Abstract

This study conclusively demonstrated the presence of significant levels of assimilable organic carbon (AOC) in the drinking water distribution system of Bursa Province, utilizing ATP luminescence as a superior alternative to traditional bacterial counting methods. AOC is a critical factor, as it directly serves as a carbon and energy source for heterotrophic bacteria, raising concerns about microbial regrowth in water systems with detectable organic matter. Researchers established a robust calibration curve from the luminescence values of reference bacteria subjected to varying acetate carbon concentrations. This curve effectively transformed maximum luminescence values into precise equivalents of acetate carbon. The results were compelling: AOC concentrations in Zone C1 averaged 133 µgC/L using the traditional cultural methods, while ATP luminescence revealed elevated levels of 188 µgC/L. Despite the correlation coefficient of 0.823 between the two methods, the luminescence approach consistently returned higher AOC values. Crucially, both methodologies confirmed that the AOC levels were more than sufficient to support microbial regrowth within the distribution system. These findings establish ATP luminescence as a highly effective and time-efficient method for AOC assessment, allowing for better management of water quality and proactive measures against bacterial proliferation in drinking water systems.

Keywords: Assimilable organic carbon; ATP luminescent, Biostability; Drinking water

Subject terms: Microbiology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Preserving microbial quality in drinking water distribution systems and controlling biofilm formation is a critical public health concern globally. Despite drinking water meeting microbiological standards at treatment plant exits, its quality can deteriorate during storage and transmission due to the growth of heterotrophic bacteria. This bacterial proliferation can lead to significant issues related to aesthetics, hygiene, and operational functionality (Liu et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2014)1–8. Consequently, global drinking water standards are established to ensure a reliable supply of safe drinking water. The USEPA mandates that the number of heterotrophic bacteria (HBS) in drinking water must be below 500 CFU/mL, however, no allowable value for RLU exists in the USA and Canada4. Additionally, the European Union directive specifies that the number of heterotrophic bacteria in tap water should not exceed 100 CFU/mL. When disinfectant residues are minimal or absent in distribution systems, the primary factor influencing microbial regrowth is the concentration of organic carbon in the water9.

Heterotrophic bacteria thrive within the distribution system, compromising the microbial quality of drinking water by consuming organic matter10–12. Therefore, assimilable organic carbon (AOC)—the portion of total organic carbon easily utilized by bacteria—is recognized as the most critical indicator of microbial growth potential in drinking water (Kaplan et al. 1992)12–15. It is essential to measure and control the levels of organic compounds that support microbial growth to maintain microbial stability in drinking water. While treatment practices—such as coagulation, disinfection, and filter media selection—do influence AOC levels, measurement techniques are often limited by complexity16. However, it is imperative to measure and monitor AOC concentrations at both the treatment plant outlet and within the distribution system using a rapid, straightforward, and reliable method.

Traditionally, the determination of AOC has relied on cultural techniques specified in Standard Methods17. This conventional approach involves inoculating pasteurized water samples with reference bacteria such as Pseudomonas fluorescens P17 (ATCC 49642) and Aquaspirillum NOx (ATCC 49643). The cultural count method maximizes bacterial growth, allowing for AOC calculation through an empirical conversion factor. However, this method is both time-consuming and labor-intensive, prompting research into faster AOC determination methods focusing on inoculum selection, optimization of inoculation and incubation, and measurement of bacterial growth. Several alternative approaches have been explored, including flow cytometry for cell counting18,19 and bioluminescence measurements13,20–23. Among these, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) luminescence measurement has emerged due to its rapidity and efficacy in AOC determination because of it shows biomass activity24–26.

Most previous studies employing ATP assays have been confined to laboratory-prepared or bottled water samples, studies focusing on their application in active drinking water distribution systems remain limited. In this study, ATP luminescence-based AOC measurements were performed on field samples collected from various points throughout the drinking water distribution network, contributing to the existing body of knowledge. Furthermore, the AOC results obtained through ATP luminescence were systematically compared with traditional culture-based methods, and seasonal variations were supported by statistical analyses. In this context, the study aims to demonstrate the reliability and sensitivity of the ATP luminescence method for routine monitoring of microbial regrowth potential.

Methodology

Sampling area

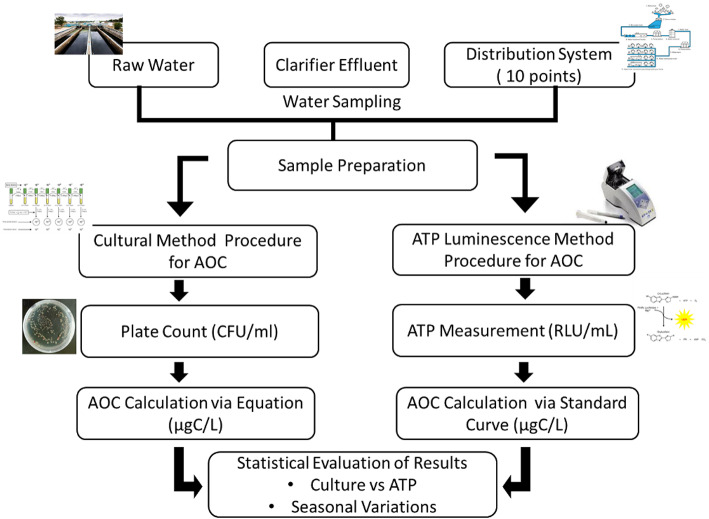

Water samples were collected from 10 points along the C1 transmission line (distribution system, DS), starting at the treatment plant and extending eastward in Bursa city. Additionally, samples from the treatment plant inlet (raw water, RW), clarifier outlet (CE), and treatment plant outlet (PO) were analyzed. Experimental design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparative Flow Diagram of Cultural and ATP Luminescence Methods for Analyzing Assimilable Organic Carbon (AOC) in Water.

