Abstract

3D bioprinting has emerged as a promising technology in tissue engineering, allowing for the precise fabrication of complex structures to mimic native tissues. Coaxial bioprinting enhances the complexity of printed structures by extruding multiple materials in concentric layers. However, costly commercial systems and a lack of Do-it-Yourself (DIY) guides for coaxial 3D bioprinting limit the wider adoption of this technology. This study presents a detailed description of modifying a commercial 3D printer to a coaxial 3D bioprinting system that simultaneously drives two syringe pump extruders connected to a coaxial nozzle. The system was validated using a soft alginate-gelatin hydrogel core and a load-bearing methylcellulose-based (MC) hydrogel shell. Shape fidelity of the 3D printed structures was evaluated for core-shell extrusion ratio, coaxial nozzle configuration, and in-situ crosslinking of the hydrogel core. Employing optimized printing settings allowed the fabrication of complex scaffold structures with a gradual transition between the extrusion of core and shell material. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) encapsulated in varying alginate concentrations were printed, maintaining shape fidelity and high cell viability. In conclusion, we developed a cost-effective DIY coaxial 3D bioprinter capable of extruding soft cell-laden hydrogels that are not printable by conventional extrusion bioprinting. This printer presents an easy to build and modify platform to encourage a wider audience to utilize and tailor coaxial bioprinting for their specific requirements.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, DIY bioprinting, Coaxial 3D extrusion bioprinting, Bioink, In-situ crosslinking

Subject terms: Biomaterials, Gels and hydrogels

Introduction

3D bioprinting has emerged as a promising technology, allowing the layer-by-layer construction of three-dimensional structures to replicate the architecture of native tissues1,2. Among the different techniques, such as jetting-based and VAT-based bioprinting, extrusion-based bioprinting is the most used due to its affordability, and capability to print multiple cell types and materials simultaneously3–6. Central to the bioprinting process are bioinks, which are formulations of cells encapsulated within a material that can be processed by an automated fabrication technology7. Bioinks must balance different critical yet opposing properties, maintaining printability and shape fidelity while supporting the viability and function of the embedded cells, a concept illustrated as the “biofabrication window”8. Shear-thinning hydrogels are amid the materials used for extrusion bioprinting6,9. They provide a hydrated and mechanically supportive environment while protecting encapsulated cells from shear forces during nozzle extrusion.

Traditionally, the mechanical properties of hydrogels for bioprinting are adjusted via concentration or molecular weight2. This enables the fabrication of stable, volumetric structures; however, it may impair the viability and mobility of cells within the hydrogel. Strategies to allow the printing of softer gels into more complex structures, include gel in gel printing techniques like FRESH10, jammed microgels11, and coaxial bioprinting12,13. Among these strategies, coaxial bioprinting has emerged as a particularly promising technique for increasing the complexity of fabricated tissue scaffolds and enabling the use of soft functional hydrogels in bioprinting12,14. Coaxial bioprinting enhances the versatility and complexity of printed tissue constructs by enabling the simultaneous deposition of multiple biomaterials in concentric layers. Such constructs can integrate diverse cell compositions15, promote in-situ crosslinking16,17, pattern extracellular matrix (ECM) components18, fabricate stimulus-responsive scaffolds19, control the release of bioactive factors20,21, create hollow fibers for engineering blood vessels22,23, and create multi-material gradient profiles17. Another key advantage of coaxial bioprinting is the ability to print a high cell density, soft core hydrogel surrounded by a mechanically stable shell24–26. This capability significantly expands the range of printable bioinks, opening new avenues for the development of functional tissue constructs.

There are several commercial coaxial extrusion bioprinters available12. These bioprinters are usually equipped with a coaxial nozzle kit provided by the manufacturer, which comes in a fixed design, providing limited versatility. One must consider the narrower range of bioinks that are compatible with the confined geometry of a coaxial needle. Heterogeneous biomaterials that contain bioactive fillers, such as  -TCP, or microparticle thickeners may have a higher rate of clogging in the coaxial needle given the geometrical restrictions27. Moreover, the bioink flow properties, shear stress, and cell viability are strongly influenced by the specific geometrical features of the nozzle28,29. The effect of nozzle geometry and material properties are not always separable but rather influence the shear stress response along with other flow properties in a combinatorial way. The ideal coaxial nozzle design can greatly change with the selection of bioinks, thus a single coaxial nozzle design fitting all applications does not exist. Moreover, commercial bioprinters that offer coaxial printing capabilities are often expensive for university facilities and research labs. These factors can challenge the wider adoption and use of coaxial bioprinting technology.

-TCP, or microparticle thickeners may have a higher rate of clogging in the coaxial needle given the geometrical restrictions27. Moreover, the bioink flow properties, shear stress, and cell viability are strongly influenced by the specific geometrical features of the nozzle28,29. The effect of nozzle geometry and material properties are not always separable but rather influence the shear stress response along with other flow properties in a combinatorial way. The ideal coaxial nozzle design can greatly change with the selection of bioinks, thus a single coaxial nozzle design fitting all applications does not exist. Moreover, commercial bioprinters that offer coaxial printing capabilities are often expensive for university facilities and research labs. These factors can challenge the wider adoption and use of coaxial bioprinting technology.

In recent years, the Do-it-Yourself (DIY) community has made great efforts to democratize bioprinting technology by offering more affordable alternatives to commercial bioprinters30. Leveraging open-source software and a plethora of modification guides, research labs can equip themselves with bioprinters tailored to their specific needs. DIY extrusion bioprinters range from simple, inexpensive systems that are easy to modify31,32, to more advanced setups capable of independently controlling multiple extruders33. This flexibility makes DIY bioprinters an attractive option for many researchers.

The majority of coaxial bioprinting studies have utilized custom-made bioprinting setups16,17,24,25. Syringe pump extruders feeding the hydrogel to handmade coaxial nozzles are often separately controlled from the XYZ movement of the bioprinter, which may restrict the platform’s performance and customizability. Despite the broad applicability of coaxial bioprinting and the growing availability of DIY bioprinter guides, there is still a lack of comprehensive resources on affordable alternatives to commercial coaxial bioprinters. Even with recent advancements, such as the 3D fabrication of fully customizable coaxial nozzles34, no detailed guide has been published to address this gap.

