristics and variables for IP administration.

Table 1.

Important drug characteristics and variables when used for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

| Characteristic | Effect |

|---|---|

| Molecular weight | Large molecular weight molecules remain longer in the peritoneal cavity due to slower absorption |

| Hydrophilicity | Lipophilic molecules cross membranes more easily, enhancing absorption |

| Systemic clearance | Rapid systemic clearance increases the AUC IP/IV ratio, reflecting higher exposure in the peritoneal cavity relative to systemic circulation |

| Drug concentration and volume | Higher drug concentrations create a larger diffusion gradient, increasing membrane transport |

| Carrier solution | Carrier solutions improve drug solubility but may also lead to allergic reactions |

| Duration | Extended treatment duration enhances drug absorption into both tumor tissue and systemic circulation |

| Temperature | Hyperthermia augments cytotoxic effects in drugs with heat-synergistic properties |

AUC area under the curve; IP/IV ratio intraperitoneal versus plasma exposure ratio

Recent advances have been made in the field of IP chemotherapy [12]. However, significant variability exists in treatment schedules, with no standardization for IP chemotherapy protocols regarding temperature, treatment duration, and drug selection. Therefore, we aim to provide an update on the pharmacologic data available concerning various and emerging IP treatment strategies. Our goal is to provide the pharmacologic rationale for the selected IP drugs and their administration methods.

Literature Search Strategy

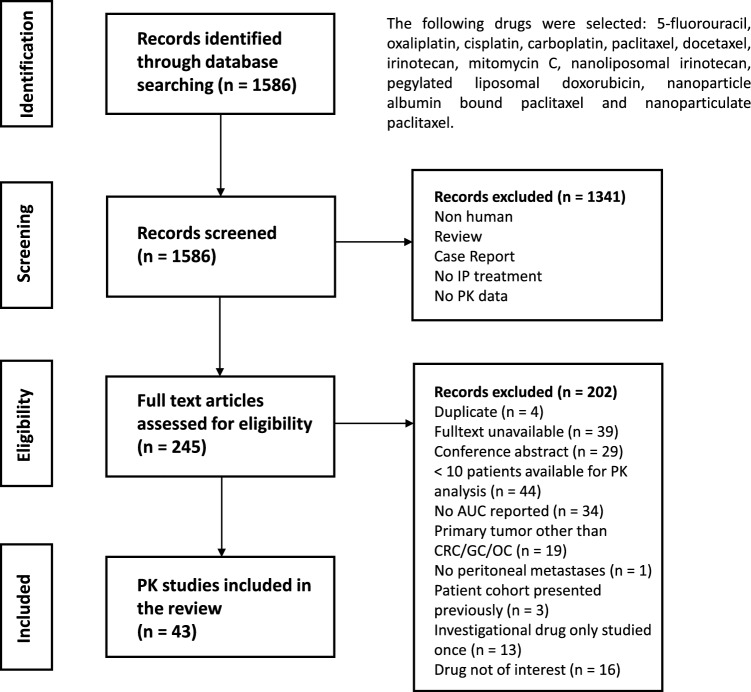

A literature search strategy was performed in Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane for English studies about the pharmacokinetics of the most common IP administered therapies in patients with peritoneal disease originating from colorectal, gastric, or ovarian carcinoma until 28 November 2024. The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table S1. We included clinical studies with a minimum of ten patients eligible for PK sampling and intensive sample collection (minimum five samples per patient) that reported an AUC. The study selection process of the literature search is displayed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Literature search

Anticancer Drugs for Intraperitoneal Use

Table 2 presents the earlier described characteristics and variables of commonly administered chemotherapeutic drugs for intraperitoneal administration. For detailed information on characteristics and variables per administration method (HIPEC, CBIP, or PIPAC), see Supplementary Tables S2–S4.

Table 2.

Key features of drugs typically used in intraperitoneal chemotherapy

| Treatment | Drug | Duration | Size | Hydrophilic | Systemic half-life | Synergy with heat | AUC IP/IV ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIPEC | Oxaliplatin | 30–120 min | 397 g/mol | Yes | 11–16 days (total) | Yes | 9–20 (total) |

| Cisplatin | 60–120 min | 300 g/mol | Yes | 10–60 min (UF), 5 days (total) | Yes | 2.5–28 (UF), 0.25–24 (total) | |

| Carboplatin | 90 min | 371 g/mol | Yes | 2 h (UF) | Yes | 12 (total) | |

| Paclitaxel | 120 min | 854 g/mol | No | 3–53 h | No | 366–1462 | |

| Irinotecan | 30 min | 587 g/mol | Yes | 14 h | No | Not reported | |

| MMC | 60–120 min | 334 g/mol | Yes | 40–50 min | Yes | 10–23 | |

| Nal-IRI | 30 min | 110 nm | Yes | 1.9 days | No | Not reported | |

| PLD | 60–180 min | 100 nm | Yes | 55–75 h | Yes | 600–1390 | |

| CBIP | 5-FU | 130 g/mol | Yes | 10–20 min | Minimal | 18–1000 | |

| Cisplatin | 300 g/mol | Yes | 10–60 min (UF), 5 days (total) | Yes | 30–35 (UF) | ||

| Carboplatin | 371 g/mol | Yes | 2 h (UF) | Yes | 15 (UF) | ||

| Paclitaxel | 854 g/mol | No | 3–53 h | No | 600–1350 | ||

| Docetaxel | 808 g/mol | No | 11–120 h | No | 22–1800 | ||

| Irinotecan | 587 g/mol | Yes | 14 h | No | 35 (irinotecan), 2–5 (SN-38) | ||

| nab-PTX | 130 nm | Yes | 13–27 h | No | 147 | ||

| PLD | 100 nm | Yes | 55–75 h | Yes | Not reported | ||

| Nanoparticulate paclitaxel | 600–700 nm | No | Unknown | No | Not reported | ||

| PIPAC | Oxaliplatin | 397 g/mol | Yes | 11–16 days (total) | Yes | Not reported | |

| nab-PTX | 130 nm | Yes | 13–27 h | No | Not reported |

HIPEC hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy; CBIP catheter-based IP therapy; PIPAC pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy; AUC area under the curve; IP/IV ratio intraperitoneal versus plasma exposure ratio

5-Fluorouracil

Fluoropyrimidines have been effectively utilized across various types of tumors, particularly in gastrointestinal cancers, where they are a critical component of generally used chemotherapy regimens [13]. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) enters the cell directly and is metabolized intracellularly into its active form.

