Abstract

Every cell in the body has a biological sex. The expansion of aging research to investigate female- and male-specific biology heralds a major advance for human health. Unraveling and harnessing mechanistic etiologies of sex differences may reveal new diagnostics and therapeutics for the aging brain.

Introduction

Every cell in the brain has a biological sex that will influence its vulnerability or resilience to aging. Sex influences fundamental biology through gonadal hormones, X chromosome dosage, and Y chromosome functions. These are not just interesting variables; they are powerful sources governing unique genetic expression, epigenetic regulation, and molecular signaling—thus altering cellular processes, metabolism, network functions, neural circuits, and, ultimately, one of our most valued outputs of the brain eroded by aging: cognition. Developing truly effective medicines for the aging brain—for both men and women—will require deeply understanding the potent influences of what underlies sex differences.

In this NeuroView, we focus on sex as a binary system of male and female and use the term sex to refer to sex biology. This raises two notable points. First, the knowledge gained from sex biology can also be expanded to understand divergence, or variation within sexes, in a way that thoughtfully attends to distinctions among individual gender identities, not explored here. Second, in the human condition, gender is inextricable from sex as a source of differences caused by culture and society, and living a lifetime in a gendered world undeniably contributes to cognitive aging. For example, women may undergo more caregiving stress, decreased access to education and employment, and disparities in receiving timely diagnoses. Men may face more occupational stress, delays in seeking healthcare, risk-taking behaviors, and social isolation. These and other experiences of gender may differentially accelerate cognitive aging and are important contributions to sex differences in brain health, which are not explored here.

Male-female comparisons are indeed powerful in biomedical research.1 Neglecting this in the past has not gone well for human health. Research bias persists toward males in preclinical and clinical research, and the historical underrepresentation of women in clinical trials has led to a practice of medicine largely biased against women. For example, women are often overmedicated and suffer excess side effects because clinical trials and prescribed drug dosages are largely derived and calculated from studies done on men.2 If we flagged the lack of knowledge about toxicity or efficacy of drugs and potential for harm in women with a “Pink Box Warning” (a term noted during a teach-in prior to the Women’s March at the University of California San Francisco, 2018), even common medicines would carry caution. In other words, we have not properly assessed whether medicines have differing efficacies, side effects, or pharmacologic responses in women and men. We cannot develop truly effective therapeutics—benefitting both men and women—without careful attention to sex differences. Some medicines may ultimately help one sex and not the other, but even so, that is powerful knowledge that enables a more precise approach to improving human health, with a laser focus on avoiding harm.

Querying sex differences in our brain revolution

We are experiencing a revolution in improving the health of the aging brain with new diagnostics and treatments for age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). We are now asking how sex biology modifies pathophysiology of these age-mediated brain diseases in model systems and whether new diagnostics generalize to both sexes in the human condition. Are new treatments, such as lecanemab and donanemab for AD, as effective in women as they are in men? If not, as some analyses indicate, this must be reported in the spirit of a Pink Box Warning so women can make an informed choice with their physicians about the risk and benefit of taking these new drugs. While the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 requires inclusion of women in federally funded clinical trials, there remain concerning gaps of low representation, particularly in phase 1 toxicity trials. Furthermore, this act of Congress did not mandate that data be disaggregated and analyzed by sex. Thus, data analyses of clinical trials probing the efficacy in women compared to in men are largely omitted. This is a major gap that must be addressed. Unchecked, these limitations will continue to bias drug development. When will we prioritize—even strictly mandate—sex effects as a predetermined outcome measure in clinical trials?

Unraveling sex differences in the biology of brain aging itself, in the absence of neurodegenerative disease, is a major endeavor for science and medicine, with potentially large gains. This is important because typical brain aging is both a major cause of cognitive decline on its own and the biggest risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, modulating cognitive aging may be a pathway to prevent diseases like AD and PD. Since typical brain aging differs by sex, identifying underlying mechanisms of sex-dependent resilience and vulnerability could yield potent, effective, and novel pathways for diagnostics and therapeutics to prevent the ravages of aging on the brain.

What do human data tell us about sex differences in longevity and brain aging?

In every society that records mortality, women live longer than men. The female advantage in lifespan persists in famines and epidemics—and is also remarkably observed as a trend across the animal kingdom. While there is enormous individual variability across and within species in the direction and degree of sex bias in survival, female longevity is notably observed in some strains of inbred3 and genetically heterogeneous4 mice, suggesting common biological underpinnings with humans. Etiologies of female longevity, which include sex chromosomes,3 may also extend to female resilience in healthspan—or the period of time spent in a healthy state. However, female healthspan differs in its resilience and vulnerabilities across the body. For example, women worldwide suffer increased frailty and osteoporosis in aging but show less prevalence of cardiac disease than men.

