Abstract

This report details a set of three tasks used in an exploratory study of pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) experiences of task design for the mathematics classroom. The three tasks, which I call the Orange Dot Tasks, were constructed in Desmos, a dynamic geometry environment (DGE), and participants engaged each task through manipulating draggable objects on iPad touchscreens. The purpose of this report is two-fold: one aim is to present the tasks in detail and to elaborate on the intentions behind their design and a second is to present some perspectives of PSTs on these tasks generated through their participation in the study.

Keywords: Task design, Dynamic geometry environments, Embodiment, Mathematics teacher education

This report details a set of three tasks used in an exploratory study of pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) experiences of task design for the mathematics classroom. That study focuses on PSTs’ embodied experiences, that is, the roles their bodies play in their task exploration and design; how they perceive, act on, and bring forth affordances in task situations; and their reported experiences. This report focuses on one aspect of this larger study, namely participants’ engagement with three tasks that were provided to participants as an initial provocation at the beginning of each task design session. As described in greater detail below, the three tasks, which I call the Orange Dot Tasks, were constructed in Desmos, a dynamic geometry environment (DGE), and participants engaged each task through manipulating draggable objects on iPad touchscreens. In line with the aims of the larger study, the tasks were not designed to teach or evaluate participants’ conceptual understanding of mathematics, but rather to elicit reports of participants’ sensory and perceptual experiences and provoke their own task designs, which could then be reflected on from the perspective of embodied learning.

The purpose of this report is two-fold. One aim is to present the tasks in detail and to elaborate on the intentions behind their design. A second aim is to present some perspectives of PSTs on these tasks through responses to a questionnaire given to participants of the study described above. The questionnaire was designed to elicit PST reflections of the tasks in the context of embodied task design. In the following sections, I first situate the tasks and the associated study in the emerging field of embodied task design. I then provide a detailed overview of the tasks and their intended affordances. And finally, I present PSTs’ reported experiences of the tasks as part of their participation in the study.

Embodied Task Design

Tasks, which Watson et al. (2013) called the “mediating tools of teaching and learning mathematics,” have long been a focus of mathematics teaching and learning (p. 11). More recently, the body’s role in learning mathematics has become a prominent focus of study for classroom researchers. For example, a recent comprehensive survey of the literature focused on “action-based embodied design” yielded 79 scholarly articles, all published in 2010 or after (Alberto et al., 2022, p. 5). In a specific example, Nemirovsky et al. (2020) investigated students’ sense of kinaesthesia through a task designed to elicit bodily movements in response to arithmetic sums and differences. Embodied task designs like this one have also been taken in up in other mathematical domains, such as trigonometry (Alberto et al., 2019) and proportion (Abrahamson & Bakker, 2016).

Embodied tasks entail a variety of design considerations, including whether or not the task is perception- or action-based (Abrahamson, 2014), is framed by situated or generic contexts (Rosen et al., 2018), or has low or high levels of bodily engagement (Johnson-Glenberg & Megowan-Romanowicz, 2017), among others. Moreover, many embodied tasks draw on the bodily affordances of digital tools, which are a relatively recent and increasingly important phenomenon in the mathematics classroom (see Calder et al., 2018). For example, in a study relevant to this report, Ng (2019) investigated the role of draggable objects in mediating the mathematical thinking of secondary calculus students. This all points to the important role the material environment plays in both designing tasks and engaging them. In work focusing on the connection between embodiment, tool use, and task design, Drijvers (2020), speaking to the multitude of decisions instructional designers must make, noted that the “learning effect of such [embodied] tasks may to an important extent depend on these subtle design decisions” (pp. 14–15). The three tasks described in this report primarily served a pedagogical function, in that they were intended to prompt participants’ own task designs for the mathematics classroom. As such, they were designed to lend themselves to a wide range of mathematical concepts and processes (e.g., graphing, modelling, covariational reasoning, and so on). In what follows, I describe some of the design decisions behind the three tasks.