The use of 5-FU has been explored in HIPEC treatment. Studies showed that this small (130 g/mol) hydrophilic molecule rapidly moved from the peritoneal fluid into the plasma, with peak plasma levels reached 15 min post-administration [13, 14]. However, rapid systemic metabolism maintains low plasma concentrations, resulting in high IP/IV AUC ratios of 400–1000 [13, 15]. A therapeutic advantage was observed, with IP exposure being approximately 100 times higher compared with the plasma AUC after the same dose was administered intravenously (IV) [15]. IP concentrations remained elevated for an extended period, still detectable at the 20-h timepoint [15]. The systemic bioavailability following CBIP instillation was around 10% [15]. The IP pharmacokinetics of IP 5-FU were unaffected by prior HIPEC with mitomycin C, in patients with numerous peritonectomies (2–4) [14]. 5-FU has a favorable pharmacologic profile for CBIP therapy, however, its requirement for prolonged exposure to tumor cells makes it a better candidate for CBIP chemotherapy [2].

Oxaliplatin

Oxaliplatin, a relatively small (397 g/mol) hydrophilic drug, is the cornerstone in the treatment of colorectal cancer and has been extensively studied for HIPEC due to its increased cytotoxicity with hyperthermia and effective tumor penetration. Unbound platinum (UF) platinum is considered the active form, binding irreversibly to plasma proteins via a nonlinear process that can be described by a Michaelis–Menten equation [16].

During a 30-min HIPEC procedure, half of the drug is absorbed [17–20]. All platinum in the peritoneal fluid during this period is UF platinum, due to low concentration or absence of proteins [21, 22]. Peak plasma concentrations of oxaliplatin are reached at the end of HIPEC and decrease rapidly [17–19, 22]. The resulting UF plasma AUC (460 mg/m2 HIPEC) is close to that of systemic administration at 130 mg/m2, while peak IP levels were 25-fold higher than plasma levels [17–19]. The extent of the estimated systemic absorption is 38%, which can be potentially explained by high local tissue uptake [17, 23]. Systemic exposure increases with dose but not significantly with the extent of surgery or peritoneal cancer index (PCI) score [16, 17, 23]. The absorption rate from the IP cavity to the plasma is independent of the dose and shows low interpatient variability [20]. UF oxaliplatin is eliminated by both a linear process and the nonlinear process of protein binding [16, 17]. The use of different increasing hypotonic solutions or simultaneous other anticancer agent administration does not change intratumoral or plasma concentrations of oxaliplatin [18, 19]. Additionally, no effect of post-procedural flushing was found on the platinum concentration in peritoneal tissue or blood [22]. Tissue concentrations of oxaliplatin increase with the IP dose, achieving significantly higher levels in directly contacted tissues [17–19]. Although the pharmacological advantage of oxaliplatin for IP use is not as strong as that of other drugs, it remains a good candidate for HIPEC treatment as a result of its synergistic effect with heat.

In addition to its widespread usage in HIPEC, oxaliplatin has also been utilized for PIPAC in recent years. Relatively high plasma concentrations were observed after treatment with PIPAC [24, 25]. The plasma AUC of oxaliplatin after PIPAC approaches that of systemic administration [25]. Compared with HIPEC, the plasma UF AUCs are similar, though the dose of PIPAC is fivefold lower, suggesting a significantly higher systemic uptake [17, 20, 24, 25]. This higher uptake is potentially due to the high concentration in the dialysate, which is ninefold higher than the concentration in HIPEC, subsequently forcing diffusion through the peritoneal plasma barrier [24]. Plasma uptake increased in subsequent PIPAC treatments, potentially due to reduced peritoneal disease and a greater surface area for absorption [25]. However, another study did not observe changes in pharmacokinetics along the PIPAC treatment cycles [24].

The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of PIPAC (140 mg/m2) is lower than the doses used in HIPEC (200–460 mg/m2). While PIPAC achieves similar dose proportional tumor concentrations, HIPEC results in higher absolute concentrations due to larger doses [17, 24]. In conclusion, while PIPAC offers an intriguing method of administration, its pharmacological benefits appear limited. We should await further clinical evidence to assess its full potential.

Cisplatin

Cisplatin, a water-soluble small (300 g/mol) molecule, is commonly used in platinum-taxane combinations for the treatment of ovarian carcinoma [26]. Cisplatin is frequently used for HIPEC and CBIP. It absorbs rapidly into the bloodstream after HIPEC, with plasma bioavailability driven by the concentration gradient [27]. When administered in dosages between 0.8 and 1.5 mg/kg within 4–6 L volumes, cisplatin achieves an AUC (0–1.5 h) IP/IV ratio of 5.9 for total platinum [27]. In another study that extrapolated the IV AUC to infinity, the AUC ratio was 0.25 and 2.5 for total and UF platinum, respectively [28]. There was no effect of the extensiveness of surgery (e.g., peritonectomies) on systemic drug uptake from the peritoneum [27]. During intraoperative IP treatment, IP protein levels, primarily albumin, increase. However, due to high platinum concentrations exceeding binding capacity, IP platinum binding remains low [28, 29]. The elimination of total platinum from serum is slower than that of unbound (UF) platinum, with rates of 0.066 and 0.46 h−1, respectively [28]. Higher intraabdominal pressure enhances cisplatin absorption by 20%, which increases the UF cisplatin plasma peak concentration but not total platinum [30]. The pharmacological advantage of cisplatin, represented by the AUC IP/IV ratio, is not highly favorable for cisplatin (see Table S2). However, similar to oxaliplatin, good tumor penetration and thermal enhancement counterbalance this and make it an attractive drug for HIPEC.

The PK of cisplatin in CBIP is also extensively studied. High systemic exposure to unbound cisplatin correlates with tumor response [31], and systemic exposure to UF cisplatin after IP administration is substantial, with the AUC just below that of IV exposure to the same dose [32]. Cisplatin absorption into plasma continues for 4–5 h after IP administration. However, due to the high reactivity of UF cisplatin, its binding and excretion in the blood outweigh absorption from the IP compartment [32]. Consequently, the Tmax for total cisplatin in plasma exceeds the Tmax for UF cisplatin in plasma [32].