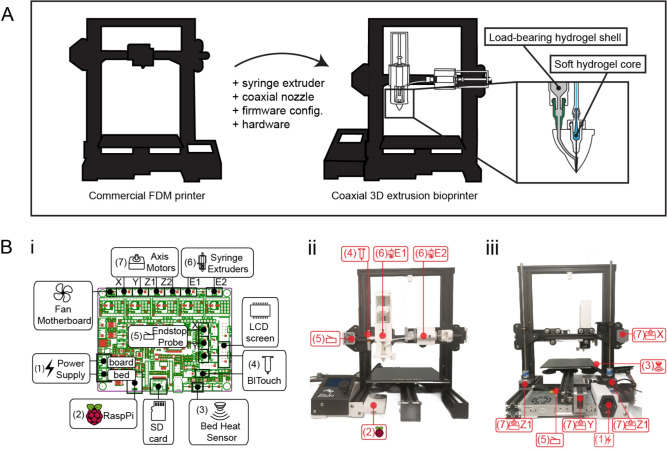

The objective of this study was to present a DIY guide for a cost-effective (< 600€) portable coaxial 3D bioprinter. The printer was created by modifying a commercial desktop printer, and a coaxial nozzle print head was designed and fabricated (Fig. 1, A). The printing performance was evaluated using well-known materials used for tissue engineering applications. Coaxial extruded strands consisted of a soft gelatin-alginate hydrogel core material35 supported by a load-bearing and thermoresponsive methylcellulose (MC)-based hydrogel shell36,37. The impact of nozzle dimensions and in-situ crosslinking of the hydrogel core material on the shape fidelity of 3D printed scaffolds were evaluated. In addition, crosslinking kinetics and rheological properties were analyzed, and a computational simulation of fluid dynamics was performed. To validate the suitability of the modified bioprinter for biological applications, we printed stable scaffold structures with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) encapsulated within a soft hydrogel core containing varying concentrations of alginate.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of 3D extrusion bioprinter and coaxial nozzle assembly. (A) The modification of a commercial fused deposition modeling 3D printer enables coaxial bioprinting of soft cell-laden hydrogels supported by a load-bearing hydrogel shell. (B; i) Pinout diagram of SKR2.0 motherboard. (B; ii) Front view image of modified 3D extrusion bioprinter. (B; iii) Back view image of modified 3D extrusion bioprinter.

Results and discussion

Conversion of desktop 3D printer into a coaxial 3D extrusion bioprinter

Creality Ender 3 Pro, a commercially available 3D printer, was chosen for its affordability, quality build, and strong open-source community support. Its aluminum frame ensures stability and durability, providing enough space to implement the changes necessary to build a coaxial 3D extrusion bioprinter. For its conversion into a coaxial 3D extrusion bioprinter, the hotend extruder was replaced by two extruders suitable for handling hydrogels (Fig. 1, A). The built-in Ender 3 Pro motherboard was changed to the SKR 2.0 Rev B, a 32-bit motherboard capable of directly controlling up to five individual stepper motors (Fig. 1, B; i). Equipped with TMC2209 stepper motor drivers it facilitates precise movement along the X, Y, and Z axes, supporting two extruders. Firmware was configured using open-source Marlin to enable dual extrusion via the SD card and is described in detail in the supplementary material (Tables S1, S2, and S3). Due to the port outlets being on the opposite side compared to the default motherboard, a new case for the SKR2.0 was printed (Fig. 1, B; ii). The power supply was moved to maintain a compact design and accommodate a second Z-axis lead screw. An additional lead screw helped to balance the printer’s gantry movement and ensured precise vertical motion, considering the added weight of two syringe extruders compared to the original hotend extruder system (Fig. 1, B; iii). Additional Birmingham shaft couplers were installed between the Z-axis motor and lead screw to address misalignment and minimize backlash. On average, the printer exhibited a Z-axis accuracy of 9.9725±0.0449mm during upward movement and 9.9725±0.0205mm during downward movement, for a theoretical 10mm displacement. To ensure consistent 3D printing a BLTouch Z-level probe sensor (Antlabs) compatible with the SKR 2.0 motherboard was installed. The sensor allowed precise adjustments to the printer’s Z-axis and automated the bed leveling process to compensate for any bed irregularities and misalignment due to the dual extrusion weight. USB connectivity of the motherboard enabled remote control and monitoring via Raspberry Pi with an open-source OctoPi image preinstalled. A detailed description of the printer modification, including CAD files of all parts, is available in the supplementary materials.

Syringe pump extruder print head fabrication

To facilitate the extrusion of hydrogels, the printer was equipped with stepper motor-driven syringe pump extruders (Fig. 2, A). These extruders, powered by stepper motors directly driving the syringe plunger, offer precise extrusion and retraction of ink. While pneumatic-driven extruders, commonly used in commercial systems, are generally simpler in design with fewer mounting parts, precise control of highly viscous materials can be challenging. In contrast, syringe pump extruders facilitate precise control, allowing for accurate matching of flow rates for both low and highly viscous materials during coaxial extrusion. The 3D printable syringe unit can be assembled with minimal hardware accommodating a 3ml luer-lock syringe (BD Biosciences). Printing of syringe pump extruder parts and assembly with necessary hardware is described in detail in the supplementary material. The syringe pump extruder feeding the viscous shell material was mounted to the back plate in a horizontal position facilitating movement along the X-axis (Fig. 2, A; i, ii). An adaptor piece connected the syringe extruder to the Z-level sensor allowing a quick change of position between calibration and printing. A mount joined by sliding into the extruder assembly aligned the syringe with the coaxial nozzle secured by mounting brackets, maintaining a consistent Z-position without repetitive calibration or Z-offset adjustments when changing syringes. The second syringe extruder designated to extrude low-viscosity bioinks was mounted to the back plate in a horizontal position. An adaptor connected the syringe secured in a mount to a silicone tubing feeding the core material to the coaxial nozzle. Maintaining the syringe in a horizontal position and feeding the material through a narrow tubing via an adapter piece enabled the homogeneous extrusion of low-viscosity bioinks containing cells, overcoming issues of cell sedimentation (Fig. 2, A; iii).

Fig. 2.

Syringe pump extruder assembled with SLA 3D printed coaxial nozzle. (A; i) CAD assembly of primary syringe pump extruder. (A; ii) Assembled syringe pump extruder from 3D printed and hardware parts. (A; iii) Syringe to extruder mount with coaxial nozzle affixed to mounting brackets and tube feeding core material. (A; iv) Coaxial nozzle with blunt-tip needles inserted. (B, i) Tip of the coaxial nozzle with an outer diameter of 640  under magnification. (B; ii) Fluid flow speed profile at coaxial nozzle tip (OD 640

under magnification. (B; ii) Fluid flow speed profile at coaxial nozzle tip (OD 640  ) comparing core-shell extrusion ratios. (B, iii) Tip of the coaxial nozzle with an outer diameter of 840

) comparing core-shell extrusion ratios. (B, iii) Tip of the coaxial nozzle with an outer diameter of 840  under magnification. (B; iv) Fluid flow speed profile at coaxial nozzle tip (OD 840

under magnification. (B; iv) Fluid flow speed profile at coaxial nozzle tip (OD 840  ) comparing core-shell extrusion ratios.

) comparing core-shell extrusion ratios.