The Orange Dot Tasks

As noted above, I coined the three Desmos tasks used in this study as the Orange Dot Tasks. This is due to the fact that they share an important feature, an orange dot, that can be manipulated on a touchscreen. This affordance can be brought forth by touching and dragging the orange dot with one’s fingertip or the tip of a digital pencil. The specific design considerations of each task are described in greater detail below, but in general, the process used adhered to Abrahamson’s (2014) embodied design procedure, which entails the processes of phenominalization, concretization, and dialog. Phenominalization involves “crafting a situation amenable to intuitive engagement;” concretization involves “creating a manifestation [of the underlying concept’s] formal structure;” and dialog involves eliciting and guiding a learner’s engagement with the task (Abrahamson, 2014, p. 11). The orange dot tasks, which were conceived of as “warm-ups” to participants’ future design activities, were designed as solicitations for participants to “cast a judgment with respect to some physical, figural, or logical property inherent in [the] materials” (Abrahamson, 2014, p. 3). That is, they were designed as perception-based tasks, and their construction in Desmos is a significant part of the process of phenominalization. Because the overarching study focused on task design, the orange dot tasks served a pedagogical function in addition to a mathematical one. The PSTs who participated in the study did so as task designers. The orange dot tasks thus served as intuitive situations, and participants were asked to be part of the processes of concretization and dialog alongside their own mathematical exploration.

The tasks share features other than the draggable orange dot. They are all designed to be generic task situations (Rosen et al., 2018), which can be seen in their use of simple shapes, such as triangles, squares, and circles, as elements in more complex mathematical relationships. Further, as noted above, the tasks are designed to be perception-based (Abrahamson, 2014), in that they are intended to enlist participants’ primitive knowing (Pirie & Kieren, 1994) and solicit their tentative interpretations of possible mathematical relationships. However, while the tasks are definitively perception-based, in that they do not require actors to align physical movements with mathematical relationships, they do enlist action—grabbing and dragging the orange dot—in service of perceiving their variant and invariant features.

There were three stages to each session: survey, scrutinize, and sequence. In the survey stage, the following prompts were given to participants in a collaborative whiteboard for each of the three Orange Dot tasks:

First drag the orange dot around. Get a feel for it.

Do you see a relationship between the objects on your screen?

How might you represent this relationship(s) visually?

Can you mathematize this relationship any further?

In the scrutinize stage, participants were given two additional prompts through a task-based interview:

What do you think would be critical for students to notice about the task?

What challenges might students have in noticing these critical aspects?

And finally, in the sequence stage, participants were given a final prompt:

Given what you have identified as critical aspects, what might you plan to be the next task in this sequence?

Each participant was given an iPad, with which they accessed the Desmos tasks and a collaborative virtual whiteboard, in which they recorded their work on the prompts together. Participants were all provided Apple pencils to use with their iPads.

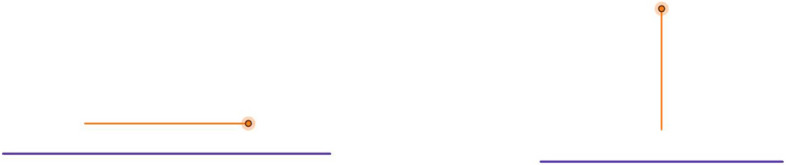

Task 1: Draggable Rectangle

The first of the three Desmos tasks is called Draggable Rectangle.1 When first accessed by participants, all that is present on screen are two dots, one orange and one purple. In this task, the orange dot can be dragged anywhere above or to the right of its original position. Figure 1 shows three frames that capture the possible movements of the orange dot.

Fig. 1.

Draggable rectangle. Note. As the orange dot is dragged up and to the right, the purple line grows. The length of the line is equivalent to the perimeter of the rectangle

This task was design with several key affordances in mind. Firstly, the orange dot can only be dragged up and/or to the right of its original position in order to orient participants towards perceiving the positive association between the size of the orange rectangle, either in terms of area or perimeter, and the length of the purple line. Another intended affordance was centering the rectangle above the purple line, regardless of its size. The intent was to foreground the constant relationship between the two objects. At some point, all participants were drawn into discussion over the boundary cases shown in Fig. 2, which frequently led them to model relationships between the perimeter of the orange rectangle (here shown as either a horizontal or vertical line) and the length of the purple line.