A slightly higher AUC ratio of 30–35 for UF platinum after CBIP was reported previously, compared wtih HIPEC regimens, with sampling both IP and IV up to 24 h post-treatment (see Tables S2 and S3). This reflects the influence of specific treatment protocols, such as not removing the instilled drug and extending the sampling period [33]. The higher AUC ratios observed during CBIP is beneficial, as cisplatin’s potency increases at higher drug concentrations, suggesting cisplatin is a good candidate for CBIP [2].

Carboplatin

Carboplatin is a water-soluble drug with a low molecular weight (371 g/mol) that is rapidly cleared from the systemic circulation [34]. During a 90-min open abdominal HIPEC procedure, the mean IP/IV AUC ratio (0–90 min) for total carboplatin was 12 (range 7.4–17.2) [34]. Plasma concentrations peaked after 90 min of IP treatment and then decreased linearly. When using the infinite plasma AUC to calculate the exposure ratio, it decreases to 3.4 for total carboplatin. Carboplatin also lacks highly favorable pharmacological properties for use in HIPEC, but as for all platinum-based drugs, its heat synergic properties provides some rationale.

Carboplatin CBIP without subsequent removal led to similar AUC ratios (0–2 h) as with HIPEC for unbound platinum, at 14.9 [35]. The drug was rapidly absorbed, with peak concentrations in plasma at 77 min, yet the Cmax ratio was favorable with 42.4 [35]. Miyagi and colleagues compared IP administration of carboplatin with IV administration of a similar dose and volume [36]. Interestingly, the plasma AUC (0–24 h) value of filtrated platinum was the same regardless of the administration route. Additionally, the IP route provided a 17-fold higher exposure in the peritoneal fluid compared with plasma [36]. This suggests that IP administration of carboplatin may be more effective than IV administration if efficacy is AUC-based, as it provides a higher IP AUC while achieving the same IV AUC as IV carboplatin administration. Still, compared with other drugs, carboplatin exerts relatively low pharmacological benefits for IP administration.

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel, a large (854 g/mol) and water-insoluble drug, is suspended in a vehicle to enhance its solubility. This formulation increases the drug’s size and hydrophilic properties, resulting in slow absorption from the peritoneal cavity [8]. However, formulation vehicle Cremophor EL-related severe hypersensitivity reactions have been commonly observed with IV paclitaxel treatment [37]. Nevertheless, the prolonged IP residence time allows the drug to also act on tumor cells undergoing replication at later times, thereby improving efficacy [32]. Paclitaxel is studied for both HIPEC procedures and CBIP.

During a 2-h HIPEC procedure with paclitaxel, maximum IP concentrations were 1178 times higher than plasma peak concentrations, occurring after 2.5 h [38]. IP concentrations remained above the cytotoxicity threshold of 0.1 µmol/L for an average of 2.7 days. Even after the 2-h perfusion, 78% of paclitaxel was still present in the perfusate. The AUC ratio was highly dependent on sampling times, with an AUC ratio of 1462 during HIPEC (0–2 h) and 366 over the total 120-h sampling period [38].

Comparisons of IP and IV concentrations post-HIPEC with those after IV administration showed local drug exposure approximately 50–60 times higher than the total plasma AUC after similar IV administration [38]. The maximum IP concentration post-HIPEC was about 500 times higher than the maximum IP concentration after a 6-h IV administration of the same paclitaxel dose [38]. This high local exposure, coupled with low systemic drug levels, makes paclitaxel particularly suitable for HIPEC.

After CBIP, systemic uptake is about 30%, with paclitaxel remaining in the IP cavity for a significant period, exhibiting an IP half-life of about 14–70 h [32, 39–41]. Plasma peak levels do not reach the cytotoxic threshold of 0.1 µmol/L (85 µg/L), resulting in a high Cmax ratio of ∼7000 and an AUC ratio of 600–1350 [39–42].

Pharmacologically, paclitaxel is an excellent agent for CBIP administration. The slow IP clearance leads to sustained effective concentrations, which is beneficial for cell-specific agents where cytotoxic activity is related to the duration of exposure.

Docetaxel

Docetaxel, with a large molecular weight of 807.9 g/mol, is widely used in the treatment of gynecological cancers. Its cytotoxic activity stems from promoting and stabilizing microtubule assembly while preventing microtubule depolymerization, thereby inhibiting mitotic cell division [43]. Docetaxel’s PK is highly variable, but it shows significant beneficial AUC ratios when administered as CBIP.

The dose influences the AUC IP/IV ratios, between 50 and 100 mg/m2. As the dose increased from 50 to 75 mg/m2, the mean AUC (0–inf) ratio increased from 179 to 284, but did not increase further at the highest dose of 100 mg/m2, where the ratio reached 248 [44]. Similar AUC ratios were observed in another study, where the AUCs, extrapolated to infinity, showed a mean of 181 [45]. Additionally, the mean duration for which the concentration remained above the cytotoxicity threshold of 0.1 µM was 31 h [45]. When AUC ratios were calculated on the basis of data up to 24 h, the mean AUC ratio increased to 515 and the peak plasma concentration was eight times lower than the peak IP concentration [46]. Docetaxel exhibits highly favorable pharmacological properties for IP administration, similar to paclitaxel, making it a strong candidate for CBIP therapy.

Irinotecan

Irinotecan has a relatively high molecular weight (587 g/mol), and is a hydrophilic drug and a widely used chemotherapeutic agent that is converted by carboxylesterases (CES) in the blood, liver, and intestines into its active metabolite, SN-38. SN-38 is up to 1000 times more cytotoxic than irinotecan and is therefore primarily responsible for its anticancer effects.