Coaxial nozzle fabrication

The configuration of commercially available coaxial 3D bioprinting systems often limits the choice of materials, particularly regarding viscosity. The typical setup involves the lateral feeding of shell material through tubing into a long cylindrical steel nozzle, which can impede the extrusion of highly viscous materials. Additionally, when cells are encapsulated in a low-viscosity core material and loaded into a vertically positioned syringe, there is a risk of sedimentation before extrusion. To address these challenges, a novel coaxial nozzle was designed, and the main body was 3D printed. The design features a wide channel and conical-shaped shell feed, facilitating the extrusion of highly viscous shear-thinning hydrogel materials. Blunt-tip 14-gauge needles were inserted into the nozzle shell inlet to allow syringe attachment via a luer lock connection (Fig. 2, A; iv). Additionally, a 12.7mm long 27-gauge needle was inserted into the nozzle center to dispense low-viscosity hydrogel core material. In this study, we selected two configurations with identical inner needle diameters of 200 but different outer nozzle diameters of 640

but different outer nozzle diameters of 640 and 840

and 840 (Fig. 2, B; i, iii). CFD analysis showed varying flow speed profiles based on the core-shell extrusion ratio for the two chosen nozzle configurations (Fig. 2, B; ii, iv). The wider nozzle configuration increased the relative flow speed between the core and shell, while a smaller outer diameter yielded a more uniform flow profile. However, decreasing the outer nozzle diameter also increased the shear force necessary for extruding the shell material, consequently elevating shear stress values (Fig. S17).

(Fig. 2, B; i, iii). CFD analysis showed varying flow speed profiles based on the core-shell extrusion ratio for the two chosen nozzle configurations (Fig. 2, B; ii, iv). The wider nozzle configuration increased the relative flow speed between the core and shell, while a smaller outer diameter yielded a more uniform flow profile. However, decreasing the outer nozzle diameter also increased the shear force necessary for extruding the shell material, consequently elevating shear stress values (Fig. S17).

Rheological characterization of core and shell hydrogel

Cells embedded in viscoelastic hydrogels have demonstrated faster proliferation, better differentiation, and faster matrix remodeling compared to purely elastic alternatives38–40. This work explored the potential of core-shell bioprinting to fabricate 3D structures by encapsulating cells in a soft gelatin-alginate hydrogel core. These bioinks are not printable by conventional 3D extrusion bioprinting. A thermoresponsive MC-based hydrogel shell provides mechanical stability and may induce in-situ crosslinking when in contact with core (Fig. 3, A). We employed two types of shell hydrogels to evaluate the effect of in-situ crosslinking on printing performance. A non-crosslinking inducing hydrogel was formulated by blending MC in a sodium chloride, and sucrose-containing solution. A crosslinking-inducing hydrogel was formulated by additionally supplementing calcium chloride to the hydrogel blend, however, reducing sodium chloride content proportionally. Rheological results indicated that the two shell formulations regardless of ion type supplemented, displayed similar storage and loss moduli and gelation points (Fig. 3, B; i). Both hydrogel blends exhibit a tan( ) in a range beneficial for 3D printing structures with good shape fidelity and undergo gelation in a cell culture environment at 37 °C (Fig. 3, B, ii)37. In comparison, the mechanical properties of gelatin-alginate core hydrogel formulation were significantly lower than shell hydrogel formulations, and viscosity was further reduced after sterilization by autoclavation (Fig. S18). However, crosslinking kinetics were not affected by sterilization, and gelatin-alginate hydrogels reached mechanical characteristics similar to those of the non-treated condition (Fig. 3, C; i). We further evaluated how Na+ and Ca2+ compete in ionotropic gelation of guluronic acid blocks within the alginate polymer. It was evident that the presence of NaCl in the shell material reduced crosslinking of core hydrogel by CaCl2 (Fig. 3, C; ii).

) in a range beneficial for 3D printing structures with good shape fidelity and undergo gelation in a cell culture environment at 37 °C (Fig. 3, B, ii)37. In comparison, the mechanical properties of gelatin-alginate core hydrogel formulation were significantly lower than shell hydrogel formulations, and viscosity was further reduced after sterilization by autoclavation (Fig. S18). However, crosslinking kinetics were not affected by sterilization, and gelatin-alginate hydrogels reached mechanical characteristics similar to those of the non-treated condition (Fig. 3, C; i). We further evaluated how Na+ and Ca2+ compete in ionotropic gelation of guluronic acid blocks within the alginate polymer. It was evident that the presence of NaCl in the shell material reduced crosslinking of core hydrogel by CaCl2 (Fig. 3, C; ii).

Fig. 3.

Rheological characterization of core and shell hydrogel formulation. (A) The schematic illustrates a coaxial extruded strand with Ca2+ ions eluting from the thermoresponsive MC-shell to form ionic bonds with alginate chains in the hydrogel core. (B; i) Strain sweep results depict the influence of different salt formulations on the rheological properties of MC-based hydrogel shells. The formulations contained 7% MC, with (Ca2+) containing 650 mM NaCl, 100 mM CaCl2, and 10% sucrose, and (control) containing 750 mM NaCl and 10% sucrose. (B; ii) Comparison of gelation points between shell hydrogel formulations. (C; i) Crosslinking kinetics of the alginate-gelatin core hydrogel formulation upon exposure to 100 mM CaCl2 solution, both before and after autoclavation. In comparison, the autoclaved core formulation was exposed to a solution containing 650 mM NaCl, and 100mM CaCl2 (autoclaved + NaCl). (C; ii) Storage modulus of alginate-hydrogel core after crosslinking for 10 min. Statistical significant differences were marked with **p < 0.01.

Coaxial 3D Printing

During coaxial nozzle extrusion, the viscous hydrogel shell contains the soft core material to form stable filaments. Increasing the core extrusion may reduce the capacity of the shell hydrogel to stabilize extruded filaments, eventually causing spillage of the soft hydrogel core. In-situ crosslinking by Ca2+ ions eluting from hydrogel shell may stabilize core fiber to prevent the rupture of extruded filaments and the collapse of printed structures. Likewise, the nozzle dimension, which determines the fluid flow speed at the nozzle tip, influences the stability of extruded filaments. To understand the relationship between nozzle dimensions, core-shell ratio, and in-situ crosslinking, the perimeter of a cubical structure was printed and height was compared among conditions. The printed structures exhibited similar heights when exclusively printing shell hydrogel material, irrespective of the ion type (Fig. 4, A). However, scaffold structures progressively collapsed relative to the percentage of gelatin-alginate core extrusion without Ca2+ ions eluting from the shell hydrogel and stabilizing the soft core hydrogel. When the fraction of extruded gelatin-alginate hydrogel exceeded 40%, the hydrogel shell could no longer contain the core hydrogel, leading to the rupture of extruded strands and spillage of the soft hydrogel core. In contrast, the CaCl2-doped hydrogel shell material facilitated in-situ crosslinking of the hydrogel core. Consequently, scaffolds of at least 6 layers could be successfully printed without observing a decrease in relative height, regardless of core extrusion rate or nozzle dimensions (Fig. 4, A; i, ii).

Fig. 4.