Fig. 2.

Boundary cases

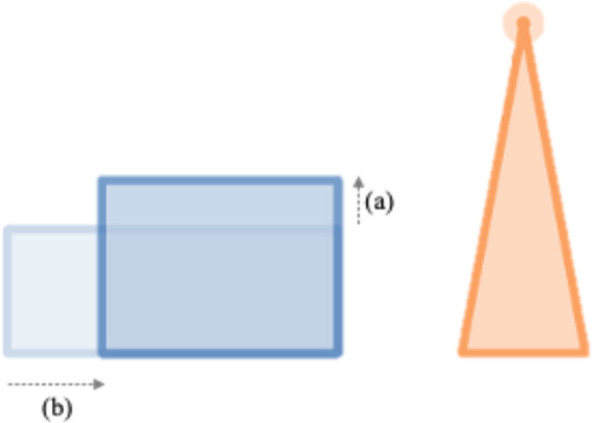

Task 2: Triangle and Rectangle

Similar to Draggable Rectangle, the Triangle and Rectangle2 task allows for the orange dot to be dragged in line with the conventions of the Cartesian plane (e.g., dragging the dot up makes the triangle increase in size, dragging the dot down makes the triangle decrease in size. In this case, a blue rectangle changes in size proportionally to an orange isosceles triangle as the orange dot is dragged either directly up or directly down. Figure 3 shows three frames capturing some possible situations.

Fig. 3.

Triangle and rectangle. Note. As the orange dot is dragged upward, the width of the rectangle also grows

Participants immediately identified the positive relationship between dragging the orange dot to create both a larger orange triangle and blue rectangle. However, one key design feature was to vary the relationship between the base of the orange triangle and the dimensions of the rectangle through the parameter H. As the interested reader can verify through the link provided in Footnote 2, when H is equal to 1, the height of the rectangle and the base of the triangle are equal (see part b in Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Varying the relationship between the triangle and rectangle. Note. As H is increased, the height of the blue rectangle increases (a), and the width of the blue rectangle decreases by h/H, where h is the height of the isosceles triangle (b). This leaves the area of the rectangle invariant for a given h

However, participants were asked to engage with this task at values of H greater than 1, which as the image in Fig. 4 shows, obscures the precise relationship between the two shapes. Specifically, the relationship between the dimensions of the two objects changes for different values of H, but the relationship between the areas of the two objects remains invariant (i.e., the area of the orange triangle is always half the area of the blue rectangle).

Task 3: Circle and Square

The third task in the sequence, Circle and Square,3 introduces some additional affordances. Similar to the Triangle and Rectangle task, an orange dot can be dragged as if along an axis in the Cartesian plane. However, in this case, what one might perceive as the input (the orange dot) is more conventionally located along the horizontal (x-axis). To emphasize this, rather than a 2D shape, dragging the orange dot in this task traces out a horizontal line. The task also introduces a third object: dragging the orange dot effects changes in both a red circle, which first shrinks and then expands as the orange dot is dragged to the right, and a blue square, which shrinks until it disappears. Figure 5 depicts three frames capturing some possible situations.

Fig. 5.

Circle and square. Note. As the orange dot is dragged to the right, the circle first decreases in size and then increases (a quadratic function of the orange line’s length), while the square decreases in size (a negatively-sloped linear function of the orange line’s length)

This third task also introduces a new kind of relationship between objects: the relationship between the circle and the orange line segment is non-linear. The intention behind this, with the circle and square juxtaposed, was to draw participants’ noticing toward how these two objects change together. More specifically, the aim was to elicit participants’ covariational reasoning, which occurs when a “person envisions [changes] in one…variable’s value as happening simultaneously with changes in another variable’s value” (Thompson & Carlson, 2017, p. 217). Understanding how PST covariational reasoning is mediated by the affordances of DGEs is a focus of the ongoing study.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Characterizations of the Orange Dot Tasks

In this section, I report selected results of the four-item questionnaire given to participants at the end of each session. All of the participants were enrolled in a pre-service teacher education program at a large, western Canadian university, and all had either completed or were enrolled in a required course for teaching mathematics. A total of 11 participants engaged with the Orange Dot tasks and they worked collaboratively in groups of 2 or 3. This is not intended to be a rigorous account or analysis of participants’ experiences. Rather, it is intended as a means of putting particular aspects of the tasks into high relief in the context of PSTs’ experiences. Thus, I position the tasks and the questionnaire responses as being in ongoing conversation with each other, as opposed to positioning the latter as a result of some task-based intervention.