During HIPEC, the concentration of irinotecan decreases exponentially, with half of the irinotecan (dose-related) absorbed by the end of the 30-min procedure [19]. SN-38 is detectable in the IP solution immediately at the start of the procedure, with peak plasma concentrations of both irinotecan and SN-38 occurring 30 min after starting HIPEC, suggesting IP conversion by CES in the peritoneal cavity. At the same dose, the mean irinotecan plasma AUC of 16.8 µg/mL/h was lower than the plasma AUC for IV administration, which was 24.7 µg/mL/h at 350 mg/m2 [19]. Tumor tissue directly exposed to the treatment had concentrations 16–23 times higher than unexposed muscle tissue. Although intratumoral concentrations increased with the dose, the tumor:muscle ratio did not significantly change across different dosages of IP irinotecan (300–700 mg/m2) [19].

Recently, irinotecan has emerged as a promising agent for CBIP therapies. In a recent phase I study, 50, 75, or 100 mg of irinotecan was added to standard palliative chemotherapy and administered IP to 18 patients with colorectal-origin PM [5]. A rapid IP conversion of irinotecan to SN-38 was observed, indicated by an SN-38 IP Tmax of 2.6 h and an SN-38 AUC (0–48 h) ratio of approximately 4.8 [47]. This was confirmed in an earlier study where the SN-38 peritoneal Cmax was reached earlier than the plasma SN-38 Cmax, with an AUC ratio (0–inf) for SN-38 of about 2 and an AUC ratio (0–inf) for irinotecan of about 35 [48]. The plasma bioavailability of irinotecan after IP administration was estimated to be around 63% compared with dose-normalized IV administration [47]. Furthermore, compared with normal-dose IV administration, plasma exposure to irinotecan was about ten times lower, and SN-38 exposure was six times lower [5]. The local IP conversion of irinotecan to SN-38, combined with low plasma levels of SN-38, makes it a suitable candidate for IP treatment.

Mitomycin C (MMC)

Mitomycin C is another relatively small (334 g/mol) water-soluble drug commonly used to treat PM from various origins, such as colorectal, appendiceal, ovarian, gastric cancers, and peritoneal mesothelioma [49]. It becomes active upon entering the cell [49].

HIPEC regimens of 60–120 min resulted in AUC IP/IV ratios ranging from 10 to 27 [14, 49–51]. Peak plasma concentrations were reached 30–50 min after starting HIPEC [14, 49, 50]. At the end of 60, 90 and 120-min HIPEC treatments, 40%, 60%, and 70% of the initial dose, respectively, had been absorbed during perfusion [14, 49, 50]. Plasma concentrations were cleared with a mean half-life of 84 min [50]. Extensive peritoneal resections resulted in increased plasma AUC and a decreased AUC ratio [14]. The plasma AUC from IP perfusion was 68–74% lower than that from IV administration of the same dose (20 mg/m2) [50]. Mitomycin C’s suitability for IP therapy is due to its water solubility, rapid systemic clearance, and enhanced efficacy with hyperthermia [51].

Nanoparticle-Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel (nab-PTX)

Nab-paclitaxel (nab-PTX) is a 130 nm nanoparticle containing albumin-stabilized paclitaxel and is studied for CBIP and PIPAC. In a study by Cristea and colleagues examining the pharmacokinetics of IP nab-PTX using a CBIP approach, dose escalations were evaluated [52]. At a dose of 140 mg/m2, systemic AUC (0–48 h) was 4.4 mg/L × h, about 2.3 times higher than with PIPAC [53]. A significant pharmacokinetic advantage was observed at every dose level, indicated by a median AUC ratio of 147. Although the AUC ratio of nab-PTX is lower compared with conventional paclitaxel formulations, nab-PTX has the advantage of not requiring the use of toxic cremophor EL.

The PK of PIPAC with nab-PTX was assessed in a phase I study [53]. Patients received three PIPAC cycles with escalating doses ranging from 35 to 140 mg/m2. The nab-PTX aerosol was left in the peritoneal cavity for 30 min before removal. Systemic absorption was slow, with median peak plasma concentrations occurring between 3 and 4 h, and elimination followed a median terminal half-life of approximately 8 h. The plasma AUC (0–24 h) at the MTD of 140 mg/m2 was 1905 ng/mL × h, significantly lower than the AUC observed in historical data for a 30-min IV infusion of nab-PTX at a dose of 135 mg/m2, which was approximately 3.4 times higher [53]. The high molecular weight, slow clearance from the IP cavity, and the lack of need for a carrier solution make nab-PTX a promising candidate for PIPAC.

Nanoparticulate Paclitaxel (Nanotax®)

Nanoparticulate paclitaxel (Nanotax®) is a nanoparticle formulation with particle sizes between 600 and 700 nm, offering a stable reservoir of paclitaxel. This leads to prolonged drug release, enhanced solubilization without the use of cremophor EL, and increased tumor exposure with reduced toxicity [37]. Six doses of Nanotax® (50–275 mg/m2) were administered into the peritoneal cavity over 30–60 min and left in situ. Samples were collected from the peritoneal cavity and IV up to 336 h post-infusion. The IP concentration–time profile showed prolonged paclitaxel exposure, peaking at 56 h and then slowly decreasing over the 2-week sampling period [37]. Plasma concentrations followed a similar PK profile to IP concentrations, with a slow increase and peak concentrations at similar timepoints, reaching a mean peak at 63 h and then slowly decreasing over the 2 weeks. Peak plasma concentrations were low, regardless of the IP dose, indicating a rate-limited clearance of paclitaxel from the IP cavity. The mean Cmax ratio per dose ranged from 450 to 2900, with an average of 1168 across all doses [37]. Compared with conventional IP paclitaxel administrations, the Cmax ratio is similar, but the IP exposure increases, as indicated by a longer time to reach IP Tmax of about 2 days, compared with other trials with conventional paclitaxel where IP Tmax was reached in under 2 h [38, 40, 41].

Nanoliposomal Irinotecan

Despite a promising PK profile, HIPEC with irinotecan often induces high rates of hematological toxicities [54]. Nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI) offers advantages for HIPEC due to its suitable characteristics. The diameter of nal-IRI is 110 nm, which increases retention in the peritoneal cavity.