Coaxial 3D printing of hydrogel scaffolds. (A; i, ii) Images as a function of nozzle dimensions and core extrusion of 3D printed square structures to assess the impact Ca2+-induced in-situ crosslinking on the structural integrity. Scale bar = 5 mm. (A; iii, iv) Quantitative evaluation of relative height of 3D printed structures. (B, i) Woodpile structure of 20 layers printed with a core-shell ratio of 30 to 70. (B, ii) Top view of the 3D printed woodpile structure. (B, iii) Stereomicroscopic image of 3D printed woodpile structure. (B, iv) 3D printed vase model with the core-shell extrusion ratio gradually changing from 0–100 to 35–65%.

Quantitative evaluation of image data revealed a trend towards an increase in relative height with an increase in the percentage of core extrusion (Fig. 4, A; iii, iv). However, for the coaxial nozzle with a wider outer diameter of 840 , relative height decreased again at core extrusion rates exceeding 40%. We observed that increasing the percentage of core extrusion and the outer diameter of core-shell nozzles led to impaired first-layer attachment to the polyetherimide build plate. Printing a skirt structure to establish smooth hydrogel flow did not prevent adhesion issues. Extruded filaments could not properly attach to the build plate and the bond between extruded layers decreased, resulting in reduced diameter and inward warping of printed structures. Nevertheless, rapid crosslinking of gelatin-alginate in extruded hydrogel strands displayed weight-bearing characteristics, preventing scaffold collapse in the Z-direction. We attribute the differences observed between the two nozzle configurations to variations in flow rate profiles. A more homogeneous speed distribution of core-shell extrusion improved in-situ crosslinking and prevented spillage of the soft hydrogel core. Furthermore, we demonstrated the capabilities of the coaxial extrusion bioprinter to print larger woodpile structures comprising up to 20 layers, with a core-shell ratio set to 70-30 (Fig. 4, B; i, ii, iii). Incorporating a blue color dye into the alginate-gelatin core hydrogel displayed an even core material distribution throughout the scaffold structure. The printed structure displayed excellent shape fidelity and the presence of open pores. Additionally, we successfully printed a vase model utilizing a gradient mix function, which automatically updated as the Z-position changed during the print (Fig. 4, B; iv). The printed vase model showcased a noticeable color gradient shifting from a transparent (shell material only) hue to a deep blue (as the fraction of core material increased). Hence, the mix gradient function enables precise spatial control over the core-shell ratio in different regions of the 3D printed model. This functionality is particularly beneficial for segments serving varied roles within the structure. For areas requiring enhanced load-bearing capabilities, a higher proportion of viscous hydrogel shell can be selected. Conversely, for sections intended for biological functions, such as those where cells are encapsulated within the core hydrogel, a different core-shell ratio can be selected. This flexibility ensures that each part of the printed model fulfills its designated function optimally.

, relative height decreased again at core extrusion rates exceeding 40%. We observed that increasing the percentage of core extrusion and the outer diameter of core-shell nozzles led to impaired first-layer attachment to the polyetherimide build plate. Printing a skirt structure to establish smooth hydrogel flow did not prevent adhesion issues. Extruded filaments could not properly attach to the build plate and the bond between extruded layers decreased, resulting in reduced diameter and inward warping of printed structures. Nevertheless, rapid crosslinking of gelatin-alginate in extruded hydrogel strands displayed weight-bearing characteristics, preventing scaffold collapse in the Z-direction. We attribute the differences observed between the two nozzle configurations to variations in flow rate profiles. A more homogeneous speed distribution of core-shell extrusion improved in-situ crosslinking and prevented spillage of the soft hydrogel core. Furthermore, we demonstrated the capabilities of the coaxial extrusion bioprinter to print larger woodpile structures comprising up to 20 layers, with a core-shell ratio set to 70-30 (Fig. 4, B; i, ii, iii). Incorporating a blue color dye into the alginate-gelatin core hydrogel displayed an even core material distribution throughout the scaffold structure. The printed structure displayed excellent shape fidelity and the presence of open pores. Additionally, we successfully printed a vase model utilizing a gradient mix function, which automatically updated as the Z-position changed during the print (Fig. 4, B; iv). The printed vase model showcased a noticeable color gradient shifting from a transparent (shell material only) hue to a deep blue (as the fraction of core material increased). Hence, the mix gradient function enables precise spatial control over the core-shell ratio in different regions of the 3D printed model. This functionality is particularly beneficial for segments serving varied roles within the structure. For areas requiring enhanced load-bearing capabilities, a higher proportion of viscous hydrogel shell can be selected. Conversely, for sections intended for biological functions, such as those where cells are encapsulated within the core hydrogel, a different core-shell ratio can be selected. This flexibility ensures that each part of the printed model fulfills its designated function optimally.

Coaxial bioprinting of soft alginate-gelatin cell-laden hydrogel

The stiffness and viscoelastic properties of alginate hydrogels impact the spreading, proliferation, and lineage commitment of cells39–41. By fine-tuning different properties, such as the molecular weight, backbone block composition and distribution, polymer concentration, and type/amount of crosslinkers it is possible to modulate the viscoelastic properties of alginate solutions and their hydrogels. To demonstrate the ability to alter the mechanical properties of cell-encapsulating alginate-gelatin core hydrogels while maintaining the fabrication of stable scaffolds, two different alginate core concentrations were compared for printability and rheological properties (Fig. 5). Rheological results showed that the elastic modulus after ionic crosslinking was halved when reducing the alginate concentration from 1.5% to 0.5% (Fig. 5, A). Interestingly, the shape fidelity of printed scaffolds remained unchanged after lowering the alginate percentage in the core bioink (Fig. 5, B). The relative height of 3D-printed cubical structures showed no difference between the two tested core bioink formulations. Therefore, in-situ crosslinking of the alginate core by Ca2+ ions eluting from the shell material enabled the fabrication of stable cubical structures regardless of alginate concentration42. When ionically crosslinked, viscoelastic alginate hydrogels form under mild and biocompatible conditions39,43. However, ion type, concentration, crosslinking duration, and buffer pH influence the viability of encapsulated cells. The high NaCl and CaCl2 concentration in the shell material may impose a risk of osmotic stress to cells encapsulated in the alginate-gelatin core bioink after extrusion. To address these concerns, the viability of 3D printed cells was tested for up to 14 days (Fig. 6). Viability staining confirmed a homogenous distribution of viable cells within the core after printing regardless of the alginate concentration used. After one day of incubation, high viability (> 80%) of encapsulated cells was observed in all conditions (data not shown). In comparison to non-printed control hydrogels (crosslinked for 5 minutes in CaCl2-buffer), cell viability in printed conditions was initially lower. However, cell viability in printed conditions recovered to over 90% after 7 days. High cell viability was maintained for up to 14 days of incubation, indicating that the MC-based hydrogel shell allowed sufficient nutrient diffusion.

Fig. 5.