Growing evidence supports female resilience in brain aging. Brain glucose metabolism in a PET imaging5 study of more than 200 cognitively normal individuals showed that women exhibit a persistently younger metabolic brain age, by nearly 4 years, compared to men. A study by Horvath and colleagues,6 using more than 2,000 brain samples across six studies, found that women undergo slower biological aging by almost 1 year across brain regions, measured by DNA methylation patterns that define the epigenetic clock. This modest but consistent sex effect could potentially amplify resilience against wide-ranging biological mechanisms of aging. Many, but not all, structural brain studies show a female advantage in aging (reviewed in Arenaza-Urquijo et al.7). For example, in a biomarker “brain-predicted age” derived from MRIs of more than 2,000 healthy individuals, female brain aging was more than 7 years younger than chronological age, while male brain aging was more than 8 years older (reviewed in Arenaza-Urquijo et al.7).

The metabolic, epigenetic, and structural findings may provide mechanistic insights into observations that, in many populations, women show resilience to cognitive deficits, often with better baseline memory and verbal fluency, than men in typical aging.7,8 The female cognitive advantage in aging is particularly evident in carefully phenotyped studies that exclude dementia. As an example from more than 1,200 individuals in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, females showed approximately 10%–25% better cognition in aging compared to men 50 years and older.8 It is important to note that since cognition is a highly valued and central manifestation of brain function that decreases with aging and disease, observations of female advantage—even if small to moderate in size—are of large relevance to the human condition. Increased resilience to cognitive aging can amplify improvements in quality of life, independence, and social engagement, which translates to societal benefit, including reduced healthcare burdens, increased innovations, and stronger communities. Identifying the individual or convergent mechanisms underlying sex bias in cognitive aging is thus an important objective.

These and other pioneering studies of sex differences in humans, which may include differing resilience or vulnerabilities, set the stage to probe fundamental mechanisms of brain aging using model systems.

Human sex differences raise high-importance questions for studying brain aging across species

Mechanisms underlying differences in brain aging and cognitive decline within and between sexes remain largely unknown. Remarkably, processes of aging are conserved across the evolutionary spectrum, as are fundamental etiologies of sex biology, enabling the ability to leverage widely disparate systems and models to study sex differences in brain aging. The use of worms, flies, fish, rodents, nonhuman primates, and, of course, humans provides robust approaches. We reason that the more models and species used the better, because where they mechanistically converge may reveal potent and conserved targets for therapeutic manipulation in the human condition.