In a recent study involving patients with appendiceal and colorectal neoplasms, nal-IRI (70–280 mg/m2) was circulated IP in 3 L following CRS using a closed HIPEC procedure for 30 min [54]. After perfusion, nal-IRI was drained, and the residual perfusate was washed out with saline. IV samples were collected up to 72 h to calculate PK parameters. The peak plasma concentrations for irinotecan and its active metabolite SN-38 occurred at 24.5 and 26 h, respectively, for the highest dose level, indicating slow absorption from the peritoneal cavity into the systemic circulation. The irinotecan AUC values were similar for the highest dose levels (140–280 mg/m2), while the SN-38 AUC values did not differ between the first and third cohorts (70 and 210 mg/m2) and the second and fourth cohorts (140 and 280 mg/m2). Compared with historical data of IV administration (70 mg/m2) of nal-IRI, the irinotecan plasma Cmax and AUC after IP administration of the highest dose (280 mg/m2) were 100 and 60 times lower, respectively [54]. Moreover, the SN-38 plasma Cmax and AUC values were nearly two and four times lower, respectively, than IV administration (70 mg/m2) after the highest IP dose (280 mg/m2). These results highlight the benefits of IP administration of nal-IRI, as plasma exposure remains low even at high dosages.

Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin (PLD)

Doxorubicin is a cornerstone in many oncological regimens, but its use is limited by cumulative dose-related cardiotoxicity [55]. Pegylated liposomal formulations were developed to mitigate cardiotoxicity while enhancing tumor exposure. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) is a 100 nm liposomal formulation containing doxorubicin and is studied for HIPEC and CBIP.

In a study involving patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma and PM, PLD (40 mg/m2) was used during a 1-h HIPEC [55]. PLD (total doxorubicin) concentrations in the peritoneal fluid were over two orders of magnitude higher than those in plasma. All detected doxorubicin during HIPEC was encapsulated in PLD [55]. The AUC (−5 min to 1 h) ratio exceeded 1000, and the Cmax ratio was higher than 600 during HIPEC. The number of peritonectomies positively correlated with the AUC and Cmax ratios. Systemic diffusion occurred early, within the first 5 min of PLD injection and before opening the perfusion circuit outflow line. The absence of free doxorubicin exposure indicated that all doxorubicin remained encapsulated within the carrier, preventing diffusion to healthy tissues. Additionally, plasma exposure to PLD was 80–500 times lower compared with IV administration.

Sugarbaker et al. evaluated the PK of different HIPEC regimens (dose, volume, duration) and early postoperative IP chemotherapy (EPIC) with PLD [56]. A 90-min HIPEC regimen with 50 mg/m2 PLD achieved an AUC ratio of 600 with 73% retained in the peritoneal fluid and 27% absorbed into tissue [56]. Doubling the duration to 180 min reduced the AUC ratio to 230 with 60% uptake, and increasing the dose to 100 mg/m2 raised the AUC ratio to 1200 with 32% uptake. Reducing the carrier volume to 2 L improved the AUC ratio to 1390 with 40% uptake. EPIC with 50 mg in 2 L achieved an AUC ratio of 168 and 85% absorption [56]. Because of the slow absorption of the nanoparticle into IP tissues and tumors, HIPEC was concluded to be not suitable. Therefore, when using PLD, CBIP chemotherapy is a more appropriate option.

Discussion

IP chemotherapy presents significant advantages for treating PM by maximizing local drug concentrations and minimizing systemic toxicity. Although IP therapy has been a focus of research for many years, it has not been widely implemented in clinical practice yet, due to limited randomized supporting evidence. Numerous options for IP chemotherapy exist, yet the optimal drug and administration method are yet to be determined.

Key factors for HIPEC drugs include heat stability and synergy, large molecular weight and a structure to limit diffusion into the systemic circulation. Overall, on the basis of the previously defined criteria, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) and mitomycin C (MMC) exhibit many advantageous characteristics. Both are augmented with heat and have a hydrophilic nature. Moreover, PLD is notable for its large molecular size, while MMC benefits from rapid systemic clearance. However, the duration of HIPEC limits the attractiveness of PLD as a candidate and makes CBIP administration a better alternative due to prolonged retention in the peritoneal cavity [56]. Yet, a drawback of CBIP chemotherapy is the loss of the beneficial effects of heat. Furthermore, while platinum-based drugs may not excel in pharmacokinetic profiles compared with other options, their proven cytotoxicity enhancement under hyperthermic conditions and good tumor penetration underscore their potential value in HIPEC applications [57].

CBIP therapy require similar drug characteristics. Larger molecules such as paclitaxel and docetaxel tend to remain in the peritoneal cavity for a longer period of time, enhancing local concentrations and contributing to higher AUC ratios. Thus, for CBIP therapy, high molecular weight drugs, including paclitaxel and various nanoparticles, are promising candidates as a result of their favorable AUC profiles. Interestingly, the smaller molecule 5-FU also demonstrates a high AUC ratio. However, 5-FU is quickly cleared both systemically and from the IP compartment. Since prolonged exposure is thought to be essential for optimal effectiveness, repeated instillations are probably needed to improve its antitumor efficacy [13]. Additionally, irinotecan is a promising candidate for CBIP therapy, given its favorable molecular weight and hydrophilicity, as well as the local conversion in the peritoneal cavity to the active metabolite, which enhances local efficacy.

PIPAC is expected to depend less on drug characteristics than HIPEC or CBIP chemotherapy, as it is hypothesized that the pressure applied during PIPAC forces molecules into the peritoneal tissue, and in the case of oxaliplatin, into the systemic circulation, resulting in high plasma concentrations [25]. However, PIPAC treatment with the large molecular weight molecule nab-PTX showed slow systemic absorption and low plasma levels compared with historical IV administrations as well as CBIP [52, 53]. This highlights that, for PIPAC, drugs with a high molecular weight may offer favorable PK effects.

Concentration and volumes of peritoneal fluid instillate affect the PK and systemic absorption of IP administered chemotherapy. Larger instillate volumes reduce oxaliplatin absorption in the peritoneum and exposed wounded tissues and similarly decrease cisplatin systemic uptake while lowering IP concentrations, potentially weakening antitumor effects [17, 27]. Further, a higher volume can improve distribution through the peritoneal cavity, enhancing tumor exposure.

The type of measurement should always be considered when interpreting PK data for clinical purposes. For instance, with platinum-based chemotherapies, the unbound (ultrafiltered) platinum is considered as the active form of the drug [32]. The peritoneal–plasma ratios of total platinum may underestimate the active platinum ratio due to higher protein binding in blood compared with peritoneal fluid. This underscores the importance of considering both total and active drug concentrations in PK studies.