Comparing the effect of percentage of alginate in the core hydrogel on rheological properties and printability. (A; i) Crosslinking of the alginate core upon exposure to a solution containing 650 mM NaCl, and 100 mM CaCl2. (A; ii) Storage modulus of alginate-hydrogel core after crosslinking for 10 min. i) Images of 3D printed square structures. Scale bar = 5 mm. (B; ii) Quantitative evaluation of relative height of 3D printed structures.

Fig. 6.

Viability of cells in bioprinted scaffolds. Fluorescence images of live/dead stained MSCs in printed filaments for different alginate concentrations at day 1, 7, and 14. Scale bar = 500  .

.

In summary, while the presented DIY coaxial extrusion bioprinting system offers a versatile and cost-effective platform for the fabrication of soft, cell-laden constructs, several general considerations should be acknowledged. In 3D extrusion bioprinting, resolution is primarily determined by the diameter of the nozzle. Coaxial nozzles, by design, require two concentric channels, which inherently increases the outer diameter compared to single-orifice nozzles, thus reducing overall resolution. However, this trade-off is often acceptable given the added capability to spatially compartmentalize different materials or cell types within a single printed structure. Importantly, besides its low cost, the presented coaxial nozzle supports the extrusion of highly viscous hydrogels through the shaft, a feature that distinguishes it from many commercially available coaxial nozzles, which typically rely on long concentric designs that restrict the use of such materials. Additionally, the openly available design presented here provides a foundation for further modifications, such as the development of multiaxial or microfluidic printheads. Notably, nozzle clogging is a known challenge across extrusion-based systems, particularly when working with highly viscous bioinks, materials with rapid gelation, or those containing cell aggregates or microparticles. In our experience, the coaxial configuration does not inherently increase the risk of clogging, provided that bioink formulations are selected and optimized for the specific nozzle geometry. Hence, nozzle geometry and bioink formulation are tightly interconnected, requiring careful co-optimization rather than a one-directional fit. Finally, the shell layer can act as a protective barrier around the core, reducing evaporation and maintaining a hydrated microenvironment during prolonged printing sessions. This feature becomes increasingly valuable when larger and more complex constructs are manufactured, allowing independent control of mechanical stability and biological functionality across different scaffold regions. Together, these aspects highlight the potential of coaxial bioprinting to advance the fabrication of functional tissue constructs and broaden the range of printable bioinks.

Methods

Materials

MC (4000 cP), calcium chloride (CaCl2), sodium chloride (NaCl), sucrose, Minimum Essential Medium Eagle ( MEM), research-grade fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin cocktail (P/S), trypsin-EDTA, paraformaldehyde (PFA), Parafilm M and triton X-100, were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). DPBS solution, Propidium Iodide, calcein AM, GlutaMAXTM, sterile syringe filters (polyethersulfone, 0.2

MEM), research-grade fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin cocktail (P/S), trypsin-EDTA, paraformaldehyde (PFA), Parafilm M and triton X-100, were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). DPBS solution, Propidium Iodide, calcein AM, GlutaMAXTM, sterile syringe filters (polyethersulfone, 0.2  m, 25 mm), and MasterflexTM silicone tubing (inner diameter of 0.6mm) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Tissue culture inserts for 24-well plates, pore size 8

m, 25 mm), and MasterflexTM silicone tubing (inner diameter of 0.6mm) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Tissue culture inserts for 24-well plates, pore size 8  were purchased from Sarstedt (Nümbrecht, Germany). Ethanol absolute pure for molecular biology and sodium alginate were purchased from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany). Liqcreate Clear Impact transparent resin was purchased from 3DJake (Paldau, Styria, Austria). Isopropyl alcohol 99.9% was purchased from 3D-basics (Vienna, Austria). General Purpose Stainless Steel Tips (27G, 12.7 mm) were purchased from Nordson (Westlake, Ohio, USA). The desktop 3D printer and parts purchased for modification are listed in Tables S5 and S7.

were purchased from Sarstedt (Nümbrecht, Germany). Ethanol absolute pure for molecular biology and sodium alginate were purchased from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany). Liqcreate Clear Impact transparent resin was purchased from 3DJake (Paldau, Styria, Austria). Isopropyl alcohol 99.9% was purchased from 3D-basics (Vienna, Austria). General Purpose Stainless Steel Tips (27G, 12.7 mm) were purchased from Nordson (Westlake, Ohio, USA). The desktop 3D printer and parts purchased for modification are listed in Tables S5 and S7.

Coaxial 3D bioprinter configuration

Computer-assisted design (CAD) models for modifying an Ender 3 printer (Creality) and fabricating syringe pump extruders were generated using Solid Works 2022® (Dassault Systems). The designed components were sliced into printable layers using Ultimaker Cura software and 3D printed using polylactic acid (PLA) filament on an Ultimaker 2+ Connect 3D printer. A complete list of computer-aided design (CAD) files, hardware parts, and firmware changes is provided in the supplementary materials.

Coaxial nozzle design and fabrication

The main body of the nozzle was printed using a Phrozen Sonic Mighty 8K with Liqcreate Clear Impact photopolymer resin. Layer height was set to 25  . Superior surfaces of the nozzles made contact with the build surface to avoid support structures. After printing, nozzles were rinsed in isopropanol, followed by drying with pressurized air. The 27 gauge, 12.7 mm long blunt tip was inserted manually and fixed by applying photopolymer resin between the needle hub and nozzle body. Nozzles were post-cured by UV light for 1 h in the Elegoo Mercury Plus UV chamber and left at 60

. Superior surfaces of the nozzles made contact with the build surface to avoid support structures. After printing, nozzles were rinsed in isopropanol, followed by drying with pressurized air. The 27 gauge, 12.7 mm long blunt tip was inserted manually and fixed by applying photopolymer resin between the needle hub and nozzle body. Nozzles were post-cured by UV light for 1 h in the Elegoo Mercury Plus UV chamber and left at 60  C overnight. Dimensions of the two fabricated nozzle configurations are given in Table 1.

C overnight. Dimensions of the two fabricated nozzle configurations are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Coaxial nozzle dimensions including inner diameter (ID), outer diameter (OD), and cross-sectional area ratio.

| Prefix | Nozzle ID ( ) ) |

Nozzle OD ( ) ) |

Cross-sectional area ratio (ID:OD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wide nozzle | 200 | 840 | 8.36 : 91.64 |

| Narrow nozzle | 200 | 640 | 17.9 : 82.1 |

Preparation of shell and core hydrogel

The shell bioinks were prepared by dissolving MC in a solution containing different concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl), sucrose, and calcium chloride (CaCl2) (Table 2). Briefly, MC was dissolved and blended in pre-heated (70  C) salt-sucrose containing solution using the SpeedMixer Dax 150.1 FVZ (FlackTek, Inc.) at 700 rpm for 5 min. For cell culture, salt-sucrose solutions were filter sterilized and MC was steam sterilized by autoclaving at 121

C) salt-sucrose containing solution using the SpeedMixer Dax 150.1 FVZ (FlackTek, Inc.) at 700 rpm for 5 min. For cell culture, salt-sucrose solutions were filter sterilized and MC was steam sterilized by autoclaving at 121  C for 15 min before mixing under aseptic conditions. Bioink formulations were stored at 4

C for 15 min before mixing under aseptic conditions. Bioink formulations were stored at 4  C overnight to allow complete hydration.