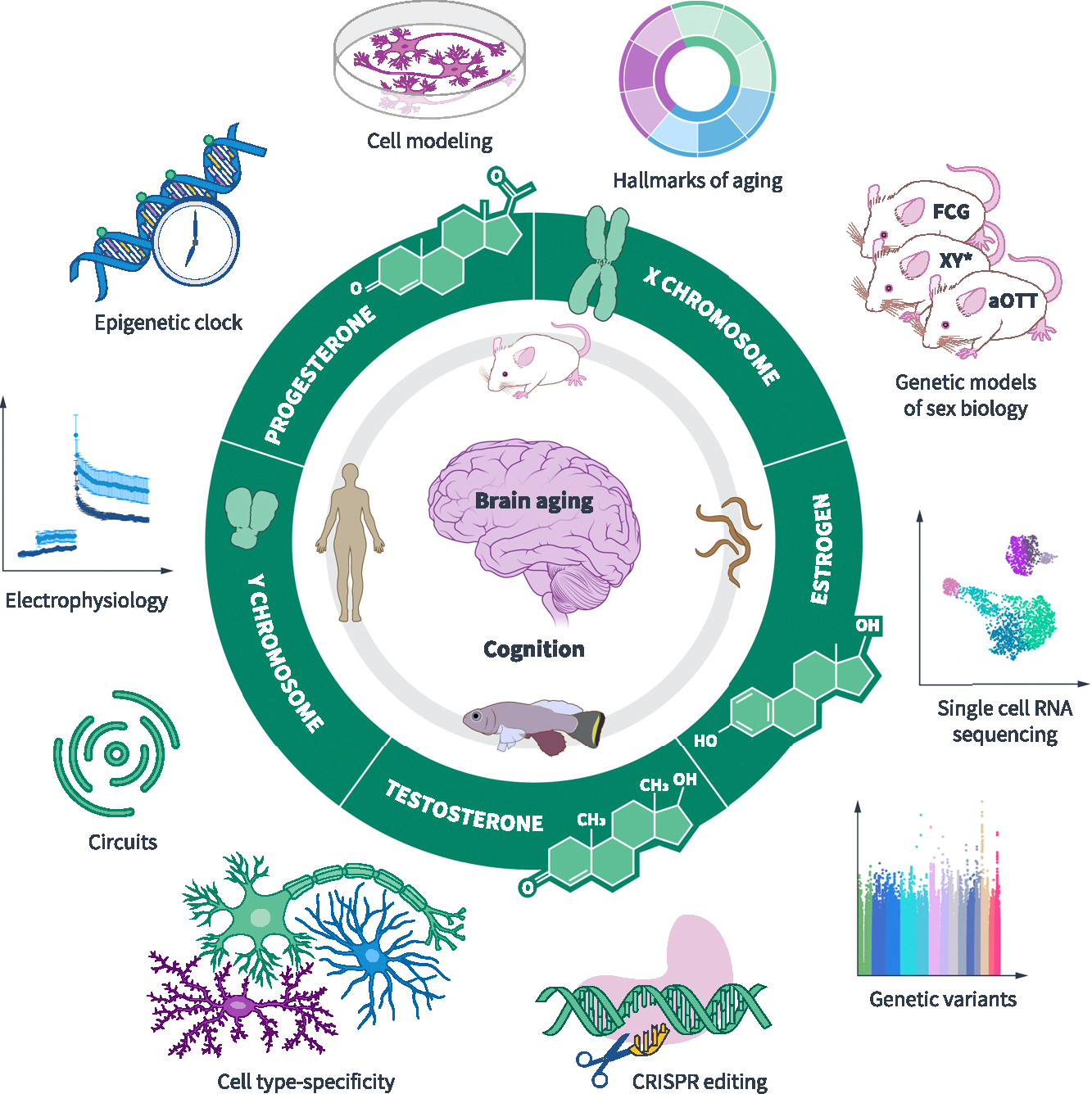

Cross-species analyses of the aging brain to uncover sex differences will yield compelling insights (Figure 1). What are the genetic, epigenetic, molecular, cell-type-specific, electrophysiological, and circuit-level mechanisms that govern sex-specific brain aging? How does sex biology influence the “hallmarks of aging,” including disabled autophagy, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain? For each sex difference, is there a hormonal underpinning? How do the X or Y chromosomes contribute? What are the underlying pathways driving sex differences? How do they relate, or not, to the human condition? Can sex differences in animal models guide studies in humans? Can we modify targets of sex biology with cutting-edge tools like CRIPSR, small molecules, or biologics to induce brain resilience in aging? The answers to these questions, and many more, could be of large gain. If the sex-biology-dependent pathways underlying phenomenon such as female resilience in cognitive aging can be unraveled, they may lead to new medicines that benefit women, men, or both.

Figure 1. Investigating sex differences in brain aging and cognition.

Unraveling sex differences in the biology of brain aging and cognitive decline in humans and across model organisms may reveal potent and conserved targets for treatment of the human condition. Strategies to dissect sex differences include determining whether the X chromosome, the Y chromosome, estrogen, progesterone, or testosterone underlies observed differences. Genetic models of sex biology in mice dissect etiologies of sex differences. Four core genotype (FCG) mice disentangle gonadal versus sex chromosomal effects. When there is a sex chromosomal effect, the XY* mouse model discerns whether the X or the Y chromosome drives the sex difference. The aOTT model assesses how adult testosterone exposure modifies XX mice. Identifying sex differences and their etiologies can apply to studying measures such as hallmarks of aging in the brain. More broadly, cellular, molecular, electrophysiologic, circuitlevel, genetic, and epigenetic studies of the aging brain will identify targets of sex-based resilience or vulnerability. Identifying and then modulating new targets through CRISPR editing, gene therapies, small molecules, biologics, and other interventions may pave the path to new treatments for the aging brains of men, women, or both. Artwork by Elena Kakoshina.

Leveraging our individual expertise in C. elegans, mice, and human model systems, we have each begun to individually and collaboratively study sex-specific brain aging. Here, we communicate a few intriguing model systems used, alongside emerging gaps in the study of sex.