Surgical interventions, such as peritonectomies and visceral resections, can influence the PK profiles of IP chemotherapy. Extensive resections can increase systemic absorption, reducing the AUC ratio and potentially increasing toxicity, though evidence is conflicting. For MMC, studies show that extensive peritoneal resections increase plasma AUC or IP clearance [14, 49]. Conversely, another study reported no significant impact from peritonectomies on MMC AUC ratios [58]. For platinum-based agents, no significant effect of the extent of surgery on the PK profile was observed either [16, 21, 27]. On the contrary, for PLD, more peritonectomies correlated with higher AUC and Cmax ratios [55]. These discrepancies may be explained by the complex structure of the peritoneum–plasma barrier, which includes the submesothelial stroma and endothelial glycocalyx, rather than just the mesothelial lining [59].

The AUC ratio is a key indicator of drug exposure in the peritoneal cavity versus plasma, but it varies significantly on the basis of sampling times and extrapolation methods. Longer sampling times can lead to lower AUC ratios due to the accumulation of drug in plasma and falling peritoneal concentrations. For instance, differing AUC ratios for mitomycin C and carboplatin originate from extending plasma data to infinity [34, 49, 51]. Additionally, the AUC ratio for 5-FU decreased from 2.3 over 90 min to 0.14 when sampled over 48 h [13, 60]. Thus, it is essential to consider the sampling duration and extrapolation when interpreting PK data from clinical studies. Furthermore, to thoroughly investigate the elimination, it is recommended to collect samples after the end of treatment, ideally extending at least up to 24 h.

IP chemotherapy is a relevant treatment strategy for patients with peritoneal disease due to its ability to deliver high concentrations of anticancer drugs directly into the peritoneal cavity, thereby maximizing local exposure while minimizing additional systemic toxicity. Repeated IP chemotherapy is also emerging as a valuable alternative or addition to conventional palliative, systemic therapy in patients with advanced disease, in whom survival rates have historically been poor. Patients generally tolerate IP administration well as it appears to add little additional toxicity when combined with systemic therapy. Due to its local effect on peritoneal metastases, it may help reduce the symptomatic burden of these metastases, potentially leading to an improvement in quality of life, particularly in the palliative setting. Clinical results have been promising, for instance, the combination of intraperitoneal and intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 has shown significantly improved overall survival in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastases compared with intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 alone, with manageable toxicity profiles [10, 61].

Despite these benefits, several limitations currently hinder the broader implementation of IP chemotherapy. One major gap is the lack of conclusive evidence linking high local (peritoneal) drug exposure to improved intratumoral drug concentrations and overall survival benefit. Furthermore, existing studies show substantial heterogeneity in dosing regimens, chemotherapy agents, and tumor types, often including various primary tumors within the same study. IP chemotherapy is currently used most widely and effectively in ovarian cancer, where its clinical benefit has been clearly demonstrated. For example, a study by Armstrong et al. showed that IP chemotherapy led to improved outcomes compared with standard intravenous chemotherapy in patients with ovarian cancer [4]. For gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, such definitive evidence is lacking, which is the main reason why IP chemotherapy has not yet become part of the standard of care in these tumor types. Still, there are promising early signals suggesting potential benefit, for instance, the DRAGON study in gastric cancer [61]. However, most of the current data on IP chemotherapy originate from studies conducted in Asia, which raises concerns about generalizability to Western populations, where differences in cancer biology, systemic treatments, and diagnostic timing can significantly impact outcomes such as overall survival, warranting further clinical evaluation [61, 62].

To overcome these challenges and advance the field, well-designed phase III clinical trials are needed globally, including in Western populations. These trials should focus on a single tumor type and compare addition of the most promising IP chemotherapy regimen with standard systemic chemotherapy alone. Ideally, they would also explore different IP delivery methods, such as CBIP administration versus PIPAC, in either two-arm or three-arm trial designs. Importantly, future studies should not only evaluate survival outcomes, but also include quality-of-life assessments. Ultimately, the goal is to move toward a more personalized approach to IP chemotherapy, selecting the most effective agents, both based on pharmacological as well as on clinical data.

This review has evaluated the pharmacological properties of commonly IP administered drugs. However, when considering drugs for IP administration, important required features also include proven efficacy against the primary cancer, high tumor penetration, and minimal local toxicity. Future studies should explore the relationship between high IP exposure and treatment response, as well as associated toxicity. Additionally, intratumoral PK should be investigated further. While this article did not specifically address tumor penetration, it is worth noting that oxaliplatin’s low AUC ratio is compensated by its relatively good tumor uptake. The potential of new investigational drugs, such as antibody-drug conjugates and innovative immune therapies, could offer superior pharmacological properties for IP administration due to their larger molecular weights.

Despite the existing rationale for administering IP chemotherapy on the basis of pharmacokinetics, we await further efficacy results from ongoing clinical trials. Advances in nanoparticle formulations and controlled-release technologies hold significant promise for enhancing the efficacy and safety of IP chemotherapy. Continued research on IP chemotherapy, based on a strong pharmacological rationale, is essential to optimizing treatment protocols and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Wichor M. Bramer, PhD, from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing and updating the search strategies. Figures 1 and 2 were created using BioRender.com.

Declarations

Funding

No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Pascale C.S. Rietveld, Niels A.D. Guchelaar, Sebastiaan D.T. Sassen, Birgit C.P. Koch, Ron H.J. Mathijssen, and Stijn L.W. Koolen declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Pascale C.S. Rietveld: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization. Niels A.D. Guchelaar: investigation and writing—review and editing. Sebastiaan D.T. Sassen: supervision and writing—review and editing. Birgit C.P. Koch: supervision and writing—review and editing. Ron H.J. Mathijssen: writing—review and editing and supervision. Stijn L.W. Koolen: conceptualization, investigation, writing—review and editing, and supervision.