C overnight to allow complete hydration.

Table 2.

Shell bioink formulations.

| Prefix | MC (% w/v) | NaCl (mM) | Sucrose (% w/v) | CaCl2 (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 7 | 750 | 10 | 0 |

| Ca2+ | 7 | 650 | 10 | 100 |

The core bioink was prepared by dissolving sodium alginate and gelatin in a NaCl-containing solution (Table 3). For cell culture, alginate-gelatin solutions were steam sterilized by autoclaving at 121  C for 15 min.

C for 15 min.

Table 3.

Core bioink formulations

| Prefix | Alginate (% w/v) | Gelatin (% w/v) | NaCl (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High alginate | 1.5 | 3 | 150 |

| Llow alginate | 0.5 | 3 | 150 |

Rheological tests

Rheometric experiments were performed using a TA Instruments Discovery Hybrid Rheometer-2. All rheometric experiments were performed using a 20 mm stainless steel upper plate at 25  C. For rheological measurements of bioink formulations, the measuring gap was set to 500

C. For rheological measurements of bioink formulations, the measuring gap was set to 500  with a trim gap offset of 50

with a trim gap offset of 50  . Following a rest interval of 2 min, storage modulus (G

. Following a rest interval of 2 min, storage modulus (G ), loss modulus (G

), loss modulus (G ), and loss tangent (tan (

), and loss tangent (tan ( )) were measured using a shear strain sweep test ranging from 0.01 % to 500 % at an angular frequency of 10 rad/s. Temperature ramp tests were performed at a linear heating rate from 25–50

)) were measured using a shear strain sweep test ranging from 0.01 % to 500 % at an angular frequency of 10 rad/s. Temperature ramp tests were performed at a linear heating rate from 25–50  C of 2

C of 2  C/min, 1 % strain, at an alternating angular frequency of 1, 3, and 7 Hz. The gelation temperature was observed at the intersection between the tan (

C/min, 1 % strain, at an alternating angular frequency of 1, 3, and 7 Hz. The gelation temperature was observed at the intersection between the tan ( ) curves measured for the three angular frequencies. To evaluate the crosslinking kinetics of alginate core bioinks, oscillatory measurements were performed at a constant angular frequency of 10 rad/s and 1% strain. Samples were equilibrated for 60 s before adding 100 mM CaCl2, with the option of supplementation with 650 mM NaCl. The crosslinking process was monitored for 10 min. Rotational tests were performed to assess the flow behavior of core and shell bioink formulations, increasing the shear rate from 0.01 to 100 s−1.

) curves measured for the three angular frequencies. To evaluate the crosslinking kinetics of alginate core bioinks, oscillatory measurements were performed at a constant angular frequency of 10 rad/s and 1% strain. Samples were equilibrated for 60 s before adding 100 mM CaCl2, with the option of supplementation with 650 mM NaCl. The crosslinking process was monitored for 10 min. Rotational tests were performed to assess the flow behavior of core and shell bioink formulations, increasing the shear rate from 0.01 to 100 s−1.

Finite element analysis of shear stress

Finite element fluid flow simulations were performed in COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 software (COMSOL AB) and 3D models were imported using LiveLinkTM for Solid Works® add-on. A stationary simple laminar flow study was performed using a physics-controlled mesh set to normal size. The mass flow rates chosen for the CFD simulation were based on empirical findings obtained during printing at a speed of 3 mm/s. In the wider nozzle configuration, the total inlet mass flow rate was set to 1.529 (mg/s), while for the narrow nozzle configuration, it was set to 0.917 (mg/s). A parametric sweep explored different ratios of inlet mass flow rates between the core and shell, ranging from pure shell (0–100) to equal parts of core and shell (50–50). Bioink properties were modeled as an inelastic, non-Newtonian fluid where the dynamic viscosity follows

|

1 |

with  being the dynamic viscosity,

being the dynamic viscosity,  the shear rate, n the flow behavior index, and K the consistency coefficient. The flow behavior index and consistency coefficient were empirically obtained by fitting the recorded flow curves. The values found were n = 0.57, K = 0.211 for the high alginate core solution, and n = 0.382, and K = 875.2 for the Ca2+ shell hydrogel. The boundary conditions were atmospheric pressure at the outlet and no slip at the walls.

the shear rate, n the flow behavior index, and K the consistency coefficient. The flow behavior index and consistency coefficient were empirically obtained by fitting the recorded flow curves. The values found were n = 0.57, K = 0.211 for the high alginate core solution, and n = 0.382, and K = 875.2 for the Ca2+ shell hydrogel. The boundary conditions were atmospheric pressure at the outlet and no slip at the walls.

Core-shell 3D Printing

A 3D printer (Ender 3, Creality) was equipped with two syringe extruders for extruding two bioinks simultaneously. The coaxial nozzle was mounted to the primary syringe extruder which directly fed the shell bioink. The second syringe extruder fed the core bioink connected to the coaxial nozzle by a flexible silicone tube. G-code files of printing scaffold structures were generated using a custom Python script. Printing speed was set to 3 mm/s and extrusion rate to 1.529  for the wide nozzle and 0.917

for the wide nozzle and 0.917  for the narrow nozzle. The print bed temperature was set to 37

for the narrow nozzle. The print bed temperature was set to 37  C for all experiments.

C for all experiments.

Screening effect of core-shell extrusion ratio

Screening experiments were conducted using the 1.5% alginate core formulation, comparing Ca2+ to control shell formulation at varying core-shell ratios, ranging from pure shell (100–0) to equal parts core and shell (50–50). These experiments involved printing 6-layered cubical structures with a diameter of 13 mm. To capture the printed structures immediately after extrusion, G-code was customized to enable image acquisition using an endoscope camera (1080p) equipped with a 5x magnifying lens (Smart Micro Optics). The camera was attached to the extruder print head carrying the coaxial nozzle. Utilizing the Octolapse plug-in, G-code commands were integrated to capture images at predefined positions during the printing process automatically. The structural integrity of the printed hydrogel formulations was quantified by comparing the relative height between the bioink formulations using ImageJ software44.

Printing larger models

Larger and more intricate structures were fabricated using a 1.5% alginate core formulation supplemented with blue food color dye. The Ca2+ bioink formulation was selected as shell material. A woodpile structure comprising 20 layers with a diameter of 17 mm was printed, maintaining a fixed core-shell ratio of 30 to 70. A vase model was also printed using the Marlin firmware gradient mix tool. M166 G-code command enabled the fabrication of structures with a smooth transition between two syringe extruders over a given starting and ending Z-height. In the printed vase model, the gradient of core-shell extrusion began with a fraction of 0–100 at the starting Z-height and gradually transitioned to 35–65 when approaching the ending Z-height of the printed structure.