Every C. elegans neuron is XO or XX—and it matters in aging

Like in other species, all neurons in the worm nervous system have a biological sex, which, in the case of C. elegans, is either male (XO) or hermaphrodite (XX). C. elegans undergo cognitive aging with decreased learning and memory, accompanied by neuronal degeneration. In addition, ~70% of worm genes have mammalian homologs, increasing the power of this model to potentially identify mammalian regulators of memory in aging. While research in worms helped pioneer the field of aging, remarkably little is known about their sex differences in aging of the neural system, including learning and memory. In a recent study on this topic,9 the role of biological sex was explored in cognitive aging of worms. In remarkable parallels with female advantage in human cognitive aging7,8 and metabolic brain youth,5 aging XX hermaphrodite worms showed higher indices of learning and memory, neural resilience to age-induced morphological demise, and younger metabolic gene expression, compared to aging XO males. Furthermore, despite mechanisms of dosage compensation that equalize the X chromosome dose between the sexes, aging increased expression of the X chromosome preferentially in neurons of XX hermaphrodites, compared to those of XO males.9 Since the X chromosome is enriched for neural genes in worms,9 increased X expression in XX hermaphrodites may relate to measures of neural resilience in XX aging. When sex differences in model systems recapitulate aspects of the human condition, it is imperative to delve into their mechanistic underpinnings. Could studies of neurons in worms reveal fundamental etiologies of sex differences relevant to human brain aging?

Genetic mouse models of sex biology dissect etiologies of sex chromosomal and gonadal sex difference in brain aging

Genetic models of sex biology in mice transformed the toolbox for rigorously dissecting sex difference across science and are increasingly applied to research in brain aging.3,10 The four core genotypes model disentangles gonadal versus sex chromosomal effects in sex differences. When there is a sex chromosomal effect, the XY* model discerns whether the X or the Y chromosome drives the sex difference. Using these genetic models, female sex increased resilience to cognitive aging, and this effect mapped to both gonads and the second X chromosome.3 Ongoing studies discerning how a second X chromosome imparts brain resilience probe parent-of-X origin10 and the inactive X in modulating sex-specific cognitive aging.

Gonadal hormones are potent sources of sex differences from lifetime exposure and decline in men and women in human aging. Classical paradigms to remove estrogen from females (such as surgical gonadectomy or chemical induction of ovarian failure) model aspects of menopause to assess how loss of estrogen influences cognitive aging in females. Not yet applied outside of gonadal biology studies, a genetic model of adult somatic sex reprogramming allows for the transformation of somatic cells of adult ovaries to testis (aOTT model) through Foxl2-iKO, enabling the dissection of whether adult testosterone exposure in XX females recapitulates sex differences in cognitive aging. Using models such as this, the discovery of long-term and acute gonadal influences in the XX and XY aging brain may yield molecular signaling of hormones in sex-dependent cognitive resilience and vulnerabilities.

The end game of mechanistic dissection of chromosomal and gonadal molecular signaling in cognitive aging is to discover new therapeutic targets, derived from sex biology, to improve brain health in both sexes.

Human observations and the power of human genetics in studying sex differences

Much work lies ahead on the human frontier for observational studies to continue to carefully characterize sex differences in brain and cognitive aging in the absence of neurodegenerative disease. This is complex since neurodegenerative diseases can brew decades before the onset of clinical symptoms. However, the emergence of preclinical biomarkers, such as plasma p-tau217 for AD, may continue to refine the ability of studies to select for individuals undergoing typical aging and exclude those with positive biomarkers that are developing neurodegenerative disease.

While we know from many carefully phenotyped studies that women can show cognitive advantage in aging, in the absence of diseases like AD, we need to know more about the generalizability of these findings across ancestry, socioeconomic status, cognitive domains, and geography. Additional studies on structure, function, and genetics in human brain aging will lay the groundwork for preclinical studies and vice versa.

At long last, large-scale genetic studies are including the X chromosome through “XWAS” analyses for age-related diseases like AD and PD, but studies focused on aging itself are currently lacking. Historically, querying the X chromosome was technically challenging because of limited representation of the X on genotype arrays. Even with X representation, it was biologically challenging for informatic pipelines due to X hemizygosity in men, overlap of X and Y sequences, random X inactivation, and baseline X escape in women. However, tool kits have advanced, and dedicated study of the X chromosome is a newfound focus. This may be an especially fertile ground for important findings because the X represents 5% of the genome in both men and women and is enriched for neural genes in worms,9 mice, and humans.