Sampling procedure

Samples were collected in 250 mL amber bottles for microbiological analyses and 500 mL amber bottles for chemical analyses. Bottles for microbiological analysis were sterilized in an autoclave at 121 °C and 1.5 atm for 15 min, with 1.25 mL of sterile 3% sodium thiosulfate added afterward. Water was collected from the taps of publicly accessible buildings along the transmission line. Each tap was fully opened for 2–3 min, then closed and flame-sterilized. The taps were reopened, water was allowed to flow briefly, and bottles were filled. Samples were stored at 4 °C and transported to the laboratory within 6 h17.

Determination of heterotrophic bacteria count

Heterotrophic bacteria counts were determined using the pour plate method as specified in standard methods. Plates were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C for 2 days, and colonies on the PCA agar medium were counted17.

Preparation of carbon-free glassware

Carbon-free glass bottles were prepared in order to prevent carbon contamination in the bottles to be used for AOC analysis. The borosilicate bottles (50 mL) were first washed with detergent and then were rinsed three times with ultrapure water. All bottles were subsequently dried, capped with foil, and heated at 550 °C for 5.5 h in a muffle oven to oxidize any residual carbon. Caps were soaked in a 10% sodium persulfate solution at 60 °C for 1 h, then rinsed three times with pure water and left to dry in the air. The bottles and caps were stored wrapped in aluminium foil until used17.

Preparation of inoculum

The amount of AOC in drinking water samples was determined by cultural method specified in Standard Methods17, which uses the Pseudomonas fluorescens P17 (ATCC 49642) and Aquaspirillum NOx (ATCC 49643) strains that are capable of developing in water containing very low levels of organic carbon. The lyophilized Pseudomonas fluorescens P17 (ATCC 49642) and Aquaspirillum NOx (ATCC 49643) bacterial cultures were suspended in 2 mL of filtered and autoclaved water samples. 100 µL of the bacterial suspension was added to 50 mL of filtered and autoclaved tap water in a sterile 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask. To ensure limited organic carbon and complete utilization of acetate carbon, 33.3 µL of a sodium acetate (1 mg acetate C/L) solution was added, and the mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 5–7 days until the maximum cell count was reached. During the incubation period, samples were taken from the stock inoculum and plated to check if the bacterial culture had reached maximum growth. The bacterial count in the inoculum was determined by the spread plate method when maximum growth was reached. Separate inoculum was prepared for each bacterium. The inoculum was stored in the refrigerator, and the bacterial count was checked before each sampling period.

Determination of AOC by cultural method

40 mL sample was transferred into 9 AOC (Assimilable Organic Carbon) bottles, each with a capacity of 50 mL. Any residual chlorine in the water was eliminated using 100 µL (or 1.25 mL/500 mL) of sodium thiosulfate solution. After pasteurizing the AOC bottles at 70 °C for 60 min and then cooling them, bottles were inoculated with an appropriate amount of inoculum, consisting of 500 CFU/mL Pseudomonas fluorescens P17 and 500 CFU/mL Aquaspirillum NOx. The volume of inoculum added is determined using the following equation:

|

1 |

Inoculated water samples were incubated in the dark at 15 °C for 1 week without stirring. On the 7th, 8th, and 9th days of incubation, three bottles were removed from the incubator, and water samples were diluted at ratios of 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4. Each dilution was plated onto R2A agar using the spread plate method in duplicate. After incubating the agar plates at 25 °C for 3–5 days, large cream-yellow colored P-17 bacteria (3–4 mm in diameter) were observed initially, followed by small white spot-like NOx bacteria (1–2 mm in diameter) on the culture medium. The average bacterial count for 7, 8 and 9 days of growth was determined. The AOC concentration was calculated using the conversion rates for Pseudomonas fluorescens P-17 (4.1 × 106 CFU P-17/µ acetate C) and Aquaspirillum NOx (1.2 × 107 CFU NOx/µ acetate C) with the formula given in Eq. 2.

|

2 |

Determination of AOC by ATP luminescence measurement

The determination of AOC through ATP luminescence measurement in water samples was conducted on samples inoculated according to the cultural method. Three bottles of the inoculated samples were retrieved from the incubator on the 7th, 8th, and 9th days of incubation. The total and free ATP luminescence of the samples were assessed using a luminometer. The disparity between these two measurements was computed as bacterial ATP. Subsequently, AOC equivalents were calculated using the standard acetate carbon curve.