Biological testing

Mesenchymal stem cell isolation and culture

MSCs were isolated from bone marrow flushed from the femurs and tibias of five week old male Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously45. In short, rats were euthanized by CO2 inhalation for the collection of tibias and femoral bones from the hind legs, cells were harvested, passed through a 40  cell strainer, and centrifuged for 3 min at 200 rcf. Cells were cultured at 37

cell strainer, and centrifuged for 3 min at 200 rcf. Cells were cultured at 37  C and 5% CO2 in culture medium consisting of DMEM alpha modification, 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX, and 1% (v/v) P/S (10000

C and 5% CO2 in culture medium consisting of DMEM alpha modification, 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX, and 1% (v/v) P/S (10000  and 10

and 10  , respectively). The medium was changed every 2–3 days and subconfluent cells were detached from the culture flask by adding trypsin-EDTA solution. Only cells from passages 2 to 5 were used for experiments. All animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of the EU Directive 2010/63/EU, the Spanish Royal and Catalan Decrees 1201/05 and 214/97, respectively, and the Catalan Law 5/95. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), which provided the euthanized rats for our research (procedure ref. 10906 from the Generalitat de Catalunya).

, respectively). The medium was changed every 2–3 days and subconfluent cells were detached from the culture flask by adding trypsin-EDTA solution. Only cells from passages 2 to 5 were used for experiments. All animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of the EU Directive 2010/63/EU, the Spanish Royal and Catalan Decrees 1201/05 and 214/97, respectively, and the Catalan Law 5/95. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), which provided the euthanized rats for our research (procedure ref. 10906 from the Generalitat de Catalunya).

Coaxial 3D bioprinting

For cell encapsulation, rMSCs were detached using trypsin-EDTA solution and resuspended at a concentration of 3x106 cells per ml of alginate core solution. Square scaffolds consisting of 4 layers, each with 7 lines and a layer height of 420  , were 3D printed onto a glass petri dish. The narrow nozzle configuration was utilized, maintaining a core-shell ratio of 30–70. Following printing, the glass petri dish was sealed with parafilm and incubated at 37

, were 3D printed onto a glass petri dish. The narrow nozzle configuration was utilized, maintaining a core-shell ratio of 30–70. Following printing, the glass petri dish was sealed with parafilm and incubated at 37  C for 1 hour to facilitate gelation of the MC-based hydrogel shell. Hydrogel scaffolds were then transferred to a 12-well plate, with each well containing 1.5 ml of prewarmed cell culture medium. Serving as a control the cell-laden core material was crosslinked in 100 mM CaCl2-buffer for 5 min (40

C for 1 hour to facilitate gelation of the MC-based hydrogel shell. Hydrogel scaffolds were then transferred to a 12-well plate, with each well containing 1.5 ml of prewarmed cell culture medium. Serving as a control the cell-laden core material was crosslinked in 100 mM CaCl2-buffer for 5 min (40  per TC insert for 24-well plates). Samples were maintained at 37

per TC insert for 24-well plates). Samples were maintained at 37  C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and every other day 500

C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and every other day 500  of medium was replenished with fresh medium.

of medium was replenished with fresh medium.

Cell viability

After 1, 7, and 14 days live cells were stained using calcein AM cell permanent dye, and dead cells were counterstained using propidium iodide membrane impermeant dye. Hydrogel samples were incubated in a solution containing 2  M calcein AM, 750 nM propidium iodide (PI), 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2. Then samples were washed twice in DPBS and imaged with a Leica TCS SP8 CLSM using excitation/emission wavelengths of 494/510-540 and 535/600-640 nm, respectively. Quantification of live-cell-ration was performed via Finding Maxima function using ImageJ software. Living and dead cells, respectively, were divided by the total number of cells and multiplied by 100.

M calcein AM, 750 nM propidium iodide (PI), 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2. Then samples were washed twice in DPBS and imaged with a Leica TCS SP8 CLSM using excitation/emission wavelengths of 494/510-540 and 535/600-640 nm, respectively. Quantification of live-cell-ration was performed via Finding Maxima function using ImageJ software. Living and dead cells, respectively, were divided by the total number of cells and multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in at least three replicates (n = 3). The distribution of values was considered normal for evaluating statistical differences among all experiments performed. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of the replicates. A one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey HSD posthoc analysis to compare all means using Origin 2022 (OriginLab).

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully customized a commercial FDM printer to enable coaxial 3D bioprinting. Coaxial bioprinting enhanced the fabrication of intricate structures and allowed for the tuning of mechanical characteristics. By providing CAD files and a detailed description of the printer assembly, we ensured reproducibility and encouraged further modifications by other researchers. This guide to assembling a cost-efficient coaxial bioprinter broadens access to this technology, allowing a wider audience to explore its capabilities. We synchronized the XYZ movement with the extrusion process to improve precision. The easy-to-modify design of the 3D-printed coaxial nozzle allows users to tailor it to match the mechanical properties of various bioink systems and specific applications. We demonstrated the potential of using a viscous hydrogel shell to fabricate cell-laden hydrogel scaffolds of clinically relevant sizes with varying mechanical properties. This approach shifts the focus from meeting bioprinting requirements to tailoring the bioink’s mechanical properties to match the characteristics of native tissue. Further development of this technique can lead to the design and fabrication of tissue scaffolds with greater complexity in both physical and chemical characteristics. By co-extruding combinations of materials, it is possible to enable in-situ crosslinking and create stimuli-responsive dynamic systems. This advancement holds promise for the development of functional tissue constructs that closely mimic the native biological environment, paving the way for significant progress in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank MICIU/AEI 10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER, UE for funding project PID2022-137962OB-I00, MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and Unión Europea NextGenerationEU/PRTR for funding project PLEC2022-009279, and Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya (2021 SGR 00565).

Author contributions

M.J. and M.A.M.-T. conceived the experiment(s), M.J., R.S., F.S. and M.F. conducted the experiment(s), M.J. and S.P.-A. analysed the results. R.A.P. and M.A.M.-T. secured funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the github repository, Coaxial 3D Bioprinter (https://github.com/MaxJer/DIY-coaxial-3D-bioprinter), or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-06478-9.