Much can be discovered from large-scale human genetics, but we are still learning to interpret them. For example, genetic variants associated with human traits are mostly in noncoding regions with often unclear target genes. Part of our collaborative efforts are studies to deeply interpret and drill down on available human genetic data related to aging populations using in silico and cell models—to understand what they portend for sex differences in the aging brain with regard to neural cell-type specificity, hormone-responsive predictions, and X chromosome biology. Human studies are particularly important because, at the end of the day, it’s the human condition we care about, and selecting targets with genetic evidence could dramatically increase the success rate of drug development.

Looking ahead

Biological sex matters in brain aging, and many high-yield discoveries lie ahead. What would happen if we fervently and rigorously tackled etiologies and mechanisms of sex differences in brain and cognitive aging—using a growing and cutting-edge toolbox—across species from worms to humans? What if, based on these discoveries, we identified robust and potent sex-biology-derived therapeutic targets? We would increase equity in brain health, avoid new Pink Box Warnings, and create large gains for science, medicine, and the human condition. Unraveling and targeting male- and female-specific biology in brain aging would ultimately lead us to tackle one of our biggest biomedical problems—cognitive dysfunction—in precise, clever, equitable, and truly effective ways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

D.B.D. received support from the NIA (RF1AG079176 and RF1AG068325), the Simons Foundation (811225SPI), the American Federation for Aging Research, the Bakar Aging Research Institute, and philanthropy. B.A.B. is funded by the Simons Foundation (SF811217), the Hevolution Foundation (HF-GRO-23-1199072-28), the NIA (R01 AG076433), and the NIGMS (R35 GM142395). C.T.M. is funded by the Simons Foundation (811235SPI) and the NIH Office of the Director Pioneer Award (NIGMS DP1GM119167). Y.S. is supported by the Simons Foundation (811249SPI), the NIH (AG017242, DK127778, AG076040, AG06 9750, AG061521, GM104459, AG056278, AG05 7341, AG057433, and AG057706), and the Global Consortium for Reproductive Longevity and Equality at the Buck Institute (GCRLE-1320).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

D.B.D. consulted for Unity Biotechnology and SV Health Investors, serves on the board of the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, and is an associate editor for JAMA Neurology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold AP, Klein SL, McCarthy MM, and Mogil JS (2024). Male-female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research - don’t abandon them. Nature 629, 37–40. 10.1038/d41586-024-01205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zucker I, and Prendergast BJ (2020). Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biol. Sex Differ. 11, 32. 10.1186/s13293-020-00308-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino F, Wang D, Merrihew GE, MacCoss MJ, and Dubal DB (2024). A second X chromosome improves cognition in aging male and female mice. Preprint at bioRxiv. 10.1101/2024.07.26.605328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng CJ, Gelfond JAL, Strong R, and Nelson JF (2019). Genetically heterogeneous mice exhibit a female survival advantage that is age- and site-specific: Results from a large multi-site study. Aging Cell 18, e12905. 10.1111/acel.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal MS, Blazey TM, Su Y, Couture LE, Durbin TJ, Bateman RJ, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Raichle ME, and Vlassenko AG (2019). Persistent metabolic youth in the aging female brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3251–3255. 10.1073/pnas.1815917116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horvath S, Gurven M, Levine ME, Trumble BC, Kaplan H, Allayee H, Ritz BR, Chen B, Lu AT, Rickabaugh TM, et al. (2016). An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome Biol. 17, 171. 10.1186/s13059-016-1030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Boyle R, Casaletto K, Anstey KJ, Vila-Castelar C, Colverson A, Palpatzis E, Eissman JM, Kheng Siang Ng T, Raghavan S, et al. (2024). Sex and gender differences in cognitive resilience to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 5695–5719. 10.1002/alz.13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Mielke MM, Lowe V, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Machulda MM, et al. (2015). Age, Sex, and APOE ε4 Effects on Memory, Brain Structure, and β-Amyloid Across the Adult Life Span. JAMA Neurol. 72, 511–519. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng Y, and Murphy CT (2024). Male-specific behavioral and transcriptomic changes in aging C. elegans neurons. iScience 27, 109910. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.109910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdulai-Saiku S, Gupta S, Wang D, Marino F, Moreno AJ, Huang Y, Srivastava D, Panning B, and Dubal DB (2025). The maternal X chromosome affects cognition and brain ageing in female mice. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-024-08457-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]