References

- 1.Rijken A, van Erning FN, Rovers KP, Lemmens V, de Hingh I. On the origin of peritoneal metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2023;181:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Bree E, Michelakis D, Stamatiou D, Romanos J, Zoras O. Pharmacological principles of intraperitoneal and bidirectional chemotherapy. Pleura Peritoneum. 2017;2(2):47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guchelaar NAD, Noordman BJ, Koolen SLW, Mostert B, Madsen EVE, Burger JWA, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. Drugs. 2023;83(2):159–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S, Copeland LJ, Walker JL, Burger RA, Gynecologic Oncology Group. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):34–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. (PMID: 16394300). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Eerden RAG, de Boer NL, van Kooten JP, Bakkers C, Dietz MV, Creemers GM, et al. Phase I study of intraperitoneal irinotecan combined with palliative systemic chemotherapy in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases. Br J Surg. 2023;110(11):1502–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quenet F, Elias D, Roca L, Goere D, Ghouti L, Pocard M, et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus cytoreductive surgery alone for colorectal peritoneal metastases (PRODIGE 7): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):256–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Schreuder HWR, Hermans RHM, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):230–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugarbaker PH, Van der Speeten K, Stuart OA. Pharmacologic rationale for treatments of peritoneal surface malignancy from colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flessner MF. The transport barrier in intraperitoneal therapy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288(3):F433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishigami H, Fujiwara Y, Fukushima R, Nashimoto A, Yabusaki H, Imano M, et al. Phase III trial comparing intraperitoneal and intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 versus cisplatin plus S-1 in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis: PHOENIX-GC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1922–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedrick RL, Flessner MF. Pharmacokinetic problems in peritoneal drug administration: tissue penetration and surface exposure. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(7):480–7. 10.1093/jnci/89.7.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren K, Xie X, Min T, et al. Development of the peritoneal metastasis: a review of back-grounds, mechanisms, treatments and prospects. J Clin Med. 2022;12(1):103. 10.3390/jcm12010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Speeten K, Stuart OA, Mahteme H, Sugarbaker PH. Pharmacology of perioperative 5-fluorouracil. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(7):730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquet P, Averbach A, Stephens AD, Stuart OA, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Heated intraoperative intraperitoneal mitomycin C and early postoperative intraperitoneal 5-fluorouracil: pharmacokinetic studies. Oncology. 1998;55(2):130–8. 10.1159/000011847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seymour MT, Trigonis I, Finan PJ, Halstead F, Dunham R, Wilson G, et al. A feasibility, pharmacokinetic and frequency-escalation trial of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in high risk gastrointestinal tract cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(4):403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalret du Rieu Q, White-Koning M, Picaud L, Lochon I, Marsili S, Gladieff L, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of peritoneal, plasma ultrafiltrated and protein-bound oxaliplatin concentrations in patients with disseminated peritoneal cancer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion of oxaliplatin following cytoreductive surgery: correlation between oxaliplatin exposure and thrombocytopenia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(3):571–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias D, Bonnay M, Puizillou JM, Antoun S, Demirdjian S, El OA, et al. Heated intra-operative intraperitoneal oxaliplatin after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis: pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(2):267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias D, El Otmany A, Bonnay M, Paci A, Ducreux M, Antoun S, et al. Human pharmacokinetic study of heated intraperitoneal oxaliplatin in increasingly hypotonic solutions after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncology. 2002;63(4):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias D, Matsuhisa T, Sideris L, Liberale G, Drouard-Troalen L, Raynard B, et al. Heated intra-operative intraperitoneal oxaliplatin plus irinotecan after complete resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis: pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and tolerance. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(10):1558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferron G, Dattez S, Gladieff L, Delord JP, Pierre S, Lafont T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of heated intraperitoneal oxaliplatin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62(4):679–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Ruixo C, Valenzuela B, Peris JE, Bretcha-Boix P, Escudero-Ortiz V, Farre-Alegre J, Perez-Ruixo JJ. Population pharmacokinetics of hyperthermic intraperitoneal oxaliplatin in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis after cytoreductive surgery. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong LAW, Elekonawo FMK, Lambert M, de Gooyer JM, Verheul HMW, Burger DM, et al. Wide variation in tissue, systemic, and drain fluid exposure after oxaliplatin-based HIPEC: results of the GUTOX study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2020;86(1):141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Ruixo C, Peris JE, Escudero-Ortiz V, Bretcha-Boix P, Farre-Alegre J, Perez-Ruixo JJ, Valenzuela B. Rate and extent of oxaliplatin absorption after hyperthermic intraperitoneal administration in peritoneal carcinomatosis patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(5):1009–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumont F, Passot C, Raoul JL, Kepenekian V, Lelievre B, Boisdron-Celle M, et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of oxaliplatin delivered via a laparoscopic approach using pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for advanced peritoneal metastases of gastrointestinal tract cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2020;140:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lurvink RJ, Tajzai R, Rovers KP, Wassenaar ECE, Moes DAR, Pluimakers G, et al. Systemic pharmacokinetics of oxaliplatin after intraperitoneal administration by electrostatic pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (ePIPAC) in patients with unresectable colorectal peritoneal metastases in the CRC-PIPAC trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(1):265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zivanovic O, Abramian A, Kullmann M, Fuhrmann C, Coch C, Hoeller T, et al. HIPEC ROC I: a phase I study of cisplatin administered as hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemoperfusion followed by postoperative intravenous platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(3):699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotte E, Colomban O, Guitton J, Tranchand B, Bakrin N, Gilly FN, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cisplatinum during hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy using a closed abdominal procedure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Royer B, Guardiola E, Polycarpe E, et al. Serum and intraperitoneal pharmacokinetics of cisplatin within intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: influence of protein binding. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(9):1009–16. 10.1097/01.cad.0000176505.94175.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royer B, Delroeux D, Guardiola E, Combe M, Hoizey G, Montange D, et al. Improvement in intraperitoneal intraoperative cisplatin exposure based on pharmacokinetic analysis in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61(3):415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusamura S, Azmi N, Fumagalli L, Baratti D, Guaglio M, Cavalleri A, et al. Phase II randomized study on tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of cisplatin according to different levels of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) during HIPEC (NCT02949791). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schellens JH, Ma J, Planting AS, et al. Relationship between the exposure to cisplatin, DNA-adduct formation in leucocytes and tumour response in patients with solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 1996;73(12):1569–75. 10.1038/bjc.1996.