Measurement of ATP luminescence

The ATP luminescence measurement in drinking water samples was conducted based on the principle that ATP reacts with the luciferin-luciferase enzyme, leading to the emission of bioluminescent light, which was then quantified using a luminometer. ATP luminescence measurement was made with The Promega BacTiter-Glo™ Microbial Cell Viability Assay (G8231) ATP reagent and Promega Glomax 2020/20 luminometer using the protocol developed for drinking water samples by Hammes et al.27. 500 µL water sample and 50 µL ATP reagent (BacTiter-Glo™ Microbial Cell Viability Assay, G8231; Promega Corporation) were simultaneously heated in Eppendorf tubes at 38 °C for approximately 5 min. Subsequently, 500 µL of the water sample was added to the tube containing the reagent, left for a reaction time of 20 s at 38 °C, and then measured using a luminometer. ATP measurements were performed in triplicate.

To differentiate microbial ATP from extracellular, non-cellular sources, ATP measurements were conducted using a fractionation approach. For each water sample, free (extracellular) ATP was determined by first filtering the sample through a 0.1 µm pore size membrane filter. This filtration step retains intact microbial cells and associated intracellular ATP while allowing extracellular ATP, including ATP released from lysed cells or dissolved in the water matrix, to pass through. Subsequently, total ATP was measured in unfiltered aliquots of the same sample. The bacterial (intracellular) ATP was then calculated by subtracting the free ATP value from the total ATP value. This difference reflects the ATP contained exclusively within viable, metabolically active microbial cells. This three-step procedure allows for the selective quantification of microbial ATP while minimizing interference from non-cellular sources such as natural organic matter (NOM). As reported in previous studies26,28, 0.1 µm filtration effectively separates microbial ATP from NOM and other dissolved contaminants. Therefore, the use of additional blank samples was not required, as the filtration-based fractionation inherently served as a control to isolate signal contributions from non-microbial sources. All measurements were done in triplicate. Specific care was taken that all equipment, consumables and surfaces in contact with the ATP samples were sterilized prior to use.

The preparation of the standard acetate carbon curve

The calibration curve was utilized to determine acetate carbon concentrations corresponding to bacterial ATP luminescence values. Mineral salt buffer solution was prepared by adding 7.0 mg/L K2HPO4, 3.0 mg/L KH2PO4, 0.1 mg/L MgSO4.7H2O, 1.0 mg/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 mg/L NaCl, and 1.8 µg/L FeSO4.7H2O to ultrapure water. The solution was sterilized at 121 °C and 1.5 atmospheres pressure for 15 min in an autoclave.

A 200-mg/L stock solution of acetate carbon was prepared by adding 113 mg of sodium acetate to 100 mL of ultrapure water passed through a 0.22 µm filter (Millipore). Standard acetate curve solutions at concentrations of 0, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 µgC/L acetate carbon were prepared by adding appropriate amounts of sodium acetate solution to 40 mL of mineral solution12,23,29. The acetate carbon concentrations were measured as dissolved organic carbon using a Shimadzu TOC-VCPH TOC analyzer20,23 according to standard method 5310. P17 and NOX bacteria were added to standard curve solutions containing acetate carbon in AOC-free bottles using an appropriate amount of inoculum via a micropipette, with the bacterial count being 1000 CFU/mL. Standard serial solutions inoculated with both bacterial cultures were incubated for 7, 8, and 9 days. At the end of these incubation periods, both ATP luminescence (p17 + NOx/mL) and colony counts on R2A agar (CFU/mL) were measured30. Acetate was chosen as the carbon source for these calibrations (instead of glucose) because it is the standard substrate used in AOC assays, yielding reproducible bacterial growth and allowing results to be expressed as acetate-carbon equivalents. Using acetate ensures comparability with previous studies and standard methods12,14, whereas other substrates like glucose could introduce different bacterial yield coefficients and reduce comparability.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® (SPSS) software (version 22.0) was used for statistical evaluation of the data. The t-test and one way ANOVA with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was employed to determine if there was a significant difference between the means of two groups. Furthermore, Pearson correlation method was applied to determine statistical relationships between two groups.