The first three questions in the questionnaire were intended to elicit participants’ reflections on some dimensions of embodied task design, namely whether or not they saw the tasks as perception- and/or action-based (Q1), situated and/or generic (Q2), or eliciting a low and/or high degree of embodiment (Q3). Each of these three questions included checkboxes labeled with the relevant terms (e.g., “Action-Based”), as well as the option to select “Both,” “Neither,” or “I don’t know.” Each of these questions was accompanied by a brief explanation of terms to support participants in addressing the relevant aspects of the pre-given tasks and their task designs. A fourth question asked participants to discuss the tools they used and how they used them. Finally, each question provided space for participants to elaborate on their selection.

There are two important points to keep in mind regarding the survey items. First, it is important to note that each of the four items and their supporting explanations attended to complex concepts and ideas, many of which participants are encountering for the first time. The purpose of the questionnaire was not to test participants’ abilities to sort tasks into the correct categories, but rather to elicit discussion and reflection on some of the dimensions of embodied task design. Second, taken as a whole, the items entail a wide range of theoretical commitments at play in the field of embodied task design, some of which might incommensurable. Moreover, important theoretical distinctions are necessarily collapsed for the sake of brevity, as when general movement and movements aligned with mathematical relationships are grouped together in low- and high-level embodiment. In the case of this study, I argue that forgoing theoretical nuance in the questionnaire allowed participants to access a wider range of relevant considerations.

Question 1: Perception- and Action-based Task Situations

Participants were provided with the following information for Question 1:

Some tasks are perception-based, in that they encourage students to offer general impressions of mathematical phenomena. Other tasks are action-based, in that they require certain physical movements to align with mathematical relationships.

Participants were then given the following prompt: Do you think the set of tasks I provided are perception- and/or action-based? A majority of the participants (9 of 11) characterized the task as both perception- and action-based, one participant characterized the task as solely perception-based and another participant characterized the task as solely action-based. As described above, the intended design of these tasks was for them to be perception-based, that is to provide participants opportunities to “discern patterns, identify relationships, or perceive variations” through their naïve perceptions (Wei et al., 2024, p. 6). The single participant who identified the tasks as perception-based did not elaborate on their selection, but the comments of other participants provide some insight into why their experiences of the tasks are so skewed toward action-based.

In some cases, there is evidence to suggest that participants may have conflated action-based tasks, in which sensorimotor action is trained or used to align with a mathematical objective, with tasks involving physical actions. Susan’s response speaks to this idea when she notes that “we had to physically move” the object in the task, a notion echoed by Geena who justified her selection by saying she “had to move the orange dot.” Of course, this may be an artifact of the simplified description of perception- and action-based tasks I provided to participants, but it may also speak to participants’ recognition of the fundamentally embodied ways in which they interacted with the touchscreen and the objects on the screen.

As Abrahamson (2014) noted, action-based tasks are grounded in the idea of embodied interaction, which entails the “creation, manipulation, and sharing of meaning through engaged interaction with artifacts” (Dourish, 2001, cited in Abrahamson, 2014, p. 7). Relatedly, other participants responded in a way that underscored the inextricability of perception and action. For example, Holly justified selecting “Both” by writing that the “way you perceive the movement of the shapes is based on the action that is performed on the dot.” Similarly, Connie, who saw the task as both perception- and action-based, wrote that “you need to do the action in order to perceive the relationship.” That is, while these participants do not address the notion of physical movements directly aligned with mathematical ideas, they do see these types of tasks as intermingling perception and action (Abrahamson, 2014, p. 3).

Question 2: Situated and Generic Task Situations

Participants were provided with the following information for Question 2:

Situated tasks are those that are storied, concrete, rich in context. Generic tasks are asymbolic, abstract, and acontextual.