References

- 1.Murphy, S. V. & Atala, A. 3d bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol.32, 773–785 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mota, C., Camarero-Espinosa, S., Baker, M. B., Wieringa, P. & Moroni, L. Bioprinting: From tissue and organ development to in vitro models. Chem. Rev.120, 10547–10607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng, W. L. & Shkolnikov, V. Jetting-based bioprinting: Process, dispense physics, and applications. Bio-Design and Manufac.7, 771–799 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y. & Hou, D. Recent progress of the vat photopolymerization technique in tissue engineering: A brief review of mechanisms, methods, materials, and applications. Polymers15, 3940 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang, Y. S. et al. 3d extrusion bioprinting. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers1, 1–20 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui, X. et al. Advances in extrusion 3d bioprinting: A focus on multicomponent hydrogel-based bioinks. Adv. Healthcare Mater.9, 1901648 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groll, J. et al. A definition of bioinks and their distinction from biomaterial inks. Biofabrication11, 013001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malda, J. et al. 25th anniversary article: Engineering hydrogels for biofabrication. Adv. Materi.25, 5011–5028 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancha Sánchez, E. et al. Hydrogels for bioprinting: A systematic review of hydrogels synthesis, bioprinting parameters, and bioprinted structures behavior. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.8, 776 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinton, T. J. et al. Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels. Sci. Adv.1, e1500758 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Highley, C. B., Song, K. H., Daly, A. C. & Burdick, J. A. Jammed microgel inks for 3d printing applications. Adv. Sci.6, 1801076 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjar, A., McFarland, B., Mecham, K., Harward, N. & Huang, Y. Engineering of tissue constructs using coaxial bioprinting. Bioact. Mater.6, 460–471 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouyang, L. Pushing the rheological and mechanical boundaries of extrusion-based 3d bioprinting. Trends in Biotechnol.40, 891–902 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohan, T. S., Datta, P., Nesaei, S., Ozbolat, V. & Ozbolat, I. T. 3d coaxial bioprinting: Process mechanisms, bioinks and applications. Progress in Biomed. Eng.4, 022003 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, J., Shao, J., Li, X., Huang, Q. & Xu, T. Bioprinting of coaxial multicellular structures for a 3d co-culture model. Bioprinting11, e00036 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colosi, C. et al. Microfluidic bioprinting of heterogeneous 3d tissue constructs using low-viscosity bioink. Adv. Mater.28, 677–684 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouyang, L., Highley, C. B., Sun, W. & Burdick, J. A. A generalizable strategy for the 3d bioprinting of hydrogels from nonviscous photo-crosslinkable inks. Adv. Mater.29, 1604983 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onoe, H. et al. Metre-long cell-laden microfibres exhibit tissue morphologies and functions. Nat. Mater.12, 584–590 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podstawczyk, D. et al. Coaxial 4d printing of vein-inspired thermoresponsive channel hydrogel actuators. Adv. Funct. Mater.34, 2310514 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilian, D. et al. Core-shell bioprinting as a strategy to apply differentiation factors in a spatially defined manner inside osteochondral tissue substitutes. Biofabrication14, 014108 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, L., Li, X., Zhang, X. & Xu, T. Biomanufacturing of a novel in vitro biomimetic blood-brain barrier model. Biofabrication12, 035008 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, G. et al. Tissue engineered bio-blood-vessels constructed using a tissue-specific bioink and 3d coaxial cell printing technique: A novel therapy for ischemic disease. Adv. Funct. Mater.27, 1700798 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao, G., Park, J. Y., Kim, B. S., Jang, J. & Cho, D.-W. Coaxial cell printing of freestanding, perfusable, and functional in vitro vascular models for recapitulation of native vascular endothelium pathophysiology. Adv. Healthcare Mater.7, 1801102 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, W. et al. Coaxial extrusion bioprinting of 3d microfibrous constructs with cell-favorable gelatin methacryloyl microenvironments. Biofabrication10, 024102 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai, X. et al. Coaxial 3d bioprinting of self-assembled multicellular heterogeneous tumor fibers. Scientific reports7, 1457 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akkineni, A. R., Ahlfeld, T., Lode, A. & Gelinsky, M. A versatile method for combining different biopolymers in a core/shell fashion by 3d plotting to achieve mechanically robust constructs. Biofabrication8, 045001 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walladbegi, J. et al. Three-dimensional bioprinting using a coaxial needle with viscous inks in bone tissue engineering-an in vitro study. Ann Maxillofac. Surg10, 370–376 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reina-Romo, E. et al. Towards the experimentally-informed in silico nozzle design optimization for extrusion-based bioprinting of shear-thinning hydrogels. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.9, 701778 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emmermacher, J. et al. Engineering considerations on extrusion-based bioprinting: Interactions of material behavior, mechanical forces and cells in the printing needle. Biofabrication12(2), 025022 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garciamendez-Mijares, C. E., Agrawal, P., García Martínez, G., Cervantes Juarez, E. & Zhang, Y. S. State-of-art affordable bioprinters: A guide for the diy community. Appl. Phys. Rev.8, 3 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahl, M., Gertig, M., Hoyer, P., Friedrich, O. & Gilbert, D. F. Ultra-low-cost 3d bioprinting: Modification and application of an off-the-shelf desktop 3d-printer for biofabrication. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.7, 184 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pusch, K., Hinton, T. J. & Feinberg, A. W. Large volume syringe pump extruder for desktop 3d printers. HardwareX3, 49–61 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, J., Kim, K. E., Bang, S., Noh, I. & Lee, C. A desktop multi-material 3d bio-printing system with open-source hardware and software. Int. J. Precision Eng. Manufact.18, 605–612 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millik, S. C. et al. 3d printed coaxial nozzles for the extrusion of hydrogel tubes toward modeling vascular endothelium. Biofabrication11, 045009 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao, T. et al. Optimization of gelatin-alginate composite bioink printability using rheological parameters: A systematic approach. Biofabrication10, 034106 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahlfeld, T. et al. Methylcellulosea versatile printing material that enables biofabrication of tissue equivalents with high shape fidelity. Biomater. Sci.8, 2102–2110 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jergitsch, M., Alluè-Mengual, Z., Perez, R. A. & Mateos-Timoneda, M. A. A systematic approach to improve printability and cell viability of methylcellulose-based bioinks. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.253, 127461 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudhuri, O. et al. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity. Nat. Mater.15, 326–334 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neves, M. I., Moroni, L. & Barrias, C. C. Modulating alginate hydrogels for improved biological performance as cellular 3d microenvironments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.8, 665 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elosegui-Artola, A. et al. Matrix viscoelasticity controls spatiotemporal tissue organization. Nat. Mater.22, 117–127 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhuri, O., Cooper-White, J., Janmey, P. A., Mooney, D. J. & Shenoy, V. B. Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature584, 535–546 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tosoratti, E., Bonato, A., Kessel, B., Weber, P. & Zenobi-Wong, M. Shape-defining alginate shells as semi-permeable culture chambers for soft cell-laden hydrogels. Biofabrication15, 035015 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Souza, A., Parnell, M., Rodriguez, B. J. & Reynaud, E. G. Role of ph and crosslinking ions on cell viability and metabolic activity in alginate-gelatin 3d prints. Gels9, 853 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. Nih image to imagej: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Godoy-Gallardo, M. et al. Advanced binary guanosine and guanosine 5’-monophosphate cell-laden hydrogels for soft tissue reconstruction by 3d bioprinting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces15, 29729–29742 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the github repository, Coaxial 3D Bioprinter (https://github.com/MaxJer/DIY-coaxial-3D-bioprinter), or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.