Results

Calibration curve of reference bacteria

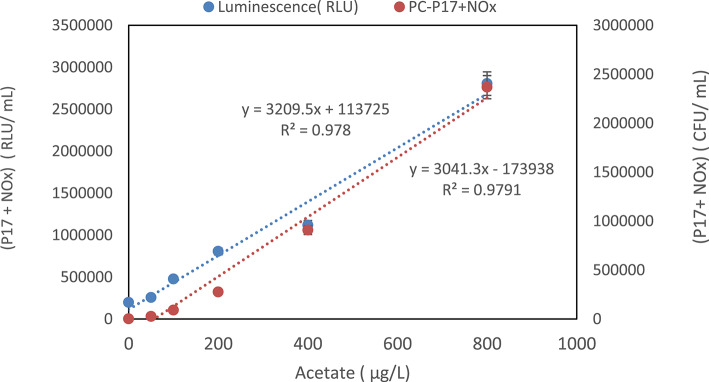

The determination of Assimilable Organic Carbon (AOC) using cultural methods hinges on the growth levels of reference bacteria during their stationary phase and cell transformation rates, as outlined in Eq. (2). To quantify AOC, bacterial ATP luminescence serves as a proxy for microbial activity, where the bacterial ATP measured correlates with the overall AOC. For this approach to replace CFU/mL counts in AOC concentration calculations, understanding the luminescence output from specific reference bacteria in a medium containing acetate carbon is essential14. Thus, the same protocols used in traditional cultural methods were adapted for the ATP luminescence approach. Growth levels, measured as colony-forming units (CFU) and relative light units (RLU), were plotted against selected AOC concentrations. Figure 2 illustrates this relationship, delineating the calibration curve that connects AOC concentrations to growth metrics indicated by CFU and RLU. To ensure accuracy, three replicate ATP luminescence measurements were carried out on all standard serial solutions after incubation periods, followed by calculating the average across 3 days. A series of ten trials were conducted to establish the optimal standard acetate carbon curve, from which the curve exhibiting the highest correlation constant was chosen for AOC assessments. The correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship (0.9780) at the p = 0.01 level between acetate concentration and ATP luminescence in RLU, indicating that maximal bacterial growth corresponded positively with elevated acetate concentrations, as demonstrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of colony counts and ATP luminescence units for Pseudomonas fluorescens P17 and Aquaspirillum NOx grown in acetate.

In addition to ATP luminescence, the maximum colony counts of reference bacteria demonstrated a similar significant correlation with rising acetate concentrations, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.9791 at the p = 0.01 level. Parallel experiments were implemented to test the efficacy of the luminescence method for AOC determination; both methodologies yielded high R2 values, confirming their reliability. Notably, a strong correlation (0.9780) was established between CFU/mL counts and ATP luminescence as acetate concentrations increased. Further analysis revealed an even stronger correlation (0.9791) between ATP luminescence values and acetate carbon concentrations (RLU/mL) corresponding to the same CFU/mL counts, illustrated in Fig. 2. In comparing the culture-based and ATP-based methods, a small difference was observed in their calibration slopes (approximately 3041.3 for the culture-based method and 3209.5 for the ATP-based method), representing a relative variation of about 5%. This minor variation can be attributed to fundamental methodological differences: the culture-based approach quantifies cumulative microbial growth over an extended incubation period, whereas the ATP-based method provides an immediate measure of current metabolic activity. Despite minor discrepancies at lower acetate concentrations, both methods exhibited acceptable analytical performance and strong linear correlations (culture-based method R2 = 0.9791; ATP-based method R2 = 0.9780), confirming consistent and reliable outcomes across the examined concentration range. Collectively, these strong correlations highlight the substantial potential of ATP luminescence as a practical tool for monitoring microbial activity and AOC in diverse environmental contexts.

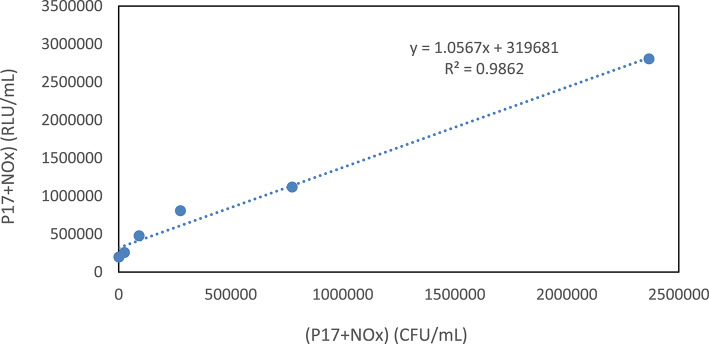

A subsequent examination of ATP luminescence values (RLU/mL) relative to bacterial counts across various acetate concentrations demonstrated an impressive correlation coefficient of 0.9862, also significant at p = 0.01 (Fig. 3). This analysis underscores the significant increase in ATP luminescence as the reference culture proliferates in the presence of acetate, reinforcing the idea that ATP luminescence can reliably serve as a proxy for assessing AOC. The strong correlations identified suggest that ATP luminescence holds substantial potential as a practical tool for evaluating microbial activity and AOC across diverse environmental settings.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between the determined ATP luminescence and the live bacterial count at the selected acetate concentrations for the calibration curve.

Based on the outcomes from our analysis, the equation derived from the calibration curve presented in Fig. 2 was utilized for calculating AOC using ATP bioluminescence. The conversion coefficient was established as 1.17 × 105 RLU/µg acetate-C. This approach aligns with the methodologies used in previous studies, who also calculated AOC levels using a calibration curve developed from bacterial counts in CFU and corresponding ATP luminescence values in RLU.

This consistency in outcomes reinforces the reliability of using ATP bioluminescence as an effective surrogate for traditional AOC measurements. The correlation between the two methods suggests that ATP luminescence can serve as a valuable tool in microbial assessments, providing convenience without sacrificing accuracy in AOC quantification. This advancement could have significant implications for environmental monitoring and management strategies, allowing for more efficient evaluation of microbial activity across various contexts.