Participants were then given the following prompt: Do you think the set of tasks I provided are situated or generic? A majority of the participants (7 of 11) characterized the tasks as generic. Holly, in characterizing the task as generic, wrote that the “only concrete aspects I can think of involved our knowledge of shapes. In terms of coming up with visual representations and talking about the relationships, which was the bulk of the task, it was more generalizations or generic.” Holly makes two important insights here: one is that the relationships between objects (e.g., the proportional relationship between the triangle and rectangle) were distinct from the properties of the shapes themselves. The other was noting that her familiarity with the shapes in the task did situate the task to a certain extent, or as she indicated, there was a degree of concreteness.

In fact, this was a notion that emerged in the responses of participants who indicated the tasks as situated. Connie, for example, described the task as situated “because it shows concrete representations of a tangible thing happening.” Kay noted that the “task was rich in allowing the students to create their own understanding of how the task functioned.” Although these participants selected “Situated” in their questionnaire, their elaborations arguably align with more nuanced treatment of the concept of generic, as in Rosen et al. (2018). Those authors wrote that in using the term, they intended situations that eschewed elements traditionally associated with richness (e.g., storying, personal experience); as they put it, by generic, they “are attempting to characterize the difference between a circle and a hot-air balloon” (Rosen et al., 2018, p. 192).

Question 3: Low- and High-level Embodiment Task Situations

Participants were provided with the following information for Question 3:

Low-level embodiment tasks are those in which there is little opportunity for movement and there is little/no alignment between movement and the object of learning. High-level embodiment tasks are those in which whole-body movement is required and explicitly tied to an object of learning.

Participants were then given the following prompt: Do you think the set of tasks I provided have a low or high level of embodiment? A majority of the participants (7 of 11) characterized the tasks as having a low level of embodiment and others (3 of 11) characterized the task as containing elements, at least potentially, of both genres. However, the elaborations provided by participants focused exclusively on movement in general, not movement aligned with particular mathematical actions. For example, Susan justified her decision to characterize the task as low-level by saying that the “task didn’t require us to move out of our seats.” Similarly, Holly wrote that “we were seated while working on the tasks.” When participants highlighted the potential for higher levels of embodiment, they did so with reference to general movement, tools, and pedagogical practices, such as when Gloria noted that students could be “seated for the task or move around (e.g., Smart Board, maybe could be a building thinking classrooms activity).” Participants seem to have interpreted low- and high-level embodiment as “not moving” and “moving,” respectively, and their responses are arguably incongruent with the more nuanced responses they provided in their discussion of action-based tasks in the first question.

Question 4: Tools and Tool Use

Finally, participants were given the following prompt: How do you think the tools you used (e.g., Desmos, touchscreen, etc.) impacted how you engaged with the tasks and your decision-making in your own task design?4 Their responses, in general, underscored a phenomenon I observed in administering the tasks during the study. In every one of the sessions, participants seemed to be hesitant and uncertain as they scanned the QR codes that took them to the first task on their iPads. A common sentiment shared by participants was a lack of confidence in using digital technologies when teaching mathematics, which may account for some of this trepidation. But in each case, the first drag of the orange dot elicited what can only be described as joyful surprise.

A majority of participants spoke to this phenomenon and highlighted the interactivity of the experience. Elizabeth wrote that she “liked being able to manipulate a situation that would be very difficult to provide a manipulative for in real life.” Similarly, Kay wrote that the touchscreen “enhanced how the student is able to perceive how the objects move and their relationship[s].” But some participants also emphasized the need for digital tools to be used carefully. Geena, for example, noted that she enjoyed engaging with the tasks, but with the caveat that in her experience, she has found that “technology that’s not very guided and specific in classrooms can miss the mark on developing mathematical concepts.”