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong LAW, Lambert M, van Erp NP, de Vries L, Chatelut E, Ottevanger PB. Systemic exposure to cisplatin and paclitaxel after intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2023;91(3):247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leopold KA, Oleson JR, Clarke-Pearson D, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and regional hyperthermia for ovarian carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27(5):1245–51. 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90550-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikkelsen MS, Blaakaer J, Petersen LK, Schleiss LG, Iversen LH. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of carboplatin used for hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Pleura Peritoneum. 2020;5(4):20200137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jandial DA, Brady WE, Howell SB, Lankes HA, Schilder RJ, Beumer JH, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic study of intraperitoneal bortezomib and carboplatin in patients with persistent or recurrent ovarian cancer: an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(2):236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyagi Y, Fujiwara K, Kigawa J, Itamochi H, Nagao S, Aotani E, et al. Intraperitoneal carboplatin infusion may be a pharmacologically more reasonable route than intravenous administration as a systemic chemotherapy. A comparative pharmacokinetic analysis of platinum using a new mathematical model after intraperitoneal vs. intravenous infusion of carboplatin—a Sankai Gynecology Study Group (SGSG) study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(3):591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson SK, Johnson GA, Maulhardt HA, Moore KM, McMeekin DS, Schulz TK, et al. A phase I study of intraperitoneal nanoparticulate paclitaxel (Nanotax(R)) in patients with peritoneal malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75(5):1075–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Bree E, Rosing H, Filis D, Romanos J, Melisssourgaki M, Daskalakis M, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with paclitaxel: a clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(4):1183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imano M, Imamoto H, Itoh T, Satou T, Peng YF, Yasuda A, et al. Safety of intraperitoneal administration of paclitaxel after gastrectomy with en-bloc D2 lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105(1):43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofstra LS, Bos AM, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG, Willemsen AT, Rosing H, et al. Kinetic modeling and efficacy of intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with intravenous cyclophosphamide and carboplatin as first-line treatment in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85(3):517–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markman M, Rowinsky E, Hakes T, et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal taxol: a gynecoloic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(9):1485–91. 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badgwell B, Ikoma N, Blum M, Wang X, Estrella J, Liu X, et al. Phase 1 trial of intraperitoneal paclitaxel in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and carcinomatosis or positive cytology. Cancer. 2025;131(1):e35566. 10.1002/cncr.35566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamegai H, Kaiga T, Kochi M, Fujii M, Kanamori N, Mihara Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics of docetaxel in gastric cancer patients with malignant ascites. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):727–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor SE, Petschauer JS, Donovan H, Schorzman A, Razo J, Zamboni WC, et al. Phase I study of intravenous oxaliplatin and intraperitoneal docetaxel in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(1):147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan RJ Jr, Doroshow JH, Synold T, et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal docetaxel in the treatment of advanced malignancies primarily confined to the peritoneal cavity: dose-limiting toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(16 Pt 1):5896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fushida S, Kinoshita J, Yagi Y, et al. Dual anti-cancer effects of weekly intraperitoneal docetaxel in treatment of advanced gastric cancer patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis: a feasibility and pharmacokinetic study. Oncol Rep. 2008;19(5):1305–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rietveld PCS, Sassen SDT, Guchelaar NAD, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal irinotecan and SN-38 in patients with peritoneal metastases from colorectal origin. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2024;13(6):1006–16. 10.1002/psp4.13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi MK, Ahn BJ, Yim DS, Park YS, Kim S, Sohn TS, et al. Phase I study of intraperitoneal irinotecan in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma with peritoneal seeding. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Speeten K, Stuart OA, Chang D, Mahteme H, Sugarbaker PH. Changes induced by surgical and clinical factors in the pharmacology of intraperitoneal mitomycin C in 145 patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68(1):147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cerretani D, Nencini C, Urso R, Giorgi G, Marrelli D, De Stefano A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mitomycin C after resection of peritoneal carcinomatosis and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermic perfusion. J Chemother. 2005;17(6):668–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Ruth S, Mathôt RA, Sparidans RW, Beijnen JH, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mitomycin during intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(2):131–43. 10.2165/00003088-200443020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cristea MC, Frankel P, Synold T, Rivkin S, Lim D, Chung V, et al. A phase I trial of intraperitoneal nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced malignancies primarily confined to the peritoneal cavity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83(3):589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ceelen W, Sandra L, de Sande LV, Graversen M, Mortensen MB, Vermeulen A, et al. Phase I study of intraperitoneal aerosolized nanoparticle albumin based paclitaxel (NAB-PTX) for unresectable peritoneal metastases. EBioMedicine. 2022;82: 104151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi M, Harper MM, Pandalai PK, Abdel-Misih SRZ, Patel RA, Ellis CS, et al. A multicenter phase 1 trial evaluating nanoliposomal irinotecan for heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with cytoreductive surgery for patients with peritoneal surface disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(2):804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salvatorelli E, De Tursi M, Menna P, Carella C, Massari R, Colasante A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin administered by intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy to patients with advanced ovarian cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(12):2365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA. Pharmacokinetics of the intraperitoneal nanoparticle pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with peritoneal metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Jong LAW, Elekonawo FMK, de Reuver PR, Bremers AJA, de Wilt JHW, Jansman FGA, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with oxaliplatin for peritoneal carcinomatosis: a clinical pharmacological perspective on a surgical procedure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(1):47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Lima VV, Stuart OA, Mohamed F, Sugarbaker PH. Extent of parietal peritonectomy does not change intraperitoneal chemotherapy pharmacokinetics. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52(2):108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lagast N, Carlier C, Ceelen WP. Pharmacokinetics and tissue transport of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):477–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rietveld PCS, Guchelaar NAD, van Eerden RAG, et al. Intraperitoneal pharmacokinetics of systemic oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and bevacizumab in patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;176: 116820. 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan C, et al. Intraperitoneal and intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 versus intravenous paclitaxel plus S-1 in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis: Results from the multicenter, randomized, phase 3 DRAGON-01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:327. 10.1200/JCO.2025.43.4_suppl.327. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Russo AE, Strong VE. Gastric cancer etiology and management in Asia and the West. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:353–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.