AOC levels determined by ATP luminescence method in drinking water samples

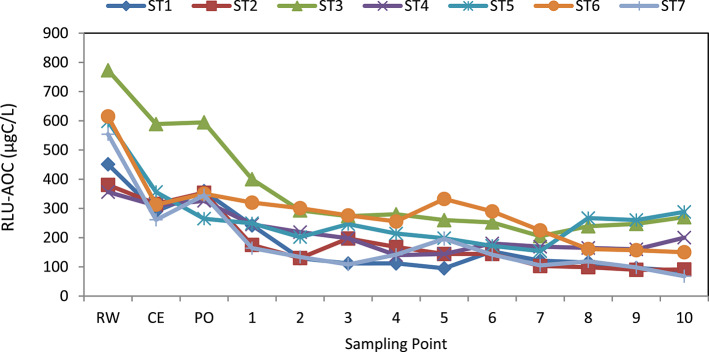

The ATP luminescence measurements obtained from water samples taken at sampling points were used to calculate AOC (RLU-AOC) equivalents using the equation derived from the graph shown in Fig. 2. The calculated results were presented in Fig. 4. Accordingly, the RLU-AOC levels of raw water taken at the inlet of the treatment plant range between 356 and 773 µgC/L, with an average value of 533 µgC/L (n = 7).

Fig. 4.

AOC values determined by ATP luminescence at selected points during the sampling period. RE raw water, CE clarifier exit, PO plant outlet.

Throughout the entire sampling period, the lowest, highest, and average RLU-AOC levels measured at points on the C1 pipeline are 68; 400; and 186 µgC/L, respectively (n = 70) (Fig. 5). The average RLU-AOC values measured in the C1 pipeline for autumn, winter, and spring are 177; 218; and 128 µgC/L, respectively (Fig. 5). Due to the seasonal changes observed in raw water, the C1 pipeline samples have shown variations in AOC values. A one-way ANOVA of the AOC data confirmed that these seasonal differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

The seasonal variation in the average AOC values measured by ATP luminescence at the sampling points. RW raw water, DS distribution system.

AOC levels determined by the cultural method in water samples

The AOC levels determined through cultural methods at all sampling points during the sampling times are presented in Fig. 6. The AOC concentration of raw water taken from the inlet structure of the treatment plant varies between 148 and 525 µgC/L, with an average value of 269 µgC/L (n = 7) during the sampling period.

Fig. 6.

AOC values determined by culturel method at selected points during the sampling period. RE raw water, CE clarifier exit, PO plant outlet.

The lowest, highest, and average AOC concentrations measured at points on the C1 pipeline in the distribution system during sampling period, are 67, 239, and 129 µgC/L respectively (n = 70) (Fig. 6). For the C1 pipeline, 27% of AOC concentrations are below 100 µgC/L, 69% are between 100 and 200 µgC/L, and 4% are higher than 200 µgC/L (n = 70). Across all samples taken from the C1 pipeline, 73% exhibit AOC concentrations exceeding 100 µgC/L). The average AOC values measured in the C1 pipeline for autumn, winter, and spring are 130; 144; and 111 µgC/L, respectively (Fig. 7). Due to the seasonal changes observed in raw water, the C1 pipeline samples have shown variations in AOC values. A one-way ANOVA of the AOC data confirmed that these seasonal differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

The seasonal variation in the average AOC values measured by cultural method at the sampling points. RW raw water, DS distribution system.

Previous studies related to drinking water distribution systems indicate that AOC levels range from 1 to 300 µgC/L1,12,15,31. The values determined in the distribution system samples during the sampling period are consistent with literature values. In a study conducted in China, AOC levels in chlorinated drinking water samples from different distribution networks ranged from 92 to 482 µgC/L1,32 . A study conducted in the drinking water distribution system of Bursa Province found that the AOC concentration decreased from an average of 126.3 µgC/L at a sampling point near the treatment plant outlet to 92.1 µgC/L at the final sampling point1. Thayanukul et al.33 found AOC concentration variations between 36 and 446 µgC/L in chlorinated drinking water in reclaimed water distribution systems. Ohkouchi et al.15 reported average AOC concentrations of 174 µgC/L in winter and 60 µgC/L in summer in chlorinated drinking water. In a study determining the biological stability of a drinking water distribution system, Zhang et al.34 found AOC concentrations ranging from 40.5 to 307.9 µgC/L, with an average of 106.6 µgC/L. Li et al.35 observed AOC values ranging from 25.96 to 429.60 μgC/L between January 2014 and December 2015. These findings demonstrate that the AOC concentrations in the drinking water distribution network of Bursa Province are consistent with values previously established in other studies.

Figure 8 presents the average DOC, AOC, and RLU-AOC values of water samples collected from the distribution system during the autumn, winter, and spring seasons. Seasonal analysis indicates that both DOC and AOC levels reached their highest values during the winter. In spring, although DOC concentrations remained at moderate levels, AOC values showed a substantial decrease. In autumn, both DOC and AOC levels were comparatively lower. Across all seasons, a general trend was observed in which AOC levels varied in parallel with DOC concentrations. These findings suggest that the biodegradable fraction of dissolved organic carbon (AOC) is related to DOC, although this relationship may be influenced by seasonal variability.

Fig. 8.

Seasonal variation of average AOC, RLU-AOC, and DOC concentrations in distrubution system.