Implications and Ongoing Study

In this short report, I detail three generic, perception-based tasks that were used in a study of task design. I have shared some of the overall design process and some considerations unique to each of the tasks. Finally, I have positioned the tasks in the context of pre-service teachers’ experiences of engaging with them as part of their participation in the task design study. The results detailed in this report, although limited, suggest that one necessary aspect of incorporating embodied learning in mathematics teacher education will be to provide prospective teachers with a rich, nuanced background in the field. This should include identifying the theoretical entailments of different approaches to embodied learning, distinguishing the varied design considerations one must make, and providing opportunities to align embodied tasks with the objectives of the mathematics classroom. Moreover, if the principles of embodied learning are to be effectively adopted in the classroom, mathematics teacher education should develop PSTs’ capabilities to evaluate, modify, and develop embodied tasks in varied contexts, such as the digitally-mediated environments discussed in this report.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Matthew McGarvey for his contributions to constructing the tasks in Desmos and the anonymous referees for their insightful comments and feedback.

Author Contribution

Josh Markle prepared all figures and wrote the manuscript text in its entirety.

Funding

This report draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The Draggable Rectangle task can be accessed at https://www.desmos.com/calculator/hxcmvidvyr. Note that the symbolic constructions are initially visible in Desmos, but participants in this study were encouraged to toggle that feature off by clicking the two arrows at the top left of the expression list.

The Triangle and Rectangle task can be accessed at https://www.desmos.com/calculator/esvcglocv3

The Circle and Square task can be accessed at https://www.desmos.com/calculator/zvix3gvbd9.

Unlike the previous three questions, this question addressed both participants’ experiences of the tasks and their own task design activities. Although I do not address the latter in this report, I have presented the question here as it was given to participants.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abrahamson, D. (2014). Building educational activities for understanding: An elaboration on the embodied-design framework and its epistemic grounds. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction,2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, D., & Bakker, A. (2016). Making sense of movement in embodied design for mathematics learning. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications,1(33), 33. 10.1186/s41235-016-0034-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, R., Bakker, A., Aalst, O. W., Boon, P., & Drijvers, P. (2019). Networking theories in design research: An embodied instrumentation case study in trigonometry. Eleventh Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, R., Shvarts, A., Drijvers, P., & Bakker, A. (2022). Action-based embodied design for mathematics learning: A decade of variations on a theme. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction,32, 100419. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, N., Larkin, K., & Sinclair, N. (Eds.). (2018). Using mobile technologies in the teaching and learning of mathematics. UK: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-90179-4 [Google Scholar]

- Drijvers, P. (2020). Embodied instrumentation: Combining different views on using digital technology in mathematics education. Eleventh Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M. C., & Megowan-Romanowicz, C. (2017). Embodied science and mixed reality: How gesture and motion capture affect physics education. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications,2(24), 24. 10.1186/s41235-017-0060-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemirovsky, R., Ferrara, F., Ferrari, G., & Adamuz-Povedano, N. (2020). Body motion, early algebra, and the colours of abstraction. Educational Studies in Mathematics,104, 261–283. 10.1007/s10649-020-09955-2 [Google Scholar]

- Ng, O. (2019). Examining technology-mediated communication using a commognitive lens: The case of touchscreen-dragging in dynamic geometry environments. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education,17, 1173–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Pirie, S., & Kieren, T. (1994). Growth in mathematical understanding: How can we characterise it and how can we represent it? Educational Studies in Mathematics,26(2/3), 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, D., Palatnik, A., & Abrahamson, D. (2018). A better story: An embodied-design argument for generic manipulatives. In N. Calder, K. Larkin, & N. Sinclair (Eds.), Using Mobile Technologies in the Teaching and Learning of Mathematics (pp. 189–211). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. W., & Carlson, M. P. (2017). Variation, covariation, and functions: Foundational ways of thinking mathematically. In J. Cai (Ed.), Compendium for research in mathematics education (pp. 421–456). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A., Ohtani, M., Ainley, J., Frant, J. B., Doorman, M., Kieran, C., Leung, A., Margolinas, C., Sullivan, P., Thompson, D., & Yang, Y. (2013). Introduction. In Task Design in Mathematics Education. International Commission on Mathematical Instruction. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H., Bos, R., & Drijvers, P. (2024). Developing functional thinking: From concrete to abstract through an embodied design. Digital Experiences in Mathematics Education. 10.1007/s40751-024-00142-z [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.