Comparison of ATP luminescence measurement method and cultural measurement method

The comparison between the ATP luminescence measurement method and the cultural measurement method reveals significant correlations between the two techniques. As observed in the obtained results, both methods exhibit high R2 values, indicating a strong relationship (Fig. 2). The growth of reference bacteria in acetate medium has been shown to be directly proportional to both the colony-forming units (CFU/mL) and the ATP luminescence values (RLU/mL). This correlation holds true for varying acetate concentrations. The calibration curve generated using known acetate concentrations and corresponding CFU/mL and RLU/mL values demonstrates the consistent relationship between bacterial growth and luminescence. This suggests that the ATP luminescence values can be used as a reliable equivalent to AOC concentration (RLU-AOC). The determination of the conversion coefficient (1.17 × 105 RLU/µg acetate-C) further reinforces the validity of using ATP luminescence to estimate AOC levels.

In converting the measured ATP luminescence units to AOC, the equation provided in Fig. 2 was employed, while the standard equation specified in the cultural method was used for AOC calculation. Figure 7 presents the average AOC values determined using both methods at the selected sampling points throughout the sampling period. These results illustrate that the RLU-AOC values measured by ATP luminescence are consistently higher than the AOC values determined by the cultural method across all sampling points. Although certain values at each sampling time exhibit close proximity between the two methods, the overall trend shows that the AOC values measured by the cultural method are generally lower.

The average values depicted in Fig. 9 reveal that, for all sampling points selected from the C1 pipeline of the distribution line, the overall average AOC value determined by the cultural method (AOC) is 133 µgC/L, whereas the ATP luminescence method (RLU-AOC) yields an average of 188 µgC/L. These findings highlight the consistent trend of higher RLU-AOC values obtained from the ATP luminescence method in comparison to the AOC values obtained from the cultural method, suggesting that the luminescence-based approach provides a more sensitive measurement of microbial activity.

Fig. 9.

The seasonal variation in the average DOC and AOC values measured by cultural method and ATP luminescence at the different sampling points.

The findings are in line with previous studies by LeChevallier et al.14 and Weinrich et al.23, where comparisons between bacterial CFU counts and ATP luminescence values demonstrated statistically insignificant differences when averaged across various AOC concentrations. This underscores the suitability of utilizing ATP luminescence as a valid alternative for AOC determination, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of assessing microbial activity in real water distribution systems.

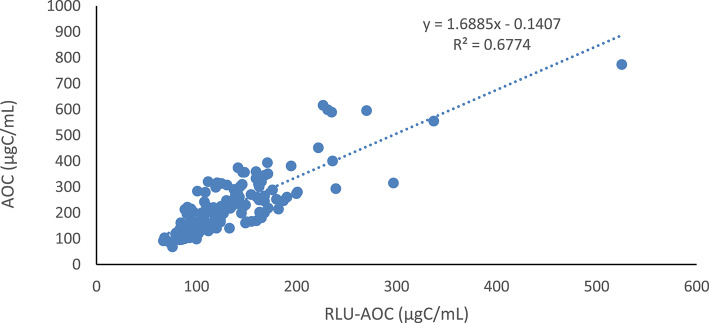

During the preparation of the calibration curve, a strong correlation was observed between the increase in ATP luminescence values of P17 and NOX bacteria and the increase in colony numbers and quantities, at known acetate concentrations (Figs. 2 and 3). However, it can be seen that the correlation between the values measured with both methods at the selected sampling points is lower than that value (Fig. 8). The correlation constant between AOC concentrations determined by the cultural method and ATP luminescence measurement is calculated as r2 = 0.6774.

It is thought that the factor influencing the linear relationship between ATP luminescence measurement and colony counting-based cultural method shown in Fig. 10 is the presence of live (viable) but nonculturable bacteria in the inoculum added to the drinking water. These bacteria cannot grow into colonies in the cultural method-based AOC determination due to their inability to develop in the culture medium. As a result, the count of live bacteria have been significantly underestimated, leading to lower calculated AOC values30. However, in the ATP luminescence measurement-based AOC calculation, the total quantity of nonculturable but live bacteria in the culture medium has been considered. ATP luminescence measurement reveals the intracellular ATP presence of all bacteria in the water8,30,36. Hence, the AOC measurement result obtained in the study is in accordance with this phenomenon. Indeed, in their study with reclaimed wastewater, Weinrich et al.23 determined a correlation of 0.98 between AOC values determined by the cultural method and ATP luminescence. LeChevallier et al.14 emphasized that the results obtained with both techniques are equivalent, but in some cases, they obtained lower AOC values using the cultural method compared to the luminometric method, attributed to plate counting discrepancies. Furthermore, in non-disinfected water samples that had been filtered, both methods yielded more stable results. In this context, when assessing the potential utilization of all organic compounds by microorganisms in water, it is essential to consider the existing active microbial population. After all, bacteria that are biologically active but unable to form cultures may proliferate over time in the water.

Fig. 10.

The relationship between AOC values calculated using cultural methods and ATP luminescence in the examples.

Discussion

This study underscores the potential of ATP luminescence as a sensitive and rapid method for assessing assimilable organic carbon (AOC) in drinking water systems. In line with the study’s aim field samples were collected not only from the treatment plant inlet, clarifier outlet, and outlet, but also from 10 distribution system points. This comprehensive sampling strategy enabled a robust comparison between ATP luminescence and traditional culture-based AOC monitoring.. Rather than focusing solely on numerical correlations already presented, this discussion interprets the broader implications of the findings, emphasizing how luminescence-based detection can offer advantages in both operational contexts and microbial risk assessment.

One of the key strengths of the ATP method is its ability to detect viable but nonculturable (VBNC) bacteria, a population overlooked by traditional culture-based methods. This characteristic allows ATP luminescence to capture the full spectrum of metabolically active microorganisms, contributing to higher AOC readings when compared to culture methods. These higher values are not a discrepancy but a reflection of microbial reality in treated or stressed water systems—an observation supported by prior studies (Lee and Deininger 2001; Wang et al. 2014)30,36–38.

Additionally, seasonal fluctuations in AOC levels—particularly the elevated values observed during autumn and winter—highlight how environmental conditions influence microbial growth potential. These patterns, consistent with previous research15,34, suggest that luminescence-based methods may be particularly suited for detecting short-term or subtle shifts in biological stability, which are critical in distribution systems prone to varying organic loads and disinfection stress.

The ability to generate a precise and reproducible calibration curve using ATP luminescence adds another layer of reliability to this method. While the “Results” section established its statistical validity, the practical implication is that ATP luminescence could become a standardizable method for water utilities aiming to monitor biological stability with greater frequency and less labor than classical methods allow. However, the implementation of this method is not without challenges. Equipment availability, cost, and the need for protocol optimization (e.g., ATP extraction efficiency, background correction) remain barriers to widespread adoption. Yet, these limitations can be mitigated with standardized kits and operator training.

In conclusion, the ATP luminescence method has emerged as a more comprehensive and sensitive indicator of microbial activity in the drinking water distribution system of Bursa Province. In addition to its speed, ease of application, and high sensitivity in detecting microbial activity, its alignment with the proactive monitoring goals set by regulatory authorities makes it a strong alternative to conventional AOC determination methods. In this respect, the study clearly fulfills the objective initially set forth.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Kübra Taşkın, M.Sc., for her assistance with the laboratory work.

Author contributions

A.T. conceived and designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. The author reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author extends her appreciation to The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBİTAK) for funding this research work through project number 119Y052.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alkan, U., Teksoy, A. & Acar, Ö. Identification of factors affecting bacterial regrowth in drinking water distribution systems. ITU J. Water Pollut. Control15(1–3), 43–55 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, S. H., O’connor, J. J. & Banerji, S. K. Biologically mediated corrosion and its effects on water quality in distribution systems. J. AWWA72(11), 636–639. 10.1002/j.1551-8833.1980.tb04600.x (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy, R., Hart, F. L. & Cheetham, R. D. Public health significance of in drinking water. J. AWWA78(9), 105–111. 10.1128/aem.47.5.889-894.1984 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu, X. et al. Effects of assimilable organic carbon and free chlorine on bacterial growth in drinking water. PLoS ONE10, 1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128825 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prest, I. E., Hammes, F., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Vrouwenvelder, J. S. Biological stability of drinking water: Controlling factors, methods, and challenges. Front. Microbiol.7, 1–24. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00045 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwake, D. O., Garner, E., Strom, O. R., Pruden, A. & Edwards, M. A. Legionella DNA markers in tap water coincident with a spike in legionnaires disease in flint, MI. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett.3, 311–315. 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00192 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Kooij, D. & Hijnen, W. A. Substrate utilization by an oxalate-consuming spirillum species in relation to its growth in ozonated water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.47, 551–559. 10.1128/aem.47.3.551-559 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, Q., Tao, T., Xin, Kun-lun., Li, S. & Zhang, W. A review research of assimilable organic carbon bioassay.Desalination and Water Treatment. 52(13–15), 10.1080/19443994.2013.830683 (2014)

- 9.Mesquita, S. & Noble, R. T. Recent developments in monitoring of microbiological indicators of water quality across a range of water types. In Water Resources Planning, Development and Management (ed. Wurbs, R.) (InTech, 2013). 10.5772/52312. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escobar, I. C., Randall, A. A. & Taylor, J. S. Bacterial growth in distribution systems: Effect of assimilable organic carbon and biodegradable dissolved organic carbon environmental. Sci. Technol.35(17), 3442–3447. 10.1021/es0106669 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lautenschlager, K. et al. Microbiology-based multi-parametric approach towards assessing biological stability in drinking water distribution networks. Water Res.47, 3015–3025. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.03.002 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Kooij, D. Assimilable organic carbon as an indicator of bacterial regrowth. J. Am. Water Works Assoc.84(2), 57–65. 10.1002/j.1551-8833.1992.tb07305.x (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan, L. A., Bott, T. L. & Reasoner, D. J. Evaluation and simplification of the assimilable organic carbon nutrient bioassay for bacterial growth in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.59(5), 1532–1539. 10.1128/aem.59.5.1532-1539.1993 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeChevallier, M. W., Shaw, N. E., Kaplan, L. A. & Bot, T. L. Development of a rapid assimilable organic carbon method for water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.59(5), 1526–1531. 10.1128/aem.59.5.1526-1531.1993 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohkouchi, Y. et al. A survey on levels and seasonal changes of assimilable organic carbon (AOC) and its precursors in drinking water. Environ. Technol.32(14), 1605–1613. 10.1080/09593330.2010.545439 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinrich, L. A., Schneider, O. D. & LeChevallier, M. W. Bioluminescence-based method for measuring assimilable organic carbon in pretreatment water for reverse osmosis membrane desalination. Appl. Envıron. Microbiol.77(3), 1148–1150. 10.1128/AEM.01829-10 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.APHA, AWWA, WPCF. Standard Methods for the Examination of the Water and Wastewater 18th edn, 1193–1200 (American Public Health Association, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elhadidy, A. M., Van Dyke, M. I., Peldszus, S. & Huck, P. M. Application of flow cytometry to monitor assimilable organic carbon (AOC) and microbial community changes in water. J. Microbiol. Methods130, 154–163. 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.09.009 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammes, F. et al. Mechanistic and kinetice valuation of organic disinfection by-product and assimilable organic carbon (AOC) formation during the ozonation of drinking water. Water Res.40(12), 2275–2286. 10.1016/j.watres.2006.04.029 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddix, P. L., Shaw, N. J. & LeChevallier, M. W. Characterization of bioluminescent derivatives of assimilable organic carbon test bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.70, 850–854. 10.1128/AEM.70.2.850-854.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong, S., Naidu, G., Vigneswaran, S., Ma, C. H. & Rice, S. A. A. Rapid bioluminescence-based test of assimilable organic carbon for seawater. Desalination317(5), 160–165. 10.1016/J.DESAL.2013.03.005 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Kooij, D. Assimilable organic carbon (AOC) in treated water: Determination and significance. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology (ed. Bitton, G.) 312–327 (Wiley, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinrich, L. A., Giraldo, E. & Lechevallier, M. W. Development and application of bioluminescence-based test for assimilable organic carbon in reclaimed waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.75(23), 7385–7390. 10.1128/AEM.01728-09 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, G. Q., Yu, T., Wu, Q. Y., Lu, Y. & Hu, H. Y. Development of an ATP luminescence-based method for assimilable organic carbon determination in reclaimed water. Water Res.123, 345–352. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.06.082 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Kooij, D., Vrouwenvelder, H. S. & Veenendaal, H. R. Kinetic aspects of biofilm formation on surfaces exposed to drinking water. Water Sci. Technol.32, 61–65. 10.1016/0273-1223(96)00008-X (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velten, S., Hammes, F., Boller, M. & Egli, T. Rapid and direct estimation of active biomass on granular activated carbon through adenosinetri-phosphate (ATP) determination. Water Res.41, 1973–1983. 10.1016/j.watres.2007.01.021 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammes, F., Berger, C., Koster, O. & Egli, T. Assessing biological stability of drinking water without disinfectant residuals in a full-scale water supply system. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.59(1), 31–40. 10.2166/aqua.2010.052 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammes, F., Goldschmidt, F., Vital, M., Wang, Y. & Egli, T. Measurement and interpretation of microbial adenosine tri-phosphate (ATP) in aquatic environments. Water Res.44, 3915–3923. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.04.015 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeChevallier, M. W., Welch, N. J. & Smith, D. B. Full-scale studies of factors related to coliform regrowth in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.62(7), 2201–2211. 10.1128/aem.62.7.2201-2211.1996 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocha, V. S. Determination of assimilable organic carbon in drinking water. Environ. Monit. Assess.10.1007/s10661-012-2642-9 (2007).18058033 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escobar, I. C., Andrew, A. & Randall, A. A. Sample storage impact on the assimilable organic carbon (AOC) bioassay. Water Res.34(5), 1680–1686. 10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00309-7 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, W. et al. Investigation of assimilable organic carbon (AOC) and bacterial regrowth in drinking water distribution system. Water Res.36, 891–898. 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00296-2 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thayanukul, P., Kurisu, F., Kasuga, I. & Furumai, H. Evaluation of microbial regrowth potential by assimilable organic carbon in various reclaimed water and distribution systems. Water Res.47, 225–232. 10.1016/j.watres.2012.09.051 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, J. et al. Exploring the biological stability situation of a full scale water distribution system in South China by three biological stability evaluation methods. Chemosphere161, 43–51. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.06.099 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, W. et al. Effect of disinfectant residual on the interaction between bacterial growth and assimilable organic carbon in a drinking water distribution system. Chemosphere202, 586–597. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.056 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, J. & Deininger, J.A. Rapid quantification of viable bacteria in water using an ATP assay. American Lab.33, 24–26 (2001).

- 37.Sanna, T. et al. ATP bioluminescence assay for evaluating cleaning practices in operating theatres: Applicability and limitations. BMC Infect. Dis.18(1), 583. 10.1186/s12879-018-3505-y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Kooij, D. Assimilable organic carbon (AOC) in drinking water: progress and recent development. In Drinking Water Microbiology (ed. McFeters, G. A.) 57–87 (Springer, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vang, O. K., Corfitzen, C. B., Smith, C. & Albrechtsen, H. J. Evaluation of ATP measurements to detect microbial ingress by wastewater and surface water in drinking water. Water Res.64(1), 309–320. 10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.015 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao, X. et al. Improvement of the assimilable organic carbon (AOC) analytical method for reclaimed water. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng.7(4), 483–491. 10.1007/s11783-013-0525-0 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.